Metal-Centered vs Charge Transfer Excited States: Fundamentals, Applications, and Design Strategies for Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of metal-centered (MC) and charge-transfer (CT) excited states in transition metal complexes, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals.

Metal-Centered vs Charge Transfer Excited States: Fundamentals, Applications, and Design Strategies for Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of metal-centered (MC) and charge-transfer (CT) excited states in transition metal complexes, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. We cover foundational principles distinguishing MC from ligand-to-metal (LMCT) and metal-to-ligand (MLCT) charge transfer states, including their electronic structures and photophysical behaviors. The content details advanced methodologies for probing these states, their application in photoactivatable metallodrugs for cancer therapy and anti-infective agents, and strategies to troubleshoot challenges like excited-state deactivation and photostability. Finally, we present validation techniques and comparative analyses of different metal complexes, offering design principles for optimizing performance in photodynamic therapy (PDT), photoactivated chemotherapy (PACT), and related biomedical applications.

Unraveling Electronic Excitations: A Primer on MC and CT States

Defining Metal-Centered (MC) Ligand Field Excited States

In the study of transition metal complexes, excited states are broadly categorized as either metal-centered (MC) or charge-transfer (CT) states. MC states represent a fundamental class of excitations where electron redistribution occurs primarily within the metal's d-orbitals, without significant transfer of charge between the metal and its surrounding ligands. Understanding MC states is crucial for interpreting the photophysical behavior, stability, and catalytic properties of coordination compounds, particularly in contrast to charge-transfer states such as Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) or Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) states, which involve substantial electron density shift between metal and ligand orbitals [1] [2]. This distinction forms the cornerstone of photochemical research aimed at developing more efficient photocatalysts, luminescent materials, and molecular devices.

Theoretical Foundation of MC States

Electronic Origin and Ligand Field Theory

Metal-centered excited states arise from electronic transitions between molecular orbitals that are predominantly metal-based in character. According to ligand field theory, which combines crystal field theory with molecular orbital theory, when ligands coordinate to a metal center, they create an electrostatic field that splits the energy of the metal's d-orbitals [3] [4]. The pattern of this splitting depends critically on the molecular geometry. In an octahedral complex, the d-orbitals split into two sets: the higher energy eg orbitals (dx²-y² and dz²) and the lower energy t2g orbitals (dxy, dxz, dyz). The energy difference between these sets is designated as Δo, the octahedral ligand field splitting parameter [5] [3]. A MC transition occurs when an electron is promoted from a lower-energy d-orbital to a higher-energy d-orbital within this split manifold. These transitions are often called "d-d transitions" and represent the simplest form of MC excited states [5].

Key Characteristics and Geometric Consequences

Metal-centered excited states exhibit several distinguishing features that contrast sharply with charge-transfer states. MC states generally possess relatively weak molar absorptivity (ε ≈ 10-100 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) compared to intense charge-transfer bands, as d-d transitions are parity-forbidden and only gain intensity through vibronic coupling [5]. More significantly, population of MC states often leads to substantial metal-ligand bond elongation. This structural distortion occurs because electrons are promoted from largely non-bonding t2g orbitals to antibonding eg orbitals, weakening the metal-ligand bonds [1]. The potential energy surfaces of MC states are consequently displaced relative to both the ground state and charge-transfer states, creating energetic funnels that facilitate non-radiative decay [1]. These characteristics make MC states pivotal in determining the photostability and excited-state dynamics of transition metal complexes.

Factors Influencing MC State Energetics and Dynamics

Ligand Field Strength and Metal Identity

The energy and accessibility of MC states are governed by several key factors, with ligand field strength representing perhaps the most significant parameter. Strong-field ligands (e.g., CN⁻, CO, phenanthroline) produce large Δo values, resulting in higher-energy MC states that may lie above the lowest charge-transfer states [1] [5]. Conversely, weak-field ligands (e.g., H₂O, Cl⁻) yield small Δo values and lower-energy MC states that often dominate the photophysical decay pathways. The identity of the metal center also critically influences MC state energetics. For a given ligand, Δo increases down a group (3d << 4d < 5d) due to more diffuse d-orbitals in heavier metals, and generally increases with oxidation state as higher-charge metals create stronger ligand fields [1] [2]. This explains why first-row transition metals like Fe(II) in [Fe(bpy)₃]²⁺ typically exhibit ultrafast MC-mediated decay (50-80 fs), while second and third-row analogues like Ru(II) in [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ display long-lived MLCT states suitable for photocatalysis [1].

Coordination Geometry and Spin State

The coordination geometry around the metal center dramatically affects the d-orbital splitting pattern and thus MC state energetics. In tetrahedral complexes, the d-orbital splitting is inverted and smaller (Δt ≈ 4/9 Δo), with the e orbitals (dx²-y², dz²) lower in energy than the t2 orbitals (dxy, dxz, dyz) [3] [4]. This fundamentally alters the nature and accessibility of MC states compared to octahedral complexes. Additionally, the spin state of the complex profoundly influences MC state behavior. In weak ligand fields, high-spin configurations with maximum unpaired electrons are favored, while strong fields favor low-spin complexes with paired electrons [5]. The crossover between these spin states, often triggered by photoexcitation, represents another manifestation of MC state reactivity with significant implications for molecular magnetism and spin-crossover materials.

Table 1: Factors Influencing MC State Energetics in Coordination Complexes

| Factor | Effect on MC States | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Field Strength | Strong fields increase Δo, raising MC state energies | CN⁻ (strong) vs. H₂O (weak) |

| Metal Period | 4d/5d metals have larger Δo than 3d metals | Ru(II) (long-lived MLCT) vs. Fe(II) (ultrafast MC decay) |

| Oxidation State | Higher oxidation states increase Δo | Mn(VII) vs. Mn(II) |

| Coordination Geometry | Different splitting patterns alter MC transitions | Octahedral (Δo) vs. Tetrahedral (Δt ≈ 4/9 Δo) |

| Chelate Effect | Rigid multidentate ligands restrict structural distortion | [Fe(dqp)₂]²⁺ (450 fs) vs. [Fe(bpy)₃]²⁺ (80 fs) |

Experimental Characterization of MC States

Spectroscopic Techniques and Protocols

The identification and characterization of metal-centered excited states relies on a combination of ultrafast spectroscopic methods. Each technique provides complementary information about MC state energetics, dynamics, and structural evolution.

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Protocol: This powerful method tracks the formation and decay of MC states with femtosecond to nanosecond time resolution. The experimental procedure begins with preparing a degassed solution of the complex (typical concentration 0.1-1.0 mM in appropriate solvent) to eliminate oxygen quenching. A femtosecond pump pulse (typically 400-500 nm for polypyridyl complexes) populates initially excited states, while a delayed white light continuum probe pulse monitors spectral changes. MC states are identified by their characteristic excited state absorption (ESA) signatures in the visible to near-IR region, which differ distinctly from MLCT or LMCT features [1]. For iron(II) complexes, MC states typically exhibit broad ESA bands between 500-700 nm, while MLCT states show sharp features associated with reduced ligand signatures. Global fitting analysis of time-resolved spectra yields MC state lifetimes and interconversion kinetics with other excited states.

Time-Resolved Infrared (TRIR) Spectroscopy Protocol: TRIR provides direct structural information about MC states by monitoring metal-ligand vibrational frequencies. The experimental setup involves a pump pulse (as above) synchronized with a tunable IR probe pulse. The sample preparation requires deuterated solvents (e.g., CD₃CN) to avoid overlapping absorptions, and the complex should incorporate ligands with strong IR-active vibrations, such as CO or CN⁻. Upon MC state formation, the decrease in metal-ligand bond order produces characteristic frequency shifts (typically 20-50 cm⁻¹ to lower wavenumbers for carbonyl stretches) [1]. These spectral changes directly evidence the structural reorganization accompanying MC states, with time resolution sufficient to track bond elongation dynamics occurring on femtosecond to picosecond timescales.

Emission and Magnetic Resonance Techniques

While MC states rarely luminesce at room temperature due to efficient non-radiative decay, low-temperature emission studies can provide valuable insights into their electronic structure. Low-Temperature Luminescence Spectroscopy Protocol involves dissolving the complex in a glass-forming solvent mixture (e.g., 4:1 ethanol:methanol) and cooling to 77 K using a liquid nitrogen cryostat. Under these conditions, thermal population of non-radiative decay pathways is suppressed, potentially revealing weak MC emission. The broad, featureless spectra typically observed for MC emission contrast sharply with the structured vibronic progressions characteristic of MLCT or intraligand emission.

