Validating Coordination Geometry Models: From Molecular Structures to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review addresses the critical process of validating computational models for coordination geometry, with specific emphasis on applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Validating Coordination Geometry Models: From Molecular Structures to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical process of validating computational models for coordination geometry, with specific emphasis on applications in biomedical research and drug development. We explore foundational principles distinguishing verification from validation, present cutting-edge methodological approaches including combinatorial algorithms and Zernike moment descriptors, and provide systematic troubleshooting frameworks for optimizing model parameters and addressing numerical instabilities. The article further establishes rigorous validation hierarchies and comparative metrics for assessing predictive capability across biological systems. By synthesizing these elements, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework to enhance model credibility, ultimately supporting more reliable computational predictions in pharmaceutical applications and clinical translation.

Fundamental Principles of Computational Model Validation in Biomedical Research

In the realm of computational modeling and simulation, particularly within coordination geometry research and pharmaceutical development, two distinct but complementary processes form the bedrock of credible scientific practice: verification and validation. These methodologies address fundamentally different questions that determine the success and reliability of computational predictions. Verification answers the question "Are we solving the equations correctly?" by assessing the numerical accuracy of computational solutions and their correct implementation. In contrast, validation addresses "Are we solving the correct equations?" by evaluating how accurately computational results represent real-world phenomena through comparison with experimental data [1] [2].

This distinction carries profound implications for drug discovery and materials science, where computational models increasingly guide experimental design and resource allocation. The integration of verification and validation processes, often termed VVUQ (Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification), provides a systematic framework for assessing computational model credibility [1]. As computational approaches expand into new domains—from predicting protein-ligand binding geometries to optimizing nanoparticle delivery systems—rigorous application of these principles becomes essential for translating computational predictions into reliable scientific insights and therapeutic innovations.

Theoretical Framework: Core Concepts and Definitions

The Fundamental Dichotomy

Verification and validation serve distinct but interconnected purposes in computational science. Verification is fundamentally a mathematics activity focused on identifying and quantifying errors in the computational model and its solution [2]. It ensures that the governing equations are solved correctly, without considering whether these equations accurately represent physical reality. This process involves checking code correctness, numerical algorithm implementation, and solution accuracy against known benchmarks.

Validation, conversely, constitutes a physics activity that assesses the computational model's accuracy in representing real-world phenomena [2]. It determines the degree to which a model corresponds to experimental observations under specified conditions. Where verification deals with the relationship between a computational solution and its mathematical model, validation addresses the relationship between computational results and experimental data, bridging the virtual and physical worlds.

Hierarchical Methodology

A hierarchical, building-block methodology provides the most effective framework for validation of complex systems [2]. This approach segregates and simplifies physical phenomena and coupling effects, enabling step-by-step assessment of model components before evaluating integrated system performance. For coordination geometry research, this might involve validating:

- Component-level models of molecular interactions

- Subsystem models of binding site behavior

- Integrated system models of complete molecular assemblies

This systematic decomposition allows researchers to identify specific model deficiencies and focus improvement efforts where they will have greatest impact on predictive capability.

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Verification and Validation

| Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | Are we solving the equations correctly? | Are we solving the right equations? |

| Fundamental Nature | Mathematics activity | Physics activity |

| Error Focus | Prevention of implementation and numerical errors | Detection of modeling errors in representing reality |

| Comparison Basis | Highly accurate analytical or numerical solutions | Experimental data with quantified uncertainties |

| Relationship | Between computational solution and mathematical model | Between computational results and physical reality |

Methodological Approaches: Techniques and Procedures

Verification Methods and Procedures

Verification encompasses two primary activities: code verification and solution verification. Code verification assesses whether the mathematical model is correctly implemented in software, typically through comparison with analytical solutions or highly accurate numerical benchmarks [2]. Solution verification evaluates the numerical accuracy of a specific computed solution, typically through grid refinement studies and error estimation.

Common verification techniques include [3] [4]:

- Requirements Reviews: Evaluating requirement documents for completeness and testability

- Design Reviews: Systematically examining software design artifacts for logical correctness

- Code Reviews: Peer examination of source code to identify implementation errors

- Static Code Analysis: Automated analysis of source code without execution

- Unit Testing: Verifying individual software components in isolation

- Traceability Checks: Ensuring all requirements have corresponding implementation and test coverage

For computational geometry research, verification might involve testing numerical integration algorithms against known analytical solutions or verifying that force field calculations maintain specified precision across different molecular configurations.

Validation Methods and Procedures

Validation employs a fundamentally different set of methodologies focused on comparison with experimental data. The validation process typically involves [4]:

- Experimental Design: Creating validation experiments specifically for model assessment

- Uncertainty Quantification: Characterizing both experimental and computational uncertainties

- Validation Metrics: Developing quantitative measures of agreement between models and data

- Statistical Comparison: Applying statistical methods to assess significance of differences

Validation experiments differ fundamentally from traditional experiments in their focus on providing comprehensive data for model assessment, including detailed characterization of boundary conditions, initial conditions, and system parameters [2]. For coordination geometry research, this might involve comparing computationally predicted binding affinities with experimentally measured values across a range of molecular systems.

Table 2: Methodological Comparison Between Verification and Validation

| Methodological Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Techniques | Code reviews, static analysis, unit testing, analytical solutions | Experimental comparison, uncertainty quantification, statistical analysis |

| Timing in Workflow | Throughout development process; precedes validation | Typically follows verification; requires stable, verified implementation |

| Key Artifacts | Requirements documents, design specifications, source code | Experimental data, validation metrics, uncertainty estimates |

| Success Criteria | Correct implementation, numerical accuracy, algorithmic precision | Agreement with experimental data within quantified uncertainties |

Practical Implementation: Workflows and Visualization

Integrated VVUQ Workflow

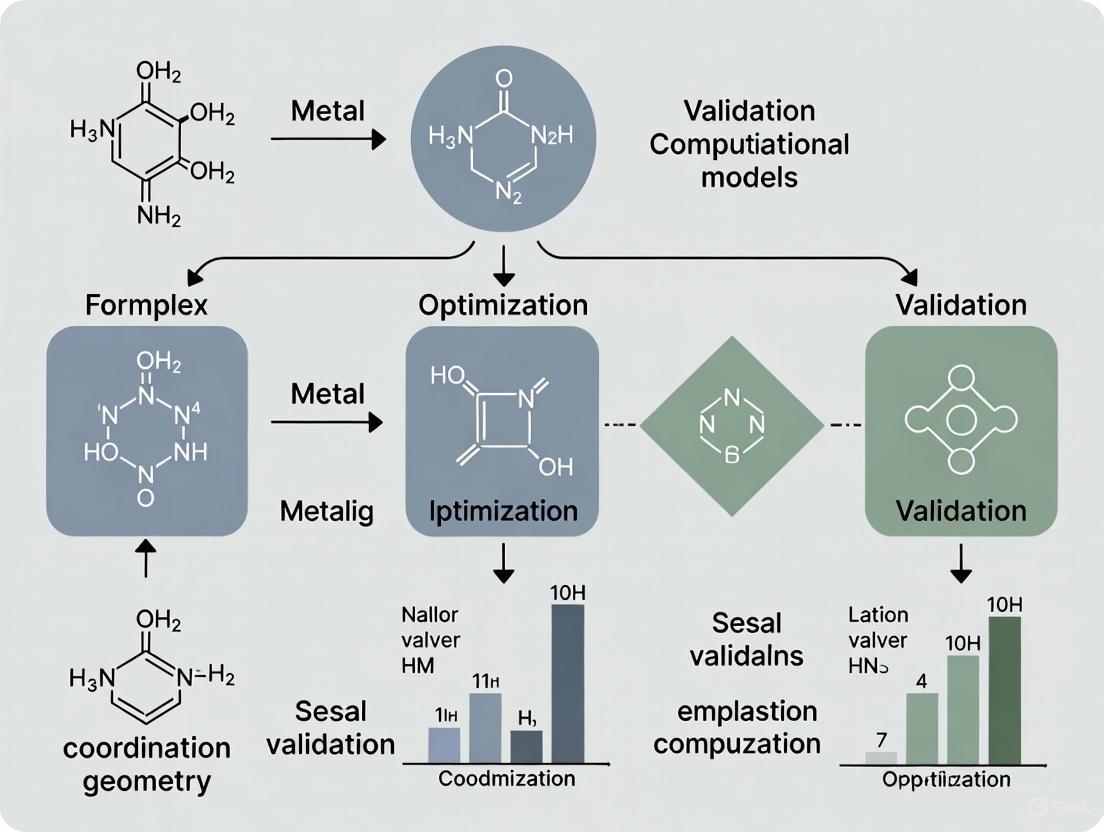

The following diagram illustrates the integrated relationship between verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification in computational modeling:

