Optimizing Step Size in Finite Displacement Phonon Calculations: A Guide for Accuracy and Efficiency

Finite displacement method is a cornerstone technique for first-principles phonon calculations, essential for determining dynamical stability, thermal properties, and phase transitions in materials.

Optimizing Step Size in Finite Displacement Phonon Calculations: A Guide for Accuracy and Efficiency

Abstract

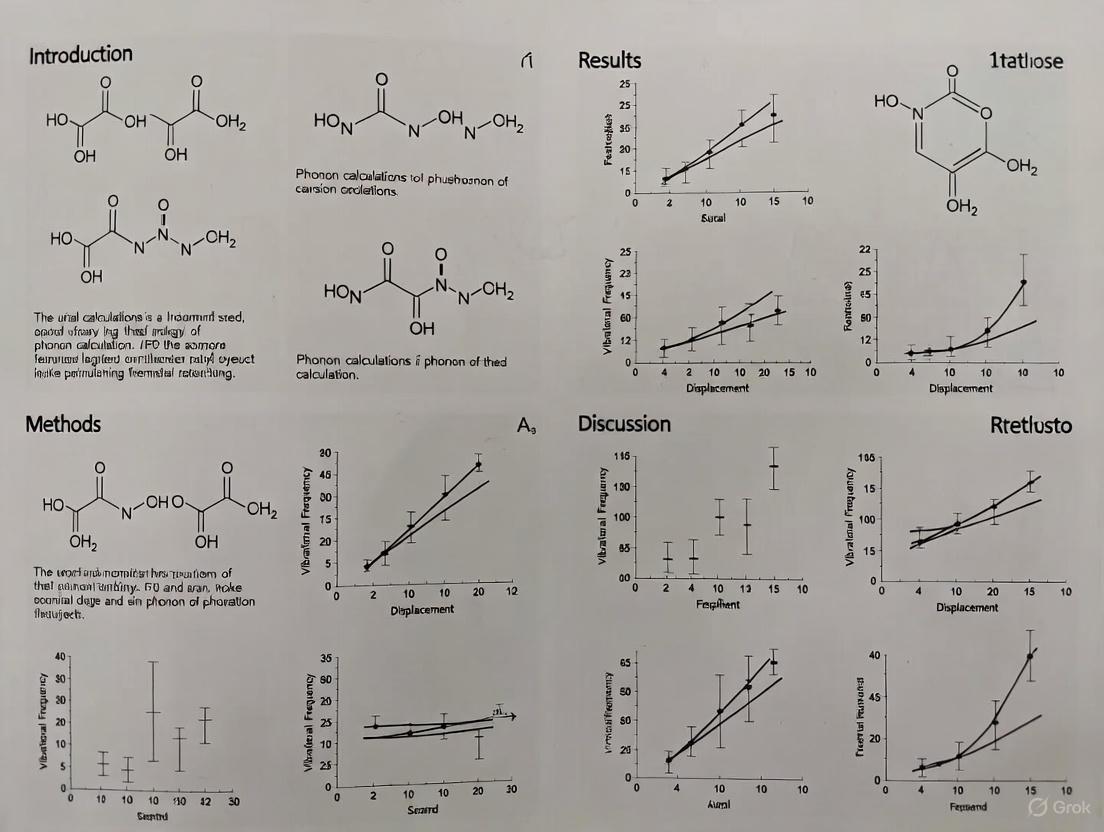

Finite displacement method is a cornerstone technique for first-principles phonon calculations, essential for determining dynamical stability, thermal properties, and phase transitions in materials. However, its accuracy and computational cost are critically dependent on the choice of displacement step size. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers on the principles and optimization of step size. We cover foundational theory, practical methodologies, troubleshooting for common issues like imaginary modes, and validation techniques against benchmarks and machine learning potentials. The content is tailored to empower scientists in making informed choices that balance numerical precision with computational feasibility, ultimately accelerating materials discovery and development.

The Fundamentals of Phonons and the Finite Displacement Method

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is geometry optimization crucial before a phonon calculation? A proper phonon spectrum requires that the calculation is performed on a fully relaxed structure, meaning both the internal atomic positions and the lattice vectors themselves must be at their energy minimum. Performing a phonon calculation on an unoptimized geometry can lead to imaginary frequencies (negative values on the phonon dispersion plot), which are unphysical for stable crystals. It is recommended to use tight convergence thresholds for the geometry optimization to ensure high accuracy. [1]

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between harmonic and anharmonic phonon behavior? Within the harmonic approximation, the potential energy is treated as a parabola, phonons do not interact, and they have infinite lifetimes. Anharmonicity, which accounts for the real, non-parabolic shape of the potential, introduces phonon-phonon scattering, leading to finite phonon lifetimes. This anharmonic scattering is the fundamental mechanism limiting lattice thermal conductivity in materials. [2] [3]

Q3: My phonon calculation resulted in imaginary frequencies. What does this mean and what should I do? Imaginary frequencies (often shown as negative values on plots) indicate a dynamical instability. This can mean one of two things:

- The structure you started with was not at a true energy minimum. Solution: Ensure you have performed a thorough geometry optimization, including optimizing the lattice vectors, before the phonon calculation. [1]

- The material may be unstable in that particular crystal structure at the calculated conditions and may be undergoing a phase transition.

Q4: How do experimental techniques like IR, Raman, and Inelastic Neutron Scattering (INS) differ in probing phonons? These techniques are governed by different selection rules and provide complementary information:

- IR Spectroscopy: Measures phonon modes that involve a change in the dipole moment. It is sensitive to modes with odd symmetry.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Measures phonon modes that involve a change in polarizability. It is sensitive to modes with even symmetry.

- Inelastic Neutron Scattering (INS): Can measure all phonon modes across the entire Brillouin zone,不受 selection rules限制, making it a powerful tool for obtaining the full phonon dispersion. [2]

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Phonon Calculation Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Imaginary Frequencies | 1. Incomplete geometry optimization.2. True dynamical instability (phase transition).3. Insufficient k-point grid for SCF. | 1. Re-optimize geometry with lattice vectors and tight convergence. [1]2. Investigate lower-symmetry phases.3. Use a denser k-point grid in the initial self-consistent field (SCF) calculation. |

| Poor Convergence of Thermal Conductivity | 1. q-point mesh for phonons is too coarse.2. Supercell for finite displacements is too small.3. Neglected higher-order force constants (anharmonicity). | 1. Increase the density of the q-point mesh. [4]2. Use a larger supercell to capture long-range interactions more accurately. [1]3. Include third-order (or higher) force constants in the calculation. |

| Inaccurate Thermal Properties | 1. Over-reliance on the harmonic approximation.2. High anharmonicity not captured.3. Defects not accounted for. | 1. Use methods that include anharmonicity, like TDEP or SCPH. [3]2. Employ ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) to extract temperature-dependent phonons. [3]3. Explicitly model defects in supercells, as they can strongly scatter phonons. [4] |

The Role of Step Size in Finite Displacement Calculations

The finite displacement method is a common technique for calculating phonons and force constants. It involves creating supercells where atoms are displaced from their equilibrium positions, and the resulting forces are used to compute the dynamical matrix. The choice of displacement step size is critical:

- Too Small Step Size: Numerical noise and rounding errors from the DFT force calculation can dominate, leading to inaccuracies in the force constants.

- Too Large Step Size: The displacement moves the atoms too far from the harmonic region, and anharmonic effects contaminate the calculation of the second-order force constants.

Optimization Protocol:

- Benchmarking: Perform a series of finite displacement calculations for a known, high-symmetry material (like silicon) using different step sizes.

- Convergence Test: Compare the resulting phonon frequencies and dispersion curves. The optimal step size is the one after which these properties do not change significantly.

- Software Defaults: Start with the default step size in your software (e.g.,

0.01 nmin many codes) and perform a convergence test around that value. Modern interfaces, like the one for Quantum ESPRESSO, now offer improved support for these calculations. [5]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Basic Phonon Dispersion Calculation via Finite Displacement

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard phonon calculation using the finite displacement method, a cornerstone of lattice dynamics research. [1] [6] [3]

1. Structure Optimization:

- Objective: Obtain the ground-state equilibrium geometry.

- Procedure:

- Start with the initial crystal structure.

- Perform a geometry optimization task (e.g., using DFT).

