Spectrophotometric Colorimetry vs. UV-Vis Spectrophotometry: A Practical Guide for Photocatalytic Assessment

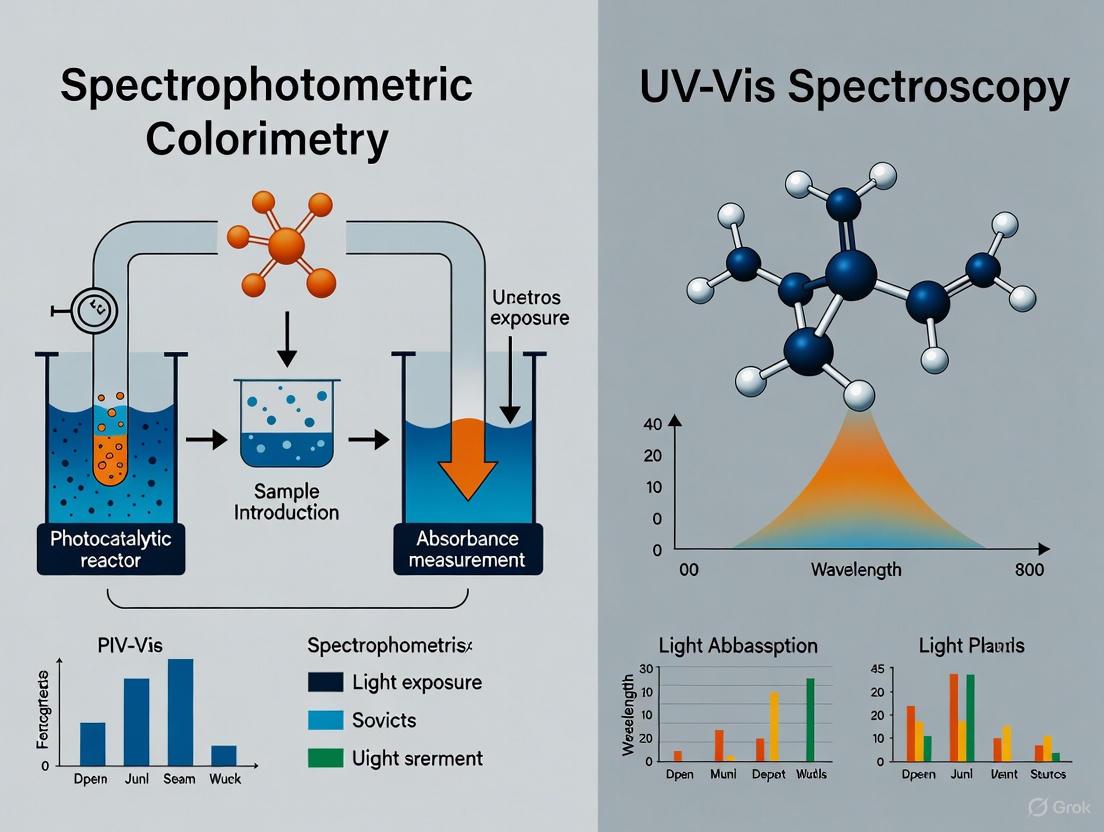

This article provides a comparative analysis of spectrophotometric colorimetry and UV-Vis spectrophotometry for evaluating photocatalytic efficiency, a critical process in environmental remediation and advanced oxidation technologies.

Spectrophotometric Colorimetry vs. UV-Vis Spectrophotometry: A Practical Guide for Photocatalytic Assessment

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of spectrophotometric colorimetry and UV-Vis spectrophotometry for evaluating photocatalytic efficiency, a critical process in environmental remediation and advanced oxidation technologies. Tailored for researchers and scientists, the content explores the fundamental principles, distinct methodological approaches, and specific applications of each technique. It offers practical guidance for troubleshooting common issues and optimizing protocols for different sample types, including complex substrates. A direct, evidence-based comparison equips professionals with the knowledge to select the most appropriate, reliable, and cost-effective method for their specific photocatalytic research and development projects.

Understanding the Core Principles: How Colorimetry and UV-Vis Spectrophotometry Work

In photocatalytic assessment research, accurately quantifying changes in color or concentration is fundamental to evaluating material performance. This guide objectively compares two principal instrumental techniques for this purpose: spectrophotometric colorimetry and UV-Vis spectrophotometry. Despite the apparent similarity in their names, these techniques are founded on different measurement principles, yielding data of varying complexity and suitability for specific research applications.

Spectrophotometric colorimetry, often referred to simply as colorimetry, is designed for psychophysical sample analysis, meaning its measurements correlate directly with human color perception [1]. It provides straightforward tristimulus values (e.g., L, a, b) that describe the color appearance of a sample under a fixed illuminant. In contrast, UV-Vis spectrophotometry is a tool for physical sample analysis [1]. It performs full-spectrum measurement, capturing a sample's reflectance or transmittance properties across a wide range of wavelengths, typically from ultraviolet (UV) to visible (Vis) light, from 190 nm to 1100 nm depending on the instrument. This generates a rich spectral fingerprint that can be used for precise quantification, identification, and complex color analysis beyond the capabilities of the human eye. For researchers developing new photocatalysts for applications like organic dye degradation or pharmaceutical pollutant removal, the choice between these techniques can significantly impact the depth, accuracy, and reliability of experimental conclusions.

Technical Comparison: Principles, Capabilities, and Data Output

The core difference between these instruments lies in their optical design and the fundamental nature of the data they produce. A colorimeter is a tristimulus color measurement device. It uses a simple light source and a set of three filtered sensors (red, green, and blue) that simulate the response of the human eye [1] [2]. The result is direct readouts of tristimulus values, which are excellent for determining if two colors look the same to an observer under a specific light.

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer, however, uses a more complex system. It employs a monochromator (comprising a prism, grating, or interference filter) to separate a broadband light source into individual wavelengths [1]. This allows the instrument to scan the sample with light of a specific, narrow bandwidth and measure how much is absorbed or transmitted across the entire spectral range. The primary data output is a spectrum—a plot of absorbance (or transmittance) versus wavelength [1] [3]. This full-spectrum data is the source of its superior analytical power.

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications and Capabilities

| Feature | Spectrophotometric Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Principle | Tristimulus; measures with 3 broad filters (RGB) [1] [2] | Full spectrum; measures with a monochromator [1] |

| Primary Data Output | Tristimulus values (e.g., X, Y, Z or L, a, b*) [1] | Absorbance/Transmittance spectrum (intensity vs. wavelength) [1] |

| Typical Application Scope | Color difference, fastness, and strength [1] | Quantitative concentration analysis, reaction kinetics, identification of compounds [3] |

| Light Source & Observer | Fixed illuminant; typically 2-degree standard observer [1] | Adjustable illuminant settings; typically 10-degree standard observer [1] |

| Analysis of Metamerism | Not possible [1] | Possible due to full spectral data [1] |

| Key Advantage | Speed, portability, cost-effectiveness for routine color QC [1] | High precision, versatility, and comprehensive data for R&D [1] |

Application in Photocatalytic Assessment: Experimental Evidence

The choice of technique is critically illustrated in the field of photocatalysis, where researchers quantify the degradation of organic dyes or pharmaceuticals to benchmark material performance.

Real-Time Monitoring with UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

Advanced photocatalytic research often requires observing reaction kinetics on a sub-second timescale. A 2023 study demonstrated this using a real-time UV-Vis spectroscopic setup to monitor the photocatalytic degradation of Methylene Blue (MB) by TiO₂ nanoparticles [3]. The experimental setup used a broadband Xenon Arc lamp, and a CMOS camera captured all spectral information simultaneously, enabling the acquisition of spectra every 20 milliseconds [3]. This method allowed researchers to plot the evolution of the MB absorption spectrum in real-time, clearly showing the degradation process and even revealing different mechanisms based on the quantity of TiO₂ used [3]. This level of temporal and spectral resolution is impossible for a standard colorimeter, which can only provide tristimulus values at discrete time points.

