Mastering Basis Set Error: A Practical Guide for Accurate Computational Chemistry and Drug Design

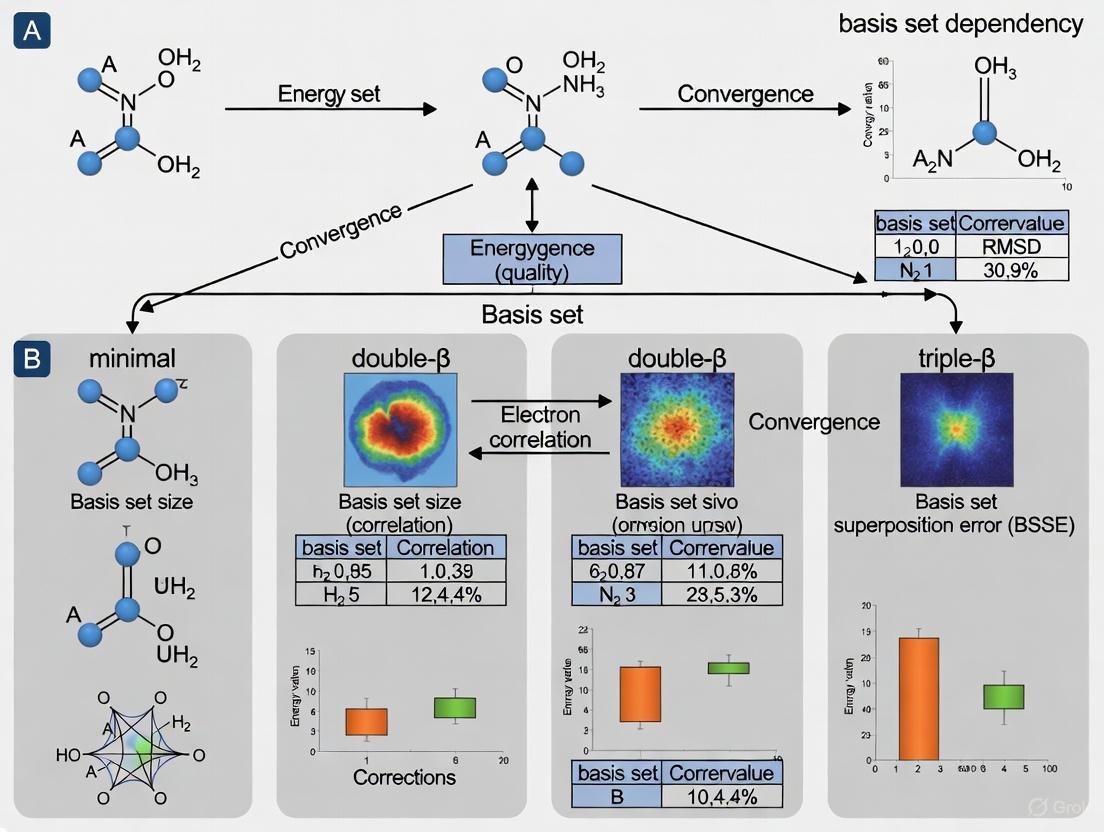

This article provides a comprehensive guide to understanding, managing, and minimizing basis set dependency errors in computational chemistry, with a focus on applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Mastering Basis Set Error: A Practical Guide for Accurate Computational Chemistry and Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to understanding, managing, and minimizing basis set dependency errors in computational chemistry, with a focus on applications in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the fundamental sources of basis set incompleteness error (BSIE), presents systematic methodological approaches for basis set selection and optimization, offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like linear dependence, and establishes validation protocols using benchmark data and multiresolution analysis. The content is tailored to help researchers and scientists make informed decisions to enhance the reliability of their computational results for critical applications like molecular property prediction and ligand design.

Understanding Basis Set Errors: The Hidden Challenge in Computational Accuracy

Basis Set Incompleteness Error (BSIE) and Its Impact on Calculated Properties

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between BSIE and BSSE?

The Basis Set Incompleteness Error (BSIE) and the Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) are two related but distinct shortcomings of calculations using finite basis sets.

- BSIE is the inherent error that arises because the atomic orbital (AO) basis set is a finite expansion, not complete. It leads to an insufficient description of physical effects like Pauli repulsion, electrostatics, and polarization, which can systematically lengthen chemical bonds and misrepresent molecular properties [1].

- BSSE occurs specifically when analyzing interacting molecules or different parts of a molecule. As fragments approach, their basis functions overlap. Each monomer can variationally "borrow" basis functions from nearby fragments, artificially lowering the total energy of the complex. This creates an imbalance because the complex is calculated with a larger, effectively better basis set than the isolated monomers [2] [1].

2. Why should I be concerned about BSIE/BSSE in drug development research?

For researchers in drug development, noncovalent interactions—such as those between a potential drug molecule and its protein target—are critical. Using a small basis set of double-zeta quality (e.g., 6-31G*):

- Overestimates binding energies due to BSSE, potentially by over 40% [1].

- Underestimates interatomic distances, leading to inaccurate geometries of host-guest complexes or protein-ligand binding pockets [1]. These errors can mislead the interpretation of structure-activity relationships and compromise the reliability of virtual screening efforts.

3. How can I resolve these errors without making calculations prohibitively expensive?

Correcting these errors doesn't always require moving to a massive, computationally expensive basis set. Modern correction schemes provide a robust solution:

- For BSSE, apply the Counterpoise (CP) correction to interaction energies [2] [1].

- For the general limitations of small basis sets, including BSIE and the lack of London dispersion interactions, use composite methods like PBEh-3c. These methods integrate a moderate-sized basis set with built-in empirical corrections for dispersion and BSIE, offering a favorable balance of accuracy and cost for large systems [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Noncovalent Interaction Energies

Problem Description Calculated binding energies for molecular complexes (e.g., supramolecular assemblies, protein-ligand systems) are suspected to be too high, and equilibrium intermolecular distances are too short.

Diagnosis This is a classic symptom of significant Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE), which is particularly pronounced with small basis sets of double-zeta quality (e.g., 6-31G*, def2-SVP). The error arises because the basis set of the complex is more complete than that of the isolated monomers [2] [1].

Resolution: Apply the Counterpoise (CP) Correction

The Boys-Bernardi Counterpoise (CP) scheme is the standard method to correct for intermolecular BSSE [2] [1].

Experimental Protocol

- Calculate the energy of the complex (AB) in its full basis set,

ab, with geometry frozen from the optimized complex: E(AB)_ab. - Calculate the energy of monomer A in the same geometry as in the complex, but using only its own basis set,

a: E(A)_a. - Calculate the energy of monomer A again, but place it in the full basis set of the complex,

ab(using "ghost orbitals" for atom centers of B): E(A)_ab. - Repeat steps 2 and 3 for monomer B, calculating E(B)b and E(B)ab.

- Compute the CP-corrected interaction energy using the following formula: ΔECP = [ E(AB)ab - E(A)ab - E(B)ab ]

The CP correction, ΔE_CP, is given by the difference between the BSSE-uncorrected energy and the result of the formula above. It represents the artificial stabilization energy that must be subtracted [1].

Workflow Visualization

Issue: Systematic Structural Errors with Small Basis Sets

Problem Description Geometries optimized with small double-zeta basis sets show systematically elongated bonds and poor agreement with experimental crystal structures or high-level benchmark calculations.

Diagnosis This indicates a significant Basis Set Incompleteness Error (BSIE), where the basis set is too limited to describe the electron density accurately, particularly in bonding regions and for noncovalent interactions [1].

Resolution: Utilize Dispersion-Corrected Composite Methods

Instead of using a plain functional with a small basis set, employ a specially designed composite method like PBEh-3c. These methods integrate a Hamiltonian (like PBE hybrid), a moderately sized basis set (e.g., def2-mSVP), and empirical corrections to account for London dispersion interactions and BSIE in a single, consistent package [1].

Experimental Protocol

- Method Selection: In your computational chemistry software, select the composite method (e.g.,

PBEh-3c). This choice automatically includes:- A specific density functional (PBEh with 42% Fock exchange).

- A defined AO basis set (def2-mSVP).

- A gCP correction for BSIE/BSSE.

- A D3 dispersion correction with damping.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a standard geometry optimization and frequency calculation using this method.

