Parallelized Batch Reactors in Organic Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery and Optimization through High-Throughput Experimentation

This article explores the paradigm shift in organic synthesis driven by the parallelization of batch reactors.

Parallelized Batch Reactors in Organic Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery and Optimization through High-Throughput Experimentation

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift in organic synthesis driven by the parallelization of batch reactors. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) platforms, combined with advanced optimization algorithms like Bayesian Optimization, are revolutionizing process development and reaction screening. We cover the foundational principles of multi-reactor systems, methodological implementations using commercial and custom platforms, sophisticated troubleshooting and optimization strategies to navigate complex constraints, and finally, a rigorous validation of these approaches through comparative case studies. The synthesis conclusively demonstrates how parallelization accelerates lead optimization, reduces material consumption, and enhances the sustainability of pharmaceutical R&D.

The Principles and Power of Parallelization: Unlocking High-Throughput in Organic Synthesis

Application Notes

Multi-Reactor Systems in High-Throughput Experimentation

Multi-Reactor Systems (MRS) are engineered platforms that enable the parallel execution of chemical reactions under elevated temperatures and pressures, forming the physical backbone of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) in modern research laboratories. These systems allow researchers to rapidly screen catalysts, optimize reaction conditions, and explore chemical space more efficiently than traditional sequential approaches. By conducting multiple experiments simultaneously, MRS dramatically accelerates data generation, reducing the time required for reaction optimization from months to weeks while improving statistical reliability through parallel testing. The fundamental principle involves using multiple miniature reactors operating in parallel, each capable of independent or coordinated control of critical reaction parameters.

These systems have proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development and organic synthesis research, where they enable comprehensive investigation of reaction variables including temperature, pressure, catalyst loading, and reactant concentrations. The integration of MRS with automated sampling and analysis technologies has further enhanced their utility, creating closed-loop systems for autonomous reaction optimization. This approach has transformed traditional trial-and-error methodologies into systematic, data-rich experimentation strategies.

Hierarchical Parameter Constraints in Experimental Design

Hierarchical parameter constraints represent a sophisticated computational framework for managing complex experimental spaces in high-throughput experimentation. In the context of parallel reactor systems, these constraints enforce logical relationships between experimental parameters, ensuring that only chemically meaningful combinations are tested. This approach prevents wasted resources on nonsensical parameter combinations and focuses experimental effort on promising regions of the chemical space.

The mathematical foundation for hierarchical constraints lies in defining conditional parameter relationships where certain parameters only become relevant when specific parent parameters take particular values. For example, the choice of a catalyst ligand may only be meaningful when a specific metal catalyst is selected. This creates a tree-like parameter structure that mirrors chemical intuition while reducing the dimensionality of the optimization problem. In computational implementation, this can be achieved through Bayesian hierarchical modeling with parameter constraints that restrict the search space to chemically plausible regions.

Equipment Specification and Selection

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Reactor Systems

The selection of an appropriate MRS requires careful consideration of reactor configuration, control capabilities, and application requirements. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of standard and custom reactor systems based on commercial specifications.

Table 1: Comparison of Standard and Custom Multi-Reactor System Configurations

| Feature | 5000 Multiple Reactor System (MRS) | 2500 Micro Batch System (MBS) | Custom Parallel Reactor Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Reactors | 6 | 3 | Typically 2-16 |

| Reactor Volume | 45 mL or 75 mL | 5 mL or 10 mL | Any volume (commonly 50mL-1000mL) |

| Control System | 4871 (HC900)-based | 4848MBS | Typically 4871-based |

| Agitation Method | Stir bar | Stir bar | Magnetic drive |

| Individual Speed Control | No | No | Yes |

| Individual Heater Control | Yes | No | Yes |

| Gas Supply Manifold | Yes | Yes | Available |

| Cooling Water Manifold | No | No | Available |

| Optional Internal Cooling | Yes | No | Yes |

| Optional Liquid Sampling | Yes | No | Yes |

| Optional Pressure Control | No | No | Yes |

| Typical Applications | Catalyst screening, process optimization, combinatorial chemistry | Small-scale screening, limited material availability | Custom applications, specialized materials, complex processes |

Advanced Configuration Options

Custom MRS configurations offer significant advantages for specialized research applications. These systems support magnetic drive agitation with alternate geometries (anchor, spiral, gas entrainment) for handling high-viscosity mixtures or slurries, which are challenging for standard stir bar systems. Additionally, custom systems can incorporate advanced features such as individual pressure control, mass flow controllers for precise gas addition, and integrated cooling manifolds for exothermic reactions. The flexibility in reactor material selection (including corrosion-resistant alloys like Alloy 400 and C276) enables operation with diverse chemical substrates, including those involving highly corrosive environments or specialized reaction conditions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Parallel Catalyst Screening Using MRS

Objective: Systematically evaluate six transition metal catalysts for hydrogenation of aromatic substrates using a Parr 5000 Multiple Reactor System.

Materials and Equipment:

- Parr 5000 MRS with six 75 mL reactors

- Hydrogen gas supply with pressure regulation

- Temperature control system

- Sampling apparatus

- Analytical equipment (GC-MS or HPLC)

Procedure:

- Reactor Preparation: Clean and dry all six reactor vessels. Install appropriate gaskets and ensure proper sealing surfaces.

- Reaction Setup: Charge each reactor with 30 mL of substrate solution (0.1 M in appropriate solvent) and 50 mg of different catalyst materials.

- System Assembly: Mount reactors onto the MRS base unit and connect to gas manifold. Verify all connections are pressure-tight.

- Purging Procedure: Purge each reactor three times with inert gas (N₂) at 50 psi, then pressurize with H₂ to target reaction pressure (200-1000 psi).

- Temperature Programming: Set individual reactor temperatures according to experimental design (e.g., 50°C, 75°C, 100°C, 125°C, 150°C, 175°C).

- Initiation: Start agitation simultaneously across all reactors at 500 RPM.

- Monitoring: Record pressure and temperature data at 5-minute intervals throughout the 4-hour reaction period.

- Sampling: At predetermined timepoints (30, 60, 120, 240 minutes), extract 0.5 mL samples from each reactor for analysis.

- Termination: After 4 hours, cool reactors to room temperature and slowly vent pressure.

- Workup: Recover reaction mixtures and analyze conversion and selectivity by GC-MS.

Data Analysis: Calculate conversion rates and selectivity for each catalyst at different temperatures. Plot temperature versus conversion to identify optimal catalyst-temperature combinations for further optimization.

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Parameter Optimization with Constrained Experimental Space

Objective: Optimize a photoredox catalytic system using hierarchical parameter constraints to efficiently explore the experimental space.

Materials and Equipment:

- Multi-well photoreactor system (24-96 well capacity)

- Automated liquid handling system

- Photocatalyst library

- Substrate and reagent solutions

- Analytical platform (LC-MS or HPLC)

Procedure:

- Primary Parameter Definition: Identify independent parameters: photocatalyst type (PC1-PC8), base concentration (0.1-2.0 equiv.), solvent composition (ACN, DMF, DMSO), and light wavelength (365-450 nm).

- Constraint Implementation: Establish hierarchical constraints:

- IF photocatalyst = PC1 THEN solvent ≠ DMSO (incompatibility constraint)

- IF base concentration > 1.0 equiv. THEN light wavelength = 450 nm (reactivity constraint)

- IF solvent = ACN THEN base concentration range = 0.5-1.5 equiv. (solubility constraint)

- Experimental Design Generation: Use statistical software to create a D-optimal experimental design incorporating the defined constraints.

- Plate Preparation: Program automated liquid handler to dispense reagents according to the experimental design into a 96-well photoreactor plate.

- Reaction Execution: Seal plate and initiate simultaneous irradiation under controlled temperature (25°C) for 12 hours.

- Analysis: Quench reactions and analyze yields using high-throughput LC-MS.

- Model Building: Fit response surface models to the data, respecting the hierarchical constraint structure.

- Validation: Confirm model predictions by testing 5-10 additional constraint-compliant conditions.

Computational Implementation: The hierarchical constraints can be implemented programmatically using Bayesian optimization frameworks with parameter constraints that restrict the search space. For continuous parameters, this involves defining valid ranges conditional on other parameter values, while for categorical parameters, it requires defining conditional dependencies between parameter choices.