- Crucially, enable the "Optimize Lattice" option to relax both atomic positions and lattice vectors.

- Set the energy and force convergence criteria to "Tight" or "Very Good."

2. Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation:

- Objective: Obtain the converged electronic charge density of the optimized structure.

- Procedure:

- Use the optimized structure from Step 1.

- Run a single-point SCF calculation with a dense k-point grid to ensure accurate electronic structure.

3. Force Constant Calculation via Finite Displacement:

- Objective: Calculate the second-order force constants.

- Procedure:

- Build a supercell of the optimized primitive cell. A larger supercell yields more accurate results but at a higher computational cost. [1]

- Generate a set of atomic displacements within the supercell. The step size for these displacements must be carefully chosen, as detailed in the troubleshooting section above.

- For each displacement configuration, perform a DFT calculation to compute the atomic forces.

- The force constants are derived from the relationship between the displacements and the resulting forces.

4. Phonon Spectrum Generation:

- Objective: Obtain the phonon dispersion curves and density of states.

- Procedure:

- The force constants from Step 3 are used to build the dynamical matrix.

- Diagonalize the dynamical matrix for a set of q-points along high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin Zone.

- The eigenvalues yield the phonon frequencies, and the eigenvectors represent the atomic vibration patterns.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Calculating Lattice Thermal Conductivity

This protocol describes the workflow for calculating the lattice thermal conductivity (κL), a key property influenced by anharmonic phonon scattering. [4] [2]

1. Harmonic Phonon Calculation:

- Follow Protocol 1 to obtain the second-order force constants and the full phonon dispersion.

2. Third-Order Force Constant Calculation:

- Objective: Capture three-phonon scattering processes, which are the primary source of thermal resistance in non-metallic solids.

- Procedure: Use the finite displacement method in a supercell to calculate the third-order force constants. This involves calculating forces for configurations with multiple atoms displaced simultaneously.

3. Solve the Boltzmann Transport Equation (BTE):

- Objective: Compute the lattice thermal conductivity.

- Procedure: Use a solver (e.g., ShengBTE) that takes the second- and third-order force constants as input. The solver calculates the phonon lifetimes (τ) and group velocities (v) for each mode, which are used to compute κL using the formula: [2] κα = Σω (Cv,ω * vα,ω² * τω) where Cv,ω is the mode's heat capacity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools for Lattice Dynamics

| Item/Software | Function/Brief Explanation | Relevance to Finite Displacement |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code (e.g., VASP, Abinit, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs the underlying electronic structure calculations to compute energies and forces for displaced atomic configurations. | The core engine. Its accuracy and efficiency directly determine the quality of the force constants. |

| Phonopy, ShengBTE | Post-processing codes. Phonopy calculates harmonic phonons from finite displacements. ShengBTE solves the BTE for thermal conductivity using 2nd and 3rd order force constants. | Essential for converting the raw force data from DFT into phonon properties and thermal transport coefficients. |

| Supercell | A larger cell built by repeating the primitive cell, used to capture interactions between periodic images in the finite displacement method. | A larger supercell is needed for accurate force constants, but it exponentially increases the number of required DFT calculations. [1] |

| Optimized Step Size | The magnitude of the atomic displacement from equilibrium. | A critical parameter. An improperly chosen step size is a major source of error, as it can introduce either numerical noise or anharmonic contamination. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | Machine-learned models trained on DFT data that can predict energies and forces with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost. | Can dramatically accelerate force constant calculations by rapidly providing forces for the many displacement configurations. [2] [5] |

The logical relationship and data flow between these tools in a typical workflow is shown below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental equation for the force constant in the finite displacement method?

The force constant, which describes the relationship between atomic displacement and the resulting force, is numerically approximated by a central difference formula. For an atom displaced in direction i, the force constant with respect to another atom in direction j is calculated as [7] [8]:

Φᵢⱼ ≈ - [Fⱼ⁺ - Fⱼ⁻] / [2 * Δrᵢ]

Here, Fⱼ⁺ and Fⱼ⁻ are the forces in direction j when the atom is displaced by a small, finite amount +Δrᵢ and -Δrᵢ from its equilibrium position, respectively.

2. Why is step size (Δr) a critical parameter in these calculations?

The step size Δr is crucial because it must balance two competing sources of error [7] [9]:

- Too large a step: The displacement takes the system too far from the harmonic (quadratic) region of the potential energy surface, making the central difference approximation invalid and introducing anharmonic errors.

- Too small a step: The difference between the two forces (

F⁺ - F⁻) becomes very small, and the calculation becomes dominated by numerical noise from the finite precision of the force calculator (e.g., DFT). This leads to unstable force constants.

3. What are typical values for the displacement step size (Δr)?

Commonly used displacement steps fall within a specific range, though the optimal value may vary by system. The table below summarizes values from different sources and methodologies.

| Source / Context | Recommended Step Size (Δr) |

Notes / Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ASE Documentation [7] | 0.05 Å | Example given for bulk Aluminum using an EMT calculator. |

| Machine Learning Potentials [9] | 0.01 - 0.05 Å | Used for generating random displacements to train MLIPs for phonon calculations. |

4. My phonon spectrum shows imaginary frequencies (negative values) at the gamma point. What could be wrong? Imaginary frequencies at the gamma point (q=0) often indicate a violation of the acoustic sum rule. This rule requires that the sum of all force constants for a displaced atom must be zero, which ensures the stability of the lattice. This can be caused by [7] [10]:

- An interaction range that is too short in the force constant calculation, failing to capture all necessary atomic interactions.

- An equilibrium structure that is not fully optimized (residual forces or stress). Ensure your structure is relaxed with tight convergence criteria for both forces and lattice vectors [10].

5. How can I check if my chosen step size is appropriate? You can perform a step size convergence test:

- Calculate phonon frequencies (e.g., at a high-symmetry point in the Brillouin zone) for a series of step sizes (e.g., 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.05 Å).

- Plot the frequencies against the step size.

- The optimal step size is typically within the "plateau" region where the phonon frequencies are stable and do not change significantly with small changes to

Δr.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Imaginary frequencies across the entire spectrum | 1. Structure is not at equilibrium.2. Step size is too large, causing anharmonicity.3. Insufficient k-point sampling or other calculator settings. | 1. Re-optimize geometry with tighter force/stress convergence [1] [10].2. Reduce the displacement step Δr and perform a convergence test.3. Verify calculator (e.g., DFT) settings are accurate. |

| Unphysical "band gaps" or severe distortions in the spectrum | 1. Force constant matrix is not properly symmetrized.2. In alloys: Neglecting either mass or force constant fluctuations can cause artificial gaps [11]. | 1. Ensure the phonon code enforces crystal symmetry and the acoustic sum rule [7].2. For disordered systems, use methods that account for both mass and force constant disorder. |

| High computational cost for large supercells | The number of single-point force calculations scales as 6 × N, where N is the number of atoms in the supercell. | 1. Use machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) trained on a small set of displaced structures to compute forces [9].2. Exploit crystal symmetry to reduce the number of unique displacements [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for Finite Displacement Calculations

| Component | Function | Research Context & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Force Calculator | Computes the potential energy and atomic forces for a given atomic configuration. This is the core engine (e.g., DFT, EMT, classical potentials). | The choice (DFT vs. classical potential) dictates accuracy and cost. For step size studies, ensure the force calculator is highly converged to isolate numerical error. |

| Phonon Software | Implements the finite displacement method, manages supercell creation, displacements, and constructs the dynamical matrix. (e.g., ASE [7], Phonopy [8], VASP [12]). | These packages automate the workflow. The researcher's role is to configure key parameters like supercell size and displacement distance (Delta r). |

| Optimized Structure | The equilibrium atomic configuration and lattice vectors. | Critical Pre-requisite: Phonons are computed around equilibrium. Perform a full geometry optimization (including lattice vectors) with tight convergence criteria before starting [1]. |

| Supercell | A repetition of the primitive cell, large enough to capture the long-range nature of the force constants. | Size must be converged. Automatic detection often uses a cutoff radius based on atomic covalent radii [10]. |

Workflow of the Finite Displacement Method

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of steps involved in calculating phonon force constants via the finite displacement method.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental role of step size in finite displacement phonon calculations?

