Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Synthesis of Photocatalytic Materials: A Comprehensive Guide for Advanced Applications

This article provides a systematic comparison of top-down and bottom-up synthesis approaches for developing advanced photocatalytic materials.

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Synthesis of Photocatalytic Materials: A Comprehensive Guide for Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of top-down and bottom-up synthesis approaches for developing advanced photocatalytic materials. It explores the fundamental principles, mechanistic insights, and practical methodologies for both strategies, addressing key challenges in scalability, defect control, and performance optimization. By examining current applications in energy conversion, environmental remediation, and organic synthesis, alongside rigorous validation techniques, this review serves as an essential resource for researchers and scientists seeking to select and optimize synthesis routes for specific photocatalytic applications, including those relevant to pharmaceutical development.

Understanding Synthesis Pathways: Core Principles of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches

In the pursuit of advanced materials for critical applications like photocatalysis, the pathway chosen to create these materials fundamentally dictates their final properties and performance. The synthesis of nanoscale materials is primarily governed by two contrasting philosophies: the top-down approach, which involves scaling down bulk materials into nanostructures, and the bottom-up approach, which constructs nanomaterials from atomic or molecular precursors [1]. These methodologies differ profoundly in their principles, techniques, and the characteristics of the resulting products. For researchers and development professionals in fields ranging from energy to medicine, understanding this dichotomy is essential for designing materials with tailored properties. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two synthesis paradigms, focusing on their application in developing photocatalytic materials for solar fuel production, environmental remediation, and other energy applications, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Conceptual Foundations and Synthesis Mechanisms

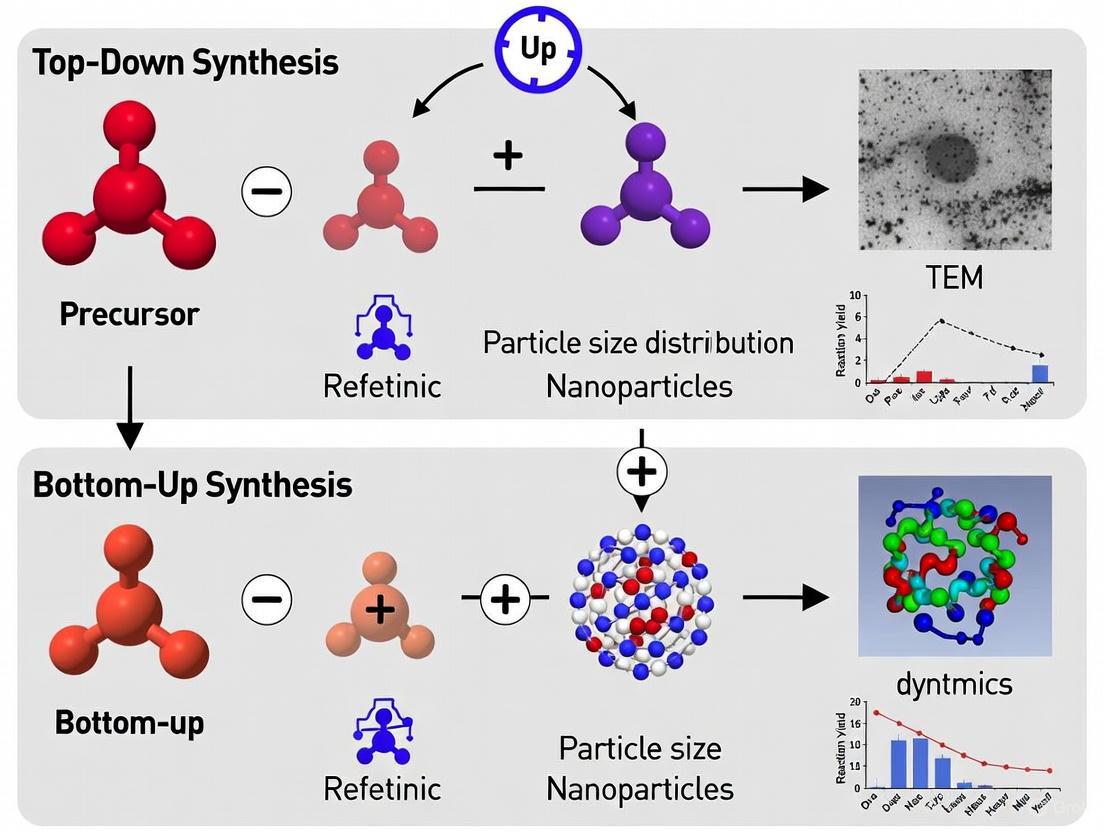

The core distinction between these approaches lies in their starting point and direction of assembly. Top-down synthesis is a subtractive process where bulk materials are physically or chemically broken down into nanoscale structures. Common techniques include ball milling, a mechanical method that uses impact and shear forces to reduce particle size [2] [3], and etching or lithography [1]. Conversely, bottom-up synthesis is an additive process, building nanomaterials atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule. This method often leverages chemical reactions and self-assembly phenomena, where pre-existing components organize into more complex, ordered structures driven by intermolecular forces [1]. Key techniques include sol-gel processes, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and precipitation methods [4] [3].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and key techniques associated with each synthesis paradigm:

Comparative Analysis: Principles, Advantages, and Limitations

The choice between top-down and bottom-up methods significantly impacts the structural characteristics, defect chemistry, and functional performance of the synthesized materials.

Top-down approaches are often valued for their relative simplicity and scalability. However, a major limitation is the potential introduction of surface defects and crystallographic damage during the size-reduction process. These imperfections can sometimes be detrimental but have also been shown to enhance photocatalytic activity by creating active sites for reactions [2]. For instance, ball milling of the lead-free perovskite Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ not only reduced particle size but also generated a high concentration of surface defects, which improved light absorption and provided active sites for photocatalytic CO₂ reduction [2].

In contrast, bottom-up approaches excel in producing materials with precise control over size, shape, and composition. This allows for the engineering of complex architectures like core-shell nanoparticles and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [5] [6]. This precision often results in more uniform crystals and fewer defects, although defects can be intentionally incorporated through "defect engineering" [4]. A key advantage for catalysis is the inherently high specific surface area of bottom-up nanoparticles, which provides a greater density of reactive sites. For example, bottom-up synthesis is ideal for creating two-dimensional porous photocatalysts, which offer shortened charge transport distances, facilitated mass transport, and abundant surface active centers [7].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesis Approaches

| Aspect | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Subtractive: breaking down bulk material [1] | Additive: building from atoms/molecules [1] |

| Process Direction | Macro-to-nano [3] | Nano-to-macro [3] |

| Common Techniques | Ball milling, etching, laser ablation [2] [8] | Sol-gel, precipitation, chemical vapor deposition, self-assembly [4] [3] |

| Control over Size/Shape | Limited precision, broader size distribution [1] | High precision, uniform size and morphology [1] [7] |

| Typical Surface Quality | Potential for surface defects and contamination [2] | Atomically smoother surfaces, controlled defect engineering [4] |

| Scalability & Cost | Often scalable and cost-effective for mass production [1] | Can be complex and costly; may involve expensive precursors [1] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, high production batch capacity [3] | Excellent control over nanostructure and composition [7] |

| Primary Limitation | Introduction of internal stress and surface imperfections [2] | Often requires complex purification and is more time-consuming [1] |

Experimental Performance Data in Photocatalysis

Direct comparative studies and individual performance data highlight how the synthesis method influences photocatalytic efficacy.

Top-Down Performance Data

A prime example of a top-down approach is the synthesis of Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ double-layer perovskite via ball milling [2]. The mechanical treatment served multiple functions: it reduced crystal size, increased the specific surface area by nearly tenfold (from 0.57 m²/g to 5.23 m²/g), and generated beneficial surface defects.

Table 2: Photocatalytic Performance of Top-Down Synthesized Materials

| Material | Synthesis Method | Application | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ Perovskite |

Ball Milling (Top-Down) | CO₂ to CO Reduction | CO Yield (4h, full spectrum) | 72.17 μmol/g (1.6x increase vs. untreated) | [2] |

Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ Perovskite |

Ball Milling (Top-Down) | CO₂ to CO Reduction | CO Yield (4h, NIR light) | 5.37 μmol/g (vs. 2.31 μmol/g untreated) | [2] |

| Pt/C Electrocatalyst | Electrochemical Dispersion (Top-Down) | Ethanol Electrooxidation | Stability | Best stability with largest nanoparticle sizes | [8] |

Bottom-Up Performance Data

Bottom-up synthesis allows for meticulous control, as seen in the creation of amorphous and crystalline lead(II) coordination polymers using sonochemical and hydrothermal methods [5]. These materials were effective in photocatalytic dye degradation. Furthermore, the bottom-up precipitation method is highly effective for producing uniform nanoparticles like barium sulphate (BaSO₄), with size and morphology controlled by adjusting parameters such as capping agents, concentration ratios, and pH [3].

