Overcoming Mass Transfer Limitations in Photocatalytic Systems: Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency and Scalability

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of mass transfer limitations, a critical bottleneck in scaling photocatalytic technology for environmental and energy applications.

Overcoming Mass Transfer Limitations in Photocatalytic Systems: Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency and Scalability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of mass transfer limitations, a critical bottleneck in scaling photocatalytic technology for environmental and energy applications. It explores the fundamental principles governing mass transfer in photocatalytic systems, examines advanced engineering strategies like surface and morphological modifications to enhance reactant flow, and introduces diagnostic tools for identifying rate-limiting steps. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with recent methodological advances and validation techniques, this review offers researchers and engineers a structured framework for designing next-generation photocatalytic systems with optimized efficiency and practical viability.

Understanding the Bottleneck: The Fundamental Principles of Mass Transfer in Photocatalysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are mass transfer limitations in photocatalytic systems? Mass transfer limitations refer to physical barriers that slow down the movement of reactant molecules from the bulk solution to the active catalytic sites on the photocatalyst surface. In slurry reactors, these limitations can manifest as significant concentration gradients in the bulk solution, especially when mixing is insufficient. This becomes particularly critical when the reaction rate at the catalyst surface is faster than the rate at which new reactants can arrive, making mass transfer the rate-controlling step rather than the surface reaction itself [1].

2. How can I identify if my experiment is suffering from mass transfer limitations? You can identify mass transfer limitations through several experimental indicators:

- The reaction rate plateaus or decreases despite further increases in catalyst loading [1].

- The reaction rate becomes unaffected by further increases in radiation energy input at high irradiation intensities [1].

- Gentle magnetic stirring in a regular-sized reactor may be insufficient; the reaction rate shows a dependency on agitation speed or flow rate [1].

3. Why does my reaction rate peak and then fall with increasing catalyst load? This common observation is due to the interplay of several factors. While increasing catalyst load provides more active sites, it also increases the suspension's optical thickness, reducing light penetration and creating darker zones where the catalyst is not activated [1]. Furthermore, high catalyst loadings can promote particle agglomeration, reducing the total available surface area and potentially introducing internal diffusive limitations within the agglomerates. Beyond a certain point, the negative effects of light scattering and agglomeration outweigh the benefit of additional active sites [1].

4. Does improving mixing always solve mass transfer issues? Improved mixing is crucial for mitigating concentration gradients in the bulk solution [1]. However, it may not address other forms of limitation. If the limitation exists at the micro-scale, such as external diffusion through the boundary layer immediately surrounding each catalyst particle or internal diffusion into porous agglomerates, simply increasing bulk flow may not be sufficient. A comprehensive strategy often involves optimizing both bulk mixing and catalyst design (e.g., reducing particle size/agglomeration) to address all potential diffusional barriers [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Reaction Rate is Independent of Light Intensity at High Irradiation Levels

Description At high irradiation intensities, the reaction rate fails to increase with further increases in light intensity, suggesting that the process is no longer limited by photon availability.

Diagnosis and Solution

- Diagnosis: This indicates a shift from kinetic control (reaction-limited) to mass transfer control (diffusion-limited). The photon flux is sufficient to create electron-hole pairs faster than reactants can diffuse to the surface to consume them [1].

- Solution:

- Enhance Mixing: Increase agitation speed or reactor flow rate to reduce the boundary layer thickness around catalyst particles and improve reactant supply [1].

- Optimize Catalyst Loading: Re-evaluate the catalyst concentration. An excessively high load may cause shading and reduce the effective illuminated surface area [1].

- Catalyst Engineering: Consider using catalysts with higher surface area or smaller particle size to reduce the diffusional path length for reactants.

Problem: Optimal Catalyst Loading is Lower than Theoretically Expected

Description The maximum reaction rate is achieved at a catalyst concentration lower than the point where the reactor becomes opaque, indicating inefficiencies.

Diagnosis and Solution

- Diagnosis: This is often a combined effect of mass transfer and radiation transport limitations. Before the reactor is fully opaque, there may already be significant light gradients and concentration profiles, especially in the direction of light propagation [1].

- Solution:

- Improve Reactor Geometry: Use reactors with shorter optical path lengths or designs that ensure more uniform light distribution.

- Verify Mixing Efficiency: Ensure that mixing is vigorous enough to move catalyst particles rapidly between illuminated and dark zones, effectively averaging out the light exposure [1].

- Conduct a Loading Curve: Systematically measure the reaction rate across a wide range of catalyst loads under your specific mixing and irradiation conditions to find the true optimum.

The following parameters significantly influence mass transfer and should be carefully monitored and optimized.

Table 1: Key Parameters Affecting Mass Transfer in Photocatalytic Systems

| Parameter | Effect on Mass Transfer | Optimal Range / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Loading [1] | High loads increase sites but cause light scattering/agglomeration, limiting mass transfer. | System-dependent; an optimum exists where benefit of more sites outweighs transfer limitations. |

| Flow Rate / Agitation Speed [1] | Directly influences bulk mass transfer; higher speed reduces boundary layer thickness. | Should be high enough to ensure no bulk concentration gradients. |

| Light Intensity [1] | High intensity can shift rate-limiting step from kinetics to mass transfer. | Should be balanced with reactant supply; does not always improve rate if mass transfer is limited. |

| Pollutant Concentration [2] | Lower concentrations are typically degraded faster due to more available active sites per molecule. | High concentrations can hinder light penetration and saturate active sites. |

| Temperature [2] | Moderate temperatures can enhance diffusion and reaction kinetics. | Excessively high temperatures may degrade the catalyst or shorten reactive species lifetime. |

| pH [2] | Affects catalyst surface charge and pollutant adsorption, influencing the initial step of mass transfer. | Should be optimized relative to the catalyst's point of zero charge (PZC) and pollutant nature. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Bulk Mass Transfer Limitations

Objective: To determine if the observed reaction rate is limited by the transport of reactants in the bulk solution.

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a well-controlled batch or recirculating photoreactor where the flow rate or agitation speed can be precisely varied [1].

- Experiment:

- Conduct experiments at a fixed catalyst loading and light intensity.

- Measure the degradation rate of a model pollutant (e.g., dichloroacetic acid) over a series of progressively increasing agitation speeds or flow rates [1].

- Analysis:

- Plot the reaction rate against the agitation speed/flow rate.

- If the reaction rate increases with agitation, bulk mass transfer limitations are significant.

- The point where the rate becomes independent of further increases in agitation indicates that bulk mass transfer limitations have been minimized.

Protocol 2: Determining the Optimal Catalyst Loading

Objective: To find the catalyst concentration that provides the highest reaction rate by balancing active sites and mass/light transfer limitations.

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a standardized reactor configuration with fixed mixing and illumination conditions [1].

- Experiment:

- Perform a series of identical photocatalytic degradation runs.

- Systematically vary the catalyst concentration across a wide range, from very low to very high loads [1].

- Analysis:

- Plot the initial reaction rate or apparent rate constant against the catalyst concentration.

- Identify the concentration at which the rate is maximized. A subsequent decrease in rate at higher loads signals the dominance of light scattering and mass transfer issues [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Photocatalytic Mass Transfer Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | The benchmark semiconductor photocatalyst; used as a suspended powder (e.g., Aeroxide P25) to provide active sites for redox reactions [1] [2]. |

| Model Pollutants | Well-characterized compounds like dichloroacetic acid, phenol, or dyes used to quantitatively study degradation kinetics and mass transfer effects without unknown variables [1]. |

| pH Buffers | Used to control the solution pH, which critically affects the surface charge of the catalyst, the adsorption of reactants, and the reaction pathways [2]. |

| Oxidizing Agents | Additives like hydrogen peroxide or persulfate can be used to promote the formation of reactive oxygen species, potentially altering the reaction kinetics and masking mass transfer effects; use with caution [2]. |