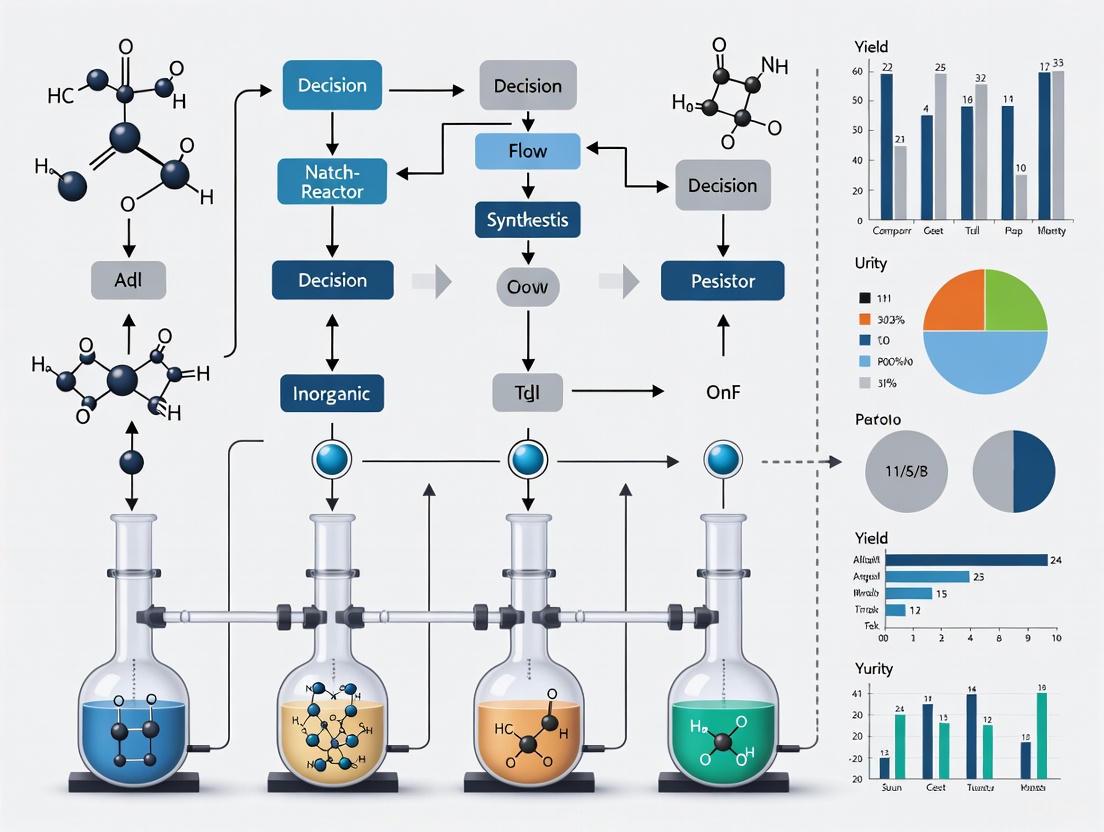

Visualization of System Architecture

Hierarchical Parameter Selection Logic

Diagram Title: Hierarchical Parameter Constraint Logic

MRS Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: MRS Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MRS Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alloy C276 Reactors | Corrosion resistance for harsh chemical environments | Essential for reactions involving halides, strong acids, or other corrosive media at elevated temperatures |

| Magnetic Drive Agitation | Superior mixing for high-viscosity or slurry systems | Enables use of specialized impellers (anchor, spiral) for challenging reaction mixtures |

| Gas Burette Option | Precise measurement of gas consumption/production | Critical for hydrogenation, hydroformylation, and other gas-liquid reactions |

| Mass Flow Controllers | Controlled gas addition and monitoring | Enables precise stoichiometry in gas-consuming reactions |

| Internal Cooling Coils | Temperature control for exothermic reactions | Prevents thermal runaway in rapid polymerization or highly exothermic reactions |

| Auto-sampling Devices | Automated reaction monitoring | Enables kinetic profiling without manual intervention, improves reproducibility |

| Pressure Control System | Maintains constant reaction pressure | Essential for reactions with volatile components or precise pressure requirements |

| Multiple Gas Manifold | Flexible gas switching capabilities | Enables sequential or mixed gas reactions (e.g., CO/H₂ mixtures) |

Implementation Considerations

Integration of MRS with Hierarchical Constraints

The synergy between physical MRS platforms and computational hierarchical constraint systems creates a powerful framework for efficient experimental optimization. The MRS generates high-quality, parallelized experimental data, while the hierarchical constraint system directs subsequent experimental designs toward chemically meaningful and promising regions of parameter space. This integrated approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development where material availability is often limited and experimental efficiency is paramount.

Implementation requires careful consideration of both physical and computational infrastructure. The reactor system must provide sufficient control and monitoring capabilities to ensure data quality, while the constraint management system must be flexible enough to encode complex chemical knowledge. Successful implementation typically involves collaboration between experimental chemists and computational researchers to develop appropriate constraint structures that balance chemical intuition with statistical efficiency.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent advances in MRS technology have expanded applications to specialized domains including photochemistry, electrochemistry, and high-pressure catalysis. The combination of flow chemistry principles with MRS has enabled even greater throughput and experimental flexibility. Similarly, developments in Bayesian optimization with sophisticated constraint handling have improved the efficiency of hierarchical experimental design. Future developments will likely focus on increased automation, improved real-time analytics, and more sophisticated constraint learning systems that can automatically refine hierarchical constraints based on experimental outcomes.

Parallel synthesis represents a paradigm shift in experimental inorganic chemistry and materials science, enabling the simultaneous execution of multiple reactions to dramatically accelerate research and development cycles. This approach leverages specialized hardware components designed to maintain precise control over reaction parameters while facilitating high-throughput experimentation. The core hardware ecosystem encompasses liquid handling robots for precise reagent dispensing, parallel reactor blocks for conducting multiple synchronized reactions, and integrated robotic platforms that transfer samples between stations for fully autonomous operation. These systems have become indispensable in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to novel materials discovery, where rapidly generating and screening compound libraries is essential for innovation.

The fundamental architecture of a parallel synthesis platform typically integrates three primary stations: sample preparation, reaction execution, and product characterization. This configuration enables continuous, autonomous operation where robotic arms seamlessly transfer samples and labware between stations. The A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory described in Nature, exemplifies this integration, successfully synthesizing 41 novel inorganic compounds over 17 days of continuous operation through the combination of robotics, computational planning, and real-time characterization [1]. Such platforms demonstrate the powerful synergy between specialized hardware and intelligent software, reshaping traditional approaches to chemical synthesis.

Core Hardware Components

The hardware infrastructure for parallel synthesis consists of several interconnected systems, each serving a distinct function within the experimental workflow. These components work in concert to enable high-throughput experimentation with precise environmental control and minimal manual intervention.

Parallel Reactor Systems

Parallel reactor systems form the core of synthetic operations, providing controlled environments for multiple simultaneous reactions. These systems vary in capacity, configuration, and specialization to accommodate diverse research requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Parallel Reactor Systems

| System Name | Reactor Capacity | Temperature Range | Pressure Capacity | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolyBLOCK 4 [2] | 4 positions (up to 500 mL) | -40°C to +200°C | Ambient | Independent temperature and agitation control per zone |

| PolyBLOCK 8 [2] | 8 positions (up to 120 mL) | -40°C to +200°C | Ambient | Small footprint, multiple vessel compatibility |

| Parr Parallel System [3] | 6 × 25 mL reactors | Up to 350°C | 3000 psi (200 bar) | High-pressure capability, automated liquid sampling |

| Asynt MULTI Range [4] | Up to 3 RBFs (5-500 mL) or 27 vials | Dependent on hotplate | Ambient | Accommodates flasks and vials, uniform stirring |

| Asynt OCTO [4] | 8 positions | Dependent on hotplate | Ambient | Inert atmosphere capability |

Specialized Reaction Systems

Beyond conventional heating and stirring, specialized reactor systems enable parallel execution of advanced synthetic methodologies:

Parallel Photochemistry: Systems like the Illumin8 (8 positions) and Lighthouse (3 positions) provide controlled irradiation for photochemical reactions, with options for heating, cooling, and inert atmosphere [4]. These systems ensure equal irradiation across all reaction vials through precise LED positioning.

