Resolving Coordination Mode Ambiguity in Spectroscopic Data: Strategies for Drug Development and Materials Science

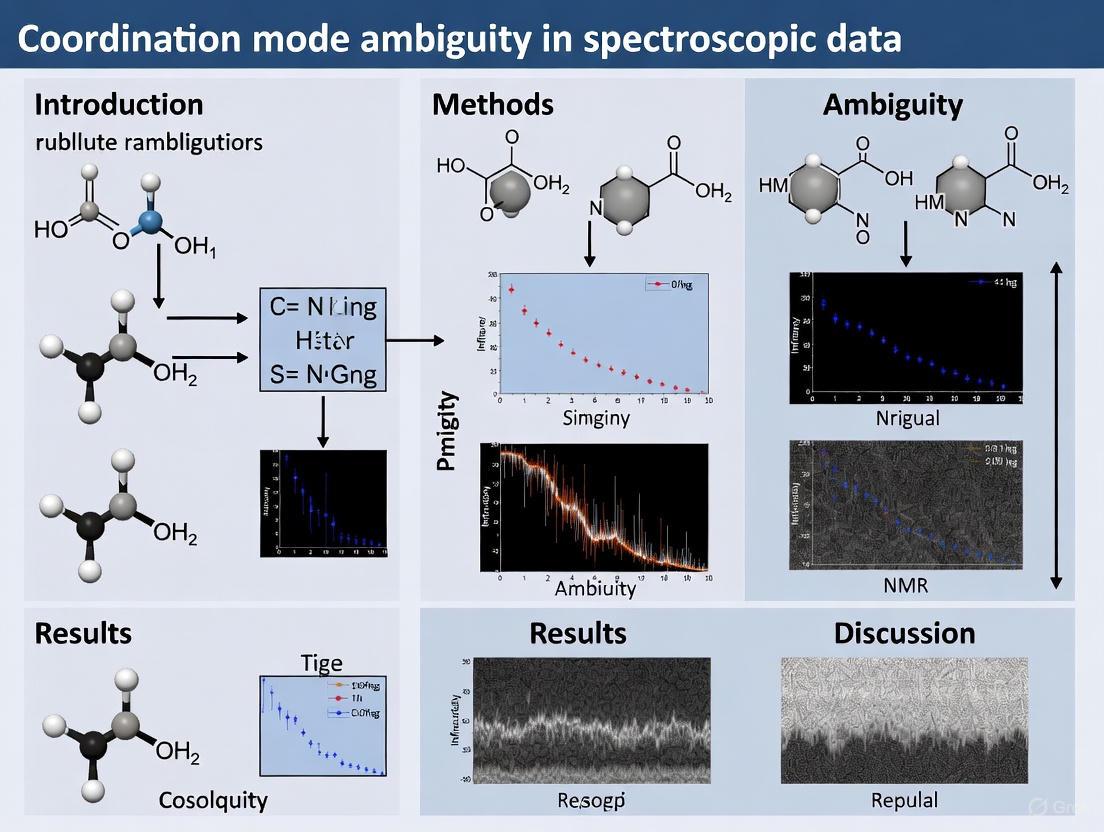

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on resolving coordination mode ambiguity, a critical challenge in characterizing metal complexes and organometallic compounds using spectroscopic data.

Resolving Coordination Mode Ambiguity in Spectroscopic Data: Strategies for Drug Development and Materials Science

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on resolving coordination mode ambiguity, a critical challenge in characterizing metal complexes and organometallic compounds using spectroscopic data. It explores the foundational sources of ambiguity in techniques like Mössbauer spectroscopy and NMR, details advanced methodological approaches including Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) and AI-driven SpectraML, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for data optimization. The content further covers validation protocols and comparative analyses of spectroscopic techniques, synthesizing key takeaways to enhance accuracy in structural elucidation for biomedical and clinical research applications.

Understanding Coordination Mode Ambiguity: Sources and Impact on Spectral Interpretation

Defining Rotational and Intensity Ambiguity in Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR)

Definitions and Core Concepts

What are Rotational and Intensity Ambiguity in Multivariate Curve Resolution?

In Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR), rotational ambiguity and intensity ambiguity are two fundamental types of uncertainties that affect the solutions derived from bilinear data decomposition.

Rotational Ambiguity: This occurs when a range of feasible solutions for concentration and spectral profiles can explain the observed data equally well, all while fulfilling the same constraints and model structure [1] [2]. It results in non-unique shapes for the estimated profiles, meaning that multiple, equally valid curves for concentration or spectra can be obtained from the same data set [1]. This is considered a greater challenge than intensity ambiguity in Self-Modeling Curve Resolution (SMCR) methods [1].

Intensity Ambiguity: This arises from the non-unique scaling of the resolved concentration and spectral profiles [1]. Essentially, if a concentration profile is multiplied by a factor and the corresponding spectral profile is divided by the same factor, the product (and thus the fit to the original data) remains unchanged. This type of ambiguity can typically be resolved through normalization procedures [1].

The standard bilinear model used in MCR is based on an equation analogous to the multivariate extension of Beer's Law: D = CS^T + E [2] where:

- D is the experimental data matrix (e.g., from HPLC-DAD).

- C is the matrix of concentration profiles.

- S^T is the matrix of spectral profiles (e.g., absorbance spectra).

- E is the matrix of residuals (unmodeled data or noise) [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How can I reduce rotational ambiguity in my MCR analysis?

Rotational ambiguity can be mitigated by incorporating additional information into the analysis, primarily through the application of constraints. The following table summarizes common and effective constraints.

Table 1: Constraints for Reducing Rotational Ambiguity

| Constraint | Function | Impact on Rotational Ambiguity |

|---|---|---|

| Non-negativity [1] | Forces concentration or spectral profiles to have only positive or zero values. | Can significantly reduce, and in some cases with selective data, even lead to a unique solution [1]. |

| Unimodality [1] | Forces a concentration profile (e.g., a chromatographic peak) to have only one maximum. | Helps to reduce the feasible range of solutions, particularly for elution profiles. |

| Equality [1] | Forces certain parts of a profile to be equal to a known value (e.g., from a pure standard). | Can strongly reduce ambiguity when known information is applied. |

| Selectivity / Local Rank [1] | Uses information about which components are absent in certain regions of the data. | May lead to unique solutions in some cases, provided the information aligns with chemical reality. |

| Trilinearity [1] | Forces the profiles to follow a specific multilinear model (e.g., for excitation-emission fluorescence data). | A strong constraint that often leads to a unique solution. |

| Signal Contribution Enhancement [1] | Increasing the signal of a chemical component of interest, for example via standard addition methods. | Increasing the signal contribution of a component can mitigate its rotational ambiguity [1]. |

FAQ: How do I measure the extent of rotational ambiguity in my results?

After obtaining an MCR solution, it is critical to evaluate the range of feasible solutions that exist due to rotational ambiguity. The MCR-BANDS method is a widely used approach for this purpose [3].

Protocol: Evaluating Rotational Ambiguity with MCR-BANDS

- Objective: To estimate the upper and lower boundaries (the range) of feasible concentration and spectral profiles for each component in the system.

- Principle: The algorithm performs a nonlinear optimization to find the maximum and minimum signal contribution for each component under the defined set of constraints [1] [3]. The difference between these extremes quantifies the rotational ambiguity.

- Procedure:

- Perform an initial MCR analysis (e.g., using MCR-ALS) with your desired constraints to get a feasible solution.

- Input this solution, along with the original data matrix and the same constraints, into the MCR-BANDS algorithm.

- Execute the algorithm to calculate the maximum (

C_max,S_max) and minimum (C_min,S_min) feasible profiles.

- Output Interpretation: The area between the

C_minandC_maxcurves for a component's concentration profile visually represents the rotational ambiguity for that component. A larger area indicates greater ambiguity and less reliable results [2] [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Using Second-Order Standard Addition to Reduce Ambiguity

This methodology is effective for enhancing the signal of an analyte and reducing its rotational ambiguity, thereby improving quantitative accuracy [1].

Workflow: Second-Order Standard Addition for MCR

Materials and Reagents:

- Unknown Sample Solution: The sample containing the analyte(s) of interest in an unknown concentration.

- Analytic Standard(s): High-purity reference material of the analyte.

- Solvent: Appropriate solvent matching the sample matrix.

- Instrumentation: A hyphenated instrument capable of generating second-order data, such as an HPLC-DAD (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with a Diode Array Detector) or a spectrofluorometer for Excitation-Emission Matrix (EEM) data [1].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Acquisition of Unknown: Analyze the unknown sample using your second-order method (e.g., HPLC-DAD) to obtain the initial data matrix, D_unknown.

