Resolving Band Structure and DOS Mismatches: A Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a systematic framework for identifying, diagnosing, and resolving discrepancies between band structure and density of states (DOS) calculations in computational materials science.

Resolving Band Structure and DOS Mismatches: A Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for identifying, diagnosing, and resolving discrepancies between band structure and density of states (DOS) calculations in computational materials science. Covering fundamental principles through advanced validation techniques, we address common pitfalls including k-point sampling inadequacies, smearing parameter selection, and methodological inconsistencies. Through practical troubleshooting protocols and comparative analysis methods, this guide enables researchers to achieve consistent electronic structure characterization essential for reliable materials design and drug development applications.

Understanding the Roots of Band Structure-DOS Discrepancies

Fundamental Differences Between Band Structure and DOS Calculation Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my band structure and density of states (DOS) plots show different band gaps?

The band gap derived from a band structure calculation can differ from the one obtained from the DOS due to fundamental differences in how these properties are computed [1] [2].

- Different k-space Sampling: The DOS calculation typically uses a uniform k-point grid that samples the entire Brillouin Zone (BZ). In contrast, a band structure calculation is performed along specific high-symmetry lines between high-symmetry points [3] [2]. The conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) might lie at a k-point not included in the high-symmetry path but captured by the uniform k-grid used for the DOS [2].

- Interpolation vs. Direct Calculation: The band gap printed in output files is often from an "interpolation method" that quadratically interpolates bands over the whole BZ. The band structure plot uses a "from band structure method" with a dense sampling along a specific path. These methods can yield different results for the gap [1].

Q2: My DOS shows states in an energy region where the band structure has a gap. What is wrong?

This common problem, known as "missing DOS," is almost always caused by insufficient k-point sampling during the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation that generates the charge density [4] [1]. A coarse k-grid fails to accurately capture the electronic states across the entire BZ. The solution is to restart the calculation with a finer k-point grid (improved KSpace%Quality or a denser Monkhorst-Pack grid) [4] [1]. Additionally, ensure the energy grid for the DOS is sufficiently fine by decreasing the DOS%DeltaE parameter [1].

Q3: What should I do if my calculation fails due to a "dependent basis" error?

A "dependent basis" error indicates that the set of Bloch functions constructed from your basis set is nearly linearly dependent, threatening numerical accuracy [1]. Do not simply adjust the dependency criterion to bypass the error [1]. Instead, address the root cause by adjusting the basis set. The most common solution is to use confinement to reduce the range of diffuse basis functions, which are usually the culprits, especially in highly coordinated systems [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Band Structure and DOS Mismatch

Problem Definition

A mismatch occurs when the electronic information from a band structure calculation does not align with the information from the Density of States (DOS). This includes discrepancies in the band gap, the presence or absence of states at specific energies, or the general shape of spectral features [1] [2].

Diagnosis and Resolution Protocol

Follow this workflow to diagnose and resolve the mismatch.

Step 1: Verify K-point Grid Convergence

The most common cause of mismatch is an inadequately converged k-point grid during the initial self-consistent charge calculation [3] [1].

- Action: Perform a convergence test. Run a series of SCF calculations with progressively denser k-point grids (e.g.,

SupercellFoldingwith 4x4x4, 8x8x8, etc.) and monitor the total energy. A well-converged calculation shows minimal energy change with a denser grid [3]. - Protocol:

- Use your primary input with varying

KPointsAndWeightsblocks. - Set

Scc = YesandSccTolerance = 1e-5(or tighter) [3]. - Copy the resulting

charges.binfrom the converged calculation for subsequent band structure and DOS runs.

- Use your primary input with varying

Step 2: Address Band Gap Discrepancies

If the band gap from the DOS and band structure differ, it's often because the CBM/VBM are not on the high-symmetry path [1] [2].

- Action: Recompute the band gap directly from the DOS data, which samples the entire BZ and is often more reliable for this specific property [2].

- Protocol (using pymatgen with Materials Project API):

Step 3: Resolve Feature Mismatches and Artifacts

- Missing DOS Peaks: If the band structure shows bands in an energy range where the DOS is zero, the k-grid for the DOS is likely too coarse. Restart the DOS calculation with a significantly denser k-point grid [4] [1].

- Energy Shifts: Ensure the Fermi level is consistent. Use the same reference energy when plotting both band structure and DOS.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Calculations

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Band Structure and DOS

This protocol ensures consistent results by using a well-converged charge density as the starting point for both non-self-consistent field (NSCF) calculations [3] [2].

Detailed Steps:

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation

- Purpose: Obtain a converged charge density for the system [3].

- Input Settings:

- Output: The crucial

charges.binfile.

Band Structure Calculation (NSCF)

- Purpose: Calculate eigenvalues along a high-symmetry path.

- Input Settings:

ReadInitialCharges = Yes(Crucial: readscharges.bin).MaxSCCIterations = 1(since no new SCC is needed).KPointsAndWeights = Klines { ... }with a list of high-symmetry points and the number of k-points between them [3].

DOS Calculation (NSCF)

- Purpose: Calculate eigenvalues on a dense, uniform k-grid for DOS.

- Input Settings:

ReadInitialCharges = Yes.MaxSCCIterations = 1.- A dense, uniform k-point grid (often denser than the SCF grid).

- Enable DOS and PDOS output (e.g.,

Analysis = { ProjectStates { ... } }in DFTB+) [3].

Protocol 2: K-point Convergence Testing

This protocol establishes a reliable k-point grid for the SCF calculation.

- Identify a key observable: Total energy is a sensitive probe [3].

- Run a series of calculations: Using identical inputs except for the k-point grid. Systematically increase the grid density (e.g., 2x2x2, 4x4x4, 6x6x6, 8x8x8).

- Analyze results: Plot the total energy versus the inverse of the k-grid density. The grid is considered converged when the energy change is smaller than your desired accuracy (e.g., 1e-3 eV) [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational "Reagents" for Band Structure and DOS Calculations

| Item / Software Tool | Function / Purpose | Key Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DFTB+ | An efficient software for electronic structure calculations using Density Functional based Tight Binding (DFTB). Used for calculating band structures, DOS, and PDOS [3]. | SccTolerance, KPointsAndWeights, ReadInitialCharges. Requires Slater-Koster parameter files (e.g., mio, tiorg) [3]. |

| dptools Package | A set of utilities distributed with DFTB+. Contains scripts for post-processing results [3]. | dp_dos tool converts band.out to plottable DOS files. Use -w flag for PDOS files [3]. |

| VASP | A widely used software for performing ab initio quantum mechanical calculations using Density Functional Theory (DFT). | Key for computing ground-state densities, band structures, and DOS with PAW pseudopotentials. |

| pymatgen | A robust Python library for materials analysis. Provides powerful tools for analyzing DOS and band structure objects [2]. | get_gap(), get_cbm_vbm() methods. Can interface with databases like the Materials Project [2]. |

| K-point Grid | The sampling mesh in reciprocal space. The most critical "reagent" for convergence [3] [2]. | Use SupercellFolding or MonkhorstPack. Must be tested for convergence for both SCF and DOS [3]. |

| Slater-Koster Files | Parameterized files containing integrals for the DFTB Hamiltonian. Act as the "basis set" for DFTB+ calculations [3]. | Examples: mio, tiorg. Must be specified in the input via SlaterKosterFiles [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why does the sum of my projected density of states (PDOS) not match the total DOS? This is often due to an incomplete basis set for the projections. Specifically, the pseudopotential file used may only contain atomic wavefunctions for a limited set of orbitals (e.g., 2s and 2p for carbon). If the calculation includes bands with higher orbital character (e.g., d-bands) that are not present in the pseudopotential, those states will not be captured in the PDOS, causing a mismatch with the total DOS [5]. The solution is to ensure your pseudopotential includes the necessary orbital channels for the energy range you are investigating.

2. Why is there a discrepancy between the band gap reported in my DOS calculation and my band structure calculation? The DOS and band structure are typically calculated using different k-point grids. The uniform k-point grid used for DOS might not include the specific k-points where the valence band maximum (VBM) or conduction band minimum (CBM) occurs, which are precisely mapped in a line-mode band structure calculation. Therefore, the band gap from the DOS can differ from the fundamental gap determined from the band structure [2]. It is recommended to use the band structure for determining the fundamental gap.

3. My calculation shows a 0 eV band gap for a material known to be an insulator. Is this a physical result or an error? A reported 0 eV band gap can have several causes. It could be a physical result if the material is actually a metal or semimetal. However, it can also be a limitation of the DFT functional (like GGA-PBE, which is known to underestimate band gaps), a parsing artifact in the database, or an issue with the automatic detection of band edges in a complex DOS [2]. The band gap should be recomputed manually from the DOS or band structure data to verify.