Parallel Electrochemistry: Reactors such as the ElectroRun enable screening of different electrode materials and solution conditions under consistent, repeatable conditions [4]. These systems power multiple electrochemical cells in series while maintaining independent control over experimental variables.

Parallel Pressure Chemistry: Systems including the Quadracell (4 position) and Multicell (10 position) facilitate high-pressure reactions such as hydrogenation or carbonylation [4]. These reactors incorporate safety features like pressure release valves and burst disks while enabling rapid screening of challenging reaction pathways.

Automation and Robotics Infrastructure

Automated components handle material transfer and sample processing between experimental stages:

Liquid Handling Robots: Automated pipetting systems provide precise reagent dispensing across multiple reaction vessels, minimizing volumetric errors and ensuring reproducibility.

Robotic Transfer Arms: These systems transport samples and labware between preparation, reaction, and characterization stations, enabling continuous operation [1].

Powder Dispensing and Milling: For inorganic solid-state synthesis, automated stations handle precursor powders, including milling operations to ensure optimal reactivity between solid precursors with diverse physical properties [1].

Characterization and Analysis Integration

Real-time analysis is critical for autonomous operation and rapid optimization:

In-Line Spectroscopy: Systems often incorporate XRD, Raman, or FTIR capabilities for immediate reaction monitoring and phase identification [1].

Automated Sampling: Systems like the Parr 4878 Automated Liquid Sampler enable sequential collection of liquid samples under full reactor pressure, automatically clearing sampling lines between collections [3].

ML-Driven Analysis: Platforms like the A-Lab use machine learning models to interpret XRD patterns, extracting phase and weight fractions of synthesis products through automated Rietveld refinement [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of parallel synthesis requires carefully selected reagents and materials that enable reproducible, high-throughput experimentation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Parallel Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Starting materials for solid-state synthesis | Inorganic oxides and phosphates for novel material discovery [1] |

| Alumina Crucibles | Reaction vessels for high-temperature synthesis | Solid-state synthesis in box furnaces [1] |

| Diverse Electrodes | Anode/cathode materials for parallel electrochemistry | Screening electrode performance in the ElectroRun system [4] |

| Interchangeable Wavelength Modules | Specific light emission for photochemical reactions | Tuning reaction conditions in the Illumin8 photoreactor [4] |

| Catalyst Libraries | Accelerating reaction kinetics | High-throughput screening of heterogeneous catalysts [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Solid-State Synthesis of Novel Inorganic Materials

This protocol outlines the autonomous synthesis of novel inorganic powders using the A-Lab platform [1], which successfully synthesized 41 novel compounds from 58 targets.

Materials and Equipment:

- Robotic powder dispensing station

- Three integrated robotic stations for preparation, heating, and characterization

- Four box furnaces

- Alumina crucibles

- X-ray diffractometer with automated sample handling

- Precursor powders (composition depends on target material)

Procedure:

- Target Identification: Select thermodynamically stable target materials using ab initio phase-stability data from computational databases (e.g., Materials Project).

- Precursor Selection: Generate up to five initial synthesis recipes using machine learning models trained on historical literature data. The model assesses target "similarity" through natural-language processing of synthesis databases.

- Temperature Optimization: Determine optimal synthesis temperature using ML models trained on heating data from literature.

- Automated Preparation:

- Dispense and mix precursor powders using automated powder handling station.

- Transfer mixture into alumina crucibles using robotic arms.

- Reaction Execution:

- Load crucibles into box furnaces using robotic transfer system.

- Execute thermal treatment with programmed temperature profile.

- Allow samples to cool automatically.

- Product Characterization:

- Transfer samples to XRD station using robotic arms.

- Grind samples into fine powder using automated grinder.

- Acquire XRD patterns.

- Analyze patterns using probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures.

- Confirm phases with automated Rietveld refinement.

- Active Learning Optimization:

- If yield is <50%, employ ARROWS3 active learning algorithm.

- Algorithm integrates computed reaction energies with observed outcomes.

- Proposes improved synthesis routes avoiding intermediates with small driving forces.

- Repeat steps 4-6 until target yield is achieved or recipes exhausted.

Notes:

- The protocol emphasizes avoiding intermediate phases with small driving forces (<50 meV per atom) to prevent kinetic limitations.

- The system continuously builds a database of pairwise reactions to preemptively eliminate unsuccessful synthesis routes.

Protocol 2: Parallel Optimization of Reaction Conditions Using PolyBLOCK System

This protocol describes using parallel reactor systems for high-throughput optimization of synthetic parameters, particularly useful for pharmaceutical applications and catalyst development [2].

Materials and Equipment:

- PolyBLOCK 4 or 8 reactor system

- Appropriate reaction vessels (1 mL HPLC vials to 250 mL flasks)

- Precursor solutions or suspensions

- Temperature control unit

- Independent agitation system

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Define experimental parameter space (temperature, concentration, catalyst loading, etc.).

- Program temperature gradients across reactor zones (up to 100°C difference between zones).

- System Setup:

- Select appropriate reaction vessels based on scale (1-500 mL).

- Install vessels in PolyBLOCK reactor positions.

- Configure independent temperature setpoints for each zone (-40°C to 200°C).

- Program individual agitation rates (250-1500 rpm) for each position.

- Reaction Execution:

- Dispense reaction mixtures into respective vessels.

- Initiate parallel heating and stirring according to programmed parameters.

- Monitor reaction progress through in-line analytics if available.

- For extended operations, utilize pre-programmed overnight procedures.

- Sampling and Analysis:

- Extract samples at predetermined timepoints.

- Analyze products using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC, GC, NMR, etc.).

- Correlate reaction outcomes with parameter variations.

- Data Integration:

- Compile results across all parallel experiments.

- Identify optimal reaction conditions through statistical analysis.

- Use findings to refine subsequent experimental designs.

Notes:

- The system's flexibility allows use of different glassware sizes within the same block, enabling scale-up studies using identical equipment and procedures.

- Independent control over each reaction zone enables comprehensive Design of Experiments (DoE) approaches within a single run.

Workflow Visualization

Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for autonomous materials synthesis, showcasing the continuous loop between computational prediction, robotic execution, characterization, and active learning optimization.

Hardware Integration Architecture

This diagram depicts the physical hardware configuration and material flow within an autonomous laboratory, highlighting the coordination between robotic components and stationary stations.

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) has revolutionized inorganic synthesis research by enabling the rapid parallelization of batch reactor experiments. This approach accelerates discovery and optimization processes by allowing researchers to systematically explore vast parameter spaces—including temperature, pressure, solvent systems, and stoichiometry—in a fraction of the time required by traditional sequential methods. The core principle of HTE involves conducting numerous experiments simultaneously under tightly controlled conditions, generating statistically significant data while conserving valuable reagents and resources. Within this domain, three platforms have established themselves as powerful tools for researchers: Chemspeed for automated synthesis and workflow integration, Zinsser Analytic for advanced liquid handling and synthesis automation, and Technobis Crystalline systems for specialized crystallization studies and formulation development. These systems provide the technological foundation for modern parallelized experimentation, each offering unique capabilities that address different aspects of the complex challenges faced in drug development and materials science research. By implementing these platforms, research facilities can standardize procedures, enhance data quality, and dramatically increase experimental throughput, ultimately shortening development timelines for new chemical entities and formulated products.

Platform Capabilities and Specifications

Chemspeed Technologies AG provides highly modular and scalable automation solutions designed to grow with research needs. Their platforms combine base systems with robotic tools, modules, reactors, and software to create tailored setups for specific workflow requirements [5]. Chemspeed's philosophy emphasizes starting with a compact benchtop system, such as the CRYSTAL platform for gravimetric solid dispensing, and seamlessly scaling up to fully automated, connected laboratories as research evolves [5] [6]. Their solutions are engineered to accelerate, standardize, and digitalize R&D and QC workflows, with flexibility, reliability, and reproducibility built into the core design. Chemspeed systems are trusted by leading industrial R&D centers, including the Clariant Innovation Center, which utilizes Chemspeed's HIGH-THROUGHPUT & HIGH-OUTPUT workflows for sample preparation (SWING), formulation (FORMAX), and process research and optimization (MULTIPLANT PRORES) [7].

