Stacked Generalization for Materials Property Prediction: A Comprehensive Framework for Accelerated Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of stacked generalization, an advanced ensemble learning technique, for predicting materials properties.

Stacked Generalization for Materials Property Prediction: A Comprehensive Framework for Accelerated Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of stacked generalization, an advanced ensemble learning technique, for predicting materials properties. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the foundational theory of stacking, its methodological implementation using diverse base learners and meta-models, and strategies for troubleshooting common challenges like computational cost and data scarcity. Through validation against individual models and other advanced frameworks, the article demonstrates the superior accuracy and robustness of stacking for applications ranging from high-entropy alloy design to molecular property prediction in drug discovery. The synthesis offers practical insights for integrating this powerful AI tool into materials development pipelines to enhance efficiency and predictive performance.

The Foundation of Stacked Generalization: From Basic Theory to Materials Science Applications

In the rapidly evolving field of materials science, accurately predicting properties such as the yield strength of high-entropy alloys (HEAs) or the compressive strength of sustainable concrete is paramount for accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation materials [1] [2]. Traditional experimental approaches and single-model computational methods often struggle with the vast compositional space and complex, non-linear interactions inherent in these material systems. Ensemble learning has emerged as a powerful machine learning paradigm that addresses these challenges by combining multiple models to achieve superior predictive performance and robustness compared to any single constituent model [3] [4]. This article provides a detailed introduction to the three cornerstone ensemble techniques—Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking—framed within the context of advanced materials property prediction. We will delineate their core mechanisms, illustrate their applications with quantitative comparisons, and provide detailed experimental protocols for their implementation in research settings, with a special emphasis on stacked generalization.

Core Ensemble Methods: Mechanisms and Comparisons

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating)

Bagging is designed primarily to reduce variance and prevent overfitting, especially in high-variance models like deep decision trees [4].

- Mechanism: It creates multiple bootstrap samples (random subsets with replacement) from the original training dataset. A base model, often referred to as a base learner, is trained independently on each of these samples. During prediction, for regression tasks, the outputs of all models are averaged; for classification, a majority vote is taken [4].

- Key Advantage: The independence of base model training allows for parallel processing, significantly reducing computation time [4].

- Representative Algorithm: Random Forest is an extension of bagging that further de-correlates trees by randomly selecting a subset of features at each split, enhancing model robustness [4].

Boosting

Boosting is a sequential ensemble method that focuses on reducing bias by iteratively learning from the errors of previous models [4].

- Mechanism: It trains a sequence of weak learners, where each subsequent model pays more attention to the training instances that were misclassified by its predecessors. This is typically achieved by adjusting the weights of data points. The final prediction is a weighted sum of the predictions from all weak learners [4].

- Key Advantage: Boosting often leads to high predictive accuracy and is particularly effective on structured or tabular data [4].

- Representative Algorithms: AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting) and Gradient Boosting, including its advanced implementations like XGBoost and LightGBM [5] [4].

Stacking (Stacked Generalization)

Stacking is a more advanced ensemble technique that introduces a hierarchical structure to combine multiple, potentially diverse, base models using a meta-learner [1] [4].

- Mechanism: The process involves two levels. At Level-0, diverse base models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machines) are trained on the original data. Their predictions on a validation set (often generated via cross-validation) form a new dataset, known as the meta-features. At Level-1, a meta-model (or meta-learner) is trained on these meta-features to learn the optimal way to combine the predictions of the base models [1] [4].

- Key Advantage: Stacking leverages the strengths of different algorithmic approaches, often capturing complex patterns that a single model type might miss, thereby frequently achieving state-of-the-art predictive performance [1] [6].

- Application Context: It has been successfully applied in diverse prediction tasks, from the yield strength of high-entropy alloys [1] to automated real estate valuation [7] [6].

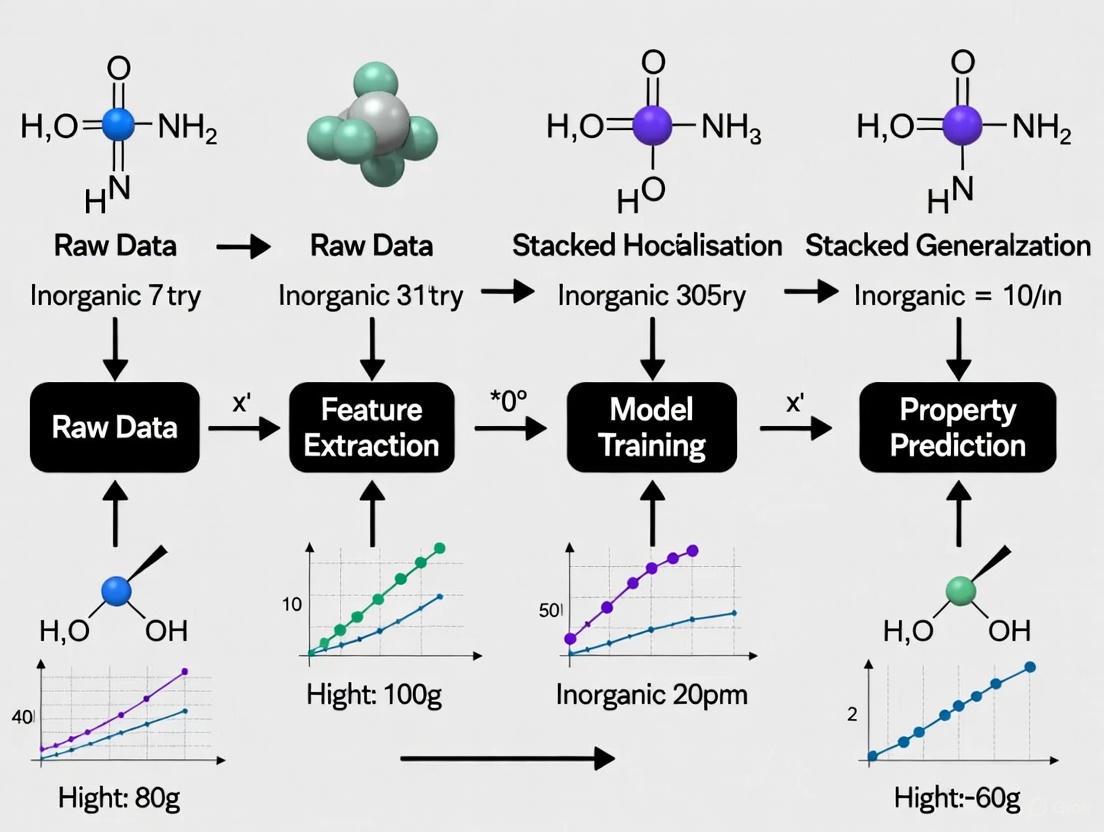

The following workflow diagram illustrates the structured process of a stacking ensemble, from data preparation to final prediction.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of the three ensemble methods, synthesizing performance metrics reported across various applied studies in materials science and property valuation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ensemble Learning Methods

| Ensemble Method | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging (e.g., Random Forest) | High feature importance interpretability; Effective variance reduction [4]. | Parallelizable training, robust to noise and overfitting [4]. | Phase classification in HEAs [1], concrete strength prediction [2]. |

| Boosting (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) | Often the top-performing base model; LightGBM: AUC=0.953, F1=0.950 [5]; XGBoost: R²=0.983 for concrete strength [2]. | High predictive accuracy, effective bias reduction [4]. | Predicting student academic performance [5], strength of concrete with industrial waste [2]. |

| Stacking | Marginal but significant improvement over best base model; MdAPE reduction from 5.24% (XGB) to 5.17% [7]. | Leverages model diversity, often achieves state-of-the-art results [1] [6]. | HEA mechanical property prediction [1], automated valuation models (AVMs) [7] [6]. |

Experimental Protocol for Stacked Generalization

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for developing a stacking ensemble model, tailored for predicting materials properties such as the yield strength of High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs) [1].