Time-Resolved Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (TREPR) Protocol leverages the paramagnetic character of MC states in complexes with unpaired electrons. The experiment requires a photoexcitiable complex in a frozen glassy matrix at low temperatures (10-50 K). Laser excitation within the cavity of an EPR spectrometer generates transient paramagnetic states whose spin polarization patterns and g-anisotropy provide detailed information about electronic configuration and geometric structure. This method is particularly powerful for distinguishing between different spin states (e.g., triplet vs. quintet MC states) and quantifying zero-field splitting parameters that reflect metal-centered electronic redistribution.

Table 2: Experimental Signatures of MC States Compared to Charge Transfer States

| Property | MC States | MLCT States | LMCT States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Intensity | Weak (ε ≈ 10-100 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Strong (ε ≈ 10,000-50,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Variable (often strong) |

| Characteristic ESA | Broad features in 500-700 nm | Sharp ligand radical anion features | Oxidized ligand signatures |

| IR Spectral Shifts | Decreased ν(M-L) frequencies | Minimal change in ν(M-L) | Increased ν(M-L) frequencies |

| Luminescence | Rare at room temperature, weak at 77 K | Often strong with vibronic structure | Typically non-emissive |

| Typical Lifetimes | Femtoseconds to picoseconds | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Femtoseconds to nanoseconds |

| Structural Change | Significant M-L bond elongation | Minimal structural reorganization | M-L bond contraction |

Case Studies and Research Reagents

Representative Complexes and Their MC State Behavior

Specific coordination complexes illustrate the critical role of MC states in determining photophysical properties. The prototypical complex [Fe(bpy)₃]²⁺ (bpy = 2,2'-bipyridine) exhibits ultrafast MLCT→MC conversion within 50-80 femtoseconds, followed by rapid depopulation to the ground state [1]. This behavior stems from the relatively weak ligand field strength of bipyridine toward first-row transition metals, which positions MC states slightly below MLCT states in energy. The small activation barrier (approximately 300 cm⁻¹) facilitates efficient surface crossing, making this complex photophysically inactive despite strong visible light absorption. In contrast, the heteroleptic push-pull Fe(II) complex [Fe(dcpp)(ddpd)]²⁺ (where dcpp is a strongly π-accepting tridentate and ddpd a strongly σ-donating tridentate) features a significantly strengthened ligand field that raises MC state energies [1]. While this design approach has extended MLCT lifetimes in analogous complexes, the MC states remain potent decay channels that limit practical photochemical applications.

Recent innovative strategies have successfully suppressed MC state deactivation pathways. The macrocyclic cage complex [FeCu₂(cage-bpy)]²⁺ incorporates structural rigidity that restricts the metal-ligand bond elongation essential for MC state stabilization [1]. This restriction dramatically extends the MLCT lifetime from 110 femtoseconds in the uncaged analogue to 2.6 picoseconds—representing a 25-fold increase. Similarly, halogenated [Fe(tpy)₂]²⁺ derivatives (tpy = 2,2':6',2''-terpyridine) exploit steric hindrance between substituted ligands to impede the structural distortion toward MC states [1]. Systematic variation of halogen size (F, Cl, Br) progressively increases MLCT lifetimes from 14.0 to 17.4 picoseconds, demonstrating how subtle ligand modifications can modulate MC state accessibility.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying MC States

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Polypyridine Ligands (e.g., bpy, tpy, dqp) | Form photoactive complexes with transition metals | Provide tunable ligand field strengths and rigid coordination environments |

| Strong-Field Ligands (e.g., CN⁻, CO, phosphines) | Increase Δo and raise MC state energies | Test ligand field effects on MC state energetics |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CD₃CN, D₂O) | Medium for spectroscopic studies | Eliminate interfering IR absorptions in TRIR experiments |

| Cryogenic Equipment (liquid N₂ cryostats) | Low-temperature spectroscopy | Suppress thermal decay pathways to reveal MC emission |

| Ultrafast Laser Systems (Ti:Sapphire amplifiers) | Generate femtosecond pump pulses | Time-resolve MC state formation and decay dynamics |

| Oxygen-Scavenging Systems (e.g., glucose oxidase/catalase) | Remove dissolved oxygen from solutions | Prevent excited-state quenching in lifetime measurements |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The complex interplay between electronic states in transition metal complexes can be visualized as energy transfer pathways that determine photophysical behavior. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships and competing decay channels in a typical photoexcited coordination complex.

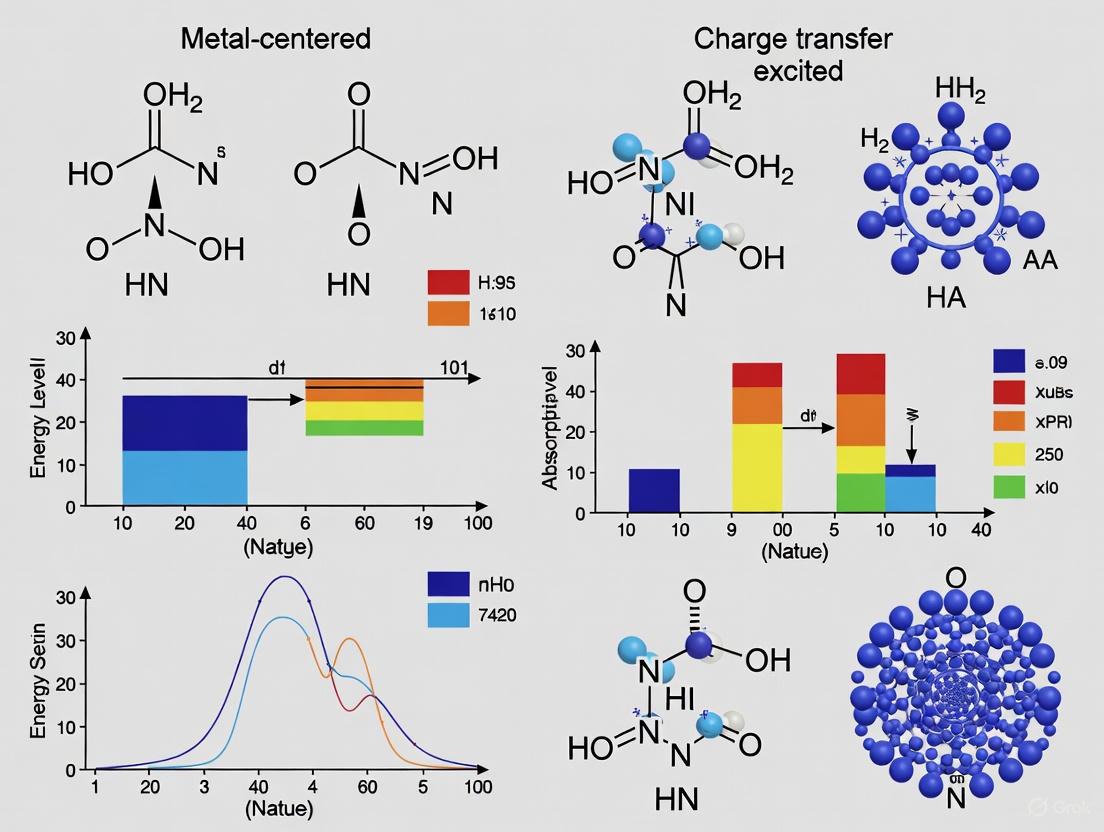

Figure 1: MC State Energy Transfer Pathways. This diagram illustrates the fundamental relaxation pathways following photoexcitation of a transition metal complex. The initial MLCT state undergoes rapid internal conversion to metal-centered states, which typically dominate the deactivation process through non-radiative decay. Strategic suppression of MC states (dashed line) can enable MLCT emission and photochemistry.

The experimental determination of MC state dynamics requires carefully designed workflows that correlate structural changes with electronic evolution. The following diagram outlines a comprehensive protocol for characterizing MC states using transient spectroscopic methods.

Figure 2: MC State Characterization Workflow. This experimental protocol outlines the key steps in identifying and quantifying MC state dynamics using complementary ultrafast spectroscopic techniques. The correlation of transient electronic (ESA) and structural (TRIR) data enables construction of comprehensive kinetic models that distinguish MC-mediated decay from competing charge transfer pathways.

