Validating Self-Produced Sensors: A Size-Exclusion Chromatography Guide for Biopharmaceutical Analysis

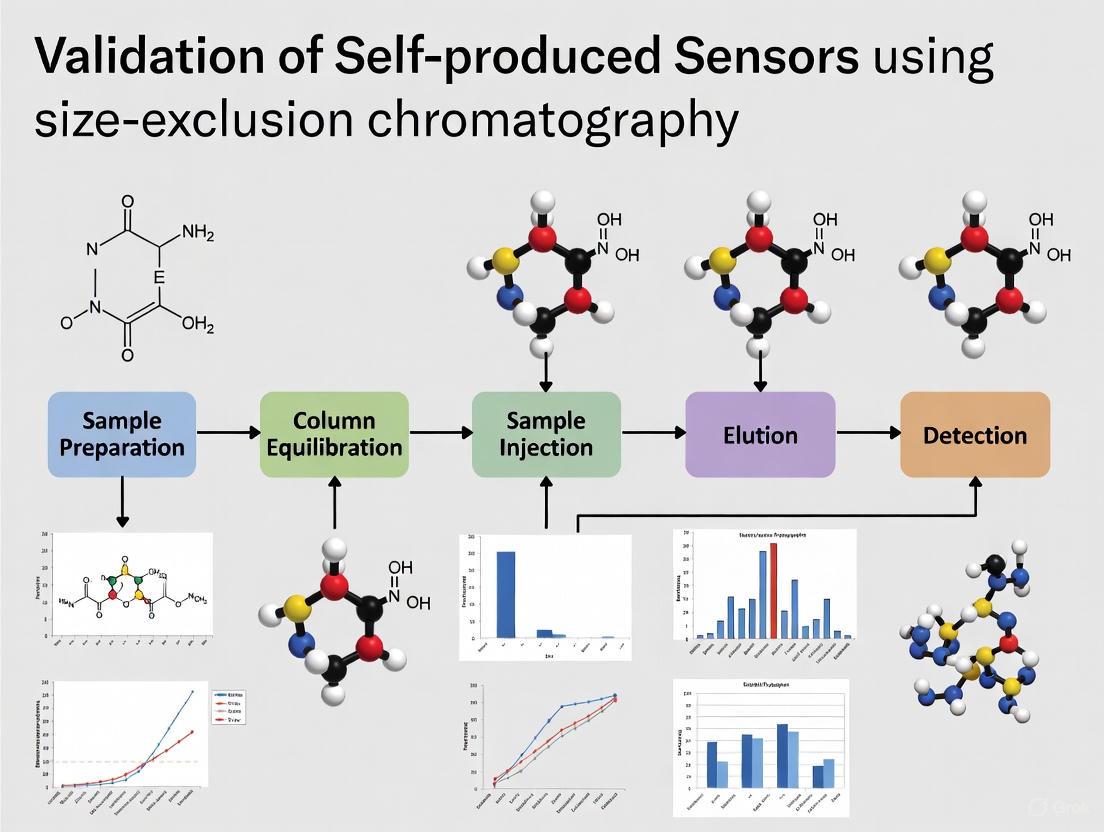

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to validate self-produced sensors using Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC).

Validating Self-Produced Sensors: A Size-Exclusion Chromatography Guide for Biopharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to validate self-produced sensors using Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC). It covers foundational SEC principles for protein analysis and aggregate detection, outlines methodological approaches for integrating novel sensors into SEC workflows, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and establishes rigorous validation protocols against orthogonal methods. By bridging innovative sensor technology with established chromatographic techniques, this guide aims to support the development of reliable, in-house analytical tools for characterizing biopharmaceuticals, from monoclonal antibodies to gene therapy vectors like AAVs, ultimately enhancing process development and quality control.

Core Principles of Size-Exclusion Chromatography in Biomolecular Analysis

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) has established itself as a critical analytical technique for the separation and characterization of macromolecules based on their size in solution. For researchers validating self-produced sensors, understanding the performance characteristics of the SEC stationary phase is fundamental, as it directly impacts the reproducibility, accuracy, and reliability of the separation data. The journey of SEC stationary phases from simple soft gels to advanced hybrid particles represents a continuous pursuit of improved efficiency, stability, and minimal analyte interaction. This evolution has been particularly crucial in the biopharmaceutical industry, where the quantitative assessment of protein aggregates is essential due to their potential effects on product efficacy and immunogenicity [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of SEC stationary phases, equipping scientists with the knowledge to select the appropriate phase for their specific application, including method validation for novel sensor technologies.

The Historical Progression of SEC Stationary Phases

The development of SEC stationary phases has traversed several distinct generations, each marked by significant improvements in material science and a deeper understanding of separation mechanics. The timeline below illustrates the key milestones in this evolutionary pathway.

The conceptual foundation for size-based separations was first established in the 1950s with the use of starch and early gels as packing materials. Lindqvist and Storgårds reported the first separation of biomolecules using starch, and Lathe and Ruthven further demonstrated the separation of proteins and peptides using maize starch, describing it as a "molecular sieve" effect [1]. While revolutionary, these materials suffered from low mechanical strength, leading to bed collapse at high linear velocities [1]. The 1960s saw the introduction of cross-linked dextrans, commercialized as Sephadex, which offered greater mechanical strength and became the standard for size-based protein separations for many years [1]. By varying the degree of cross-linking, manufacturers could control the pore size and thus the separation range. Other polymeric resins like polyacrylamide (Bio-Gel) and agarose were also introduced during this period [1] [2]. Despite these improvements, the soft polymeric resins remained prone to compression under pressure, limiting further reductions in particle size [1].

A significant leap occurred in the 1970s with the adoption of derivatized porous silica. Its superior mechanical strength and non-swelling nature allowed for the use of smaller particles, thereby enhancing chromatographic efficiency [1]. However, a major drawback was the strong ionic interaction between acidic surface silanols and proteins, which necessitated surface modifications and mobile phase additives [1]. Early modifiers included glyceropropylsilane and N-acetylaminopropylsilane, but these often introduced undesirable hydrophobic interactions with proteins [1]. The most successful surface modifier for silica, the diol functional group, was introduced during this era and is still valued for its minimal hydrophobic interactions [1]. The first-generation hybrid particles, introduced in 1999, represented a paradigm shift by combining organic and inorganic components [3]. Synthesized from tetraethoxysilane and methyltriethoxysilane, these methyl hybrid particles exhibited improved stability in alkaline mobile phases and reduced silanol activity compared to pure silica, resulting in better peak shapes for basic analytes [3]. Their main limitation was insufficient mechanical strength for the ultra-high pressures used in modern UHPLC systems [3]. This was addressed in 2004 with the second-generation hybrid particles, known as Bridged-Ethylene Hybrid (BEH) technology [1] [3]. These particles, synthesized using bridged silane precursors like 1,2-bis(triethoxysilyl)ethane, featured a more robust structure without sacrificing the beneficial hybrid properties. This made them suitable for smaller particle sizes (down to 1.7 μm) and capable of withstanding the high pressures (>6000 psi) of UHPLC systems, enabling faster and more efficient separations [1] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Stationary Phase Materials

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Different SEC Stationary Phase Materials

| Material Type | Relative Mechanical Strength | pH Stability Range | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Gels (Dextran, Agarose) | Low | 2-10 [1] | Minimal protein adsorption; high porosity for large biomolecules | Low pressure tolerance; bed compression; slow flow rates | Desalting; protein purification; separation of large biomolecules |

| Rigid Silica | High | 2-8 [3] | High efficiency; small particles possible; stable at high pressures | Strong ionic interactions with silanols; limited pH stability | Analysis of synthetic polymers (in organic solvents) |

| Diol-Modified Silica | High | 2-8 | Reduced hydrophobic interactions; improved peak shape vs. bare silica | Requires high ionic strength mobile phases to mask residual silanols | Standard SEC analysis of proteins and antibodies |

| 1st Gen Methyl Hybrid | Medium | 2-12 [3] | Reduced silanol activity; improved peak shape for bases; wider pH range than silica | Limited mechanical stability for UHPLC pressures | Method development for ionizable analytes; preparative purifications |

| 2nd Gen BEH Hybrid | High | 1-12 [3] | Superior mechanical strength; extended pH stability; high efficiency at UHPLC pressures | Higher cost than traditional silica | High-resolution SEC for proteins and mAbs; oligonucleotide analysis; UHPLC applications |

