Polymorphic Stability in Pharmaceuticals: A Comparative Analysis for Robust Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of polymorphic stability and its critical impact on pharmaceutical development.

Polymorphic Stability in Pharmaceuticals: A Comparative Analysis for Robust Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of polymorphic stability and its critical impact on pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles governing polymorph stability, advanced methodologies for identification and quantification, strategic approaches for troubleshooting and risk mitigation, and robust validation through computational and comparative case studies. By integrating recent advances in crystal structure prediction with experimental techniques, this review serves as a strategic guide for ensuring solid-form control, enhancing product quality, and preventing costly development failures due to polymorphic transitions.

Understanding Polymorphic Stability: Fundamentals, Risks, and Energetics

Defining Polymorphism and Desmotropy in Pharmaceutical Solids

In pharmaceutical sciences, the solid-state form of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is a critical quality attribute that directly influences product performance, stability, and manufacturability. Polymorphism and desmotropy represent two distinct but related solid-form phenomena that present both challenges and opportunities in drug development. Polymorphism refers to the ability of a single chemical compound to exist in multiple crystalline forms with different arrangements or conformations of molecules in the crystal lattice [1]. These polymorphic forms share identical chemical composition but differ in their crystal packing, leading to potentially significant differences in physicochemical properties [2].

Desmotropy, a term derived from Greek meaning "change of bonds," describes a special case of tautomerism in which both tautomeric forms have been isolated as solid crystalline materials [3]. Unlike conventional polymorphism, desmotropes involve actual differences in molecular structure through proton transfer and bond rearrangement, typically occurring in compounds with annular tautomerism where proton transfer occurs within ring atoms [3]. The fundamental distinction lies in the molecular scale: polymorphism involves identical molecules in different packing arrangements, while desmotropy involves chemically distinct tautomers in the solid state.

Understanding and controlling these solid forms is essential for ensuring consistent drug product quality, stability, and therapeutic performance. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these phenomena, with experimental approaches for their characterization and control within stability research programs.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Polymorphism: Diversity in Crystal Packing

Polymorphism occurs when the same molecular compound crystallizes in different three-dimensional arrangements. These different arrangements, known as polymorphs, can exhibit dramatically different properties including melting point, solubility, dissolution rate, stability, and bioavailability [1]. The phenomenon is remarkably common in pharmaceuticals, affecting approximately 25% of hormones, 60% of barbiturates, and 70% of sulfonamides [1].

Polymorphs can exist in different thermodynamic relationships:

- Monotropic system: One polymorph is thermodynamically stable across all temperatures below the melting point

- Enantiotropic system: Each polymorph has a specific temperature range where it is the most stable form

A prominent example of polymorphic behavior is Tegoprazan, a potassium-competitive acid blocker, which exists in three solid forms: amorphous, Polymorph A, and Polymorph B [4]. In this system, Polymorph A has been identified as the thermodynamically stable form across all conditions studied, while both the amorphous form and Polymorph B convert to Form A through solvent-mediated phase transformations [4].

Desmotropy: Solid-State Tautomerism

Desmotropy represents a specific type of solid-state phenomenon where the isolated crystalline forms correspond to different tautomers of the same molecular compound. These desmotropes are not simply different crystal packing arrangements of identical molecules, but rather stabilized different molecular structures involving proton migration and bond reorganization [3].

The key characteristic of desmotropy is that both tautomeric forms can be isolated as stable crystalline solids under ambient conditions, whereas in solution or melt states, they typically equilibrate rapidly [3]. This distinguishes desmotropes from the more common situation where only one tautomer crystallizes or where different crystal structures contain the same tautomer (conventional polymorphism).

Pyrazolinone derivatives provide classic examples of desmotropic behavior, where compounds can crystallize as either OH-tautomers (11b form) or NH-tautomers (11c form) with distinct hydrogen bonding patterns and physicochemical properties [3].

Key Distinctions and Relationships

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Polymorphism and Desmotropy

| Feature | Polymorphism | Desmotropy |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Basis | Identical molecules in different crystal packing | Different tautomers with distinct molecular structures |

| Bonding Differences | Intermolecular interactions only | Both intermolecular and intramolecular bonding differences |

| Energy Barrier | Relatively lower energy differences between forms | Higher energy barrier due to covalent bond reorganization |

| Interconversion | Often reversible through recrystallization | Typically irreversible under mild conditions |

| Spectral Signatures | Differences in solid-state NMR chemical shifts primarily due to crystal packing effects | Significant differences in both 13C and 15N NMR chemical shifts due to molecular structure changes [3] |

| Pharmaceutical Impact | Affects solubility, stability, bioavailability | Can additionally affect chemical reactivity and metabolic pathways |

Experimental Characterization and Methodologies

Analytical Techniques for Solid Form Characterization

A comprehensive solid-form analysis requires orthogonal analytical techniques to fully characterize and distinguish between polymorphic and desmotropic forms:

X-ray Powder Diffraction (PXRD): This primary technique provides fingerprint patterns for each crystalline form. Polymorphs typically show distinct diffraction patterns due to different crystal packing, while desmotropes may show more significant differences due to both molecular structure and packing variations.

Thermal Analysis: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) measures thermal transitions including melting points, glass transitions, and solid-solid transformations. Desmotropes often show more significant melting point differences due to distinct molecular structures.

Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR): This powerful technique can detect subtle differences in local chemical environments. 15N CPMAS NMR has been identified as particularly useful for distinguishing desmotropic forms, as chemical shifts are sensitive to tautomeric state [3].

Spectroscopic Methods: IR and Raman spectroscopy detect differences in vibrational frequencies related to molecular conformation and hydrogen bonding. Terahertz spectroscopy (3-100 cm⁻¹) can provide additional information about low-frequency crystal lattice vibrations.

Solubility and Dissolution Studies: These practical measurements determine the relative thermodynamic stability and potential performance differences between forms.

Case Study: Tegoprazan Polymorph Characterization

The comprehensive characterization of Tegoprazan polymorphs provides an excellent example of experimental protocols for solid-form analysis [4]:

Materials: Tegoprazan Polymorph A (commercial API from HK inno.N Corporation), Polymorph B (crystalline bulk from Anhui Haoyuan Pharmaceutical), and amorphous form (from Lee Pharma Limited). All materials were verified for identity and phase purity using PXRD and DSC before experimentation.

Conformational Analysis:

- Constructed conformational energy landscapes using relaxed torsion scans with OPLS4 force field

- Performed relaxed torsion scans in 10° increments for two key dihedral angles of each tautomer

- Calculated Boltzmann-weighted probabilities from relative energies

- Validated computational models using NOE-based NMR spectroscopy

Hydrogen-Bonding Analysis:

- Extracted hydrogen-bonded dimers from crystal structures of Polymorphs A and B

- Performed single-point energy calculations using density functional theory with empirical dispersion corrections (wB97X-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPP)

- Compared relative stabilization energies of different hydrogen-bonding motifs

Phase Transformation Studies:

- Conducted solubility measurements and slurry experiments in multiple solvents (methanol, acetone, water)

- Monitored time-dependent polymorphic conversions using PXRD

- Modeled transformation kinetics using Kolmogorov-Johnson-Mehl-Avrami (KJMA) equation

- Investigated solvent-mediated phase transformation mechanisms

Table 2: Experimental Conditions for Tegoprazan Polymorph Transformation Studies [4]

| Experimental Method | Conditions | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Slurry Experiments | Methanol, acetone, water at ambient temperature | Methanol induced direct Form A formation; acetone showed B→A transition |

| Kinetic Monitoring | Time-dependent PXRD measurements | Amorphous and Form B converted to Form A in solvent-dependent manner |

| Stability Studies | Accelerated conditions (40°C/75% RH) | Both amorphous and Form B converted to Form A within ~8 weeks |

| Computational Analysis | DFT-D calculations with dispersion correction | Hydrogen-bonding network in Form A more favorable than Form B |