Metal-centered ligand field excited states represent fundamental photophysical phenomena that dictate the behavior of transition metal complexes upon photoexcitation. Their defining characteristics—including weak oscillator strengths, pronounced structural distortions, and role as efficient deactivation channels—differentiate them clearly from charge-transfer states. The strategic suppression of MC states through ligand field manipulation, geometric constraint, and electronic tuning has enabled recent breakthroughs in extending the lifetimes of potentially useful charge-transfer states in first-row transition metal complexes. Future research directions will likely focus on exploiting vibronic coupling effects, designing molecular systems with engineered potential energy surfaces, and developing multi-metallic architectures that spatially separate electronic excitation from metal-centered deactivation pathways. As these strategies mature, the fundamental understanding of MC states will continue to enable new applications in photocatalysis, light-emitting devices, and molecular sensing technologies.

In transition metal photochemistry, charge-transfer (CT) excited states drive most photochemical reactions by redistributing electron density across a molecule upon light absorption, generating a chemical potential capable of initiating diverse reactivity including electron transfer, proton transfer, and bond homolysis [2]. These states are categorized by the direction of electron flow and the molecular orbitals involved. Among them, Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) and Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) represent two fundamental and contrasting processes that dictate the photophysical properties and photoreactivity of coordination complexes [2]. Understanding their distinct characteristics is crucial for designing transition metal complexes for applications ranging from solar energy conversion and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) to targeted drug delivery and photoactivated chemotherapy [6].

The investigation of these states requires sophisticated theoretical and experimental approaches. Modern theoretical methods include static quantum-chemical investigations, mixed quantum-classical molecular dynamics, and full quantum dynamics simulations [7]. For accurate results, methods must incorporate dynamic electronic correlation effects, with coupled-cluster methods like CC2 and algebraic diagrammatic construction (ADC(2)) being preferred for smaller systems, while time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) offers a balance of accuracy and computational cost for larger systems [7].

Fundamental Principles and Electronic Transitions

Orbital Interactions and Electronic Structure

The electronic structures of transition metal complexes are characterized by molecular orbitals with varying degrees of metal or ligand character. In a simplified molecular orbital diagram for an octahedral complex, the key orbitals include predominantly metal-centered d-orbitals (t₂g and e_g* in symmetry) and ligand-based orbitals (σ, π, and π*) [6]. The relative energies and compositions of these orbitals determine the nature of the lowest-energy excited states and the resulting photophysical properties.

- Metal-Centered (MC) States: These involve electronic transitions between orbitals that are predominantly metal-based (e.g., d-d transitions). While not charge-transfer in nature, MC states often compete with CT states in deactivation pathways and can lead to photodecomposition through ligand loss [6].

- Charge-Transfer States: Unlike MC states, CT states involve electron density redistribution between metal and ligand orbitals, creating excited states with significant dipole moments and enhanced redox reactivity [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Charge-Transfer Excited States

| Characteristic | LMCT | MLCT |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Flow | Ligand → Metal | Metal → Ligand |

| Metal Oxidation State | High-valent, electron-deficient | Lower-valent, electron-rich |

| Ligand Requirements | Strong π or σ donors | π-acceptors |

| Typical Energy Range | UV to Visible | Visible to Near-IR |

| Common Examples | [MnO₄]⁻, [IrBr₆]²⁻ | [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, Ir(ppy)₃ |

| Excited State Lifetime | Often ultrafast (fs-ps) | Can be nanosecond to microsecond |

| Primary Applications | Photocatalysis, VLIH | Photosensitization, OLEDs, DSSCs |

Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT)

LMCT transitions occur when light promotes an electron from a ligand-based molecular orbital to a metal-based molecular orbital [2]. These excitations are facilitated by specific electronic structures where transition metal complexes exhibit electron-deficient metal centers paired with strongly donating ligand scaffolds [2]. The electron-deficient metal centers provide vacant low-energy metal-based orbitals, while strong π donor ligands raise the energy of the t₂g orbitals, resulting in small octahedral field splittings ideal for low-energy LMCT transitions [2].

Designing complexes with low-lying LMCT excited states requires careful consideration of four key criteria [2]:

- Excited State Character: The shift in electron density from ligand to metal produces a formally reduced metal center and oxidized ligand(s), dictating properties like excited-state reduction potentials and ligand lability.

- Relative Energetics: LMCT should be the lowest-energy excited state to comply with Kasha's rule, requiring strategic ligand and metal selection to suppress competing d-d transitions.

- Excited State Lifetime: Nanosecond-scale lifetimes are typically required for bimolecular reactions, influenced by factors like spin multiplicity and accessible nonradiative decay pathways.

- Photostability: Ligands must be strongly coordinating and oxidation-resistant to prevent photoreaction from populating metal-ligand antibonding orbitals.

Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT)

In contrast to LMCT, MLCT transitions involve the promotion of an electron from a metal-based orbital to a ligand-based π* orbital [6]. These transitions are characteristic of electron-rich metal centers with low oxidation states coupled with π-acceptor ligands such as 2,2'-bipyridine, 1,10-phenanthroline, or carbonyl [6]. The resulting excited state features a formally oxidized metal center and reduced ligand.

MLCT states have been extensively studied in complexes like [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ due to their attractive properties for photochemical applications [2] [6]:

- Strong absorption in the visible region

- Long-lived excited states (microsecond timescale for [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺)

- Reversible excited-state electron transfer

- Chemical and photochemical stability

The interplay between MLCT and MC states is crucial in determining photophysical behavior. For instance, in Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes, the energy gap between ³MLCT and ³MC states controls the excited-state lifetime and photolability - a smaller gap leads to faster deactivation and reduced photosability [6].

Diagram 1: Fundamental characteristics and relationships between LMCT and MLCT excited states, showing their distinct design principles and shared applications.

Experimental and Computational Characterization Methods

Theoretical Modeling Approaches

Accurate characterization of CT states requires sophisticated theoretical methods capable of modeling excited-state potential energy surfaces and electronic transitions [7].

Static Quantum-Chemical Investigations: This approach focuses on calculating vertical excitation energies, optimized excited-state geometries, and potential energy profiles along reaction coordinates. Typical workflow includes [7]:

- Ground-state geometry optimization and frequency analysis

- Vertical excitation energy calculations

- Excited-state geometry optimization

- Emission energy calculations

- Potential energy surface mapping

Wavefunction-Based Methods: For systems up to 50 heavy atoms, coupled-cluster methods (CC2) and algebraic diagrammatic construction (ADC(2)) provide benchmark accuracy [8] [7]. Spin-component scaled variants (SCS-CC2, SOS-CC2) show improved performance for excited-state potential energy surfaces [7].

Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT): For larger systems, TD-DFT offers favorable scaling but requires careful functional selection to properly describe charge-transfer states and correct state ordering [7].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Charge-Transfer State Characterization

| Method | Accuracy | System Size | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC2/ADC(2) | High | Small (≤50 atoms) | Accurate excitation energies, treatment of double excitations | High computational cost |

| SCS/SOS-CC2 | High | Small (≤50 atoms) | Improved PES description, better for ESIPT | Higher cost than TD-DFT |

| TD-DFT | Moderate | Medium-Large | Favorable scaling, widely available | Charge-transfer state errors, functional-dependent |

| ΔDFT/PCM | Moderate | Large | Good for singlet-triplet gaps, efficient | State-specific, requires validation |

| CASSCF/CASPT2 | Very High | Small | Multireference systems, bond breaking | Extremely high cost, active space selection |

Spectroscopic Techniques

Ultrafast spectroscopic methods provide experimental validation for theoretical predictions and direct observation of CT dynamics:

Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA): Tracks evolution of excited states with sub-picosecond resolution, identifying CT intermediates through characteristic spectral signatures [9]. For example, in host-guest systems, fs-TA confirmed CT-mediated mechanisms by tracking decay of anion and cation radicals on comparable timescales [9].

Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Measures radiative decay pathways and can distinguish between locally excited (LE) and charge-transfer states through solvent-dependent spectral shifts [10]. Dual emission bands are often observed in push-pull compounds, with higher energy emission from LE states and lower energy from ICT processes [10].

Nanosecond Transient Absorption (ns-TA): Probes longer-lived excited states and triplet populations, crucial for characterizing processes like reverse intersystem crossing in TADF emitters [9].

Diagram 2: Integrated computational and experimental workflow for characterizing LMCT and MLCT excited states, showing the cyclic nature of validation and refinement.

Applications in Functional Materials and Devices

Energy Conversion and Storage

Charge-transfer excited states play vital roles in converting solar energy to electrical or chemical energy:

Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells (DSSCs): MLCT states in Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes ([Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺) enable electron injection into semiconductor nanoparticles upon photoexcitation [6]. The long-lived ³MLCT state (∼1 μs) allows sufficient time for bimolecular electron transfer reactions [6].