The step size (or displacement distance) is a critical parameter in the finite displacement method. It represents the small perturbation applied to atomic positions to compute the force constants that define the interatomic forces. The calculation approximates the second derivative of the energy (force constants) using the central difference formula: C_mai^nbj ≈ (F-_nbj - F+_nbj) / (2 * delta), where delta is the step size, and F+/F- are the forces when an atom is displaced in the positive/negative direction [13]. An optimal step size balances between numerical precision (avoiding truncation errors from too-large steps) and physical accuracy (avoiding round-off errors from too-small steps).

Q2: What are the symptoms of an incorrectly chosen step size?

Choosing an improper step size manifests in specific computational errors:

- Step size too large: The harmonic approximation breaks down, leading to anharmonic effects. This can cause imaginary phonon frequencies (soft modes) in materials that are dynamically stable, incorrectly suggesting structural instability [14].

- Step size too small: Forces become dominated by numerical noise from the convergence thresholds of the electronic structure calculation (e.g., DFT). This results in inaccuracies in the force constants and spurious low-frequency phonons [15] [13].

- General failure: The phonon dispersion curves may show unphysical behavior, such as gaps or overlaps, and derived properties like thermal expansion or bulk modulus will deviate significantly from experimental or DFT benchmark data [14].

Q3: What is a recommended default step size, and how should I optimize it?

While a general default value exists, system-specific testing is crucial.

| System Type | Recommended Step Size (Å) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| General Purpose | 0.015 [15] | A commonly used, robust default in many codes like VASP. |

| High-Symmetry Crystals | 0.01 - 0.02 | Test for symmetry preservation. |

| Soft, Porous Frameworks (e.g., MOFs) | 0.005 - 0.015 | Requires careful testing due to flexible structures [14]. |

Optimization Protocol:

- Convergence Test: Perform phonon calculations for a key symmetry point (e.g., Γ-point) across a range of step sizes (e.g., 0.005 Å to 0.05 Å).

- Stability Check: Monitor the lowest phonon frequency. It should converge to a stable, real value.

- Benchmarking: Compare with a highly accurate reference, such as Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) results or experimental data for phonon frequencies or thermal expansion, if available [16] [14].

Q4: How does step size interact with other computational parameters?

Step size does not operate in isolation; it is deeply coupled with other simulation settings:

| Computational Parameter | Interaction with Step Size |

|---|---|

| Energy/Force Convergence | A stricter force convergence threshold (e.g., ≤ 10^(-6) eV/Å) is mandatory when using small step sizes to prevent numerical noise from dominating the finite-difference force calculation [14]. |

| Supercell Size | The finite displacement method requires a supercell large enough to capture long-range interactions. The step size is optimized for a given supercell size. |

| Machine Learning Potentials | When using ML potentials (e.g., MACE), the step size must be chosen relative to the training data's displacement range to ensure the model operates within its reliable domain [14] [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Imaginary Phonon Frequencies (Soft Modes) in a Stable Material

Possible Cause 1: Step size is too large, introducing anharmonicity.

- Solution: Reduce the step size systematically and recalculate. Follow the optimization protocol in FAQ Q3 to find the value where these imaginary frequencies vanish.

Possible Cause 2: Inadequate supercell size or insufficient k-point sampling.

- Solution: Ensure the supercell is large enough to make forces between periodic images negligible. Concurrently, reduce the k-point density in the supercell calculation to maintain constant reciprocal-space sampling relative to the primitive cell [15].

Possible Cause 3: The underlying force calculator (DFT or ML potential) has not found the true ground state structure.

- Solution: Before phonon calculations, perform a rigorous full cell relaxation (including atomic positions and lattice vectors) until forces and stresses are fully converged. The ASE

L-BFGSandFrechetCellFilteroptimizers are often used for this purpose [14].

Problem: Unphysical "Spikes" or Noise in the Phonon Density of States

Possible Cause 1: Step size is too small, amplifying numerical noise in the forces.

- Solution: Increase the step size incrementally. If the problem persists, tighten the force convergence criteria in your DFT calculator (e.g., set

PREC=Accuratein VASP) [15].

Possible Cause 2: Underlying force calculator is not sufficiently accurate.

- Solution: Validate your calculator. For ML potentials, ensure they are specifically fine-tuned for phonon properties, as general-purpose models (e.g., MACE-MP-0) may struggle with accurate dynamical predictions compared to specialized versions (e.g., MACE-MP-MOF0 for metal-organic frameworks) [14].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Phonon Screening with ML Potentials

This protocol, derived from recent studies, enables rapid phonon property screening for large material classes [14] [9].

- Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained, phonon-accurate ML interatomic potential (e.g., fine-tuned MACE models).

- Structure Relaxation: Perform a full, unconstrained cell relaxation using the ML potential to find the equilibrium geometry.

- Supercell Generation: Construct a supercell of appropriate size (e.g., 2x2x2 or 3x3x3, depending on the system).

- Force Calculation: Use the finite displacement method with the optimized step size (typically 0.01-0.02 Å) and the ML potential to compute the force constants matrix.

- Post-Processing: Use a tool like

phonopyto construct the dynamical matrix, diagonalize it across the Brillouin zone, and obtain phonon dispersions and density of states [17].

Protocol 2: Advanced Displacement with Non-Diagonal Supercells

For complex unit cells or specific wave vectors, the non-diagonal supercell method can drastically improve computational efficiency [16].

- Target Wave Vector: Identify the wave vector q= (n₁/m₁, n₂/m₂, n₃/m₃) for which phonon properties are desired.

- Supercell Construction: Build a non-diagonal supercell with a size equal to the least common multiple (LCM) of

(m₁, m₂, m₃). This is often significantly smaller than a conventional diagonal supercell. - Displacement and Calculation: Apply the finite displacement method within this optimized supercell to compute the necessary force constants.

The workflow for this advanced approach is summarized in the diagram below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and software essential for modern finite displacement phonon calculations.

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| VASP [15] | A widely used DFT code; implements finite displacement method via IBRION=5/6. |

Requires high PREC and ENCUT for accurate forces. Can be computationally expensive. |

| phonopy [17] | An open-source package for post-processing force constants to obtain phonon dispersions, DOS, and thermal properties. | Essential for standard workflows; interfaces with many DFT and ML potential codes. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [13] | A Python library for setting up, running, and analyzing atomistic simulations; provides a unified interface. | Simplifies workflow automation and coupling between different calculators (DFT/ML) and phonopy. |

| MACE ML Potentials [14] [9] | State-of-the-art Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials; enable high-throughput phonon calculations at near-DFT accuracy but vastly reduced cost. | Requires a pre-trained model suitable for your material class (e.g., MACE-MP-MOF0 for MOFs). |

| ARES-Phonon [16] | A specialized package implementing the non-diagonal supercell finite displacement method. | Can be an order of magnitude faster than diagonal supercell methods for complex systems. |

A technical guide for computational materials researchers navigating the critical choice between finite displacement and density functional perturbation theory for lattice dynamics calculations.

This technical support guide provides a comparative overview of the Finite Displacement (FD) method and Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) for calculating phonon properties in materials. Understanding the differences between these two approaches is essential for researchers conducting lattice dynamics calculations, particularly in the context of thesis research focused on step-size optimization in finite displacement methodologies.

The Finite Displacement (FD) method (also called the "frozen phonon" method) calculates force constants by displacing atoms from their equilibrium positions in a supercell and computing the resulting forces [18]. The second-order force constants are obtained through finite differences [15].

In contrast, Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) computes the linear response of the electron density to atomic displacements by solving the Sternheimer equation, providing an analytical approach to determining second derivatives of the total energy [19] [20].

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each method:

| Feature | Finite Displacement (FD) | Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Numerical finite differences through atomic displacements [18] | Analytical solution of quantum-mechanical response [19] |

| Typical Supercell Requirement | Required (commensurate with phonon wavevector) [21] | Primitive cell often sufficient [21] |

| Implementation in VASP | IBRION = 5 or 6 [15] |

IBRION = 7 or 8 [19] |

| Symmetry Usage | IBRION=6 uses symmetry to reduce displacements [15] |

IBRION=8 uses symmetry to reduce displacements [19] |

| Key Outputs | Force constants, phonon frequencies, elastic tensors (with ISIF≥3) [15] | Force constants, phonon frequencies, Born effective charges, dielectric properties [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Finite Displacement Method Protocol

The finite displacement approach requires careful setup to ensure accurate force constant calculations:

Initial Structure Relaxation: Begin with a fully relaxed structure (atomic positions and/or lattice constants) using standard relaxation algorithms (

IBRION=2in VASP). Ensure high accuracy in forces to provide a reliable baseline for displacement calculations [22].Supercell Construction: Create a supercell commensurate with the phonon wavevectors of interest. The supercell size must be large enough to capture the desired phonon interactions [21] [18].

