Spectroscopic Validation of Metal-Ligand Bonding: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern spectroscopic techniques for validating metal-ligand bonding character, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Spectroscopic Validation of Metal-Ligand Bonding: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern spectroscopic techniques for validating metal-ligand bonding character, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational bonding concepts in coordination complexes, details advanced methodological applications across pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical fields, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents robust validation frameworks using complementary biophysical techniques. The content synthesizes current research to offer practical insights for characterizing metal complexes in drug discovery, metallodrug development, and quality control processes.

Understanding Metal-Ligand Bonding Fundamentals in Coordination Chemistry

Principles of Covalent Three-Center, Two-Electron M–H–B Bonding

Three-center, two-electron (3c–2e) bonds represent a fundamental class of electron-deficient chemical bonds where three atoms share two electrons. In these bonding systems, the combination of three atomic orbitals forms three molecular orbitals: one bonding, one non-bonding, and one anti-bonding. The two electrons occupy the bonding orbital, creating a net bonding effect that constitutes a chemical bond among all three atoms [1]. This bonding model is particularly relevant in metal borohydride complexes, where unconventional metal-ligand bonding occurs via three-center, two-electron M–H–B bonds, implying significant delocalization of electron density over all three atoms [2]. The principles of 3c–2e bonding have become increasingly important in understanding the behavior of inorganic polymers, cluster compounds, and catalytic systems where traditional two-center bonds provide insufficient explanation for observed bonding behavior and material properties [3].

The molecular orbital description of a 3c–2e bond reveals why this configuration is stable despite the electron deficiency. When three atomic orbitals combine, they form a set of three molecular orbitals with different energy levels. The bonding molecular orbital is substantially lower in energy, the non-bonding orbital remains at approximately the same energy level as the original atomic orbitals, and the anti-bonding orbital is higher in energy. The two electrons fill the bonding orbital, leaving the non-bonding and anti-bonding orbitals vacant. This arrangement results in a net stabilization of the system, particularly when the bonding orbital is shifted toward two of the three atoms rather than being spread equally among all three, as commonly observed in many 3c–2e bonded systems [1].

Fundamental Principles of M–H–B Bonding

Electronic Structure and Bonding Theory

In M–H–B (Metal-Hydrogen-Boron) three-center bonding, the electron delocalization implies significant orbital mixing between the metal and boron atoms, though the degree of this mixing has historically been difficult to assess by direct experimental means [2]. The bonding can be understood through molecular orbital theory, where atomic orbitals from the metal, hydrogen, and boron combine to form molecular orbitals delocalized across all three centers. The resulting bonding situation allows electron-deficient elements like boron to achieve higher coordination numbers and greater stability than would be possible with conventional two-center, two-electron bonds.

The unique aspect of M–H–B bonding lies in the covalent nature of the interaction between the metal and boron through the bridging hydrogen atom. Theoretical calculations suggest significant electron density resides in the bonding molecular orbital that spans all three atoms. This delocalized bonding orbital provides stability to the complex while maintaining the electron-deficient character typical of boron-containing compounds. The bond order for each M–H and H–B interaction in these bridges is typically less than one, explaining why these bonds are often weaker and longer than terminal M–H or B–H bonds [1].

Comparative Analysis of 3c–2e Bond Systems

The following table compares key characteristics of different three-center, two-electron bond systems, highlighting the distinctive features of M–H–B bonding:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Three-Center, Two-Electron Bond Systems

| Bond System | Representative Example | Bond Geometry | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M–H–B | Zr(BH₄)₄, Hf(BH₄)₄ | Angular | Significant covalent character with electron delocalization; bond lengths intermediate between terminal M–H and B–H bonds | Metal borohydride complexes; hydrogen storage materials |

| B–H–B | B₂H₆ (Diborane) | Angular | Electron-deficient bonding; bridging H atoms; B–H bridging bonds longer and weaker than terminal B–H bonds | Borane chemistry; reducing agents in organic synthesis |

| M–H–M | Agostic complexes | Angular | Interaction between electron-deficient metal center and C–H bond; often observed as reaction intermediates | Organotransition metal chemistry; catalytic reaction intermediates |

| C–H–C | Carbonium ions (e.g., C₂H₇⁺) | Angular | Hyperconjugation; asymmetrical bonding; important in carbocation rearrangement reactions | Reaction intermediates in organic chemistry; hydrocarbon chemistry |

The M–H–B system distinguishes itself through the significant covalent mixing between the metal and boron atoms, as recently demonstrated experimentally using boron K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) [2]. This covalent character differentiates M–H–B bonds from more ionic or dative bonding scenarios often encountered in coordination chemistry.

Spectroscopic Validation of M–H–B Bonding

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Advanced spectroscopic techniques have enabled direct experimental verification of covalent M–H–B bonding, providing insights that were previously inaccessible. The following experimental protocols represent state-of-the-art methodologies for characterizing these bonding interactions:

Boron K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

Principle: This technique probes unoccupied orbitals by measuring the excitation of boron 1s electrons to higher energy levels. The pre-edge features in the spectrum provide direct evidence of covalent mixing between boron and metal orbitals [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize metal borohydride complexes with substituents that attenuate volatility (e.g., benzyl, phenyl, mesityl derivatives for Zr and Hf borohydrides). Conduct all manipulations under inert atmosphere using Schlenk line or glovebox techniques [2].

- Instrument Conditions: Utilize synchrotron radiation sources under ultra-high vacuum conditions (<10⁻⁸ torr). Employ fluorescence detection mode for bulk samples or total electron yield for surface-sensitive measurements [2].

- Data Collection: Acquire spectra across the boron K-edge (190-220 eV energy range) with high energy resolution. Record multiple scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Theoretical Calculations: Perform time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations to assign spectral features. Compare experimental pre-edge features with calculated transitions to identify B 1s → M–H–B π* transitions [2].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the pre-edge feature intensity and energy position. Higher intensity indicates greater covalency in the M–H–B bond due to increased boron p-orbital character in the unoccupied molecular orbitals.

Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR and Raman)

Principle: Infrared and Raman spectroscopy detect changes in vibrational modes that reflect bonding interactions and molecular symmetry.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare pure samples as solids or solutions in appropriate solvents. For solution studies, use sealed cells with controlled path length.

- IR Spectroscopy: Use Fourier-transform IR (FTIR) spectrometer with attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory for solid samples. Collect spectra in the range of 400-4000 cm⁻¹ with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, averaging multiple scans [4].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Employ Nd:YAG laser operating at 532 nm with appropriate filters. Use microscope attachment with 50× magnification objective. Set laser power to 0.8 mW to avoid sample degradation. Accumulate 50 scans with 1-2 second exposure times [4].

- Spectral Analysis: Identify B–H stretching and bending modes. Compare frequencies and intensities with computational predictions. Red shifts or broadening of bands indicate participation in three-center bonding [4].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Principle: NMR chemical shifts are sensitive to local electronic environments, providing information about bonding and molecular structure.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve complexes in deuterated solvents under inert atmosphere. Use high-purity, dry solvents to prevent decomposition.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire ¹¹B NMR spectra using appropriate pulse sequences and relaxation delays. Reference chemical shifts to external standards (e.g., BF₃·OEt₂ at 0 ppm) [2].

- Data Analysis: Correlate chemical shifts with M–B distances and bonding character. Downfield shifts often indicate more covalent character in M–H–B bonds.

Spectroscopic Data and Interpretation

The application of these spectroscopic methods to Zr and Hf borohydride complexes has yielded quantitative data supporting the covalent nature of M–H–B bonding:

Table 2: Spectroscopic Signatures of M–H–B Bonding in Selected Complexes

| Complex | B–H Stretching Frequency (cm⁻¹) | ¹¹B NMR Chemical Shift (ppm) | B K-edge Pre-edge Energy (eV) | Pre-edge Intensity | M–B Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Zr(BH₄)₄] | ~2500 (bridging) | Not specified | ~192.5 | Strong | ~2.45 |

| [Hf(BH₄)₄] | Similar to Zr analogs | Not specified | ~192.6 | Strong | ~2.42 |

| Zr(PhBH₃)₄ | Slightly shifted vs. parent | Correlation observed | Not specified | Not specified | Correlation with δ¹¹B |

| Traditional Ionic Borohydride | >2500 | Upfield | No pre-edge feature or very weak | Minimal | >2.60 |

The pre-edge feature in the B K-edge XAS spectra of Zr and Hf complexes provides the most direct evidence of covalent M–H–B bonding. This feature, assigned as B 1s → M–H–B π* transition based on TDDFT calculations, appears due to covalent mixing between boron and the metal. The intensity of this pre-edge feature correlates with the degree of covalency in the bond [2]. Furthermore, the ¹¹B NMR chemical shifts and B–H vibrational frequencies show systematic variations that correlate with changes in M–B distances, providing additional evidence for the covalent character of these interactions.

