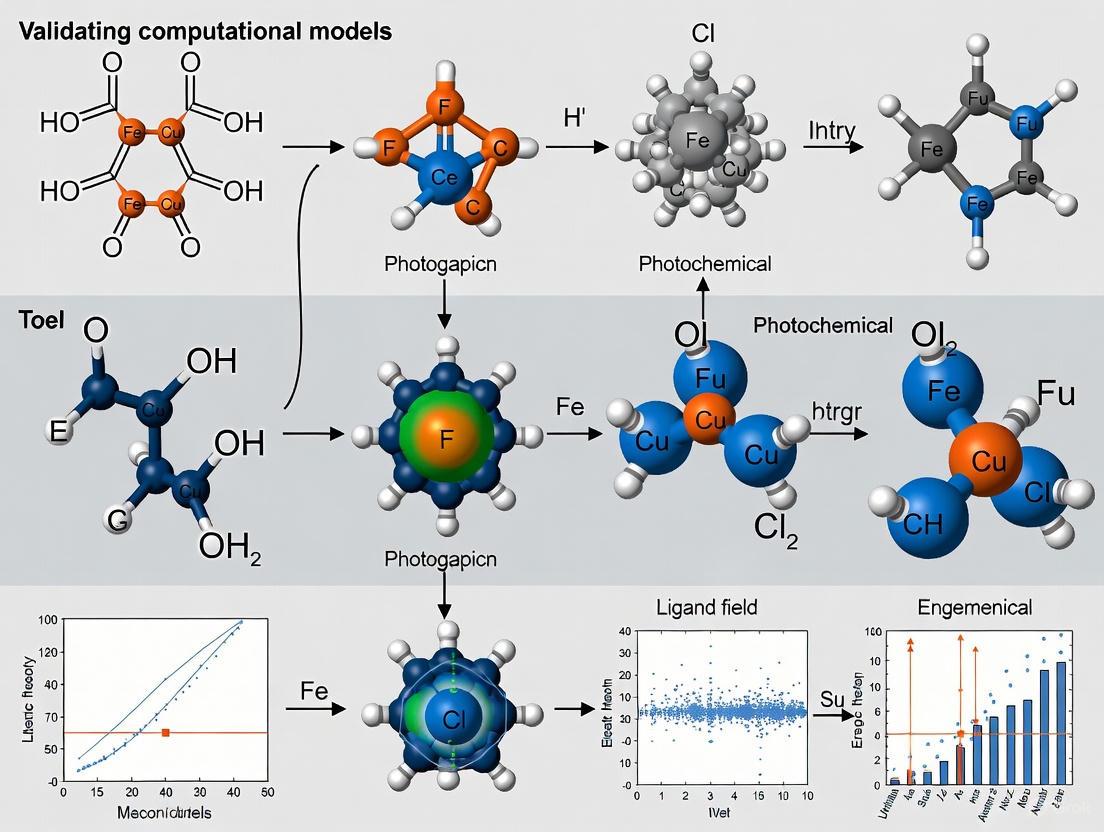

Validating Computational Models for Inorganic Photochemical Mechanisms: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of computational models used to study inorganic photochemical mechanisms, a field critical for advancements in photodynamic therapy, drug design, and diagnostic...

Validating Computational Models for Inorganic Photochemical Mechanisms: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of computational models used to study inorganic photochemical mechanisms, a field critical for advancements in photodynamic therapy, drug design, and diagnostic imaging. It explores the foundational quantum mechanical principles underpinning these models, examines cutting-edge methodological approaches and their biomedical applications, and addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies. A strong emphasis is placed on rigorous benchmarking against experimental data and the comparative analysis of different computational tools. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices to enhance the reliability and predictive power of computational simulations in photochemistry.

The Quantum Mechanical Bedrock: Understanding the Principles of Photochemical Simulations

In the study of photochemical mechanisms, potential energy surfaces (PESs) provide the fundamental topography upon which molecular dynamics unfold. These multidimensional surfaces represent the energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates, creating a landscape that guides the pathways and outcomes of chemical reactions. Within this landscape, conical intersections (CoIns)—degeneracy points where two potential energy surfaces intersect—have evolved from theoretical curiosities to recognized critical features governing ultrafast photochemical processes [1]. Analogous to transition states in thermal chemistry, conical intersections serve as transient funnels that enable electronically excited molecules to return efficiently to their ground state [1]. For researchers investigating inorganic photochemical mechanisms, understanding the relationship between potential energy surfaces and conical intersections is paramount, as these concepts form the theoretical foundation for interpreting light-induced molecular behavior across diverse chemical systems.

The significance of conical intersections extends across numerous domains of chemistry and biology. They play pivotal roles in photostability mechanisms that protect DNA bases from UV damage, enable the primary events in vision through retinal photoisomerization, and facilitate fundamental pericyclic reactions in organic synthesis [1]. As research advances, the ability to accurately map these topological features and model the nonadiabatic dynamics they govern has become increasingly crucial for both fundamental understanding and practical applications in photochemistry, materials science, and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Potential Energy Surfaces and Their Topographies

The Born-Oppenheimer Framework and Its Limitations

The theoretical description of molecular systems typically begins with the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates electronic and nuclear motion based on their significant mass difference [2]. This separation allows researchers to compute the electronic energy for fixed nuclear configurations, generating potential energy surfaces that govern nuclear motion. The complete molecular Hamiltonian is expressed as:

[ H{\text{mol}} = -\sum{n}\frac{\Delta{n}}{2M{n}} - \sum{i}\frac{\Delta{i}}{2} - \sum{i,m}\frac{Z{m}}{|\mathbf{R}{m}-\mathbf{r}{i}|} + \sum{m,n>m}\frac{Z{m}Z{n}}{|\mathbf{R}{n}-\mathbf{R}{m}|} + \sum{i,j>i}\frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}{i}-\mathbf{r}{j}|} ]

Under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, this simplifies to the electronic Hamiltonian:

[ H{\text{elect}} = -\sum{i}\frac{\Delta{i}}{2} - \sum{i,m}\frac{Z{m}}{|\mathbf{R}{m}-\mathbf{r}{i}|} + \sum{i,j>i}\frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}{i}-\mathbf{r}{j}|} ]

While this approximation provides a foundational framework for quantum chemistry, it breaks down in regions where electronic states become nearly degenerate—precisely at conical intersections—requiring more sophisticated treatments that incorporate nonadiabatic couplings between electronic and nuclear motions [3].

Conical Intersections: Topography and Classification

Conical intersections represent multidimensional seams where two adiabatic potential energy surfaces become degenerate. Their topography can be characterized by two key vectors: the gradient difference vector and the nonadiabatic coupling vector. These directions define the branching plane within which the degeneracy is lifted, while in the remaining dimensions, the surfaces remain degenerate, forming an intersection space [1].

Two primary topographical classes of conical intersections have been identified:

- Peaked Conical Intersections: Feature a double-cone structure where both surfaces are repulsive, typically leading to ultrafast decay without formation of excited-state intermediates [1].

- Sloped Conical Intersections: Characterized by one attractive and one repulsive surface, often permitting some excited-state relaxation before decay [1].

The distinction between these topographies has profound implications for reaction dynamics and outcomes. Peaked intersections typically facilitate faster decay processes, while sloped intersections may allow for more extensive nuclear motion on the excited-state surface before decay.