Technobis Crystallization Systems (referred to in the search results as Crystallization Systems) offers specialized analytical instruments focused on crystallization and formulation research. Their Crystalline platform represents a significant advancement in this niche, combining temperature control, turbidity measurements, and real-time particle imaging with eight in-line high-quality digital visualization probes capable of reaching 0.63 microns per pixel resolution [8]. This integrated visual approach allows researchers to directly observe crystallization processes and access real-time particle size and shape information at milliliter scales. The system employs AI-based software analysis for enhanced process control and can be configured with real-time Raman spectroscopy for comprehensive polymorph characterization [8]. Their Crystal16 instrument serves as a multi-reactor crystallizer for medium-throughput solubility studies, featuring 16 reactors at 1mL volumes with integrated transmissivity technology for generating solubility curves and screening crystallization conditions [9].

Zinsser Analytic provides a modular state-of-the-art liquid handler robotic system that combines sophisticated liquid handling with robotic manipulation. Their platform features a unique design that integrates robotic and liquid handling functionality into a robotic arm that glides on an x-rail to access rack modules [10]. The system is notable for its high working speed, rapid arm movements, and compact syringe pump, making it significantly faster than many traditional liquid handling systems. The platform can be configured with various tools that extend capabilities beyond standard pipetting, including capping/decapping vials, working with viscous liquids, and powder handling [10]. The Zinsser Lissy system, utilized by research institutions like Singapore's IMRE, enables high-throughput automated chemical solution synthesis and thin film deposition, featuring reactor blocks with heating and shaking (up to 96 vials, 200°C heating) with argon gas inertization capabilities [11].

Table 1: Technical Specifications Comparison of HTE Platforms

| Specification | Chemspeed | Technobis Crystalline | Technobis Crystal16 | Zinsser Analytic Lissy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactor/Well Count | Configurable | 8 reactors [8] | 16 reactors [9] | Up to 96 vials [11] |

| Working Volume | Flexible configurations | 2.5 - 5 mL [8] | 0.5 - 1.0 mL [9] | Not specified |

| Temperature Range | Application-dependent | -25°C to 150°C [8] | -20°C to 150°C [9] | Up to 200°C (block), 300°C (hot plate) [11] |

| Key Analytical Capabilities | Broad modular options | Particle imaging (0.63 µm/px), Turbidity, Real-time Raman [8] | Turbidity/Transmissivity [9] | UV-Vis, Photoluminescence plate reader [11] |

| Stirring Options | Overhead stirring | Overhead or stirrer bar [8] | Overhead or stirrer bar [9] | Shaking [11] |

| Special Features | "Plug and play" modularity, Gravimetric dispensing [7] | AI-based image analysis, Sealed visual probes [8] | Four independent temperature zones [9] | Spin-coating, Argon inertization [11] |

Application Focus and Workflow Integration

Each platform excels in specific application domains and offers distinct integration capabilities:

Chemspeed demonstrates exceptional versatility across a broad spectrum of chemical R&D applications. The platform is designed for seamless workflow integration, enabling transitions from ingredient dispensing to synthesis, process development, and formulation within a connected automated environment [7]. This end-to-end automation capability is particularly valuable for complex multi-step processes in specialty chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and materials science. The company's AUTOSUITE and ARKSUITE software platforms provide digital orchestration across systems and processes, facilitating data integrity and workflow standardization [5]. This comprehensive approach supports a wide range of applications, including catalyst research, battery materials development, and formulation science.

Technobis Crystallization Systems specializes deeply in solid-state and crystallization research. The Crystalline platform is specifically engineered to address critical challenges in polymorph screening, salt selection, and formulation optimization [8]. Its ability to provide real-time visual confirmation of crystallization events, combined with AI-based particle classification, offers researchers unprecedented insight into crystal formation and transformation processes. The platform's readiness for robotic integration future-proofs laboratories as they move toward greater automation [8]. The Crystal16 serves as an excellent tool for earlier-stage solubility profiling and metastable zone width determination, providing critical data for crystallization process design [9].

Zinsser Analytic focuses on automated synthesis and specialized deposition processes. The Lissy system's combination of liquid handling, reactor block heating and shaking, and spin-coating capabilities makes it particularly suitable for applications in materials science, including thin-film deposition and nanomaterials synthesis [11]. The system's flexibility in tool configuration enables adaptation to diverse synthesis protocols, while the argon inertization capability allows for handling air-sensitive compounds. This focused approach benefits research areas requiring precise control over reaction conditions and specialized processing techniques.

Table 2: Application Strengths and Experimental Focus

| Application Area | Chemspeed | Technobis Crystallization Systems | Zinsser Analytic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Dispensing & Weighing | Excellent (Gravimetric) [6] | Not Available | Limited (Powder Tools) [10] |

| Solution-Phase Synthesis | Excellent (Broad capabilities) [7] | Limited (Crystallization focus) | Excellent (High-throughput) [11] |

| Crystallization Studies | Good (With appropriate modules) | Excellent (Specialized platform) [8] [9] | Fair (Basic capability) |

| Polymorph/Salt Screening | Good | Excellent (Visual & Raman) [8] | Limited |

| Formulation Development | Excellent (FORMAX platform) [7] | Excellent (Formulation visualization) [8] | Limited |

| Thin Film Deposition | Limited | Not Available | Excellent (Spin-coating) [11] |

| Process Optimization | Excellent (MULTIPLANT PRORES) [7] | Good (Crystallization processes) | Good (Synthesis processes) |

Application Notes for Batch Reactor Parallelization

Automated Parallel Solubility Profiling and Metastable Zone Width Determination

Objective: To rapidly determine compound solubility across multiple solvent systems and temperature profiles, while characterizing metastable zone widths (MSZW) to inform crystallization process design.

Background: Solubility data serves as a foundational element in pharmaceutical and specialty chemical development, influencing decisions from candidate selection to final process design [9]. The metastable zone width represents the temperature range in which a solution remains supersaturated without spontaneous nucleation, providing critical parameters for designing optimal cooling crystallization processes.

Platform: Technobis Crystal16 with CrystalClear software [9].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 10-100 mg of compound into each of 16 standard HPLC vials. Using an automated liquid handler or gravimetric dispenser (e.g., Chemspeed SWING) improves efficiency and accuracy for this step [7].

- Solvent Addition: Add 0.5-1.0 mL of selected solvents to each vial using gravimetric or volumetric methods. The Crystal16 accommodates four different temperature zones, allowing strategic grouping of solvents by expected boiling point or polarity [9].

- Method Programming: Design a temperature profile in the CrystalClear software. A standard method includes:

- Heat to 10°C above the expected dissolution temperature (e.g., 50°C) at 20°C/min.

- Hold for 30 minutes to ensure complete dissolution.

- Cool to 10°C at a controlled rate of 0.5°C/min to gently induce supersaturation.

- Monitor transmissivity continuously throughout the cycle [9].

- System Tuning: Prior to the cooling ramp, use the software's tuning function on clear solutions to calibrate transmissivity detection, enhancing sensitivity to nucleation events [9].

- Data Analysis: The CrystalClear software automatically identifies clear points (dissolution) and cloud points (nucleation) from transmissivity data. It subsequently generates solubility curves, calculates MSZW, and can export reports including mg/mL solubility values [9].

Key Parameters:

- Stirring: 600-800 rpm using overhead stirring to prevent crystal attrition [9].

- Temperature Range: -20°C to 150°C using integrated air cooling [9].

- Replication: Perform in duplicate or triplicate to ensure statistical significance of MSZW data.

High-Throughput Parallel Synthesis with Automated Process Control

Objective: To execute multiple synthetic reactions in parallel with precise control over reaction conditions, reagent addition, and inert atmosphere for air-sensitive inorganic synthesis.

Background: Parallel synthesis accelerates the exploration of reaction parameters such as catalyst loading, ligand effects, and stoichiometry. Automation ensures reproducibility, enables the handling of hazardous reagents, and facilitates operation under controlled atmospheres.

Platform: Zinsser Analytic Lissy System with argon inertization [11].

Experimental Workflow:

- Reactor Setup: Load up to 96 reaction vials into the temperature-controlled reactor block. If necessary, perform a system purge with argon gas to establish an inert atmosphere [11].

- Reagent Dispensing: Program the liquid handling arm to dispense solvents, substrates, and catalysts according to the experimental design. The system's high-speed operation and flexible tool configuration allow for handling both standard and viscous liquids [10] [11].