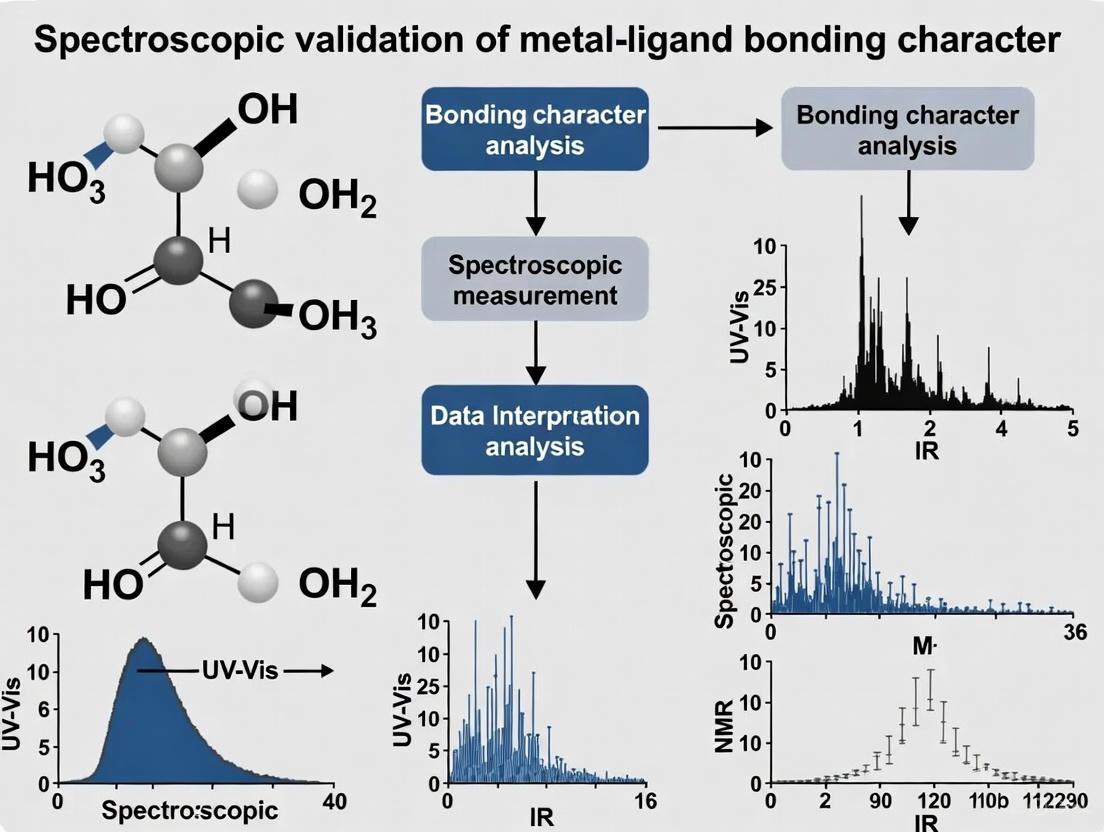

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for validating M–H–B bonding character:

Experimental Workflow for M–H–B Bond Analysis

The molecular orbital diagram for a generic M–H–B 3c-2e bond illustrates the electronic transitions probed by spectroscopic methods:

Molecular Orbital Scheme for M–H–B Bond

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of M–H–B bonding requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key research solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for M–H–B Bonding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Research | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Anhydrous ZrCl₄, HfCl₄; high purity (>99.9%) | Source of metal centers for borohydride complex synthesis | Strict exclusion of moisture and oxygen; glovebox or Schlenk techniques |

| Borane Reagents | LiBH₄, NaBH₄, or substituted boranes (e.g., PhBH₃) | Source of BH₄⁻ or substituted borohydride ligands | Moisture-sensitive; may release hydrogen gas upon hydrolysis |

| Deuterated Solvents | Deuterated THF, benzene, toluene; molecular sieves for drying | NMR spectroscopy for structural characterization and kinetics | Store under inert atmosphere; degas before use for sensitive compounds |

| XAS Sample Supports | Aluminum foil, gold-coated slides; high vacuum compatibility | Sample mounting for boron K-edge XAS measurements | Conductively coated for charge compensation in ultra-high vacuum |

| Computational Software | Gaussian, ORCA, ADF with TDDFT capabilities | Theoretical calculation of electronic structure and spectral properties | High-performance computing resources for large metal complexes |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | Soft X-ray beamline with high energy resolution | Experimental access to boron K-edge (190-220 eV) for XAS | Competitive proposal process; typically requires collaboration |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Bonding Models

The validation of covalent character in M–H–B bonding has significant implications for understanding the behavior of metal borohydride complexes compared to those with traditional bonding models:

Table 4: M–H–B Bonding vs. Alternative Metal-Ligand Interactions

| Parameter | M–H–B 3c-2e Bond | Classical Ionic Model | Dative Bonding | Conventional Covalent Bond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Character | Electron-deficient; delocalized | Primarily electrostatic | Coordinate covalent; localized | Electron-precise; localized |

| Spectroscopic Signature | B K-edge pre-edge feature (B 1s → M–H–B π*) | No metal-boron orbital mixing in spectra | LMCT/MLCT transitions in UV-Vis | Well-defined σ and π bonds in spectroscopy |

| Bond Length | Intermediate between terminal M–H and B–H | Longer M-B distances | Varies with donor-acceptor strength | Short, determined by atomic radii |

| Bond Energy | Moderate (between ionic and covalent) | Variable (high for small ions) | Moderate to weak | Strong (depends on bond order) |

| Effect on Reactivity | Enhanced reactivity at both M and B centers | Often dissociative pathways | Ligand substitution reactions | Directed reactivity at functional groups |

The covalent character of M–H–B bonds revealed through spectroscopic studies explains the unique reactivity patterns observed in metal borohydride complexes. Unlike purely ionic models that would predict dissociative behavior, the covalent mixing enables cooperative reactivity where both metal and boron centers participate in chemical transformations. This has profound implications for applications in catalysis, hydrogen storage, and materials science where metal borohydrides offer unique advantages over traditional complexes.

The direct spectroscopic validation of covalent three-center, two-electron M–H–B bonding represents a significant advancement in inorganic and organometallic chemistry. The integration of boron K-edge XAS with complementary techniques like NMR, vibrational spectroscopy, and theoretical calculations provides a powerful toolkit for quantifying bonding character in these complex systems. The experimental protocols outlined in this guide establish standardized methodologies for researchers investigating similar electron-deficient bonding motifs.

The confirmation of significant covalent character in M–H–B bonds challenges simplistic ionic or dative bonding models and provides a more nuanced understanding of structure-property relationships in metal borohydride complexes. These insights enable more rational design of catalysts, hydrogen storage materials, and other functional materials where fine control of metal-ligand bonding is essential for optimal performance. As spectroscopic techniques continue to advance, further refinement of these bonding models is anticipated, potentially revealing additional subtleties in the electronic structure and reactivity of three-center, two-electron bonded systems.

Electronic Structure Assessments in d- and f-Block Borohydride Complexes

Understanding the electronic structure of d- and f-block borohydride complexes is of fundamental importance in inorganic chemistry and materials science, with implications for catalyst design, nuclear fuel separation, and hydrogen storage technologies. [5] [6] These complexes feature unconventional three-center, two-electron (3c-2e) M–H–B bonds, where electron density is delocalized across metal, hydrogen, and boron atoms. [5] Traditional bonding models often fail to fully capture the covalent character of these interactions, necessitating advanced spectroscopic techniques for direct experimental validation. This guide compares the capabilities, experimental requirements, and applications of key spectroscopic methods used to probe metal-borohydride bonding, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate characterization strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Table 1: Technical comparison of spectroscopic methods for assessing metal-borohydride bonding.

| Technique | Physical Principle | Orbital Specificity | Covalency Sensitivity | Key Measurable | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B K-edge XAS | B 1s core electron excitation to unfilled MOs | Unoccupied orbitals with B np character | Direct via pre-edge intensity | Pre-edge energy & intensity | Ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁸ torr), non-volatile solids [5] |

| Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES) | Ionization from occupied molecular orbitals | Occupied MO energies | Indirect via orbital energy shifts | Ionization potentials, branching ratios | Vacuum compatibility [5] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Nuclear shielding via electron distribution | Metal-bound ligand nuclei | Paramagnetic, diamagnetic, spin-orbit shielding contributions | Chemical shift (δ), shielding constants (σ) | Isotopic enrichment (¹³C, ¹⁵N); air-sensitive handling [6] |

| IR Spectroscopy | Vibrational frequency shifts | Bond strength indicators | Indirect via bond weakening | C–H, B–H stretch redshifts | Gas-phase, matrix-isolated, or He-tagged complexes [7] |

