Mastering FIB Sample Preparation for In Situ TEM Nanomaterial Characterization: A Guide from Foundations to Future Directions

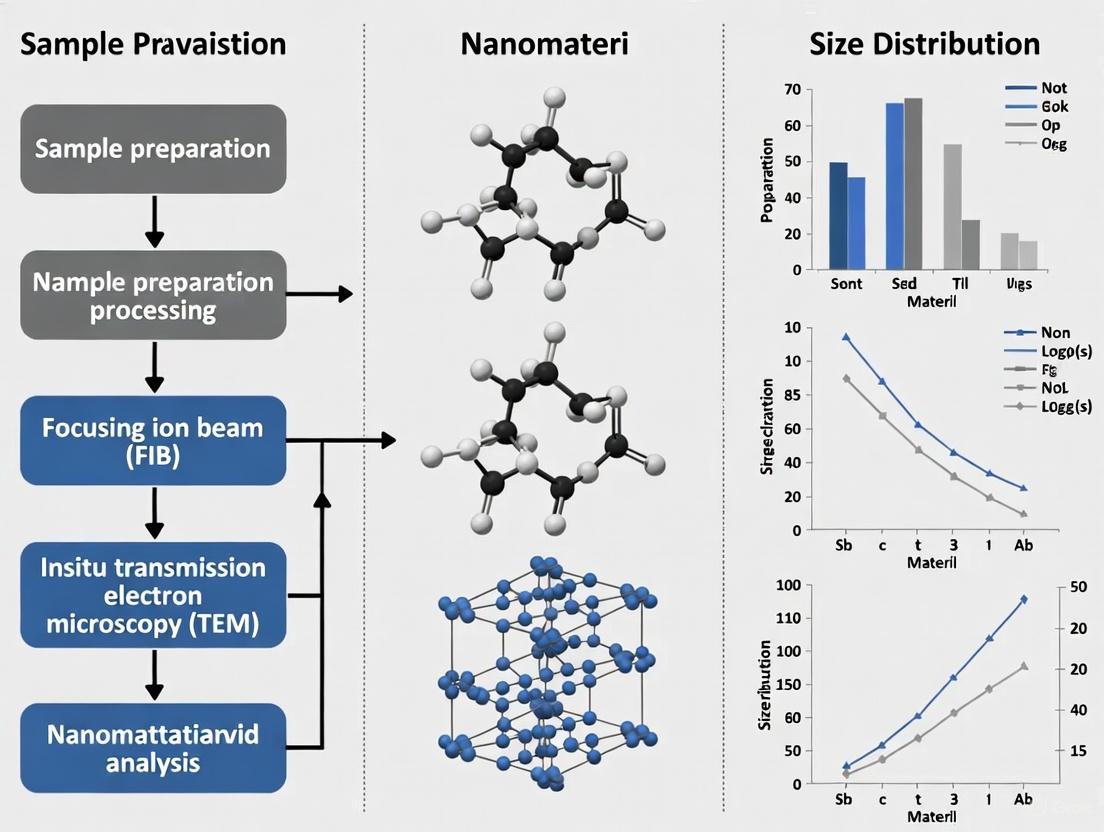

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Focused Ion Beam (FIB) sample preparation for in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), a powerful technique for real-time nanomaterial characterization.

Mastering FIB Sample Preparation for In Situ TEM Nanomaterial Characterization: A Guide from Foundations to Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Focused Ion Beam (FIB) sample preparation for in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), a powerful technique for real-time nanomaterial characterization. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it covers foundational principles, detailed methodologies for various nanomaterials, advanced troubleshooting for common artifacts, and rigorous validation protocols. By integrating insights from both academia and industry, this resource aims to enhance the reproducibility and reliability of in situ TEM experiments, ultimately accelerating innovation in fields ranging from semiconductor development to nanomedicine.

The Critical Role of FIB in Bridging Nanoscale Imaging and Real-World Material Behavior

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of in situ TEM over conventional TEM for nanomaterial characterization? In situ TEM overcomes the limitations of conventional, static characterization by enabling the real-time observation and analysis of dynamic processes—such as nanomaterial growth, phase transformations, and defect dynamics—at the atomic scale under various microenvironmental conditions (e.g., liquid, gas, solid, or under applied stress). This provides an unparalleled view into synthesis pathways and functional mechanisms [1] [2] [3].

Q2: What common artifacts are introduced by FIB sample preparation, and how can they be addressed? FIB preparation is essential for site-specific samples but can introduce artifacts that complicate analysis. Key artifacts and a proven solution are listed below [4]:

| Artifact Type | Description | Potential Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Subsurface Black Spots | Clusters of vacancies and/or interstitials. | Can obscure or be mistaken for intrinsic radiation damage. |

| Surface Dislocations | Dislocations introduced at the sample surface. | May interact with pre-existing defects, altering observed mechanical properties. |

| Moiré Fringes | Interference patterns from overlapping layers. | Can mask genuine material features and strain fields. |

| Amorphous Layers | Loss of crystallinity at the sample surface. | Reduces image resolution and can interfere with chemical analysis. |

Solution: Flash Electropolishing (FEP) has been proven to effectively remove these FIB-induced subsurface and surface artifacts, producing TEM samples from metallic systems like Fe-Cr alloys that are comparable in quality to traditionally jet-polished samples [4].

Q3: What key factors should I consider when designing an in situ TEM experiment? A successful experiment requires careful planning across several fronts [3]:

- Stimulus and Environment: Choose holders or microscope configurations that provide the correct stimulus (heating, biasing, liquid/gas environment, mechanical stress) for the process you want to study.

- Sample Design: The specimen geometry must be compatible with both the stimulus and the required data. Use site-specific techniques like FIB lift-out to access defined interfaces or features.

- Beam Effects: Be aware that the electron beam itself can interact with the sample, potentially inducing reactions, heating, or damage. This interaction may be enhanced by the applied stimulus.

- Data Acquisition: Balance the need for temporal resolution with signal-to-noise ratio. Higher frame rates often mean lower resolution or increased electron dose.

Q4: My in situ TEM videos are noisy. How can I improve the temporal resolution without sacrificing too much spatial detail? Temporal resolution is primarily limited by the camera and electron source [2]. To improve it:

- Use Direct Detection Cameras: These modern cameras have higher detection quantum efficiency (DQE) and can achieve frame rates of hundreds to thousands of frames per second.

- Optimize Electron Dose: The Rose criterion dictates that a higher electron dose is needed for better signal-to-noise at a given resolution. You must find a balance where the dose is high enough to maintain usable image quality at your desired frame rate.

- Consider Specialist Instruments: For studying ultrafast, reversible processes, ultrafast TEM techniques using pulsed electron sources can achieve nanosecond to femtosecond temporal resolution [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unclear Dynamic Process During Nanomaterial Growth

Problem: Difficulty in visualizing the atomic-scale dynamic processes, such as nucleation or phase evolution, in real-time.

Solution: Utilize specialized sample holders that create the necessary microenvironment.

- For Liquid-Phase Reactions (e.g., nanoparticle growth from solution, battery cycling): Use windowed liquid cells. These sealed cells allow you to introduce a thin layer of liquid between electron-transparent windows, enabling the observation of materials in their native liquid environment [2] [3].

- For Gas-Solid Interactions (e.g., catalysis, oxidation): Use windowed gas cells or an Environmental TEM (ETEM). ETEMs are specially modified to maintain a controlled gas pressure around the sample, allowing direct observation of reactions in gaseous atmospheres [2].

- Protocol: Follow the workflow in the diagram below to set up and execute your experiment.

Issue 2: Preparing a Site-Specific TEM Sample from a Device or Coating

Problem: Need to prepare an electron-transparent sample from a specific, buried feature (e.g., an interface in a multilayer device or a coating on a substrate).

Solution: Use the Focused Ion Beam (FIB) Lift-Out technique.

- Protocol:

- Deposit Protective Layer: Use an electron-beam and then an ion-beam deposited protective coating (e.g., Pt or C) to preserve the region of interest from ion damage during milling.

- Trench and Undercut: Use the FIB to mill trenches on both sides of the feature of interest, then undercut the bottom to create a thin "lamella" still attached to the bulk.

- Lift-Out: Use a nanomanipulator (microneedle) to weld to the lamella, cut it free, and transport it to a TEM grid.

- Weld and Thin: Attach the lamella to the grid and use lower-energy ion beams to thin it to electron transparency (typically <100 nm).

- Final Cleaning (Critical): To remove the amorphous layer and subsurface damage created by the Ga+ ion beam, perform a final, low-energy (≤ 2 kV) polish. For metallic samples, Flash Electropolishing is a highly effective method for removing these artifacts [4].

