Troubleshooting Wavelength-Dependent Photochemical Efficiency: From Molecular Mechanisms to Optimized Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and resolve inefficiencies in photochemical processes.

Troubleshooting Wavelength-Dependent Photochemical Efficiency: From Molecular Mechanisms to Optimized Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and resolve inefficiencies in photochemical processes. It explores the fundamental principles governing wavelength-dependent reactivity, details advanced methodologies like photochemical action plots for systematic analysis, presents targeted troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and establishes validation protocols for comparing photoreactive systems. By integrating foundational science with practical optimization techniques, this guide aims to enhance the precision and efficacy of photochemistry in applications ranging from photopharmacology to catalytic synthesis.

Unraveling the Core Principles: Why Wavelength Dictates Photochemical Reactivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is excitation-wavelength-dependent (Ex-De) photochemistry, and why does it challenge traditional rules? Excitation-wavelength-dependent (Ex-De) photochemistry refers to the phenomenon where the outcome of a photochemical reaction—including the reaction products, pathway, or quantum yield—changes depending on the specific wavelength of light used for excitation [1]. This challenges a long-held, unfounded extension of Kasha's Rule to photochemistry. While Kasha's Rule correctly states that luminescence (fluorescence or phosphorescence) typically occurs only from the lowest vibrational level of the first excited electronic state (S₁ or T₁), it was often assumed that photochemical reactions also proceed exclusively from these lowest states [1]. Ex-De phenomena demonstrate that photochemistry can, in fact, originate from higher electronic excited states (Sₙ, n>1) or different vibrational levels within a state, operating on ultrafast timescales that compete with internal conversion and vibrational relaxation [1] [2].

Q2: What are the primary mechanisms behind Ex-De phenomena? The main mechanisms can be separated into two categories [1]:

- Interstate Dynamics: Different electronic excited states (e.g., S₁, S₂, S₃), which are populated by different wavelengths, lead to distinct reaction pathways. Excitation to a higher state might access a different potential energy surface or conical intersection, leading to unique products compared to excitation to S₁ [2] [3].

- Intrastate Dynamics: Even within the same electronic absorption band, excitation with different wavelengths deposits different amounts of vibrational energy. This can open up specific reaction channels that require overcoming an activation barrier, a process controlled by the excess internal energy provided by the photon [1] [2]. Additionally, specific molecular processes like Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer (ESIPT) and Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer (PCET) have been identified as mechanisms that can exhibit excitation-wavelength-dependent luminescence, leading to multiple emission colors from a single molecule [4] [5].

Q3: My photochemical reaction yield is lower than expected. Could the light source be the issue? Yes. A common troubleshooting point is the emission spectrum of your light source. Many light sources, including LEDs, are not perfectly monochromatic [6]. If a minor part of your light source's emission spectrum overlaps with an absorption band of a reactant, product, or impurity that has a low quantum yield or leads to side reactions, it can significantly alter the observed kinetics and final yield [6]. Always characterize the full emission spectrum of your light source and the absorbance spectra of all reaction components.

Q4: How can I quantitatively predict the outcome of a wavelength-dependent reaction? Predicting conversion requires a wavelength-resolved approach. You need to integrate several parameters [6]:

- The emission spectrum of your light source.

- The wavelength-dependent molar attenuation coefficient (ελ) of all light-absorbing species.

- The wavelength-dependent reaction quantum yield (Φλ) of the photoreaction. By combining these parameters with the laws of photochemistry (Beer-Lambert, Stark-Einstein), you can create a numerical model to simulate reaction progress and predict conversion for different light sources [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irreproducible reaction kinetics | Inconsistent light source positioning or power output, violating the inverse-square and Bunsen-Roscoe laws [6]. | Use a fixed-geometry photoreactor (e.g., 3D-printed scaffold) to ensure a reproducible distance between the light source and sample vial [6]. |

| Unexpected side products | Polychromatic light source emitting wavelengths that activate undesired chromophores or reaction pathways [6]. | Use band-pass or cut-on filters to narrow the emission spectrum. Switch to a more monochromatic source (e.g., laser, narrow-band LED). |

| Low or varying quantum yield | 1. Wavelength-dependent quantum yield.2. Unaccounted light absorption by the reaction vessel [6]. | 1. Measure the reaction quantum yield at different wavelengths [6].2. Measure the wavelength-dependent transmittance of your reaction vessel (e.g., glass, quartz) and account for it in calculations [6]. |

| No reaction occurs despite light absorption | The excited state decays via non-reactive pathways (e.g., fast internal conversion, fluorescence) faster than the chemical reaction can occur [1]. | Try exciting into a different electronic state (shorter wavelength) that may have a more favorable reaction pathway or slower relaxation [1] [2]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Determining Wavelength-Dependent Quantum Yield (Φλ)

The reaction quantum yield is the most critical metric for quantifying Ex-De phenomena [1] [6].

Key Steps:

- Setup: Use a tunable laser system or a set of monochromatic LEDs with known, characterized emission spectra and power output [6].

- Calibration: Precisely measure the photon flux (photons per second) reaching the reaction vessel using a calibrated power meter or chemical actinometer.

- Absorption Measurement: Obtain the UV-Vis absorption spectrum of your reactant to identify relevant excitation wavelengths.

- Irradiation & Analysis: Irigate the sample at a specific wavelength and use analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC, NMR) to quantify the formation of product over time.

- Calculation: The reaction quantum yield (Φλ) is calculated using the formula below, where

n_productis the number of product molecules formed, andn_photonsis the number of photons absorbed by the reactant at that wavelength.

Φλ = n_product / n_photons

Example Data: Wavelength-Dependent Quantum Yields The following table summarizes quantitative data from a study on a photoenol ligation reaction, demonstrating a clear wavelength dependence [6].

| Wavelength (nm) | Reaction Quantum Yield (Φλ) | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 307 | 0.115 ± 0.023 | High-energy transition accessible; most efficient pathway [6]. |

| 345 - 400 | ~0.028 ± 0.0037 | Plateau region; reaction proceeds from the lowest vibrational level of the primary excited state [6]. |

| 420 | 0.0026 ± 0.0010 | Low-efficiency tail of the absorption band; reaction is barely feasible [6]. |

Protocol 2: Investigating Wavelength-Dependent Photoproducts

Key Steps:

- Monochromatic Irradiation: Perform separate reactions using light sources of different, well-defined wavelengths.

- Product Analysis: Use high-resolution analytical techniques like GC-MS or LC-MS to identify and quantify the reaction products from each experiment.

- Channel Assignment: Correlate specific wavelengths with the formation of specific products to map reaction channels.

Case Study: Photodissociation of CF₃COCl This molecule exhibits complex wavelength-dependent photochemistry, as shown in the table below [2].

| Excitation Wavelength | Dominant Photodissociation Channel | Observation & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| > 260 nm | C–Cl cleavage | Preferential pathway when populating the first excited state [2]. |

| 193 nm | Three-body fragmentation (CF₃ + CO + Cl) | Prevails upon populating higher electronic states (S₂, S₃). A consecutive mechanism where fast Cl release is followed by slower CO dissociation on the ground state [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Tunable Laser System / Monochromatic LEDs | Provides precise control over the excitation wavelength, which is the fundamental variable in Ex-De studies [6]. |

| 3D-Printed Photoreactor Scaffold | Ensures reproducible geometry between the light source and sample, critical for accurate photon dose calculation and experimental reproducibility [6]. |

| Chemical Actinometers | Used to calibrate the photon flux of a light source by employing a well-understood photochemical reaction with a known quantum yield [6]. |

| ESIPT/PCET Active Molecules (e.g., HBO-pBr) | Model compounds, such as substituted benzothiazoles, that exhibit clear Ex-De fluorescence due to mechanisms like ESIPT, making them excellent for proof-of-concept studies [4] [5]. |

| Wavelength-Specific Filters | Used to isolate specific regions of a light source's spectrum, preventing unwanted side reactions from polychromatic emission [6]. |