Table 2: Performance characteristics for electronic structure analysis.

| Technique | Bonding Information Obtained | Element Applicability | Quantitative Capability | Complementary Calculations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B K-edge XAS | Direct evidence of B np and metal d/f orbital mixing | d-block (Zr, Hf); potentially f-block | Pre-edge area ∝ covalency | TDDFT for pre-edge assignment [5] |

| Photoelectron Spectroscopy | Orbital composition from ionization energies | d- and f-block | Semi-quantitative via branching ratios | DFT for orbital assignment [5] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | M–L bond covalency via spin-orbit shielding | f-elements (U, La); d-block | ΔSO metric correlates with f-orbital participation | Relativistic DFT for shielding analysis [6] |

| IR Spectroscopy | Ligand activation via bond weakening | d-block (Au, Cu, Ni clusters) | Frequency shifts correlate with π-backdonation | DFT for vibrational assignments [7] |

Experimental Methodologies

B K-edge X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy

Sample Preparation Protocol

- Synthetic Route: React MCl₄ (M = Zr, Hf) with 4 equivalents of Li(RBH₃) in pentane solvent. [5]

- Ligand Design: Employ trihydroborate ligands with large aryl substituents (R = phenyl, mesityl, 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl, anthryl) to suppress volatility. [5]

- Crystallization: Grow single crystals via cooling concentrated pentane solutions or vapor diffusion of toluene solutions with pentane. [5]

- Handling Considerations: Conduct all manipulations under inert atmosphere due to extreme air sensitivity and pyrophoric nature of native borohydrides. [5]

Data Collection Parameters

- Vacuum Requirements: Ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁸ torr) necessary due to low B K-edge energy (~188 eV). [5]

- Spectral Features: Identify pre-edge feature at ~192 eV assigned to B 1s → M–H–B π* transition via TDDFT calculations. [5]

- Reference Measurements: Collect background spectra from empty sample holder and boron-free analogs to confirm feature assignment. [5]

NMR Spectroscopy for Covalency Assessment

Experimental Setup

- Nuclei Probed: ¹³C, ¹⁵N, ⁷⁷Se, ¹²⁵Te nuclei in metal-bound ligands. [6]

- Key Parameters: Measure chemical shifts (δ) and derive nuclear shielding constants (σ). [6]

- Shielding Analysis: Deconvolute diamagnetic (σdia), paramagnetic (σpara), and spin-orbit (σ_SO) contributions. [6]

Data Interpretation Framework

- Covalency Metric: Utilize Δ_SO (chemical shift difference with/without spin-orbit effects) as primary covalency indicator. [6]

- Threshold Values: ΔSO >300 ppm indicates high covalency (e.g., [U(CH₂SiMe₃)₆] at 348 ppm); ΔSO <10 ppm suggests highly ionic character (e.g., [La(C₆Cl₅)₄]⁻ at 9 ppm). [6]

IR Spectroscopy of Metal-Ligand Interactions

Gas-Phase IR Photodissociation Spectroscopy

- Cluster Formation: Generate charged gold clusters (Auₙ⁺/⁻, n≤4) via pickup on superfluid helium nanodroplets. [7]

- Ligand Coordination: Introduce acetylene (C₂H₂) molecules to form Aun+/−(C₂H₂)m complexes. [7]

- Tagging Method: Use helium tagging to cool complexes and enable IR photodissociation spectroscopy. [7]

Spectral Analysis

- Spectral Range: Probe C–H stretching region (2850–3390 cm⁻¹). [7]

- Activation Indicator: Redshifts in C–H stretching frequencies relative to free acetylene (3288.7 cm⁻¹) signal π-backdonation and bond activation. [7]

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for borohydride complex studies.

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | ZrCl₄, HfCl₄, UCl₄, [U(CH₂SiMe₃)₆] | Provide metal centers for complex formation | High purity, strict anhydrous handling [5] [6] |

| Trihydroborate Salts | Li(PhBH₃), Li(MesBH₃), Li/K(BnBH₃) | Source of borohydride ligands with tunable sterics | Synthesized from boronic acid + LiAlH₄ [5] |

| Isotopically Enriched Compounds | ¹³C-labeled ligands, ¹⁵N-amides | Enhanced NMR sensitivity for covalency studies | Custom synthesis often required [6] |

| Synchrotron Facilities | B K-edge beamlines | High-flux soft X-ray source for XAS | Ultra-high vacuum compatibility essential [5] |

| Computational Software | TDDFT, relativistic DFT packages | Theoretical validation of experimental spectra | Predict spectral features, quantify orbital mixing [5] [6] |

The direct experimental assessment of metal-ligand covalency in d- and f-block borohydride complexes requires a multifaceted spectroscopic approach. B K-edge XAS has emerged as a particularly powerful technique for directly probing covalent mixing in 3c-2e M–H–B bonds, providing unambiguous evidence of orbital overlap between boron and metal centers. [5] NMR spectroscopy offers complementary insights into f-element covalency through analysis of spin-orbit contributions to nuclear shielding, with exceptional sensitivity to minor orbital interactions. [6] Photoelectron and IR spectroscopy provide additional windows into orbital energies and bond activation phenomena, respectively. [5] [7] The integration of these experimental methods with advanced computational analyses (TDDFT, relativistic DFT) creates a robust framework for validating metal-ligand bonding character, enabling researchers to move beyond simplistic bonding models and toward precisely engineered electronic structures for specific applications. As these techniques continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover new dimensions of metal-borohydride interactions, driving innovation in catalysis, separations science, and materials design.

The Role of Chirality and Geometry in Metal Complex Stability

In the design of metal-based drugs and catalysts, the stability of the metal complex is a paramount consideration, directly influencing its reactivity, function, and efficacy. Among the factors governing this stability, molecular chirality and coordination geometry play a decisive role. Chirality, the property of a molecule being non-superimposable on its mirror image, can dictate the three-dimensional structure a metal complex adopts. This, in turn, is intimately linked to the complex's electronic properties, thermodynamic stability, and kinetic lability. This guide objectively compares the stability of various chiral metal complexes, framing the analysis within the critical context of spectroscopic validation. The data and methodologies presented are essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to rationally design metal complexes with tailored stability profiles.

Experimental Approaches for Stability Assessment

The stability of metal complexes is not a singular property but can be evaluated through various experimental lenses. The following table summarizes the core experimental protocols used to quantify and compare stability, along with the specific insights each method provides.

Table 1: Key Experimental Methods for Assessing Metal Complex Stability

| Method | Experimental Protocol Summary | Measured Parameter | Stability Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA) | The sample is heated at a controlled rate (e.g., 10 °C/min) under an inert atmosphere, and its mass change is recorded as a function of temperature [8]. | Decomposition Onset Temperature | Thermal stability; resistance to thermal decomposition. |

| X-ray Crystallography | Single crystals of the complex are exposed to X-rays. The resulting diffraction pattern is solved to determine the electron density map, revealing atomic positions [9] [8]. | Metal-Ligand Bond Lengths & Angles | Geometric stability; preferred coordination geometry and stereochemistry. |

| Valence-to-Core X-ray Emission Spectroscopy (VtC XES) | A high-energy X-ray beam ejects a 1s electron from the metal. The resulting core hole is filled by a valence electron, and the emitted photon is measured to probe the ligand's molecular orbitals [10]. | Energies of ligand-based orbitals | Electronic structure and metal-ligand bond covalency. |

| High-Energy Resolution Fluorescence Detected XAS (HERFD-XAS) | The X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) is measured by monitoring the fluorescence decay at a high-resolution emission line, sharpening the spectral features [10]. | Pre-edge peak energy and intensity | Oxidation state and coordination geometry. |

Comparative Stability Data of Chiral Complexes

The interplay between the metal center, chiral ligand scaffold, and resultant geometry creates a complex stability landscape. The data below, compiled from recent studies, provides a quantitative comparison.

