Strategies for Enhancing Photocatalytic Stability in Inorganic Compounds: From Material Design to Application

This article addresses the critical challenge of photocatalytic instability in inorganic compounds, a major bottleneck for their practical application in environmental remediation and energy conversion.

Strategies for Enhancing Photocatalytic Stability in Inorganic Compounds: From Material Design to Application

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of photocatalytic instability in inorganic compounds, a major bottleneck for their practical application in environmental remediation and energy conversion. Targeting researchers and scientists, we explore the fundamental mechanisms behind photocorrosion and material degradation. The scope systematically progresses from analyzing root causes to presenting advanced stabilization strategies like component engineering, heterojunction construction, and hybrid material design. We provide a comparative analysis of material performance and stability, alongside troubleshooting methodologies for optimizing photocatalytic systems. The synthesis of these insights aims to guide the development of robust, high-performance photocatalysts for sustainable technological applications.

Understanding Photocatalytic Instability: Core Mechanisms and Material Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary intrinsic factors that cause inorganic photocatalysts to degrade or lose activity? The main intrinsic factors are photocorrosion and charge carrier recombination [1]. Photocorrosion is a self-oxidation or reduction process where the photocatalyst itself is degraded by the photogenerated holes or electrons it produces. Furthermore, the rapid recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes means they are unavailable for the desired catalytic reactions, converting their energy instead into heat and contributing to structural instability over time [2] [1].

Q2: Why are some inorganic photocatalysts, like TiOâ‚‚, only activated by UV light, and how does this relate to their stability? Materials like TiOâ‚‚ have a wide bandgap energy, meaning the energy difference between their valence band and conduction band is large [3] [1]. Only high-energy photons from the UV spectrum can excite electrons across this gap. While UV activation itself doesn't directly cause degradation, the high-energy photons can generate highly reactive charge carriers that may participate in corrosive side reactions. Furthermore, the limited use of visible light (the majority of solar spectrum) restricts practical application but is not a direct degradation mechanism [1].

Q3: What is the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in catalyst degradation? While ROS like hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide anions (O₂•â») are essential for degrading organic pollutants, they are highly reactive and can also attack the crystal structure of the photocatalyst itself [4] [1]. This oxidative attack can lead to the dissolution of metal ions from the catalyst's surface, creating defects and vacancies that degrade its performance over multiple cycles [1].

Q4: How does the pH of the reaction medium influence photocatalyst stability? The solution's pH significantly affects the surface charge of the photocatalyst and the potential generation of ROS [1]. Operating at extremely high or low pH levels can lead to the dissolution of the catalyst material. For example, very low pH can protonate surface groups and leach metal cations, while very high pH can cause hydrolysis and structural breakdown, negatively affecting both the catalyst and its long-term efficiency [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Degradation Issues and Solutions

The following table summarizes the core problems, their underlying mechanisms, and practical solutions to mitigate the degradation of inorganic photocatalysts.

| Problem | Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Experimental Parameters to Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photocorrosion [1] | Photogenerated holes directly oxidize the catalyst material instead of the target pollutant. | Use oxide-based semiconductors (e.g., TiOâ‚‚, ZnO) for their superior stability, or create core-shell structures to protect the active site [1]. | Measure metal ion leaching in solution via ICP-MS; track catalyst mass loss over cycles. |

| Charge Carrier Recombination [2] [1] | Photogenerated electrons and holes recombine rapidly, releasing energy as heat and promoting side reactions. | Dope the catalyst with metal/non-metal elements or construct heterojunctions with other materials to enhance charge separation [2] [1]. | Perform photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy: a lower PL intensity indicates suppressed recombination. |

| Surface Deactivation [5] | Strong adsorption of intermediate products or inorganic ions blocks active sites. | Incorporate sacrificial reagents (e.g., hole scavengers like methanol) or implement periodic thermal treatment to burn off residues [5]. | Analyze surface composition with XPS; measure BET surface area to detect pore blocking. |

| Structural Instability in Solution [1] | Dissolution of the catalyst in acidic or alkaline reaction media. | Control the reaction pH to remain near the catalyst's point of zero charge (PZC) and use immobilized catalyst systems on supports [1]. | Monitor solution pH shift during reaction; analyze catalyst morphology via SEM after cycles. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Photocatalyst Stability

Protocol 1: Standardized Cycling Test for Reusability

This protocol assesses a photocatalyst's longevity and resistance to deactivation.

- Reaction Setup: Conduct a standard photocatalytic degradation experiment (e.g., of a dye like Methylene Blue) under fixed light intensity, catalyst loading, and pollutant concentration [6].

- Recovery Phase: After each reaction cycle (e.g., 60-90 minutes), separate the photocatalyst from the solution via centrifugation or filtration.

- Washing and Reuse: Wash the recovered catalyst gently with deionized water and ethanol to remove any surface residues, then dry it at a moderate temperature (e.g., 60°C).

- Repetition and Analysis: Reuse the same catalyst batch for multiple identical cycles. After each cycle, measure the degradation efficiency and analyze the catalyst using techniques like XRD and SEM to detect changes in crystal structure and morphology [5].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Mineralization and Harmful By-products

This protocol evaluates if the catalyst completely mineralizes pollutants or produces toxic intermediates.

- Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Analysis: For a target organic pollutant, measure the TOC of the solution at regular intervals during irradiation. The mineralization efficiency is calculated as:

(1 - TOC_t / TOC_0) × 100%, whereTOC_0andTOC_tare the TOC values at initial and time t, respectively [5]. - By-product Identification: Use analytical techniques such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify and quantify intermediate compounds formed during the reaction [5].

- Assessment: A stable and effective catalyst will show a TOC removal trend that correlates with the parent pollutant's disappearance and a minimal accumulation of harmful intermediates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Photocatalysis Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | A benchmark wide-bandgap semiconductor for UV-driven photocatalysis; used as a control and a base for modification [4] [5]. | Exists in crystalline phases (Anatase, Rutile); phase composition significantly impacts activity. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | An alternative wide-bandgap semiconductor to TiOâ‚‚, known for its rich defect chemistry and morphology variants [4]. | Prone to photocorrosion in aqueous solutions, limiting its long-term stability [1]. |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Electron donors (e.g., Methanol) or acceptors used to scavenge holes or electrons, thereby studying charge transfer pathways and suppressing recombination/corrosion [5]. | Their use provides mechanistic insight but may not represent conditions for practical pollutant mineralization. |

| Point Defect Agents | Dopants (e.g., Nitrogen, Iron) introduced into a semiconductor lattice to create energy levels within the bandgap, enabling visible light absorption [1]. | Excessive doping can become recombination centers, counterproductively reducing efficiency. |

| Heterojunction Partners | Materials like g-C₃N₄ or other semiconductors coupled to form interfaces that enhance spatial separation of charge carriers [2] [4]. | The band alignment between the two materials is critical for directing electron-hole flow. |

| ETHOXY(ETHYL)AMINE | ETHOXY(ETHYL)AMINE, CAS:4747-28-8, MF:C4H11NO, MW:89.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethyl L-histidinate | Ethyl L-histidinate|RUO | Ethyl L-histidinate is an L-histidine ester for biochemical research. It serves as a key intermediate. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

