Source Data Strategies for Chemical Transfer Learning: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research

Transfer learning is revolutionizing computational chemistry and drug discovery by overcoming the critical bottleneck of experimental data scarcity.

Source Data Strategies for Chemical Transfer Learning: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Transfer learning is revolutionizing computational chemistry and drug discovery by overcoming the critical bottleneck of experimental data scarcity. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of source dataset strategies for transfer learning in chemistry, analyzing their mechanisms, applications, and performance. We explore foundational concepts including virtual molecular databases, simulation-to-real transfer, and chemically aware pre-training. The analysis covers diverse methodological implementations from catalytic activity prediction to binding affinity forecasting and organic photovoltaic design. Practical troubleshooting guidance addresses data augmentation, domain adaptation, and hyperparameter optimization. Through rigorous validation across pharmaceutical and materials science applications, we demonstrate how strategic source data selection enables accurate predictions with minimal target data, significantly accelerating biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Foundations of Chemical Transfer Learning: Bridging Data Gaps with Strategic Source Selection

The Data Scarcity Challenge in Chemical ML and TL as a Solution

In the data-driven landscape of modern chemical research, machine learning (ML) promises to accelerate the discovery of new catalysts, materials, and synthetic pathways. However, the practical application of ML in chemistry is fundamentally constrained by the scarcity of labeled experimental data, which is often costly, time-consuming to produce, and non-scalable [1]. This data scarcity poses a significant hurdle for training advanced ML models, which typically require large datasets to perform effectively.

Transfer learning (TL) has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome this limitation. TL involves pretraining a model on a large, readily available source dataset and then fine-tuning it on a smaller, target-specific dataset [2]. This approach allows knowledge gained from the source domain to be transferred, enhancing model performance and data efficiency in the target domain. A critical question, however, remains: what constitutes the most effective source data for pretraining models aimed at chemical applications? This article objectively compares different source dataset strategies, supported by recent experimental evidence, to guide researchers in selecting optimal approaches for their work.

Comparing Source Data Strategies for Chemical Transfer Learning

The selection of a source dataset is a pivotal decision in the TL pipeline. Chemical intuition suggests that datasets closely related to the target task should be most beneficial. In contrast, the data-hungry nature of neural networks might imply that larger, more diverse datasets are superior. Recent research has quantitatively evaluated these competing hypotheses, leading to the identification of three predominant strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Transfer Learning Source Data Strategies

| Strategy | Key Characteristic | Representative Study | Reported Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistically Related Data | Pretraining on reactions sharing core mechanistic features with the target task. | Keto et al. [3] | +13.3% Top-1 accuracy for Cope/Claisen rearrangements vs. no TL. Outperformed TL from large, diverse dataset. |

| Virtual & Computational Data | Using large, computationally generated molecular databases or first-principles data for pretraining. | Yahagi et al. [1] | Achieved high accuracy with <10 experimental data points; one order of magnitude more data-efficient than scratch model. |

| Cross-Domain Chemical Data | Leveraging large databases from other chemical subfields (e.g., reactions, drug-like molecules). | Li et al. [4] | R² > 0.94 for three virtual screening tasks and >0.81 for two others, surpassing models pretrained on direct organic materials data. |

Strategy 1: Mechanistically Related Data

This approach posits that the most valuable knowledge for a model is an understanding of the underlying electron flow and reaction mechanics. A landmark 2025 study by Keto et al. directly tested this by investigating the prediction of major products for two classes of pericyclic reactions: [3,3] rearrangements (Cope and Claisen) and [4 + 2] cycloadditions (Diels–Alder) [3].

- Experimental Protocol: The researchers used the NERF (non-autoregressive electron redistribution framework) algorithm. They pretrained multiple models on different source datasets: a large and diverse set of ~480,000 reactions from the USPTO-MIT database, and several smaller, mechanistically related datasets including Diels–Alder reactions, Ene reactions, and Nazarov cyclizations. These pretrained models were then fine-tuned on varying amounts of the target Cope and Claisen (CC) rearrangement data (from 10% to 85% of the 3,289-reaction dataset) [3].

- Performance Analysis: The key finding was that in low-data regimes (using only 10% of the CC dataset, or ~328 reactions), pretraining on mechanistically related data provided the greatest benefit. Models pretrained on Diels–Alder data achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 76.0%, a significant improvement over the baseline of 62.7% without pretraining. Notably, pretraining on the much larger but mechanistically diverse USPTO-MIT dataset yielded only a moderate improvement to 68.9%, underperforming the smaller, focused datasets [3]. This demonstrates that for these reaction prediction tasks, chemical mechanism is a more critical factor for successful knowledge transfer than dataset size alone.

Strategy 2: Virtual and Computational Data (Sim2Real)

This strategy addresses data scarcity by leveraging the scalability of computational chemistry. It involves pretraining models on large virtual molecular databases or first-principles calculations, then fine-tuning them with limited experimental data—a process known as Simulation-to-Real (Sim2Real) transfer.

- Experimental Protocol (Virtual Databases): One study constructed custom-tailored virtual molecular databases to predict the catalytic activity of organic photosensitizers. Databases were built by systematically combining donor, acceptor, and bridge fragments (Database A) or by using a reinforcement learning-based molecular generator (Databases B-D). The Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) models were pretrained on these virtual molecules using easily computable molecular topological indices as labels, rather than expensive experimental or quantum chemical data. The pretrained models were then fine-tuned on a small dataset of real-world photosensitizers [5].

- Experimental Protocol (First-Principles Calculations): Yahagi et al. (2025) proposed a chemistry-informed domain transformation for Sim2Real transfer. They predicted catalyst activity for the reverse water-gas shift reaction by first transforming abundant first-principles calculation data into the domain of experimental data using knowledge from theoretical chemistry. This bridged the fundamental gap between computational snapshots and macroscopic experimental measurements. The transformed data was then used for transfer learning with a limited set of experimental points [1].

- Performance Analysis: The virtual database approach demonstrated that pretraining on unregistered virtual molecules (94-99% of which were not in PubChem) could improve the prediction of real-world catalytic activity [5]. The first-principles method achieved a significantly high accuracy with very few experimental target data points. The TL model fine-tuned with less than ten experimental data points matched the accuracy of a model trained from scratch on over 100 experimental data points, representing an order-of-magnitude improvement in data efficiency [1].

Strategy 3: Cross-Domain Chemical Data

This strategy explores whether large chemical databases from different subfields can be effective source domains. It is particularly valuable when large, mechanistically related or virtual datasets are not available.

- Experimental Protocol: Li et al. (2024) investigated this by pretraining BERT models on several large databases: ChEMBL (2.3 million drug-like small molecules), the Clean Energy Project database (organic photovoltaic materials), and the USPTO–SMILES dataset (5.4 million molecules extracted from a chemical reaction patent database) [4]. These models were subsequently fine-tuned on smaller datasets for specific virtual screening tasks, such as predicting the HOMO-LUMO gap of organic materials like porphyrins and benzodithiophene-based molecules [4].

- Performance Analysis: The model pretrained on the USPTO–SMILES reaction database achieved the best performance, with R² scores exceeding 0.94 for three out of five virtual screening tasks and over 0.81 for the other two [4]. This outperformed models pretrained directly on organic materials databases or small molecule data. The success is attributed to the diverse array of organic building blocks in the USPTO database, which offers a broader exploration of the chemical space than domain-specific datasets, providing a strong foundational knowledge of chemistry for the model [4].

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Data and Model Performance

| Study (Year) | Target Task | Model Architecture | Optimal Source Data | Key Performance Metric | Result with TL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keto et al. (2025) [3] | Product prediction for Cope/Claisen rearrangements | NERF | Diels–Alder reactions (mechanistically related) | Top-1 Accuracy (10% target data) | 76.0% (Baseline: 62.7%) |

| Yahagi et al. (2025) [1] | Catalyst activity for reverse water-gas shift | Chemistry-Informed Sim2Real | First-principles calculations | Data Efficiency | High accuracy with <10 target data vs. >100 for scratch model |

| Li et al. (2024) [4] | HOMO-LUMO gap prediction for organic materials | BERT | USPTO-SMILES (reaction database) | R² Score | >0.94 for 3/5 tasks |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A detailed understanding of the experimental methodologies is crucial for evaluating and reproducing these TL strategies. The workflows for the two most prominent approaches—mechanistic and Sim2Real—are outlined below.