Table 2: Stability Comparison of Chiral Metal Complexes

| Complex Formulation | Chiral Source / Geometry | Key Stability Data | Primary Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Ni(L)] vs. [Cu(L)] vs. [Co(L)] vs. [Pd(L)] [8] | cis-1,2-diaminocyclohexane / Square Planar | TGA Decomposition Onset: [Ni(L)] > H₂L ~ [Cu(L)] > [Co(L)] > [Pd(L)] [8] | [Ni(L)] exhibits the highest thermal stability, rationalized by strong M−O/N bonds and significant metal-to-ligand back-bonding [8]. |

| [Fe(Bn-CDPy3)Cl]⁺ Complexes [9] | trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane / Octahedral | Theoretical & Crystallographic Data: A single coordination geometry is strongly favored out of five possible isomers due to steric and electronic factors from the chiral ligand [9]. | The chiral ligand enforces a specific, stable geometry, controlling the asymmetric environment around the metal. |

| {FeNO}⁶ Photolysts (1 vs. 2) [10] | N/A / Octahedral | HERFD-XAS Pre-edge Area: Complex 2 has ~11% greater intensity than Complex 1, indicating higher Fe-NO covalency [10]. | Increased metal-ligand covalency (Complex 2) correlates with altered photolytic stability and product evolution (NO vs. HNO) [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The synthesis and characterization of chiral metal complexes require a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table details key materials used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chiral Metal Complex Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Research | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral Diamines (e.g., trans-/cis-1,2-diaminocyclohexane) | Serves as a privileged chiral scaffold in ligand design, transferring its asymmetry to the metal center [9] [8]. | Core building block for ligands like Bn-CDPy3 and salen ligands [9] [8]. |

| Salicylaldehyde Derivatives | Reacts with chiral diamines to form chiral Salen-type ligands, which strongly bind metals through their ONNO donor set [8]. | Synthesis of tetradentate Schiff base ligands for Cu, Ni, Pd, and Co complexes [8]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Provides a medium for NMR spectroscopy to analyze solution-state structure, purity, and chirality [9]. | Confirmation of ligand synthesis and assessment of enantio-purity via ¹H and ¹³C NMR [9]. |

| Metal Salts (e.g., FeCl₂, Co(OAc)₂, [Pd(PhCN)₂Cl₂]) | The metal ion source that coordinates with the chiral ligand to form the final complex [9] [8]. | Synthesis of [Fe(Bn-CDPy3)Cl]X and [M(L)] salen complexes [9] [8]. |

Spectroscopic Workflow for Stability Validation

The journey from synthesizing a chiral metal complex to validating its stability and bonding character involves a multi-technique spectroscopic workflow. This pathway integrates bulk thermal analysis with advanced methods that probe electronic and geometric structure.

Spectroscopic Evidence of Orbital Mixing and Electron Delocalization

Orbital mixing and electron delocalization represent fundamental concepts in chemical bonding that directly influence reactivity, stability, and physical properties across diverse molecular systems. The experimental validation of these electronic phenomena requires sophisticated spectroscopic techniques capable of probing subtle electron distribution patterns. Spectroscopic validation of metal-ligand bonding character has become increasingly crucial for advancing fields ranging from medicinal inorganic chemistry to energy storage materials science. This guide provides a comparative analysis of principal spectroscopic methods for detecting and quantifying orbital mixing and electron delocalization, presenting experimental protocols and data interpretation frameworks essential for researchers investigating electronic structures within metal-ligand systems, biological clusters, and advanced materials.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Spectroscopic Methods for Detecting Orbital Mixing and Electron Delocalization

| Technique | Physical Principle | Orbital Sensitivity | Key Delocalization Metrics | Sample Requirements | Applications Highlighted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paramagnetic NMR Spectroscopy | Detection of hyperfine shifts from unpaired electron density [11] | 3d/4f/5f orbitals | Fermi contact shifts, magnetic exchange coupling constants | 400-1100 µM protein solutions (for biological studies); Paramagnetic samples [11] | [Fe₂S₂]²⁺ clusters in ferredoxins; f-element complexes [11] [6] |

| Ligand K-edge XAS | Probing dipole-allowed 1s to valence transitions [12] | M–H–B π* orbitals | Pre-edge intensity and energy | Ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁸ torr); Solid-state or volatile complexes [12] | Zr/Hf borohydride M–H–B bonds [12] |

| IR Spectroscopy | Vibrational frequency shifts from bond order changes [13] | Molecular orbitals affecting bond strength | C–N/H stretches (e.g., 1566-1581 cm⁻¹ in metal complexes) [14] | Solid, liquid, or gas phases; Minimal sample prep | Tripodal ligand complexes; Soil organic carbon [14] [15] |

| DFT Calculations | Quantum mechanical modeling of electronic structure [16] [13] | All orbitals (computational) | Orbital energy variations, electron density maps [16] | Computational models requiring validation | Diallyl sulfide; Reaction pathways [16] [13] |

Performance Metrics and Limitations

Each spectroscopic method offers distinct advantages and limitations for investigating orbital mixing. Paramagnetic NMR provides exceptional sensitivity to electron delocalization in paramagnetic systems, with hyperfine shifts directly reporting on unpaired spin density at specific nuclei. For human ferredoxin 2, NMR measurements revealed an electron spin density transfer between cluster inorganic sulfide ions and aliphatic carbon atoms via C–H---S–Fe³⁺ interactions, with a magnetic exchange coupling constant of 386 cm⁻¹ between the two Fe³⁺ ions [11]. However, this technique requires specialized approaches for paramagnetic systems and may suffer from signal broadening.

Ligand K-edge XAS directly probes covalent bonding through pre-edge features resulting from orbital mixing. In zirconium and hafnium borohydride complexes, B K-edge XAS demonstrated significant covalent M–H–B bonding, with TDDFT calculations confirming B 1s → M–H–B π* transitions [12]. This method provides element-specific information but requires sophisticated instrumentation and theoretical support for interpretation.

IR spectroscopy offers accessibility and rapid characterization of bonding changes through vibrational frequency shifts. For tripodal N(piCy)₃ ligand complexes, CN stretches between 1566-1581 cm⁻¹ indicated hexadentate metal binding, while tetradentate coordination shifted stretches above 1600 cm⁻¹ [14]. Modern AI-driven IR analysis has significantly improved structure elucidation capabilities, achieving 63.79% Top-1 accuracy for molecular identification [17].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Paramagnetic NMR for [Fe₂S₂]²⁺ Clusters

Sample Preparation: Human ferredoxin 2 (residues 69-186) with an N-terminal 6xHis-tag was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and purified via standard protocols. The NMR sample contained 400-1100 µM protein in 30 mM HEPES buffer (150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) with 10% D₂O for lock signal [11].

One-Dimensional NMR Acquisition:

- ¹H NMR: Single 90° pulse with presaturation water suppression; Acquisition time: 23 ms; Recycle delay: 107 ms; Spectral width: 300 ppm; Transients: 128K [11]

- ¹³C NMR: Pulse-acquire or superWEFT-like sequences; Acquisition time: 69 ms; Recycle delay: 63 ms; Spectral width: 200 ppm; Transients: 8-131K depending on sequence [11]

- ¹⁵N NMR: Inversion recovery pulse sequence; Acquisition time: 557 ms; Inversion delay: 300 ms; Spectral width: 120 ppm; Transients: 361K [11]

Data Interpretation: Hyperfine shifts are analyzed with DFT calculations to map electron delocalization pathways and quantify magnetic coupling constants [11].

Boron K-edge XAS for M–H–B Bonding

Sample Preparation: A series of [Zr(RBH₃)₄] and [Hf(RBH₃)₄] complexes with substituents (R = benzyl, phenyl, mesityl, 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl, anthryl) were synthesized to attenuate volatility. Samples were characterized by ¹H/¹¹B NMR, IR spectroscopy, and single-crystal XRD prior to XAS analysis [12].

XAS Data Collection:

- Conducted under ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁸ torr) at the B K-edge

- Measured pre-edge feature intensity and energy

- Compared experimental results with TDDFT calculations for assignment [12]

Data Analysis: Pre-edge features assigned to B 1s → M–H–B π* transitions provide direct evidence of covalent orbital mixing. The intensity correlates with the degree of metal-boron covalency [12].

IR Spectroscopy with AI Interpretation

Traditional IR Analysis:

- Samples analyzed as solids, liquids, or in solution

- Characteristic stretches identified (e.g., C–N stretches at 1566-1581 cm⁻¹ for metal complexes) [14]

- Hydrofluoric acid pretreatment (10% HF, room temperature) recommended for mineral-rich samples to enhance carbohydrate (∼1,030 cm⁻¹) and aliphatic (∼2,850/2,920 cm⁻¹) band detection [15]

AI-Enhanced Structure Elucidation:

- Data Representation: IR spectra segmented into patches (optimal size: 75 data points) for Transformer-based analysis [17]

- Model Architecture: Patch-based Transformer with post-layer normalization, learned positional embeddings, and Gated Linear Units (GLUs) [17]

- Training: Pretraining on simulated spectra (∼1.4 million samples) followed by fine-tuning on experimental NIST database spectra [17]

- Data Augmentation: Horizontal shifting, Gaussian smoothing, SMILES augmentation, and pseudo-experimental spectra generation improve model robustness [17]

Signaling Pathways and Theoretical Frameworks

Electron Delocalization Pathway in [Fe₂S₂]²⁺ Clusters

Pathway Analysis: The electron delocalization pathway in [Fe₂S₂]²⁺ clusters involves antiferromagnetically coupled Fe³⁺ ions connected through inorganic sulfide bridges. NMR studies demonstrate spin density transfer from sulfide ions to aliphatic carbon atoms via C–H---S–Fe³⁺ interactions, creating extended delocalization networks beyond the immediate metal coordination sphere [11].