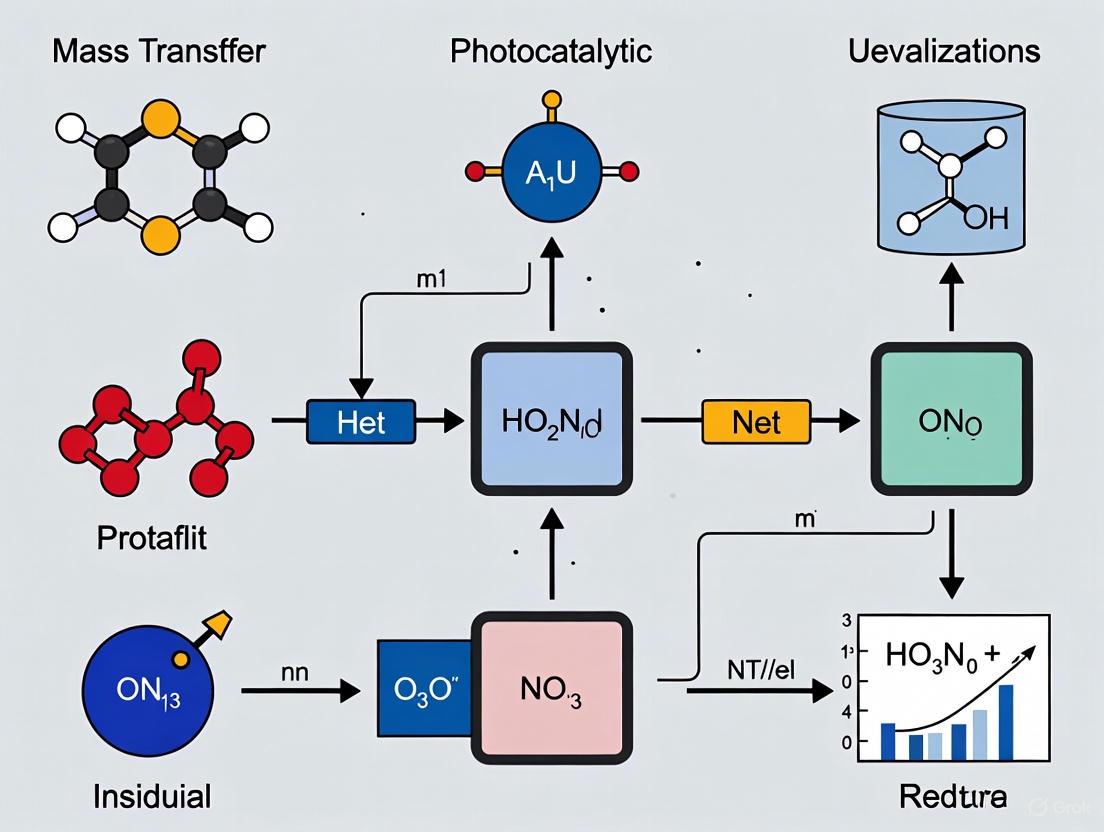

System Relationships and Workflow

Diagram 1: Diagnostic workflow for identifying mass transfer limitations.

Diagram 2: Problem-diagnosis-solution relationships for mass transfer issues.

The Interplay of Mass Transfer with Charge Dynamics and Light Absorption

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary signs that my photocatalytic system is limited by mass transfer rather than charge dynamics?

A system is likely mass-transfer-limited if you observe a strong dependence of the reaction rate on physical mixing parameters (e.g., stirring speed) or fluid dynamics, rather than just the light intensity. In contrast, a charge-dynamics-limited system will show a reaction rate that is highly sensitive to light flux. Experimentally, if improving catalyst crystallinity or designing heterojunctions to enhance charge separation yields diminishing returns, the bottleneck is probably mass transfer. In bubble column reactors, a key indicator is that the gas-liquid interfacial area, rather than the intrinsic activity of the catalyst, controls the overall reaction rate [3].

2. How can I experimentally distinguish between slow charge separation and slow surface reaction kinetics?

Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy is a powerful technique for this. It can track the fate of photogenerated electrons and holes on ultrafast timescales, directly quantifying their separation efficiency and recombination rates [4]. If fs-TA shows long-lived charge separation but the overall photocatalytic efficiency remains low, the limitation likely lies in the sluggish kinetics of the surface reaction (e.g., the Oxygen Evolution Reaction - OER). Replacing the OER with a more thermodynamically favorable oxidation reaction, such as benzyl alcohol oxidation, can serve as a diagnostic test; a significant boost in the reduction half-reaction (e.g., Hâ‚‚ evolution) confirms surface reaction kinetics as the bottleneck [5] [6].

3. What reactor design strategies can mitigate mass transfer limitations in gas-liquid photocatalytic systems like COâ‚‚ reduction?

Optimizing the reactor to maximize the gas-liquid-solid interfacial contact area is crucial. Confined reactor geometries, such as microchannel or Hele-Shaw cells, can enhance mass transfer coefficients by 2 to 7 times compared to traditional large-scale reactors [3]. These designs create thin liquid layers that significantly reduce mass transfer resistance. Furthermore, generating smaller COâ‚‚ bubbles (e.g., by reducing orifice diameter in bubble columns) increases the total interfacial area available for reaction, thereby improving the overall mass transfer rate [3].

4. My photocatalyst has excellent light absorption and charge separation properties, but the overall efficiency is poor. What should I investigate next?

When material properties are optimized, the focus should shift to system-level and reaction environment engineering. First, evaluate mass transfer by analyzing your reactor's hydrodynamics and mixing efficiency. Second, consider manipulating the reaction conditions; for instance, introducing a synergistic photothermal effect by using concentrated sunlight or mild heating can dramatically enhance reaction kinetics and product desorption [5]. Finally, ensure you are not using a "poisoned" system where surfactants or reaction byproducts accumulate on the catalyst surface, blocking active sites and impeding reactant access [3].

5. How does the formation of a heterojunction (e.g., S-scheme) influence both charge dynamics and mass transfer?

Heterojunctions are primarily designed to improve charge dynamics. An S-scheme heterojunction, for example, creates an internal electric field that drives the spatial separation of powerful photogenerated electrons and holes, thereby enhancing their lifetime and redox power [5] [7]. While not directly affecting bulk mass transfer, an efficient heterojunction increases the density of active surface sites. This effectively makes the catalyst surface "hungrier" for reactants, which can, in turn, make mass transfer a more prominent limiting factor if not properly addressed in the reactor design [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Product Yield Despite High Catalyst Activity in Laboratory Tests

Description: A photocatalyst demonstrates excellent performance in small-scale, well-mixed batch reactions (e.g., high apparent quantum yield), but the reaction rate and product yield plummet when scaling to larger volumes or different reactor configurations.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of mass transfer limitations becoming dominant at scale. In small lab batches, vigorous magnetic stirring ensures perfect mixing. In larger systems, fluid dynamics are less efficient, leading to concentration gradients where reactants are depleted near the catalyst surface [3] [6].

Solution Steps:

- Analyze Flow Regime: Characterize the flow dynamics in your reactor. For liquid-phase reactions, aim for turbulent flow to minimize boundary layer thickness. For gas-liquid systems (e.g., COâ‚‚ reduction), ensure high gas hold-up and small bubble size to maximize interfacial area [3].

- Re-optimize Operating Parameters: When scaling up, parameters like stirring speed, gas flow rate, and catalyst loading need to be re-optimized specifically for the new reactor geometry to overcome mass transfer resistances.

- Consider Alternative Reactors: Switch to a reactor design with intrinsically better mass transfer characteristics. Packed bed, monolithic, or microchannel reactors offer high surface-to-volume ratios and can significantly enhance performance in mass-transfer-limited regimes [3].

Problem 2: Inefficient Charge Separation and Utilization

Description: The photocatalyst absorbs light effectively, but the overall efficiency is low due to rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs.

Diagnosis: This is a fundamental challenge in charge dynamics. The generated charges recombine (in the bulk or on the surface) before they can migrate to active sites and participate in the desired redox reactions [4] [8].

Solution Steps:

- Construct a Heterojunction: Engineer a composite photocatalyst by coupling two or more semiconductors with matched band structures. S-scheme or Z-scheme heterojunctions are particularly effective, as they create an internal electric field that promotes the spatial separation of electrons and holes while preserving their high redox potential [5] [7].

- Employ Advanced Characterization: Use techniques like Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy to directly probe the charge transfer paths and lifetimes on ultrafast timescales. This data is critical for rationally designing material improvements [4].

- Optimize the Charge Transfer Pathway: Replace the kinetically sluggish oxygen evolution reaction (OER) with a more favorable oxidation reaction. This reduces the "hole backlog," accelerating electron consumption and thereby suppressing recombination [5] [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Charge Transfer Kinetics using Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy

Objective: To directly observe and quantify the dynamics of photogenerated charge carriers (electrons and holes) in a photocatalyst, including their separation, recombination, and transfer lifetimes [4].