Protocol for Mechanistically Focused Transfer Learning

The workflow for this strategy, as detailed by Keto et al., involves several key stages [3]:

- Dataset Curation: Source datasets are generated through database searches (e.g., Reaxys) and rigorously curated. This involves filtering based on atom-economy, bonding patterns, and reaction templates to ensure data quality and relevance.

- Model Pretraining: A model architecture suited for reaction prediction, such as the NERF algorithm, is pretrained on the curated source dataset. NERF predicts changes in molecular graph edges (bond orders) that define a chemical reaction.

- Fine-Tuning: The pretrained model's parameters are transferred and fine-tuned on the smaller target dataset. This step involves multiple random splits of the target data to evaluate performance robustness across different training data ratios (e.g., from 10% to 85%).

- Performance Evaluation: The fine-tuned model's accuracy is evaluated on a held-out test set from the target domain, typically using metrics like Top-1 accuracy for product prediction.

Protocol for Simulation-to-Real (Sim2Real) Transfer Learning

The Sim2Real approach, exemplified by Yahagi et al., introduces a critical "domain transformation" step to bridge the gap between computation and experiment [1]:

- Computational Data Generation: A large dataset is generated through high-throughput first-principles calculations (e.g., Density Functional Theory) or by constructing virtual molecular databases using fragment-based generation or reinforcement learning [5] [1].

- Chemistry-Informed Domain Transformation: This is the defining step. The source computational data is transformed into the domain of experimental data using formulas and principles from theoretical chemistry. This aims to correct for systematic errors and account for macroscopic experimental conditions (e.g., thermal distributions, catalyst-support interactions) that are absent in single-structure calculations.

- Homogeneous Transfer Learning: After transformation, the problem is treated as a standard homogeneous TL task. A model is pretrained on the large, transformed source data.

- Fine-Tuning and Prediction: The model is finally fine-tuned on the limited set of real experimental data and used to predict real-world chemical properties or activities.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing these TL strategies requires a suite of computational "reagents"—datasets, software, and algorithms that are fundamental to the process.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Transfer Learning

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in TL | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| USPTO Database [3] [4] | Chemical Reaction Dataset | Large-scale source dataset for pretraining; provides diverse chemical building blocks. | Cross-domain pretraining for material property prediction [4]. |

| ChEMBL Database [4] | Small Molecule Dataset | Large-scale source dataset of drug-like molecules for foundational model pretraining. | Pretraining models for virtual screening of organic materials [4]. |

| NERF (Non-autoregressive Electron Redistribution Framework) [3] | Machine Learning Algorithm | Predicts reaction products by modeling changes in molecular graph edges (bond orders). | Product prediction for pericyclic reactions [3]. |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [5] | Machine Learning Algorithm | Learns from graph-based representations of molecules, ideal for structure-property relationships. | Predicting catalytic activity of photosensitizers [5]. |

| BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [4] | Machine Learning Algorithm | A transformer-based model that can be pretrained on SMILES strings to learn chemical language. | Virtual screening of organic materials after pretraining on SMILES strings [4]. |

| RDKit / Mordred [5] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Generates molecular descriptors and topological indices for use as pretraining labels or model features. | Providing cost-efficient pretraining labels for virtual molecules [5]. |

The strategic selection of source data is paramount for successfully applying transfer learning to overcome data scarcity in chemical machine learning. Experimental evidence from recent, high-quality studies demonstrates that there is no single best strategy; the optimal choice is highly dependent on the specific target task and available resources.

For predicting reaction outcomes, leveraging smaller, mechanistically related datasets has proven more data-efficient than using vast, chemically diverse ones [3]. When experimental data is extremely limited, pretraining on virtual or first-principles databases (Sim2Real) offers a powerful pathway to high accuracy and radical data efficiency, though it requires careful domain transformation [5] [1]. Finally, when direct data is unavailable, pretraining on large, cross-domain chemical databases like USPTO can provide a robust foundational model that excels in various downstream tasks, including molecular property prediction [4].

These strategies collectively form a versatile toolkit for chemical researchers. By aligning the source data strategy with the nature of the chemical problem, scientists can harness the full potential of machine learning to navigate the vast chemical space efficiently, ultimately accelerating the discovery and optimization of new molecules and reactions.

Virtual Molecular Databases as Abundant Source Domains

The application of machine learning (ML) in chemistry and drug discovery has been fundamentally constrained by the limited availability of experimental training data. This data scarcity problem is particularly pronounced in specialized domains such as catalysis research and organic materials science, where acquiring large, labeled datasets through experiments or quantum chemical calculations remains prohibitively expensive and time-consuming [5] [4] [6]. Transfer learning has emerged as a powerful paradigm to address this limitation by leveraging knowledge acquired from data-rich source domains to enhance model performance on data-scarce target tasks [7] [8]. Within this framework, virtual molecular databases—computer-generated collections of molecules that may not yet have been synthesized or tested—represent an increasingly important class of source domains. These databases offer access to vast regions of chemical space beyond what is available in experimental repositories, potentially containing over 10⁶⁰ organic molecules that remain unregistered in existing databases [5]. This comparison guide examines the performance of different virtual database strategies as source domains for transfer learning in molecular property prediction, providing researchers with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate approaches for their specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of Virtual Database Strategies

Virtual molecular databases vary significantly in their generation methodologies, chemical space coverage, and suitability as transfer learning sources. The table below systematically compares four prominent approaches identified in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Molecular Database Strategies

| Database/ Strategy | Generation Method | Chemical Space Coverage | Pretraining Labels | Reported Transfer Learning Performance | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom-Tailored Virtual Databases [5] | Fragment-based combinatorial assembly & reinforcement learning | Broad, OPS-like chemical space; 94-99% unregistered in PubChem | Molecular topological indices (RDKit, Mordred) | Improved prediction of photocatalytic activity in C-O bond formation | Catalysis research, specialized molecular classes |

| USPTO-Reaction Derived Database [4] | Extraction from chemical reaction patents (USPTO) | Highly diverse organic building blocks | Unsupervised (SMILES sequences) | R² > 0.94 for 3/5 organic material property prediction tasks | Organic materials virtual screening, general molecular properties |

| Large-Scale Docking Databases [9] | Physics-based docking against protein targets | Billions of make-on-demand compounds | Docking scores & poses | Pearson R = 0.86 for scoring prediction with 1M training samples | Drug discovery, binding affinity prediction |

| Pre-trained Model (PGM) [7] | Principal Gradient Measurement across multiple source datasets | 12 benchmark datasets from MoleculeNet | Gradient-based transferability metrics | Strong correlation with actual transfer learning performance | Optimal source task selection, avoiding negative transfer |

Key Performance Insights

The comparative analysis reveals several important patterns. First, specialized virtual databases employing systematic fragment-based generation demonstrate particular value for niche applications like organic photosensitizer design, where they improve predictive performance despite using molecular topological indices as pretraining labels—properties not directly related to the target task of photocatalytic activity prediction [5]. Second, reaction-derived databases like USPTO-SMILES offer exceptional diversity of organic building blocks, resulting in superior performance across multiple organic material property prediction tasks [4]. This approach achieves R² scores exceeding 0.94 for predicting HOMO-LUMO gaps in organic photovoltaic materials and porphyrin-based dyes.