Table 3: Photocatalytic Performance of Bottom-Up Synthesized Materials

| Material | Synthesis Method | Application | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead(II) Coordination Polymer | Sonochemical (Bottom-Up) | Methylene Blue Degradation | Degradation Efficiency & Reusability | 88.2% (1st cycle), 81.7% (5th cycle) | [5] |

| TiO₂-Based Hybrid Gels | Sol-Gel with Organic Ligands (Bottom-Up) | Superoxide Radical Production | Stabilization of Reactive Oxygen Species | Enhanced activity via interfacial charge transfer | [4] |

| 2D Porous Photocatalysts | Bottom-Up Self-Assembly | H₂ Evolution, H₂O₂ Production | Charge Carrier Migration & Mass Diffusion | Superior to bulk counterparts due to structure | [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To provide a practical toolkit for researchers, this section outlines standardized protocols for key synthesis methods cited in this guide.

This protocol describes the post-synthetic treatment of pre-formed perovskite to enhance its photocatalytic properties.

- Step 1: Precursor Synthesis. First, synthesize the

Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂raw material using a co-precipitation method to ensure high crystallinity and avoid surface organic contaminants. - Step 2: Mechanical Treatment. Place the raw material into a ball milling chamber. Use milling balls made of a hard material (e.g., zirconia) as the grinding media.

- Step 3: Process Execution. Process the material at a controlled speed of 300 revolutions per minute (rpm). The treatment duration can be varied (e.g., 1, 2, or 3 hours) to study its effect on particle size and defect density.

- Step 4: Product Collection. After milling, collect the resulting nanoparticles. The final product will have a smaller particle size, a larger specific surface area, and a higher concentration of surface defects.

This protocol utilizes ultrasound to create nanoscale coordination polymers in the amorphous phase.

- Step 1: Solution Preparation. Dissolve the metal salt (e.g., lead(II) nitrate) and the organic linker (e.g., benzene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid, H₂L) in a suitable solvent.

- Step 2: Reaction Setup. Transfer the mixture to an ultrasonic reactor. Either an ultrasonic bath or a more powerful probe homogenizer can be used.

- Step 3: Process Execution. Subject the mixture to ultrasonic irradiation. Key parameters to control include ultrasonic power, temperature, reaction time, and the presence or absence of surfactants to influence the size and morphology of the final product.

- Step 4: Product Isolation. After the reaction is complete, isolate the solid product by filtration or centrifugation. Wash the product thoroughly with solvent and dry it to obtain the final nanocoordination polymer powder.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions in the synthesis protocols discussed above.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Example Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconia Milling Balls | Grinding media for mechanical size reduction and introduction of defects. | Top-Down Ball Milling [2] |

| Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂` Precursor | High-crystallinity raw material for top-down post-treatment. | Top-Down Ball Milling [2] |

| Metal Salts (e.g., Pb²⁺) | Cation source for constructing the inorganic nodes or metal centers in coordination polymers. | Bottom-Up Sonochemical [5] |

| Organic Linkers (e.g., H₂L) | Molecular bridges that connect metal centers to form coordination polymer frameworks. | Bottom-Up Sonochemical [5] |

| Capping Agents (e.g., surfactants, polymers) | Control nanoparticle growth, prevent agglomeration, and dictate final morphology. | Bottom-Up Precipitation [3] |

| Ti(OR)₄ Alkoxide Precursor | Molecular precursor for the sol-gel synthesis of TiO₂-based hybrid materials. | Bottom-Up Sol-Gel [4] |

| Organic Ligands (e.g., carboxylates, diketones) | Modulate surface properties, electronic structure, and defectivity of hybrid photocatalysts. | Bottom-Up Sol-Gel [4] |

The choice between top-down and bottom-up synthesis is not a matter of declaring one superior to the other, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific application. Top-down methods like ball milling offer a robust, scalable route to enhance the surface area and create active defects in pre-existing materials, as demonstrated by the Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ perovskite. In contrast, bottom-up methods provide unparalleled precision for constructing nanomaterials from the ground up, enabling the design of complex architectures such as 2D porous structures and hybrid gels with tailored interfacial properties for superior charge separation and light harvesting.

The future of photocatalytic material design lies in the intelligent integration of both paradigms. A potential hybrid strategy could involve using a top-down method to create a high-surface-area support, followed by a bottom-up technique to decorate it with highly active, well-defined co-catalysts. As the field advances, the continued refinement of these synthesis approaches will be pivotal in developing next-generation photocatalysts for solving pressing global challenges in clean energy and environmental sustainability.

The pursuit of advanced photocatalytic materials for applications ranging from hydrogen production and CO2 reduction to water purification has brought nanomaterial synthesis to the forefront of materials science research. The two fundamental approaches for creating these functional nanomaterials—top-down and bottom-up synthesis—offer distinct pathways with characteristic advantages and limitations. Top-down synthesis involves the physical fragmentation of bulk precursor materials into nanoscale structures through mechanical or chemical means, exemplified by techniques such as ball milling. In contrast, bottom-up synthesis relies on molecular assembly processes, building nanomaterials atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule using chemical reactions and self-assembly principles, with methods including sol-gel processing, hydrothermal synthesis, and sonochemical approaches.

Understanding the mechanistic insights behind these divergent pathways is crucial for rational design of photocatalytic materials with tailored properties. This comparison guide objectively examines both synthesis strategies, focusing on their fundamental principles, experimental implementations, resultant material properties, and photocatalytic performance. By analyzing specific case studies and experimental data, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting and optimizing synthesis methods based on targeted photocatalytic applications, whether for energy conversion, environmental remediation, or chemical synthesis.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Principles

Top-Down Approach: Physical Fragmentation

The top-down synthesis approach operates on the principle of size reduction from bulk materials to nanoscale dimensions through physical fragmentation processes. This methodology typically employs mechanical forces, such as impact, shear, or compression, to break down larger particles into nanostructured materials. The fundamental mechanism involves introducing sufficient energy to overcome the material's cohesive forces, resulting in fracture along crystal planes or defect sites. In photocatalytic material synthesis, top-down methods are particularly valuable for exfoliating layered materials, creating high-surface-area nanostructures, and introducing controlled defects that can enhance catalytic activity.

Ball milling represents one of the most widely implemented top-down techniques, utilizing mechanical impact and friction to achieve particle size reduction. This process not only decreases particle size but also induces structural modifications including crystal disorder, phase transformations, and the creation of surface defects. These modifications profoundly impact the electronic structure of photocatalytic materials by introducing strain, altering band gap energies, and creating active sites for surface reactions. The mechanistic pathway involves repeated deformation, fracture, and cold welding of particles, resulting in a complex interplay between size reduction and defect engineering that collectively influences photocatalytic performance [2].

Bottom-Up Approach: Molecular Assembly

Bottom-up synthesis operates on fundamentally different principles, constructing nanomaterials through controlled molecular assembly processes that build up structures from atomic or molecular precursors. This approach leverages chemical reactions, self-assembly, and nucleation-growth mechanisms to create nanostructures with precise control over composition, morphology, and crystal structure. The fundamental mechanisms include molecular precursor organization, chemical transformation, and directed assembly through thermodynamic and kinetic control. In photocatalytic applications, bottom-up methods enable atomic-level engineering of active sites, controlled heterojunction formation, and precise doping for band gap manipulation.

Key bottom-up techniques include sol-gel processing, hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis, sonochemical methods, and chemical precipitation. The sol-gel process, for instance, involves the transformation of molecular precursors into a colloidal solution (sol) that evolves toward a gel-like network, offering excellent control over composition and porosity. Hydrothermal methods utilize heated aqueous solutions at high pressure to crystallize materials from solution, enabling the synthesis of highly crystalline nanostructures with controlled morphologies. Sonochemical synthesis employs ultrasonic radiation to generate transient localized hot spots with extreme conditions, driving chemical reactions and nucleation events that yield unique nanostructures. Molecular self-assembly strategies, including DNA-mediated assembly, provide even more precise control over hierarchical structure formation through programmable interactions between building blocks [5] [4] [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Top-Down Synthesis: Ball Milling Protocol

The top-down synthesis of photocatalytic materials via ball milling follows a systematic protocol designed to achieve controlled size reduction and defect engineering. For the synthesis of lead-free double perovskite Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ photocatalysts, researchers implemented the following optimized procedure [2]:

Precursor Preparation: Begin with high-purity raw materials including cesium chloride (CsCl, 99.9%), copper(II) chloride (CuCl₂, 99%), and antimony(III) chloride (SbCl₃, 99%). Prepare the initial Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ perovskite using a co-precipitation method by dissolving stoichiometric ratios of precursors in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) under inert atmosphere. Recover the precipitate by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 10 minutes and dry at 80°C for 12 hours under vacuum.