Solar Fuel Production: LMCT states in high-valent metal complexes can drive photochemical reactions for fuel generation. For instance, LMCT excitation in [MnO₄]⁻ produces O₂ and [MnO₂]⁻, though control of such reactions remains challenging [2].

Photon Upconversion: CT-mediated triplet-triplet annihilation in host-guest systems enables conversion of low-energy to high-energy photons, potentially enhancing solar cell efficiency [9].

Light-Emitting Devices and Display Technology

The unique photophysics of CT states enables advanced luminescent materials:

Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (TADF): Efficient TADF relies on small energy gaps between singlet and triplet CT states (ΔEST) to facilitate reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) [8] [9]. The recently introduced STGABS27 benchmark set provides accurate experimental ΔEST values for TADF emitters, enabling method validation [8].

Organic Room-Temperature Phosphorescence (RTP): Host-guest systems with polyaromatic hydrocarbon guests in benzophenone matrix demonstrate dual TADF and RTP emission mediated by intermolecular charge transfer [9]. The CT state acts as an "energy redistribution hub" promoting both RISC and internal conversion [9].

Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs): Both LMCT and MLCT complexes serve as emitters or hosts in OLEDs. Iridium(III) complexes with mixed MLCT/LC character achieve high efficiency and color purity [6].

Photocatalysis and Synthetic Applications

CT excited states enable numerous photocatalytic transformations:

Visible Light-Induced Homolysis (VLIH): LMCT excitation can trigger metal-ligand bond homolysis, generating radical species for synthetic applications [2]. Design principles include using electron-deficient metals with strongly σ-donating ligands.

Excited State Electron Transfer (ES-ET): Both LMCT and MLCT states can act as potent oxidants or reductants for substrate activation. MLCT states in [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ participate in both oxidative and reductive quenching cycles [6].

Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer (PCET): CT states may initiate concerted proton-electron transfer processes, enabling activation of strong chemical bonds under mild conditions [7].

Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CT State Investigations

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| LMCT Complexes | [MnO₄]⁻, [IrBr₆]²⁻, high-valent Fe(IV)/Mn(III) complexes | LMCT photochemistry benchmark systems, VLIH precursors |

| MLCT Complexes | [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, [Ir(ppy)₃], Re(I) carbonyl diimines | Photosensitizers, standards for long-lived CT states |

| Donor Ligands | Oxo, amido, alkoxides, carbenes, cyclopentadienyl | Strong σ/π donors for LMCT complex design |

| Acceptor Ligands | 2,2'-bipyridine, 1,10-phenanthroline, carbonyl, cyanide | π-acceptors for MLCT complex design |

| Solvent Systems | Acetonitrile, tetrahydrofuran, dichloromethane | Polar solvents for CT state stabilization and characterization |

| Theoretical Methods | CC2, ADC(2), TD-DFT, CASSCF | Electronic structure calculation for CT state prediction |

| Experimental Techniques | Femtosecond TA, time-resolved PL, low-temperature matrix isolation | Direct observation and characterization of CT dynamics |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in understanding and utilizing CT excited states:

LMCT State Lifetime Limitations: Most LMCT states exhibit ultrashort lifetimes (femtosecond to picosecond), limiting their application in bimolecular reactions [2]. Recent efforts focus on extending lifetimes through molecular design, including using second/third-row transition metals with larger ligand field splittings and ligands resistant to oxidation [2].

Theoretical Method Development: Accurate description of CT states remains challenging for TD-DFT, requiring continued development of functionals and linear-response methods [7]. Multireference methods like CASSCF offer accuracy but are computationally prohibitive for most systems [7].

Dual Emission Systems: Materials exhibiting both TADF and RTP through CT mediation represent an emerging frontier [9]. Understanding and controlling the "energy redistribution hub" function of CT states in these systems requires integrated theoretical and experimental approaches [9].

Bioimaging Applications: Nanocrystalline host-guest systems with CT-mediated dual emission show promise for bioimaging, combining high signal-to-noise ratios with tunable emission from green to near-infrared [9].

Future research directions will likely focus on rational design of CT complexes with tailored photophysical properties, leveraging increased computational capabilities and advanced spectroscopic techniques. The integration of machine learning approaches for predicting CT state properties and screening potential complexes offers particular promise for accelerating materials discovery.

As theoretical methods evolve and experimental characterization techniques reach unprecedented temporal and spatial resolution, our understanding of these fundamental excited states will continue to deepen, enabling new technologies for energy conversion, lighting, sensing, and therapy. The distinction between LMCT and MLCT states provides a essential framework for this ongoing exploration at the intersection of inorganic photochemistry and materials science.

The photophysical and photochemical properties of transition metal complexes are fundamentally governed by the nature of their electronically excited states. The concept of "orbital parentage" refers to the primary atomic or molecular orbital origins of an electronic excited state, which dictates its electron distribution, geometric structure, reactivity, and deactivation pathways. Within coordination chemistry, understanding orbital parentage is crucial for designing complexes with tailored excited-state properties for applications ranging from solar energy conversion to photodynamic therapy and photocatalysis. The excited states of transition metal complexes are primarily classified into two broad categories based on their orbital parentage: metal-centered (MC) states and charge-transfer (CT) states, each exhibiting distinct characteristics and behaviors [6].

Metal-centered states, also known as ligand-field states, arise from electronic transitions between molecular orbitals that are predominantly metal d-orbital in character. In contrast, charge-transfer states result from transitions between orbitals primarily localized on the metal and those primarily localized on the ligands. The interplay between these states—their relative energies, lifetimes, and interconversion dynamics—forms a central theme in the photochemistry of coordination compounds [11] [6]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of the key differences between these states, their experimental characterization, and their implications for photofunctional materials design.

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

Metal-Centered (MC) States

Metal-centered (MC) or ligand-field excited states result from promotions of electrons between the d-orbitals of the metal ion that have been split by the ligand field [11]. In an octahedral complex, these correspond to transitions between the t₂g and e_g orbitals. Key characteristics of MC states include:

- Orbital Parentage: Primarily from orbitals of metal d-orbital character [11]

- Spin States: Often involve changes in spin multiplicity, particularly for first-row transition metals [12]

- Structural Impact: Typically cause significant metal-ligand bond elongation due to population of anti-bonding orbitals [6]

- Spectroscopic Features: Appear as weak bands (ε < 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) in UV-visible spectra [11]

MC states are only possible in metal ions with partially filled d-orbitals (d¹ to d⁹ configurations) and cannot occur in d⁰ or d¹⁰ systems [11]. For low-spin d⁶ complexes like Fe(II) polypyridyl complexes, the MC excited state is typically a high-spin quintet state (⁵T₂) reached via ultrafast relaxation from initially populated singlet MLCT states [12].

Charge-Transfer States

Charge-transfer (CT) states involve redistribution of electron density between metal and ligands during the electronic transition. Two primary types exist:

- Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): Electron promotion from molecular orbitals predominantly ligand in character to those predominantly metal in character [11] [13]

- Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): Electron promotion from molecular orbitals predominantly metal in character to those predominantly ligand in character [11]

CT states exhibit markedly different properties from MC states:

- Extinction Coefficients: Feature intense absorptions (ε > 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) [11]

- Solvatochromism: Often exhibit pronounced solvatochromic shifts due to the significant change in dipole moment [13]

- Redox Behavior: Create powerful oxidants and reductants in their excited states [6]

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Electronic Transitions in Transition Metal Complexes

| Parameter | Metal-Centered (MC) | Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) | Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital Parentage | d-d transitions | Ligand-based → Metal d-orbitals | Metal d-orbitals → Ligand π* orbitals |

| Spectral Intensity | Weak (ε < 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Strong | Strong |

| Laporte Allowed | No | Yes | Yes |

| Typical Lifetime | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Nanoseconds to microseconds |

| Structural Impact | Significant bond elongation | Moderate structural changes | Moderate structural changes |

| Redox Activity | Limited | Oxidizing excited state | Reducing excited state |

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Steady-State Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy

Electronic absorption spectroscopy provides initial characterization of electronic transitions. MC transitions typically appear as weak bands in the visible region, while CT transitions are intense and often dominate the spectrum [11].

Protocol for Differentiating Transition Types:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare degassed solutions of the complex in solvents of varying polarity (e.g., acetonitrile, dichloromethane, n-hexane) at concentrations of 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻³ M in quartz cuvettes with 1 cm path length.