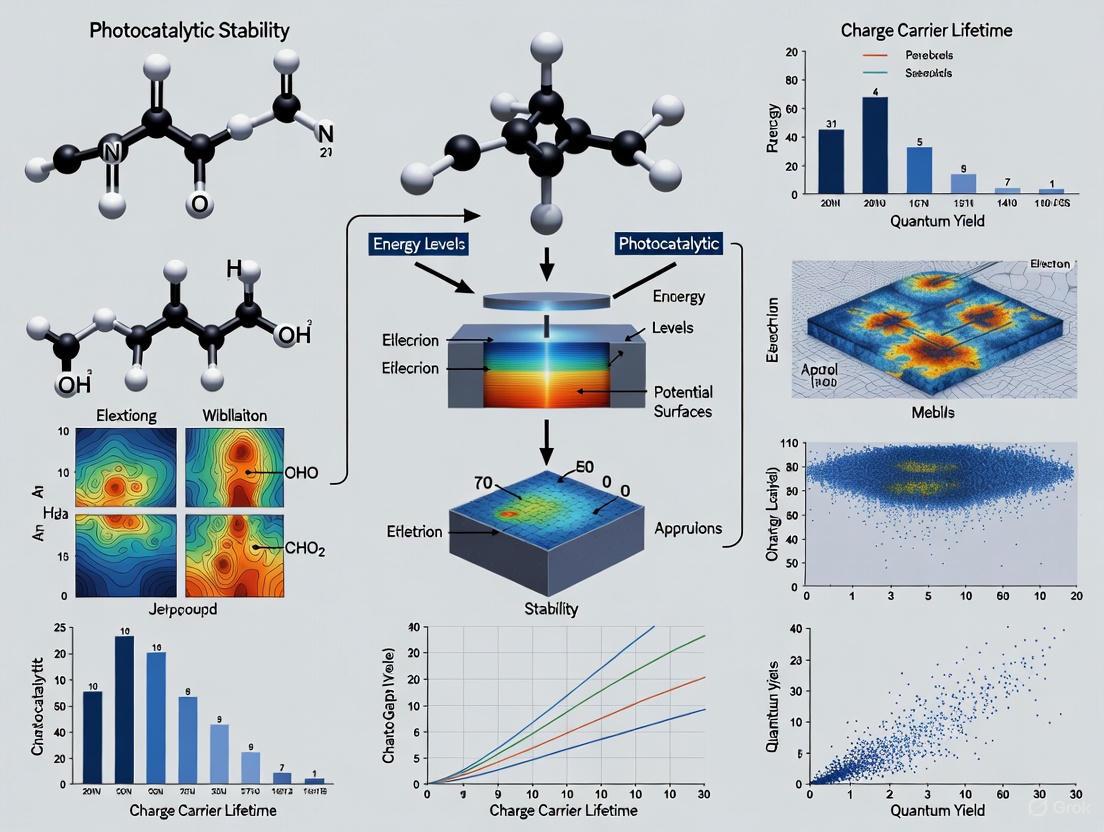

Visualization of Degradation Mechanisms and Workflows

Degradation Pathways of Inorganic Photocatalysts

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms that lead to the degradation of inorganic photocatalysts.

Diagram 1: Key pathways leading to the degradation and deactivation of inorganic photocatalysts, including photocorrosion, reactive oxygen species (ROS) attack, and charge carrier recombination.

Experimental Workflow for Stability Assessment

This workflow outlines a standard procedure for evaluating the stability and reusability of a photocatalyst in the lab.

Diagram 2: A cyclic experimental workflow for assessing photocatalyst stability and reusability, involving performance testing and material characterization.

This technical support center provides a focused troubleshooting guide for researchers grappling with the primary degradation pathways that compromise the stability and efficiency of inorganic photocatalysts. Framed within a broader thesis on advancing photocatalytic stability, this resource directly addresses the critical challenges of photocorrosion, metal leaching, and phase transformation. Each section below outlines specific issues, proposed mechanisms, and validated experimental protocols to diagnose, mitigate, and prevent these failure modes, enabling more robust and reproducible research outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guide: Key Degradation Pathways

Photocorrosion

Problem Statement: Researchers observe a significant and irreversible drop in photocatalytic activity over successive reaction cycles, often accompanied by visible changes to the photocatalyst powder, such as discoloration or dissolution.

Underlying Mechanism: Photocorrosion is a light-induced self-oxidation or self-reduction of the photocatalyst. For n-type semiconductors like ZnO, the primary mechanism involves the oxidation of the material itself by photogenerated holes. These holes, which are intended to oxidize the target pollutant or water, instead react with the semiconductor lattice (e.g., ZnO + 2h⺠→ Zn²⺠+ ½O₂), leading to the dissolution of metal ions and destruction of the active material [7].

Diagnosis and Analysis Protocols:

- Controlled Irradiation Test: To isolate the effect of light from the chemical reaction, suspend the photocatalyst in the pure solvent (e.g., tap water) without any pollutants. Expose it to the standard light source for set intervals (e.g., 2, 4, 6, 8 hours). After each interval, recover the powder and test its activity in a standard degradation reaction (e.g., methylene blue degradation). A steady decline in activity confirms light-induced corrosion [7].

- Ion Leaching Analysis: Use techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) spectroscopy to analyze the reaction solution for dissolved metal ions (e.g., Zn²âº) after illumination. An increasing concentration of metal cations confirms lattice destruction [7].

- Surface Characterization: Employ X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to analyze the surface chemical states of the photocatalyst before and after use. Changes in oxidation states can indicate surface oxidation or reduction.

Prevention and Mitigation Strategies:

- Surface Functionalization: Hybridize the inorganic photocatalyst with organic materials or carbon nanostructures.

- Example: Coating ZnO with polyaniline (PANI) or graphene. The organic layer acts as a sink for photogenerated holes, diverting them from the ZnO lattice and facilitating their transfer to the target pollutant. This strategy has been shown to inhibit corrosion and improve stability over multiple cycles [7].

- Heterojunction Construction: Couple the corrosion-prone photocatalyst with another semiconductor to create a heterojunction. Proper band alignment can drive the photogenerated holes away from the susceptible material, thereby protecting it [8].

Phase Transformation

Problem Statement: A photocatalyst, particularly one calcined at high temperature or operated under strenuous conditions, loses activity due to an irreversible change in its crystal structure, such as the transformation of the highly active anatase phase of TiOâ‚‚ to the less active rutile phase.

Underlying Mechanism: Phase transformation is a thermally driven process where a metastable crystal structure (e.g., anatase TiOâ‚‚) transforms into a more thermodynamically stable one (e.g., rutile TiOâ‚‚). This transformation is often accelerated at high calcination temperatures used in catalyst synthesis or during exothermic reactions. The rutile phase typically exhibits lower photocatalytic activity due to faster charge carrier recombination, leading to a permanent loss of performance [9].

Diagnosis and Analysis Protocols:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): The primary tool for diagnosing phase changes. Compare the XRD patterns of fresh and spent catalysts. The appearance of new diffraction peaks (e.g., the primary rutile peak at ~27.5° 2θ) and the diminishment of anatase peaks confirm the transformation [9].

- Raman Spectroscopy: This technique can provide complementary evidence for phase changes based on the vibrational fingerprints of different crystal phases.

Prevention and Mitigation Strategies:

- Use of Crystalline Phase Inhibitors: Incorporate inhibitors during the synthesis to stabilize the desired phase.

- Protocol: During the sol-gel synthesis of TiO₂ using tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT), use oxalic acid (OA) as an environmentally friendly inhibitor. A higher molar ratio of OA to TBOT (e.g., 25:10 vs. 0:10) effectively suppresses the anatase-to-rutile transformation even at high calcination temperatures (e.g., 650°C). This method also reduces crystal size and improves charge separation, leading to a tenfold increase in degradation rate constant [9].

- Procedure:

- Prepare Solution A: TBOT in ethanol (0.5 M).

- Prepare Solution B: A mixture of 0.5 M OA aqueous solution and water.

- Slowly add Solution B to Solution A in an ice-water bath (3-5°C) with stirring for 3 hours.

- Age the mixture at 90°C for 8 hours, then at room temperature for 20 hours.

- Dry the collected milky suspension at 80°C for 6 hours to obtain the precursor.

- Calcine the precursor powder in air at the desired temperature [9].

Metal Leaching

Problem Statement: In composite or doped photocatalysts, active metal sites (e.g., cocatalysts or dopants) are lost into the solution, leading to deactivation and potential contamination of the reaction products.

Underlying Mechanism: Leaching occurs when metal species, often not fully integrated into the stable host lattice, are dissolved by the reaction medium. This can be driven by acidic/alkaline conditions or complexing agents in the solution. Leaching is a common failure mode in photocatalysts designed for selective processes, such as the recovery of valuable metals [10].

Diagnosis and Analysis Protocols:

- Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Analysis: The definitive method for quantifying leaching. Analyze the post-reaction supernatant after removing the catalyst particles. Measure the concentration of the critical metal(s) to determine the leaching rate [10].

- Reusability Test: A simple but effective indicator. Recycle the photocatalyst for multiple runs under identical conditions. A steady activity drop coupled with the detection of metals in the solution points to leaching as a primary deactivation pathway [10].

Prevention and Mitigation Strategies:

- Stable Catalyst Design: Develop photocatalysts where the active metal is strongly bonded within the structure.

- Case Study: MoSâ‚‚ has been demonstrated as a stable and reusable photocatalyst for the selective leaching of Li from spent batteries. Repeated leaching and light irradiation experiments confirmed its excellent reusability with negligible MoSâ‚‚ decomposition, underscoring its robust structure [10].

- Optimization of Reaction Conditions: Fine-tune parameters such as pH, temperature, and catalyst-to-reactant ratio to minimize the thermodynamic and kinetic drivers for metal dissolution.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I quickly determine if my catalyst's deactivation is due to photocorrosion or simple fouling by reaction by-products? A1: A simple solvent wash (e.g., with water or ethanol) and subsequent activity test can distinguish between the two. If activity is restored, the issue was likely surface fouling. If activity remains low, the degradation is likely permanent, pointing to photocorrosion or phase transformation. Further characterization via XRD and ICP is then required [7].