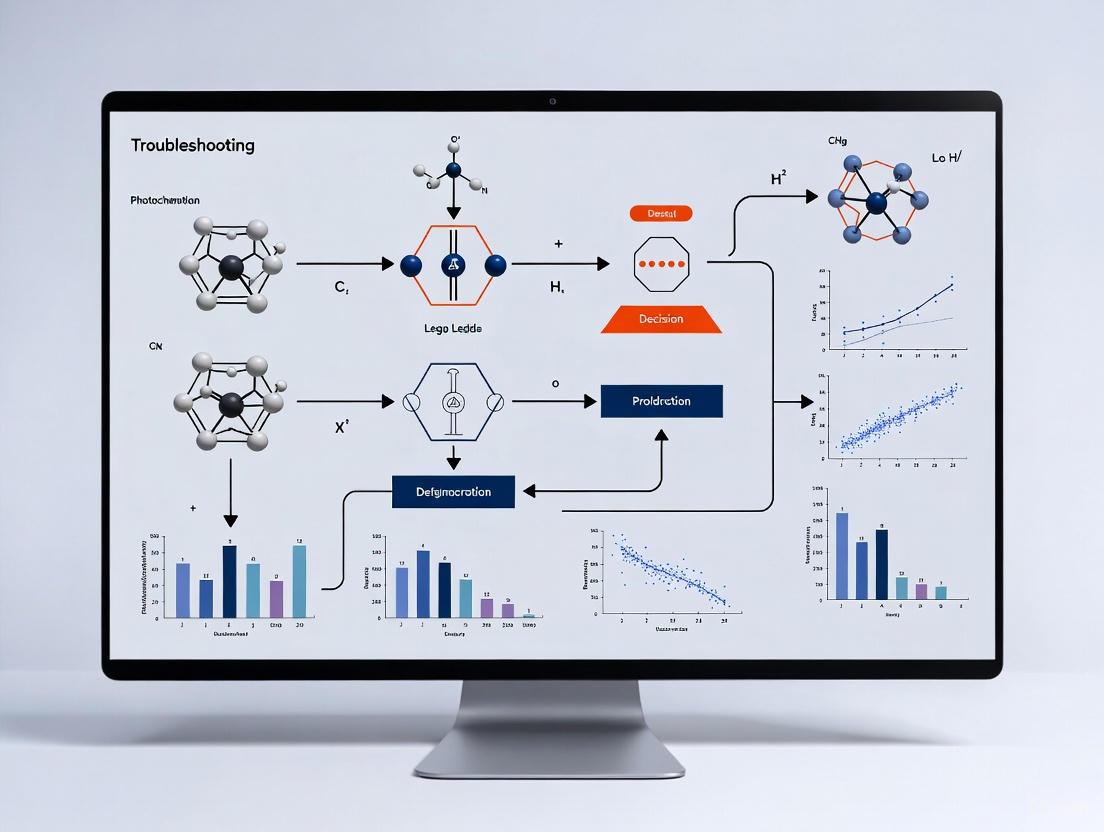

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Ex-De Photochemistry Workflow

Troubleshooting wavelength-dependent photochemical efficiency requires a deep understanding of the underlying photophysical mechanisms that govern molecular behavior under light excitation. Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer (ESIPT) and Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer (PCET) represent two fundamental processes that can dramatically influence emission properties, quantum yields, and excitation wavelength dependence in molecular systems. ESIPT is an ultrafast photophysical process where a proton transfers between two electronegative centers within the same molecule along a pre-existing intramolecular hydrogen bond after photoexcitation. This process typically results in a large Stokes shift and dual fluorescence, serving as a mechanism for excellent photostability in natural and artificial molecular systems. PCET involves the coupled transfer of both a proton and an electron, playing a crucial role in enhancing the efficiency of redox reactions and controlling reaction selectivity in biological energy conversion and enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The recent discovery of systems integrating both ESIPT and PCET mechanisms has opened new possibilities for designing advanced materials with exceptional excitation-wavelength-dependent properties for sensing, imaging, and anti-counterfeiting applications [7] [8] [9].

Core Mechanism Explanations

The ESIPT Mechanism: Fundamentals and Characteristics

The ESIPT process follows a characteristic four-level photocycle that begins with photoexcitation of the ground-state enol form to its Franck-Condon excited state. The molecule then undergoes an ultrafast proton transfer, typically in the sub-100 femtosecond timescale, to form the excited keto tautomer. This keto form relaxes radiatively to the ground state, emitting strongly red-shifted fluorescence, before undergoing reverse ground-state intramolecular proton transfer (GSIPT) to regenerate the initial enol form. The large Stokes shift associated with ESIPT—often exceeding 150 nm—results from the significant structural reorganization and energy difference between the enol and keto forms [10] [11] [9].

The hydrogen bond geometry between the proton donor (typically hydroxyl or amino groups) and proton acceptor (often carbonyl or imine groups) plays a critical role in ESIPT efficiency. Key structural parameters indicating favorable ESIPT conditions include:

- Short hydrogen bond distances between donor and acceptor atoms (often <1.8 Å in excited state)

- Nearly linear hydrogen bond angles (approaching 180°)

- Enhanced hydrogen bond strength in the excited state compared to ground state

- Rigid molecular frameworks that minimize competing non-radiative decay pathways

The strength of the intramolecular hydrogen bond can be experimentally probed through infrared spectroscopy, with redshifted O-H stretching frequencies indicating stronger hydrogen bonding that facilitates proton transfer [11] [12] [13].

The PCET Mechanism: Fundamentals and Characteristics

Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer represents a more complex mechanism where proton and electron transfer events are coupled, potentially occurring in a concerted, sequential, or asynchronous manner. In photochemical systems, PCET can be triggered by photoexcitation that alters both the electronic distribution and proton affinity within a molecule. The coupling between proton and electron transfer can significantly enhance the efficiency of photochemical reactions by lowering activation barriers and controlling reaction selectivity. PCET mechanisms play vital roles in biological systems, including photosynthesis and cellular respiration, where they facilitate efficient energy conversion through transmembrane proton gradients [7] [8] [14].

Integrated ESIPT-PCET Systems

Recent research has demonstrated that ESIPT and PCET mechanisms can be integrated within a single molecular system to produce novel photophysical behavior. A groundbreaking example involves the introduction of a spinacine moiety to traditional ESIPT fluorophore 2-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)benzothiazole, creating a system where ESIPT dominates under higher-energy excitation while PCET governs the luminescence mechanism under lower-energy excitation. This mechanism switching enables remarkable excitation-wavelength-dependent luminescence where emission color can be modulated from greenish-blue to yellow-green simply by varying the excitation wavelength. Such integrated systems achieve exceptionally high fluorescence quantum yields up to 69.6% when embedded in polymer matrices, along with room-temperature phosphorescence, making them highly valuable for advanced applications in anti-counterfeiting and molecular sensing [7] [5] [8].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

FAQ 1: Why does my ESIPT-capable compound show no dual fluorescence or large Stokes shift?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Excessive molecular flexibility: Incorporate structural constraints or rigidify the molecular framework to prevent non-radiative decay through rotational or vibrational modes. Studies on quinoline-pyrazole derivatives show that fused six-membered hydrogen bond rings enhance ESIPT efficiency compared to more flexible non-fused structures [12].

- Insufficient hydrogen bond strength: Modify substituents to enhance intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Electron-withdrawing groups on the proton acceptor and electron-donating groups on the proton donor typically strengthen hydrogen bonds. Theoretical calculations demonstrate that hydrogen bond strength increases in the excited state when proper substituents are employed [11] [15].

- Competing non-radiative pathways: Evaluate and minimize processes such as twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) or intersystem crossing that can quench ESIPT fluorescence. In salicylideneaniline derivatives, meta- and ortho-substitutions can promote TICT states that prevent ESIPT [15].

- Solvent interference: Use aprotic solvents to prevent competitive intermolecular hydrogen bonding with protic solvents that can disrupt the intramolecular hydrogen bond necessary for ESIPT [5] [8] [13].

FAQ 2: Why is the quantum yield of my wavelength-dependent emitter significantly lower than literature values?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Molecular purity issues: Purify compounds using techniques such as HPLC to eliminate trace impurities that can quench excited states. The importance of purity was highlighted in recent ESIPT-PCET research where HPLC analysis confirmed compound purity before photophysical characterization [5] [8].

- Inadequate rigidification: Embed molecules in rigid matrices like poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) to restrict molecular motion and reduce non-radiative decay. The PVA matrix dramatically increased quantum yields to 55.6-69.6% in the integrated ESIPT-PCET system [7] [5].

- Concentration effects: Dilute samples to avoid aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) or check for concentration-dependent formation of excimers/exciplexes.

- Oxygen quenching: Ensure proper deoxygenation of solutions using freeze-pump-thaw cycles or nitrogen purging, particularly for systems exhibiting phosphorescence.

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between ESIPT and PCET mechanisms in my system?