Strategic Workflow for Solid Form Identification

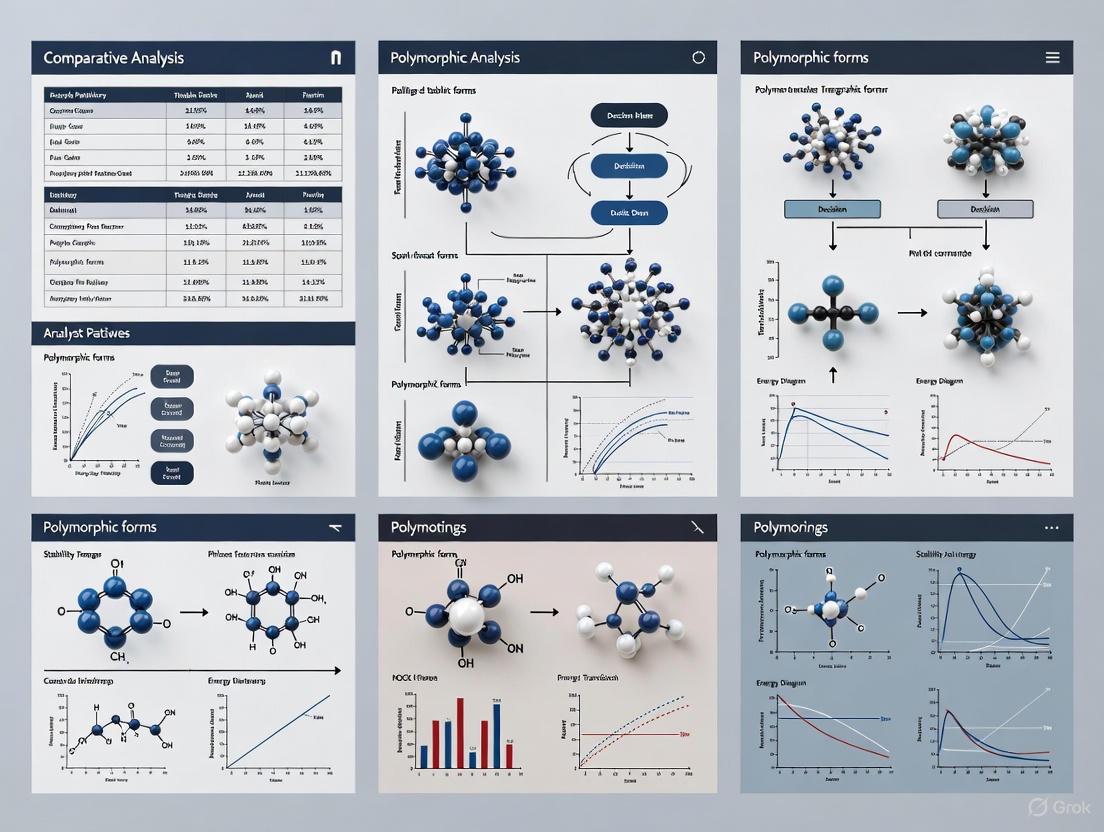

The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic approach for distinguishing and characterizing polymorphic and desmotropic forms:

Stability and Transformation Kinetics

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Factors

Solid-form stability is governed by both thermodynamic and kinetic factors. The thermodynamically most stable form has the lowest free energy under specific conditions of temperature and pressure. However, metastable forms can persist indefinitely due to kinetic barriers that prevent transformation to more stable forms.

For Tegoprazan, comprehensive stability studies revealed that Polymorph A is thermodynamically stable across all conditions studied, while both the amorphous form and Polymorph B convert to Form A through solvent-mediated phase transformations [4]. The transformation kinetics followed the Kolmogorov-Johnson-Mehl-Avrami model, indicating a nucleation and growth mechanism.

Transformation Mechanisms

Mechanical stress during manufacturing processes can induce polymorphic transformations. Milling operations, commonly used for particle size reduction, can cause both polymorphic transformations and amorphization depending on the relationship between milling temperature (Tmill) and the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the compound [2]:

- When Tmill < Tg: Amorphization is generally observed

- When Tmill > Tg: Polymorphic transformation may occur without amorphization

The transformation mechanism often involves a two-step process: first, local amorphization of the starting polymorph occurs under mechanical stress; second, recrystallization to the final form takes place from the amorphous regions [2]. This mechanism has been observed in various pharmaceutical compounds including sorbitol, bezafibrate, and mannitol.

The "Disappearing Polymorph" Phenomenon

The appearance of new polymorphic forms can sometimes make previously known forms difficult or impossible to reproduce—a phenomenon known as "disappearing polymorphs" [4]. This typically occurs when a newly discovered polymorph is more stable than the original form, and trace contamination with seeds of the new form triggers spontaneous transformation throughout the system.

This phenomenon has significant regulatory implications, as demonstrated by well-documented cases involving ritonavir, paroxetine hydrochloride hemihydrate, and loxoprofen sodium hydrate, which led to product recalls due to unexpected polymorphic transitions [4]. More recently, spontaneous crystallization in cyclosporine oral solution resulted in a 2024 recall due to content uniformity concerns [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Solid-State Pharmaceutical Research

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Identity confirmation and method validation | Certified polymorphic forms with known purity (>99%) [4] |

| Solvent Systems | Polymorph screening and crystallization studies | Protic (methanol, water) and aprotic (acetone) solvents for investigating solvent-mediated transformations [4] |

| Computational Software | Conformational analysis and crystal structure prediction | Schrödinger MacroModel (OPLS4 force field), Mercury, Olex2, VESTA, Avogadro [4] |

| Characterization Instruments | Solid-form identification and quantification | PXRD, DSC, ssNMR, Raman/IR spectroscopy, hot-stage microscopy |

| Milling Equipment | Particle size reduction and mechanochemical studies | Cryomill for low-temperature processing, planetary ball mill for room-temperature studies [2] |

| Stability Chambers | Accelerated stability testing | Controlled temperature (40°C) and humidity (75% RH) conditions [4] |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Development

The strategic selection and control of solid forms has profound implications throughout the drug development lifecycle. From a regulatory perspective, comprehensive polymorph screening is expected, and the United States Food and Drug Administration emphasizes the importance of detecting polymorphic forms and implementing control strategies across product development stages [1].

Properties affected by solid-form selection include:

- Bioavailability: Solubility and dissolution rate differences can significantly impact absorption

- Stability: Chemical and physical stability varies between forms, affecting shelf life

- Manufacturability: Flow, compaction, and blending properties differ between solid forms

- Intellectual Property: Novel polymorphic forms can provide patent protection and market exclusivity

The case of Tegoprazan demonstrates how understanding conformational preferences, tautomerism, and solvent-mediated hydrogen bonding enables rational polymorph control and mitigates the risk of disappearing polymorphs in tautomeric drugs [4]. This knowledge supports robust manufacturing processes and consistent product quality throughout the product lifecycle.

In pharmaceutical science, polymorphism—the ability of a solid compound to exist in multiple crystal structures—is a critical factor determining drug efficacy, safety, and manufacturability. These distinct solid forms, known as polymorphs, exhibit different physical and chemical properties despite identical chemical composition, including variations in solubility, dissolution rate, chemical stability, and bioavailability [5]. The infamous case of Ritonavir (Norvir) exemplifies the profound industrial impact of polymorphic instability, where the unexpected appearance of a more stable, less soluble polymorph years after market launch forced a product recall, jeopardizing patient treatment and resulting in losses exceeding US$250 million [5]. A comprehensive understanding of the thermodynamic principles governing stable and metastable polymorphs is therefore fundamental to robust drug development.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of stable and metastable polymorphs, focusing on their thermodynamic characteristics, experimental methods for identification and monitoring, and transformation kinetics. We present structured experimental data and protocols to support researchers in making informed decisions during solid form selection and control.

Thermodynamic Fundamentals and Stability Relationships

The relative stability of polymorphs is governed by their Gibbs free energy (G), defined by the equation ∆G = ∆H - T∆S, where H is enthalpy, T is temperature, and S is entropy [6]. The polymorph with the lowest Gibbs free energy under a given set of temperature and pressure conditions is the thermodynamically stable form. All other forms are metastable and possess an inherent driving force to transform into the stable form, though kinetic barriers may prevent or delay this conversion [7].

The relationship between polymorphs can be classified into two primary systems:

- Monotropic System: One polymorph is thermodynamically stable across the entire temperature range, while other forms are metastable. The metastable forms can irreversibly transform to the stable form.