4. My SCF calculation does not converge for a metallic system. What can I do?

Systems with metallic character can be more challenging to converge. You can adopt more conservative settings, such as decreasing the SCF mixing parameter or the DIIS dimension (DIIS%Dimix) [1]. Alternatively, using a finite electronic temperature at the beginning of a geometry optimization can help achieve initial convergence, with the temperature being reduced as the geometry optimizes [1].

5. I cannot see core-level bands or DOS peaks in my visualization. What is wrong?

By default, the energy window for saving bands is often limited. To see deep core levels, you need to increase the EnergyBelowFermi parameter in the band structure or DOS input to a value large enough to encompass the core states (e.g., 10000 eV) [1]. Additionally, you must ensure that no frozen core approximation is active by setting the frozen core to None [1].

Troubleshooting Guide

Symptom 1: Missing Peaks in Projected DOS (PDOS)

When the summed PDOS across all atoms or orbital types does not equal the total DOS, particularly at higher energies, follow this diagnostic workflow:

Diagnosis and Solution: The most common cause is that the pseudopotential (PSP) used for the projection lacks the higher atomic orbital channels needed to describe the conduction bands. For example, a carbon pseudopotential might only contain 2s and 2p orbitals. If the conduction bands have significant 3d character, these states will be absent from the PDOS [5].

Protocol:

- Inspect Pseudopotential: Check the header of your pseudopotential file to see which orbital channels (e.g., 3s, 3p, 3d) are included and which are neglected.

- Identify Missing Orbitals: Based on the atomic species and energy range of interest, identify the missing orbital channels. Consultation with electronic structure literature for the element is helpful.

- Generate New Pseudopotential: Use the

ld1.xcode (part of Quantum ESPRESSO) or a similar tool to generate a new pseudopotential that includes the previously neglected orbital channels [5]. - Re-run Calculation: Perform a new self-consistent field (SCF) calculation and subsequent PDOS calculation using the updated pseudopotential.

Symptom 2: Band Gap Inconsistencies between DOS and Band Structure

Discrepancies in the reported band gap value when comparing DOS and band structure outputs are often a sampling issue.

Diagnosis and Solution: The DOS is calculated on a uniform k-point grid that samples the entire Brillouin zone. The band structure is calculated along a specific high-symmetry path. It is possible that the CBM or VBM lies at a k-point not on this path or not sampled by the uniform grid. The band gap from the band structure is generally considered the fundamental gap, while the DOS gap can be different if the k-grid misses the extrema [2].

Protocol for Verification:

- Converge K-point Grid: Systematically increase the density of the k-point grid (

KSpace%Quality) for the DOS calculation until the band gap value stabilizes [1]. - Use Band Structure for Gap: Rely on the band structure calculation for reporting the fundamental band gap, as it can interpolate between k-points to find the true VBM and CBM [1] [6].

- Manual Inspection: Manually inspect the band structure plot and the DOS near the Fermi level to identify the locations of the VBM and CBM.

Symptom 3: Unexpected Zero Band Gap

When a material is calculated or reported to have a 0 eV band gap unexpectedly.

Diagnosis and Solution: This can be a true physical result, a known DFT error (band gap underestimation), or a parsing/analysis artifact [2].

Verification Protocol (using the Materials Project API and pymatgen):

- Recompute from DOS: If this gives a non-zero value, the initial 0 eV gap was likely a parsing error [2].

- Recompute from Band Structure (using VBM from DOS): If the Fermi level in the band structure data is misplaced, you can correct it using the VBM from the more robust DOS calculation [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational parameters and their functions, which are essential for diagnosing and resolving DOS and band gap issues.

| Item/Parameter | Primary Function | Troubleshooting Role |

|---|---|---|

K-point Grid Quality (KSpace%Quality) |

Determines the sampling density of the Brillouin Zone. | A coarse grid can cause DOS peaks to be missing or smeared and lead to band gap inconsistencies. Improving k-point quality is a primary convergence step [1] [2]. |

| Pseudopotential (PSP) File | Defines the interaction between ions and valence electrons, including the atomic orbitals available for projection. | An incomplete PSP lacking higher orbitals (e.g., 3d for C) is the primary cause of missing PDOS peaks in the conduction band [5]. |

Energy Window (EnergyBelowFermi, EnergyAboveFermi) |

Sets the energy range for which band structure and DOS data are saved and plotted. | If set too small, it can cause core-level bands and DOS peaks to be missing from the output and visualization [1]. |

SCF Convergence Parameters (SCF%Mixing, DIIS%Dimix) |

Controls the algorithm for achieving self-consistency in the electronic density. | Poor SCF convergence can lead to incorrect total DOS and spurious results. Tuning these is crucial for difficult systems like metals [1]. |

| Band Structure DeltaK | Sets the interpolation step between high-symmetry k-points for band structure plots. | A large DeltaK can result in a non-smooth band structure that might misrepresent the true band dispersion and gap [6]. |

The table below provides a quick reference for key parameters discussed in this guide, their typical symptoms when misconfigured, and recommended actions.

| Symptom Pattern | Critical Parameters to Check | Recommended Action / Code Command |

|---|---|---|

| Missing PDOS Peaks | Pseudopotential orbital channels | Generate a new PSP with ld1.x including all relevant channels (e.g., 3s, 3p, 3d) [5]. |

| Band Gap Inconsistencies | KSpace%Quality, DOS%DeltaE |

Increase k-grid density for DOS; use band structure for fundamental gap [1] [2]. |

| Unexpected 0 eV Gap | - (Often a DFT/parsing issue) | Recompute gap from DOS: dos.get_gap() in pymatgen [2]. |

| Invisible Core Levels | BandStructure%EnergyBelowFermi, Frozen Core |

Set EnergyBelowFermi to a large value (e.g., 10000) and FrozenCore to None [1]. |

| Non-Smooth Bands | BandStructure%DeltaK |

Decrease DeltaK (e.g., to 0.03) for a smoother band structure plot [6]. |

The Critical Role of k-point Sampling in BZ Integration

Frequently Asked Questions

What is k-point sampling and why is it critical? K-points are discrete points used to sample the Brillouin Zone (BZ), the unit cell of the reciprocal lattice. Accurate integration over the BZ is essential because all electronic properties of a crystal, like total energy and charge density, are determined by integrating over this zone [7]. Insufficient sampling leads to errors in total energies, inaccuracies near the Fermi level, and a poor representation of the Density of States (DOS) [7].

Why might my band structure and Density of States (DOS) show mismatches? This is a common issue rooted in how these two properties are calculated [1].

- DOS Calculation (Interpolation Method): The DOS is derived from a k-space integration that samples the entire Brillouin zone, typically using interpolation between a grid of k-points [1]. It can therefore capture the true band gap if the k-grid is sufficiently dense.

- Band Structure Calculation (Band Structure Method): The band structure is calculated by plotting energies along a specific, high-symmetry path in the BZ [1]. While the k-point sampling along this path can be very dense, it might miss the actual points where the valence band maximum (VBM) or conduction band minimum (CBM) occur if they are not located on this path [1]. A converged DOS is often the more reliable method for determining the fundamental band gap [1].

My calculation is for a metal and won't converge. What can I do? Metals are challenging because of the discontinuous Fermi surface. You can try:

- Use the tetrahedron method: This method, especially with Blöchl corrections, is often the best choice for small metallic systems as it provides excellent convergence for the single-particle sum [8].

- Increase k-point density: Metallic systems require a much higher density of k-points to converge the total energy because the Fermi surface creates a discontinuity [7] [9].

- Employ smearing: Use Methfessel-Paxton or Fermi-Dirac smearing to artificially smear occupational states around the Fermi level. This makes the integrand smoother and accelerates convergence, though it introduces a small, controllable error [8].

How do I systematically test for k-point convergence?

- Start with a coarse k-point grid.

- Gradually increase the sampling density (e.g., from 4×4×4 to 8×8×8, etc.).

- Monitor the change in the total energy of your system. The calculation is considered converged when the energy change between successive grids falls below a desired threshold (e.g., 1 meV/atom) [7] [10].

- Create a table to track your progress [7]:

k-grid Number of k-points Total Energy (eV) ΔE (meV) 4x4x4 ... ... ... 6x6x6 ... ... ... 8x8x8 ... ... ...

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Band Structure and DOS Do Not Agree on Band Gap Value

Issue Description A user finds a significant discrepancy (e.g., 0.27 eV for silicon) between the band gap reported by the band structure object and the DOS object in their analysis code [11].