Methodological Comparison: Computational Approaches for Mapping Potential Energy Surfaces and Conical Intersections

Electronic Structure Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods for Potential Energy Surface Mapping

| Method | Theoretical Approach | Strengths | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Reference Configuration Interaction (MRCI) | Electron correlation treatment using multi-reference wavefunctions | High accuracy for degenerate states; Suitable for conical intersection regions | Computational expensive; Scaling limitations | BH2 PES construction [4]; He + H2 system [5] |

| Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) | Optimizes orbitals and CI coefficients for selected active space | Proper description of near-degeneracy; Balanced treatment of states | Active space selection sensitive; Lacks dynamic correlation | BH2 PES with SA-CASSCF [4]; Pyrazine dynamics [6] |

| Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQE/VQD) | Hybrid quantum-classical approach for eigenvalue problems | Potential quantum advantage; Access to exact wavefunction | Hardware limitations; Ansatz dependence | Methanimine and water CoIns [2] |

| Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) | Matrix product state representation for correlation | Handles strong electron correlation; Large active spaces | Primarily 1D systems; Implementation complexity | Alternative for strong correlation [2] |

The selection of an appropriate electronic structure method represents a critical decision point in mapping potential energy surfaces and locating conical intersections. Traditional multi-reference methods like MRCI and CASSCF have established themselves as benchmarks for accuracy in treating electron correlation effects essential for properly describing degenerate regions [4] [5]. For the BH2 system, for instance, researchers employed SA-CASSCF calculations including three electronic states with equal weights, followed by MRCI calculations to capture dynamic correlation effects [4]. Similarly, for the He + H2 system, high-level MCSCF/MRCI calculations with large basis sets (aug-cc-pV5Z) were necessary to accurately map the adiabatic potential energy points [5].

Emerging quantum computing approaches offer potential pathways for overcoming the exponential scaling limitations of classical methods. Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and its excited-state extension Variational Quantum Deflation (VQD) have demonstrated capability in locating conical intersections in small molecules like methanimine and water [2]. These methods leverage parameterized quantum circuits to prepare trial wavefunctions, with classical optimization loops to minimize energy expectations. While currently limited to small systems by quantum hardware constraints, they represent a promising frontier for future computational studies of complex photochemical systems.

Dynamics Simulation Methods

Table 2: Nonadiabatic Dynamics Methods for Conical Intersection-Mediated Processes

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Strengths | Limitations | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Dependent Wave Packet (TDWP) | Quantum nuclear propagation on coupled surfaces | Full quantum dynamics; Accurate treatment of interference | Computational cost limits system size | B(2p2P) + H2 reaction dynamics [4] |

| Surface Hopping | Classical trajectories with stochastic hops | Applicable to large systems; Inclusion of environmental effects | Lacks quantum coherence; Internal consistency issues | Pyrazine in solution [6] |

| Multi-Configurational Time-Dependent Hartree (MCTDH) | Variational quantum dynamics with time-dependent basis | High efficiency for medium systems; Maintains quantum effects | Implementation complexity; Basis set limitations | Community benchmark studies [7] |

| Ehrenfest Dynamics | Mean-field trajectory on averaged surfaces | Continuous electronic evolution; Computational efficiency | Unphysical state mixing in decohered regions | Method development benchmarks [7] |

Dynamics simulations methods enable researchers to move beyond static potential energy surfaces to model the actual time evolution of molecular systems through conical intersections. Time-dependent wave packet methods provide the most rigorous quantum dynamical treatment, solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation for nuclear motion on coupled electronic surfaces [4]. For the B(2p2P) + H2 reaction, TDWP calculations revealed detailed reaction probabilities, integral cross sections, and differential cross sections, showing that a "complex-forming" mechanism dominates at low collision energies while forward abstraction becomes dominant at high energies [4].

For larger systems, mixed quantum-classical methods like surface hopping offer a practical compromise, though they must carefully address challenges such as quantum decoherence and internal consistency [7]. Recent studies of pyrazine dynamics in aqueous solution employed surface hopping simulations incorporating solvation effects, revealing complete suppression of electronic dynamics within 40 femtoseconds—a finding with significant implications for photochemical processes in biological environments [6].

Experimental Validation: Measuring Conical Intersection Dynamics

Ultrafast Structural Techniques

Cutting-edge experimental methods have emerged that can directly resolve molecular dynamics through conical intersections with unprecedented spatiotemporal resolution. Mega-electron-volt ultrafast electron diffraction (MeV-UED) combined with super-resolution inversion algorithms has enabled visualization of nuclear and electronic motions at conical intersections with sub-angstrom resolution, surpassing the traditional diffraction limit [8].

In a landmark study of the ring-opening reaction of 1,3-cyclohexadiene, researchers achieved an instrument response function of approximately 80 fs (FWHM), allowing them to track the wave packet traversal between two conical intersections with approximately 30-fs resolution [8]. The experimental methodology involved:

- UV Pump Pulse: 273 nm, 60 fs FWHM to excite molecules to the 1B state

- Electron Probe: 3 MeV ultrashort electron beam to probe reaction dynamics

- Detection: Time-resolved diffraction patterns recorded at different delay times

- Super-Resolution Processing: Model-free deconvolution algorithm to achieve atomic-scale resolution beyond the diffraction limit

This approach resolved a C-C bond length difference of less than 0.4 Å near the conical intersections and directly observed the nuclear wave packet traversal between them [8]. The combination of enhanced temporal resolution and super-resolution data processing represents a transformative advancement in validating computational predictions of conical intersection dynamics.

X-Ray Spectroscopic Techniques

Time-resolved X-ray spectroscopy provides complementary information about electronic structure evolution during conical intersection passage. Soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy at the carbon and nitrogen K-edges has been used to track electronic dynamics in both isolated and solvated molecules [6].

In studies of pyrazine relaxation, researchers employed:

- Pump Pulse: 30 fs pulse centered at 266 nm

- X-Ray Probe: Soft X-ray supercontinuum from high-harmonic generation beyond 450 eV

- Detection Scheme: Transient absorption measurements with 10 fs steps

- Sample Environment: Comparative studies in gas phase and aqueous solution

This approach revealed that conical intersections can create electronic dynamics not directly excited by the pump pulse, manifested as a cyclic rearrangement of electronic structure around the aromatic ring [6]. Furthermore, comparative measurements in aqueous solution demonstrated complete suppression of these electronic dynamics within 40 fs, highlighting the critical role of solvation in dephasing coherent electronic processes [6].

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Resources for Conical Intersection Research

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOLPRO | Electronic Structure Package | High-level ab initio calculations (MRCI, CASSCF) | He + H2 potential energy surfaces [5] |

| Permutation Invariant Polynomial Neural Network (PIP-NN) | Potential Energy Surface Fitting | Constructing global PES from ab initio data | BH2 global potential energy surface [4] |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Quantum Algorithm | Ground and excited state energy computation | Methanimine and water conical intersections [2] |

| B-spline Fitting | Numerical Method | Smooth potential energy surface interpolation | He + H2 adiabatic PES construction [5] |

| Time-Dependent Wave Packet (TDWP) | Dynamics Method | Quantum nuclear propagation on coupled surfaces | B(2p2P) + H2 reaction probabilities [4] |

The computational investigation of conical intersections requires specialized software tools and methodologies. Electronic structure packages like MOLPRO provide implementations of high-level multi-reference methods essential for accurately describing degenerate regions [5]. For the He + H2 system, researchers utilized MOLPRO's MCSCF/MRCI capabilities with large basis sets (aug-cc-pV5Z) to compute 34,848 adiabatic potential energy points, which were subsequently fitted using B-spline methods to generate smooth potential energy surfaces [5].

Machine learning approaches have emerged as powerful tools for constructing global potential energy surfaces from discrete ab initio calculations. The Permutation Invariant Polynomial Neural Network (PIP-NN) method was successfully applied to the BH2 system, creating a global potential energy surface based on 15,866 ab initio points that accurately reproduced experimental data and exhibited detailed topographic features [4]. This approach maintains the permutational invariance of identical nuclei while providing a continuous representation suitable for high-dimensional quantum dynamics calculations.

Conceptual Framework: Relationship Between Potential Energy Surfaces and Conical Intersections

Diagram: The interconnected relationship between potential energy surfaces, conical intersections, and experimental validation in computational photochemistry.

The relationship between potential energy surfaces and conical intersections forms a conceptual cycle central to modern photochemical research. This framework begins with the computation of potential energy surfaces under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which provides the initial topographic map of electronic states [2]. In regions where these surfaces approach degeneracy, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down due to significant nonadiabatic coupling between electronic and nuclear motions [3]. This breakdown leads to the identification and characterization of conical intersections, which facilitate ultrafast dynamics through nonradiative transitions between electronic states [1]. These dynamical processes can be probed through experimental validation using advanced spectroscopic and diffraction techniques, which in turn refine the computational models of potential energy surfaces, completing the cycle of investigation [8] [6].