- Enantiotropic System: The relative stability of polymorphs reverses at a specific transition temperature. One form is stable below this temperature, and another becomes stable above it [6] [7].

External conditions like temperature and pressure act as "thermodynamic levers." Higher temperatures can increase the influence of the entropy (T∆S) term, potentially favoring a less dense polymorph. Conversely, high pressure universally favors denser, more compact polymorphs [6]. These relationships are foundational for predicting and controlling polymorphic behavior.

Energetic Landscape and Transformation Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the thermodynamic and kinetic relationships between stable and metastable polymorphs, integrating key transformation pathways.

- Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control: Crystallization is a race between kinetics and thermodynamics. Under high supersaturation, the system is driven far from equilibrium, and the polymorph with the lowest nucleation barrier (often a metastable form) crystallizes fastest. This is kinetic control. Under low supersaturation near equilibrium, molecules have time to find the most stable arrangement, leading to the thermodynamically stable form [6].

- Transformation Pathways: As shown in Fig. 1, metastable forms can transform into the stable polymorph via two primary mechanisms: Solution-Mediated Phase Transformation (SMPT) and solid-state transformation. SMPT is more common and involves three steps: dissolution of the metastable polymorph, nucleation of the stable polymorph, and growth of the stable polymorph crystals [8].

Comparative Analysis: Stable vs. Metastable Polymorphs

The following table summarizes the defining characteristics of stable and metastable polymorphs, providing a clear framework for their comparison.

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of Stable and Metastable Polymorphs

| Feature | Stable Polymorph | Metastable Polymorph |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic State | Global minimum Gibbs free energy [7] | Local minimum Gibbs free energy [7] |

| Solubility & Dissolution | Lower solubility and slower dissolution rate [5] | Higher solubility and faster dissolution rate [8] |

| Melting Point | Typically higher melting point | Typically lower melting point |

| Physical Stability | Physically stable indefinitely under storage conditions | Can irreversibly transform to the stable form over time [5] |

| Formation Likelihood | Favored by slow crystallization and low supersaturation [6] | Favored by rapid crystallization and high supersaturation [6] |

| Industrial Utility | Preferred for marketed drugs due to long-term stability [4] [5] | Potential for enhanced bioavailability but carries transformation risk [8] |

Quantitative Stability Data from API Case Studies

Experimental data from specific Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) further illustrates these differences. The table below compiles quantitative findings from polymorphic studies.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Polymorphic Case Studies

| API / Material | Observation / Finding | Experimental Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tegoprazan (TPZ) | Polymorph A was thermodynamically stable; amorphous and Polymorph B converted to A. | Slurry experiments, PXRD, DSC, Solubility measurements [4] | [4] |

| l-Carnitine Orotate (CO) | Form-II is the stable polymorph; Form-I (metastable) converts to Form-II via SMPT. | SMPT kinetics, PXRD, DSC [8] | [8] |

| Erbium Oxide (Er₂O₃) | Cubic C-type (stable at ambient) transitions to monoclinic B-type under high-pressure milling. | High-energy ball milling, PXRD, Williamson-Hall analysis [9] | [9] |

| Ritonavir | Form II (previously unknown) precipitated, causing a product recall. Form III discovered later. | Melt crystallization, XRPD [5] | [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

A robust experimental workflow is essential for identifying the thermodynamically stable polymorph and understanding transformation kinetics. The following diagram outlines a standardized protocol for polymorph stability screening.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

1. Slurry Experiments for Thermodynamic Stability:

- Objective: To determine the relative thermodynamic stability of polymorphs in a specific solvent by allowing the system to reach equilibrium.

- Protocol: A mixture of two or more polymorphic forms is suspended (slurried) in a solvent and stirred for a predetermined period, typically at constant temperature. Samples are taken at regular intervals and analyzed by Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) to monitor phase composition. The form that persists at the end of the experiment is the thermodynamically stable form in that solvent under the given conditions [4]. This "slurry bridging" technique is a cornerstone of stability ranking.

2. Solution-Mediated Polymorphic Transformation (SMPT) Kinetics:

- Objective: To quantitatively study the transformation rate of a metastable polymorph to a stable polymorph in solution.

- Protocol: A suspension of the pure metastable form is prepared in a solvent. The slurry is stirred at a fixed temperature and rotational speed. The transformation is monitored over time by sampling and analyzing the solid phase via PXRD or DSC. The data is often modeled using the Kolmogorov–Johnson–Mehl–Avrami (KJMA) equation to derive empirical rate parameters, which are influenced by temperature and supersaturation [4] [8].

3. Stress Testing under Accelerated Conditions:

- Objective: To assess the physical stability of polymorphs under conditions that might be encountered during storage or processing.

- Protocol: Solid samples are stored under elevated temperature and humidity (e.g., 40°C/75% relative humidity) for several weeks. The samples are periodically checked using PXRD for any signs of polymorphic transformation, deliquescence, or amorphization [4]. This helps define suitable storage conditions for APIs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful polymorph stability research relies on specific instrumentation and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Instrumentation

| Item | Function / Application in Polymorph Research |

|---|---|

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Primary technique for identifying and quantifying polymorphic phases based on unique diffraction patterns [4] [9]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Used to study thermal events (melting, crystallization, solid-solid transitions) and determine melting points and enthalpies [4] [8]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Measures weight changes associated with desolvation, dehydration, or decomposition, helping distinguish solvates from anhydrous polymorphs [8]. |

| Solid-State NMR (ssNMR) | Provides molecular-level information on conformation, hydrogen bonding, and dynamics, complementing diffraction studies [4] [8]. |

| Solvent Systems (Protic & Aprotic) | Used for crystallization and slurry experiments. Solvent-solute interactions can stabilize specific conformations and guide polymorphic outcomes (e.g., methanol vs. acetone for Tegoprazan) [4] [6]. |

| Environmental Chambers | Enable stress testing of solid forms under controlled temperature and humidity to assess physical stability [4]. |

Industrial Implications and Strategic Control

The selection of a drug's solid form is a critical decision with long-term consequences. While metastable polymorphs can offer advantages like higher solubility and potentially better bioavailability, they carry the risk of transformation, which can compromise product performance, as witnessed with Ritonavir [5]. Therefore, the thermodynamically stable polymorph is typically selected for marketed drug products to ensure consistency and shelf-life stability [4] [5].

A proactive approach is essential for risk mitigation. This includes:

- Comprehensive Polymorph Screening: Conducting extensive screens early in development to map the solid-form landscape and identify as many forms as possible [5].

- Robust Analytical Control: Implementing sensitive techniques like PXRD and DSC for routine monitoring of the API and final drug product to detect unwanted form changes.

- Process Control: Carefully designing crystallization and manufacturing processes (controlling supersaturation, cooling rates, solvent composition, and agitation) to consistently produce the desired polymorph [6].

- Intellectual Property Strategy: Patenting specific polymorphs can provide additional layers of IP protection beyond the base compound patent, extending market exclusivity [10].

Understanding the thermodynamic principles that distinguish stable and metastable polymorphs is fundamental to successful pharmaceutical development. The stable polymorph, with its lower energy state, offers predictability and long-term stability, making it the preferred choice for drug products. Metastable forms, while attractive for their enhanced performance properties, require careful handling due to their innate driving force to transform. Through the systematic application of the experimental protocols and tools outlined in this guide—including thermodynamic slurry studies, kinetic SMPT analysis, and accelerated stress testing—researchers can make informed decisions, mitigate the risks of disappearing polymorphs, and ensure the development of safe, effective, and robust pharmaceutical products.

The Disappearing Polymorph Phenomenon and Clinical Failures

In the pharmaceutical industry, the solid form of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is a critical quality attribute that directly impacts product safety, efficacy, and manufacturability. Polymorphism—the ability of a substance to exist in multiple crystal structures with the same chemical composition—poses both opportunities and significant challenges for drug development [11]. Among these challenges, the "disappearing polymorph" phenomenon represents a particularly problematic occurrence in which a previously obtained crystalline form becomes irreproducible, typically superseded by a more thermodynamically stable polymorph [12] [13]. This phenomenon has been responsible for several high-profile clinical failures and product recalls, costing companies hundreds of millions of dollars and potentially jeopardizing patient access to essential medications [13] [14].

