Negative Phonon Frequencies: A Definitive Guide to Diagnosing Material Instability

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of negative phonon frequencies in phonon spectra, a critical indicator of material dynamical instability.

Negative Phonon Frequencies: A Definitive Guide to Diagnosing Material Instability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of negative phonon frequencies in phonon spectra, a critical indicator of material dynamical instability. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the fundamental physics connecting imaginary frequencies to potential energy surface curvature and structural stability. The content details modern computational methodologies, including density functional theory and machine learning potentials, for accurate phonon calculation. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls, such as imaginary modes in stable materials, offering optimization strategies. Finally, we present validation protocols and comparative case studies from recent literature, establishing a robust framework for interpreting phonon spectra to predict material behavior and guide the design of novel compounds in fields from solid-state electrolytes to drug development.

The Physics of Imaginary Frequencies: Unraveling the Link to Dynamical Instability

Negative phonon frequencies, more accurately described as imaginary frequencies, represent a critical diagnostic tool in computational materials science. This whitepaper delineates the mathematical foundation of these frequencies as eigenvalues of the dynamical matrix and explicates their physical interpretation as signatures of dynamical instabilities within crystal structures. Framed within material stability research, this technical guide details methodologies for detecting these instabilities and summarizes their profound implications for predicting structural phase transitions and designing functional materials. The presence of such frequencies indicates that the assumed crystal structure is not at a minimum on the potential energy surface and may undergo a distortion to a more stable configuration, such as a charge density wave phase [1].

Phonons are quantized collective excitations representing the vibrational modes of a crystal lattice. They are pivotal in determining numerous material properties, including thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, and structural stability [2]. In the harmonic approximation, the phonon frequencies (ω) for a given wave vector are obtained by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix, which is derived from the force constant matrix [3] [4].

The force constants (Φ) themselves are defined as the second derivatives of the total potential energy (V) with respect to atomic displacements:

Φαβ(jl, j'l') = ∂²V / ∂rα(jl) ∂rβ(j'l')

where j, j' are atom indices, l, l' are unit cell indices, and α, β are Cartesian coordinates [4]. The dynamical matrix Dαβ(jj', q) is then constructed as a Fourier transform of these force constants [4]. The eigenvalues of this dynamical matrix are ω²ₙ, where n is the mode index. The physical phonon frequencies are the square roots of these eigenvalues [3].

A structure is considered dynamically stable if all eigenvalues ω²ₙ are non-negative for all wave vectors in the Brillouin zone, resulting in real, positive phonon frequencies. Conversely, the appearance of any negative eigenvalue (ω²ₙ < 0) signifies dynamical instability. The corresponding phonon frequency ωₙ = i√|ω²ₙ| is an imaginary number, often reported as a "negative" frequency in computational outputs as a convention [3] [1]. This imaginary frequency is not a physical vibration that can be directly measured but is a mathematical indicator that the crystal structure is at a saddle point, not a minimum, on the potential energy surface [3] [1].

Mathematical Origin and Physical Interpretation

The Link to the Potential Energy Surface

The mathematical origin of imaginary phonon frequencies is intrinsically linked to the curvature of the potential energy surface (PES) around the atomic configuration in question.

- Positive

ω²(Real Frequency): Indicates a positive curvature of the PES. Displacing atoms along the corresponding eigenvector increases the system's energy, confirming a local minimum [3]. - Negative

ω²(Imaginary Frequency): Signifies a negative curvature of the PES. Displacing atoms along the associated eigenvector lowers the total energy, indicating that the current structure is unstable and will spontaneously distort to a lower-energy configuration [3].

This concept is powerfully illustrated by the phase transition in monolayer MoS₂. The high-symmetry T-phase exhibits an imaginary frequency at the Brillouin zone boundary. Displacing atoms along this unstable mode and relaxing the structure leads to the stable, lower-symmetry T'-phase, which has a real, positive-definite phonon spectrum [5].

Conceptual Workflow: From Calculation to Physical Meaning

The following diagram outlines the logical pathway from a phonon calculation to the physical interpretation of its results, particularly when imaginary frequencies are present.

Methodologies for Detecting and Analyzing Instabilities

Computational Protocols and Workflows

Robust detection of imaginary phonon modes requires careful computational planning. The following workflow details a standard protocol, such as the Center and Boundary Phonon (CBP) method used in high-throughput screening [5].

The CBP protocol is a efficient stability test that evaluates the Hessian matrix of a 2x2 supercell, which corresponds to calculating phonons at the center and boundary of the Brillouin zone [5]. Its reliability has been validated against full phonon band structure calculations, with false positives (stable in a 2x2 cell but unstable in a larger cell) being relatively rare [5].

Quantitative Observations of Imaginary Frequencies

Imaginary frequencies are not merely theoretical constructs but have observable consequences in material behavior.

Table 1: Experimental Signatures Linked to Imaginary Phonon Modes

| Material System | Unstable Mode Location | Experimental Consequence | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolayer NbSe₂ | Not Specified | Formation of a Charge Density Wave (CDW) phase. | [1] |

| Monolayer MoS₂ | M-point (BZ boundary) | Phase transition from T-phase to T'-phase. | [5] |

| Cs₂SnI₆ | Multiple wavevectors | Cubic to monoclinic phase transition at low temperature; high anharmonicity. | [6] |

| General Principle | Any wavevector | Melting or suppression of CDW order as a signature of the underlying instability. | [1] |

It is crucial to note that the imaginary mode itself is a signature of the instability in the high-symmetry phase. Experiments typically measure the real, positive frequencies of the stabilized, lower-symmetry structure into which the system distorts [1]. The timescale of this phase transition can be used to quantify the strength of the imaginary mode indirectly [1].

A range of software tools and computational resources are essential for performing phonon calculations and analyzing the results.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Phonon and Stability Research

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Relevance to Imaginary Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes (e.g., VASP) | Electronic structure calculation to determine forces and total energy. | Provides the fundamental quantum mechanical data for force constant calculations. | [7] |

| PHONOPY | A widely used package for calculating phonon spectra and force constants. | Standard tool for performing the finite displacement method to uncover unstable modes. | [4] |

| PARPHOM | A massively parallel phonon calculator for large systems like moiré superlattices. | Enables phonon calculations in complex systems with thousands of atoms where instabilities may arise. | [4] |

| PYSED | Python package for extracting phonon dispersion and lifetime from molecular dynamics. | Uses spectral energy density to analyze phonon behavior, including anharmonic effects. | [8] |

| Machine Learning Potentials (NEP) | High-accuracy, computationally efficient force fields. | Allows large-scale and long-timescale simulations to study instability dynamics. | [8] |

| C2DB Database | Repository of computed properties for 2D materials. | Uses the CBP protocol to classify dynamical stability, identifying unstable materials. | [5] |

Implications for Material Stability and Property Design

The detection and analysis of imaginary phonon frequencies have far-reaching implications for materials research and drug development.

In materials science, imaginary frequencies are a powerful predictor of structural phase transitions, such as the emergence of charge density waves (CDWs) [1]. For instance, in materials like monolayer NbSe₂, the theoretical prediction of imaginary frequencies precedes the experimental observation of a CDW state [1]. Furthermore, understanding these instabilities is key to engineering thermal properties. The deliberate introduction of disorder, nanostructures, and interfaces can scatter phonons and significantly reduce thermal conductivity, a vital strategy for improving thermoelectric materials [9].

For drug development professionals, the principles of lattice stability extend to molecular crystals. While the term "phonon" is used for periodic crystals, the same concepts of vibrational stability apply. A pharmaceutical crystal with imaginary frequencies in its lattice vibrations would indicate a polymorphic instability, suggesting the crystal could transition to a more stable form. This has direct consequences for drug shelf life, bioavailability, and regulatory approval. Ensuring the dynamical stability of a chosen polymorph is therefore as critical as confirming its thermodynamic stability.

Advanced experimental techniques, such as vibrational electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) in an electron microscope, now allow for nanoscale mapping of phonon modes [9]. While this technique measures real frequencies in the stabilized structure, it can directly probe the phonon renormalization and localized modes that result from structural instabilities engineered at interfaces [9].