Materials:

- Femtosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire amplifier)

- Spectrophotometer for steady-state absorption

- Photocatalyst sample in powder form or as a thin film

- Optical parametric amplifier (OPA) for tunable pump pulses

- White-light continuum probe pulse generation system

- Fast detector and data acquisition system

Methodology:

- Pump-Probe Setup: Split the femtosecond laser output into two beams. The powerful "pump" beam is tuned to the excitation wavelength of your photocatalyst using an OPA. The weaker "probe" beam is delayed optically and focused into a sapphire crystal to generate a broad white-light continuum.

- Sample Excitation and Probing: The pump beam excites the photocatalyst, generating electron-hole pairs. The delayed white-light probe beam then passes through the excited sample region.

- Spectral Acquisition: Measure the changes in the probe beam's absorption spectrum (ΔA) as a function of time delay between the pump and probe. This ΔA signal contains information on the excited-state populations.

- Data Analysis: Global fitting of the time-resolved ΔA data is used to extract kinetic traces at specific wavelengths. The decay characteristics are modeled to simulate the quenching paths and lifetimes of the charge carriers on femtosecond to picosecond timescales, revealing the efficiency of charge separation and recombination [4].

Protocol 2: Investigating Mass Transfer and Reaction Kinetics in a Confined Bubble Column Reactor

Objective: To study the dynamics and mass transfer behavior of single COâ‚‚ bubbles in a liquid absorbent (e.g., Monoethanolamine - MEA) under confinement, simulating conditions in intensified reactors [3].

Materials:

- Hele-Shaw cell (quartz glass) with adjustable gap widths (e.g., 1, 2, 3 mm)

- High-speed camera and image acquisition system

- LED backlight source

- Syringe pumps and gas-tight syringes

- Metal capillary tubes for bubble generation

- COâ‚‚ and Nâ‚‚ gas cylinders

- Aqueous MEA solution

Methodology:

- System Setup: Fill the Hele-Shaw cell with the MEA solution. Use a syringe pump to inject COâ‚‚ through a metal capillary tube to generate single bubbles of a controlled size at the bottom of the cell.

- Image Capture: Record the ascent and shape evolution of the COâ‚‚ bubble using the high-speed camera. Ensure sufficient frame rate and resolution to track bubble motion and deformation.

- Data Extraction (Image Processing):

- Bubble Velocity: Track the centroid of the bubble frame-by-frame to calculate its instantaneous and terminal velocity.

- Bubble Size and Shape: Measure the equivalent diameter and aspect ratio of the bubble to quantify its dynamics.

- Shrinking Rate: As COâ‚‚ is absorbed and reacts with MEA, the bubble volume will decrease. Measure the rate of size reduction over time.

- Mass Transfer Calculation: The liquid film mass transfer coefficient ((k_L)) can be determined from the rate of change of the bubble's volume (dV/dt) using the equation derived from the two-film theory, where the mass transfer rate is related to the concentration gradient and the interfacial area [3].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Material Properties and Their Impact on Photocatalytic Efficiency

| Material Property | Impact on Charge Dynamics | Impact on Mass Transfer | Characterization Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Gap & Structure | Determines light absorption range and redox potential of charge carriers [8]. | Indirectly affects mass transfer by influencing reaction rate and local concentration gradients. | UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) |

| Heterojunction Interface Quality | Critical for efficient spatial separation of electrons and holes; poor contact leads to high recombination [8] [7]. | Not a direct factor. | Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) [4], in situ XPS [7] |

| Surface Area & Porosity | Provides more active sites for reactions, improving the utilization of separated charges. | Directly increases the interfacial area for reactant adsorption and product desorption, enhancing mass transfer [3]. | BET Surface Area Analysis |

| Bubble Size & Distribution (in gas-liquid systems) | No direct impact. | Primary factor controlling gas-liquid interfacial area, which dictates mass transfer rate [3]. | High-speed camera imaging [3] |

Table 2: Comparison of Reactor Types and Their Characteristics

| Reactor Type | Typical Application | Advantages for Charge Dynamics | Advantages for Mass Transfer | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Slurry Reactor | Lab-scale pollutant degradation, water splitting | Good light penetration in dilute suspensions; simple setup for catalyst screening. | Vigorous stirring can minimize gradients; good for solid-liquid reactions. | Poor light penetration at high catalyst loadings; potential for catalyst attrition; scale-up challenges [6] |

| Bubble Column Reactor | Photocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction | Can be designed for uniform illumination. | High gas hold-up provides large interfacial area; simple geometry; low operating cost [3]. | Back-mixing and possible bubble coalescence can reduce efficiency. |

| Microchannel / Confined Reactor | Process-intensified systems, fundamental studies of single bubbles/ droplets | Short diffusion paths for charges to reach the surface. | Mass transfer coefficients 2-7x higher than traditional reactors due to thin fluid layers and confined bubble dynamics [3]. | Prone to clogging; challenging catalyst integration; small throughput. |

System Workflows and Logical Pathways

Diagnostic Pathway for Efficiency Limitations

Charge and Mass Transfer Balance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Their Functions in Photocatalytic Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Monoethanolamine (MEA) | A common amine-based absorber used in studies of COâ‚‚ capture and photocatalytic reduction to model chemical absorption and reaction [3]. | The reaction between COâ‚‚ and MEA can create amphipathic ions that contaminate the gas-liquid interface, reducing the mass transfer rate. This must be accounted for in kinetic models [3]. |

| S-scheme Heterojunction Components | A pair of semiconductors (e.g., TiO₂/Ce₂S₃, ZnFe₂O₄/MoS₂) fabricated to create an internal electric field for superior charge separation [7]. | The interfacial contact quality and relative band alignment are critical. Characterization via in situ XPS and Kelvin probe force microscopy is essential to confirm the S-scheme mechanism [7]. |

| Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Setup | The ultimate tool for directly probing the ultrafast dynamics of photogenerated charge carriers, from separation to recombination [4]. | Requires specialized laser equipment and expertise. Data analysis involves global fitting of kinetic traces to extract lifetime components and elucidate charge transfer paths [4]. |

| Hele-Shaw Cell | A reactor with a very narrow, adjustable gap used for fundamental studies of bubble/droplet dynamics and mass transfer under confinement [3]. | Enables visualization and quantification of single-bubble mass transfer. The confined geometry can enhance mass transfer coefficients by a factor of 2-7 compared to conventional reactors [3]. |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Electron donors (e.g., triethanolamine, methanol) or acceptors used to selectively consume one type of charge carrier, simplifying the study of the other half-reaction. | While useful for mechanistic studies, their use is not "green" and can cause environmental pollution. A more sustainable strategy is to couple the reaction with a value-added oxidation process [6]. |

| PHENAFLEUR | PHENAFLEUR, CAS:80858-47-5, MF:C14H20O, MW:204.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Propinetidine | Propinetidine|3811-53-8|Research Chemical | Propinetidine (CAS 3811-53-8) is a chemical reagent for research use. This product is for laboratory research only and not for human or veterinary use. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary mass transfer limitations in a slurry photocatalytic reactor? In slurry reactors, mass transfer limitations occur at multiple levels. External bulk mass transfer involves the movement of pollutant molecules from the liquid bulk to the external surface of the photocatalytic particle or agglomerate. Internal mass transfer pertains to the diffusion of these molecules into the porous structure of the catalyst agglomerate itself. Furthermore, light penetration impediments within the catalyst particle or agglomerate represent a critical, often irreducible limitation, as the reaction can only occur where photons reach. Even for small particles or agglomerates below 1 µm, internal light penetration can be a significant restriction [9].

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally determine if my system is limited by mass transfer? A change in the observed reaction rate while varying mixing intensity (e.g., stirrer speed) or gas flow rate indicates the presence of external mass transfer limitations. If the rate increases with higher agitation, your system is likely under mass transfer control. For internal limitations, if the reaction rate does not scale proportionally with the increase in catalyst surface area (e.g., using finer particles), or if the effectiveness factor (the ratio of the actual reaction rate to the rate without diffusion limitations) is calculated to be much less than 1, internal mass transfer is likely a restricting factor [9].

FAQ 3: Does catalyst loading and particle size affect mass transfer? Yes, both are critical parameters. Higher catalyst loadings can lead to increased particle agglomeration and light scattering, which exacerbates internal mass and light transfer limitations by creating larger, effectively shielded entities. Larger primary particles or agglomerates directly intensify internal mass transfer limitations by creating longer diffusion pathways for reactants to reach active sites and by reducing the penetration of light into the particle's core [9].