Diagram 1: Integrated VVUQ Workflow in Computational Modeling. This diagram illustrates the relationship between real-world systems, mathematical and computational models, and the roles of verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification (UQ) in establishing model credibility.

Hierarchical Validation Methodology

Complex systems require a structured, hierarchical approach to validation, as illustrated in the following workflow:

Diagram 2: Hierarchical Validation Methodology for Complex Systems. This structured approach validates model components at multiple levels of complexity, building confidence from fundamental physics to integrated system performance.

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Research

AI-Enhanced Drug Discovery

The distinction between verification and validation becomes particularly critical in AI-driven drug discovery, where computational models directly influence experimental priorities and resource allocation. AI platforms now achieve remarkable performance, with >75% hit validation in virtual screening and ability to design protein binders with sub-Ångström structural fidelity [5]. These capabilities dramatically accelerate therapeutic development, but their reliability depends on rigorous VVUQ processes.

In small-molecule discovery, AI-driven workflows have reduced discovery timelines from years to months while maintaining or improving hit quality [5]. For example, conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) frameworks have generated molecules with specific binding properties, with several candidates progressing to IND-enabling studies [5]. Such accelerated discovery depends on both verification (ensuring algorithms correctly implement molecular generation and optimization) and validation (confirming predicted molecules exhibit desired binding behavior experimentally).

Digital Twins in Pharmaceutical Development

Digital Twins (DTs) represent a groundbreaking application of computational modeling that relies extensively on both verification and validation. DTs provide virtual representations of physical entities, processes, or systems, enabling real-time monitoring and predictive analytics throughout the drug development lifecycle [6]. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, DTs enhance operational efficiency, reduce costs, and improve product quality through sophisticated simulation capabilities.

The implementation of DTs faces significant verification and validation challenges, including data integration, model accuracy, and regulatory complexity [6]. Successful deployment requires rigorous verification of the digital twin's implementation and comprehensive validation against experimental data across the intended operating space. For coordination geometry research, digital twins of molecular systems could provide powerful tools for predicting binding behavior, but only if properly verified and validated.

Table 3: Performance Metrics in AI-Enhanced Drug Discovery

| Therapeutic Area | AI Method/Model | Key Validation Outcomes | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Conditional VAE | 3040 molecules generated; 15 dual-active; five entered IND-enabling studies; 30-fold selectivity gain | Preclinical (IND-enabling) |

| Oncology | ReLeaSE Framework | 50,000 scaffolds; 12 with IC50 ≤ 1 µM; three with >80% tumor inhibition; 85% had better CYP450 profiles | In vivo (xenograft models) |

| Lung Cancer | GAN + PubChem Screening | Predicted IC50 = 3.2–28.7 nM; >100-fold selectivity over wild-type receptors | In vitro + functional validation |

| Antiviral (COVID-19) | Deep Learning Generation | IC50 = 3.3 ± 0.003 µM (better than boceprevir); RMSD <2.0 Å over 500 ns | In vitro + molecular simulation |

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Benchmark Problems and Standardized Protocols

The development of standardized benchmark problems and protocols has significantly advanced verification and validation practices across computational domains. The Society for Experimental Mechanics organizes annual challenges, such as the SEM Round Robin Structure, that provide standardized benchmarks for evaluating substructuring methods and other computational techniques [7]. Similarly, the SV-COMP verification competition (2025 edition evaluated 62 verification tools and 18 witness validation tools) establishes rigorous protocols for assessing software verification capabilities [8].

These benchmark problems provide:

- Standardized evaluation metrics for comparing different computational approaches

- Reference solutions for verification activities

- Experimental datasets for validation exercises

- Uncertainty quantification frameworks for assessing result reliability

For coordination geometry research, developing similar community-accepted benchmark problems would facilitate more rigorous and comparable verification and validation activities across research groups.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for VVUQ

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in VVUQ Process |

|---|---|---|

| Verification Frameworks | SV-COMP benchmarks, SEM Round Robin Structure | Provide standardized test cases for verifying computational implementation and numerical methods |

| Validation Data Resources | ASME VVUQ Challenge Problems, validation experiment databases | Supply reference experimental data with quantified uncertainties for model validation |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tools | Statistical analysis packages, error estimation libraries | Quantify numerical, parameter, and model form uncertainties in computational predictions |

| Molecular Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS, CHARMM | Implement force fields and integration algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations (requires verification) |

| Coordination Geometry Analysis | PLIP, MetalPDB, coordination geometry calculators | Analyze and classify metal-ligand interactions in molecular structures |

| Experimental Characterization | X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, ITC | Provide experimental data for validating computational predictions of coordination geometry |

Standards and Community Practices

Established Standards for VVUQ

Professional societies have developed comprehensive standards to guide verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification practices. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) maintains several VVUQ standards, including [1]:

- VVUQ 1-2022: Standardized terminology for computational modeling and simulation

- V&V 10-2019: Verification and validation in computational solid mechanics

- V&V 20-2009: Verification and validation in computational fluid dynamics and heat transfer

- V&V 40-2018: Assessing credibility of computational modeling for medical devices

These standards provide structured frameworks for conducting and documenting verification and validation activities, facilitating consistent practices across different application domains and research groups.

Emerging Methodologies and Future Directions

The field of verification and validation continues to evolve with computational advancements. Key emerging trends include [2] [5]:

- Integration of AI/ML methods with traditional physics-based modeling

- Development of more sophisticated validation metrics that provide quantitative measures of agreement

- Advanced uncertainty quantification techniques for complex, multi-scale systems

- Standardized approaches for credibility assessment across different application domains

For coordination geometry research, these advancements promise more reliable prediction of molecular behavior, more efficient drug discovery pipelines, and enhanced ability to target previously "undruggable" proteins through improved understanding of molecular interactions.

The distinction between "solving equations right" (verification) and "solving the right equations" (validation) represents a fundamental principle in computational science with profound implications for coordination geometry research and pharmaceutical development. While verification ensures computational implementations correctly solve mathematical models, validation determines whether those models adequately represent physical reality. Both processes are essential for establishing computational credibility and making reliable predictions.

As computational methods continue to expand their role in scientific research and drug discovery, rigorous application of verification and validation principles becomes increasingly critical. The integration of these practices within a comprehensive VVUQ framework provides systematic guidance for assessing and improving computational model credibility. For researchers in coordination geometry and pharmaceutical development, adherence to these principles enhances research quality, accelerates discovery, and ultimately contributes to more effective therapeutic development.