Imaginary phonon frequencies are a precise mathematical outcome of lattice dynamics calculations that carry profound physical meaning. They are a definitive signature of dynamical instability, indicating that a crystal structure is not a true ground state and will reconfigure itself. The methodologies for detecting these instabilities, from the CBP protocol to full phonon band calculations, are essential components of the modern materials research toolkit. As computational and experimental techniques advance, the ability to not only predict but also to strategically utilize these instabilities will continue to drive innovations in the design of functional materials, from quantum materials to pharmaceuticals.

This technical guide explores the fundamental connection between phonon spectra and the potential energy surface (PES) of materials through the Hessian matrix framework. The presence of imaginary frequencies (negative eigenvalues) in phonon calculations serves as a critical indicator of dynamical instability, revealing that a material's structure does not reside at a local minimum on the PES. Within the harmonic approximation, the Hessian matrix—the second derivative of energy with respect to atomic coordinates—provides the mathematical foundation for understanding these vibrational dynamics. This whitepaper details computational methodologies for stability analysis, presents quantitative data from recent research, and discusses emerging machine learning approaches that are revolutionizing the field of materials stability research.

The vibrational dynamics of atoms in molecules and crystalline solids are governed by the topography of the potential energy surface (PES). Within the harmonic approximation, the relationship between phonons and the PES is quantified through the Hessian matrix, which encodes the curvature of the energy landscape around a given atomic configuration [10]. Mathematically, the Hessian matrix elements are defined as ( H{ij} = \frac{\partial^2E}{\partial{}Ri\partial{}Rj} ), where ( Ri ) and ( R_j ) represent atomic coordinates [11].

The diagonalization of the mass-weighted Hessian produces eigenvalues corresponding to vibrational frequencies and eigenvectors representing normal modes of vibration [11] [12]. When all eigenvalues are positive, the structure resides at a local minimum on the PES and is considered dynamically stable. The emergence of imaginary frequencies (mathematically represented as negative eigenvalues of the Hessian) indicates that the current atomic configuration corresponds to a saddle point rather than a minimum, revealing dynamic instability [13]. This fundamental connection makes phonon spectra an essential computational probe for predicting material stability and understanding structural transformations at the atomic scale.

Theoretical Foundations: Hessian Matrix and Normal Modes

The Harmonic Approximation

Within the harmonic model, the potential energy ( V ) of a system near equilibrium can be approximated by a Taylor series expansion truncated at the second-order term [12]:

[V (gk) = V(0) + \dfrac{1}{2} \sum{j,k} qj H{j,k} q_k]

where ( V(0) ) represents the energy at the equilibrium geometry, ( qj ) are the atomic displacement coordinates, and ( H{j,k} ) are the elements of the Hessian matrix [12]. This parabolic approximation of the PES enables the description of atomic vibrations as simple harmonic oscillators.

The classical equations of motion derived from this potential energy function lead to an eigenvalue equation:

[\omega^2 xj = \sumk H'{j,k} xk]

where ( H'{j,k} = \dfrac{H{j,k}}{ \sqrt{mjmk} } ) represents the mass-weighted Hessian matrix elements, and ( \omega^2 ) are the eigenvalues whose square roots give the normal mode vibrational frequencies [12].

From Molecular Vibrations to Phonons

For isolated molecules, the solutions to these equations yield discrete normal modes of vibration [10]. In crystalline solids, these vibrations extend through the periodic lattice, forming continuous bands of vibrational states known as phonons with specific dispersion relationships throughout the Brillouin zone [10]. The Hessian framework thus provides a unified mathematical approach for analyzing vibrational spectra across different material systems, from molecular clusters to extended crystals.

Table: Key Mathematical Quantities in Vibrational Analysis

| Quantity | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hessian Matrix | ( H{j,k} = \frac{\partial^2E}{\partial{}Rj\partial{}R_k} ) | Curvature of potential energy surface |

| Mass-Weighted Hessian | ( H'{j,k} = \frac{H{j,k}}{\sqrt{mjmk}} ) | Enables separation of mass and force constant effects |

| Harmonic Potential | ( V = \frac{1}{2} \sum{j,k} qj H{j,k} qk ) | Parabolic approximation near equilibrium geometry |

| Eigenvalue Equation | ( \omega^2 xj = \sumk H'{j,k} xk ) | Provides squares of vibrational frequencies as eigenvalues |

Negative Frequencies and Material Stability

The Significance of Imaginary Frequencies

In vibrational analysis, an imaginary frequency arises when the solution of the harmonic oscillator equation yields a negative value for ( \omega^2 ), making ( \omega ) itself an imaginary number [13] [14]. This mathematical result has profound physical implications: it indicates that the current atomic configuration corresponds to a saddle point on the PES rather than a minimum [13].

The connection to the Hessian matrix is direct: the eigenvalues of the Hessian represent the force constants along normal mode directions. A negative eigenvalue corresponds to a direction in which the energy decreases rather than increases with displacement, signifying an unstable configuration [13]. This relationship provides the theoretical foundation for using phonon calculations as a probe of the PES topography.

Stability Classification via Phonon Spectra

The number and magnitude of imaginary frequencies enable classification of stationary points on the PES:

- Local Minimum: All Hessian eigenvalues are positive (no imaginary frequencies) [13]

- Transition State: Exactly one negative Hessian eigenvalue (one imaginary frequency) [15]

- Higher-Order Saddle Point: Multiple negative Hessian eigenvalues (multiple imaginary frequencies)

This classification scheme makes vibrational frequency analysis an essential tool for verifying that computationally optimized structures represent true local minima rather than saddle points [15] [13]. In the context of materials research, it provides a critical test for dynamic stability – whether a crystal structure will spontaneously distort due to vibrational instabilities at 0K [13].

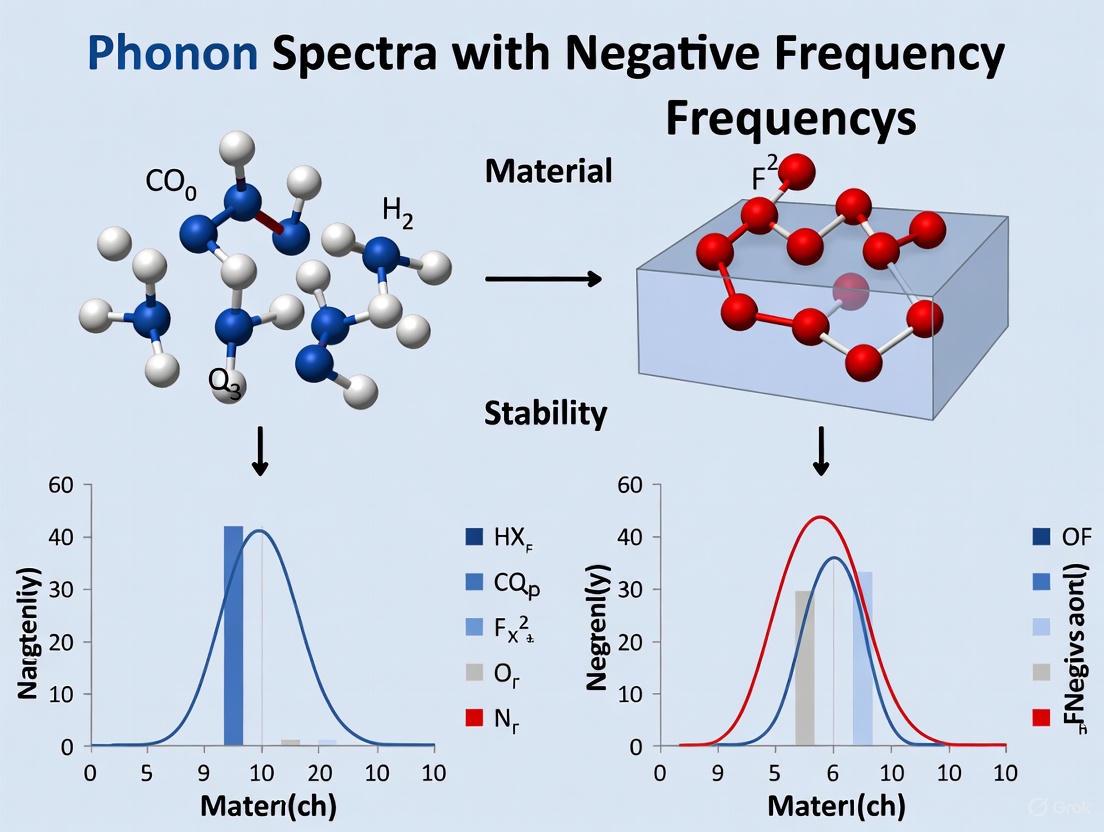

Diagram Title: Phonon Spectrum Stability Classification Pathway

Computational Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Stability Assessment

The established computational workflow for evaluating dynamical stability through phonon analysis involves sequential steps:

Geometry Optimization: The atomic structure must first be relaxed to a stationary point on the PES where the interatomic forces are minimized [15]. This optimization should be performed with tight convergence criteria to ensure forces and stresses are sufficiently small.