Issue 3: Artifacts Obscuring True Microstructure in FIB-Prepared Samples

Problem: After FIB preparation, the sample's microstructure is obscured by moiré fringes, surface dislocations, or amorphous layers, making it difficult to distinguish preparation damage from intrinsic material features.

Solution: Implement a post-FIB cleaning procedure and be aware of the artifacts during analysis.

- Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow: Follow the logic in this diagram to identify and mitigate common FIB artifacts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in In Situ TEM | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based Holders | Micro-Electro-Mechanical-System devices integrated into holders for applying heat, electrical bias, or mechanical stress with high precision [2]. | Enable quantitative in situ testing (e.g., stress-strain data) alongside imaging. |

| Windowed Liquid/Gas Cells | Specially designed holders that use electron-transparent windows (e.g., SiN(_x)) to encapsulate samples in liquid or gas environments [2] [3]. | Window thickness limits spatial resolution; pressure/concentration in cells differs from bulk conditions. |

| Focused Ion Beam (FIB) | A standard tool for site-specific TEM sample preparation via lift-out, crucial for analyzing buried interfaces [4] [3]. | Inherently introduces artifacts (see FAQ #2); requires post-processing cleaning. |

| Flash Electropolishing (FEP) | An electrochemical method for the final thinning and cleaning of FIB-prepared TEM lamellae, particularly for metallic samples [4]. | Effectively removes FIB-induced surface and subsurface damage, revealing the true microstructure. |

| Direct Electron Detectors | High-speed cameras that detect electrons directly without intermediary conversion, offering high detection quantum efficiency and fast frame rates [2]. | Critical for high-temporal-resolution experiments and reducing electron dose for beam-sensitive materials. |

Why FIB is Indispensable for Preparing Site-Specific and Electron-Transparent Samples

Troubleshooting Guides

Common FIB Preparation Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common FIB Preparation Issues

| Problem | Causes | Solutions & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Breaks Apart [5] | Loosely bound composite materials (e.g., solid-state battery components); Brittle samples; Excessive milling force. | Use a "Depo-all-around" technique: create a protective frame of deposited material around the region of interest to hold it together during milling [5]. |

| Curtaining/ Milling Artefacts [6] | Different materials mill at different rates; Surface topography, voids, or cracks. | Optimize milling direction: Re-orient the sample so that a uniform layer mills first. Use sample inversion techniques to mill softer materials before harder ones [6]. |

| Ion Beam Damage [6] [7] [8] | High-energy Ga+ ion implantation; Sample amorphization (surface non-crystallinity); Gallium contamination. | Lift-out normal to the ion beam to avoid direct imaging of the cross-section [6]. Use a final low-energy polish (e.g., ≤ 500 V or 1-5 kV) to remove the damaged layer [9] [10]. Consider plasma FIB (using Xe or Ar) for Ga-free preparation [10]. |

| Uncertain Lamella Thickness [6] | Inexperience; Lack of precise feedback during thinning. | Use Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) thickness measurement techniques (e.g., AZtec LayerProbe) to quantify thickness and Ga implantation before TEM analysis [6]. |

| Sample Contamination [9] | Hydrocarbon or moisture deposition from air exposure; Redeposition of sputtered material. | Use plasma cleaning before analysis. Employ vacuum transfer holders (e.g., TEM-Linkage) to move lamellae from FIB to TEM without air exposure [9]. |

Advanced Technique: The "Depo-all-Around" Workflow for Fragile Composites

For loosely bound samples like solid-state battery composites (e.g., NCM cathode and LLZO electrolyte interfaces), a conventional FIB routine often causes disintegration. The following diagram illustrates a novel procedure to mitigate this.

Experimental Protocol:

- Application: Ideal for preparing TEM lamellae from brittle, multi-material, or porous composites where interfacial integrity is critical, such as in battery or catalyst research [5].

- Key Steps:

- Site Protection: Use the Gas Injection System (GIS) to deposit a standard protective layer (e.g., Platinum or Carbon) over the specific site of interest (e.g., a solid electrolyte | cathode interface) [5] [9].

- Frame Deposition: Extend this deposition to create a reinforcing frame that fully surrounds the area targeted for the lamella. This frame acts as a support scaffold, preventing the loosely bound internal material from breaking apart during subsequent milling steps [5].

- Milling and Lift-Out: Proceed with standard FIB-SEM milling routines—coarse milling, undercutting, lift-out with a nanomanipulator, and welding to a TEM grid—while the sample is stabilized by the frame [5] [9].

- Final Thinning: Carefully thin the lamella to electron transparency. The frame ensures the structural integrity of the lamella is maintained throughout this process [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I just use broad ion beam (BIB) polishing for all my TEM sample preparation? A: While BIB is excellent for creating large, uniform, damage-free surfaces over millimeter-scale areas, it lacks the site-specific precision of FIB. FIB allows you to target a specific grain boundary, a single nanoparticle in a catalyst, or a particular transistor in a semiconductor device with nanometer-scale accuracy, which is often the core requirement for advanced materials research [8].

Q2: How thin does a FIB-prepared lamella need to be for (S)TEM analysis? A: The required thickness depends on the material and the accelerating voltage of the TEM, but for high-resolution (HR)TEM or atomic-scale analysis, lamellae are typically thinned to below 100 nm, with final thicknesses often reaching ~30-50 nm [9] [11]. A final low-kV polish is used to achieve this and remove surface damage [9].

Q3: What is the difference between in-situ and ex-situ lift-out? A: In-situ lift-out is the standard method, where a micromanipulator needle inside the FIB-SEM chamber is used to extract, transfer, and mount the lamella onto a TEM grid all under vacuum. This minimizes contamination and is highly precise. Ex-situ lift-out involves removing the sample from the chamber after milling for manual manipulation, a method that is largely obsolete and carries a high risk of contamination or loss [9].

Q4: My sample is gallium-sensitive. Are there alternatives to the Ga+ focused ion beam? A: Yes. Plasma FIB (PFIB) systems are increasingly common. They use ions from a Xe or Ar plasma source, which are much heavier than Ga and allow for high-current, high-speed milling without Ga implantation. This is particularly beneficial for preparing high-quality samples for sensitive analyses like EELS [11] [10].

Q5: How can I accurately determine when my lamella is thin enough, before transferring to the TEM? A: Besides standard SEM imaging, advanced techniques like Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) can be used. For example, AZtec LayerProbe can quantify lamella thickness, measure the extent of Ga implantation, and detect redeposited material, removing the guesswork from the thinning process [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials & Equipment

Table 2: Key Reagents and Equipment for FIB Sample Preparation

| Item | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Gas Injection System (GIS) | Injects precursor gases for ion- or electron-beam induced deposition. Used to deposit protective layers (e.g., Pt, C) over the area of interest to shield it from ion damage during initial milling, and to create weld points for the manipulator probe during lift-out [5] [9]. |

| Nanomanipulator (e.g., OmniProbe) | A fine, precise robotic needle used inside the FIB-SEM chamber to perform the in-situ lift-out procedure. It attaches to, lifts, transfers, and places the lamella onto a TEM grid [6] [9]. |

| TEM Grid Holder | Specialized holders (e.g., OmniPivot) that allow for precise orientation and pivoting of the TEM grid during the lamella mounting process without direct handling, enabling optimal sample inversion to reduce curtaining [6]. |

| Plasma Cleaner | Used to remove hydrocarbon contamination from the sample surface after preparation and before loading into the TEM. This prevents the contamination from volatilizing and depositing on the lamella under the electron beam, which degrades image quality [9]. |

Standard FIB-SEM Workflow for TEM Lamella Preparation

The following diagram outlines the universal, step-by-step workflow for creating a site-specific, electron-transparent sample using a DualBeam FIB-SEM, integrating solutions to common challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the most common cause of poor-quality TEM images from FIB-prepared samples, and how can it be mitigated? Ion beam-induced damage is a prevalent issue. During FIB milling, high-energy ions can implant into the sample or create an amorphous surface layer, obscuring the true material structure and compromising analytical results [9]. This damage can be minimized by applying a final low-energy (e.g., 500 V) polish after the initial milling to remove the damaged layer [10]. For extremely sensitive materials, using a plasma FIB (PFIB) with xenon or argon ions instead of a traditional gallium source can also reduce damage [10].

FAQ 2: How can I ensure my TEM sample is representative of the bulk material's properties? A key strategy is to use a multiscale workflow. Start with techniques like microCT to visualize the bulk sample and identify regions of interest (ROIs) [10]. Then, use the FIB-SEM's precise site-specific sampling capability to extract a lamella from that exact ROI [9]. This ensures the analyzed nanoscale volume is directly linked to a specific feature or property observed in the bulk material, thereby creating a reliable correlation.