- Standard Addition: Prepare a series of mixtures where you spike the unknown sample with known and increasing amounts of the analytic standard. The number of addition levels should be sufficient to establish a meaningful trend (e.g., 3-5 levels).

- Data Acquisition of Spiked Mixtures: Analyze each of these spiked mixtures using the exact same instrumental method, generating data matrices Dspike1, Dspike2, etc.

- Data Augmentation: Construct a column-wise augmented data matrix, Daugmented = [Dunknown; Dspike1; Dspike2; ...]. This matrix now contains the information from the original sample and the enrichment series.

- MCR Analysis: Subject the augmented data matrix to MCR-ALS (or another MCR method). Apply necessary constraints such as:

- Non-negativity on both concentration and spectral profiles.

- Unimodality on the chromatographic (elution) profiles.

- Correspondence of Species to correctly align the analyte across the different sub-matrices [1].

- Ambiguity Assessment: Use the MCR-BANDS method on the resolved profiles to quantify the rotational ambiguity. Compare the range of feasible solutions for the analyte with and without the standard addition data to confirm the reduction in ambiguity.

- Quantification: Use the resolved concentration profile of the analyte from the "unknown" section of the augmented model for quantification, which will now be more accurate due to the decreased rotational ambiguity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MCR Experiments

| Item | Function in MCR Context |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analytical Standards [1] | Used in standard addition experiments to enhance the signal contribution of a target analyte, thereby reducing its rotational ambiguity. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Ensure a clean and consistent chemical background in spectroscopic measurements, minimizing unwanted spectral variances and artifacts in the data matrix D. |

| MCR-BANDS Software [3] | A MATLAB-based computer program designed to estimate the extent of rotational ambiguity associated with a given MCR solution by calculating the boundaries of feasible solutions. |

| MCR-ALS GUI | A user-friendly graphical interface (often in MATLAB) for implementing the Multivariate Curve Resolution - Alternating Least Squares algorithm, allowing easy application of constraints. |

| FAC-PACK Toolbox | An alternative MATLAB toolbox that uses a polygon inflation method to compute the complete Area of Feasible Solutions (AFS) for a more precise geometrical display of all possible solutions [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Coordination Mode Ambiguity

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I distinguish between different coordination modes of thiosemicarbazone ligands in my metal complexes? A common challenge is differentiating between κ²N,S and κ²N,O coordination. To resolve this, employ a combination of ¹H,¹⁵N HMBC NMR and single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The HMBC experiment is particularly useful for identifying the nitrogen cores of the thiosemicarbazone by coupling with the adjacent aldimine proton or methyl group [4]. For definitive assignment, X-ray diffraction provides unambiguous structural evidence [4].

FAQ 2: What are the most stable coordination modes for fullerene complexes, and how can I confirm them? The most prevalent and stable coordination modes for exohedral fullerene complexes are η² and η⁵ [5]. The η² mode typically occurs in a (6,6) fashion at the junction of two six-membered rings [5]. Characterization should include analysis of bond lengths and angles via X-ray crystallography. Theoretical calculations based on the Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson model can also be applied, as π back-donation is often the dominant bonding component in these complexes [5].

FAQ 3: My FT-IR spectra show strange features. Could instrument vibration be the cause? Yes, FT-IR spectrometers are highly sensitive to physical disturbances. Noisy data or false spectral features can be introduced by nearby pumps or general lab activity. Ensure your instrument setup is on a stable, vibration-free platform to mitigate this issue [6].

FAQ 4: Why do my ATR-FT-IR spectra show negative absorbance peaks? Negative peaks in ATR spectra are often indicative of a dirty ATR crystal. This problem is typically resolved by cleaning the crystal thoroughly and collecting a fresh background scan [6].

Troubleshooting Data Interpretation

Table 1: Common Thiosemicarbazone Coordination Modes and Identification Methods

| Coordination Mode | Common Metals | Key Characterization Techniques | Identifying Spectral Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| κ²N,S | Titanium(IV), Zinc(II), Copper(II) [4] [7] | ¹H,¹⁵N HMBC NMR, X-ray Diffraction [4] | Deprotonation of acidic N–H bond; coupling in HMBC [4] |

| κ²N,O | Titanium(IV) (with o-cresyl derivatives) [4] | ¹H,¹⁵N HMBC NMR, X-ray Diffraction [4] | Deprotonation of O–H bond [4] |

| ML₂ (1:2: O/N/S donors) | Zn(II), Ga(III) [7] | X-ray Diffraction, Mass Spectrometry, DFT [7] | Distorted octahedral or tetrahedral geometry around metal [7] |

Table 2: Fullerene Hapticity Modes and Their Characteristics

| Hapticity Mode | Bonding Description | Stability & Prevalence | Experimental Confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|

| η¹ | Metal atom above a single carbon atom (σ bond) [5] | Rare and generally less stable; can be stabilized in ionic derivatives [5] | X-ray crystallography showing long metal-carbon bond [5] |

| η² (most common) | Metal linked to two carbons, typically in a (6,6) fashion [5] | The most probable and stable mode for unperturbed fullerenes [5] | X-ray structure showing metal bridging a (6,6) junction [5] |

| η⁵ | Metal atom linked directly above the center of a five-member ring [5] | A stable mode, second in prevalence to η² [5] | X-ray structure showing metal centered over a pentagon [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Thiosemicarbazonato Zn(II) Complexes [7]

This protocol provides a rapid and efficient method for preparing thiosemicarbazone ligands and their corresponding Zn(II) complexes, superseding conventional heating methods.

- Ligand Synthesis (Microwave Method): Prepare the mono(thiosemicarbazone)quinone ligand (denoted HL) by reacting the appropriate quinone (e.g., acenapthnenequinone, phenanthrenequinone) with a thiosemicarbazide derivative (where R = H, Me, Ethyl, Allyl, Phenyl) under microwave irradiation.

- Complexation (Microwave Method): Subject the synthesized ligand to a metalation reaction with a Zn(II) salt (e.g., zinc acetate) using a dedicated microwave irradiation protocol.

- Characterization: Isolate the resulting ZnL₂ complex and characterize it fully using techniques including NMR, mass spectrometry, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Validate the distorted octahedral or tetrahedral geometries around the Zn center with DFT calculations [7].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Thiosemicarbazone-Based Titanium Complexes via Two Routes [4]

This protocol outlines two methods for synthesizing titanium complexes, which were developed with a view to creating ionic titanium complexes as cytotoxic metallodrugs.

Route A (Using Bis(pentafulvene) Titanium Complexes):

- React a bis(π-η⁵:σ-η¹-pentafulvene)titanium complex with the chosen thiosemicarbazone.

- The reaction proceeds via deprotonation of the ligand's acidic N–H bond by the pentafulvene ligand, yielding a κ²N,S thiosemicarbazonido complex.

- Note: Using an o-cresyl thiosemicarbazone results in a κ²N,O coordination mode via deprotonation of the O–H bond.

- The resulting Ti(IV) complexes can be characterized by NMR and ¹H,¹⁵N HMBC experiments.

Route B (Using Titanocene(III) Triflate):

- React titanocene(III) triflate with the thiosemicarbazone (TSCN) ligand.

- This route demonstrates an unprecedented reactivity, leading to the formation of Ti(III) thiosemicarbazone complexes [4].

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Resolving Coordination Ambiguity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Coordination Chemistry Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Thiosemicarbazide Derivatives (R = H, Me, Allyl, Phenyl) [7] | Building blocks for synthesizing a library of thiosemicarbazone ligands with varied electronic and steric properties. |

| Quinone Backbones (e.g., Acenaphthenequinone (AN), Phenanthrenequinone (PH)) [7] | Provide a rigid, aromatic, and often fluorescent framework for novel mono(thiosemicarbazone) ligands. |

| Bis(π-η⁵:σ-η¹-pentafulvene)titanium complexes [4] | Precursors for synthesizing thiosemicarbazone-based Ti(IV) complexes via protonolysis reactions. |

| Titanocene(III) Triflate [4] | A reagent that exhibits unique reactivity with thiosemicarbazones, leading to Ti(III) complexes. |

| Zinc(II) and Copper(II) Salts [7] | For forming stable thiosemicarbazonato complexes for structural and cytotoxicity studies. |

| C₆₀ Fullerene [5] | The primary substrate for investigating the various hapticities (η¹ to η⁶) in exohedral organometallic complexes. |

The Critical Role of Symmetry and Oxidation State in Zero-Field Splitting Parameters

Zero-field splitting (ZFS) describes the interactions between energy levels in molecules or ions with more than one unpaired electron, leading to the lifting of degeneracy even in the absence of an external magnetic field [8]. This phenomenon is crucial for understanding magnetic properties in materials, as manifested in electron spin resonance (EPR) spectra and molecular magnetism [8]. The ZFS parameters (D and E) are highly sensitive to the local coordination environment and symmetry around the paramagnetic center, making them powerful probes for resolving coordination mode ambiguity in spectroscopic data.