Hessian Matrix Calculation: The second derivative matrix is computed either analytically (for some electronic structure methods) or numerically through finite differences of energies or forces [11]. Numerical calculation requires ( 6N ) single-point calculations for ( N ) atoms, making it computationally expensive for large systems [11].

Phonon Spectrum Generation: Diagonalization of the mass-weighted Hessian yields vibrational frequencies and normal modes. The resulting spectrum should be carefully examined for imaginary frequencies.

Structure Validation: The absence of imaginary frequencies confirms the structure is at a local minimum, while their presence indicates need for further optimization or exploration of symmetry-broken structures [13].

Advanced Computational Approaches

For large systems where full Hessian calculation is prohibitively expensive, several advanced methods have been developed:

Mobile Block Hessian (MBH): This approach treats parts of the system as rigid blocks, significantly reducing the number of degrees of freedom [11]. MBH is particularly useful for analyzing vibrations in partially optimized structures or large systems where only specific regions are of interest.

Mode Selective Methods: Techniques like mode scanning, mode refinement, and mode tracking enable targeted calculation of specific vibrational modes without computing the full spectrum [11]. The ReScanModes keyword in AMS software allows selective re-calculation of imaginary modes to identify spurious instabilities [11].

Center and Boundary Phonon (CBP) Protocol: For 2D materials, this efficient method evaluates phonons only at the center and specific high-symmetry points at the boundary of the Brillouin zone, providing a reliable stability assessment without full phonon band structure calculation [5].

Table: Computational Methods for Hessian-Based Stability Analysis

| Method | Key Feature | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Full Hessian | Calculates complete second derivative matrix | Small to medium systems (<100 atoms) |

| Numerical Differentiation | Finite differences of analytical gradients | Default for most engines without analytical Hessian [11] |

| Mobile Block Hessian | Treats molecular fragments as rigid bodies | Large systems with localized regions of interest [11] |

| CBP Protocol | Phonons only at Γ and BZ boundary points | High-throughput screening of 2D materials [5] |

| Symmetric Displacements | Symmetry-adapted coordinate displacements | Systems with high symmetry [11] |

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

GaSe: Pressure-Induced Instabilities

Recent research on gallium selenide (GaSe) exemplifies how experimental phonon measurements validate computational predictions of structural instabilities. Pressure-dependent Raman spectroscopy revealed that GaSe undergoes an irreversible phase transition above 27.3 GPa, accompanied by the disappearance of all Raman modes [16]. This experimental observation correlates with computational predictions of dynamic instability under pressure.

Additionally, temperature-dependent Raman spectra of GaSe show phonon softening and broadening with increasing temperature, signaling anharmonic effects in the PES [16]. Quantitative analysis determined that the anharmonicity primarily originates from three-phonon interactions, with minor contributions from four-phonon processes [16]. This case study demonstrates how experimental phonon measurements can probe both the harmonic curvature (through frequency shifts) and anharmonic aspects (through linewidth analysis) of the PES.

2D Materials Database and Systematic Stability Mapping

Large-scale computational studies have systematically applied phonon stability analysis to screen materials databases. The Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB) employs the CBP protocol to assess dynamical stability across thousands of 2D materials [5]. In one study, 137 dynamically unstable 2D crystals were identified, and for 49 of these, displacement along unstable phonon modes followed by relaxation yielded dynamically stable structures [5].

This systematic approach revealed that symmetry-breaking distortions can significantly alter material properties, with band gaps opening by 0.3 eV on average in the stabilized structures [5]. The study demonstrates the critical importance of dynamical stability verification in computational materials discovery, as properties calculated for unstable configurations may substantially differ from those of the true stable phases.

Diagram Title: C2DB Stability Assessment and Structure Generation Workflow

Emerging Approaches: Machine Learning

Traditional phonon calculations using density functional theory (DFT) are computationally demanding, especially for complex systems or high-throughput studies. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) methodologies are revolutionizing this field by providing orders-of-magnitude improvement in computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy [10].

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) trained on DFT data can accurately reproduce PES curvature and thus phonon spectra at a fraction of the computational cost [10]. For the C2DB database, classification models trained on electronic structure representations achieved excellent predictive power for dynamical stability (area under ROC curve = 0.90), enabling rapid screening without explicit phonon calculations [10].

These AI approaches learn the relationship between atomic structure and the Hessian matrix, effectively capturing the chemical intuition that specific atomic arrangements lead to imaginary phonon modes while others produce stable configurations. As these methods mature, they promise to dramatically accelerate the identification of stable materials with tailored properties for specific applications.

Table: Key Computational Tools for Phonon Stability Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Electronic structure calculation | Provides energies, forces for Hessian construction |

| Phonopy | Phonon spectrum calculation | Post-processes force calculations to generate phonon bands |

| AMS Software | Vibrational spectroscopy module | Implements MBH, mode scanning, symmetric displacements [11] |

| C2DB Database | Repository of 2D material properties | Reference data for stability trends and material properties [5] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Efficient PES interpolation | Accelerated phonon calculations for high-throughput screening [10] |

| Structure Visualization (Avogadro, VESTA) | Normal mode animation | Visual interpretation of unstable vibrational modes [15] |

The connection between phonon spectra and the Hessian matrix provides a powerful theoretical and computational framework for probing the potential energy surface and assessing material stability. Imaginary frequencies serve as unambiguous indicators of dynamical instability, revealing directions on the PES where the system can lower its energy through structural distortion. As computational methodologies advance—from efficient partial Hessian calculations to machine learning acceleration—the ability to rapidly and accurately assess dynamical stability enables more reliable materials discovery and design. For researchers in drug development and materials science, incorporation of phonon stability analysis into standard computational workflows represents a critical step in validating predicted structures and ensuring the physical relevance of computational findings.

In computational materials science and drug development, phonon spectra serve as a critical indicator of a structure's stability. Within this framework, the appearance of negative frequencies—more accurately described as imaginary frequencies—signals a saddle point on the potential energy surface (PES), denoting structural instability. In contrast, a structure at a dynamic minimum exhibits only positive frequencies. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the origin and significance of negative phonon frequencies, details methodologies for their calculation, and presents recent advances in applying this analysis to predict material properties and stability. By integrating fundamental theory, computational protocols, and contemporary research case studies, this review serves as an essential resource for researchers and scientists engaged in the rational design of stable materials and molecular structures.

Phonons, the quantized lattice vibrations in a material, are a direct measure of the curvature of the potential energy surface about a stationary point, which could be an equilibrium structure (a minimum) or a transition state (a saddle point) [3]. The matrix of force constants, or the Hessian, is calculated as the second derivative of the energy with respect to atomic displacements:

$$ D{i\alpha,i^{\prime}\alpha^{\prime}}(\mathbf{R}p,\mathbf{R}{p^{\prime}})=\frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial u{p\alpha i}\partial u_{p^{\prime}\alpha^{\prime}i^{\prime}}}, $$

where (E) is the potential energy surface, and (u{p\alpha i}) is the displacement of atom (\alpha) in Cartesian direction (i) [3]. The eigenvalues of the mass-weighted Hessian (the dynamical matrix) are the squares of the phonon frequencies, (\omega{\mathbf{q}\nu}^2) [3] [11].

The fundamental distinction between a stable and an unstable structure lies in the sign of these eigenvalues:

- Positive Eigenvalues ((\omega_{\mathbf{q}\nu}^2 > 0)): Indicate positive curvature of the PES. The energy increases quadratically when atoms are displaced along the corresponding eigenvector, characteristic of a local minimum.