Quantitative Analysis of Complex Mixtures

UV-Vis spectrophotometry is also indispensable for specific quantitative analyses where colorimetry would be inadequate. A 2024 study on characterizing hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs) compared various UV-Vis spectroscopy-based methods for quantifying hemoglobin [4]. The research highlighted the sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) Hb method as a preferred choice due to its specificity, ease of use, and safety [4]. The study emphasized that selecting a quantification method based on full-spectrum UV-Vis data is crucial for accurate characterization, as it allows researchers to analyze the entire absorbance spectrum for potential interferences from other carrier components before selecting the quantification algorithm [4]. This specificity and analytical rigor are hallmarks of spectrophotometric analysis.

Performance in Pigment Prediction

A comparative study on predicting natural pigments in agricultural products found that a color spectrophotometer (a type of reflectance spectrophotometer) provided the best accuracy for predicting Total Carotenoid Content (TCC), while Vis/NIR spectroscopy was superior for predicting Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) [5]. This demonstrates that even within the category of spectrophotometric instruments, the optimal choice depends on the specific analyte and its spectral characteristics.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies from Cited Research

Protocol 1: Real-Time Photocatalytic Degradation Monitoring

This protocol is adapted from the study observing MB degradation with TiO₂ nanoparticles [3].

- Objective: To monitor the photocatalytic degradation of an organic dye (Methylene Blue) in real-time using a custom UV-Vis spectroscopic setup.

- Materials:

- Photocatalyst: TiO₂ nanoparticles [3].

- Target Pollutant: Methylene Blue (MB) solution [3].

- Light Source: 300 W Xenon Arc lamp (or other suitable UV-Vis source) [3].

- Spectroscopic Setup: Broadband light source, grating (1200 grooves/mm), and CMOS camera for simultaneous spectral capture [3].

- Magnetic stirrer for continuous mixing.

- Method:

- Prepare an aqueous solution of MB at a known initial concentration (e.g., ~10 µM).

- Disperse a precise quantity of TiO₂ photocatalyst into the MB solution (e.g., 1 g/L).

- Place the mixture in a reaction vessel under continuous stirring.

- In the dark, allow the system to equilibrate for 30 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

- Initiate irradiation with the Xenon Arc lamp.

- Simultaneously, begin acquiring absorbance spectra at a high frequency (e.g., every 20 ms) using the CMOS camera.

- Continue data acquisition until the reaction is complete (e.g., 1-2 hours).

- Data Analysis: The degradation is tracked by observing the decrease in the characteristic absorption peaks of MB (~664 nm and ~614 nm) over time. The kinetics can be modeled by plotting the normalized absorbance (C/C₀) versus time.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Photocatalytic Activity for Pharmaceutical Degradation

This protocol is based on research investigating novel photocatalysts for degrading ibuprofen [6].

- Objective: To evaluate the full-spectrum-responsive photocatalytic activity of a material (e.g., YMnO₃-based nanoparticles) for the degradation of a pharmaceutical pollutant.

- Materials:

- Photocatalyst: e.g., YMO or YMO-SO powder [6].

- Target Pollutant: Ibuprofen solution [6].

- Light Source: 300 W Xenon lamp with filters to isolate UV, Vis, and NIR regions [6].

- Analytical Instrument: Standard UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., UV1901 UV-Vis spectrophotometer) [6].

- pH meter and chemicals for adjustment (e.g., NaOH, H₂SO₄).

- Method:

- Prepare an ibuprofen solution at a specified concentration (e.g., 75 mg/L) [6].

- Adjust the solution to the desired pH (e.g., pH 7) [6].

- Add a known amount of photocatalyst (e.g., 1 g/L) to the solution [6].

- Stir in the dark for 30 minutes to reach adsorption equilibrium.

- Turn on the light source and begin irradiation. At fixed time intervals (e.g., every 10 minutes), withdraw aliquots of the reaction solution.

- Centrifuge the aliquots to remove the photocatalyst particles.

- Analyze the concentration of the clear supernatant using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer by measuring the absorbance at the characteristic peak of ibuprofen.

- Data Analysis: The degradation percentage (D%) is calculated as (C₀ - Cₜ)/C₀ × 100%, where C₀ and Cₜ are the initial concentration and concentration at time t, respectively.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Assessment Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Target Pollutants | Model compounds to assess photocatalytic efficiency. | Methylene Blue (dye) [3], Ibuprofen (pharmaceutical) [6], Crystal Violet (dye) [7]. |

| Semiconductor Photocatalysts | Active materials that generate charge carriers under light to degrade pollutants. | TiO₂ nanoparticles [3], YMnO₃ (YMO) and its derivatives [6], Gd₂Zr₂O₇ pyrochlore nanoparticles [7]. |

| Chemical Scavengers | Used in trapping experiments to identify the primary active species in the photocatalytic mechanism. | Disodium EDTA (for holes, h⁺), 2-Propanol (for hydroxyl radicals, •OH), 1,4-Benzoquinone (for superoxide radicals, •O₂⁻) [6]. |

| Broadband Light Source | Simulates solar radiation or provides specific light regions (UV, Vis, NIR) to excite the photocatalyst. | 300 W Xenon Arc/Xenon lamp [3] [6]. |

| Buffer Solutions & pH Adjusters | Control the pH of the reaction environment, which can critically influence reaction pathways and degradation rates. | Use of acids (e.g., H₂SO₄) or bases (e.g., NaOH) to set specific pH values [6]. |

Selecting between spectrophotometric colorimetry and UV-Vis spectrophotometry hinges on the research question's complexity and the required data granularity.

Use a Spectrophotometric Colorimeter when: The application is strictly limited to quality control of color [1] [2]. The primary need is to quickly measure color difference (ΔE) between a standard and a sample, or to monitor color fastness and strength in a production or inspection environment [1]. Its advantages are speed, portability, and lower cost [1].

Use a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer when: The research demands physical sample analysis and comprehensive data [1]. This is essential for quantifying concentration via Beer-Lambert law, studying reaction kinetics in real-time, identifying unknown compounds from their spectral signature, detecting metamerism, or performing color formulation [1] [3]. It is the instrument of choice for R&D, precise analysis, and whenever the mechanism of a photoreaction is under investigation [1].

In conclusion, for rigorous photocatalytic assessment research that goes beyond simple color comparison, UV-Vis spectrophotometry is the unequivocally superior and necessary tool. Its ability to provide full spectral data enables researchers to not only quantify degradation but also to uncover intermediate species, understand reaction pathways, and reliably benchmark the performance of next-generation photocatalytic materials.

The objective quantification of color is a critical process in numerous scientific fields, including pharmaceutical development and photocatalytic assessment. Instrumental color measurement moves beyond the limits of human perception and vocabulary, allowing researchers to capture color information as objective data. This creates a common language of color essential for scientific communication and quality control across industries [8] [1]. The two principal advanced color measurement instrument types are colorimeters and spectrophotometers, both of which use sophisticated technologies to accurately quantify color, but through fundamentally different operating principles.

Colorimeters perform psychophysical sample analysis by mimicking human eye-brain perception, meaning their measurements correlate directly to how we see color [8] [1]. In contrast, spectrophotometers are designed for physical sample analysis via full spectrum color measurement, providing wavelength-by-wavelength spectral analysis of a sample's reflectance, absorbance, or transmittance properties [8]. This fundamental distinction in approach—tristimulus values versus full-spectrum analysis—defines their respective capabilities, applications, and suitability for different research environments, particularly in sophisticated applications like photocatalytic assessment where understanding material properties under light exposure is paramount.

Core Operating Principles and Methodologies

The Tristimulus Method: Colorimeter Operation

A colorimeter is designed to perform a type of psychophysical sample analysis by mimicking human eye-brain perception, which means its measurements correlate to human perception. In essence, it is engineered to see color the way we do [8] [1]. Its results are direct readings of tristimulus values, which identify a color with characters representing different dimensions of its visual appearance. These values typically use standardized systems like CIE XYZ or CIELab (L, a, b*) developed by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) [8] [9].

The colorimeter's operation is often based on the Beer-Lambert law, which establishes that the concentration of a solute in a solution is proportional to its absorbance of light [8] [1]. The instrument starts with a simple light source. With the help of a lens and tristimulus absorption filters, the beam of light becomes a single, focused wavelength which then passes through the sample solution. A photocell detector on the opposite side identifies how much of the wavelength was absorbed. This detector connects to a processor and digital display that provides a readable output of the results [8].