- Energy Evaluation: For accurate single-point energies, the method is used self-consistently. No separate counterpoise correction is typically needed for the energy.

Logical Relationships in Composite Methods

Quantitative Data on Basis Set Errors

Table 1: Magnitude of BSSE in Different Computational Setups

This table summarizes how the Basis Set Superposition Error is influenced by the choice of basis set and the amount of Fock exchange in the functional, based on data from the S66 benchmark database [1].

| Basis Set Type | Example Basis Sets | Amount of Fock Exchange | Typical BSSE Magnitude (% of Binding Energy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | MINIX | 0% to 100% | Relatively Small |

| Double-Zeta (DZ) | 6-31G*, def2-SVP | 0% (PBE) | > 40% (Most Pronounced) |

| 20% (B3LYP) | High | ||

| 42% (PBEh-3c) | Medium | ||

| 100% (HF) | Lower | ||

| Triple-Zeta (TZ) | 6-311G*, def2-TZVP | 0% to 100% | Significantly Reduced |

| Quadruple-Zeta (QZ) | def2-QZVP | 0% to 100% | Approaching Zero (Near CBS) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Error-Resolved Calculations

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| def2 Basis Sets (def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, def2-QZVP) | A family of efficient, modern atomic orbital basis sets designed for SCF calculations, offering a better cost/accuracy ratio than older sets [1]. | def2-TZVP is recommended for accurate single-point energies where computationally feasible. |

| Counterpoise (CP) Correction | An a posteriori correction scheme that calculates and subtracts the BSSE from intermolecular interaction energies [2] [1]. | Essential for any interaction energy calculation with basis sets smaller than QZ. Most major quantum chemistry packages have automated implementations. |

| Geometric Counterpoise (gCP) | An empirical, approximate geometric correction for BSIE/BSSE that is computationally cheap and can be applied during geometry optimizations [1]. | Often integrated into composite methods like PBEh-3c. Ideal for pre-optimizing structures of large systems. |

| Dispersion Corrections (e.g., D3, D4) | Empirical add-ons that account for missing London dispersion interactions in many standard density functionals [1]. | Crucial for studying noncovalent interactions in drug-like molecules and supramolecular systems. |

| Composite Methods (e.g., PBEh-3c) | Integrated computational recipes that combine a functional, basis set, and empirical corrections for dispersion and BSIE to provide good accuracy for large systems at low cost [1]. | The recommended starting point for geometry optimizations of large molecular complexes and for screening in crystal structure prediction. |

Core Concepts: Why Chemical Environment Matters

What is the fundamental reason that basis set requirements differ between molecules and solids?

The primary difference lies in the electron density distribution. In isolated molecules, the electron density decays exponentially in the vacuum surrounding the molecule, requiring somewhat diffuse basis functions to accurately describe this asymptotic region. In contrast, the electron density in crystalline solids is much more uniform throughout the crystal, with no such vacuum regions, making very diffuse functions generally unnecessary and even problematic due to increased risk of linear dependencies from atomic orbital overlap in densely packed structures [3].

How does the type of chemical bonding in solids influence basis set choice?

The same chemical element can exhibit profoundly different chemical behavior in different crystal packings, each with distinct electron density characteristics [3]:

- Metallic bonds (e.g., bulk sodium): Electrons are quite spread out over the whole space

- Covalent bonds (e.g., diamond, graphene): Electron density is concentrated between atoms

- Ionic bonds (e.g., NaCl): Wave function is strongly confined near ions with nodes between neighboring atoms

- Dispersive bonds (e.g., molecular crystal Cl₂): Density is localized on molecules with empty space between them

This diversity means a "one-size-fits-all" basis set approach is inadequate for solid-state systems, unlike in molecular quantum chemistry where most molecules are relatively homogeneous in density and bonding [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Linear Dependency Errors

Problem: Calculation fails due to linear dependency in the basis set, often manifested as numerical instabilities, unphysical states, or catastrophic drops in total energy.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check condition number of the overlap matrix at the Γ-point. A high ratio between largest and smallest eigenvalue indicates linear dependency [3]. | Solids & Large Molecules |

| 2 | Apply dependency threshold using input keywords like DEPENDENCY bas=1d-4 to remove linearly dependent functions [4]. |

All systems with diffuse functions |

| 3 | Remove unnecessary diffuse functions - especially in solid-state calculations where they are rarely needed for ground state properties [3] [4]. | Densely-packed solids |

| 4 | Use system-specific optimized basis sets with algorithms like BDIIS (Basis-set Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) that minimize total energy while controlling condition number [3]. | System-specific optimizations |

| 5 | Avoid basis sets with numerous polarization functions, particularly augmented Dunning's and Ahlrichs' quadruple-ζ basis sets, which increase charge concentration in interatomic regions and exacerbate linear dependency [5]. | All system types |

Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE)

Problem: Unphysically strong binding energies due to artificial stabilization from neighboring atoms' basis functions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Approach | Methodology | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Counterpoise Correction | Calculate interaction energy as: ΔE = E(AB/AB) - E(A/AB) - E(B/AB) where "E(A/AB)" denotes energy of fragment A using the full AB basis set [6]. | Only exact for diatomic systems; becomes intractable for multi-atom clusters [6]. |

| Approximate Cluster Correction | Binding energy = Cluster total energy - Σ(atomic energies in total cluster basis set) [6]. | Does not properly correct many-body BSSE; approximate only [6]. |

| Valiron-Mayer Hierarchy | Systematic theory for counterpoise correction as hierarchy of 2-, 3-, ..., N-body interactions [6]. | Computationally intractable beyond few atoms (e.g., 125 calculations for 4-atom cluster) [6]. |

BSSE Correction Selection Workflow

Slow Basis Set Convergence

Problem: Correlation energies (particularly MP2) converge slowly with basis set size, requiring large basis sets for chemical accuracy.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Technique | Principle | Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Density-Based Basis Set Correction (DBBSC) | Uses coordinate-dependent range-separation function to characterize spatial incompleteness; missing short-range correlation computed via simple DFT energy correction [7]. | Near-basis-set-limit results with affordable basis sets; ~30% wall-clock time overhead vs conventional DH [7]. |

| Explicitly Correlated (F12) Theories | Incorporates interelectronic distances explicitly in wave function ansätze to improve convergence [7]. | Significantly reduces basis set size required for CBS limit; but increases computation time, disk and memory usage [7]. |

| Complementary Auxiliary Basis Set (CABS) | Correction known from F12 theory that improves HF energy [7]. | Low computational cost; can be combined with DBBSC [7]. |

| Local Approximations | Exploits rapid decay of electron-electron interactions with distance to reduce wave function parameters [7]. | Significant reduction in computational costs for extended systems [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the recommended basis set hierarchy for general calculations?

For standard calculations (energies, geometries), the following hierarchy provides increasing accuracy [4]:

Where:

- SZ: Single zeta - qualitative only

- DZ: Double zeta - reasonable for large molecules

- DZP: Double zeta polarized - minimum for hydrogen bonds

- TZP: Triple zeta polarized - extends valence space

- TZ2P: Additional polarization function (H: p+d; C: d+f)

- QZ4P: Core triple zeta, valence quadruple zeta with 4 polarization functions

Q2: When are diffuse functions absolutely necessary?

Diffuse functions are required for [4]:

- Small negatively charged atoms/molecules (F⁻, OH⁻)

- Accurate calculation of polarizabilities and hyperpolarizabilities

- High-lying excitation energies and Rydberg excitations

- Properties calculated through RESPONSE keyword

However, they increase linear dependency risk and should be used with dependency thresholds [4].

Q3: Which basis sets show reduced variability across different bond types?

For balanced performance across different bond classes, the following basis sets demonstrate reduced variability [5]:

- Def2TZVP (Triple-ζ Ahlrichs) - particularly recommended

- 6-31++G(d,p) and 6-311++G(d,p) (Pople-style)

- cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, and cc-pVQZ (Dunning's correlation-consistent)

Q4: What special considerations apply to solid-state calculations?

- System-specific optimization is often necessary due to diverse bonding environments [3]

- Avoid over-diffuse functions that cause linear dependency in packed structures [3]

- BDIIS algorithm can optimize exponents and contraction coefficients while controlling condition number [3]

- Large quadruple-ζ basis sets can be used successfully with proper optimization [3]

Experimental Protocols

System-Specific Basis Set Optimization (BDIIS Method)

Purpose: Optimize basis set exponents and contraction coefficients for specific chemical environment [3].