Diagnostic Approaches:

- Excitation wavelength dependence: ESIPT typically shows consistent emission profiles regardless of excitation wavelength (following Kasha's rule), while PCET-dominated processes may exhibit significant excitation-wavelength-dependent emission changes [7] [8].

- Temperature-dependent studies: ESIPT processes often show enhanced efficiency at lower temperatures due to reduced vibrational quenching, while PCET may exhibit different temperature dependencies based on the electron-proton coupling.

- Deuterium isotope effects: Significant deuterium isotope effects on reaction rates suggest proton transfer is rate-limiting, characteristic of ESIPT.

- Electrochemical correlations: Combine spectroscopic techniques with electrochemical measurements to detect coupled electron-proton transfer events indicative of PCET [7] [14].

FAQ 4: What factors control the switching between ESIPT and PCET mechanisms?

Control Parameters:

- Excitation energy: Higher-energy excitation may populate states favoring ESIPT, while lower-energy excitation might access PCET pathways, as demonstrated in the spinacine-modified benzothiazole system [7] [5] [8].

- Temperature modulation: Lower temperatures can enhance ESIPT by reducing competing non-radiative pathways, while specific temperatures might favor PCET through thermal population of key vibrational states.

- Molecular engineering: Strategic modification of proton donor/acceptor strengths and redox potentials can tune the balance between ESIPT and PCET pathways.

- Environmental rigidity: Rigid matrices can selectively suppress molecular motions required for one mechanism while preserving the other [7] [8] [13].

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Performance

FAQ 5: How can I enhance the excitation wavelength dependence in my photoluminescent system?

Optimization Strategies:

- Create multiple excited states: Design molecules with distinct excited states that can be selectively populated by different excitation energies. The presence of multiple excited states is a prerequisite for excitation-wavelength-dependent behavior [5] [8].

- Incorporate mechanism-switching motifs: Integrate structural elements that enable different photophysical mechanisms (ESIPT vs. PCET) under different excitation conditions, as demonstrated by the spinacine-modified system [7] [8].

- Modulate energy gaps: Engineer large energy gaps between excited states to inhibit internal conversion processes and promote emission from higher-energy states [5] [8].

- Utilize hybrid materials: Combine organic chromophores with metallic elements or nanoparticles to introduce new energy-level structures for electronic transitions [5] [8].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Characterizing ESIPT Activity

Materials Needed:

- Purified sample compound

- Spectroscopic-grade solvents (methanol, dichloromethane, acetonitrile, n-hexane)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Fluorometer with variable excitation capabilities

- Temperature-controlled sample holder

- HPLC system for purity verification (optional but recommended)

Procedure:

- Prepare dilute solutions (typically 10-50 μM) of the compound in solvents of varying polarity.

- Record UV-Vis absorption spectra from 250-500 nm to identify absorption maxima.

- Collect fluorescence emission spectra using excitation wavelengths corresponding to absorption maxima.

- Measure excitation spectra while monitoring at the emission maxima.

- Calculate Stokes shifts by comparing the lowest-energy absorption maximum with the emission maximum.

- Repeat measurements at different temperatures (180-300 K) to observe temperature dependence.

- Analyze spectral data for dual emission bands characteristic of ESIPT.

- Verify purity via HPLC if anomalous results are obtained [5] [8] [13].

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Large Stokes shifts (>150 nm) suggest possible ESIPT activity

- Dual emission indicates coexistence of enol and keto forms

- Temperature-dependent emission switching confirms ESIPT behavior

- Redshifted O-H stretching frequencies in IR spectra indicate strong intramolecular hydrogen bonds [11] [13]

Protocol for Probing PCET Involvement

Materials Needed:

- Purified sample compound

- Electrochemical workstation

- Spectroelectrochemical cell

- Deuterated solvents for isotope studies

- Transient absorption spectroscopy system (for advanced characterization)

Procedure:

- Perform cyclic voltammetry in dry, degassed solvents to determine redox potentials.

- Conduct spectroelectrochemical measurements to correlate spectral changes with applied potentials.

- Compare kinetic isotope effects using protonated vs. deuterated solvents.

- Utilize transient absorption spectroscopy to monitor coupled electron-proton transfer dynamics.

- Apply varying excitation wavelengths to detect mechanism switching.

- Correlate electrochemical data with spectroscopic changes [7] [14].

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Potential-dependent spectral changes indicate electrochemical activity

- Significant deuterium isotope effects (kH/kD > 2) suggest proton transfer involvement

- Synchronous changes in redox state and protonation state indicate PCET

- Excitation-wavelength-dependent emission not following Kasha's rule suggests PCET contribution [7] [8] [14]

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparison of Photophysical Properties

Table 1: Key Photophysical Parameters for ESIPT and PCET Systems

| Parameter | Traditional ESIPT Systems | Integrated ESIPT-PCET Systems | Measurement Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stokes Shift | 150-200 nm | Variable with excitation wavelength | Solution phase, room temperature |

| Fluorescence Quantum Yield | Typically <40% | Up to 69.6% | In PVA film, λex: 363-396 nm |

| Emission Color Tuning | Limited range | Greenish-blue to yellow-green | By changing excitation wavelength |

| Temperature Response | Moderate | Strong switching behavior | 180-300 K in methanol |

| Mechanism | Primarily ESIPT | ESIPT and PCET switching | Dependent on excitation energy |

| Dual Emission | Common | Enhanced with additional room-temperature phosphorescence | Solid matrix |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solution Approaches | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|

| No ESIPT fluorescence | Weak intramolecular H-bond, competing non-radiative pathways | Strengthen H-bond with appropriate substituents, rigidify structure | [11] [12] [15] |

| Low quantum yield | Molecular flexibility, impurity quenching | Use rigid matrices, purify compounds, exclude oxygen | [7] [5] [13] |

| No excitation wavelength dependence | Single dominant emission mechanism | Design multiple excited states, incorporate mechanism-switching motifs | [7] [5] [8] |

| Inconsistent results | Solvent effects, temperature fluctuations | Control environmental factors, use temperature-regulated measurements | [8] [13] |

| No PCET signature | Weak electron-proton coupling, inappropriate detection methods | Modify redox potentials, use spectroelectrochemical techniques | [7] [14] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | Rigid matrix for enhancing quantum yield | Improves quantum yield by restricting molecular motion |

| Spectroscopic-grade solvents | Solvent environment control | Use aprotic solvents for ESIPT, vary polarity for mechanism studies |

| Deuterated solvents | Isotope effect studies | Identify proton transfer rate-limiting steps |

| HPLC-grade compounds | Purity verification | Essential for reliable photophysical measurements |

| Electrolyte salts | Spectroelectrochemical studies | Tetraalkylammonium salts for non-aqueous electrochemistry |

| Temperature-controlled cells | Temperature-dependent studies | Probe mechanism switching with temperature |

Mechanism Visualization

Diagram 1: ESIPT and PCET Photocycles. The diagram illustrates the competing ESIPT (blue) and PCET (red) pathways in integrated molecular systems. ESIPT follows a four-stage cycle with large Stokes shift emission, while PCET provides a wavelength-dependent alternative pathway.

Diagram 2: ESIPT Troubleshooting Decision Tree. This flowchart provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and addressing common issues with ESIPT activity in molecular systems, based on structural and environmental factors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a photochemical action plot and how does it differ from a traditional absorption spectrum?

A photochemical action plot is an advanced scientific tool that maps the efficiency of a photochemical reaction as a function of the irradiation wavelength. Critically, it is generated by exposing identical reaction aliquots to the same number of photons at varying, highly monochromatic wavelengths and then measuring the conversion or reaction yield at each point [16]. This differs fundamentally from a simple absorption spectrum (which only shows which wavelengths are absorbed) by revealing which wavelengths actually drive the reaction most efficiently. A key finding in modern photochemistry is that the absorption maximum of a molecule often poorly correlates with its maximum photoreactivity; action plots frequently reveal reactivity maxima in spectral regions where absorptivity is very low [16] [17] [18].

Q2: Why is the mismatch between absorption and reactivity so critical for experimental design?

The mismatch between a molecule's absorption spectrum and its photochemical action plot has profound practical consequences [16]. Relying solely on the absorption spectrum to choose an irradiation wavelength can lead researchers to use a highly suboptimal light source, resulting in low conversion, long reaction times, and potential formation of unwanted side-products. The action plot directly identifies the most effective wavelength to maximize yield and selectivity, moving beyond the outdated paradigm that absorption spectra are a reliable guide for photoreactivity [16] [19]. This is especially important for complex systems with multiple chromophores or when designing orthogonal reactions [17].