FAQ 3: My in situ TEM experiment requires a specific sample geometry. What tools can help with precise deposition? For experiments using specialized chips (E-chips), a shadow mask is an essential tool. It allows for precise patterning and deposition of materials (via liquid drop-casting, dry powder deposition, or sputter coating) exclusively onto the thin silicon nitride windows of the chip, ensuring a clean experiment and good electrical contact [12]. For FIB-prepared lamellae that need to be transferred to these chips, a dedicated FIB stub facilitates the nuanced transfer process [12].

FAQ 4: How can I verify my sample preparation was successful before starting a complex in situ TEM experiment? An inspection holder is designed for this purpose. It allows you to load your prepared sample chip into a TEM to screen the deposition quality, thickness, and overall condition before assembling it into an in situ holder (e.g., for liquid or gas experiments). This step can save significant time and resources by identifying preparation issues early and allows for pre-experiment high-resolution analysis [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Sample Contamination

Contamination, such as hydrocarbons or moisture, can deposit on the sample in the TEM vacuum, masking real features [9].

- Prevention: Implement careful handling and use plasma cleaning on samples before insertion into the microscope [9].

- Solution: For FIB-SEM workflows, use a system that allows for direct transfer of the prepared lamella to the TEM (e.g., via a transfer holder) without exposure to air [9].

Challenge: Artifacts in Biological or Soft Materials

Staining biological samples with heavy metals can introduce artifacts that obscure genuine structures [13].

- Prevention & Solution: Consider cryo-preservation as an alternative. Rapid freezing (vitrification) preserves samples in their native state with minimal chemical alteration and is often combined with cryo-FIB milling for life science applications [9] [13].

Challenge: Inhomogeneous Strain Analysis

As demonstrated in InAs nanowire studies, mechanical strain can distribute unevenly at the nanoscale, which can reverse the expected effect on electrical conductivity by increasing charge carrier scattering [14].

- Solution: Employ in situ TEM electromechanical testing combined with nanoscale strain mapping techniques like Nanobeam Electron Diffraction (NBED). This allows for the simultaneous measurement of electrical properties and quantitative mapping of strain distribution with high spatial resolution, providing a direct correlation [14].

Challenge: Preparing a Lamella from a Specific Nanoparticle or Defect

Isolating a specific nanoscale feature (e.g., a single nanoparticle in an optical fiber) for TEM analysis is challenging [15].

- Solution: Use the FIB-SEM's dual-beam capability.

- Use SEM imaging to locate the area of interest [9].

- Deposit a protective layer (e.g., platinum or carbon) over the site to shield it during ion milling [9] [15].

- Use the FIB to mill away surrounding material, isolating a thin lamella that contains the feature of interest [9] [15]. The site-specificity of FIB-SEM is indispensable for this task [9].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Standard FIB-SEM Workflow for TEM Lamella Preparation

The following table outlines a typical workflow for preparing an electron-transparent sample using a DualBeam FIB-SEM [9].

Table 1: Step-by-Step FIB-SEM TEM Sample Preparation Protocol

| Step | Description | Key Parameters & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Site Selection & Protection | Use SEM imaging to locate the specific feature of interest. Deposit a protective layer (often Pt or C) over the site. | The protective layer prevents damage and rounding of the top surface during milling [9]. |

| 2. Coarse Milling | Use the FIB to mill trenches in front of and behind the protected site, creating a thin slab (lamella) still attached to the bulk for support. | Use a relatively high beam current for rapid material removal [9]. |

| 3. Lift-Out & Mounting | Use a nanomanipulator probe (welded with ion-beam-deposited Pt) to cut the lamella free, lift it out, and weld it onto a TEM grid. | Ensure a strong weld to the grid to ensure mechanical stability [9]. |

| 4. Final Thinning & Polishing | Thin the mounted lamella from both sides to achieve electron transparency (typically <100 nm). | Use progressively lower beam currents. A final low-kV polish (e.g., 500 V - 5 kV) is critical to remove the FIB-damaged layer [9] [10]. |

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Protocol 2: In Situ TEM Electromechanical Testing and Strain Mapping

This protocol is based on research that directly correlated nanoscale strain with electrical transport properties in InAs nanowires [14].

Table 2: Protocol for Correlating Electrical Transport and Lattice Strain

| Step | Description | Key Techniques & Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Preparation & Mounting | Passivate nanowires (e.g., with an InGaAs shell) to reduce surface effects. Transfer a single nanowire onto a MEMS-based electromechanical testing device (e.g., push-to-pull device). | Core-shell nanowire growth; Nano-manipulation [14]. |

| 2. In Situ Setup | Integrate the MEMS device into a TEM holder capable of applying mechanical force and conducting electrical measurements. | In situ TEM nanoindenter holder with electrical contacts [14]. |

| 3. Simultaneous Data Acquisition | Apply tensile stress while simultaneously measuring:• Force & Displacement: From the nanoindenter.• Electrical Conductivity: Through the circuit.• Lattice Strain: Acquire NBED patterns at each stress level. | Nanoindenter; Pico-ammeter; Scanning TEM (STEM) with NBED [14]. |

| 4. Data Correlation & Analysis | Calculate stress from force and geometry. Create 2D strain maps (εxx, εyy) from NBED patterns. Correlate average strain with changes in electrical conductivity. | Quantitative stress/strain analysis; Nanobeam Electron Diffraction (NBED); Data visualization software [14]. |

The following flowchart helps troubleshoot the interpretation of electromechanical data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for FIB-SEM and In Situ TEM Experiments

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Gas Injection System (GIS) | Allows for FIB-induced deposition (FIBID) of protective layers (e.g., Pt, C) or insulator materials, and for FIB-enhanced etching with specific gases [16]. |

| Protective Coating (Pt/C) | A metal-organic gas (e.g., precursor for Pt) is injected and decomposed by the ion or electron beam to deposit a protective layer that preserves the top of the sample during FIB milling [9] [15]. |

| Liquid Cell E-Chip | For in situ liquid TEM, these chips contain microfabricated silicon nitride windows to encapsulate a liquid environment, allowing observation of materials in their native solution [12]. |

| MEMS-based Testing Devices | These tiny mechanical devices (e.g., push-to-pull, heating, or biasing chips) enable the application of stress, heat, or electrical bias to a sample inside the TEM while observing its response [14] [12]. |

| Plasma FIB Source (Xe, Ar) | An alternative to Ga+ ions, a Xenon Plasma FIB (PFIB) allows for much faster milling rates and larger volumes, and reduces damage for certain materials, enabling gallium-free sample preparation [16] [10]. |

Quantitative Data from Nanoscale Characterization

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research that successfully bridged nanoscale characterization with bulk properties.

Table 4: Correlation of Nanoscale Strain and Electrical Properties in InAs Nanowires

| Material System | Applied Force (μN) | Average Axial Strain ⟨εxx⟩ (%) | Electrical Conductivity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InAs/InGaAs Core-Shell Nanowire [14] | 1.19 | 0.187 | Increased | Uniaxial elastic strain leads to increased conductivity, explained by a strain-induced reduction in the band gap. |

| 4.49 | 0.837 | Increased | Inhomogeneity in strain distribution observed, which can increase charge carrier scattering and counter the conductivity gain. | |

| Bulk Nanocrystalline InAs [17] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Nanoindentation tests revealed a potential inverse Hall-Petch relation with a critical grain size of ~36 nm, a mechanical property that emerges at the nanoscale. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common FIB-SEM and In Situ TEM Challenges

This guide addresses frequent issues encountered during Focused Ion Beam (FIB) sample preparation for in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) experiments, providing solutions to ensure reliable nanomaterial characterization.

- Problem: Gallium (Ga) ion contamination and infiltration during FIB milling, leading to distorted precipitation behavior in alloys [18].

- Solution: Implement an optimized preparation and transfer protocol. Use low-energy (3 kV) ion milling for final polishing and combine with an external transfer method to significantly suppress Ga and Platinum (Pt) contamination [18].

- Problem: Abnormal precipitate coarsening or non-bulk-like material behavior in thin TEM samples [18].

- Solution: Optimize sample thickness. A thickness range of 150–200 nm is recommended to balance high imaging resolution with representative, bulk-like precipitation dynamics, avoiding the surface-driven effects seen in sub-100 nm samples [18].

- Problem: Sample bending, over-polishing, or uneven thinning when preparing TEM lamellae from thick layers (>20 μm) [19].

- Solution: Use a multi-window polishing approach. Prepare a large lamella and polish multiple smaller, separate windows (e.g., 10 μm width) to achieve uniform electron transparency across a large area without mechanical failure [19].

- Problem: Reduced spatial resolution and increased electron scattering in Liquid Cell TEM (LCTEM) due to the total cell thickness [20].

- Solution: For subsequent high-resolution chemical analysis, adopt a correlative workflow. Use cryogenic techniques to freeze the liquid-cell and prepare site-specific Atom Probe Tomography (APT) specimens via cryogenic Plasma-FIB (PFIB), enabling near-atomic scale compositional analysis of the preserved liquid-solid interface [20].