Dataset Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Data Collection: Compile a dataset from publicly available materials databases and literature. For HEA prediction, the dataset should include composition, processing conditions, and measured mechanical properties [1].

- Feature Pooling: Extract key physicochemical features and derived parameters. These may include atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electron concentration, and mixing enthalpy [1].

- Feature Selection: Implement a feature selection strategy to identify the most relevant descriptors. The Hierarchical Clustering-Model-Driven Hybrid Feature Selection (HC-MDHFS) strategy can be employed:

- Use hierarchical clustering to group highly correlated features, reducing redundancy.

- Dynamically select the best feature subset based on the performance of base learners [1].

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training (e.g., 75%) and testing (e.g., 25%) sets. Ensure the splits are representative and, if necessary, stratified [7].

Model Training and Validation: Level-0

- Base Learner Selection: Choose diverse, high-performing algorithms as base models. Recommended models include:

- Cross-Validation for Meta-Features:

- Perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) on the training set for each base model.

- For each model and each fold, retain the out-of-fold predictions on the validation folds. Concatenating these predictions forms a new feature set, the meta-features, which serve as the training data for the meta-learner [4].

- Optionally, make predictions on the hold-out test set using the full base models trained on the entire training set. These will be the test-set meta-features.

Model Training and Validation: Level-1

- Meta-Learner Selection: Train a meta-model on the meta-features dataset. Simpler, linear models are often effective to prevent overfitting.

- Final Model Training: The final stacking model is an integrated pipeline of the base learners and the meta-learner.

Model Interpretation and Validation

- Performance Evaluation: Validate the final stacked model on the held-out test set using metrics relevant to the field: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Coefficient of Determination (R²), and Median Absolute Percentage Error (MdAPE) [1] [7] [2].

- Interpretability Analysis: Apply model interpretation techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to assess the global and local importance of features in the model's predictions, providing insights into the underlying physical factors governing material properties [1] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" required for implementing ensemble models in materials informatics research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ensemble Learning

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn | A core Python library providing implementations of Bagging, Boosting (AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting), and Stacking classifiers/regressors, along with data preprocessing and model selection tools [4]. | sklearn.ensemble.StackingClassifier |

| XGBoost / LightGBM | Optimized gradient boosting libraries designed for speed and performance, frequently serving as high-performance base learners in ensembles [5] [2]. | xgb.XGBRegressor() |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A unified framework for interpreting model predictions, crucial for explaining complex ensemble models and deriving scientific insights from materials informatics models [1] [5]. | shap.TreeExplainer() |

| Molecular Embedders | Algorithms that transform molecular or crystal structures into numerical vectors (descriptors), enabling the application of ML to chemical and materials data [8]. | VICGAE, Mol2Vec [8] |

| HC-MDHFS Strategy | A hybrid feature selection method that uses hierarchical clustering to reduce multicollinearity before a model-driven selection of the most predictive features for the target property [1]. | Custom implementation based on domain knowledge and model feedback. |

| Synthetic Minority Oversampling (SMOTE) | A data balancing technique used to address class imbalance in datasets, which can be critical for predictive tasks involving rare phases or failure modes [5]. | imblearn.over_sampling.SMOTE |

Stacked generalization, or stacking, is an advanced ensemble machine learning technique designed to enhance predictive performance by combining multiple models. Its core principle involves a two-layer architecture: a set of base learners (level-0 models) that make initial predictions from the original data, and a meta-learner (level-1 model) that learns to optimally combine these predictions to produce a final output [9]. This approach is particularly valuable in materials science and drug development, where it can uncover complex relationships between processing parameters, chemical compositions, and functional properties, thereby accelerating the discovery of new materials and compounds [10] [11].

Core Architectural Principles

The architecture of stacked generalization is fundamentally designed to leverage the strengths of diverse modeling approaches.

The Base Learner Layer

Base learners are a set of heterogeneous models trained independently on the same dataset. Their purpose is to capture different patterns or perspectives within the data. Diversity among base models is critical; using models with different inductive biases (e.g., tree-based methods, linear models, neural networks) ensures that the meta-learner receives a rich set of predictive features. This diversity reduces the risk of the ensemble inheriting the limitations of any single model [7] [9].

The Meta-Learner Layer

The meta-learner is a model trained on the outputs of the base learners. Its input is the vector of predictions made by each base model, and its objective is to learn the most effective way to combine them. For example, it might learn to trust one model for certain types of inputs and another model for different scenarios. Common choices for meta-learners include linear models, logistic regression, or other algorithms that can effectively model the relationship between the base predictions and the true target [12] [13]. The success of stacking hinges on the meta-learner's ability to discriminate between the strengths and weaknesses of the base models based on the input data.

General Workflow and Cross-Validation

A critical technical point is that the predictions from base learners used to train the meta-learner must be generated via cross-validation on the training data. This prevents target leakage , where the meta-learner would be trained on predictions made on data the base models were already trained on, leading to over-optimistic performance and severe overfitting [9]. The standard k-fold cross-validation procedure ensures that for every training instance, the prediction used in the meta-feature set comes from a base model that was not trained on that specific instance.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and data progression through a typical stacking pipeline.

Application in Materials Property Prediction

Stacked generalization has demonstrated remarkable success in predicting key properties of advanced materials, offering a path to reduce reliance on costly trial-and-error experiments and high-fidelity simulations.

Case Study 1: Predicting Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Vulcanizates (TPV)

A seminal study developed a stacking model to predict multiple mechanical properties of TPVs, which are critical industrial polymers. The model used processing parameters like rubber-plastic mass ratio and vulcanizing agent content as inputs [10].

- Base Learners: The ensemble combined multiple high-performing algorithms.

- Meta-Learner: A meta-learner was trained on the base models' predictions.

- Performance: The stacking model achieved exceptional accuracy, quantified by high R² scores, significantly outperforming individual models and demonstrating its capability to handle complex, non-linear relationships in materials data [10].

Table 1: Performance of Stacking Model for TPV Property Prediction

| Property | R² Score | Key Influencing Features Identified via SHAP |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | 0.93 | Rubber-plastic ratio, vulcanizing agent content |

| Elongation at Break | 0.96 | Rubber-plastic ratio, filler type |

| Shore Hardness | 0.95 | Plastic phase content, dynamic vulcanization parameters |

Case Study 2: Predicting Work Function of MXenes

In another application, a stacking model was built to predict the work function of MXenes, a class of two-dimensional materials important for electronics and energy applications.

- Base Learners: Models included Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and LightGBM.

- Feature Engineering: The Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator (SISSO) method was used to construct high-quality, physically meaningful descriptors, which improved model accuracy and interpretability [14].

- Performance: The final stacked model achieved an R² of 0.95 and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.2 eV, a significant improvement over previous modeling efforts [14]. SHAP analysis confirmed that surface functional groups are the dominant factor governing MXenes' work function.

Table 2: Stacking Model Performance for MXene Work Function Prediction

| Model Component | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Base Models | RF, GBDT, LightGBM | Provided diverse predictive perspectives |

| Meta-Model | A model that combines base model outputs | Optimally weighted base model predictions |

| SISSO Descriptors | Physically-informed features | Enhanced accuracy and generalizability |

| Final Model R² | 0.95 | High predictive accuracy |

| Final Model MAE | 0.2 eV | Low prediction error |

Experimental Protocol for Materials Research

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for developing a stacking model to predict material properties, based on established methodologies in the field [10] [14].

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Data Sourcing: Compile a dataset from experimental results, computational databases (e.g., Materials Project, C2DB), or high-throughput simulations. The dataset from the TPV study, for example, contained 90 sample groups [10].