- Negative Eigenvalues ((\omega_{\mathbf{q}\nu}^2 < 0)): Indicate negative curvature of the PES. The energy decreases when atoms are displaced along the eigenvector, characteristic of a saddle point [3] [17].

The phonon frequencies, (\omega_{\mathbf{q}\nu}), are the square roots of these eigenvalues. Consequently, a stable structure at a minimum will have only real, positive phonon frequencies. In contrast, an unstable structure at a saddle point will exhibit imaginary frequencies (often reported as "negative" frequencies in computational outputs as a convention) [3]. These imaginary frequencies reveal the directions on the PES that lead to a lower energy, and their presence confirms that the structure is not dynamically stable [17].

Table 1: Interpreting Phonon Frequency Calculations

| Computational Output | Physical Meaning of Eigenvalue | Curvature of PES | Stationary Point Type | Structural Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Frequency | (\omega^2 > 0) | Positive | Local Minimum | Dynamically Stable |

| "Negative" (Imaginary) Frequency | (\omega^2 < 0) | Negative | Saddle Point | Dynamically Unstable |

Computational Methodologies

Calculating Phonon Frequencies

The standard approach for obtaining phonon spectra involves calculating the full matrix of second-order force constants. The process begins with a fully optimized geometry, as vibrational spectra are obtained at a local minimum on the PES; performing the calculation on an unoptimized structure will result in spurious imaginary frequencies [11].

The two primary methods for computing the Hessian are:

- Analytical Calculation: Only available in specific quantum chemistry engines (e.g., ADF for a limited set of functionals) [11].

- Numerical Differentiation: The most common method. The Hessian is constructed column-wise by performing finite displacements of each atom in the system and computing the resulting forces [11]. This requires (2 \times 3N) single-point calculations for a system of (N) atoms, which can be computationally demanding [11].

The workflow for a standard phonon frequency calculation is outlined in the diagram below.

Figure 1: Workflow for Phonon Frequency Analysis

Addressing Imaginary Frequencies

The appearance of imaginary frequencies necessitates further investigation to determine their physical significance. Two common scenarios are:

- Spurious Imaginary Frequencies: These are small in magnitude and often arise from numerical noise in the force constant calculation or an insufficiently tight convergence criterion during the geometry optimization. The

ReScanModesfunctionality in codes like AMS can be employed to recalculate these specific modes more accurately and identify if they are numerical artifacts [11]. - True Imaginary Frequencies (Soft Modes): Large, persistent imaginary frequencies indicate a genuine structural instability. The structure can be distorted along the eigenvector of the imaginary mode and re-optimized to find a lower-energy, stable structure [3] [17].

Table 2: Protocols for Handling Imaginary Frequencies

| Scenario | Characteristics | Recommended Action | Key Tools/Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spurious Mode | Small magnitude (< 10-50 cm⁻¹), sensitive to numerical parameters. | Rescan the frequency; tighten optimization convergence. | ReScanModes [11], ReScanFreqRange [11] |

| True Soft Mode | Large magnitude, corresponds to a physical distortion path. | Distort geometry along mode eigenvector; re-optimize. | Mode tracking, transition state search [11] |

| Partial Optimization | Imaginary modes from frozen internal degrees of freedom. | Use Mobile Block Hessian (MBH) method for adapted analysis. | Displacements Block [11] |

Table 3: Key Software and Methods for Phonon Analysis

| Tool/Method | Type | Primary Function | Application in Stability Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-Principles Method | Calculates electronic structure and energy. | Provides fundamental energy and forces for Hessian calculation. [18] |

| Finite Displacement Method | Numerical Technique | Computes second-order force constants. | Constructs the Hessian matrix for phonon dispersion. [19] |

| ALAMODE Package | Software Toolkit | Calculates anharmonic force constants. | Evaluates phonon-phonon interactions and lifetimes. [19] |

| Boltzmann Transport Eq. (BTE) | Theoretical Framework | Models particle-like phonon transport. | Calculates lattice thermal conductivity ((\kappa)). [19] |

| Wigner Transport Eq. (WTE) | Theoretical Framework | Models wave-like coherent phonon transport. | Captures interference effects in thermal transport. [19] |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Accelerated Sampling | Provides fast, accurate energy/force predictions. | Enables high-throughput screening of lattice dynamics. [18] |

Advanced Applications and Current Research

The analysis of phonon stability is not merely a binary check but a gateway to understanding and engineering material properties. Recent research demonstrates its power in high-throughput screening and novel material discovery.

Lattice Dynamics in Ionic Conductors

A 2025 study screened 3,903 sodium-containing structures to identify lattice dynamics signatures governing ionic conductivity in sodium superionic conductors (NASICONs) [18]. The workflow involved:

- Filtering structures from databases (OQMD, ICSD) and re-optimizing them using DFT.

- Selecting a robust machine-learning potential (EquiformerV2) to efficiently compute lattice dynamics.

- Screening for dynamic stability by ensuring the absence of imaginary frequencies in the Brillouin zone—a non-negotiable prerequisite for a viable material [18].

- Identifying key phonon-derived descriptors correlated with high ionic conductivity, such as low acoustic cutoff frequencies and an enhanced phonon mean squared displacement (MSD) of Na+ ions [18].

This research established a quantitative link between lattice softness (indicated by low-frequency phonons) and superionic behavior, enabling the use of phonon descriptors in machine-learning models to accelerate the discovery of solid electrolytes [18].

Stacking-Dependent Stability in 2D Materials

Advanced phonon analysis can also reveal subtle stability hierarchies between similar structures. A 2025 investigation of 2D copper benzenehexathiolate ((\mathrm{Cu_3BHT})) metal-organic frameworks compared three stacking arrangements (AA, AB, and C) [19]. The phonon calculations revealed that:

- The AB stacking configuration was dynamically unstable, as evidenced by the presence of imaginary frequencies in its phonon spectrum [19].

- The C and AA stacking configurations were dynamically stable, with all-real phonon dispersions [19].

This stacking-dependent stability, discernible only through phonon analysis, has direct implications for the synthetic realization and thermal transport properties of these materials.

The presence of negative (imaginary) phonon frequencies is a definitive signature of a saddle point on the potential energy surface, distinguishing an unstable structure from a stable minimum. Mastery of the computational protocols for calculating and interpreting phonon spectra is therefore indispensable for researchers aiming to validate the structural integrity of new materials or molecular drugs. As demonstrated by recent breakthroughs, integrating these stability analyses with high-throughput screening and machine learning creates a powerful paradigm for the rational design of next-generation functional materials, from high-conductivity solid electrolytes to thermally tunable metamaterials. Moving forward, the role of lattice dynamics as a fundamental design criterion will only grow in prominence across computational chemistry and materials science.

Soft modes, vibrational modes whose frequencies approach zero, serve as a fundamental precursor to structural phase transitions in a wide range of materials. This whitepaper delineates the intrinsic relationship between soft modes and material stability, framing the discussion within the context of phonon spectra and the significance of negative frequencies—a phenomenon indicative of dynamical instabilities. We provide a comprehensive guide detailing the theoretical underpinnings, experimental protocols for detecting these modes, and computational methodologies for their analysis. Furthermore, we explore the critical implications of these concepts for the development of stable functional materials, with particular relevance to advanced battery technologies and the design of molecular crystals in pharmaceutical science.

In the realm of condensed matter physics, a phase transition is the physical process where a system transitions between different states of matter, such as from a solid to a liquid or between two distinct crystalline structures [20]. These transitions are often heralded by the emergence of soft modes. A soft mode is a collective atomic vibration, or phonon, whose frequency dramatically decreases (softens) as the system approaches the transition point. The complete softening of a mode—where its frequency reaches zero—signals a loss of mechanical stability for the original structure, necessitating a transformation to a new, more stable phase.

The phenomenon of negative frequencies in phonon dispersion curves is directly linked to these instabilities. Computationally, a negative phonon frequency is the code's output for an imaginary frequency, arising from a negative eigenvalue of the dynamical matrix (the Hessian of the potential energy surface) [3]. In physical terms, this signifies a negative curvature of the potential energy surface along the corresponding atomic displacement coordinate. Rather than oscillating around an equilibrium position, atoms in such a mode experience a force that drives them toward a new, lower-energy configuration [3]. Thus, a soft mode that fully softens to a "negative" (imaginary) frequency is the direct mechanism for a structural phase transition.