- Problem: Inaccurate strain and orientation mapping during in situ gas-solid reaction studies due to poor Bragg peak detection [21].

- Solution: Integrate Precession Electron Diffraction (PED) with a Direct Electron Detector (DED). Optimize gas pressure and use a "reaction pausing" strategy during 4D-STEM data acquisition to improve the quality and quantity of diffraction patterns for precise measurements [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is FIB the preferred method for preparing in situ TEM samples from bulk materials? FIB milling offers submicron precision and a non-contact process, which is essential for creating electron-transparent specimens (typically under 200 nm thick) while preserving the original microstructure. This is crucial for attaching and preparing samples on delicate MEMS-based heating or electrical chips for in situ experiments [18].

Q2: How can I minimize beam-induced damage or elemental redistribution during in situ heating experiments? Use a low electron beam current (e.g., 50 pA screen current) and avoid exposing your area of interest to the beam before data acquisition begins. Acquire data quickly from previously unexposed regions and scrutinize the initial frames of EDS maps to identify the onset of beam effects [22].

Q3: My sample is a 30 μm thick SiC layer. Can I still prepare a TEM lamella? Yes. Traditional "top-down" FIB may be unsuitable, but an innovative lift-out method can be used. This involves preparing a large lamella (e.g., 55 μm x 30 μm), using a nanomanipulator to lift out and rotate it, and then performing multi-window polishing on the grid to achieve a thin, uniform specimen suitable for STEM imaging [19].

Q4: What is the advantage of combining in situ TEM with Atom Probe Tomography (APT)? These techniques are highly complementary. In situ TEM provides dynamic, real-time imaging of nanoscale processes like growth or degradation. Cryo-APT subsequently offers three-dimensional, near-atomic resolution chemical mapping of the same specific site, bridging the gap between dynamic visualization and ultimate compositional resolution [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key In Situ Studies

Protocol 1: Optimized FIB Preparation for In Situ Heating of Alloys

This protocol mitigates Ga contamination for accurate observation of precipitation dynamics [18].

- Initial Milling: Perform bulk milling of the aluminum alloy sample using standard FIB procedures at a high angle (e.g., 52° tilt).

- Transfer: Use an external transfer method to mount the thinned sample onto the MEMS heating chip.

- Final Thinning & Cleaning: Conduct final thinning and surface cleaning using a low-energy ion beam at an accelerating voltage of 3 kV.

- Thickness Control: Ensure the final lamella thickness is in the 150–200 nm range.

- In Situ Heating: For observing T1 phase precipitation, heat the sample to 180 °C at a rate of 1 °C/s on the MEMS heater chip.

Protocol 2: Correlative In Situ Liquid Cell TEM and Cryo-APT

This workflow enables the study of dynamic liquid processes followed by ultra-high-resolution chemical analysis [20].

- In Situ LCTEM: Perform the electrochemical liquid cell TEM experiment using a commercial MEMS nanochip system to image the dynamic process of interest.

- Cryo-Fixation: Rapidly freeze the entire MEMS nanochip containing the liquid electrolyte to vitrify the liquid-solid interface.

- Cryo-Transfer: Transfer the frozen chip to a cryo-Plasma FIB (PFIB) using a cryogenic transfer suitcase to maintain cryogenic conditions.

- Cryo-APT Specimen Preparation: Inside the cryo-PFIB, use the Xe+ plasma ion beam to mill a site-specific, needle-shaped APT specimen from the area of interest on the frozen chip.

- Cryo-Atom Probe Analysis: Transfer the APT needle under cryogenic conditions to the atom probe instrument for 3D nanoscale compositional mapping.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents used in advanced in situ TEM experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS Heating E-Chip | In situ heating in TEM; supports sample and provides precise temperature control. | Silicon nitride membrane with embedded microheater; enables temperature uniformity >99.5% and fast quenching rates [22]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Stabilizing agent in colloidal synthesis of nanoparticles. | Used in synthesis of well-defined Pt-Rh solid solution and core-shell nanoparticles for in situ studies [22]. |

| Lithium Electrolyte (e.g., LiPF₆ in EC/DEC) | Electrolyte for in situ electrochemical liquid cell TEM studies of battery materials. | Flowed through MEMS nanochip to observe processes like dendrite growth or SEI formation in operating conditions [20]. |

| Precession Electron Diffraction (PED) Module | Enhanced 4D-STEM for robust strain and orientation mapping. | Provides quasi-kinematical diffraction; reduces sensitivity to sample thickness and mistilt, improving Bragg peak detection [21]. |

| Cryogenic Transfer Suitcase | Maintains cryogenic conditions during transfer between instruments. | Essential for moving frozen-hydrated samples (e.g., from liquid cell TEM or APT preparation) without thawing [20]. |

Workflow Visualization

Optimized FIB Preparation Workflow for In Situ TEM

Correlative In Situ TEM to APT Workflow

Proven FIB Methodologies for Specific Nanomaterial Classes and In Situ Experiments

The standard Focused Ion Beam (FIB) workflow for producing Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) lamellas is a meticulous, multi-stage process that enables the site-specific preparation of electron-transparent samples for high-resolution analysis [11]. The successful execution of this workflow is critical for subsequent atomic-resolution imaging and analytical studies in the TEM [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Step 1: Protective Layer Deposition

Before any milling occurs, a protective layer must be deposited over the region of interest (ROI) to prevent surface damage and to provide structural support during subsequent steps. This is typically achieved using a Gas Injection System (GIS) that releases an organo-platinum gas near the cold sample surface [24]. The gas condenses and, when exposed to the ion beam, forms a metallic/organic film that protects the underlying material [24]. For high-quality samples, especially when preparing plan-view specimens of 2D materials, a protective layer of 100-200 nm composed of Pt-C is recommended [25]. This layer serves dual purposes: it protects the surface from ion beam damage and reduces charging effects during imaging and milling [24].

Step 2: Rough Milling and Trench Creation

Rough milling involves using the FIB at relatively high currents (typically several nA) to excavate material on both sides of the protected ROI [23]. This process creates a "lamella" - a thin slice of material - that remains connected to the bulk sample at its base and sides. The milling patterns are initially set approximately 2 µm apart and are gradually brought closer together as material is removed [24]. For large-volume material removal, techniques such as "spin mill" can be employed, where material is removed at a nearly glancing angle while periodically rotating the stage to pre-defined milling sites [26]. This step requires careful planning to ensure the lamella is properly oriented and positioned.

Step 3: In-Situ Lift-Out Procedure

Once the lamella is freed from the bulk material on three sides, an in-situ micromanipulator is used to physically extract it [25]. The procedure involves:

- Approaching and Attaching: The micromanipulator needle is carefully positioned and attached to the lamella using Pt deposition from the GIS [25].

- Detaching: The remaining connections to the bulk sample are severed using the FIB at lower currents.

- Lifting: The manipulator gently lifts the lamella out of the trench [25].

This step requires precision and stability to avoid damaging the fragile lamella or introducing vibrations that could compromise the sample integrity.

Step 4: Lamella Transfer to TEM Grid

The extracted lamella is then transferred to a dedicated TEM grid. The manipulator positions the lamella over the grid and lowers it into place. Pt deposition is again used to weld the lamella to the grid posts, ensuring secure attachment during subsequent handling and imaging [25]. For plan-view samples of 2D materials, this step requires additional care to ensure the lamella is properly oriented to provide the desired top-down perspective [25].

Step 5: Final Thinning and Polishing

The final and most critical step involves thinning the lamella to electron transparency (typically below 200 nm, and for low-voltage STEM, often between 10-40 nm [23]). This is achieved through sequential milling at progressively lower ion beam currents and energies [23] [25]. The process may involve:

- Gradual current reduction from nA to pA range

- Decreasing accelerating voltages (often to 5-30 kV) to minimize amorphous damage layers [23]

- Using rocking polish techniques to reduce curtaining effects [26]

The target thickness depends on the intended TEM application, with thinner samples (10-20 nm) required for low-voltage, atomic-resolution imaging [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common FIB Preparation Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curtaining [26] | Vertical streaks or striations on milled surface | Variable milling rates through dissimilar materials | Use rocking polish techniques [26]; Employ multi-ion species milling (Xe, Ar, O) for different materials [26] |

| Charging Effects [24] | Image drift, abnormal milling patterns, sample movement | Non-conductive biological or insulating materials | Apply conductive coating (Pt sputtering) [24]; Use lower beam currents; Reduce scan rate |

| Beam-Induced Damage [23] | Amorphous layers, ion implantation, reduced crystallinity | High ion beam energy and currents | Use lower kV final polishing (5-30 kV) [23]; Implement progressive current reduction; Thick protective layers [25] |

| Incomplete Lift-Out | Lamella breaking during transfer | Insufficient structural support; Excessive milling | Ensure adequate Pt protection layer [25]; Leave temporary support during initial lift-out; Use gentler milling parameters |

| Non-Parallel Lamella | Wedge-shaped samples, varying thickness | Uneven milling; Incorrect stage alignment | Use "wedge pre-milling" strategy [23]; Verify stage eucentric height; Check beam alignment |

Advanced Troubleshooting Techniques

For persistent curtaining issues with complex material systems, consider using the Helios 5 Hydra DualBeam system which allows switching between different ion species (Xe, Ar, O) to optimize milling for different materials [26]. Oxygen ions are particularly effective for hard materials like silicon carbide (SiC) and diamond [26].