Displacement Generation: Use codes like

phonopyto generate displaced structures. For example:phonopy -d --dim="2 2 2" -c structure_filecreates a 2×2×2 supercell with symmetry-inequivalent displacements [18].Force Calculations: For each displaced structure, perform a single-point force calculation. In VASP, set

IBRION = 5(displace all atoms) orIBRION = 6(uses symmetry to reduce calculations),NSW = 1,PREC = Accurate, andNFREE = 2(for central differences) [15].Force Constant Determination: The force constants matrix is built from the calculated forces. Post-processing tools like

phonopycan then compute the dynamical matrix and derive phonon frequencies across the Brillouin zone [22].

DFPT Method Protocol

The DFPT workflow offers a more integrated approach to phonon calculation:

Structure Preparation: As with FD, begin with a fully relaxed primitive cell structure. Accurate symmetry detection is crucial for proper assignment of irreducible representations [22].

DFPT Calculation Setup: In VASP, use

IBRION = 7(all displacements) orIBRION = 8(symmetry-reduced). SetLEPSILON = .TRUE.to compute dielectric properties and Born effective charges [19] [22].Linear Response Calculation: The code self-consistently solves the Sternheimer equation for the linear change of the wavefunctions with respect to atomic displacements, avoiding the need for explicit supercell constructions [19].

Force Constant Determination: The second-order force constants are obtained from the linear response of the electron density. Although DFPT is analytical, some implementations still use finite differences for certain components like the second derivative of the exchange-correlation functional [19].

Result Extraction: The dynamical matrix is constructed and diagonalized to yield phonon modes and frequencies. Additional properties like Born effective charges are computed analytically [19].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Method Selection and Applicability

Q: Which method should I choose for my specific system and research goals?

A: The choice depends on your system size, computational resources, and desired properties:

- Choose Finite Displacement for:

- Choose DFPT for:

Q: My DFPT calculation won't run with my chosen functional/pseudopotential. What's wrong?

A: DFPT implementations often have limitations. Consult the documentation for your specific code. For example, CASTEP's DFPT does not support ultrasoft pseudopotentials, DFT+U, meta-GGAs, or hybrid functionals, in which case finite displacement should be used [23]. VASP's DFPT routines are primarily limited to LDA and GGA functionals [19].

Convergence and Accuracy Issues

Q: How do I address imaginary frequencies (negative values) in my phonon calculations?

A: Small negative frequencies near the Gamma point can occur due to numerical noise in both methods [21]. First, ensure your structure is fully relaxed with accurate forces. Check convergence with respect to:

- Plane-wave cutoff (ENCUT): Increase systematically until phonon frequencies converge [15]

- k-point sampling: Use a sufficiently dense mesh [15] [22]

- Finite displacement step size (POTIM): Test different values if using FD [15]

- Numerical thresholds: Tighten convergence criteria (EDIFF, EDIFFG) for both electronic and ionic steps [22]

Q: My finite displacement calculation is taking too long. How can I make it more efficient?

A: Several strategies can improve efficiency:

- Use

IBRION=6instead ofIBRION=5to leverage symmetry and reduce the number of displacements [15] - Ensure your KPOINTS mesh is appropriate for the supercell size (reduce density proportionally to supercell expansion) [15]

- Test whether a slightly smaller supercell provides sufficient accuracy

- Use

PREC = AccurateandADDGRID = .TRUE.only when necessary, as they increase computational cost [15]

Step Size Optimization in Finite Displacement

Q: How do I determine the optimal displacement step size (POTIM) for finite displacement calculations?

A: Step size optimization is critical for accurate results:

- Start with the default value (0.015 Å in VASP) [15]

- Perform test calculations with different POTIM values (e.g., 0.01, 0.015, 0.02 Å) while monitoring the convergence of phonon frequencies

- Compare results with DFPT calculations if possible, as DFPT eliminates step-size dependence [19]

- Consider using

NFREE=4(four displacements per ion) for higher accuracy, though it doubles the computational cost compared toNFREE=2[15]

Q: What are the consequences of choosing a step size that is too large or too small?

A: Both extremes introduce errors:

- Too small: Numerical noise from finite precision arithmetic dominates, leading to instabilities in force constants

- Too large: The system moves beyond the harmonic approximation, introducing anharmonic effects that corrupt the phonon spectrum

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Parameters

This table summarizes key parameters and their roles in phonon calculations for both finite displacement and DFPT approaches.

| Parameter/Code | Function/Role | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| POTIM | Controls displacement step size in FD | VASP defaults to 0.015 Å; requires optimization [15] |

| NFREE | Number of displacements per ion in FD | NFREE=2: central differences; NFREE=4: four displacements [15] |

| ENCUT | Plane-wave energy cutoff | Must be sufficiently high (≈30% above default) for stress tensor convergence [15] |

| IBRION | Determines ionic relaxation method | 5/6: FD; 7/8: DFPT in VASP [15] [19] |

| LEPSILON | Controls dielectric property calculation | Should be .TRUE. for Born charges and dielectric tensors [19] |

| phonopy | Post-processing for phonon properties | Works with both FD and DFPT results from VASP [15] [19] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My phonon dispersion calculation shows imaginary frequencies (negative values). What does this mean and how can I fix it? Imaginary frequencies indicate dynamical instability, meaning the atomic structure is not in its lowest energy configuration and may undergo a phase transition [9]. To resolve this:

- Fully optimize the geometry: Perform a geometry optimization that includes both atomic positions and lattice vectors using tight convergence criteria before the phonon calculation [1] [14]. This is a critical step often missed.

- Verify the computational model: Ensure your calculation setup, including functional, pseudopotentials, and k-point grid, is appropriate for your material [24].

- Check supercell size: For some complex materials, a larger supercell may be required to capture all relevant interactions [25].

Q2: My Phonon Density of States (PDOS) plot looks different when calculated separately versus in a combined bands/DOS calculation. Which one is correct? This discrepancy often arises from how reciprocal space is sampled. A standalone PDOS calculation might only compute vibrations at a limited set of q-points determined by your supercell size [25]. For a smoother, more accurate PDOS that matches your band structure, you must use interpolation.

- Solution: Enable the

INTERPHESSoption or its equivalent in your software to interpolate the force constants onto a denser q-point grid. Note that this interpolation is only reliable if your initial supercell is large enough to capture the decay of interatomic force constants [25].

Q3: Phonon calculations are computationally too expensive for my large system (e.g., a Metal-Organic Framework). Are there faster alternatives? Yes, Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) can drastically reduce the cost while maintaining high accuracy.

- Method: Use a pre-trained universal potential (foundation model) like MACE-MP-0 [24] [14]. For higher accuracy, especially for specific material classes, fine-tune the model on a small dataset of DFT calculations from your system [14].

- Benefit: This approach can accelerate phonon calculations by orders of magnitude, making high-throughput screening of phonon-mediated properties like thermal expansion feasible for large systems [9] [14].

Q4: How does the step size (atomic displacement) in the finite displacement method affect the results? The displacement step size is a critical parameter.

- Too Small: Forces may be too small to calculate accurately, leading to numerical noise and potential imaginary frequencies.

- Too Large: The harmonic approximation may break down, as the potential energy surface is no longer parabolic, resulting in an inaccurate dynamical matrix [9].