Q3: What are the essential components of a setup for recording a photochemical action plot?

The core requirement is a wavelength-tunable, monochromatic light source—such as an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) laser system—capable of delivering a stable and known number of photons at each wavelength across the range of interest [16] [18]. The reaction mixture is divided into aliquots, and each is irradiated independently at a specific wavelength. Conversion or yield is then quantified using analytical techniques such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [17] [18], UV-Vis absorption [17], or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [17]. Reproducibility requires meticulous control over the photon flux and reaction conditions for every aliquot [16] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Correlation Between Absorption and Reactivity

- Problem: The reaction proceeds efficiently at wavelengths where the chromophore's absorption is weak, or poorly at its absorption maximum.

- Solution: This is a common finding, not necessarily an error. It indicates that the excited state populated at the absorption maximum may decay through non-productive pathways (e.g., fluorescence, internal conversion), while light absorbed into a different, less accessible state leads to higher reaction quantum yields [16]. Do not assume the experiment has failed. Instead, use the action plot to guide all future experiments, as it reveals the true wavelength-dependent reactivity [16] [17].

Low Conversion Across All Wavelengths

- Problem: The action plot shows minimal to no conversion, regardless of the wavelength used.

- Solution:

- Verify Photon Dosage: Confirm that the photon flux is being accurately measured and is consistent across wavelengths. Use a calibrated power meter at each wavelength [6].

- Check for Competing Absorbers: Ensure that other components in the reaction mixture (solvents, substrates, products) are not absorbing the incident light and acting as an internal filter, thereby shielding the photoreactive chromophore [6]. Measure the absorbance of the entire reaction mixture.

- Confirm Analytical Sensitivity: Verify that your analytical method (e.g., NMR, LC-MS) is sensitive enough to detect low levels of conversion, especially when probing wavelengths with inherently low quantum yields [17].

Irreproducible Results Between Aliquots

- Problem: Significant variation in conversion is observed between replicate aliquots irradiated at the same wavelength.

- Solution:

- Standardize Sample Preparation: Prepare a single, large master batch of the reaction mixture and aliquot it carefully to ensure identical composition and concentration in every sample [17].

- Control Geometry and Environment: Use a custom, reproducible setup (e.g., a 3D-printed photoreactor scaffold) to ensure the distance between the light source and the sample vial, as well as the illumination geometry, is identical for every experiment [6]. Control temperature, as it can affect LED output and reaction rates.

- Account for Vessel Absorption: Remember that the reaction vessel (e.g., glass vial) has a wavelength-dependent transmittance, which can dramatically decrease in the UV range. This must be factored into photon delivery calculations [6].

The following tables consolidate quantitative findings from key studies utilizing photochemical action plots.

Table 1: Documented Mismatches Between Absorption Maxima and Reactivity Maxima

| System / Chromophore | Absorption Maximum (nm) | Reactivity Maximum (from Action Plot) | Observed Discrepancy | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Styrylpyrene derivative | ~350 nm | ~430 nm | ~80 nm bathochromic shift | [16] |

| Coumarin-based photocage | 388 nm | ~405 nm (LED translation) | Reactivity in lower absorptivity region | [17] |

| Perylene-based photocage | 441 nm | ~505 nm (LED translation) | Significant bathochromic shift | [17] |

| MTC/AIBN Polymerization | N/A (Multiple species) | 275 nm & 300-380 nm | Two distinct reactivity bands identified | [18] |

Table 2: Wavelength-Dependent Reaction Quantum Yields (Φ) in a Model Photoenol Ligation

| Irradiation Wavelength (nm) | Reaction Quantum Yield (Φ) | Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 307 | 0.115 ± 0.023 | Local maximum | [6] |

| 345 - 400 | 0.028 ± 0.0037 | Plateau region | [6] |

| 420 | 0.0026 ± 0.0010 | Low, but non-zero reactivity at long wavelength | [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol for Recording a Photochemical Action Plot

This protocol outlines the general methodology for generating a photochemical action plot, based on established procedures [16] [17] [18].

- Master Solution Preparation: Dissolve the photoreactive compound(s) in a suitable solvent to create a single, homogeneous master mixture. This ensures consistent concentration across all aliquots.

- Aliquot Distribution: Precisely distribute equal volumes of the master solution into multiple identical reaction vials. The number of vials depends on the desired wavelength resolution (e.g., 10 nm increments over a 250 nm range requires 25 vials).

- Monochromatic Irradiation: Using a wavelength-tunable laser system, irradiate each vial one at a time with a strictly defined and consistent number of photons at its specific monochromatic wavelength. The order of wavelengths should be randomized to avoid systematic errors.

- Reaction Quenching & Analysis: After irradiation, quench the reaction if necessary (e.g., by placing in darkness). Analyze each sample using a quantitative analytical technique. NMR spectroscopy is commonly used to measure conversion by tracking the disappearance of starting material or emergence of product signals [17] [18].

- Data Compilation & Plotting: For each wavelength, plot the measured conversion (or another metric of efficiency, like product yield) against the irradiation wavelength. This is the photochemical action plot. Superimposing the absorption spectrum of the chromophore provides a direct visual comparison.

Protocol for Validating Action Plots with LEDs

Once an action plot has been recorded with a laser, the identified optimal wavelengths can be translated to more common LED light sources for synthetic applications [6] [17].

- LED Characterization: Measure the emission spectrum and photon flux of the commercially available LED you intend to use. This is crucial for reproducibility.

- Reactor Setup: Place the reaction mixture in a reproducible setup, such as a 3D-printed photoreactor that holds the vial at a fixed distance from the LED [6].

- Irradiation and Monitoring: Irradiate the sample with the LED and monitor the reaction progress over time (e.g., by in-situ NMR or by taking periodic samples for analysis).

- Efficiency Comparison: Compare the conversion rate and final yield achieved with the LED to the predictions from the action plot. This validates the practical utility of the action plot data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photochemical Action Plot Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Laser System (e.g., OPO) | Provides high-power, monochromatic light across a wide wavelength range for the core action plot experiment. | Essential for high-resolution wavelength dependence; the core of the methodology [16] [18]. |

| Precision Photoreactor | Holds sample vials in a fixed, reproducible geometry relative to the light source. | 3D-printed custom scaffolds are a cost-effective and flexible solution that ensure reproducibility [6]. |

| Calibrated Power Meter | Measures the photon flux (number of photons per second) at each wavelength. | Critical for applying an identical photon dose to every sample, as required by the action plot method [16] [6]. |

| NMR Spectrometer | The primary analytical tool for quantifying reaction conversion in many action plot studies. | Provides a direct, quantitative measure of molecular conversion without the need for derivatization [17] [18]. |

| Quartz or UV-Transparent Vials | Serve as the reaction vessel. | Standard glass vials strongly absorb short-wavelength UV light; quartz is necessary for UV-C and UV-B regions [6]. |

| Chemical Actinometer | A reference photochemical system with a known quantum yield, used to validate photon flux measurements. | Provides an internal standard to verify the accuracy of the light dosage calculations. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Photochemical Action Plot Experimental Workflow.

Diagram 2: Conceptual Shift from Absorption to Reactivity.

The fundamental principle of photochemistry is that light acts as a reagent, with its wavelength determining which electronic states in a molecule are activated and thus steering the outcome of a reaction. This wavelength-dependent behavior, whether interstate (populating different electronic states) or intrastate (varying internal energy within the same state), is a powerful tool for controlling product formation. However, it also introduces complexity into experimental design, where factors like light source emission spectra, chromophore absorption, and reaction quantum yields must be precisely managed to achieve reproducible and targeted results. This guide provides troubleshooting support for researchers navigating these challenges within wavelength-dependent photochemical efficiency studies.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my photochemical reaction proceed inefficiently or not at all, even though my chromophore absorbs light at the wavelength I am using?

- A: The reaction quantum yield (Φ), which represents the efficiency of a photochemical process, is often strongly wavelength-dependent. Absorption of light is necessary but not sufficient for a high-yielding reaction. Even if a chromophore absorbs at a given wavelength, the excited state populated may not be the one that leads efficiently to your desired product. For instance, a plateau in the reaction quantum yield versus wavelength plot often indicates that the underlying electronic transition is the main contributor to the reaction in that region. Check the literature or conduct action spectra to determine the optimal wavelength for your specific photochemical transformation [6].

Q2: I am trying to design a system with two orthogonal photoreactions. Why am I seeing cross-talk between the pathways?