Theoretical Foundations

Classifying Phase Transitions

Phase transitions are broadly classified by the behavior of thermodynamic potentials, which in turn is reflected in the behavior of soft modes.

- First-Order Transitions: These involve a discontinuous change in the first derivative of the free energy (e.g., density, magnetization) and often release or absorb latent heat [20]. Soft modes may not always go completely to zero in a first-order transition, as the system discontinuously jumps to the new phase before the instability is fully realized.

- Second-Order (Continuous) Transitions: These are characterized by a continuous change in the order parameter, which is a quantity that distinguishes the two phases. The Kibble-Zurek mechanism (KZM) describes the universal dynamics of such transitions, predicting how defects form as a system is driven through a critical point [21]. In these transitions, a soft mode frequency typically goes to zero continuously at the critical point, and the growth of the order parameter is directly linked to the atomic displacement pattern of this soft mode.

The Link Between Soft Modes and Stability

The connection is rooted in the relationship between phonon frequencies and the curvature of the potential energy surface (PES).

- Positive Frequencies and Stable Minima: When a structure resides at a local minimum on the PES, all phonon frequencies are positive real numbers. The curvature of the PES is positive in all directions, and atomic displacements increase the system's energy [3].

- Soft Modes and Flattening Curvature: As external conditions like temperature or pressure are varied toward a phase transition, the PES evolves. The curvature along a specific vibrational coordinate flattens, leading to a decrease in the corresponding phonon frequency. A very flat PES curvature means atoms can be displaced with minimal energy cost.

- Negative Frequencies and Saddle Points: A "negative" (imaginary) frequency results from a negative curvature of the PES [3]. This indicates the system is at a saddle point, not a minimum. The atomic displacements associated with this imaginary mode lower the system's energy, driving the transformation to a new, stable structure.

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental relationship between the potential energy surface and phonon stability.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Measuring the Density of States

The Granular Density of Modes (gDOM), analogous to the phonon Density of States (DOS) in atomic crystals, can be measured experimentally to probe soft modes and instabilities, particularly near the jamming transition [22].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for Granular Density of Modes Measurement

| Parameter | Specification | Role in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Granular Material | 6 mm & 8 mm ABS plastic spheres | Model system with tunable interactions; particle size sets the characteristic length scale. |

| Excitation Method | Single steel impactor ball | Generates a broadband acoustic pulse to excite a wide spectrum of vibrational modes. |

| Detection Sensor | Piezoelectric sensors | Buried within the granular material to record the velocity response of the grains. |

| Data Processing | Velocity Autocorrelation Function, ( C_v(t) ) | Quantifies how the velocity of particles correlates with itself over time. |

| gDOM Calculation | Fourier Transform of ( C_v(t) ) | Converts the temporal correlation data into the frequency-domain density of modes, ( D(\omega) ). |

| Control Parameter | Applied pressure (0.8 - 15 kPa) | Tunes the system's proximity to the jamming transition, affecting the abundance of soft modes. |

The experimental workflow for this method is summarized below.

Computational Detection of Instabilities

In computational materials science, phonon spectra are calculated to assess stability.

- Force Constant Calculation: The matrix of force constants, ( D_{i\alpha,i^{\prime}\alpha^{\prime}} ), is computed as the second derivative of the total energy with respect to atomic displacements, typically using Density Functional Theory (DFT) [3].

- Dynamical Matrix Construction: The force constants are Fourier transformed to build the dynamical matrix for a given wave vector ( \mathbf{q} ).

- Diagonalization: The dynamical matrix is diagonalized to obtain its eigenvalues, ( \omega^2_{\mathbf{q}\nu} ), and eigenvectors.

- Frequency Analysis: The phonon frequencies are ( \omega{\mathbf{q}\nu} = \sqrt{\omega^2{\mathbf{q}\nu}} ). A negative value of ( \omega^2{\mathbf{q}\nu} ) results in an imaginary ( \omega{\mathbf{q}\nu} ), which codes often report as a "negative" frequency [3] [23].

Table 2: Interpreting Computational Phonon Calculation Results

| Calculation Output | Physical Meaning | Material Stability Implication |

|---|---|---|

| All ω > 0 | Structure is at a local minimum on the PES. | Dynamically stable. |

| Soft Modes (ω → 0) | Curvature of PES is flattening along a specific atomic displacement. | Precursor to a phase transition; structure is nearing an instability. |

| Imaginary Frequencies (ω < 0) | Negative PES curvature; structure is at a saddle point. | Dynamically unstable; the crystal will transform along the mode's displacement pattern. |

When imaginary frequencies are detected, several actions can be taken:

- Structural Relaxation: Freezing the atomic displacement of the unstable mode and allowing the structure to relax can lead to a new, stable phase [23].

- Anharmonic Methods: For materials that are stable experimentally but show instabilities in harmonic calculations (e.g., due to strong anharmonicity), methods like the Temperature Dependent Effective Potential (TDEP) can be employed to stabilize the calculation and obtain physical results [23].

Case Study: Phase Transitions in Battery Cathode Materials

The stability of O3-type layered sodium cathode materials (NaxMn0.4Ni0.3Fe0.15Li0.1Ti0.05O2) is governed by their resistance to irreversible phase transitions and transition metal (TM) migration. Recent research has identified a key structural parameter, the spacing ratio ( R = d{O-Na-O}/d{O-TM-O} ), which controls these phenomena and is intimately linked to the underlying lattice dynamics [24].

Materials with a high ( R ) ratio (e.g., ~1.97 for Na0.55) exhibit a significantly stretched interstitial tetrahedral structure in the Na layer. This stretched geometry creates a higher energy barrier for TM ions to migrate into the Na layer, thereby suppressing this degradation pathway. Furthermore, a high ( R ) value places the structure in a preparatory stage for the O3 to P3 phase transition. This facilitates a rapid and smooth transition, reducing mechanical strain and improving reversibility compared to materials with lower ( R ) ratios [24]. The enhanced stability from high ( R )-values is a key factor in the performance of advanced P2/O3 hybrid cathode structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Soft Mode Research |

|---|---|---|

| ABS Plastic Spheres | Model granular material for jamming studies. | Provides a tunable experimental system to study soft modes and the vibrational density of states near the jamming transition [22]. |

| Piezoelectric Sensors | Converts mechanical vibrations into electrical signals. | Used to measure the velocity response of individual grains in a perturbed granular material or other soft matter system [22]. |

| DFT Software (e.g., ABINIT) | Calculates electronic structure and derived properties. | Used to compute the second-order force constants, which are the foundation for calculating phonon spectra and identifying soft/imaginary modes [23]. |

| Phonopy | A package for phonon calculations at harmonic and quasi-harmonic levels. | Post-processes force constants from DFT to generate phonon band structures and density of states, outputting frequencies that can be real or imaginary [3]. |

| TDEP | Computes effective harmonic force constants from molecular dynamics. | Stabilizes phonon calculations for anharmonic materials, providing a physical workaround for spurious imaginary frequencies arising from the harmonic approximation [23]. |

The study of soft modes and their manifestation as imaginary frequencies in phonon spectra provides a profound and predictive framework for understanding material stability and phase transitions. Moving beyond a simple binary indicator of instability, the analysis of these modes offers a mechanistic pathway for engineering material properties. The experimental and computational methodologies detailed herein provide a robust toolkit for researchers to probe these phenomena across diverse systems—from granular matter and metallic glasses to complex battery electrodes and molecular crystals.

The implications for drug development are significant, as polymorphic phase transitions in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) can alter drug solubility, bioavailability, and stability. Applying these principles allows for the proactive design of robust molecular crystals, mitigating the risk of deleterious phase changes during processing or storage. Future research will undoubtedly leverage high-throughput computational screening of phonon instabilities to guide the synthesis of next-generation functional materials with tailored stability.