Q2: Are there any "green" or sustainable methods to synthesize stable photocatalysts resistant to these degradation pathways? A2: Yes. Recent research focuses on using natural extracts and mild acids. For example, Punica granatum (pomegranate) extract can be used as a capping and reducing agent to synthesize ZnFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ nanoparticles, minimizing hazardous waste. Furthermore, oxalic acid, a natural and mild acid, can effectively control the TiOâ‚‚ phase transformation instead of harsher acids like hydrochloric or sulfuric acid [11] [9].

Q3: What is the most critical factor to control during synthesis to ensure the thermal stability of a TiOâ‚‚ photocatalyst? A3: Controlling the crystalline phase is paramount. The use of inhibitors like oxalic acid during the hydrolysis of the titanium precursor (e.g., TBOT) is a critical step. This not only stabilizes the active anatase phase against transformation to rutile at high temperatures but also enhances the surface area and charge separation properties [9].

| Degradation Pathway | Photocatalyst | Key Experimental Findings | Quantified Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photocorrosion | ZnO | Photocatalytic efficiency dropped after 2-4h UV pre-irradiation in water, but showed unexpected recovery after 8h, linked to surface restructuring. | Activity recovery to ~90% after 8h UV aging [7]. | [7] |

| Phase Transformation | TiOâ‚‚ | Oxalic acid (OA) inhibits anatase-to-rutile transformation. Higher OA:TBOT ratios yield smaller crystallites and higher activity. | Rate constant for CT650-R25 was 10x higher than CT650-R0 [9]. | [9] |

| Leaching & Stability | MoSâ‚‚ | Used for selective Li leaching from batteries. Demonstrated excellent reusability with minimal catalyst decomposition. | Li leaching rate >99% with Fe/P leaching <20%; MoSâ‚‚ was reusable [10]. | [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Oxalic Acid (OA) | A mild, natural inhibitor that controls crystal growth and phase transformation in metal oxides. | Stabilizing the anatase phase of TiOâ‚‚ during high-temperature calcination [9]. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | A conducting polymer used to create a protective organic layer on inorganic catalysts. | Coating ZnO to divert photogenerated holes and suppress photocorrosion [7]. |

| Molybdenum Disulfide (MoSâ‚‚) | A stable, layered semiconductor photocatalyst resistant to leaching in acidic or oxidative environments. | Selective photocatalytic leaching of lithium from spent batteries [10]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBHâ‚„) | A reducing agent used in material synthesis and for inducing phase transformations. | Facilitating the in-situ phase transformation from BiOCOOH to (BiO)â‚‚COâ‚‚ on carbon dots [12]. |

| Bromoxanide | Bromoxanide|CAS 41113-86-4|Research Chemical | Get Bromoxanide (CAS 41113-86-4) for your research. This high-purity compound is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| Myrtanyl acetate | Myrtanyl Acetate|29021-36-1|Research Chemical | Myrtanyl acetate is a bicyclic monoterpene ester for research, notably in antimicrobial and neuroprotective studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Stability Enhancement Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing the key degradation pathways discussed in this guide.

Stability Enhancement Workflow: A decision tree for diagnosing photocatalyst deactivation and selecting appropriate mitigation strategies.

Charge Carrier Dynamics in Hybrid Systems

The diagram below illustrates how combining organic and inorganic materials can mitigate degradation by optimizing the flow of photogenerated charges.

Hybrid System Charge Management: How charge transfer in hybrid systems suppresses degradation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my photocatalyst unstable under operational conditions?

Problem: Rapid degradation or deactivation of a photocatalytic material, such as ZnWO₄ or Bi₂CrO₆, during visible light irradiation.

Explanation: Instability often originates from the thermodynamic metastability of the material's surface. Under operational conditions (specific temperature and chemical potential of oxygen), the surface can reconstruct into different terminations. If the termination present is not thermodynamically favored for the given environment, it will seek a lower-energy state, leading to surface changes that poison active sites or promote corrosion [13] [14].

Solution:

- Action: Determine the thermodynamically stable surface phase for your specific operational conditions (temperature and oxygen partial pressure) using computational phase diagrams [14] [15].

- Verification: Synthesize the material under conditions predicted to stabilize the desired surface termination. Characterize the resulting surface using techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to confirm its composition and stability.

Why does my material have low photocatalytic activity despite a narrow band gap?

Problem: A semiconductor like Bi₂CrO₆ has a narrow, visible-light-absorbing band gap (~2.00 eV) but shows poor charge separation and low photocatalytic efficiency [15].

Explanation: A narrow band gap alone does not guarantee high activity. The problem may lie in the electronic structure of the surface. Unfavorable surface states can act as recombination centers, trapping photogenerated electrons and holes and causing them to recombine before they can participate in surface reactions [14] [15].

Solution:

- Action: Use computational methods (e.g., Density Functional Theory with HSE06 functional) to calculate the electronic density of states for the specific surface termination. Look for mid-gap states that indicate recombination centers [14].

- Verification: Employ surface-sensitive spectroscopy techniques to validate the computational predictions. Focus on synthesizing surface terminations that calculations show have a clean band gap without mid-gap states.

How can I engineer a more stable and active band structure?

Problem: The inherent bulk band structure of a photocatalyst is not optimal for the desired redox reactions (e.g., water splitting), leading to instability or low efficiency.

Explanation: The positions of the Valence Band Maximum (VBM) and Conduction Band Minimum (CBM) relative to the redox potentials of the target reactions are critical. If the CBM is not more negative than the Hâº/Hâ‚‚ reduction potential, or the VBM is not more positive than the Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O oxidation potential, the reactions will not proceed. Surface termination can significantly shift these band edge positions [14].

Solution:

- Action: Calculate the band edge positions of different thermodynamically stable surface terminations. For instance, the Wâ‚‚Oâ‚„-Zn₈Wâ‚â‚€O₃₆ termination of ZnWOâ‚„(100) has been shown to have band edges that simultaneously fulfill the requirements for both hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions [14].

- Verification: Select a termination with the appropriate band alignment for your reaction. Experimental synthesis is then guided by the surface phase diagram to achieve that specific termination.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor linking bandgap and photocatalytic stability? The thermodynamic stability of the surface termination under reaction conditions is paramount. An unstable surface reconstruction alters the electronic band structure locally, often introducing surface states that promote charge-carrier recombination and lead to photocatalytic deactivation. The surface stability is a function of the oxygen chemical potential and temperature [14] [15].

Q2: How can I computationally predict the stable surface structure of my photocatalyst? Using Density Functional Theory (DFT), you can calculate the surface Gibbs free energy for all possible surface terminations across a range of oxygen and metal chemical potentials. This allows you to construct a surface phase diagram that identifies the most thermodynamically stable termination for any given experimental condition [14] [15].

Q3: My material absorbs visible light well but performance is poor. Is the bandgap the issue? Not necessarily. While a narrow bandgap is needed for visible light absorption, the nature of the gap is crucial. An indirect bandgap leads to low electron-hole pair generation rates. Furthermore, the presence of deleterious surface states within the bandgap can cause rapid recombination of the generated charges, negating the benefit of strong light absorption [16] [15].

Q4: Can surface termination really change the optical properties of a material? Yes. Different surface terminations have distinct atomic arrangements and electronic structures, which can lead to different absorption coefficients. For example, the Wâ‚‚Oâ‚„-Zn₈Wâ‚â‚€O₃₆ termination of ZnWOâ‚„ exhibits stronger absorption in the visible region than the bulk material [14].

Data Presentation

Bandgap and Stability Properties of Selected Photocatalysts

The following table summarizes key electronic and stability properties from recent research, highlighting how surface engineering impacts performance.

| Material & Surface | Band Gap (eV) | Bandgap Type | Key Stability Finding | Photocatalytic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnWOâ‚„ Bulk [14] | ~3.1 (PBE) | n/a | Baseline reference | Limited visible light activity. |

| ZnWOâ‚„(100) - Wâ‚‚Oâ‚„ Termination [14] | HSE06 Functional | Surface states in gap | Stabilized under specific Oâ‚‚ conditions | Stronger visible absorption; Band edges suit HER/OER. |

| Bi₂CrO₆ Bulk [15] | ~2.00 | Direct | Inherently narrow gap | Good visible light response. |

| Bi₂CrO₆(001) - O-Bi Termination [15] | DFT Calculated | n/a | Stable in O-rich conditions | Poor charge separation is a key challenge. |

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase) [15] | 3.20 | Indirect | High stability but wide gap | UV-active only; benchmark material. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Stable Surface Phases via DFT

Methodology: This protocol outlines the computational steps to establish a surface phase diagram, guiding the synthesis of stable photocatalysts [14] [15].