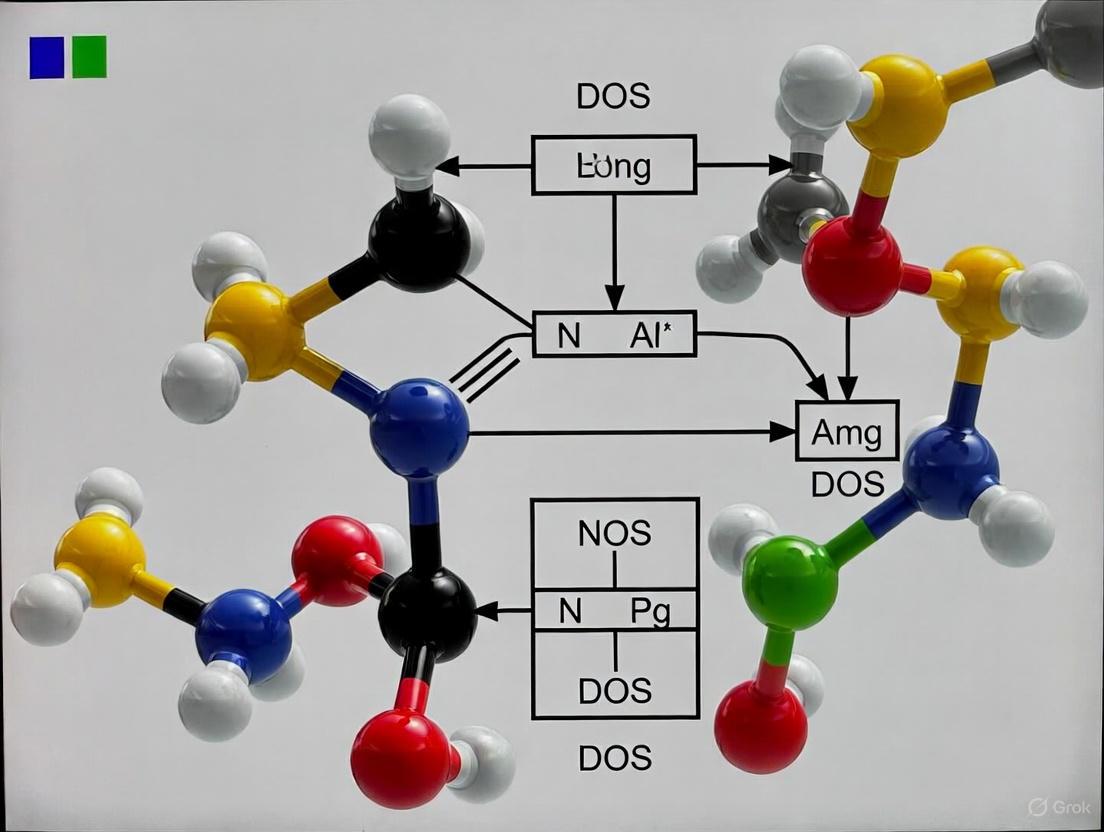

Diagnostic Workflow The following diagram outlines the logical steps to diagnose and resolve a band structure-DOS mismatch.

Resolution Steps

- Verify the k-point grid for DOS: The DOS is calculated using the same k-grid as your self-consistent field (SCF) calculation. If this grid is too coarse, the DOS will be inaccurate. Systematically increase the k-point density for the SCF/DOS calculation and monitor the convergence of the total energy and the band gap [7] [12].

- Check the band structure path: Confirm that the high-symmetry path used for the band structure plot passes through the points in the Brillouin zone where the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) are actually located. The band structure can only show the gap along the specific path it calculates [1].

- Understand the methods: Recognize that the "interpolation method" used for DOS integration over the entire BZ is often more reliable for finding the true fundamental gap than the "band structure method," which is restricted to a specific path [1]. The gap printed in the main output file (often from the interpolation method) is typically more trustworthy than one estimated from a band structure plot.

Problem: Total Energy Fails to Converge with k-points

Issue Description The total energy of the system does not stabilize as the k-point grid is densified, a problem particularly acute in metallic systems [9].

Resolution Steps

- Switch to a generalized k-point grid: Standard Monkhorst-Pack (MP) grids may not provide the most efficient symmetry reduction. Using generalized regular (GR) grids or grids from modern algorithms (e.g., from the Mueller Group's K-Point Grid Server) can provide better convergence with fewer irreducible k-points, accelerating calculations by a factor of about 2 on average [13] [9].

- Use the tetrahedron method for metals: For metallic systems, the Blöchl-corrected tetrahedron integration method is highly recommended. It can converge the single-particle sum to within a few μRy by improving the error scaling from ( O(n^{-2}) ) to ( O(n^{-4}) ) or better for simple bands [8].

- Employ smearing techniques: Gaussian (Methfessel-Paxton) or Fermi-Dirac smearing can be used to smooth the Fermi-level discontinuity. While this introduces a small finite temperature, it significantly improves convergence behavior with the k-point grid [8].

- Exploit symmetry for specific materials: In some systems, like graphene, including a specific high-symmetry k-point (e.g., the K-point) in your sampling can be more important than using a generally dense grid. This can perfectly pin the Fermi level at the Dirac cone, even with a relatively coarse grid that includes that point [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic k-point Convergence Test

Objective To determine the minimally sufficient k-point grid that yields a total energy converged to within a target accuracy (e.g., 1 meV/atom).

Materials and Reagents

- Software: A DFT code such as SIESTA [7], VASP [10], or Questaal [8].

- System: The crystal structure of interest (e.g., Silicon in a diamond structure) [10].

Methodology

- Initial Setup: Begin with a structurally relaxed system and a well-converged basis set or plane-wave cutoff.

- Grid Generation: Start with a coarse Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid (e.g., 2×2×2). The grid can be defined manually or using an automated parameter like

kgridcutoff[7]. - Calculation Series: Perform a single-point energy calculation. Repeat the calculation, progressively increasing the k-point density (e.g., to 4×4×4, 6×6×6, 8×8×8, etc.) [7] [10].

- Data Collection: For each calculation, record the k-grid, the total number of k-points, and the total energy.

- Analysis: Plot the total energy as a function of k-point density or the inverse of the grid size. The energy is considered converged when the change (ΔE) between successive calculations is less than your target threshold [10].

Protocol 2: Resolving Band Gap Mismatch

Objective To obtain a consistent and accurate band gap value from both DOS and band structure calculations.

Materials and Reagents

- Software: A DFT code with separate options for SCF k-grid and band structure k-path.

- System: A semiconductor or insulator (e.g., Silicon).

Methodology

- Converge the SCF k-grid: First, follow Protocol 1 to find a k-grid that converges the total energy. This grid will be used for the DOS calculation.

- Perform a DOS Calculation: Using the converged k-grid, calculate the DOS. Use the tetrahedron method or a small smearing for insulators. Note the band gap from the DOS.

- Calculate the Band Structure: Generate a band structure along a high-symmetry path. Ensure the path is dense (many points between high-symmetry points) and includes all critical points where the VBM and CBM are suspected to be.

- Cross-Reference Results: Compare the gap from the DOS with the gap observed on the band structure plot. The DOS gap is typically more reliable. If they disagree, it is likely the band path does not intersect the true CBM and/or VBM. Consult literature to confirm the location of the CBM/VBM and adjust your band path accordingly [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Tool / Reagent | Function in k-point Sampling |

|---|---|

| Monkhorst-Pack Grids | A systematic method to generate uniform k-point meshes for sampling the Brillouin zone. It is the most common and traditional approach [7]. |

| Generalized Regular (GR) Grids | Advanced k-point grids that can provide better symmetry reduction than standard MP grids, leading to fewer irreducible k-points and faster calculations for the same accuracy [9]. |

| Tetrahedron Method | An integration technique that divides the Brillouin zone into tetrahedra. It is particularly accurate for metals, especially when enhanced with Blöchl corrections [8]. |

| Smearing Methods | Techniques (e.g., Methfessel-Paxton, Fermi-Dirac) that broaden occupational states around the Fermi level. This smoothens integrands, accelerating SCF convergence in metals at the cost of a small, controlled error [8]. |

| K-point Grid Servers | Online tools (e.g., Mueller Group's Server) that generate highly efficient, optimized k-point grids for a given crystal structure, streamlining the setup process [13]. |

How Smearing Methods and Energy Grids Affect Spectral Resolution

Core Concepts & Definitions

What are smearing methods and why are they used?

Smearing methods, also known as broadening techniques, are computational algorithms used in electronic structure calculations to determine the fractional occupation of electronic states near the Fermi level. In first-principles calculations of metallic systems, the binary occupation of states (fully occupied or completely empty) can lead to numerical instabilities and slow convergence. Smearing techniques introduce a small amount of "smearing" around the Fermi energy, which allows for fractional occupation numbers and significantly improves the convergence behavior of self-consistent field (SCF) cycles, particularly for metals [14].

What is the energy grid and how does it affect spectral resolution?

The energy grid refers to the discrete set of energy points at which the Density of States (DOS) is calculated. The parameter DOS%DeltaE in many computational codes controls the spacing between these energy points [1]. A finer energy grid (smaller DeltaE) provides higher resolution in the DOS, allowing for better identification of sharp spectral features, van Hove singularities, and narrow band gaps. Conversely, a coarser grid can miss these fine details, leading to inaccurate representations of the electronic structure.