Computational Strategies for Accurate Phonon Calculation and Analysis

Phonons, the quantized lattice vibrations in crystalline materials, are fundamental to understanding a wide range of material properties including thermal conductivity, mechanical behavior, electrical conductivity, superconductivity, and phase stability [25] [26]. The calculation of phonon spectra is particularly crucial for assessing dynamic and thermodynamic stability of materials, as evidenced by the appearance of imaginary frequencies (negative in numerical calculations) which signal structural instabilities [25] [27]. First-principles approaches based on density functional theory (DFT) have emerged as powerful tools for investigating these lattice dynamical properties without relying on empirical parameters.

Two primary computational methodologies have been established for first-principles phonon calculations: the finite displacements method (also known as the finite differences approach) and density functional perturbation theory (DFPT). The finite displacements method involves physically displacing atoms in a supercell and computing the resulting forces to construct the force constants matrix [28] [25]. In contrast, DFPT employs an analytical approach to directly calculate the second-order derivatives of the energy with respect to atomic displacements through response functions [26]. Both methods ultimately solve the dynamical matrix eigenvalue problem to obtain phonon frequencies and eigenvectors, but they differ significantly in their computational strategies, implementation requirements, and practical applications.

The significance of imaginary phonon frequencies cannot be overstated in materials stability research. These "soft modes" represent vibrational modes with negative squared frequencies, indicating that the crystal structure is not in its lowest energy configuration and may undergo phase transitions to more stable arrangements [28] [27]. Accurate detection and interpretation of these imaginary frequencies through first-principles calculations has become an essential component of computational materials discovery and design, enabling researchers to predict phase stability and identify potential new materials with desired properties.

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Equations of Lattice Dynamics

The theoretical foundation for both finite displacements and DFPT approaches lies in the harmonic approximation of lattice dynamics. For a periodic crystal, the phonon frequencies ωq,m and eigenvectors Um(qκ′β) at wavevector q in the Brillouin zone are obtained by solving the generalized eigenvalue problem:

∑κ′βC˜κα,κ′β(q)Um(qκ′β)=Mκωq,m2Um(qκα)

where κ labels atoms in the unit cell, α and β are Cartesian coordinates, C̃κα,κ′β(q) represents the interatomic force constants in reciprocal space, and Mκ is the atomic mass [26]. This equation describes how atoms and their neighbors vibrate collectively in normal modes with specific frequencies.

The interatomic force constants C̃κα,κ′β(q) are fundamentally related to the second derivatives of the total energy E with respect to atomic displacements τκα:

Cκα,κ′β=∂2E∂τκα∂τκ′β

In the finite displacements approach, these derivatives are approximated numerically by applying small atomic displacements and computing the resulting forces [28]. In DFPT, these derivatives are calculated analytically through linear response theory [26]. For polar materials, additional considerations are necessary to correctly describe the long-range dipole-dipole interactions in the q→0 limit, requiring the computation of Born effective charges and dielectric tensors [26].

Treatment of Imaginary Frequencies

Imaginary frequencies (ω = iγ, where γ is real) arise when ω² is negative, indicating vibrational modes that grow exponentially rather than oscillate. Mathematically, this occurs when the eigenvalues of the dynamical matrix become negative, signifying that the current atomic configuration corresponds to a saddle point rather than a local minimum on the potential energy surface [27].

In computational outputs, these are typically reported as negative values or as frequencies labeled with "f/i" instead of just "f" [28]. The presence of imaginary modes necessitates careful analysis—while small imaginary modes might result from numerical inaccuracies, significant imaginary modes often indicate genuine structural instabilities that may drive reconstructive phase transitions [27].

Table 1: Key Equations in Lattice Dynamics

| Equation | Physical Meaning | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamical Matrix Eigenvalue Problem: ∑κ′βC˜κα,κ′β(q)Um(qκ′β)=Mκωq,m2Um(qκα) | Determines phonon frequencies and polarization vectors | Fundamental equation solved by both finite displacements and DFPT methods |

| Born Effective Charges: Zκ,βα*=Ω0∂P∂τκα=∂Fκ,α∂Eβ | Relates atomic displacements to polarization changes | Essential for correct treatment of LO-TO splitting in polar materials |

| Dielectric Tensor: εαβ0=εαβ∞+4π∑mfm,αβ2(ωmΓ)2 | Describes electronic and ionic response to electric field | Critical for modeling dielectric properties and polar phonons |

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR): ∑κC˜κα,κ′β(q=0)=0 | Ensures invariance of energy with respect to translations | Numerical constraint applied during force constants calculation |

Finite Displacements Methodology

Core Implementation

The finite displacements method implements a direct numerical approach for computing second-order force constants by applying small atomic displacements in a supercell and calculating the resulting forces [28]. In the VASP code, this methodology is activated by setting IBRION=5 or IBRION=6 in the INCAR file [28]. The IBRION=5 setting displaces all atoms in all three Cartesian directions, resulting in 6N calculations (where N is the number of atoms) when using NFREE=2 (central differences). For high-symmetry systems, IBRION=6 offers a more efficient approach by considering only symmetry-inequivalent displacements and filling the remainder of the force-constants matrix using symmetry operations [28].

The step size for displacements is controlled by the POTIM parameter, with a default value of 0.015 Å in modern VASP versions (≥5.1) [28]. The NFREE parameter determines how many displacements are used for each direction and ion: NFREE=2 employs central differences (±POTIM), NFREE=4 uses four displacements (±POTIM and ±2×POTIM), while NFREE=1 utilizes a single displacement (though this is strongly discouraged due to potential inaccuracies) [28].

Practical Protocols and Convergence

Accurate force calculations are paramount for reliable phonon spectra using the finite displacements approach. Several key parameters require careful convergence testing to ensure numerical precision:

- Plane-wave cutoff (

ENCUT): Must be sufficiently large to converge the stress tensor, typically requiring the default cutoff to be increased by approximately 30% [28]. Systematic increase in steps of 15% is recommended until convergence is achieved. - k-point sampling: Density in the KPOINTS file must provide sufficient Brillouin zone sampling. When increasing supercell size for q-point sampling, the k-point density should be decreased to maintain equivalent resolution [28].

- Supercell size: Must be large enough to capture the relevant interatomic interactions. Convergence with respect to supercell size should be tested by increasing dimensions until phonon frequencies stabilize.

The computational cost scales significantly with system size. For IBRION=5 with NFREE=2, the number of required calculations is 6N, where N is the number of atoms in the supercell [28]. This makes the method particularly expensive for low-symmetry systems or materials with large unit cells. For such cases, IBRION=6 provides substantial computational savings by leveraging crystal symmetry.

Diagram 1: Finite Displacements Phonon Workflow

Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT)

Theoretical Framework and Implementation

Density Functional Perturbation Theory provides an analytical framework for computing the second-order derivatives of the energy with respect to atomic displacements through linear response theory [26]. Unlike the finite displacements approach, DFPT directly calculates the interatomic force constants in reciprocal space by solving self-consistent equations for the first-order changes in the electron density and wavefunctions [26].

The key advantage of DFPT lies in its ability to compute phonon frequencies at arbitrary q-points without requiring supercell constructions. This makes DFPT particularly efficient for calculating full phonon dispersions along high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin zone [26]. Additionally, DFPT naturally provides access to Born effective charges (Z*) and dielectric tensors (ε∞), which are essential for correctly describing the longitudinal-transverse optical (LO-TO) splitting in polar materials [26].

The Born effective charge tensor captures the coupling between atomic displacements and electric fields:

Zκ,βα*=Ω0∂P∂τκα=∂Fκ,α∂Eβ

where P is the polarization, τκα are atomic displacements, Fκ,α are forces on atoms, and Eβ is the electric field [26]. The dielectric permittivity tensor resulting from electronic polarization (ε∞) combines with the phonon frequencies at the Brillouin zone center (ωΓm) and oscillator strengths to yield the static dielectric tensor:

εαβ0=εαβ∞+4π∑mfm,αβ2(ωmΓ)2

Computational Protocols and Validation

DFPT implementations, such as in the ABINIT software package, require careful attention to numerical convergence parameters [26]:

- k-point and q-point grids: Equivalent grids that respect crystal symmetries with a density of approximately 1500 points per reciprocal atom are recommended [26]. The q-point grid is always Γ-centered.

- Plane-wave cutoff: Determined based on the hardest element in each compound according to pseudopotential tables like PseudoDojo [26].

- Sum rules enforcement: The Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR: ∑κC̃κα,κ′β(q=0)=0) and Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR: ∑κZκ,βα*=0) must be imposed to ensure translational invariance and charge neutrality [26].