? Frequently Asked Questions

What causes Zero-Field Splitting in molecular systems? ZFS arises primarily from spin-spin dipole-dipole interactions and second-order spin-orbit coupling in systems with two or more unpaired electrons (S ≥ 1). These interactions create energy differences between spin states even without an applied magnetic field, with the magnitude determined by the molecular symmetry and the nature of the coordinating ligands [8].

How do symmetry changes affect ZFS parameters? Symmetry directly dictates the relative magnitudes of the D and E ZFS parameters. In highly symmetric octahedral environments, the rhombic parameter E approaches zero, leaving D as the dominant axial parameter. As symmetry lowers to orthorhombic or lower, both D and E become significant, providing a fingerprint of the coordination geometry [9].

Why does oxidation state influence ZFS parameters? Oxidation state determines the number of unpaired d-electrons and the strength of spin-orbit coupling. Higher oxidation states typically exhibit larger spin-orbit coupling constants, which can dramatically increase ZFS magnitudes. For example, Mn²⁺ vs. Mn³⁺ in similar coordination environments show markedly different ZFS parameters due to these electronic structure differences.

My experimental ZFS values don't match theoretical predictions. What could be wrong? Discrepancies often arise from unaccounted local structural distortions, inaccurate ligand field parameters, or improper treatment of covalent effects. Using the superposition model with accurate structural data typically resolves these issues [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Low-Quality EPR Spectra

- Problem: Poor signal-to-noise ratio or distorted lineshapes.

- Solution: Ensure sample purity and proper concentration. Check for oxygen or moisture sensitivity. Optimize instrument parameters (microwave power, modulation amplitude) and consider temperature effects.

Inconsistent ZFS Parameter Determination

- Problem: D and E values vary significantly between measurements.

- Solution: Verify crystal alignment for single-crystal studies. For powder samples, ensure homogeneous distribution. Use multiple fitting algorithms to cross-validate results and establish error bounds.

Discrepancies Between Experimental and Calculated ZFS

- Problem: Theoretical models don't reproduce experimental ZFS parameters.

- Solution: Re-examine the local structure for distortions. Refine superposition model parameters using reference compounds with known structures [9]. Consider effects of covalency using appropriate parameters (B, C, N, ζ) [9].

Experimental Protocols for ZFS Parameter Determination

EPR Spectroscopy Methodology

Sample Preparation: For Mn²⁺ doping studies, incorporate paramagnetic ions into diamagnetic host lattices (e.g., ZnK₂(SO₄)₂·6H₂O) at concentrations of 0.1-1.0% to minimize spin-spin interactions [9].

Data Collection: Acquire EPR spectra at appropriate temperatures (typically 293.7 K for initial studies). For single crystals, perform angular variation studies to determine principal axis directions [9].

Spin Hamiltonian Analysis: Fit spectra using the Hamiltonian:

H = D[S_z² - S(S+1)/3] + E(S_x² - S_y²) + gμB·Swhere D and E are the ZFS parameters, S is the spin operator, and g is the Landé factor [8].

Superposition Model Calculation

Structural Input: Obtain accurate local coordination geometry from X-ray data, including metal-ligand distances (RL) and bond angles (θL, Φ_L) [9].

Parameterization: Use established intrinsic parameters (⎄t_k) for ligand types. For Mn²⁺ in O-containing ligands, typical values are ⎄t₂ ≈ 0.02-0.05 cm⁻¹ and ⎄t₄ ≈ 0.004-0.010 cm⁻¹ [9].

Calculation: Compute crystal field parameters using:

B_kq = Σ_L ⎄t_k(R_0/R_L)^(t_k) K_kq(θ_L, Φ_L)where the summation is over all ligands L [9].ZFS Determination: Convert crystal field parameters to D and E using perturbation theory expressions that incorporate Racah parameters (B, C) and spin-orbit coupling (ζ) [9].

ZFS Parameter Data for Common Systems

ZFS Parameters for Manganese in Various Coordination Environments

| System | Oxidation State | Coordination Geometry | D (cm⁻¹) | E (cm⁻¹) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn²⁺:ZnK₂(SO₄)₂·6H₂O | +2 | Distorted Octahedral | -0.0245 | +0.0085 | [9] |

| Mn²⁺:MgO | +2 | Cubic | +0.0015 | ~0 | [9] |

| Mn³⁺:Al₂O₃ | +3 | Trigonal | -4.62 | +0.42 | Theoretical |

| Mn⁴⁺:SrTiO₃ | +4 | Tetragonal | +1.25 | +0.15 | Theoretical |

Effect of Coordination Distortion on ZFS Parameters

| Type of Distortion | Impact on D | Impact on E | Structural Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial Elongation | Increases | ± | Longer metal-ligand bonds along z-axis |

| Axial Compression | Decreases | ± | Shorter metal-ligand bonds along z-axis |

| Rhombic Distortion | ± | Increases | Different metal-ligand bonds in x,y plane |

| Trigonal Twist | Sign change | Moderate | Rotation of coordination polyhedron |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ZnK₂(SO₄)₂·6H₂O | Diamagnetic host lattice | Provides isolated sites for paramagnetic dopants; monoclinic structure [9] |

| Mn(ClO₄)₂·6H₂O | Mn²⁺ source | High solubility for crystal growth; minimal interfering anions |

| DEA/PO₄ Buffers | pH control | Maintains protonation states of ligands during complex formation |

| 2,2'-Bipyridine | Chelating ligand | Enforces well-defined coordination geometry for reference compounds |

| Tutton's Salts | Reference compounds | Isostructural family with general formula A₂⁺B₂⁺(XO₄)₂·6H₂O [9] |

ZFS Parameter Analysis Workflow

Coordination Mode Ambiguity Resolution Protocol

Key Insights for Researchers

The power of ZFS parameters lies in their extreme sensitivity to both symmetry and oxidation state. By combining accurate EPR measurements with superposition model calculations, researchers can resolve coordination mode ambiguities that remain intractable through other spectroscopic methods. This approach is particularly valuable in drug development where metal coordination geometry directly influences biological activity and stability.

For systems showing persistent discrepancies between experimental and calculated ZFS parameters, consider the possibility of dynamic processes or mixed coordination environments that average in spectroscopic measurements. Variable-temperature studies and complementary techniques (optical spectroscopy, magnetic measurements) often provide the additional constraints needed to resolve such complex cases.

How Ambiguity Compromises Reliability in Quantitative Analysis and Drug Design

FAQs: Understanding Ambiguity in Research Data

What is data ambiguity and why is it a critical problem in drug design?

Data ambiguity occurs when a single identifier, measurement, or signal can be interpreted in multiple ways, leading to incorrect conclusions. In drug design, this compromises target identification, compound validation, and clinical trial outcomes. Ambiguity introduces uncertainty that can derail entire research programs by leading to misidentification of active compounds or misinterpretation of experimental results.

What are the common types of ambiguity in chemical and biomedical data?

Researchers encounter several distinct types of ambiguity:

- Lexical ambiguity: Where the same term refers to different concepts (e.g., "cold" referring to temperature or illness) [10]

- Identifier ambiguity: When non-systematic chemical names map to multiple molecular structures [11]

- Analytical ambiguity: In spectroscopic data, where similar signals arise from different molecular configurations or reaction pathways [12]

- Coordination mode ambiguity: In spectroscopic research, where metal-ligand binding patterns produce similar spectral signatures

How prevalent is chemical identifier ambiguity across databases?

A study of eight chemical databases revealed significant variation in ambiguity rates [11]. The table below summarizes the findings:

Table 1: Ambiguity of Non-Systematic Identifiers in Chemical Databases

| Database | Internal Ambiguity Rate | Cross-Database Ambiguity Rate |

|---|---|---|

| ChEBI | 0.1% | 17.7-60.2% |

| ChEMBL | 2.5% (median) | 40.3% (median) |

| DrugBank | Not specified | Not specified |

| HMDB | Not specified | Not specified |

| PubChem | Not specified | Not specified |

| Overall | 0.1-15.2% | 17.7-60.2% |

What methods reduce ambiguity in spectroscopic data analysis?