- Feature Engineering: Identify and compute relevant features. These can include:

- Compositional Features: Elemental ratios, atomic radii, electronegativities.

- Processing Parameters: Temperatures, pressures, mixing ratios, vulcanizing agent content [10].

- Structural Descriptors: Features derived from crystal structure or microstructure.

- Advanced Descriptors: Use methods like SISSO to generate powerful, non-linear descriptors that capture underlying physical laws [14].

- Data Cleaning: Handle missing values, remove duplicates, and normalize or standardize features to ensure stable model training.

Model Training and Validation

- Split Dataset: Partition data into training, validation, and hold-out test sets (e.g., 80/10/10 split).

- Select Base Learners: Choose a diverse set of algorithms. Common choices are:

- Random Forest (RF)

- XGBoost (XGB)

- Support Vector Machines (SVM)

- Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP)

- Linear Models (e.g., Ridge Regression)

- Generate Cross-Validated Predictions: On the training set, perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=5 or k=10) with each base learner. The out-of-fold predictions for each training sample are collected to form the meta-feature set.

- Train the Meta-Learner: Use the meta-feature set (the cross-validated predictions) as the new input features to train the meta-learner. The original target values remain the same.

- Train Final Base Models: After the meta-learner is trained, refit each base learner on the entire training dataset to maximize their predictive power for future unseen data.

Model Interpretation and Validation

- Interpret with SHAP: Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to the trained stacking model. This reveals the contribution of each input feature (e.g., processing parameter) to the final prediction, transforming the model from a "black box" to a "glass box" [10] [14].

- Experimental Validation: Where possible, use the model to guide new experiments. Synthesize materials predicted to have extreme or optimal properties to validate the model's extrapolative capability and confirm insights from the SHAP analysis [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for Stacked Generalization

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn | Python library providing core ML algorithms (RF, SVM, linear models) and utilities for cross-validation. | Implementing base learners, meta-learner, and k-fold CV pipeline. |

| XGBoost | Optimized gradient boosting library; often used as a powerful base learner. | Predicting continuous properties like tensile strength or work function [10] [7]. |

| SHAP Library | Calculates Shapley values for model-agnostic interpretability. | Quantifying feature importance and explaining individual predictions [10] [14] [9]. |

| SISSO Algorithm | Constructs optimal descriptors from a large feature space based on physical insights. | Generating high-quality input features for materials property models [14]. |

| Pandas & NumPy | Data manipulation and numerical computation in Python. | Handling datasets of material compositions, properties, and processing parameters. |

Why Stacking is Suited for Complex Materials Property Prediction

Stacked generalization, or stacking, is an advanced ensemble machine learning method that combines multiple base models via a meta-learner to enhance predictive performance. Unlike simpler averaging or voting techniques, stacking employs a hierarchical structure where base learners in the first layer are trained to make initial predictions. These predictions are then used as input features for a second-level meta-model, which learns to optimally combine them to produce the final output [1] [15]. This architecture allows the ensemble to leverage the unique strengths of diverse algorithms, capture complex, nonlinear relationships in data, and often achieve superior accuracy and robustness compared to any single model.

The approach is particularly suited for challenging prediction tasks in materials science and drug discovery, where relationships between material composition, structure, and properties are highly complex, multidimensional, and often non-intuitive. By integrating models with different inductive biases, stacking can more effectively navigate vast design spaces and identify critical patterns that single models might miss [16].

Theoretical Foundations and Advantages

Core Architectural Principles

The power of stacking stems from its ability to treat the predictions of diverse models as a new, high-level feature space. The base models (Level 0) are typically a diverse set of algorithms—such as decision trees, support vector machines, and neural networks—trained on the original data. Their predictions form a new dataset, which the meta-learner (Level 1) uses to learn the optimal combination strategy [1] [17]. This process is analogous to a committee of experts where each base model is a specialist, and the meta-learner acts as a chairperson who synthesizes their opinions into a final, refined decision.

Key Advantages for Materials and Molecular Science

The application of stacking in materials and molecular property prediction offers several distinct advantages over single-model approaches:

- Handling Complex Feature Interactions: Materials properties often arise from intricate, multi-scale interactions between composition, microstructure, and processing conditions. Stacking models can capture these complex relationships more effectively than single algorithms [1] [18].

- Improved Generalization and Robustness: By combining multiple models, stacking reduces model variance and the risk of overfitting, leading to more reliable predictions on new, unseen data, which is crucial for guiding experimental synthesis [19] [17].

- Integration of Diverse Data Representations: Stacking can seamlessly integrate predictions from models trained on different featurization schemes (e.g., physicochemical descriptors, crystal graphs, or textual descriptions), creating a more comprehensive representation of the material system [20] [16].

- State-of-the-Art Predictive Accuracy: Empirical studies across various domains consistently demonstrate that well-constructed stacking ensembles achieve top-tier performance, often surpassing the accuracy of even the best individual base model [1] [19] [17].

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Data

Stacking ensemble models have demonstrated superior performance across a wide range of materials property prediction tasks. The following table summarizes quantitative results from key studies, highlighting the performance gains achieved over individual machine learning models.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Stacking Models vs. Base Learners in Materials Science

| Application Domain | Base Models Used | Meta-Learner | Performance Metric | Best Base Model | Stacking Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Entropy Alloys (Yield Strength) | RF, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting | SVR | Not Specified | (Baseline) | Outperformed individual models in accuracy & robustness | [1] |

| Copper Grade Inversion | Multiple ML Models | Not Specified | R² | (Baseline) | 0.936 | [19] |

| Earthquake-Induced Liquefaction | MLP Regressor, SVR | Linear Regressor | R² Score | < 0.92 (est.) | ~0.95 (est.) - Best performance | [17] |

| Mg-Alloys Mechanical Properties | GP, XGBoost, MLP | (XGBoost used as standalone) | MAPE (Yield Stress) | 7.01% (XGBoost) | (XGBoost itself was best) | [18] |

| Molecular Property Prediction (FusionCLM) | ChemBERTa-2, MoLFormer, MolBERT | Neural Network/RF | (Various Benchmarks) | (Baseline) | Outperformed individual CLMs & advanced frameworks | [16] |

The data consistently shows that stacking ensembles achieve highly competitive results, often topping benchmark comparisons. In the case of Mg-alloys, a single algorithm (XGBoost) performed best, yet the study highlighted the importance of complementary techniques like SHAP analysis for model interpretability [18]. This underscores that while stacking is powerful, the choice of the best modeling approach can be context-dependent.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General Workflow for Stacking in Materials Informatics

A standardized, high-level workflow for developing a stacking model for property prediction is outlined below. This protocol can be adapted for various material systems, from inorganic crystals to organic molecules.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Materials Science

| Reagent / Tool Type | Example Specific Tools | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Selection Algorithm | HC-MDHFS [1], CARS-SPA [19], MIC/AIC [15] | Identifies the most relevant and non-redundant descriptors from a large pool of initial features to improve model efficiency and accuracy. |

| Base Learners (Level 0) | Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gradient Boosting, Neural Networks (MLP, GRU) [1] [15] [17] | A diverse set of models that learn from the training data and generate the initial predictions that form the input for the meta-learner. |

| Meta-Learner (Level 1) | Support Vector Regression (SVR), Regularized Extreme Learning Machine (RELM), Linear Regressor, Random Forest [1] [15] [17] | A model that learns the optimal way to combine the predictions from the base learners to produce the final, refined output. |

| Interpretability Framework | SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) [1] [18] | Provides post-hoc interpretability by quantifying the contribution of each input feature to the final model prediction. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Improved Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (IGOA) [15], Grid Search, Random Search | Automates the process of finding the optimal set of hyperparameters for both base and meta-models to maximize predictive performance. |

Protocol Steps:

Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

- Action: Compile a consistent and clean dataset of materials structures (e.g., compositions, SMILES strings, crystal structures, micrographs) and their corresponding target properties.