Validation of DFPT calculations involves several diagnostic checks. Large breaking of the ASR or CNSR may indicate insufficient plane-wave cutoff [26]. Small negative frequencies near the Γ point are often numerical artifacts associated with inadequate k-point or q-point sampling rather than genuine instabilities [26]. Materials with likely real instabilities show significant imaginary frequencies away from the Γ point.

Table 2: DFPT Calculation Parameters and Convergence Criteria

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Purpose | Convergence Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| k-point density | ~1500 points per reciprocal atom | Brillouin zone sampling | Increase until phonon frequencies change by < 0.1 THz |

| Plane-wave cutoff | PseudoDojo recommended values | Basis set completeness | Increase until total energy changes by < 1 meV/atom |

| Force convergence | < 10⁻⁶ Ha/Bohr | Structural relaxation | Tight thresholds essential for accurate phonons |

| Stress convergence | < 10⁻⁴ Ha/Bohr³ | Cell optimization | Particularly important for volume-dependent properties |

Comparative Analysis: Finite Displacements vs. DFPT

Methodological Comparison

The finite displacements and DFPT approaches offer complementary strengths and limitations for first-principles phonon calculations. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate method for specific research applications.

The finite displacements method is algorithmically simpler and easier to implement, as it primarily requires multiple single-point DFT calculations on displaced structures [28]. It can be used with any exchange-correlation functional and is less sensitive to specific implementation details in DFT codes [28]. However, it requires careful supercell size convergence and becomes computationally expensive for large systems or low symmetries due to the 6N scaling of calculations [28]. The method is also susceptible to numerical errors from finite step sizes and may require post-processing to enforce sum rules.

DFPT provides a more elegant mathematical formulation with direct calculation of response properties [26]. It enables efficient computation of phonons at arbitrary q-points without supercells and naturally incorporates LO-TO splitting for polar materials [26]. The method exhibits better scaling with system size for single q-point calculations but requires separate calculations for each q-point. Implementation is more complex and tightly integrated with the DFT code, potentially limiting functional choices.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Finite Displacements and DFPT Approaches

| Feature | Finite Displacements | Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Numerical differentiation through atomic displacements | Analytical differentiation through linear response |

| q-point Sampling | Requires supercells for q-points other than Γ | Direct calculation at arbitrary q-points |

| Computational Scaling | ~6N calculations with supercell size N | Better scaling for single q-points |

| Implementation Complexity | Relatively simple, uses standard DFT | Complex, requires dedicated DFPT implementation |

| LO-TO Splitting | Requires special treatment for polar materials | Naturally includes dielectric response |

| Functional Compatibility | Works with any XC functional | May be limited by DFPT implementation |

| Typical Use Cases | Small systems, non-standard functionals | Polar materials, full phonon dispersions |

Handling of Imaginary Frequencies

Both methodologies provide mechanisms for detecting and analyzing imaginary phonon frequencies, which are crucial for assessing material stability. In finite displacements outputs, imaginary modes are typically labeled with "f/i" instead of "f" in the OUTCAR file, with the frequency reported as a negative value [28]. In DFPT, similar reporting conventions are used, with additional flags to identify potentially problematic calculations where small negative frequencies might be numerical artifacts rather than genuine instabilities [26].

The interpretation of imaginary frequencies requires careful consideration of numerical precision. In finite displacements, small imaginary modes might result from insufficient supercell size or inadequate displacement step size. In DFPT, small imaginary modes near the Γ point (0<|q|<0.05 in fractional coordinates) often indicate inadequate k-point sampling rather than real instabilities [26]. Significant imaginary frequencies away from the Γ point typically represent genuine structural instabilities that may drive phase transitions [27].

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

High-Throughput Phonon Databases

The development of robust first-principles phonon methodologies has enabled the creation of large-scale phonon databases for materials discovery and design. Petretto et al. reported a comprehensive database containing full phonon dispersions for 1521 semiconductor compounds calculated using DFPT [26]. This database includes derived dielectric and thermodynamic properties, providing a valuable resource for screening materials with specific vibrational characteristics.

High-throughput phonon calculations have revealed that approximately 10% of known semiconductor compounds exhibit imaginary frequencies, indicating dynamical instabilities [26]. These instabilities often correspond to known phase transitions or suggest potential metastable phases that might be synthesized under specific conditions. The systematic identification of such materials through phonon analysis represents a powerful approach for discovering new functional materials with tailored properties.

Machine Learning Accelerated Phonon Calculations

Recent advances in machine learning have introduced new paradigms for accelerating phonon calculations while maintaining first-principles accuracy. Two primary strategies have emerged: direct prediction of phonon properties using graph neural networks, and machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) that learn potential energy surfaces [25].

The MACE (Multi-Atomic Cluster Expansion) framework has demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting phonon properties across diverse materials systems [25] [29]. For metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)—materials with large unit cells that make traditional DFT phonon calculations prohibitively expensive—fine-tuned MACE models such as MACE-MP-MOF0 have achieved excellent agreement with DFT and experimental data for phonon density of states, thermal expansion, and bulk moduli [29].

Machine learning approaches have also enabled novel dataset generation strategies. Instead of computing numerous supercells with single-atom displacements, ML training can utilize fewer supercells with all atoms randomly displaced by 0.01-0.05 Å, significantly reducing computational costs while maintaining accuracy [25]. Universal MLIPs trained on diverse materials datasets can identify underlying similarities across different structures and chemistries, enabling accurate phonon predictions with minimal material-specific calculations [25].

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Accelerated Phonon Workflow

Case Study: Imaginary Frequencies and Material Stability

The significance of imaginary phonon frequencies in stability assessment is exemplified by first-principles studies of hexahydride perovskites A₂(Pd/Pt)H₆ (A = alkali metal) for hydrogen storage applications [27]. In these compounds, thorough analysis of phonon spectra combined with elastic constants and formation energies provided a comprehensive stability assessment [27]. The absence of imaginary frequencies in the phonon spectra confirmed the dynamic stability of these compounds, supporting their potential as viable hydrogen storage materials.

Similarly, in charge-density-wave (CDW) materials like 1T-TiSe₂, imaginary phonon modes at specific q-vectors signal lattice instabilities that drive the CDW transition [30]. Time-resolved experimental studies combined with DFPT calculations have revealed how these soft modes evolve with temperature and how CDW fluctuations persist above the transition temperature, providing insights into the complex interplay between electronic and lattice degrees of freedom [30].

Essential Software Packages

Table 4: Key Software Packages for First-Principles Phonon Calculations

| Software | Methodology | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Finite displacements (IBRION=5/6) [28] | Robust, well-documented, extensive functionality | General materials screening, surface and interface studies |

| ABINIT | DFPT [26] | Open-source, high-throughput capabilities | Large-scale phonon database generation |

| Phonopy | Finite displacements (post-processing) [31] | Open-source, works with multiple DFT codes | Structure optimization, thermal properties |

| QUANTUM ESPRESSO | DFPT and finite displacements | Open-source, comprehensive phonon capabilities | General-purpose phonon calculations |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Parameters

Table 5: Essential Computational Parameters for Phonon Calculations

| Parameter | Function | Recommended Values | Stability Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| POTIM | Displacement step size in finite differences [28] | 0.015 Å (default) | Too large: numerical errors; Too small: force noise |

| NFREE | Number of displacements per atom/direction [28] | 2 (central differences) | NFREE=1 can yield inaccurate force constants |

| ENCUT | Plane-wave energy cutoff [28] | Default + ~30% for stress convergence | Underconverged: spurious imaginary modes |

| k-point density | Brillouin zone sampling [26] | ~1500 points/reciprocal atom | Sparse sampling: artificial instabilities |

| Supercell size | Real-space force constants range [28] | System-dependent convergence | Too small: unphysical long-range interactions |

First-principles phonon calculations using finite displacements and DFPT have become indispensable tools for investigating material stability and lattice dynamical properties. While both methods ultimately solve the same fundamental equations of lattice dynamics, they offer complementary advantages: finite displacements provides straightforward implementation and compatibility with various exchange-correlation functionals, while DFPT offers analytical precision and natural treatment of dielectric responses in polar materials.