Troubleshooting Guides

Band structure does not match the DOS

Problem Description: Researchers often encounter a discrepancy where the electronic band structure plot does not align with the features observed in the Density of States (DOS). Key features, such as band edges or peaks, appear at different energies in the two representations [1].

Diagnosis Flowchart:

Step-by-Step Resolution Protocol:

Verify K-Space Integration Quality: The DOS is derived from a k-space integration method that interpolates bands across the entire Brillouin Zone (BZ), while the band structure is plotted along a specific high-symmetry path. A mismatch is often caused by an unconverged

KSpace%Qualityparameter.- Action: Systematically increase the

KSpace%Qualitysetting and rerun the DOS calculation. A sufficiently high quality should make the DOS features consistent with the band structure, provided the path covers all relevant features [1].

- Action: Systematically increase the

Refine the DOS Energy Grid: A coarse energy grid can blur sharp features in the DOS.

- Action: Decrease the value of

DOS%DeltaEto obtain a finer energy grid for the DOS calculation. This improves the resolution and may reveal features that were previously smeared out [1].

- Action: Decrease the value of

Check Band Path Coverage: The band structure plot is only as good as the chosen path in the BZ. It is possible that the top of the valence band (TOVB) or bottom of the conduction band (BOCB)—and thus the band gap—does not lie on this path.

- Action: Consult literature or use symmetry analysis to ensure your band path includes all critical points. The true band gap from the "interpolation method" (printed in the output file) is more reliable as it samples the entire BZ [1].

Choosing the correct smearing method

Problem Description: An inappropriate choice of smearing technique and width (SIGMA) can lead to incorrect total energies, unphysical occupation of band gaps, and inaccurate forces, which is particularly detrimental for geometry relaxations and phonon calculations [14].

Diagnosis Flowchart:

Step-by-Step Resolution Protocol:

Classify Your System: The optimal smearing method depends critically on whether the system is a metal, semiconductor, or insulator.

- Metals (for relaxations): Use the Methfessel-Paxton method (

ISMEAR=1in VASP). Choose aSIGMAvalue as large as possible while keeping the entropy termT*S(reported in the output file) negligible (e.g., < 1 meV/atom). A default ofSIGMA=0.2is often a reasonable starting point [14]. - Semiconductors/Insulators: Use Gaussian smearing (

ISMEAR=0) or the tetrahedron method (Blöchl corrections,ISMEAR=-5). Crucially, avoidISMEAR > 0as it can lead to unphysical occupation of the band gap and errors in forces exceeding 20% [14]. - Unknown Systems/High-Throughput: Gaussian smearing (

ISMEAR=0) with a smallSIGMA(0.03 to 0.1) is the safest and most recommended default [14].

- Metals (for relaxations): Use the Methfessel-Paxton method (

Converge

SIGMAfor Gaussian Smearing: When using Gaussian smearing, the total energy must be extrapolated toSIGMA=0. The output file typically reports an extrapolated value. Ensure that both the energy and the forces are converged with respect to a systematic reduction ofSIGMA[14].Use Tetrahedron for Final DOS: For the calculation of highly accurate total energies or the DOS on a converged structure, use the tetrahedron method (

ISMEAR=-5) with a dense k-point mesh. This method provides a sharper representation of band edges compared to smearing methods [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I see two different band gaps reported in my output. Which one should I trust? A1: This discrepancy arises from two different evaluation methods. The "interpolation method" (used for k-space integration and the gap printed in the main output) samples the entire Brillouin Zone and is generally more reliable. The "band structure method" only evaluates energies along a specific path. While the latter can use a denser k-point sampling along the path, it relies on the assumption that the band edges lie on that path. For a definitive answer, the gap from the interpolation method is preferable, but the band structure method can confirm the location of the extrema [1].

Q2: My SCF calculation will not converge, especially for a metallic system. How can smearing help?

A2: Smearing is specifically designed to address SCF convergence in metals. By allowing fractional occupations near the Fermi level, it prevents large, discontinuous changes in orbital occupations between SCF cycles, which is a primary source of charge sloshing and divergence. Switching from the default ISMEAR=-5 (tetrahedron) to ISMEAR=1 (Methfessel-Paxton) or ISMEAR=0 (Gaussian) with an appropriate SIGMA is often the key to achieving convergence in metallic systems [14]. Other stabilizing measures include decreasing the mixing parameter and using the MultiSecant or LIST DIIS methods [1].

Q3: Why are my phonon frequencies imaginary (negative)? Could this be related to smearing?

A3: Yes, the choice of smearing can indirectly cause imaginary frequencies. The two most common causes are: 1) The geometry is not fully optimized to a minimum, and 2) The numerical accuracy of the forces used for the phonon calculation is insufficient. Using an overly large SIGMA or an inappropriate smearing method (e.g., ISMEAR>0 for an insulator) can lead to inaccurate forces and, consequently, unphysical phonon spectra. Always ensure your geometry is fully converged and that your smearing method is appropriate for your system to obtain reliable forces [1] [14].

Q4: For a system that is difficult to converge, should I use a finite electronic temperature?

A4: Yes, applying a finite electronic temperature (i.e., Fermi-Dirac smearing, ISMEAR=-1) can significantly improve SCF convergence, much like other smearing techniques. This is often employed in automated workflows during the initial stages of a geometry optimization when forces are still large. The electronic temperature can be set high initially and then automatically reduced as the geometry converges, ensuring accuracy in the final energy [1].

Table 1: Smearing Method Comparison and Guidelines

Smearing Method (VASP ISMEAR) |

Best For System Type | Recommended SIGMA |

Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages/Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Gaussian (ISMEAR=0) |

Unknown, Semiconductors, Insulators | 0.03 - 0.1 | Safe default; provides energy(SIGMA→0) extrapolation [14]. |

Forces/stress are consistent with free energy, not extrapolated energy [14]. |

Methfessel-Paxton (ISMEAR=1) |

Metals (for relaxations, forces, phonons) | Set so that T*S < 1 meV/atom [14]. |

Very accurate total energies for metals; corrects for entropy term [14]. | Avoid for semiconductors/insulators; can cause severe errors [14]. |

Fermi-Dirac (ISMEAR=-1) |

Finite-temperature properties | Corresponds to electronic temperature | Physically meaningful for real temperature effects [14]. | Other methods are often preferred for ground-state calculations [14]. |

Tetrahedron + Blöchl (ISMEAR=-5) |

Semiconductors, Insulators; Metals (for accurate DOS/final energy) | Not Applicable | Most accurate for DOS and total energies in bulk materials; sharp band edges [14]. | Forces can be wrong (5-10%) for metals; not variational [14]. |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Spectral Resolution Control

| Parameter | Typical Function | Effect on Spectral Resolution | Recommended Starting Value |

|---|---|---|---|

SIGMA |

Smearing width (eV) | Larger values smear out spectral features, lower resolution but improve metal SCF convergence [14]. | 0.1 (Gaussian), 0.2 (Methfessel-Paxton for metals) [14]. |

DOS%DeltaE |

Energy grid spacing (eV) | Smaller values give higher resolution DOS, revealing sharp features [1]. | System-dependent; must be converged. |

KSpace%Quality |

k-point mesh density | Finer mesh improves BZ sampling, essential for matching DOS and band structure [1]. | System-dependent; must be converged. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Parameters

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for Band Structure and DOS Calculations

| Item / Parameter | Function / Role | Example "Solution" / Value |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing Function | Determines fractional occupancy of states near Fermi level; critical for SCF convergence in metals. | Gaussian (ISMEAR=0), Methfessel-Paxton (ISMEAR=1), Tetrahedron (ISMEAR=-5) [14]. |

Smearing Width (SIGMA) |

Controls the energy width over which states are smeared; a key convergence parameter. | 0.1 eV (Gaussian default), 0.2 eV (Methfessel-Paxton for metals) [14]. |

k-point Mesh (KSpace%Quality) |

Defines the sampling of the Brillouin Zone; affects accuracy of integration for DOS and charge density. | "Good" or "High" quality setting; must be converged for the system [1]. |

Energy Grid (DOS%DeltaE) |

Sets the energy resolution for the DOS calculation; finer grid captures sharp features. | A small value (e.g., 0.01 eV); must be tested for convergence [1]. |

Fermi Energy Setting (EFERMI) |

Determines the reference energy (0 eV) for band structures and DOS. | MIDGAP (for gapped systems), LEGACY (default, can be unstable) [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Band Structure and DOS Mismatch

This guide addresses common computational and experimental challenges researchers face when investigating the band structure and density of states (DOS) in materials like anatase TiO₂ and doped MgF₂.