This conceptual framework highlights the iterative nature of research in this field, where computational predictions and experimental observations continuously inform and refine each other. For inorganic photochemical mechanisms specifically, this approach enables researchers to move beyond static representations of molecular structure to develop dynamic models that capture the essence of photochemical reactivity.

The investigation of potential energy surfaces and conical intersections represents a rapidly advancing frontier where theoretical methods and experimental techniques are converging to provide unprecedented insight into photochemical mechanisms. For researchers focused on inorganic systems, the methodological landscape offers multiple pathways for exploring nonadiabatic dynamics, each with characteristic strengths and limitations. High-level electronic structure methods like MRCI and CASSCF provide benchmark accuracy for potential energy surface mapping, while time-dependent dynamics methods capture the nuclear motion through conical intersection regions. Emerging quantum algorithms offer promising directions for overcoming current computational bottlenecks.

The integration of advanced experimental techniques—particularly ultrafast electron diffraction and X-ray spectroscopy—with computational models has created powerful validation frameworks that bridge the gap between theoretical prediction and observational confirmation. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to deepen our understanding of photochemical processes in increasingly complex inorganic systems, with significant implications for photocatalysis, materials design, and pharmaceutical development. The ongoing refinement of this integrated computational and experimental toolkit will undoubtedly uncover new principles of photochemical reactivity rooted in the fundamental topography of potential energy surfaces and their intersections.

Computational chemistry provides essential tools for investigating inorganic photochemical mechanisms, enabling researchers to predict reaction pathways, spectroscopic properties, and excited-state dynamics that are often difficult to characterize experimentally. The validation of these computational models requires careful assessment of their accuracy, efficiency, and applicability across diverse chemical systems. This guide objectively compares three prominent approaches—Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT), Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) methods, and emerging machine learning (ML)-enhanced approaches—for studying inorganic and transition metal systems. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations for modeling photochemical processes in transition metal complexes, nanoparticles, and other inorganic systems, with selection criteria depending on the specific research objectives, system size, and desired accuracy.

Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT)

TD-DFT extends standard density functional theory to model excited electronic states by computing the linear response of the electron density to a time-dependent perturbation [9]. The widespread adoption of TD-DFT stems from its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy for medium to large systems. Two primary implementations exist: Linear Response TD-DFT (LR-TDDFT) solves Casida's equations to obtain excitation energies and transition properties, while Real-Time TD-DFT (RT-TDDFT) propagates the time-dependent Kohn-Sham equations numerically to simulate electron dynamics [9]. For inorganic photochemistry, TD-DFT can be combined with embedding methods like QM/MM or polarizable continuum models (PCMs) to simulate environmental effects in solvents, proteins, or near surfaces [9].

Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF)

CASSCF is a multi-reference wavefunction-based method that provides a more sophisticated treatment of electron correlation effects, which is crucial for systems with significant multi-configurational character [10]. The method divides molecular orbitals into inactive, active, and virtual spaces, with a full configuration interaction treatment within the active space. CASSCF is particularly valuable for studying photochemical reaction pathways, conical intersections, and transition metal complexes with strong electron correlation effects [10]. The method is often combined with perturbation theory (e.g., CASPT2) to improve energy estimates, as demonstrated in studies of excited states in transition metal complexes like HRe(CO)₅ [10].

ML-Enhanced Computational Approaches

Machine learning-enhanced quantum chemistry represents a paradigm shift in computational modeling, leveraging pattern recognition to accelerate calculations and improve accuracy. These approaches include ML potential energy surfaces that bypass explicit electronic structure calculations, property prediction models that learn from high-quality reference data, and adaptive sampling algorithms that guide computational resources toward chemically relevant regions of configuration space. While less explicitly covered in the search results, ML methods address key limitations of traditional approaches, particularly for systems where TD-DFT struggles with charge-transfer states or where CASSCF becomes computationally prohibitive [9].

Table 1: Theoretical Foundations and Typical Applications

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Strength Domains | System Size Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| TD-DFT | Linear response theory / Time-dependent electron density | UV-Vis spectra, singlet states, charge-transfer excitations (with range-separated functionals) | Hundreds of atoms [9] |

| CASSCF | Multi-configurational wavefunction theory | Multi-reference systems, bond breaking, excited-state pathways, conical intersections | Tens of atoms (active space dependent) [10] |

| ML-Enhanced | Data-driven models trained on quantum chemistry data | High-throughput screening, dynamics, systems where traditional methods fail | Thousands of atoms (depends on training data) |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Data

Accuracy Assessment Across Chemical Systems

Rigorous benchmarking against experimental data and high-level theoretical references provides critical insights into the performance characteristics of each computational method. For TD-DFT, functional selection dramatically impacts accuracy, with global hybrid functionals like B3LYP and PBE0 generally providing reasonable results for valence excitations, while range-separated functionals like CAM-B3LYP are essential for charge-transfer states [9] [11]. In assessments of transition metal complexes, TD-DFT performs satisfactorily for d², d⁴, and low-spin d⁶ systems but struggles when excitations depend primarily on ligand field splitting or involve double excitations [10].

CASSCF and its perturbation-corrected variant CASPT2 demonstrate superior performance for challenging multi-reference systems, as evidenced by studies of HRe(CO)₅ where CASPT2 provided reliable assignment of low-lying excited states corresponding to 5d→π*CO excitations [10]. The method accurately captures spin-forbidden transitions and metal-centered excitations that challenge conventional TD-DFT approaches. LF-DFT, which incorporates ligand field theory concepts, has emerged as a valuable alternative for calculating multiplets of transition metal complexes, particularly when using functionals like OPBE, OPBE0, or SSB-D that accurately describe spin-state splittings [10].

Table 2: Accuracy Benchmarks for Transition Metal Complexes

| Method | CrF₆ Relative Energies (kcal/mol) | MnO₄⁻ Excitation Error (eV) | [Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻ Spin States | HRe(CO)₅ Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD-DFT (B3LYP) | Varies significantly | 0.3-0.5 | Qualitative errors | Mixed accuracy |

| TD-DFT (CAM-B3LYP) | Improved but functional-dependent | 0.2-0.4 | Better but not quantitative | Good with range separation |

| CASSCF/CASPT2 | Quantitative agreement | 0.1-0.2 | Quantitative | Excellent agreement [10] |

| DFT/MRCI | Not reported | 0.1-0.3 | Good performance | Comparable to CASPT2 [10] |

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

Computational cost represents a critical practical consideration when selecting methodological approaches. TD-DFT offers the most favorable scaling, typically between O(N³) and O(N⁴) depending on implementation, making it applicable to systems containing hundreds of atoms [9]. Recent algorithmic improvements, such as the source-oriented Euler backward iterative (EBI) solver, have demonstrated 73-90% reductions in chemistry computation time compared to traditional Gear solvers, significantly enhancing TD-DFT's practical utility for long-term applications [12].

CASSCF calculations exhibit exponential scaling with active space size, constraining applications to smaller systems or those with limited active spaces. A CASSCF calculation with an active space of (10e,10o) is typically 100-1000 times more computationally demanding than a TD-DFT calculation on the same system. The recent development of density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) and selected configuration interaction (SCI) methods helps mitigate but does not eliminate these scaling limitations.

ML-enhanced approaches feature favorable scaling once trained, with computational costs dominated by descriptor calculation and model evaluation. Training requires substantial upfront investment in reference calculations, but subsequent predictions can approach O(N) scaling for localized models, enabling applications to very large systems that would be prohibitive for conventional quantum chemistry methods.

Table 3: Computational Cost Comparison

| Method | Formal Scaling | Time for 50-Atom System | Parallel Efficiency | Memory Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD-DFT | O(N³)-O(N⁴) | Minutes to hours | Good | Moderate |

| CASSCF | Exponential with active space | Hours to days | Limited | Very high |

| CASPT2 | O(N⁵)-O(N⁷) | Days for large active spaces | Poor | Extreme |

| ML-Enhanced | O(N) to O(N³) after training | Seconds after training | Excellent | Low after training |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TD-DFT Calculation Workflow

System Preparation and Functional Selection: Begin with geometry optimization of the ground state using DFT with an appropriate functional (B3LYP, PBE0, or ωB97X-D recommended) and basis set (def2-TZVP for metals, def2-SVP for ligands) [11]. For transition metal systems, include relativistic effects through effective core potentials (ECPs) for elements beyond the first row [10]. Select functional based on target excitations: global hybrids (B3LYP, PBE0) for valence excitations, range-separated hybrids (CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X-D) for charge-transfer states, and specialized functionals (OPBE, SSB-D) for spin-state energetics [10].