Theoretical Framework: Connecting Electron and Nuclear Motions

Theoretical Integration: The reactive-orbital energy theory (ROET) identifies molecular orbitals with the largest energy changes during reactions. These orbitals generate electrostatic Hellmann-Feynman forces on nuclei according to the equation:

[ \bf{F}_{\it{A}}^{\rm{elec}} \simeq Z_A \sum\limits_i^{n_{\rm{elec}}} \int d\bf{r} \phi_i^*(\bf{r}) \frac{\bf{r} - \bf{R}_A}{|\bf{r} - \bf{R}_A|^3} \phi_i(\bf{r}) ]

where ( \phi_i ) represents the i-th spin orbital wavefunction [16]. These forces create grooves on potential energy surfaces, directly linking electron delocalization to nuclear motion along reaction coordinates.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Orbital Mixing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specification | Research Function | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopically-Labeled Proteins | ¹⁵N, ¹³C labeling | Enables multinuclear NMR studies of biomolecules | Mapping electron delocalization in ferredoxin [Fe₂S₂] clusters [11] |

| Tripodal Ligand Systems | N(piCy)₃ and derivatives | Supports diverse metal coordination geometries | Comparative studies of early transition metal complexes [14] |

| f-Element Precursors | AnCl₃(THF)₃, Ln(N(TMS)₂)₃ | Forms covalent metal-ligand bonds | Quantifying 4f/5f orbital covalency via NMR [6] |

| Borohydride Reagents | RBH₃ (R = organic substituents) | Forms 3-center, 2-electron M–H–B bonds | Direct measurement of covalent bonding via B K-edge XAS [12] |

| Computational Software | DFT with LC functionals | Accurate orbital energy calculations | Reactive orbital identification and force analysis [16] |

The spectroscopic validation of orbital mixing and electron delocalization requires complementary approaches tailored to specific chemical systems. Paramagnetic NMR excels for biological metal clusters, ligand K-edge XAS provides direct covalent bonding evidence, and AI-enhanced IR enables rapid structural characterization. The integration of these experimental methods with theoretical frameworks like ROET offers a comprehensive strategy for elucidating electronic structure phenomena. As spectroscopic technologies advance with AI integration and higher sensitivity detectors, researchers will gain unprecedented ability to visualize and quantify electron delocalization across diverse chemical and biological systems, enabling rational design of catalysts, materials, and therapeutic agents with tailored electronic properties.

Advanced Spectroscopic Methods for Metal-Ligand Characterization

Ligand K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) stands as a powerful experimental technique for the direct quantification of metal-ligand bond covalency in transition metal complexes. This method utilizes synchrotron-generated light to excite ligand 1s electrons to higher energy levels, providing a direct probe of orbital mixing between metal and ligand atoms [5] [18]. The fundamental principle underlying this technique involves electric dipole-allowed transitions from ligand 1s orbitals to molecular orbitals containing both ligand np and metal d-character [19]. When a ligand is bound to an open-shell metal ion, the resulting pre-edge features in the XAS spectrum provide quantitative information about the covalent character of specific metal-ligand bonds [20].

The intensity of these pre-edge transitions directly correlates with the amount of ligand character in the metal d orbitals, thereby serving as a spectroscopic ruler for bond covalency [19]. This quantitative relationship has been successfully established for various ligand atoms including chlorine, sulfur, phosphorus, and more recently, boron [21] [19] [20]. Unlike other spectroscopic methods that infer covalency indirectly, ligand K-edge XAS provides a direct experimental measurement, making it particularly valuable for validating computational models and understanding electronic structure-property relationships in coordination chemistry [19].

Table: Development of Ligand K-edge XAS for Different Elements

| Ligand Element | K-edge Energy Range (eV) | Type of Metal-Ligand Bonds Studied | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorine (Cl) | ~2820 | Cu-Cl, Zn-Cl | Fundamental methodology development |

| Sulfur (S) | ~2470 | Cu-S, Fe-S, Ni-S | Blue copper proteins, iron-sulfur clusters |

| Boron (B) | ~188 | M–H–B, Ni-B, Zr-B, Hf-B | Borohydride complexes, dicarbollides |

Theoretical Framework and Fundamental Principles

The theoretical foundation of ligand K-edge XAS rests on the electric dipole selection rule that governs 1s → np transitions (Δl = ±1) [5]. For a transition metal complex with a ligand atom bound to a metal center, the core 1s electron localized on the ligand can be excited to unfilled or partially filled molecular orbitals that contain both metal d-character and ligand np character [19]. The intensity of this transition is governed by the extent of ligand np character mixing in the wavefunction of the acceptor orbitals [5].

For a molecular system with one hole in the 3d orbital (such as a d⁹ Cu(II) complex), the ground state wavefunction (ψ*) can be described as:

ψ* = (1-β²-α²)¹ᐟ²ϕ(Metal(3d)) - βϕ(Ligand(3p)) - αϕ(Non-Ligand)

where β² represents the amount of ligand 3p character and (1-β²-α²) corresponds to the metal 3d character in the wavefunction [20]. The observed pre-edge intensity I is then related to the theoretical intensity of a pure electric dipole-allowed 1s→3p transition I[S(1s→3p)] by:

I[S(1s→ψ*)] = β²I[S(1s→3p)]

This relationship provides the mathematical foundation for quantifying metal-ligand covalency from experimental pre-edge intensities [20]. The methodology has been extended beyond the initial sulfur and chlorine K-edge studies to include other ligand atoms, with boron representing one of the most recent and challenging additions due to its low K-edge energy (~188 eV) and experimental constraints [21] [5].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

B K-edge XAS Measurement Protocols

The collection of B K-edge XAS data presents unique experimental challenges due to the low energy of the boron K-edge (approximately 188 eV) [5]. At this energy, any gas or protective material would effectively block the X-ray beam, necessitating measurements under ultra-high vacuum conditions (<10⁻⁸ torr) on exposed samples [5] [18]. This requirement precludes the study of highly volatile compounds, which has historically limited the application of B K-edge XAS to molecular transition metal complexes [5].

For recent studies on zirconium and hafnium borohydrides, researchers developed specialized protocols to overcome these limitations [5] [18]. Samples were prepared as homogeneous powders and pressed into indium foil or thinly dispersed on Mylar tape to minimize self-absorption effects [21]. Data collection typically occurs over a narrow energy window (184-210 eV) in fluorescence mode using a microchannel plate detector [21]. To mitigate radiation damage, which manifests as gradual changes in spectral features during repeated scans, samples are moved between measurements to expose fresh areas [21].

The B K-edge XAS experiments for borohydride complexes were conducted at synchrotron facilities, particularly the Canadian Light Source (CLS) on the Variable Line Spacing Plane Grating Monochromator (VLS-PGM) beamline [21]. For complementary studies on nickel dicarbollide complexes, similar instrumentation was employed, with careful attention to potential photodecomposition that can occur over the course of data collection [21].

Sample Preparation and Handling

Specialized sample preparation is crucial for successful B K-edge XAS measurements. For borohydride complexes, air sensitivity presents a significant challenge, as compounds like [Zr(BH₄)₄] and [Hf(BH₄)₄] are pyrophoric and enflame in air [5]. To address volatility constraints while maintaining solubility for crystallization, researchers designed [Zr(RBH₃)₄] and [Hf(RBH₃)₄] complexes with bulky organic substituents (R = benzyl, phenyl, mesityl, 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl, and anthryl) that attenuate volatility through enhanced intermolecular forces [5] [18].

These complexes were synthesized by reacting MCl₄ (M = Zr, Hf) with four equivalents of the corresponding Li(RBH₃) salt in pentane [5] [18]. Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by cooling concentrated pentane solutions or through vapor diffusion of concentrated toluene solutions with pentane [5]. The resulting complexes exhibited no appreciable volatility when sublimation was attempted at temperatures up to 100°C at 10⁻² torr, making them suitable for ultra-high vacuum studies [5].