- Reaction Initiation: For temperature-dependent reactions, initiate the process by heating the reactor block to the desired temperature (up to 200°C) with continuous shaking to ensure efficient mixing [11].

- Process Monitoring: Utilize the integrated MTP plate reader for in-process checks (UV-Vis, photoluminescence) by automatically transferring aliquots at specified time points [11].

- Reaction Quenching: Program the system to automatically add quenching agents or cooling to specific vials at predetermined times, enabling the study of reaction kinetics.

- Product Isolation: For thin-film applications, transfer reaction mixtures to the integrated spin-coater and hot-plate annealer (up to 300°C) for substrate deposition and processing [11].

Key Parameters:

- Atmosphere Control: Maintain argon blanket throughout for oxygen- or moisture-sensitive reactions.

- Heating/Shaking: Uniform heating to 200°C with concurrent shaking for efficient heat and mass transfer.

- Liquid Handling: Configurable with 8 or 16 dispensing tips, with optional grippers for labware manipulation [10].

Integrated Workflow from Solid Dispensing to Formulation

Objective: To demonstrate a completely automated, gravimetrically-controlled workflow from raw material dispensing through synthesis to final formulation, highlighting the integration capabilities of a modular automation platform.

Background: Integrating discrete unit operations eliminates manual transfer steps, reduces operator error, enhances reproducibility, and protects air- or moisture-sensitive intermediates. This is particularly valuable for optimizing complex multi-step processes in specialty chemicals and formulated products [7].

Platform: Chemspeed Configurable Automation Solution with SWING, FORMAX, and/or MULTIPLANT PRORES modules [7].

Experimental Workflow:

- Gravimetric Solid Dispensing: Initiate the workflow on a Chemspeed platform equipped with gravimetric solid dispensing technology (e.g., CRYSTAL POWDERDOSE). The system accurately weighs and dispenses multiple solid reagents directly into reaction vessels or vials located on a deck [6].

- Liquid Addition: Add liquid reagents and solvents gravimetrically using the platform's liquid dispensing capabilities, which can handle a range of viscosities [7].

- Parallel Synthesis/Process Optimization: Transfer the charged reactors to a synthesis module (e.g., MULTIPLANT PRORES). This module provides individually controlled reactors for parallel synthesis with precise temperature control, stirring, and the ability to add reagents during the process (e.g., antisolvent, seeds) [7].

- In-line Analysis and Decision Making: Integrate in-line analytics (e.g., PAT tools) if available. The software can be programmed to make decisions based on analytical data, such as extending a reaction time or adjusting temperature.

- Automated Formulation: Upon reaction completion, transfer the crude product or isolated intermediate to a formulation module (e.g., FORMAX). This module automates downstream processes such as dilution, mixing with excipients, pH adjustment, or emulsification to create the final formulated product [7].

- Data Digitalization: Throughout the workflow, the AUTOSUITE or ARKSUITE software captures and digitizes all process parameters and experimental data, ensuring complete data integrity and traceability [5].

Key Parameters:

- Modularity: "Plug and play" integration of different functional modules (dispensing, synthesis, formulation) [7].

- Gravimetric Control: Unrivalled overhead gravimetric dispensing for solids and liquids ensures high accuracy and records all additions [7].

- Software Integration: Centralized software control orchestrates the entire workflow across different modules, managing scheduling, robotic movements, and data aggregation [5].

Diagram 1: Integrated HTE Workflow for Batch Reactor Parallelization. This diagram illustrates the three-phase automated workflow for high-throughput experimentation, highlighting the critical feedback loops that enable adaptive experimentation and continuous process optimization.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of HTE platforms requires careful selection of compatible reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions and their specific functions within automated workflows for inorganic synthesis research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTE Platforms

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTE Workflows | Platform-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Anhydrous DMF, Acetonitrile, Alcohols, Chlorinated solvents | Reaction medium, crystallization solvent, cleaning agent [9] | Chemspeed/Zinsser: Compatibility with dispensing systems. Crystalline: Optimal transparency for turbidity measurements [8]. |

| Inorganic Precursors | Metal salts (e.g., CuCl₂, NaAuCl₄), Metal-organic frameworks | Primary reactants for inorganic synthesis and nanomaterial formation | Stability under robotic dispensing; compatibility with platform materials (e.g., resistance to corrosion). |

| Stabilizers/Ligands | Citrate, PVP, Thiols, Phosphines | Control nucleation, growth, and morphology of inorganic nanoparticles [8] | Viscosity considerations for liquid handling; solubility for stock solution preparation. |

| Antisolvents | Heptane, Ethers (added to saturated solutions) | Induce supersaturation for crystallization [8] [9] | Zinsser/Chemspeed: Automated addition during process. Crystalline: Proprietary caps enable automated addition [8]. |

| Calibration Standards | USP resolution standards, Sized microparticles | Validate imaging systems, turbidity probes, and liquid handling accuracy [8] | Crystalline: Required for validating AI-based image analysis (0.63 µm/px resolution) [8]. |

| Inert Atmosphere Sources | Argon gas tanks, Nitrogen generators | Prevent oxidation of air-sensitive catalysts and intermediates [11] | Zinsser Lissy: Integrated argon inertization capability [11]. Crystal16: Nitrogen purge port for low-temperature runs [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Nanoparticle Synthesis with Zinsser Lissy

Title: High-Throughput Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles with Varied Capping Agents

Objective: To systematically investigate the effect of different stabilizing agents on the size and morphology of gold nanoparticles using an automated parallel synthesis platform.

Materials:

- Precursor Solution: Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) in DI water (10 mM)

- Reducing Agent: Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) in ice-cold DI water (100 mM)

- Stabilizers: Trisodium citrate (1%), Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, 1%), Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, 0.1 M)

- Solvents: Deionized water

- Equipment: Zinsser Lissy system with temperature-controlled reactor block, liquid handling arm, and UV-Vis plate reader [11]

Procedure:

- System Initialization: Power on the Zinsser Lissy system and initialize the robotic arm. Purge the reactor block with argon for 10 minutes to create an inert atmosphere [11].

- Reaction Setup: Load 96 identical glass vials into the reactor block.

- Dispensing:

- Program the liquid handler to dispense 1.8 mL of DI water into each vial.

- Add 200 µL of HAuCl₄ precursor solution (10 mM) to each vial.

- Dispense varying volumes (10-100 µL) of different stabilizer solutions according to the experimental design matrix to different vial sets.

- Mixing and Equilibration: Activate the reactor block shaker for 5 minutes at 500 rpm to ensure homogeneous mixing. Heat the block to 25°C and allow temperature equilibration.

- Reaction Initiation: Rapidly dispense 50 µL of ice-cold NaBH₄ solution to each vial simultaneously using the multi-tip liquid handling arm to initiate nanoparticle formation.

- Kinetic Monitoring: Immediately after addition, transfer 200 µL aliquots from selected vials to a 96-well MTP at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min) for UV-Vis analysis to monitor plasmon resonance peak development [11].

- Termination: After 60 minutes, quench reactions by cooling the reactor block to 4°C.

Data Analysis: Characterize the final nanoparticles by analyzing the surface plasmon resonance peaks in UV-Vis spectra (peak position and width correlate with size and dispersity). Correlate the stabilizer type and concentration with the optical properties.

Protocol 2: Polymorph Screening of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)

Title: Integrated Workflow for Salt and Polymorph Screening Using Chemspeed and Technobis Crystalline

Objective: To automate the preparation and analysis of various API salts for polymorph identification and characterization.

Materials:

- API: Free base form of a drug compound

- Counter-Ions: Hydrochloric acid, phosphoric acid, succinic acid (in stoichiometric solutions)

- Solvents: Methanol, ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate

- Equipment: Chemspeed platform for dispensing and synthesis, Technobis Crystalline PV/RR with Particle View imaging and optional Raman spectroscopy [8] [7]

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation (Chemspeed):

- Use the gravimetric solid dispenser to accurately weigh the free base API into multiple vials.

- Dispense different solvents gravimetrically to create API stock solutions.

- Dispense stoichiometric amounts of acid solutions into separate vials.

- Salt Formation (Chemspeed):

- Transfer the API stock solution and acid solutions to a Chemspeed synthesis module.

- Initiate salt formation by mixing at ambient temperature with overhead stirring.