Calculation Setup: Specify the number of excited states based on the spectral range of interest (typically 10-50 states). For UV-Vis simulations, include solvent effects using polarizable continuum models (PCM, COSMO) with appropriate dielectric constants [9]. For systems with unpaired electrons, use spin-unrestricted formalisms. For metal clusters and nanoparticles, verify the absence of artifactual charge transfer using tools like density-based index analysis [10].

Analysis and Validation: Examine natural transition orbitals (NTOs) for intuitive characterization of excitations. Calculate oscillator strengths for dipole-allowed transitions and compare with experimental molar absorptivity. Validate against experimental spectra when available, focusing on both peak positions and relative intensities. For inorganic chromophores, compare with ligand field theory predictions and high-level reference calculations where possible [10].

CASSCF Protocol for Inorganic Photochemistry

Active Space Selection: The critical step in CASSCF calculations involves selecting an appropriate active space, denoted (ne, no), where ne is the number of electrons and no is the number of orbitals. For transition metal complexes, include metal d orbitals and relevant ligand orbitals involved in bonding and excitations. For first-row transition metals, typical active spaces range from (5e,5o) for metal-centered excitations to (12e,12o) for metal-ligand charge transfer systems. Verify active space adequacy through orbital entanglement measures and natural orbital occupation numbers.

State-Averaged Calculations: Perform state-averaged CASSCF (SA-CASSCF) over the relevant electronic states to ensure balanced description of potential energy surfaces. Include all states of interest in the averaging, typically 3-10 states depending on the complexity of the photochemical process. Use equal weights unless specific states are targeted.

Dynamic Correlation Treatment: Apply second-order perturbation theory (CASPT2) to recover dynamic correlation effects essential for quantitative accuracy. Use an imaginary level shift (0.1-0.3 Hartree) to avoid intruder state problems. For spectroscopic properties, apply the IPEA shift (0.25 Hartree) to improve agreement with experimental excitation energies. For transition metal systems, verify convergence with respect to basis set (ANO-RCC basis sets recommended) and active space size [10].

ML-Enhanced Approach Implementation

Training Set Construction: Select diverse representative structures that span the configuration space of interest using molecular dynamics sampling or geometric heuristics. Compute reference properties using high-level theory (CCSD(T), CASPT2, or DFT/MRCI for excitation energies) [10]. Ensure adequate representation of rare events and transition states if modeling photochemical reactions.

Model Selection and Training: Choose appropriate ML architecture based on data availability and system size: kernel-based methods (Gaussian process regression) for small datasets (<10,000 points) or neural networks for larger datasets. Use rotationally invariant descriptors (SOAP, ACE) that encode atomic environments. Regularize models to prevent overfitting and validate using rigorous train-test splits.

Uncertainty Quantification and Active Learning: Implement uncertainty prediction to identify regions where model extrapolation is unreliable. Deploy active learning cycles where new calculations are triggered when uncertainty exceeds thresholds, progressively improving model reliability with minimal computational investment.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Software and Computational Resources

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian, ORCA, Molcas, Turbomole | Electronic structure calculations | Academic licensing, open source |

| Wavefunction Analysis | Multiwfn, ChemTools, JANPA | Orbital analysis, property calculation | Open source |

| ML Frameworks | SchNet, DeepMD, Amp, PhysNet | Machine learning potential development | Open source |

| Visualization Software | VMD, Chimera, Jmol | Molecular structure and property visualization | Free academic licensing |

| Specialized TD-DFT Codes | NWChem, Q-Chem, FHI-aims | Large-scale excited-state calculations | Academic licensing |

Workflow Integration and Decision Pathways

The selection of appropriate computational methods depends on multiple factors including system size, electronic structure complexity, property of interest, and available computational resources. The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic approach to method selection for inorganic photochemical research:

The validation of computational models for inorganic photochemical mechanisms requires careful matching of methodological approaches to specific scientific questions. TD-DFT provides the best combination of efficiency and accuracy for single-reference systems and routine spectroscopic predictions, particularly with modern range-separated and system-tuned functionals. CASSCF/CASPT2 remains indispensable for multi-reference problems, photochemical reaction pathways, and cases where electron correlation effects dominate. ML-enhanced approaches offer promising avenues for accelerating calculations and extending accurate modeling to larger systems, though they require careful validation. The optimal strategy for inorganic photochemistry often involves a multi-level approach, where cheaper methods screen chemical space and higher-level methods provide definitive characterization of key intermediates and transitions states, thus balancing computational efficiency with physical accuracy in model validation.

The Critical Role of Electronically Excited States in Photoreactivity

Electronically excited states of molecules are at the heart of photochemistry, photophysics, and photobiology, playing a critical role in diverse processes ranging from photosynthesis and human vision to photocatalysis and photodynamic therapy [13]. When a molecule absorbs light, it transitions to a higher-energy excited state, fundamentally altering its electronic structure and reactivity compared to its ground state. This transformation enables unique photoreactions that are often impossible through thermal pathways alone.

Understanding and predicting photoreactivity requires a detailed knowledge of potential energy surfaces, conical intersections, and the complex interplay between competing deactivation pathways. Precision photochemistry represents a transformative approach in this field, emphasizing that "every photon counts" and advocating for careful control over irradiation wavelength, photon flux, and reaction conditions to direct photochemical outcomes with unprecedented selectivity [14]. This paradigm shift, coupled with advanced spectroscopic techniques and computational methods, is revolutionizing how researchers investigate and harness excited-state processes.

The validation of computational models against experimental data remains crucial for advancing the field, particularly for inorganic photochemical mechanisms where metal-containing chromophores introduce additional complexity through spin-orbit coupling, metal-to-ligand charge transfer states, and rich photophysical behavior. This review examines current methodologies for studying excited-state dynamics, compares computational approaches with experimental validation, and provides resources for researchers investigating inorganic photoreactivity.

Fundamental Concepts in Excited-State Reactivity

The Four Pillars of Precision Photochemistry

Modern photochemistry recognizes four fundamental parameters that collectively determine photochemical outcomes: molar extinction coefficient (ελ), wavelength-dependent quantum yield (Φλ), chromophore concentration (c), and irradiation length (t) [14]. These "four pillars" are intrinsically linked and dictate the experimental conditions needed for selective photoreactions.

The molar extinction coefficient (ελ) quantifies how strongly a chromophore absorbs light at a specific wavelength, following the Beer-Lambert law. However, a crucial insight from precision photochemistry is that maximum absorption does not always correlate with maximum reactivity. Research has demonstrated that some systems exhibit enhanced photoreactivity when irradiated with red-shifted light relative to their absorption maximum [14].

The wavelength-dependent quantum yield (Φλ) represents the efficiency of a photochemical process at a specific wavelength, defined as the number of photochemical events per photon absorbed. The relationship between ελ and Φλ can be exploited to achieve orthogonal, cooperative, or antagonistic photochemical systems [14].

Chromophore concentration and irradiation time complete the four pillars, forming a dynamic interplay that determines selectivity in complex mixtures. Research on wavelength-orthogonal photo-uncaging molecules has demonstrated that preferential reactivity can shift as concentrations change throughout a reaction, necessitating careful consideration of all four parameters for optimal selectivity [14].

Key Photophysical Processes and Pathways

Following photoexcitation, molecules can undergo various competing processes that determine their ultimate photoreactivity:

- Internal Conversion (IC): Non-radiative transition between electronic states of the same spin multiplicity

- Intersystem Crossing (ISC): Non-radiative transition between electronic states of different spin multiplicity

- Fluorescence: Radiative decay from an excited singlet state to the ground state

- Phosphorescence: Radiative decay from an excited triplet state to the ground state

- Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer (ESIPT): Ultrafast proton transfer between electronegative centers along a pre-existing intramolecular hydrogen bond [15]

The competition between these pathways is strongly influenced by molecular structure, solvent environment, and the presence of heavy atoms that enhance spin-orbit coupling. In azanaphthalenes, for example, systematic variation of nitrogen atom positioning within a bicyclic aromatic structure leads to considerable differences in excited-state lifetimes and propensity for intersystem crossing versus internal conversion [16].