When preparing samples for atomic-resolution STEM at low voltages, the amorphous damage layer must be minimized. Research shows that using low-kV milling (5-30 kV) at earlier preparation stages, combined with thick protection layers and wedge pre-milling, can produce samples with less than 10 nm of damaged material, suitable for the most demanding applications [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the typical thickness range for a FIB-prepared TEM lamella?

The optimal thickness depends on the application:

- Standard TEM imaging: 100-200 nm [24]

- Atomic-resolution STEM at 300 kV: <52 nm [23]

- Low-voltage STEM (60-100 kV): 10-40 nm for high-quality imaging and EELS analysis [23]

- Cryo-electron tomography: 85-250 nm, depending on the biological question and downstream analysis [24]

Q2: How can I minimize amorphous damage in my FIB-prepared samples?

Several strategies can reduce beam damage:

- Use lower kV milling (5-30 kV) for final thinning steps [23]

- Apply thick protective layers (100-200 nm Pt-C) before milling [25]

- Implement progressive current reduction from nA to pA range during polishing [23]

- Consider "wedge pre-milling" techniques to preserve protective layers [23]

Q3: What are the key differences between cross-sectional and plan-view FIB preparation?

While the fundamental principles are similar, plan-view preparation presents unique challenges:

- Requires additional maneuvering steps and expertise in FIB operation [25]

- Needs careful consideration of tool geometry (stage, micromanipulator, beam positions) [25]

- Particularly challenging for ultra-thin 2D materials where the layer thickness may be only a few tens of nm [25]

- May require modified techniques such as creating special protective structures [25]

Q4: What is the purpose of the gas injection system (GIS) in FIB work?

The GIS serves multiple critical functions:

- Protective deposition: Organo-platinum gas forms a protective layer when exposed to the ion beam [24]

- Conductive coating: Reduces charging effects on non-conductive samples [24]

- Welding material: Used to attach the lamella to the micromanipulator and TEM grid [25]

- Enhanced milling: Certain gases can enable selective etching of specific materials [26]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Organo-Platinum GIS | Protective layer deposition; Lamella attachment | Essential for protecting leading edge during milling; prevents curtain artifacts [24] |

| Liquid Metal Ion Source (Ga+) | Standard ion source for milling and imaging | Source spot ~50-100 nm; Brightness ~10⁶ Am⁻²sr⁻¹V⁻¹; Standard for most applications [16] |

| Gas Field Ionization Source (He+) | Alternative ion source for reduced damage | Smaller source spot (~1 nm); Requires ultra-high vacuum and low temperature [16] |

| Plasma Ion Source (Xe+, Ar+) | Large-volume material removal | Higher current for faster milling; Ideal for bulk material removal [16] [26] |

| TEM Grids | Support structure for final lamella | Various materials (Cu, Au, Ni) and geometries; Must be compatible with TEM holder [25] |

| Cryo-Stage | Maintains cryogenic temperatures | Essential for cryo-FIB applications; Prevents ice contamination; Maintains sample at liquid nitrogen temperatures [24] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Focused Ion Beam (FIB) Artifacts and Mitigation

Table 1: Common FIB-Induced Artifacts and Solutions for Key Nanomaterials

| Artifact Type | Material Class Affected | Impact on Characterization | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Beam Damage (subsurface black spots, dislocations, amorphous layers) | Metallic Alloys (e.g., Fe, Fe-Cr) [4] | Obscures pre-existing defects (e.g., radiation damage); complicates microstructural analysis [4] | Flash Electropolishing (FEP) of FIB lamella [4] | [4] |

| Internal Crack/Pore Damage & Curtaining | Porous materials, materials with internal cracks (e.g., laser-treated Al/B4C composite) [27] | Damages fragile internal structures (crack tips, pore morphologies), hindering accurate TEM analysis [27] | In-situ FIB Redeposition Method: Sputter and redeposit material to fill features prior to final thinning [27] | [27] |

| Structural Artifacts (increased dislocation density) | Soft metallic phases (e.g., FCC Cu-rich phase) [28] | Introduces dislocations not present in the original material, misleading defect analysis [28] | Prefer conventional electropolishing where site-specificity is not required [28] | [28] |

| Chemical Artifacts (redeposition, preferential sputtering) | Various, but can be managed [28] | Potential for local chemistry changes at interfaces [28] | Optimize FIB milling parameters (tilt angles, accelerating voltages); use absorption-corrected quantification [28] | [28] |

Advanced Sample Preparation Protocols

Protocol: In-situ FIB Protection of Internal Cracks and Pores

This methodology protects vulnerable internal structures from ion beam damage and reduces curtaining effects during TEM sample preparation [27].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Preparation: Begin with standard FIB procedures, including the deposition of a protective platinum or carbon layer via the Gas Injection System (GIS) on the sample's top surface [27].

- Rough Milling and Lift-out: Perform initial trench milling and rough thinning to create an electron-transparent lamella, followed by sample lift-out and mounting to a TEM grid [27].

- Critical - In-situ Redeposition:

- Use the FIB to sputter material from the immediate vicinity of the internal crack or pore.

- The sputtered material is intentionally redeposited directly into the void, effectively "filling" it. This filling material acts as a scaffold during subsequent milling steps [27].

- Final Thinning and Polishing: Continue with low-energy (e.g., 5-10 kV) ion polishing to achieve the desired final thickness for TEM analysis. The filled structure protects the original edges of the crack/pore from erosion and mitigates curtaining [27].

- Application Note: This method has been successfully demonstrated on modular pure iron and porous laser-treated Al/B4C composites, preserving the integrity of internal features [27].

Protocol: Flash Electropolishing (FEP) for Metallic Alloys

Flash Electropolishing is a post-FIB treatment proven to remove surface and subsurface artifacts from metallic TEM lamellae, making them comparable to jet-polished samples [4].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Sample: A TEM lamella is first prepared using standard FIB techniques [4].

- Setup: The FIB lamella is carefully mounted in a custom electropolishing setup and submerged in an appropriate electrolyte [4].

- Critical - Flash Polishing: A controlled voltage pulse is applied for a very short duration. The precise parameters (voltage, time, electrolyte composition) are material-dependent and must be optimized. For Fe-Cr alloys like HT-9, this process has been successfully demonstrated [4].

- Outcome: This rapid electropolishing step removes the amorphous surface layer, subsurface black spot damage, and surface dislocations introduced by the ion beam, revealing the true microstructure of the material [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for FIB-based TEM Sample Preparation

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Metal Ion Source (LMIS) | Source of ions (typically Ga+) for milling and imaging [16]. | The Ga+ source is most common due to its low melting point and high brightness [16]. |

| Gas Injection System (GIS) | Allows for site-specific deposition of protective layers (e.g., Pt, C) and materials for redeposition [27]. | Critical for protecting surfaces and enabling the in-situ redeposition method for cracks/pores [27]. |

| Flash Electropolishing Setup | Specialized apparatus for applying controlled voltage pulses to remove FIB artifacts from metallic samples [4]. | Essential for preparing artifact-free samples for sensitive microstructural analysis (e.g., irradiated metals) [4]. |

| High-Permeability Magnetic Shielding | Materials like Mu-metal or silicon iron used to shield TEM columns from ambient DC magnetic fields [29]. | Required to achieve the tight magnetic field specifications for high-resolution TEM imaging [29]. |

| Eddy Current Shielding | Typically aluminum panels, used to attenuate AC magnetic fields in the laboratory [29]. | Often installed in room walls during renovation to protect sensitive instruments [29]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I am analyzing neutron-irradiated Fe-Cr alloys and need to characterize inherent radiation damage (e.g., black spots). My FIB-prepared samples show similar features. How can I be sure what I'm seeing is real?

A1: This is a critical consideration. FIB preparation can introduce subsurface artifacts, including black spots (clusters of point defects) and dislocations, that can obscure or be mistaken for pre-existing radiation damage [4]. To verify your results:

- Primary Solution: Employ Flash Electropolishing (FEP) on your FIB-prepared lamella. This post-processing step has been proven to effectively remove the FIB-induced artifacts, leaving behind only the intrinsic microstructure of the irradiated material, allowing for unambiguous analysis [4].