- Optionally, evaporate a portion of the solvent under controlled conditions to induce crystallization.

- Sample Transfer: Use the robotic arm to transfer the slurries or solutions to the pre-equilibrated reactors of the Technobis Crystalline PV/RR.

- Crystallization and Monitoring (Crystalline PV/RR):

- Program a temperature cycling profile (e.g., heat to 50°C, cool to 5°C) to promote crystallization.

- Activate all eight in-line particle view cameras (0.63 µm/px) to monitor crystal appearance in real-time [8].

- Simultaneously collect turbidity data and, if configured, real-time Raman spectra to identify polymorphic forms [8].

- AI-Based Image Analysis: Use the integrated AI software to automatically classify observed crystals by shape and size into different polymorph classes [8].

Data Analysis: Correlate visual data (crystal habit), turbidity profiles (clear and cloud points), and Raman spectra to identify distinct polymorphic forms and their formation conditions. Generate a comprehensive report mapping counter-ions and solvents to resulting solid forms.

Diagram 2: Automated Polymorph Screening Workflow. This protocol integrates automated synthesis with advanced analytical characterization to systematically map the solid-form landscape of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API).

The strategic implementation of commercial HTE platforms—Chemspeed, Zinsser Analytic, and Technobis Crystallization Systems—provides research organizations with powerful capabilities for accelerating inorganic synthesis and development. Chemspeed offers unparalleled flexibility and scalability for end-to-end workflow automation, from initial dispensing to final formulation. Zinsser Analytic delivers high-speed, specialized synthesis and deposition capabilities ideal for materials science applications. Technobis Crystallization Systems provides deep, application-specific focus on solid-state characterization and crystallization process understanding. The choice of platform depends heavily on the specific research goals: broad synthetic versatility and workflow integration point toward Chemspeed, specialized synthesis and thin-film applications align with Zinsser Analytic, and intensive solid-form and crystallization studies are best served by Technobis systems. Critically, these platforms are not mutually exclusive; a fully connected laboratory of the future may strategically integrate complementary technologies from multiple vendors to create a seamless, digitally-controlled ecosystem that maximizes throughput, data integrity, and research effectiveness across the entire product development pipeline.

The Role of Custom-Built and Low-Cost Automated Platforms for Specialized Workflows

The integration of custom-built and low-cost automated platforms is transforming specialized workflows in inorganic and organic synthesis research. Within the context of batch reactor parallelization, these platforms address the critical gap between high-throughput computational screening and experimental realization, enabling the rapid discovery and optimization of novel materials and molecules [1] [12]. The convergence of robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and purpose-built hardware creates Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) that automate repetitive tasks, enhance experimental reproducibility, and accelerate data generation [13]. This paradigm shift allows researchers to move beyond traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) methodologies, instead exploring vast chemical spaces efficiently through parallel experimentation [12]. The emerging concept of the "frugal twin"—a low-cost surrogate of a high-cost research system—further democratizes access to autonomous experimentation, making SDLs feasible for academic settings and lower-budget projects [13]. This article details the application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these platforms, with a specific focus on their impact in batch reactor-based synthesis for drug development and materials science.

Automated platforms for chemical synthesis vary widely in cost, complexity, and application. The table below summarizes representative examples, from low-cost "frugal twins" to advanced integrated systems.

Table 1: Overview of Automated Platforms for Chemical Synthesis

| Platform Name | Field | Primary Purpose | Estimated Cost (USD) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational ARES [13] | Education | 3D Printing & Titration | $250 - $300 | Very low-cost; for education and prototyping. |

| LEGO Low-cost Autonomous Science (LEGOLAS) [13] | Education | Titration | ~$300 | Built from low-cost components; hands-on SDL experience. |

| Cheap Automated Synthesis Platform [13] | Chemistry | Organic Synthesis | ~$450 | Low-barrier entry for automated synthesis. |

| A-Lab [1] | Materials Science | Solid-State Synthesis of Inorganic Powders | Not Specified | Fully autonomous; integrates AI, robotics, and active learning. |

| Custom High-Throughput Platform [12] | Organic Chemistry | Reaction Optimization & Library Generation | Varies (often high) | Uses microtiter plates; explores solvents, catalysts, reagents. |

| "The Chemputer" [13] | Chemistry | Organic Synthesis | ~$30,000 | High-cost, advanced system for complex synthesis. |

Application Notes: Implementation in Synthesis Workflows

The A-Lab for Inorganic Powder Synthesis

The A-Lab exemplifies a fully integrated SDL for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders. Its workflow demonstrates the synergy between computation, AI, and robotics [1].

Key Workflow Components:

- Target Identification: Targets are identified from large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from sources like the Materials Project [1].

- Recipe Generation: Initial synthesis recipes are proposed by natural-language models trained on historical literature data. A second ML model suggests heating temperatures [1].

- Active Learning: If initial recipes fail (yield <50%), an active learning algorithm (ARROWS³) proposes improved recipes by integrating computed reaction energies with observed outcomes, prioritizing pathways with larger driving forces [1].

- Experimental Execution: Robotic arms handle powder dispensing, mixing, and milling. Samples are heated in box furnaces and characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) [1].

- Outcome Analysis: ML models analyze XRD patterns to identify phases and quantify weight fractions, with results automated by Rietveld refinement [1].

Performance: In one continuous 17-day campaign, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 novel target compounds, demonstrating a 71% success rate and validating the effectiveness of AI-driven platforms for autonomous materials discovery [1].

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in Organic Synthesis

HTE employs miniaturization and parallelization to accelerate reaction optimization, compound library generation, and data collection for machine learning [12].

Key Workflow Components:

- Miniaturized Reaction Vessels: Reactions are conducted in parallel within microtiter plates (MTPs), typically at micro- or nanoliter scales [12].

- Automated Liquid Handling: Robotic dispensers are used for precise delivery of reagents, catalysts, and solvents, ensuring reproducibility and handling air-sensitive materials under inert atmospheres [12].

- In-Situ Reaction Monitoring: Advanced analytical techniques, such as mass spectrometry (MS), are integrated for high-throughput reaction analysis [12].

- Data Management: Emphasis is placed on managing data according to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) to maximize utility for ML [12].

Challenges and Solutions:

- Spatial Bias: Wells at the edge of MTPs can experience different conditions (e.g., temperature, light irradiation) compared to center wells. This is mitigated through careful plate design and calibration [12].

- Solvent Compatibility: Adapting aqueous-based HTS instrumentation to the diverse organic solvents requires hardware that is chemically resistant and accounts for varying surface tension and viscosity [12].

- Material Compatibility: Ensuring that all wetted parts (e.g., seals, tubing) are compatible with the broad range of chemicals used is crucial to prevent degradation and failure [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Optimization of a Catalytic Reaction in Batch Parallel Reactors

This protocol outlines the steps for using a custom low-cost HTE platform to optimize a model Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction.

1. Hypothesis and Plate Design:

- Objective: Identify the optimal combination of ligand and base for the coupling of 4-bromotoluene and phenylboronic acid.

- Variables: Screen 4 ligands (L1-L4) and 4 bases (B1-B4) in a single solvent (THF).

- Plate Map: Design a 4x4 matrix within a 96-well MTP, with each well containing a unique ligand/base combination. Include control wells.

2. Precursor and Reagent Preparation:

- Stock Solutions: Prepare solutions in an inert atmosphere glovebox:

- Palladium catalyst (e.g., Pd(dba)₂) in THF.

- Ligands (L1-L4) in THF.

- Bases (B1-B4) in THF.

- Substrates: Prepare separate solutions of 4-bromotoluene and phenylboronic acid in THF.

3. Automated Reaction Setup:

- Dispensing: Use an automated liquid handler to dispense:

- 100 µL of THF into each well.

- 10 µL of the Pd catalyst solution into each well.

- 10 µL of the appropriate ligand solution per the plate map.

- 10 µL of the appropriate base solution per the plate map.

- 10 µL of the 4-bromotoluene solution into each well.

- Mixing: Seal the plate and mix briefly on an orbital shaker.

- Initiation: Dispense 10 µL of the phenylboronic acid solution into each well to initiate the reaction.

4. Reaction Execution and Quenching:

- Heating: Transfer the MTP to a heated shaker block. Agitate at 60°C for 2 hours.