The disappearance of a polymorphic form typically occurs when a metastable form, initially discovered and developed, is replaced by a more stable form that emerges later in the development lifecycle or even after product commercialization [12]. Once the more stable form appears, microscopic seed crystals can contaminate manufacturing facilities and equipment, making it extremely difficult to reproduce the original polymorphic form [12] [13]. This review examines the scientific principles underlying disappearing polymorphs, analyzes documented case studies of clinical failures, compares experimental methodologies for studying polymorphic stability, and discusses risk mitigation strategies for modern drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Principles

The disappearing polymorph phenomenon is fundamentally governed by the interplay between thermodynamic stability and kinetic control in crystallization processes. According to the Gibbs phase rule, under most conditions of fixed temperature, pressure, and chemical potential, only one crystalline phase is thermodynamically stable, while other forms are metastable [13]. The metastable forms possess higher Gibbs free energy than the stable form, creating a driving force for transformation, though kinetic barriers may prevent or delay this conversion [12].

Crystallization typically follows Ostwald's Rule of Stages, which suggests that a system often initially forms a metastable polymorph that is kinetically accessible, which may later transform to a more stable form [12]. The disappearance of the original polymorph occurs when this more stable form emerges and its microscopic seed crystals become widespread, effectively seeding subsequent crystallization attempts and preventing formation of the metastable form [12] [13].

The Seeding Hypothesis

The central mechanism explaining the disappearing polymorph phenomenon involves seed crystals of the more stable form. As noted in disappearing polymorph cases, a single microscopic seed crystal—potentially as small as a few million molecules (approximately 10⁻¹⁵ g)—can be sufficient to initiate a chain reaction transforming a much larger mass of material [13]. These seeds can become airborne and contaminate entire laboratories or manufacturing facilities, explaining why the disappearance of polymorphs can spread geographically over time [12] [13].

The powerful effect of microscopic seeding is supported by observations that initial crystallizations of a newly synthesized compound are often difficult, while subsequent crystallizations proceed more readily once crystal nuclei are present in the laboratory environment [12]. For perspective, a crystal speck weighing 10⁻⁶ g (at the visual detection limit) contains approximately 10¹⁶ molecules, and could contain up to 10¹⁰ potential seed crystals [12].

Case Studies of Clinical Failures

Several documented cases illustrate how disappearing polymorphs have led to significant clinical and commercial consequences in the pharmaceutical industry.

Ritonavir (Norvir)

The ritonavir case represents one of the most notorious examples of disappearing polymorphs in pharmaceuticals. Ritonavir, an HIV protease inhibitor, was originally developed and marketed in 1996 as a semisolid gel capsule formulation based on the only known crystal form at the time (Form I) [14]. In 1998, approximately two years after product launch, a new polymorph (Form II) unexpectedly appeared with significantly lower solubility, making the formulation medically ineffective [13] [14].

The emergence of Form II had severe consequences:

- Product recall: The original gel capsule formulation had to be withdrawn from the market [14]

- Manufacturing disruption: Form II became impossible to avoid in manufacturing facilities where it had been introduced, as microscopic seed crystals contaminated entire plants [13]

- Patient impact: Tens of thousands of AIDS patients temporarily lost access to this medication unless they switched to a liquid suspension [13]

- Financial loss: Abbott Laboratories, the manufacturer, lost an estimated $250-900 million due to the incident [13] [14]

- Reformulation requirement: The drug had to be reformulated as a new capsule formulation, which was not re-approved until 1999 [14]

Interestingly, ritonavir continued to demonstrate polymorphic complexity, with additional forms discovered in 2005 (Form IV) and 2022 (Form III), highlighting that new polymorphs can emerge even decades after initial development [14].

Paroxetine Hydrochloride

The case of paroxetine hydrochloride illustrates how disappearing polymorphs can create complex legal and intellectual property challenges in addition to technical problems. Originally developed in the 1970s, paroxetine anhydrate was found to be hygroscopic and difficult to handle [13]. In 1984, a new crystal form—paroxetine hemihydrate—appeared simultaneously at multiple manufacturing sites [13].

The hemihydrate form proved to be more stable due to a higher number of hydrogen bonds, and in the presence of water or humidity, contact with hemihydrate crystals converted the anhydrate form to hemihydrate [13]. This transformation became the subject of extensive patent litigation between GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and generic manufacturer Apotex, as the generic company attempted to produce the original anhydrate form but found it consistently transformed to the still-patented hemihydrate form [13]. The case demonstrated how disappearing polymorph phenomena could be used to extend patent protection and block generic competition.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Polymorph Failures

| Drug Product | Original Form | Emerging Form | Consequence | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritonavir (Norvir) | Form I (semisolid gel capsules) | Form II (lower solubility) | Market withdrawal; $250-900M loss; temporary treatment disruption | Emerged 2 years post-launch |

| Paroxetine HCl | Anhydrate | Hemihydrate | Patent litigation; manufacturing challenges; generic competition barriers | Emerged 8 years after initial development |

| Tegoprazan | Polymorph B (metastable) | Polymorph A (stable) | Conversion risks during storage; batch consistency issues | Controlled through solvent-mediated phase transformation |

Emerging Concerns: Tegoprazan

Recent research on Tegoprazan (TPZ), a potassium-competitive acid blocker, demonstrates that disappearing polymorph risks remain a contemporary challenge in drug development. TPZ exists in three solid forms: amorphous, Polymorph A (thermodynamically stable), and Polymorph B (metastable) [4]. The commercial formulation uses Polymorph A due to its superior stability, but the transient formation of metastable Polymorph B during processing or storage presents risks for product consistency and quality [4].

Studies have shown that both amorphous TPZ and Polymorph B convert to Polymorph A through solvent-mediated phase transformations in a solvent-dependent manner [4]. These observations highlight the importance of understanding and controlling polymorphic conversions to ensure robust manufacturing processes and consistent product quality throughout the drug product lifecycle.

Experimental Approaches for Polymorph Stability Assessment

Methodologies for Stability Ranking

Comprehensive polymorph screening and stability assessment require multiple complementary analytical techniques to fully characterize solid forms and their interconversions.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Polymorph Characterization

| Method | Application | Key Measured Parameters | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Solid form identification and quantification | Crystal structure, phase purity, crystallinity | Limited sensitivity to amorphous content |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Thermal behavior analysis | Melting point, enthalpy of fusion, polymorphic transitions | Potential for solid-state transitions during heating |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Solvate/hydrate identification | Weight loss upon desolvation/dehydration | Cannot detect isomorphic desolvates |

| Solubility Measurements | Relative stability assessment | Solubility differences, transition concentrations | Time-dependent due to potential conversion |

| Slurry Conversion Experiments | Stability ranking under pharmaceutically relevant conditions | Thermodynamic stability order | Solvent-dependent results |

| Solution Calorimetry | Energetic measurements | Heat of solution, thermodynamic relationships | Requires careful experimental design |

The Noyes-Whitney titration method has been employed to rank polymorph stability through solubility measurements, enabling determination of Gibbs energy changes for polymorphic conversions [15]. For example, a ΔΔG of -3.98 kJ mol⁻¹ for the conversion of Form I to Form III of a development drug indicated these forms were not bioequivalent, informing formulation selection [15].

Stability and Bioequivalence Considerations

The thermodynamic relationship between polymorphs directly impacts their potential bioequivalence. Generally, small Gibbs energy differences (e.g., -1.05 kJ mol⁻¹ for mefenamic acid Form II to Form I) suggest likely bioequivalence, while larger differences (e.g., -3.24 kJ mol⁻¹ for chloramphenicol palmitate Form B to Form A) often indicate potential bioinequivalence [15]. These relationships highlight why understanding polymorph stability is crucial not only for physical stability but also for ensuring consistent clinical performance.

Risk Mitigation Strategies

Comprehensive Polymorph Screening

Modern approaches to polymorph risk mitigation involve extensive solid-form screening early in development. A recent survey of 476 new chemical entities (NCEs) revealed that approximately 90% of solid-form screens identified multiple polymorphs, with about 50% of development forms showing moderate to high polymorphism risks [16]. This high prevalence underscores the importance of thorough solid-form assessment during development.