Third, the scale of virtual databases significantly impacts their utility as source domains. Databases derived from large-scale docking campaigns provide access to billions of explicitly evaluated molecules, with studies demonstrating that model performance improves steadily with training set size, achieving Pearson correlations of 0.86 with 1 million training samples [9]. However, this relationship may not be monotonic in all cases, as some research indicates that pretraining with excessively large but dissimilar datasets can sometimes yield suboptimal results compared to more targeted approaches [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Virtual Database Construction Workflows

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Database Construction and Application

| Experimental Phase | Key Procedures | Technical Parameters | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database Generation | Fragment-based combinatorial assembly; RL with ε-greedy policy; Extraction from reaction databases | 30 donor, 47 acceptor, 12 bridge fragments; ε values: 1.0, 0.1, or decreasing 1.0→0.1; ~25,000-30,000 molecules per database | Chemical space visualization (UMAP); Molecular weight distribution analysis; Tanimoto similarity metrics |

| Pretraining Label Generation | Calculation of molecular topological indices; Unsupervised SMILES tokenization; Docking score computation | 16 RDKit/Mordred descriptors (Kappa2, BertzCT, etc.); SMILES tokenization vocabulary; DOCK3.7/3.8 scoring functions | SHAP analysis for feature importance; Benchmarking on CASF2016; Decoy-based validation |

| Transfer Learning Implementation | GCN pretraining on virtual database; Fine-tuning on experimental data; Gradient-based transferability measurement | Model: GCN or BERT; Training: Supervised pretraining → fine-tuning; Evaluation: Mean absolute error, R², enrichment factors | Cross-validation on target tasks; Comparison to non-TL baselines; Ablation studies |

Implementation Workflows

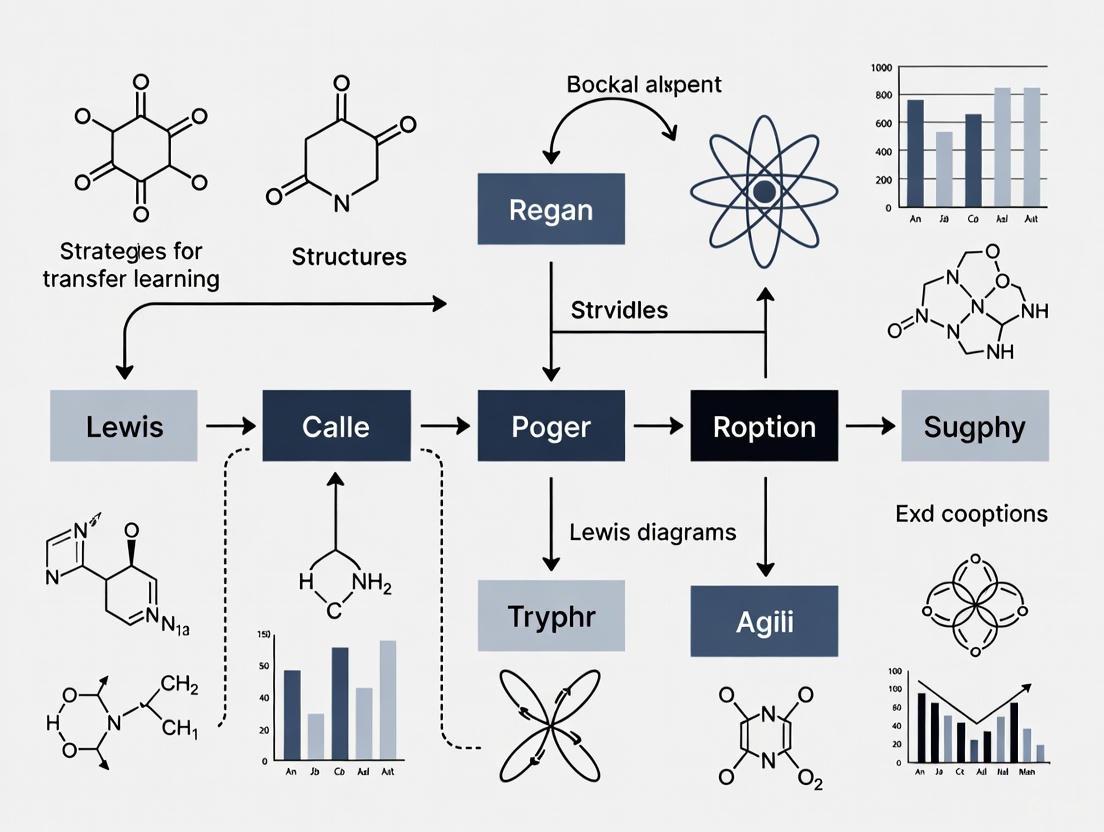

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for utilizing virtual molecular databases in transfer learning, from database generation to model evaluation:

Critical Experimental Considerations

Several methodological factors significantly influence the success of transfer learning from virtual databases. First, the selection of pretraining labels requires careful consideration. While molecular topological indices offer computational efficiency and demonstrate transferability to unrelated target tasks [5], unsupervised approaches using SMILES tokenization provide greater flexibility and have shown superior performance in cross-domain applications [4]. Second, strategic sampling of training data from virtual databases can dramatically enhance model performance. For example, stratified sampling approaches that oversample high-performing molecules (e.g., top 1% of docking scores) can improve logAUC metrics by up to 57% compared to random sampling, despite potentially lower overall Pearson correlations [9].

Third, the measurement of task relatedness between source and target domains represents a crucial advancement in avoiding negative transfer—the phenomenon where transfer learning actually degrades model performance. Principal Gradient-based Measurement (PGM) and similar approaches enable researchers to quantify transferability prior to fine-tuning, providing valuable guidance for source dataset selection [7] [8]. Implementation of these methodologies requires careful attention to gradient calculation techniques and distance metrics in the latent task space.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Databases | PubChem, ChEMBL, ZINC, Clean Energy Project (CEP) Database | Source of experimental molecules for validation and benchmarking; Reference for chemical space coverage analysis | Publicly available; ChEMBL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl |

| Virtual Database Generation Tools | RDKit, Molecular generators (systematic & RL-based), Reaction extractors | Construction of custom virtual databases; Fragment-based molecule assembly | RDKit: Open-source; Custom generators: Research code |

| Descriptor Calculation Packages | RDKit, Mordred | Computation of molecular topological indices and structural descriptors for pretraining labels | Open-source Python packages |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Chemprop, PaiNN, BERT-based architectures | Implementation of graph neural networks and transformer models for transfer learning | Open-source; Available on GitHub |

| Transferability Metrics | Principal Gradient-based Measurement (PGM), MoTSE | Quantification of task relatedness between source and target domains | Research code from publications |

| Validation Benchmarks | CASF2016, DUD, MoleculeNet | Standardized benchmarks for evaluating virtual screening performance and scoring functions | Publicly available datasets |

Implementation Recommendations

Successful implementation of virtual database strategies requires strategic selection from available tools. For specialized applications in catalysis or materials science, fragment-based approaches using RDKit combined with topological descriptors provide a balanced combination of specificity and computational efficiency [5]. For broad virtual screening applications in drug discovery, leveraging existing large-scale docking databases [9] or reaction-derived molecular collections [4] offers immediate access to billions of compounds without requiring custom database generation. For researchers concerned about negative transfer, implementing transferability measurement tools like PGM [7] before full-scale fine-tuning can prevent performance degradation and guide optimal source task selection.

The evidence from comparative studies indicates that virtual molecular databases represent a transformative resource for addressing data scarcity in chemical ML, but their effectiveness depends heavily on strategic implementation. Custom-tailored virtual databases demonstrate superior performance for specialized applications like organic photosensitizer design [5], while reaction-derived databases like USPTO-SMILES offer exceptional versatility for general molecular property prediction [4]. Large-scale docking databases provide unprecedented scale for drug discovery applications [9], and emerging transferability metrics like PGM offer critical guidance for avoiding negative transfer [7]. As the field advances, the integration of these approaches with standardized validation benchmarks and open-source tools will continue to expand the boundaries of data-driven molecular discovery.

Simulation-to-Real (Sim2Real) transfer learning has emerged as a transformative methodology for addressing the fundamental challenge of data scarcity in chemistry and materials science research. This approach leverages abundant, computationally generated data to build predictive models that are subsequently fine-tuned with limited experimental datasets, effectively bridging the gap between theoretical simulations and real-world laboratory results. As experimental data remains costly, time-consuming to produce, and often limited in volume, Sim2Real strategies offer a promising pathway to accelerate discovery across diverse domains including polymer science, catalyst development, and drug discovery.