FAQ 4: What operational parameters can I optimize to overcome mass transfer limitations? Optimizing parameters such as catalyst loading, agitation speed, and reactor geometry can mitigate these limitations. Advanced optimization techniques like Bayesian Optimization (BO) have proven effective for this purpose. BO can efficiently handle complex, multi-variable systems to find the optimal conditions that maximize reaction rates, often outperforming traditional design of experiment (DOE) methods. For instance, BO has been successfully used to optimize partial pressures of reactants and reaction time in photocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction [10].

FAQ 5: Are there catalyst engineering strategies to minimize these limitations? Absolutely. Key strategies include:

- Immobilization: Fixing catalysts on substrates (e.g., graphene oxide on electrodes) can prevent agglomeration, facilitate catalyst separation, and potentially create more defined structures that improve mass transfer [11].

- Morphology Control: Designing catalysts with high surface area, tailored pore channels (pore-channel engineering), and controlled morphology (morphology and structure tailoring) can drastically shorten diffusion paths and increase the accessibility of active sites [12] [13].

- Point Defects and Doping: Introducing point defects or doping with foreign elements can create additional energy levels and improve charge separation, which indirectly relates to more efficient use of reactants that do manage to transfer [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: Low Photocatalytic Efficiency Despite High Catalyst Loading

- Potential Cause: At high catalyst loadings, particle agglomeration increases, leading to reduced light penetration into the reactor and within the agglomerates. This creates significant internal mass and light transfer limitations [9].

- Solution:

- Optimize Catalyst Loading: Perform experiments to find the optimal catalyst dose beyond which efficiency plateaus or decreases [13].

- Enhance Mixing: Improve agitation to break up agglomerates and renew the reactant concentration at catalyst surfaces.

- Use Immobilized Catalysts: Consider immobilizing the catalyst on a support to maintain high surface area while preventing agglomeration and simplifying separation [11].

Problem 2: Poor Performance Scaling from Bench to Pilot Scale

- Potential Cause: Differences in fluid dynamics and mixing efficiency between scales can exacerbate bulk mass transfer limitations. The light distribution in a larger reactor may also be less uniform [9].

- Solution:

- Advanced Modeling: Employ rigorous radiation and mass transfer models derived from fundamental principles to design the scaled-up reactor [9].

- Reactor Redesign: Explore reactor geometries that promote better mixing and more uniform light distribution, such as annular or microchannel reactors.

- Process Optimization: Use data-driven optimization methods like Bayesian Optimization to rapidly re-optimize operational parameters (e.g., flow rate, light intensity) for the new reactor configuration [10].

Problem 3: Rapid Decrease in Reaction Rate Over Time

- Potential Cause: Catalyst surface fouling or poisoning, where reaction intermediates or impurities in the wastewater (e.g., inorganic ions) adsorb strongly to active sites, blocking reactant access and causing deactivation [13].

- Solution:

- Pre-Treatment: Pre-treat wastewater to remove known catalyst poisons or scavenging ions.

- Surface Modification: Modify catalyst surface chemistry to be more resistant to fouling [12].

- Integrated Processes: Couple photocatalysis with other advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) to more completely mineralize pollutants and clean the catalyst surface in situ [12] [13].

- Regeneration: Implement periodic catalyst regeneration cycles (e.g., washing, calcination).

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Optimizing Mass Transfer and Efficiency

This protocol is adapted from a study on the photocatalytic decolorization of a binary dye solution using an immobilized TiOâ‚‚-GO-GE catalyst [11].

1. Objective: To model and optimize the operational parameters of a photocatalytic process to achieve maximum degradation efficiency by understanding the interaction between factors influencing mass transfer and reaction kinetics.

2. Key Parameters/Variables:

- Factors: pH, Initial Dye Concentration, Catalyst Dosage (amount immobilized).

- Response: Dye Removal Efficiency (%).

3. Methodology:

- Catalyst Immobilization: Graphene oxide (GO) is fabricated on a graphite electrode (GE) via an electrochemical approach. TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles are then immobilized on the GO-GE surface by solvent evaporation [11].

- Experimental Setup: Reactions are carried out in a cylindrical glass batch reactor with immobilized catalytic plates. A UV lamp is placed at the center, and aeration is provided at the bottom.

- Experimental Design: A Central Composite Design (CCD) under RSM is used to create a set of experimental runs that systematically vary the factors.

- Analysis: Dye concentration is monitored spectrophotometrically. The data is fitted to a second-order polynomial model, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is used to validate the model's significance.

4. Quantitative Results from RSM Optimization:

The table below summarizes the optimized conditions and results for the decolorization of Methylene Blue (MB) and Acid Red 14 (AR14) in a binary system [11].

Table 1: Optimized Parameters and Efficiency for Binary Dye Photocatalytic Decolorization

| Parameter | Methylene Blue (MB) | Acid Red 14 (AR14) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal pH | 11 | Not explicitly stated | pH affects catalyst surface charge and pollutant adsorption [13]. |

| Optimal Initial Dye Concentration | 10 mg/L | 10 mg/L | Lower concentrations typically yield faster degradation [13]. |

| Optimal Catalyst Dosage | 0.04 g immobilized TiOâ‚‚ | 0.04 g immobilized TiOâ‚‚ | Corresponds to the amount immobilized on the GO-GE plates. |

| Maximum Removal Efficiency | 93.43% | Reported, but specific value not extracted | Achieved under optimal conditions after 120 minutes. |

| Model Performance (R²) | 0.97 | 0.96 | Indicates an excellent fit of the model to the experimental data. |

Visual Guide: Identifying and Overcoming Mass Transfer Limitations

The following diagram illustrates the different types of mass transfer limitations in a slurry photocatalytic reactor and the primary strategies to overcome them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Their Functions in Photocatalytic Experiments

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚ P25) | Benchmark semiconductor photocatalyst [11]. | High activity, mixed anatase/rutile phase. Requires UV light for activation due to wide bandgap [13]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Catalyst support and co-catalyst [11]. | Enhances electron-hole separation; provides a high-surface-area substrate for immobilization; improves stability of electrodes [11]. |

| Graphite Electrode (GE) | Substrate for catalyst immobilization [11]. | Provides a conductive, stable base for creating immobilized catalytic systems. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant in electrode modification [11]. | Helps disperse GO sheets and makes them positively charged for effective electrophoretic deposition. |

| Methanol/Ethanol | Hole scavenger in sacrificial photocatalysis [14]. | Consumes photogenerated holes, thereby suppressing electron-hole recombination and enhancing reduction reactions. |

| Deionized/Ultrapure Water | Solvent for photocatalytic reactions; required for rigorous testing [14]. | Essential to avoid false positives from nitrogenous contaminants in tap water, especially in Nâ‚‚ reduction studies [14]. |

| Isolysergic acid | Isolysergic Acid|CAS 478-95-5|High Purity | Isolysergic acid is a natural ergoline alkaloid for neuropharmacology research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Triethyl isocitrate | Triethyl isocitrate, CAS:16496-37-0, MF:C12H20O7, MW:276.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In photocatalytic systems, mass transfer governs the delivery of reactants to active catalytic sites and the removal of products, directly determining overall process efficiency. When photocatalytic reaction rates outpace mass transport, systems become diffusion-limited, leading to reduced conversion rates and wasted energy despite sophisticated catalyst design [1] [15]. Understanding and optimizing the interplay between diffusion, convection, and adsorption is therefore essential for advancing photocatalytic research, particularly in applications ranging from environmental remediation to clean energy production [16] [17].

This guide provides troubleshooting methodologies for identifying and overcoming mass transfer limitations, enabling researchers to distinguish between kinetic and transport-controlled regimes and implement effective optimization strategies.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Mass Transfer Limitations

Q1: How can I determine if my photocatalytic system is limited by mass transfer rather than intrinsic reaction kinetics?

A: Several experimental indicators suggest mass transfer limitations:

- Reduced Effectiveness at Scale: The reaction rate or conversion efficiency decreases significantly when scaling from small, well-mixed batch systems to larger or flow reactors, despite maintaining similar catalyst loading and light intensity per unit volume [18].

- Flow Rate Dependence: In flow reactors, the observed reaction rate shows strong dependence on fluid flow rate. If increasing flow rate improves conversion, external mass transfer to the catalyst surface is likely limiting [1] [18].

- Agitation Sensitivity: In slurry reactors, the reaction rate increases with higher mixing or agitation speeds. Under perfect mixing, the rate should become independent of agitation [1].

- High Catalyst Loading, Low Return: Increasing catalyst concentration beyond an optimal point yields diminishing returns or even decreases the overall rate. This can indicate issues with light penetration and the creation of concentration gradients in the bulk fluid [1].