Ball Milling Process: Load the co-precipitated perovskite powder (2.0 g) into a zirconia milling jar (250 mL capacity) with zirconia grinding balls (5 mm diameter, ball-to-powder mass ratio of 30:1). Seal the jar under argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation. Process the material using a high-energy planetary ball mill at 300 rpm for varying durations (1-3 hours) with rotation direction reversal every 15 minutes to ensure homogeneous milling. Maintain temperature control at 25°C using a cooling system to prevent thermal degradation.

Post-Treatment: Following milling, collect the nanostructured powder and sieve through a 400-mesh screen to obtain uniformly sized particles. Characterize the resulting material using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements to confirm phase purity, morphology, and surface area.

Critical Parameters: Key factors influencing the final material properties include milling duration, rotational speed, ball-to-powder ratio, and milling atmosphere. Optimization of these parameters enables control over particle size, specific surface area, and defect concentration, which directly impact photocatalytic performance.

Bottom-Up Synthesis: Sonochemical Protocol

The bottom-up synthesis of lead(II) coordination polymers for photocatalytic applications employs sonochemical methods that utilize ultrasonic energy to drive molecular assembly. The following protocol details the synthesis of nano [Pb₄(O)(L)₃(H₂O)]ₙ in amorphous phases [5]:

Reagent Preparation: Prepare a 50 mM solution of lead(II) acetate trihydrate (Pb(CH₃COO)₂·3H₂O, 99%) in deionized water. Separately, prepare a 37.5 mM solution of benzene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (isophthalic acid, H₂L, 98%) in ethanol. Adjust the pH of the lead solution to 6.5 using dilute ammonium hydroxide solution to prevent premature precipitation.

Sonochemical Synthesis: Combine the precursor solutions in a 1:1 molar ratio of Pb:H₂L in a 250 mL double-walled reaction vessel equipped with a temperature controller. For ultrasonic bath processing, immerse the reaction vessel in an ultrasonic cleaner (40 kHz frequency, 300 W power) and maintain the temperature at 60°C for 90 minutes with continuous stirring. Alternatively, for probe homogenizer processing, immerse a titanium ultrasonic horn (20 kHz frequency) directly into the reaction mixture and irradiate at 60% amplitude (180 W/cm²) for 30 minutes with pulsed operation (5 s on, 2 s off) to control heating.

Surfactant Modification: To control morphology, add cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, 0.1 mM) as a surfactant before sonication. The surfactant molecules direct the assembly process by modifying surface energy and growth kinetics.

Product Recovery: After sonication, allow the mixture to cool to room temperature and recover the precipitate by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Wash the product sequentially with ethanol and deionized water (three times each) to remove unreacted precursors and surfactant. Dry the final nanostructured coordination polymer at 70°C for 12 hours under vacuum.

Critical Parameters: The size, morphology, and crystallinity of the resulting nanomaterials are influenced by ultrasonic power, reaction temperature, duration, initial reagent concentration, and surfactant presence. Systematic optimization of these parameters enables precise control over the structural properties that govern photocatalytic activity.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Structural and Photocatalytic Properties

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesized Photocatalytic Materials

| Parameter | Top-Down (Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ Perovskite) [2] | Bottom-Up (Pb(II) Coordination Polymer) [5] | Bottom-Up (TiO₂-Diketone Hybrid) [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Method | Ball milling (3 hours) | Sonochemical (probe homogenizer) | Sol-gel with organic ligands |

| Crystallinity | High crystallinity with milling-induced defects | Amorphous phase | Amorphous gel structure with oxygen vacancies |

| Specific Surface Area | 5.23 m²/g (from 0.57 m²/g pre-milling) | Not specified | Not specified |

| Band Gap Energy | 1.02 eV (direct bandgap) | Determined via Tauc plot from DRS | Reduced from 3.2 eV (pristine TiO₂) |

| Photocatalytic Performance | CO yield: 72.17 μmol/g (1.6× enhancement) | MB degradation: 88.2% (first cycle) | Enhanced ROS generation and stabilization |

| Key Advantages | 10× surface area increase, rich active sites, enhanced light absorption | High degradation efficiency, reusable for multiple cycles | Visible light activation, superoxide radical stabilization |

| Limitations | Possible contamination from milling media, broad size distribution | Lower thermal stability compared to crystalline phases | Complex synthesis optimization required |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Photocatalytic Performance Metrics Under Standardized Conditions

| Photocatalyst | Synthesis Approach | Application | Performance Metric | Reference Material | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ [2] | Top-down (ball milling) | CO₂ reduction to CO | 72.17 μmol/g in 4 h | 45.01 μmol/g (pre-milling) | 1.60× |

| Nano [Pb₄(O)(L)₃(H₂O)]ₙ [5] | Bottom-up (sonochemical) | Methylene blue degradation | 88.2% efficiency (C₀=0.6 mg/L, pH=7, 60 min) | Crystalline phase: 73.5% | 1.20× |

| Co₃O₄ Nanospheres [10] | Bottom-up (various methods) | Organic pollutant degradation | Complete MB degradation (50 mg/L, 3 h) | Varies with synthesis method | Dependent on morphology |

| TiO₂-Ligand Hybrids [4] | Bottom-up (sol-gel) | Reactive oxygen species generation | Enhanced •OH and O₂•− production | Pristine TiO₂ | Significant visible light activity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Representative Examples | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zirconia Grinding Media | Mechanical energy transfer in ball milling | 5 mm diameter balls for perovskite processing [2] | Ball-to-powder ratio (30:1), potential contamination |

| Metal Alkoxide Precursors | Molecular building blocks for sol-gel synthesis | Ti(OR)₄ for TiO₂ hybrid materials [4] | Moisture sensitivity, hydrolysis rates |

| Organic Ligands | Structure-directing agents, complexation | Acetylacetone, carboxylic acids, diketones [4] | Denticity, coordination strength, thermal stability |

| Sonochemical Probes | Ultrasonic energy delivery for nucleation | Titanium horn (20 kHz) for coordination polymers [5] | Amplitude control, pulsed operation, temperature management |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Morphology control, pore formation | CTAB for nanocoordination polymers [5] | Concentration optimization, removal strategies |

| Solvents and Reaction Media | Dissolution, reaction environment | DMF for perovskite precursors, ethanol for coordination polymers [5] [2] | Polarity, boiling point, coordination ability |

| Defect Engineering Agents | Controlled vacancy creation | Reducing agents in sol-gel processes [4] | Concentration effects on electronic properties |

The comparative analysis of top-down and bottom-up synthesis approaches reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each strategy in photocatalytic material development. Top-down methods, particularly ball milling, excel at creating high-surface-area materials with rich defect concentrations that enhance light absorption and provide abundant active sites. The significant enhancement in CO₂ reduction performance demonstrated by ball-milled Cs₄CuSb₂Cl₁₂ perovskite (1.60× increase in CO yield) highlights the efficacy of this approach for optimizing existing materials [2]. Conversely, bottom-up methods offer superior control over molecular-level structure, enabling precise engineering of coordination environments, band gap energies, and surface functionalities. The enhanced photocatalytic degradation efficiency of sonochemically synthesized coordination polymers (88.2% for methylene blue) underscores the potential of molecular assembly for creating highly active catalysts [5].

Future research directions should focus on hybrid approaches that combine the advantages of both methodologies. The integration of bottom-up precision in molecular design with top-down introduction of controlled defects could enable unprecedented control over photocatalytic properties. Additionally, advances in computational prediction of material properties, as demonstrated for TiO₂ hybrid systems [4], will accelerate the rational design of novel photocatalysts. Green synthesis approaches utilizing waste-derived precursors [10] and sustainable processes will also be essential for the large-scale implementation of photocatalytic technologies. As the field progresses, the complementary application of both synthesis paradigms, guided by mechanistic understanding and computational prediction, will drive the development of next-generation photocatalytic materials for addressing critical energy and environmental challenges.