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for SEC Stationary Phase Characterization

| Characterization Parameter | Experimental Protocol | Soft Gels | Diol-Milica | BEH Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column Efficiency (Plate Count, N/m) | Inject a small, unretained molecule (e.g., acetone). Calculate N = 5.54 *(tR/w1/2)2, where tR is retention time and w1/2 is peak width at half height. Normalize for column length [4]. | Low | Medium-High | High |

| Resolution (Rs) | Inject a protein mixture (e.g., monomer/dimer). Calculate Rs = 2*(tR2-tR1)/(w1+w2), where w is the peak width at baseline [1]. | Moderate | Good | Excellent |

| Silanol Activity (Peak Asymmetry for Bases) | Inject a basic analyte (e.g., lidocaine) at neutral pH. Measure the peak asymmetry factor (As). A value of 1.0 indicates a symmetric peak [3]. | Not Applicable | Moderate (As > 1.2) | Low (As ≈ 1.0) |

| Pressure Tolerance | Gradually increase flow rate and record backpressure. Note the point of significant bed compression or pressure instability. | Low (< 500 psi) | High (> 6000 psi) | Very High (≥ 15,000 psi) |

| Aggregate Recovery | Inject a stressed protein sample and compare the peak areas of aggregates and monomers to a reference standard. Higher recovery indicates less surface adsorption [1] [5]. | High | Moderate-High | High |

The data in Table 1 and Table 2 highlight the clear performance trajectory from soft gels to modern hybrids. The primary challenge with early soft gels was their mechanical weakness, restricting their use to low-pressure systems and resulting in longer analysis times [1] [6]. The introduction of rigid silica was a breakthrough for efficiency and speed but introduced significant surface reactivity. Acidic silanols on the silica surface could cause ionic interactions with basic analytes, leading to peak tailing and inaccurate quantification—a critical issue when characterizing protein aggregates or using SEC for sensor validation [1] [3]. Diol-modified silica phases mitigated the hydrophobic interaction issue but still required mobile phase additives (e.g., salts at concentrations of 150 mM or higher) to suppress residual ionic interactions [1].

The advent of hybrid particle technology addressed these core limitations. The incorporation of organic moieties directly into the particle skeleton significantly reduced the number and acidity of surface silanols. This is evidenced by the superior peak symmetry (As ≈ 1.0) for basic analytes run at neutral pH, as shown in Table 2 [3]. Furthermore, the hybrid structure confers exceptional stability across a broad pH range (pH 1-12), providing chromatographers with a powerful tool for method development. The ability to operate at high pH can increase loading capacity for preparative applications and offers a unique selectivity parameter for separating ionizable analytes [3]. The second-generation BEH hybrid particles combined this superior chemistry with the mechanical strength required for UHPLC, enabling the use of sub-2-μm particles for fast, high-resolution separations without compromising column longevity [1] [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SEC Analysis

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for SEC Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Diol-Modified Silica Columns | Standard SEC columns with hydrophilic diol bonding; provide a good balance of performance and cost. | Routine analysis of protein aggregates and mAb monomers [1]. |

| BEH Hybrid SEC Columns | Advanced columns with organic-inorganic hybrid structure; offer high efficiency, low interaction, and wide pH stability. | High-resolution, high-speed SEC in UHPLC systems; analysis of sensitive biomolecules [1] [3]. |

| Mobile Phase Buffers | Aqueous buffers (e.g., phosphate, Tris) with added salt (150-250 mM) to mask residual surface charges on the stationary phase. | Essential for preventing ionic interactions and achieving true size-based separation in aqueous SEC [1] [5]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Monodisperse proteins or polymers with known molecular weights; used for column calibration. | Creating a calibration curve of log(MW) vs. retention volume to estimate sample molecular weight [1] [7]. |

| Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) Detector | An absolute detector that measures molecular weight independently of elution volume, eliminating the need for column calibration. | Determining absolute molecular weight and detecting aggregates in IgG-HRP conjugation reactions [5] [8]. |

Advanced Detection and Validation Strategies in SEC

For researchers validating self-produced sensors, employing advanced detection methods is crucial for obtaining absolute data that is not reliant on column calibration. The integration of multiple detectors provides a comprehensive characterization of the sample and the separation process. The workflow below outlines how these detectors function together in a multi-detection SEC system.

As illustrated, a refractive index (RI) detector is a concentration-sensitive bulk property detector, while a UV detector is a solute property detector that is particularly useful for proteins [2] [5]. The key advancement for absolute validation is the inclusion of a light scattering (LS) detector (MALS or RALS/LALS), which measures molecular weight directly at each elution slice without relying on calibration standards or retention time [5] [8]. This is critical for validating the performance of SEC columns and sensors, as it removes shape-dependent inaccuracies that can occur with conventional calibration. A viscometer detector provides intrinsic viscosity data, offering insights into macromolecular structure, conformation, and branching [5] [8].

The power of this multi-detection approach is exemplified in its application for monitoring a conjugation reaction, such as the preparation of an IgG-HRP conjugate. A 2023 study used multi-detection SEC to characterize starting materials, intermediates, and the final product in detail [5]. The methodology provided absolute molecular weight values (~153 kDa for IgG monomer, ~43 kDa for HRP, and ~235 kDa for the successful conjugate), polydispersity (Mw/Mn ≈ 1.003 for IgG, indicating homogeneity), and aggregate content for each species [5]. This level of characterization ensures that the conjugation process is accurately monitored and the final product is properly validated—a principle that applies directly to the validation of SEC-based sensors.

The evolution of SEC stationary phases, from the soft, compressible beds of starch to the robust, high-performance diol-modified hybrid particles, has been driven by the need for greater efficiency, speed, and most importantly, separation fidelity. For scientists engaged in the validation of self-produced sensors, the choice of stationary phase is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental decision that influences the accuracy of all subsequent data. Modern BEH hybrid particles with diol surfaces currently represent the state-of-the-art, offering minimal interaction, broad pH stability, and the mechanical strength required for high-resolution separations. When coupled with advanced detection methods like multi-angle light scattering, researchers possess a powerful toolkit for obtaining absolute molecular parameters, ensuring that their separations are based solely on size and that their sensors are validated against the most rigorous standards.

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), also historically known as gel-filtration chromatography or molecular sieve chromatography, is a fundamental technique for separating biomolecules based on their size in solution [1]. Unlike other chromatographic methods that rely on chemical interactions, SEC operates on a unique entropy-driven principle, making it particularly valuable for analyzing the native states of proteins, protein aggregates, and other large biomolecules without altering their structure [1]. For researchers validating self-produced sensors, SEC serves as a critical orthogonal method, providing a benchmark for size-based characterization due to its well-understood mechanism and reproducible results.

The Entropy-Driven Mechanism of SEC

Theoretical Foundation

The separation mechanism in SEC is fundamentally different from other chromatographic modes. In most chromatography, the enthalpy of adsorption (ΔH) is the dominant contributor to the overall change in free energy. SEC is unique because partitioning is driven almost entirely by entropic processes with no significant adsorption enthalpy [1].

The thermodynamic principle can be described by the equation:

ΔG⁰ = -RTlnK = ΔH⁰ - TΔS⁰

Where ΔG⁰ is the standard free energy change, R is the gas constant, T is absolute temperature, and K is the partition coefficient. For ideal SEC separations, ΔH = 0, simplifying the equation to:

ΔG⁰ = -TΔS⁰

This reveals that the driving force for separation is purely entropic (-TΔS⁰) [1]. The thermodynamic retention factor (K_D) represents the fraction of intraparticle pore volume accessible to the analyte:

KD = (VR - V0)/Vi

Where VR is the retention volume of the analyte, V0 is the interstitial volume, and Vi is the intra-particle volume [1]. KD ranges from 0 (analyte fully excluded from pores) to 1 (analyte fully accesses all pores).

Separation Process Visualization

Historical Development and Materials

The concept of size-based separations was first speculated by Synge and Tiselius, based on observations that small molecules could be excluded from zeolite pores [1]. The term "molecular sieve" was coined by J.W. McBain to describe this property [1]. The first separation of biomolecules by SEC was reported by Lindqvist and Storgårds, who separated peptides from amino acids on a column packed with starch [1]. Lathe and Ruthven subsequently performed extensive characterizations using potato or maize starch, demonstrating the separation of various compounds including proteins and peptides by the molecular sieve effect [1].