The detection and interpretation of imaginary frequencies remains a crucial aspect of these calculations, serving as indicators of structural instabilities that may drive phase transitions or signal metastable structures. Recent advances in machine learning interatomic potentials are dramatically accelerating high-throughput phonon calculations, enabling the screening of complex material systems such as metal-organic frameworks that were previously inaccessible to conventional DFT approaches.

As computational power continues to grow and methodologies further refine, first-principles phonon calculations will play an increasingly central role in the discovery and design of novel materials with tailored thermal, mechanical, and electronic properties. The integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation creates a powerful feedback loop for advancing our understanding of lattice dynamics and material stability.

Phonons, the quantized lattice vibrations in crystalline materials, are fundamental to understanding and predicting a wide array of material properties, including thermal conductivity, mechanical behavior, thermodynamic stability, and superconductivity [25] [32]. Crucially, phonon spectra provide essential insights into material stability through the analysis of vibrational frequencies. The appearance of imaginary frequencies (often represented as negative values in computational outputs) in phonon spectra signifies dynamical instability, indicating that the crystal structure is at a saddle point on the potential energy surface rather than a local minimum [3]. These imaginary frequencies correspond to vibrational modes where the energy decreases quadratically when atoms are displaced in the direction of the associated eigenvector, meaning the structure is not stable and may transform to a different phase [3].

Traditional first-principles methods for phonon calculation, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), are prohibitively computationally expensive for high-throughput screening, particularly for complex material systems like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) which can contain hundreds or thousands of atoms per unit cell [29] [33]. This computational bottleneck has severely limited the exploration of phonon-mediated properties across vast chemical spaces. The emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) now offers a pathway to overcome this limitation, providing near-DFT accuracy with computational costs reduced by several orders of magnitude [32]. This technical guide examines how MLIPs are revolutionizing high-throughput phonon screening while addressing the critical challenge of accurately predicting phonon spectra and stability indicators.

Machine Learning Solutions for Phonon Property Prediction

Machine learning approaches for predicting phonon properties have evolved into two primary strategies: direct property prediction and interatomic potential construction.

Direct Phonon Property Prediction

Some models bypass interatomic potentials entirely, instead directly predicting phonon properties using graph neural networks (GNNs) trained on large phonon databases. Notable architectures include:

- Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network (ALIGNN): Incorporates bond connectivity and bond angle information to predict phonon density of states and thermodynamic properties [25].

- Euclidean Neural Network (E(3)NN): Captures crystal symmetry and achieves reliable predictions with relatively small training datasets (~1200 examples) [25].

- Virtual Node Graph Neural Network (VGNN): Enables direct prediction of full phonon dispersion without computing the dynamical matrix for each material [25].

- DeeperGATGNN: Employs a deep graph neural network with a global attention mechanism for predicting vibrational frequencies [25].

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

MLIPs learn the functional relationship between atomic configurations and the potential energy surface (PES), enabling the calculation of phonons through the second derivatives of the PES. Universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) have emerged as foundational models capable of handling diverse chemistries and crystal structures [32]. Benchmark studies evaluating uMLIPs on approximately 10,000 ab initio phonon calculations reveal significant variations in performance for predicting harmonic phonon properties, even among models that excel at predicting energies and forces near equilibrium [32].

Table 1: Performance of Universal Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials for Phonon Calculations

| Model | Architecture | Phonon Prediction Accuracy | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP-0 | Atomic Cluster Expansion | High accuracy after fine-tuning | Efficient message-passing; Good transferability [29] [32] |

| CHGNet | Graph Neural Network | Moderate accuracy | Small architecture (~400k parameters) [32] |

| M3GNet | Three-body Interactions | Established performance | Pioneering uMLIP; Good general performance [32] |

| eqV2-M | Equivariant Transformers | High accuracy in benchmarks | Higher-order equivariant representations [32] |

| ORB | Smooth Overlap + Graph Network | Variable performance | Separate force prediction [32] |

Implementing High-Throughput Phonon Workflows

Specialized Workflows for Complex Materials

For chemically complex materials like MOFs, specialized workflows have been developed to address the limitations of general-purpose MLIPs. The MACE-MP-MOF0 model exemplifies this approach, created through fine-tuning the MACE-MP-0 foundation model on a curated dataset of 127 representative MOFs [29] [33]. This specialized model significantly improves the accuracy of phonon density of states and corrects imaginary phonon modes present in the general-purpose foundation model, enabling reliable high-throughput phonon calculations for porous materials [29].

The training dataset was constructed using multiple strategies to ensure comprehensive coverage of the potential energy surface: (1) molecular dynamics simulations using an NPT ensemble with frames selected via farthest point sampling to maximize descriptor space spread; (2) strained configurations generated by expanding and compressing unit cells; and (3) geometry optimization trajectories retaining multiple frames using farthest point sampling [29]. This multi-faceted approach yielded 4,764 DFT data points split into training (85%), testing (7.5%), and validation (7.5%) sets [29].

Efficient Training Dataset Generation

A key innovation in accelerating MLIP development for phonons is the efficient generation of training data. Instead of the traditional approach requiring numerous supercell calculations with small displacements of single atoms, researchers have developed optimized strategies using randomly perturbed structures. The method involves:

- Generating a subset of supercell structures for each material with all atoms randomly displaced by 0.01-0.05 Å [25]

- Using these configurations to compute interatomic forces with DFT

- Training MLIPs on the resulting structures and forces

- Leveraging the MACE architecture which employs message-passing neural networks with a cut-off radius for defining atomic interactions [25]

This approach significantly reduces the number of required DFT calculations while maintaining accuracy, as demonstrated by a model trained on 15,670 supercell structures across 2,738 materials containing 77 elements, which achieved a mean absolute error of 0.18 THz for vibrational frequencies [25].

Diagram 1: High-throughput phonon screening workflow using machine learning potentials. The process begins with generating diverse training structures, followed by DFT calculations to create reference data for training MLIPs, which then enable rapid phonon screening.

Validation and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Assessment of MLIP Performance

Rigorous benchmarking of universal MLIPs reveals their capabilities and limitations for phonon property prediction. Performance evaluation across approximately 10,000 materials provides comprehensive metrics for model comparison [32]. The most accurate models achieve errors approaching the variability between different DFT functionals (PBE vs. PBEsol), suggesting they have reached a practical accuracy limit for high-throughput screening applications [32].

Table 2: Phonon Calculation Methods and Performance Comparison

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Throughput | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (Traditional) | Very High | Reference | Low | Small systems; Reference calculations [29] |

| DFTB/GFN1-xTB | Medium | Moderate (5% deviation) | Medium | Preliminary screening [29] |

| Classical Force Fields | Low | Low (Underestimates bulk modulus >50%) | High | Large-scale MD simulations [29] |

| Universal MLIPs | Low to Medium | High (Near-DFT) | High | High-throughput screening [32] |

| Specialized MLIPs | Low to Medium | Very High (Fine-tuned) | High | Targeted material classes [29] |

Addressing Imaginary Frequency Artifacts

A critical challenge for MLIPs in stability assessment is the accurate prediction of imaginary frequencies. Foundation models like MACE-MP-0 sometimes produce unphysical imaginary phonon modes in MOFs, indicating limitations in capturing the complex potential energy surface of these materials [29]. The fine-tuned MACE-MP-MOF0 model successfully corrects many of these artifacts, demonstrating that targeted training on representative systems can significantly improve stability predictions [29]. This advancement is crucial for reliable high-throughput assessment of dynamical stability across material families.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MLIP Development and Phonon Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MACE Architecture | Message-passing neural network for MLIPs | High-accuracy force field development [29] [25] |

| VASP | DFT software for reference calculations | Generating training data [32] |

| ALAMODE | Phonon calculation package | Harmonic/anharmonic IFCs [19] |

| ASE | Atomic simulation environment | Structure manipulation and analysis [29] |

| MDR Phonon Database | Repository of phonon calculations | Benchmarking and training [32] |

| QMOF Database | Curated MOF structures | Training set curation [29] |

Diagram 2: MLIP architecture for phonon calculations, illustrating the process from atomic structure input to phonon frequency prediction. The MACE model generates energies and forces, which are used to compute force constants and ultimately determine phonon spectra and material stability.