- A: Cross-talk occurs when the emission spectrum of your light source significantly overlaps with the absorption spectra of both photoreactive chromophores. Even minor spectral overlaps can lead to the formation of unwanted side products. To achieve λ-orthogonality, you must carefully select chromophores with well-separated absorption bands and pair them with light sources (e.g., LEDs with narrow emission bands) that can selectively excite one chromophore without activating the other. A numerical simulation combining the emission spectra, chromophore absorbance, and known quantum yields can help predict and avoid such cross-talk before running the experiment [6].

Q3: My measured photochemical conversion is lower than predicted by my model. What are the most common experimental parameters I should re-check?

- A: Discrepancies between model and experiment often stem from unaccounted-for experimental losses. Systematically check the following:

- Vessel Transmittance: The transmittance of your reaction vessel (e.g., glass vial) can dramatically decrease, especially in the UV range, and must be factored into light dose calculations [6].

- Photon Flux: Ensure you are accurately measuring the photon flux at the sample position. The geometry and distance between the light source and the sample are critical, and the use of a 3D-printed scaffold can ensure reproducibility [6].

- Competing Absorbers: Verify that your reactants are the only light-absorbing species. The presence of impurities, products, or additives that absorb the incident light will lower the effective photon flux for the desired reaction [6] [20].

Q4: Why does the photodissociation pathway of my molecule change when I use different wavelengths?

- A: This is a classic example of wavelength-dependent photochemistry. Shorter wavelengths (higher energy) can populate higher-lying electronic states that have access to different dissociation channels or overcome larger activation barriers compared to the lowest excited state. For example, CF₃COCl exhibits a C–Cl cleavage pathway above 260 nm, but at higher energies (e.g., 193 nm), a three-body fragmentation pathway becomes dominant as new electronic states are accessed [2]. This is an interstate effect, where populating different states leads to different chemistries.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low/No Conversion | Incorrect wavelength for target chromophore. | Measure absorbance spectrum of chromophore; ensure significant spectral overlap with light source. |

| Light source intensity is too low or not reaching sample. | Calibrate photon flux at sample position; check for obstructions or dirty reaction vessels. | |

| Reaction quantum yield is inherently low at chosen wavelength. | Consult literature for wavelength-Φ relationships; shift to a more efficient excitation wavelength [6]. | |

| Irreproducible Results | Inconsistent lamp alignment or power output. | Use a fixed, 3D-printed reactor scaffold for reproducible geometry; monitor light source power and temperature [6]. |

| Fluctuating pulse width (for pulsed lasers). | Measure pulse width at the sample input, especially after passing through modulation optics [21]. | |

| Unwanted Side Products | Polychromatic source activating multiple chromophores. | Use narrow-band LEDs or filters; model emission and absorbance spectra to identify and mitigate cross-talk [6]. |

| Secondary photochemistry of the primary product. | Monitor reaction progression; optimize irradiation time to maximize yield before secondary reactions occur. | |

| Inaccurate Modeling | Ignoring wavelength dependence of quantum yield. | Use a functional form (e.g., Weibull function) for Φ(λ) in simulations instead of a single average value [20]. |

| Neglecting absorption by reactants or products. | Incorporate the wavelength-dependent absorbance of all light-absorbing species into the kinetic model using the Beer-Lambert law [6]. |

Quantitative Data and Protocols

Wavelength-Dependent Photochemical Data

Table 1: Measured Wavelength-Dependent Reaction Quantum Yields for a Model Photoenol Ligation [6].

| Wavelength (nm) | Reaction Quantum Yield (Φ) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 307 | 0.115 ± 0.023 | Peak efficiency, likely π→π* transition dominance. |

| 345 - 400 | ~0.028 ± 0.004 | Plateau region, efficient photochemistry. |

| 420 | 0.0026 ± 0.0010 | Greatly reduced efficiency at the absorption tail. |

Table 2: Wavelength-Dependent Scattering Properties of Biological Tissues Relevant to SHG Imaging [21].

| Tissue Type | Wavelength (nm) | Scattering Coefficient, μs (cm⁻¹) | Anisotropy (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat Tail Tendon | 780 | 240 ± 10 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| 890 | 250 ± 20 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | |

| 1070 | 220 ± 20 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | |

| Human Ovary | 890 | 220 ± 20 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| 1070 | 210 ± 24 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

Standard Protocol: Determining Wavelength-Dependent Reaction Quantum Yield

Objective: To accurately measure the reaction quantum yield (Φλ) for a photochemical reaction as a function of excitation wavelength.

Principles: The Stark-Einstein law states that each photon absorbed causes one primary photochemical event. The quantum yield is the ratio of the number of product molecules formed to the number of photons absorbed by the reactant.

Materials:

- Tunable laser system or set of monochromatic LEDs.

- Precision photoreactor (e.g., 3D-printed scaffold for fixed geometry).

- Spectrometer or calibrated power meter.

- Analytical tool for product quantification (e.g., HPLC, GC, NMR).

Procedure:

- Reactor Characterization: For each light source/wavelength, measure the emission spectrum and the spectral photon flux density (p°(λ)) at the sample position using the power meter and spectrometer. Measure the transmittance of the reaction vessel [6].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution of your photoreactive chromophore at a known concentration. Ensure the solution is homogeneous and free of light-scattering particles.

- Irradiation: Place the sample in the reactor and irradiate for a measured time. Maintain constant temperature and ensure efficient mixing if needed.

- Quantification: Analyze the reaction mixture to determine the number of product molecules formed (e.g., via concentration measurement).

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance (A(λ)) of the chromophore at the irradiation wavelength(s) to determine the fraction of light absorbed, [1 - 10^(-A(λ))].

- Calculation: Calculate the quantum yield using a wavelength-resolved approach. The rate of product formation (R) is given by:

R = ∫ p°(λ) * Φ(λ) * [1 - 10^(-A(λ))] dλUse this equation to solve for Φ(λ) at each wavelength by using monochromatic sources or by fitting the data with a presumed function (e.g., Weibull function) for polychromatic deconvolution [6] [20]. - Replication: Perform all measurements in triplicate to ensure statistical significance.

Advanced Protocol: Probing Wavelength-Dependent Photodissociation Dynamics

Objective: To correlate photofragment identity and kinetic energy with excitation wavelength to unravel competing dissociation pathways.

Principles: Different electronic states, populated by different wavelengths, can lead to distinct photofragments with characteristic kinetic energy distributions (KEDs), measurable via velocity map imaging (VMI) [2].

Materials:

- Tunable nanosecond pulsed laser (photolysis laser).

- Second tunable laser for Resonance-Enhanced Multi-Photon Ionization (REMPI) of fragments.

- Velocity Map Imaging (VMI) spectrometer with a time-of-flight mass spectrometer and detector.

- Molecular beam source for gas-phase sample delivery.

Procedure:

- Molecular Beam Generation: Introduce the sample (e.g., CF₃COCl), seeded in an inert gas, into a vacuum chamber via a pulsed nozzle to create a cold, collisionless molecular beam.

- Photodissociation: Cross the molecular beam with the photolysis laser pulse at a specific wavelength (e.g., 235 nm, 254 nm, 280 nm).

- Fragment Ionization: After a short delay, ionize a specific photofragment (e.g., Cl atoms, CO) using the REMPI laser, which is tuned to a specific transition of the target fragment.

- Image Acquisition: The VMI spectrometer projects the velocity vectors of the ions onto a 2D detector. Record the resulting 2D image.

- Data Reconstruction: Use an inverse Abel transformation to reconstruct the original 3D velocity distribution from the 2D image.

- Analysis: Extract the kinetic energy distribution (KED) and angular distribution (anisotropy parameter, β) of the fragments from the reconstructed image.

- Wavelength Dependence: Repeat steps 2-6 at different photolysis wavelengths. Changes in the KEDs and branching ratios between fragments (e.g., Cl vs. CO) directly reveal the activation of different dissociation pathways (interstate) or the influence of excess energy (intrastate) [2].

Essential Visualizations

Conceptual Workflow for Troubleshooting

This diagram outlines a systematic approach for diagnosing issues in wavelength-dependent photochemistry experiments.

Workflow for troubleshooting photochemical experiments.

Mechanism of Wavelength-Dependent Selectivity

This diagram illustrates the mechanistic basis for how different wavelengths select different reaction pathways, using CF₃COCl as an example [2].

Wavelength-selective photodissociation pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Wavelength-Dependent Studies.