- Best Practice: Typical displacements range from 0.01 Å to 0.05 Å [9]. A value of 0.01 Å is a standard and safe starting point for many materials [26]. Some modern approaches use a subset of supercells with all atoms randomly perturbed within this range to efficiently generate training data for MLIPs [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate or Unphysical Phonon Dispersion

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaginary frequencies at high-symmetry points. | Incomplete geometry optimization [1] [14]. | Check if forces on all atoms are negligible and the lattice is optimized. | Re-optimize geometry with Optimize Lattice enabled and Very Good convergence [1]. |

| "Noisy" or discontinuous bands. | Insufficient q-point sampling for interpolation [25] [27]. | Check the number of points used in the band path and the interpolation grid. | Increase the i-grid (e.g., to 18x18x18) and use a denser path [27]. |

| Incorrect band gaps or energies. | Under-converged DFT parameters or small supercell [25]. | Test convergence with k-point grid and energy cutoff. | Use a larger supercell for the force calculation (e.g., 3x3x3) and converge DFT parameters [25]. |

Problem: High Computational Cost

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation is too slow for high-throughput screening. | Traditional DFT with finite displacement is inherently expensive for large cells [9] [14]. | Identify the bottleneck: number of atoms, displacements, or DFT cost. | Adopt Machine Learning Potentials. Fine-tune a foundation model (e.g., MACE) on a small set of DFT data [24] [14]. |

| Phonon DOS is sparse or lacks detail. | Sparse sampling of the Brillouin Zone [25]. | Check the number of q-points used for the DOS. | Use a denser q-grid specifically for the DOS calculation or a larger supercell [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and their functions in finite displacement phonon calculations.

| Item | Function in Calculation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized Crystal Structure | Serves as the equilibrium configuration for displacements. The foundation of the calculation [1] [28]. | Must be fully relaxed (ions and lattice) to avoid imaginary frequencies [14]. |

| Finite Displacement (Δ) | A small perturbation to probe the harmonic force constants [9] [26]. | Step size is critical; typically 0.01-0.05 Å [9]. Too large violates harmonic approximation. |

| Supercell | A repeated cell used to capture long-range interatomic forces [25] [28]. | Size must be chosen so that force constants decay within the supercell radius [25]. |

| Dynamical Matrix | The core mathematical object whose eigenvalues are phonon frequencies squared [29]. | Built from the force constants obtained via finite displacement [26]. |

| q-point Path | A set of points in the Brillouin zone along which the phonon dispersion is plotted [26] [27]. | Must respect crystal symmetry to correctly visualize all vibrational modes [27]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | Fast, accurate surrogate for DFT that predicts energies/forces [9] [24]. | Enables phonon calculations on large, complex systems (e.g., MOFs) that are prohibitive for pure DFT [14]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Finite Displacement Method with DFT

This is the foundational methodology for calculating phonon properties from first principles [1] [28].

- Geometry Optimization: Fully optimize the crystal structure (atomic positions and lattice vectors) using high convergence thresholds (e.g., max force < 0.001 eV/Å) [1].

- Supercell Construction: Construct a supercell large enough to capture the relevant interatomic interactions. A 2x2x2 or 3x3x3 expansion is common [28].

- Atomic Displacements: Generate a set of supercells where atoms are displaced from their equilibrium positions. A standard displacement is 0.01 Å along Cartesian directions [26].

- Force Calculations: For each displaced supercell, perform a DFT single-point calculation to obtain the Hellmann-Feynman forces on all atoms.

- Build Dynamical Matrix: Construct the force constant matrix and the dynamical matrix from the computed forces.

- Solve for Phonons: Diagonalize the dynamical matrix across a q-point path (for dispersion) and a dense q-point grid (for DOS) to obtain phonon frequencies and modes [27].

- Compute Thermodynamics: Use the phonon DOS to calculate vibrational free energy, entropy, and heat capacity within the quasi-harmonic approximation.

Protocol 2: Accelerated Workflow using Machine Learning Potentials

This modern protocol leverages ML to drastically reduce computational cost [9] [24] [14].

- Acquire a Foundation Model: Start with a pre-trained universal MLIP like MACE-MP-0 [24].

- Generate Training Data (Optional but Recommended):

- Perform an atomic relaxation of your material using DFT. The steps in this trajectory provide your first dataset [24].

- For higher fidelity, generate additional configurations. Efficient strategies include using molecular dynamics (NPT ensemble) or applying random atomic displacements (0.01-0.05 Å) to a few supercells [9].

- Fine-Tune the MLIP: Use the generated DFT data to fine-tune the foundation model, creating a system-specific potential (e.g., MACE-MP-MOF0 for metal-organic frameworks) [14].

- Calculate Forces with MLIP: Use the fine-tuned MLIP to compute the forces for the displaced supercells. This step is orders of magnitude faster than DFT.

- Post-Processing: Follow steps 5-7 from Protocol 1 to obtain phonon dispersion, DOS, and thermodynamic properties.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision points and steps in these two key protocols, highlighting the role of step size optimization.

Quantitative Data for Comparison

The table below summarizes key phonon-derived properties for several materials, illustrating the typical outputs of these calculations.

| Material | Space Group | Key Phonon Feature | Thermodynamic Stability | Thermodynamic Property (Example) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMgO₃ | Pm-3m | Full phonon dispersion without imaginary modes | Dynamically stable (confirmed by AIMD) | N/A | [28] |

| KMgS₃ | Pm-3m | Full phonon dispersion without imaginary modes | Dynamically stable (confirmed by AIMD) | N/A | [28] |

| Silicon | Fd-3m | Standard phonon dispersion with characteristic acoustic/optical branches | Dynamically stable | N/A | [1] [27] |

| MOF-5 (with MACE-MP-MOF0) | Cubic | Accurate phonon DOS vs. DFT; corrects imaginary modes from base model | Dynamically stable after fine-tuning | Thermal expansion coefficient in agreement with experiment | [14] |

| UiO-66 (with MACE-MP-MOF0) | Cubic | Accurate phonon DOS vs. DFT | Dynamically stable | Bulk modulus in agreement with DFT/experiment | [14] |

Implementing Finite Displacement: A Step-by-Step Workflow and Advanced Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do I get unphysical negative frequencies in my phonon spectrum? Negative frequencies, or imaginary phonon modes, typically indicate one of two issues: the atomic geometry has not been fully relaxed to a minimum on the potential energy surface, or the step size used in the finite-displacement calculation is too large [30]. General accuracy issues, such as numerical integration or k-space sampling, can also be the cause [30]. Before phonon calculations, ensure your structure is optimally converged. If problems persist, consider reducing the displacement step or increasing the overall computational accuracy [30].

Q2: My geometry optimization does not converge. What can I do? First, check if the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) calculation converges, as this is a prerequisite [30]. If the SCF is stable but the geometry oscillates, the calculated forces (gradients) may be inaccurate. You can improve gradient accuracy by increasing the numerical quality, using a larger basis set, or tightening the SCF convergence criteria [31]. For difficult systems, using delocalized internal coordinates instead of Cartesian coordinates can lead to faster convergence [31]. Another strategy is to use a finite electronic temperature at the start of the optimization to aid convergence, automatically reducing it as the geometry approaches the minimum [30].

Q3: Is it acceptable to use a less tightly converged geometry for subsequent property calculations like UV-Vis spectra? For some properties, the error introduced by using a standard-converged geometry instead of a very-tightly-converged one may be negligible compared to other approximations in the method. For instance, errors from Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) for UV-Vis spectra are often larger than those from small geometry differences [32]. However, for frequency calculations, it is essential that the geometry is a true stationary point (minimum). Computing frequencies at a non-optimized geometry is meaningless and will produce invalid results [33].

Q4: How can Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) accelerate my phonon workflow? MLIPs can dramatically reduce the cost of phonon calculations. After being trained on a set of Density Functional Theory (DFT) data, they can predict atomic forces for new structures orders of magnitude faster than a full DFT calculation [9] [34]. This avoids the need for hundreds or thousands of expensive DFT self-consistent calculations normally required by the finite-displacement method [9] [35]. This speedup makes high-throughput screening of phonon properties feasible for large systems like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [14].

Q5: What is the difference between a "foundation" MLIP and a "defect-specific" MLIP? A foundation model (or universal potential) is trained on a vast and diverse dataset of materials, making it broadly applicable without retraining [9] [14]. However, its accuracy for specific, local properties like defect phonons can be limited [35]. A "one defect, one potential" strategy involves training a specialized MLIP on a limited set of DFT data for a single defect system. This approach often yields phonon properties with accuracy comparable to direct DFT at a fraction of the cost [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Geometry Optimization Fails to Converge

A converged geometry is the foundation for any reliable phonon calculation. Here is a systematic guide to address convergence failures.

Symptoms:

- The total energy oscillates without settling to a minimum value.