The pursuit of advanced photocatalytic materials for energy and environmental applications relies heavily on the synthesis methods used to create nanostructures with precise architectural control. The fundamental dichotomy in nanomaterial fabrication lies between top-down and bottom-up approaches, each offering distinct advantages for manipulating material properties critical to photocatalytic performance [11]. Top-down methods involve the physical or chemical breakdown of bulk materials into nanostructures, while bottom-up approaches assemble atoms and molecules into nanoscale architectures through controlled chemical reactions and self-assembly processes [12].

The selection between these synthesis pathways profoundly influences key material characteristics including surface area, crystallinity, defect concentration, and surface chemistry—all determining factors in photocatalytic efficiency [13] [11]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of synthesis methodologies across three pivotal material systems: metal nanoparticles, carbon nitrides, and quantum dots, with particular emphasis on their photocatalytic applications and performance metrics.

Synthesis Methodologies: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Approaches

Fundamental Principles and Techniques

Top-down synthesis encompasses strategies that deconstruct bulk materials into nanostructures through physical or chemical fragmentation. Common techniques include laser ablation, ball milling, electrochemical dispersion, and arc discharge methods [11] [8]. These approaches typically employ external forces to reduce material dimensions to the nanoscale. For instance, in the synthesis of Pt/C electrocatalysts, electrochemical dispersion of platinum foil under pulsed alternating current represents a top-down method where bulk platinum is fragmented into nanoparticles supported on carbon [8].

Bottom-up synthesis utilizes chemical or physical processes to assemble atoms, molecules, and clusters into nanostructures. Predominant methods include sol-gel processing, hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis, chemical vapor deposition, and polyol reduction [11]. These approaches exploit molecular self-assembly, chemical reactions, and nucleation/growth kinetics to build nanomaterials with controlled dimensions. The polyol process for Pt/C catalyst preparation, where platinum ions are chemically reduced in the presence of a carbon support, exemplifies a bottom-up approach [8].

Comparative Analysis of Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparison of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesis Approaches

| Parameter | Top-Down Approaches | Bottom-Up Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Physical/chemical fragmentation of bulk materials | Atom/molecular assembly into nanostructures |

| Common Techniques | Laser ablation, ball milling, electrochemical dispersion, arc discharge | Sol-gel, hydrothermal/solvothermal, chemical vapor deposition, polyol reduction |

| Advantages | Simpler scaling, no molecular-level control required | Superior control over size, shape, and composition; higher crystallinity |

| Disadvantages | Surface defects, irregular shapes, size polydispersity | Complex purification, potential solvent contamination, slower processes |

| Typical Defects | Surface imperfections, stress-induced defects | Point defects, vacancy complexes |

| Cost Considerations | High energy consumption for fragmentation | Expense of precursor materials and reaction systems |

| Material Examples | Silicon nanowires, electrochemically dispersed Pt/C | Carbon quantum dots, sol-gel ZnO, polyol-synthesized Pt/C |

The synthesis approach significantly influences critical photocatalytic parameters. Bottom-up methods typically yield materials with higher crystallinity and fewer defects due to controlled growth conditions, while top-down approaches often introduce surface imperfections that may act as recombination centers for photogenerated charge carriers [11]. However, hybrid strategies such as BUTTONS (Bottom-Up Then Top-Down Synthesis) have emerged, where materials created via bottom-up methods are subsequently etched or modified using top-down approaches to achieve unique architectures not accessible through either method alone [14].

Metal Nanoparticle Systems

Synthesis and Performance in Photocatalytic Applications

Metal nanoparticles, particularly platinum, serve as critical components in photocatalytic systems, often functioning as cocatalysts that enhance charge separation and provide active sites for reduction reactions. The synthesis approach profoundly influences their morphological characteristics and functional performance.

Table 2: Comparison of Pt/C Catalysts Synthesized via Different Approaches

| Synthesis Method | Approach Category | Average Pt Size (nm) | Electrochemically Active Surface Area (m²/g) | Mass Activity for Ethanol Oxidation (A/g) | Stability (Cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Dispersion (ED) | Top-down | 3.5 | 52.5 | 105 | >5000 |

| Polyol Process (CH) | Bottom-up | 2.1 | 73.2 | 135 | ~3000 |

| Commercial Pt/C | Not specified | 2.8 | 63.1 | 122 | ~4000 |

Comparative studies of Pt/C electrocatalysts reveal distinct performance patterns linked to synthesis methodology. The bottom-up polyol process produces smaller nanoparticles (2.1 nm) with higher electrochemical surface area (73.2 m²/g), translating to superior initial mass activity for ethanol oxidation (135 A/g) [8]. Conversely, top-down electrochemical dispersion yields larger particles (3.5 nm) with reduced surface area (52.5 m²/g) but demonstrates exceptional stability, maintaining performance beyond 5000 cycles [8]. This stability advantage highlights how top-down synthesized materials may offer superior durability despite potentially lower initial activity.

Experimental Protocols for Metal Nanoparticle Synthesis

Top-Down Protocol: Electrochemical Dispersion of Platinum [8]

- Prepare electrolyte solution of 2M NaOH with Vulcan XC-72 carbon support (2 g/L concentration)

- Suspend carbon support in electrolyte with constant stirring (200 rpm) and cool to 45-50°C

- Install platinum foil electrodes (6 cm² surface area) in the electrolyzer

- Apply pulsed alternating current (1 A/cm² density, 50 Hz frequency) to disperse platinum

- Control metal loading through synthesis time duration

- Filter suspension and rinse with distilled water to neutral pH

- Dry electrocatalyst powder at 75°C until constant weight achieved

Bottom-Up Protocol: Polyol Process for Pt/C Synthesis [8]

- Add carbon support (0.2 g) and H₂[PtCl₆]·6H₂O to ethylene glycol/water mixture (75 mL/30 mL)

- Homogenize carbon suspension in NaOH solution via ultrasonication for 30 minutes

- Adjust solution to pH 11 using aqueous ammonium solution with continuous stirring

- Introduce freshly prepared 0.5M NaBH₄ solution (15 mL) under constant stirring (200 rpm)

- Continue stirring for 50 minutes to complete reduction process

- Filter suspension and wash repeatedly with acetone and distilled water to neutral pH

- Dry catalyst at 75°C until constant weight is obtained

Carbon Nitride and Quantum Dot Systems

Synthesis Strategies and Photocatalytic Performance

Carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly carbon nitrides and carbon quantum dots (CQDs), have emerged as promising photocatalysts and catalytic enhancers due to their tunable electronic properties, visible light responsiveness, and potential for sustainable synthesis from biomass precursors.

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) represents a metal-free polymeric semiconductor with a bandgap of approximately 2.7 eV, responsive to visible light up to 460 nm [15]. Its synthesis typically employs bottom-up approaches through thermal condensation of nitrogen-rich precursors like urea or melamine. Modification strategies include nanostructuring, elemental doping, and heterojunction formation to enhance photocatalytic performance [16].

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) constitute a class of quasi-spherical, monodisperse carbon nanoparticles below 10 nm in diameter, exhibiting unique optical properties including excellent sunlight harvesting, tunable photoluminescence, and up-conversion photoluminescence (UCPL) that enables utilization of the full solar spectrum [17]. Their synthesis often employs sustainable bottom-up approaches using biomass precursors such as licorice powder, ginkgo biloba leaves, or mulberry branch powder through hydrothermal treatment [16].

Table 3: Photocatalytic Performance of Carbon Nitride and Quantum Dot Systems

| Material System | Synthesis Method | Application | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CQDs/g-C₃N₄ heterojunction | Bottom-up (hydrothermal) | CO₂ reduction | CO evolution: 28.9 μmol·g⁻¹ (3× improvement vs. pure PCN) | [16] |

| CQDs/g-C₃N₄ heterojunction | Bottom-up (hydrothermal) | Cr(VI) reduction | Removal efficiency: 2.48× improvement vs. pure PCN | [16] |

| CNQDs/TiO₂ heterojunction | Bottom-up (mechanical mixing) | Bisphenol A degradation | Rate constant: 0.30 (0.17 for pure TiO₂) | [15] |

| CNQDs/TiO₂ heterojunction | Bottom-up (mechanical mixing) | H₂ production | 30 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ higher than pure TiO₂ | [15] |

| Biomass-derived CQDs | Bottom-up (hydrothermal) | Various photocatalytic applications | Enhanced light absorption and charge separation | [16] [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Carbon-Based Materials

Bottom-Up Protocol: CQDs/g-C₃N₄ Heterojunction from Licorice Powder [16]

- Synthesize polymer carbon nitride (PCN) via thermal condensation of urea at 550°C for 4 hours

- Prepare suspension A: disperse 1g PCN and 0.1g SDBS in 40mL deionized water, ultrasonicate 2 hours