The core premise of Sim2Real transfer learning involves pretraining machine learning models on large-scale computational databases—such as those derived from molecular dynamics simulations, first-principles calculations, or virtual molecular generation—followed by transfer and fine-tuning to experimental domains where labeled data is scarce. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of source dataset strategies, evaluating their performance, scalability, and practical implementation across multiple chemistry research applications, to guide researchers in selecting optimal approaches for their specific experimental challenges.

Comparative Analysis of Source Data Strategies

Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative performance of Sim2Real transfer learning approaches in materials science and chemistry

| Methodology | Source Data Type | Target Application | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Based Simulation Scaling [10] | Molecular dynamics simulations (~70,000 samples) | Polymer property prediction | Power-law error reduction with scaling factor α; Transfer gap C | 39-607 experimental samples for fine-tuning |

| Virtual Molecular Databases [5] | Topological indices of generated molecules (~25,000 samples) | Organic photosensitizer catalytic activity | Improved prediction accuracy vs. non-pretrained models | Effective with limited experimental data |

| Chemistry-Informed Domain Transformation [1] | First-principles calculations | Catalyst activity for reverse water-gas shift reaction | Accuracy superior to scratch model with 100+ samples | High accuracy with <10 experimental samples |

| Cross-Reaction Transfer [11] | High-throughput experimentation data (~100 samples per nucleophile) | Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling conditions | ROC-AUC up to 0.928 for mechanistically similar reactions | Requires minimal target data for effective transfer |

Table 2: Scaling law parameters for polymer property prediction via Sim2Real transfer

| Polymer Property | Computational Data Size | Experimental Data Size | Scaling Factor (α) | Transfer Gap (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractive Index | Up to 70,000 MD simulations | 234 polymers | Power-law scaling observed | Convergent limit |

| Density | Up to 70,000 MD simulations | 607 polymers | Power-law scaling observed | Convergent limit |

| Specific Heat Capacity | Up to 70,000 MD simulations | 104 polymers | Power-law scaling observed | Convergent limit |

| Thermal Conductivity | Up to 70,000 MD simulations | 39 polymers | Power-law scaling observed | Convergent limit |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Physics-Based Simulation Scaling Approach

The physics-based simulation methodology employs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to generate extensive computational databases for polymer property prediction [10]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Source Data Generation: Utilizing the RadonPy Python library for fully automated all-atom classical MD simulations of amorphous polymers using LAMMPS (large-scale atomistic/molecular massively parallel simulator) to generate approximately 70,000 polymer property measurements.

- Descriptor Engineering: Representing each polymer repeating unit as a 190-dimensional vector capturing compositional and structural features.

- Model Architecture: Implementing fully connected multi-layer neural networks to map polymer descriptors to target properties.

- Transfer Process: Pretraining neural networks on computational data, followed by fine-tuning with experimental data from the PoLyInfo database.

- Performance Validation: Conducting 500 independent repetitions for each dataset size to evaluate predictive performance on held-out experimental samples.

This approach demonstrates a power-law scaling relationship where prediction error on real systems decreases systematically with increasing computational data size, following the form R(n) = Dn^(-α) + C, where α represents the scaling rate and C denotes the transfer gap [10].

Virtual Molecular Database Strategy

The virtual molecular database approach focuses on generating custom-tailored molecular structures for transfer learning in catalysis research [5]:

- Fragment-Based Generation: Constructing virtual databases by systematically combining 30 donor fragments, 47 acceptor fragments, and 12 bridge fragments to create 25,350 molecules with D-A, D-B-A, D-A-D, and D-B-A-B-D architectures.

- Reinforcement Learning Enhancement: Implementing a tabular reinforcement learning system with Tanimoto coefficient-based rewards to generate additional diverse molecular databases (Databases B-D) with enhanced chemical space coverage.

- Pretraining Label Selection: Utilizing molecular topological indices (Kappa2, PEOE_VSA6, BertzCT, etc.) from RDKit and Mordred descriptor sets as cost-effective pretraining labels, validated through SHAP-based analysis.

- Transfer Learning Implementation: Applying graph convolutional network (GCN) models pretrained on virtual molecular databases to predict photocatalytic activity for real-world organic photosensitizers in C-O bond formation reactions.

This methodology demonstrates that transfer from intuitively unrelated molecular properties (topological indices) can enhance prediction of catalytic activity, even when 94-99% of virtual molecules are unregistered in PubChem [5].

Chemistry-Informed Domain Transformation

The chemistry-informed domain transformation method specifically addresses the fundamental scale differences between first-principles calculations and experimental measurements [1]:

- Domain Bridging: Employing theoretical chemistry principles to transform computational data from simulation space to experimental domain, addressing disparities in scale (microscopic single structures vs. macroscopic composite systems) and kinetics.

- Theoretical Framework: Harnessing prior knowledge of chemistry, statistical ensembles, and source-target quantity relationships to enable homogeneous transfer learning.

- Application Protocol: Implementing the approach for catalyst activity prediction in reverse water-gas shift reaction, using abundant first-principles data complemented by limited experimental validation.

- Validation: Demonstrating significantly higher accuracy with few target data points (less than ten) compared to traditional models requiring over 100 experimental samples.

This approach achieves positive transfer in both accuracy and data efficiency, effectively leveraging the scalability of computational data while correcting for systematic errors using minimal experimental data [1].

Cross-Reaction Condition Transfer

The cross-reaction transfer methodology applies machine learning to leverage reaction condition knowledge across different nucleophile types in Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions [11]:

- Data Curation: Utilizing high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data from 1536-well plate nanomole-scale screenings of Pd-catalyzed coupling reactions.

- Model Architecture: Implementing random forest classifier models trained under cross-validation for each nucleophile type (amides, sulfonamides, pinacol boronate esters, etc.).

- Transfer Validation: Evaluating model performance on reactions involving different nucleophile types using receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC-AUC) metrics.

- Active Learning Integration: Combining transfer learning with active learning for challenging scenarios where initial transferred models show limited predictivity.

This approach demonstrates that mechanism-based similarity between source and target domains is crucial for successful transfer, with ROC-AUC values reaching 0.928 for closely related reaction mechanisms [11].

Visualizing Sim2Real Workflows

Diagram 1: Sim2Real transfer learning workflow showing source domain strategies, transfer methodologies, and target applications with performance metrics.

Diagram 2: Scaling law observation workflow for determining optimal computational dataset sizes for effective Sim2Real transfer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key computational and experimental resources for Sim2Real transfer implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS [10] | Simulation Software | Large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator for molecular dynamics | Polymer property prediction through all-atom classical MD simulations |

| RadonPy [10] | Python Library | Fully automated all-atom classical MD simulations for polymeric materials | High-throughput generation of computational polymer property databases |

| RDKit [5] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Calculation of molecular descriptors and topological indices | Generation of pretraining labels for virtual molecular databases |

| GOPS Platform [12] | RL Development Framework | General Optimal control Problems Solver with Simulink integration | Reinforcement learning-based energy management strategy development |

| NVIDIA Omniverse [13] | Simulation Platform | 3D simulation environment for robotic chemical experimentation | Chemistry3D toolkit for robotic interaction in chemical experiments |

| PoLyInfo Database [10] | Experimental Database | Curated experimental polymer properties | Fine-tuning and validation data for polymer property prediction |

| High-Throughput Experimentation [11] | Experimental Methodology | Nanomole-scale screening in 1536-well plates | Generating reaction condition datasets for cross-coupling reactions |

The comparative analysis of Sim2Real transfer learning strategies reveals several key insights for researchers selecting source dataset approaches. Physics-based simulation scaling demonstrates quantifiable power-law relationships between computational data size and experimental prediction accuracy, providing clear guidelines for database development investment. Virtual molecular databases offer exceptional flexibility for tailoring source data to specific chemical domains, even with minimal direct experimental relevance in pretraining labels. Chemistry-informed domain transformation stands out for its ability to bridge fundamental scale disparities between computational and experimental systems, achieving remarkable data efficiency with fewer than ten experimental samples required for effective transfer.