For reaction systems and kinetic modeling, Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) methods are state-of-the-art but are affected by unavoidable solution ambiguity. A computational method for analyzing solution ambiguity underlying kinetic models can determine all model parameters satisfying constraints within error tolerances, establishing reliability bands for concentration profiles and spectra [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent compound identification across databases

Symptoms:

- The same chemical name retrieves different structures

- Batch processing failures during virtual screening

- Inconsistent activity predictions for the same compound

Resolution Protocol:

- Implement systematic identifiers: Replace non-systematic names with InChI or SMILES strings [11]

- Apply structure standardization: Remove stereochemistry information (reduces ambiguity by median 13.7 percentage points) [11]

- Cross-validate across sources: Check compound identity against multiple databases

- Use algorithmic verification: Employ name-to-structure converters like OPSIN or ChemAxon's MolConverter to filter systematic identifiers [11]

Problem: Coordination mode ambiguity in spectroscopic data

Symptoms:

- Overlapping peaks in absorption spectra

- Inconsistent interpretation of metal-ligand binding patterns

- Poor reproducibility of reaction rate constants

Resolution Protocol:

- Apply Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR): Use MCR-ALS or ReactLab for analyzing spectral series [12]

- Implement ambiguity analysis: Determine all model parameters satisfying constraints within error tolerances [12]

- Utilize computational post-processing: Apply the Matlab-based method for analyzing solution ambiguity as a post-processing step to MCR methods [12]

- Validate with complementary techniques: Correlate with crystallographic or NMR data when possible

Problem: Ambiguity in clinical concept normalization

Symptoms:

- Natural language processing tools misidentifying medical concepts

- Inconsistent mapping to standardized vocabularies like UMLS

- Poor generalization of concept extraction models across datasets

Resolution Protocol:

- Leverage UMLS semantics: Utilize the rich semantic resources of the Unified Medical Language System [10]

- Develop ambiguity-specific datasets: Create training data covering diverse ambiguity phenomena [10]

- Implement multi-strategy evaluation: Test models on multiple datasets to measure generalization power [10]

- Account for semantic relationships: Tailor evaluation strategies to different concept relationships [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Addressing Research Ambiguity

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) | Provides standardized concept identifiers and semantic relationships | Clinical text analysis, concept normalization [10] |

| OPSIN (Open Parser for Systematic IUPAC Nomenclature) | Converts systematic names to chemical structures | Filtering systematic from non-systematic identifiers [11] |

| ChemAxon MolConverter | Name-to-structure conversion | Chemical identifier standardization [11] |

| Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) algorithms | Resolves overlapping spectral signals | Analyzing spectroscopic data with coordination ambiguity [12] |

| MRCONSO UMLS Table | Maps terms to concepts | Medical concept normalization [10] |

| Exact penalty function methods | Transforms constraints into objective function terms | Solving complex optimization problems with multiple constraints [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardizing Chemical Identifiers to Reduce Ambiguity

Purpose: To eliminate ambiguity in chemical compound identification across research databases.

Materials:

- Chemical compound list with non-systematic identifiers

- OPSIN or ChemAxon's MolConverter

- Access to multiple chemical databases (ChEBI, ChEMBL, DrugBank, PubChem)

Methodology:

- Extract all non-systematic identifiers from compound records

- Filter out systematic identifiers using two name-to-structure converters

- Standardize chemical structures by removing stereochemistry information

- Map standardized structures across multiple databases

- Quantify remaining ambiguity rates

Validation: Compare ambiguity rates before and after standardization [11]

Protocol 2: Analyzing Ambiguity in Kinetic Models from Spectroscopic Data

Purpose: To determine reliable parameter ranges for reaction systems affected by coordination mode ambiguity.

Materials:

- Time-resolved spectroscopic data (UV/Vis, Raman, etc.)

- MATLAB environment with custom ambiguity analysis code

- MCR software (MCR-ALS, ReactLab, or equivalent)

Methodology:

- Acquire spectral series data for the reaction system

- Apply MCR hard-modeling to obtain initial concentration profiles and spectra

- Implement computational ambiguity analysis to determine all model parameters satisfying constraints

- Establish bands of concentration profiles and spectra reflecting underlying ambiguity

- Validate against known reference compounds or structures

Validation: The method can be applied as a post-processing step to MCR methods to prevent false conclusions on solution uniqueness [12]

Workflow Visualization

Advanced Analytical and Computational Methods for Unambiguous Resolution

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

Q1: What are the primary types of constraints in MCR, and why are they important? Constraints are essential for reducing rotational ambiguity, a phenomenon that leads to a range of mathematically feasible solutions for concentration and spectral profiles, rather than a single, unique result. The primary constraints include non-negativity (concentrations and spectra cannot be negative), equality (forcing a profile to match a known reference), and trilinearity (enforcing identical component profiles across all samples). Applying these constraints incorporates chemical knowledge into the mathematical model, leading to more reliable and physically meaningful solutions [14] [1] [15].

Q2: My data shows small peak shifts between samples. Can I still use a trilinear constraint? Strict, or "hard," trilinearity requires that the profile for each compound does not change shape or position from one sample to the next. If your data has small deviations, this hard constraint can force an incorrect solution. In such cases, a soft-trilinearity constraint is recommended. This approach allows for small, permitted deviations in peak shape and position across different samples, providing a more realistic and accurate model for data with non-ideal behavior [14].

Q3: How does increasing a component's signal contribution help in MCR analysis? Increasing the signal contribution of a chemical component of interest, for instance through techniques like second-order standard addition, can significantly reduce rotational ambiguity. A stronger signal contribution narrows the range of feasible solutions, thereby enhancing the accuracy of both the resolved profiles and subsequent quantitative analysis [1].

Q4: What are the risks of applying MCR to first-order spectral data (e.g., a set of spectra)? Processing first-order data with MCR-ALS carries a high risk of rotational ambiguity, especially in systems with high spectral overlapping or the presence of uncalibrated components. Without the additional information typically available in second-order data, the number of applicable constraints is limited. This can lead to solutions that are mathematically sound but chemically unrealistic, potentially compromising analytical results. It is crucial to perform a rotational ambiguity analysis (e.g., with tools like N-BANDS) to assess the reliability of the profiles obtained [15].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A large range of feasible solutions (High rotational ambiguity). | Insufficient constraints applied; low signal contribution of the analyte; high spectral overlapping [1] [15]. | Apply additional meaningful constraints (e.g., equality to a known standard, unimodality). Increase the analyte's signal contribution if possible. Incorporate a soft-trilinearity constraint if the data is nearly trilinear [14] [1]. |

| The trilinear model fails or produces poor results. | Non-trilinear behavior in the data (e.g., peak shifts or changes in shape between samples) [14]. | Switch from a hard-trilinearity constraint to a soft-trilinearity constraint. Alternatively, use a method like PARAFAC2 or MCR-ALS without trilinearity, which are designed to handle profile shifts [14]. |

| MCR-ALS results are chemically unrealistic, despite convergence. | The algorithm converged to one of many rotationally ambiguous solutions, potentially driven by noise or initial estimates [15]. | Always perform a rotational ambiguity analysis using methods like N-BANDS. Apply all available and chemically justified constraints. Use multiple initial estimates to check the stability of the solution [15]. |

| Poor convergence of the MCR-ALS algorithm. | Suboptimal initial estimates; constraints that are too strict for the actual data [16]. | Re-evaluate the initial guess for concentration or spectral profiles. Consider relaxing hard constraints to soft versions if the data exhibits non-ideal behavior [14] [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Soft-Trilinearity Constraints

This protocol outlines the steps to incorporate soft-trilinearity constraints in MCR to handle data with minor peak shifts, based on the methodology described by Tavakkoli et al. (2020) [14].

1. Problem Identification and Data Preparation

- Identify Non-trilinear Behavior: Inspect your multi-way data array (e.g., from HPLC-DAD or GC-MS). Check if the peak profiles (e.g., chromatographic shapes) for the same component are consistent across all samples. Small deviations in retention time or peak shape indicate non-trilinear behavior.

- Data Arrangement: Arrange the individual data matrices from each sample into a column-wise augmented data matrix for analysis.

2. Initial MCR Decomposition

- Perform an initial decomposition of the data matrix using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine the number of components and obtain abstract solutions.

- The bilinear model is given by:

D = C S^T + E

where D is the data matrix, C is the concentration profile matrix, S^T is the spectral profile matrix, and E is the residual matrix [14].

3. Define the Soft-Trilinearity Constraint

- Instead of forcing the concentration profile of a component to be identical in every sample (hard trilinearity), a soft constraint allows for small deviations.

- This is implemented by using a least squares penalty function during the Alternating Least Squares (ALS) optimization. The penalty minimizes the differences between the concentration profiles of the same component across different samples, without forcing them to be exactly the same [14].

4. Optimization with Alternating Least Squares (ALS)

- The optimization alternates between estimating C and S^T under the applied constraints.