Table 1: Key Photophysical Processes and Their Characteristics

| Process | Spin Change | Timescale | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | No | Femtoseconds to nanoseconds | Transition dipole moment, rigidity of structure |

| Internal Conversion | No | Femtoseconds to picoseconds | Energy gap between states, vibrational coupling |

| Intersystem Crossing | Yes | Picoseconds to microseconds | Spin-orbit coupling, heavy atom effect |

| Phosphorescence | Yes | Microseconds to seconds | Spin-orbit coupling, temperature, molecular rigidity |

| ESIPT | No | Tens to hundreds of femtoseconds | Hydrogen bond strength, donor-acceptor distance |

Methodologies for Investigating Excited States

Experimental Approaches

Advanced spectroscopic techniques provide direct observation of excited-state dynamics:

Ultrafast Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (TAS) employs femtosecond laser pulses to initiate photoreactions and probe subsequent evolution across broad wavelength ranges. Recent applications to azanaphthalenes have revealed excited-state lifetimes spanning from 22 ps in quinoxaline to 1580 ps in 1,6-naphthyridine, with significant variations in intersystem crossing quantum yields across the molecular series [16]. These measurements involve exciting molecules at specific wavelengths (e.g., 267 nm) and interrogating with a broadband white-light continuum probe (340-750 nm) to track the appearance and decay of transient species [16].

Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy using upconversion techniques offers insights into early excited-state dynamics, particularly useful for studying intramolecular charge transfer and photoacidity. Applications to 4-hydroxychalcone systems have revealed solvent-dependent intramolecular charge transfer dynamics and proton-transfer processes occurring on sub-picosecond timescales [17].

Computational Modeling Strategies

Computational methods provide complementary atomic-level insights into excited-state processes:

Static Quantum Chemical Calculations determine critical points on potential energy surfaces, vertical excitation energies, and reaction barriers. High-level ab initio methods like ADC(2) and CC2 offer accurate excited-state descriptions for medium-sized molecules, while time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) extends applicability to larger systems [15]. The SCS-ADC(2) level of theory has demonstrated remarkable agreement with experimental data across azanaphthalene systems, successfully predicting subtle variations in excited-state behavior resulting from heteroatom positioning [16].

Non-adiabatic Dynamics Simulations track the real-time evolution of excited-state populations, capturing transitions between electronic states. These methods are particularly valuable for modeling ultrafast processes like ESIPT, which often occur on femtosecond timescales [15]. Combined quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches enable realistic modeling of photochemical processes in protein environments, elucidating how the surrounding matrix fine-tunes chromophore photophysics [18].

Machine Learning Accelerated Simulations represent a cutting-edge development, where ML models learn from quantum chemical reference calculations to predict excited-state energies, properties, and dynamics at significantly reduced computational cost [13]. These approaches are particularly valuable for extending simulation timescales and studying complex systems where direct quantum dynamics remain prohibitive.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

Validating computational models against experimental data is essential for assessing their predictive power for inorganic photochemical mechanisms. The systematic investigation of azanaphthalenes provides an excellent case study for method comparison [16].

Table 2: Performance of Computational Methods for Excited-State Properties of Azanaphthalenes

| Method | State Ordering Accuracy | Excitation Energies Error | SOC Strength Prediction | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCS-ADC(2) | High (matches experimental trends) | <0.2 eV for low-lying states | Quantitative agreement | High | Benchmarking, dynamics simulations |

| CC2 | Moderate to High | 0.1-0.3 eV | Moderate accuracy | Medium-High | Medium-sized molecules (<50 atoms) |

| TD-DFT (Hybrid) | Variable (functional-dependent) | 0.1-0.5 eV | Often underestimated | Low-Medium | Screening, large systems |

| CASSCF/PT2 | High (multireference systems) | 0.2-0.4 eV | Quantitative | Very High | Systems with strong electron correlation |

| Machine Learning | Depends on training data | Similar to reference method | Emerging capability | Very Low (after training) | High-throughput screening, long dynamics |

The table above summarizes the performance characteristics of various computational methods for excited-state simulations. The recently reported investigation of six azanaphthalene species (quinoline, isoquinoline, quinazoline, quinoxaline, 1,6-naphthyridine, and 1,8-naphthyridine) demonstrated that SCS-ADC(2) calculations could achieve "detailed and nuanced agreement with experimental data across the full set of six molecules exhibiting subtle variations in their composition" [16]. This agreement encompassed excited-state lifetimes, intersystem crossing quantum yields, and the impact of potential energy barriers on relaxation dynamics.

For inorganic photochemical systems, additional considerations become important, including the accurate description of charge-transfer states, spin-orbit coupling effects (crucial for triplet state formation), and the multiconfigurational character often present in transition metal complexes. Method selection should be guided by the specific photophysical process of interest and the required balance between computational cost and accuracy.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Ultrafast Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Protocol

Objective: To characterize excited-state lifetimes and identify transient species formed following photoexcitation.

Materials:

- Ti:sapphire amplifier system producing 100 fs pulses at 790 nm fundamental wavelength

- Optical parametric amplifier (OPA) for generating tuneable pump pulses

- CaF2 crystal for white-light continuum generation (340-750 nm)

- Spectrometer with CCD detector for signal acquisition

- Flow system for sample circulation to prevent degradation

Procedure:

- Dilute sample to appropriate optical density (typically 0.2-0.5 at excitation wavelength)

- Generate pump pulse at desired excitation wavelength (e.g., 267 nm for azanaphthalenes)

- Split white-light continuum into probe and reference beams

- Spatially and temporally overlap pump and probe beams in sample

- Record transient spectra at delay times from femtoseconds to nanoseconds

- Analyze data using global fitting procedures to extract decay-associated spectra

Data Analysis: Transient absorption data are typically fitted to a sum of exponentials: [ S(\lambda, \Delta t) = \sum{i=1}^{n} Ai(\lambda) \cdot \exp[-\Delta t/\taui] \otimes g(\Delta t,\lambda) ] where (Ai(\lambda)) represents decay-associated spectra, (\tau_i) are lifetimes, and (g(\Delta t,\lambda)) is the instrument response function [16].

Determination of Wavelength-Dependent Quantum Yields

Objective: To measure the efficiency of photochemical reactions as a function of irradiation wavelength.

Materials:

- Monochromatic light source (LEDs or laser diodes)

- Precision radiometer for photon flux determination

- Integrating sphere or calibrated spectrometer for actinometry

- High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or spectroscopy for product quantification

Procedure:

- Select irradiation wavelengths covering the chromophore absorption spectrum

- Measure photon flux at each wavelength using chemical actinometry

- Irrogate samples for controlled durations at each wavelength

- Quantify reaction conversion using appropriate analytical methods

- Calculate quantum yield using: [ \Phi_\lambda = \frac{\text{number of molecules reacted}}{\text{number of photons absorbed}} ]

Validation Considerations: Recent research emphasizes that quantum yield determination should ideally be performed with high wavelength resolution (1 nm intervals) to capture potentially sharp variations in photoreactivity, though this is currently limited by experimental practicality [14]. Action plots, which depict wavelength-dependent reactivity, often reveal significant mismatches with absorption spectra, highlighting the importance of direct quantum yield measurements rather than relying on absorption properties alone.

Visualizing Excited-State Dynamics and Methodologies

Diagram 1: Fundamental excited-state relaxation pathways and photochemical processes competing after photoexcitation.