Cross-reaction condition transfer exemplifies the importance of mechanistic similarity between source and target domains, with performance highly correlated to reaction mechanism conservation. Across all methodologies, the integration of active learning with transfer strategies provides a powerful approach for challenging scenarios where initial transfer yields limited benefits. These comparative findings enable researchers to strategically select and implement Sim2Real approaches based on their specific domain constraints, data availability, and accuracy requirements, ultimately accelerating the translation of computational predictions to real-world chemical applications.

The evolution of artificial intelligence in chemistry has ushered in a paradigm shift from mere pattern recognition to genuine molecular design, a transition fundamentally underpinned by pre-training strategies. The core challenge lies in navigating the critical trade-off between two divergent approaches: mechanism-driven pre-training, which prioritizes chemical understanding through curated data with explicit structural or relational information, and size-driven pre-training, which leverages massive-scale datasets to capture broad chemical patterns through statistical learning. This dichotomy represents a fundamental tension in developing effective transfer learning frameworks for chemical research, where the choice of source data strategy directly influences model performance across diverse downstream tasks including property prediction, retrosynthesis, and reaction optimization.

Chemical foundation models have progressed from understanding molecular structures to actively designing novel compounds and planning complex synthetic pathways. Early approaches like ChemBERTa established that transformers could learn meaningful molecular representations from SMILES strings, while contemporary systems like Chemformer integrated BART transformers with Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to achieve 95% route success in multi-step synthesis planning—significantly outperforming traditional methods [14]. This evolution reflects a broader transition from passive analysis to active creation in chemical AI, where pre-training strategies play a decisive role in determining model capabilities.

Comparative Analysis of Pre-training Strategies

Mechanism-Driven Pre-training Approaches

Mechanism-driven pre-training emphasizes quality and chemical relevance over sheer volume, incorporating explicit structural knowledge or domain-specific constraints to guide model learning. This approach recognizes that chemical space, estimated to contain over 10^60 molecules, remains largely unexplored in existing databases, creating opportunities for carefully designed virtual molecular systems to enhance model performance [5].

Virtual Molecular Databases with Topological Indices: One innovative implementation of mechanism-driven pre-training involves constructing custom-tailored virtual molecular databases enriched with topological indices as pre-training labels. Researchers have generated databases of approximately 25,000 molecules by systematically combining donor, acceptor, and bridge fragments, then using molecular topological indices from RDKit and Mordred descriptor sets as pretraining targets [5]. These indices—including Kappa2, PEOE_VSA6, BertzCT, and others—provide chemically meaningful learning signals despite not being directly related to downstream tasks like photocatalytic activity prediction. When used to pre-train Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), these virtual databases significantly improved prediction of catalytic activity for real-world organic photosensitizers, demonstrating effective knowledge transfer even though 94-99% of the virtual molecules were unregistered in PubChem [5].

Cross-Modal Alignment with 3D Geometry: YieldFCP represents another mechanism-driven approach that employs fine-grained cross-modal pre-training to link molecular SMILES sequences with 3D geometric data [15]. By focusing on atomic-level interactions between sequence and structural representations, this method achieves more chemically aware representations that significantly enhance reaction yield prediction, particularly in real-world scenarios where accurate yield forecasting remains challenging. The cross-modal projector explicitly models the relationship between symbolic representations and spatial arrangements, embedding physical chemical constraints directly into the learning process [15].

Reaction-Centric Representation Learning: ReactionT5 implements a mechanism-aware strategy through two-stage pre-training that first learns compound-level representations followed by reaction-level understanding [16]. The model uses special role tokens (REACTANT:, REAGENT:, etc.) to explicitly encode the function of each component within a reaction, creating structured representations that preserve chemical context. This approach diverges from treating reactions as simple collections of molecules by instead modeling the complete reaction context as a single textual sequence with labeled roles, enabling the model to learn transformation patterns rather than just molecular similarities [16].

Size-Driven Pre-training Approaches

In contrast to mechanism-driven methods, size-driven pre-training operates on the principle that scale alone can lead to emergent chemical understanding when sufficient diverse data is available. This approach leverages massive, often heterogeneous datasets to capture the broad statistical regularities of chemical space without explicit encoding of chemical mechanisms or relationships.

Large-Scale Reaction Databases: The most direct implementation of size-driven pre-training utilizes extensive reaction databases like the Open Reaction Database (ORD) to train models on diverse chemical transformations. ReactionT5's reaction pre-training stage employs this strategy, processing the entire reaction context—including reactants, reagents, solvents, catalysts, and products—as a single textual sequence [16]. By training on ORD's comprehensive collection of reactions spanning various conditions and reaction types, the model develops a general understanding of chemical reactivity that transfers effectively to downstream tasks including product prediction (97.5% accuracy), retrosynthesis (71.0% accuracy), and yield prediction (R² = 0.947) [16].

Massive Molecular Corpora: Early chemical language models like ChemBERTa established the viability of pre-training on large-scale molecular datasets such as ZINC-15, which contains approximately 1.5 billion drug-like compounds [14]. This approach adapts the masked language modeling objective from natural language processing to SMILES strings, randomly masking tokens and training the model to predict the missing portions based on molecular context. The scale of these datasets—often comprising hundreds of millions of molecules—allows models to learn fundamental chemical grammar and structural patterns without explicit supervision or mechanism encoding [14].

Combined Molecular and Reaction Datasets: Some size-driven approaches further amplify scale by combining multiple data types and sources. For instance, models may pre-train initially on large molecular libraries before further pre-training on reaction datasets, effectively stacking scale across different data modalities. This sequential scaling approach builds general molecular understanding before specializing in transformation patterns, potentially capturing both structural and reactive aspects of chemical space [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Pre-training Dataset Strategies

| Dataset Type | Representative Examples | Scale | Key Characteristics | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Molecular Databases | Custom fragment-based databases | ~25,000 molecules | Contains unregistered molecules with topological indices; high chemical diversity | Transfer learning for property prediction with limited data [5] |

| Commercial Compound Libraries | ZINC-15 | ~1.5 billion molecules | Drug-like compounds (MW ≤ 500, LogP ≤ 5); real chemical space | Molecular representation learning; foundation model pre-training [14] |

| Reaction Databases | Open Reaction Database (ORD) | Extensive reaction collection | Broad reaction spectrum with role annotations (reactants, reagents, products) | Reaction prediction; retrosynthesis; yield forecasting [16] |

| Patent Reaction Data | USPTO | Hundreds of thousands of reactions | Experimentally validated reactions from patents | Single-step and multi-step reaction prediction [14] [15] |

Experimental Performance Comparison

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Tasks

Rigorous evaluation of pre-training strategies reveals distinct performance patterns across chemical tasks, with mechanism-driven and size-driven approaches demonstrating complementary strengths. The PaRoutes benchmark, developed by AstraZeneca researchers, provides standardized evaluation metrics including route success rates, tree edit distance for route similarity, and diversity measures for multi-step synthesis planning [14].

ReactionT5, benefiting from both size and structured reaction representation, achieves remarkable performance across multiple domains: 97.5% accuracy in product prediction, 71.0% in retrosynthesis, and a coefficient of determination of 0.947 in yield prediction [16]. More significantly, when fine-tuned with limited data, ReactionT5 maintains performance comparable to models fine-tuned on complete datasets, demonstrating exceptional transfer learning capability derived from its comprehensive pre-training strategy [16].