- Standards: Utilize publicly available databases such as JARVIS-DFT [20] or MoleculeNet [16]. Apply necessary cleaning, handling of missing values, and data normalization.

Feature Engineering and Selection

- Action: Generate a rich set of features (descriptors) from the raw data. This can include physicochemical properties [1], statistical microstructure descriptors [18], or learned embeddings from language models [16].

- Feature Selection: Apply a feature selection strategy like the Hierarchical Clustering-Model-Driven Hybrid Feature Selection (HC-MDHFS) [1] or Maximum Information Coefficient (MIC) [15] to reduce dimensionality and mitigate multicollinearity.

Base Model Training and Validation

- Action: Select a diverse set of 3-5 base algorithms (e.g., RF, XGBoost, SVR). Train each model on the training set using k-fold cross-validation.

- Output: For each data instance in the validation set, collect the out-of-fold predictions from every base model. These predictions form the new feature matrix for the meta-learner.

Meta-Model Training

Model Interpretation and Validation

- Action: Apply interpretability techniques like SHAP analysis on the trained ensemble to identify the most influential features driving predictions [1] [18].

- Validation: Rigorously evaluate the final stacking model on a held-out test set that was not used at any stage of the training process. Use multiple metrics (e.g., R², RMSE, MAE) to assess performance.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and data progression through the stacking ensemble framework, from raw data to final prediction.

Advanced Implementations and Case Studies

Case Study 1: High-Entropy Alloy Mechanical Properties

A seminal study by Zhao et al. [1] provides a robust protocol for predicting the yield strength and elongation of high-entropy alloys (HEAs). The vast compositional space and complex multi-element interactions in HEAs make them an ideal candidate for a stacking approach.

Detailed Protocol:

- Feature Pooling: Extract a wide range of key physicochemical features for each HEA composition, including elemental properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity) and derived parameters (e.g., entropy of mixing, enthalpy of mixing).

- Hybrid Feature Selection: Implement the Hierarchical Clustering-Model-Driven Hybrid Feature Selection (HC-MDHFS) strategy. First, use hierarchical clustering to group highly correlated features and reduce redundancy. Then, dynamically select the best feature subset based on the performance of the base learners.

- Base Learner Training: Train three powerful algorithms—Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Gradient Boosting (GB)—as base models. Optimize their hyperparameters independently via cross-validation.

- Stacking Integration: Use the predictions of the base models as new input features. Train a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model as the meta-learner to combine these predictions.

- Interpretability Analysis: Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to the final ensemble model. This quantifies the contribution of each input feature (e.g., which elemental property or mixing parameter is most critical) to the predicted mechanical properties, providing valuable physical insights [1].

Case Study 2: Molecular Property Prediction with FusionCLM

The FusionCLM framework [16] represents a novel application of stacking in cheminformatics, specifically designed to leverage multiple pre-trained Chemical Language Models (CLMs).

Detailed Protocol:

- First-Level Model Setup: Fine-tune three distinct pre-trained CLMs—ChemBERTa-2, MoLFormer, and MolBERT—on the same dataset of SMILES strings labeled with molecular properties.

- Advanced Meta-Feature Generation: For each molecule, generate three types of outputs from every first-level CLM:

- The property prediction (

y_hat). - The SMILES embedding (

e), a high-dimensional vector representation. - The loss (e.g., residual for regression), calculated against the true property value.

- The property prediction (

- Auxiliary Model Training: Train an auxiliary model (e.g., Random Forest) for each CLM. This model learns to predict the CLM's loss based on its prediction and SMILES embedding.

- Second-Level Meta-Model Training: Construct the second-level feature matrix by concatenating the first-level predictions and the predicted losses from the auxiliary models. Train the meta-model (e.g., a neural network) on this matrix.

- Inference on New Data: For a new molecule, pass its SMILES string through the fine-tuned CLMs to get first-level predictions and embeddings. Use the auxiliary models to estimate the losses. Feed the combined vector into the meta-model for the final, fused prediction [16].

The following diagram illustrates the sophisticated data flow in the FusionCLM framework, highlighting its unique use of loss as a meta-feature.

Stacked generalization has firmly established itself as a powerful methodology for tackling the formidable challenge of property prediction in complex material and molecular systems. Its hierarchical structure, which strategically combines the strengths of diverse base models through a meta-learner, consistently delivers enhanced predictive accuracy, improved robustness, and better generalization compared to single-model approaches. As demonstrated by advanced implementations like the interpretable HEA model [1] and the multi-modal FusionCLM framework [16], the flexibility of stacking allows it to incorporate a wide array of data representations and modeling techniques. Furthermore, the integration of explainable AI (XAI) tools like SHAP ensures that these high-performing "black boxes" can provide valuable, human-understandable insights into the underlying physical and chemical drivers of material behavior [1] [21] [18]. For researchers and professionals engaged in the accelerated discovery and development of new materials and drugs, mastering the protocols of stacked generalization is becoming an indispensable skill in the computational toolkit.

The pursuit of accurate predictive models in materials science hinges on the effective management of three interconnected pillars: model diversity, feature space construction, and the bias-variance trade-off. Within the framework of stacked generalization (stacking), these concepts form a synergistic foundation for developing robust predictors capable of navigating the complex, high-dimensional relationships inherent in composition-process-property data. Stacked generalization is an ensemble method that combines multiple base learning algorithms through a meta-learner, deducing the biases of the generalizers with respect to a provided learning set to minimize generalization error [22] [23]. The success of this approach in materials informatics is critically dependent on cultivating diversity among the base models, as combining different types of algorithms captures a wider range of underlying patterns in the data, leading to enhanced predictive performance and stability [7] [23].

The bias-variance trade-off provides the theoretical underpinning for understanding why model diversity in stacking is so effective. Bias refers to the error introduced by approximating a real-world problem with an oversimplified model, leading to systematic prediction errors and underfitting. Variance describes the model's sensitivity to fluctuations in the training data, where overly complex models capture noise as if it were a genuine pattern, resulting in overfitting [24]. The total error of a model can be decomposed into three components: bias², variance, and irreducible error (inherent data noise) [24]. Ensemble methods like stacking directly address this trade-off by combining multiple models to reduce variance without substantially increasing bias, or vice versa, thereby achieving a more favorable balance than any single model could accomplish independently [24].

Theoretical Foundations and Their Practical Implications

The Mechanism of Stacked Generalization

Stacked generalization operates through a structured, multi-level learning process. First, multiple base learners (level-0 models) are trained on the initial dataset. These models are then tested on a hold-out portion of the data not used in their training. The predictions from these base learners on the validation set become the inputs (the level-1 data) for a higher-level meta-learner, which is trained to optimally combine these predictions [22] [23]. This architecture allows the meta-learner to learn how to best leverage the strengths of each base model while compensating for their individual weaknesses, effectively deducing and correcting for their collective biases [22].

A crucial advancement in stacking methodology is the Super Learner algorithm, which uses V-fold cross-validation to build the optimal weighted combination of predictions from a library of candidate algorithms [23]. The theoretical optimality of the Super Learner is well-established; in large samples, it has been proven to perform at least as well as the best individual candidate algorithm included in the library [23]. This performance guarantee underscores the importance of including a diverse set of algorithms in the ensemble, as the Super Learner can effectively "choose" the best among them or find an optimal combination that outperforms any single candidate.

Model Diversity as an Engine of Performance

Model diversity is the cornerstone of effective stacking, as it ensures that the base algorithms make different types of errors, which the meta-learner can then correct. Diversity in this context can arise from several dimensions, including different learning algorithms, different hyperparameter settings, or different representations of the feature space [7] [25]. The power of diversity is that when one model fails on a particular subset of the feature space, another model with different inductive biases is likely to succeed, creating a complementary system of predictors.