Diagram 2: Computational model validation workflow integrating experimental data and machine learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Instrumentation for Excited-State Studies

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic Light Sources (LEDs, Lasers) | Provide precise wavelength control for selective excitation | Precision photochemistry, action plot determination [14] |

| Femtosecond Laser Systems | Generate ultrafast pulses for initiating and probing photoreactions | Transient absorption spectroscopy, fluorescence upconversion [16] [17] |

| Chemical Actinometers | Quantify photon flux for quantum yield determinations | Ferrioxalate, azobenzene, or other reference systems |

| SCS-ADC(2) Computational Method | High-accuracy quantum chemical method for excited states | Benchmarking, potential energy surface mapping [16] [15] |

| QM/MM Software | Modeling photochemical processes in protein environments | Photoreceptor studies, enzyme photocycles [18] |

| Azaaromatic Chromophores | Model systems for understanding heteroatom effects | Azanaphthalenes, nitrogen-containing heterocycles [16] |

| Chalcone Derivatives | UV-absorbing compounds with complex relaxation pathways | Sunscreen research, ESIPT studies [17] |

| Photoacid Systems (e.g., 4-Hydroxychalcone) | Compounds exhibiting excited-state proton transfer | Proton transfer dynamics, solvent interaction studies [17] |

| White-Light Continuum Generation Crystals (CaF₂) | Produce broadband probe pulses for transient spectroscopy | Ultrafast transient absorption measurements [17] |

The critical role of electronically excited states in photoreactivity continues to drive methodological innovations in both experimental characterization and computational modeling. The emerging paradigm of precision photochemistry emphasizes that controlling excited-state processes requires careful consideration of wavelength, photon flux, and reaction conditions, moving beyond simple absorption-based irradiation strategies.

The validation of computational models against precise experimental measurements remains essential for advancing our understanding of inorganic photochemical mechanisms. As demonstrated by studies on azanaphthalenes and other model systems, the integration of ultrafast spectroscopy, high-level electronic structure theory, and increasingly machine learning approaches provides a powerful framework for predicting and controlling photoreactivity. These validated models offer unprecedented opportunities for the rational design of photoactive molecules tailored for specific applications in photocatalysis, photomedicine, and energy conversion.

Future progress will likely depend on increased automation of action plot measurements, development of more accurate computational methods with lower computational cost, and the creation of comprehensive databases of wavelength-dependent quantum yields for diverse chromophore classes. Such resources will accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel photochemical processes for scientific and technological applications.

Validation is a critical process for establishing confidence in computational models used in inorganic photochemical mechanisms research. It moves beyond simple graphical comparisons to a rigorous, quantitative assessment of a model's predictive capabilities [19]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a comprehensive validation framework is essential for determining which models can be reliably applied to molecular design, catalyst development, and reaction prediction.

This framework stands on three fundamental pillars: accuracy (the closeness of a model's predictions to true values), transferability (a model's ability to maintain performance across diverse chemical domains and computational protocols), and applicability domain (the defined chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions) [20] [21] [22]. This guide objectively compares contemporary methods and metrics for evaluating these characteristics, providing experimental protocols and data to inform model selection and development for inorganic photochemistry applications.

Accuracy: Defining Predictive Closeness

Core Concepts and Error Analysis

In analytical chemistry and computational modeling, accuracy refers to the "closeness of the agreement between the result of a measurement and a true value" [20]. Since a true value is often indeterminate, accuracy is typically estimated by comparing measurements or predictions to a conventional true value, such as a high-fidelity experimental measurement or a result from an advanced computational method like coupled-cluster theory [20] [23].

Error, defined as the difference between a measured/predicted value (XI) and the true value (μ), is quantified as: error = XI - μ [20]. Understanding error requires distinguishing between two primary types:

- Systematic Error (Determinate Error): Consistent, reproducible deviations caused by defects in the analytical method, instrument malfunction, or analyst error. A procedure with systematic error always produces a mean value different from the true value, creating a bias [20].

- Random Error (Indeterminate Error): Unavoidable fluctuations inherent in every physical measurement due to instrumental limitations. Random error is equally likely to be positive or negative and sets the ultimate limit on accuracy regardless of replication [20].

Table 1: Types of Error in Chemical Measurements and Models

| Error Type | Cause | Effect | Reduction Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic (Determinate) | Defective method, improperly calibrated instrument, analyst bias | Consistent bias in one direction; affects accuracy | Method correction, instrument calibration, blank analysis |

| Random (Indeterminate) | Inherent measurement limitations, environmental fluctuations | Scatter around the true value; affects precision | Replication, improved measurement technology |

Accuracy vs. Precision

It is crucial to distinguish accuracy from precision. Precision describes the agreement of a set of results among themselves, independent of their relationship to the true value [20]. The International Vocabulary of Basic and General Terms in Metrology (VIM) further defines precision through:

- Repeatability: Closeness of agreement under the same conditions (same procedure, observer, instrument, location, short time period).

- Reproducibility: Closeness of agreement under changed conditions (different principle, method, observer, instrument, location, or time) [20].

High precision does not guarantee high accuracy, as systematic errors can produce consistently biased yet precise results. However, in the absence of systematic error, high precision indicates high accuracy relative to the measurement uncertainty [20].

Transferability: Cross-Domain Model Performance

Defining Transferability in Computational Chemistry

Transferability refers to a model's capability to maintain predictive accuracy across diverse chemical domains (e.g., molecules, crystals, surfaces) and computational protocols (e.g., different density functionals, basis sets) [21]. This is particularly important for universal machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) intended for applications like catalytic reactions on surfaces or atomic layer deposition processes, where simulations span multiple chemical environments [21].

The challenge arises because databases for different material classes are typically generated with different computational parameters. For instance, databases for inorganic materials often use semilocal functionals like PBE, while small-molecule databases may use hybrid functionals [21]. Simply combining these databases introduces significant noise, necessitating specialized training strategies for effective cross-domain knowledge transfer.

Strategies for Enhancing Transferability

Multi-Task Learning Frameworks represent an advanced approach for optimizing cross-domain transfer. In this framework, model parameters are divided into:

- Shared Parameters (θ_C): Universal across all databases, facilitating knowledge transfer.

- Task-Specific Parameters (θ_T): Optimized exclusively for each database/task [21].

Formally, this is represented as: DFTT(G) ≈ f(G; θC, θT), where DFTT is the reference label for task T, f is the MLIP model, and G is the atomic configuration [21]. Through a Taylor expansion, the model can be expressed as a common potential energy surface (PES) plus a task-specific contribution, allowing joint optimization of universal and domain-specific components [21].

Domain-Bridging Sets provide another powerful technique. Small, strategically selected cross-domain datasets (as little as 0.1% of total data) can align potential-energy surfaces across different datasets when combined with targeted regularization, synergistically enhancing out-of-distribution generalization while preserving in-domain accuracy [21].

Table 2: Transferability Assessment of Universal Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials

| Model/Strategy | Training Approach | Cross-Domain Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SevenNet-Omni | Multi-task learning on 15 databases; domain-bridging sets | State-of-the-art accuracy; reproduces high-fidelity r2SCAN energetics from PBE data | Requires careful parameter partitioning and regularization |

| DPA-3.1 | Multi-task training on diverse databases | Consistent accuracy in multi-domain applications | Performance may degrade across significant functional differences |

| UMA | Concurrent multi-database training | Good performance across chemical domains | Limited evaluation in complex multi-domain scenarios |

Applicability Domain: Defining Model Boundaries

The Role of Applicability Domain

The Applicability Domain (AD) of a quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) or computational model defines "the boundaries within which the model's predictions are considered reliable" [22]. It represents the chemical, structural, or biological space covered by the training data, ensuring predictions are based on interpolation rather than extrapolation [22]. According to OECD guidelines, defining the AD is mandatory for valid QSAR models used for regulatory purposes [22].

The AD concept has expanded beyond traditional QSAR to domains like nanotechnology, material science, and predictive toxicology [22]. In nanoinformatics, for instance, AD assessment helps determine if a new engineered nanomaterial is sufficiently similar to training set materials to warrant reliable prediction [22].

Methods for Determining Applicability Domain

Multiple algorithmic approaches exist for characterizing the interpolation space, each with distinct advantages:

- Range-Based and Geometric Methods: Include bounding box and convex hull approaches that define boundaries in feature space [22] [24].

- Distance-Based Methods: Utilize Euclidean, Mahalanobis, or other distance metrics to measure similarity to training data [22] [25].

- Probability-Density Distribution Methods: Use kernel density estimation (KDE) to account for data sparsity and complex region geometries [24].

- Leverage Values: For regression-based QSAR models, leverage values from the hat matrix of molecular descriptors define structural AD [22].