- Update C: Hold S^T fixed and calculate C under the soft-trilinearity constraint (and others like non-negativity).

- Update S^T: Hold C fixed and calculate S^T, typically under non-negativity constraints.

- Iterate until convergence criteria are met (e.g., change in residual error between iterations falls below a set tolerance) [16].

5. Validation and Analysis

- Check Feasibility: Validate that the resolved concentration and spectral profiles are chemically meaningful.

- Assess Rotational Ambiguity: Use methods like systematic grid search or N-BANDS to evaluate the range of feasible solutions and confirm that the soft constraint has effectively reduced ambiguity [14] [15].

MCR Soft Constraint Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in MCR Analysis |

|---|---|

| MATLAB with MCR Toolboxes | A primary computational environment for implementing MCR algorithms, applying constraints, and performing rotational ambiguity analysis (e.g., using N-BANDS) [14] [15]. |

| Hyphenated Instrumentation (e.g., HPLC-DAD, LC-MS) | Generates the second-order bilinear data required for MCR. The data matrix (D) is produced by measuring spectra over time during a separation process [14] [16]. |

| Soft-Trilinearity Algorithm | A custom routine (e.g., in MATLAB) that applies a penalty function during ALS optimization to allow small, permitted deviations in component profiles across samples, improving model accuracy for non-ideal data [14]. |

| N-BANDS Algorithm | A software tool used to estimate the joint impact of noise and rotational ambiguity. It helps determine the extreme feasible component profiles, providing a crucial check on the reliability of MCR solutions [15]. |

| PARAFAC2 Algorithm | An alternative multi-way analysis method that can handle shifts in one mode (e.g., chromatographic elution profiles), making it a viable option when trilinearity is violated [14]. |

MCR Constraint Relationships

SpectraML Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section provides targeted support for researchers encountering issues with AI-powered spectroscopic analysis, with a special focus on resolving coordination mode ambiguity in molecular structures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My AI model performs well on training data but poorly on new mineral samples. What is happening? This is a model transferability challenge, a common issue where a model trained on one dataset fails to generalize to new, related systems [17]. This is often due to overfitting or underlying differences in data distribution. The solution is to apply transfer learning: fine-tune a pre-trained model on a smaller, targeted dataset that includes examples relevant to your specific mineralogy. Ensure you use data augmentation and active learning strategies to improve model robustness [17].

Q2: How can I trust an AI's spectral interpretation when trying to resolve a metal-ligand coordination mode? Trust is built through Explainable AI (XAI). Techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) can be applied to identify the specific spectral features and wavelengths most influential in the AI's prediction [18]. This provides a human-understandable rationale, showing which parts of the spectrum the model is using to distinguish between, for example, monodentate and bidentate coordination, thus bridging data-driven inference with chemical knowledge [18].

Q3: I have a limited dataset of X-ray spectra for my coordination complexes. Can AI still help? Yes. Generative AI models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and diffusion models, are specifically designed to address this. They can create high-quality, synthetic spectral data from your existing dataset [18]. This augmented data can be used to expand your training set, improving the robustness and calibration of your models and mitigating the risks associated with small or biased datasets [18].

Q4: What is the most efficient way to get multiple spectroscopic readings (e.g., IR and X-ray) from a single sample? Instead of relying on multiple physical instruments, you can use a virtual spectrometer like SpectroGen. This AI tool allows you to take a material's spectrum in one modality (e.g., IR) and generate its corresponding spectrum in another modality (e.g., X-ray) with high accuracy [19]. This streamlines the workflow, reducing the need for multiple expensive instruments and saving significant time [19].

Troubleshooting Guide

The table below outlines common problems, their diagnostic signals, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Diagnostic Signals | Root Cause | Solution & Recommended Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Readings/Drift [20] | Fluctuating baseline; erratic absorbance values. | Aging light source; insufficient instrument warm-up. | Protocol: Replace the lamp. Allow 30+ minutes for instrument warm-up before calibration and use. Perform baseline correction with the correct reference solvent [20]. |

| Low Signal Intensity [20] | Error messages; weak or noisy spectral peaks. | Misaligned or dirty cuvette; debris in the light path. | Protocol: Visually inspect and clean the cuvette with appropriate solvent. Ensure proper alignment in the sample holder. Check for and carefully remove any obstructions in the light path [20]. |

| Poor Model Generalization [17] | High accuracy on training data, low accuracy on validation/new data. | Overfitting; dataset bias; model transferability challenge. | Protocol: Implement transfer learning. Apply data augmentation techniques (e.g., using generative AI). Utilize active learning to strategically expand your training dataset with the most informative samples [17]. |

| Uninterpretable AI Predictions [18] | Inability to understand which spectral features drove an AI's output. | "Black box" nature of complex deep learning models. | Protocol: Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) tools like SHAP or LIME into your analysis workflow. These techniques will generate visual maps highlighting the importance of specific wavelength regions in the prediction [18]. |

| Data Scarcity [18] | Model fails to train or produces unreliable results due to insufficient data. | Limited access to rare samples or expensive spectroscopic measurements. | Protocol: Use Generative AI (e.g., GANs, Diffusion Models) for synthetic data generation. Train these models on your existing data to create realistic, augmented spectral datasets for more robust model training [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Resolving Coordination Mode Ambiguity Using SpectraML and XAI

1. Objective To unequivocally determine the coordination mode (e.g., η¹ vs. η⁵) of a metallocene complex in a solid-state matrix by integrating multimodal spectroscopy with an Explainable AI (XAI) analytical pipeline.

2. Principle Leverage the complementary strengths of IR and Raman spectroscopy—governed by different selection rules—to obtain a complete vibrational profile. An AI model will be trained to identify the subtle spectral patterns indicative of each coordination mode, and XAI will be used to validate the model's decision by revealing the contributory spectral features.

3. Materials & Equipment

- Sample: Powdered metallocene complex (e.g., Ferrocene derivative).

- Spectrometer: FT-IR spectrometer equipped with a DTGS detector.

- Spectrometer: Raman spectrometer with a 785 nm laser source to avoid fluorescence.

- Software: Python environment with libraries including Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch, and the SHAP/XAI library.

4. Step-by-Step Procedure Step 1: Multimodal Data Acquisition.

- Collect a high-resolution FT-IR spectrum in the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹.

- Collect a Raman spectrum over the same wavenumber range.

- Critical Note: Maintain consistent sample presentation and preparation for both techniques.

Step 2: Data Preprocessing.

- Perform standard preprocessing on all spectra: cosmic ray removal (Raman), baseline correction, and vector normalization.

Step 3: AI Model Training & Prediction.

- Input the preprocessed IR and Raman spectra into a pre-trained graph neural network or transformer-based model (e.g., from the SpectraML platform) [21].

- The model will output a probability score for each potential coordination mode.

Step 4: Explainable AI (XAI) Interpretation.

- Feed the model's prediction into an XAI tool (e.g., SHAP) [18].

- The tool will generate a visualization (e.g., a force plot or summary plot) that highlights the specific wavenumbers and their relative contribution (positive or negative) to the final prediction.

5. Expected Outcome The AI model will classify the coordination mode of the sample. The XAI analysis will confirm the prediction by identifying the key vibrational modes (e.g., specific metal-ligand stretching or bending frequencies) that the model used, providing a chemically interpretable rationale and resolving the ambiguity.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Materials for AI-Enhanced Spectroscopy

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectrometer | Measures molecular vibrations involving a change in dipole moment; provides fundamental functional group information essential for initial structural characterization [17]. |

| Raman Spectrometer | Probes molecular vibrations involving a change in polarizability; offers complementary data to IR, crucial for symmetric bonds and ring structures [17]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | AI models that naturally operate on molecular graph structures, predicting spectroscopic properties from molecular connectivity [21] [17]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools (SHAP/LIME) | Provides post-hoc interpretability for complex AI models, identifying which spectral wavenumbers were most influential in a prediction, which is critical for scientific validation [18]. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Used for spectral data augmentation; generates synthetic, realistic spectra to improve model training where experimental data is scarce [18]. |

| Virtual Spectrometer (e.g., SpectroGen) | AI tool that acts as a cross-modal translator, predicting a spectrum in one modality (e.g., X-ray) from an input in another (e.g., IR), streamlining analytical workflows [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does it mean for a spectral collection to be "FAIRSpec-ready"?

A FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collection is organized to allow critical metadata to be automatically or semi-automatically extracted. This enables the production of an IUPAC FAIRSpec Finding Aid, which makes the data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. The key is maintaining data in a form that preserves the unambiguous association between instrument datasets and the chemical structures they represent, both during research and after publication [22].