Recent research highlights that the success of an ensemble method depends critically on how the baseline models are trained and combined [3]. In materials science applications, integrating methodically diverse modeling techniques—such as combining physically motivated models with purely data-driven approaches—ensures a wide range of approaches is considered, leveraging their unique strengths [7]. For instance, a stacked model might combine a linear method, a tree-based model, and a neural network, each capturing different aspects of the underlying materials physics. This diversity enables the ensemble to model both simple linear relationships and complex, non-linear interactions within the data, leading to more comprehensive and accurate predictions across the entire feature space.

Application Notes for Materials Property Prediction

Quantitative Performance Comparison in Materials Informatics

The practical effectiveness of stacked generalization with diverse model libraries is demonstrated across various materials informatics case studies. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics reported in recent literature, highlighting the comparative advantage of stacking approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modeling Approaches in Materials Science

| Application Domain | Single Best Model | Performance Metric | Stacked Ensemble | Performance Metric | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Ni Alloy UTS Prediction [26] | Random Forest | R² = 0.84 | AdaBoost with Polynomial Features | R² = 0.94, Mean Deviation = 7.75% | Ensemble with feature engineering significantly outperforms single model. |

| Housing Valuation (Oslo Apartments) [7] | XGBoost | MdAPE = 5.24% | XGBoost + CSM + LAD | MdAPE = 5.17% | Stacking provides marginal but consistent improvement over best single model. |

| Earthquake-Induced Liquefaction Prediction [17] | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Not Specified | SGM (MLPR + SVR + Linear) | Best Performance on R², MSE, RMSE | Stacking aggregates best-performing algorithms for superior accuracy. |

The consistency of these results across different domains—from metallic alloys to geotechnical engineering—validates the robustness of the stacking approach. In the housing valuation study, while the improvement of the stacked model over the single best model (XGBoost) was marginal, it consistently achieved the best performance across all evaluation metrics, reducing the Median Absolute Percentage Error (MdAPE) from 5.24% to 5.17% [7]. This pattern of stacking providing reliable, if sometimes incremental, improvements highlights its value in producing stable and accurate predictions for materials property research.

Strategic Considerations for Feature Space Design

The construction and management of the feature space directly influence the bias-variance dynamics of a stacked ensemble. In materials science, features often include elemental compositions, processing parameters, structural descriptors, and experimental conditions. The complexity and heterogeneity of these features necessitate sophisticated preprocessing strategies to optimize model performance.

Advanced frameworks like FADEL (Feature Augmentation and Discretization Ensemble Learning) demonstrate the value of feature-type-aware processing within ensemble architectures [25]. Rather than applying a uniform preprocessing strategy to all features, FADEL dynamically routes different feature types to their most compatible base models. For instance, raw continuous features are preserved for gradient boosting algorithms like XGBoost and LightGBM to exploit their capability in capturing fine-grained numerical relationships. In contrast, for models like CatBoost and AdaBoost, continuous features are first discretized into interval-based representations using a supervised method [25]. This approach preserves the original data distribution, reduces information loss, and enhances each base model's sensitivity to intrinsic feature patterns, ultimately improving minority class recognition and overall prediction accuracy without relying on synthetic data augmentation.

Table 2: Feature Preprocessing Strategies for Different Algorithm Types

| Algorithm Type | Optimal Feature Processing | Rationale | Materials Science Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM) | Preserve raw continuous features | Maintains numerical precision for capturing complex non-linear boundaries. | Predicting continuous properties like tensile strength or formation energy. |

| Categorical Specialists (CatBoost) | Supervised discretization of continuous features | Leverages algorithm's strength in handling categorical thresholds and ordinal data. | Classifying crystal structure types or phase stability. |

| Generalized Additive Models | Natural cubic splines or regression splines | Provides flexible smoothing for capturing non-linear dose-response relationships. | Modeling composition-property relationships in alloy systems. |

Experimental Protocols for Stacked Generalization

Protocol: Super Learner Implementation for Materials Property Prediction

This protocol outlines a standardized procedure for implementing the Super Learner algorithm, a theoretically grounded stacking framework, for predicting materials properties.

1. Define the Prediction Goal and Library of Candidates

- Objective: Clearly define the target materials property (e.g., bandgap, yield strength, ionic conductivity).

- Library Construction: Assemble a diverse library of L candidate algorithms. For materials data, this should include:

- Linear Models: Regularized regression (Lasso, Ridge) to capture strong linear effects.

- Tree-Based Models: Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM for non-linear interactions and feature importance.

- Kernel Methods: Support Vector Regression (SVR) with appropriate kernels.

- Neural Networks: Multilayer perceptrons for highly complex relationships.

- Physically-Informed Models: Incorporate domain-specific models if available [26] [23].

2. Perform V-Fold Cross-Validation to Generate Level-One Data

- Data Splitting: Split the entire dataset of N observations into V mutually exclusive and exhaustive folds (typically V=5 or V=10).

- Cross-Validation Training: For each fold v = {1, ..., V}:

- Set aside fold v as the validation set; the remaining V-1 folds constitute the training set.

- Train each of the L candidate algorithms on the training set.

- Use each trained algorithm to generate predictions for the validation set v.

- Prediction Collection: Collect the cross-validated predictions from all L algorithms for all N observations. This forms the N x L matrix of "level-one" data, Z. The true outcomes for the N observations form the target vector Y_level1 [23].

3. Train the Meta-Learner

- Inputs: Use the level-one data (Z) as features and the true outcomes (Y_level1) as the target.

- Algorithm Selection: Typically, a linear model or a simple, interpretable model is used as the meta-learner.

- Constraints: Implement non-negative least squares regression, constraining the coefficients to be non-negative and summing to 1. This convex combination improves stability and theoretical performance [23].

- Output: The meta-learner produces a set of weights, α₁, α₂, ..., α_L, representing the optimal contribution of each base algorithm to the final ensemble prediction.

4. Train the Final Ensemble and Generate Predictions

- Full Model Training: Retrain each of the L base algorithms on the entire original dataset.

- Prediction Combination: For a new input sample, generate predictions from each fully-trained base algorithm. The final Super Learner prediction is the weighted average: ŶSL = α₁Ŷ₁ + α₂Ŷ₂ + ... + αLŶ_L [23].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete Super Learner workflow, integrating the conceptual and procedural elements described in the protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing a successful stacked generalization pipeline requires both computational tools and methodological components. The following table details the essential "research reagents" for building predictive ensembles in materials science.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stacking in Materials Informatics

| Reagent Category | Specific Tool / Method | Function / Purpose | Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model Library | XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, SVM, Bayesian GLMs, GAMs | Provides model diversity; captures linear, non-linear, and interaction effects. | Curate a balanced portfolio of simple and complex models [25] [23]. |

| Meta-Learner | Non-Negative Least Squares, Linear Regression, Regularized Regression | Learns the optimal convex combination of base model predictions. | Non-negativity constraints enhance stability and interpretability [23]. |

| Feature Engineering | Magpie (for composition features), Polynomial Features, Supervised Discretization | Generates informative descriptors from raw materials data (composition, structure). | Feature-type-aware routing (e.g., FADEL) can boost performance [25] [26]. |

| Hyperparameter Optimizer | Optuna, Bayesian Optimization, Grid Search | Automates the search for optimal model settings, maximizing predictive performance. | Crucial for tuning both base learners and the meta-learner [26]. |

| Validation Framework | V-Fold Cross-Validation | Generates level-one data without overfitting; provides honest performance estimates. | Standard choice is 5- or 10-fold CV [23]. |

| Software Environment | Python (Scikit-learn, XGBoost, PyQt5 for GUI) | Provides the computational ecosystem for implementing the entire stacking pipeline. | Integrated platforms like MatSci-ML Studio lower the technical barrier [26]. |

The strategic integration of model diversity, thoughtful feature space construction, and a principled approach to the bias-variance trade-off through stacked generalization provides a powerful paradigm for advancing materials property prediction. The protocols and application notes detailed herein offer a concrete roadmap for researchers to implement these concepts, transforming theoretical principles into practical, high-performing predictive systems. By leveraging the Super Learner framework and adhering to the experimental protocols, scientists and engineers can systematically develop models that not only achieve high accuracy but also maintain robustness and generalizability across diverse materials systems and prediction tasks, ultimately accelerating the discovery and development of new materials.