Error and Uncertainty Quantification in Biological Systems Modeling

The predictive power of computational models in biology hinges on rigorously establishing their credibility. For researchers investigating intricate areas like coordination geometry in metalloproteins or enzyme active sites, quantifying error and uncertainty is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for generating reliable, actionable insights. The processes of verification—ensuring that "the equations are solved right"—and validation—determining that "the right equations are solved" are foundational to this effort [9]. As models grow in complexity to simulate stochastic biological behavior and multiscale phenomena, moving from deterministic, mechanistic descriptions to frameworks that explicitly handle uncertainty is a pivotal evolution in systems biology and systems medicine [10]. This guide objectively compares prevailing methodologies for error and uncertainty quantification, providing a structured analysis of their performance, experimental protocols, and application to the validation of computational models in coordination geometry research.

Core Concepts in Model V&V and Uncertainty

Understanding the distinct roles of verification and validation is crucial for any modeling workflow aimed at biological systems.

- Verification is the process of determining that a computational model implementation accurately represents the developer's conceptual description and mathematical solution. It answers the question: "Have I built the model correctly?" This involves checking for numerical errors, such as discretization error or software bugs, to ensure the model is solved as intended [9].

- Validation is the process of assessing a model's accuracy by comparing its computational predictions to experimental data derived from the physical system. It answers the question: "Have I built the correct model?" [9]. In coordination geometry studies, this could involve comparing a model's predicted metal-ligand bond lengths or angles to crystallographic data.

Error and uncertainty, while related, represent different concepts. Error is a recognizable deficiency in a model or data that is not excused by ignorance. Uncertainty is a potential deficiency that arises from a lack of knowledge about the system or its environment [9]. For instance, the inherent variation in measured bond angles across multiple crystal structures of the same protein constitutes an uncertainty, while a programming mistake in calculating these angles is an error.

Comparison of Uncertainty Quantification Methods

Several computational methods have been developed to quantify uncertainty in model predictions. The table below summarizes the core approaches relevant to biological modeling.

Table 1: Comparison of Uncertainty Quantification Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Application in Biology | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Model Checking (SMC) [11] | Combines simulation and model checking; verifies system properties against a finite number of stochastic simulations. | Analysis of biochemical reaction networks, cellular signaling pathways, and genetic circuits. | Scalable to large, complex models; provides probabilistic guarantees on properties. | Introduces a small amount of statistical uncertainty; tool performance is model-dependent. |

| Ensemble Methods [12] | Generates multiple models (e.g., random forests or neural network ensembles); uses prediction variance as uncertainty. | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models for chemical property prediction (e.g., Crippen logP). | Intuitive uncertainty estimate; readily implemented with common ML algorithms. | Computationally expensive; risk of correlated predictions within the ensemble. |

| Latent Space Distance Methods [12] | Measures the distance between a query data point and the training data within a model's internal (latent) representation. | Molecular property prediction with Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNNs). | Provides a measure of data adequacy; no need for multiple model instantiations. | Performance depends on the quality and structure of the latent space. |

| Evidential Regression [12] | Models a higher-order probability distribution over the model's likelihood function, learning uncertainty directly from data. | Prediction of molecular properties (e.g., ionization potential of transition metal complexes). | Direct learning of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty; strong theoretical foundation. | Complex implementation; can require specialized loss functions and architectures. |

The evaluation of these UQ methods themselves requires robust metrics. The error-based calibration plot is a superior validation technique that plots the predicted uncertainty (e.g., standard deviation, σ) against the observed Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). For a perfectly calibrated model, the data should align with the line RMSE = σ [12]. In contrast, metrics like Spearman's Rank Correlation between errors and uncertainties can be highly sensitive to test set design and distribution, potentially giving misleading results (e.g., values swinging from 0.05 to 0.65 on the same model) [12].

Table 2: Metrics for Evaluating Uncertainty Quantification Performance

| Metric | What It Measures | Interpretation | Pitfalls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Based Calibration [12] | Agreement between predicted uncertainty and observed RMSE. | A well-calibrated UQ method will have points lying on the line RMSE = σ. | Provides an overall picture but may mask range-specific miscalibration. | ||

| Spearman's Rank Correlation (ρ_{rank}) [12] | Ability of uncertainty estimates to rank-order the absolute errors. | Values closer to 1 indicate better ranking. | Highly sensitive to test set design; can produce unreliable scores. | ||

| Negative Log Likelihood (NLL) [12] | Joint probability of the data given the predicted mean and uncertainty. | Lower values indicate better performance. | Can be misleadingly improved by overestimating uncertainty, hiding poor agreement. | ||

| Miscalibration Area (A_{mis}) [12] | Area between the ideal | Z | distribution and the observed one. | Smaller values indicate better calibrated uncertainties. | Systematic over/under-estimation in different ranges can cancel out, hiding problems. |

Experimental Protocols for UQ Method Validation

Implementing a standardized protocol is essential for the objective comparison of UQ methods. The following workflow, detailed for chemical property prediction, can be adapted for various biological modeling contexts.

Diagram 1: UQ Method Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodology

The following steps expand on the workflow shown in Diagram 1.

Data Collection and Curation

- Source: Utilize a publicly available chemical data set with experimentally derived properties. Examples include Crippen logP [12] or vertical ionization potential (IP) for transition metal complexes [12] [13].

- Split: Partition the data into training, validation, and test sets. The test set should be designed to challenge the UQ methods, potentially including regions of chemical space not well-represented in the training data.

Model Training with UQ Methods

- Train a series of models using different UQ methods on the same training data.

- Ensemble (e.g., Random Forest): Train multiple decision trees; the uncertainty (standard deviation, σ) is derived from the variance of the individual tree predictions for a given molecule [12].

- Latent Space Distance (for GCNNs): Train a Graph Convolutional Neural Network. The uncertainty for a new molecule is calculated as its distance from the training set molecules within the model's latent space [12].

- Evidential Regression (for Neural Networks): Implement a neural network with a specific loss function that learns to output parameters (e.g., for a Normal Inverse-Gamma distribution) defining the evidence for a prediction, from which both the predicted value and its uncertainty are derived [12].

Prediction on Test Set

- Use the trained models to generate predictions for the held-out test set.

- For each molecule in the test set, record the predicted property value and its associated uncertainty estimate (e.g., the standard deviation σ).

Calculate Evaluation Metrics

- For each UQ method, compute the metrics outlined in Table 2.

- Error-Based Calibration: For binned ranges of predicted σ, calculate the corresponding RMSE. Plot RMSE vs. σ.

- Spearman's Rank Correlation: Calculate the correlation between the ranked list of absolute errors and the ranked list of predicted uncertainties.

- Negative Log Likelihood (NLL) and Miscalibration Area (A_mis): Compute these as described in the literature [12].

Performance Comparison and Analysis

- Compare the results across all UQ methods. The best-performing method is the one that demonstrates the most reliable error-based calibration and the most favorable profile across the other metrics, considering the specific application needs (e.g., prioritization of low-uncertainty predictions for screening).

Advanced Validation: Full-Field Techniques for Solid Mechanics

While the above protocols are suited for data-driven models, validation in computational biomechanics often involves comparing full-field experimental and simulated data, such as displacement or strain maps. Advanced shape descriptors like Zernike moments are critical for this task.

The improved calculation of Zernike moments using recursive computation and a polar pixel scheme allows for higher-order decomposition, processing of larger images, and reduced computation time. This enables more reliable validation of complex strain/displacement fields, even those with sharp discontinuities like cracks, which are of significant interest in mechanical analysis [14].