Current strategies include:

- High-throughput crystallization: Automated approaches to explore diverse crystallization conditions [11]

- Computational prediction: Crystal structure prediction (CSP) methods to identify potentially stable forms [4]

- Melt crystallization: Inclusion of melt techniques, particularly for APIs stable at elevated temperatures [14]

- Stress testing: Exposure of solid forms to varied temperature, humidity, and mechanical stress conditions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Polymorph Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Polymorph Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvents | Create diverse crystallization environments; mediate phase transformations | Methanol, acetone, ethyl acetate for solvent-mediated transformations [4] |

| Polymorphic Seeds | Intentional seeding to control crystallization outcome | Purified crystals of specific polymorphs to direct crystallization [12] |

| Computational Tools | Predict stable crystal structures and conformational landscapes | DFT-D calculations, crystal structure prediction software [4] |

| Reference Standards | Authenticated materials for analytical method development | Certified polymorphic forms for PXRD, DSC, and spectroscopy [17] |

Integrated Workflow for Polymorph Risk Management

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive approach to managing disappearing polymorph risks throughout the drug development lifecycle:

Polymorph Risk Management Workflow

This integrated approach begins with comprehensive screening to identify potential polymorphs early, followed by rigorous stability assessment to understand transformation risks. Based on this understanding, appropriate manufacturing controls are implemented, complemented by ongoing monitoring to detect late-appearing forms.

The disappearing polymorph phenomenon remains a significant challenge in pharmaceutical development, with potential consequences ranging from manufacturing difficulties to complete product failures. Cases such as ritonavir and paroxetine illustrate the severe clinical and commercial impacts when polymorphic transformations occur unexpectedly. The fundamental thermodynamic principles underlying these transformations are well-established, but practical challenges in prediction and control persist.

Modern risk mitigation requires a comprehensive, integrated approach combining extensive experimental screening, computational prediction, robust process controls, and continual monitoring. As drug molecules become increasingly complex, with greater conformational flexibility and structural diversity, the challenges of polymorph control are likely to intensify [16]. By understanding and applying the lessons from past failures, implementing rigorous polymorph screening strategies, and maintaining vigilance throughout the product lifecycle, the pharmaceutical industry can better manage the risks associated with disappearing polymorphs and ensure consistent product quality and clinical performance.

Impact of Tautomerism and Conformational Flexibility on Stability

Tautomerism and conformational flexibility are fundamental molecular properties that profoundly influence the stability of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Tautomerism involves the dynamic equilibrium between constitutional isomers that differ in the position of a proton and accompanying double bonds, while conformational flexibility refers to a molecule's ability to adopt different spatial orientations through rotation around single bonds [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these phenomena is critical as they directly impact the selection of solid forms, influence polymorphic stability, and dictate the physicochemical properties that determine a drug's shelf life, bioavailability, and overall performance [4] [19].

The interplay between these molecular characteristics presents both challenges and opportunities in pharmaceutical development. Tautomeric preferences can shift between solution and solid states, leading to unexpected crystallization outcomes, while conformational diversity can result in multiple crystal packing arrangements with distinct stability profiles [4] [20]. This comparative analysis examines how these factors govern stability across different pharmaceutical systems, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant to polymorphic form selection and control strategies in preformulation and formulation development.

Fundamental Concepts and Challenges

Tautomerism in Pharmaceutical Systems

Tautomerism represents a significant challenge in computer-aided drug design due to the profound impact on molecular properties and biological activity. The process of tautomerization typically involves proton migration accompanied by rearrangement of double bonds within the molecule [18]. Among various tautomerism types, keto-enol tautomerism is particularly prevalent in pharmaceutical compounds, where a carbonyl group (keto form) interconverts with a hydroxyl group attached to a carbon-carbon double bond (enol form) [18].

The pharmaceutical relevance of tautomerism is substantial, with estimates suggesting that more than a quarter of marketed drugs can exhibit tautomerism, while analysis of chemical databases indicates that 10-30% of potential drug molecules have possible tautomers [18]. This prevalence is problematic because tautomeric changes can alter hydrogen bonding capacity, transforming a hydrogen bond donor into an acceptor or vice versa, which fundamentally affects molecular recognition and structure-activity relationships [18]. Additionally, tautomeric ratios in solution are highly sensitive to environmental conditions such as pH and solvent polarity, creating challenges for consistent crystallization behavior and polymorph control [4] [20].

Conformational Flexibility and Polymorphic Landscapes

Conformational flexibility enables molecules to adopt various low-energy orientations through rotation around single bonds, creating a complex energy landscape with multiple local minima [4]. During crystallization, these conformational preferences directly influence molecular packing and consequently determine the resulting solid form and its properties.

The relationship between conformational flexibility and polymorphism is particularly evident in flexible drug-like molecules with multiple torsional degrees of freedom. For instance, in Tegoprazan (TPZ), a potassium-competitive acid blocker, conformational bias in solution was found to direct polymorph selection, with specific solution conformers corresponding to the packing motif of the stable polymorph [4]. This conformational guidance during crystallization means that understanding solution-phase behavior becomes essential for predicting solid-form stability [4].

Table 1: Key Challenges in Managing Tautomerism and Conformational Flexibility

| Challenge | Impact on Stability | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Shifting Tautomeric Equilibria | Alters hydrogen bonding patterns and molecular shape, affecting crystal packing | Solution-state studies (NMR) combined with computational pKa prediction [20] |

| Multiple Low-Energy Conformers | Increases polymorphic risk with forms of similar stability | Conformational energy landscape mapping via torsion scans [4] |

| Solvent-Dependent Preferences | Different forms crystallize from different solvents, leading to inconsistent results | Slurry experiments in multiple solvent systems [4] |

| Prototropic Tautomerism in Polybasic Molecules | Highly charged states complicate crystallization pathways | pKa prediction accounting for pH-dependent speciation [20] |

Comparative Analysis of Experimental Data

Case Study: Tegoprazan Polymorphs

Research on Tegoprazan (TPZ) provides compelling experimental evidence for the role of conformational flexibility in polymorphic stability. TPZ exists in three solid forms: amorphous, Polymorph A, and Polymorph B, with comprehensive investigation revealing distinct stability profiles [4].

Table 2: Comparative Stability Data for Tegoprazan Polymorphs [4]

| Solid Form | Thermodynamic Stability | Conversion Behavior | Key Stability Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous TPZ | Metastable | Converts to Polymorph A in solvent-dependent manner | No glass transition observed; transforms via solvent-mediated mechanism |

| Polymorph B | Metastable | Converts to Polymorph A (direct or through intermediate) | Appears only under specific crystallization conditions; disappears upon prolonged exposure |

| Polymorph A | Thermodynamically stable | No conversion to other forms observed | Stable across all analyses (PXRD, DSC, solubility); used in commercial formulations |

Experimental data from TPZ studies demonstrated that both amorphous TPZ and Polymorph B converted to the stable Polymorph A through solvent-mediated phase transformations (SMPTs) [4]. The kinetics of these transformations followed the Kolmogorov–Johnson–Mehl–Avrami (KJMA) model, with conversion rates highly dependent on solvent environment. Methanol induced direct formation of Polymorph A, while acetone showed a transitional B→A conversion [4]. These solvent-dependent pathways highlight how conformational populations in solution direct polymorphic outcomes, with protic solvents favoring the thermodynamically stable form through specific hydrogen-bonding interactions [4].

Energetic and Computational Analyses

Computational studies provided quantitative support for the observed stability relationships in TPZ. DFT with dispersion corrections (DFT-D) calculations on hydrogen-bonded dimers extracted from crystal structures revealed that the packing motif in Polymorph A provided approximately 2-3 kcal/mol greater stabilization per dimer compared to Polymorph B [4]. This energy difference, while seemingly small, was sufficient to drive complete conversion to the stable form over time.

For the 3-Hydroxy-propeneselenal system, computational analysis identified twenty different conformers, with the most stable being planar structures stabilized by Se...H-O and Se-H...O intramolecular hydrogen bonds assisted by π-electron resonance [21]. The Atoms in Molecules (AIM) theory analysis confirmed the nature and strength of these hydrogen bonds, demonstrating how specific intramolecular interactions pre-organize molecules for optimal crystal packing [21].