Bulk Structure Optimization:

- Obtain the crystal structure from databases or experimental refinement.

- Fully optimize the bulk unit cell's geometry (lattice parameters and atomic positions) using a DFT functional (e.g., GGA-PBE).

Surface Slab Model Generation:

- Cleave the optimized bulk structure along the desired crystallographic plane (e.g., (100), (001)).

- Generate all symmetrically inequivalent surface terminations.

- Create a symmetric slab model with sufficient thickness (e.g., 6-10 atomic layers) and a vacuum layer of >15 Ã… to separate periodic images.

Surface Energy Calculation:

- Geometrically optimize the atomic positions of all atoms in the slab model.

- For each termination, calculate the surface Gibbs free energy (γ) using the formula:

γ = [G_slab - N_{Bi}*μ_{Bi} - N_{Cr}*μ_{Cr} - N_O*μ_O] / 2AwhereG_slabis the slab's total free energy,N_iis the number of atoms of type i in the slab,μ_iis its chemical potential, andAis the surface area [15].

Constructing the Phase Diagram:

- The chemical potentials are constrained by the thermodynamic equilibrium with the bulk phases of the constituents (e.g., Bi₂CrO₆, Bi metal, Cr metal, O₂ gas).

- Vary the oxygen chemical potential (Δμ_O) across its allowed range and calculate the surface energy for each termination at every point.

- The most stable termination at a given (Δμ_O, T) is the one with the lowest surface energy. Plotting this creates the surface phase diagram.

Mandatory Visualization

Surface Stability Determination Logic

Electronic Structure Impact on Photocatalysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material / Reagent | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to model bulk and surface electronic structures, stability, and band edges [14] [15]. | The choice of exchange-correlation functional (e.g., PBE vs. HSE06) is critical for accurate band gap prediction [14]. |

| High-Purity Precursor Salts | Source of metal cations (e.g., Zn²âº, Wâ¶âº, Bi³âº, Crâ¶âº) for the synthesis of photocatalysts like ZnWOâ‚„ and Biâ‚‚CrO₆ [14] [15]. | Purity is essential to avoid unintentional doping, which can introduce recombination centers and alter electronic properties. |

| Controlled Atmosphere Furnace | Enables material synthesis and annealing under precisely controlled oxygen partial pressures (O-rich vs. O-poor conditions) [14]. | Allows experimentalists to target specific regions of the computational surface phase diagram to obtain the desired termination. |

| Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Reactor | Used for the synthesis of crystalline photocatalysts with controlled morphology and exposed crystal facets [15]. | Parameters like temperature, pressure, and pH value influence which thermodynamically stable surface is formed. |

| Hybrid Functional (HSE06) | A more advanced computational method used for post-processing to obtain accurate electronic band structures and band gaps, which are typically underestimated by standard DFT [14]. | Computationally expensive but necessary for reliable prediction of optoelectronic properties. |

| 1,5-Dibromohexane | 1,5-Dibromohexane, CAS:627-96-3, MF:C6H12Br2, MW:243.97 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tixadil | Tixadil, CAS:2949-95-3, MF:C24H25NS, MW:359.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQ and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Why does my CdS photocatalyst lose activity rapidly during hydrogen evolution experiments?

This is a classic sign of photocorrosion [17] [18]. The photocatalytic process itself can break down CdS. A key strategy to mitigate this is constructing a heterojunction to separate the photogenerated charges. For instance, coupling CdS with Sn3O4 to form a heterostructure enhances photocurrent density and directs electron transfer, thereby protecting CdS from being oxidized by the photogenerated holes [17]. Similarly, creating a solid solution like Mn-doped CdS (Mn0.3Cd0.7S) can also significantly improve stability, allowing the catalyst to be reused for multiple cycles with minimal activity loss [18].

Q2: How can I improve the poor visible light absorption of my wide-bandgap TiOâ‚‚ or ZnO catalyst?

A common and effective method is dye sensitization. Natural dyes like anthocyanin (from red water lily) or chlorophyll (from water hyacinth) can be adsorbed onto the TiO2 surface. These dyes absorb visible light and inject excited electrons into the conduction band of TiO2, enabling photocatalytic activity under visible light [19]. Alternatively, forming a heterostructure with a narrow-bandgap semiconductor is another robust strategy. For example, sensitizing ZnO with CdS nanoparticles to create a type-II heterostructure can tune the band gap from 3.78 eV (ZnO) down to 2.8 eV (CdS-ZnO), drastically improving visible light response [20].

Q3: My catalyst shows high initial activity but then deactivates quickly. What could be the cause?

Rapid deactivation can stem from several issues:

- Photocorrosion: As noted in Q1 for CdS [18].

- Ligand or Sensitizer Degradation: In dye-sensitized systems (e.g., catechol-derived complexes on TiO2), the sensitizing molecules can degrade under light, especially in the presence of oxygen and water vapor, leading to a complete loss of visible-light activity [21].

- Poisoning or Fouling: Reaction intermediates or pollutants can accumulate on the active sites, blocking them. A practical solution is to design systems that combine adsorption and photocatalysis, such as a TiO2-clay nanocomposite, where the clay helps concentrate pollutants near the catalyst and may prevent the accumulation of harmful intermediates [22].

Q4: What is a general strategy to simultaneously enhance stability and activity?

Constructing a heterojunction is one of the most powerful approaches. The interface between two semiconductors can create a built-in electric field that drives the rapid separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. This not only increases the number of available charges for the catalytic reaction (enhancing activity) but also reduces the chance that these charges will participate in self-degradation (photocorrosion) of the catalyst, thereby improving stability [17] [23] [20].

Quantitative Performance Data of Stability-Enhanced Photocatalysts

The following table summarizes experimental data from recent studies on modified semiconductor photocatalysts, highlighting the stability and performance improvements achieved through various strategies.

| Photocatalyst System | Modification Strategy | Application | Key Performance Metric | Stability & Reusability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdS-Sn3O4 | Heterojunction Construction | Degradation of antibiotics & dyes | Enhanced photocurrent density; 2.25 eV bandgap | Mitigated photocorrosion of CdS; Improved charge separation | [17] |

| ZnO/Zn3As2/SrTiO3 | Heterojunction & Protective Layer | Overall Water Splitting | N/A | >5 cycles (15 hours) without significant decay; protects Zn3As2 | [23] |

| Cd(OH)2/CdS (5%) | 2D/2D Cocatalyst Loading | H2 Generation & Cr(VI) Reduction | H2 rate: 3475 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ (6.3x CdS) | Exceptional stability over multiple cycles | [24] |

| Mn0.3Cd0.7S | Elemental Doping (Solid Solution) | H2 Production from Wastewater | H2 rate: 10937.3 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ (6.7x CdS) | Good reusability performance | [18] |

| TiO2-Clay (70:30) | Nanocomposite & Immobilization | Dye (BR46) Degradation | 98% dye removal; 92% TOC reduction | >90% efficiency after 6 cycles | [22] |

| CdS NP-ZnO NF | Type-II Heterostructure | Dye (Methylene Blue) Degradation | ~95% degradation within 28 min | Enhanced charge separation reduces recombination | [20] |

| Anthocyanin-Sensitized TiO2 | Natural Dye Sensitization | Dye (Methylene Blue) Degradation | 75% degradation under visible light | >80% activity retained after 5 cycles | [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a CdS-Sn3O4 Heterojunction for Enhanced Photostability

This method combines mechanochemical and mixed-heating techniques to mitigate CdS photocorrosion [17].

- Synthesis of CdS: Prepare CdS using a mechanochemical method (e.g., ball milling) with appropriate precursors.

- Synthesis of Sn3O4 nanoflowers: Synthesize Sn3O4 separately via a hydrothermal method.

- Formation of Heterojunction: Combine the as-prepared CdS and Sn3O4 using a mixed heating method.

- Characterization: Confirm successful loading and heterojunction formation using SEM-EDS and XPS. Measure the increased photocurrent density via photoelectrochemical tests to verify enhanced charge separation.

Protocol 2: Enhancing TiOâ‚‚ Visible Activity via Natural Dye Sensitization

This eco-friendly protocol extends TiO2's response into the visible spectrum [19].