Table 3: Traditional vs. Improved Zernike Moment Computation

| Aspect | Traditional Computation | Improved Computation | Impact on Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Calculation | Direct evaluation, prone to numerical instabilities [14]. | Recursive calculation, numerically stable [14]. | Enables high-order decomposition for describing complex shapes. |

| Pixel Scheme | Rectangular/Cartesian pixels [14]. | Polar pixel scheme [14]. | Reduces geometric error, increases accuracy of moment integral. |

| Handling Discontinuities | Poor; requires pre-processing to remove holes/cracks [14]. | Good; can better approximate sharp changes [14]. | Allows validation in critical regions (e.g., crack propagation). |

| Maximum Usable Order | Limited (e.g., ~18) due to instability [14]. | Significantly higher (e.g., >50) [14]. | Finer details in displacement maps can be captured and compared. |

Diagram 2: Full-Field Validation with Zernike Moments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational tools and reagents essential for implementing the discussed UQ and validation methods.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Reagents

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SMC Predictor [11] | A software system that uses machine learning to automatically recommend the fastest Statistical Model Checking tool for a given biological model and property. | Reduces verification time and complexity for non-expert users analyzing stochastic biological models. |

| Zernike Moments Software [14] | A computational tool for calculating Zernike moments via recursive and polar pixel methods, enabling efficient compression and comparison of full-field data. | Validating computational solid mechanics models (e.g., FEA) against experimental full-field optical measurements (e.g., DIC). |

| Continuous Symmetry Operation Measure (CSOM) Tool [15] | Software that quantifies deviations from ideal symmetry in molecular structures, providing a continuous measure rather than a binary assignment. | Determining molecular structure, coordination geometry, and symmetry in transition metal complexes and lanthanide compounds. |

| PLASMA-Lab [11] | An extensible Statistical Model Checking platform that allows integration of custom simulators for stochastic systems. | Analysis of biochemical networks and systems biology models, offering flexibility for domain-specific simulators. |

| PRISM [11] | A widely-used probabilistic model checker supporting both numerical analysis and Statistical Model Checking via an internal simulator. | Verification of stochastic biological systems against formal specifications (e.g., temporal logic properties). |

| ZIF-8 Precursor [13] | A metal-organic framework (MOF) used as a precursor for synthesizing single-atom nanozymes (SAzymes) with controlled Zn–N4 coordination geometry. | Serves as an experimental system for studying the relationship between coordination geometry (tetrahedral, distorted tetrahedral) and catalytic activity. |

The rigorous quantification of error and uncertainty is the cornerstone of credible computational modeling in biology. For researchers in coordination geometry and beyond, this guide provides a comparative framework for selecting and validating appropriate UQ methodologies. The experimental data and protocols demonstrate that no single method is universally superior; the choice depends on the model type, the nature of the available data, and the specific question being asked. Ensemble and latent space methods offer practical UQ for data-driven models, while evidential regression presents a powerful, learning-based alternative. For complex spatial validation, advanced techniques like recursively computed Zernike moments set a new standard. By systematically implementing these V&V processes, scientists can bridge the critical gap between model prediction and experimental reality, ultimately accelerating discovery and drug development.

Coordination geometry, describing the three-dimensional spatial arrangement of atoms or ligands around a central metal ion, serves as a fundamental structural determinant in biological systems and drug design. In metalloprotein-drug interactions, the geometric properties of metal coordination complexes directly influence binding affinity, specificity, and therapeutic efficacy [16]. The field of coordination chemistry investigates compounds where a central metal atom or ion bonds to surrounding atoms or molecules through coordinate covalent bonds, governing the formation, structure, and properties of these complexes [16]. This geometric arrangement is not merely structural but functionally critical, as it dictates molecular recognition events, enzymatic activity, and signal transduction pathways central to disease mechanisms.

Understanding coordination geometry has become increasingly important with the rise of metal-based therapeutics and the recognition that many biological macromolecules rely on metal ions for structural integrity and catalytic function. Approximately one-third of all proteins require metal cofactors, and many drug classes—from platinum-based chemotherapeutics to metalloenzyme inhibitors—exert their effects through coordination chemistry principles [16]. Recent advances in computational structural biology have enabled researchers to predict and analyze these geometric relationships with unprecedented accuracy, facilitating the rational design of therapeutics targeting metalloproteins and utilizing metal-containing drug scaffolds.

Fundamental Concepts of Coordination Geometry in Biological Systems

Basic Coordination Principles and Common Geometries

Coordination complexes form through interactions between ligand s or p orbitals and metal d orbitals, creating defined geometric arrangements that can be systematically classified [16]. The most prevalent geometries in biological systems include:

- Octahedral Geometry: Six ligands arranged around the central metal ion, forming a symmetric structure common for first-row transition metal ions like Fe³⁺, Co³⁺, and Mn³⁺. This geometry appears in oxygen-carrying proteins and numerous metalloenzymes.

- Tetrahedral Geometry: Four ligands forming a tetrahedron around the central metal, frequently observed with Zn²⁺ and Cu²⁺ in catalytic sites.

- Square Planar Geometry: Four ligands in a single plane with the central metal, characteristic of Pt²⁺ and Pd²⁺ complexes, most famously in cisplatin and related anticancer agents.

- Trigonal Bipyramidal Geometry: Five ligands with three in equatorial positions and two axial, often found as transition states in enzymatic reactions.

The specific geometry adopted depends on electronic factors (crystal field stabilization energy, Jahn-Teller effects) and steric considerations (ligand size, chelate ring strain) [16]. These geometric preferences directly impact biological function, as the three-dimensional arrangement determines which substrates can be accommodated, what reaction mechanisms are feasible, and how the complex interacts with its protein environment.

Coordination Dynamics in Metalloproteins and Metalloenzymes

Natural metalloproteins provide the foundational models for understanding functional coordination geometry. These systems exhibit precisely tuned metal coordination environments that enable sophisticated functions:

- Zinc Finger Proteins: Utilize tetrahedral Zn²⁺ coordination (typically with two cysteine and two histidine ligands) to create structural domains that recognize specific DNA sequences, crucial for transcriptional regulation [16].

- Hemoglobin and Myoglobin: Feature iron in an octahedral geometry, with the heme plane providing four coplanar nitrogen ligands and a histidine residue as the fifth ligand, while the sixth position binds oxygen.

- Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase: Employs different geometries for each metal—tetrahedral for zinc and distorted square pyramidal for copper—to catalyze superoxide disproportionation.

- Vitamin B₁₂-Dependent Enzymes: Utilize cobalt in a unique corrin macrocycle with axial ligand coordination to mediate methyl transfer and rearrangement reactions.

These natural systems demonstrate how evolution has optimized coordination geometry for specific biochemical functions, providing design principles for synthetic metallodrugs and biomimetic catalysts [16]. The geometric arrangement influences not only substrate specificity and reaction pathway but also the redox potential and thermodynamic stability of metal centers in biological environments.

Computational Approaches for Coordination Geometry Analysis

Physical Validity Enforcement in Biomolecular Modeling

Recent advances in computational structural biology have highlighted the critical importance of enforcing physically valid coordination geometries in predictive models. Traditional deep learning-based structure predictors often generate all-atom structures violating basic steric feasibility, exhibiting steric clashes, distorted covalent geometry, and stereochemical errors that limit their biological utility [17]. These physical violations hinder expert assessment, undermine structure-based reasoning, and destabilize downstream computational analyses like molecular dynamics simulations.

To address these limitations, Gauss-Seidel projection methods have been developed to enforce physical validity as a strict constraint during both training and inference [17]. This approach maps provisional atom coordinates from diffusion models to the nearest physically valid configuration by solving a constrained optimization problem that respects molecular constraints including:

- Steric clash avoidance (preventing atomic overlap)

- Bond stereochemistry (maintaining proper bond lengths and angles)

- Tetrahedral atom chirality (preserving correct stereochemistry)

- Planarity of double bonds (maintaining conjugation systems)

- Internal ligand distance bounds (respecting molecular flexibility limits)

By explicitly handling validity constraints alongside generation, these methods enable the production of biomolecular complexes that are both physically valid and structurally accurate [17].