- Comparison: If possible, compare your FIB+FEP results with samples prepared by conventional electropolishing, which is artifact-free but less site-specific [4] [28].

Q2: The TEM sample of my porous laser-treated Al/B4C composite was ruined by curtaining effects and the pores were damaged during FIB milling. How can I prevent this?

A2: The solution is to use an in-situ FIB redeposition method [27].

- Principle: Prior to the final thinning of the TEM lamella, use the FIB to sputter material from the area immediately surrounding the pores and redeposit it directly into the pore spaces.

- Benefit: This "fills" the pores with a supportive scaffold, which prevents the ion beam from penetrating and damaging the fragile pore morphologies during subsequent milling steps. This filled structure also mitigates the curtaining effect that occurs when the beam mills over features with vastly different sputtering rates [27].

Q3: For my Cu-Ti alloy, I need precise chemical profiling across phase interfaces. Can I trust EDS data from a FIB-prepared sample, or will Ga+ implantation/redeposition alter the chemistry?

A3: With proper precautions, yes. A systematic study on a Cu-4 at% Ti alloy demonstrated that quantitative EDS profiles across heterophase interfaces were equivalent in both FIB-prepared and conventionally electropolished samples [28]. To achieve reliable results:

- Optimize FIB milling parameters (tilt angles, accelerating voltages).

- Use the Cliff-Lorimer ratio method with an absorption correction for quantification.

- Be aware that while chemical artifacts can be minimized, structural artifacts (e.g., a high dislocation density in soft phases) are still introduced by FIB and must be considered for structural analysis [28].

Q4: My high-resolution TEM is experiencing unexplained resolution drift. The site was previously acceptable, and the problem is intermittent. What could be the cause?

A4: Intermittent problems often point to varying external magnetic fields.

- Source: The most likely cause is a low-frequency AC magnetic field interference from new equipment installed in or near your lab (e.g., elevators, subway lines, HVAC systems, or other large instruments) [29].

- Solution: A professional magnetic field survey is recommended. Mitigation may require installing an active magnetic field cancellation system. For TEMs with long columns, a Dual Cancellation System is often necessary to compensate for field gradients along the entire electron beam path, ensuring both the source (top) and detector (bottom) are within specification [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: MEMS Chip Mounting for In Situ TEM

Problem 1: Sample Fragmentation or Chipping During FIB Lift-Out

- Symptoms: Lamella cracks during milling or probe detachment; sample disintegrates upon transfer.

- Potential Causes: Excessive mechanical load from traditional polishing; high ion beam currents causing stress; inherent material brittleness.

- Solutions:

- Implement a wedge polishing technique for primary thinning to minimize mechanical load before FIB final thinning [30].

- Use lower ion beam currents for the final polishing stages to reduce milling-induced stress and damage [30].

- For ultra-fine or fragile materials, consider the "direct lift-out" technique, which is specifically designed for handling such challenging specimens [31].

Problem 2: Poor Electrical Contact on MEMS Heater Chips

- Symptoms: Inconsistent thermal response; inability to reach target temperatures during in situ heating experiments.

- Potential Causes: Improper seating of the MEMS chip on the holder; oxidation or contamination of contact pads; insufficient force from the holder's electrical contacts.

- Solutions:

- Utilize a remotely controlled, piezo-driven micro-manipulator system inside a glovebox for precise, contamination-free loading of the MEMS chip onto the holder [32].

- Ensure the MEMS chip and holder contacts are clean. Perform all handling in an inert atmosphere if the sample is air-sensitive [32].

- Verify the MEMS chip is correctly seated and that the holder mechanism fully closes to ensure a tight electrical connection [32].

Problem 3: Contamination and Hydrocarbon Deposition

- Symptoms: Amorphous layer on sample surface; blurred imaging; unclear analytical data.

- Potential Causes: Sample exposure to atmosphere; inadequate cleaning prior to insertion into the TEM vacuum.

- Solutions:

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Piezoelectric Holder Mounting and Signal Issues

Problem 1: Weak or No Signal Output

- Symptoms: Low voltage output; inconsistent readings; no signal detected.

- Potential Causes: Incorrect cable connection or damaged cables; improper grounding; insufficient pre-loading force on the transducer.

- Solutions:

- Use short, shielded coaxial cables and check all connections for integrity. The cable length should not be altered after installation, as this changes the system capacitance [33].

- Ensure the system has a proper ground to protect the device and shield it from electromagnetic interference [33].

- For force transducers, apply a pre-compressive force via mounting to ensure firm contact and rigidity, which improves signal transfer and linearity [33].

Problem 2: Signal Noise and Electromagnetic Interference (EMI)

- Symptoms: Unstable baseline; high-frequency fluctuations in data; erratic signal.

- Potential Causes: Long, unshielded cable runs; ground loops; proximity to noise sources like AC motors.

- Solutions:

- Place the charge amplifier or signal conditioning peripherals as close as possible to the transducer to minimize the distance of charge transmission [33].

- Use proper shielding around the transducer and cables to guard against EMI and the reverse piezoelectric effect [33].

- Ensure the transducer housing is sealed against dust and dirt, which can introduce noise [33].

Problem 3: Mounting-Induced Frequency Response Limitations

- Symptoms: Attenuated high-frequency data; lower-than-expected resonant frequency.

- Potential Causes: Use of adhesives or soft mounting materials that act as a mechanical filter; magnetic base not firmly attached.

- Solutions:

- For the highest frequency response, stud mounting to a smooth, flat, machined surface is recommended [34].

- If using a magnetic base, ensure it is attached to a smooth, flat surface and apply a thin layer of silicone grease to improve high-frequency transmissibility. Avoid soft mounting pads [34].

- Be aware that any mounting method less rigid than a stud or screw will reduce the upper-frequency response of the system [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the single most important factor for achieving high-quality FIB-lamellae for in situ TEM? The quality of the specimen is imperative. The preparation technique must preserve the original material structure by avoiding mechanical load that can cause microstructural changes and minimizing ion beam damage that can lead to amorphization or implantation [30]. The synergy of wedge polishing and an advanced FIB workflow combines the advantages of both methods to minimize these invasive effects [30].

FAQ 2: My experiment requires a plan-view sample. Why is FIB preparation for this geometry particularly challenging? Plan-view FIB preparation is difficult because it often requires extended ion milling near the sensitive surface region of interest, which increases the risk of ion beam damage, re-deposition, and artifact creation [30]. Furthermore, it can be hard to detach the lamella from the underlying bulk material completely without visual confirmation.

FAQ 3: How does the mounting method affect the usable frequency range of my piezoelectric sensor? The mounting method directly impacts the system's mounted resonant frequency, which dictates the upper limit of the usable frequency range [34]. Direct stud mounting yields the highest frequency response. Any addition, like an adhesive or magnetic base, adds mass and compliance, lowering the resonant frequency and limiting high-frequency measurement capability [34].

FAQ 4: What is the purpose of a charge amplifier for a piezoelectric transducer? A charge amplifier converts the high-impedance charge output from the piezoelectric sensor into a low-impedance voltage signal. Its design fixes the calibration factor, allows for an adjustable dynamic frequency range, and, crucially, eliminates the negative effects of stray capacitances from the sensor and connecting cables, leading to stable and accurate measurements [33].

FAQ 5: How should I safely remove an accelerometer that has been mounted with adhesive? Apply a debonding agent (like acetone for Loctite 454 adhesive) and allow it a few minutes to penetrate and react with the adhesive. After waiting, use a gentle shear or twisting motion by hand with an appropriate wrench or removal tool to detach the sensor. Never use excessive force [34].

The table below summarizes the approximate frequency response ranges for different accelerometer mounting techniques, which is critical for selecting a method suitable for your experiment's dynamic range [34].

Table 1: Frequency Ranges of Common Mounting Techniques

| Mounting Technique | Approximate Usable Frequency Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Stud Mounting | Highest (up to 30kHz+) | Yields broadest usable range; requires tapped hole; matches factory calibration [34]. |

| Screw Mounting | Very High | Good alternative to stud mounting; ensure screw does not bottom out [34]. |

| Adhesive Mounting (Epoxy) | Medium to High | Stiff epoxies maintain better high-frequency response; can be permanent [34]. |

| Magnetic Base | Low to Medium (often 1-5kHz) | Convenient for temporary mounting; high pull strength magnets perform better [34]. |

| Easy-Mount Clip | Low (1-3.5kHz) | Practical for multi-channel measurements; frequency response is reduced due to softer connection [34]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Advanced Plan-View TEM Sample Preparation via Wedge Polishing and FIB

This protocol is designed for preparing plan-view specimens from fragile materials, such as Ge Stranski–Krastanov islands on Si, for in situ TEM heating experiments [30].