The components of a colorimeter are specifically configured for this tristimulus approach:

- Illuminant: Represents a specific light source (e.g., daylight or incandescent) to project consistent brightness onto the object. In a colorimeter, the illuminant is fixed [8].

- Observer: The standard observer offers a specific field of view for analyzing colors, typically a 2-Degree Standard Observer suitable for color evaluation and quality control [8].

- Tristimulus Absorption Filter: This filter isolates specific wavelengths to be applied to the sample, typically corresponding to red, green, and blue color channels [8] [10].

Colorimeter Measurement Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process of tristimulus color measurement, from light source through to tristimulus value output.

Full-Spectrum Analysis: Spectrophotometer Operation

A spectrophotometer operates on fundamentally different principles than a colorimeter, designed for comprehensive physical sample analysis via full spectrum color measurement [8]. By providing wavelength-by-wavelength spectral analysis of a sample's reflectance, absorbance, or transmittance properties, it produces precise data beyond what is observable by the human eye [8]. While spectrophotometers can calculate psychophysical colorimetric information if desired, their primary strength lies in capturing the complete spectral characteristics of a sample [8].

The components of a spectrophotometer reflect its advanced capabilities:

- Illuminant: The illuminant in a spectrophotometer is versatile, allowing researchers to use standard and fluorescent illuminants representing various types of light conditions [8].

- Observer: The observer of a spectrophotometer is typically larger, at about 10 degrees, which CIE recommends as the most appropriate tool for industrial color applications [8].

- Dispersion Element: Instead of simple absorption filters, a spectrophotometer uses a prism, diffraction grating, or interference filter to isolate specific wavelengths, which allows it to systematically scan across the spectral range [8] [10].

The operational process involves an illuminant projecting a light source onto an object and through a prism, grating, or filter. This optical system isolates specific wavelength bands to sequentially hit the sample. A sensor then detects the light that isn't absorbed by the item and passes the data to a processor or computer equipped with specialized software. This system can detect spectral reflectance, transmittance, and absorbance characteristics across the entire measured spectrum [8] [1].

Spectrophotometer Full-Spectrum Analysis: This diagram shows the comprehensive spectral measurement process, highlighting the wavelength scanning capability across the full spectrum.

Comparative Technical Specifications

The differences between these two instrumental approaches become clear when examining their technical specifications and measurement capabilities side by side. The following table summarizes the key distinguishing characteristics:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Colorimeters and Spectrophotometers

| Feature | Colorimeter | Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Type | Tristimulus (RGB/XYZ) values [10] | Full spectral data (wavelength-by-wavelength) [10] |

| Data Output | Direct tristimulus values (Lab*, XYZ) [8] | Complete spectral curves, plus calculated tristimulus values [8] |

| Light Separation | Tristimulus absorption filters [8] | Prism, grating, or interference filter [8] |

| Observer Angle | Typically 2-degree standard observer [8] | Typically 10-degree standard observer [8] |

| Illuminant Options | Fixed [8] | Multiple, adjustable (D65, A, F, etc.) [8] |

| Metamerism Detection | Not capable [8] [1] | Capable [8] [1] |

| Color Formulation | Not supported [8] | Supported [8] |

Beyond these fundamental technical differences, the instruments vary significantly in their operational characteristics and suitability for different research environments:

Table 2: Performance and Application Comparison

| Characteristic | Colorimeter | Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Moderate [10] | High [10] |

| Measurement Speed | Fast [8] | Varies (generally slower) [8] |

| Portability | Typically high [8] [10] | Varies (portable and benchtop options) [8] |

| Complexity | Simple operation [10] | More complex setup and operation [10] |

| Cost | Lower [8] [10] | Higher [8] [10] |

| Primary Applications | Basic QC, color comparison, concentration measurement [10] | R&D, color formulation, full-spectrum analysis [8] [10] |

| Environmental Robustness | Suitable for production environments [8] | More sensitive, better for laboratory settings [8] |

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Methodology for Photocatalytic Assessment

In photocatalytic assessment research, both colorimeters and spectrophotometers provide valuable data, though of different types and depths. For tristimulus measurement of photocatalytic color changes, the experimental protocol typically involves:

Sample Preparation: Prepare photocatalytic material samples (e.g., TiO₂ coatings, ZnO nanoparticles) on standardized substrates. Ensure consistent surface characteristics and thickness across samples.

Initial Measurement: Using a colorimeter, measure the baseline L, a, and b* values of the untreated samples. Calibrate the instrument according to manufacturer specifications using provided white and black calibration tiles.

Contaminant Application: Apply a standardized amount of organic contaminant (e.g., methylene blue, rhodamine B) uniformly across the sample surface.

Photocatalytic Exposure: Expose samples to UV or visible light source under controlled conditions (specific wavelength, intensity, and duration).

Post-Exposure Measurement: Re-measure the L, a, and b* values using the same colorimeter settings and geometry.

Data Analysis: Calculate color difference (ΔE) using the CIELAB color difference equation: ΔE = [(ΔL)² + (Δa)² + (Δb*)²]^0.5. Correlate the degree of color change with photocatalytic efficiency.

For full-spectrum analysis of photocatalytic processes, the methodology is more comprehensive:

Instrument Calibration: Perform full wavelength calibration of the spectrophotometer using certified standards, verifying accuracy across the UV-Vis spectrum (typically 200-800 nm).

Baseline Spectral Capture: Collect full reflectance or absorbance spectra of the pristine photocatalytic material before contaminant application.

Contaminant Characterization: Measure the spectral characteristics of the contaminant solution alone to establish its spectral signature.

Time-Series Measurements: After contaminant application and during light exposure, collect spectral data at predetermined time intervals (e.g., every 5-15 minutes).

Spectral Deconvolution: Analyze spectral changes using multivariate analysis to identify specific chemical transformations and intermediate species.

Kinetic Modeling: Use the full spectral data to calculate degradation rates, quantum yields, and reaction kinetics based on specific wavelength absorbance changes rather than overall color shift.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Color Assessment

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Photocatalytic Materials (TiO₂, ZnO, WO₃, g-C₃N₄) | Primary catalysts for light-induced reactions | Different materials respond to different light wavelengths (UV vs. visible light active) [11] |

| Organic Dye Contaminants (Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B) | Model compounds for assessing photocatalytic efficiency | Provide measurable color changes and characteristic spectral signatures [11] |

| Standardized Substrates (Glass slides, quartz plates, reflective tiles) | Consistent surfaces for catalyst deposition | Quartz required for UV light transmission in certain experimental setups |

| CIE Standard Illuminants (D65 for daylight, A for incandescent) | Reference light sources for color measurement | Essential for metamerism assessment and standardized color evaluation [8] |

| Calibration Standards (White and black calibration tiles) | Instrument calibration for accurate measurements | Required before each measurement session to ensure data reliability [9] |

| UV-Vis Light Sources (Xenon lamps, LED arrays) | Activation of photocatalytic processes | Wavelength and intensity must be controlled and documented |

| Spectrophotometer Cells (Quartz, glass cuvettes) | Containers for liquid sample analysis | Quartz necessary for UV range measurements |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The fundamental difference in data output between these two methodologies directly influences analytical capabilities in photocatalytic research. The following comparison illustrates how the same photocatalytic process might be represented through these different measurement approaches:

Table 4: Comparative Data Output from Photocatalytic Degradation Analysis

| Analysis Parameter | Tristimulus Colorimeter Data | Full-Spectrum Spectrophotometer Data |

|---|---|---|

| Color Change Quantification | Single ΔE value representing total color difference | Multiple spectral peaks showing specific chromophore degradation |

| Time Resolution | Overall color change at endpoint or limited intervals | Continuous spectral evolution throughout reaction timeline |

| Sensitivity to Intermediates | Limited to visible color changes; may miss intermediates | Can detect transient intermediates with distinct spectral signatures |

| Metamerism Assessment | Not possible | Can identify when color matches under one illuminant but not another |

| Concentration Correlation | Indirect through overall color change | Direct through Beer-Lambert law at specific wavelengths |

| Kinetic Information | Overall degradation rate from color change | Multiple simultaneous reaction rates for different chromophores |

The tristimulus approach provides a simplified, human-vision-correlated assessment of photocatalytic activity, which may be sufficient for quality control applications where the endpoint is a visible color change. However, for mechanistic studies, reaction optimization, and comprehensive material characterization, the full-spectrum approach provides significantly deeper insights into the photocatalytic process, including identification of reaction intermediates, simultaneous monitoring of multiple contaminants, and understanding of degradation pathways.