B K-edge XAS Experimental Workflow

Comparative Analysis of Boron K-edge XAS Applications

Three-Center, Two-Electron Bonding in Zr and Hf Borohydrides

The recent application of B K-edge XAS to zirconium and hafnium borohydride complexes represents a significant advancement in understanding three-center, two-electron (3c-2e) M–H–B bonding [12] [5]. These [M(RBH₃)₄] complexes feature inner coordination spheres comprised exclusively of M–H–B bonds, with remarkable properties including high volatility and solubility in non-polar solvents [5]. The B K-edge XAS spectra of these complexes exhibit a distinct pre-edge feature assigned as B 1s → M–H–B π* based on time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations [12].

This pre-edge feature appears due to covalent mixing between boron and the metal centers, providing direct experimental evidence for covalent 3c-2e M–H–B bonding in borohydride complexes using boron as a spectroscopic reporter [12] [5]. The experimental data revealed metal-dependent differences, with the average M−B distances measured by single-crystal X-ray diffraction being 2.325(5) Å for [Zr(PhBH₃)₄] and 2.295(7) Å for [Hf(PhBH₃)₄] [18]. These structural correlations with spectroscopic features provide compelling evidence for the utility of B K-edge XAS in probing subtle electronic structure differences in metal borohydride complexes [18].

Direct Metal-Boron Bonding in Nickel Dicarbollide Complexes

In contrast to the bridged M–H–B bonding in borohydrides, B K-edge XAS has also been applied to nickel dicarbollide complexes featuring direct Ni-B bonds [21]. The study of Ni(C₂B₉H₁₁)₂ revealed a pronounced pre-edge feature in the B K-edge spectrum that was absent in the nickel-free ligand control compound (HNMe₃)(C₂B₉H₁₂) [21]. This pre-edge feature was determined to consist of at least two absorptions centered at 188.1 and 189.2 eV, with the lower-energy component assigned to B 1s → Ni–B σ* transitions [21].

Density functional theory calculations provided crucial support for this assignment, revealing that the LUMO and LUMO+1 orbitals contained significant Ni–B σ* character with 49% B 2p and 28% Ni 3d character for the LUMO, and 47% B 2p and 25% Ni 3d character for the LUMO+1 [21]. The excellent agreement between experimental spectra and TDDFT calculations demonstrated the capability of B K-edge XAS to detect and quantify covalent metal-boron bonding even in complexes with direct metal-boron interactions [21].

Table: Comparative Analysis of B K-edge XAS Applications

| Parameter | Zr/Hf Borohydride Complexes | Ni Dicarbollide Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Bonding Type | 3c-2e M–H–B bridging | Direct Ni-B bonding |

| Pre-edge Energy | Not specified | 188.1 eV and 189.2 eV |

| Assignment | B 1s → M–H–B π* | B 1s → Ni–B σ* |

| Metal-Boron Distance | 2.295-2.325 Å | Not specified |

| Covalency Evidence | Pre-edge feature from covalent mixing | Pre-edge feature from Ni-B σ* transitions |

| Experimental Challenges | Air sensitivity, volatility | Photodecomposition during measurement |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful application of ligand K-edge XAS, particularly at the boron K-edge, requires specialized materials and reagents that address the unique experimental challenges. The following table summarizes key solutions developed for recent groundbreaking studies in this field:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for B K-edge XAS Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Specific Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-volatile Borohydride Complexes | Enables UHV studies by suppressing volatility | [Zr(RBH₃)₄] and [Hf(RBH₃)₄] with R = Ph, Mes, Trip, Anth | Bulky substituents attenuate volatility through intermolecular forces |

| Trihydroborate Salts | Ligand precursors for complex synthesis | Li(PhBH₃), Li(MesBH₃), Li(TripBH₃), Li/K(BnBH₃) | Air-sensitive, synthesized by boronic acid reduction with LiAlH₄ |

| Synchrotron Beamline Components | Enable B K-edge measurements | VLS-PGM beamline at Canadian Light Source | Ultra-high vacuum capability, fluorescence detection, 184-210 eV energy range |

| Sample Supports | Minimize self-absorption and degradation | Indium foil, Mylar tape | Compatible with UHV, minimal interference with low-energy X-rays |

| Computational Methods | Spectral interpretation and assignment | TDDFT calculations with B3LYP-d3 functional | Validate experimental assignments, provide theoretical covalency metrics |

Comparative Performance with Alternative Techniques

Ligand K-edge XAS provides distinct advantages and complementarity to other spectroscopic methods for assessing metal-ligand covalency. The table below compares its capabilities with alternative approaches:

Table: Comparison of Techniques for Assessing Metal-Ligand Covalency

| Technique | Information Provided | Limitations | Applicability to M–B Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand K-edge XAS | Direct measure of ligand np character in unoccupied MOs | Limited to accessible edges, UHV for low Z elements | Direct evidence for Zr/Hf–B and Ni–B covalency |

| Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES) | Orbital energies and compositions through ionization | Large final state effects, indirect covalency assessment | Previously provided orbital-specific information for borohydrides |

| EPR/ENDOR Spectroscopy | Spin density distribution from hyperfine couplings | Requires paramagnetic centers, complex interpretation | Limited to paramagnetic borohydride complexes |

| UV-vis-NIR Spectroscopy | Charge transfer energies and intensities | Indirect probe, requires theoretical modeling | Used for electronic structure assessment in borohydrides |

| Inner-Shell EELS (ISEELS) | Core excitation spectra similar to XAS | Requires volatile samples, limited to gas phase | Previously used for carboranes and dicarbollides |

Technique Capability Comparison for Covalency Assessment

Ligand K-edge XAS has established itself as a powerful, direct method for quantifying metal-ligand covalency across diverse chemical systems. The recent extension to boron K-edge studies represents a significant methodological advancement, enabling direct experimental assessment of metal-boron bonding in both bridged M–H–B systems and complexes with direct M–B bonds [12] [21] [5]. The combination of specialized sample design, advanced synchrotron instrumentation, and theoretical modeling using TDDFT has overcome previous limitations associated with boron's low K-edge energy and the volatility of traditional borohydride complexes [5] [18].

The quantitative data obtained from these studies provide crucial experimental benchmarks for computational chemistry and deepen our understanding of bonding in transition metal complexes. As the methodology continues to develop, applications to other challenging ligand edges and more complex molecular systems will further expand our ability to directly probe chemical bonding. The integration of ligand K-edge XAS with complementary spectroscopic techniques promises a more comprehensive approach to elucidating electronic structure and its relationship to reactivity and function in inorganic and bioinorganic chemistry.

B K-edge XAS as a Spectroscopic Reporter for M–H–B Bonds

The precise characterization of metal-ligand bonding represents a fundamental challenge in inorganic chemistry and catalysis research, particularly for unconventional bonding motifs that underpin unique reactivity profiles. Among these, the three-center, two-electron (3c-2e) M–H–B bond found in metal borohydride complexes has long intrigued researchers due to its significant electron delocalization across all three atoms [12]. Traditional spectroscopic techniques have struggled to directly quantify the degree of orbital mixing between metal and boron centers, creating critical knowledge gaps in our understanding of these covalent interactions [18]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates B K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) against alternative spectroscopic methods for characterizing M–H–B bonds, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their analytical strategies.

The validation of metal-ligand bond covalency is especially crucial for fields ranging from catalyst design to nuclear fuel separation science [6]. While numerous techniques have been employed to probe electronic structure, direct experimental assessment of metal-boron orbital mixing has remained elusive until recent advancements in spectroscopic methodology. This guide examines the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application contexts for leading spectroscopic approaches to M–H–B bond analysis.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanism

B K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy operates by exciting core 1s electrons localized on boron atoms using synchrotron-generated X-rays [18]. When applied to metal borohydride complexes, the technique provides direct evidence of covalent three-center, two-electron M–H–B bonding by probing unfilled or partially filled molecular orbitals containing both boron and metal character [12]. The orbital selection rule permits 1s → np transitions (Δl = ±1), making transitions to molecular orbitals with metal d- or f-character detectable provided sufficient ligand np character is present in the wavefunction [18].

The key spectroscopic feature in B K-edge XAS is the pre-edge transition, which appears due to covalent mixing between boron and the metal [12]. The intensity of this pre-edge feature is governed by the extent of ligand np character mixing in the associated orbitals' wavefunctions, providing a quantitative handle for assessing variations in metal-ligand covalency [18]. For Zr and Hf borohydride complexes, this pre-edge feature has been assigned as B 1s → M–H–B π* based on comparison to time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations [12].

Experimental Requirements and Constraints

Implementing B K-edge XAS presents specific technical challenges that researchers must address:

- Ultra-High Vacuum Conditions: Measurements require environments below 10⁻⁸ torr due to the low energy of the B K-edge (approximately 188 eV), which would otherwise be absorbed by atmospheric gases or protective materials [12] [18].