Methodology:

- Initialize with standard basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP)

- Iterate using BDIIS (Basis-set Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) algorithm:

- Compute gradients: ( ei^α = -\frac{∂Ω}{∂αi} ) and ( ei^d = -\frac{∂Ω}{∂di} )

- Update parameters: ( αn = α0 + \sum{i=1}^n ci ei^α ) and ( dn = d0 + \sum{i=1}^n ci ei^d )

- Minimize functional: ( Ω = E{tot} + γ·log[κ({α,d})] )

- ( E{tot} ): Total energy of system

- ( κ ): Condition number of overlap matrix at Γ-point

- ( γ ): Penalty parameter (typically 0.001)

- Converge when both energy and condition number are optimized

Applications: Prototypical solids (diamond, graphene, NaCl, LiH) with different bonding character [3].

BDIIS Optimization Algorithm

Counterpoise Correction for Diatomic Systems

Purpose: Eliminate BSSE in binding energy calculations for diatomic molecules [6].

Procedure:

- Calculate E(AB/AB): Energy of dimer in full dimer basis set

- Calculate E(A/AB): Energy of monomer A in full dimer basis set (ghost orbitals from B included)

- Calculate E(B/AB): Energy of monomer B in full dimer basis set (ghost orbitals from A included)

- Compute corrected binding energy: ( ΔE_{CP} = E(AB/AB) - E(A/AB) - E(B/AB) )

Note: This is the only rigorously correct approach for diatomic systems. For larger systems, approximations are necessary [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BDIIS Algorithm [3] | System-specific optimization of exponents and contraction coefficients | Minimizes total energy while controlling condition number; implemented in Crystal code |

| DBBSC Method [7] | Density-based basis-set correction for correlation energies | Enables near-basis-set-limit results with small basis sets; minimal computational overhead |

| CABS Correction [7] | Complementary auxiliary basis set improvement for HF energy | Often combined with DBBSC; low computational cost |

| def2-TZVP [5] | Triple-ζ quality basis set with polarization | Shows reduced variability across different bond classes; recommended for general use |

| ZORA Basis Sets [4] | Relativistic basis sets for heavy elements | Include scalar relativistic effects; essential for elements beyond Kr |

| Counterpoise Method [6] | BSSE correction for interaction energies | Exact for diatomic systems; approximate for clusters |

| Condition Number Monitoring [3] | Diagnostic for linear dependency | Critical when using extended basis sets in solids; should be < 10⁵-10⁶ |

| Local Approximations [7] | Reduction of computational cost | Exploits distance decay of interactions; essential for large systems |

Table: Essential computational tools for basis set management in different chemical environments

Fundamental Concepts: The Blessing and the Curse

What are diffuse functions and what is their primary purpose?

Diffuse functions are atomic orbital basis functions with very small exponents, meaning they are spatially extended and describe the electron density far from the nucleus. Their primary purpose is to accurately model non-covalent interactions (NCIs), such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and π-π stacking, which are crucial for understanding molecular recognition in drug discovery and materials science [8].

Why is using them considered a "conundrum"?

This creates the "conundrum of diffuse basis sets" [8]:

- The Blessing of Accuracy: They are often essential for achieving chemically accurate results, particularly for interaction energies. Without them, significant errors can occur.

- The Curse of Sparsity: They drastically reduce the sparsity (increase the number of non-negligible elements) of the one-particle density matrix (1-PDM). This negatively impacts computational performance, pushing back the onset of the linear-scaling regime in electronic structure calculations and increasing resource demands [8].

Guidelines for Use: When Are They Necessary?

For which specific types of calculations are diffuse functions critical?

They are most critical for properties and systems involving weak interactions or electron-dense regions:

- Non-Covalent Interaction Energies: Absolutely essential for obtaining quantitative accuracy for binding energies in complexes like drug-target interactions [8].

- Anions and Excited States: Systems with loosely bound electrons require diffuse functions for a physically correct description.

- Reaction Barrier Heights: Can significantly impact the accuracy of calculated energy barriers.

- Molecular Properties: Such as dipole moments and electron affinities.

The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of diffuse functions on the accuracy of interaction energies, demonstrating their necessity.

Table 1: Impact of Basis Set Augmentation on Calculation Accuracy Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for the ASCDB benchmark, calculated with the ωB97X-V functional. Lower values indicate better accuracy. Data adapted from a 2025 study [8].

| Basis Set | RMSD for NCIs (M+B) [kJ/mol] | Relative to unaugmented basis? |

|---|---|---|

| def2-TZVP | 8.20 | Unaugmented |

| def2-TZVPPD | 2.45 | Augmented with diffuse functions |

| cc-pVTZ | 12.73 | Unaugmented |

| aug-cc-pVTZ | 2.50 | Augmented with diffuse functions |

How do I decide if my system needs diffuse functions?

The following workflow diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting a basis set.

Troubleshooting & FAQ: Resolving Common Computational Issues

The calculation with my diffuse basis set is failing or behaving erratically. What could be wrong?

Numerical linear dependence in the basis set is a common culprit. This occurs when diffuse functions on different atoms become so overlapping that the overlap matrix is nearly singular, leading to numerical instability and nonsensical results (a strong indicator is a significant shift in core orbital energies) [9].

Solution: Activate dependency checks in your quantum chemistry software. For example, in ADF, use the DEPENDENCY keyword to invoke internal checks and countermeasures. You can adjust the threshold tolbas to control the elimination of linear combinations corresponding to very small eigenvalues in the virtual SFOs overlap matrix [9].

My interaction energies seem too favorable. Could this be related to the basis set?

Yes, this is a classic symptom of Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE). BSSE is an artificial lowering of the energy of a molecular complex due to the use of an incomplete basis set. Each monomer effectively uses the basis functions of the other to "patch" its own basis set incompleteness, making the binding appear stronger than it is [10].

Solution: Apply the Counterpoise (CP) Correction method. This technique calculates the energy of each monomer in the full complex's basis set, allowing for a correction that estimates the BSSE. Most major computational chemistry packages (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) have built-in functionality for this [10].

The computational cost with diffuse functions is prohibitive for my large system. What are my options?

This is a direct consequence of the "curse of sparsity." Several strategies exist:

- Use a Smaller Augmented Basis: Start with an augmented double-zeta basis (e.g., aug-cc-pVDZ) for initial scans before moving to larger sets for final single-point energies.

- Employ the CABS Singels Correction: Recent research proposes using the Complementary Auxiliary Basis Set (CABS) singles correction in combination with compact, low l-quantum-number basis sets as a promising solution to achieve good accuracy for non-covalent interactions without the full cost of a diffuse-augmented basis [8].

- Utilize Software with Linear-Scaling Algorithms: While diffuse functions impair sparsity, using codes designed to exploit sparsity can still provide performance benefits compared to conventional codes.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Counterpoise Correction for Interaction Energy

This protocol details the steps to obtain a BSSE-corrected interaction energy for a dimer A···B.

Objective: To calculate the BSSE-corrected interaction energy of a molecular complex. Method: Counterpoise (CP) Correction method [10].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the isolated monomers (A and B) and the complex (A···B) at an appropriate level of theory, preferably with a medium-sized basis set.

- Single-Point Energy Calculations:

- EAB(AB): Calculate the single-point energy of the complex in its own basis set.

- EA(A): Calculate the single-point energy of monomer A in its own basis set.

- EB(B): Calculate the single-point energy of monomer B in its own basis set.

- EA(AB): Calculate the "ghost" energy of monomer A in the full basis set of the complex (the basis functions of B are present as "ghost" functions without atoms/nuclei).

- EB(AB): Calculate the "ghost" energy of monomer B in the full basis set of the complex.

- Calculation:

- Uncorrected Interaction Energy: ΔEuncorrected = EAB(AB) - [EA(A) + EB(B)]

- BSSE for A: BSSEA = EA(A) - EA(AB)

- BSSE for B: BSSEB = EB(B) - EB(AB)

- Total BSSE: BSSEtotal = BSSEA + BSSEB

- Corrected Interaction Energy: ΔECP = ΔEuncorrected + BSSEtotal

Protocol: Mitigating Numerical Linear Dependence in ADF

This protocol addresses numerical instability when using very large, diffuse basis sets in the ADF software [9].