Modern SEC materials have evolved significantly:

- Dextran-based gels (Sephadex): Crosslinked with epichlorohydrin, providing greater mechanical strength than starch [1]

- Polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Gel): Commercialized by Bio-Rad for size-based separations [1]

- Porous silica: Provides superior mechanical strength but requires surface modifications to minimize ionic interactions [1]

- Hybrid particles: BEH particles with diol groups reduce silanol activity and allow smaller particle sizes down to 1.7μm [1]

Comparative Analysis of SEC and Alternative Techniques

Performance Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparative analysis of SEC and alternative size-based separation techniques

| Technique | Separation Mechanism | Effective Size Range | Analysis Time | Key Applications | Resolution Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography | Entropy-driven pore access | 1-1000 kDa [1] | 10-30 minutes [1] | Protein aggregation analysis, polymer separation [1] | Limited by column efficiency and pore volume [1] |

| Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis | Biased reptation in alternating electric fields | >10 kbp DNA [9] | 1-2 days [9] | Bacterial genotyping, large DNA separation [9] | Time-consuming, risk of DNA fragmentation [9] |

| Nanoslit Relaxation Analysis | DNA relaxation dynamics in confinement | >10 kbp DNA [9] | ~60 seconds [9] | Rapid DNA sizing, genotyping [9] | Requires specialized nanofluidic fabrication [9] |

| Analytical Ultracentrifugation | Sedimentation under centrifugal force | Broad range | Several hours | Orthogonal validation for SEC [1] | Equipment intensive, low throughput [1] |

| Asymmetric Flow Field Flow Fractionation | Cross-flow separation in channel | 1 kDa - 100 μm | 30-60 minutes | Protein complexes, nanoparticles [1] | Method development complexity [1] |

Experimental Resolution Data

Table 2: Experimental resolution comparison for DNA separation methods

| Method | Resolution Metric | Analysis Time | Sample Requirements | Fragmentation Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis | Standard reference method [9] | 24-48 hours [9] | Standard DNA preparation | High (repeated hooking and stretching) [9] |

| Nanoslit Relaxation (130 nm depth) | Partial separation of λ and T4 DNA [9] | ~60 seconds [9] | Minimal sample processing | Low (controlled stretching <30%) [9] |

| Nanoslit Relaxation (49 nm depth) | Resolution = 2.33 [9] | ~60 seconds [9] | Minimal sample processing | Very low [9] |

| Artificial Gel Nanostructures | Varies with constriction size [9] | 30 minutes [9] | Standard DNA preparation | Medium (frequent gel interactions) [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SEC Protocol for Protein Analysis

Column Preparation and Selection:

- Use diol-modified silica or hybrid particles (e.g., BEH technology) for minimal protein interaction [1]

- Column dimensions typically 7.8mm ID × 300mm with 1.7-5μm particle sizes [1]

- Equilibrate with 5-10 column volumes of mobile phase before analysis

Mobile Phase Requirements:

- Use aqueous buffers (e.g., phosphate, Tris) with 100-200mM NaCl to minimize ionic interactions [1]

- Maintain pH between 6.0-7.5 for most protein applications

- Filter through 0.22μm membrane and degas before use

Sample Preparation:

- Centrifuge samples at 10,000-15,000g for 10 minutes to remove particulates

- Match sample buffer composition to mobile phase to avoid viscosity artifacts

- Ideal injection volume: 1-5% of column volume for optimal resolution

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Flow rate: 0.5-1.0mL/min for analytical columns (4.6-7.8mm ID)

- Temperature: 15-25°C (minimal temperature effect on retention) [1]

- Detection: UV 280nm for proteins, or TOC detection for comprehensive analysis [10]

SEC Validation Methodology

Linearity and Range:

- Establish linear range using protein standards of known molecular weight

- Typical linear range: 1-10,000 μgC dm⁻³ for TOC detection [10]

- Correlation coefficient (R²) should exceed 0.995 for quantitative work

Precision and Accuracy:

- Repeatability: %RSD <2% for retention time, <5% for peak area [10]

- Intermediate precision: %RSD <5% over multiple days with different columns

- Accuracy: 85-115% recovery for known standards [10]

Limit of Detection and Quantification:

- LOD: Typically 19.0 μgC dm⁻³ for TOC detection [10]

- LOQ: Typically 3-5 times LOD, depending on detection method

HPSEC-TOC Protocol for Natural Organic Matter

Sample Preservation:

- Refrigerate samples immediately after collection

- Maximum storage duration: Two weeks [10]

- Avoid freezing and thawing cycles which alter NOM composition

Inorganic Carbon Removal:

- Acidify samples to pH 6.0 with minimal hydrochloric acid

- Purge with N₂ gas for 5-10 minutes [10]

- Verify complete IC removal by measuring TOC before and after treatment

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Preparative TSK HW-50S [10]

- Injection volume: 1350 mm³ [10]

- Mobile phase: Appropriate aqueous buffer matching sample ionic strength

- Detection: TOC via UV/persulfate oxidation [10]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for SEC analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diol-Modified Silica Columns | Size-based separation matrix | High mechanical strength, minimal protein interaction [1] | Protein aggregation analysis, monoclonal antibody characterization [1] |

| Hybrid BEH Particles | Advanced SEC stationary phase | Reduced silanol activity, 1.7μm particle size [1] | High-resolution protein separation [1] |

| TSK HW-50S Column | Semipreparative SEC separation | Optimized for natural organic matter [10] | HPSEC-TOC analysis of freshwater NOM [10] |

| Aqueous SEC Buffers | Mobile phase for biomolecules | 100-200mM NaCl, pH 6.0-7.5 [1] | Maintaining protein stability during analysis [1] |

| Protein Molecular Weight Standards | Column calibration and validation | Broad molecular weight range (1-670 kDa) [1] | Creating calibration curves, method validation [1] |

| TOC Detection System | Universal carbon detection | UV/persulfate oxidation method [10] | Comprehensive NOM analysis, non-UV absorbing compounds [10] |

Technological Advances and Future Directions

Recent advancements in SEC technology have focused on improving resolution, speed, and applicability to various biomolecules. The development of sub-2μm particles using hybrid technology has significantly enhanced chromatographic efficiency while maintaining mechanical stability [1]. The integration of multiple detection systems including TOC, UV, and light scattering provides comprehensive characterization in a single analysis [10].

For researchers validating self-produced sensors, SEC continues to provide the gold standard for size-based characterization due to its robust theoretical foundation, reproducibility, and minimal sample alteration during analysis. The entropy-driven mechanism ensures that biomolecules remain in their native state, providing confidence in size distribution measurements critical for sensor validation studies.

The experimental data demonstrates that while newer techniques like nanoslit relaxation analysis offer dramatic improvements in speed for specific applications like DNA analysis [9], SEC maintains its position as the most versatile and widely applicable method for broad-spectrum biomolecule separation and characterization.

In biopharmaceutical development, robust analytical methods are essential for characterizing protein therapeutics, ensuring their safety, efficacy, and quality. Protein aggregation can impact economic viability, reduce bioactivity, and increase immunogenicity because the recipient's immune system may recognize the protein complex as nonself [11]. Similarly, accurate determination of molecular weight (MW) and purity is critical, as these attributes influence biological activity and stability. This guide compares key analytical technologies, focusing on the role of Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) as a reference method for validating novel sensor-based approaches, such as biosensors and process analytical technology (PAT) tools [12] [13].