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Computational Methods for Biomolecular Interaction Prediction

| Method | Structural Accuracy (TM-score) | Physical Validity Guarantee | Sampling Steps | Wall-clock Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boltz-1-Steering [17] | 0.812 | No | 200 | Baseline (1x) |

| Boltz-2 [17] | 0.829 | No | 200 | 0.95x |

| Protenix [17] | 0.835 | No | 200 | 1.1x |

| Protenix-Mini [17] | 0.821 | No | 2 | 8.5x |

| Gauss-Seidel Projection [17] | 0.834 | Yes | 2 | 10x |

Table 2: Coordination Geometry Analysis in Heterogeneous Network Models

| Method | AUC | F1-Score | Feature Extraction Approach | Network Types Utilized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHGT-DTI [18] | 0.978 | 0.929 | Dual-view (neighborhood + meta-path) | DTI, drug-disease, protein-protein |

| GSRF-DTI [19] | 0.974 | N/R | Representation learning on large graph | Drug-target pair network |

| MHTAN-DTI [19] | 0.968 | N/R | Metapath-based hierarchical transformer | Heterogeneous network |

| CCL-DTI [19] | 0.971 | N/R | Contrastive loss in DTI prediction | Drug-target interaction network |

The integration of dual-view heterogeneous networks with GraphSAGE and Graph Transformer architectures (DHGT-DTI) represents a significant advancement, capturing both local neighborhood information and global meta-path perspectives to comprehensively model coordination environments in drug-target interactions [18]. This approach reconstructs not only drug-target interaction networks but also auxiliary networks (e.g., drug-disease, protein-protein) to improve prediction accuracy, achieving exceptional performance with an AUC of 0.978 on benchmark datasets [18].

Experimental Methodologies for Coordination Geometry Validation

Experimental Workflow for Coordination Geometry Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for validating coordination geometry in drug-target interactions:

Integrated Workflow for Coordination Geometry Validation

Key Experimental Protocols

Network Target Theory for Drug-Disease Interaction Prediction

Objective: Predict drug-disease interactions (DDIs) through network-based integration of coordination geometry principles and biological molecular networks [20].

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation:

- Collect drug-target interactions from DrugBank (16,508 entries categorized as activation, inhibition, or non-associative interactions)

- Extract disease information from MeSH descriptors (29,349 nodes, 39,784 edges)

- Obtain compound-disease interactions from Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (88,161 interactions, 7,940 drugs, 2,986 diseases) [20]

Network Propagation:

- Utilize Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network from STRING database (19,622 genes, 13.71 million interactions)

- Implement signed PPI network (Human Signaling Network v7) with 33,398 activation and 7,960 inhibition interactions

- Perform random walk analysis on biological networks to extract drug features [20]

Transfer Learning Model:

- Integrate deep learning with biological network data

- Address sample imbalance through negative sample selection

- Apply few-shot learning for drug combination prediction [20]

Validation:

- Performance metrics: AUC 0.9298, F1 score 0.6316 for DDI prediction

- Drug combination prediction: F1 score 0.7746 after fine-tuning

- Experimental validation via in vitro cytotoxicity assays confirming predicted synergistic combinations [20]

Cellular Target Engagement Validation

Objective: Confirm direct target engagement of coordination complex-based therapeutics in physiologically relevant environments.

Methodology:

- Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA):

- Treat intact cells with coordination complex therapeutics across concentration range

- Heat cells to denature proteins, with ligand-bound targets showing stabilized thermal profiles

- Detect stabilized targets via Western blot or mass spectrometry [21]

Experimental Parameters:

- Temperature range: 37-65°C in precise increments

- Compound exposure: 1-100 μM concentration, 1-24 hour timecourse

- Include vehicle controls and reference standards

Validation Metrics:

- Temperature-dependent stabilization (ΔTm)

- Dose-dependent stabilization (EC50)

- Specificity assessment against related metalloenzymes [21]

Applications:

- Quantitative measurement of drug-target engagement for DPP9 in rat tissue

- Confirmation of dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization ex vivo and in vivo

- Bridging biochemical potency with cellular efficacy for coordination-based therapeutics [21]

Research Reagent Solutions for Coordination Geometry Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Coordination Geometry Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Coordination Geometry Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | K₂PtCl₄, CuCl₂, ZnSO₄, FeCl₃, Ni(NO₃)₂ | Provide metal centers for coordination complex synthesis and metallodrug development [16] |

| Biological Ligands | Histidine, cysteine, glutamate, porphyrins, polypyridyl compounds | Mimic natural metal coordination environments and enable biomimetic design [16] |

| Computational Databases | DrugBank, STRING, MeSH, Comparative Toxicogenomics Database | Provide structural and interaction data for model training and validation [20] |

| Target Engagement Assays | CETSA kits, thermal shift dyes, proteomics reagents | Validate direct drug-target interactions in physiologically relevant environments [21] |

| Structural Biology Tools | Crystallization screens, cryo-EM reagents, NMR isotopes | Enable experimental determination of coordination geometries in complexes [17] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Cancer cell lines, primary cells, 3D organoids | Provide functional validation of coordination complex activity in biological systems [20] |

Biomedical Applications and Therapeutic Significance

Coordination Geometry in Established Metallodrug Classes

The therapeutic application of coordination geometry principles is exemplified by several established drug classes:

Platinum Anticancer Agents (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin): Feature square planar Pt(II) centers coordinated to amine ligands and leaving groups. The specific coordination geometry dictates DNA binding mode, cross-linking pattern, and ultimately the antitumor profile and toxicity spectrum [16]. Recent developments include Pt(IV) prodrugs with octahedral geometry that offer improved stability and activation profiles.

Metal-Based Antimicrobials: Silver (Ag⁺) and copper (Cu⁺/Cu²⁺) complexes utilize linear and tetrahedral coordination geometries respectively to disrupt bacterial enzyme function and membrane integrity. The geometry influences metal ion release kinetics and targeting specificity [22].

Gadolinium Contrast Agents: Employ octahedral Gd³⁺ coordination with macrocyclic ligands to optimize thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness, preventing toxic metal release while maintaining efficient water proton relaxation for MRI enhancement [16].

Zinc Metalloenzyme Inhibitors: Designed to mimic the tetrahedral transition state of zinc-dependent hydrolases and proteases, with geometry optimized to achieve high affinity binding while maintaining selectivity across metalloenzyme families.

Emerging Therapeutic Applications

Beyond traditional metallodrugs, coordination geometry principles are enabling new therapeutic modalities:

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Drug Delivery: Utilize precisely engineered coordination geometries to create porous structures with controlled drug loading and release profiles. The geometric arrangement of organic linkers and metal nodes determines pore size, surface functionality, and degradation kinetics [16].

Bioresponsive Coordination Polymers: Employ coordination geometries sensitive to biological stimuli (pH, enzyme activity, redox potential) for targeted drug release. For example, iron-containing polymers that disassemble in the reducing tumor microenvironment [16].

Artificial Metalloenzymes: Combine synthetic coordination complexes with protein scaffolds to create new catalytic functions not found in nature. The geometric control of the metal active site is crucial for catalytic efficiency and selectivity [16].

Theranostic Coordination Complexes: Integrate diagnostic and therapeutic functions through careful geometric design. For instance, porphyrin-based complexes with coordinated radioisotopes for simultaneous imaging and photodynamic therapy [22].

Coordination geometry remains a fundamental determinant of drug-target interactions, with implications spanning from basic molecular recognition to therapeutic efficacy. The integration of computational prediction with experimental validation has created powerful workflows for studying these relationships, enabling researchers to move from static structural descriptions to dynamic understanding of coordination geometry in biological contexts.

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas: (1) improved multi-scale modeling approaches that bridge quantum mechanical descriptions of metal-ligand bonds with macromolecular structural biology; (2) dynamic coordination systems that respond to biological signals for targeted drug release; (3) high-throughput experimental methods for characterizing coordination geometry in complex biological environments; and (4) standardized validation frameworks to ensure physical realism in computational predictions [17] [16].