- The maximum force or energy change between steps fails to meet the convergence criteria within the allowed number of iterations.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|

| SCF Convergence | • Ensure the SCF cycle itself converges first. [30] • Use more conservative mixing (e.g., SCF\Mixing 0.05) [30] or the MultiSecant method. [30] • Tighten the SCF convergence criterion (e.g., to 1e-8) [31] and use ExactDensity for better accuracy. [31] |

| Force Accuracy | • Increase the NumericalQuality to "Good". [31] • Use a larger basis set (e.g., TZ2P). [31] • For slab systems, increase the number of radial points (RadialDefaults\NR). [30] |

| Optimization Process | • Switch from Cartesian to delocalized internal coordinates for faster convergence. [31] • Use automations to start with a loose convergence and high electronic temperature, gradually tightening them as the optimization proceeds. [30] • For systems with near-180-degree angles, restart the optimization from the latest geometry or constrain the angle. [31] |

This workflow summarizes the key steps and decision points for diagnosing geometry optimization issues:

Handling Imaginary Phonon Modes

The appearance of imaginary frequencies (reported as negative values in the output) in your phonon spectrum requires careful analysis.

Symptoms:

- The phonon density of states or dispersion curves show peaks or branches at negative frequencies.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Description & Solution |

|---|---|

| Non-equilibrium Geometry | Description: The most common cause. The structure used for the phonon calculation is not at a true energy minimum. [30] Solution: Return to the geometry optimization step. Ensure all forces on atoms are below a strict threshold (e.g., 1 meV/Å) and verify the structure is a minimum by confirming all vibrational frequencies are positive after a final frequency calculation. [33] |

| Insufficient Calculation Accuracy | Description: Numerical noise from low-quality integration grids, insufficient k-point sampling, or a poor basis set can manifest as imaginary modes. [30] Solution: Systematically increase the accuracy settings (NumericalQuality, k-space Quality, basis set size) and ensure force constants are well-converged with respect to these parameters. [31] [30] |

| Inappropriate Displacement Step | Description: A step size that is too large can lead to inaccuracies in the numerical calculation of force constants. [30] Solution: Reduce the displacement step used in the finite-displacement method (e.g., from 0.02 Å to 0.01 Å) and check for convergence. [35] |

The following chart provides a structured path to resolve imaginary phonon modes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and methodologies highlighted in modern research for streamlining the geometry-to-phonons workflow.

| Tool / Solution | Function in the Workflow | Key Context from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Replaces DFT for force evaluations in phonon calculations, offering massive speedups. [9] [34] | Foundation models (e.g., MACE-MP-0) are general-purpose but may lack target accuracy. Fine-tuned or defect-specific models offer DFT-level accuracy for complex systems like MOFs and color centers. [35] [14] |

| MACE (MPNN Architecture) | A state-of-the-art MLIP framework used for high-throughput phonon calculations. [9] | Demonstrated accurate prediction of full harmonic phonon spectra and vibrational free energies across a diverse set of materials. [9] |

| "One Defect, One Potential" Strategy | A specialized approach where an MLIP is trained for a single defect system. [35] | Achieves phonon accuracy comparable to DFT with minimal training data, enabling high-fidelity calculation of Huang-Rhys factors and nonradiative capture rates in large supercells. [35] |

| Finite-Displacement Method | The standard technique for calculating phonons by displacing atoms and calculating forces. [9] | Research focuses on optimizing the number and type of displacements. Using randomly perturbed supercells for MLIP training can reduce the number of required DFT calculations. [9] |

| Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (QHA) | Extends the harmonic model to approximate thermodynamic properties at finite temperatures. [14] | Used with MLIPs to efficiently compute temperature-dependent properties like thermal expansion in MOFs, revealing behaviors such as negative thermal expansion. [14] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Phonon Calculations with Universal MLIPs

This methodology leverages pre-trained universal machine learning potentials to accelerate phonon calculations across a wide range of materials. [9]

- Dataset Generation: For each material, generate a small number of supercell structures (e.g., ~6). In each supercell, randomly perturb all atoms with displacements typically ranging from 0.01 Å to 0.05 Å. [9]

- DFT Reference Calculation: Perform a single DFT self-consistent calculation for each of these perturbed supercells to obtain the reference total energies and interatomic forces. This constitutes the training dataset. [9]

- MLIP Training: Train a universal MLIP model (e.g., MACE) on the aggregated dataset from the previous step. The model learns the mapping between atomic structures and the potential energy surface. [9]

- Phonon Calculation: Use the trained MLIP within a phonon package (e.g., Phonopy). The MLIP instantly provides forces for the many displaced structures required by the finite-displacement method, bypassing costly DFT calculations. [9]

- Validation: The results are systematically improvable by increasing the number of training structures per material. [9]

Protocol 2: Accurate Defect Phonons with the "One Defect, One Potential" Strategy

This protocol is designed for achieving high accuracy for specific defect systems, crucial for properties like photoluminescence spectra. [35]

- System Selection: Identify the defect system of interest (e.g., a carbon substitution in GaN).

- Training Data Generation:

- Start from the DFT-relaxed defect structure in a large supercell.

- Generate training structures by randomly displacing each atom within a sphere of a small radius (e.g., 0.04 Å). [35]

- Use DFT to compute the energy and atomic forces for these perturbed structures. A small set of ~40 configurations may be sufficient. [35]

- Specialized MLIP Training: Train a defect-specific MLIP (e.g., using the Allegro or NequIP framework) on this limited, targeted dataset. The local descriptor of these models enhances data efficiency. [35]

- Phonon and Property Calculation: Use the specialized MLIP to perform the phonon calculation. The predicted phonon frequencies and eigenvectors can then be used to compute Huang-Rhys factors and photoluminescence lineshapes with high accuracy. [35]

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My phonon calculation produces imaginary frequencies (negative values) for what should be a stable crystal structure. What is the most likely cause and how can I resolve it?

A1: The most common cause is an excessively large displacement magnitude. A large step size drives the atoms too far from their equilibrium positions, moving beyond the harmonic potential well where the forces are no longer linear. This breaks the fundamental assumption of the finite displacement method.

- Solution: Systematically reduce the displacement magnitude. Begin a convergence test using a range of values, starting from 0.005 Å up to 0.04 Å, and monitor the phonon frequencies, especially the lowest optical and acoustic modes. The optimal value is the smallest one that produces stable, converged phonons without imaginary frequencies.

Q2: How do I know if my chosen displacement magnitude is too small?

A2: A displacement that is too small can lead to numerical noise. The finite difference approximation for the force constants becomes unstable because the force differences between the displaced and equilibrium structures are on the same order of magnitude as the numerical error in the DFT force calculations.

- Indicators: Phonon frequencies that fail to converge, exhibit significant scatter between similar modes, or change erratically when the displacement is slightly altered.

- Solution: Increase the displacement magnitude in small increments (e.g., 0.005 Å) until the phonon spectrum becomes stable and reproducible. Ensure your DFT calculations are highly converged (tight settings for energy, force, and k-points) to minimize intrinsic numerical error.

Q3: Does the optimal displacement magnitude depend on the chemical species in my system?

A3: Yes, significantly. Heavier atoms and softer chemical bonds (e.g., in organic crystals, molecular systems) generally require a larger displacement magnitude compared to lighter atoms and stiffer bonds (e.g., in covalent ceramics like diamond).

- Guideline:

- Stiff, Covalent Solids (C, Si, SiC): 0.01 - 0.02 Å

- Ionic Crystals (NaCl, MgO): 0.02 - 0.03 Å

- Metals (Al, Fe): 0.02 - 0.035 Å

- Soft/Organic/Molecular Crystals: 0.03 - 0.05 Å A system-specific convergence test is always recommended.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Recommended Displacement Magnitude Ranges by Material Type

| Material Type | Common Displacement Range (Å) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Solids | 0.010 - 0.020 | Very stiff bonds, highly harmonic potential. |

| Ionic Crystals | 0.020 - 0.030 | Moderate bond stiffness, stable ionic lattice. |

| Metals | 0.020 - 0.035 | Delocalized bonding, often requires slightly larger steps. |

| Soft/Organic Crystals | 0.030 - 0.050 | Weak van der Waals forces, anharmonic potentials. |

Table 2: Example Convergence Test for a Hypothetical Pharmaceutical Compound (API Form I)

| Displacement (Å) | Lowest Phonon Frequency (cm⁻¹) | Presence of Imaginary Frequencies? | Computational Cost (Relative CPU hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.005 | -15.2 | Yes (Significant) | 1.0x |

| 0.010 | -5.1 | Yes (Slight) | 1.0x |

| 0.025 | 12.8 | No | 1.0x |

| 0.040 | 12.5 | No | 1.0x |

| 0.060 | 11.9 | No | 1.0x |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Convergence Test for Displacement Magnitude

- Structure Relaxation: Fully relax the crystal structure (ionic positions, cell vectors) using DFT to obtain the true ground-state geometry. Ensure forces are converged to a tight threshold (e.g., < 0.001 eV/Å).