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow-Band LEDs | Precision light source for selective excitation and λ-orthogonal systems. | Ensure emission spectrum has minimal overlap with non-target chromophores [6]. |

| Tunable OPO Laser | High-intensity, wavelength-tunable source for action spectroscopy and dynamics. | Monitor pulse width and power after modulation optics; can be cost-prohibitive [21]. |

| 3D-Printed Reactor | Ensures fixed, reproducible geometry between light source and sample. | Critical for reproducible photon dose delivery and accurate kinetic modeling [6]. |

| Calibrated Spectrometer | Measures emission spectra of light sources and absorbance of reaction mixtures. | Necessary for applying Beer-Lambert law and calculating absorbed photon flux [6]. |

| o-Methylbenzaldehydes | Model chromophores for studying photoenolization/Diels-Alder ligation kinetics. | Their reaction quantum yield Φ is strongly wavelength-dependent, making them excellent for method development [6]. |

| Au(III) Organometallic Reagents | For site-specific arylation of cysteine residues in peptides/proteins. | The attached aryl group acts as a chromophore, enabling UV photodissociation at 266 nm for top-down mass spectrometry [22]. |

| Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) | A natural chromophore for studying environmental photochemistry. | Its quantum yields for producing reactive transients (³CDOM*, •OH) decrease with increasing wavelength, modeled by a Weibull function [20]. |

Influence of Molecular Structure and Environment on Absorption and Quantum Yield

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Photochemical Efficiency

FAQ 1: My photochemical reaction has a very low quantum yield (Φ << 1). What are the most common causes and solutions?

A low quantum yield indicates that most absorbed photons do not lead to your desired product. This is often due to competing processes or suboptimal reaction conditions.

- Potential Cause: Competing deactivation pathways of the excited state, such as fluorescence, phosphorescence, internal conversion, or intersystem crossing, are outcompeting the desired reaction pathway [23].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check for Quenchers: Identify if any species in the solution (e.g., oxygen, solvents, or impurities) can deactivate the excited state. Consider degassing the solution to remove oxygen.

- Modify Molecular Structure: Introduce substituents that favor the reaction pathway. For instance, extending conjugation can increase the excited state lifetime, raising the probability of reaction [23].

- Optimize Concentration: High concentrations can lead to self-quenching, where excited molecules are deactivated by collisions with ground-state molecules. Diluting the solution may improve Φ [23] [24].

FAQ 2: Why does my quantum yield change when I use different wavelengths of light?

The quantum yield (Φ) is often wavelength-dependent because different wavelengths can populate different excited states, which may have distinct reactivities [6].

- Potential Cause: Excitation into higher vibrational levels or different electronic states (e.g., π→π* vs. n→π*) can lead to variations in photochemical efficiency. A plateau in Φ across a wavelength range often indicates excitation into the same electronic state [6].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Create an Action Plot: Do not rely solely on the absorption spectrum. Measure the quantum yield at several specific wavelengths to create a "photochemical action plot," which directly shows the most effective wavelengths for your reaction [6].

- Control Wavelength Precisely: Use narrow-band light sources like LEDs or lasers instead of broadband lamps for critical measurements to ensure reproducibility and accurate interpretation [24] [6].

FAQ 3: How does the solvent or pH environment influence my photochemical measurements?

The environment directly affects the energy and stability of the excited states and can alter the protonation state of the chromophore [23] [24].

- Potential Cause: Solvent polarity can stabilize or destabilize excited states, changing their energy and reactivity. pH can alter the molecular structure of the chromophore, which can dramatically shift its absorption spectrum and excited-state reactivity [23] [24].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Systematic Solvent Screening: Test a series of solvents with varying polarity (e.g., from hexane to acetone) to map the solvent effect on your reaction's quantum yield [23].

- Buffer Your Solution: For pH-sensitive molecules (like phenolic carbonyls), use buffered solutions to maintain a constant and relevant pH. For example, studies of brown carbon in acidic aerosol use pH = 2 to mimic environmental conditions [24].

FAQ 4: My measured quantum yield is greater than 1 (Φ > 1). Is this possible, and what does it mean?

Yes, a quantum yield above 1 is a clear indicator of a chain reaction mechanism [23] [25].

- Potential Cause: The initial photochemical step generates a highly reactive intermediate (e.g., a radical) that propagates a chain reaction, causing multiple product molecules to form from a single absorbed photon [25].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Measurement Accuracy: Verify your actinometry and product quantification methods to rule out experimental error.

- Investigate Mechanism: Look for evidence of radical intermediates or chain-propagation steps. The photochemical reaction between H₂ and Cl₂, for example, has a very high quantum yield for this reason [25].

FAQ 5: How does molecular architecture, like linker length in a macromolecule, affect the quantum yield of an intramolecular reaction?

The spatial arrangement of functional groups creates a "Goldilocks zone" for reactivity, balancing steric and entropic factors [26].

- Potential Cause: If reactive groups are too close, steric hindrance prevents optimal alignment for reaction. If they are too far apart, the probability of them encountering each other within the excited state lifetime decreases significantly [26].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Design Flexible Linkers: In synthetic design, incorporate linker molecules (e.g., caprolactone oligomers) of varying lengths to find the optimal distance that maximizes the quantum yield of intramolecular cyclization [26].

| Compound | Abbreviation | Maximum Quantum Yield Range (%) | Key Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coniferaldehyde | CA | 0.05 - 2 | Propenyl substituent |

| 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | 4-HBA | 0.05 - 2 | No ring substituents |

| 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethylbenzaldehyde | DMBA | 0.05 - 2 | Methyl substituents |

| Isovanillin | iVAN | 0.05 - 2 | Methoxy group meta to aldehyde |

| Vanillin | VAN | 0.05 - 2 | Methoxy group ortho to aldehyde |

| Syringaldehyde | SYR | 0.05 - 2 | Two methoxy groups |

Note: Quantum yields for these compounds are concentration-dependent due to a self-reaction mechanism involving the triplet excited state [24].

| Factor | Impact on Quantum Yield (Φ) | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increased temperature can enhance reaction rates but may also accelerate competing deactivation processes. | Systematically study Φ across a temperature range to find the optimum. |

| Concentration | High concentration can cause self-quenching, lowering Φ. | Measure concentration dependence and work in a diluted regime if self-quenching is observed. |

| Light Intensity | Very high intensities can lead to effects like excited-state absorption (photoquenching), reducing the apparent Φ [27]. | Use lower light intensities or extrapolate measurements to zero intensity. |

| Oxygen | Acts as a potent quencher of triplet excited states. | Degas solutions via freeze-pump-thaw cycles or sparging with an inert gas (e.g., N₂). |

| Molecular Substituents | Electron-donating/withdrawing groups and extended conjugation can drastically alter excited state lifetime and reactivity. | Perform computational chemistry studies or refer to structure-property databases to guide molecular design [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Wavelength-Resolved Quantum Yields using UV-LEDs

This protocol is adapted from methods used to study phenolic carbonyls and allows for direct comparison with atmospheric actinic fluxes [24].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of your chromophore in the desired solvent and pH buffer. For the phenolic carbonyl study, a stock solution in acetonitrile was diluted with acidic water (pH=2) to the final concentration [24].

- Light Source Characterization:

- Use a set of narrow-band UV-LEDs (e.g., 295–400 nm).

- Connect LEDs to a stable DC power supply.

- Characterize the spectral output and photon flux of each LED using a chemical actinometer.

- Photon Flux Measurement with Actinometry:

- Use a 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (2-NBA) solution as an actinometer, which has a known, constant quantum yield (Φ = 0.43) between 300–400 nm [24].

- Illuminate the 2-NBA solution and monitor the formation of 2-nitrosobenzoic acid using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Calculate the photon flux based on the known quantum yield and the measured reaction rate.

- Photolysis Experiment:

- Illuminate your prepared solution with a characterized LED.

- Take samples at 6-7 timepoints over the course of the reaction.

- Analysis:

- Analyze sample concentrations using HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Calculate the quantum yield (Φloss) for the loss of the starting material using the formula [24]:

j = ∫Φ_loss(λ) · I₀(λ) · ε(λ) dλwherejis the measured rate constant,I₀is the incident photon flux, andεis the molar absorptivity.

Protocol 2: Investigating Molecular Architecture Effects on Intramolecular Quantum Yield

This protocol outlines the procedure for measuring the quantum yield of intramolecular cyclization in monodisperse macromolecules [26].