The choice between tristimulus colorimetry and full-spectrum analysis fundamentally depends on the research objectives, required depth of information, and application context in photocatalytic assessment. Colorimeters, with their direct tristimulus measurement approach, offer speed, portability, and operational simplicity well-suited for rapid screening, quality control, and field applications where the primary interest is correlation with human visual perception [8] [10]. Their limitations in detecting metamerism, providing spectral data, or supporting color formulation must be considered within the research framework.

Spectrophotometers, through their comprehensive full-spectrum analysis, deliver detailed spectral information, superior accuracy, and versatile measurement capabilities essential for research and development, mechanistic studies, and precise color formulation [8] [10]. The ability to detect metamerism, measure colorant strength, and analyze a comprehensive range of sample types makes spectrophotometers particularly valuable for advanced photocatalytic research where understanding the fundamental processes beyond simple color change is required [8].

For photocatalytic assessment research specifically, the decision matrix should consider whether the study requires simple efficiency ranking (where colorimetry may suffice) versus detailed mechanistic understanding (requiring spectrophotometry). As research in this field advances toward more complex material systems and reaction environments, the comprehensive data provided by full-spectrum analysis becomes increasingly valuable, though the simplicity and speed of tristimulus methods retain their utility for specific applied applications.

In photocatalytic assessment research, the selection of appropriate analytical instrumentation is paramount for obtaining accurate and reproducible data. Colorimeters and UV-Visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometers represent two fundamental tools for material characterization, yet they differ significantly in their technological sophistication and application scope. Colorimetry is a technique designed to mimic human color perception, providing tristimulus values that are directly correlated with how we see color. In contrast, UV-Vis spectroscopy is a comprehensive analytical method that measures the absorption of light across the ultraviolet and visible electromagnetic spectrum, providing detailed information about electronic transitions in molecules [12] [13]. For researchers investigating photocatalytic materials, understanding the distinction between these instruments is crucial for proper experimental design, data interpretation, and ultimately, advancing research in sustainable energy and environmental remediation technologies.

The fundamental operating principle shared by both instruments is the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the path length (L) of the light through the sample: A = εcl, where ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient [14] [13] [15]. This relationship forms the quantitative foundation for both techniques, though the manner in which each instrument applies this law differs significantly in complexity and output.

Core Principles and Component-Level Comparison

Fundamental Operating Principles

Colorimeters operate on a relatively straightforward principle of using filtered light to make tristimulus measurements. They typically employ red, green, and blue (RGB) optical filters to separate broad wavelength bands, simulating the response of the human eye's photoreceptors [10] [16] [12]. This approach provides direct colorimetric information but lacks spectral detail. The measurement focuses primarily on quantifying color intensity, which can then be correlated with concentration through the Beer-Lambert law [14]. The simplicity of this approach makes colorimeters robust and easy to operate but limits their analytical capabilities primarily to concentration determination of colored compounds in the visible range.

UV-Vis spectrophotometers employ a significantly more sophisticated approach to spectral analysis. Instead of using fixed filters, these instruments utilize a monochromator (containing a diffraction grating or prism) to disperse polychromatic light from the source into its constituent wavelengths [17] [13]. This monochromator can be precisely adjusted to select narrow wavelength bands, allowing the instrument to scan across the UV and visible spectrum systematically. This capability enables the construction of complete absorption spectra, which provide a "molecular fingerprint" of the sample being analyzed [13] [15]. The detailed spectral information reveals not only concentration but also insights into molecular structure, energy gaps, and reaction kinetics—all critical parameters in photocatalytic research.

Component-by-Component Breakdown

The technological divergence between these instruments becomes evident when examining their core components side-by-side. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the key subsystems in each instrument:

Table 1: Detailed Comparison of Instrument Components

| Component | Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Single lamp: Tungsten or halogen lamp for visible range [14] [18] | Multiple lamps: Deuterium (UV) + Tungsten/Halogen (Vis) [17] [13] |

| Wavelength Selection | Fixed tristimulus filters (RGB) [10] [12] | Adjustable monochromator (grating or prism) [17] [13] |

| Spectral Range | Visible range only (~380-780 nm) [14] | UV + Visible ranges (~190-780 nm) [13] [15] |

| Sample Container | Glass or plastic cuvettes [14] [18] | Quartz cuvettes (for UV), glass/plastic (Vis only) [13] |

| Detector | Silicon photodiode or photocell [14] [18] | Photomultiplier tube (PMT) or advanced photodiodes (e.g., InGaAs for NIR) [17] [13] |

| Optical Configuration | Single beam design [14] | Single or double beam design [17] [13] |

| Data Output | Tristimulus values (X, Y, Z or L, a, b*) [10] [12] | Full spectrum (absorbance/transmittance vs. wavelength) [13] [1] |

System Architecture and Light Path

The fundamental differences in component technology directly influence the overall system architecture of each instrument. The following diagrams illustrate the typical optical paths and component arrangements for both systems.

Diagram 1: Colorimeter System Architecture

Diagram 2: UV-Vis Spectrophotometer System Architecture

Performance Comparison for Photocatalytic Assessment

Analytical Capabilities and Limitations

The different technological approaches of colorimeters and UV-Vis spectrophotometers lead to significant variations in their analytical capabilities, which directly impact their suitability for photocatalytic research applications.

Colorimeter Strengths and Limitations: Colorimeters excel in routine quantitative analysis of colored compounds within the visible spectrum. Their simplicity translates to advantages in portability, operational speed, and cost-effectiveness [10] [1]. For photocatalytic assessments, this makes them suitable for quick concentration checks of specific dyes (like methylene blue degradation monitoring) where high spectral resolution is unnecessary. However, colorimeters cannot detect metamerism (where colors match under one light source but not another) [10] [1], lack capability for color formulation [10], and provide no information about absorption events in the ultraviolet region [14]—a critical limitation since many photocatalytic reactions involve UV activation.

UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Strengths and Limitations: UV-Vis instruments provide comprehensive spectral data essential for fundamental research [1]. They can identify and quantify multiple compounds simultaneously based on their unique spectral fingerprints, monitor reaction kinetics at specific wavelengths, and determine crucial optical properties such as band gap energy of semiconductor photocatalysts [13] [15]. The ability to measure into the UV range is particularly important for characterizing wide-bandgap semiconductors like TiO₂. The primary trade-offs include higher cost, greater operational complexity, and typically larger instrument footprint [10] [1].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance differences between these instrument classes can be quantified through several key metrics, as summarized in the table below:

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Photocatalytic Applications

| Performance Parameter | Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Resolution | Low (broadband filters) [10] | High (adjustable, down to ≤1 nm SBW) [17] [15] |

| Photometric Accuracy | Moderate for color difference [1] | High (with linearity to 2-3 AU typically) [15] |

| Wavelength Accuracy | Fixed to filter characteristics [10] | High (typically ±0.5 nm) [15] |

| Stray Light | Not typically specified [14] | Critical specification (~3 AU for single monochromator) [15] |

| Measurement Speed | Very fast (seconds) [14] [1] | Slower (scanning required) but modern arrays are fast [13] |

| Metamerism Detection | No [10] [1] | Yes [10] [1] |

| Turbidity Measurement | Limited [14] | Yes (specialized models) [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Photocatalytic Assessment

Protocol 1: Dye Degradation Monitoring Using Colorimeter This protocol is optimized for rapid, routine assessment of photocatalytic activity using a colorimeter:

- Calibration: Prepare standard solutions of the target dye (e.g., methylene blue) at known concentrations. Using the colorimeter with the appropriate filter (e.g., blue filter for methylene blue), measure the absorbance of each standard and construct a calibration curve of concentration versus absorbance [14].