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) offers particular advantages, including: (i) a density value that acts as a distance measure, (ii) natural accounting for data sparsity, and (iii) trivial treatment of arbitrarily complex geometries of data and ID regions [24]. Unlike convex hull methods that may include large empty regions, KDE effectively identifies densely populated training regions where models are most reliable.

Evaluating and Optimizing AD Methods

With numerous AD methods available, each with hyperparameters, selection must be optimized for each dataset and mathematical model [25]. One evaluation approach uses the relationship between coverage and root-mean-squared error (RMSE):

Coverage = (Number of samples up to i in sorted order) / (Total number of samples) [25]

RMSEi = sqrt((1/i) × Σ(yobs,j - y_pred,j)²) [25]

The Area Under the Coverage-RMSE Curve (AUCR) serves as a quantitative metric for comparing AD methods, with lower AUCR values indicating better performance [25].

Integrated Validation Framework for Computational Models

Bayesian Validation Methodology

A comprehensive Bayesian methodology assesses model confidence by comparing stochastic model outputs with experimental data [19]. This approach computes:

- The prior distribution of the response, updated based on experimental observations using Bayesian analysis to compute a validation metric.

- Model error estimation that includes model form error, discretization error, stochastic analysis error (UQ error), input data error, and output measurement error [19].

The Bayes factor compares two models/hypotheses by evaluating the ratio: [P(observation|Mi) / P(observation|Mj)], which updates the prior probability ratio to the posterior probability ratio [19]. A Bayes factor >1.0 indicates support for model Mi over Mj.

Error Estimation and Combination

Total prediction error combines multiple error components nonlinearly [19]. Key error sources in computational chemistry models include:

- Model Form Error: Inherent in the mathematical formulation and approximations.

- Discretization Error: From numerical solution techniques (e.g., grid spacing in DFT).

- Stochastic Analysis Error: Uncertainty quantification limitations.

- Input Data Error: Propagation from uncertain input parameters.

- Output Measurement Error: Experimental reference data inaccuracies [19].

Table 3: Error Components in Computational Chemistry Models

| Error Component | Description | Common Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Model Form Error | Inherent approximations in physical model | Multi-scale methods, hybrid QM/MM, higher-level theory benchmarks |

| Discretization Error | Numerical approximation errors | Basis set convergence, grid refinement, k-point sampling |

| Input Data Error | Uncertainty in input parameters | Sensitivity analysis, uncertainty propagation, parameter optimization |

| Experimental Reference Error | Noise in training/validation data | Replication, error estimation, statistical treatment |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Assessment

Protocol for Accuracy Determination

- Reference Data Establishment: Select high-fidelity reference data (e.g., CCSD(T) calculations, well-characterized experimental measurements) as conventional true values [23].

- Model Prediction: Apply computational model to systems with known reference values.

- Error Calculation: Compute errors for each prediction using: error = X_I - μ [20].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate mean error (bias), standard deviation (precision), and root-mean-square error (overall accuracy).

- Error Type Identification: Use replicate measurements to distinguish systematic vs. random error components [20].

Protocol for Transferability Assessment

- Domain Definition: Identify distinct chemical domains and computational protocols relevant to application.

- Multi-Task Framework Implementation:

- Partition model parameters into shared (θC) and task-specific (θT) sets [21].

- Implement joint optimization through selective regularization.

- Domain-Bridging: Incorporate small cross-domain datasets (0.1-1% of total data) to align potential energy surfaces [21].

- Performance Evaluation: Quantify model performance on in-domain and out-of-distribution test sets.

- Transferability Metric: Calculate performance retention across domains relative to within-domain baselines.

Protocol for Applicability Domain Determination

- Feature Space Characterization: Calculate molecular descriptors or features representing chemical space [25].

- AD Method Selection: Choose multiple AD methods (e.g., range-based, distance-based, density-based) with various hyperparameters [25] [22].

- Double Cross-Validation: Perform DCV on all samples to calculate predicted y values [25].

- Coverage-RMSE Analysis:

- Sort samples by AD index values.

- Calculate coverage and RMSE, adding samples one by one [25].

- AUCR Calculation: Compute Area Under the Coverage-RMSE curve using: AUCR = Σ[(RMSEi + RMSE{i-1}) × (coveragei - coverage{i-1})/2] [25].

- Optimal AD Selection: Choose AD method and hyperparameters with lowest AUCR value [25].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Validation in Inorganic Photochemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, VASP | Provide high-fidelity reference data for accuracy assessment and training |

| Machine Learning Potentials | SevenNet-Omni, DPA-3.1, UMA | Enable large-scale simulations with quantum accuracy for transferability testing |

| Descriptor Calculation | Dragon, RDKit, Mordred | Generate molecular features for applicability domain characterization |

| AD Implementation Packages | DCEKit, various QSAR toolkits | Compute applicability domain boundaries and similarity metrics |

| Validation Metrics Software | Custom Bayesian validation tools, statistical packages | Quantify accuracy, precision, and model confidence |

Validating computational models for inorganic photochemical mechanisms requires integrated assessment across three dimensions. Accuracy ensures predictions match reference values within quantified uncertainty bounds. Transferability enables models to perform reliably across diverse chemical domains and computational protocols through multi-task learning and domain-bridging strategies. Applicability Domain defines boundaries for reliable prediction, with kernel density estimation and coverage-RMSE analysis providing robust determination methods.

A comprehensive validation framework combines Bayesian validation metrics, systematic error estimation, and optimized AD determination to establish model credibility. For researchers in inorganic photochemistry, this integrated approach provides the rigorous assessment needed for confident application of computational models in materials design, reaction prediction, and drug development.

From Theory to Therapy: Methodologies and Biomedical Applications of Validated Models

Computational chemistry relies on high-accuracy methods to predict molecular properties and reactivities, a crucial capability for research into inorganic photochemical mechanisms. Among the most advanced approaches are first-principles quantum chemical methods like coupled-cluster theory and data-driven machine learning techniques such as multi-task learning (MTL). Coupled-cluster theory, particularly CCSD(T), is often considered the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for its ability to provide nearly exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation for small molecules [26]. Meanwhile, multi-task learning has emerged as a powerful machine learning paradigm that improves model generalization by simultaneously learning multiple related tasks [27].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, examining their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, scalability, and applicability to inorganic systems. Understanding the complementary strengths and limitations of these approaches enables researchers to select appropriate tools for validating computational models of inorganic photochemical processes.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Coupled-Cluster Theory

Coupled-cluster theory is an ab initio quantum chemical method that provides highly accurate solutions to the electronic Schrödinger equation through an exponential wavefunction ansatz: |Ψ⟩ = e^T|Φ⟩, where |Φ⟩ is a reference wavefunction (typically Hartree-Fock) and T is the cluster operator that excites electrons from occupied to virtual orbitals [28]. The method systematically accounts for electron correlation effects through a hierarchy of approximations: CCSD (includes single and double excitations), CCSD(T) (adds perturbative triples), and up to full CI limit [28].

The CCSD(T) method is widely regarded as the "gold standard" for main-group molecular chemistry because it typically achieves chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol error) for thermochemical properties [26]. However, this accuracy comes at a steep computational cost of O(N^7) scaling with system size, where N represents the number of basis functions [28]. This prohibitive scaling limits direct CCSD(T) application to systems with approximately 10-100 atoms, depending on basis set size and computational resources [26].

Table 1: Coupled-Cluster Methods Hierarchy

| Method | Excitations Included | Computational Scaling | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD | Singles, Doubles | O(N^6) | Initial correlation energy |

| CCSD(T) | CCSD + Perturbative Triples | O(N^7) | Gold standard for main-group chemistry |

| CCSDT | Singles, Doubles, Triples | O(N^8) | Higher accuracy requirements |

| CCSDTQ | Through Quadruples | O(N^10) | Ultra-high accuracy, very small systems |

Multi-Task Learning

Multi-task learning is a machine learning paradigm that improves model performance by simultaneously learning multiple related tasks. In cheminformatics, MTL operates on the principle that related molecular properties share underlying representations, allowing knowledge transfer between tasks [27]. This approach is particularly valuable when data for individual properties is limited, as training data from extra tasks serves as an inductive bias, acting as implicit regularization that reduces overfitting [27].