- Spectral Acquisition: Record UV-visible spectra from 250 to 800 nm using a dual-beam spectrophotometer.

- Solvatochromism Assessment: Compare band positions across solvents. CT bands typically shift with solvent polarity (negative solvatochromism for MLCT, positive for LMCT), while MC bands remain largely unaffected [13].

- Extinction Coefficient Determination: Measure absorbance at multiple concentrations and apply the Beer-Lambert law to calculate ε. Values >1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ suggest CT character, while weaker bands suggest MC transitions [11].

Time-Resolved Spectroscopic Techniques

Time-resolved methods are essential for elucidating excited-state dynamics and distinguishing short-lived MC states from longer-lived CT states.

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Protocol:

- Excitation Source: Utilize femtosecond or nanosecond laser systems tuned to the MLCT absorption band (typically 400-500 nm for Ru(II), Fe(II), or Ir(III) complexes) [14] [12].

- Probe Configuration: Employ white light continuum generation to probe spectral changes from UV to NIR regions.

- Data Analysis: Global fitting of time-resolved data to extract evolution-associated difference spectra.

- Signature Identification:

For Fe(II) carbene complexes, this technique has revealed the subtle balance between population of triplet metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (³MLCT) and triplet metal-centered (³MC) states, with lifetimes ranging from <300 fs for ³MLCT to ∼10 ps for ³MC states in some complexes [14].

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

Resonance Raman spectroscopy provides vibrational fingerprints of chromophores involved in electronic transitions.

Experimental Protocol:

- Excitation Wavelength Selection: Utilize multiple laser lines across the absorption envelope of interest [15].

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect Raman spectra with resonance enhancement.

- Band Assignment:

- MLCT Transitions: Enhance ligand-centered vibrational modes

- MC Transitions: Enhance metal-ligand vibrational modes

- Excitation Profiles: Plot Raman intensity versus excitation wavelength to confirm assignment.

This technique has proven particularly valuable in bichromophoric systems containing both inorganic and organic chromophores, where it helps identify the nature of the lowest-energy excited state [15].

Orbital Parentage and Excited State Dynamics

The orbital parentage of the lowest-energy excited state fundamentally determines the photophysical and photochemical properties of transition metal complexes. The dynamic interplay between states of different orbital parentage often governs the overall excited-state behavior.

Diagram 1: Excited state relaxation pathways showing competition between MLCT and MC states.

The MLCT-MC Balance in Iron Complexes

The interplay between MLCT and MC states is particularly important in Fe(II) complexes, where the balance between these states determines their utility as photosensitizers:

- Electron-Withdrawing Substituents: Stabilize the ³MLCT state, extending its lifetime to ∼20 ps [14]

- Electron-Donating Substituents: Favor rapid conversion (<300 fs) to ³MC states [14]

- Ligand Field Strength: Stronger ligand fields increase MC state energies, potentially enhancing ³MLCT lifetimes and photoreactivity [12]

Recent investigations of Fe(II) N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) complexes have demonstrated that side-group substitution can switch the dominant excited state between ³MLCT and ³MC character, providing a design strategy for controlling photophysical properties [14].

Implications for Photoredox Catalysis

The orbital parentage of the reactive excited state has profound implications for photoredox catalysis:

- MLCT States: Enable both oxidative and reductive quenching pathways with minimal structural reorganization [12]

- MC States: Often involve significant structural changes and spin-state alterations that impose large reorganization energy barriers [12]

For Fe(II) polypyridyl complexes, electron transfer from the ⁵T₂ MC excited state is subject to significant barriers due to both reorganization energies and spin conservation requirements, undermining its ability to act as an efficient electron donor for photoredox catalysis [12].

Table 2: Reorganization Energies and Spin Considerations in Excited State Electron Transfer

| Excited State Type | Reorganization Energy Barrier | Spin Considerations | Typical Electron Transfer Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLCT (e.g., Ru(II)) | Low (0.2-0.5 eV) | Spin-allowed pathways available | High (kq ~ 10⁹-10¹⁰ M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

| ³MC (e.g., Co(III)) | Moderate | Multiple spin-allowed pathways | Moderate to High |

| ⁵MC (e.g., Fe(II)) | High (0.5-1.0 eV) | Spin-forbidden transitions | Low (kq ~ 10⁷-10⁸ M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

| LMCT | Low to Moderate | Spin-allowed pathways available | High |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Orbital Parentage and Electronic Transitions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (CD₃CN, CD₂Cl₂) | NMR spectroscopy, degassed solutions for photophysics | Low water content, minimal UV absorption |

| Electrochemical Reagents (TBAPF₆) | Supporting electrolyte for cyclic voltammetry | Electrochemically inert, high purity |

| Lewis Base Quenchers (Pyridine, DMSO) | Probing exciplex formation and MC state character | Variable donor numbers for correlation studies [16] |

| Photoinduced Electron Transfer Acceptors (DDQ, Methyl viologen) | Quenching studies to determine excited state redox properties | Well-characterized redox potentials [12] |

| Polypyridyl Ligands (bpy, phen, terpy) | Building blocks for complexes with tunable photophysics | Synthetic versatility, predictable coordination behavior [15] [12] |

| N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands | Strong-field ligands for MC state suppression | High ligand field strength, tunable electronic properties [14] |

The orbital parentage of electronic excited states—whether metal-centered or charge-transfer in origin—serves as a fundamental determinant of photophysical behavior and photoreactivity in transition metal complexes. The distinct characteristics of MC and CT states, including their spectroscopic signatures, lifetimes, redox properties, and structural implications, provide a framework for rational design of photoactive materials. Current research continues to elucidate the subtle interplay between these states, particularly the MLCT-MC balance in first-row transition metal complexes, enabling advances in photoredox catalysis, solar energy conversion, and photoactivated therapeutics. The experimental methodologies and design principles outlined in this review provide researchers with the tools to characterize and manipulate orbital parentage for specific technological applications.

In photochemistry and materials science, the lowest energy excited state of a molecule often governs its observable photophysical behavior and practical applications. This is particularly critical in the development of photoactive coordination complexes based on earth-abundant 3d transition metals, where the competition between metal-centered (MC) and charge transfer (CT) excited states determines photochemical pathways. The pursuit of complexes that supplant precious 4d and 5d elements like Ru, Pt, and Ir has intensified research interest in understanding and controlling these states [17]. In complexes designed for optical applications and photocatalysis, long-lived excited states are essential for enabling bimolecular reactivity not limited by diffusion timescales [17]. The strategic destabilization of low-energy MC states relative to CT states represents a key ligand design strategy, though an alternative approach directly utilizes emissive MC states for applications in sensing and optical devices [17].

Fundamental Principles of State Energetics

The energy gap between electronic states follows fundamental quantum mechanical principles. For nuclei, the energy difference between spin states in NMR spectroscopy is given by the equation E = μ · Bₓ / I, where μ is the magnetic moment, Bₓ is the external magnetic field, and I is the nuclear spin [18]. This energy difference is exceptionally small compared to the average kinetic energy at room temperature, resulting in only a slight population excess in the lower energy state—approximately six nuclei per million in a 2.34 T field [19]. This population imbalance, though minimal, enables spectroscopic observation and is fundamental to understanding energy distribution in molecular systems.

Experimental Probes of Electronic States

Time-Resolved L-Edge X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy

Recent advances in time-resolved L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) have provided unprecedented selectivity for identifying metal-centered excited states. In a 2025 study on Cr(acac)₃, researchers demonstrated this method's sensitivity to the [2]E spin-flip excited state, which has the same (t₂g)³ electron configuration as the [4]A₂ ground state but different spin multiplicity [17].

Experimental Protocol for Time-Resolved Cr L-edge XAS [17]:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve 15 mM Cr(acac)₃ in a 90:10 EtOH:DMSO mixture.

- Photoexcitation: Pump the sample at 343 nm to excite the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) band.

- Time-Resolved Measurement: Probe the Cr 2p XAS spectrum at 75 ps after excitation using synchrotron-based picosecond time-resolved XAS in transmission mode.

- Data Analysis: Compare the ground state and excited state spectra, noting specific features:

- Ground state shows three prominent L₃-edge features at 575.7 eV (A), 576.7 eV (B), and 578.2 eV (C).

- The 2E excited state exhibits a clear excited state absorption feature at 574.5 eV (P′) and characteristic intensity changes in regions A, B, and C.

- Theoretical Validation: Combine measurements with ligand field theory and ab initio calculations to assign spectral changes to intensity redistribution among core-excited multiplets.