Technology Performance Comparison

The following analytical techniques are central to monitoring critical quality attributes (CQAs) in biopharmaceuticals. Their performance characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Protein Characterization

| Technique | Key Applications | Key Performance Metrics | Throughput & Ease of Use | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Soluble aggregate analysis and quantitation [11]; Oligomeric state determination [14]. | Robust and accurate for soluble aggregates (1–50 nm) [11]; Resolution depends on column pore size and mobile phase [11] [14]. | Requires skilled personnel and laboratory infrastructure; Can be automated for quality control [11]. | Risk of shear forces or column interactions altering sample [11]; Mobile phase composition significantly influences elution [14]. |

| Light Scattering (SLS/DLS) | Direct measurement of absolute molecular weight [14]; Estimation of second virial coefficient (B22) for aggregation propensity [14]. | Provides volume-averaged molar masses without calibration curves [14]; Sensitive to presence of large aggregates [14]. | Requires specific expertise for data interpretation. | Results are sensitive to sample quality and solution conditions. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) e.g., NIR, Raman Spectroscopy | Real-time monitoring of CPPs and CQAs [13]; In-line monitoring of tablet content uniformity [13]. | Enables proactive quality control and continuous process verification [13]. | High throughput; Suitable for in-line/on-line deployment in manufacturing [13]. | Requires complex model calibration and validation [13]; Data integration challenges [13]. |

| Biosensors | Detection of contaminants, pathogens, and additives [12]; Potential for intelligent packaging [12]. | High sensitivity and specificity [12]; Rapid response times [12]. | Amenable to portability and on-site use [12]. | Susceptible to matrix effects in complex samples [12]; Requires standardization for regulatory acceptance [12]. |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Polymer molecular weight analysis via solution viscosity correlation [15]. | Provides results within seconds [15]. | Rapid measurement; Minimal sample preparation [15]. | Primarily demonstrated for synthetic polymers; applicability to proteins may be limited. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Monitoring Protein Aggregation via SEC

SEC separates molecules based on their hydrodynamic size, making it ideal for resolving monomeric proteins from soluble aggregates like dimers and higher-order oligomers [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Column Selection: Use an SEC column with a pore size appropriate for the target protein's hydrodynamic radius. Columns with 150-300 Å pores are common for many proteins. Connecting columns in series can increase resolution [11].

- Mobile Phase Preparation: The mobile phase must preserve protein native state and prevent nonspecific interactions. A typical phase is 50 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride, pH 6.8. Note that ionic strength and pH can significantly impact elution volume and must be controlled [11] [14].

- Sample Preparation: Filter the protein sample using a 0.22 µm membrane to remove particulates. The injection concentration should be below the critical concentration to avoid viscosity effects and "macromolecular crowding" [7].

- System Setup and Calibration: Use an HPLC system with a UV detector (e.g., 280 nm). Calibrate the column using a protein standard mix with known molecular weights (e.g., thyroglobulin, IgG, ovalbumin) to create a log(MW) vs. elution volume curve [11] [14].

- Chromatographic Run: Inject the sample and run isocratically. Monitor the elution profile to identify the monomer peak and earlier-eluting aggregate peaks.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the percentage of monomer and aggregates based on the relative peak areas. For absolute molecular weight determination without calibration, couple SEC in-line with a static light scattering (SLS) detector [14].

Protocol 2: Validating SEC Method Accuracy

Accuracy validation is crucial when SEC is used for determining molecular weight distributions (MWD) and averages.

Detailed Methodology:

- Prepare a Polydisperse Reference Standard: Create a mixture of two well-characterized, monodisperse protein standards with certified molecular weights (M1 and M2). The mixture should mimic the Mw and Mn of the sample. Using equal weights of the two standards simplifies calculations and minimizes purity-related errors [7].

- Calculate True Values: The true number-average (Mn)t and weight-average (Mw)t molecular weights of the mixture are calculated using the equations:

- (Mn)t = 2 / (1/M1 + 1/M2)

- (Mw)t = (M1 + M2) / 2 [7]

- Analysis and Accuracy Calculation: Analyze the prepared standard using the SEC method. Determine the experimental molecular weight averages, (Mn)exp and (Mw)exp. Calculate the absolute error (AE) and relative error (%RE) to validate accuracy:

- (Mn)AE = (Mn)exp - (Mn)t

- %(Mn)RE = [(Mn)AE / (Mn)t] × 100% [7]

Protocol 3: Real-time Monitoring with PAT

PAT tools like NIR spectroscopy enable real-time monitoring during manufacturing.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sensor Integration: Integrate an NIR probe directly into the process stream, such as a bioreactor or a conduit in a continuous manufacturing line [13].

- Data Acquisition: Collect NIR spectra in real-time. The spectra result from molecular overtones and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds, providing chemical and physical information [13].

- Chemometric Modeling: Use multivariate calibration models (e.g., partial least squares, PLS) to correlate spectral data with reference values (e.g., protein concentration, aggregation index) obtained from primary methods like SEC [13].

- Process Control: The real-time data is fed into a process control system to enable dynamic adjustment of Critical Process Parameters (CPPs), ensuring consistent product quality [13].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

SEC Method Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in developing and validating a reliable SEC method.

PAT Integration for Real-Time Control

This diagram shows how PAT tools are integrated into a bioprocess for real-time monitoring and control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for SEC and Aggregation Analysis

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SEC Columns | Separates molecules by hydrodynamic size [11]. | Pore size (e.g., 150 Å, 300 Å) must match target protein size. Columns can be used in series for increased resolution [11]. |

| Protein Standards | Calibrates SEC system for molecular weight determination [7] [11]. | Use monodisperse standards (e.g., thyroglobulin, IgG) or prepared mixtures to validate accuracy [7]. |

| Mobile Phase Buffers | Dissolves and elutes samples under controlled conditions. | Composition (pH, ionic strength) is critical for accuracy and must be consistent, as it affects protein elution and stability [11] [14]. |

| Static Light Scattering (SLS) Detector | Provides direct, absolute measurement of molecular weight in-line with SEC [14]. | Bypasses need for calibration curves; allows detection of aggregates and calculation of virial coefficients [14]. |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Analyzer | Quantifies organic carbon in samples; used in specialized SEC for natural organic matter [16]. | Membrane-based conductivity provides specificity, meeting USP requirements for accuracy and validation [17]. |

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is a pivotal analytical technique within the biopharmaceutical industry, enabling the separation of biomolecules based on their hydrodynamic size [18]. This gentle, solution-based method is indispensable for characterizing critical quality attributes (CQAs) of therapeutic proteins, including monoclonal antibodies, biosimilars, and newer modalities like antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and gene therapy products [19] [20]. As a quality assurance tool, SEC provides essential data on aggregation, fragmentation, and oligomeric distribution throughout the biopharma workflow—from upstream process development to final product quality control and regulatory assessments for biosimilar approval [21] [22]. The technique's ability to maintain molecular integrity during analysis makes it particularly valuable for monitoring product stability and process consistency, forming a critical component of the quality-by-design (QbD) framework mandated by regulatory agencies worldwide [23] [24].

Fundamental Principles and Methodological Advancements in SEC

Core Separation Mechanism

SEC operates on the principle of differential partitioning between a mobile phase and porous stationary phase [18]. As a sample mixture travels through the column, smaller molecules diffuse into the pores of the packing material, thereby traversing a longer path, while larger molecules are excluded from these pores and elute first [18]. This process separates molecules in order of decreasing hydrodynamic size, with the total volume of the mobile phase in the column determining the separation efficiency [18]. The selection of appropriate pore sizes in the stationary phase is crucial for achieving optimal resolution for target analytes, whether analyzing monoclonal antibody monomers and aggregates or characterizing complex gene therapy products like recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) and mRNA [19].

Advanced SEC Platforms and Orthogonal Approaches

Recent technological innovations have significantly enhanced SEC capabilities. High-performance SEC (HPSEC) utilizing smaller particle sizes and higher pressures now provides improved resolution and faster analysis times [18]. The integration of multi-angle light scattering (MALS) detection with SEC allows for direct determination of molecular weight and size, independent of elution volume [22] [18]. Similarly, native SEC-mass spectrometry (nSEC-MS) has emerged as a powerful platform for characterizing labile biopharmaceuticals, enabling simultaneous separation and identification under non-denaturing conditions [20]. This approach has been successfully validated for quantifying critical attributes like drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) and drug load distribution (DLD) in cysteine-linked antibody-drug conjugates [20].

The concept of orthogonality—using techniques with different physicochemical principles to assess the same attribute—has become a regulatory expectation for biosimilar characterization [21] [23]. For size variants, SEC is typically complemented by analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) and field-flow fractionation techniques to provide a comprehensive size variant profile across different size ranges [21].

SEC Applications Across the Biopharmaceutical Workflow

Process Development and Optimization

During bioprocess development, SEC serves as a vital monitoring tool for evaluating cell culture conditions, purification parameters, and formulation stability. It enables researchers to track undesirable aggregation or fragmentation that may occur during various manufacturing steps, allowing for rapid process optimization [18]. Real-time SEC data facilitates informed decision-making regarding harvest timing, purification column loading, and buffer exchange procedures, ultimately ensuring consistent product quality [23]. The implementation of high-throughput SEC methods further accelerates this development cycle by enabling parallel assessment of multiple process conditions.