MTL architectures in cheminformatics primarily use neural networks with either "hard" or "soft" parameter sharing. Hard parameter sharing involves sharing hidden layers between all tasks with only task-specific output layers, while soft parameter sharing gives each task its own model with regularized distance between parameters [27]. As Caruana noted, MTL improves over single-task learning through several mechanisms: amplification of statistical data, attention focusing (finding better signals in noisy data), eavesdropping (learning from simpler tasks), representation bias, and regularization [27].

Figure 1: Multi-Task Learning Architecture with Shared Representation

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Accuracy Benchmarks

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Methods and Systems

| Method | System Type | Property | Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T)/CBS | Organic Molecules | Reaction Thermochemistry | ~1 kcal/mol | [29] |

| ph-AFQMC | Transition Metal Complexes | Relative Energies | ~1-2 kcal/mol | [26] |

| ANI-1ccx (MTL) | Organic Molecules | Reaction Energies | ~1.5 kcal/mol | [29] |

| DFT (ωB97X) | Organic Molecules | Torsional Profiles | ~3-5 kcal/mol | [29] |

| MTL DNN | Tox21 Challenge | Toxicity Classification | ROC AUC: 0.832 | [27] |

| MTForestNet | Zebrafish Toxicity | Toxicity Classification | ROC AUC: 0.911 | [30] |

Coupled-cluster methods demonstrate exceptional performance across various benchmarks. For the GDB-10to13 benchmark containing molecules with 10-13 heavy atoms, CCSD(T)/CBS provides reference values with chemical accuracy [29]. The ANI-1ccx potential, trained using transfer learning to approach CCSD(T) accuracy, achieves a mean absolute deviation (MAD) of 1.5 kcal/mol for relative conformer energies within 100 kcal/mol of minima, outperforming direct DFT calculations (ωB97X/6-31g*) which show MAD of 1.7 kcal/mol [29].

Multi-task learning has shown remarkable success in cheminformatics challenges. In the Tox21 challenge, MTL provided the best model according to ROC AUC metric, with the networks learning chemical features resembling toxicophores identified by human experts on their hidden layers [27]. For zebrafish toxicity prediction across 48 endpoints, the novel MTForestNet algorithm achieved an AUC of 0.911, representing a 26.3% improvement over conventional single-task learning models [30].

Transition Metal Systems Performance

Transition metal complexes present particular challenges for computational methods due to strong static correlation effects from d and f orbitals [26]. While CCSD(T) typically yields sub-kcal/mol accuracy for main-group molecules, its performance for transition metal systems has been questioned [26]. The phaseless auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo (ph-AFQMC) method has demonstrated capability for chemically accurate predictions for challenging molecular systems beyond the main group, with relatively low O(N^3-N^4) cost and near-perfect parallel efficiency [26].

For cis- and trans-platinum dichloride in aqueous solution, combined quantum chemical and solvation methods successfully predicted relative thermodynamic stabilities. DFT (B3LYP) with COSMO solvation yielded a value of -0.8 kcal/mol vs. experimental -0.1 kcal/mol, while a combination of discrete and continuum solvation methods provided -1.5 ± 1.0 kcal/mol [31].

Table 3: Transition Metal Complex Calculation Performance

| Method | System | Predicted ΔG | Experimental ΔG | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT(B3LYP)/COSMO | PtCl₂(H₂O)₂ isomers | -0.8 kcal/mol | -0.1 kcal/mol | 0.7 kcal/mol |

| Discrete+Continuum | PtCl₂(H₂O)₂ isomers | -1.5 kcal/mol | -0.1 kcal/mol | 1.4 kcal/mol |

| CCSD(T) ecp | PtCl₂(H₂O)₂ gas phase | +0.1 kcal/mol | N/A | N/A |

Implementation and Workflows

Coupled-Cluster Implementation

Solving coupled-cluster equations for large systems presents significant computational challenges. The CCSD equations correspond to a polynomial set of equations of fourth order, with the number of cluster amplitudes often exceeding 10^10 in the presence of strong correlation effects [28]. Traditional approaches use the direct inversion of iterative subspace (DIIS) method to accelerate convergence [28]. More recently, Newton-Krylov methods have been employed, using Krylov iterative methods to compute Newton corrections to approximate coupled-cluster amplitudes [28].

Figure 2: Coupled-Cluster Computational Workflow

For systems with strong static correlation, tailored coupled cluster approaches like TCCSD incorporate information from external calculations (e.g., DMRG or CASSCF) to handle multireference character [28]. This is particularly important for transition metal complexes where near-degeneracies can challenge single-reference methods.

Multi-Task Learning Implementation

Multi-task learning implementations in cheminformatics vary in architecture. The MTForestNet approach uses a progressive network where each node represents a random forest model learned from a specific task [30]. The training process starts with model training for each task separately, then iteratively concatenates original feature vectors with score outputs from previous layers to build subsequent layers until validation performance plateaus [30].

For neural network-based MTL, the training process involves:

- Architecture Selection: Choosing between hard parameter sharing (shared hidden layers) or soft parameter sharing (separate models with regularization) [27]

- Data Preparation: Curating datasets for multiple related properties, which may have distinct chemical spaces [30]

- Joint Training: Simultaneously optimizing all tasks with appropriate weighting of loss functions

- Validation: Assessing performance on held-out test sets for all tasks

In cases where tasks have distinct chemical spaces (sharing only 1.3% common chemicals in one study), progressive stacking approaches like MTForestNet significantly outperform conventional MTL methods [30].

Scalability and Computational Requirements

Computational Scaling and Resource Demands

Table 4: Computational Requirements Comparison

| Method | Computational Scaling | Typical System Size | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | O(N^7) | 10-50 atoms | High-performance computing clusters |

| DFT | O(N^3-N^4) | 100-1000 atoms | Workstations to clusters |

| ph-AFQMC | O(N^3-N^4) | 10-100 atoms | GPU-accelerated clusters |

| MTL (Inference) | O(1) after training | Virtually unlimited | GPU or CPU |

| MTL (Training) | Data-dependent | Thousands to millions of compounds | GPU recommended |

The computational cost of CCSD(T) limits its application to small systems, though local correlation approximations and fragment-based methods can extend its reach [26]. For example, a CCSD(T) calculation for a molecule with about 20 heavy atoms and a polarized double-zeta basis set can require days of computation on multiple cores [29].

In contrast, once trained, MTL models can predict properties almost instantaneously. The ANI-1ccx potential, which approaches CCSD(T) accuracy, is "billions of times faster" than direct CCSD(T)/CBS calculations for organic molecules containing C, H, N, and O atoms [29]. This speed advantage makes ML methods suitable for high-throughput screening of virtual compound libraries.

Transfer Learning and Hybrid Approaches

Transfer learning bridges the accuracy-scalability gap by leveraging large amounts of lower-accuracy data and smaller amounts of high-accuracy data. The ANI-1ccx potential exemplifies this approach: initially trained on 5 million DFT molecular conformations, then retrained on approximately 500,000 conformations at CCSD(T)/CBS level accuracy [29]. This strategy achieves coupled-cluster accuracy while maintaining transferability across chemical space.

For the ANI-1ccx potential, transfer learning provided a 23% improvement in RMSD compared to training only on the smaller CCSD(T) dataset, and a 36% improvement over the DFT-trained model [29]. This demonstrates how hybrid approaches can maximize the strengths of both quantum chemical and machine learning methods.

Table 5: Key Research Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANI-1ccx | Neural Network Potential | Approaches CCSD(T) accuracy for organic molecules | GitHub (ASE_ANI) |

| COSMO | Solvation Model | Models solvent effects in quantum chemistry | Quantum chemistry packages |

| EFP | Effective Fragment Potential | Models solute-solvent interactions | Quantum chemistry packages |

| MTForestNet | Multi-Task Learning Algorithm | Handles tasks with distinct chemical spaces | Custom implementation |

| Newton-Krylov | CC Solver | Accelerates convergence of CC equations | Custom implementation |

| ph-AFQMC | Quantum Monte Carlo | Chemically accurate method for transition metals | Research codes |