Table 3: Computational Methods for Stability Prediction

| Computational Method | Application | Accuracy and Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| DFT with Dispersion Corrections (DFT-D) | Hydrogen-bonded dimer energy calculations | High accuracy for interaction energies; validates observed stability [4] |

| Conformational Energy Landscapes | Mapping low-energy conformers via torsion scans | Identifies solution-state preferences guiding crystallization [4] |

| Atoms in Molecules (AIM) Theory | Hydrogen bond characterization and strength assessment | Provides quantitative analysis of stabilizing interactions [21] |

| pKa Prediction with Linear Empirical Correction | Protonation state and tautomer populations at different pH | RMSD ~1.2 log units for tetra-aza macrocycles [20] |

| Quantum Simulation (VQE) | Tautomeric state prediction for drug-like molecules | Agreement with CCSD benchmarks; emerging method [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Conformational Analysis and Energy Landscape Mapping

Understanding conformational preferences requires comprehensive energy landscape mapping. The following protocol has been successfully applied to pharmaceutical systems like Tegoprazan [4]:

Relaxed Torsion Scans: Perform systematic rotation around key dihedral angles (typically in 10° increments) using force fields such as OPLS4 as implemented in Schrödinger MacroModel.

Quantum Mechanical Refinement: Select low-energy conformers identified through torsion scans for further optimization using density functional theory (DFT) methods with continuum solvent models.

Boltzmann Weighting: Calculate relative populations of conformers based on their free energies using the Boltzmann distribution to identify dominant solution-state species.

NMR Validation: Compare computational predictions with experimental nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE)-based NMR data to confirm solution-state conformations.

This integrated approach successfully identified two dominant solution conformers of Tegoprazan that corresponded to the packing motif found in the stable Polymorph A, demonstrating the critical relationship between solution conformation and solid-form stability [4].

Polymorph Stability and Transformation Studies

Robust experimental assessment of polymorph stability requires multiple complementary techniques:

Slurry Conversion Experiments [4]:

- Prepare saturated solutions of the API in various solvents (e.g., methanol, acetone, water)

- Add excess solid (approximately 50-100 mg/mL) of the metastable form

- Agitate continuously using magnetic stirring or orbital shaking

- Monitor phase transformation through periodic sampling and PXRD analysis

- Model transformation kinetics using the Kolmogorov–Johnson–Mehl–Avrami (KJMA) equation

Accelerated Stability Testing [22]:

- Store solid forms under International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) accelerated conditions (40°C ± 2°C/75% RH ± 5% RH)

- Sample at predetermined intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 3, 6 months)

- Analyze for chemical purity (HPLC), solid form (PXRD), and physical properties (DSC, TGA)

- Compare with long-term storage conditions (25°C ± 2°C/60% RH ± 5% RH) to establish shelf-life predictions

Computational pKa Prediction for Tautomeric Systems

Predicting pKa values for flexible, polybasic molecules requires specialized protocols to account for tautomerism [20]:

Conformational Sampling: Use tools like CREST/xTB to generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers for each protonation state.

Quantum Mechanical Optimization: Refine geometries and calculate free energies using density functional theory (e.g., ωB97X-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP) with implicit solvation models (e.g., SMD, COSMO).

Microscopic pKa Calculation: Determine free energy differences between protonation states using thermodynamic cycles.

Linear Empirical Correction (LEC): Apply system-specific corrections to improve agreement with experimental data, reducing root-mean-square deviation from ~3.88 to ~1.21 log units for tetra-aza macrocycles [20].

This protocol successfully predicted pKa values and dominant tautomers for previously unsynthesized tetra-aza macrocycles, providing valuable leads for future experimental work [20].

Visualization of Research Workflows

Integrated Stability Assessment Protocol

Tautomerism Impact on Crystal Packing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Stability Research

| Research Tool | Function and Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Solvent Systems | Exploring conformational and tautomeric preferences in different environments | Methanol, acetone, water for slurry conversion studies [4] |

| Polymorph Screening Kits | Systematic exploration of crystalline forms | Commercial screens with varied solvents, anti-solvents, and crystallization methods |

| Stability Chambers | Controlled temperature and humidity for ICH stability testing | Chambers for 25°C/60% RH, 30°C/65% RH, 40°C/75% RH [22] |

| Computational Software | Conformational analysis, energy calculations, and pKa prediction | Schrödinger MacroModel, Gaussian, CREST/xTB [4] [20] |

| Characterization Standards | Reference materials for instrument calibration | Silicon standard for PXRD, indium for DSC calibration |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Development

The relationship between tautomerism, conformational flexibility, and stability carries significant implications for drug development strategies. Understanding these molecular features enables more predictive polymorph control and helps mitigate the risk of disappearing polymorphs - phenomena where previously accessible crystalline forms become irreproducible due to spontaneous transformation to more stable forms [4] [10].

For patent protection, understanding polymorphic stability is crucial. Patent applications should claim polymorphic forms in multiple ways - by XRPD peak listings of varying lengths, combined with other physical properties like melting point or IR spectra - to ensure robust protection [10]. However, applicants should exercise caution when claiming polymorphs by extensive peak lists, as enforcement requires establishing that alleged infringing material contains all claimed peaks [10].

Regulatory considerations further emphasize the importance of stability understanding. Polymorphic changes during storage or manufacturing can lead to product inconsistencies, manufacturing stoppages, and noncompliance with regulatory standards [19]. As such, regulatory agencies require comprehensive characterization and control of solid-state forms to ensure consistent bioavailability and product quality throughout the shelf life [19].

Tautomerism and conformational flexibility represent critical molecular features that directly dictate the stability and performance of pharmaceutical compounds. The comparative analysis presented demonstrates that:

Solution-state conformational preferences directly guide polymorph selection during crystallization, with specific low-energy conformers corresponding to stable packing motifs [4].

Tautomeric equilibria shift with solvent environment and pH, creating multiple possible crystallization pathways that can lead to different solid forms with distinct stability profiles [20] [18].

Computational methods have advanced significantly, providing reasonable predictions of pKa values, tautomer populations, and relative stability, though challenges remain for highly flexible, polybasic molecules [20] [18].

Integrated experimental-computational approaches offer the most robust strategy for polymorph stability assessment, combining conformational analysis, computational chemistry, and targeted experimental validation.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the necessity of early and comprehensive assessment of tautomerism and conformational flexibility during preformulation stages. Such proactive characterization enables more predictive solid form selection, reduces the risk of late-stage polymorphic surprises, and ultimately leads to more robust and stable pharmaceutical products.

The phenomenon of polymorphism, where a solid substance can exist in more than one crystal structure, is a critical consideration in the development of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). These different polymorphic forms can exhibit significantly different physicochemical properties, including solubility, dissolution rate, chemical stability, and ultimately, bioavailability [11]. The control and understanding of polymorphic forms are therefore essential for ensuring drug product quality, efficacy, and regulatory compliance.

Solvent-Mediated Polymorphic Transformations (SMPTs) represent a specific and crucial mechanism of solid-state phase transition. In an SMPT, the transformation from a metastable polymorph to a more stable one is facilitated by the surrounding solvent or liquid medium. This process generally occurs through three fundamental steps: (1) dissolution of the metastable form, (2) nucleation of the stable form, and (3) growth of the stable form crystals [23]. The kinetics of this transformation are of paramount importance, as the transient existence of a more soluble, metastable form can be exploited to enhance bioavailability, but its unexpected appearance or persistence can lead to significant product failures.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of SMPT kinetics and mechanisms, drawing on experimental data from model APIs to equip researchers with the knowledge to control these critical transformations in pharmaceutical development.

Comparative Kinetics of SMPTs in Conventional vs. Nonconventional Solvents

The kinetics of SMPTs are highly dependent on the properties of the solvent medium. A key differentiator is the classification of solvents as "conventional" (e.g., ethanol, acetone) or "nonconventional" (e.g., polymer melts). Conventional solvents, characterized by low molecular weights, boiling points, and viscosities, typically allow for rapid transformations. In contrast, nonconventional solvents like polymer melts can significantly hinder molecular mobility and thus dramatically alter transformation kinetics [23].