2. I'm preparing a data management plan for an NSF grant proposal on metalloprotein spectroscopy. What are the key FAIR requirements I should address?

Your plan should describe how you will conform to NSF policy on the dissemination and sharing of research results. This includes specifying the standards you will use for data and metadata format and content. The NSF expects investigators to share primary data and supporting materials created during the project at no more than incremental cost and within a reasonable time [22].

3. Why is my NMR data yielding inconsistent compound identification in statistical analysis, and how can FAIR practices help?

Inconsistent compound identification in NMR-based metabolomic studies can arise from incorrect referencing, inconsistent spectral alignment, mis-phasing, or flawed baseline correction [23]. Adhering to FAIR data management principles, which emphasize systematic organization and rich metadata, ensures that processing steps and parameters are well-documented. This documentation makes it easier to identify and correct the source of inconsistencies, improving the reliability of your results.

4. What is the most critical first step in making my spectral data FAIR?

The most critical first step is to ensure your instrument datasets are systematically organized and unambiguously associated with their corresponding chemical structure representations. This can be as simple as maintaining a well-organized set of file directories on an instrument, provided appropriate chemical structure representations are added consistently [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Mass Values in Mass Spectrometry Data

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate mass values | Calibration drift, method setup errors, spray instability [24] | Check and recalibrate the instrument; review method parameters for accuracy; inspect the ion source for stable spray performance. |

Issue: High Signal in LC-MS Blank Runs

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High signal in blanks | System contamination, carryover [24] | Perform thorough system washing and cleaning; check and replace consumables like injection needles and seals if necessary. |

Issue: Poor Spectral Alignment in NMR Metabolomics

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Misaligned peaks in stacked NMR spectra | Improper chemical shift referencing, pH-sensitive reference compounds, poor buffering of samples [23] | Use a pH-insensitive reference standard like DSS instead of TSP; ensure samples are properly buffered; re-reference all spectra to a consistent standard. |

Issue: Low Machine-Actionability of Spectral Metadata

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Machines cannot automatically find or process spectral data | Lack of (meta)data in a machine-readable format, absence of Globally Unique Persistent and Resolvable Identifiers (GUPRIs), inconsistent use of semantic (meta)data schemata [25] | Organize (meta)data into FAIR Digital Objects (FDOs) with GUPRIs (e.g., DOIs); use knowledge graphs with formal ontologies (e.g., OWL) to provide explicit, structured semantics. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

General Workflow for Creating a FAIRSpec-Ready Collection

The following diagram outlines the key stages in organizing a spectroscopic data collection for machine-assisted curation.

Protocol 1: Systematic File Organization for Spectroscopy Data

Objective: To create a directory and naming structure that maintains the critical link between a raw spectral dataset and the chemical structure it characterizes.

Methodology:

- Create a Master Directory: Establish a main directory for your project or compound series.

- Use Descriptive Naming Conventions: Name files and subdirectories with a consistent scheme that includes:

- Compound Identifier (e.g., a unique lab code)

- Technique (e.g.,

NMR,IR,MS) - Nucleus/Specifics (e.g.,

1H,13C) - Solvent (e.g.,

DMSO,CDCl3) - Date of acquisition (YYYY-MM-DD)

- Co-locate Data and Structure: In each subdirectory, store the raw instrument data file alongside a digital representation of the chemical structure (e.g., a MOL or SDF file) [22].

- Include a Readme File: Provide a text file explaining the naming convention and any other project-specific details.

Protocol 2: Standardized Preprocessing of 1H NMR Data for Urine Metabolomics

Objective: To ensure high-quality, consistent NMR spectra that are suitable for subsequent statistical analysis and machine-assisted curation, thereby enhancing reusability.

Methodology [23]:

- Chemical Shift Referencing: Reference all spectra using an internal standard. Recommendation: Use DSS over TSP due to its lower pH sensitivity, which provides more stable referencing.

- Phase and Baseline Correction: Manually check and correct the phase of all spectra. Apply a robust baseline correction algorithm to remove any instrumental or background artifacts.

- Spectral Alignment: Align peaks across all samples in the dataset to correct for small shifts caused by minor variations in sample pH, temperature, or salt concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials for ensuring data quality in NMR-based metabolomic studies, which is a foundation for creating reusable FAIR data.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for FAIR Data |

|---|---|---|

| DSS (4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid) | Internal chemical shift reference standard for NMR spectroscopy [23]. | Using a pH-insensitive standard like DSS, and documenting its use in metadata, improves spectral alignment and interoperability across datasets. |

| Deuterated Solvent (e.g., D₂O) | Provides the lock signal for the NMR spectrometer and dissolves the sample. | The solvent type must be unambiguously recorded in the sample metadata, as it profoundly affects chemical shifts. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Phosphate Buffer) | Maintains a constant pH across all samples in a study. | Consistent pH is critical for reproducible NMR chemical shifts. Documenting buffer type and concentration in metadata is essential for data reuse. |

| Data Management Plan (DMP) | A formal document outlining how data will be handled during and after a research project. | A DMP that explicitly addresses FAIR principles is now a mandatory requirement for many funding agencies [22]. |

Workflow for Spectral Data Preprocessing in Machine Learning

Advanced spectral analysis, including for resolving coordination modes, often relies on machine learning. The quality of the input data is paramount, as outlined in the following preprocessing workflow.

This case study examines the application of pre-synthetic redox control to resolve coordination mode ambiguity in copper Tetrathiafulvalene-2,3,6,7-tetrathiolate (TTFtt) coordination polymers (CPs). For researchers in spectroscopic data research, distinguishing between metal oxidation states and ligand coordination modes presents significant analytical challenges, particularly in sulfur-rich systems where strong metal-ligand covalency leads to rapid, irreversible coordination that often yields amorphous materials difficult to characterize [26] [27]. The pre-synthetic redox strategy demonstrated with Cu-TTFtt systems provides a methodological framework for programming desired oxidation states prior to coordination polymer synthesis, thereby reducing spectroscopic ambiguity and enabling precise structure-property relationships [27] [28].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Synthesis of CuTTFtt and Cu2TTFtt Coordination Polymers

Principle: Pre-synthetic redox control of the TTFtt(SnBu₂)₂ⁿ⁺ transmetalating synthon enables programming of the TTFtt oxidation state prior to coordination polymer formation, directing structural dimensionality and properties [27].

Synthesis of CuTTFtt (1D Chain Structure)

- Step 1: Oxidize TTFtt(SnBu₂)₂ using FcBzoBArF₄ (benzoylferrocenium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate) in dichloromethane (DCM) [27] [28].

- Step 2: Dissolve CuCl₂ in methanol (MeOH) [27] [28].

- Step 3: Mix the CuCl₂/MeOH solution with the oxidized TTFtt(SnBu₂)₂ DCM solution [27] [28].

- Step 4: Isolate the immediate black precipitate (CuTTFtt) after workup [27] [28].

- Key Oxidation State: TTFtt ligand is in a formally oxidized TTFtt²⁻ state [27].

Synthesis of Cu₂TTFtt (2D Ribbon-like Structure)

- Step 1: Mix two equivalents of Cu(acacF₃)₂ (trifluoroacetylacetonate) with excess tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) in tetrahydrofuran (THF), noting immediate color change from blue to green indicating [(Cu(TMEDA)₂)]²⁺ formation [27] [28].

- Step 2: Add one equivalent of TTFtt(SnBu₂)₂ in THF to the copper-TMEDA complex [27] [28].

- Step 3: Isolate the immediate dark green (nearly black) powder [27] [28].

- Step 4: Dry the powder at 70°C to yield Cu₂TTFtt [27] [28].

- Key Oxidation State: TTFtt ligand is in a reduced TTFtt³⁻ state [27].

- Composition Note: The final compound includes 0.5 TMEDA molecules per formula unit (Cu₂C₆S₈(C₆H₁₆N₂)₀.₅) [27] [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Reagents for Copper TTFtt Coordination Polymer Synthesis

| Reagent Name | Function/Purpose | Critical Notes for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| TTFtt(SnBu₂)₂ⁿ⁺ | Redox-tunable transmetalating synthon | Core building block; 'n' determines pre-programmed TTFtt oxidation state (0 for TTFtt⁴⁻, 2 for TTFtt²⁻) [27]. |

| FcBzoBArF₄ | Chemical oxidant | Pre-oxidizes TTFtt(SnBu₂)₂ for CuTTFtt synthesis [27] [28]. |

| CuCl₂ | Copper source | Metal precursor for CuTTFtt (1D) synthesis [27] [28]. |

| Cu(acacF₃)₂ | Copper source | Metal precursor for Cu₂TTFtt (2D) synthesis [27] [28]. |

| TMEDA (Tetramethylethylenediamine) | Structure-directing ligand | Critical for forming 2D Cu₂TTFtt structure; incorporated in final product [27] [28]. |

| Solvents (DCM, MeOH, THF) | Reaction media | Use anhydrous, deoxygenated solvents to prevent unintended oxidation [27]. |

Material Characterization Workflow

The experimental workflow for synthesizing and characterizing the copper TTFtt coordination polymers involves sequential steps to ensure proper structure and property analysis.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Composition & Structural Analysis

FAQ: How do I confirm the chemical composition and structure of my synthesized copper TTFtt material?