Objective: To stabilize a calculation suffering from numerical linear dependence.

Software: ADF.

Method: Using the DEPENDENCY input block.

- Identify the Problem: Check the output for warnings or implausible results (e.g., shifted core orbital energies).

- Modify Input: Add the following block to your ADF input file:

- Test Thresholds: The default

tolbasis a good starting point. If the calculation remains unstable, try a slightly larger value (e.g.,5e-4). It is critical to test different values and ensure results are consistent and physically meaningful. The number of functions deleted is printed in the output file for verification [9].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Basis Set Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Basis Sets | Provide a balanced starting point for molecular calculations. | def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ [8] |

| Augmented Basis Sets | Include diffuse functions for accurate modeling of NCIs, anions, and excited states. | def2-SVPD, def2-TZVPPD, aug-cc-pVXZ series (X=D, T, Q, ...) [8] |

| Basis Set Exchange | A repository to obtain and manage basis sets in formats for various computational codes. | https://www.basissetexchange.org [8] |

| Counterpoise Correction | A standard procedure implemented in quantum chemistry software to correct for BSSE. | Built-in functionality in Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS, etc. [10] |

| Dependency Checks | A software feature to mitigate numerical instabilities from (near-)linear dependence in the basis. | DEPENDENCY keyword in ADF [9] |

| CABS Singles Correction | An approach to improve accuracy without full diffuse augmentation, helping to alleviate the sparsity curse. | Method proposed for use with compact basis sets [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the immediate symptoms of a linearly dependent basis set in my calculation?

Numerical problems arise when basis or fit sets become almost linearly dependent. A strong indication that something is wrong is if the core orbital energies are shifted significantly from their values in normal basis sets. Results can become seriously affected and unreliable. The program may carry on without noticing the problem unless specific checks are activated [9].

FAQ 2: How can I proactively check for and counter linear dependence in my calculations?

You can activate the DEPENDENCY key in your input. This turns on internal checks and invokes countermeasures when the situation is suspect. The block can be controlled with threshold parameters like tolbas (for the basis set) and tolfit (for the fit set). When activated, the number of functions effectively deleted is printed in the output file's SCF section (cycle 1) [9].

FAQ 3: My system requires a large, diffuse basis set. What is a modern method to handle the resulting overcompleteness?

A method using a pivoted Cholesky decomposition of the overlap matrix can prune the overcomplete molecular basis set. This provides an optimal low-rank approximation that is numerically stable. The pivot indices determine a reduced basis set that remains complete enough to describe all original basis functions. This approach can yield significant cost reductions, with savings ranging from 9% fewer functions in single-ζ basis sets to 28% fewer in triple-ζ basis sets [11].

FAQ 4: Why should I be cautious about automatically applying dependency checks?

Application of the tolbas feature should not be fully automatic. It is recommended to test and compare results obtained with different threshold values. Some systems are much more sensitive than others, and the effect on results is not yet fully predictable by an unambiguous pattern. Choosing a value that is too coarse will remove too many degrees of freedom, while a value that is too strict may not adequately counter the numerical problems [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: The DEPENDENCY Key

The DEPENDENCY key is a crucial feature for managing potential linear dependence. The following table summarizes its main parameters. Note that application or adjustment of tolfit is generally not recommended as it can seriously increase CPU usage for usually minor gains [9].

Table: Parameters for the DEPENDENCY Input Block

| Parameter | Description | Default Value | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

tolbas |

Criterion applied to the overlap matrix of unoccupied normalized SFOs. Eigenvectors with smaller eigenvalues are eliminated. | 1e-4 |

In ADF2022+, a value of 5e-3 is used for GW calculations if unspecified. |

BigEig |

A technical parameter. Diagonal elements for rejected functions are set to this value during Fock matrix diagonalization. | 1e8 |

Off-diagonal elements for rejected functions are set to zero. |

tolfit |

Similar to tolbas, but applied to the overlap matrix of fit functions. |

1e-10 |

Not recommended for adjustment; fit set dependency is usually less critical. |

Experimental Protocol: Basis Set Pruning via Pivoted Cholesky Decomposition

This protocol details the procedure for curing basis set overcompleteness using a pivoted Cholesky decomposition, as referenced in the FAQs [11].

Objective: To generate a numerically stable, pruned basis set from an overcomplete atomic orbital basis, reducing computational cost while retaining accuracy.

Principle: The pivoted Cholesky decomposition of the molecular overlap matrix provides an optimal low-rank approximation. The pivot indices directly determine a non-redundant subset of the original basis functions.

Procedure:

- Input Overcomplete Basis: Start with a molecular calculation setup that uses a large atomic orbital basis set, typically one with multiple diffuse functions, which is suspected to be overcomplete.

- Compute Overlap Matrix: Calculate the overlap matrix S for the molecular basis set.

- Perform Pivoted Cholesky Decomposition: Apply the decomposition to the overlap matrix S. This process identifies a set of pivot indices.

- Select Pruned Basis Set: The pivot indices correspond to the basis functions in the original set that form the new, pruned basis. Functions not corresponding to pivots are eliminated.

- Proceed with Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform the primary calculation (e.g., SCF, MP2) using the pruned basis set. The cost reductions are most significant at the self-consistent field level and beyond.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving linear dependence issues, incorporating both the traditional dependency checks and the modern Cholesky approach.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Basis Set Error Resolution

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| DEPENDENCY Key (ADF) | An input block that activates internal checks and countermeasures for linear dependence in basis and fit sets [9]. |

| Pivoted Cholesky Decomposition | A numerical algorithm that prunes an overcomplete molecular basis set by providing an optimal low-rank approximation of the overlap matrix [11]. |

| Auxiliary Basis Set (RI/DF) | A separate, optimized basis set used to approximate products of primary basis functions, dramatically reducing the computational cost of electron correlation methods like MP2 [12]. |

| Threshold Parameter (tolbas) | A criterion that controls the sensitivity of the linear dependence check; eigenvectors of the overlap matrix with eigenvalues below this threshold are eliminated from the valence space [9]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) and why is it a critical problem in computational drug design?

BSSE is an inherent error in quantum chemical calculations that occurs when using finite basis sets to model molecular interactions. In drug design, it artificially lowers the calculated interaction energy between a protein and a ligand, leading to inaccurate predictions of binding affinity. This error can misdirect optimization efforts, as researchers may pursue compounds that appear promising computationally but fail in experimental testing, wasting significant time and resources. The error becomes particularly severe when using large basis sets with diffuse functions, which are often necessary for accurate modeling of non-covalent interactions but increase the risk of numerical instability and near-linear dependency in the basis set [10] [9].

Q2: My output file shows a significant number of deleted functions after using the DEPENDENCY key. Are my results still reliable?

The program automatically identifies and removes functions corresponding to very small eigenvalues in the overlap matrix, which are the primary contributors to numerical instability [9]. Your results are likely more reliable after this process, as the calculation has been stabilized. However, you should verify the result's stability by testing different tolbas values (e.g., 1e-4 and 5e-3) and ensuring that key energetic outputs, like binding energies, do not change significantly. A large number of deleted functions, however, may indicate that your basis set is too diffuse for the system [9].

Q3: How does uncertainty quantification in AI-driven drug discovery relate to traditional error quantification like BSSE in computational chemistry?

Both fields address the fundamental need to trust predictive models. BSSE is a specific, well-characterized form of error in quantum mechanics, countered with methods like the counterpoise correction [10]. In AI drug design, uncertainty quantification uses empirical, frequentist, and Bayesian approaches to measure the reliability of a model's predictions, such as the anticipated potency or toxicity of a newly generated molecule [13]. Quantifying this uncertainty is crucial for autonomous decision-making in the "design-make-test-analyse" cycle, as it allows the system to prioritize experiments with the highest chance of success, thereby reducing costly wet-lab failures [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unphysically large binding energy and shifted core orbital energies.

- Symptoms: Calculation completes, but the computed interaction energy is anomalously large (overly attractive). Core orbital energies in the output are significantly different from values obtained with standard basis sets.

- Primary Cause: Serious numerical problems due to near-linear dependence in a large, diffuse basis set [9].