Table 1: Comparative SMPT Kinetics and Key Parameters for Acetaminophen and Tegoprazan

| API / System | Transformation | Solvent / Medium | Key Kinetic Parameter (Induction Time / Rate Constant) | Diffusion Coefficient, D (m²/s) | Governing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen (ACM) [23] | Form II → Form I | Ethanol (Conventional) | Induction time: ~30 s at 25°C | ( D_{ethanol} = 4.84 \times 10^{-9} ) | High molecular mobility in low-viscosity solvent |

| Form II → Form I | PEG 4000 Melt | Induction time: Tunable and prolonged | ( D_{PEG4000} = 5.32 \times 10^{-11} ) | Diffusivity in polymer melt | |

| Form II → Form I | PEG 35000 Melt | Induction time: Tunable and prolonged | ( D_{PEG35000} = 8.36 \times 10^{-14} ) | Melt viscosity / molecular weight | |

| Tegoprazan (TPZ) [4] | Amorphous → Polymorph A | Methanol | Direct formation of A | Not Specified | Protic solvent, conformational bias |

| Polymorph B → Polymorph A | Acetone | Observable B → A transition | Not Specified | Aprotic solvent, hydrogen bonding | |

| Polymorph B → Polymorph A | Accelerated Stability (40°C/75% RH) | ~8 weeks (solid-state) | Not Specified | Temperature and humidity |

The data in Table 1 highlights several critical concepts. For acetaminophen, the diffusion coefficient ((D)) decreases by several orders of magnitude when moving from a conventional solvent (ethanol) to polymer melts (PEGs) [23]. This drastic reduction in molecular mobility directly correlates with a significantly prolonged induction time for the SMPT, demonstrating that the transformation kinetics can be "tuned" by selecting dispersants with specific physicochemical properties, such as viscosity.

The case of tegoprazan illustrates that solvent properties beyond viscosity, such as polarity (protic vs. aprotic), are also critical. Protic solvents like methanol favor the direct crystallization of the stable Polymorph A, while aprotic solvents like acetone can promote the transient formation of a metastable form (Polymorph B) before its transformation, underscoring the role of solvent-mediated hydrogen bonding in guiding polymorphic outcomes [4].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating SMPTs

A robust understanding of SMPT mechanisms requires the application of complementary analytical techniques. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

In Situ Raman Spectroscopy for Monitoring SMPT Induction Times

This protocol is used to monitor the real-time transformation of a metastable polymorph in a solvent or melt, as demonstrated in the study of acetaminophen in PEG melts [23].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a physical mixture of the metastable polymorph (e.g., ACM Form II) and the polymer (e.g., PEG). Gently grind using a mortar and pestle to achieve a homogeneous mixture without inducing phase transformation via mechanical stress.

- Experimental Setup: Place the physical mixture in a temperature-controlled hot stage (e.g., Linkam LTS 420). Couple the hot stage with a Raman spectrometer (e.g., Kaiser RXN2 Multichannel Raman Analyzer) equipped with a 785 nm laser in a 180° backscattering geometry.

- Data Collection:

- For isothermal profiles, equilibrate the sample at the desired process temperature ((T)). Collect spectra continuously with parameters such as 28 s exposure time and 30 s sampling interval.

- Monitor characteristic Raman shifts that distinguish the polymorphic forms (e.g., specific peaks for ACM I and II).

- Data Analysis: The induction time for the SMPT is identified as the time interval at the constant temperature (T) between the start of the experiment and the first detectable appearance of the signature Raman peaks of the stable form (e.g., ACM I).

Slurry Experiments and Kinetic Modeling with the Avrami Equation

This method is used to quantify the transformation kinetics of a metastable form in a suspension, as applied to tegoprazan [4].

- Slurry Preparation: Suspend the metastable solid form (e.g., TPZ amorphous or Polymorph B) in a selected solvent (e.g., methanol, acetone, water) under constant agitation.

- Time-Dependent Sampling: At predetermined time intervals, extract slurry samples.

- Phase Analysis: Isolate the solid phase from each sample via filtration and rapidly characterize it using Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) to quantify the proportion of each polymorphic form present.

- Kinetic Modeling: Model the conversion data using the Kolmogorov–Johnson–Mehl–Avrami (KJMA) equation [4] [24]:

( X = 1 - \exp(-kt^n) )

where:

- (X) is the volume fraction of the new stable phase.

- (k) is the Avrami rate constant.

- (n) is the Avrami exponent, related to the transformation mechanism.

- (t) is time. Fitting the experimental data to this model allows for the derivation of empirical rate parameters that describe the transformation kinetics.

Visualization of SMPT Mechanisms and Workflows

The SMPT Mechanism and Kinetic Influence Factors

Integrated Workflow for SMPT Risk Assessment and Control

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of SMPTs relies on a suite of specialized reagents and analytical tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions in a typical SMPT research workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SMPT Investigations

| Item / Solution | Function in SMPT Research | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Melts (e.g., PEGs) | Acts as a high-viscosity, nonconventional solvent to study and control molecular mobility and induction times [23]. | Investigating the slowed ACM II→I transformation in PEG 4000 vs. ethanol [23]. |

| Protic & Aprotic Solvents | Screens for solvent-specific conformational bias and hydrogen bonding that dictate polymorphic nucleation pathways [4]. | Differentiating TPZ Polymorph A (methanol) vs. B (acetone) outcomes [4]. |

| In Situ Raman Spectrometer | Provides real-time, molecular-level monitoring of polymorphic conversion in suspensions or melts without needing to isolate solids [23]. | Measuring the induction time for ACM SMPT in a PEG melt at a set temperature [23]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Determines thermodynamic stability, eutectic points, and phase diagrams for API-polymer/dispersant systems [23]. | Elucidating the phase diagram of ACM I/II with PEG to understand stability domains [23]. |

| KJMA Kinetic Model | A phenomenological equation used to model and quantify the kinetics of phase transformation from experimental data [4] [24]. | Fitting the conversion profile of TPZ Polymorph B to A to derive rate constants [4]. |

| Tautomer-Conformer Analysis (DFT-D/NMR) | Computational and experimental method to map solution-state conformational preferences that guide polymorph selection [4]. | Rationalizing the preferential crystallization of TPZ Polymorph A based on dominant solution conformers [4]. |

Analytical Techniques and Computational Tools for Polymorph Characterization

In pharmaceutical development, the solid form of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)—whether a specific polymorph, salt, co-crystal, or amorphous solid—directly influences critical properties including solubility, stability, dissolution rate, and bioavailability [25] [26]. The selection and control of the optimal solid form is therefore paramount for ensuring drug efficacy, safety, and quality. This guide provides a comparative analysis of four core analytical techniques—Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (SS-NMR), and Vibrational Spectroscopy—in the context of polymorphic stability research. For each technique, we summarize principles, applications, and experimental protocols to aid researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate methodologies.

Comparative Technique Analysis

The following table summarizes the core attributes and applications of each technique for solid-form analysis.

| Technique | Primary Principle | Key Polymorph Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Analyzes diffraction patterns from X-ray interaction with crystal lattices [25]. | - Polymorph identification & confirmation [25] [27]- Quantitative analysis of polymorphic mixtures [25]- Monitoring polymorphic transitions in manufacturing [25] | - Non-destructive [25]- High resolution & sensitivity for crystalline phases [25]- Provides a unique "fingerprint" for each crystal structure [25] | - Less sensitive to amorphous content- Can be affected by preferred orientation [28] | |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measures heat flow differences between sample and reference as a function of temperature. | - Identifying polymorphs with different melting points [27]- Studying phase transitions and thermal stability [27]- Observing amorphous-to-crystalline transitions [27] | - Requires small sample amounts [27]- Fast analysis- Directly measures thermodynamic properties | - Results can be influenced by experimental parameters (e.g., heating rate)- Overlapping thermal events can be complex to deconvolute | |

| Solid-State NMR (SS-NMR) | Probes local magnetic environments and molecular connectivity in solids using magic-angle spinning (MAS) and high-power decoupling [29]. | - Definitive polymorph identification & phase purity assessment [28] [30]- Detecting amorphous content & disorder [29]- Studying drug-excipient interactions [29] | - Non-destructive and non-invasive [29]- Inherently quantitative without need for standard curves [29]- Highly selective to specific nuclear sites [29] | - Requires significant expertise [29]- Can have long analysis times [29]- Lower sensitivity compared to other techniques [29] | |

| Vibrational Spectroscopy | Probes molecular vibrational modes via infrared absorption (IR) or inelastic light scattering (Raman). | - Polymorph identification based on molecular vibrations [26]- Quantitative analysis of polymorphic mixtures [26]- Chemical imaging and mapping of dosage forms [28] | - Minimal to no sample preparation required [26]- Non-destructive and fast [26]- Raman is suitable for aqueous systems | - IR can be hampered by water absorption- Fluorescence can interfere with Raman signals | - Spectra can be complex and require multivariate analysis |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) for Polymorph Quantification

Objective: To quantify the relative amount of polymorph A in a mixture with polymorph B.