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the trifunctional macromolecule (e.g., with pyrene-chalcone reactive units) in a spectroscopically suitable solvent like acetonitrile at a low concentration (e.g., 25 µM) to ensure the reaction is intramolecular [26].

- Irradiation:

- Use a monochromatic, tunable pulsed laser as the light source to ensure precise excitation.

- Simultaneously irradiate the sample and record the UV-Vis absorbance spectrum at regular intervals to monitor the consumption of the starting material.

- Data Fitting:

- Plot the conversion to the cyclized product against the number of photons absorbed.

- Fit the linear section of the curve using the following equation to extract the intramolecular quantum yield (Φc) [26]:

ρ = Δ · Φ_c · N_pwhereρis the conversion,Δis a factor accounting for absorption, andN_pis the number of photons.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Actinometers | Substances with a known quantum yield used to determine the photon flux of a light source. Essential for accurate Φ measurement. | 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde (2-NBA) for UV-LEDs (300-400 nm); Uranyl oxalate for broader UV studies [24] [25]. |

| Narrow-Band UV-LEDs | Light sources with a well-defined emission peak. Enable wavelength-resolved quantum yield studies. | Studying the wavelength dependence of phenolic carbonyl photolysis [24]. |

| 3D-Printed Photoreactor | Ensures reproducible geometry between the light source and sample vial, critical for reproducible light dose delivery. | Custom, cost-effective reactors for precision photochemistry experiments [6]. |

| HPLC with UV Detector | Used to separate and quantify reaction components from a complex mixture over time. | Monitoring the decomposition of an actinometer or the consumption of a photochemical reactant [24]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Pathway to Optimize Quantum Yield

Diagram 2: Molecular & Environmental Factors

Advanced Measurement and Strategic Application in Drug Development

Building an accurate wavelength-resolved reactivity profile is fundamental for advancing research in photochemistry and photopharmacology. This process requires precise measurement of how a compound's photochemical efficiency varies across different wavelengths of light. The critical parameter governing this relationship is the reaction quantum yield (Φλ), which represents the efficiency at which photons of a specific wavelength drive a photochemical transformation [6]. This profile is essential for predicting reaction outcomes under various light sources and is particularly valuable for designing wavelength-selective or λ-orthogonal chemical systems [6].

Several foundational laws of photochemistry guide this experimental work. The Grotthus-Draper law establishes that a photochemical reaction can only occur if light is absorbed by the substrate. The Beer-Lambert law governs light absorption by the chromophore, while the Stark-Einstein law (photo-equivalence law) states that each photon absorbed causes exactly one primary photochemical event [6]. Understanding these principles is crucial for designing robust experiments and correctly interpreting wavelength-resolved data.

Essential Experimental Parameters and Measurement

Accurately constructing a reactivity profile requires meticulous measurement of several interconnected parameters. The following workflow outlines the key steps in this characterization process:

Quantitative Parameters Table

The table below summarizes the core parameters that must be experimentally determined to build a reliable reactivity profile:

| Parameter | Symbol | Measurement Technique | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molar Absorptivity | ε(λ) | UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Determines fraction of light absorbed at each wavelength [6] |

| Reaction Quantum Yield | Φ(λ) | Actinometry with calibrated light source | Primary measure of photochemical efficiency [6] [29] |

| Photon Flux | I₀(λ) | Chemical actinometry or calibrated radiometer | Quantifies photons delivered to reaction [6] [29] |

| Optical Path Length | l | Precise vessel measurement | Critical for Beer-Lambert calculations [29] |

| Vessel Transmittance | T(λ) | Spectrophotometry with empty vessel | Accounts for wavelength-dependent light loss [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Determining Wavelength-Resolved Quantum Yields

The quantum yield (Φλ) is the most critical parameter for building a reactivity profile. The following protocol, adapted from studies on vanillin photochemistry and precision photochemistry, provides a robust methodology [29]:

Materials and Equipment:

- Narrow-bandwidth light sources (UV-LEDs or lasers covering relevant wavelength range)

- Quartz reaction vessels (consistent path length)

- Chemical actinometer (e.g., 2-nitrobenzaldehyde for 300-400 nm range)

- Analytical instrument (HPLC or UV-Vis spectrophotometer)

- Precision power supply for LEDs

- Temperature control system (23±2°C recommended)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Light Source Characterization: Precisely measure the emission spectrum and photon flux of each LED using a calibrated spectrometer. For photon flux quantification, use 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (NBA) actinometry, which has a known constant quantum yield (Φ=0.43) between 300-400 nm [29].

Sample Preparation: Prepare reactant solutions at concentrations that ensure absorbance remains below 0.2 to minimize internal screening effects. For vanillin, concentrations ≤25 μM were effective in a 0.88 cm pathlength vessel [29].

Irradiation Experiments: Illuminate samples in quartz vials, controlling current and temperature to maintain consistent LED output. Use fresh solution for each time point or limit aliquot removal to ≤10% total volume to maintain consistent conditions [29].

Reaction Monitoring: Quantify reactant depletion and product formation using appropriate analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis spectroscopy). Monitor conversion over at least 3 reaction lifetimes for reliable kinetics [29].

Quantum Yield Calculation: Calculate Φλ using the measured photolysis rate and the absorbed photon flux, correcting for vessel transmittance and spectral distribution [6] [29].

Accounting for Environmental Factors

Photochemical efficiency can be significantly influenced by reaction environment. When building reactivity profiles, consider these factors:

Ionic Strength: Studies show vanillin photochemical loss rates can double at high ionic strength (up to 4M), approaching conditions found in atmospheric aerosols [29].

Oxygen Concentration: Dissolved oxygen can quench excited states and generate reactive species that alter reaction pathways [29].

pH Effects: Acid-base equilibria of excited states may differ significantly from ground state pKa values, particularly for phenolic carbonyls [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow-band UV-LEDs | Precision wavelength selection | Violumas LEDs (295, 310, 325, 340, 365, 375, 385 nm) effectively cover photochemically active range [29] |

| 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde (NBA) | Chemical actinometer | Quantum yield Φ=0.43 constant between 300-400 nm; ideal for calibration [29] |

| Quartz Reaction Vessels | Housing reactions with minimal UV attenuation | Superior transmittance in UV range; pathlength must be precisely measured [6] |

| 3D-Printed Photoreactor | Reproducible irradiation geometry | Custom designs ensure consistent LED-sample distance; eliminates inverse-square law variability [6] |

| TrueBlack Background Suppressors | Reduce autofluorescence | Particularly important for blue fluorescent dyes in imaging applications [30] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my measured quantum yield inconsistent between wavelengths?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Stray Light in Spectrophotometer: Heterochromatic stray light, especially at ends of spectral ranges, can cause significant measurement errors. Test using appropriate cutoff filters and ensure instrument calibration [31].

Incorrect Wavelength Calibration: Verify spectrophotometer wavelength accuracy using holmium oxide solution or emission lines from deuterium lamps. Even minor wavelength shifts dramatically affect measured absorptivity [31].

Bandwidth Effects: Wider monochromator bandwidths can blur sharp spectral features. Use bandwidth <5 nm for compounds with narrow absorption bands [31].

Internal Filtering: High reactant concentrations cause preferential absorption at vessel surface. Maintain absorbance <0.2 throughout experiments to ensure uniform illumination [29].

FAQ 2: How can I minimize background interference in photochemical measurements?

Recommended Approaches:

Control Autofluorescence: Cellular and tissue autofluorescence is highest in blue wavelengths. Avoid blue fluorescent dyes (CF350, CF405S) for low-expression targets and consider specialized quenchers like TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quenchers [30].

Purify Reagents: Fluorescence-grade solvents significantly reduce background. Testing shows laboratory HPLC-grade and commercial LC-MS-grade water provide superior backgrounds compared to deionized water [32].

Optimize Antibody Concentrations: For fluorescent labeling, titrate primary and secondary antibodies to find optimal concentrations that maximize signal-to-noise [30].

Implementation Strategy:

Develop Numerical Simulation: Create a wavelength-resolved model that incorporates LED emission spectra, vessel transmittance, molar absorptivity of all species, and wavelength-dependent quantum yields [6].

Validate with Experimental Data: Compare predictions against actual conversions at multiple wavelengths. Research shows excellent agreement between simulated and experimental results for photoenol ligation reactions [6].

Account for Competing Absorbers: Include absorbance of both reactants and products in models, as photoproducts can act as internal filters during later reaction stages [6].