Q2: What strategies can improve diffusive transport of reactants to photocatalyst surfaces?

A: Enhancing diffusion is key when forced convection is limited:

- Reduce Diffusion Paths: Utilize smaller catalyst particles or thinner immobilized catalyst films to decrease the distance reactants must diffuse [1].

- Leverage Photogenerated Electric Fields: Recent research shows that illuminated photocatalysts like BiVOâ‚„ and TiOâ‚‚ can generate long-range electric fields, boosting the diffusive transport of ionic reactants by over three orders of magnitude without additional energy input [15].

- Optimize Catalyst Dispersion: In slurry systems, ensure catalyst particles are well-dispersed and not heavily agglomerated, as agglomeration creates longer internal diffusion paths for reactants [1].

Q3: How does reactor hydrodynamics (convection) influence photocatalytic efficiency, and how can it be optimized?

A: Convection governs bulk transport and is critical for efficient operation:

- Eliminate Dead Zones: Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to simulate flow patterns and identify stagnant regions ("dead zones") with poor reactant-catalyst contact. One study showed that optimizing mixing speeds to mitigate these zones achieved 99% pollutant removal [18].

- Enhance Turbulence: Design reactor internals or select impellers that promote turbulent flow, which improves convective transport to catalyst surfaces. The k-omega turbulence model can help simulate and optimize these conditions [18].

- Match Reactor Design to Process: For slow reactions, simple mixed tanks may suffice. For fast reactions, consider plug flow or packed-bed reactors that offer superior mass transfer characteristics.

Q4: What is the relationship between catalyst adsorption properties and overall mass transfer?

A: Adsorption is the crucial bridge between bulk transport and surface reaction:

- Capacity vs. Rate: Diffusive transport can create a complex interplay with adsorption. Studies show that improved diffusion can increase overall adsorption capacity by continuously supplying reactant, but may conversely lower the observed adsorption rate constant due to the dynamics of the concentration gradient [15].

- Surface Modification: Functionalize catalyst surfaces to improve affinity for target pollutants, thereby increasing local concentration and reaction rate. However, ensure that the adsorption step is not so strong that it hinders the desorption of products [19].

Quantitative Parameters and Optimization Guidelines

The following table summarizes key parameters that control mass transfer in photocatalytic systems and provides practical guidelines for their optimization.

Table 1: Key Mass Transfer Parameters and Optimization Strategies

| Parameter | Governing Law/Principle | Experimental Control Knobs | Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient | Fick's Law [15] | Temperature, solvent viscosity, reactant molecular size, photogenerated electric fields [15] | Maximize coefficient by using smaller reactants, higher temperature, or leveraging field effects. |

| Convective Mass Transfer | Film Theory / Reynolds Number [18] | Flow velocity, mixing speed, reactor geometry, turbulence [1] [18] | Minimize boundary layer thickness; ensure turbulent flow where beneficial. |

| Adsorption Kinetics | Langmuir / Second-order models [15] | Catalyst surface chemistry, pH, initial reactant concentration [15] | Balance high adsorption capacity with fast surface reaction and product desorption. |

| Catalyst Loading & Distribution | Radiation Transfer & Scattering [1] | Solid concentration in slurries, coating thickness/thin films [1] | Find optimum between high surface area and poor light penetration/agglomeration. |

| Reactant Concentration | Reaction-Diffusion Balance [1] [15] | Feed concentration, reactor configuration (batch/flow) | Avoid conditions where rapid surface reaction depletes local concentration to near zero. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing Mass Transfer Limitations

Protocol 1: Distinguishing Kinetic and Mass Transfer Regimes

This protocol helps determine whether your system is limited by the intrinsic chemical reaction or by physical transport processes.

Objective: To identify the rate-limiting step in a heterogeneous photocatalytic reaction. Materials: Photocatalytic reactor, light source, pump/agitator, analytical equipment (e.g., UV-Vis, GC). Method:

- Kinetic Regime Test: Conduct experiments at a very high stirring speed or flow rate while keeping catalyst loading and light intensity constant. If the reaction rate increases with increasing agitation, the system is not yet in a pure kinetic regime.

- Mass Transfer Regime Test:

- Vary Agitation/Flow: Measure the reaction rate at different agitation speeds or flow rates. A strong correlation indicates external mass transfer limitations.

- Vary Catalyst Loading: Measure the rate at different catalyst loadings. A linear increase suggests a kinetic regime, while a plateau or decrease suggests limitations from light penetration or internal diffusion [1].

- Analysis: The regime where the reaction rate becomes independent of fluid dynamics is the kinetic regime. All subsequent intrinsic kinetic studies should be performed under these conditions [1].

Protocol 2: CFD-Assisted Reactor Optimization

This protocol uses simulation to visualize and improve mass transfer before costly experimental builds.

Objective: To model flow patterns and radiation distribution to identify and mitigate dead zones. Materials: CFD software (e.g., SimScale, COMSOL), reactor geometry specifications, optical properties of the reaction mixture. Method:

- Model Setup:

- Hydrodynamics: Use a Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) model with a k-omega turbulence closure to simulate the velocity field [18].

- Radiation: Use a Monte Carlo model or Discrete Ordinate Method (DOM) to solve the Radiation Transfer Equation (RTE) and calculate the Local Volumetric Rate of Energy Absorption (LVREA) [18].

- Simulation: Solve the coupled momentum and mass transport equations to visualize flow velocity contours and radiation distribution within the reactor [18].

- Identification: Locate regions of low velocity (dead zones) and poor irradiation.

- Optimization: Iteratively modify the reactor design (e.g., baffle placement, inlet/outlet location, light source arrangement) or operating conditions (e.g., mixing speed) to achieve a more uniform flow and radiation field [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mass Transfer Studies

| Item | Function in Mass Transfer Studies | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) P25 | Benchmark photocatalyst; used to study the effects of particle size and agglomeration on internal diffusion and light scattering [1] [20]. | Model pollutant degradation (e.g., dichloroacetic acid) to probe bulk concentration gradients [1]. |

| Bismuth Vanadate (BiVOâ‚„) Films | Model photocatalyst for investigating photogenerated electric fields and their long-range effect on ionic reactant transport [15]. | Studying enhanced diffusion of dichromate ions during photocatalytic reduction [15]. |

| Cobalt-Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (CoFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„) | Magnetic photocatalyst that can be incorporated into membranes; used to study mass transfer in immobilized systems without filtration [18]. | Investigating the role of flow dynamics and irradiation on degradation efficiency in a membrane reactor [18]. |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Model ionic reactant and adsorbate; its diffusion and adsorption can be tracked spectroscopically [15]. | Quantifying adsorption kinetics and capacity under controlled diffusive transport [15]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | To simulate and visualize fluid flow, concentration gradients, and radiation distribution, identifying dead zones and mass transfer limitations in silico [18]. | Pre-optimization of reactor design and operating parameters before experimental implementation [18]. |

| 3-Methoxybut-1-yne | 3-Methoxybut-1-yne, CAS:18857-02-8, MF:C5H8O, MW:84.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tris(p-tolyl)stibine | Tris(p-tolyl)stibine, CAS:5395-43-7, MF:C21H21Sb, MW:395.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Conceptual Diagrams of Mass Transfer Pathways and Diagnostics

Mass Transfer Pathways in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis

Experimental Diagnostic Workflow

Engineering Solutions: Advanced Strategies to Enhance Mass Transfer and Reactant Accessibility

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers working on the morphological control of hierarchical and porous nanostructures for photocatalytic applications. The content is framed within the broader thesis context of overcoming mass transfer limitations in photocatalytic systems, a critical factor determining overall reactor efficiency [1] [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my photocatalytic reaction rate plateau or even decrease after I increase the catalyst concentration beyond a certain point?

This common issue often stems from interrelated mass transport and radiation propagation limitations [1]. While increasing catalyst concentration provides more active sites, it also:

- Increases optical density: Beyond a certain concentration, the reactor becomes opaque, creating a "dark zone" where catalyst particles receive no light, rendering them inactive [1].

- Exacerbates mass transfer limitations: At high catalyst loadings, severe concentration gradients of reactants and products can develop in the bulk solution, especially if mixing is insufficient [1].

- Promotes particle agglomeration: Higher concentrations can lead to particle aggregation, creating porous agglomerates where internal diffusion limits the reaction rate and masks active sites [1].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Action: Determine the optimal catalyst concentration.