- Resolution Steps:

- Activate Dependency Checks: In your input, use the

DEPENDENCYkey to turn on internal checks and countermeasures [9]. - Apply Default Settings: Initially, use only the

DEPENDENCYandEndkeywords. The defaults (tolbas=1e-4) are a good starting point [9]. - Test Threshold Sensitivity: Re-run the calculation with a stricter (e.g.,

1e-5) and a coarser (e.g.,5e-3)tolbasvalue. The5e-3value is used automatically for GW calculations in ADF2022+ [9]. - Compare Results: If key results (like binding energy) are highly sensitive to the

tolbasvalue, your basis set may be inappropriate for the system. Consider using a less diffuse basis.

- Activate Dependency Checks: In your input, use the

- Verification of Fix: A successful resolution is indicated by the restoration of realistic core orbital energies and a binding energy that is stable across small adjustments to the

tolbasparameter [9].

Problem: Counterpoise calculation for BSSE does not finish or crashes.

- Symptoms: A counterpoise correction job does not complete within the allocated time or fails with an error.

- Primary Cause: The system is too large or complex for the requested level of theory and basis set, or there is an issue with fragment definition.

- Resolution Steps:

- Check Fragment Definitions: Ensure the input file correctly specifies the number of fragments and the atoms belonging to each using the

counterpoise=Nkeyword [10]. - Simplify the Calculation: For an initial test, use a smaller basis set and a lower level of theory.

- Restartability: Check the software documentation. In some cases, counterpoise calculations can be restarted from a checkpoint file, but this is not always guaranteed to work [10].

- Seek Help: Provide your input file and output log to a forum or support service, as the error may be specific to the system or software version [10].

- Check Fragment Definitions: Ensure the input file correctly specifies the number of fragments and the atoms belonging to each using the

BSSE Resolution Parameters and Computational Cost

Table 1: Key parameters for the DEPENDENCY key in ADF and their effect on calculations. [9]

| Parameter | Default Value | Function | Effect of Increasing Value | CPU Time Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

tolbas |

1e-4 |

Threshold for eliminating virtual SFOs from the valence space. | Removes more functions, increasing stability but potentially reducing accuracy. | Lowers cost. |

BigEig |

1e8 |

Technical parameter; sets the diagonal Fock matrix element for rejected functions. | Minimizes influence of deleted functions on the SCF process. | Negligible. |

tolfit |

1e-10 |

Threshold for eliminating fit functions (not recommended for adjustment). | Removes more fit functions, potentially degrading the fit quality. | Can "seriously increase" CPU usage. [9] |

Impact of AI and Error Reduction on Drug Discovery Timelines

Table 2: Quantitative impact of AI and robust computational methods on drug discovery efficiency (2024-2025).

| Metric | Traditional Process | AI & Error-Aware Computational Process | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hit-to-Lead Optimization | Several months [14] | Several weeks [14] | Industry Reporting [14] |

| Overall Discovery Timeline | 5-6 years [14] [15] | 1-2 years [14] [15] | Industry Reporting [14] [15] |

| Cost of Discovery (Preclinical) | Baseline | 30-40% reduction [16] | Market Analysis [16] |

| Clinical Trial Success Rate | ~10% [16] | Increased probability of success [16] | Market Analysis [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: BSSE-Corrected Interaction Energy Calculation

Methodology for quantifying protein-ligand binding affinity with error correction.

System Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structures of the protein and ligand. Optimize the geometry of the isolated ligand using an appropriate level of theory (e.g., DFT with a medium-sized basis set).

- Define the binding site and extract a relevant cluster model of the protein, ensuring key amino acid residues are included.

- Generate input files for three distinct systems: the protein fragment (A), the ligand fragment (B), and the protein-ligand complex (AB).

Single-Point Energy Calculations with Counterpoise Correction:

- For each of the three systems (A, B, AB), perform a single-point energy calculation at a high level of theory (e.g., DFT with a large basis set like cc-pVDZ).

- Crucially, each calculation must be done using the full, supersystem basis set. This means the calculation for fragment A is performed in the basis set of A and B, even though the coordinates of B are present as "ghost" atoms. This corrects for the BSSE [10].

- The keyword

counterpoise=2should be used to specify the number of fragments in the AB complex calculation [10].

Energy Extraction and Analysis:

- From the output files, extract the corrected energies for the protein (EA), the ligand (EB), and the complex (E_AB), all computed in the full dimer basis set.

- Calculate the BSSE-corrected interaction energy (ΔE_corrected) using the formula:

- ΔEcorrected = EAB - EA - EB

Uncertainty Quantification via Dependency Control:

- Re-run the single-point calculations for the complex (AB) with the

DEPENDENCYkey activated to manage numerical instability. - Systematically vary the

tolbasparameter (e.g.,1e-5,1e-4,1e-3) and recalculate ΔE_corrected. - The variation in ΔE_corrected across these thresholds provides a practical estimate of the numerical uncertainty in your final binding affinity prediction [9].

- Re-run the single-point calculations for the complex (AB) with the

Protocol 2: AI-Driven Molecular Design with Uncertainty Quantification

Methodology for de novo molecular generation with integrated uncertainty checks.

Model Training and Calibration:

- Train a generative AI model (e.g., a variational autoencoder or a generative adversarial network) on a large dataset of known drug-like molecules and their properties.

- Implement a Bayesian neural network or use methods like Monte Carlo dropout to allow the model to not only make predictions (e.g., predicted binding affinity) but also estimate its own uncertainty for each prediction [13].

Generative Design Loop:

Candidate Selection and Prioritization:

- Filter generated molecules based on both desired property values and low prediction uncertainty.

- Molecules with promising predicted properties but high uncertainty can be flagged for early, low-cost validation (e.g., fast molecular docking) before committing to more expensive simulations or synthesis [13].

- The selected high-confidence candidates are then passed to the "make" phase for synthesis and subsequent experimental testing [13].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential software and computational reagents for error-aware drug and material design.

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Role in Error Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADF (Amsterdam Modeling Suite) [9] | Software Suite | Quantum chemical calculations for materials and drug discovery. | Implements the DEPENDENCY key for automatic identification and removal of linearly dependent basis functions to ensure numerical stability. |

| Counterpoise Correction [10] | Computational Method | A standard procedure for calculating BSSE-corrected interaction energies. | Directly corrects for the Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) in non-covalent interaction calculations. |

| Generative AI Platform (e.g., deepmirror) [17] | AI Software | Uses foundational models to generate novel molecular structures and predict properties. | Reduces design errors by predicting efficacy and side effects early; some platforms integrate uncertainty estimates for predictions. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Models [13] | AI/ML Methodology | Uses Bayesian, frequentist, or empirical approaches to estimate prediction confidence. | Quantifies the reliability of AI model outputs, allowing researchers to filter out high-uncertainty, and therefore high-risk, candidate molecules. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cloud (e.g., Google Cloud Vertex AI) [18] | Infrastructure | Provides scalable computing resources for demanding simulations and AI training. | Enables the rapid testing of multiple parameters (e.g., various tolbas values) and complex UQ methods that are computationally prohibitive on local machines. |

Strategic Basis Set Selection and Optimization for Real-World Applications

In quantum chemistry calculations, a basis set is a set of mathematical functions used to represent the electronic wave function, turning partial differential equations into algebraic equations suitable for computational implementation [19]. The choice of basis set is crucial, as it significantly determines the accuracy and computational cost of your calculations [20]. This guide focuses on three prominent basis set families—def2, cc-pVXZ, and pc-n—providing researchers with clear protocols for their effective application and troubleshooting within computational chemistry workflows, particularly in drug development research.

Basis Set Families at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and primary use cases for the three basis set families discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Basis Set Families

| Basis Set Family | Key Characteristics | Primary Use Cases | Contraction Type | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| def2 (Ahlrichs) [21] | Segmented contraction; part of the "Karlsruhe" basis sets [21]. | DFT calculations (e.g., def2-TZVP); post-HF methods (e.g., def2-TZVPP) [21]. | Segmented [21] | Available for nearly all elements from H to Rn [21]. |

| cc-pVXZ (Dunning) [19] | "Correlation-consistent" design; systematic structure (X = D, T, Q, 5...) [19] [21]. | Correlated wave function methods (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T)) [22] [21]. | Generally contracted [21] | Designed for smooth extrapolation to the complete basis set (CBS) limit [19]. |

| pc-n (Jensen) [20] | "Polarization-consistent" design; optimized for DFT [20] [21]. | Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock calculations [21]. | Segmented (pcseg-n variants) [21] | Computationally efficient for target accuracy; property-optimized variants available (e.g., pcSseg-n for NMR) [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How do I choose the right basis set for my specific calculation?