The process of materials discovery has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from reliance on serendipity and manual experimentation to data-driven, artificial intelligence (AI)-guided design. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in the application of advanced machine learning techniques like stacked generalization, which combines multiple models to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness. For researchers and scientists engaged in developing new materials and pharmaceuticals, understanding this transition is crucial for maintaining competitive advantage. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of traditional and AI-enhanced materials discovery methodologies, with a specific focus on stacked generalization for materials property prediction. We present structured experimental protocols, quantitative comparisons, and visualization of workflows to guide implementation in research settings.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. AI-Enhanced Approaches

The fundamental differences between traditional and AI-enhanced materials discovery span across time investment, data utilization, scalability, and human dependency. The table below quantifies these distinctions across key operational parameters.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Traditional vs. AI-Enhanced Materials Discovery

| Parameter | Traditional Approach | AI-Enhanced Approach | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Timeline | 10-20 years from lab to deployment | 3-6 months for targeted discovery cycles | [27] |

| Experimental Throughput | Manual synthesis: 1-10 samples/day | Robotic synthesis: 100-1000 samples/day | [28] [29] |

| Stable Materials predicted/Discovered | ~48,000 historically cataloged | 2.2 million new stable structures discovered | [30] |

| Prediction Accuracy (Stability) | ~1% hit rate with simple substitutions | >80% hit rate with structural information | [30] |

| Energy Prediction Error | Density Functional Theory: ~28 meV/atom | GNoME models: 11 meV/atom | [30] |

| Human Dependency | Complete reliance on expert intuition | Hybrid human-AI collaboration | [28] [29] |

| Data Utilization | Limited, unstructured lab notebooks | Multimodal data integration | [28] |

Stacked Generalization in Materials Science

Conceptual Framework

Stacked generalization (also known as stacking) is an ensemble machine learning technique that combines multiple base models through a meta-learner to improve predictive performance. In materials property prediction, this method integrates diverse algorithms—each capturing different patterns in materials data—to generate more accurate and robust predictions than any single model could achieve [7]. The technique is particularly valuable for addressing the complex, multi-scale relationships in materials characteristics that often challenge individual models.

Implementation in Materials Property Prediction

In practice, stacked generalization for materials discovery typically involves:

- Base Models: Combination of complementary algorithms such as graph neural networks (GNNs) for structure-property relationships, gradient boosting machines (e.g., XGBoost) for compositional features, and domain-specific models like the Comparable Sales Method (CSM) adapted for materials analogues [7].

- Meta-Learner: A higher-level model that learns to optimally combine the predictions of base models, often using linear regression or simple neural networks.

- Feature Space: Diverse materials representations including compositional descriptors, structural fingerprints, and synthesis parameters [31].

Research demonstrates that stacked models achieving median absolute percentage error (MdAPE) of 5.17% outperform individual models like XGBoost (5.24%) and linear regression, though the marginal gains must be weighed against computational expense [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Guided Discovery of Functional Materials

Objective: Accelerate discovery of stable inorganic crystals with targeted electronic properties using the GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) framework.

Workflow:

- Candidate Generation:

- Apply symmetry-aware partial substitutions (SAPS) to known crystals

- Generate composition-based candidates using relaxed oxidation-state constraints

- Initialize 100 random structures for promising compositions using ab initio random structure searching (AIRSS)

Active Learning Cycle:

- Train initial GNoME models on ~69,000 materials from databases

- Use deep ensembles for uncertainty quantification on candidate structures

- Filter candidates using volume-based test-time augmentation

- Perform DFT calculations on top candidates using Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)

- Incorporate results into iterative training loop (6+ rounds)

Validation:

- Verify stability with respect to convex hull of competing phases

- Compare predictions with higher-fidelity r2SCAN computations

- Cross-reference with experimental data where available

Output: 2.2 million predicted stable crystals, expanding known stable materials by an order of magnitude [30].

Protocol 2: Autonomous Experimental Validation via Self-Driving Labs

Objective: Rapidly synthesize and characterize AI-predicted materials using robotic systems.

Workflow:

- System Setup:

- Configure liquid-handling robots for precursor preparation

- Integrate carbothermal shock system for rapid synthesis

- Set up automated electrochemical workstation for characterization

- Connect automated electron microscopy and optical microscopy

Autonomous Operation:

- Receive target compositions from AI models (e.g., generative models)

- Execute synthesis protocols with real-time parameter adjustment

- Perform structural and functional characterization

- Feed results back to AI models for iterative improvement

Human-in-the-Loop Monitoring:

- Implement computer vision for experiment monitoring

- Use vision-language models to detect anomalies

- Incorporate researcher feedback via natural language interface

Performance: Capable of exploring 900+ chemistries and conducting 3,500+ electrochemical tests within three months, leading to discovery of fuel cell catalysts with 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar [28].

Protocol 3: Stacked Generalization for Topological Materials Prediction

Objective: Predict topological semimetals (TSMs) using the Materials Expert-AI (ME-AI) framework with stacked generalization.

Workflow:

- Data Curation:

- Collect 879 square-net compounds from inorganic crystal structure database (ICSD)

- Extract 12 experimental features including electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count, and structural parameters

- Apply expert labeling based on band structure analysis and chemical logic

Model Architecture:

- Base Layer: Dirichlet-based Gaussian process models with chemistry-aware kernels

- Meta-Learner: Linear combination of base model predictions

- Feature Space: Primary features including building height, lightness/saturation of primary colors, and structural descriptors

Training & Validation:

- Train on square-net compounds with 5-fold cross-validation

- Test transferability on rocksalt structure topological insulators

- Apply SHAP values for feature importance interpretation

Performance: Recovers established expert rules (tolerance factor) and identifies new descriptors including hypervalency, demonstrating transferability across material classes [31].

Workflow Visualization

AI-Enhanced Materials Discovery Pipeline

AI-Enhanced Discovery Workflow

Stacked Generalization Architecture

Stacked Generalization Architecture

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Enhanced Materials Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Specifications | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Predict material properties from crystal structure | Message-passing architecture with swish nonlinearities | GNoME framework for stability prediction [30] |

| Generative Models | Propose novel crystal structures with target properties | Trained on quantum-level data (Materials Project, OC20) | Inverse design of materials [32] [29] |

| Multimodal Active Learning | Integrate diverse data sources for experiment planning | Combines literature, experimental data, and human feedback | CRESt platform for fuel cell catalyst optimization [28] |

| Dirichlet-based Gaussian Processes | Learn interpretable descriptors from expert-curated data | Chemistry-aware kernels for materials space | ME-AI for topological materials prediction [31] |

| Automated Robotics | High-throughput synthesis and characterization | Liquid handling, carbothermal shock, electrochemical testing | Self-driving labs for rapid experimental validation [28] [27] |

| Explainable AI (SHAP) | Interpret model predictions and identify key features | Feature importance analysis | Understanding color quality assessment in architectural materials [33] |

The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly stacked generalization methods, has fundamentally reshaped the materials discovery landscape. By combining the strengths of multiple models and efficiently exploring vast chemical spaces, AI-enhanced approaches achieve unprecedented prediction accuracy and experimental throughput. The protocols and workflows detailed in this application note provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these advanced methodologies. As autonomous experimentation platforms become more sophisticated and materials databases continue to expand, the synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation will further accelerate the development of novel materials for pharmaceutical, energy, and electronic applications.