- Recommended Protocol: Employ a multi-technique approach:

- X-ray Fluorescence (XRF): Determine elemental ratios (Cu:S). Cu₂TTFtt shows ~1:3.78 Cu:S ratio; CuTTFtt shows ~1:9.7 Cu:S ratio [27] [28].

- Combustion Analysis: Quantify carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen content. This detects organic components (e.g., TMEDA in Cu₂TTFtt) [27] [28].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Identify mass loss steps corresponding to ligand decomposition or solvent loss [27] [28].

- Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD): Assess crystallinity and compare with predicted structures. CuTTFtt is largely amorphous with a broad PXRD feature, while Cu₂TTFtt shows some broad peaks indicating higher structural order [28].

- Recommended Protocol: Employ a multi-technique approach:

Troubleshooting Guide: My product is consistently amorphous by PXRD.

- Problem: Rapid, irreversible metal-thiolate coordination kinetics favor amorphous products [27].

- Solution A: Verify pre-synthetic redox control. Ensure stoichiometric oxidant (for CuTTFtt) or reductant is used and confirm reaction completion before copper addition [27].

- Solution B: For Cu₂TTFtt, confirm TMEDA is present in excess, as it acts as a structure-directing agent [27] [28].

- Solution C: Use synchrotron PXRD (λ = 0.167 Å) for improved signal-to-noise and better detection of weak or broad features [28].

Spectroscopic Characterization & Ambiguity Resolution

- FAQ: What spectroscopic techniques definitively assign metal and ligand oxidation states?

- Multi-Technique Strategy:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Resolve copper oxidation state (Cu(I) vs Cu(II)) and sulfur electronic environment [27].

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Probe copper oxidation state and local coordination geometry independent of long-range order [27].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Identify vibrational fingerprints of the TTFtt core in different oxidation states (e.g., TTFtt²⁻ vs TTFtt³⁻) [27].

- Multi-Technique Strategy:

Table 2: Key Spectroscopic Features for Resolving Redox Ambiguity in Copper TTFtt CPs

| Analytical Technique | Parameter Measured | Interpretation Guide for Copper TTFtt CPs |

|---|---|---|

| XPS | Cu 2p peak position & satellites | Differentiate Cu(I) (lack of strong satellites) from Cu(II) (characteristic shake-up satellites) [27]. |

| XPS | S 2p peak envelope | Deconvolute contributions from thiolate (coordinating S) and TTF-core S atoms; shifts indicate oxidation state changes [27]. |

| XAS | Cu K-edge energy position | Higher edge energy indicates higher copper oxidation state (Cu(II) > Cu(I)) [27]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | TTF-core vibrational modes | Frequency shifts and intensity changes serve as fingerprints for TTFtt²⁻ (oxidized) vs TTFtt³⁻ (reduced) states [27]. |

- Troubleshooting Guide: My spectroscopic data is noisy or contains artifacts, complicating interpretation.

- Problem: Spectral data is degraded by noise, baseline drift, or scattering effects [29].

- Solution A: Apply appropriate spectral preprocessing techniques before analysis [29]:

- Baseline Correction: Essential for Raman and XPS to remove fluorescent background or instrumental offset [29].

- Smoothing/Filtering: Reduces high-frequency noise but avoid over-smoothing to prevent loss of spectral features [29].

- Spectral Derivatives: Enhance resolution of overlapping peaks (e.g., in XPS S 2p region) [29].

- Solution B: Fuse multiple techniques. Never rely on a single method. Correlate XPS binding energies with XAS edge positions and Raman shifts for definitive assignment [27].

Physical Property Measurements

FAQ: Why does Cu₂TTFtt show higher conductivity than CuTTFtt?

FAQ: How do I explain the contrasting magnetic properties (diamagnetism in Cu₂TTFtt vs. paramagnetism in CuTTFtt)?

- Interpretation Guide:

- The diamagnetism in Cu₂TTFtt suggests strong antiferromagnetic coupling between copper centers or closed-shell electronic configurations, likely enabled by the different structure and Cu/Cu interactions in the 2D framework [26] [27].

- The paramagnetism in CuTTFtt indicates the presence of unpaired electrons, consistent with a different electronic structure in the 1D chain [26] [27].

- Key Action: Correlate magnetic data with oxidation state information from spectroscopy. The different TTFtt oxidation states (TTFtt³⁻ in Cu₂TTFtt vs TTFtt²⁻ in CuTTFtt) and structural dimensionality dictate the magnetic interaction pathways [27].

- Interpretation Guide:

Data Interpretation & Computational Validation

- Troubleshooting Guide: My experimental property data conflicts with initial hypotheses.

- Problem: Ambiguity in electronic structure models leads to incorrect prediction of properties like conductivity or magnetism [27].

- Solution: Employ Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations to build atomistic models.

- Use experimental composition and spectroscopic data (oxidation states, local coordination) to build initial computational models [27].

- Calculate electronic band structure, density of states, and magnetic exchange couplings [27].

- Validate the model by comparing calculated properties (e.g., conductivity trends, magnetic behavior) with measured data [26] [27]. DFT provides a theoretical framework to rationalize why Cu₂TTFtt is more conductive and why its magnetic behavior differs from CuTTFtt [26] [27].

The pre-synthetic redox methodology for copper TTFtt CPs provides a robust framework for resolving coordination mode ambiguity in spectroscopic data research. By programming oxidation states prior to synthesis and employing correlated spectroscopic and computational analyses, researchers can systematically deconvolute complex data, establish clear structure-property relationships, and rationally design materials with tailored electronic and magnetic properties. This approach is broadly applicable to the study of conductive coordination polymers with redox-active ligands.

Overcoming Common Pitfalls: A Practical Guide for Reliable Data Analysis

Optimizing Signal Contribution to Minimize Rotational Ambiguity

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Rotational Ambiguity in Multivariate Curve Resolution

Q1: What is rotational ambiguity, and why is it a critical issue in spectroscopic data analysis?

Rotational ambiguity is a phenomenon in Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS) where a range of mathematically feasible solutions exist, all fitting the data equally well but leading to different chemical interpretations [30]. This is particularly problematic when the second-order advantage is sought—determining analytes in samples containing uncalibrated components not present in the calibration set [31]. It introduces uncertainty in quantitative analysis, making results less reliable and potentially leading to inaccurate analyte concentrations if not properly characterized [30].

Q2: Under which experimental conditions is rotational ambiguity most likely to occur?

Rotational ambiguity is most pronounced under these conditions [30]:

- High Spectral Overlapping: When the spectra of different components in a mixture are very similar.

- Presence of Uncalibrated Components: When unknown interferents are present in validation samples but not in the calibration set.

- Limited Applicable Constraints: When only basic constraints like non-negativity can be applied, and stronger constraints (e.g., unimodality, selectivity) are not applicable.

Q3: What tools can I use to assess the level of rotational ambiguity in my MCR-ALS model?

You should accompany your MCR-ALS decomposition results with a rotational ambiguity analysis [30]. The channel-wise N-BANDS algorithm is a key tool for this purpose [30]. It helps estimate the range of feasible solutions and the associated uncertainty in the retrieved concentration profiles and analyte quantitation. This analysis provides insight into the reliability of your results.

Q4: How can I minimize rotational ambiguity during experimental design?

To minimize rotational ambiguity, aim to increase the selectivity in your data [30]. This can be achieved by:

- Designing experiments that enhance spectral differences between components (e.g., using separation techniques or specific sensors).

- Ensuring calibration samples encompass all potential components expected in unknown samples.

- Applying all chemically meaningful constraints during the MCR-ALS optimization.

Troubleshooting Common MCR-ALS Problems

Problem: Inconsistent or unreliable quantitative results across similar samples.

- Potential Cause: High rotational ambiguity due to significant spectral overlapping or unmodeled interferents [30].

- Solution: Perform a rotational ambiguity analysis using tools like channel-wise N-BANDS. Report the uncertainty in concentration estimates alongside your results [30] [31].

Problem: Retrieved concentration or spectral profiles are chemically unrealistic.