Selecting the appropriate basis set depends on your computational method, desired accuracy, and the chemical system. Use the workflow below to guide your selection.

Experimental Protocol for Basis Set Selection:

- Define Target Accuracy: Establish an acceptable error margin (e.g., for reaction energies, specify a target in kcal/mol) [20].

- Perform a Calibration Study: Run calculations on a model system representative of your full research system using different basis sets from the recommended family.

- Analyze Convergence: Monitor key properties (energy, gradients). A recommended practice is to start with a double-zeta quality basis (e.g., pcseg-1 [20], def2-SVP [21]) and systematically increase to triple-zeta (e.g., pcseg-2, def2-TZVP, cc-pVTZ). The point where the property of interest changes negligibly with increasing basis set size indicates convergence.

- Apply to Research System: Use the calibrated basis set for production calculations on your target system.

FAQ 2: I am getting poor thermochemistry results with a triple-zeta basis. What is wrong?

Problem: A common pitfall is using the 6-311G family for valence chemistry calculations. Despite its name suggesting triple-zeta quality, its performance is more akin to a double-zeta basis set due to poor parameterisation, leading to significant errors [20].

Solution:

- Avoid the 6-311G family for general thermochemistry calculations [20].

- Use a verified triple-zeta basis set such as

pcseg-2ordef2-TZVPP[20] [21]. - Always include polarization functions for atoms involved in bonding. Unpolarized basis sets (e.g., 6-31G, 6-311G) have very poor performance, as polarization functions (e.g., adding d-functions to carbon) are essential to capture the electron distribution distortion during bond formation [20].

FAQ 3: When are diffuse functions necessary?

Problem: Standard basis sets may not adequately describe electron densities that are far from the nucleus.

Solution: Add diffuse functions (often denoted by + or aug-) in these specific cases [19]:

- Anions and weak interactions: Electrons in anions are more loosely bound and occupy larger orbitals. Diffuse functions are critical for accurate electron affinity calculations [24].

- Non-covalent interactions: For simulating van der Waals forces, stacking, or hydrogen bonding in drug-receptor interactions.

- Systems with lone pairs or large dipole moments.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Basis Set Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate reaction energies/ thermochemistry [20] | Use of unpolarized basis sets (e.g., 6-31G) or the 6-311G family. | Switch to a polarized double-zeta basis (e.g., 6-31G, pcseg-1) or a verified triple-zeta basis (e.g., pcseg-2). |

| Poor description of anions or weak interactions [24] | Lack of diffuse functions. | Use an augmented/diffuse-augmented basis set (e.g., aug-cc-pVDZ, 6-31+G*). |

| Numerical instability/linear dependence [9] | Very large basis sets with diffuse functions on atoms in dense environments. | Use the DEPENDENCY key in ADF to invoke internal checks, or slightly reduce the basis set size [9]. |

| Inefficient calculations for large molecules | Use of a generally contracted basis set (e.g., cc-pVXZ) in programs optimized for segmented contraction [21]. | For DFT on large systems, consider a segmented basis set like def2-SVP or pcseg-1 for better performance [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Access/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Set Exchange (BSE) Library | Centralized repository to obtain basis sets in formats for various quantum chemistry software (GAMESS, Gaussian, etc.) [21]. | https://www.basissetexchange.org/ |

| Segmented Contracted Basis Sets | Basis sets (e.g., pcseg-n, def2) where each Gaussian primitive contributes to a single basis function. Often computationally faster in many programs [21]. | Example: pcseg-1, def2-TZVP |

| Generally Contracted Basis Sets | Basis sets (e.g., cc-pVXZ) where primitives contribute to multiple basis functions. Can be more accurate but sometimes less efficient in certain program implementations [21]. | Example: cc-pVTZ |

| Property-Optimized Basis Sets | Basis sets designed for specific molecular properties, helping to separate method error from basis set error [23]. | Example: pcSseg-n for NMR shielding constants [23]. |

| Pseudopotential/Basis Set Combinations | Consistent sets for calculations on heavier elements, where core electrons are replaced by an effective potential. | Example: def2 series with matching effective core potentials [21]. |

Key Takeaways for Robust Calculations

To minimize basis set dependency errors in your research:

- Do not use unpolarized minimal basis sets like STO-3G for research-quality publication [25].

- Avoid the 6-311G family for thermochemical and valence chemistry calculations; opt for

pcseg-2ordef2-TZVPPfor triple-zeta quality [20]. - Select a basis set family matched to your electronic structure method:

pc-n/def2for DFT,cc-pVXZfor correlated wavefunction methods [21]. - Always include diffuse functions for anions, weak interactions, and accurate barrier height calculations [24].

- Leverage the Basis Set Exchange to ensure you are using correctly formatted basis sets for your chosen computational package [21].

In the computational modeling of molecules and materials, the choice of the basis set—a set of mathematical functions used to represent the electronic wavefunction—is a critical determinant of the accuracy and reliability of the results. Unlike molecular quantum chemistry, where systems are relatively homogeneous, crystalline solids exhibit remarkable diversity in chemical bonding. The same element can display metallic, ionic, covalent, or dispersive character across different compounds, creating a fundamental challenge for quantum chemical modeling [3]. This variability necessitates a more sophisticated approach to basis set selection than the standardized libraries commonly used for molecular systems.

The BDIIS (Basis-set Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) algorithm represents a system-specific solution to this challenge. Developed for use with Gaussian-type orbitals in periodic systems, BDIIS performs an automated optimization of both the exponents (αj) and contraction coefficients (dj) of the basis functions, tailoring them to the specific chemical environment of the solid material being studied [3]. This system-aware optimization enables researchers to achieve higher accuracy while potentially using smaller, more computationally efficient basis sets—a crucial consideration for the complex systems encountered in drug development and materials science.

Technical Foundation of the BDIIS Method

Mathematical Formulation

The BDIIS method operates within the framework of linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO), where crystalline orbitals (ψ) are expressed as linear combinations of Bloch functions (φ), which are in turn constructed from atom-centered functions [3]. Each atomic orbital is represented as a contraction of primitive Gaussian-type functions:

φμ(r) = ∑j dj · G(αj, r) [3]

Where:

- dj = contraction coefficients

- αj = exponents of the radial component

- G(αj, r) = Gaussian-type function

The BDIIS algorithm optimizes these parameters through an iterative procedure where at each step n, exponents and contraction coefficients are obtained as a linear combination of trial vectors from previous iterations [3]:

αn = αn-1 + ∑i ci · eiα

dn = dn-1 + ∑i ci · eid

Core Optimization Functional

The algorithm minimizes a specialized functional that combines the system's total energy with a penalty term addressing numerical stability:

Ω({α,d}) = E({α,d}) + γ·log₁₀[κ({α,d})] [3]

Where:

- E({α,d}) = total energy of the system

- κ({α,d}) = condition number of the overlap matrix

- γ = weighting parameter (typically 0.001)

The inclusion of the condition number penalty is crucial for preventing the onset of linear dependence issues that can arise as basis sets become more complete, which is particularly problematic in solid-state calculations with closely packed atoms [3].

BDIIS Workflow and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the iterative optimization procedure of the BDIIS algorithm:

BDIIS Algorithm Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Common BDIIS Implementation Challenges

Convergence Issues

Problem: Oscillatory behavior or failure to converge

- Root Cause: Poor initial guess for basis set parameters or excessively large step sizes in the optimization.

- Solution: Implement damping factors in the DIIS extrapolation or switch to more conservative optimization algorithms (e.g., steepest descent) for early iterations before transitioning to full BDIIS.

- Verification: Monitor both the energy change and the gradient norms. Genuine convergence should show systematic reduction in both quantities.

Problem: Convergence to unphysical solutions

- Root Cause: Penalty function weight (γ) may be too small to effectively prevent linear dependence.

- Solution: Increase γ gradually until stable convergence is achieved, with typical values ranging from 0.001 to 0.01 depending on the system.

- Verification: Check the condition number of the overlap matrix throughout optimization. Values exceeding 10⁸ typically indicate emerging linear dependence problems [3].