Quality Control and Stability Testing

In quality control environments, validated SEC methods are routinely employed for lot release testing and stability monitoring of biopharmaceutical products [20] [22]. These methods quantitatively measure the distribution of monomeric protein relative to high-molecular-weight aggregates and low-molecular-weight fragments, all of which represent CQAs with potential implications for product safety and efficacy [22]. As required by regulatory guidelines, SEC methods for QC applications must undergo rigorous validation demonstrating specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, and robustness according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [20] [22].

Table 1: SEC Validation Parameters for Quality Control Applications

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Approach | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Resolution of monomer, aggregate, and fragment peaks | Baseline separation (R > 1.5) between critical peak pairs |

| Accuracy/Recovery | Spiked samples with known concentrations | 95-105% recovery of monomeric protein |

| Precision | Repeatability (n=6) of same sample | RSD ≤ 2.0% for monomer percentage |

| Linearity | Series of standards across concentration range | R² ≥ 0.995 |

| Range | Concentrations demonstrating acceptable linearity, precision, accuracy | Typically 0.1-5 mg/mL for proteins |

| Robustness | Deliberate variations in flow rate, temperature, mobile phase | Consistent elution profile and monomer quantification |

Analytical Similarity Assessment of Biosimilars

SEC plays a foundational role in the comparative analytical assessment required for biosimilar development [21] [24]. According to the FDA's "totality-of-the-evidence" approach, comprehensive analytical characterization forms the base of the evidence pyramid for demonstrating biosimilarity [24]. SEC data on size variants contributes directly to establishing that a proposed biosimilar falls within the quality range established using multiple lots (typically 10-12) of the reference product [22]. This statistical approach captures the natural variability of the reference product while setting meaningful acceptance criteria for the biosimilar candidate [22].

Experimental Data and Case Studies

SEC Method Validation for Bevacizumab Biosimilar Development

A detailed SEC method validation study for bevacizumab analysis demonstrates the rigorous approach required in biosimilar assessment [22]. Researchers employed a Waters apparatus with a Protein KW-804 column and refractive index detection, using phosphate-buffered saline (300 mM NaCl, 25 mM phosphate, pH 7.0) as the mobile phase at 1.0 mL/min flow rate [22]. The method demonstrated excellent linearity (R² > 0.995) across the concentration range of 5-30 μg/mL, with precision showing RSD ≤ 0.35% for repeated injections [22]. The application of this validated method to multiple bevacizumab lots highlighted the importance of accounting for both analytical method variability and between-lot variability when establishing quality ranges for biosimilar assessment [22].

SEC Column Performance Comparison for Gene Therapy Products

A systematic evaluation of wide-pore SEC columns for characterizing gene therapy products revealed important performance considerations [19]. When analyzing rAAV serotypes, columns with pore sizes of 550-700 Å demonstrated optimal selectivity, though resolution was highly dependent on the specific serotype [19]. The DNACore AAV-SEC column showed particularly high efficiency (11,000 plates), attributed to its monodisperse 3 μm silica particles [19]. For mRNA analysis (1000-5000 nucleotides), the Biozen dSEC-7 LC column (700 Å) achieved the highest efficiency for smaller mRNA (~1000 nucleotides), while larger pore sizes were more appropriate for longer mRNA transcripts [19]. Despite these advancements, the study noted limitations in resolving low and high molecular weight species of mRNA across all tested columns, highlighting an area for continued technical development [19].

Table 2: SEC Column Performance for Different Biopharmaceutical Modalities

| Product Modality | Optimal Pore Size | Highest Performing Column | Key Separation Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies | 150-300 Å | Not specified in results | Resolving low-abundance aggregates from main monomer peak |

| rAAV Serotypes | 550-700 Å | DNACore AAV-SEC (11,000 plates) | Selectivity highly dependent on specific serotype |

| mRNA (≤1000 nts) | ~700 Å | Biozen dSEC-7 LC | Limited resolution of LMWS and HMWS |

| mRNA (>1000 nts) | >700 Å | Columns with larger pore sizes | Accurate quantification of impurities |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Operating Procedure for SEC Aggregate Analysis

Method: This protocol describes the quantitative determination of high-molecular-weight aggregates in therapeutic monoclonal antibodies using SEC with UV detection.

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with UV detection capability

- SEC column appropriate for mAb analysis (e.g., 150-300 Å pore size)

- Mobile phase: Phosphate-buffered saline (300 mM NaCl, 25 mM phosphate, pH 7.0)

- Protein reference standard

- Sample filtration unit (0.22 μm)

Procedure:

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Prepare phosphate-buffered saline (300 mM NaCl, 25 mM phosphate, pH 7.0), filter through 0.22 μm filter, and degas.

- System Equilibration: Equilibrate the SEC column with mobile phase at 1.0 mL/min until stable baseline is achieved (typically 30-60 minutes).

- System Suitability Test: Inject protein reference standard to confirm resolution (R > 1.5 between monomer and aggregate peaks), tailing factor (<2.0), and column efficiency (>5,000 plates/m).

- Sample Preparation: Dilute protein sample to 1-2 mg/mL in mobile phase, centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes, and transfer supernatant to HPLC vial.

- Chromatographic Analysis: Inject 25-50 μL of prepared sample, run isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min for 30 minutes with UV detection at 280 nm.

- Data Analysis: Integrate peaks corresponding to high-molecular-weight species, monomer, and low-molecular-weight species. Calculate percentage of each species based on relative peak area.

Validation Parameters: Establish specificity, linearity (1-5 mg/mL), precision (RSD < 2%), accuracy (90-110% recovery), and limit of quantitation (0.1% for aggregates) [22].

Native SEC-MS Workflow for ADC Characterization

Method: This protocol describes the characterization of drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) and drug load distribution in cysteine-linked antibody-drug conjugates using native SEC-MS.

Materials and Equipment:

- LC-MS system compatible with high molecular weight analysis

- SEC column with appropriate pore size for mAb separation

- Ammonium acetate buffer (100-200 mM, pH 6.5-7.5)

- ADC reference standard

Procedure:

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Prepare 200 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.0, using LC-MS grade water and acetic acid. Filter through 0.22 μm filter and degas.

- MS Parameter Optimization: Set ESI source to low fragmentation conditions (cone voltage 80-120 V, source temperature 100-150°C) to maintain non-covalent complexes.

- Chromatographic Conditions: Isocratic elution with 200 mM ammonium acetate at 0.2-0.3 mL/min for 5-10 minutes.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute ADC to 5-10 μg/mL in ammonium acetate buffer, centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Data Acquisition: Inject 5-10 μL of sample, monitor UV at 280 nm, and acquire MS data in positive ion mode with extended m/z range (500-4000 m/z).

- Data Analysis: Deconvolute mass spectra to determine average DAR and drug load distribution using vendor software [20].

Figure 1: Native SEC-MS Workflow for ADC Characterization

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SEC Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SEC Columns | Separation based on hydrodynamic size | Pore size selection critical: 150-300 Å for mAbs, 550-700 Å for rAAVs, 700-1000 Å for mRNA [19] |

| Mobile Phase Buffers | Maintain protein integrity during separation | Phosphate-buffered saline common; ammonium acetate for native MS compatibility [20] [22] |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Column calibration and method validation | Protein standards for biotherapeutics; polynucleotides for gene therapy products |

| Reference Standards | System suitability testing | Well-characterized biologics for qualifying method performance |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Buffer exchange and desalting | Essential for transferring samples into compatible SEC mobile phase |

Regulatory Considerations and Quality Metrics

SEC in Biosimilarity Assessment

Global regulatory agencies, including the FDA and EMA, emphasize the importance of comprehensive analytical comparison in biosimilar development [21] [24]. The FDA recommends a "stepwise" approach where analytical assessment forms the foundation, potentially reducing the need for extensive clinical studies if sufficient analytical similarity is demonstrated [24]. SEC data on size variants contributes significantly to this assessment, particularly when employing the quality range (QR) method that compares biosimilar product attributes against the natural variability of the reference product established using 10-12 lots [22]. This approach requires thorough method validation and understanding of both analytical method variability and between-lot variability of the reference product [22].