- Protocol: Conduct a series of experiments where you measure reaction rate as a function of catalyst loading under constant light intensity and mixing conditions. The optimal loading is just before the rate plateaus.

- Action: Improve mixing efficiency.

- Protocol: Enhance fluid dynamics in your reactor. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations can help optimize flow rates and patterns. According to a model, the external mass transfer coefficient (k_external) increases with the Reynolds number (Re): k_external ∠Re^0.77 [21]. This means higher flow rates (which increase Re) can significantly improve mass transfer.

- Action: Verify intrinsic kinetics.

- Protocol: Ensure you are operating in a regime free from mass transfer limitations for accurate kinetic studies. This often requires very good mixing, especially in the direction of radiation propagation [1].

Q2: How can I tell if my photocatalytic system is suffering from mass transfer limitations, and how do I distinguish them from charge recombination issues?

Diagnosing the root cause of low efficiency is essential. The following table contrasts the characteristics of these two limitations.

Table 1: Differentiating Mass Transfer Limitations from Charge Recombination Issues

| Aspect | Mass Transfer Limitations | Charge Recombination Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Effect | Limits reactant access to active sites and product removal [21]. | Reduces the number of available charge carriers for surface reactions [22] [23]. |

| Response to Stirring/Speed | Reaction rate improves significantly with increased stirring speed or flow rate [21]. | Reaction rate is largely unaffected by changes in fluid dynamics. |

| Response to Light | At high light intensities, the rate becomes independent of light intensity as mass transfer becomes the rate-limiting step [1]. | Efficiency often decreases at high light intensities due to accelerated recombination. |

| Catalyst Loading | Rate peaks and then decreases with increasing catalyst loading [1]. | Rate typically increases and then plateaus with catalyst loading. |

| Characterization | Modeled using CFD; related to Reynolds number [21]. | Characterized by photoluminescence spectroscopy and photocurrent measurements [24] [23]. |

Q3: I synthesized a new hierarchical photocatalyst, but standard activity tests (like NOx removal) show no performance. Is my material inactive?

Not necessarily. Standard tests can sometimes be insensitive to certain materials [25].

- True Potential Revelation: Some materials, like certain photocatalytic paints, require a degree of "weathering" or initial use to reveal their true potential, as organic binders may initially block active sites [25].

- Test Sensitivity: Your material might have low activity that is not detectable by a particular ISO test but could be active in other reactions. For example, many films show no activity in NOx tests but are highly active in dye degradation tests like methylene blue [25].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Action: Employ alternative screening methods.

- Protocol: Use highly sensitive, rapid-screening methods like photocatalyst indicator inks (e.g., based on methylene blue or resazurin reduction) to detect low levels of activity [25].

- Action: Test under different conditions.

- Protocol: Evaluate your material using other probe reactions, such as the degradation of stearic acid (for self-cleaning) or 4-chlorophenol (for powders) [25].

- Action: Perform accelerated weathering or pre-treatment.

- Protocol: Subject your sample to simulated use conditions (e.g., UV exposure in a humid environment, repeated washing for fabrics) to remove surface contaminants or binders before testing [25].

Q4: What are the key advantages of hierarchical morphologies over simple nanoparticles for overcoming mass transfer limitations?

Hierarchical structures, such as microspheres composed of 2D nanosheets or 3D networks, offer a multifaceted solution to the challenges faced by simple nanoparticles.

- Enhanced Mass Transfer: The interconnected porous network facilitates the diffusion of reactant molecules to active sites and the removal of product molecules, preventing pore blockage and maintaining high activity [24] [26] [21].

- High Surface Area and Active Sites: They provide a large specific surface area for reactions while being more easily separable from the reaction slurry than primary nanoparticles [24] [27].

- Improved Light Harvesting: The complex porous structure can enhance light scattering and trapping within the material, increasing the probability of photon absorption [24].

The diagram below illustrates how a hierarchical structure integrates multiple beneficial features to enhance photocatalytic efficiency by simultaneously addressing mass transfer and charge separation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

This table lists essential reagents and materials used in the synthesis and characterization of hierarchical nanostructures, as referenced in the provided research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Morphological Control

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Acetate & Urea | Precursors for the hydrothermal synthesis of hierarchical ZnO microsphere precursors [24]. | Used to create ZnO microspheres from 2D nanosheets forming a 3D network, with optimal performance after annealing at 400°C [24]. |

| Benzaldehyde Derivatives | Organic linkers for covalent modification of g-C₃N₄ frameworks to create covalent organic frameworks (COFs) [23]. | Used to synthesize CN-306 COF, where electron-withdrawing groups enhanced electron-hole separation and boosted H₂O₂ production [23]. |

| Bismuth & Iodine Sources | Precursors for solvothermal synthesis of bismuth-based photocatalysts (e.g., Bi₅O₇I) [27]. | Used to prepare Bi₅O₇I with nanoball, nanosheet, and nanotube morphologies; nanoballs showed highest degradation efficiency for Rhodamine B [27]. |

| Sacrificial Templates (e.g., Silica spheres, micelles) | Used to create well-defined pores within a material; template is removed after structure formation [26]. | Employed in creating nanoporous gold (np-Au) and other porous architectures to achieve high surface area and tunable pore sizes [26]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) / Rhodamine B (RhB) | Model organic dye pollutants used for standardized assessment of photocatalytic degradation efficiency [24] [25] [27]. | Used to test the activity of hierarchical ZnO microspheres [24] and Bi₅O₇I morphologies [27]. Also a component in indicator inks for rapid activity screening [25]. |

| Agavoside A | Agavoside A | Agavoside A is a natural saponin from Agave species for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary use. |

| Antho-RWamide I | Antho-RWamide I, CAS:114056-25-6, MF:C31H46N10O7, MW:670.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Surface Engineering and Defect Creation to Improve Reactant Adsorption

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: Why does my photocatalyst's performance degrade over repeated reaction cycles, and how can surface engineering help? Photocatalyst deactivation is a common challenge, often caused by the strong adsorption of reaction intermediates or products on active sites, poisoning the surface. Surface engineering can mitigate this by creating a more favorable surface environment. For instance, engineering oxygen defects on BiOCl nanosheets not only enhances the initial adsorption of reactants like Rhodamine B (RhB) and Cr(VI) but also facilitates the subsequent photocatalytic degradation, thereby self-cleaning the surface and regenerating the adsorption sites for sustained activity [28]. Furthermore, selecting chemically stable coatings is crucial. Research on anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) templates showed that a stable photocatalyst like TiO₂ maintained performance over multiple cycles, whereas an inherently unstable one like Fe₂O₃ exhibited performance loss [29].

Q2: How can I precisely control the concentration of defects introduced during synthesis? Defect concentration is highly sensitive to synthesis parameters. A proven method is to control the molar ratios of precursors or the concentration of etching agents.

- In Zinc Sulphide (ZnS) synthesis, varying the S/Zn molar ratio during the hydrothermal process directly tunes the concentration of Zn and S vacancies. Samples with the lowest (ZnS0.67) and highest (ZnS3) ratios showed superior photocatalytic activity due to their specific defect profiles [30].

- For BiOCl, the concentration of oxygen defects can be modulated by the volume of acetic acid (CH₃COOH) used during preparation. The H⺠ions from the acid facilitate the detachment of oxygen atoms from the lattice, and the amount of acid directly influences the extent of defect formation [28].

Q3: My composite photocatalyst has high surface area but low reaction rates. Could mass transfer be the issue? Yes. Even with a high surface area, inefficient transport of reactants to the active sites can limit the overall reaction rate. This is a classic mass transfer limitation. Strategies to overcome this include:

- Enhancing Adsorption Capacity: Designing catalysts where the support material also acts as an adsorbent creates a "reaction microenvironment." For example, a TiOâ‚‚/MWCNT (multiwalled carbon nanotube) composite achieved 95% tetracycline removal. The MWCNTs adsorb pollutants, concentrating them near the TiOâ‚‚ photocatalytic sites, thus overcoming bulk diffusion limitations [31].