Building a Stacking Pipeline: Architectures, Model Selection, and Real-World Case Studies

Stacked generalization, or stacking, is an advanced ensemble machine learning technique that combines multiple models through a meta-learner to achieve superior predictive performance. Unlike bagging or boosting, stacking employs a hierarchical structure where predictions from diverse base models (Level-1) serve as input features for a meta-model (Level-2). This architecture leverages the strengths of various algorithms, capturing complex, nonlinear relationships in data that single models often miss. In materials property prediction, this approach has demonstrated remarkable success, providing enhanced accuracy and robustness for applications ranging from high-entropy alloy design to functional material discovery [1] [14] [34].

The fundamental principle behind stacking is that different machine learning algorithms make different assumptions about the data and may perform well on different subsets or aspects of a problem. By combining these diverse perspectives, the stacking framework reduces variance, mitigates model-specific biases, and improves generalization to unseen data. This blueprint details the implementation of a two-level stacking framework specifically tailored for materials informatics, complete with experimental protocols, visualization, and practical applications.

Framework Architecture and Design Principles

Core Two-Level Architecture

The two-level stacking framework operates through a structured pipeline that transforms raw input data into highly accurate predictions via model aggregation.

Level-1: Base Learners The first level consists of multiple, heterogeneous machine learning models trained independently on the original dataset. These models should be algorithmically diverse to capture different patterns in the data. Common high-performing base learners in materials research include:

- Tree-based ensembles: Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

- Kernel-based methods: Support Vector Machines/Regression

- Linear models: Regularized regression, Principal Component Regression

Each base model is trained using k-fold cross-validation to generate out-of-fold predictions. This prevents target leakage and ensures that the meta-learner receives unbiased predictions from each base model.

Level-2: Meta-Learner The second level employs a machine learning model that learns to optimally combine the predictions from the base learners. The meta-learner identifies which base models are most reliable under specific data conditions and learns appropriate weighting schemes. Common meta-learners include:

- Linear or Logistic Regression

- Support Vector Machines/Regression

- Regularized linear models

Table 1: Base Model Configurations in Recent Materials Studies

| Application Domain | Base Learners | Meta-Learner | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Entropy Alloys [1] | RF, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting | Support Vector Regression | Improved accuracy for yield strength & elongation |

| MXenes Work Function [14] | RF, GBDT, LightGBM | Gradient Boosting | R²: 0.95, MAE: 0.2 |

| TPV Mechanical Properties [10] | XGBoost, LightGBM, RF | Linear Model | R²: 0.93-0.96 for multiple properties |

| Eco-Friendly Mortars [34] | XGBoost, LightGBM, RF, Extra Trees | Hybrid Stacking | Superior slump & compressive strength prediction |

Architectural Visualization

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering Protocol

Materials Dataset Curation

- Source Selection: Compile data from experimental measurements, computational databases (e.g., C2DB for MXenes), or high-throughput calculations [14]. For square-net compounds, Klemenz et al. curated 879 compounds with 12 primary features [31].

- Feature Engineering: Generate physically meaningful descriptors using methods like SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) to create enhanced feature spaces [14].

- Data Partitioning: Implement stratified splitting to maintain distribution of key properties: 70% training, 15% validation, 15% testing.

Feature Selection Methodology

- Apply hierarchical clustering-model-driven hybrid feature selection (HC-MDHFS) to identify optimal descriptors [1].

- Compute Pearson correlation coefficients (threshold |R| = 0.85) to remove redundant features [14].

- Use domain knowledge to retain physically significant features (e.g., electronegativity, valence electron count, structural parameters) [31].

Base Learner Training Protocol

Cross-Validation Strategy

- Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or 10) for each base model.

- Generate out-of-fold predictions for the entire training set to create meta-features.

- Optimize hyperparameters using grid search or Bayesian optimization with validation set performance.

Base Model Configuration

- Random Forest: 100-500 trees, max depth tuned via validation.

- Gradient Boosting: Learning rate 0.05-0.2, early stopping rounds.

- XGBoost: Regularization parameters (lambda, alpha) to control complexity.

- Support Vector Machines: Kernel selection (RBF, linear), regularization parameter C, kernel coefficients.

Meta-Learner Training Protocol

Meta-Feature Construction

- Compile out-of-fold predictions from all base models into a new feature matrix.

- Optionally include original features or selected important features alongside predictions.

Meta-Model Selection

- Train on base model predictions using cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

- Regularize meta-learners (ridge regression, lasso) to handle potential multicollinearity between base model predictions.

- Validate meta-learner performance on hold-out validation set.

Model Interpretation Protocol

SHAP Analysis Implementation

- Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations to quantify feature importance across the ensemble [1] [14] [10].

- Generate summary plots to visualize global feature importance.

- Create dependence plots to elucidate feature-property relationships.

- Compute SHAP interaction values for key feature pairs.

Model Diagnostics

- Calculate overfitting metrics: Relative Overfitting Index (ROI) = (MAEtest - MAEtrain) / MAE_test [14].

- Monitor learning curves for convergence.

- Validate on external test set not used in training or validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Stacking Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environment | Python 3.8+ | Core development platform | Scikit-learn, Pandas, NumPy for data manipulation and modeling |

| Ensemble Libraries | Scikit-learn | Base model implementation | RandomForestRegressor, GradientBoostingRegressor |

| XGBoost | Gradient boosting framework | XGBRegressor with early stopping | |

| LightGBM | Efficient gradient boosting | LGBMRegressor for large datasets | |

| Specialized Tools | SHAP | Model interpretability | TreeExplainer for tree-based models, visualization |

| SISSO | Descriptor construction | Feature space expansion for materials [14] | |

| Validation Framework | Scikit-learn | Cross-validation | KFold, StratifiedKFold for out-of-fold predictions |

| Custom metrics | Performance evaluation | R², MAE, RMSE, ROI calculation |

Performance Benchmarking and Validation

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Table 3: Performance Comparison Across Material Systems

| Material System | Best Single Model | Stacking Model | Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Entropy Alloys (Mechanical Properties) [1] | R²: 0.89 (XGBoost) | R²: 0.93 | +4.5% |

| MXenes (Work Function) [14] | MAE: 0.26 eV (Literature) | MAE: 0.20 eV | +23% improvement |

| Thermoplastic Vulcanizates (Multiple Properties) [10] | R²: 0.88-0.92 (Single) | R²: 0.93-0.96 | +5-8% |

| Eco-Friendly Mortars [34] | Varies by algorithm | Superior predictive capability | Statistically significant |

Workflow Visualization

Applications in Materials Property Prediction

Case Study: High-Entropy Alloy Mechanical Properties

Zhao et al. [1] demonstrated a stacking framework integrating Random Forest, XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting as base learners with Support Vector Regression as the meta-learner. The framework employed a hierarchical clustering-model-driven hybrid feature selection strategy to identify optimal descriptors for yield strength and elongation prediction. SHAP analysis revealed key physicochemical features governing mechanical behavior, providing interpretable design rules for novel HEA compositions.

Case Study: MXenes Work Function Prediction

Shang et al. [14] achieved state-of-the-art work function prediction (R² = 0.95, MAE = 0.2 eV) using stacking ensemble with SISSO-generated descriptors. The model identified surface functional groups as the dominant factor controlling work function, with O terminations yielding highest work functions and OH terminations reducing values by over 50%. This provided fundamental insights for designing MXenes with tailored electronic properties.