As these methodologies mature, coordination geometry analysis will play an increasingly central role in rational drug design, particularly for the growing number of therapeutics targeting metalloproteins or utilizing metal-containing scaffolds. The continued convergence of computational prediction, experimental validation, and therapeutic design promises to unlock new opportunities for addressing challenging disease targets through coordination chemistry principles.

Establishing Credibility Frameworks for Regulatory Acceptance

The integration of computational models into scientific research and drug development represents a paradigm shift, offering unprecedented speed and capabilities. However, their adoption for critical decision-making, particularly in regulated environments, hinges on the establishment of robust credibility frameworks. These frameworks provide the structured evidence needed to assure researchers and regulators that model-based inferences are reliable for a specific context of use (COU) [23]. In coordination geometry research—which underpins the development of catalysts, magnetic materials, and metallodrugs—computational models that predict molecular structure, symmetry, and properties must be rigorously validated against experimental data to gain regulatory acceptance [15] [24]. This guide objectively compares the performance of different computational validation approaches, providing the experimental and methodological details necessary to assess their suitability for integration into a formal credibility framework.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Approaches

The following table summarizes the core performance metrics and validation data for prominent computational methods used in coordination geometry and drug development.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Primary Application | Key Performance Metrics | Supporting Experimental Validation | Regulatory Acceptance Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Symmetry Operation Measure (CSOM) [15] | Quantifying deviation from ideal symmetry; determining molecular structure & coordination geometry. | Quantifies symmetry deviation as a single, continuous value; allows automated symmetry assignment. | Validated against water clusters, organic molecules, transition metal complexes (e.g., Co, Cu), and lanthanide compounds [15] [24]. | Emerging standard in molecular informatics; foundational for structure-property relationships. |

| Cross-Layer Transcoder (CLT) / Attribution Graphs [25] | Mechanistic interpretation of complex AI models; revealing computational graphs. | Replaced model matches original model's output on ~50% of prompts; produces sparse, interpretable graphs [25]. | Validated via perturbation experiments on model features; case studies on factual recall and arithmetic [25]. | Framework (e.g., FDA's 7-step credibility assessment) exists; specific acceptance is case-by-case [23]. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling [26] [27] | Simulating drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) in virtual populations. | Predicts human pharmacokinetics; used for dose optimization, drug interaction risk assessment. | Extensive use in regulatory submissions for drug interaction and dosing claims; cited in FDA and EMA reviews [26] [27]. | Well-established in certain contexts (e.g., drug interactions); recognized in FDA and EMA guidances [23] [27]. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) [26] [27] | Simulating drug effects on disease systems; predicting efficacy and safety. | Number of QSP submissions to the FDA more than doubled from 2021 to 2024 [27]. | Applied to efficacy (>66% of cases), safety (liver toxicity, cytokine release), and dose optimization [27]. | Growing acceptance; used in regulatory decision-making; subject to credibility assessments [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol for Validating Symmetry Analysis with CSOM

The Continuous Symmetry Operation Measure (CSOM) software provides a yardstick for quantifying deviations from ideal symmetry in molecular structures [15].

1. Sample Preparation and Input Data Generation:

- Synthesis of Coordination Complexes: Synthesize target transition metal complexes (e.g., multinuclear cobalt complexes or µ-phenoxide bridged copper complexes) using established methods, such as condensation of Schiff base ligands with metal salts [24] [28].

- Crystallization and Data Collection: Grow single crystals via slow evaporation or other techniques. Characterize the complex using single-crystal X-ray diffraction to obtain precise 3D atomic coordinates [28].

2. Computational Analysis with CSOM:

- Input Preparation: Format the crystallographic data (a list of atomic coordinates in space) for the CSOM tool.

- Symmetry Quantification: The CSOM algorithm operates by:

- a. Applying a series of symmetry operations (e.g., rotations, reflections) to the molecular structure.

- b. Calculating the minimal distance the atoms must move to achieve the perfect, idealized symmetry.

- c. Outputting a continuous measure (CSOM value) where a value of 0 indicates perfect symmetry and higher values indicate greater distortion [15].

3. Validation and Correlation:

- Benchmarking: Validate the CSOM output against known, high-symmetry structures (e.g., C60 fullerene) and highly distorted complexes.

- Structure-Property Correlation: Correlate the calculated CSOM values with experimental properties, such as luminescence profiles or magnetic anisotropy, to establish the predictive power of the symmetry measure [15] [24].

Diagram 1: CSOM Validation Workflow

Protocol for Credibility Assessment of AI/ML Models in Regulatory Submissions

For AI/ML models used in drug development (e.g., predicting toxicity or optimizing clinical trials), regulatory agencies like the FDA recommend a rigorous risk-based credibility assessment framework [23].

1. Define Context of Use (COU):

- Clearly specify the role and scope of the AI model in addressing a specific regulatory question or decision. For example, "Use of an AI model to predict the risk of cytokine release syndrome for a monoclonal antibody using human 3D liver model data" [23] [29].

2. Model Development and Training:

- Data Integrity: Use high-quality, well-curated, and representative training data. Document all sources and preprocessing steps.

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate algorithm (e.g., deep learning, random forest). Justify the choice based on the problem and data type.

- Performance Evaluation: Assess model performance using relevant metrics (e.g., AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, recall) on a held-out test set.

3. Conduct Credibility Assessment (FDA's 7-Step Framework): This process evaluates the trustworthiness of the AI model for its specific COU [23].

- Define the Context of Use: (As in Step 1 above).

- Identify Model Requirements: Define quantitative performance benchmarks for acceptance.

- Assess Data Quality: Verify the relevance, completeness, and quality of the data used to develop and test the model.

- Verify Model Design: Ensure the model's architecture and training process are sound and well-documented.

- Evaluate Model Performance: Review the results from Step 2 against the pre-defined requirements.

- Assess External Consistency: Compare model predictions with existing scientific knowledge and independent data sets.

- Quantify Uncertainty: Characterize the uncertainty in the model's predictions.

4. Regulatory Submission and Lifecycle Management:

- Documentation: Compile a comprehensive report detailing all the above steps, the model's limitations, and its intended COU.

- Post-Market Monitoring: Implement a plan for monitoring model performance over time to detect and manage "model drift" [23].

Diagram 2: AI Model Credibility Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental validation of computational models relies on high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents used in the synthesis and analysis of coordination complexes discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Coordination Chemistry Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Schiff Base Ligands (e.g., H₂L from 2-[(2-hydroxymethylphenyl)iminomethyl]-6-methoxy-4-methylphenol) [24] | Chelating and bridging agent that coordinates to metal ions to form complex structures. | Template for assembling multinuclear complexes like [Co₇(L)₆] and [Co₄(L)₄] with diverse geometries [24]. |

| β-Diketone Co-Ligands (e.g., 4,4,4-trifluoro-1-(2-furyl)-1,3-butanedione) [28] | Secondary organic ligand that modifies the coordination environment and supramolecular packing. | Used in combination with 8-hydroxyquinoline to form µ-phenoxide bridged dinuclear Cu(II) complexes [28]. |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline [28] | Versatile ligand with pyridine and phenolate moieties; the phenolate oxygen can bridge metal centers. | Serves as a bridging ligand in dinuclear copper complexes, influencing the Cu₂O₂ rhombus core geometry [28]. |

| Single-Crystal X-ray Diffractometer [28] | Analytical instrument that determines the precise three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in a crystal. | Provides the experimental 3D atomic coordinates required for CSOM analysis and DFT calculations [15] [28]. |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [28] | Curated repository of experimentally determined small molecule and metal-organic crystal structures. | Used for comparative analysis to explore structural similarities and establish structure-property relationships [28]. |

The validation of computational models is a critical step for ensuring their reliability in biological research, particularly in the intricate field of coordination geometry. Validation is formally defined as "the process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of the intended uses of the model" [30]. Within this framework, model calibration—the process of adjusting model parameters to align computational predictions with experimental observations—serves as a foundational activity. Cardiac electrophysiology models provide an exemplary domain for studying advanced calibration protocols, as they must accurately simulate the complex, non-linear dynamics of the heart to be of scientific or clinical value. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional versus optimally-designed calibration protocols, drawing direct lessons from this mature field to inform computational modeling across the biological sciences.