- Dye Extraction:

- Anthocyanin: Macerate dried red water lily petals in an acidified ethanol-water solution. Heat briefly, then store in the dark for 24 hours. Filter and concentrate the extract using a rotary evaporator.

- Chlorophyll: Macerate fresh water hyacinth leaves in aqueous acetone. Keep in the dark, then centrifuge and filter. Concentrate the supernatant.

- Sensitization of TiO2: Immerse TiO2 nanoparticles (e.g., P25) in the concentrated dye extract. Stir the mixture in the dark for 20 hours to allow dye adsorption.

- Washing and Drying: Centrifuge the mixture to retrieve the sensitized TiO2. Rinse with the original solvent to remove unbound dye and dry at 70°C.

- Activity Validation: Evaluate photocatalytic performance by monitoring the degradation of a model pollutant like methylene blue under visible light.

Protocol 3: Hydrothermal Synthesis of Mn-Doped CdS (Mnâ‚“Cdâ‚â‚‹â‚“S) for Stable Hâ‚‚ Production

This protocol uses doping to engineer a more stable and active solid-solution photocatalyst [18].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve precise molar ratios of manganese acetate (Mn(CH3COO)2·4H2O) and cadmium acetate (Cd(CH3COO)2·2H2O) in deionized water.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Add an aqueous solution of sodium sulfide (Na2S·9H2O) as the sulfur source to the metal ion solution. Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat (e.g., 160-180°C) for several hours.

- Product Recovery: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool naturally. Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation, wash thoroughly with water and ethanol, and dry.

- Performance Testing: Assess the hydrogen evolution rate under visible light using simulated wastewater or other reaction media.

Visualizing the Charge Transfer in a Stability-Enhancing Heterojunction

The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of a Type-II heterojunction, a common strategy used to separate charges and reduce photocorrosion.

Diagram: Charge Separation in a Type-II Heterojunction This mechanism shows how photogenerated electrons (eâ») migrate to the conduction band of one semiconductor, while holes (hâº) migrate to the valence band of the other. This spatial separation suppresses charge carrier recombination, leading to higher photocatalytic efficiency and reduced photocorrosion, as the catalyst is less likely to be degraded by its own reactive charges [17] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents for Stability Enhancement

| Reagent / Material | Function in Photocatalyst Design | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tin Acetate / Chloride | Precursor for synthesizing Sn3O4, used to form heterojunctions with CdS to enhance charge separation and stability [17]. | Building block for CdS-Sn3O4 heterojunction [17]. |

| Manganese Acetate | Dopant precursor for creating MnxCd1-xS solid solutions, which tune the bandgap and improve photostability [18]. | Used in Mn-doped CdS for H2 production from wastewater [18]. |

| Natural Dyes (Anthocyanin/Chlorophyll) | Visible light sensitizers for wide-bandgap semiconductors (e.g., TiO2), enabling visible-light-driven catalysis without toxic elements [19]. | Extracted from red water lily/water hyacinth for TiO2 sensitization [19]. |

| Silicone Adhesive | A stable binder for immobilizing photocatalyst powders onto solid supports, crucial for creating fixed-bed reactors and enabling catalyst reuse [22]. | Used to immobilize TiO2-clay composite in a rotary photoreactor [22]. |

| Strontium Titanate (SrTiO3) | A perovskite semiconductor used to form heterojunctions, improving charge separation and protecting unstable light-harvesting materials [23]. | Component in ZnO/Zn3As2/SrTiO3 heterojunction for water splitting [23]. |

| Cefivitril | Cefivitril, CAS:66474-36-0, MF:C15H15N7O4S3, MW:453.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Phthiobuzone | Phthiobuzone|CAS 79512-50-8|Research Chemical | Phthiobuzone is a chemical compound for research use only. It is not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. Explore its applications. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Moisture-Induced Degradation

Problem: Solar cells exhibit a yellowish discoloration and a rapid drop in power conversion efficiency (PCE) when exposed to ambient air.

- Root Cause: Water molecules catalyze the irreversible decomposition of the perovskite crystal structure. The process begins with the formation of a hydrated intermediate (e.g., MAPbI₃·H₂O), which can further decompose into PbI₂ and other by-products, leading to device failure [25].

- Solution:

- Prevention during fabrication: Control relative humidity during the film-processing stages to below 30% [26].

- Material Engineering: Incorporate 2D perovskites as a capping layer or within a tandem structure. The organic layers in 2D perovskites act as a hydrophobic barrier, preventing moisture penetration [27].

- Device Encapsulation: Implement robust, edge-sealed encapsulation to physically isolate the perovskite layer from environmental moisture [25].

Guide 2: Managing Performance Loss from Surface Defects

Problem: High open-circuit voltage (Voc) losses and significant hysteresis in current-voltage (J-V) measurements are observed.

- Root Cause: Surface and grain boundary defects, such as undercoordinated Pb²⺠ions and halide vacancies, act as non-radiative recombination centers. These defects trap charge carriers, reducing their lifetime and diffusion length [28] [29].

- Solution:

- Surface Passivation: Apply a passivation layer to the finished perovskite film.

- Lewis Base Passivation: Use molecules like aniline compounds (e.g., phenylpropylammonium iodide) or small polymers with electron-donating groups. These molecules bind to undercoordinated Pb²⺠ions, neutralizing trap states [30] [29].

- Halide-based Passivation: Use alkyl ammonium halides (e.g., from chloroform/isopropanol solutions) to fill halide vacancies [30].

- Grain Boundary Engineering: Introduce additives like PbIâ‚‚ or fullerenes (e.g., PCBM) into the precursor solution or as a post-treatment. These materials can infiltrate grain boundaries, passivating defects and improving charge transport [28].

- Surface Passivation: Apply a passivation layer to the finished perovskite film.

Guide 3: Mitigating Reverse Bias Failure ("Shading Breakdown")

Problem: A small shaded area on a module causes localized heating, permanent damage, and a dark spot observed via electroluminescence (EL) or thermography imaging.

- Root Cause: Microscopic defects like pinholes or thin spots in the perovskite layer become "weak spots." Under reverse bias (when a cell is shaded but others are generating power), current is forced backward through these defects, causing intense localized heating, material melting, and short-circuiting between contact layers [31].

- Solution:

- Defect-Free Fabrication: Optimize the solution processing (e.g., solvent engineering, annealing) to create pinhole-free, uniform films. Using smaller device areas during R&D can help achieve defect-free samples for study [31].

- Robust Contact Layers: Employ more stable, thermally resilient charge transport layers that can withstand localized heating without degrading [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical intrinsic factors limiting perovskite solar cell stability? The primary intrinsic factors are ion migration and crystal defects. Ions (e.g., halides) can migrate through the soft crystal lattice under electric fields or light, leading to phase segregation and interface degradation. Defects at surfaces and grain boundaries accelerate non-radiative recombination and provide pathways for degradation [26] [25].

FAQ 2: How does heat contribute to perovskite degradation? Temperature fluctuations can induce phase changes in the perovskite structure. High temperatures can directly cause the decomposition of the perovskite material into PbIâ‚‚ and organic salts, a process that is often irreversible [26].

FAQ 3: What passivation strategies are most effective for tin-based perovskites? Tin-based perovskites suffer from more severe surface defects and rapid oxidation. Passivation is crucial and can be achieved using multifunctional molecules that simultaneously passivate multiple defect types. Strategies that form a low-dimensional (2D) perovskite capping layer on the 3D absorber are particularly promising, as they enhance stability against oxidation and moisture [27] [29].

FAQ 4: Are there stable perovskite formulations for use in aqueous environments (e.g., photocatalysis)? While challenging due to their inherent ionic solubility, progress is being made. Strategies include encapsulation in protective matrices, developing heterojunctions with stable materials, and using highly stable compositions like chalcogenide perovskites (e.g., CaZrS₃) for specific applications [32] [33].