This methodology successfully identified purely electronic changes upon excited state formation without significant geometric perturbation, highlighting L-edge XAS as a sub-natural linewidth probe of electronic state identity capable of distinguishing states separated by approximately 0.1 eV despite the 0.27 eV lifetime width of the 2p core-hole [17].

NMR Spectroscopy for Ground-State Analysis

While time-resolved techniques probe excited states, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides essential information about the ground state electronic environment. NMR active nuclei (those with spin I ≠ 0) possess magnetic moments and undergo precession in external magnetic fields at characteristic Larmor frequencies (ω₀ = γB₀, where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio) [19]. The precise resonance frequency of a nucleus depends on its local electronic environment through nuclear shielding—where surrounding electrons reduce the magnetic field experienced by the nucleus [18]. This shielding effect forms the basis of the chemical shift (δ), reported in parts per million (ppm), which provides critical information about molecular structure and electronic distribution [18] [20].

Quantitative Analysis of Excited State Parameters

Table 1: Key Excited State Parameters for Cr(III) Complexes

| Parameter | Symbol | Value for Cr(acac)₃ | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intersystem Crossing Time | ISC | ~100 fs | Ultrafast visible pump-probe [17] |

| Vibrational Cooling | τ_vc | ~7 ps | Transient infrared spectroscopy [17] |

| Back-ISC Time | bISC | ~1 ps | Kinetic modeling [17] |

| Non-radiative Decay | τ_nr | ~800 ps | Transient IR & optical spectroscopy [17] |

| Doublet Yield | Φ_d | 15-30% | Wavelength-dependent measurement [17] |

Table 2: Comparison of Ground and Excited State Spectral Features in Cr L-edge XAS

| State | Feature Label | Energy (eV) | Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground ([4]A₂) | A | 575.7 | 2p → t₂g, 2p → eg (ΔS = 0) |

| B | 576.7 | 2p → eg (ΔS = 0, ±1) | |

| C | 578.2 | 2p → eg + t₂g → eg (ΔS = 0, ±1) | |

| Excited ([2]E) | P′ | 574.6 | 2p → t₂g, 2p → eg (ΔS = 0, +1) |

| A′ | 575.7 | 2p → eg (ΔS = 0, +1) | |

| B′ | 576.8 | 2p → eg (ΔS = 0, +1) | |

| C′ | 578.3 | 2p → eg + t₂g → eg (ΔS = 0, +1) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Instrumentation for Excited State Studies

| Reagent/Instrument | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Cr(acac)₃ | Model complex for studying Cr(III) photophysics; exhibits nested potential energy surfaces [17] |

| EtOH:DMSO (90:10) solvent mixture | Solvent system for time-resolved L-edge XAS studies of Cr complexes in solution [17] |

| Synchrotron X-ray source | Provides tunable, intense X-ray beams for L-edge XAS measurements with picosecond time resolution [17] |

| Fourier Transform NMR Spectrometer | Determines ground state electronic structure through chemical shift analysis [19] [20] |

| Tetramethylsilane (TMS) | Reference compound (δ = 0 ppm) for NMR chemical shift measurements [20] |

| Ultrafast laser systems | Pump-probe excitation for time-resolved studies of electronic state dynamics [17] |

Visualizing Photophysical Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Implications for Drug Discovery and Materials Design

The strategic manipulation of excited state energetics has profound implications for drug discovery and materials science. In molecular property prediction for drug discovery, long-lived MC states enable photocatalytic activity through bimolecular electron or energy transfer mechanisms [17]. The integration of fundamental chemical knowledge through knowledge graph-enhanced molecular contrastive learning (KANO) demonstrates how domain knowledge can guide molecular representation learning for improved property prediction [21]. This approach uses an element-oriented knowledge graph (ElementKG) that incorporates the periodic table and functional group information to provide chemical prior information, addressing the limitations of purely data-driven methods that often lack interpretability and struggle to generalize across the chemical space [21].

The competition between MC and CT states directly impacts photocatalytic efficiency and emissive properties in coordination complexes. By understanding the factors that control the energy ordering of these states—including ligand field strength, metal identity, and molecular geometry—researchers can rationally design complexes with tailored photophysical properties for specific applications including light-emitting devices, photocatalysis, and phototherapeutic agents [17].

The lowest energy excited state serves as a critical determinant of molecular photophysical behavior and practical functionality. Through advanced spectroscopic techniques like time-resolved L-edge XAS, researchers can now directly probe electronic state identities and dynamics with unprecedented specificity. The combination of experimental measurements with theoretical calculations provides a powerful framework for understanding how molecular structure controls excited state ordering and lifetimes. As research continues to elucidate the factors governing MC versus CT state predominance, the rational design of photoactive complexes with tailored properties for specific applications in energy conversion, sensing, and therapy becomes increasingly feasible. The ongoing development of knowledge-enhanced machine learning approaches further promises to accelerate this discovery process by integrating fundamental chemical principles with data-driven modeling.

Impact of Metal Identity, Oxidation State, and Geometry

This technical guide explores the fundamental factors governing the electronic excited state properties of metal complexes, a critical consideration in research areas ranging from photovoltaics to photodynamic therapy. The interplay between metal identity, oxidation state, and molecular geometry dictates the delicate balance between metal-centered (MC) and charge-transfer (CT) excited states. This balance directly determines key photophysical properties, including excited state energy, lifetime, and reactivity. A deep understanding of these relationships enables the rational design of coordination compounds with tailored photophysical behavior for specific scientific and technological applications.

In transition metal complexes, the absorption of light promotes electrons to higher energy states. The character of these excited states falls into two primary categories: Metal-Centered (MC) states and Charge-Transfer (CT) states. MC states involve electronic transitions primarily localized on the metal ion's d-orbitals (e.g., d-d transitions). In contrast, CT states involve the redistribution of electron density between the metal and its surrounding ligands. Charge-transfer states are further classified as Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT), where an electron moves from the metal to a ligand, or Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT), where an electron moves from a ligand to the metal [22].

The practical significance of this distinction is profound. MLCT states are often long-lived and electrochemically active, making them ideal for applications like photocatalysis and light-harvesting. MC states, particularly in first-row transition metals, often lead to rapid non-radiative decay and photoluminescence quenching, which is typically undesirable for photochemical applications [14]. Consequently, a central goal in inorganic photochemistry is to strategically manipulate molecular parameters to favor the population of MLCT states over MC states.

Theoretical Foundations

Metal-Centered (MC) States

Metal-centered states are essentially intramolecular transitions within the metal's d-electron manifold. In a free ion, these d-d transitions are degenerate, but the ligand field created by the surrounding atoms splits the d-orbital energies. The pattern and magnitude of this splitting are dictated by the geometry and identity of the ligands [23]. The population of MC states typically leads to significant structural distortion, as the electron occupancy of orbitals that are antibonding with respect to the metal-ligand bonds is altered. This distortion provides an efficient pathway for vibrational relaxation and non-radiative decay to the ground state, resulting in short excited-state lifetimes.

Charge-Transfer (CT) States

Charge-transfer states are characterized by a spatial separation of charge, creating a transient electric dipole. In an MLCT transition, an electron is promoted from a metal-based d-orbital to a π* antibonding orbital on the ligand. The energy of an MLCT transition can be approximated by the difference between the ionization potential of the metal center and the electron affinity of the ligand, adjusted for solvation and Coulombic terms [22]. The Marcus-Hush theory provides a framework for understanding the kinetics of these electron transfer processes, relating the rate constant to the driving force and reorganization energy [22]. MLCT states are often highly intense in absorption spectra due to their large transition dipole moments and are crucial for applications requiring long-lived excited states for electron transfer or energy transfer reactions.

Core Factors Influencing Excited State Character

Metal Identity

The identity of the metal center is a primary determinant of excited state properties, influencing both the energy and the intrinsic stability of different states.

- d-Electron Configuration: The number of d electrons dictates the available electronic transitions and the ligand field stabilization energy. For instance, iron(II) (d⁶) complexes are notorious for their low-energy MC states that lead to poor photophysical properties, whereas ruthenium(II) (also d⁶) is renowned for its long-lived MLCT state, making it a cornerstone of dye-sensitized solar cell research.

- Ligand Field Strength: The energy of the MC state is directly related to the ligand field splitting parameter (ΔO for octahedral complexes). Heavier second- and third-row transition metals (e.g., Ru, Ir, Pt) exhibit larger ΔO values due to better metal-ligand orbital overlap compared to their first-row counterparts (e.g., Fe, Cu, Cr). A larger ΔO raises the energy of the MC states above that of the MLCT state, thereby destabilizing the destructive MC pathway and favoring a long-lived MLCT state [23].