- Quenching: After the reaction time, automatically inject a fixed volume of a quenching solution (e.g., acidic methanol) into each well.

5. High-Throughput Analysis:

- Sampling: Use an autosampler to inject aliquots from each well into a UHPLC-MS system.

- Analysis: Quantify conversion and yield for each reaction condition based on calibrated UV response or mass detection.

6. Data Processing and Analysis:

- Automated Data Extraction: Use software to automatically extract analytical results and populate a data table linked to the plate map.

- Visualization: Generate a heat map visualizing reaction yield as a function of ligand and base identity to identify the optimal combination.

Protocol: Active Learning-Driven Synthesis Optimization (A-Lab model)

This protocol describes the closed-loop, active learning cycle for optimizing a solid-state synthesis, based on the methodology of the A-Lab [1].

1. Initialization with Literature-Based Recipe:

- Target Input: Define the target compound (e.g., a novel metal oxide).

- Precursor Selection: An NLP model trained on literature data proposes an initial set of solid precursors based on analogy to similar known materials [1].

- Condition Proposal: A second ML model suggests an initial firing temperature and duration [1].

2. Robotic Synthesis Execution:

- Powder Dispensing: A robotic arm dispenses and weighs precursor powders into an alumina crucible.

- Milling: The powder mixture is milled automatically to ensure homogeneity and reactivity.

- Heating: The crucible is transferred to a box furnace and heated under static air according to the proposed temperature profile.

3. Automated Characterization and Analysis:

- Sample Preparation: The robotic system transfers the cooled product to a grinder to create a fine powder for XRD.

- XRD Measurement: The sample is loaded and its XRD pattern is collected automatically.

- Phase Analysis: A probabilistic ML model analyzes the XRD pattern to identify crystalline phases and quantify the weight fraction of the target phase via automated Rietveld refinement [1].

4. Active Learning and Iteration:

- Decision Point: If the target yield is >50%, the process is successful. If not, the active learning algorithm (ARROWS³) is triggered [1].

- Algorithmic Redesign: The algorithm uses a growing database of observed pairwise solid-state reactions and thermodynamic data from the Materials Project to:

- A. Infer known reaction pathways to avoid redundant experiments.

- B. Propose a new precursor set or heating profile designed to avoid low-driving-force intermediates that kinetically trap the reaction [1].

- Loop Closure: The new recipe is executed robotically, and the cycle repeats until success or recipe exhaustion.

Diagram 1: A-Lab autonomous synthesis workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of automated synthesis platforms relies on a suite of essential reagents, materials, and software.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Workflows

| Item | Function / Role | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (MTPs) | Miniaturized reaction vessel for parallel experimentation. | Choose material (e.g., glass, polypropylene) for chemical and temperature compatibility with screened solvents and conditions [12]. |

| Solid Precursor Powders | Starting materials for solid-state reactions. | Purity, particle size, and reactivity are critical. Often require pre-drying and automated milling to ensure homogeneity [1]. |

| Palladium Catalysts (e.g., Pd(dba)₂) | Catalyze cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki-Miyaura). | Prepared as stock solutions in inert atmosphere for automated dispensing; concentration must be precise [12]. |

| Ligand Libraries | Modulate catalyst activity and selectivity in metal-catalyzed reactions. | Screened in combination with metals and bases in an HTE matrix design to find optimal pairs [12]. |

| Diverse Solvent Library | Explore solvent effects on reaction outcome. | Must account for solvent compatibility with automated liquid handling hardware (viscosity, vapor pressure) [12]. |

| Ab Initio Computational Data | Provides thermodynamic stability data for target materials and intermediates. | Used by platforms like the A-Lab for target selection and by active learning algorithms to compute reaction driving forces (e.g., from the Materials Project) [1]. |

| Historical Synthesis Literature Data | Trains NLP and ML models for initial precursor and condition suggestions. | Enables "human-like" reasoning by analogy, forming the knowledge base for the first experimental iteration [1]. |

Diagram 2: SDL components and data flow.

The transition from traditional batch processing to parallelized reactor systems represents a paradigm shift in organic synthesis research, particularly for pharmaceutical development. This evolution demands a refined approach to defining process objectives, moving beyond the single-minded pursuit of reaction yield to the simultaneous optimization of yield, purity, and selectivity. This tripartite objective is technically challenging yet critical for developing efficient, sustainable, and economically viable synthetic routes. In a parallelized batch reactor framework, where multiple experiments proceed concurrently, a well-defined optimization strategy is not merely beneficial—it is essential for leveraging the full potential of these advanced platforms [14] [15]. This document outlines the key objectives and provides detailed application notes for achieving these integrated goals, framed within the context of modern digital catalysis and high-throughput experimentation (HTE).

Background and Significance

Traditional optimization in organic synthesis has historically relied on one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) experimentation, an approach that is often labor-intensive, time-consuming, and incapable of capturing complex variable interactions [14]. The rise of lab automation and parallelized reactor systems enables a fundamentally different strategy. These systems, such as the REALCAT’s Flowrence unit featuring a hierarchy of fixed-bed reactors, allow for the synchronous exploration of a high-dimensional parametric space [15]. However, this capability introduces the challenge of hierarchical technical constraints, where parameters like a common feed composition or block-level temperature control must be considered alongside reactor-specific variables [15].

The core challenge in this environment is to navigate the intricate trade-offs between the primary objectives:

- Yield: The efficiency of the desired transformation, directly impacting material throughput and cost.

- Purity: The level of the target molecule relative to impurities and side-products, a critical determinant for downstream processing and regulatory approval in drug development.

- Selectivity: The preference for forming the desired product over other possible side-products, which is intrinsically linked to both yield and purity.

Failure to consider all three objectives simultaneously can result in processes that are high-yielding but generate intractable impurity profiles, or highly selective but impractically slow. The application of data-centric optimization methods, such as Bayesian optimization, is thus a significant step forward in digital catalysis, enabling researchers to efficiently balance these competing goals under complex constraints [15].

Key Methodologies for Simultaneous Optimization

The simultaneous optimization of multiple objectives requires sophisticated methodologies that can efficiently model and navigate the experimental space.

Bayesian Optimization (BO) and Process Constraints

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful machine learning framework for optimizing "black-box" functions that are expensive to evaluate, such as chemical reactions [15]. It operates by building a probabilistic surrogate model (often a Gaussian Process) of the objective function (e.g., a function combining yield, purity, and selectivity) and uses an acquisition function to intelligently select the next most promising experiments.

For multi-reactor systems, standard BO must be adapted to handle process constraints. The novel process-constrained batch Bayesian optimization via Thompson sampling (pc-BO-TS) and its hierarchical extension (hpc-BO-TS) have been developed for this purpose [15]. These methods are tailored for systems with layered parameters, such as a multi-reactor system where a common feed stream (a global constraint) feeds multiple blocks that have independent temperature control (a block-level constraint), which in turn feed individual reactors with variable catalyst mass (a reactor-specific constraint). The pc-BO-TS approach effectively balances exploration and exploitation under these constraints, often outperforming other sequential and batch BO methods [15].

Table 1: Key Components of Bayesian Optimization for Chemical Reaction Optimization

| Component | Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Model | A probabilistic model that approximates the expensive-to-evaluate objective function. | Gaussian Process (GP) |

| Acquisition Function | A function that determines the next experiment by balancing exploration (uncertain regions) and exploitation (promising regions). | Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), Thompson Sampling (TS) |

| Process Constraints | Technical limitations and fixed parameters inherent to the experimental setup. | Common feed composition, shared pressure in a reactor block, maximum safe temperature |

High-Throughput Automated Platforms

The practical implementation of these advanced optimization algorithms is enabled by high-throughput automated chemical reaction platforms [14]. These systems perform numerous experiments in parallel, rapidly generating the high-quality data required to build and refine the models used in BO. The synergy between automation and machine learning creates a closed-loop optimization cycle: the platform executes a batch of experiments designed by the algorithm, and the results are then fed back to the algorithm to design the next optimal batch [14]. This cycle dramatically reduces experimentation time and human intervention while synchronously optimizing multiple reaction variables.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, actionable protocol for conducting simultaneous optimization studies in a parallelized batch reactor system, using the synthesis of carbamazepine as a representative example [16].