FAQ: Resolving Discrepancies Between Calculated and Experimental Band Gaps

Q: My DFT-calculated band gap for anatase TiO₂ is significantly smaller than the experimental value (3.2 eV). What is the cause and how can I resolve this?

- A: This is a known limitation of standard DFT functionals (LDA, GGA), which underestimate band gaps. To address this:

- Use advanced exchange-correlation functionals: Employ the Hubbard +U model (DFT+U) to account for strong electron correlations. For TiO₂, a U value of 8.2 eV applied to Ti 3d orbitals has been used successfully to yield a band gap of 3.14 eV, close to the experimental value [15] [16].

- Consider hybrid functionals: Functionals like HSE06 incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, which typically opens up the band gap to more experimental values.

- Ensure convergence: Verify that your plane-wave cutoff energy and k-point sampling are well-converged. For anatase TiO₂, a 4×4×4 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid has been shown to provide good convergence for the total energy [17].

Q: The projected DOS (PDOS) for my doped system shows unexpected peaks deep in the band gap. Are these physical or a sign of an error?

- A: Deep gap states can be physical, originating from certain types of defects or dopants, but they can also indicate problematic computational settings.

- Identify the dopant's role: Metallic dopants like Cr or Fe in TiO₂ can introduce deep levels, while non-metallic dopants like F often create shallower states [16]. In MgF₂, Co²⁺ doping introduces a ground state level about 2 eV above the valence band maximum [18].

- Check for spurious interactions: If using a supercell model for doping, ensure the defect concentration is not artificially high, which can lead to interactions between periodic images of the dopant. Increase your supercell size to dilute the dopant concentration and check if the gap states persist.

- Verify dopant stability: Confirm the most stable configuration for your dopant. For F in TiO₂, substitutional doping (replacing an oxygen atom) is often more energetically favorable than interstitial doping [15].

Q: My band structure plot shows unphysical spikes or discontinuities. What could be wrong?

- A: This is often related to the k-point path used in the non-self-consistent field (NSCF) calculation.

- Ensure a connected path: The k-points for the band structure calculation must be defined along a continuous, high-symmetry path in the Brillouin zone. A common path for anatase TiO₂ is Z → Γ → X → P [17] [19].

- Use sufficient points: Between high-symmetry points, use an adequate number of k-points (e.g., 20-50) to ensure a smooth band dispersion [17].

FAQ: Challenges in Doping and Defect Engineering

Q: I am synthesizing F-doped TiO₂, but my material does not show the expected red-shift in absorption or improved photocatalytic activity. What might have gone wrong?

- A: The effectiveness of F-doping depends heavily on the successful incorporation of F atoms into the TiO₂ structure and their specific coordination.

- Confirm F incorporation and configuration: Use XPS to check the chemical state of F. Two XPS peaks in the F1s region (~684 eV for Ti-F bonds and ~688 eV for surface-adsorbed F) indicate successful doping [20]. The most active configuration for visible-light response is often the surface Ti₃-F species [20].

- Optimize synthesis parameters: The doping concentration is critical. For TiO₂ nanorods, a precursor concentration of 0.05 mol/L NH₄F was optimal, yielding a photocurrent 4.61 times higher than pure TiO₂. Higher concentrations can be detrimental [21].

- Check for charge compensation: Doping can introduce charge imbalances that are compensated by native defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies), which may themselves alter the electronic structure.

Q: When I computationally model doped MgF₂, how do I achieve a reliable band gap for the host material?

- A: Pure MgF₂ is a wide-band-gap insulator, and standard DFT severely underestimates its gap.

- Incorporate exact exchange: As demonstrated in studies of Co-doped MgF₂, including a portion of non-local exact exchange is crucial for properly reproducing the band gap and other bulk properties [18]. Hybrid functionals (e.g., PBE0, HSE) are recommended for this class of materials.

Table 1: Band Gap Modification in Doped Anatase TiO₂

| Material System | Dopant Type/Concentration | Calculation Method | Band Gap (eV) | Key Change vs. Pure TiO₂ | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Anatase TiO₂ | - | DFT+U (U=8.2) | 3.14 [15] | Reference | ~3.2 eV [15] |

| F:Hi:TiO₂ | F, H Interstitial | DFT+U | 3.00 [15] | -0.14 eV | ~3.0 eV [15] |

| Fo:Hi:TiO₂ | F (Substitutional), H | DFT+U | 2.60 [15] | -0.54 eV | Not Specified |

| Cl-doped TiO₂ | Cl | DFT+U | Significant Reduction [15] | Introduction of gap states | Enhanced H₂ production rate [15] |

| F-doped TiO₂ Nanorods | F (0.05M NH₄F) | Experimental (UV-Vis) | Optimized [21] | Red shift & improved absorption | 6.58x higher H₂ production [21] |

Table 2: Electronic Structure of Doped MgF₂ and Other Modifications

| Material System | Dopant/Modification | Calculation Method | Key Electronic Finding | Experimental Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure MgF₂ | - | Ab initio (with non-local exchange) | Properly reproduced band gap [18] | Reliable baseline for calculations [18] |

| Co:MgF₂ | Co²⁺ (3d⁷) | Ab initio | Ground state level ~2 eV above valence band top [18] | Good agreement with experimental data [18] |

| Anatase under Strain | 8 GPa Biaxial Tensile Strain | DFT+U | Band gap reduction to 2.96 eV [16] | Epitaxial growth on lattice-mismatched substrates [16] |

| Cr-doped Anatase under Strain | Cr + 8 GPa Strain | DFT+U | Band gap reduction to 2.4 eV [16] | Not Specified |

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To synthesize fluorine-doped TiO₂ nanorod arrays (F-T) on FTO glass for enhanced photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting.

Materials:

- Substrate: Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) conductive glass.

- Precursors: Tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT), concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%).

- Dopant Source: Ammonium fluoride (NH₄F) solutions (0.01, 0.05, 0.1 mol/L).

- Solvents: Acetone, ethanol, deionized water.

Procedure:

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean FTO glass via ultrasonication in acetone, ethanol, and deionized water for 30 minutes each. Dry under a nitrogen stream.

- Hydrothermal Growth:

- Mix deionized water and concentrated HCl in a 1:1 volume ratio.

- Slowly add 0.6 ml of TBOT to the acid solution under vigorous stirring until the solution becomes clear.

- Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and place the cleaned FTO glass inside, conductive side facing up.

- Heat the autoclave at 170 °C for 6 hours in an oven.

- After cooling, remove the FTO substrate, now coated with a white TiO₂ film, and rinse with ultrapure water.

- Fluorine Doping:

- Soak the as-grown, unannealed TiO₂ nanorod array in an NH₄F solution (e.g., 0.05 mol/L) for 5 minutes.

- Remove the sample, discard excess solution, and dry with a nitrogen stream.

- Annealing: Place the sample in a tubular furnace and anneal at 450 °C for 1 hour under an argon atmosphere.

Characterization & Validation:

- PEC Performance: Use a standard 3-electrode system (e.g., CHI 760E electrochemical workstation) to measure photocurrent density. Optimally doped samples (0.05F-T) show a photocurrent of 7.34 mA/cm² at 1.8 V vs. RHE [21].

- Hydrogen Production: Measure H₂ evolution under illumination. A 6.58-fold increase over pure TiO₂ is indicative of successful doping [21].

- Structural Analysis: Use XRD and TEM to confirm the anatase phase and successful F incorporation, which may manifest as changes in lattice spacing [21].

Objective: To calculate the electronic band structure, total DOS, and projected DOS (PDOS) of a periodic system like anatase TiO₂ using DFTB+.

Procedure:

- Ground-State Calculation (Self-Consistent Charge):

- Geometry: Provide the crystal structure in GenFormat, specifying fractional coordinates.

- Hamiltonian: Set

SCC = Yeswith a tight tolerance (e.g.,SccTolerance = 1e-5). Use appropriate Slater-Koster files (e.g.,mioset). - k-Points: Use a dense Monkhorst-Pack grid (e.g.,

4x4x4generated viaSupercellFolding) to obtain converged charges. - PDOS Setup: In the

Analysisblock, useProjectStatesto define regions (e.g.,Atoms = TiandAtoms = O) withShellResolved = Yesto output PDOS for individual atomic shells. - Execution: Run DFTB+ to generate

band.outand PDOS files (e.g.,dos_ti.1.dat,dos_o.1.dat).

- Band Structure Calculation (Non-SCC):

- Input Charges: Copy the

charges.binfile from the previous step and setReadInitialCharges = Yes. - k-Points Path: Use the

Klinesmethod to define a path through high-symmetry points (e.g., Z, Γ, X, P for anatase), specifying the number of points between each. - Execution: Run DFTB+ with

MaxSCCIterations = 1to calculate eigenvalues along the specified path.