- Sample Preparation: Suspend the photocatalyst in the dye solution. Aliquot samples at predetermined time intervals during light irradiation and remove catalyst by centrifugation or filtration [14].

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance of each aliquot using the same colorimeter settings as calibration. Determine concentration from the calibration curve [14].

- Data Analysis: Plot concentration versus time to determine degradation kinetics. This method provides quantitative degradation efficiency but no information about intermediate products.

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Photocatalyst Characterization Using UV-Vis Spectrophotometer This advanced protocol provides complete optical characterization of both the photocatalyst and the reaction process:

- Band Gap Determination:

- Prepare a dilute suspension of the photocatalyst powder in a non-absorbing solvent or use an integrating sphere for solid samples.

- Acquire absorbance spectrum across the UV-Vis range (e.g., 250-800 nm) [13] [15].

- Transform the absorbance data to Tauc plot coordinates: (αhν)^(1/n) vs. hν, where α is absorption coefficient, hν is photon energy, and n depends on transition type (½ for direct, 2 for indirect band gaps) [15].

- Extrapolate the linear region of the Tauc plot to the energy axis to determine the optical band gap.

- Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism:

- Follow Protocol 1 steps but acquire full spectra (e.g., 300-800 nm) at each time point instead of single wavelength measurements [13].

- Use spectral deconvolution techniques to identify and quantify reaction intermediates based on their characteristic absorption peaks.

- Monitor isosbestic points to identify simple versus complex reaction pathways.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful photocatalytic assessment requires not only proper instrumentation but also appropriate selection of reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential research solutions for conducting these analyses:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Photocatalytic Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Dye Solutions (e.g., Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B) | Model pollutants for quantifying photocatalytic degradation efficiency [5] | Prepare fresh solutions; establish linear calibration curve within instrument's dynamic range (typically Abs < 1) [13] |

| Reference Catalysts (e.g., Degussa P25 TiO₂) | Benchmark materials for validating experimental protocols and instrument performance | Use consistent specific surface area and crystal phase composition for comparable results |

| Spectrophotometric Cuvettes | Sample containers with defined path length (typically 1 cm) [14] | Quartz for UV measurements, glass/plastic for visible-only; ensure proper cleaning to avoid contamination [13] |

| Solvent-Grade Water | Preparation of aqueous solutions and catalyst suspensions | Use high-purity water (18.2 MΩ·cm) to minimize interference from impurities [13] |

| Band Gap Reference Standards | Validation of UV-Vis instrument performance for Tauc plot analysis | Use materials with known band gaps (e.g., silicon, ZnO) to verify measurement accuracy |

| Neutral Density Filters | Checking photometric linearity of spectrophotometers [15] | Certified filters with known absorbance values at specific wavelengths |

The choice between a colorimeter and a UV-Vis spectrophotometer for photocatalytic assessment research depends fundamentally on the specific research objectives and required information depth.

Select a colorimeter when the application involves:

- High-throughput, routine quality control of photocatalytic materials

- Quantitative measurement of specific colored compounds where full spectral data is unnecessary

- Field measurements or environments where portability and robustness are prioritized

- Situations with budget constraints where basic concentration data is sufficient [10] [1]

Select a UV-Vis spectrophotometer when the research requires:

- Fundamental characterization of new photocatalyst materials (band gap determination, optical properties)

- Detection and quantification of reaction intermediates and complex degradation pathways

- Method development for novel photocatalytic processes

- Research requiring the highest possible accuracy and comprehensive spectral information [13] [1]

For complete photocatalytic characterization, many research laboratories ultimately utilize both instruments: colorimeters for rapid screening and quality control, and UV-Vis spectrophotometers for fundamental material characterization and method development. This dual approach maximizes both efficiency and analytical depth, advancing the development of more efficient photocatalytic systems for environmental and energy applications.

The Role of the Beer-Lambert Law in Quantitative Analysis

Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Beer-Lambert Law

- Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

- Instrumentation for Quantitative Analysis

- Experimental Protocols in Photocatalytic Assessment

- Comparative Analysis: Colorimetry vs. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

- Advanced Applications and Current Research

- Conclusion

The Beer-Lambert Law is a fundamental principle in analytical chemistry that describes the relationship between the absorption of light and the properties of a material through which the light is traveling [19] [20]. This law forms the cornerstone of quantitative analysis across numerous scientific disciplines, enabling researchers to determine the concentration of solutes in solution by measuring light absorbance [21]. In the specific context of photocatalytic assessment research, where understanding reaction kinetics and degradation rates is paramount, the Beer-Lambert Law provides the theoretical foundation for using spectroscopic techniques to monitor chemical changes [3] [22]. Its reliability and straightforward application make it an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require precise and accurate concentration measurements.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Beer-Lambert Law establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance (A) of a solution and the concentration (c) of the absorbing species, as well as the path length (L) of the light through the solution [19] [20]. The law is mathematically expressed as:

A = εlc

In this equation:

- A is the absorbance, a dimensionless quantity [19] [21].

- ε is the molar absorptivity (also known as the molar extinction coefficient), a constant specific to the substance and the wavelength of light, typically with units of M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [21] [23].

- l is the path length of the light through the solution, usually measured in centimeters (cm) [21].

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species, typically in moles per liter (M) [21].

Absorbance is defined through the concepts of incident light intensity ((I0)) and transmitted light intensity ((I)). Transmittance (T) is the ratio (I / I0), and absorbance is the negative logarithm of transmittance: A = -log₁₀(T) = -log₁₀(I / I₀) [19] [21]. This logarithmic relationship means that absorbance increases linearly with concentration, while transmittance decreases exponentially. The following table shows how absorbance and transmittance values correlate [19]:

| Absorbance | % Transmittance |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

The following diagram illustrates the core relationship described by the Beer-Lambert Law and the process of light absorption in a sample:

Instrumentation for Quantitative Analysis

The practical application of the Beer-Lambert Law relies on instruments designed to measure the transmission or absorption of light by a sample. The two primary types of instruments used are colorimeters and spectrophotometers, each with distinct capabilities.

Colorimeters are tristimulus color measurement devices that typically use filters to isolate broad bands of red, green, and blue light, simulating human eye response [2] [1]. They are based on the Beer-Lambert law and are designed for straightforward color comparison and quality control [1]. Their advantages include portability, speed, and relatively low cost, making them suitable for routine inspections on production lines [1]. However, they lack versatility and cannot provide full spectral data, making them unsuitable for complex analysis like identifying metamerism or formulating colors [2] [1].

Spectrophotometers are more sophisticated instruments that perform full-spectrum analysis [2] [1]. They use a monochromator (e.g., a prism or diffraction grating) to isolate individual wavelengths of light across a wide range, typically from ultraviolet (UV) to visible (VIS) and near-infrared [24] [1]. This allows them to measure the spectral reflectance, transmittance, or absorbance of a sample at each wavelength [2]. UV-Vis spectrophotometers, which analyze materials in the ultraviolet and visible wavelengths, are the instrument of choice for research, color formulation, and quantitative analysis where high precision and extensive data are required [3] [1]. Modern advancements include real-time UV/VIS spectroscopy, which uses a broadband light source and a CMOS camera to capture all spectral information simultaneously, enabling the observation of fast dynamic processes like photocatalytic degradation on a sub-second timescale [3].

The table below summarizes the key differences between these two instruments:

| Feature | Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Tristimulus color measurement (psychophysical analysis) [2] [1] | Full-spectrum color measurement (physical sample analysis) [2] [1] |

| Light Separation | Absorption filters (red, green, blue) [1] | Monochromator (prism or diffraction grating) [24] [1] |

| Output Data | Tristimulus values (e.g., L, a, b) [1] | Absorbance/Transmittance spectrum across wavelengths [3] [1] |

| Accuracy & Precision | Accurate for color difference measurements [2] | High precision and accuracy; suitable for research [2] [1] |

| Primary Applications | Quality control, inspection, simple color comparison [2] [1] | Research & development, quantitative analysis, complex color analysis, kinetic studies [3] [1] |

| Cost | Lower cost [2] | More expensive [2] |

Experimental Protocols in Photocatalytic Assessment

Photocatalytic assessment often involves monitoring the degradation of organic dyes, such as methylene blue (MB), using a catalyst like TiO₂ nanoparticles under light irradiation [3]. The following is a generalized experimental protocol for such a study using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

1. Principle and Objective The objective is to evaluate the efficiency of a photocatalyst by tracking the decrease in concentration of a model pollutant (e.g., methylene blue) over time. The Beer-Lambert Law is used to convert measured absorbance values at the dye's characteristic absorption peak (e.g., ~664 nm for MB) into concentration data [3].