- Prepare suspension B: hydrothermally treat licorice powder in water at 180°C for 12 hours, filter through 0.22μm membrane

- Mix suspensions A and B in varying mass ratios (licorice powder to PCN from 0.01:1 to 0.10:1)

- Transfer mixture to Teflon-lined autoclave, maintain at 180°C for 12 hours

- Centrifuge product, wash with ethanol/water mixture, dry at 60°C overnight

Bottom-Up Protocol: CNQDs/TiO₂ Heterojunction [15]

- Pre-treat commercial TiO₂ nanoparticles (P25) with alkali hydrothermal method: disperse 1g TiO₂ in 50mL NaOH solution (10 mol/L), stir 30 minutes, hydrothermally treat at 120°C for 3 hours

- Prepare CNQDs suspension by dispersing in deionized water

- Mix CNQDs suspension with treated TiO₂ in varying mass ratios with continuous mechanical stirring for 12 hours

- Centrifuge composite material, wash with deionized water, dry at 60°C

Metal Oxide Semiconductor Systems

Zinc Oxide Synthesis and Performance

Zinc oxide (ZnO) represents a widely studied photocatalytic semiconductor with a bandgap of approximately 3.2 eV, analogous to TiO₂ but with superior absorption efficiency across a broader solar spectrum [18]. Synthesis methodology significantly influences its morphological characteristics and photocatalytic performance.

Table 4: Sol-Gel Synthesized ZnO with Different Solvents

| Solvent Used | Crystallite Size (nm) | Band Gap (eV) | MB Degradation Efficiency | Degradation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 25.3 | 3.18 | 98% | 30 minutes |

| 1-Propanol | 28.7 | 3.21 | 92% | 40 minutes |

| 1,4-Butanediol | 32.1 | 3.24 | 85% | 50 minutes |

Bottom-Up Protocol: Sol-Gel ZnO Synthesis [18]

- Dissolve zinc acetate dihydrate in 50mL selected solvent (ethanol, 1-propanol, or 1,4-butanediol) with magnetic stirring for 30 minutes at 50°C (Pot 1)

- Dissolve oxalic acid in 25mL of the same solvent at room temperature (Pot 2)

- Slowly add Pot 2 contents to Pot 1 with continuous stirring until viscous white solution forms

- Continue stirring at 70°C until gel formation occurs

- Dry resulting gel at 80°C overnight in oven

- Calcine dried gel at 600°C for 240 minutes in muffle furnace

- Grind resulting powder using mortar and pestle for characterization

Interrelationships: Synthesis Approaches and Material Properties

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between synthesis approaches, material systems, and their resulting properties in photocatalytic applications:

Synthesis-Property-Application Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Hexachloroplatinic acid (H₂[PtCl₆]·6H₂O) | Platinum precursor for bottom-up synthesis | Polyol synthesis of Pt/C catalysts [8] |

| Zinc acetate dihydrate | Zinc precursor for metal oxide synthesis | Sol-gel preparation of ZnO nanoparticles [18] |

| Urea | Nitrogen-rich precursor for carbon nitride | Thermal condensation to g-C₃N₄ [16] |

| Licorice powder | Biomass source for carbon quantum dots | Sustainable CQDs synthesis via hydrothermal treatment [16] |

| Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) | Reducing agent for metal precursors | Chemical reduction of platinum ions [8] |

| Ethylene glycol | Solvent and reducing agent in polyol process | Pt nanoparticle synthesis [8] |

| Titanium dioxide (P25) | Benchmark photocatalyst support | Composite formation with CNQDs [15] |

| CTAB (Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Surfactant template for nanostructuring | Morphology control in nanomaterial synthesis [14] |

| Sodium hydroxide | pH control and hydrolysis agent | Alkaline treatment of TiO₂ nanoparticles [15] |

The comparative analysis of top-down and bottom-up synthesis approaches reveals a complex trade-off between photocatalytic activity, stability, and synthetic control. Bottom-up methods generally enable superior control over nanoscale architecture, yielding materials with optimized crystallinity and surface properties for enhanced initial photocatalytic performance [11]. Conversely, top-down approaches often produce materials with exceptional stability and durability, albeit with potentially lower initial activity [8].

The emerging paradigm of hybrid strategies (BUTTONS) that sequentially employ bottom-up and top-down methods represents a promising direction for fabricating nanostructures with customized properties not accessible through either approach alone [14]. Furthermore, the integration of sustainable biomass precursors in bottom-up synthesis aligns with green chemistry principles while maintaining competitive photocatalytic performance [16] [6].

Selection of synthesis methodology must consider the specific application requirements: bottom-up approaches for maximum efficiency in controlled environments, top-down methods for applications demanding long-term stability, and hybrid approaches for specialized architectural requirements. This strategic alignment of material synthesis with application needs will continue to drive innovation in photocatalytic nanomaterial development.

The pursuit of efficient photocatalytic materials for applications ranging from environmental remediation to sustainable chemical synthesis hinges on the precise control of synthesis parameters. The choice between top-down and bottom-up nanomaterial synthesis strategies fundamentally influences the structural properties and subsequent performance of the resulting photocatalysts [6] [8]. Bottom-up approaches construct materials from atomic or molecular precursors, enabling precise control over composition and morphology, while top-down methods break down bulk materials into nanostructures, often favoring high throughput [8]. Within this overarching framework, temperature, precursor selection, and reaction media emerge as critical variables that dictate crystallinity, surface area, light absorption, and ultimately photocatalytic efficiency. This guide objectively compares the performance of photocatalysts synthesized under varying conditions, providing supporting experimental data to inform research and development efforts.

Temperature: A Pivotal Parameter in Synthesis and Reaction

Temperature exerts a profound influence during both the synthesis of photocatalysts and their subsequent application in chemical reactions. Its effects are multifaceted, impacting crystallinity, particle size, and the formation of critical active sites.

Temperature During Photocatalyst Synthesis

The synthesis temperature is a powerful tool for tuning the fundamental properties of photocatalytic nanomaterials. Research on peroxo-titanate nanotubes (PTNTs) reveals that higher hydrothermal synthesis temperatures (from 120 °C to 200 °C) significantly enhance material crystallinity and specific surface area [19]. For instance, the specific surface area increased from 117 m²/g for PTNTs synthesized at 100 °C to 268 m²/g for those synthesized at 200 °C [19]. This improvement in structural properties directly translated to superior photocatalytic performance, with the PTNT200 sample achieving a 98.2% Rhodamine B degradation rate under visible light [19]. However, a critical trade-off exists: while crystallinity improves, the formation of peroxo-bondings—which are crucial for visible light responsiveness—decreases at higher temperatures, though it remains achievable even at 200 °C [19].

A similar principle applies to the synthesis of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C(3)N(4)). The precursor and synthesis temperature jointly determine the material's final properties. In one study, g-C(3)N(4) synthesized from urea at 500 °C demonstrated the highest photocatalytic degradation rate of procaine under visible light, outperforming samples derived from melamine or mixtures of melamine and cyanuric acid at other temperatures [20]. This highlights the existence of an optimal synthesis temperature that maximizes photocatalytic activity for a given material system.

Table 1: Effect of Synthesis Temperature on Photocatalyst Properties and Performance

| Photocatalyst | Synthesis Temperature | Key Property Changes | Photocatalytic Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNT | 100°C → 200°C | ↑ Crystallinity; ↑ Surface Area (117 → 268 m²/g); ↓ Peroxo-bonding | Rhodamine B degradation: 98.2% (PTNT200, Vis light) | [19] |

| g-C(3)N(4) (Urea) | 450°C, 500°C, 550°C | Optimal structural properties at 500°C | Highest procaine degradation rate under visible light | [20] |

Temperature During the Photocatalytic Reaction

The temperature at which the photocatalytic reaction itself occurs is equally critical. Studies on the photocatalytic destruction of methylene blue using TiO(2) and Pd/TiO(2) show that reaction rates generally increase with temperature from 0 °C to 50 °C [21]. This is attributed to enhanced mobility of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and faster interfacial charge transfer. However, an upper limit exists; when the temperature reaches 70 °C, the reaction rate drops as the recombination of charge carriers increases and adsorption—an often essential exothermic first step—becomes less favorable [21]. In contrast, Cu/TiO(_2) was found to be more active at room temperature than at higher temperatures, underscoring that the optimal reaction temperature is also cocatalyst-dependent [21].