- Optimizing Fluid Dynamics: In slurry reactors, insufficient mixing can lead to concentration gradients in the bulk liquid, especially in the direction of light propagation. Ensuring very good mixing conditions is critical to minimize these gradients and ensure reactants can access the irradiated catalyst surface [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Photocatalytic Performance Across Different Batches of Synthesized Catalyst

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled defect concentration | Perform XPS analysis to quantify surface elemental ratios and identify defect types. Use PL spectroscopy; higher intensity often indicates more recombination centers from excessive defects. | Standardize precursor molar ratios and reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, time). For acid-treated defects, precisely control acid concentration and treatment duration [28] [30]. |

| Poor charge separation efficiency | Conduct electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to measure charge transfer resistance. Perform transient photocurrent response measurements. | Employ surface functionalization to promote electron-hole separation. For example, modifying g-C₃N4-based COFs with strong electron-withdrawing groups can enhance charge carrier separation and extend the electron-hole distance [23]. |

| Inadequate adsorption-photocatalysis synergy | Perform adsorption kinetic studies in the dark. If adsorption equilibrium capacity is low or slow, the concentration step for photocatalysis is inefficient. | Engineer surfaces to enhance adsorption. Use supports like MWCNTs to boost adsorption capacity, creating a "concentrator" that feeds reactants to photocatalytic sites [31]. |

Problem: Catalyst Shows High Initial Activity but Rapid Deactivation

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorbed intermediates poisoning active sites | Use in-situ DRIFTS or post-reaction XPS to identify carbonaceous species on the used catalyst surface. | Introduce surface groups that weaken the binding of stable intermediates. Create defects that facilitate the complete mineralization of adsorbates rather than allowing them to remain as poisons [28] [32]. |

| Photocorrosion or surface instability | Perform ICP-MS on the post-reaction solution to detect leached metal ions. Compare XRD patterns of fresh and used catalysts to detect phase changes. | Apply a stable protective overlayer via ALD. Use a chemically stable template or support structure that does not degrade under reaction conditions [29]. |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ decomposition | Monitor Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ concentration over time in the presence of the catalyst under illumination. | Implement surface engineering strategies that suppress the decomposition pathway, such as modifying surface electronic structure to disfavor one-electron redox reactions that break down Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ [33]. |

Quantitative Data on Engineered Photocatalysts

Table 1: Performance of Photocatalysts with Engineered Surface Defects

| Photocatalyst | Synthesis Method | Defect Type | Target Pollutant | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiOCl nanosheets | Room-temperature synthesis with CH₃COOH treatment | Oxygen defects | Rhodamine B (RhB) & Cr(VI) | Enhanced adsorption capacity & photocatalytic degradation; optimal defect concentration crucial. | [28] |

| ZnS nanoparticles | Hydrothermal method with varying [S]/[Zn] ratios | Zn and S vacancies | Methylene Blue (MB) | ZnS0.67 and ZnS3 showed superior visible-light activity; band gap reduced from 3.49 eV to 3.28 eV. | [30] |

| CN-306 COF | Condensation of g-C₃N4-based frameworks | Molecular-level electron cloud redistribution | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Production | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production rate: 5352 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹; Surface quantum efficiency: 7.27% at λ = 420 nm. | [23] |

Table 2: Performance of Composite Photocatalysts for Adsorption-Photocatalysis Synergy

| Photocatalyst | Support/Synergy Strategy | Target Pollutant | Removal Efficiency | Kinetics Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚/MWCNT | Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Tetracycline (TC) | 95% | Pseudo-second-order kinetics, Langmuir isotherm | [31] |

| Pure TiOâ‚‚ (P25) | None (Baseline) | Tetracycline (TC) | 86% | Not specified | [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating Oxygen Defects in BiOCl Nanosheets via Acetic Acid Treatment

This protocol outlines a mild method to synthesize BiOCl nanosheets with tunable oxygen defect concentrations [28].

1. Reagents:

- Sodium Bismuthate (NaBiO₃)

- Cetyltrimethylammonium Chloride (CTAC)

- Acetic Acid (CH₃COOH)

- Deionized Water

2. Procedure:

- Add 1 mmol of NaBiO₃ and 7 mmol of CTAC into 20 mL of deionized water.

- Sonicate and stir the mixture for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Add a controlled volume of CH₃COOH (e.g., 1 mL, 3 mL, 5 mL) to the solution while stirring. The volume of acid is critical for controlling defect concentration.

- Stir the resulting solution for 30 minutes in a sealed container.

- Allow the solution to react statically for 24 hours.

- Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation, wash it thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol, and dry it in an oven.

3. Characterization for Defect Verification:

- XRD: Confirm the tetragonal phase of BiOCl (JCPDS No. 06–0249).

- XPS: Analyze the O 1s spectrum. A shoulder peak at a higher binding energy than lattice oxygen confirms the presence of oxygen vacancies.

- EPR: A strong signal at g ≈ 2.001 is characteristic of oxygen vacancies.

Protocol 2: Hydrothermal Synthesis of ZnS with Tunable Zn and S Vacancies

This protocol describes the synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles with vacancy defects controlled by precursor stoichiometry [30].

1. Reagents:

- Zinc Chloride (ZnClâ‚‚)

- Thiourea (SC(NHâ‚‚)â‚‚)

- Hydrochloric Acid (HCl)

- Deionized Water

2. Procedure:

- Dissolve required amounts of ZnClâ‚‚ and Thiourea in deionized water separately. To prepare samples with different [S]/[Zn] molar ratios (e.g., 0.66, 1, 1.5, 2, 3), adjust the masses of these precursors accordingly.

- Add 5 drops of HCl to the ZnClâ‚‚ solution and stir for 1 hour.

- Slowly drip the thiourea solution into the ZnClâ‚‚ solution and stir for another hour.

- Transfer 50 mL of the final mixture into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave.

- Heat the autoclave in a furnace at 220°C for 12 hours.

- Allow the autoclave to cool to room temperature naturally.

- Filter the resulting product, wash several times with deionized water, and dry at 60°C.

3. Characterization for Defect Verification:

- XRD: Confirm cubic crystal structure (ICDD 01-077-2100). Use Williamson-Hall analysis to study strain and crystal size.

- UV-Vis DRS: Calculate the band gap. Defect engineering should reduce the band gap (e.g., from 3.49 eV to 3.28 eV).

- XPS/ICP-OES: Validate the elemental composition and confirm the presence of defects via stoichiometry analysis.

- PL Spectroscopy: Analyze emission peaks to understand defect-related radiative recombination.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Surface Engineering and Defect Creation

| Reagent/ Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid (CH₃COOH) | A mild organic acid used to create oxygen defects in metal oxides (e.g., BiOCl) by facilitating the detachment of lattice oxygen via H⺠ions. | Concentration and volume are critical for controlling defect density without destroying the crystal structure [28]. |

| Thiourea (CHâ‚„Nâ‚‚S) | A common sulfur source in hydrothermal synthesis. Varying its ratio to metal precursors (e.g., ZnClâ‚‚) directly introduces and controls S and metal vacancies. | The [S]/[Metal] molar ratio is the primary control parameter for vacancy concentration and type [30]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Used as a conductive support to composite with photocatalysts (e.g., TiOâ‚‚). Enhances adsorption capacity and electron transfer, mitigating mass transfer limitations. | Should be pre-oxidized (e.g., with KMnOâ‚„) to create functional groups for better dispersion and interaction with the photocatalyst [31]. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Chloride (CTAC) | Serves as a soft template and chlorine source in the synthesis of layered BiOCl, controlling morphology and facilitating the formation of nanosheets. | Acts as both a structure-directing agent and a reactant [28]. |

| Benzaldehyde Derivatives | Used for molecular-level surface functionalization of covalent organic frameworks (COFs) to modify electron cloud density and improve charge separation. | The electronic property (electron-withdrawing or donating) of the derivative dictates the direction of electron density shift [23]. |

| AZD1092 | AZD1092, CAS:871656-65-4, MF:C24H26N4O5, MW:450.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Amantocillin | Amantocillin, CAS:10004-67-8, MF:C19H27N3O4S, MW:393.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Cocatalysts in Facilitating Surface Reaction Kinetics

Troubleshooting Common Cocatalyst Challenges

FAQ 1: My photocatalytic system shows low reaction rates despite using a cocatalyst. Could mass transfer limitations be the cause?

Yes, mass transfer limitations are a common cause of low efficiency. Even with an excellent cocatalyst, if reactants cannot reach the active sites or products cannot diffuse away, the overall reaction rate will be severely limited.

- Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Check mixing efficiency: In slurry reactors, insufficient mixing can create concentration gradients in the bulk solution, limiting the transport of reactants to the catalyst surface [1]. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations can reveal "dead zones" with different velocities in a reactor [18].

- Evaluate catalyst loading: Excessively high catalyst loadings can lead to light scattering and reduced light penetration, making part of the reactor volume useless from a radiation absorption perspective. This can be misinterpreted as a catalytic inefficiency [1].