- Spin-Orbit Coupling: This relativistic effect is significantly stronger in heavier metals. It enhances intersystem crossing from singlet to triplet manifolds, populating triplet MLCT (³MLCT) states that can have orders-of-magnitude longer lifetimes than their singlet counterparts, a key feature for efficient phosphorescent emitters.

Table 1: Impact of Metal Identity on Key Photophysical Parameters

| Metal Ion | d Configuration | Typical Ligand Field (ΔO) | Prominent Excited State | Typical Lifetime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(II) | d⁶ | Weak | MC / MLCT | < 1 ps - 10s ps |

| Ru(II) | d⁶ | Strong | ³MLCT | 100s ns - μs |

| Ir(III) | d⁶ | Very Strong | ³MLCT / ³LC | 100s ns - μs |

| Cu(I) | d¹⁰ | Weak | MLCT / XLCT | ns - 100s ns |

Oxidation State

The metal's oxidation state directly controls the electron count and the relative energies of the frontier molecular orbitals, thereby shifting the equilibrium between MC and CT states.

- Metal Electron Count: A higher oxidation state means fewer d electrons. This can raise the energy required for MC transitions (as it may require promoting an electron into a strongly antibonding orbital) and also modulate the energy of the MLCT state by altering the metal's ionization potential [24] [25].

- Orbital Energy Shifts: As the oxidation state increases, the metal-centered d-orbitals stabilize due to the increased effective nuclear charge. This stabilization lowers the energy of the HOMO (often metal-based) and can raise the LUMO (often ligand-based), thereby increasing the energy of MLCT transitions. Conversely, reduction of the metal center can populate orbitals that are antibonding with respect to the metal-ligand bond, weakening the bond and facilitating population of dissociative MC states [26].

- Case Study - Uranium Oxides: Research on uranium oxides provides a clear example of oxidation-state-dependent electronic structure. Spectroscopic studies can distinguish between U(IV) (5f²), U(V) (5f¹), and U(VI) (5f⁰) configurations based on their characteristic U5f emission multiplet shapes and intensities. The electron count nf decreases with increasing oxidation number, directly altering the electronic spectrum and reactivity [26].

Table 2: Effect of Oxidation State on a Generic Octahedral d⁶ Metal Complex

| Oxidation State | d Electron Count | MC State Energy | MLCT State Energy | Expected Dominant State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +2 | d⁶ | Low | Low | MC (unless ligands create strong field) |

| +3 | d⁵ | Intermediate | High | MLCT / MC Balance |

| +4 | d⁴ | High | Very High | MLCT |

Molecular Geometry

The three-dimensional arrangement of ligands around the metal center, the molecular geometry, imposes symmetry constraints that split the d-orbital energies in a characteristic pattern, fundamentally affecting both MC and CT states.

- Symmetry and d-Orbital Splitting: The geometry (e.g., octahedral, tetrahedral, square planar) determines the specific pattern of d-orbital splitting. For example, in an octahedral field, the dₓ₂₋ᵧ₂ and d_z₂ orbitals are destabilized, while in a tetrahedral field, the splitting is different and smaller in magnitude. This splitting dictates the energy and degeneracy of possible MC transitions [27] [28].

- Ligand Field Stabilization: The geometry influences the ligand field stabilization energy (LFSE). Complexes with high LFSE are more kinetically and thermodynamically stable, which can influence the structural rigidity and the energy barrier for distortion upon photoexcitation. A rigid, high-LFSE geometry can suppress the structural relaxation that leads to MC state deactivation.

- Steric Effects and Ligand Placement: The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) model, extended to coordination complexes, helps predict molecular geometry based on the steric number and the number of lone pairs [27] [28]. The specific arrangement of ligands can create steric hindrance that restricts flattening or other structural distortions in the excited state, thereby prolonging its lifetime. Furthermore, in geometries like trigonal bipyramidal, the choice to place a ligand in an axial versus equatorial position can be determined by the need to minimize lone pair-lone pair repulsions, which indirectly affects the electronic environment around the metal [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Probing the MLCT/MC Balance via Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

This protocol is designed to directly observe and quantify the dynamics between MLCT and MC states, as exemplified by studies on Fe(II) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes [14].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Complex Synthesis: Synthesize the target metal complex (e.g., Fe(II) NHC complex) and purify it to spectroscopic grade using techniques like column chromatography or recrystallization.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a dilute solution (typical optical density ~0.2-0.5 at the excitation wavelength) in a degassed, anhydrous solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, toluene) to prevent quenching by oxygen or water. Use a quartz cuvette with a path length of 2 mm.

2. Data Acquisition:

- Pump Pulse (Excitation): Use a femtosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire amplifier) to generate a pump pulse. The wavelength should be tuned to selectively populate the MLCT state (e.g., 400-550 nm for Fe(II) NHC complexes). The pulse duration is typically <100 fs.

- Probe Pulse (Interrogation): A white-light continuum probe pulse (e.g., 350-800 nm) is generated by focusing a portion of the fundamental laser beam into a sapphire crystal. This probe is delayed relative to the pump pulse using a mechanically controlled optical delay line, enabling measurement from femtoseconds to nanoseconds.

- Detection: The transient absorption (ΔA) signal is recorded as a function of probe wavelength and pump-probe delay time using a CCD spectrometer. This creates a 2D dataset (ΔA vs. λ and time).

3. Data Analysis:

- Global Analysis: Fit the entire dataset to a kinetic model (e.g., consecutive A → B → C) using global analysis software. This extracts the Evolution Associated Difference Spectra (EADS), which represent the spectral components and their lifetimes.

- State Assignment: Assign the EADS to specific electronic states based on their spectral signatures. A sharp, structured signal is often indicative of an MLCT state, while a broad, featureless signal is characteristic of an MC state [14].

- Kinetic Modeling: Determine the time constants for processes such as ¹MLCT → ³MLCT intersystem crossing, ³MLCT → ³MC internal conversion, and ³MC → ground state decay. The lifetime of the ³MLCT state is a key performance metric.

Determining Oxidation State via Photoelectron Spectroscopy

This method quantitatively determines the oxidation state of a metal in a complex, particularly useful for elements like uranium with complex redox chemistry [26].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Film Deposition: For solid samples, prepare a thin, uniform film on a conductive substrate (e.g., Au, Si wafer) via spin-coating, drop-casting, or physical vapor deposition.

- Surface Cleaning: Introduce the sample into an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber (base pressure <1×10⁻⁹ mbar). Clean the sample surface in situ via argon ion sputtering or annealing to remove surface contaminants.

2. Data Acquisition:

- Excitation: Irradiate the sample with a monochromatic X-ray source (e.g., Al Kα at 1486.6 eV for XPS) or UV source (e.g., He I at 21.2 eV for UPS).

- Energy Analysis: Measure the kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons using a hemispherical electron energy analyzer.

- Core-Level and Valence-Band Spectra: Acquire high-resolution spectra of the metal core levels (e.g., U4f for uranium) and the valence band region (including metal 5f states).

3. Data Analysis:

- U5f/U4f Intensity Ratio: Integrate the intensity of the U5f emission (valence band) and the U4f core-level peaks. The U5f/U4f intensity ratio is directly proportional to the 5f electron count (n_f), which decreases with increasing oxidation state (U(IV): n_f=2; U(V): n_f=1; U(VI): n_f=0) [26].

- Spectral Decomposition: Fit the U4f core-level spectrum with multiple components corresponding to different oxidation states (e.g., U(IV), U(V), U(VI)) based on their known binding energy shifts and peak shapes.

- O1s/U4f Intensity Ratio: Calculate the ratio of the O1s peak area to the U4f peak area. This provides an independent measure of the total oxygen concentration and the O/U stoichiometry, corroborating the oxidation state analysis.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Relationship Between Molecular Parameters and Excited States

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the three core molecular parameters and their combined impact on the energetic landscape and dynamics between MC and MLCT states.