Furthermore, in a model photocatalytic system for ethylene glycol synthesis from methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) using Pt/TiO(_2), the reaction temperature was optimized to 55 °C. Deviations to either 25 °C or 90 °C resulted in decreased activity [22]. This demonstrates that for complex organic syntheses, a specific temperature window is necessary to balance reaction kinetics, charge carrier dynamics, and adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

Diagram 1: Temperature Impact on Photocatalytic Activity. This workflow illustrates the competing effects of reaction temperature, showing an optimal range for peak performance.

Precursor Selection: Governing Morphology and Activity

The choice of precursor is a fundamental determinant in bottom-up synthesis, directly influencing the morphology, chemical composition, and electronic structure of the final photocatalyst.

In the synthesis of g-C(3)N(4), different precursors lead to materials with distinct properties. Urea, melamine, and mixtures of melamine and cyanuric acid undergo thermal polymerization to form g-C(3)N(4), but the resulting materials differ in their surface area, crystallinity, and band gap [20]. The g-C(3)N(4) sample derived from urea at 500 °C exhibited the highest degradation rate for the pharmaceutical pollutant procaine under visible light, highlighting how precursor selection can be optimized for a specific application [20]. The underlying mechanism is that the precursor affects the degree of polymerization and the density of defects in the g-C(3)N(4) framework, which in turn modulates its light-absorption and charge-separation capabilities.

For titanium-based nanomaterials, the precursor's chemical properties dictate the synthesis pathway. The conventional synthesis of titanate nanotubes (TNTs) requires a high concentration of NaOH (≥10 mol/L) and a precursor like TiO(2) (P25) with strong Ti–O bonds [19]. In contrast, a more recent bottom-up approach uses TiH(2) as a precursor, which has weaker Ti–H bonds. This allows for synthesis in a low-concentration alkaline solution (1.5 mol/L) and leads to the incorporation of peroxo-bondings into the structure, resulting in peroxo-titanate nanotubes (PTNTs) with visible light activity [19]. This represents a significant advancement in designing environmentally friendlier synthesis routes while simultaneously improving functional properties.

Table 2: Impact of Precursor Selection on Photocatalyst Synthesis and Performance

| Target Material | Precursor(s) | Synthesis Conditions | Key Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g-C(3)N(4) | Urea, Melamine, Melamine + Cyanuric Acid | Thermal polymerization (450-550 °C) | Urea-derived g-C(3)N(4) (at 500°C) showed highest activity for procaine degradation under visible light. | [20] |

| Peroxo-Titanate Nanotube (PTNT) | TiH(_2) | 1.5 mol/L NaOH, Hydrothermal (100-200 °C) | Enabled visible-light activity via peroxo-bonding; greener synthesis with low-concentration NaOH. | [19] |

| Titanate Nanotube (TNT) | TiO(_2) (P25) | 10 mol/L NaOH, Reflux at 115 °C | Conventional method requiring high-concentration NaOH; typically UV-active. | [19] |

Reaction Media: Solvent and Cocatalyst Effects

The environment in which a photocatalytic reaction occurs, defined by the solvent and the presence of cocatalysts, plays a decisive role in determining reaction pathways and efficiency.

The Role of Solvents and Cocatalysts

The solvent is not merely a passive medium but an active component. In the photocatalytic synthesis of ethylene glycol from MTBE using a Pt/TiO(2) catalyst, the presence of water was found to be essential [22]. When the reaction was attempted in the absence of water, no H(2) production or dimer formation was observed, underscoring water's critical role in the reaction mechanism, likely as a proton source and participant in the catalytic cycle [22]. Furthermore, a specific ratio of MTBE to water was necessary for optimal performance, indicating that the solvent system must be carefully optimized for the specific target reaction [22].

Cocatalysts, often noble metals or transition metals, are indispensable for enhancing photocatalytic performance by facilitating charge separation and providing active sites. In the MTBE coupling reaction, Pt was uniquely effective as a cocatalyst on TiO(2); other tested metals like Pd, Ir, Rh, Au, and Ag showed no or negligible activity [22]. This high specificity highlights the need for matching the cocatalyst to the desired redox chemistry. Similarly, in the degradation of methylene blue, Pd was a more effective cocatalyst than Cu for TiO(2), and the optimal reaction temperature was itself dependent on the identity of the cocatalyst [21]. This interplay shows that parameters cannot be viewed in isolation.

Diagram 2: Cocatalyst and Solvent Roles in Charge Separation. This diagram shows how cocatalysts and solvents extract electrons and holes to drive desired reactions and suppress recombination.

Synthesis Approach: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

The choice between a top-down and a bottom-up synthesis method is a strategic decision that influences the nature of the reaction media and the properties of the final catalyst. A comparison of Pt/C electrocatalysts synthesized via a bottom-up polyol process (chemical reduction) and a top-down electrochemical dispersion method revealed distinct differences [8]. The catalyst produced by the top-down method featured larger platinum nanoparticle sizes and, consequently, demonstrated superior stability during long-term cycling tests [8]. This illustrates a common trade-off: bottom-up methods often allow for finer control over nanoparticle size and distribution, while top-down methods can produce more robust and stable structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the synthesis and testing of photocatalysts, as featured in the cited research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Photocatalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TiO(_2) (P25) | Benchmark photocatalyst; versatile precursor for top-down synthesis. | Starting material for conventional titanate nanotube (TNT) synthesis [19]; support for Pt/Pd/Cu cocatalysts [21] [22]. |

| TiH(_2) | Precursor for bottom-up synthesis. | Used to synthesize peroxo-titanate nanotubes (PTNTs) via a peroxo-titanium complex (PTC) ion solution [19]. |

| Urea / Melamine | Nitrogen-rich precursors for g-C(3)N(4). | Used in thermal polymerization to create graphitic carbon nitride (g-C(3)N(4)) photocatalysts [20]. |

| H(2)PtCl(6)·6H(_2)O | Common platinum precursor for cocatalyst deposition. | Source of Pt for impregnation onto TiO(2) P25 to create Pt/TiO(2) for C-C coupling reactions [22] [8]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH(_4)) | Reducing agent. | Used in the polyol process for the chemical reduction of metal precursors to form nanoparticles (bottom-up) [8]. |

| NaOH Solution | Alkaline reaction medium. | Essential for hydrothermal synthesis of nanotube structures (e.g., TNTs, PTNTs) [19]. |

| Methylene Blue / Rhodamine B | Model organic pollutant dyes. | Used as target compounds to benchmark and compare photocatalytic degradation performance [21] [19]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear basis for comparison, detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide are outlined below.

- Catalyst Preparation: Pd/TiO(2) and Cu/TiO(2) catalysts (0.5 wt.% metal loading) are prepared via incipient-wetness impregnation of commercial TiO(_2) with aqueous solutions of Pd and Cu precursors, followed by drying and reduction.

- Reaction Setup: A specified amount of catalyst (e.g., 10-50 mg) is dispersed in an aqueous solution of methylene blue (e.g., 50 mL, 10 ppm concentration). The suspension is stirred in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

- Photocatalytic Testing: The suspension is irradiated under UV light (e.g., a mercury lamp). The reaction temperature is controlled using a water bath or heating mantle, with tests conducted at various temperatures (e.g., 0°C, 25°C, 50°C, 70°C).

- Analysis: At regular time intervals, aliquots are withdrawn, centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and analyzed by UV-Vis spectrophotometry to measure the residual concentration of methylene blue at its characteristic absorption wavelength (≈664 nm). The degradation efficiency is calculated as (C(0) - C)/C(0) × 100%, where C(_0) and C are the initial and time 't' concentrations, respectively.

- Precursor Solution Preparation: 1.87 g of TiH(2) powder is added to a mixed solution of 62.5 mL H(2)O(_2) (30%) and 15.29 mL of 10 M NaOH, resulting in a 1.5 mol/L NaOH solution. The mixture is stirred for 2 hours to form a peroxo-titanium complex (PTC) ion solution.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Approximately 80 mL of the PTC ion solution is transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave. The autoclave is sealed and heated at the target temperature (e.g., 120°C, 150°C, 200°C) for 24 hours.

- Post-Synthesis Processing: After cooling naturally to room temperature, the resulting precipitate is collected and washed repeatedly with ultrapure water via vacuum filtration until the conductivity of the filtrate is low (≈5 μS/cm). The final product is dried using a freeze dryer.

- Catalyst Preparation: Pt/TiO(2) catalyst is prepared by depositing Pt nanoparticles onto a TiO(2) support (e.g., P25 or TiO(B)) via impregnation or photodeposition, followed by calcination at a specific temperature (e.g., 650°C for Pt/C-TiO(B)-650).