- Site Selection & Initial Preparation: Use a precision diamond saw to cut a small sample (e.g., 2.5 × 1.0 × 0.5 mm) from the bulk material. Polish both sides of this sample to create a flat surface and minimize cutting damage [31].

- Wedge Polishing (Mechanical Pre-thinning): Mount the sample on a wedge polisher (e.g., MultiPrep instrument). Use progressively finer diamond lapping films to mechanically thin the sample from the backside at a shallow angle until it is translucent under an optical microscope (for Si, this is below ~10 µm). This step minimizes the volume of material requiring FIB milling [30].

- FIB-Assisted Lift-Out (in FIB-SEM)

- Site Selection & Protection: Use the SEM to locate the area of interest. Deposit a protective layer (e.g., Platinum) over the site using ion-beam-induced deposition to shield it during milling [30].

- Coarse Milling: Use the ion beam at a relatively high current to mill trenches around the protected site, creating a thin lamella (typically 3–4 µm thick) that remains attached to the bulk material for support [30] [31].

- Lift-Out & Mounting: Weld a nanomanipulator probe to the lamella, cut it free, and lift it out. Weld the lamella onto a MEMS-based TEM sample carrier (e.g., a heating chip) and detach the probe [30].

- Final Thinning & Polishing: Thin the mounted lamella from both sides using the ion beam at progressively lower currents until it is electron-transparent (typically <100 nm for HR-STEM). Perform a final low-energy (low-kV) polish to remove the damaged surface layer and achieve the desired final thickness (e.g., ~30 nm) [30].

Protocol 2: Mounting a Piezoelectric Force Transducer for Dynamic Measurement

This protocol ensures optimal signal quality and frequency response when installing a piezoelectric force transducer [33].

- Pre-installation Check: Perform a pre-installation test to verify the sensor's basic functionality. Check the manufacturer's datasheet for key specifications like resonant frequency and Curie temperature.

- Mounting Surface Preparation: Prepare a smooth, flat, and clean mounting surface. For the best high-frequency transmissibility, the surface should be machined smooth. A thin layer of silicone grease can be applied to improve coupling [34].

- Transducer Orientation and Mounting: Mount the transducer such that its geometric shape aligns the internal piezoelectric material along the loading axis. The transducer's output electrodes should be perpendicular to the direction of the applied stress. For dynamic measurements, use a mounting system that provides a firm pre-compressive force (pre-load) to dampen vibrations and improve linearity [33].

- Cabling and Shielding: Connect the transducer using a short, shielded coaxial cable. Do not alter the cable length after installation, as this changes the system's capacitance. Keep exposed contacts clean and free of debris [33].

- Signal Conditioning Integration: Place the charge amplifier as close as possible to the transducer to minimize noise and signal loss. Connect the output of the charge amplifier to your data acquisition system [33].

- Grounding and Housing: Ensure the entire system, including the transducer and amplifier, is properly grounded to prevent ground loops and protect against EMI. House the transducer in its recommended environment (often a vacuum-sealed unit) to exclude air loading and contaminants [33].

- Post-installation Testing and Calibration: Perform a post-installation loop test. Calibrate the entire force measurement system by comparing its reading to a known standard to identify and correct for systematic errors [33].

Workflow Visualization

Plan-View TEM Sample Prep Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Sample Mounting and Preparation

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| MEMS-based Heating Chips | Sample carriers for in situ TEM heating experiments; contain integrated heater and electrodes [30]. |

| Protective Pt/C Layer (FIB) | Deposited via ion/electron beam to protect the region of interest from ion damage during FIB milling [30]. |

| Diamond Lapping Films | Used for wedge polishing to achieve precise mechanical pre-thinning of samples with minimal damage [30]. |

| Debonding Agent (e.g., Acetone) | Solvent used to dissolve certain adhesives (e.g., Loctite 454) for safe accelerometer removal without damage [34]. |

| Silicone Grease | A thin layer applied at mounting interfaces to fill microscopic voids, improving high-frequency transmissibility in vibration measurements [34]. |

| Charge Amplifier | Critical peripheral that converts a piezoelectric sensor's charge output to a low-impedance voltage signal and conditions it [33]. |

| Shielded Coaxial Cable | Used for connecting piezoelectric sensors to minimize electromagnetic interference and signal loss [33]. |

| Insulated Adhesive Bases | Provide an alternative mounting method for accelerometers and can also offer electrical isolation to prevent ground loops [34]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and reagents essential for preparing TEM samples for specific in situ stimuli.

| Item | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based Sample Carrier | Holds electron-transparent lamella for in situ experiments; enables precise application of heat and electrical bias [30] [3]. | Heating, Biasing |

| Protective Pt/C Layer | Ion/electron-beam deposited layer to shield the region of interest from damage during initial FIB milling steps [9]. | General FIB Preparation |

| Diamond Lapping Films | Used for primary mechanical thinning (wedge polishing) to broadly reduce sample thickness with minimal subsurface damage [30]. | Plan-view Specimen Preparation |

| Cryo-EM Grids (e.g., 200-mesh) | Support for vitrified biological specimens; often coated with an extra carbon layer for stability [35]. | Liquid Cell (Cryo-ET) |

| Autogrid Box | Specialized holder for storing and transferring cryo-lamellae prepared via the "waffle method" for cryo-ET [35]. | Liquid Cell (Cryo-ET) |

| High-Pressure Freezer (HPF) Planchettes | Used to hold samples for high-pressure freezing, which vitrifies thick specimens (up to 60 μm) without ice crystal damage [35]. | Liquid Cell (Cryo-ET) |

| Flash Electropolishing Setup | Used for a final, gentle thinning step to remove FIB-induced surface and subsurface artifacts from metallic TEM lamellae [4]. | Metallic Sample Post-Processing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Plan-View Specimen Preparation for In Situ Heating

This protocol combines wedge polishing and FIB to create pristine plan-view samples, ideal for observing surface-related phenomena like strain relaxation during heating experiments [30].

Workflow Diagram: Plan-View TEM Sample Preparation

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Mounting: Mount the bulk sample (e.g., a Si substrate with Ge nanostructures) onto a dedicated Pyrex holder using an appropriate adhesive [30].

- Mechanical Wedge Polishing: Use a system like the MultiPrep with diamond lapping films to thin the sample from the backside at a shallow angle. This creates a large, gradually thinning area, minimizing mechanical damage compared to conventional grinding [30].

- Thickness Monitoring: For Si-based materials, monitor the polishing progress by observing the sample's translucency under visible light. A thickness of ~10 µm indicates suitability for the next step [30].

- FIB Transfer: Within a FIB-SEM instrument, deposit a protective layer over the region of interest. Then, use the ion beam to cut and lift out a thin lamella from the polished wedge and transfer it onto a MEMS-based heating holder. This step requires high spatial accuracy [30] [9].

- Final Thinning and Polishing: Perform final thinning of the lamella using low-energy FIB milling (e.g., at 30 kV or lower) to achieve electron transparency (typically below 200 nm) and remove any surface amorphization [30] [9].

- In Situ Experiment: Insert the MEMS carrier into a TEM heating holder. The sample is now ready for real-time observation of structural evolution, such as thermal-induced strain relaxation in Ge islands at the atomic scale [30].

Flash Electropolishing for FIB-Prepared Metallic Samples

FIB milling can introduce artifacts in metallic samples, such as surface dislocations, moiré fringes, and subsurface black spots (clusters of point defects). Flash electropolishing (FEP) effectively removes these artifacts to reveal the true material microstructure [4].

Application Context: This post-processing method is critical for characterizing radiation-induced defects in metals and alloys, where FIB artifacts can obscure or interact with pre-existing defects, leading to incorrect microstructural analysis [4].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Standard FIB Preparation: First, produce a TEM lamella from the metallic sample (e.g., Fe-Cr alloy) using the standard FIB lift-out technique and mount it on a TEM grid [4] [9].

- Setup for Electropolishing: Prepare an electrochemical cell with a suitable acidic electrolyte (e.g., a mixture of perchloric acid and alcohol for some steels). The FIB-prepared lamella, still attached to its TEM grid, serves as the anode.

- Flash Electropolishing (FEP): Apply a controlled voltage for a very short duration (typically a few seconds). The key is to optimize the voltage and time to remove a thin surface layer (a few hundred nanometers) without perforating or compromising the lamella [4].

- Validation: Examine the FEP-treated lamella via TEM or diffraction-contrast imaging STEM (DCI-STEM). A successful polish will show the removal of the amorphous surface layer and the absence of FIB-induced moiré fringes and surface dislocations, resulting in a sample comparable to one prepared by traditional jet polishing [4].