Mechanism-driven approaches show particular strength in data-scarce scenarios. GCNs pre-trained on virtual molecular databases with topological indices consistently outperform randomly initialized models when predicting photocatalytic activity for real-world organic photosensitizers, despite the pretraining labels being unrelated to the downstream task [5]. Similarly, YieldFCP's cross-modal pre-training demonstrates superior performance on real-world electronic laboratory notebook data and organic reaction publications, highlighting the value of physically-grounded representations in practical applications [15].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Models with Different Pre-training Strategies

| Model | Pre-training Strategy | Product Prediction Accuracy | Retrosynthesis Accuracy | Yield Prediction (R²) | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReactionT5 [16] | Two-stage: compounds then reactions on ORD | 97.5% | 71.0% | 0.947 | High (performs well with limited fine-tuning data) |

| Chemformer [14] | BART architecture pre-trained on 100M SMILES from ZINC-15 | N/A | Achieves 95% route success in synthesis planning | N/A | Moderate (requires fine-tuning on reaction data) |

| GCN with Topological Pre-training [5] | Virtual molecules with topological indices as labels | N/A | N/A | Significantly improved catalytic activity prediction | High (effective with small real datasets) |

| YieldFCP [15] | Fine-grained cross-modal (SMILES + 3D geometry) | N/A | N/A | Superior on real-world datasets | High (maintains performance in realistic scenarios) |

The Scaling Laws in Chemical Pre-training

The relationship between dataset size and model performance in chemical AI appears to follow different patterns for mechanism-driven versus size-driven approaches. For size-driven methods, performance typically improves logarithmically with increasing data scale, consistent with trends observed in natural language processing. Chemformer's pre-training on 100 million unlabeled SMILES strings from ZINC-15 provided sufficient coverage of drug-like chemical space to enable effective transfer to synthesis planning tasks [14].

However, mechanism-driven approaches demonstrate that strategic data curation can achieve comparable performance with significantly smaller datasets. The virtual molecular database approach achieves meaningful transfer learning with only 25,000-30,000 carefully designed molecules—several orders of magnitude smaller than ZINC-15—by ensuring maximum chemical diversity and relevance through systematic fragment combination and reinforcement learning-based generation [5]. This suggests that chemical awareness in pre-training can partially compensate for data scarcity, particularly for specialized domains where relevant data is inherently limited.

Methodological Deep Dive: Experimental Protocols

Virtual Molecular Database Construction

The creation of mechanism-aware pre-training datasets follows rigorous experimental protocols to ensure chemical relevance and diversity:

Fragment-Based Molecular Assembly: Researchers first curate libraries of chemical fragments representing donors (30 fragments), acceptors (47 fragments), and bridges (12 fragments) based on established organic photosensitizer designs [5]. These fragments include aryl or alkyl amino groups, carbazolyl groups with various substituents, nitrogen-containing heterocyclic rings, and π-conjugated systems.

Systematic and RL-Based Generation: Database A is constructed through systematic combination of fragments into D-A, D-B-A, D-A-D, and D-B-A-B-D structures, generating 25,350 molecules. Databases B-D employ reinforcement learning with different exploration-exploitation tradeoffs (ε-greedy with ε=1, 0.1, and decreasing from 1 to 0.1 respectively), using the inverse of averaged Tanimoto coefficients as rewards to maximize molecular diversity [5].

Topological Index Calculation: The resulting molecules are characterized using 16 topological indices (Kappa2, PEOE_VSA6, BertzCT, etc.) from RDKit and Mordred descriptor sets, which serve as pre-training labels. These indices are selected based on SHAP analysis confirming their significance for predicting reaction yields [5].

Two-Stage Reaction Pre-training

The size-driven approach exemplified by ReactionT5 implements a comprehensive two-stage pre-training methodology:

Compound Pre-training Stage: The T5 model first undergoes span-masked language modeling on a large compound library, using a SentencePiece unigram tokenizer trained specifically on chemical structures. During this stage, 15% of tokens are randomly masked with an average span length of three tokens, requiring the model to learn meaningful molecular representations to reconstruct missing portions [16].

Reaction Pre-training Stage: The compound-trained model then processes complete reaction contexts from ORD with special role tokens (REACTANT:, REAGENT:, PRODUCT:) prepended to respective SMILES sequences. The entire reaction is formatted as a single text string, enabling the model to learn transformation patterns rather than just molecular properties [16].

Fine-tuning Protocol: For downstream tasks, the pre-trained model undergoes task-specific fine-tuning with limited data (often just 1% of available training examples), demonstrating the efficiency of knowledge transfer from pre-training [16].

Cross-Modal Pre-training Implementation

YieldFCP's mechanism-driven approach employs a sophisticated cross-modal alignment strategy:

Multi-Modal Data Representation: Each reaction is represented both as SMILES sequences and 3D molecular geometries, creating parallel modalities capturing different aspects of chemical information [15].

Fine-Grained Alignment: Rather than aligning complete molecular representations, the model implements atomic-level cross-modal projection that links specific atoms in sequence representations to their counterparts in geometric representations. This fine-grained alignment ensures that spatial relationships and electronic effects are preserved in the learned representations [15].

Self-Supervised Pre-training: The model is pre-trained on large-scale reaction datasets from USPTO and other sources using self-supervised objectives that leverage the natural correspondence between sequence and structure modalities without requiring explicit labeling [15].

Visualization of Pre-training Workflows

Diagram 1: Comparison of Pre-training Strategy Workflows

Diagram 2: ReactionT5 Two-Stage Pre-training Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Reagents for Chemical Pre-training Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Representative Examples | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fragments | Building blocks for virtual database construction | Donor, acceptor, bridge fragments | Mechanism-driven pre-training; exploring underrepresented chemical space [5] |

| Topological Indices | Quantitative structure descriptors | Kappa2, BertzCT, PEOE_VSA6 from RDKit/Mordred | Pre-training labels; molecular complexity quantification [5] |

| Reaction Databases | Curated collections of chemical transformations | Open Reaction Database (ORD), USPTO | Size-driven pre-training; reaction pattern learning [16] |

| Molecular Libraries | Large collections of compound structures | ZINC-15 (1.5B drug-like molecules) | Foundation model pre-training; chemical space coverage [14] |

| Cross-Modal Aligners | Linking different molecular representations | Sequence-to-structure projectors | Multi-modal pre-training; 3D geometric integration [15] |

| Tokenization Schemes | Converting molecules to model inputs | SentencePiece unigram, role-specific tokens | Architecture-specific input processing [16] |

The trade-off between mechanism-driven and size-driven pre-training strategies represents a fundamental consideration in developing next-generation chemical AI systems. Mechanism-driven approaches demonstrate particular value in data-scarce scenarios and specialized domains where chemical intuition and explicit constraints guide model development, while size-driven methods excel in broad-coverage tasks where diverse pattern recognition is essential.

The most promising direction emerging from current research involves hybrid strategies that leverage both chemical awareness and scale. ReactionT5's two-stage pre-training—combining general compound understanding with specialized reaction context—demonstrates how sequential scaling across data types can yield superior performance [16]. Similarly, approaches that integrate virtual molecular databases with real reaction data may offer optimal knowledge transfer for specialized applications [5].

As chemical AI continues to evolve, the optimal balance between mechanism and size will likely remain context-dependent, varying with specific application requirements, data availability, and computational constraints. However, the emerging consensus suggests that strategic integration of both approaches—leveraging scale where possible and mechanism where necessary—will drive the most significant advances in transfer learning for chemical research. Future work should focus on developing more sophisticated mechanism encoding techniques that preserve chemical intuition while scaling to larger datasets, ultimately creating models that combine the systematic reasoning of expert chemists with the pattern recognition capabilities of modern deep learning.

In the domain of chemical sciences and drug discovery, the strategic selection of molecular representation is a foundational determinant of success in machine learning (ML) and transfer learning applications. Molecular representation serves as the critical bridge between chemical structures and their predicted biological activities or physicochemical properties, directly influencing model accuracy, generalizability, and computational efficiency [17]. The evolution from traditional, rule-based descriptors to sophisticated, data-driven learned representations has created a complex landscape of strategies, each with distinct advantages for specific transfer learning scenarios [17].