2. Reagent and Instrumentation Setup Key research reagents and materials essential for this experiment include:

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Photocatalyst (e.g., TiO₂ nanoparticles) | The active material that degrades the dye under light [3]. |

| Model Pollutant (e.g., Methylene Blue solution) | The compound whose degradation is being monitored [3]. |

| Cuvette | A transparent container (typically with a 1 cm path length) to hold the sample during measurement [19]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | The instrument used to measure the absorbance spectrum of the solution at specific time intervals [3]. |

| Calibration Standards | A series of solutions with known concentrations of the dye, used to create a calibration curve [19] [21]. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow The following diagram outlines the key steps in a photocatalytic degradation experiment:

- Calibration Curve Creation: Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the dye (e.g., methylene blue). Measure the absorbance of each standard at the analytical wavelength (λ_max) using the UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Plot absorbance versus concentration to generate a calibration curve; the slope of this line is equal to εl, validating the linear range of the Beer-Lambert Law for the system [19] [21].

- Photocatalytic Reaction: In a reaction vessel, mix the photocatalyst with the dye solution. Begin irradiation with a light source of the appropriate wavelength (e.g., UV or visible light) to initiate the photocatalytic degradation [3].

- Real-Time Monitoring: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw samples from the reaction mixture. For real-time setups, a spectrophotometer with a fast CMOS camera can capture spectra continuously (e.g., every 20 ms) without manual sampling [3].

- Data Analysis: For each sample, measure the absorbance at the analytical wavelength. Use the calibration curve to convert these absorbance values into concentrations. Plot the concentration (or normalized concentration) as a function of time to visualize the degradation kinetics and determine the reaction rate [3].

Comparative Analysis: Colorimetry vs. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

When selecting an analytical technique for photocatalytic research, the choice between colorimetry and UV-Vis spectroscopy is critical and depends on the specific requirements of the study.

- Data Richness and Specificity: The most significant difference lies in the data output. A colorimeter provides a few tristimulus values, which are an average of the sample's interaction with broad red, green, and blue filters [2] [1]. This is sufficient for simple color matching but lacks detail. A UV-Vis spectrophotometer provides a full absorption spectrum, revealing fine details such as shifts in peak position, the appearance of isosbestic points, and the formation or disappearance of intermediate compounds with distinct spectral signatures [3] [1]. This is invaluable for understanding complex reaction mechanisms.

- Application in Photocatalysis Research: Colorimeters are generally inadequate for advanced photocatalytic assessment. As noted in research on methylene blue degradation, a real-time spectroscopic approach is necessary for a "comprehensive understanding of the mechanism" and enables "the detection of peak position shifts of new peaks on a sub-second timescale, which are not easily accessible using conventional UV/VIS spectroscopy" [3]. This level of detail is impossible to achieve with a colorimeter.

- Quantitative Accuracy and Limitations: Both techniques rely on the Beer-Lambert Law, which has known limitations. Deviations from linearity can occur at high concentrations (typically >10 mM) due to electrostatic interactions between molecules or changes in refractive index [20] [25]. Scattering of light by particulate matter (e.g., the photocatalyst itself) can also cause apparent deviations, a factor that must be accounted for in photocatalytic studies [20]. Spectrophotometers are better equipped to identify and correct for some of these issues, for example, by measuring and subtracting baseline scattering.

Advanced Applications and Current Research

The application of the Beer-Lambert Law in quantitative analysis, particularly with advanced spectrophotometry, continues to evolve, pushing the boundaries of photocatalytic research.

- Real-Time Kinetic Analysis: Traditional spectrophotometers require wavelength scanning, which can miss rapid transient events. The development of real-time UV/VIS spectroscopy using simultaneous detection with a CMOS camera allows for the complete spectral evolution of a reaction to be captured within a single camera frame [3]. This technology has been used to show how different quantities of TiO₂ nanoparticles lead to different photocatalytic degradation mechanisms for methylene blue, with all spectral changes plotted every 20 milliseconds [3].

- Addressing Analytical Challenges: Researchers continue to highlight the challenges in spectrophotometric analysis for photocatalysis. A key issue is ensuring a reliable evaluation of photocatalytic activity, especially under visible light irradiation and when dealing with dye decolorization, which may not always represent complete mineralization [22]. The precise, full-spectrum data provided by modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers is essential for differentiating between simple decolorization and the breakdown of chemical structure.

- Broad Utility: Beyond photocatalysis, the Beer-Lambert Law remains a workhorse technique. It is fundamental to analytical chemistry for determining chemical species [21], used in atmospheric science to model the absorption of sunlight by gases and particles [20], and critical in clinical settings, such as measuring bilirubin levels in blood samples [20]. The pursuit of high accuracy in these fields has led to the design of specialized, high-precision spectrophotometers, such as the one developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) for certifying Standard Reference Materials [24].

The Beer-Lambert Law remains an indispensable principle in quantitative chemical analysis. Its simple mathematical formulation, A = εlc, provides a direct link between a measurable physical quantity (absorbance) and the concentration of an analyte. In the demanding field of photocatalytic assessment research, the choice of instrumentation for applying this law is crucial. While colorimeters offer simplicity and speed for basic color measurement, UV-Vis spectrophotometers provide the comprehensive, high-fidelity spectral data necessary to unravel complex reaction mechanisms and kinetics. The advent of real-time spectroscopic techniques further enhances this capability, allowing researchers to observe fast dynamic processes with unprecedented temporal resolution. As photocatalytic research continues to strive for greater efficiency and understanding, the synergy between the robust Beer-Lambert Law and advanced spectrophotometric technology will undoubtedly continue to be a driving force in scientific discovery and innovation.

Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Each Foundational Approach

In the field of photocatalytic assessment research, the selection of an appropriate analytical instrument is paramount for obtaining reliable and meaningful data. The two foundational approaches for colorimetric analysis are spectrophotometric colorimetry, often referred to simply as colorimetry, and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. While both techniques measure how light interacts with materials, they differ significantly in their principles, capabilities, and applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these instrumental approaches, focusing on their performance characteristics for evaluating photocatalytic processes. Such processes often involve monitoring the decolorization of dyes or the degradation of colorless compounds under visible light irradiation [22]. Understanding the inherent strengths and limitations of each method enables researchers and drug development professionals to select the most appropriate tool for their specific experimental needs, thereby ensuring accurate evaluation of photocatalytic activity.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

At their core, both colorimeters and UV-Vis spectrophotometers function by passing light through a sample and measuring the resulting interaction. However, their underlying methodologies and technological sophistication differ.

Spectrophotometric Colorimetry: A colorimeter is designed to perform psychophysical sample analysis, meaning its measurements correlate directly to human color perception [1]. It typically uses filters to isolate broad bands of light, often corresponding to red, green, and blue (RGB) regions, and provides results as tristimulus values (e.g., Lab*) [1] [26]. Its operation is fundamentally based on the Beer-Lambert law, which draws a correlation between the concentration of a solute and its absorbance of light [1] [27].

UV-Vis Spectrophotometry: A UV-Vis spectrophotometer is designed for physical sample analysis via full-spectrum measurement [1]. Instead of using simple filters, it employs a monochromator (containing a prism or diffraction grating) to isolate a single, precise wavelength at a time and scans across a specified range, typically 200 to 800 nm, covering both ultraviolet and visible regions [13] [28]. This process generates a complete absorption spectrum, providing data on a sample's reflectance, absorbance, or transmittance properties at each wavelength [1].

The following diagrams illustrate the core operational workflows for each technique, highlighting key differences in components like wavelength selection.