Transient Absorption Workflow

This diagram outlines the experimental workflow for performing a transient absorption spectroscopy experiment to track MLCT and MC state dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Investigating Metal Complex Excited States

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Ligands | Strong-field ligands to increase ligand field splitting (ΔO) and stabilize MLCT states against MC states. | Fe(II) NHC complexes with electron-withdrawing side groups (e.g., -COOH) to tune MLCT energy [14]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Used for NMR spectroscopy and for preparing samples for ultrafast spectroscopy to minimize interfering C-H vibrational overtones. | Deuterated acetonitrile (CD₃CN). |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) System | Essential for surface-sensitive techniques like XPS/UPS to measure oxidation states and electron counts without atmospheric contamination. | System for analyzing UO₂ thin film oxidation [26]. |

| Femtosecond Laser System | The excitation source for transient absorption spectroscopy to generate pump and probe pulses for tracking ultrafast dynamics (fs to ns). | Ti:Sapphire amplified laser system. |

| Hemispherical Electron Analyzer | The core detector in XPS/UPS systems that measures the kinetic energy of photoelectrons with high resolution. | Used for resolving U4f and U5f electronic states [26]. |

| Chemical Oxidants/Reductants | To systematically vary the metal oxidation state in situ for spectroscopic study. | Atomic oxygen (O) and atomic hydrogen (H) for controlled UO₂ oxidation and UO₃ reduction [26]. |

The photophysical destiny of a transition metal complex is not governed by chance but is a direct and tunable consequence of metal identity, oxidation state, and molecular geometry. The strategic manipulation of these parameters allows researchers to steer the delicate balance between metal-centered and charge-transfer excited states. The experimental and theoretical toolkit outlined in this guide provides a roadmap for the rational design of next-generation coordination compounds. By leveraging strong-field ligands, optimal metals, and rigid geometric structures to maximize the ligand field splitting and stabilize the MLCT state, scientists can develop new materials with tailored photophysical properties for advanced applications in lighting, sensing, catalysis, and therapy.

Harnessing Excited-State Reactivity for Phototherapeutics and Devices

Photoactivatable metallodrugs represent a cutting-edge class of therapeutic agents that remain relatively inactive until triggered by light, enabling precise spatiotemporal control over drug activity. This activation mechanism offers the prospect of novel pharmaceuticals with reduced side effects and innovative mechanisms of action to combat resistance to current therapies [29]. The fundamental principle involves using light to excite metal complexes, leading to the generation of cytotoxic species through various photophysical processes. These metallodrugs are strategically designed to be activated at specific wavelengths, allowing targeted treatment of diseased tissues while minimizing damage to healthy surrounding areas. Their development sits at the intersection of inorganic chemistry, photophysics, and medicine, creating opportunities for more selective and effective cancer and anti-infective treatments [29] [30].

The field has evolved significantly from first-generation platinum-based chemotherapeutics to sophisticated complexes incorporating ruthenium, iridium, gold, and other transition metals. A key research frontier in this domain involves understanding and manipulating the excited state properties of these complexes, particularly the interplay between metal-centered (MC) and charge-transfer states [6]. This understanding forms the basis for rational drug design, enabling scientists to tailor photophysical properties for specific therapeutic applications. The clinical potential of these agents is primarily realized through three main modalities: Photodynamic Therapy (PDT), Photoactivated Chemotherapy (PACT), and Photothermal Therapy (PTT), each with distinct mechanisms of action and applications [29].

Fundamental Excited State Mechanisms

The photophysical behavior of transition metal complexes is governed by their excited state dynamics, which determine their suitability for specific therapeutic applications. Upon light absorption, these complexes populate various excited states, with the nature of the lowest-energy excited state dictating their primary photochemical pathways and biological activity [6].

Metal-Centered (MC) Excited States

Metal-centered (MC) or ligand field excited states involve the promotion of an electron from a metal-based t₂g orbital to an eg orbital. These states are typically dissociative in nature, leading to ligand loss or exchange reactions. In octahedral d⁶ complexes, MC states often involve significant structural reorganization and bond elongation, making them key players in Photoactivated Chemotherapy (PACT) applications [6]. The energy gap between the MC states and the ground state is influenced by the ligand field strength, with stronger field ligands resulting in higher-energy MC states. For first-row transition metals with weaker ligand fields, low-lying MC states often dominate the excited-state landscape and govern photoreactivity [12].

Charge Transfer States

Charge transfer states involve electron redistribution between metal and ligand orbitals and come in several varieties:

Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): These states involve electron transfer from metal-based orbitals to ligand-based π* orbitals. MLCT states are typically characterized by intense absorption in the visible region and are crucial for Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) applications, as they can efficiently sensitize oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6] [31]. The relatively long lifetimes of triplet MLCT (³MLCT) states in precious metal complexes like Ru(II) and Ir(III) make them particularly effective for this purpose [31].

Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): In these states, electron density moves from ligand-centered orbitals to metal-based orbitals, often leading to ligand oxidation and metal reduction.

Ligand-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (LLCT): These involve electron transfer between different ligands within the same complex.

The relative energies of these excited states determine the photophysical and photochemical properties of the complex. For instance, in Ru(II) and Ir(III) polypyridyl complexes, MLCT states typically lie lower in energy than MC states due to strong ligand fields, while the reverse is often true for first-row transition metals [12].

Therapeutic Modalities

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic Therapy utilizes photosensitizers that, upon light activation, transfer energy to molecular oxygen, generating cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) that induce cell death [32]. Metal complexes serve as excellent photosensitizers due to their tunable photophysical properties, including strong visible light absorption, long-lived triplet excited states, and efficient intersystem crossing [33].

The cytotoxic ROS generated in PDT, particularly singlet oxygen (¹O₂), damage crucial cellular components including lipids, proteins, and DNA, disrupting cellular redox homeostasis and triggering various cell death pathways [32]. While PDT-induced cell death was traditionally attributed to apoptosis, necrosis, or autophagy, recent research has revealed it can trigger a broader range of unconventional cell death pathways, including ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis [32].

Next-generation photosensitizers based on iridium (Ir), ruthenium (Ru), and rhenium (Re) complexes offer significant advantages, including deep tissue penetration, enhanced photostability, and tunable ROS production [32]. The incorporation of these metal complexes into PDT regimens has revolutionary potential for improving cancer treatment precision and overcoming therapeutic resistance.

Photoactivated Chemotherapy (PACT)

Photoactivated Chemotherapy involves light-triggered activation of inert metal complexes to release cytotoxic ligands or generate active species that damage cellular components [29]. Unlike PDT, PACT does not rely on oxygen and is therefore effective in hypoxic tumor environments where traditional PDT fails.

PACT agents are classified into several categories based on their activation mechanisms:

Photorelease Agents: These complexes undergo photoinduced ligand dissociation, releasing bioactive ligands such as chemotherapy drugs or carbon monoxide [29] [6].

Ligand-Activated Agents: These complexes become activated through photochemical modifications to their coordination sphere [29].

Photoinduced Oxidation/Reduction Agents: These complexes undergo photoredox processes that enhance their cytotoxicity [29].

The selectivity of PACT arises from spatial control of illumination, allowing precise activation of the prodrug only in the tumor region, thereby minimizing systemic toxicity [29].

Photothermal Therapy (PTT)

Photothermal Therapy utilizes light-absorbing agents to convert photon energy into heat, inducing localized hyperthermia that ablates cancer cells [34]. Metal complexes and metallopolymer nanoparticles (MPNs) are particularly effective for PTT due to their strong absorption cross-sections and efficient non-radiative relaxation pathways.

Upon light absorption, the excited complexes return to the ground state primarily through non-radiative decay, converting light energy into thermal energy. This localized heating denatures proteins, disrupts membrane integrity, and can induce coagulative necrosis in tumor tissues [34]. The photothermal conversion efficiency depends on factors including the metal center, ligand structure, and aggregation state of the complex.

Recent advances have focused on developing metallopolymer nanoparticles that combine strong photothermal properties with enhanced tumor accumulation through the Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR) effect [34]. These nanoconstructs can also be designed for multimodal therapy, combining PTT with other treatment modalities such as PDT or chemotherapy.

Table 1: Comparison of Photoactivatable Therapy Mechanisms

| Therapy Type | Activation Mechanism | Primary Cytotoxic Species | Oxygen Dependence | Key Metal Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDT | Photosensitizer excitation followed by energy transfer to oxygen | Reactive oxygen species (ROS) | Yes | Ru(II), Ir(III), Zn(II) porphyrins, Pt(II) |

| PACT | Photoinduced ligand dissociation or activation | Released ligands or activated metal complexes | No | Pt(IV), Ru(II), Co(III) |

| PTT | Non-radiative relaxation of excited states | Heat | No | Au, Pt, metallopolymer nanoparticles |

Key Metal Complexes and Their Properties

Platinum Complexes