Quantitative Metrics for SEC Separation Quality

Assessing SEC separation quality requires appropriate metrics beyond traditional resolution calculations, particularly when dealing with asymmetric peaks or significant differences in peak abundance [25]. The peak-to-valley ratio is often more applicable than resolution for SEC separations where the abundance of high and low molecular weight species is much lower than the main monomer peak [25]. Recent research proposes a Separation Quality Factor (QS) incorporating five normalized terms: separation of peak pairs, peak elution window, separation impedance, peak symmetry, and signal-to-noise ratio [25]. This comprehensive metric enables more objective comparison of different SEC columns and conditions, supporting robust method development [25].

Figure 2: SEC Quality Metrics for Regulatory Compliance

Size-exclusion chromatography maintains a critical position within the biopharmaceutical analytical toolbox, providing essential data on size variants throughout the product lifecycle. As biotherapeutic modalities expand to include ADCs, gene therapies, and other complex molecules, SEC methodologies continue to evolve through advanced detection systems, improved column chemistries, and integration with complementary techniques like mass spectrometry. The demonstrated applications across process development, quality control, and biosimilar assessment underscore SEC's fundamental role in ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy. For biosimilar developers particularly, robust SEC methods generating high-quality comparative data form the analytical foundation supporting regulatory submissions under the totality-of-the-evidence approach. Continued refinement of SEC technologies and application-specific methodologies will further strengthen its contribution to biopharmaceutical development and quality assurance.

Integrating Self-Produced Sensors into Robust SEC Methods

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is an indispensable analytical technique for the separation and characterization of macromolecules based on their hydrodynamic volume. The strategic selection of SEC columns—dictated by pore size, particle size, and column dimensions—is fundamental to achieving optimal resolution for specific applications. For researchers validating self-produced sensors, the choice of SEC column directly impacts the accuracy and reliability of characterizing sensor materials or biological conjugates. The separation mechanism relies on the differential access of molecules to the porous network of the stationary phase; larger molecules elute first as they are excluded from pores, while smaller molecules penetrate pores and elute later. A profound understanding of how column parameters influence this separation is crucial for effective method development.

Recent research underscores that no single SEC column consistently provides the best separation across all sample types [19]. The performance is highly sample-dependent, necessitating a systematic approach to column selection. This guide objectively compares current SEC column technologies and provides supporting experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in making strategic choices that enhance resolution, efficiency, and data validity for their specific needs, including sensor validation workflows.

Core Column Parameters and Their Impact on Resolution

The resolution in SEC is governed by three primary physical parameters of the column: pore size, particle size, and the physical dimensions of the column itself. Each parameter interacts with the sample to determine the final separation quality.

Pore Size: The pore size of the stationary phase particles determines the molecular weight (MW) separation range. Molecules separate effectively when their size falls within the fractionation range of the pores. For instance, in gene therapy product characterization, optimal selectivity for recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) was found with columns having larger pore sizes of 550–700 Å, whereas for larger mRNAs (>1000 nucleotides), columns with even larger pore sizes (up to 1000 Å) were more appropriate [19]. Selecting a pore size matched to the hydrodynamic volume of the analytes is the first critical step.

Particle Size: The particle size of the packing material directly influences column efficiency and backpressure. Smaller particles generally provide higher efficiency (more theoretical plates) and better resolution but also generate higher system backpressure, requiring instrumentation capable of handling such pressures. A recent study comparing SEC columns for gene therapy products found that a column with monodisperse 3 µm silica particles achieved a high efficiency of 11,000 theoretical plates, whereas a column with 5 µm particles showed significantly lower efficiency (< 1000 plates) [19]. Advances in column technology have led to the proliferation of sub-2 µm particles for UHPLC-SEC, enabling faster and higher-resolution analyses.

Column Dimensions: The length and internal diameter (ID) of a column impact resolution, analysis time, and sample loading capacity. A longer column generally provides higher resolution but increases analysis time and backpressure. Shorter columns enable faster analysis, ideal for high-throughput environments. Sample loading is typically limited to a maximum of 1% of the total column volume [26]. For analytical applications, common dimensions include 7.8 mm ID x 30 cm L, with a typical sample load of 15-150 µL of a 1-10 mg/mL solution. For narrower 4.6 mm ID columns, the load decreases to 1-10 µL of a similar concentration [26].

Table 1: Effect of Core SEC Column Parameters on Separation

| Parameter | Primary Impact | Effect on Resolution | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pore Size | Determines MW separation range | Highest when analyte size is within the fractionation range | Match pore size to analyte's hydrodynamic volume; not all pore sizes work for all analytes [19] [26]. |

| Particle Size | Influences column efficiency (theoretical plates) | Smaller particles generally increase resolution | Balance higher resolution (smaller particles) with system pressure capabilities [19]. |

| Column Length | Impacts theoretical plates and analysis time | Longer columns increase resolution | Weigh need for resolution against longer run times and higher backpressure [26]. |

| Column Internal Diameter (ID) | Affects sample loading capacity | Minimal direct effect, but overloading causes poor resolution | Do not exceed 1% of total column volume; scale load with column ID [26]. |

Comparative Performance Data for Different Applications

The performance of SEC columns varies significantly across different application domains, such as biologics, gene therapies, and synthetic polymers. Below, we summarize key experimental findings from a systematic comparison of wide-pore SEC columns for characterizing gene therapy products, which provides a model for objective evaluation.

A 2025 study published in the Journal of Chromatography A systematically evaluated a new generation of wide-pore SEC columns for analyzing messenger RNA (mRNA) and recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) [19]. The research offers critical, data-driven insights for column selection.

For rAAV Serotypes: Among six tested SEC columns with pore sizes from 450 to 700 Å, the DNACore AAV-SEC column, packed with monodisperse 3 µm silica particles, demonstrated the highest efficiency with approximately 11,000 theoretical plates. This was attributed to its small, uniform particle size. In contrast, the SRT SEC-500 column, with 5 µm particles, showed the lowest efficiency (< 1000 plates). The study concluded that columns with larger pore sizes (550–700 Å) provided optimal rAAV selectivity. However, a crucial finding was that the final resolution for different rAAV serotypes was highly sample-dependent, with no single column consistently providing the best separation across all variants [19].

For mRNA Analysis: The study evaluated five columns with pore sizes from 700 to 1000 Å. The Biozen dSEC-7 LC (700 Å) column systematically achieved the highest efficiency and was particularly well-suited for analyzing smaller mRNA of around 1000 nucleotides. For larger mRNAs exceeding 1000 nucleotides, columns with larger pore sizes were more appropriate. A significant limitation noted across all tested columns was the challenge in accurately separating and quantifying low and high molecular weight species (LMWS and HMWS) of mRNA, which affects integration and quantification accuracy [19].

Table 2: SEC Column Performance in Gene Therapy Product Characterization [19]

| Analyte | Optimal Pore Size | High-Performing Column Example | Key Performance Metric | Limitations Noted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAAV Serotypes | 550 - 700 Å | DNACore AAV-SEC | ~11,000 theoretical plates | Resolution highly sample-dependent; no single column was universally best. |

| Small mRNA (~1000 nts) | ~700 Å | Biozen dSEC-7 LC | Systematically highest efficiency | Accurate separation and quantification of LMWS/HMWS remained limited. |

| Large mRNA (>1000 nts) | >700 Å (up to 1000 Å) | Columns with larger pore sizes | More appropriate for size | Accurate separation and quantification of LMWS/HMWS remained limited. |

Experimental Protocols for SEC Column Evaluation

Adopting a standardized experimental approach is vital for objectively comparing SEC columns and validating their performance for a specific application, such as characterizing sensor-biomolecule conjugates. The following protocols outline key methodologies for system testing and accuracy validation.

Protocol 1: System Performance Testing with Protein Standards

This protocol assesses the basic performance and efficiency of an SEC system and column using a characterized protein standard mixture.

- Principle: A mixture of well-defined proteins of different molecular weights is injected onto the SEC column. The elution profile is used to calculate the number of theoretical plates, a key indicator of column efficiency [26].

- Materials:

- SEC System: HPLC or UHPLC system with UV detection.

- Mobile Phase: Aqueous buffer, e.g., 100 mM phosphate buffer with 100 mM Na₂SO₄ or NaCl, pH 6.8 [26].

- Protein Standard: Commercially available SEC protein standard mixture (e.g., Merck/Sigma SEC Protein Standard 15–600 kDa or BioRad Protein Standard) [26].

- Procedure:

- Equilibrate the column with at least 5 column volumes of mobile phase at the intended flow rate.

- Prepare the protein standard according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Inject the recommended volume (e.g., 15-150 µL for a 7.8 mm ID column) [26].