- Sample Volatility Management: Traditional metal borohydride complexes like [Zr(BH₄)₄] and [Hf(BH₄)₄] exhibit high volatility (vapor pressure of 15 torr at 25°C), making them unsuitable for UHV studies [18]. This necessitates synthesis of modified complexes with attenuated volatility through strategic substituent selection.

- Synchrotron Radiation Source: The technique requires access to synchrotron facilities capable of generating tunable X-rays in the appropriate energy range.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Direct Comparison of Performance Metrics

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Spectroscopic Methods for M–H–B Bond Analysis

| Technique | Bonding Information Obtained | Detection Sensitivity | Sample Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B K-edge XAS | Direct evidence of covalent M–H–B bonding; Orbital mixing quantification [12] | High for boron-metal covalency [18] | UHV conditions; Non-volatile samples [18] | Limited to solids; Requires synchrotron access |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Metal-ligand covalency via chemical shift analysis [6] | Moderate for light elements [6] | Solution or solid-state; Limited air sensitivity | Indirect measure; Interpretation complexity |

| IR Spectroscopy | B–H vibrational stretching modes [12] | Moderate for functional groups | Various sample forms | Indirect structural information |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | M−B distances; Structural parameters [12] | High for heavy atoms | Single crystals preferred | Limited electronic structure data |

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Table 2: Experimental Results from Zr and Hf Borohydride Complexes Using B K-edge XAS

| Complex | Average M−B Distance (Å) | Pre-edge Feature Assignment | Key Spectral Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Zr(PhBH₃)₄] | 2.325(5) [18] | B 1s → M–H–B π* [12] | BH₃ chemical shifts correlate with M−B distances [12] |

| [Hf(PhBH₃)₄] | 2.295(7) [18] | B 1s → M–H–B π* [12] | B–H vibrational modes correlate with M−B distances [12] |

| [Cp₂Zr(PhBH₃)₂] | 2.628(6) [18] | Not measured | Demonstrates distance variation with coordination mode |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

B K-edge XAS Experimental Workflow

Detailed Methodological Framework

Sample Preparation Protocol

The critical first step involves synthesizing non-volatile borohydride complexes suitable for UHV studies [18]:

- Ligand Modification: Employ trihydroborate ligands with large substituents (benzyl, phenyl, mesityl, 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl, anthryl) to attenuate volatility through enhanced intermolecular forces [18].

- Complex Synthesis: React MCl₄ (M = Zr, Hf) with four equivalents of the corresponding Li(RBH₃) salt in pentane solvent [18].

- Crystallization: Grow single crystals via cooling concentrated pentane solutions or vapor diffusion of concentrated toluene solutions with pentane [18].

- Validation: Characterize products using ¹H and ¹¹B NMR spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction to confirm structure and assess M−B distances [12].

Data Collection Parameters

- Vacuum Conditions: Maintain ultra-high vacuum below 10⁻⁸ torr throughout data collection [12] [18].

- Energy Range: Focus on the boron K-edge region around 188 eV with particular attention to pre-edge features [18].

- Reference Measurements: Collect background spectra and reference compounds as applicable.

Computational Validation

- Theoretical Methods: Perform time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations to simulate spectra and assign pre-edge features [12] [18].

- Spectral Assignment: Confirm B 1s → M–H–B π* transitions through theoretical comparison [12].

- Covalency Quantification: Correlate experimental pre-edge intensities with calculated orbital mixing parameters [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for B K-edge XAS Studies of M–H–B Bonds

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Li(RBH₃) Salts | Starting materials for borohydride complex synthesis [18] | R = phenyl, mesityl, 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl to reduce volatility [18] |

| ZrCl₄ / HfCl₄ | Metal precursors for complex formation [18] | Reaction with Li(RBH₃) to form [M(RBH₃)₄] complexes [18] |

| Synchrotron Radiation Source | Provides tunable X-rays for B K-edge excitation [18] | Enables measurement of B 1s excitation spectra [12] |

| UHV Chamber System | Maintains required vacuum conditions [12] | Prevents absorption of low-energy X-rays by gases [18] |

| TDDFT Computational Methods | Theoretical validation and spectral assignment [12] | Assigns pre-edge features to B 1s → M–H–B π* transitions [18] |

Interpretation Framework and Data Analysis

Spectral Interpretation Pathway

Correlation with Complementary Techniques

Effective characterization of M–H–B bonds requires integrating B K-edge XAS with supporting methodologies:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Provides structural parameters including M−B distances, which correlate with BH₃ chemical shifts and B–H vibrational stretching modes observed in spectroscopic studies [12].

- NMR Spectroscopy: ¹¹B and ¹H NMR reveal metal- and ligand-dependent differences in BH₃ chemical shifts that complement XAS covalency assessments [12].

- IR Spectroscopy: B–H vibrational stretching modes offer additional evidence of bonding interactions that align with XAS findings [12].

- Computational Methods: TDDFT calculations are essential for accurate spectral assignment and quantitative bonding analysis [12].

B K-edge XAS represents a significant advancement in the spectroscopic toolkit for directly quantifying covalent character in M–H–B bonds, overcoming longstanding limitations of indirect assessment methods. The technique's unique capability to probe boron-metal orbital mixing through pre-edge intensity analysis provides researchers with a more direct approach to electronic structure determination in metal borohydride systems.

For research teams considering implementation, B K-edge XAS offers maximum value when addressing fundamental questions about covalent bonding in 3c-2e M–H–B systems, particularly when complemented by structural and computational methods. The technical requirements—especially synchrotron access and specialized sample preparation—mean the technique is best deployed for targeted bonding studies rather than routine characterization. As spectroscopic capabilities continue advancing with improved detection methods and brighter light sources, B K-edge XAS is poised to expand our understanding of metal-ligand bonding across diverse chemical systems with implications for catalyst design, materials science, and energy applications.

NMR Spectroscopy for Structural Elucidation and Quantification

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stands as one of the most powerful analytical techniques available to researchers for structural elucidation and quantification at the molecular level. This non-destructive method provides unparalleled insights into the structure, dynamics, and chemical environment of atoms within molecules. The continuous advancement of NMR technology, particularly with the development of higher-field instruments and specialized probes, has significantly expanded its applications across chemistry, materials science, and drug development.

In the specific context of spectroscopic validation of metal-ligand bonding character, NMR offers unique capabilities for quantifying interaction strengths and understanding binding dynamics. The technique's ability to probe molecular structures in both solution and solid states makes it particularly valuable for investigating coordination complexes that are often insoluble or unstable in solution. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative performance of different NMR methodologies is crucial for selecting the appropriate experimental approach for their specific metal-ligand systems.

Fundamental Principles and Technological Advancements

Core Principles of NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei when placed in a strong external magnetic field. The fundamental principle involves the absorption and emission of electromagnetic radiation at specific resonance frequencies that are characteristic of the magnetic nucleus and its chemical environment. This resonance frequency, known as the Larmor frequency, provides information about the molecular structure surrounding the nucleus. When nuclei are subjected to radiofrequency pulses, they undergo excitation and subsequent relaxation, emitting signals that contain detailed information about molecular structure, dynamics, and interactions [22].

The chemical shift, measured in parts per million (ppm), serves as the primary indicator of a nucleus's electronic environment, while scalar coupling constants reveal connectivity patterns between atoms. For quantitative analysis, signal intensity is directly proportional to the number of nuclei contributing to that signal, enabling precise concentration measurements without the need for external standards.

Recent Technological Advancements

The performance of NMR spectroscopy has been dramatically enhanced through technological innovations in magnet design, probe technology, and experimental methodologies:

High-Field NMR Systems: The spectral resolution of NMR increases proportionally with the magnetic field strength (B₀). Higher magnetic fields increase the separation between different resonant frequencies of nuclei, leading to better resolution of closely spaced signals. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is proportional to the magnetic field strength raised to the power of three-halves, making high-field instruments significantly more sensitive [23]. Recent installations of 1.1 GHz and 1.2 GHz NMR spectrometers at facilities like The Ohio State University represent the cutting edge of this technology [24].

Cryogenically Cooled Probes: The widespread adoption of probeheads equipped with coils and preamplifiers that are cryogenically cooled by cold helium or nitrogen has significantly reduced system noise, thereby improving SNR in detection. These cryoprobes enable the efficient characterization of numerous chemical systems at natural abundance, without the need for time-consuming and costly isotope labeling processes [23].

Advanced Magnetic Resonance Techniques: Researchers have recently demonstrated that extended measurement techniques are possible beyond classical resonance frequencies. By repeatedly changing the strength of the magnetic field abruptly, scientists have discovered resonance frequencies far from the Larmor frequency, opening new possibilities for materials research and imaging [22].