Protocol 1: Kinetic Parameter Determination via Batch Experiments

Objective: To determine initial kinetic parameters (reactant orders, rate constants) for the primary and side reactions to inform the continuous process model.

Materials:

- Iminostilbene (ISB)

- Potassium Cyanate (KOCN)

- Acetic Acid (solvent)

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Conduct a series of batch reactions in a controlled laboratory reactor. Vary initial concentrations of ISB and KOCN independently across a predefined range.

- Sampling and Analysis: Withdraw samples at regular time intervals throughout the reaction.

- Analytical Techniques: Analyze samples using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to quantify the concentrations of CBZ, unreacted starting materials, and key impurities.

- Data Fitting: Fit the concentration-time data to proposed rate laws to determine the reaction orders with respect to ISB and KOCN, as well as the rate constants for the primary and major side reactions [16].

Protocol 2: Continuous Synthesis Optimization in a Parallel CSTR System

Objective: To optimize the yield, purity, and selectivity of CBZ in a system of two Continuous Stirred Tank Reactors (CSTRs) in series, based on the kinetic model.

Materials:

- ISB Solution: Prepared in acetic acid at concentrations above room temperature solubility, requiring a heated dissolution loop [16].

- KOCN Solution: Prepared in acetic acid.

- CSTR System: Two CSTRs in series with controlled feed streams, temperature, and agitation.

Methodology:

- System Configuration: Set up the two CSTRs in series. The outlet of the first reactor serves as the feed for the second reactor.

- Parameter Optimization based on BO: Using the kinetic model from Protocol 1 as a prior, a Bayesian optimization strategy is deployed to find optimal process conditions. Key variables to optimize include:

- KOCN Addition Split Ratio: The fraction of total KOCN added to the first CSTR versus the second CSTR [16].

- Residence Time: In each CSTR, controlled by the feed flow rate.

- Reaction Temperature: Of each CSTR.

- Evaluation of Objectives: For each set of conditions, the process is evaluated based on:

- Yield: Moles of CBZ produced per mole of ISB fed.

- Purity: Percentage of CBZ in the solid precipitate obtained after an integrated continuous precipitation step.

- Selectivity: Moles of CBZ produced per mole of ISB consumed.

- Iterative Refinement: The results from each experimental batch are used to update the Bayesian optimization algorithm, which then suggests a new batch of conditions to test, progressively moving towards the global optimum for the multi-objective function [15] [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Application in CBZ Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Iminostilbene (ISB) | Primary reactant, precursor to the carbamazepine structure. | Reacted with KOCN to form the CBZ molecule [16]. |

| Potassium Cyanate (KOCN) | Reactant, source of the carbamoyl group incorporated into CBZ. | Added in a split stream to two CSTRs in series to optimize yield and minimize impurities [16]. |

| Acetic Acid | Solvent medium for the imination reaction. | Chosen for its ability to dissolve reactants and facilitate the reaction kinetics [16]. |

| Ethanol | Solvent for purification via cooling crystallization. | Used to isolate the final CBZ product in the desired polymorphic form (Form III) and within impurity limits [16]. |

Workflow and Data Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for the simultaneous optimization of yield, purity, and selectivity, combining high-throughput experimentation with machine learning guidance.

Optimization Workflow Integrating BO and HTE

The logical relationships and data flow within a hierarchical multi-reactor system are complex. The following diagram details the constraint architecture.

Hierarchical Constraints in a Multi-Reactor System

Implementing Parallel Synthesis: From Workflow Design to Real-World Applications

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) has emerged as a transformative approach in organic synthesis and drug discovery, enabling the rapid parallel execution and analysis of numerous chemical reactions. By leveraging miniaturization, automation, and data-rich analysis, HTE accelerates reaction discovery, optimization, and the generation of diverse compound libraries. This protocol details the standard HTE workflow, framing it within the context of batch reactor parallelization for inorganic synthesis research. It provides a comprehensive guide to the experimental procedures, key technologies, and data management practices that underpin a robust HTE pipeline, drawing on current advancements in the field [12].

The HTE workflow is a structured, iterative cycle designed to maximize the efficiency of exploring chemical space. It begins with the strategic design of a reaction array, followed by its automated execution, comprehensive analysis, and finally, data management to inform subsequent experimentation cycles [17] [12].

- Reaction Design and Plate Layout: The initial phase involves defining the experimental question. Researchers select reagents from a digital chemical inventory, which automatically populates fields with molecular weights, SMILES strings, and other metadata [17]. The reaction array is then designed, either manually or using software algorithms, to efficiently populate a microtiter plate (e.g., 24, 96, 384, or 1536-well formats). This step strategically assigns different reagents, catalysts, and solvents to individual wells to explore a wide parameter space [17] [12].

- Instrument Control and Data Integration: Software platforms like

phactorandHTE OSact as the central nervous system of the workflow. They generate instructions for liquid handling robots, communicate with automated powder dispensers like the CHRONECT XPR, and funnel all resulting analytical data into visualization and analysis software such as Spotfire [18] [17] [19]. This creates a closed-loop system where data from one cycle directly informs the design of the next [17].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed, actionable methodologies for setting up and running a high-throughput screen, from initial preparation to data collection.

Protocol: Setting Up a 96-Well Plate Reaction Array for Catalyst Screening

Objective: To identify an optimal catalyst and ligand combination for a model transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction.

Materials and Reagents

- Model Reaction: Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of aryl halide and boronic acid.

- Plate Format: 96-well glass-lined microtiter plate with stir bars.

- Stock Solutions: Prepare in dry, degassed solvent (e.g., toluene, 1,4-dioxane).

- Aryl halide (0.1 M)

- Boronic acid (0.15 M)

- Base (e.g., K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃, 0.5 M aqueous solution)

- Catalysts & Ligands: Solid powders or stock solutions in a range of transition metal catalysts (e.g., Pd₂(dba)₃, Pd(OAc)₂, Ni(acac)₂) and ligands (e.g., PPh₃, SPhos, XPhos, DACH-phenyl Trost ligand).

Procedure

- Reaction Design:

- Using HTE software (e.g.,

phactor), design an 8x12 grid where rows vary the metal catalyst and columns vary the ligand. - Include control wells with no catalyst and/or no ligand.

- Using HTE software (e.g.,

Automated Powder Dosing:

- Load solid catalysts and ligands into an automated powder dosing system (e.g., CHRONECT XPR).

- Program the system to dispense precise masses (e.g., 0.5-2.0 mg) directly into the designated wells of the 96-well plate. The system can typically dispense 1 mg to several grams with high accuracy, achieving <10% deviation at sub-mg masses and <1% at >50 mg masses [19].

Liquid Handling:

- Using a liquid handling robot (e.g., Opentrons OT-2, Tecan Veya), dispense the following into each well:

- 100 µL of aryl halide stock solution (10 µmol).

- 100 µL of boronic acid stock solution (15 µmol).

- 50 µL of base stock solution (25 µmol).

- Top up with solvent to a final volume of 500 µL.

- Using a liquid handling robot (e.g., Opentrons OT-2, Tecan Veya), dispense the following into each well:

Reaction Execution:

- Seal the plate with a pressure-sensitive adhesive seal.

- Place the plate on a heated stirrer/hotplate within an inert atmosphere glovebox.

- Stir and heat the reactions at a defined temperature (e.g., 80°C) for 18 hours.

Quenching and Analysis:

- After the reaction time, quench the plate by adding a standard solution (e.g., containing an internal standard like caffeine).

- Dilute an aliquot from each well with acetonitrile in a new analysis plate.

- Analyze the plate using UPLC-MS. The output (e.g., a CSV file with peak integrations) is uploaded to the HTE software for visualization as a heatmap of conversion or yield [17].

Quantitative Performance of HTE Components

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Key HTE Technologies

| Technology | Key Metric | Performance Value | Protocol Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Powder Dosing [19] | Mass Dispensing Range | 1 mg to several grams | Dispensing solid catalysts and ligands. |

| Dispensing Accuracy (>50 mg) | < 1% deviation from target | Ensures precise stoichiometry for scale-up conditions. | |

| Dispensing Accuracy (sub-mg to low mg) | < 10% deviation from target | Critical for accurate catalyst loading at screening scale. | |

| Throughput (manual comparison) | ~5-10 min/vial manually vs. <30 min for a full experiment automated [19] | Drastically reduces setup time for a 96-well plate. | |