Table 1: Common Degradation Factors and Their Impact on PSCs

| Degradation Factor | Primary Impact on Device | Resulting Efficiency Loss (Typical) | Key Passivation/Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture [25] | Decomposition to PbIâ‚‚ (yellowing) | Up to total failure | 2D perovskite capping layers, Encapsulation |

| Surface Defects [28] [30] | Non-radiative recombination; Reduced Voc & FF | 10-15% absolute PCE loss | Lewis base molecules (e.g., Aniline compounds) |

| Heat [26] | Phase instability; Irreversible decomposition | Varies with temperature & duration | Strain engineering; Negative thermal expansion materials |

| Reverse Bias (Shading) [31] | Localized heating & melting at defects | Catastrophic failure of shaded cell | Pinhole-free films; Robust contact layers |

Table 2: Comparison of Passivation Material Types

| Passivation Type | Example Materials | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Bases [28] [29] | Aniline compounds, IPFB | Donate electrons to undercoordinated Pb²⺠| High effectiveness for Voc improvement | May not address all defect types |

| Halide Salts [30] | Alkyl ammonium bromides | Fill halide (Iâ») vacancies | Reduces ion migration & hysteresis | Requires precise control of concentration |

| 2D Perovskites [27] [29] | Phenylalkylammonium iodides | Form protective, hydrophobic layer | Excellent environmental stability | Can hinder charge transport if misaligned |

| Polymers & Fullerenes [28] [30] | PCBM, PPy | Physical barrier & chemical passivation | Good coverage and device stability | Processing complexity can increase |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Passivation with Lewis Base Molecules

Objective: To reduce surface defect density and improve Voc and device stability.

- Perovskite Film Preparation: Fabricate your perovskite film (e.g., MAPbI₃ or FAPbI₃) using your standard method (e.g., spin-coating) in a controlled atmosphere.

- Passivation Solution Preparation: Dissolve the Lewis base passivant (e.g., 5-10 mg of aniline compound like phenylbutylammonium iodide) in 1 mL of a mild solvent such as isopropanol (IPA). Stir until fully dissolved.

- Application:

- After annealing and cooling the perovskite film, spin-coat the passivation solution onto the film at 3000-4000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Gently anneal the film at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to remove residual solvent and promote interaction with the perovskite surface.

- Characterization:

Protocol 2: Creating a 2D/3D Perovskite Heterostructure

Objective: To enhance device stability against moisture and thermal stress.

- 3D Perovskite Foundation: Prepare your standard 3D perovskite film (e.g., FAMAPbI₃).

- 2D Precursor Solution: Dissolve a large organic ammonium salt (e.g., phenylethylammonium iodide or butylammonium iodide) in IPA at a concentration of 1-2 mg/mL.

- Heterostructure Formation:

- Spin-coat the 2D precursor solution directly onto the 3D perovskite film.

- Use a two-step spin-coating program: 1000 rpm for 10 s (spread) and 4000 rpm for 30 s (thin).

- Anneal at 100°C for 10 minutes. This process induces the formation of a thin, layered 2D perovskite capping layer on the 3D bulk.

- Characterization:

- Perform X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm the presence of characteristic peaks for the 2D perovskite phase [27] [29].

- Conduct water contact angle measurements to show increased hydrophobicity.

- Subject devices to damp heat testing (e.g., 85°C/85% RH) and track PCE over time to quantify stability improvement [27].

Visualizations: Mechanisms and Workflows

Perovskite Degradation Pathways

Surface Passivation Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Phenylbutylammonium Iodide [30] | Forms a stable 2D/3D heterojunction for surface passivation and stability enhancement. | The alkyl chain length affects charge transport; optimization is required. |

| PCBM (Phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester) [28] | Fullerene-based passivator that infiltrates grain boundaries and reduces trap-assisted recombination. | Can be applied as a thin layer between the perovskite and electron transport layer. |

| Lead Iodide (PbIâ‚‚) [28] | Additive or interlayer that passivates grain boundaries and improves crystal quality. | Excess PbIâ‚‚ can be detrimental; precise stoichiometric control is critical. |

| Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) [27] | Solvent additive that assists in the formation of high-quality, well-aligned 2D perovskite films during bar-coating. | Influences crystallization kinetics and final film morphology. |

| Phytic Acid (PA) [34] | A dopant for conducting polymers (e.g., PANI) used in composite photocatalysts; acts as a proton shuttle and crosslinker. | Enhances interfacial contact and stability in organic-inorganic heterojunctions. |

| N3-benzoylthymine | N3-benzoylthymine, CAS:4330-20-5, MF:C12H10N2O3, MW:230.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,4-Dibromofuran | 2,4-Dibromofuran, CAS:32460-06-3, MF:C4H2Br2O, MW:225.87 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Material Design and Engineering Strategies for Robust Photocatalysts

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Photocatalytic Stability Experiments

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Decay | Gradual decrease in dye degradation efficiency over reaction cycles. | Catalyst surface fouling or poisoning by reaction intermediates. | Implement a calcination protocol (300-400°C for 2 hours) to burn off residues [35]. | Introduce intermediate washing steps with deionized water and ethanol between cycles. |

| Rapid deactivation within the first few cycles. | Leaching of active components due to weak bonding or structural collapse. | Verify the synthesis pH; use post-synthesis ion exchange to enhance active site stability [35]. | Pre-test the chemical stability of the catalyst support in the reaction medium. | |

| Material Synthesis | Inconsistent photocatalytic activity between batches. | Variations in precursor mixing or aging time during geopolymer support formation. | Standardize the mixing energy (RPM) and duration, and control ambient curing temperature [35]. | Create a detailed, step-by-step standard operating procedure (SOP) for synthesis. |

| Cracks or defects forming in geopolymer-supported catalysts. | Rapid drying or excessive heat during curing. | Control the curing environment (e.g., use a humidity chamber >80% RH) [35]. | Adjust the H2O/M2O molar ratio in the initial geopolymer mixture. | |

| Characterization | Inability to distinguish adsorption from photocatalytic degradation. | Inadequate control experiment leading to overestimation of activity. | Always run a dark adsorption experiment until equilibrium is reached before light exposure [35]. | Use multiple analysis methods (e.g., TOC analysis) to confirm pollutant mineralization. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Material Design and Selection

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind using cation and anion tuning to improve the stability of photocatalysts?

The principle lies in controlling the electronic structure and chemical resilience of the photocatalytic material. The intrinsic stability is governed by the material's bandgap, which is the energy difference between its valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) [3]. By substituting cations (e.g., doping transition metals into metal oxides) or anions (e.g., nitrogen doping), the bandgap can be engineered to be more resistant to photocorrosion. This tuning can also strengthen the chemical bonds and reduce the likelihood of leaching of active components into the solution, thereby enhancing the material's longevity [35].

Q2: Why are geopolymers suggested as a support material for photocatalytic nanocomposites?

Geopolymers, which are ecologically-friendly inorganic polymers, serve as excellent supports for several reasons. They are typically produced at low temperatures from industrial wastes, making them cost-effective and sustainable [35]. Their random three-dimensional aluminosilicate structure contains exchangeable charge-balancing ions (e.g., Na+, K+) in the interstices, which allows for the effective introduction and stabilization of photocatalytic moieties like TiO2, ZnO, or CuO [35]. Furthermore, they can act as adsorbents, concentrating pollutant molecules near the active photocatalytic sites, and some geopolymers made from Fe2O3-containing wastes even show intrinsic photoactivity [35].

Experimental Protocol

Q3: What is the critical control experiment required to accurately measure photocatalytic degradation and not just adsorption?

A critical and mandatory step is the dark adsorption control experiment. The catalyst and the pollutant solution (e.g., a dye) must be mixed and kept in complete darkness with continuous stirring until adsorption-desorption equilibrium is established. This process can take 30-60 minutes. Only after this equilibrium is reached should the light source be turned on. The removal measured after illumination is then attributed to photocatalytic degradation, not physical adsorption [35]. Failure to do this correctly is a common source of error and overestimation of performance.

Q4: What is a robust methodology for synthesizing a geopolymer-supported photocatalyst?

Below is a generalized, detailed protocol for creating a metal oxide-loaded geopolymer photocatalyst:

- Geopolymer Precursor Preparation: Mix a solid aluminosilicate source (e.g., metakaolin or fly ash) with an alkaline activator solution. A typical molar ratio is SiO2/Al2O3 ≈ 3, M2O/SiO2 ≈ 0.3, and H2O/M2O ≈ 10, where M is Na or K [35].

- Catalyst Incorporation: Disperse the photocatalyst precursor (e.g., nano-TiO2 powder or a soluble salt like Cu(NO3)2) uniformly into the geopolymer precursor slurry. This can be achieved by mechanical stirring or sonication for 30 minutes.

- Casting and Curing: Pour the mixture into molds and seal them to prevent moisture loss. Cure the samples at ambient temperature or a slightly elevated temperature (e.g., 60-80°C) for 24-48 hours [35].

- Post-Synthesis Modification (Optional): Perform an ion-exchange process by immersing the hardened geopolymer in a solution containing the desired cations to enhance the distribution and stability of active sites [35].

- Activation and Drying: Gently wash the synthesized monolith and dry it at a low temperature (e.g., 80°C) before use.

Data Analysis and Validation

Q5: Beyond dye bleaching, what other analytical methods are crucial for validating photocatalytic stability?