- Input Charges: Copy the

Post-Processing:

- Total DOS: Use

dp_dos band.out dos_total.datto generate the total DOS file. - PDOS: Use

dp_dos -w dos_ti.1.out dos_ti.s.dat(with the-wflag for weighting) to generate the PDOS for each atomic shell and species.

Conceptual Diagrams

F-TiO2 Synthesis and Effect Diagram

Diagram 1: F-TiO2 synthesis workflow and effects.

DOS Mismatch Troubleshooting Logic

Diagram 2: DOS mismatch troubleshooting logic.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for TiO₂ and MgF₂ Doping Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Application Example | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Fluoride (NH₄F) | Fluorine dopant source for TiO₂. Introduces F ions that can substitute for O or adsorb on the surface. | Synthesis of F-doped TiO₂ nanorods for enhanced PEC water splitting [21]. | Concentration is critical (e.g., 0.05M optimal). Soaking time (5 min). |

| Tetrabutyl Titanate (TBOT) | Titanium precursor for the sol-gel and hydrothermal synthesis of TiO₂ nanostructures. | Hydrothermal growth of pristine TiO₂ nanorod arrays on FTO glass [21]. | Purity, controlled hydrolysis in acidic conditions (HCl). |

| Slater-Koster Files (mio, tiorg) | Parameter sets containing pre-computed integrals for DFTB calculations. Essential for electronic structure simulations. | DFTB+ calculation of band structure and PDOS for anatase TiO₂ [17]. | File path must be correctly specified in input. Must match element pairs (e.g., Ti-Ti, Ti-O, O-O). |

| FTO Conducting Glass | Transparent conducting oxide substrate. Serves as both the growth substrate and working electrode. | Growth of TiO₂ nanorod arrays for photoanode fabrication [21]. | Surface cleanliness prior to synthesis is paramount. |

| Cobalt Fluoride (CoF₂) | Source of Co²⁺ ions for doping wide-band-gap fluorides like MgF₂. | Ab initio studies of Co-doped MgF₂ crystals for defect energy level analysis [18]. | Purity, controlled incorporation during crystal growth. |

Robust Protocols for Converged Band Structure and DOS Calculations

Optimal k-point Grid Strategy for SCC Convergence and Band Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the two primary convergence parameters I must check in DFT calculations? For all first-principles calculations, you must pay attention to two key convergence issues: the planewave energy cutoff (ecutwfc), which limits the wave-function expansion, and the number of k-points, which determines how well your discrete grid approximates the continuous integral over the Brillouin zone [22].

Why is a k-point convergence study necessary? The convergence of properties like total energy and band gap with respect to k-point density is "neither variational nor necessarily monotonous" [23]. Therefore, systematically testing different k-grids is the only reliable method to ensure your results are converged for your specific system and property of interest.

I found two different band gap values in my output. Which one is correct? The band gap can be determined by two main methods [1]:

- The "interpolation method": This method uses the analytical k-space integration scheme that determines the Fermi level and occupations. The gap printed in the main output file (e.g., the

.kffile in BAND) typically comes from this method. - The "band structure method": This is a post-SCF method that calculates bands along a high-symmetry path. It often uses a denser k-point sampling along that path and is generally considered the better way to find the gap, provided the path contains both the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum.

Why does my band structure plot not match my Density of States (DOS)? This common problem can have several causes [1]:

- Different k-space sampling: The DOS is derived from an interpolation method that samples the entire Brillouin zone, while the band structure is plotted along a single line. They are fundamentally different representations.

- Unconverged DOS: The DOS may not be converged with respect to the

KSpace%Qualityparameter. Try increasing this value. - Insufficient energy grid: The energy grid for the DOS might be too coarse. You can make it finer using the

DOS%DeltaEparameter.

My SCF calculation will not converge. What can I do? SCF convergence problems, especially in metallic systems or slabs, can often be resolved with more conservative settings [1]:

- Decrease the

SCF%Mixingparameter and/or theDIIS%Dimixparameter. - Try alternative SCF methods like the

MultiSecantmethod or theLISTivariant of the DIIS method. - For geometry optimizations, use "automations" to start with a higher electronic temperature and looser SCF criteria, which are then tightened as the geometry converges.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Band Structure and DOS Mismatch

Issue: The features in your calculated density of states (DOS) do not align with the expected energy levels from your band structure plot.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Verify k-space quality: The most common cause is that the DOS is not converged with respect to the k-point grid. The DOS requires a dense, uniform grid to accurately integrate over the entire Brillouin Zone, whereas the band structure uses a dense sampling along a specific path [1].

- Action: Systematically increase the

KSpace%Qualityparameter (or equivalent in your code) and rerun the DOS calculation. The results are converged when the DOS no longer changes significantly with a finer k-grid.

- Action: Systematically increase the

Check the band path: The band structure plot is only as good as the path chosen through the Brillouin Zone. It is possible that the chosen path misses the specific k-points where the valence band maximum or conduction band minimum occur [1].

- Action: Ensure your band structure path includes all high-symmetry points. You may need to consult literature for your specific crystal structure to identify the correct path.

Refine the DOS energy grid: A coarse energy grid can smear out sharp features in the DOS.

- Action: Decrease the value of

DOS%DeltaEto use a finer energy grid for calculating the DOS [1].

- Action: Decrease the value of

Problem: Significant Mismatch in Band Gap Values

Issue: Different methods or classes within your computational code report significantly different band gap values (e.g., a difference of 0.27 eV for Silicon) [11].

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Identify the source: Understand which method each reported gap comes from. As outlined in the FAQ, the gap from the

Bandstructureobject and theDosobject are computed differently [11] [1]. - Trust the band structure method: For determining the fundamental band gap, the "band structure method" is often more reliable as it can use a much denser sampling along a path to pinpoint critical points [1].

- Ensure consistency: For a valid comparison, both the band structure and DOS calculations must be based on the same self-consistent density and potential. Always use a well-converged SCF calculation as the starting point for both.

K-Point Convergence: Data and Protocols

The following table exemplifies the results of a k-point convergence study for a solid-state system, showing how total energy and band gap evolve with an increasingly dense k-grid [23].

Table 1: Example K-Point Convergence Data

| k-grid | k-point Density | Total Energy (eV) | Band Gap (eV) | Converged? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2x2x2 | 1.01 | -7900.073544 | 0.67 | True |

| 4x4x4 | 2.01 | -7901.237159 | 0.77 | True |

| 6x6x6 | 3.02 | -7901.317293 | 0.78 | True |

| 8x8x8 | 4.02 | -7901.327057 | 0.67 | True |

| 10x10x10 | 5.03 | -7901.328599 | 0.64 | True |

| 12x12x12 | 6.03 | -7901.328883 | 0.64 | True (1.0E-04 eV/atom) |

| 16x16x16 | 8.04 | -7901.328954 | 0.64 | True (1.0E-05 eV/atom) |

| 18x18x18 | 9.05 | -7901.328957 | 0.65 | True (1.0E-06 eV/atom) |

This data shows that while the total energy converges monotonically, the band gap can oscillate (e.g., between 0.78 eV and 0.67 eV) before stabilizing, underscoring the need for thorough testing [23].

Experimental Protocol: K-Point Convergence Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the recommended workflow for performing a k-point convergence study.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Preparation: Start with a fully optimized crystal structure and a converged planewave energy cutoff.

- Grid Selection: Define a series of increasingly dense k-point grids (e.g., 2x2x2, 4x4x4, 6x6x6, ...). Automated workflows like the

KPointConvergenceclass inaimstoolscan facilitate this task [23]. - Execution: Perform self-consistent field (SCF) calculations for each defined k-point grid.

- Data Extraction: For each calculation, extract the property of interest—most commonly the total energy per atom and the fundamental band gap.

- Convergence Analysis: Plot the property values against the k-point density or grid size. The property is considered converged when its change with a denser grid falls below a predefined threshold. Common thresholds are:

- 1.0E-04 eV/atom: For sparse k-grids, suitable for initial geometry optimizations.

- 1.0E-05 eV/atom: For relatively dense k-grids, used in production calculations.

- 1.0E-06 eV/atom: For very dense k-grids, typically needed for metallic systems and optical spectra [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Inputs

| Item / Software Code | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO (PWSCF) | A full ab initio package for electronic structure, energy calculations, and linear response methods using plane waves and pseudopotentials [22]. |

| VASP | A widely used DFT code implementing the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method and ultrasoft pseudopotentials [22]. |

| KPointConvergence Workflow (aimstools) | An automated utility to set up, run, and evaluate k-point convergence studies [23]. |

| ecutwfc | The key input parameter in PWSCF that sets the kinetic energy cutoff (in Rydberg) for the plane-wave basis set, controlling the quality of the wavefunction expansion [22]. |

| K_POINTS automatic | The input parameter in PWSCF to define the Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid (e.g., 4 4 4 0 0 0 for a 4x4x4 grid) [22]. |

| KSpace%Quality | A parameter in the BAND code that controls the density of the k-grid used for Brillouin Zone integration; crucial for converging the DOS [1]. |

Why is there a mismatch between my DOS and band structure results?