Colorimeter Measurement Workflow

UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Measurement Workflow

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Limitations

The choice between a colorimeter and a UV-Vis spectrophotometer involves trade-offs between speed, cost, data comprehensiveness, and precision. The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of each foundational approach.

Table 1: Instrument Comparison for Photocatalytic Assessment

| Feature | Spectrophotometric Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Type | Tristimulus color difference (e.g., ΔE) [26] | Full spectral reflectance/transmittance [26] |

| Primary Output | Lab* values, color difference (ΔE) [1] [26] | Absorbance/Transmittance spectrum, concentration data [13] [29] |

| Wavelength Range | Visible light only (∼400–760 nm) [27] | Ultraviolet & Visible (∼200–760 nm) [13] [27] |

| Data Precision | Moderate, suitable for color difference [26] | High, suitable for quantitative analysis [26] |

| Key Advantage | Speed, portability, cost-effectiveness for routine QC [1] [30] | Comprehensive data, versatility, high accuracy [1] [29] |

| Inherent Limitation | Cannot identify metamerism; limited spectral data [1] | Higher cost and complexity; can be excessive for simple checks [1] |

| Ideal Use Case | Quick pass/fail color checks in quality control [26] | Color formulation, R&D, quantitative concentration analysis [1] [26] |

Advantages of Spectrophotometric Colorimetry

- High Efficiency and Speed: Colorimeters provide rapid measurement results, enabling high-throughput analysis and efficient color control on production lines or during fast-paced experimental screening [1] [30].

- Cost-Effectiveness: Colorimeters are generally more affordable than advanced spectrophotometers, both in terms of initial investment and operational expenses, offering an economical solution for basic color measurement requirements [26] [30].

- Portability and Convenience: Compact and portable designs allow for easy operation on production floors or in the field, making them ideal for on-site inspections and measurements outside a controlled laboratory [1] [30].

- Ease of Operation: Designed for simplicity, colorimeters require minimal training, making them accessible to operators with varying levels of technical experience [30].

Limitations of Spectrophotometric Colorimetry

- Limited Precision and Data: Colorimeters typically measure color using RGB or tristimulus filters, which limits their ability to detect subtle spectral nuances and provide the detailed data needed for color formulation or in-depth analysis [1] [30].

- Inability to Detect Metamerism: Metamerism occurs when colors match under one light source but not another. Colorimeters, with their fixed illuminant, cannot identify this phenomenon, which is a critical drawback for applications where color consistency under different lighting is important [1].

- Difficulty with Complex Colors: These instruments may struggle to accurately measure fluorescent, pearlescent, or metallic colors, as they do not perform a full spectral analysis [30].

- Sensitivity to External Conditions: Measurements can be affected by ambient lighting conditions and surface texture, potentially compromising accuracy if not carefully controlled [30].

Advantages of UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

- Comprehensive Data and Versatility: UV-Vis spectrophotometers provide wavelength-by-wavelength spectral analysis, offering an expansive range of data beyond what is observable by the human eye or a colorimeter. This allows for adjustable illuminant and observer settings [1].

- High Accuracy and Quantitative Capability: These instruments excel in providing precise and accurate measurements, offering high sensitivity and resolution for detecting minute changes in absorbance, which is crucial for quantifying analytes across various concentrations [29] [31].

- Non-Destructive Nature: UV-Vis allows for non-destructive analysis, meaning the sample remains unchanged after measurement. This is particularly advantageous for precious or limited samples and allows for continuous monitoring of reactions over time [29] [28].

- Broad Application Range: The technique is versatile and can be used for quantitative analysis, identifying substances based on their unique absorption spectra, and measuring turbidity in liquids simultaneously with color [1] [29].

Limitations of UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

- Cost and Complexity: UV-Vis spectrophotometers are typically more expensive than colorimeters and have a more complex design. This complexity can make them more sensitive and potentially less suited for harsh factory environments [1] [26].

- Potential for Over-specification: For applications that require only simple color difference measurements, a UV-Vis spectrophotometer may offer more functionality than necessary, resulting in an unjustified investment [1].

- Sensitivity to Stray Light: The accuracy of absorption measurements can be influenced by stray light, which can affect the accuracy of the collected spectra [28].

- Sample Requirements: For UV light analysis, quartz cuvettes are required because glass and plastic absorb UV light, adding to the cost and procedural considerations [13].

Experimental Protocols for Photocatalytic Assessment

The reliable evaluation of photocatalytic activity, particularly under visible light irradiation, requires carefully designed experimental protocols. The choice between colorimetry and UV-Vis spectroscopy will depend on the specific goals of the analysis, such as monitoring dye decolorization or tracking the degradation of colorless compounds [22].

Protocol for Dye Decolorization Monitoring

This protocol is suitable for assessing the degradation of colored organic dyes, a common test for photocatalytic activity.

Objective: To quantify the rate of decolorization of a model dye (e.g., methylene blue) by a photocatalyst under visible light.

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Photocatalyst Powder (e.g., TiO₂-based material) | The active material that, upon light absorption, generates charge carriers to degrade the dye. |

| Model Dye Solution (e.g., Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B) | The target pollutant whose concentration change is monitored via absorbance. |

| Aqueous Reaction Buffer | Provides a stable pH environment for the photocatalytic reaction. |

| Quartz or UV-Transparent Cuvettes | Holds the sample solution for measurement; quartz is essential for UV-Vis analysis in the UV range. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a known concentration of the dye solution in an appropriate aqueous buffer. Disperse a precise mass of the photocatalyst powder into the dye solution to create a suspension.

- Initial Absorbance Measurement: Before light exposure, take an aliquot of the suspension. Separate the catalyst (e.g., via centrifugation or filtration) if it interferes with the measurement. Using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, measure the absorbance spectrum of the clear supernatant, noting the maximum absorbance value (λ_max) for the dye.

- Light Irradiation: Place the main reaction suspension under visible light irradiation with constant stirring to keep the catalyst suspended. Maintain constant temperature.

- Kinetic Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., every 15 minutes), withdraw aliquots from the reaction mixture. Separate the catalyst from each aliquot.

- Analysis: Measure the absorbance of each supernatant at the dye's λ_max using either the UV-Vis spectrophotometer or a colorimeter calibrated for that specific wavelength.

- Data Calculation: The decolorization efficiency can be calculated as:

% Decolorization = [(A₀ - Aₜ) / A₀] × 100%, where A₀ is the initial absorbance and Aₜ is the absorbance at time t. For kinetic studies, plotln(A₀/Aₜ)versus time to check for pseudo-first-order behavior.

Protocol for Analysis of Colorless Compound Degradation

Monitoring the degradation of colorless compounds requires a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, as changes occur primarily in the ultraviolet range.

Objective: To track the photocatalytic degradation of a colorless organic pollutant (e.g., phenol) by observing changes in the UV absorption spectrum.

Materials and Reagents: The materials are similar to those in Protocol 4.1, with the model dye replaced by a colorless compound like phenol or salicylic acid.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a known concentration of the colorless compound in an aqueous buffer and disperse the photocatalyst as before.

- Spectral Scanning: Use a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to perform a full scan (e.g., 200-400 nm) of the solution before irradiation to identify the characteristic absorption peak(s) of the target compound.

- Light Irradiation and Sampling: Expose the suspension to visible light and collect samples at regular intervals, separating the catalyst each time.

- Spectral Analysis: For each sample, perform a full UV spectrum scan. Monitor the decrease in the characteristic UV peak(s) of the parent compound. Additionally, observe the potential appearance and subsequent disappearance of new absorption peaks, which may indicate the formation and further degradation of intermediate products.

- Data Interpretation: Quantify the degradation rate of the parent compound by the decrease in its peak absorbance. The complex spectral changes provide insight into the reaction pathway and the catalyst's efficiency in mineralizing the pollutant, not just breaking it down initially.

Application in Photocatalytic Research: A Case Example

Research into non-destructive measurement methods for agricultural commodities highlights the performance differences between these instruments. A study comparing a color spectrophotometer and Visible/Near-Infrared (Vis/NIR) spectroscopy (381–1065 nm) for predicting natural pigments in cucumber fruit found that the accuracy of each instrument depended on the target analyte [5].