While dye bleaching is common, it is not sufficient for a comprehensive stability assessment, especially for a thesis. Key additional methods include:

- Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Analysis: To detect and quantify metal ions leaching from the photocatalyst into the solution, providing direct evidence of material stability or degradation [35].

- Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Analysis: To confirm the mineralization of the pollutant into CO2 and H2O, rather than just a color change, which verifies true catalytic effectiveness [35].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): To analyze the surface chemical states of the cations and anions before and after reaction cycles, confirming the material's chemical stability or identifying oxidation state changes.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standardized Photocatalytic Testing Protocol

This protocol describes a method for evaluating the stability and reusability of a photocatalyst.

Objective: To quantify the degradation efficiency of a model pollutant (e.g., Methylene Blue dye) over multiple cycles and assess catalyst stability.

Materials:

- Photocatalyst sample (e.g., ZnO/geopolymer composite)

- Model pollutant solution (e.g., 10 mg/L Methylene Blue)

- Photoreactor setup with a defined light source (e.g., UV lamp, 365 nm)

- Magnetic stirrer

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer or TOC Analyzer

Procedure:

- Dark Adsorption: Add 100 mg of catalyst to 100 mL of pollutant solution in the reactor. Stir in the dark for 60 minutes. Periodically take 3-4 mL samples, centrifuge, and analyze the supernatant to determine the concentration at equilibrium (C_dark).

- Photocatalytic Reaction: Turn on the light source. Take samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes). Centrifuge and analyze the concentration (C_t).

- Reusability Test: After one cycle (e.g., 120 min light), recover the catalyst by centrifugation. Wash gently with deionized water and ethanol, then dry at 80°C. Repeat steps 1-2 with a fresh pollutant solution for the next cycle. Perform at least 3-5 cycles.

- Leaching Test: Use ICP analysis on the reaction solution after each cycle to measure the concentration of leached metal ions.

Data Analysis: Calculate the degradation efficiency for each cycle using the formula: Efficiency (%) = [(Cdark - Ct) / C_dark] × 100

Quantitative Data on Photocatalyst Performance

Table 2: Representative Performance Data of Various Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst Material | Target Pollutant | Initial Degradation Rate (mg/g·h) | Degradation Efficiency After 5 Cycles | Key Stability Feature (Cation/Anion Tuning) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2-loaded Geopolymer [35] | Methylene Blue | ~25.0 | >90% | Stable Ti4+ cations in the aluminosilicate matrix. |

| CuO-doped Geopolymer [35] | Rhodamine B | ~18.5 | ~85% | Doped Cu2+ cations enhancing visible light absorption. |

| Fe2O3-containing Geopolymer [35] | Organic dyes | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Intrinsic activity from Fe3+ cations in the waste-derived precursor. |

| ZnO/Graphene Composite (for comparison) | Various VOCs | ~30.0 (estimated) | ~75% | Zn2+ stability can be compromised by photocorrosion. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example in Application |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminosilicate Source | Base material for creating the geopolymer support structure. | Metakaolin, Fly Ash, Ground Blast Furnace Slag [35]. |

| Alkali Activator | Chemical solution that dissolves the solid precursor and initiates geopolymerization. | A mixture of Sodium Silicate (Na2SiO3) and Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) [35]. |

| Photocatalytic Moieties | The active components responsible for absorbing light and catalyzing reactions. | Metal oxides like TiO2, ZnO, CuO, Fe2O3, or their precursor salts [35]. |

| Model Pollutants | Chemical compounds used to standardize and test photocatalytic activity. | Organic dyes (Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B) in water [35]. |

| Specialized Databases | Platforms for identifying materials, properties, and related scientific literature. | ASM Handbooks, SpringerMaterials, Scopus, SciFinder [36] [37]. |

| Succinonitrile-d4 | Succinonitrile-d4, CAS:23923-29-7, MF:C4H4N2, MW:84.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chromous formate | Chromous Formate|CAS 4493-37-2|RUO |

Visualization Diagrams

Photocatalytic Stability Workflow

Photocatalysis Mechanism

Cation/Anion Tuning Logic

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides solutions for researchers facing challenges in controlling the morphology and crystallinity of inorganic compounds, particularly to enhance their structural integrity for applications in photocatalysis. The guides below address common experimental issues, with protocols framed within research on photocatalytic stability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my synthesized photocatalyst exhibit low structural integrity and rapid performance degradation? Low structural integrity often stems from poor crystallinity or inappropriate morphology. High crystallinity provides a regular atomic arrangement that facilitates efficient charge carrier transport and reduces recombination sites, which is crucial for photocatalytic stability [38]. Similarly, the morphology (e.g., nanosheets, hollow spheres) dictates surface area, active site availability, and ion diffusion pathways, all of which influence structural resilience during catalytic cycles [39]. For instance, hollow nanoparticles can better accommodate volume changes during reactions, preventing mechanical degradation [39].

FAQ 2: How can I control the crystallinity of my photocatalytic material during synthesis? Crystallinity is highly dependent on the synthesis method and conditions. Methods like solvothermal and hydrothermal synthesis often yield higher crystallinity compared to simpler methods like co-precipitation [39]. A novel "zone crystallization" strategy for covalent organic frameworks demonstrates how regulator-induced amorphous-to-crystalline transformation can enhance surface ordering and, consequently, photocatalytic activity and stability [38]. Key parameters to control include:

- Temperature: Higher temperatures typically promote atomic mobility and crystallite growth.

- Reaction Time: Longer aging or reaction times allow for more complete structural rearrangement into ordered, crystalline phases.

- Chemical Reversibility: Using modulators or regulators can enhance the dynamic reversibility of bond formation, which helps correct structural defects and improve overall crystallinity [38].

FAQ 3: What are the best characterization techniques to correlate morphology/crystallinity with photocatalytic stability? A multi-technique approach is essential. The table below summarizes key techniques and their purposes.

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques for Morphology and Crystallinity

| Technique | Primary Function | Information on Structural Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Determines crystal phase, crystallinity, and lattice parameters. | Identifies crystalline phases; high, sharp peaks indicate good crystallinity. Peak broadening can suggest small crystallite size or microstrain [39]. |

| Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Analyzes morphology, size, and surface structure. | Directly visualizes morphology (e.g., nanosheets, rods), particle size, and potential structural defects like cracks or agglomeration [39] [40]. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Probes surface chemical composition and electronic state. | Identifies surface dopants, defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies), and chemical states that influence surface stability and reactivity [41]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Measures thermal stability and composition. | Assesses material stability against thermal decomposition and can quantify bound water or organic components within structures [39]. |

FAQ 4: My material has high surface area but poor photocatalytic efficiency. What is the underlying issue? This is a common problem where enhanced light absorption is counterbalanced by high charge carrier recombination. While high surface area is beneficial, the material's electronic structure and crystallinity are equally critical. Efficient photocatalysis requires not only generating electron-hole pairs but also separating them and transporting them to the surface. Poor crystallinity introduces defect sites that act as recombination centers, annihilating the photogenerated charges before they can participate in surface reactions [13] [38]. Therefore, a balance must be struck between creating high surface area and maintaining high crystallinity for effective charge transport.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem 1: Inconsistent Morphology Between Batches of Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs)

- Issue: LDHs synthesized via the same co-precipitation protocol result in different morphologies (e.g., sometimes platelets, sometimes irregular aggregates).

- Solution: Strictly control the following parameters, as they heavily influence nucleation and growth kinetics [39]:

- pH: Maintain a constant and precise pH throughout the precipitation process. The pH value can determine which crystalline facets grow faster.

- Temperature: Use a precision water bath to ensure a consistent and stable reaction temperature.

- Addition Rate: Control the dropping rate of precursor solutions using a syringe pump. Rapid addition can lead to homogenous nucleation and many small particles, while slow addition favors the growth of larger, more defined crystals.

- Aging Time: Standardize the aging time and temperature after initial precipitation, as this period allows for Ostwald ripening and structural ordering.

Problem 2: Poor Crystallinity in Metal Oxide Photocatalysts Synthesized via Green Solvents

- Issue: Metal oxides (e.g., TiOâ‚‚, ZnO) synthesized using deep eutectic solvents (DES) exhibit weak and broad XRD peaks, indicating low crystallinity.

- Solution:

- Post-synthesis Treatment: Implement a calcination step. After the DES-assisted synthesis, calcine the material at an optimized temperature (e.g., 400-500°C for TiO₂) in a muffle furnace. This post-treatment removes residual organics and promotes crystal growth [42].