A mismatch between your Density of States (DOS) and band structure can occur because they are typically calculated using different methods and k-space sampling. The DOS is often computed via a method that interpolates over the entire Brillouin Zone (BZ), while the band structure is calculated along a high-symmetry path using a much denser k-point sampling [1]. If the k-grid for the DOS is not sufficiently converged, it might inaccurately determine the band edges (Valence Band Maximum and Conduction Band Minimum), leading to a different band gap value compared to the band structure plot [11].

How can I restart a calculation to improve the DOS?

You can recalculate the DOS with improved parameters, such as a denser k-grid, without restarting the full Self-Consistent Field (SCF) calculation. This is an efficient way to enhance the quality of your results [24].

Required Materials and Software

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| AMS/BAND Software | Software suite used for performing DFT calculations, including SCF, DOS, and band structure tasks. |

| Previous Calculation Results (.rkf file) | The output file from a prior SCF calculation; serves as the restart point for the new DOS calculation. |

| Input File Script | A text file specifying the new calculation parameters, such as a denser k-grid. |

| Linux/Unix Terminal | Environment for executing the AMS/BAND commands. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Locate Your Previous Results: Ensure you have the

.rkffiles from a previously converged SCF calculation. - Create a New Input File: Prepare an input file that loads the original atomic system and restarts from the previous SCF calculation. The key is to specify

Dos trueandBandStructure truewithin theRestartblock, and to define a new, denser k-grid [24]. - Execute the Calculation: Run the new calculation using the command

$AMSBIN/ams --delete-old-results < your_new_input_file.run[24].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for restarting a DOS calculation:

What specific input settings should I use?

Below is a sample input script that demonstrates the restart procedure. The critical section is the Restart block, which instructs the code to use the potential from a previous calculation and only recalculate the DOS and band structure.

Example Input Script

Key Parameter Comparison

| Parameter | Common Default | Improved Setting for Convergence | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

KSpace%Quality |

Normal |

Good or VeryGood |

Increases the number of k-points in the grid for better BZ sampling [1]. |

KSpace%Regular%DoubleCount |

Not set | 1 |

A simple way to double the density of the k-grid used in the previous calculation [24]. |

DOS%DeltaE |

Default value | A smaller value (e.g., 0.005) |

Makes the energy grid for the DOS finer, which can reveal sharper features [1]. |

BandStructure%EnergyBelowFermi |

~10 Hartree |

A larger value (e.g., 10000) |

Ensures that deep-lying core bands are included in the band structure plot [1]. |

How do I verify that my new DOS is converged?

After running the new calculation, you should check the consistency of your results.

- Compare Band Gaps: Systematically compare the band gap value printed in the output file (from the k-space integration method) with the gap observed from the band structure plot [11]. They should be in much closer agreement.

- Visual Inspection: Plot the new DOS and the band structure on the same energy scale. The peaks in the DOS should align with the flat regions in the band structure.

- Quantitative Check: Use scripting tools, like the

comparekf.pyscript mentioned in the documentation, to perform a dot-product comparison between the total DOS of your old and new calculations. A high similarity score indicates a well-converged DOS with respect to the k-grid [24].

Basis Set Selection and Confinement to Address Linear Dependency

FAQ: Understanding Linear Dependency

What is linear dependency in a basis set? In computational chemistry, a basis set is a set of functions used to represent molecular orbitals. Linear dependency occurs when one basis function can be represented as a linear combination of other functions in the set [25]. This makes the basis set over-complete and leads to numerical instability, causing slow or erratic Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence and inaccurate results [1] [26].

How is linear dependency detected? Programs detect linear dependency by analyzing the overlap matrix (a matrix of integrals representing the overlap between basis functions). The presence of very small eigenvalues in this matrix indicates near-linear-dependency [1] [26]. Most software will automatically project out these near-degeneracies if the eigenvalues fall below a default threshold, typically around 1×10⁻⁶ [26].

Why does my calculation have linear dependencies? Linear dependencies often arise from two main scenarios:

- Large, diffuse basis sets: Using very large basis sets, especially those with many diffuse functions (e.g.,

aug-cc-pV9Z), increases the chance of functions being numerically similar [27] [26]. This is common in calculations on anions or excited states. - Systems with high coordination: In periodic systems like slabs or bulk materials, the basis functions of atoms in the inner layers can become overly diffuse, leading to dependencies with functions from neighboring atoms [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Linear Dependency

Issue: Calculation fails with a "dependent basis" error message. This error indicates the program has identified a linear dependency it cannot safely ignore. Do not immediately relax the default tolerance; instead, adjust your basis set [1].

Solution 1: Apply Confinement Confinement reduces the spatial extent of basis functions, which is especially useful for atoms in the interior of a system (like a slab) where diffuse functions are not needed.

- Methodology: In the SCM BAND code, use the

Confinementkey to apply a radial potential that curtails the tail of the basis functions. The documentation suggests applying confinement to inner-layer atoms while using normal basis functions on surface atoms to properly describe electron density decay into vacuum [1].

- Methodology: In the SCM BAND code, use the

Solution 2: Manually Remove Problematic Functions If confinement is not sufficient or applicable, you can manually remove specific basis functions that cause dependencies.

- Methodology: A practical approach is to identify and remove basis functions with exponents that are very similar in value. As demonstrated in a case study, the pairs of exponents with the smallest percentage difference (e.g.,

94.8087090and92.4574853342) are often the primary culprits [27]. Removing one function from each of the N most similar pairs can cure N overly low eigenvalues in the overlap matrix [27].

- Methodology: A practical approach is to identify and remove basis functions with exponents that are very similar in value. As demonstrated in a case study, the pairs of exponents with the smallest percentage difference (e.g.,

Solution 3: Use an Automated A Priori Method For a more robust and general solution, use a method based on the pivoted Cholesky decomposition of the overlap matrix.

Solution 4: Adjust the Dependency Threshold (Use with Caution) As a last resort, you can tighten the threshold for identifying linear dependencies.

- Methodology: In Q-Chem, this is controlled by the

BASIS_LIN_DEP_THRESH$remvariable. A lower value (e.g.,5for a threshold of 1×10⁻⁵) removes fewer functions but risks numerical instability. The default value of6(1×10⁻⁶) is generally reliable [26]. In ADF, theDEPENDENCYblock andtolbasparameter can be used for similar control [28].

- Methodology: In Q-Chem, this is controlled by the

Issue: SCF convergence is slow or unstable, and I suspect linear dependency.

- Solution: First, try more conservative SCF convergence settings, such as decreasing the mixing parameter [1]. If problems persist, check your basis set for linear dependency using the methods above. Starting the SCF calculation with a smaller basis set (e.g., SZ) and then restarting with a larger one can also help [1].

Advanced Context: Connection to Band Structure and DOS Mismatch

Linear dependency in the basis set is a potential root cause of discrepancies between different electronic structure analyses, such as a mismatch between the band gap calculated from a band structure plot and that derived from the Density of States (DOS) [11].

The DOS is typically computed by sampling the entire Brillouin Zone (BZ) using an interpolation method, while a band structure plot is calculated along a specific high-symmetry path [1]. An inadequate or unstable basis set, potentially suffering from linear dependencies, can lead to an inaccurate representation of the electronic potential. This inaccuracy can cause inconsistencies between the two methods, as they probe the electronic structure differently. Therefore, ensuring a robust, non-linearly-dependent basis set is a critical step in troubleshooting band structure and DOS mismatches.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and parameters relevant to managing basis set linear dependency.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Confinement Potential | Applies a radial potential to reduce the spatial extent of basis functions, curing dependencies in periodic systems [1]. | Defined by a radius and potential shape. Particularly useful for inner atoms in slabs/bulk. |

| Pivoted Cholesky Decomposition | An automated algorithm to identify and remove linearly dependent functions from a basis set before integral calculation [27]. | Available in ERKALE, Psi4, PySCF. More robust than manual removal. |

Dependency Threshold (tolbas, BASIS_LIN_DEP_THRESH) |

Numerical tolerance for identifying linear dependencies via the overlap matrix eigenvalues [28] [26]. | Default: ~1e-6. Warning: Increasing tolerance (e.g., to 1e-5) can help SCF converge but may affect accuracy [26]. |

| Overlap Matrix | The fundamental matrix used to diagnose linear dependence; its eigenvalues indicate the degree of dependency [1] [26]. | Smallest eigenvalues are checked against the threshold. Cheap to compute. |

Experimental Protocol: Basis Set Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for diagnosing and resolving basis set linear dependency issues.