This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary molecular representation strategies, with a specific focus on their performance characteristics within transfer learning frameworks. Transfer learning in chemistry often involves pre-training models on large, unlabeled molecular datasets followed by fine-tuning on smaller, task-specific labeled data, making the choice of representation pivotal for capturing transferable chemical knowledge [18]. We examine graph networks, topological indices, topological data analysis, and sequence-based approaches, synthesizing experimental data from recent benchmark studies to inform optimal strategy selection for research applications.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Strategies

Defining the Representation Paradigms

Graph Networks: Represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) learn representations through message-passing between connected nodes, naturally capturing molecular topology [19] [18]. Recent innovations include Molecular Geometric Deep Learning (Mol-GDL), which incorporates both covalent and non-covalent interactions on an equal footing, and Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs), which integrate Fourier-based learnable univariate functions for enhanced expressivity and interpretability [20] [19].

Topological Indices (TIs): Mathematical descriptors derived from chemical graph theory that quantify topological aspects of molecular structure. Examples include the forgotten index (

FN*), the second Zagreb index (M2*), and the Harmonic index (HMN). These are fixed numerical values that are computationally efficient and highly interpretable [21] [22].Topological Data Analysis (TDA): An advanced approach that uses principles from algebraic topology to analyze the shape and structure of data. TopoLearn is a representative model that uses persistent homology to extract topological descriptors from molecular feature spaces, such as the connectivity of data at different scales, to predict the effectiveness of representations [23] [24].

Sequence-Based Representations (e.g., SMILES): Represent molecules as text strings using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) or similar notations. These can be processed by natural language processing models like Transformers [17] [24].

Performance Comparison Across Benchmark Tasks

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representation Strategies on Benchmark Datasets

| Representation Strategy | Specific Model/Index | Dataset(s) | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Key Advantage for Transfer Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Networks | Mol-GDL [19] | 14 Benchmark Datasets | Accuracy (vs. SOTA) | Outperformed SOTA methods | Captures both covalent & non-covalent interactions |

| KA-GNN [20] | 7 Molecular Benchmarks | Prediction Accuracy | Consistently outperformed conventional GNNs | Superior parameter efficiency & interpretability | |

| CRGNN [25] | Molecular Benchmarks (small data) | Performance under data insufficiency | Outperformed methods using augmentation | Robustness via consistency regularization | |

| Topological Indices | Parametric Temperature Indices [26] | 22 Benzenoid Hydrocarbons | Correlation with Enthalpy/Boiling Point | High correlation coefficients (R) | Strong predictive power for specific physicochemical properties |

FN*, M2*, HMN [21] |

Dominating David Derived Networks | QSPR/QSAR Correlation | Strong correlation with entropy & acentric factor | Computational efficiency & invariance to molecular rotation | |

| TDA | TopoLearn [23] | 12 Datasets, 25 Representations | Correlation of topology with model error | Established empirical connection | Predicts optimal representation for a dataset a priori |

| Topological Fusion [24] | BBBP, BACE, ClinTox, MUV | Classification Accuracy | Outperformed SOTA by 1.2-3.0% | Integrates multi-scale local & global structural info | |

| Topological Fusion [24] | FreeSolv, Lipo, QM7 | Regression RMSE | Improved on SOTA (e.g., 0.048 on FreeSolv) | Integrates multi-scale local & global structural info | |

| Sequence-Based | Transformer-based (Uni-Mol) [24] | Various 3D Tasks | Accuracy | Significant success | Learns long-range, global atom-to-atom interactions |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The quantitative findings presented in Table 1 are derived from rigorous experimental protocols standardized across computational chemistry research. Key methodological elements include:

- Benchmark Datasets: Studies consistently use publicly available, curated datasets from sources like MoleculeNet [25] [18]. These cover diverse prediction tasks including quantum mechanics (e.g., QM7), physical chemistry (e.g., ESOL, Lipophilicity), and biophysics (e.g., BACE, BBBP) [18].

- Evaluation Metrics: For regression tasks (e.g., predicting energy or solubility), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is the standard metric [18]. For classification tasks (e.g., toxicity or activity prediction), Accuracy and Area Under the Curve (AUC) are commonly reported [24].

- Validation Frameworks: To ensure generalizability and avoid overfitting, studies employ rigorous data-splitting strategies, such as scaffold splitting, which separates molecules with distinct core structures, thereby testing the model's ability to generalize to truly novel chemotypes [23].

- Topological Index Calculation: For TIs, the process involves: (1) Representing the molecule as a molecular graph; (2) Calculating the degree of each vertex (atom); (3) Applying the specific formula of the index (e.g.,

FN* = Σ [η(u)² + η(v)²]across all edges) based on edge partitions [21]. - TDA Feature Extraction: For TDA-based methods like TopoLearn, the workflow involves: (1) Mapping molecules into a numerical feature space using a chosen representation; (2) Applying persistent homology to this point cloud to compute topological descriptors (e.g., Betti numbers, persistence diagrams); (3) Using these topological features to build a model that predicts the likely performance of the original representation [23].

Workflow and Strategic Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a molecular representation strategy based on project-specific constraints and objectives, particularly within a transfer learning context.

Diagram: Decision Workflow for Selecting Molecular Representation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Representation

| Category | Tool / Solution Name | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Representation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software & Libraries | RDKit [18] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit; generates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and 2D/3D coordinates. | Foundational for generating traditional descriptors and fingerprints; used in pre-processing for graph-based and sequence-based models. |

| TopoLearn [23] | A predictive model that uses TDA to evaluate and select the most effective molecular representation for a given dataset. | Core implementation for TDA-based representation selection, guiding strategic choice before model training. | |

| Uni-Mol [24] | A transformer-based framework for 3D molecular property prediction that learns global atom-to-atom interactions. | SOTA example of a 3D-aware, sequence-based representation model. | |

| MPNN [18] | Message Passing Neural Network; a foundational GNN architecture for molecular graphs. | A standard and widely used GNN strategy, often used as a baseline in benchmark studies. | |

| Computational Descriptors | Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) [17] | Circular fingerprints encoding molecular substructures around each atom up to a specified diameter. | A robust traditional representation; often used as a baseline or input for hybrid models (e.g., FP-BERT). |

| Parametric Temperature Indices [26] | Graph-theoretic descriptors (T_1^α, T_2^α) optimized to predict thermodynamic properties. |

Specialized TIs with proven high correlation for properties like enthalpy and boiling point in drug discovery. | |

| Methodological Frameworks | Consistency Regularization (CRGNN) [25] | A training methodology that uses augmentation anchoring to improve GNN performance on small datasets. | A crucial framework for applying GNNs in data-scarce transfer learning scenarios. |

| Topological Fusion [24] | A network architecture that integrates atom-level features with TDA-derived substructure features (bonds, functional groups). | An advanced hybrid strategy that combines the strengths of GNNs and TDA for superior performance on 3D tasks. |

The comparative analysis reveals that no single molecular representation strategy is universally superior; each occupies a distinct niche within the transfer learning ecosystem. Graph Networks, particularly advanced variants like Mol-GDL, KA-GNN, and CRGNN, offer powerful, end-to-end learning and are the default choice for complex property prediction when sufficient data is available or for transfer learning from large pre-trained models [20] [19] [25]. Topological Indices provide unparalleled computational efficiency and interpretability, making them ideal for rapid screening, QSPR modeling on small datasets, and applications where mechanistic insight is paramount [21] [26].

Emerging strategies like Topological Data Analysis and Topological Fusion models represent a paradigm shift, moving from using a single representation to proactively selecting or constructing the most informative one [23] [24]. For researchers engaged in transfer learning, the strategic imperative is to align the representation choice with the data context and project goals. TDA can guide the initial selection, TIs offer a fast, interpretable baseline, GNNs provide powerful learned representations, and hybrid fusion models currently deliver the highest predictive accuracy for challenging 3D molecular property prediction tasks.

Implementation Strategies and Real-World Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Graph Neural Network Architectures for Molecular Property Prediction

The accurate prediction of molecular properties is a critical challenge in drug discovery and materials science. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful framework for this task, as they naturally operate on molecular graphs where atoms represent nodes and chemical bonds represent edges. Unlike traditional machine learning methods that rely on hand-crafted molecular descriptors or fingerprints, GNNs can learn directly from molecular structure, capturing complex topological patterns and atomic interactions [27]. This capability is particularly valuable within transfer learning paradigms, where knowledge gained from large, computationally-generated datasets is adapted to predict real-world experimental properties, effectively addressing the scarcity of experimental data in chemistry research [1] [5].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art GNN architectures, evaluating their performance, design philosophies, and applicability within different transfer learning strategies for molecular property prediction.