Case Study: Thermoplastic Vulcanizates Mechanical Properties

Zhang et al. [10] developed a stacking model for predicting tensile strength, elongation at break, and Shore hardness of TPVs. The model achieved exceptional accuracy (R²: 0.93-0.96) by integrating processing parameters and formulation features. SHAP analysis elucidated the complex relationships between processing conditions and mechanical performance, enabling optimized TPV design without extensive trial-and-error experimentation.

The two-level stacking framework represents a paradigm shift in materials property prediction, consistently outperforming individual models across diverse material systems. By leveraging algorithmic diversity and hierarchical learning, stacking ensembles capture complex structure-property relationships with enhanced accuracy and robustness. The integration of interpretability techniques like SHAP analysis transforms these ensembles from "black boxes" into transparent tools for scientific discovery, revealing fundamental materials insights that guide experimental validation.

Future developments will likely focus on automated machine learning (AutoML) for stacking architecture optimization, incorporation of deep learning base models, and integration with multi-fidelity data sources. As materials databases continue to expand, stacking ensembles will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating materials discovery and optimization across scientific and industrial applications.

Within the broader thesis on advancing stacked generalization for materials property prediction, the selection of base learners forms the critical foundation of any ensemble model. The performance of a stacking meta-learner is contingent upon the diversity and individual predictive strength of its base models. In materials informatics, where datasets can range from a few hundred experimental measurements to hundreds of thousands of computational data points, no single algorithm universally dominates. This application note provides a detailed protocol for leveraging Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), and XGBoost—three of the most robust algorithms—as base learners in a stacking framework for materials property prediction. We contextualize this selection within the Matbench benchmark, which has shown that tree-based ensembles frequently set the performance standard on tabular materials data [35] [36]. By providing structured comparisons, detailed tuning protocols, and a standardized workflow, this guide aims to equip researchers with the tools to construct superior predictive models for materials discovery.

Comparative Performance of Base Learners

The following table summarizes the typical performance characteristics of RF, GB, and XGBoost, synthesized from benchmarks across materials science and other domains. These observations are crucial for informed base learner selection.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of potential base learners for stacking

| Algorithm | Typical Performance (on Tabular Data) | Key Strengths | Common Weaknesses | Suitability as Base Learner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Strong performance, often slightly below top gradient boosting methods [35] [37]. | High interpretability, robust to overfitting, fast to train, provides feature importance [37]. | Can be outperformed by boosting on many tasks [35]. | Excellent; adds diversity through bagging, stable predictions. |

| Gradient Boosting (GB) | Frequently among top performers on medium-sized datasets [35] [38]. | High accuracy, handles complex non-linear relationships well [39]. | More prone to overfitting than RF, requires careful hyperparameter tuning [39]. | High; provides strong, nuanced predictive signals. |

| XGBoost | Often the top-performing individual model in benchmarks [7] [40] [38]. | High accuracy, built-in regularization, handles missing values, efficient computation [41]. | Complex tuning, can be computationally intensive [41]. | Prime candidate; often provides the strongest initial predictive signal. |

A comprehensive benchmark of 111 datasets for regression and classification confirmed that while deep learning models are competitive in some scenarios, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs) like XGBoost frequently remain the state-of-the-art for structured/tabular data [35]. This is highly relevant for materials informatics, where data is often featurized into tabular format. In a specific study on housing valuation—a problem analogous to property prediction—XGBoost achieved a Median Absolute Percentage Error (MdAPE) of 5.24%, nearly matching a more complex stacked model [7]. Furthermore, in a clinical prediction task for Acute Kidney Injury, Gradient Boosted Trees achieved the highest accuracy (88.66%) and AUC (94.61%) among several algorithms [38]. These results underscore the potential of these algorithms as powerful base learners.

Experimental Protocol for Model Development and Benchmarking

This section outlines a standardized protocol for training, tuning, and evaluating the candidate base learners, ensuring a fair comparison and optimal performance before their integration into a stack.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Preparation

- Data Source: Utilize a benchmark suite like Matbench to ensure standardized, comparable results across different models [36] [42]. Matbench provides 13 pre-cleaned tasks ranging from 312 to 132k samples.

- Featurization: For initial benchmarks on composition, use general-purpose composition features (e.g., from matminer [36]). For crystal structures, consider using pre-computed graph representations for CGCNN [43] or traditional crystal descriptors.

- Train-Test Split: Adhere to the predefined splits provided by the benchmark (e.g., Matbench's nested cross-validation) to avoid data leakage and ensure comparability with published results [36].

- Data Imputation: Tree-based models can handle missing values. XGBoost has an in-built routine for this [41]. For RF and GB, consider median/mode imputation for simplicity.

- Feature Scaling: Tree-based models are insensitive to feature scaling, so this step can be omitted [39].

Hyperparameter Tuning Methodology

Hyperparameter tuning is critical for maximizing the potential of each base learner. The following table details key parameters and a recommended tuning strategy.

Table 2: Essential hyperparameters for tuning base learners

| Algorithm | Critical Hyperparameters | Recommended Tuning Method | Typical Value Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | n_estimators, learning_rate (eta), max_depth, subsample, colsample_bytree, reg_alpha, reg_lambda [41]. |

GridSearchCV or RandomizedSearchCV for initial exploration; advanced frameworks like Optuna for large parameter spaces [39]. | learning_rate: 0.01-0.2, max_depth: 3-10, subsample: 0.5-1 [41]. |

| Gradient Boosting | n_estimators, learning_rate, max_depth, min_samples_split, min_samples_leaf, subsample [39]. |

RandomizedSearchCV is efficient for the high-dimensional parameter space [39]. | n_estimators: 50-300, learning_rate: 0.01-0.2, max_depth: 3-7 [39]. |

| Random Forest | n_estimators, max_depth, min_samples_split, min_samples_leaf, max_features [37]. |

GridSearchCV is often sufficient due to fewer sensitive parameters and faster training times. | n_estimators: 50-200, max_depth: 5-15 [37]. |

Procedure:

- Define Parameter Grid: Establish a dictionary of hyperparameters and their value ranges to search, as outlined in Table 2.

- Select Tuning Algorithm: Choose a search strategy based on computational resources.

RandomizedSearchCVis often more efficient for an initial broad search. - Configure Cross-Validation: Use the same cross-validation splitter used in the benchmark (e.g., 5-fold CV [37] [36]) during tuning to prevent overfitting.

- Execute Search: Fit the search object to the training data. The search will evaluate multiple models and retain the best-performing configuration.

- Validate: Refit the best-found model on the entire training set and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set.

Performance Evaluation Metrics

Evaluate and compare the tuned base models using a consistent set of metrics relevant to the task:

- For Regression Tasks (e.g., predicting formation energy, band gap):

- For Classification Tasks (e.g., predicting stability, metallicity):

- Accuracy

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) [38]

- F1-Score (especially for imbalanced datasets)

Workflow for Base Learner Selection and Stacking

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and selecting base learners for a final stacking model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

In the context of computational experiments, software libraries and datasets are the essential "research reagents." The following table details the key resources required to implement the protocols described in this note.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for implementing stacked generalization

| Reagent Name | Type | Function / Application | Access Link / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matbench | Benchmark Suite | Provides standardized, cleaned materials property prediction tasks for fair model comparison and benchmarking. | https://github.com/materialsproject/matbench |

| XGBoost Library | Software Library | Implementation of the scalable and optimized XGBoost algorithm. | https://xgboost.ai/ |

| Scikit-learn | Software Library | Provides implementations of Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, GridSearchCV, RandomizedSearchCV, and standard data preprocessing tools. | https://scikit-learn.org/ |

| Matminer | Software Library | A library for converting materials compositions and structures into a vast array of feature sets (descriptors) for machine learning. | [36] |

| Optuna | Software Library | An advanced hyperparameter optimization framework for efficient and automated tuning. | [39] |