Networked NMR Infrastructure: Initiatives like the Network for Advanced NMR (NAN) are working to democratize access to high-field NMR instrumentation by making resources visible and accessible to researchers across the United States. This network approach also creates the first at-scale repository of experimental NMR data, promoting reproducibility and enabling new modes of discovery [24].

Comparative Performance of NMR Methodologies

Quantitative Analysis of Metal-Ligand Interactions

NMR spectroscopy provides several distinct approaches for quantifying metal-ligand interactions, each with specific strengths and limitations. The table below summarizes the primary NMR techniques used for binding constant determination:

Table 1: Comparison of NMR Techniques for Binding Affinity Measurement

| Technique | Affinity Range (KD) | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP) | > 1 μM | Hit identification, binding site mapping | Simple implementation, provides structural information | Limited for tight binders, affected by multiple factors |

| 19F Transverse Relaxation (T2) | 1 nM - 100 μM | High-throughput screening, fragment-based drug discovery | High sensitivity, low background | Requires fluorinated ligands |

| Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) | > 100 nM | Epitope mapping, weak binders | Detects weak interactions, provides structural information | Semi-quantitative, signal dependent on experimental conditions |

| Water-LOGSY | > 100 nM | Detection of weak binders, screening | Enhanced sensitivity for weak binders | Affected by solvent conditions |

| Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP) | < 1 nM - 1 mM | Tight binding systems, membrane proteins | Dramatic sensitivity enhancement | Requires specialized equipment, radical additives |

| Long-Lived States (LLS) | < 1 nM - 1 mM | Ultra-slow exchange processes | Access to slow exchange regimes | Complex pulse sequences, limited applications |

| Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE) | < 1 nM - 1 mM | Weak interactions, transient complexes | Long-range distance information | Requires paramagnetic centers |

For strong ligands with dissociation constants (KD) below 1 μM, NMR faces limitations in direct binding constant determination due to slow exchange conditions on the NMR timescale. Competition experiments, where a tight binder is titrated with a reference weak binder, provide the most general solution to this challenge. These methods extend the measurable affinity range down to picomolar concentrations when properly designed [25].

³¹P NMR Probe Methodology for Lewis Acidity Quantification

The use of ³¹P NMR probes has emerged as a particularly powerful approach for quantifying Lewis acidity in metal-ligand catalyst complexes. This methodology employs phosphorous-containing molecular probes that coordinate to Lewis acidic centers, with the resulting changes in ³¹P chemical shifts providing a quantitative measure of Lewis acidity. The table below compares different ³¹P NMR probes used in these studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ³¹P NMR Probes for Lewis Acidity Assessment

| Probe Type | Binding Mode | Chemical Shift Range (δ, ppm) | Sensitivity to Lewis Acidity | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monodentate Probes | Single coordination site | Narrow (5-15 ppm) | Moderate | Basic screening, rapid assessment |

| Bidentate Probes | Two coordination sites | Wide (15-50 ppm) | High | Complex catalyst systems, asymmetric catalysis |

| New Bidentate Probes | Two coordination sites with varied electronics | Very wide (20-80 ppm) | Very high | Subtle electronic effects, counterion impact |

In a comprehensive study evaluating metal-ligand catalyst complexes, ³¹P NMR spectroscopy successfully quantified the effects of ligands, counterions, and additives on Lewis acidity. The researchers compared three different ³¹P NMR probes, including two new bidentate binding probes, based on different binding modes and the relative scale of their downfield shift upon binding to Lewis acid complexes. Bidentate probes demonstrated superior sensitivity in assessing catalyst complexes due to their importance in asymmetric catalysis [26] [27].

The binding studies were performed under catalytically relevant conditions, giving further applicability to synthesis. The quantified Lewis acidity values showed direct correlation with reaction yield at an early time point as an approximation for catalytic activity and efficiency. This approach also provided insight into activation modes and chelation behavior in two representative organic transformations [27].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Workflow for Metal-Ligand Binding Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for characterizing metal-ligand bonding using NMR spectroscopy:

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

³¹P NMR Probe Experiment for Lewis Acidity Quantification

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions of ³¹P NMR probe molecules (typically 10-50 mM in appropriate deuterated solvent)

- Prepare metal-ligand catalyst complexes at concentrations ranging from 0.1-5 mM

- For titration experiments, maintain constant probe concentration while varying catalyst concentration

- Use internal standards (e.g., TMS for ¹H NMR, 85% H₃PO₄ for ³¹P NMR) for chemical shift referencing

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- Temperature: Control precisely (±0.1°C) using instrument temperature unit

- ³¹P NMR frequency: Set to appropriate value for the field strength (e.g., 202.4 MHz for 500 MHz instrument)

- Pulse sequence: Use standard ¹H-decoupled ³¹P NMR with sufficient relaxation delay (typically 3-5 × T₁)

- Spectral width: 100-200 ppm to ensure complete coverage of potential chemical shifts

- Number of scans: Adjust based on concentration and sensitivity requirements (typically 16-128 scans)

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Apply appropriate window functions (exponential or Gaussian multiplication) to enhance SNR

- Perform phase correction and baseline correction

- Measure chemical shifts relative to reference standard

- Plot chemical shift changes as function of catalyst concentration

- Fit binding isotherms to appropriate models to extract binding constants [26] [27]

Competition Experiments for Tight Binding Systems

For strong ligands with KD < 1 μM, competition experiments provide the most reliable approach:

- Prepare a sample containing the protein/target and a reference weak binder with known affinity

- Record NMR spectrum (typically ¹H or ¹⁹F) to establish baseline signal for reference binder

- Titrate in the tight binding ligand of interest

- Monitor changes in signal intensity or chemical shift of reference binder

- Analyze data using appropriate competition binding equations to extract KD for tight binder [25]

Research Reagent Solutions for NMR Studies

The following table details essential reagents and materials for NMR studies of metal-ligand systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NMR Studies of Metal-Ligand Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆, D₂O) | Solvent for NMR experiments, field frequency lock | Purity, residual proton signals, hygroscopicity |

| Chemical Shift References (TMS, DSS, 85% H₃PO₄) | Chemical shift calibration, quantitative reference | Solubility, chemical inertness, resonance position |

| ³¹P NMR Probes (monodentate and bidentate) | Lewis acidity quantification, binding studies | Binding affinity range, coordination mode, solubility |

| Metal Salts and Complexes | Study of metal-ligand interactions | Oxidation state, stability, solubility, ligand exchange kinetics |

| Reference Ligands | Competition experiments, validation studies | Known binding constants, purity, solubility |

| Relaxation Agents (e.g., Gd³⁺ complexes) | T₁ relaxation measurements, paramagnetic studies | Concentration, stability, effect on protein function |

| Buffer Components | pH control, ionic strength adjustment | Deuteration, minimal signal interference, compatibility |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Techniques

While NMR provides exceptional insights into metal-ligand bonding character, it is essential to understand its performance relative to other spectroscopic and analytical techniques:

Table 4: Comparison of NMR with Alternative Techniques for Metal-Ligand Studies

| Technique | Information Obtained | Sensitivity | Sample Requirements | Quantitative Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Atomic-level structure, dynamics, binding constants | Moderate to high (μM-mM) | Relatively high concentration | Excellent with proper experimental design |

| X-ray Crystallography | High-resolution 3D structure | N/A | Single crystals required | Limited to solid state |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Binding constants, thermodynamics | High (nM-μM) | Moderate concentration | Excellent for binding constants and thermodynamics |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Binding kinetics, affinity | Very high (pM-nM) | Immobilization required | Excellent for kinetics, good for affinity |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Binding constants, conformational changes | Very high (pM-nM) | Low concentration | Good with proper controls |

| Mass Spectrometry | Molecular weight, stoichiometry | High | Low concentration | Semi-quantitative without standards |

NMR's unique strength lies in its ability to provide atomic-level structural information simultaneously with quantitative binding data under physiologically relevant conditions. While it may lack the extreme sensitivity of some alternative techniques, its versatility and information content make it indispensable for comprehensive metal-ligand characterization.

The field of NMR spectroscopy continues to evolve with significant advancements in magnet technology, probe design, and experimental methodologies. The ongoing development of higher-field instruments, such as the 1.2 GHz spectrometer recently installed at The Ohio State University, promises even greater resolution and sensitivity for structural elucidation and quantification [24]. These technological improvements will further enhance NMR's capabilities for studying metal-ligand interactions, particularly for challenging systems with weak binding or complex dynamics.

The discovery of new forms of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy that operate outside classical resonance frequencies opens exciting possibilities for materials research and imaging [22]. Similarly, the development of more sophisticated cryoprobes and the implementation of hyperpolarization techniques like DNP are dramatically expanding the accessible range of biological and chemical systems that can be studied by NMR [25] [23].