Advanced Applications and System Design

Designing λ-Orthogonal Ligation Systems

Wavelength-resolved reactivity profiles enable the design of sophisticated photochemical systems where multiple reactions can be selectively activated by different light colors. The following diagram illustrates this advanced application:

This approach has been successfully demonstrated with substituted o-methylbenzaldehydes, where algorithms assessing competing photoreactions enabled design of selective ligation systems controlled solely by irradiation wavelength [6].

Environmental Factor Integration

Advanced reactivity profiles should incorporate environmental dependencies:

Salt Effects: Measure Φλ at varying ionic strengths (0-4M) using salts like Na₂SO₄ and NaCl to simulate biological or aerosol conditions [29].

Oxygen Manipulation: Compare aerobic and anaerobic conditions to quantify oxygen quenching effects on excited states [29].

pH Profiling: Determine Φλ across physiologically relevant pH ranges, particularly for compounds with ionizable groups that may alter excited state behavior [29].

Building comprehensive wavelength-resolved reactivity profiles requires meticulous attention to experimental parameters, environmental conditions, and instrumental accuracy. By implementing these best practices and troubleshooting strategies, researchers can generate reliable data that enables predictive photochemistry and advanced wavelength-selective applications in drug development and materials science.

Spectroelectrochemistry and Transient Absorption for Mechanistic Insights

Fundamental Concepts and FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the core principle of spectroelectrochemistry (SEC), and why is it powerful for mechanistic studies?

Spectroelectrochemistry (SEC) is a hyphenated technique that combines electrochemical manipulation with simultaneous spectroscopic monitoring. Its core principle is based on analyzing the interaction between a beam of electromagnetic radiation and the compounds involved in electrochemical reactions, providing both an optical and an electrochemical signal from a single, simultaneous experiment [33]. This makes it powerful for mechanistic studies because it offers an "autovalidated" character, confirming results via two independent routes and providing direct access to kinetic data, qualitative information on the interface state at electrochemical conditions, and the ability to identify short-lived intermediates and reactive species generated electrochemically [33] [34] [35].

FAQ 2: How can Transient Absorption Spectroelectrochemistry (TA-SEC) uncover early-stage photodynamics of reactive intermediates?

TA-SEC extends the capabilities of conventional SEC into the ultrafast time domain. It allows researchers to generate reactive intermediates electrochemically—through controlled oxidation or reduction of a stable starting species—and then immediately probe their early-stage photoinduced relaxation mechanisms on femtosecond to nanosecond timescales [34]. This approach is superior to using strong chemical oxidants or reductants, as it provides a "green" method for creating intermediates continuously without complicating the spectroscopic analysis with excess reagents. For example, this method has been used to unravel the distinct relaxation pathways of anthraquinone-2-sulfonate (AQS) and its electrochemically generated, less-stable counterpart, anthrahydroquinone-2-sulfonate (AH2QS) [34].

FAQ 3: Why is the irradiation wavelength critical in photochemical experiments, and how does it affect reaction outcomes?

The irradiation wavelength is critical due to the Grotthus-Draper law (the first law of photochemistry), which states that a photochemical reaction can only proceed if light is absorbed by the substrate [36]. The wavelength dictates which electronic transitions are excited, which can directly influence the reaction quantum yield and the resulting products [37] [36]. Wavelength selectivity can manifest in several ways:

- It may activate different chromophores within a single molecule [38].

- It can induce the population of different reactive excited states, leading to divergent reaction pathways [38].

- It can sequentially populate the excited state of a starting compound and the excited state of a photogenerated intermediate, each with different reactivity [38]. Furthermore, the wavelength influences practical aspects like penetration depth; longer wavelengths typically allow for curing thicker layers in polymerization applications [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Low Signal-to-Noise in UV-Vis SEC Measurements

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background noise in optical signal. | Stray light or improper background correction. | Ensure the cell is properly positioned and take a new background spectrum after applying the potential to account for the new chemical environment. |

| Weak analyte signal. | Path length is too short or concentration is too low. | For transmission measurements, optimize the thin-layer cell path length. The required concentration for adequate spectroscopy can be up to 0.05 mol dm⁻³, which is higher than typical CV measurements [35]. |

| Unstable electrochemical baseline. | Unsuitable electrode material or high resistance in the thin-layer cell. | Use electrodes with good optical and electrochemical properties, like Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) meshes, which offer low background currents and minimize light scattering [34]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Inconsistent Photochemical Reactivity

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor conversion or unexpected side products. | Mismatch between the LED emission spectrum and the photoinitiator's absorption profile. | Precisely characterize the LED's emission spectrum and the chromophore's absorbance. Remember that LEDs are not monochromatic and can have bandwidths up to 100 nm, potentially exciting unintended absorbers [37] [36]. |

| Reaction efficiency varies between experiments. | Fluctuations in light intensity or inaccurate dosimetry. | Use a 3D-printed photoreactor scaffold to fix the distance between the LED and sample vial, ensuring reproducible geometry. Use a calibrated power meter to determine the precise light dose reaching the sample [36]. |

| Low penetration depth in photopolymerization. | Photoinitiator with excessively high absorbance at the used wavelength. | Select a photoinitiator with lower molar attenuation at the target wavelength. For example, tetrakis(2-methylbenzoyl)germane, with its weaker absorption in the blue-green range, allows for greater penetration depth compared to Ivocerin [37]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Mesh Electrode for TA-SEC

Objective: To create a robust, free-standing BDD mesh working electrode that minimizes light scattering and enables high-quality ultrafast TA-SEC measurements [34].

Materials:

- Freestanding, highly doped polycrystalline BDD (~3×10²⁰ boron atoms cm⁻³, 0.25 mm thickness).

- Nd:YAG laser micromachining system (355 nm).

- Concentrated H₂SO₄, KNO₃.

- Sputtering system for metal contacts (Ti/Au).

- Conductive epoxy and waterproofing epoxy resin.

Methodology:

- Laser Cutting: Laser-cut the BDD into a mesh electrode (e.g., 6 x 7 mm) with small holes (e.g., 0.25 mm diameter) and a center-to-center spacing of 0.35 mm. Use a fluence of 350 J cm⁻² in two passes.

- Acid Cleaning: Clean the laser-cut electrode in concentrated H₂SO₄ saturated with KNO₃ at ~200 °C for 30 minutes. Rinse with water, then clean again in concentrated H₂SO₄ at ~200 °C for 30 minutes to remove laser debris.

- Annealing: Anneal the electrode in air at 600 °C for 5 hours to significantly reduce any residual sp²-bonded carbon from the laser process.

- Ohmic Contact: Sputter a Ti (10 nm)/Au (400 nm) contact onto the tail of the electrode. Anneal in air at 400 °C for 5 hours to create an ohmic contact.

- Connection: Connect the BDD electrode to a copper wire using conductive silver epoxy. Waterproof the connection with a layer of epoxy resin.

Protocol 2: Determining Wavelength-Dependent Quantum Yield

Objective: To quantitatively map the reaction quantum yield (Φλ, c) of a photochemical reaction as a function of wavelength and concentration, enabling the prediction of photokinetic behavior under LED irradiation [36].

Materials:

- Tunable laser system or set of narrow-bandwidth LEDs.

- 3D-printed precision photoreactor with fixed geometry.

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- Calibrated power meter.

Methodology:

- System Characterization: Precisely measure the emission spectrum of each light source and the transmittance of the reaction vessel (e.g., glass vial) across the wavelength range of interest.

- Absorbance Measurement: Record the UV-Vis spectra of the reactant(s) and product(s) to determine their molar attenuation coefficients (ελ).

- Photolysis Experiments: Irigate the reactant solution at each target wavelength using the precision photoreactor. Monitor the reaction progress over time using UV-Vis spectroscopy or another suitable analytical method.

- Quantum Yield Calculation: For each wavelength, calculate the reaction quantum yield using the following relationship, which incorporates the principles of the Bunsen-Roscoe and Stark-Einstein laws [36]: Φλ = (Number of molecules reacted) / (Number of photons absorbed) This requires accurate measurement of the incident light intensity and the fraction absorbed by the reactant.

- Numerical Simulation: Use the acquired wavelength-dependent quantum yield data, along with the emission spectra and absorbance data, in a numerical simulation to predict the time-dependent conversion of the reaction under broader-spectrum LED light sources.

Table 1: Wavelength-Dependent Photochemical Efficiency of Acylgermane Photoinitiators [37] This table summarizes key data for three germanium-based photoinitiators, highlighting how structural changes affect performance across wavelengths.