- Optimize fluid dynamics: Increasing mixing speed can mitigate dead zones and improve convective mass flow, thereby enhancing the delivery of reactants to the cocatalyst sites [18].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between a poor cocatalyst and mass transfer limitations in my experiment?

A systematic approach is needed to isolate the root cause.

- Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Vary Agitation Speed: Conduct identical photocatalytic experiments while systematically increasing the agitation or mixing speed. If the reaction rate increases significantly, it strongly indicates the presence of mass transfer limitations in the bulk liquid [1].

- Change Catalyst Loading: Perform tests with different catalyst amounts while keeping all other parameters constant. A linear increase in rate with loading suggests kinetic control, whereas a plateau or decrease suggests mass transfer or light penetration issues [1].

- Characterize Flow Patterns: Use tracer studies or CFD modeling to understand the flow patterns and radiation distribution within your reactor, identifying stagnant regions [18].

FAQ 3: What are the key differences between using single-atom cocatalysts versus nanoparticle cocatalysts?

The choice between single-atom (SA) and nanoparticle (NP) cocatalysts involves a trade-off between atom utilization and mass transfer characteristics.

- Comparison and Selection Guide:

- Single-Atom Cocatalysts (SACs): Offer maximum atom utilization and unique electronic properties. They are ideal when the rate is determined by charge carrier availability rather than the surface reaction itself. A low density (10âµâ€“10ⶠSAs per µm²) is often sufficient to maximize cocatalytic efficiency, minimizing the use of precious metals [34].

- Nanoparticle Cocatalysts: Provide a high density of traditional active sites. However, they may be more prone to internal diffusion limitations, especially if the particles are porous or form agglomerates [1].

The following table summarizes the core differences:

Table 1: Single-Atom vs. Nanoparticle Cocatalysts

| Feature | Single-Atom Cocatalysts (SACs) | Nanoparticle Cocatalysts (NPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Atom Efficiency | Very High | Moderate to Low |

| Electronic Properties | Unique, often enhanced | Bulk-like |

| Typical Optimal Loading | Low | Higher |

| Mass Transfer Considerations | All sites are surface-exposed | Potential for internal diffusion in porous particles |

| Ideal Use Case | Charge-transfer-limited reactions | Reactions requiring specific surface ensembles |

FAQ 4: Why is my photocatalytic system producing unexpected byproducts or low selectivity?

This issue often relates to the cocatalyst's inability to control reaction pathways or the presence of competing reactions.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Cocatalyst Function: Ensure your cocatalyst is appropriate for the desired reaction. Metallic cocatalysts (e.g., Pt, Au) typically facilitate reduction reactions (e.g., Hâ‚‚ evolution), while metal oxide cocatalysts (e.g., RuOâ‚‚, IrOâ‚‚) often promote oxidation reactions (e.g., oxygen evolution) [34] [35]. Using the wrong type can lead to incomplete reactions or byproducts.

- Eliminate Contaminants: False positives and unexpected products are a significant challenge in reactions like photocatalytic nitrogen reduction. Rigorously purify feed gases (Nâ‚‚) to remove ammonia and NOx contaminants using acid traps or reduced copper catalysts. Thoroughly clean all reactor components and use high-purity water [14].

- Check for Sacrificial Reagent Interactions: If using sacrificial reagents (e.g., methanol, ethanol), ensure their oxidation intermediates are not being mistaken for products or poisoning the cocatalyst [34].

Quantitative Analysis of Cocatalyst Performance

Evaluating performance with the correct metrics is crucial for diagnosing issues and comparing systems.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Photocatalytic Systems

| Metric | Formula | Purpose & Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Turnover Frequency (TOF) | TOF = (Number of Product Molecules) / (Number of Active Sites × Reaction Time) |

Measures the intrinsic activity of each active site, independent of catalyst amount. A low TOF suggests poor inherent cocatalyst activity or site blocking [35]. |

| Apparent Quantum Efficiency (AQE) | AQE (%) = (Number of Reacted Electrons × 100) / (Number of Incident Photons) |

Quantifies the effectiveness of light utilization. A low AQE indicates inefficient light absorption, rapid charge recombination, or poor mass transfer [35]. |

| Space-Time Yield (STY) | STY (mol/cm²·s) |

Evaluates reactor efficiency with respect to throughput and reactor volume, helping to quantify mass transfer effectiveness [18]. |

Advanced Diagnostic and Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and overcoming limitations in cocatalyst-assisted photocatalysis, integrating the concepts from the FAQs and tables.

Diagnosing Cocatalyst System Limitations

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Cocatalyst Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial Reagents | Consume photogenerated holes, allowing isolation and study of the reduction half-reaction (e.g., Hâ‚‚ evolution) at the cocatalyst. | Methanol, Ethanol, Triethanolamine. Use high purity to avoid side reactions [34] [14]. |

| Purified Feed Gases | Provide reactant feedstock free of contaminants that can cause false positives or poison active sites. | N₂ for N₂ reduction; Ar for inert atmosphere. Must be purified using acid traps (H₂SO₄) for NH₃ and KMnO₄/alkaline solution or reduced copper for NOx [14]. |

| Cocatalyst Precursors | Source for loading metal-based cocatalysts onto semiconductors. | Metal salts (e.g., H₂PtCl₆) or organometallic compounds. "Reactive deposition" methods can achieve a self-homing effect for single-atom cocatalysts [34]. |

| High-Purity Water | Solvent for aqueous-phase reactions; purity is critical to prevent measurement artifacts. | Fresh redistilled or ultrapure water. Always measure and report baseline ammonia/NOx concentration [14]. |

| CFD Simulation Software | Models fluid flow, radiation distribution, and mass transfer in photoreactors to identify and mitigate dead zones. | Cloud-based platforms (e.g., SimScale) or commercial packages. Use k-omega turbulence models for accurate mass transfer simulation [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Differentiating Kinetic and Mass Transfer Control

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for diagnosing the root cause of inefficiency in a cocatalyst-loaded photocatalytic system.

Aim: To determine whether the observed reaction rate is limited by the intrinsic surface kinetics of the cocatalyst or by mass transfer of reactants/products.

Materials:

- Photocatalytic reactor (e.g., slurry batch reactor with variable-speed stirring)

- Light source with calibrated intensity

- Cocatalyst-loaded semiconductor powder

- Target pollutant (e.g., dichloroacetic acid, phenol) or water/sacrificial agent mixture for Hâ‚‚ evolution

- Analytical equipment (e.g., GC, HPLC, UV-Vis for product quantification)

Procedure:

- Baseline Activity Measurement: Conduct the photocatalytic reaction under your standard conditions, measuring the product formation rate (e.g., µmol H₂·hâ»Â¹ or degradation rate constant).

- Agitation Variation Test:

- Repeat the experiment at least three times, systematically increasing the agitation speed (RPM) while keeping catalyst loading, light intensity, and reactant concentration constant.

- Plot the observed reaction rate versus agitation speed.

- Catalyst Loading Test:

- Perform a series of experiments with different catalyst loadings (e.g., from 0.1 to 1.0 g/L) under a constant, high agitation speed that was found to be sufficient in step 2.

- Plot the observed reaction rate versus catalyst loading.

- Data Analysis and Diagnosis:

- Interpret Agitation Test: If the reaction rate increases with agitation speed, your system is under significant mass transfer control. The point where the rate becomes independent of speed indicates a shift toward kinetic control [1].

- Interpret Loading Test: A linear increase in rate with loading suggests kinetic control. A plateau suggests that either all light is being absorbed (an optical limitation) or that the surface area is no longer the limiting factor, potentially due to the onset of agglomeration and internal diffusion [1].

- CFD Modeling (Advanced): For immobilized systems or complex reactors, build a CFD model to solve the momentum and mass transport equations simultaneously. This will visualize flow patterns and concentration gradients, directly identifying dead zones and mass transfer limitations [18].

Integrating Photocatalysis with Membrane Technology for Continuous Flow Systems

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting and FAQs

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when integrating photocatalysis with membrane technology in continuous flow systems, with a specific focus on overcoming mass transfer limitations.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Rapid Membrane Fouling and Flux Decline

Problem Description: Significant decrease in permeate flux occurs shortly after system startup, requiring frequent cleaning cycles.

Underlying Mass Transfer Challenge: Poor hydrodynamics and concentration polarization lead to accumulation of pollutants/catalyst on membrane surface [36].

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Check flow velocity: Increase cross-flow velocity to enhance shear forces that sweep away accumulating materials. Turbulent flow (Re > 4000) is preferred over laminar flow [37].