Comparative Analysis of Calibration Approaches

The fidelity of a computational model is profoundly influenced by the quality of the experimental data used for its calibration. The table below compares the performance characteristics of traditional calibration protocols against those designed using Optimal Experimental Design (OED) principles, specifically in the context of calibrating cardiac action potential models [31].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Optimal Calibration Protocols for Cardiac Electrophysiology Models

| Performance Metric | Traditional Protocols | Optimal Design Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Uncertainty | Higher parameter uncertainty; describes 'average cell' dynamics [31] | Reduced parameter uncertainty; enables identification of cell-specific parameters [31] |

| Predictive Power | Limited generalizability beyond calibration conditions | Improved predictive power for system behavior [31] |

| Experiment Duration | Often longer, using established standard sequences [31] | Overall shorter duration, reducing experimental burden [31] |

| Protocol Design Basis | Common practices and historically used sequences in literature [31] | Mathematical optimization to maximize information gain for parameter estimation [31] |

| Primary Application | Generating models of general, average system behavior | Creating patient-specific digital twins and uncovering inter-cell variability [31] [32] |

Detailed Methodologies for Key Calibration Experiments

Model-Driven Optimal Experimental Design for Patch-Clamp Experiments

Objective: To automatically design voltage-clamp and current-clamp experimental protocols that optimally identify cell-specific maximum conductance values for major ion currents in cardiomyocyte models [31].

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Steps:

- System Definition: The researcher first defines a hypothesis of the cardiac cell's dynamics, typically encoded as a system of non-linear ordinary differential equations representing ion channel gating, concentrations, and currents [31].

- Optimization Algorithm: An OED algorithm is applied to this mathematical model. This algorithm computes the sequence of electrical stimuli (in voltage-clamp) or current injections (in current-clamp) that is theoretically expected to provide the maximum amount of information for estimating the model's parameters (e.g., maximum ion channel conductances) [31].

- Protocol Execution: The optimized experimental protocol is executed in a patch-clamp setup. Studies have demonstrated that these protocols are not only more informative but also of shorter overall duration compared to many traditionally used designs [31].

- Model Calibration: The experimental data collected from the optimal protocol is used to calibrate the parameters of the cardiac cell model. The reduced uncertainty in parameter estimation leads to a model with higher predictive power for simulating behaviors not directly tested during the calibration [31].

- Validation: The calibrated model's predictions are compared against independent experimental observations to assess its performance and the effectiveness of the calibration process, closing the loop of the model development cycle [30] [33].

Automated Workflow for ECG-Calibrated Volumetric Atrial Models

Objective: To create an efficient, end-to-end computational framework for generating patient-specific volumetric models of human atrial electrophysiology, calibrated to clinical electrocardiogram (ECG) data [32].

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Steps:

- Anatomical Model Generation: Volumetric biatrial models are automatically generated from medical images, incorporating detailed anatomical structures and realistic fiber architecture [32].

- Parameter Field Definition: A robust method is used to define spatially varying atrial parameter fields, which can be manipulated based on a universal atrial coordinate system [32].

- Pathway Parameterization: Inter-atrial conduction pathways, such as Bachmann's bundle and the coronary sinus, are modeled using a lightweight parametric approach, allowing for flexibility in representing patient-specific variations [32].

- Forward ECG Simulation: An efficient forward electrophysiology model is used to simulate the body surface ECG (specifically the P-wave) that results from the simulated electrical activity in the atria [32].

- Model Calibration: The simulated P-wave is compared to the P-wave from a clinical ECG of the patient (e.g., an atrial fibrillation patient in sinus rhythm). The model's parameters (e.g., conduction velocities in different tissue regions) are then automatically adjusted in an iterative process to minimize the difference between the simulated and clinical P-waves, thereby calibrating the digital twin to the individual patient [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The development and calibration of high-fidelity biological models rely on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources used in the featured cardiac electrophysiology studies, which serve as a template for analogous work in other biological systems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Model Calibration in Cardiac Electrophysiology

| Tool Name/Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Patch-Clamp Setup | Provides high-fidelity measurement of ionic currents (voltage-clamp) and action potentials (current-clamp) in isolated cells. | Generation of gold-standard experimental data for calibrating sub-cellular ionic current models [31]. |

| Optimal Experimental Design (OED) Algorithms | Automatically designs informative experimental protocols to minimize parameter uncertainty in model calibration. | Replacing traditional, less efficient voltage-clamp and current-clamp sequences for parameterizing cardiac cell models [31]. |

| Reaction-Eikonal & Reaction-Diffusion Models | Computationally efficient mathematical frameworks for simulating the propagation of electrical waves in cardiac tissue. | Simulating organ-level electrophysiology in volumetric atrial models for comparison with body surface ECGs [32]. |

| Universal Atrial Coordinates (UAC) | A reference frame system that enables unattended manipulation of spatial and physical parameters across different patient anatomies. | Mapping parameter fields (e.g., fibrosis, ion channel density) onto patient-specific atrial geometries in digital twin generation [32]. |

| Bayesian Validation Metrics | A probabilistic framework for quantifying the confidence in model predictions by comparing model output with stochastic experimental data. | Providing a rigorous, quantitative validation metric that incorporates various sources of error and uncertainty [33]. |

| Clinical Imaging (MRI) | Provides the precise 3D anatomical geometry required for constructing patient-specific volumetric models. | The foundational first step in creating anatomically accurate atrial models for digital twin applications [32]. |

The quantitative comparison and detailed methodologies presented demonstrate a clear performance advantage for model-driven optimal calibration protocols over traditional approaches. The key takeaways are that optimally designed experiments are not only more efficient but also yield models with lower parameter uncertainty and higher predictive power, which is essential for progressing from models of "average" biology to those capable of capturing individual variability, such as digital twins [31] [32]. The rigorous, iterative workflow of hypothesis definition, optimal design, calibration, and Bayesian validation [33] provides a robust template that can be adapted beyond cardiac electrophysiology to the broader challenge of validating computational models in coordination geometry research. The ultimate lesson is that investment in sophisticated calibration protocol design is not a secondary concern but a primary determinant of model utility and credibility.

Computational Approaches and Experimental Integration for Geometry Validation

Combinatorial Algorithms for Geometric Analysis in Sparse Data Environments

Validating computational models for coordination geometry is a cornerstone of reliable research in fields ranging from structural geology to pharmaceutical development. Sparse data environments, characterized by limited and often imprecise measurements, present a significant challenge for such validation efforts. In these contexts, combinatorial algorithms have emerged as powerful tools for geometric analysis, enabling researchers to systematically explore complex solution spaces and infer robust structural models from limited evidence. This guide compares the performance of prominent combinatorial algorithmic approaches used to analyze geometric properties and relationships when data is scarce. By objectively evaluating these methods based on key quantitative metrics and experimental outcomes, we provide researchers with a clear framework for selecting appropriate tools for validating their own computational models of coordination geometry.