Cryo-Lamella Preparation for In Situ Liquid Cell TEM (Cryo-ET)

This protocol outlines the "waffle method" for preparing thick biological samples (e.g., cells, tissues) for in situ structural biology studies using cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) [35].

Workflow Diagram: Cryo-Lamella Preparation via Waffle Method

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Vitrification: Concentrate the biological sample (e.g., yeast, bacteria, mammalian cells) and load it into a specialized "waffle" sandwich between two HPF planchettes. Vitrify the sample using a high-pressure freezer (HPF). This process preserves the sample in a native, hydrated state without destructive ice crystals [35].

- Transfer and Loading: Under liquid nitrogen, the vitrified "waffle" is assembled onto a SEM pin stub and transferred into a cryo-FIB/SEM instrument, such as an Aquilos 2, using a cryo-transfer shuttle. The sample is maintained at vitreous temperature (around -170 °C) throughout [35].

- Region of Interest (ROI) Localization: Use an integrated fluorescence light microscope (iFLM) to identify fluorescently-tagged objects or structures within the vitrified sample. This correlative microscopy step ensures the lamella is milled at the correct location [36] [35].

- Semi-Automated Cryo-FIB Milling: Use software (e.g., MAPS and AutoTEM Cryo) to define the milling sites. The system then automatically performs cryo-FIB milling from the top and front sides to produce a thin, electron-transparent cryo-lamella with a target thickness of 100-200 nm and dimensions of approximately 12 μm × 15-20 μm [35].

- Tomography: Transfer the prepared cryo-lamella to a cryo-TEM (e.g., Krios G4 or Glacios 2) for cryo-ET data acquisition. A series of images is acquired by tilting the sample, which are then reconstructed into a 3D tomogram, revealing in situ structures at molecular resolution [36] [35].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a plan-view geometry necessary for some in situ heating experiments, and what are the preparation challenges? A1: Plan-view geometry, where the electron beam is perpendicular to the sample surface, is vital for gathering information on surface morphology, grain size and orientation, and particle distributions [30] [3]. The primary challenge is preparing a large, electron-transparent area that includes the free surface without introducing damage via mechanical load or ion beam illumination, which can alter the pristine material properties [30].

Q2: How can I verify that the artifacts I see in my metallic TEM sample are from FIB preparation and not intrinsic to the material? A2: FIB often introduces characteristic artifacts such as a surface amorphous layer, subsurface "black spot" damage (clusters of point defects), surface dislocations, and moiré fringes [4]. If these features diminish or disappear after a gentle post-processing technique like flash electropolishing, they are likely FIB-induced artifacts rather than intrinsic material defects [4].

Q3: My samples are thick tissues/organoids. Can I still prepare them for high-resolution in situ liquid cell TEM? A3: Yes. While plunge-freezing is limited to thin samples (~5-10 μm), the "waffle method" using high-pressure freezing (HPF) allows for vitrification of specimens up to 60 μm thick [35]. These vitrified samples can then be thinned using cryo-FIB milling to produce cryo-lamellae suitable for cryo-ET, enabling the study of complex biological systems in near-native states [36] [35].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample charging or hydrocarbon contamination during TEM. | Contamination from sample preparation or transfer; inadequate electrical grounding. | Use plasma cleaning on the sample directly before inserting it into the TEM to remove hydrocarbons [9]. Ensure the sample is securely mounted to a conductive holder. |

| Specimen is too thick for HR-STEM imaging. | Final FIB polishing was insufficient. | For high-resolution STEM, the specimen thickness often needs to be below 50 nm [30]. Perform an additional, careful low-kV (e.g., 2-5 kV) polish in the FIB to remove material and achieve electron transparency without introducing new damage [9]. |

| Unusual moiré fringes or dislocations in metallic FIB lamella. | Subsurface damage and strain from the Ga+ ion beam during FIB preparation [4]. | Apply a post-FIB flash electropolishing (FEP) step. With the proper parameters, FEP can effectively remove these surface and subsurface artifacts, producing a sample comparable to traditional jet polishing [4]. |

| Low throughput in cryo-lamella preparation for cellular cryo-ET. | Manual milling is time-consuming; plunge-frozen grids have poorly distributed cells [35]. | Adopt the "waffle method" with HPF and semi-automated milling software (e.g., AutoTEM Cryo). This increases throughput by creating larger, specimen-dense lamellae and allows for unattended overnight milling [35]. |

Solving Common FIB Pitfalls: A Guide to Avoiding Contamination and Experimental Failure

Minimizing Gallium and Platinum Contamination in Sensitive Materials like Aluminum Alloys

Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscopy (FIB-SEM) has become an indispensable tool for preparing site-specific transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples, particularly for nanomaterials characterization research. However, for sensitive materials like aluminum alloys, the conventional use of gallium (Ga) ions and platinum (Pt) protective layers introduces significant artifacts that can compromise experimental results. Ga⁺ ions have high solubility in aluminum and tend to segregate at grain boundaries and interfaces, causing liquid metal embrittlement and distorting intrinsic material properties [37] [18]. Similarly, Pt deposition can introduce damage in the near-surface region if not properly optimized [38]. This technical guide provides evidence-based protocols to minimize these contamination sources, ensuring reliable microstructural and compositional analysis for your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is gallium contamination particularly problematic for aluminum alloy studies?

Ga contamination severely impacts aluminum alloys due to three primary mechanisms: First, Ga exhibits high solubility in Al and rapidly penetrates grain boundaries, inducing liquid metal embrittlement (LME) that dramatically reduces ductility [37]. Second, during in situ heating experiments, implanted Ga⁺ ions redistribute upon heating, forming intragranular nanoclusters (∼10 nm) and grain boundary enrichment, which significantly distorts the intrinsic precipitation behavior of phases like T1 in Al-Cu-Li alloys [18]. Third, Ga decoration at interfaces and grain boundaries produces misleading results in segregation studies and microstructural analysis [37] [39].

Q2: Can "damage-free" TEM specimen preparation truly be achieved?

The concept of "damage-free" preparation requires careful definition. A high-quality TEM specimen requires less than 5 nm damage thickness, while "damage-free" conditions demand sub-1 nm damage layers [39]. Achieving this requires a multi-faceted approach: using proper ion species (Xe⁺ or Ar⁺ instead of Ga⁺), reducing FIB energy below 1-1.5 keV for final polishing, and understanding that any TEM specimen below 50 nm thick prepared at 30 keV will be fully damaged regardless of ion species [39]. True damage-free preparation is thus a combination of optimized parameters rather than a single solution.

Q3: What are the key advantages of plasma FIB (Xe⁺) over conventional Ga⁺ FIB?

Xe⁺ Plasma FIB (P-FIB) offers several distinct advantages: (1) Elimination of Ga-related artifacts, particularly beneficial for materials like Al where Ga alloys with the base metal [37] [40]; (2) Higher sputtering yields and maximum usable beam currents (approximately 40× higher), enabling efficient milling of larger structures [40]; (3) Xe is a noble gas, unlikely to form chemical bonds with Al, thus avoiding affinity or alloying at interfaces and grain boundaries [39]; (4) Production of thinner amorphous damage layers compared to Ga⁺ FIB [37].

Q4: How does sample thickness affect precipitation studies during in situ TEM heating?

Sample thickness critically influences precipitation kinetics in aluminum alloys. Studies on Al-Cu-Li alloys show that sub-100 nm samples exhibit surface-driven abnormal coarsening of T1 precipitates, while samples exceeding 250 nm suffer from reduced imaging resolution due to limited electron transparency. A thickness range of 150-200 nm optimally balances resolution fidelity with representative precipitation dynamics that more closely match bulk material behavior [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Gallium Contamination Mitigation

Table: Gallium Contamination Mitigation Strategies

| Issue | Symptoms | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grain Boundary Decoration | White contrast at GBs in HAADF-STEM, reduced mechanical strength | Switch to Xe⁺ Plasma FIB; Use low-energy (3 kV) final cleaning step [18] | Implement cryogenic FIB preparation to slow Ga diffusion [18] |

| Altered Precipitation | Abnormal precipitate nucleation/growth during in situ heating | Combine external transfer with low-energy ion milling at 3 kV [18] | Maintain sample thickness 150-200 nm to preserve bulk-like behavior [18] |

| Liquid Metal Embrittlement | Loss of ductility, intergranular fracture | Use Xe⁺ FIB for entire preparation process [37] | Avoid Ga⁺ FIB entirely for Al alloys; Use Ar⁺ polishing [37] |

| Implantation Artifacts | Amorphous layer, dislocation loops, Ga implantation >20 at.% [38] | Use sub-1 keV energy for final polishing [39] | Employ combined E-beam/I-beam Pt deposition strategy [38] |

Platinum Deposition Damage Control

Table: Platinum Deposition Optimization Protocols

| Deposition Method | Damage Characteristics | Recommended Usage | Parameters |