- Supercell Construction: Build a supercell of sufficient size to capture the relevant phonon interactions (e.g., a 2x2x2 or 3x3x3 expansion of the primitive cell).

- Displacement Series: Generate sets of displaced supercells for a series of displacement magnitudes (e.g., 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05 Å).

- Force Calculation: For each set, perform a single-point DFT calculation on the equilibrium and all displaced supercells. Use highly accurate settings to minimize numerical noise in the forces.

- Post-Processing: Calculate the force constants and subsequently the phonon dispersion and density of states for each displacement value.

- Analysis: Plot the key phonon frequencies (e.g., the highest optical mode and the lowest acoustic mode at the Brillouin zone boundary) as a function of displacement magnitude. The value where these frequencies stabilize is the optimal displacement.

Protocol 2: Validating Stability with Phonon DOS

- Calculation: After determining a candidate displacement magnitude from Protocol 1, perform a full phonon calculation.

- Inspection: Examine the phonon Density of States (DOS) plot.

- Interpretation: A stable structure will have a DOS that begins at or very near zero frequency. Any significant density of states in the negative frequency region indicates structural instability or a sub-optimal displacement parameter.

Mandatory Visualization

Phonon Step Size Optimization

Displacement Magnitude Effects

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Finite Displacement Phonon Calculations

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| DFT Software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ABINIT) | Performs the underlying electronic structure calculations to compute the forces on atoms in the displaced supercells. |

| Phonopy / Alamode / Similar Code | Post-processing tool that manages supercell generation, constructs the force constant matrix from DFT outputs, and calculates the phonon properties. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for handling the computationally intensive task of running dozens to hundreds of DFT calculations for the displaced structures. |

| Converged DFT Pseudopotential/PAW | Provides an accurate description of the core-valence electron interaction, critical for calculating precise forces. |

| Tight Force Convergence Parameters | Ensures that the numerical forces used in the finite difference method are calculated with high accuracy, reducing noise. |

| Crystal Structure Visualizer (VESTA) | Aids in verifying supercell constructions and the nature of atomic displacements. |

The Role of Supercell Size and Its Interplay with Step Size

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary consequence of choosing a supercell that is too small? A supercell that is too small cannot capture the long-range interactions between atomic displacements. The force-constant matrix, which measures how the displacement of one atom affects the force on another, must be allowed to decay to zero. If the supercell is too small, these interactions will "wrap around" and interact with their own periodic images, a problem known as aliasing, which leads to inaccurate phonon frequencies [36]. A general rule of thumb is that the supercell should be large enough that its minimum dimension is at least twice the distance at which the force constants decay to zero [36].

2. How does the finite-displacement step size (POTIM) interact with supercell size? The step size (POTIM) and supercell size are convergence parameters that are largely independent but must both be addressed for accurate results. The step size controls the numerical accuracy of the finite-difference calculation for the force constants within your chosen supercell. A step that is too large introduces anharmonic errors, while one that is too small may lead to numerical noise from finite precision [15]. The supercell size, on the other hand, controls the physical accuracy of the range of atomic interactions included in the calculation. You should first converge your supercell size to capture all relevant force constants, and then ensure your step size is appropriate for that supercell [15].

3. My phonon calculation shows imaginary frequencies. Could this be related to supercell size or step size? Yes, both can be contributing factors. Imaginary frequencies often indicate a structural instability, but they can also be an artifact of poor convergence.

- Supercell Size: An unconverged supercell size is a common source of unphysical imaginary frequencies, as it fails to correctly describe the long-range forces that stabilize the lattice [36].

- Step Size: An excessively large step size (POTIM) can probe anharmonic regions of the potential energy surface, leading to incorrect force constants and spurious instabilities [15]. Before investigating complex structural instabilities, it is crucial to verify that these numerical parameters are fully converged.

4. Are there methods to reduce the computational cost of using large supercells? Yes, two effective strategies are:

- Nondiagonal Supercells: Traditional "diagonal" supercells scale the primitive cell by factors ( N1, N2, N3 ), resulting in a supercell containing ( N1 \times N2 \times N3 ) primitive cells. The nondiagonal supercell method uses linear combinations of the primitive lattice vectors to create a mathematically equivalent supercell for a given q-point grid, but which can be as small as the least common multiple of ( N1, N2, N_3 ). This can reduce the number of atoms from ( N^3 ) to ( N ), offering a dramatic reduction in computational cost [36] [37].

- Symmetry Reduction: Using

IBRION=6in VASP (instead ofIBRION=5) tells the code to use symmetry to only displace symmetry-inequivalent atoms, and then generate the full force-constant matrix using symmetry operations. This can significantly reduce the number of individual displacement calculations required [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Achieving Convergence

Symptom: Phonon frequencies do not converge, or imaginary frequencies persist.

Step 1: Converge Supercell Size The most critical step is to systematically increase the supercell size until the phonon frequencies, especially at the Γ-point, no longer change significantly.

Protocol:

- Start with a moderate supercell (e.g., ( 2\times2\times2 ) or ( 3\times3\times3 ) of the primitive cell).

- Calculate the phonon frequencies at the Γ-point.

- Increase the supercell size in one or more dimensions (e.g., to ( 4\times4\times4 )) and repeat the calculation.

- Compare the optical phonon frequencies between calculations. Convergence is typically achieved when the frequency change is less than your desired tolerance (e.g., 1-2 cm⁻¹).

Data Presentation: The table below summarizes example findings from the literature on how supercell size affects key phonon modes in different materials.

| Material (Primitive Cell) | Supercell Size | Key Phonon Frequency | Observation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diamond (2 atoms) | ( 2\times2\times2 ) | Not Converged | Severe aliasing; spurious imaginary frequencies may appear. | [36] |

| Diamond (2 atoms) | ( 4\times4\times4 ) | Converged ~1200 cm⁻¹ | Requires a larger supercell due to small primitive cell. | [36] |

| Silicon (2 atoms) | ( 3\times3\times3 ) | Converged | A ( 12\times12\times12 ) k-mesh in the primitive cell is equivalent to a ( 6\times6\times6 ) mesh in a ( 2\times2\times2 ) supercell. | [15] |

| (\ce{In2O3}) (40 atoms) | ( 2\times2\times2 ) | Likely Converged | Larger primitive cell naturally provides more spatial sampling. | [36] |

Step 2: Optimize the Finite-Displacement Step Size Once the supercell is converged, verify that your step size is appropriate.

Protocol:

- With your converged supercell, perform phonon calculations using different values of

POTIM(e.g., 0.01 Å, 0.015 Å, 0.02 Å). - Monitor the change in the calculated force constants or the resulting phonon frequencies.

- VASP's default of

POTIM = 0.015 Åis a robust starting point for many systems [15]. UsingNFREE=2(central differences) is generally recommended overNFREE=1[15].

- With your converged supercell, perform phonon calculations using different values of

Data Presentation: The following table outlines the standard step size parameters in VASP.

| INCAR Tag | Recommended Value | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|

POTIM |

0.015 Å (default) | Determines the displacement step size. | [15] |

NFREE |

2 | Uses central differences (±POTIM), providing higher numerical accuracy than one-sided displacements. | [15] |

IBRION |

6 | Computes force constants using finite differences, but uses symmetry to minimize the number of displacements. | [15] |

Step 3: Ensure Overall Calculation Quality Phonon calculations require highly accurate forces. Supercell and step size convergence can be undermined by other numerical settings.

- Checklist:

- Forces: Use

PREC = Accurateand ensure electronic convergence with a tightEDIFF(e.g.,1e-8or lower) [15] [38]. - k-points: When you increase the supercell size, the k-point mesh for the supercell calculation should be reduced to maintain a k-point density equivalent to that of the primitive cell [15] [38].