Numerical Instabilities

Problem: Catastrophic energy drops or unphysical states

- Root Cause: Manifestation of linear dependence in the basis set, leading to numerical singularities.

- Solution: The condition number penalty in the BDIIS functional specifically addresses this issue. Ensure this term is properly implemented and weighted.

- Verification: Regularly compute the determinant of the overlap matrix during optimization. A rapidly approaching zero value signals imminent numerical problems [3].

Problem: Poor performance with diffuse functions

- Root Cause: Overly diffuse basis functions in solid-state systems where electron density is more uniform than in molecules.

- Solution: Implement tighter constraints on the lower bounds for exponents or use dual basis set techniques that handle diffuse functions separately [3].

- Verification: Compare the optimized exponents with those from molecular basis sets. Solid-optimized exponents should generally be less diffuse.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does BDIIS differ from standard basis set optimization methods? BDIIS adapts the established DIIS (Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) technique, widely used for SCF convergence, to the basis set optimization problem. Unlike manual or grid-based optimization approaches, BDIIS utilizes information from previous iterations to accelerate convergence and avoid oscillatory behavior, similar to how GDIIS (Geometry DIIS) works for molecular geometry optimization [3].

Q2: For which types of systems is BDIIS particularly advantageous? BDIIS shows exceptional utility for solids with diverse bonding environments or polymorphic materials where the same element exhibits different chemical behavior. Examples include carbon allotropes (diamond vs. graphene), ionic salts like NaCl, and systems with mixed bonding character [3]. The system-specific optimization enables a single approach to handle this diversity rather than requiring pre-optimized basis set libraries for each bonding type.

Q3: What are the computational demands of BDIIS optimization? While the initial optimization requires multiple energy and gradient evaluations, making it computationally intensive, this cost is amortized when the optimized basis set is used for multiple calculations on similar materials. For high-throughput studies or investigations of similar systems, the initial investment typically pays dividends in improved accuracy and potentially smaller basis set sizes.

Q4: Can BDIIS be combined with other electronic structure methods? Yes, BDIIS is method-agnostic regarding the electronic structure theory used for energy evaluations. It has been demonstrated at both Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock levels [3]. The algorithm could potentially be extended to correlated methods, though the computational cost would increase significantly.

Q5: How does BDIIS address the fundamental trade-off between basis set completeness and linear dependence? The core innovation of BDIIS is the explicit inclusion of the overlap matrix condition number in the optimization functional. This creates a natural balancing between improving accuracy (lowering energy) and maintaining numerical stability (controlling condition number), allowing the algorithm to navigate this trade-off systematically rather than relying on heuristics or manual intervention [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Key Computational Resources for Basis Set Optimization Research

| Resource/Tool | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs) | Fundamental basis functions for electron wavefunction representation | Composed of radial Gaussian functions and spherical harmonics [3] |

| Condition Number Monitoring | Prevents numerical instabilities from linear dependence | Critical for managing overlap matrix stability in optimization [3] |

| BDIIS Algorithm | System-specific optimization of exponents and contraction coefficients | Implemented in CRYSTAL code; uses DIIS-inspired parameter update [3] |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets | Enables RI approximation for electron repulsion integrals | Reduces computational cost for MP2, CC2 methods; must be optimized for specific orbital basis sets [26] |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) | Reduces computational cost by replacing core electrons | Particularly important for heavy elements (Rb-Rn); includes scalar relativistic corrections [26] |

| Automatic Differentiation (AD) | Enables efficient gradient computation for optimization | Emerging technique for basis set optimization in quantum chemistry [27] |

Advanced Protocols: Basis Set Optimization Workflow

System Preparation and Initialization

Step 1: System Characterization

- Analyze the chemical bonding environment (metallic, ionic, covalent, dispersive)

- Identify key electronic features requiring accurate description (e.g., band gaps, reaction barriers)

- Determine appropriate initial basis set based on chemical intuition and prior knowledge

Step 2: Parameter Initialization

- Select initial basis set exponents and contraction coefficients from standard libraries

- Set appropriate bounds for exponent optimization to maintain numerical stability

- Define convergence thresholds for energy (typically 10⁻⁶ - 10⁻⁸ Ha) and gradient norms

BDIIS Optimization Procedure

Step 3: Iterative Optimization Cycle

- Compute total energy and energy gradients with respect to basis set parameters

- Evaluate overlap matrix condition number and compute penalty function

- Apply DIIS extrapolation to update basis set parameters

- Check convergence criteria; if not met, return to step 1

Step 4: Validation and Verification

- Compare results with larger standard basis sets to ensure improvement

- Verify physical reasonableness of optimized basis functions

- Test transferability to similar chemical systems when applicable

The relationship between basis set optimization and broader electronic structure calculations can be visualized as follows:

Basis Set Optimization Context

Integration with Drug Development Research

For researchers in pharmaceutical development, accurate molecular modeling is essential for understanding drug-target interactions, predicting binding affinities, and optimizing lead compounds. The BDIIS algorithm offers particular value in modeling:

Solid Form Optimization: Pharmaceutical materials frequently exist in multiple polymorphic forms with different stability, solubility, and bioavailability characteristics. The system-specific optimization provided by BDIIS enables more accurate prediction of relative polymorph stability and crystal packing arrangements.

Non-Covalent Interactions: Drug-receptor binding often involves delicate dispersion interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π-stacking—all of which require carefully optimized basis sets for accurate description. The tailored approach of BDIIS provides a path to systematically improve the description of these interactions without resorting to excessively large, computationally prohibitive basis sets.

While drug development proceeds through defined phases—discovery, preclinical research, clinical research, FDA review, and safety monitoring [28]—computational modeling plays a crucial role primarily in the discovery and early preclinical phases. The ability to rapidly and accurately screen potential drug candidates in silico can significantly accelerate the initial stages of the development pipeline [29].

The resolution-of-the-identity (RI) approximation, which relies on optimized auxiliary basis sets, has been particularly valuable in reducing the computational cost of electron correlation methods like MP2 and CC2 [26]. For drug discovery applications, these more accurate methods can provide improved description of dispersion interactions and binding energies, potentially reducing late-stage attrition due to insufficient efficacy.

Table: Basis Set Requirements Across Electronic Structure Methods

| Method | Basis Set Requirements | BDIIS Optimization Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock/DFT | Moderate size (double-ζ to triple-ζ) | Improved efficiency for solid-state applications [3] |

| MP2/CC2 | Larger basis sets with diffuse functions | RI approximation with optimized auxiliary basis reduces cost [26] |

| VQE (Quantum) | Minimal basis sets due to device limitations | Optimal compact representation for NISQ era devices [27] |

| Periodic Systems | Balance between completeness and linear dependence | System-specific optimization for diverse bonding environments [3] |

Future Directions and Methodological Extensions

The development of BDIIS represents part of a broader trend toward more flexible, system-aware approaches to basis set selection in quantum chemistry. Several promising directions for further development include:

Transferable Optimizations: Developing protocols for transferring optimized basis sets from prototypical systems to new materials with similar bonding characteristics, reducing the need for system-specific optimization in every case.

Multi-Fidelity Approaches: Implementing hierarchical optimization strategies where lower-level methods provide initial guesses for more accurate but computationally intensive methods.

Machine Learning Integration: Combining BDIIS with machine learning approaches to predict good starting points for optimization or to develop basis sets that are transferable across classes of materials.

Quantum Computing Applications: Developing specifically optimized basis sets for use on quantum computers, where extremely compact representations are essential due to the limited number of qubits available in current hardware [27].

As quantum chemical methods continue to play an expanding role in materials design and drug discovery, system-specific basis set optimization techniques like BDIIS will become increasingly important tools for achieving accurate results with manageable computational cost.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My DFT calculations are inaccurate for non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonding. What can I do? Consider using density-corrected DFT (HF-DFT), where the density from Hartree-Fock calculations is used with your DFT functional. This approach has been shown to significantly improve accuracy for non-covalent interactions dominated by electrostatic components, such as hydrogen and halogen bonds, while maintaining reasonable computational cost [30].

Q2: How can I achieve coupled-cluster quality energies without the computational cost? Machine learning correction schemes, particularly Δ-learning, can predict coupled-cluster energies using DFT densities as input. This approach learns the difference between DFT and coupled-cluster energies, dramatically reducing the amount of training data needed and allowing quantum chemical accuracy (errors below 1 kcal·mol⁻¹) at essentially the cost of a standard DFT calculation [31].