Table 3: Experimental Data from Pigment Prediction in Agricultural Research

| Pigment | Instrument | Calibration Correlation (Rcal) | Prediction Correlation (Rpred) | RPD | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Carotenoid Content (TCC) | Color Spectrophotometer | 0.89 | 0.90 | 2.44 | The color spectrophotometer provided the best prediction accuracy for TCC [5]. |

| Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) | Vis/NIR Spectroscopy | 0.86 | 0.83 | 1.78 | The Vis/NIR spectrometer provided the best prediction accuracy for TFC [5]. |

This case demonstrates that the choice of instrument can significantly impact the quality of experimental data. The color spectrophotometer outperformed the more advanced spectroscopic technique for one specific pigment (carotenoids), while the Vis/NIR system was superior for another (flavonoids). This underscores the importance of aligning the instrument's inherent capabilities with the specific analytical goal, a principle that directly translates to photocatalytic assessment research where different reaction products and pathways may need to be monitored.

Practical Protocols: Applying Colorimetry and UV-Vis to Photocatalytic Reactions

Standardized Workflow for Dye Degradation Monitoring via Colorimetry

The quantitative monitoring of dye degradation is a cornerstone in evaluating the efficiency of photocatalytic processes, particularly in environmental remediation and advanced oxidation technologies. Within the broader context of comparing spectrophotometric colorimetry and UV-Vis spectroscopy for photocatalytic assessment, researchers must navigate a landscape of instrumental capabilities, methodological approaches, and data interpretation frameworks. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes serves as a key model system for assessing catalyst performance, with colorimetric methods providing accessible, cost-effective analytical pathways [32] [33]. The selection between dedicated colorimeters and versatile UV-Vis spectrophotometers significantly influences the depth of information obtained, experimental design considerations, and ultimately, the scientific conclusions drawn regarding catalytic efficiency [1].

This comparison guide objectively examines both methodologies through the specific application of dye degradation monitoring, providing experimental data, standardized protocols, and analytical frameworks to support informed methodological selection. By establishing a standardized workflow, we aim to enhance reproducibility across photocatalytic studies while clarifying the distinct advantages and limitations inherent to each analytical approach for researchers operating at the intersection of materials science, environmental chemistry, and analytical methodology.

Fundamental Principles: Colorimeters vs. UV-Vis Spectrophotometers

Understanding the core operational differences between colorimeters and UV-Vis spectrophotometers is essential for appropriate method selection in photocatalytic dye degradation studies.

Colorimeters perform psychophysical sample analysis, meaning their measurements correlate directly to human color perception. These instruments are designed with fixed components: an illuminant representing a specific light source, a 2-degree standard observer for color evaluation, and tristimulus absorption filters that isolate specific wavelengths. They provide direct tristimulus color readings (typically as L, a, b or X, Y, Z values) based on the CIE Color System, which characterizes color appearance across different dimensions [1]. The operational principle relies on the Beer-Lambert law, which establishes that solute concentration correlates with light absorbance. A colorimeter projects a single, focused wavelength through a sample solution, with a photocell detector measuring the transmitted light, and a processor converting this measurement into a readable output [1].

UV-Vis Spectrophotometers conduct physical sample analysis through full-spectrum measurement, generating data beyond human visual capability. These instruments offer greater component versatility compared to colorimeters, including adjustable illuminants that can represent various light sources, a larger 10-degree standard observer (recommended by CIE for industrial applications), and wavelength isolation through prisms, gratings, or interference filters. This enables wavelength-by-wavelength analysis of a sample's reflectance, absorbance, or transmittance properties [1]. While they can calculate psychophysical colorimetric data, their primary strength lies in capturing spectral information that facilitates advanced analytical applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Operational Differences Between Colorimeters and UV-Vis Spectrophotometers

| Feature | Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Type | Psychophysical (correlates to human perception) | Physical (full spectrum analysis) |

| Primary Output | Tristimulus values (Lab*, XYZ) | Spectral reflectance/absorbance/transmittance |

| Illuminant | Fixed | Adjustable (multiple standard illuminants) |

| Observer | Typically 2-degree | Typically 10-degree |

| Wavelength Selection | Tristimulus absorption filters | Prism, grating, or interference filter |

| Data Complexity | Direct color values | Wavelength-by-wavelength spectral data |

Experimental Protocols for Dye Degradation Monitoring

Standardized Photocatalytic Testing Framework

A robust protocol for assessing photocatalytic dye degradation begins with careful experimental design. The following methodology, adapted from research on nitrogen-doped TiO₂ nanoparticles, provides a standardized approach applicable to various catalyst-dye systems [32].

Materials and Reagents:

- Photocatalyst (e.g., N-TiO₂, ZnO, CdS nanostructures)

- Target azo dyes (e.g., Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B, Acid Orange 7)

- Deionized water

- Reaction vessels (batch reactors)

- Light source (visible or UV, depending on catalyst)

- Analytical instrumentation (colorimeter or UV-Vis spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize or obtain photocatalytic material. Characterize using appropriate techniques (XRD, SEM, TEM) to confirm morphology and composition [32] [33].

- Dye Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of target dyes at known concentrations (typically 10-20 mg/L) using deionized water.

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Combine catalyst (0.5-1.5 g/L) with dye solution in photocatalytic reactor. Stir in darkness for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium before illumination.

- Photocatalytic Degradation: Initiate illumination using appropriate light source (e.g., visible LED for modified catalysts). Maintain constant stirring throughout irradiation.

- Sampling and Analysis: Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time intervals. Separate catalyst from solution via centrifugation or filtration. Analyze supernatant using colorimeter or UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- Data Recording: Record color values (colorimeter) or full absorbance spectra (UV-Vis) for each time point. Continue measurements until degradation plateaus or completes.

The Taguchi experimental design method, employing orthogonal arrays, can efficiently optimize multiple parameters affecting photocatalytic activity (e.g., pollutant selection, catalyst amount, distance from radiation source, time protocol) with a reduced number of experiments [32].

Instrument-Specific Methodologies

Colorimetric Monitoring Protocol: For dedicated colorimeters, calibrate the instrument according to manufacturer specifications using standard references. Set appropriate measurement parameters for the target dye. For each sample aliquot, measure and record tristimulus values (L, a, b). Calculate color difference (ΔE) between initial and degraded samples using the formula: ΔE = √[(ΔL)² + (Δa)² + (Δb)²] Plot ΔE versus irradiation time to generate degradation kinetics. Alternatively, use specific color channels (particularly those showing maximum change) for quantitative assessment [1] [34].

UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Protocol: Calibrate the spectrophotometer across the relevant wavelength range (typically 200-800 nm for organic dyes). For each sample aliquot, record the full absorbance spectrum. Identify the characteristic absorption peak(s) of the target dye. Monitor the decrease in peak intensity at λmax versus irradiation time. Calculate degradation percentage using the formula: Degradation (%) = [(A₀ - Aₜ)/A₀] × 100 Where A₀ is initial absorbance and Aₜ is absorbance at time t. Plot degradation percentage versus time for kinetic analysis [34] [35].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Analysis

Direct comparison of colorimeters and UV-Vis spectrophotometers for dye degradation monitoring reveals distinct performance characteristics that influence their applicability to different research scenarios.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Dye Degradation Monitoring

| Performance Metric | Colorimeter | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Speed | Rapid (seconds per measurement) | Moderate (varies with scan range) |

| Data Comprehensiveness | Limited to color appearance values | Extensive (full spectral information) |

| Detection Sensitivity | Moderate | High |

| Metamerism Detection | No | Yes |

| Suitability for Kinetic Studies | Excellent for rapid sampling | Excellent with defined wavelengths |

| Multi-Component Analysis | Limited | Excellent (spectral deconvolution) |

| Turbidity Compensation | Limited | Advanced capabilities |

| Early Degradation Detection | Moderate | Superior |

Experimental studies demonstrate that UV-Vis spectrophotometry detects color variations earlier and more precisely than visual examination or basic colorimetry. In stress testing of pharmaceutical compounds, color changes were detected significantly earlier by UV-Vis spectrophotometry than by visual assessment [34]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly valuable for detecting initial degradation stages or subtle catalytic effects.