- Run the separation method and record the chromatogram.

- Identify a well-resolved, late-eluting peak (e.g., vitamin B12 or p-aminobenzoic acid) for plate count calculation.

- Calculate the number of theoretical plates (N) using the formula specified for your region (US, EU, Japan differ), where N = 16*(tᵣ/W)², tᵣ is the retention time of the peak, and W is the peak width at the baseline [26].

Protocol 2: Accuracy Validation Using Polydisperse Standards

This advanced procedure, adapted from established validation methodologies, determines the accuracy of an SEC method for determining molecular weight distributions [7].

- Principle: A polydisperse reference standard is prepared by mixing two monodisperse standards with certified molecular weights. The accuracy of the SEC method is calculated by comparing the experimental molecular weight averages (Mₙ and M_w) against the known "true" values of the prepared mixture [7].

- Materials:

- Two monodisperse polymer or protein standards with known molecular weights (M₁ and M₂).

- Analytical balance, appropriate solvents, and volumetric flasks.

- Procedure:

- Generate an SEC calibration curve using primary or secondary monodisperse standards.

- Analyze representative samples to obtain average Mₙ and Mw values.

- Calculate the required M₁ and M₂ for a two-component mixture that matches the sample's Mₙ and Mw using the formulas for an equal-weight mixture [7]:

- Mₙ = 2 / (1/M₁ + 1/M₂)

- Mw = (M₁ + M₂) / 2

- Weigh equal amounts of the two selected monodisperse standards to create the validation mixture.

- Analyze the prepared standard in triplicate using the SEC method.

- Determine the experimental (Mₙ)ₑₓₚ and (Mw)ₑₓₚ.

- Calculate the percent accuracy (relative error) for Mₙ and M_w [7]:

- % (Mₙ)ᴿᴱ = |(Mₙ)ₜ - (Mₙ)ₑₓₚ| / (Mₙ)ₜ * 100%

- % (Mw)ᴿᴱ = |(Mw)ₜ - (Mw)ₑₓₚ| / (Mw)ₜ * 100% where subscript 't' denotes the true (calculated) value.

Strategic Selection Workflow and Critical Considerations

Integrating the parameters and data, the following workflow provides a logical, stepwise strategy for selecting an SEC column to achieve optimal resolution. This process is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: A strategic workflow for selecting an SEC column to achieve optimal resolution. The process begins with analyte and solvent identification and proceeds through critical choices of matrix, pore size, and physical parameters before final method validation.

Key Decision Factors in the Workflow

Analyte & Solvent → Base Matrix: The chemical nature of the analyte and the required solvent dictate the base matrix of the stationary phase. Silica-based columns (e.g., TSKgel SW-type) are robust and efficient but may require specific mobile phases to minimize secondary interactions with the silica surface. They can often tolerate a percentage of organic solvent. Polymer-based columns (e.g., TSKgel PW-type) are more inert, offering superior compatibility with alkaline pH conditions, making them suitable for applications like oligonucleotide analysis [26].

Pore Size Selection: The molecular weight or size of the analyte is the primary guide for pore size selection. Vendors provide molecular weight ranges for their columns. It is critical to remember that SEC separates by hydrodynamic volume, not molecular weight. Therefore, the calibration curve should be constructed using standards that are structurally similar to the analyte (e.g., use protein standards for proteins, dextrans for polysaccharides) for accurate molecular weight estimation [26].

Mobile Phase Optimization: The mobile phase in SEC is not merely a carrier; it is crucial for suppressing unwanted secondary interactions (electrostatic, hydrophobic) between the analyte and the stationary phase. To minimize these interactions and achieve a pure size-based separation, use a buffer with an ionic strength ≥ 200 mM (e.g., 100 mM phosphate buffer plus 100 mM Na₂SO₄) [26]. For silica-based columns, conditioning with successive injections of a protein like BSA (e.g., 4x 100 µg) can saturate active sites and improve protein recovery [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A well-equipped SEC laboratory requires more than just a column. The following reagents and materials are essential for method development, system calibration, and routine performance testing.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SEC Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Standards Mix | System performance testing and calibration | Merck/Sigma SEC Protein Standard (15-600 kDa) for calculating theoretical plates and calibrating for protein analysis [26]. |

| Monodisp Polymer Stds | Accuracy validation of MW determination | Narrow dispersity polymers (e.g., PEGs) used to create polydisperse standards for validating SEC method accuracy per published protocols [7]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Column conditioning | Successive injections of BSA (e.g., 4x 100 µg) saturate active sites on silica-based SEC columns, improving recovery of analytical proteins [26]. |

| High-Purity Buffers & Salts | Mobile phase preparation | Phosphate buffers with Na₂SO₄ or NaCl (~200 mM total ionic strength) suppress secondary interactions for a pure SEC separation [26]. |

| Pore Size Calibration Kits | Column characterization and selection | Sets of standards with known molecular weights and sizes used to establish the calibration curve and fractionation range of a new column [26]. |

The strategic selection of SEC columns is a multidimensional process that balances pore size, particle size, and column dimensions against the specific characteristics of the target analyte and the requirements of the analytical method. As demonstrated by recent comparative studies, performance is highly application-specific, necessitating an informed and often empirical approach to selection [19]. For researchers validating self-produced sensors, a rigorous, protocol-driven evaluation of SEC columns—assessing efficiency, resolution, and accuracy—is paramount. By leveraging the workflows, performance data, and experimental protocols outlined in this guide, scientists can make objective, data-backed decisions that ensure optimal SEC resolution, thereby enhancing the reliability and credibility of their characterization data.

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is a powerful technique for the separation and characterization of macromolecules based on their hydrodynamic volume. However, the ideal performance of SEC relies on a pure size-based separation mechanism. The presence of non-size effects, such as hydrophobic or ionic interactions between the analyte and the stationary phase, can severely compromise the accuracy of molecular weight determination. These aberrant interactions lead to skewed retention times, altered elution volumes, and ultimately, inaccurate molecular weight data. Consequently, the meticulous optimization of the mobile phase is not merely an improvement but a fundamental requirement for generating valid, reproducible results in SEC. For researchers validating self-produced sensors, where data fidelity is paramount, controlling these parameters is critical. This guide provides a systematic, data-driven approach to mobile phase optimization, balancing ionic strength, pH, and buffer composition to suppress non-size effects and achieve true size-based separations.

Fundamentals of Non-Size Effects in SEC

In an ideal SEC separation, molecules traverse the column packed with a porous medium, and their retention is governed solely by their ability to access the pore volume. Larger molecules that cannot enter the pores elute first, while smaller molecules that can penetrate the pores are retained longer. This process creates a calibration curve where the logarithm of molecular weight is inversely proportional to the elution volume [27].

Non-size effects disrupt this ideal behavior. The two most common types are:

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Occur between non-polar regions of the analyte and the stationary phase, leading to increased retention beyond what is expected based on size.

- Ionic Interactions: Occur between charged groups on the analyte and ionic sites on the stationary phase. These can cause either unwanted retention (attraction) or exclusion (repulsion), distorting the chromatogram.

The primary goal of mobile phase optimization is to create an environment that effectively masks these non-size effects, allowing the inherent size-exclusion mechanism to dominate the separation process.

Core Mobile Phase Parameters and Optimization Strategies

The composition of the mobile phase is the most critical tool for mitigating non-size effects. The following table summarizes the key parameters, their impact on separation, and optimization targets.

Table 1: Key Mobile Phase Parameters for Minimizing Non-Size Effects

| Parameter | Primary Function | Effect on Non-Size Interactions | Typical Optimization Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Strength | Modulates electrostatic interactions between analyte and stationary phase. | High ionic strength shields charges, suppressing ionic interactions. | 0.1 - 0.5 M for salts like NaCl [28] [7] |

| pH | Controls the charge state of the analyte and stationary phase surface. | Adjusting pH away from the analyte's isoelectric point (pI) can increase charge repulsion; matching pH can minimize attractive forces. | pH 6.0 - 8.0 for many biomolecules; specific to analyte pI [28] |

| Buffer Composition | Provides buffering capacity to maintain stable pH and can directly influence interactions. | Choice of buffer ions (e.g., phosphate, Tris, ammonium acetate) can affect specific binding and MS-compatibility. | 10 - 100 mM for adequate buffering capacity [28] |

| Organic Modifiers | Modifies the polarity of the mobile phase. | Low percentages (e.g., 1-5%) of acetonitrile or methanol can disrupt hydrophobic interactions. | < 5% to avoid altering stationary phase or denaturing proteins |

Optimizing Ionic Strength

Ionic strength is paramount for suppressing electrostatic non-size effects. The dissolved salts in the mobile phase provide counterions that shield electrostatic attractions between the analyte and the stationary phase.