Comparative Analysis of GNN Architectures

Advanced GNN architectures have evolved to overcome specific limitations in molecular graph processing, such as capturing long-range dependencies, integrating 3D geometric information, and improving parameter efficiency. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of several key architectures.

Table 1: Key GNN Architectures for Molecular Property Prediction

| Architecture | Core Innovation | Strengths | Ideal Property Types | Key Performance Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA-GNN [20] | Integrates Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) with Fourier-series-based functions into GNN components. | High parameter efficiency, improved interpretability, strong approximation capabilities. | General-purpose prediction, especially with limited data. | Consistently outperforms conventional GNNs in accuracy and efficiency across seven molecular benchmarks. |

| EGNN (Equivariant GNN) [28] | Incorporates 3D molecular coordinates and preserves E(n) equivariance (translation, rotation, reflection). | Captures geometry-sensitive properties and quantum chemical interactions. | Geometry-sensitive properties (e.g., partition coefficients log Kaw and log Kd). | Achieved MAE of 0.25 on log Kaw and 0.22 on log Kd [28]. |

| Graphormer [28] | Adapts the Transformer architecture for graphs using global attention mechanisms. | Captures long-range dependencies without explicit 3D information; highly scalable. | Properties requiring global graph reasoning (e.g., bioactivity). | ROC-AUC of 0.807 on OGB-MolHIV; MAE of 0.18 on log Kow [28]. |

| MolPath [29] | Chain-aware architecture that learns representations along shortest paths between nodes. | Effectively captures long-range dependencies in chain-like molecular backbones; mitigates over-squashing. | Molecular graphs with low clustering coefficients and dominant chains. | Outperformed strong baselines on regression (ESOL, FreeSolv) and classification (BACE, BBBP) tasks [29]. |

| GIN (Graph Isomorphism Network) [28] | Uses powerful aggregation functions with theoretical guarantees based on the Weisfeiler-Lehman test. | Excels at capturing local graph substructures and topological information. | 2D topological properties and local functional groups. | Serves as a strong 2D baseline model in comparative studies [28]. |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Empirical evaluations on standardized datasets are crucial for comparing architectural performance. The following table consolidates key metrics reported across multiple studies for common benchmark tasks.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking on Molecular Property Prediction Tasks (Lower is better for MAE/RMSE; Higher is better for ROC-AUC)

| Model | ESOL (RMSE) | FreeSolv (RMSE) | Lipophilicity (RMSE) | BACE (ROC-AUC) | OGB-MolHIV (ROC-AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPNN & Variants [18] | Among the best performers on small-molecule datasets | - | - | - | - |

| TChemGNN [18] | - | - | - | - | - |

| Graphormer [28] | - | - | - | - | 0.807 |

| 3D-Infomax [29] | - | - | - | 0.806 | - |

| HiMol [29] | - | - | - | 0.858 | - |

| MolPath [29] | Outperformed baselines | Outperformed baselines | Outperformed baselines | 0.870 | - |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, researchers typically adhere to a common experimental workflow. The diagram below outlines this standard protocol for training and evaluating GNN models on molecular property prediction tasks.

Key Methodological Steps:

- Dataset Preprocessing: Molecular Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings are converted into graph representations

G = (V, E), whereVis the set of atoms (nodes) andEis the set of bonds (edges) [28] [27]. Standardized splits (e.g., 80/10/10 for training/validation/test) are applied, often following benchmarks from MoleculeNet [18] [29]. - Feature Initialization: Node features (

h_v^0) are typically one-hot encodings of atom properties (e.g., element type, degree, hybridization). Edge features (e_vw) represent bond characteristics (e.g., type, conjugation, stereochemistry) [27]. - Model Training: The core of a GNN is the Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) framework [27]. For

Klayers, each node's representation is updated by aggregating messages from its neighbors, as defined by:- Message Passing:

m_v^(t+1) = Σ_(w∈N(v)) M_t(h_v^t, h_w^t, e_vw) - Node Update:

h_v^(t+1) = U_t(h_v^t, m_v^(t+1)) - Readout/Pooling: After

Klayers, a graph-level representationy = R({h_v^K | v ∈ G})is generated for the final property prediction [27]. Models are trained by minimizing the error between predicted and actual properties using optimizers like RMSprop [18].

- Message Passing:

- Evaluation: Performance is assessed on held-out test sets using task-appropriate metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression, and Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under Curve (ROC-AUC) for classification [28] [29].

Specialized Architectural Workflows

Different architectures introduce specific modifications to the standard MPNN framework. The workflow for KA-GNNs, for instance, systematically integrates novel KAN modules, while transfer learning approaches leverage data from multiple sources.

3.2.1 KA-GNN Workflow

Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs) replace standard Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) in GNNs with Fourier-based KAN layers, which use learnable univariate functions (based on Fourier series) on edges instead of fixed activation functions on nodes [20]. This integration happens across three core components, as shown below.

3.2.2 Transfer Learning with GNNs

Transfer learning is a key strategy to overcome data scarcity in experimental chemistry. The "Simulation-to-Real" (Sim2Real) paradigm uses large, inexpensive computational datasets (e.g., from Density Functional Theory) as a source domain, which is then adapted to predict real-world experimental properties (target domain) [1]. The process often involves a chemistry-informed domain transformation to bridge the gap between computational and experimental data spaces [1].

An alternative transfer learning approach involves pretraining GNNs on custom-tailored virtual molecular databases. These databases are constructed using systematic fragment combination or molecular generators guided by reinforcement learning [5]. The model is pretrained to predict easily computable molecular topological indices (e.g., Kappa2, BertzCT), which serve as a proxy task. The learned representations are then fine-tuned on a small dataset of real experimental catalytic activity data, significantly improving prediction performance with limited target data [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential software, datasets, and computational resources used in developing and evaluating GNNs for molecular property prediction.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Category | Tool / Resource | Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Libraries | RDKit [5] [18] | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for generating molecular graphs from SMILES, calculating molecular descriptors (e.g., topological indices), and computing fingerprints. |

| Software & Libraries | PyTor Geometric [27] | A specialized library built upon PyTorch that provides efficient implementations of many GNN layers and models, streamlining model development and training. |

| Benchmark Datasets | MoleculeNet [28] [18] [29] | A standardized benchmark collection encompassing multiple datasets (e.g., ESOL, FreeSolv, BACE, Tox21) for fair evaluation and comparison of ML models on molecular properties. |

| Benchmark Datasets | QM9, ZINC, OGB-MolHIV [28] | Specialized datasets: QM9 (quantum properties), ZINC (drug-like molecules), OGB-MolHIV (bioactivity classification), used for testing model performance on specific property types. |

| Computational Data | Virtual Molecular Databases [5] | Custom-generated databases of virtual molecules (e.g., built from donor, acceptor, and bridge fragments) used for transfer learning pretraining. |

| Computational Data | First-Principles Calculations [1] | Large-scale computational data (e.g., from Density Functional Theory) serving as the source domain in Sim2Real transfer learning to compensate for scarce experimental data. |

This guide objectively compares the performance and applications of PubChemQC against other prominent public chemical databases, framing the analysis within a broader thesis on source dataset strategies for transfer learning in chemistry research.

Comparative Analysis of Database Characteristics

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of key public chemical databases, highlighting their primary content and application focus.

Table 1: Key Public Chemical Databases for Research

| Database | Primary Content & Specialization | Reported Scale (as of 2024-2025) | Notable Features for Transfer Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [30] | Comprehensive small molecules & bioactivities; broad chemical information | 119 million compounds, 322 million substances, 295 million bioactivities [30] | Highly integrated; massive scale; diverse data sources (>1,000) [30] [31] |