Performance Comparison of Combinatorial Algorithms

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of three combinatorial algorithmic approaches for geometric analysis in sparse data environments.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Combinatorial Algorithms for Geometric Analysis

| Algorithm Category | Theoretical Foundation | Query Complexity | Computational Efficiency | Key Applications in Sparse Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison Oracle Optimization | Inference dimension framework, Global Subspace Learning [34] | O(n²log²n) for general Boolean optimization; O(nBlog(nB)) for integer weights [34] | Runtime can be exponential for NP-hard problems; polynomial for specific problems (min-cut, spanning trees) [34] | Molecular structure optimization, drug discovery decision-making [34] |

| Combinatorial Triangulation | Formal mathematical propositions, directional statistics [35] | Generates all possible 3-element subsets from n points: O(n³) combinations [35] | Computational cost increases rapidly with data size (governed by Stirling numbers) [35] | Fault geometry interpretation in sparse borehole data, analyzing geometric effects in displaced horizons [35] |

| Neural Combinatorial Optimization | Carathéodory's theorem, convex geometry, polytope decomposition [36] | Varies by architecture; demonstrates strong scaling to instances with hundreds of thousands of nodes [36] | Efficient training and inference via differentiable framework; outperforms neural baselines on large instances [36] | Cardinality-constrained optimization, independent sets in graphs, matroid-constrained problems [36] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comparison Oracle Optimization Framework

The experimental protocol for evaluating comparison oracle optimization involves several methodical steps. First, researchers define the ground set U of n elements and the family of feasible subsets F ⊆ 2U. The comparison oracle is implemented to respond to queries comparing any two feasible sets S, T ∈ F, revealing whether w(S) < w(T), w(S) = w(T), or w(S) > w(T) for an unknown weight function w. Query complexity is measured by counting the number of comparisons required to identify the optimal solution S* = argminS∈F w(S). For problems with integer weights bounded by B, the Global Subspace Learning framework is applied to sort all feasible sets by objective value using O(nBlog(nB)) queries. Validation involves applying the approach to fundamental combinatorial problems including minimum cuts in graphs, minimum weight spanning trees, bipartite matching, and shortest path problems to verify theoretical query complexity bounds [34].

Combinatorial Triangulation for Geometric Analysis

The combinatorial triangulation approach follows a rigorous protocol for analyzing geometric structures from sparse data. Researchers first collect point data from geological surfaces (e.g., from boreholes or surface observations). The combinatorial algorithm then generates all possible three-element subsets (triangles) from the n-element point set. For each triangle, the normal vector is calculated, and its geometric orientation (dip direction and dip angle) is determined. In scenarios with elevation uncertainties, statistical analysis is performed on the directional data. The Cartesian coordinates of normal vectors are averaged, and the resultant vector is converted to dip direction and dip angle pairs. The mean direction θ̄ is calculated using specialized circular statistics formulas, accounting for the alignment of coordinate systems with geographical directions. Validation includes comparing results against known geological structures and analyzing the percentage of triangles exhibiting expected versus counterintuitive geometric behaviors [35].

Neural Combinatorial Optimization with Constraints

The experimental methodology for neural combinatorial optimization with geometric constraints implements a differentiable framework that incorporates discrete constraints directly into the learning process. Researchers first formulate the combinatorial optimization problem with discrete constraints and represent feasible solutions as corners of a convex polytope. A neural network is trained to map input instances to continuous vectors in the convex hull of feasible solutions. An iterative decomposition algorithm based on Carathéodory's theorem is then applied to express these continuous vectors as sparse convex combinations of feasible solutions (polytope corners). During training, the expected value of the discrete objective under this distribution is minimized using standard automatic differentiation. At inference time, the same decomposition algorithm generates candidate feasible solutions. Performance validation involves comparing results against traditional combinatorial algorithms and other neural baselines on standard benchmark problems with cardinality constraints and graph-based constraints [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential computational tools and methodologies used in combinatorial algorithms for geometric analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Combinatorial Geometric Analysis

| Research Reagent | Type/Function | Specific Application in Geometric Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison Oracle | Computational query model | Reveals relative preferences between feasible solutions without requiring precise numerical values [34] |

| Combinatorial Triangulation Algorithm | Geometric analysis tool | Generates all possible triangle configurations from sparse point data to analyze fault orientations [35] |

| Carathéodory Decomposition | Geometric algorithm | Expresses points in polytope interiors as sparse convex combinations of feasible solutions [36] |

| Linear Optimization Oracle | Algorithmic component | Enables efficient optimization over feasible set polytopes in neural combinatorial optimization [36] |

| Directional Statistics Framework | Analytical methodology | Analyzes 3D directional data from normal vectors of triangles; calculates mean dip directions [35] |

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Combinatorial triangulation workflow for sparse data analysis.

Figure 2: Neural combinatorial optimization with constraint handling.

This comparison guide has objectively evaluated three prominent combinatorial algorithmic approaches for geometric analysis in sparse data environments. Each method demonstrates distinct strengths: comparison oracle optimization provides robust theoretical query complexity bounds; combinatorial triangulation offers interpretable geometric insights from limited point data; and neural combinatorial optimization delivers scalability to large problem instances through differentiable constraint handling. The experimental protocols and performance metrics detailed in this guide provide researchers with a foundation for selecting and implementing appropriate combinatorial algorithms for their specific geometric analysis challenges. As computational models for coordination geometry continue to evolve in complexity, these combinatorial approaches will play an increasingly vital role in validating structural hypotheses against sparse empirical evidence, particularly in pharmaceutical development and structural geology applications where data collection remains challenging and expensive.

The validation of computational models in coordination geometry research demands experimental techniques that provide high-fidelity, full-field surface data. Digital Image Correlation (DIC) and Thermoelastic Stress Analysis (TSA) have emerged as two powerful, non-contact optical methods that fulfill this requirement. While DIC measures surface displacements and strains by tracking random speckle patterns, TSA derives stress fields from the thermodynamic temperature changes under cyclic loading. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, capabilities, and limitations, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols. Furthermore, it explores the emerging paradigm of full-field data fusion, which synergistically combines these techniques with finite element analysis (FEA) to create a comprehensive framework for high-confidence model validation [37] [38].

In experimental mechanics, the transition from point-based to full-field measurement has revolutionized the validation of computational models. For research involving complex coordination geometries, such as those found in composite material joints or biological structures, understanding the complete surface strain and stress state is critical. DIC and TSA are two complementary techniques that provide this spatial richness.

Digital Image Correlation is a kinematic measurement technique that uses digital images to track the motion of a speckle pattern applied to a specimen's surface. By comparing images in reference and deformed states, it computes full-field displacements and strains [39] [40]. Its fundamental principle is based on photogrammetry and digital image processing, and it can be implemented in either 2D or 3D (stereo) configurations [41].

Thermoelastic Stress Analysis is based on the thermoelastic effect, where a material undergoes a small, reversible temperature change when subjected to adiabatic elastic deformation. Under cyclic loading, an infrared camera detects these temperature variations, which are proportional to the change in the sum of principal stresses [42] [37]. For orthotropic composite materials, the relationship is expressed as:

[\Delta T=-\frac{{T}{0}}{\rho {C}{p}}\left({\alpha }{1}\Delta {\sigma }{1}+{\alpha }{2}\Delta {\sigma }{2}\right)]

where ({T}{0}) is the absolute temperature, (\rho) is density, ({C}{p}) is specific heat, (\alpha) is the coefficient of thermal expansion, and (\sigma) is stress [37].

Technical Comparison of DIC and TSA

The following tables summarize the fundamental characteristics, performance parameters, and application suitability of DIC and TSA for experimental validation in coordination geometry research.

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics and measurement principles of DIC and TSA.

| Feature | Digital Image Correlation (DIC) | Thermoelastic Stress Analysis (TSA) |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Surface displacements and strains [39] [40] | Sum of principal stresses (stress invariant) [42] [37] |

| Physical Principle | Kinematics (image correlation and tracking) [41] | Thermodynamics (thermoelastic effect) [37] |

| Required Surface Preparation | Stochastic speckle pattern [40] | Coating with high, uniform emissivity (e.g., matt black paint) [37] |