Materials:

- PXRD Instrument: X-ray diffractometer with a Bragg-Brentano reflection or transmission geometry [28].

- Sample Holder: Standard flat plate holder or spinning capillary for transmission mode [28].

- Samples: Pure polymorph A, pure polymorph B, and the unknown mixture.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Data Collection:

- Mount the sample in the diffractometer.

- Set the X-ray source (typically Cu Kα radiation).

- Scan over a relevant 2θ range (e.g., 5° to 40°) with a step size of 0.05° and a counting time of 1-2 seconds per step [30].

- Data Analysis:

- Qualitative Identification: Compare the diffraction pattern of the unknown mixture to the reference patterns of pure polymorphs A and B [25].

- Quantitative Analysis (Rietveld Method):

- Use the known crystal structures of polymorphs A and B to generate calculated PXRD patterns [31].

- Perform a Rietveld refinement, where the calculated pattern for the mixture (a scaled sum of the individual patterns) is fitted to the experimental data.

- The scale factors derived from the refinement are used to calculate the weight fraction of each polymorph in the mixture.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for Polymorph Screening

Objective: To identify and characterize different polymorphic forms based on their thermal properties.

Materials:

- DSC Instrument: Standard or modulated-temperature DSC.

- Sample Pan: Hermetically sealed aluminum pans (pinhole lid if volatile decomposition is a concern).

- Reference: Empty, sealed aluminum pan.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Weigh 2-5 mg of the pure polymorph or sample into a DSC pan.

- Hermetically seal the pan.

- Data Collection:

- Place the sample and reference pans in the instrument.

- Equilibrate at a starting temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Heat the sample at a constant rate (e.g., 10°C/min) over a temperature range that covers all expected thermal events (e.g., up to 20°C above the expected melting point).

- Use an inert purge gas (e.g., nitrogen).

- Data Interpretation:

- Analyze the resulting thermogram for thermal events:

- Endotherms: Melting, desolvation.

- Exotherms: Crystallization, recrystallization.

- Identify the onset temperature and enthalpy (ΔH) of melting for each polymorph. Different polymorphs will exhibit distinct melting points and enthalpies of fusion [27].

- Analyze the resulting thermogram for thermal events:

Solid-State NMR (SS-NMR) for Phase Purity Assessment

Objective: To assess the phase purity of a crystalline API and detect low-level polymorphic impurities.

Materials:

- SS-NMR Spectrometer: NMR spectrometer equipped for solid-state analysis with magic-angle spinning (MAS) probes [29].

- Rotor: Zirconia MAS rotor (typically 4 mm or 7 mm outer diameter).

- External Standard: Compound for referencing chemical shifts, e.g., 3-methylglutaric acid (methyl peak at 18.84 ppm) [30].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Gently pack the powdered sample into the MAS rotor under ambient conditions [30].

- Ensure the rotor is tightly packed to ensure a homogeneous sample spin.

- Data Collection:

- Set the MAS spinning speed to a sufficiently high rate (e.g., 10-15 kHz) to minimize spinning sidebands that can complicate the spectrum [29].

- Use cross-polarization (CP) with magic-angle spinning to enhance signal from low-abundance nuclei like 13C [30] [29].

- Apply high-power 1H decoupling (e.g., SPINAL-64 sequence) during acquisition to narrow the resonances [30] [29].

- Accumulate a sufficient number of scans to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Data Interpretation:

- Examine the 13C SSNMR spectrum for the presence of small, unexpected peaks that do not correspond to the main API form [28].

- The number, position (chemical shift), and lineshape of the peaks provide a unique fingerprint for each polymorph, allowing for the identification of impurities [30] [29].

- Relaxation time measurements (1H T1) can be used to probe molecular mobility and predict physical stability [30].

Vibrational Spectroscopy for Polymorph Mapping in Tablets

Objective: To determine the spatial distribution and polymorphic form of an API within a solid dosage form.

Materials:

- Confocal Raman Microscope: Dispersive or FT-Raman microscope with a motorized stage [28].

- Sample: Cross-sectioned tablet mounted on a microscope slide.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Carefully cross-section the tablet to expose an interior surface.

- Mount the section on a microscope slide to ensure stability during mapping.

- Method Development:

- Using a microscope, focus on the sample surface.

- Identify a characteristic Raman peak unique to the API that does not overlap with excipient peaks.

- Define the mapping area (e.g., 280 x 280 μm) and set the spatial resolution (step size, e.g., 2-10 μm) and spectral acquisition time per point [28].

- Data Collection & Analysis:

- Initiate the automated mapping sequence. The instrument will collect a full Raman spectrum at each point on the defined grid.

- Use multivariate analysis software to generate chemical images based on the intensity of the pre-selected API characteristic peak.

- The resulting chemical map will visually represent the distribution and, by extension, confirm the consistency of the polymorphic form of the API throughout the formulation [28].

Integrated Workflow for Polymorph Stability Research

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow integrating these four techniques for comprehensive polymorphic stability and formulation analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The table below lists essential materials and reagents commonly used in solid-state analysis of pharmaceutical polymorphs.

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Crystalline Standards | Essential reference materials for PXRD, DSC, and SS-NMR to confirm polymorph identity and for quantitative method development [4]. |

| MAS Rotors (Zirconia) | Sample holders for Solid-State NMR that withstand high spinning speeds for magic-angle spinning [30]. |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Enable direct, non-destructive sampling for FTIR spectroscopy in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode [28]. |

| Capillaries (Glass/Quartz) | Used for PXRD analysis in transmission geometry to minimize preferred orientation effects [28]. |

| Hermetic DSC pans | Contain samples during Differential Scanning Calorimetry to prevent vaporization and control the sample environment. |

| Reference Materials (e.g., 3-methylglutaric acid) | Provide a known chemical shift reference for calibrating Solid-State NMR spectrometers [30]. |

In the field of pharmaceutical development, the precise quantification of analytes in mixtures is a cornerstone of reliable research, particularly in the critical area of polymorphic stability. Different solid forms of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) can exhibit vastly different physicochemical properties, including solubility, dissolution rate, and ultimately, bioavailability [32]. The ability to detect and quantify these forms at low concentrations is not merely an analytical exercise; it is a fundamental requirement for ensuring drug product consistency, stability, and efficacy [33] [34].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the fundamental figures of merit—the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)—focusing on their calculation and application in the analysis of mixtures. Within the context of polymorphic form research, controlling these forms is paramount. The emergence of a previously unknown, more stable polymorph can lead to dramatic consequences, including changes in product performance and even product recall, as famously experienced with ritonavir [4] [33]. Therefore, robust analytical methods with well-characterized sensitivity are essential tools for mitigating the risk of such "disappearing polymorphs" and ensuring the development of a stable, marketable drug product [34].

Core Definitions and Regulatory Significance

The Limit of Blank (LoB), Limit of Detection (LoD), and Limit of Quantification (LoQ) are distinct tiers describing the smallest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably measured by an analytical procedure [35].

- Limit of Blank (LoB): The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested. It is defined as

LoB = mean_blank + 1.645(SD_blank), representing the 95th percentile of blank measurements [35]. - Limit of Detection (LoD): The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the LoB. It accounts for the variability of both the blank and a low-concentration sample, calculated as