- Optimize DES Properties: The high viscosity of DES can limit ion mobility. Adjust the water content in the DES mixture to reduce viscosity, thereby enhancing ion diffusion and facilitating better crystal growth [42].

- Switch Methods: Consider using a hydrothermal/solvothermal method with the DES. The high temperature and pressure in an autoclave can significantly improve crystallinity [42] [43].

Problem 3: Rapid Deactivation of a Highly Active Photocatalyst During Cycling Tests

- Issue: A photocatalyst shows excellent initial performance for hydrogen evolution or pollutant degradation but loses over 50% of its activity within a few cycles.

- Solution:

- Check Structural Integrity: Perform XRD and SEM on the used catalyst. The deactivation could be due to morphological changes (e.g., sintering, aggregation) or loss of crystallinity. Using morphologies like core-shell or hollow structures can buffer volume changes and enhance stability [39].

- Surface Poisoning: Identify if reaction intermediates are strongly adsorbed on active sites, blocking them. Perform a regeneration step, such as washing with a suitable solvent or calcining in air at a low temperature to burn off carbonaceous deposits [13].

- Leaching of Components: For composite or doped photocatalysts, use ICP-MS analysis on the reaction solution after cycling to check for leached metal ions. To mitigate this, focus on creating strong chemical bonds between components, such as in heterojunctions, rather than physical mixtures [40].

Experimental Workflow for Systematic Optimization

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and solving issues related to morphology, crystallinity, and structural integrity in photocatalytic materials.

Research Reagent Solutions for Morphology-Controlled Synthesis

This table details key reagents and their functions for fabricating photocatalysts with controlled morphology and crystallinity, drawing from advanced synthesis protocols.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Morphology and Crystallinity Control

| Reagent / Material | Function in Synthesis | Key Consideration for Structural Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [42] | A versatile, eco-friendly reaction medium that can act as a solvent, template, and reactant. Its high viscosity and hydrogen bonding control diffusion and crystal growth kinetics. | The choice of Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) and Acceptor (HBA) allows tuning of solvent properties (polarity, viscosity) to direct morphology (e.g., nanospheres, rods) and influence crystallinity. |

| Structure-Directing Agents (SDAs) / Surfactants [39] | Molecules that adsorb to specific crystal facets, altering surface energies and directing growth to form specific morphologies like nanoplates, flowers, or rods. | Overuse can lead to pore blockage or require harsh removal methods (high-temperature calcination) that may compromise the material's structure. Concentration and type are critical. |

| Crystallization Regulators [38] | Monofunctional molecules (e.g., modulators) that influence the reversibility of bond formation during synthesis, allowing error correction and enhancing long-range order. | Essential for improving the crystallinity of covalent organic frameworks (COFs) and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). They promote the formation of surface crystalline domains, which enhance charge separation. |

| Metal Oxide Precursors [43] [40] | Provide the metal and oxygen source for forming the photocatalyst's framework (e.g., Ti alko xides for TiOâ‚‚, Zn salts for ZnO). | The precursor's reactivity and concentration are key for controlling nucleation and growth rates. High purity precursors minimize unintended doping that can create charge recombination centers. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Morphology-Controlled LDHs via Hydrothermal Method [39]

- Objective: To synthesize highly crystalline NiFe-LDH nanosheets for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction (OER) activity and stability.

- Materials: Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Iron nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O), Urea (CO(NH₂)₂), Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve 5 mmol of Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, 2.5 mmol of Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, and 30 mmol of urea in 70 mL of deionized water under vigorous stirring for 1 hour.

- Transfer the homogeneous solution into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave.

- Seal the autoclave and heat it in an oven at 120°C for 24 hours.

- After natural cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation.

- Wash the product repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol to remove impurities.

- Dry the final product in a vacuum oven at 60°C for 12 hours.

- Expected Outcome: This protocol yields well-defined NiFe-LDH nanosheets with high crystallinity and a large surface area, which maximizes the exposure of active sites and facilitates reactant diffusion.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Crystallinity in COFs via a Zone Crystallization Strategy [38]

- Objective: To synthesize β-ketoenamine-linked COF microspheres with enhanced surface crystallinity for superior photocatalytic hydrogen evolution.

- Materials: 1,3,5-Triformylphloroglucinol (Tp), p-phenylenediamine (Pa-1), 4-aminobenzaldehyde (Regulator), Mesitylene, Dioxane, Acetic acid (6 M aqueous solution).

- Procedure:

- (Amorphous Precursor): Reflux a mixture of Tp (0.3 mmol) and the regulator (0.6 mmol) in a solvent mixture of mesitylene/dioxane (3/3 mL) with 0.5 mL of acetic acid for 2 hours. Collect the spherical amorphous precursor by centrifugation.

- (Crystalline Transformation): Redisperse the precursor and Pa-1 (0.45 mmol) in a fresh mixture of mesitylene/dioxane (3/3 mL) with 0.5 mL of acetic acid in a Pyrex tube.

- Sonicate the mixture for 10 minutes, then freeze-thaw-degas for three cycles.

- Seal the tube and heat it at 120°C for 3 days.

- Collect the final product by filtration and wash with anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF). Activate the product by supercritical COâ‚‚ drying.

- Expected Outcome: This two-step method produces COF microspheres with high surface crystallinity, which builds strong internal electric fields to accumulate photogenerated electrons and drastically improve photocatalytic hydrogen production rates and stability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a heterojunction, and why is it a key strategy for improving photocatalytic stability? A heterojunction is an interface formed between two different semiconductor materials (or a metal and a semiconductor) [44]. At this interface, a discontinuity in the conduction and valence bands creates an internal electric field [44]. This field is the fundamental mechanism for enhancing spatial charge separation, which directly inhibits the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [44] [45]. By minimizing charge recombination, heterojunctions reduce the accumulation of reactive species that can degrade the photocatalyst itself, thereby addressing a primary cause of instability [13].

Q2: My heterojunction is not showing the expected activity improvement. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. The issue often lies in the band alignment between the two materials. A successful heterojunction requires that the band structures of the two components are compatible to facilitate the desired charge transfer. If the activity is low, the band alignment might be forming a less-efficient Type-I heterojunction, where both charges accumulate on one material, limiting redox power [44]. Consider re-engineering the interface to form a Step-scheme (S-scheme) or Z-scheme heterojunction, which improves charge separation while maintaining strong redox ability [44]. Furthermore, ensure there is intimate contact at the interface, as poor contact hinders charge transfer across the materials.

Q3: How can I characterize the successful formation of a heterojunction? A multi-technique approach is necessary:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Use this to confirm the coexistence of the crystalline phases of both materials without the formation of unwanted intermediate phases [45].

- Electron Microscopy (TEM/HRTEM): This is crucial for visually confirming the physical interface and close contact between the two components [44].

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A significant quenching of the PL signal in the heterojunction compared to the individual materials indicates suppressed electron-hole recombination, providing strong evidence for successful charge separation [44].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): This can detect shifts in binding energy, revealing changes in the chemical environment and electronic interaction at the interface.

Q4: Are there alternatives to noble metal co-catalysts for heterojunctions? Yes, the field is actively moving away from scarce and expensive noble metals. Research shows that transition metal sulfides (e.g., MoSâ‚‚, NiSâ‚“) and phosphides can be highly effective co-catalysts [44]. For instance, a g-C₃Nâ‚„/1T′ MoSâ‚‚ heterojunction has demonstrated a hydrogen evolution activity of 4426 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹, outperforming its 2H-MoSâ‚‚ counterpart [44]. These materials act as efficient electron acceptors, synergistically enhancing charge separation and providing active sites for the catalytic reaction.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Deactivation of Heterojunction Photocatalyst

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Photocorrosion. The photocatalyst undergoes oxidation or reduction itself instead of facilitating the target reaction.

- Solution: Incorporate a protective co-catalyst, such as a transition metal sulfide, to swiftly extract charges from the light-absorbing material, thereby protecting it [44]. Also, consider using more stable semiconductor components.

- Cause 2: Poor Interfacial Contact. Weak physical or electronic contact between the two components leads to high interfacial charge transfer resistance.

- Cause 3: Incorrect Band Alignment. The heterojunction type does not provide sufficient driving force for the target reaction.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the band structures of your materials. Design an S-scheme heterojunction, which not only achieves superior charge separation but also preserves electrons and holes with the highest redox potential for more demanding reactions [44].

Problem: Low Quantum Efficiency Despite Good Charge Separation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Sacrificial Agent Dependency. The system might be optimized for use with a sacrificial electron donor or acceptor, which masks inherent inefficiencies in the catalytic sites for the full reaction cycle (e.g., simultaneous Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ evolution in water splitting) [46].