- Reaction Setup: In a photoreactor, 10 mg of catalyst is dispersed in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of MTBE and water (total volume 10 mL). The reactor is sealed and purged with an inert gas (e.g., Ar) to remove air.

- Photocatalytic Reaction: The suspension is stirred and irradiated with a focused LED or Xe lamp (e.g., 320-500 nm wavelength range) at a controlled temperature of 55°C.

- Product Analysis: The gaseous products (H(_2)) are quantified using gas chromatography (GC) with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The liquid organic products are analyzed by GC-MS or GC with a flame ionization detector (FID) to identify and quantify the dimer coupling products (1,2-di-tert-butoxyethane, etc.).

Historical Evolution and Technological Drivers in Photocatalyst Fabrication

The fabrication of photocatalytic materials is fundamentally governed by two distinct philosophical approaches: top-down and bottom-up synthesis. Top-down methods involve the physical or mechanical breakdown of bulk precursor materials into nanostructures, utilizing techniques such as ball milling and laser ablation to reduce material dimensions to the nanoscale [11]. In contrast, bottom-up approaches construct nanomaterials atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule from smaller building blocks, employing chemical reactions and molecular self-assembly to build up complex nanostructures with precise control over their architecture [11]. The selection between these pathways profoundly influences the resulting material's physicochemical properties, including surface area, crystallinity, defect concentration, and ultimately, photocatalytic efficiency.

The historical evolution of photocatalyst fabrication has been driven by the continuous pursuit of materials with enhanced light absorption, charge separation, and surface reactivity. The field gained significant momentum following the pioneering 1972 work of Fujishima and Honda, who demonstrated photocatalytic water splitting using titanium dioxide (TiO₂) [23] [24]. This breakthrough established TiO₂ as a photocatalytic "workhorse" and triggered extensive research into semiconductor-based photocatalysts [24]. Over subsequent decades, research efforts have expanded to address key limitations, particularly the narrow light absorption range of early photocatalysts and the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [25]. Recent technological drivers have focused on developing green synthesis methods, incorporating waste-derived materials, implementing computational design approaches, and creating multi-functional nanocomposites with enhanced visible-light activity [23] [10].

Fundamental Synthesis Mechanisms and Methodologies

Top-Down Fabrication Approaches

Top-down synthesis methods operate on the principle of size reduction from bulk materials through physical forces or energy input. Ball milling represents a widely-employed mechanical approach where impact and shear forces between grinding media progressively fracture bulk materials into nanometer-sized particles [11]. This method offers scalability and simplicity but may introduce crystallographic defects and surface contamination. Laser ablation utilizes high-energy laser pulses directed at a target material immersed in a liquid or gas medium, vaporizing and ejecting clusters that form nanoparticles upon cooling [11]. This technique produces high-purity nanoparticles without chemical precursors but requires specialized equipment and precise parameter control. Sputtering techniques involve the bombardment of a target material with energetic ions, dislodging atoms that subsequently deposit as thin films on substrates [11]. Sputtering enables precise thickness control and uniform coatings but typically operates under vacuum conditions, adding complexity and cost.

The top-down approach generally offers advantages in processing throughput and direct patterning capabilities but faces inherent limitations regarding structural precision at atomic scales. As material dimensions approach the nanometer range, surface defects induced by mechanical or thermal stress can detrimentally impact photocatalytic performance by creating recombination centers for charge carriers [11]. Consequently, post-synthesis annealing treatments are often required to improve crystallinity, potentially complicating manufacturing processes and increasing energy consumption.

Bottom-Up Fabrication Approaches

Bottom-up synthesis constructs nanomaterials through atomistic or molecular assembly, enabling precise control over composition, structure, and morphology. Sol-gel processing involves the transition of a solution (sol) into a solid gel phase through hydrolysis and condensation reactions of molecular precursors, typically metal alkoxides [25]. This method facilitates excellent compositional control and homogeneous mixing at molecular levels, producing materials with high surface area and porosity ideal for photocatalytic applications. Hydrothermal and solvothermal methods utilize heated solvent systems at elevated pressures in sealed vessels to facilitate chemical reactions and crystal growth [25] [10]. These approaches enable the synthesis of highly crystalline nanomaterials with controlled morphologies without requiring post-synthesis calcination. Chemical precipitation involves the controlled initiation of supersaturation conditions in solution to trigger the nucleation and growth of solid particles from dissolved precursors [26]. While relatively simple and scalable, precipitation methods may require capping agents to control particle size, which can potentially block active sites on photocatalyst surfaces.

A significant advancement in bottom-up synthesis is the emergence of green synthesis approaches utilizing biological organisms or plant extracts as reducing and stabilizing agents [23] [26]. These environmentally benign methods operate under mild conditions without requiring toxic chemicals, and evidence suggests they can produce photocatalysts with enhanced performance due to inherent functionalization with biomolecules [23]. For instance, biosynthesis using bacteria, fungi, or plant extracts has yielded metal and metal oxide nanoparticles with improved catalytic activity and stability compared to conventionally synthesized counterparts [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Photocatalyst Synthesis Methods

| Synthesis Method | Approach | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Common Photocatalysts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball Milling | Top-down | Simple, scalable, cost-effective | Surface defects, contamination, broad size distribution | Metal oxides, composite materials |

| Laser Ablation | Top-down | High purity, no chemical precursors | Specialized equipment, energy intensive | Noble metals, metal oxides |

| Sputtering | Top-down | Uniform films, precise thickness control | Vacuum requirements, limited to substrates | TiO₂, WO₃, ZnO thin films |

| Sol-Gel | Bottom-up | High homogeneity, controlled porosity | Shrinkage, long processing times | TiO₂, ZnO, SiO₂ composites |

| Hydrothermal/Solvothermal | Bottom-up | High crystallinity, morphology control | Pressure/temperature safety concerns | Nanorods, nanowires, hierarchical structures |

| Green Synthesis | Bottom-up | Environmentally friendly, biocompatible | Standardization challenges, variable yields | Ag, Au, NiO, ZnO nanoparticles |

Performance Comparison of Synthesis Approaches

Structural and Photocatalytic Properties

The selection between top-down and bottom-up approaches significantly influences critical structural characteristics that govern photocatalytic performance. Bottom-up synthesis typically yields materials with superior control over crystal structure, fewer structural defects, more uniform particle size distribution, and higher specific surface area [11]. These characteristics translate directly to enhanced photocatalytic activity, as demonstrated in comparative studies of nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiO-NPs) where biologically synthesized (bottom-up) specimens exhibited significantly better performance than their chemically synthesized counterparts [26]. The biosynthesized NiO-NPs achieved 90% decolorization of methylene blue within just 1 minute, while chemically synthesized nanoparticles required 5 minutes for comparable degradation [26]. Similarly, for 4-nitrophenol degradation, the biosynthesized NiO-NPs reached 65% decolorization in 25 minutes, outperforming chemically synthesized variants [26].

Green bottom-up methods particularly excel in producing photocatalysts with enhanced surface properties and functionalization. The involvement of biological molecules during synthesis can result in nanoparticles with inherent organic functional groups that potentially improve interaction with pollutant molecules and facilitate charge transfer processes [23] [26]. This advantage manifests clearly in wastewater treatment applications, where biogenically synthesized NiO-NPs demonstrated significantly greater efficacy in real wastewater samples, decolorizing 84.8% of Reactive Black-5 compared to 67.2% by chemically synthesized NPs, and removing 62.4% of chemical oxygen demand (COD) versus 57.1% for conventional materials [26].

Environmental and Economic Considerations

Beyond immediate photocatalytic performance, synthesis approaches differ substantially in their environmental footprint and economic viability. Bottom-up green synthesis methods offer notable advantages in sustainability by utilizing biological resources instead of hazardous chemicals, operating under milder temperature and pressure conditions, and generating fewer harmful byproducts [23] [26]. The inherent environmental benefits of these approaches align with the principles of green chemistry and sustainable nanotechnology. Recent advancements have further improved sustainability through the utilization of waste-derived sources for photocatalyst synthesis, such as the fabrication of Co₃O₄ nanoparticles from discarded batteries [10].

Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies provide quantitative insights into the environmental impacts of different synthesis pathways. Research on TiO₂-carbon dots nanocomposites revealed that composites with superior photocatalytic performance typically associated with optimized bottom-up synthesis routes also demonstrated lower environmental impacts across multiple categories [27]. Notably, the TiO₂ source constituted the most critical parameter determining environmental impact, highlighting the importance of precursor selection in sustainable photocatalyst design [27].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Photocatalysts Synthesized via Different Approaches

| Photocatalyst | Synthesis Method | Approach | Target Pollutant/Reaction | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiO-NPs | Biological (Pseudochrobactrum sp.) | Bottom-up | Methylene blue degradation | 90% decolorization in 1 min | [26] |

| NiO-NPs | Chemical precipitation | Bottom-up | Methylene blue degradation | 90% decolorization in 5 min | [26] |

| NiO-NPs-B | Biological | Bottom-up | Reactive Black-5 (wastewater) | 84.8% decolorization, 62.4% COD removal | [26] |

| NiO-NPs-C | Chemical | Bottom-up | Reactive Black-5 (wastewater) | 67.2% decolorization, 57.1% COD removal | [26] |

| Co₃O₄ | Waste-derived (batteries) | Bottom-up | Methylene blue degradation | Complete degradation in 3 h (solar light) | [10] |

| Pt/C | Polyol process | Bottom-up | Ethanol electrooxidation | Specific activity: 0.85 mA/cm² | [8] |

| Pt/C | Electrochemical dispersion | Top-down | Ethanol electrooxidation | Specific activity: 0.82 mA/cm² | [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Bottom-Up Synthesis: Biological Fabrication of NiO Nanoparticles

The biological synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles using Pseudochrobactrum sp. C5 exemplifies a bottom-up approach leveraging microbial capabilities [26]. The experimental protocol initiates with inoculating 50 mL of nutrient broth medium with the bacterial strain and incubating overnight at 28°C with 150 rpm shaking in darkness. Following this growth phase, 2 mL of 0.003 M nickel chloride solution is introduced to the culture, with subsequent shaking at 150 rpm for 2 hours at 28°C. Nanoparticle formation is visually indicated by a color transition from light green to intense green over 72 hours. The resulting nanoparticles are then collected via centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 minutes, followed by three washing cycles with double-distilled water and ethanol. The purified precipitate is oven-dried at 85°C before calcination in a muffle furnace at 700°C for 7 hours, ultimately yielding powdered NiO nanoparticles [26].

Representative Top-Down Synthesis: Electrochemical Dispersion for Pt/C Catalysts

The electrochemical dispersion pulse alternating current (EDPAC) method demonstrates a top-down approach for fabricating Pt/C electrocatalysts [8]. This procedure begins with suspending Vulcan XC-72 carbon support in 2M NaOH aqueous solution at a concentration of 2 g/L. Two platinum foil electrodes (6 cm² surface area each) are immersed in the vigorously stirred suspension, which is maintained at 45-50°C throughout the synthesis. A pulsed alternating current with density 1 A/cm² at 50 Hz frequency is applied, facilitating electrochemical dispersion of platinum from the electrodes into nanoparticles that deposit onto the carbon support. The metal loading within the catalyst is precisely controlled by adjusting the synthesis duration. Upon completion, the suspension undergoes filtration and rinsing with distilled water until neutral pH is achieved. The resulting electrocatalyst powder is dried at 75°C until constant mass is attained [8].

Computational and Theoretical Modeling Approaches

Computational methods have emerged as powerful tools for understanding photocatalytic mechanisms and guiding material design. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations have proven particularly valuable for elucidating electronic structures, identifying active sites, and predicting band gap energies of photocatalytic materials [28] [24]. For instance, DFT simulations have confirmed higher electrostatic potential in the presence of hydroxyl radicals, explaining the enhanced degradation efficiency observed with certain photocatalysts [28]. Multiscale modeling approaches that combine different computational techniques hierarchically represent the future direction for modeling complex nano-photocatalysts, enabling accurate predictions while managing computational resources efficiently [24].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into photocatalyst design represents a cutting-edge development in the field [23]. These computational approaches enable rapid screening of potential photocatalytic materials based on structure-activity relationships, prediction of synthesis parameters for desired properties, and optimization of photocatalytic systems for specific applications. Machine learning algorithms can identify non-intuitive correlations between synthesis conditions, material characteristics, and photocatalytic performance that might escape conventional experimental approaches, potentially accelerating the development of next-generation photocatalysts [23].

Diagram 1: Decision pathway for selecting photocatalyst synthesis methods based on application requirements and desired material properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Photocatalyst Synthesis and Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Representative Examples | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) Precursors | Wide-bandgap semiconductor photocatalyst | Titanium isopropoxide, Titanium butoxide, TiO₂ nanoparticles | Crystalline phase (anatase/rutile) affects activity; often requires doping for visible light response [25] |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Precursors | Alternative to TiO₂ with similar bandgap | Zinc acetate, Zinc nitrate, ZnO nanoparticles | Prone to photocorrosion; surface modification enhances stability [25] |

| Nickel Salts | Precursors for NiO nanoparticle synthesis | Nickel chloride, Nickel nitrate | NiO bandgap (3.2-4.0 eV) suitable for photocatalysis; biological synthesis enhances activity [26] |

| Cobalt Salts | Precursors for Co₃O₄ synthesis | Cobalt nitrate, Cobalt chloride | Co₃O₄ narrow bandgap (1.5-2.4 eV) enables visible light absorption [10] |

| Carbon Supports | Enhancing electron transfer and stability | Vulcan XC-72R, Graphene oxide, Carbon dots | Improve charge separation; carbon dots enhance visible light absorption in composites [27] [8] |

| Biological Agents | Green synthesis facilitators | Plant extracts, Bacteria (e.g., Pseudochrobactrum sp.), Fungi | Provide reducing and capping agents; eliminate need for harsh chemicals [23] [26] |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Controlling morphology and porosity | CTAB, P123, F127 | Template-assisted synthesis for hierarchical structures with high surface area [25] |

| Dopants | Modifying band structure and extending absorption | Noble metals (Pt, Ag), Transition metals (Fe, Cu), Non-metals (N, S) | Reduce charge recombination; create intermediate energy levels [25] [10] |

The comparative analysis of top-down and bottom-up synthesis approaches for photocatalytic materials reveals a complex landscape where each methodology offers distinct advantages depending on application requirements. Bottom-up approaches generally provide superior control over material architecture at the nanoscale, resulting in photocatalysts with optimized properties for enhanced performance, particularly in environmental remediation applications [26] [25]. The emergence of green synthesis methods within this category further strengthens the sustainability profile of photocatalyst fabrication while demonstrating competitive or even superior performance compared to conventional chemical routes [23] [26]. Conversely, top-down methods maintain relevance for specific applications requiring scalability, direct patterning, or integration with existing device architectures [11] [8].

Future developments in photocatalyst fabrication will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both methodologies, such as using top-down techniques to create substrate structures followed by bottom-up deposition of active components. The increasing integration of computational guidance, through both first-principles calculations and machine learning approaches, promises to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel photocatalytic materials [23] [24]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on circular economy principles is driving innovation in waste-derived photocatalyst precursors and scalable green synthesis routes that minimize environmental impact while maintaining high performance [10]. As these trends converge, the next generation of photocatalytic materials will likely exhibit enhanced complexity through multi-component architectures precisely engineered across multiple length scales to maximize solar energy conversion efficiency.

Synthesis Techniques and Functional Applications in Energy and Biomedicine

The strategic design of photocatalytic materials is pivotal for enhancing the efficiency of solar-driven processes, from environmental remediation to renewable energy generation. Within this context, the synthesis paradigm is broadly divided into top-down and bottom-up approaches. Top-down methods involve the physical or chemical breakdown of bulk materials into nanostructures, often facing limitations in achieving precise atomic-level control and uniformity [8] [1]. In contrast, bottom-up synthesis constructs nanomaterials atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule, allowing for unparalleled command over size, shape, composition, and surface properties [1]. This precision is critical for tailoring the electronic structure, charge carrier dynamics, and surface reactivity of photocatalysts. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three pivotal bottom-up methodologies: the polyol process, hot-injection, and self-templating synthesis. We objectively evaluate their performance in producing advanced photocatalytic materials, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and development professionals in the field.

The three bottom-up methods—polyol, hot-injection, and self-templating—operate on distinct physicochemical principles for nanomaterial construction. The following diagram delineates their fundamental operational workflows, highlighting key differences in precursor introduction, reaction control, and final material formation.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Photocatalytic Materials

The choice of synthesis methodology profoundly impacts the structural, optical, and electronic properties of the resulting photocatalytic material, which in turn dictates its performance in applications such as dye degradation, CO₂ reduction, and hydrogen evolution. The following table summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of nanomaterials synthesized via these three bottom-up routes, drawing from experimental findings in the literature.

| Synthesis Method | Typical Photocatalytic Material | Key Structural Features | Performance Metrics (Experimental) | Bandgap Tuning Range | Primary Advantages for Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|