- Experimental Protocol for Ionic Strength Titration:

- Prepare a series of mobile phases with a constant pH and buffer concentration but varying concentrations of a neutral salt like sodium chloride (e.g., 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 M).

- Inject a standard protein or polymer mixture with known molecular weights and varied pIs.

- Monitor the elution volume of each standard. As ionic strength increases, the elution volumes of analytes affected by ionic interactions will shift.

- The optimal ionic strength is the lowest concentration at which elution volumes become constant and align with the expected molecular weight calibration curve [28] [7].

Optimizing pH

The pH of the mobile phase determines the net charge of proteins and the ionization state of silica-based stationary phases.

- Experimental Protocol for pH Scouting:

- Prepare mobile phases with a constant ionic strength and buffer concentration across a relevant pH range (e.g., pH 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0).

- Use buffers with good buffering capacity in the target range (e.g., phosphate for 6-8, acetate for 4-5.5).

- Inject the standard mixture and analyze the chromatograms for peak shape, symmetry, and retention time.

- The optimal pH is often one where the analyte and stationary surface carry the same charge, leading to electrostatic repulsion rather than attraction, or where the analyte is highly charged to minimize hydrophobic interactions [28].

Balancing Buffer Composition and Additives

The buffer system must maintain a stable pH while being compatible with the analytes and detection system (e.g., mass spectrometry).

- Volatile Buffers for MS-Compatibility: For hyphenation with mass spectrometry, volatile salts like ammonium acetate or ammonium bicarbonate are essential. Research on ion-exchange chromatography of monoclonal antibodies has shown that a mixture of 50 mM ammonium acetate and 50 mM ammonium carbonate can provide sufficient ionic strength and buffering capacity while being fully MS-compatible [28].

- Additives for Hydrophobicity: For analytes with significant hydrophobic character, adding 2-5% methanol or acetonitrile can improve peak shape and recovery. The use of additives like 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for proteins or amines for basic compounds is common in other chromatographic modes and can be carefully evaluated in SEC, though they may influence the stationary phase [29].

Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

The following table synthesizes experimental data from published studies to illustrate the impact of mobile phase conditions on key SEC performance metrics.

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Data on Mobile Phase Optimization

| Analyte | Mobile Phase Condition A | Mobile Phase Condition B | Observed Effect (A vs. B) | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies [28] | 10-40 mM Ammonium Acetate/Carbonate (Low Ionic Strength) | 50/50 mM Ammonium Acetate/Carbonate (≥70 mM Ionic Strength) | Condition A: Poor peak shape, variable retention. Condition B: Improved peak shape, stable retention, good MS signal. | Total ionic strength should be >70 mM for proper elution and peak shape of proteins. |

| Polydisperse Polymer Standards [7] | Sub-optimal ionic strength/pH | Optimized ionic strength/pH | Accurate determination of Mn and Mw requires mobile phases that suppress non-size effects for validation. | Mobile phase optimization is critical for accuracy validation in SEC. |

| Pharmaceutical/Cosmetic Compounds [30] | Various SFC mobile phases on Cyanopropyl (CN) column | Same compounds on other stationary phases | The CN stationary phase in SFC showed the best correlation between retention and skin permeability, highlighting the role of stationary phase selection. | The stationary phase itself is a key variable in controlling interactions. |

A Workflow for Systematic Mobile Phase Optimization

The following diagram maps the logical sequence of experiments for a structured approach to mobile phase optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and materials required for the experimental protocols described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SEC Mobile Phase Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Salts (NaCl, KCl, (NH₄)₂CO₃) | Adjusts ionic strength to suppress electrostatic interactions. | General purpose SEC for proteins and polymers. |

| MS-Compatible Volatile Salts (Ammonium Acetate, Formate) | Provides ionic strength for MS detection; avoids ion source contamination. | SEC-MS hyphenation for protein therapeutic characterization [28]. |

| Buffering Agents (Phosphate, Tris, Acetate) | Maintains stable pH throughout the separation. | Controlling charge state of analytes and stationary phase. |

| HPLC-Grade Organic Modifiers (Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions between analyte and stationary phase. | Improving peak shape and recovery of hydrophobic proteins/peptides. |

| Narrow-Disperse Molecular Weight Standards | Calibrates the SEC system and validates the suppression of non-size effects. | Accuracy validation of the final SEC method [7] [27]. |

The validation of self-produced sensors and the acquisition of reliable macromolecular characterization data in SEC are inextricably linked to the mastery of mobile phase optimization. Non-size effects pose a significant threat to data integrity, but they can be systematically identified and suppressed. By understanding the roles of ionic strength, pH, and buffer composition, and by employing a structured experimental workflow, researchers can achieve robust, reproducible SEC methods. The experimental data and protocols provided here serve as a foundation for developing mobile phases that ensure separations are governed by size alone, thereby solidifying the credibility of subsequent scientific conclusions.

Sensor integration is a foundational process in modern scientific laboratories, particularly for researchers and scientists in drug development who rely on precise, reliable data. The process involves combining various sensors into a unified system to gather, share, and analyze environmental data, enabling intelligent decision-making [31]. Within the specific context of validating self-produced sensors—such as those for monitoring critical parameters in Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) systems—a structured protocol ensures that the collected data is accurate, reproducible, and fit-for-purpose. This guide provides a step-by-step protocol for sensor integration, from physical connection to data acquisition, and objectively compares the performance of different sensor integration approaches with supporting experimental data.

Section 1: Foundational Concepts of Sensor Integration

What is Sensor Integration?

Sensor integration is the process of combining different types of sensors into a single, cohesive system. This allows devices to collect comprehensive information from the environment, analyze it, and make autonomous decisions based on the synthesized data. In an SEC lab setting, this could involve integrating temperature, pressure, and flow sensors to monitor and control chromatographic conditions in real-time [31].

The Critical Role of Sensor Performance Metrics

When integrating sensors, especially for validation purposes, understanding key performance metrics is essential. These metrics allow for the quantitative comparison of sensor quality and are vital for validating self-produced sensors against reference instruments.

- Accuracy: Refers to how close a sensor's measurement is to the true or target value. It is assessed by comparing the sensor's readings with those from a reference-grade instrument [32].

- Precision: Describes the consistency and repeatability of measurements. A precise sensor will produce similar results when the same quantity is measured multiple times, even if those results are not perfectly accurate [32].

- Reproducibility: A specific aspect of precision, reproducibility is determined by placing multiple sensors of the same kind in one location and observing how much their measurements differ from one another [32].

A clear example of these concepts is sensor drift, where a sensor's measurements progressively deviate from the reference over time. This indicates declining accuracy, even if the sensor maintains high precision and reproducibility. Such drift can often be corrected with compensation algorithms, highlighting the importance of ongoing validation [32].

Section 2: A Step-by-Step Sensor Integration Protocol

Step 1: Sensor Selection and Compatibility Check

The first step is choosing the correct sensor for your application.

- Define the Use Case: Clearly identify what needs to be measured (e.g., temperature, pressure, vibration) and the environmental conditions it will operate in [33].

- Match Sensor to Application: For an SEC lab, you might need temperature sensors for column ovens or pressure sensors for pump monitoring. Ensure the sensor's accuracy, resolution, response time, and durability meet the experimental requirements. Industrial-grade sensors are often necessary for harsh environments [33].

- Verify Hardware & Software Compatibility: Ensure the sensor is compatible with your existing gateways, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), or microcontrollers. Check communication interfaces and protocols from the outset [33].

Step 2: Establishing Physical and Communication Connections

The method of connecting the sensor to your data system depends on the application's needs for speed, complexity, and distance.

- Direct Connection: This method involves a direct link between the sensor and a microcontroller (e.g., via I2C, SPI, UART). It is ideal for applications demanding rapid responses, such as triggering an immediate alarm or control action [34].

- Gateway-Based Integration: In this scenario, multiple sensors connect to a central gateway device. The gateway collects and processes data before transmitting it to a cloud or central system. This approach is excellent for managing diverse sensors from various manufacturers and is well-suited for complex SEC setups where sensors are scattered [34].