Workflow for Addressing Basis Set Linear Dependency

Partial DOS Projection for Orbital-Resolved Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between total DOS and projected DOS (PDOS)? The total Density of States (DOS) describes the total number of available electronic states per energy level in a material, summed over all atoms and orbitals [29]. The projected DOS (PDOS) provides a more detailed breakdown, showing the contribution to the total DOS from specific atoms, specific orbitals (e.g., s, p, d), or specific spins [29] [3]. This allows you to understand which atomic species and orbitals are responsible for specific features in the electronic structure, such as the valence or conduction band edges [3].

Q2: Why are my PDOS results inconsistent with my total DOS? Inconsistencies between PDOS and total DOS can arise from several common setup errors:

- Insufficient k-point sampling: Using a sparse k-point mesh during the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation or the non-SCF DOS calculation can lead to poor quality and non-reproducible PDOS [30]. It is standard practice to use a denser k-point grid for DOS/PDOS calculations than for the initial SCF convergence [30].

- Incorrect orbital projection settings: Ensure that the parameters for projecting onto atoms or orbitals (e.g.,

natsph,iatsphin ABINIT, or theProjectStatesblock in DFTB+) are correctly declared if you are targeting specific species [30]. - File handling error: When performing a multi-step calculation, you must correctly transfer the self-consistent charges from the ground-state calculation to the band structure/DOS calculation. For instance, in DFTB+, you need to copy the

charges.binfile and setReadInitialCharges = Yes[3].

Q3: How can I check the available orbital projections for my system?

Most software packages provide ways to list all possible projection selections. For example, in VASP's py4vasp interface, you can use the selections() method to get a list of all available atoms and orbitals for projection [29]:

Q4: Can I perform spin-resolved PDOS analysis for magnetic materials?

Yes, most modern DFT codes support spin-polarized calculations and can output spin-resolved PDOS. The selection syntax typically includes options for up, down, or total spin [29]. For instance, in ABINIT, you can use prtdos 3 in a spin calculation to obtain the projected DOS for each spin channel [30].

Q5: What does a "negative" Local Partial Density of States mean? Recent research has revealed that in mesoscopic systems, certain objects in the DOS hierarchy, like the local partial density of states, can become negative in the presence of a Fano resonance [31]. This negativity can be interpreted as a loss of coherent electrons in reverse time and may have implications for the thermodynamic properties of these systems. It has been demonstrated that this phenomenon is correlated with a Fano resonance featuring a π phase drop [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Incorrect or No Orbital Projections in PDOS

Problem: The calculated PDOS is zero, does not appear, or does not match the expected contributions from specific atoms/orbitals.

Solution:

- Verify Projection Settings: Double-check the input file for the analysis block that enables PDOS.

- In DFTB+, this is done in the

Analysisblock usingProjectStatesandRegionto specify the atoms and whether the projection should be shell-resolved [3]. - In VASP, you must set

LORBITin theINCARfile to generate the projected DOS [29]. - In QuantumATK, you use the

ProjectedDensityOfStatesblock and choose the type of projection (e.g., onElements and Shells) [32].

- In DFTB+, this is done in the

- Confirm Selection Syntax: When querying the results, ensure you use the correct syntax. For example, in

py4vaspfor VASP, a valid selection for the d-orbitals of Mn, Co, and Fe is:"d(Mn, Co, Fe)"[29]. - Check Basis Set: Ensure that the basis set used in the calculation includes the orbitals you are trying to project onto. For example, if you want to project onto d-orbitals, the basis set for the relevant atoms must have d-orbitals defined [3].

Issue 2: Discontinuities and Poor Resolution in DOS/PDOS Spectra

Problem: The DOS plot looks jagged, non-smooth, or has unexpected spikes, making it difficult to interpret.

Solution:

- Increase k-points for DOS step: The most common solution is to perform a non-SCF calculation on a much denser k-point mesh than the one used for the SCF convergence.

- Use Gaussian Smearing: Apply a small Gaussian broadening (smearing) to the discrete energy levels to create a smooth DOS. Tools like

dp_dosin DFTB+ do this by default [3]. Adjust the smearing width carefully—a value that is too large will obscure important features, while one that is too small will not smooth the curve effectively. - Ensure Proper Energy Range: When plotting, specify a sufficiently wide energy range around the Fermi level to capture all relevant features. For materials with a large bandgap like SiO₂, you may need to inspect a range of -15 eV to +10 eV [32].

Issue 3: Fermi Level Mismatch Between Total DOS and PDOS

Problem: The Fermi energy reported in the total DOS file is different from that in the PDOS file, leading to misaligned plots.

Solution:

- Single Reference Energy: Ensure that both the total DOS and PDOS are calculated in the same non-SCF run and that the Fermi energy is calculated only once from that same calculation and used as a common reference for all outputs.

- Consistent Post-Processing: When processing results, align all DOS data (total and partial) to the same Fermi energy value. Most codes output energies relative to the Fermi level by default. If you are using a script to plot, force it to use one consistent Fermi level for all data sets.

- Manual Alignment: If the above fails, you can manually shift the energy axes of your PDOS data to align with the total DOS, using the Fermi level as the zero point. This is often a last resort and indicates a potential issue with the calculation setup.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for PDOS Calculation in DFTB+

This protocol outlines the steps for obtaining PDOS using DFTB+ [3].

- Perform a Converged SCF Calculation:

- Objective: Obtain self-consistent charges.

- Method: Use a sufficiently dense k-point grid (e.g., a 4x4x4 Monkhorst-Pack set) and a tight SCC tolerance (e.g.,

SccTolerance = 1e-5). - Input Setup: In the

Analysisblock, define the projected DOS regions usingProjectStates. Specify the atoms (by element or index) and setShellResolved = Yesto get orbital-level contributions.

- Calculate Band Structure and DOS on a Dense k-Path:

- Objective: Get accurate band dispersion and DOS on a high-symmetry path.

- Method: Copy the

charges.binfrom the previous step. In the new input file, setReadInitialCharges = YesandMaxSCCIterations = 1. Change theKPointsAndWeightsto aKlinesblock that defines the path through high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone.

- Post-Process and Plot:

- Objective: Generate plottable DOS and PDOS files.

- Method: Use the

dp_dostool. For the total DOS:dp_dos band.out dos_total.dat. For each PDOS file (e.g.,dos_ti.1.dat), use the weighting option:dp_dos -w dos_ti.1.out dos_ti.s.dat.

Protocol 2: Accessing and Plotting PDOS in VASP via py4vasp

This protocol describes how to extract and visualize pre-calculated PDOS from a VASP calculation [29].

- Prerequisite Calculation: Run a VASP calculation with

LORBITset in theINCARfile to generate the required projection data. - Access the DOS Object: In a Python script or Jupyter notebook, use

py4vaspto access the calculation'sDosobject. - Select and Plot: Use the

to_graph()orplot()method of theDosobject. Specify the desired orbital projections using theselectionargument. The syntax allows for flexible combinations:selection="1(p)"selects p-orbitals of the first atom.selection="d(Mn, Co, Fe)"selects d-orbitals of Mn, Co, and Fe atoms.selection="Ti(d) - O(p)"calculates the difference between the d-orbitals of Ti and the p-orbitals of O.

Quantitative Data from PDOS Analysis

The table below summarizes typical information that can be extracted from a PDOS analysis, using the example of anatase TiO₂ and silicon [3] [32].

Table 1: Key electronic properties derived from PDOS analysis for selected materials.

| Material | Property | Value | Contributing Orbitals (from PDOS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anatase (TiO₂) | Valence Band Edge | Dominated by O p-orbitals | Oxygen p [3] |

| Conduction Band Edge | Dominated by Ti d-orbitals | Titanium d [3] | |

| Silicon (Si) | Indirect Band Gap | ~1.1 eV (theoretical/experimental) | - [33] |

| Conduction Band Minimum | Located at ~85% to X-point (0.425, 0, 0.425) | - [32] | |

| SiO₂ (Quartz) | Indirect Band Gap (HSE06-DDH) | 9.62 eV | - [32] |

| Valence Bands | Dominated by O p shell | Oxygen p [32] | |

| Conduction Bands | Dominated by Si p shell | Silicon p [32] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential software tools and functions for PDOS analysis.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Feature for PDOS |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Planewave DFT code | PDOS via LORBIT; analyzed via py4vasp with flexible atomic/orbital selection syntax [29]. |

| DFTB+ | Density-functional tight-binding code | ProjectStates block for site- and shell-resolved PDOS; uses dp_dos for smearing and output [3]. |

| QuantumATK | Multiscale platform | ProjectedDensityOfStates analyzer with projections on Elements, Shells, or Sites for local analysis [32]. |

| ABINIT | Planewave DFT code | prtdos 3 outputs PDOS; variables natsph and iatsph for projections on specific atoms [30]. |