- Structure: The starting structure must be fully relaxed until the forces on all atoms are negligible (e.g., below 1 meV/Å) [39].

- Forces: Use

Workflow for troubleshooting phonon convergence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists the key "computational reagents" for a robust finite-displacement phonon study.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Converged Supercell | The core reagent. Ensures all interatomic force constants are captured without self-interaction, forming the foundation for accurate phonon dispersion. |

| Optimized Step Size (POTIM) | Critical for numerical precision. Controls the finite-difference accuracy when calculating the second derivative of the energy (force constants). |

| High-Precision Force Calculator | A well-converged DFT calculation with accurate forces (PREC=Accurate, tight EDIFF) is the source of all data. |

| Symmetry Reduction (IBRION=6) | A computational catalyst that drastically reduces the number of required displacement calculations by exploiting crystal symmetry [15]. |

| k-point Mapping | Maintaining a consistent k-point density between primitive and supercell calculations ensures comparable electronic sampling and avoids Pulay stress-related errors [15] [38]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use random perturbations of all atoms instead of the traditional single-atom displacement method?

The traditional finite-displacement method perturbs one atom at a time with a small displacement (typically 0.01 Å). In contrast, the advanced sampling approach involves generating a subset of supercell structures where all atoms are randomly perturbed simultaneously, with displacements ranging from 0.01 to 0.05 Å [40]. This method gathers numerous non-zero interatomic forces with relatively large magnitudes and richer information from each supercell calculation. It leverages a data-driven, machine-learning model trained on a diverse dataset to compensate for the reduced number of supercells, maintaining high accuracy while significantly improving computational efficiency [40].

Q2: What is a good starting number of random perturbation configurations to use per material?

A preliminary analysis has found that using only six randomly perturbed structures per material can achieve a good balance between computational efficiency and prediction accuracy for harmonic phonon properties [40]. The results are systematically improvable by increasing the number of training structures, allowing you to start with this number and scale up if higher precision is required.

Q3: My phonon calculation shows acoustic modes at Γ-point that are not zero. Is this an error?

Not necessarily. The Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) is never exactly verified in practice because the system is never perfectly translationally invariant. The frequency of acoustic modes at the gamma point (Γ) is typically less than 10 cm⁻¹, but can sometimes be higher [41]. You can verify your results by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix while imposing the ASR (e.g., using a tool like dynmat.x). If the acoustic mode frequency then becomes much smaller (e.g., <1 cm⁻¹) and other modes remain virtually unchanged, you can trust your results [41].

Q4: I am getting a "Input forces are not enough to calculate force constants" error. What should I do?

This error in phonon codes (like Phonopy) often arises from a symmetry-related issue [42]. The code uses symmetry to reduce the number of force constants it needs to calculate, and if the symmetry finder fails, it may not request enough displacements. Try the following:

- Lower the symmetry tolerance: Use a command like

phonopy --tolerance=1e-4 -p band.conf[42]. - Ensure structure consistency: Verify that the crystal structure used for the phonon calculation matches the one used for the force calculations [42].

- Check FORCE_SETS file: Confirm that your

FORCE_SETSfile is calculated correctly and without errors [42].

Q5: Can I run vibration calculations at q-points other than the Gamma point?

Yes. The dynamical matrix at arbitrary q-vectors is obtained by Fourier transforming the real-space force constants [7]. After you have calculated the force constants in real space (which is done using supercells in real space), you can compute the phonon band structure and frequencies along any path in the Brillouin zone you define [7]. Ensure your initial supercell is large enough to capture the necessary interactions for an accurate Fourier transform [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Severe Violation of the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) or "Lousy" Phonons

Problem: The phonon calculation yields significant violations of the ASR (acoustic modes at Γ far from zero), unphysical "negative" frequencies (imaginary modes), or clearly wrong symmetries [41].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check convergence parameters: Ensure your SCF convergence threshold (

conv_thrinpw.x) and phonon calculation threshold (tr2_phinph.x) are sufficiently small. Try reducing them [41]. - Verify computational parameters:

- The plane-wave cutoff energy for wavefunctions (

ecutwfc). - For ultrasoft pseudopotentials (USPP) or PAW, the cutoff for the charge density (

ecutrho), which is typically 4-8 timesecutwfc[41]. - The k-point grid for sampling the Brillouin zone, especially for metallic systems where convergence can be slow [41].

- The plane-wave cutoff energy for wavefunctions (

- Confirm structural stability: A negative frequency can signal a genuine mechanical instability of your chosen structure. Check that the structure is reasonable and fully relaxed [41].

- Inspect atomic masses: Verify that the correct atomic masses are used in the input, as wrong masses will lead to incorrect frequencies [41].

- For metallic systems: Convergence can be very slow. Ensure a dense k-point grid and check the smearing parameters [41].

Solution: Systematically tighten your convergence parameters (cutoff energies, k-points, SCF thresholds) and reconfirm the stability of your input structure.

Issue 2: Phonon Band Structure Only Shows Gamma Point

Problem: When calculating a phonon band structure, the output only displays frequencies at the Gamma point, not along the entire path [43].

Cause: This is typically caused by using a supercell that is too small (e.g., 1x1x1). The small supercell only contains information for the Gamma point in reciprocal space [43].

Solution: Increase the supercell size (the N value in supercell=(N, N, N)). A larger supercell samples a finer grid in reciprocal space, allowing you to build a phonon band structure along a defined path [43].

Issue 3: Symmetry-Related Errors During Calculation

Problem: Errors such as symmetry operation is non orthogonal, Wrong representation, or Wrong degeneracy [41].

Cause: These are almost invariably due to atomic positions that are close to, but not exactly at, high-symmetry positions. The code's symmetry detection routine fails with a small tolerance [41].

Solution:

- Use the correct Bravais lattice: In your self-consistent calculation, set the

ibravparameter to the correct value for your crystal system instead of usingibrav=0[41]. - Use Wyckoff positions: If known, use standard Wyckoff positions to generate the atomic coordinates, ensuring exact symmetry [41].

Experimental Protocol: Advanced Random Perturbation Method

This protocol details the methodology for generating a training dataset for machine-learning interatomic potentials, which can subsequently be used for highly efficient and accurate phonon calculations [40].

Objective: To significantly reduce the number of required supercell DFT calculations while maintaining high accuracy in predicting harmonic phonon properties.

Materials and Computational Reagents:

- Structures: A comprehensive set of crystal structures (e.g., 2,738 structures with 77 elements was used in the referenced study [40]).

- DFT Code: A software package for performing high-fidelity Density Functional Theory calculations (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP).

- Supercell Generation Tool: A tool to build supercells from primitive cells (e.g., ASE, Phonopy, SPGLIB).

- Machine Learning Potential Framework: A code for training and using MLIPs (e.g., MACE model as used in the reference study [40]).

Methodology:

- Supercell Construction: For each material in your dataset, construct a suitably large supercell to capture the relevant atomic interactions.

- Random Atomic Perturbation: Generate a small number of supercell configurations (as few as six per material) where all atoms are randomly and independently displaced. The displacement magnitude should be in the range of 0.01 to 0.05 Å [40].

- DFT Force Calculations: Perform a single-point DFT calculation for each of these randomly perturbed supercells to obtain the quantum-mechanical interatomic forces acting on every atom.

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a dataset where the input is the atomic structure of the perturbed supercell and the target is the set of interatomic forces from DFT. The referenced study created a dataset of 15,670 supercell structures in this manner [40].

- Machine Learning Potential Training: Train a state-of-the-art machine learning interatomic potential (like MACE) on this curated dataset. The model learns the mapping between atomic structure and forces.

- Phonon Property Prediction: Use the trained MLIP to compute the force constants and subsequent phonon properties (dispersion, density of states, free energy) for new materials of interest. This bypasses the need for explicit, costly DFT supercell calculations for each new material.

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the advanced sampling method.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential computational tools and their functions in implementing the advanced phonon sampling protocol.

| Item Name | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| DFT Software (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP) | Performs high-fidelity electronic structure calculations to obtain the reference interatomic forces for randomly perturbed supercells [40] [41]. |

| MLIP Model (e.g., MACE) | A machine learning model that learns the potential energy surface from the dataset; used to predict forces and calculate phonons without further DFT calls [40]. |