Q3: When should I prefer Hartree-Fock over DFT methods? HF can outperform DFT for specific systems where electron delocalization error in DFT becomes problematic. Recent research indicates HF provides superior results for zwitterionic systems with significant localization effects, more accurately reproducing experimental dipole moments and structural parameters where many DFT functionals fail [32].

Q4: What is a cost-effective computational workflow for predicting redox potentials in high-throughput screening? A hierarchical approach provides the best balance: start with force field geometry optimizations, followed by DFT single-point energy calculations with an implicit solvation model. Research on quinone-based electroactive compounds shows this workflow offers accuracy comparable to full DFT optimizations with solvation at significantly lower computational cost [33].

Q5: Which methods reliably predict structures for flexible molecules with soft degrees of freedom? Benchmark studies on carbonyl compounds reveal that method performance varies significantly. For challenging systems like ethyl esters, the selection of functional and basis set is critical, as routine methods like MP2/6-311++G(d,p) can produce inaccurate dihedral angles. Testing multiple methods against known experimental data is recommended [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inaccurate Energetics in DFT

Problem: DFT calculations yield poor reaction energies, barrier heights, or interaction energies.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Assess the exchange-correlation functional:

- For systems dominated by dynamical correlation: Hybrid functionals with 25% HF exchange (e.g., PBE0, B3LYP) often provide good compromises [30].

- For systems with significant nondynamical correlation: Pure GGAs or meta-GGAs might outperform hybrids, or consider double-hybrid functionals [30] [35].

- For long-range interactions: Range-separated hybrids (e.g., ωB97X, CAM-B3LYP) correct the improper asymptotic behavior of standard functionals [36].

Implement density correction (HF-DFT):

- Calculate the electron density using Hartree-Fock.

- Use this HF density to compute the energy with your chosen DFT functional.

- This approach mitigates self-interaction error and is particularly beneficial for noncovalent interactions [30].

Consider machine learning correction:

- For system-specific studies, train a Δ-DFT model to learn the difference between your DFT method and a higher-level theory like CCSD(T) [31].

Guide 2: Managing Computational Cost for Large Systems or High-Throughput Screening

Problem: Quantum chemical calculations become prohibitively expensive for large molecules or virtual screening of numerous compounds.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Implement a hierarchical screening approach:

Computational Workflow for High-Throughput Screening

Optimize basis set selection:

- Use double-ζ with polarization for geometry optimizations.

- Apply triple-ζ with multiple polarization functions for final energy calculations.

- Explore composite schemes that combine calculations with different basis sets.

Leverage machine learning potentials:

- For molecular dynamics simulations, develop ML potentials trained on high-level data.

- These can provide quantum chemical accuracy at dramatically reduced cost after initial training [31].

Guide 3: Correcting for Systematic Errors in Method Selection

Problem: Consistent errors appear across multiple calculations due to functional limitations.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Identify the error source:

- Self-interaction error: More prominent in pure DFT functionals; hybrid functionals with HF exchange reduce this error [36].

- Dispersion interactions: Most standard functionals poorly describe van der Waals forces; add empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., D3, D4) [30] [35].

- Delocalization error: Affects systems with stretched bonds or charge transfer; range-separated hybrids often improve performance [36] [32].

Apply targeted corrections:

- For dispersion: Always include empirical dispersion corrections for noncovalent interactions.

- For reaction barriers: Hybrid functionals with ~40% HF exchange often provide better performance.

- For transition metals: Hybrid functionals like B3LYP or TPSSh are generally recommended [35].

Method Performance Comparison

Table 1: Accuracy and Cost of Quantum Chemical Methods

| Method | Computational Cost | Typical Applications | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Low | Initial geometries, zwitterions, systems requiring localization [32] | No self-interaction error, computationally inexpensive | Neglects electron correlation, poor thermochemistry |

| Pure DFT (GGA) | Low-Medium | Geometry optimizations, large systems [35] [36] | Good structures, reasonable energetics for cost | Self-interaction error, poor barriers and noncovalent interactions |

| Hybrid DFT | Medium | General purpose, organic chemistry, transition metals [35] | Good balance for diverse properties, reduced self-interaction error | Higher cost than pure DFT, still imperfect for weak interactions |

| Meta-GGA | Medium | Improved energetics, molecular structures [36] [35] | Better performance than GGA, still reasonable cost | Increased sensitivity to integration grid [30] |

| Double Hybrids | High | Benchmark-quality energetics [35] | High accuracy for thermochemistry | Very high computational cost |

| MP2 | High | Noncovalent interactions, initial benchmark studies [34] | Good for dispersion, systematic improvement | Fails for metallic systems, expensive |

| CCSD(T) | Very High | Gold standard for energetics [31] | Highest accuracy for correlation energy | Prohibitive cost for large systems |

Table 2: Performance of Select DFT Functionals for Redox Potential Prediction (RMSE in V) [33]

| Functional | Type | Gas-Phase OPT | Gas-Phase OPT + Implicit Solvation SPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | GGA | 0.072 | 0.050 |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | 0.061 | 0.045 |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | 0.064 | 0.047 |

| M08-HX | Hybrid | 0.061 | 0.047 |

| HSE06 | Hybrid | - | 0.045 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Δ-DFT for Quantum Chemical Accuracy

Purpose: Achieve CCSD(T) accuracy at DFT cost for system-specific potential energy surfaces [31].

Methodology:

Generate training data:

- Select diverse molecular geometries from DFT-based molecular dynamics.

- Compute CCSD(T) energies for these configurations.

Train machine learning model:

- Use kernel ridge regression or similar algorithm.

- Learn mapping Δ = ECCSD(T) - EDFT as functional of DFT density.

- Include molecular symmetries to reduce training data requirements.

Apply correction:

- For new configurations, compute standard DFT energy.

- Add ML-predicted Δ correction to obtain CCSD(T)-quality energy.

Validation: Compare corrected MD trajectories with explicit CCSD(T) calculations for select points.

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Screening of Electroactive Compounds

Purpose: Efficiently predict redox potentials for high-throughput screening of organic molecules [33].

Methodology:

Initial geometry generation:

- Convert SMILES to 3D structure using force field (OPLS3e) optimization.

Quantum chemical refinement:

- Optimize geometry using semi-empirical quantum mechanics (SEQM) or DFTB.

- Alternatively, use DFT with moderate functional/basis set.

Single-point energy calculation:

- Compute energies with higher-level DFT functional.

- Include implicit solvation (Poisson-Boltzmann model) for solution properties.

Property prediction:

- Calculate redox potential from energy differences.

- Use linear calibration against experimental data if necessary.

Optimization Note: Gas-phase optimization with implicit solvation single-point energy provides best accuracy/cost balance versus full solvation optimization [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software Package | Perform electronic structure calculations | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem [30] [32] |

| Chemical Databases | Data Resource | Access experimental and computational data | BindingDB, RCSB, ChEMBL, DrugBank [37] |

| Benchmark Suites | Test Set | Validate method performance | GMTKN55 [30] |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical Basis | Expand molecular orbitals | def2-QZVPP, def2-QZVPPD, cc-pVnZ [30] [34] |

| Empirical Dispersion Corrections | Add-on Correction | Improve description of weak interactions | DFT-D3, DFT-D4 [30] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary purpose of using an Effective Core Potential (ECP)? ECPs, also known as pseudopotentials, are used to simplify quantum chemical calculations for heavy elements (typically those beyond the first few rows of the periodic table) by replacing the chemically inert core electrons and the nucleus with an effective potential. This addresses two key challenges: the large number of electrons and significant relativistic effects in heavy atoms, which are crucial for accurate simulations [38] [39].

2. When should I use an ECP over an all-electron approach? As a general recommendation [40]:

- For elements heavier than Kr (Z=36): ECPs are most advantageous, especially if your system contains many such atoms.

- For elements up to Kr: You should typically use an all-electron approach to avoid sacrificing accuracy for marginal computational speed-up.

- For a single heavy atom in a system: An all-electron scalar relativistic method (like ZORA or DKH) may provide better accuracy and be almost as fast as an ECP approach.

3. My calculation with an ECP is giving wrong energies. What could be wrong?