- Potential Cause: The MCR-ALS algorithm may have converged to a mathematically sound but chemically incorrect solution within the feasible range due to rotational ambiguity [30].

- Solution: Review and strengthen applied constraints. Incorporate any prior knowledge (e.g., pure spectrum of an analyte) and verify the analysis with a rotational ambiguity assessment [30].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Rotational Ambiguity with Channel-wise N-BANDS

This protocol details the procedure for sizing the impact of rotational ambiguity following MCR-ALS decomposition [30].

1. Principle After an MCR-ALS model is optimized, the channel-wise N-BANDS algorithm calculates the boundaries of the feasible solutions for each component's profile. It evaluates the maximum and minimum possible contributions under the given constraints, providing a measure of uncertainty.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Build your first-order data matrix D (e.g., samples × wavelengths) [30].

- Step 2: Decompose D using MCR-ALS into concentration matrix C and spectral profiles matrix S (D = CS^T + E) [30].

- Step 3: Apply all relevant constraints (non-negativity, correspondence, etc.) during the ALS optimization.

- Step 4: Input the obtained MCR-ALS solution and the same constraints into the channel-wise N-BANDS algorithm.

- Step 5: Run the analysis to determine the range of feasible solutions for the concentration profiles.

3. Data Interpretation The output defines the upper and lower bounds for the concentration of each component in each sample. A large range between these bounds indicates high rotational ambiguity and greater uncertainty in the quantitative results.

Protocol 2: MCR-ALS with Correspondence Constraint for Uncalibrated Components

This protocol is for handling samples containing interferents not present in the calibration set [30].

1. Principle The correspondence constraint forces the concentrations of specific components (the uncalibrated interferents) to be zero in the calibration samples. This helps isolate the interferents' signal in the test samples, leveraging the second-order advantage.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Create an augmented data matrix that includes both calibration and test sample data.

- Step 2: Define the correspondence matrix. This matrix indicates which components are present in which samples.

- Step 3: For calibration samples, set the correspondence for uncalibrated interferents to zero.

- Step 4: Apply the correspondence constraint during MCR-ALS optimization along with other constraints like non-negativity.

- Step 5: Even with this constraint, rotational ambiguity may persist. Always follow with a rotational ambiguity analysis as described in Protocol 1 [30].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Methods for Quantitative Assessment of Rotational Ambiguity

| Method | Primary Function | Key Outcome | Applicable System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel-wise N-BANDS [30] | Estimates the range of feasible MCR-ALS solutions. | Upper and lower bounds for concentration profiles. | Multi-component systems with various constraints. |

| MCR-BANDS [31] | Calculates the extent of rotational ambiguity. | Feasible band boundaries for profiles. | Second-order calibration data. |

| RMSE Figure of Merit [30] | Characterizes uncertainty in analyte quantitation. | A single RMSE value representing prediction uncertainty. | For reporting quantitative reliability. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MCR Studies

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| MCR-ALS Software | Core algorithm for bilinear decomposition of spectral data matrices [30]. |

| Rotational Ambiguity Analysis Tool (e.g., N-BANDS) | Critical software for assessing the uncertainty and reliability of the MCR-ALS solution [30]. |

| Spectral Data Set | First- or second-order instrumental data (e.g., UV-Vis, NIR, fluorescence spectra) for building the data matrix D [30]. |

| Chemically Meaningful Constraints | Prior knowledge (e.g., non-negativity, unimodality, closure) applied to ensure chemically valid solutions [30]. |

Diagram Specifications

MCR Ambiguity Analysis Workflow

Factors Affecting Rotational Ambiguity

Addressing Challenges in Low Site Symmetry and Redox-Active Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary cause of ambiguity when resolving spectroscopic data from systems with low site symmetry? A1: The primary cause is rotational ambiguity in self-modeling curve resolution (SMCR) methods. This arises when multiple mathematically feasible solutions exist for component spectra and concentrations, all of which can fit the original data equally well. In systems with highly overlapping spectral bands and complex concentration profiles, this can lead to solutions that are mathematically sound but physically meaningless [32].

Q2: Our SMCR analysis, specifically using the Orthogonal Projection Approach (OPA), yields concentration profiles that violate known physical constraints of the reaction. What steps should we take? A2: This indicates the algorithm has converged on an incorrect, albeit mathematically valid, solution due to rotational ambiguity. You should:

- Apply Manual Constraints: Intervene by manually correcting erroneous parts of the concentration profiles based on your understanding of the reaction's physical chemistry [32].

- Validate with Prior Knowledge: Use known pure-component spectra or expected concentration behaviors (e.g., non-negativity, known reaction kinetics) to guide and validate the resolved profiles [32].

- Explore Feasible Solutions: Utilize optimization routines to map the range of all possible non-negative solutions and select the one that is most chemically reasonable [32].

Q3: How can we improve the reliability of real-time monitoring for redox-active systems like block-copolymerization? A3: Combine robust spectroscopic setups with SMCR methods, but be prepared for post-processing. For instance, using on-line FT-Raman spectroscopy with optical fibres provides excellent data, but you must manually verify and correct the resolved concentration profiles to overcome the inherent ambiguities of fully automatic SMCR routines [32].

Experimental Protocol: Resolving Spectroscopic Data with SMCR

This protocol outlines the application of Self-Modeling Curve Resolution (SMCR) for analyzing time-dependent spectroscopic data from a complex system, such as a styrene/1,3-butadiene block-copolymerization [32].

1. Experimental Setup and Data Collection

- Reaction: Perform the polymerization in a suitable reactor (e.g., a 1L double-walled glass reactor). For the referenced study, anionic dispersion polymerization was initiated with sec-butyllithium in pentane at 45°C, with 1,3-butadiene added after 50% of styrene conversion [32].

- Spectroscopic Monitoring: Use an on-line Fourier Transform (FT)-Raman spectrometer equipped with optical fibre probes. Collect spectra at regular intervals throughout the reaction (e.g., 114 spectra over the reaction course) [32].

- Spectral Region: Focus on a spectral region where changes are observable, even if bands are severely overlapping (e.g., 1720–1620 cm⁻¹ for the referenced polymerization) [32].

2. Data Analysis via Orthogonal Projection Approach (OPA)

- Application: Apply the OPA algorithm to the collected set of spectra. OPA works by searching for the most dissimilar spectra in the data set to identify pure components [32].

- Initial Resolution: Allow the routine to automatically resolve the data into pure component spectra and their corresponding concentration profiles.

3. Handling Ambiguity and Manual Correction

- Identify Physical Faults: Examine the initial OPA results. Check for concentration profiles that violate physical laws, such as negative concentrations or profiles that do not align with known reaction stages [32].

- Manual Intervention: Manually correct the erroneous sections of the concentration profiles. In the referenced study, this step was crucial for obtaining physically acceptable results for the styrene component [32].

- Iterative Improvement: Use the corrected profiles to recalculate and improve the resolved pure component spectra.

4. Validation

- Cross-Reference: Compare the final resolved spectra and profiles with known standards or expected chemical behavior to ensure they are chemically meaningful [32].

Key Reagent Solutions for SMCR and Redox Flow Battery Research

The table below details key materials used in the fields of spectroscopic analysis and redox flow batteries, as discussed in the search results.

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| FT-Raman Spectrometer | Enables on-line, real-time monitoring of chemical reactions via optical fibres, providing the complex spectral data for SMCR analysis [32]. |

| Organic Bipolar Molecules | Serves as the single active material in both electrodes of a symmetric organic redox flow battery (ORFB), simplifying battery design [33]. |

| CNES Real-Time Products | Provides real-time precise satellite orbit, clock, and phase bias corrections. Essential for achieving ambiguity resolution in Real-Time Precise Point Positioning (PPP) for GPS/Galileo/BDS systems [34]. |

| Orthogonal Projection Approach (OPA) | A specific self-modeling curve resolution (SMCR) method used to resolve a set of spectra into pure component spectra and concentration profiles without prior information [32]. |

The following tables summarize quantitative findings from recent studies on real-time ambiguity resolution and organic redox flow batteries.

Table 1: Quality of Real-Time Ambiguity Resolution (AR) for Different Satellite Systems [34] This data is based on the analysis of wide-lane (WL) and narrow-lane (NL) residuals from 37 MGEX stations using CNES real-time products. A higher percentage within ±0.25 cycles indicates better AR quality.

| System | WL Residuals within ±0.25 cycles | NL Residuals within ±0.25 cycles |

|---|---|---|

| GPS | 98.9% | 95.3% |

| Galileo | 98.2% | 94.3% |

| BDS | 97.3% | 73.1% |

Table 2: Convergence Time in Real-Time Precise Point Positioning with Ambiguity Resolution [34]