Machine Learning Optimization of Inorganic Reactions: A New Paradigm for Accelerated Discovery and Development

This article explores the transformative impact of machine learning (ML) on optimizing inorganic reactions and compound discovery, a critical area for materials science and drug development.

Machine Learning Optimization of Inorganic Reactions: A New Paradigm for Accelerated Discovery and Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of machine learning (ML) on optimizing inorganic reactions and compound discovery, a critical area for materials science and drug development. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and scientists, covering foundational ML concepts tailored for inorganic chemistry, from predicting thermodynamic stability to navigating vast compositional spaces. The piece delves into specific methodologies, including ensemble models and high-throughput data analysis, and addresses practical challenges like data scarcity and model bias through strategies such as transfer learning. Finally, it examines the rigorous validation of ML predictions against experimental and computational benchmarks and synthesizes key takeaways, highlighting the future potential of ML to autonomously discover novel inorganic compounds with tailored properties for biomedical and clinical applications.

The Foundation: How Machine Learning is Redefining Inorganic Chemistry Exploration

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic compounds are fundamentally limited by the vastness of compositional space. Conventional methods for assessing thermodynamic stability, primarily through density functional theory (DFT) calculations or experimental trial-and-error, are computationally intensive and time-consuming, creating a significant bottleneck in materials development [1]. Machine learning (ML) offers a paradigm shift, enabling the rapid and accurate prediction of compound stability directly from chemical composition, thereby constricting the exploration space and accelerating the identification of synthesizable materials [1]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols for implementing an ensemble machine learning framework, ECSG, which mitigates model bias and achieves high-fidelity predictions of inorganic compound stability for research applications.

Workflow and Conceptual Framework

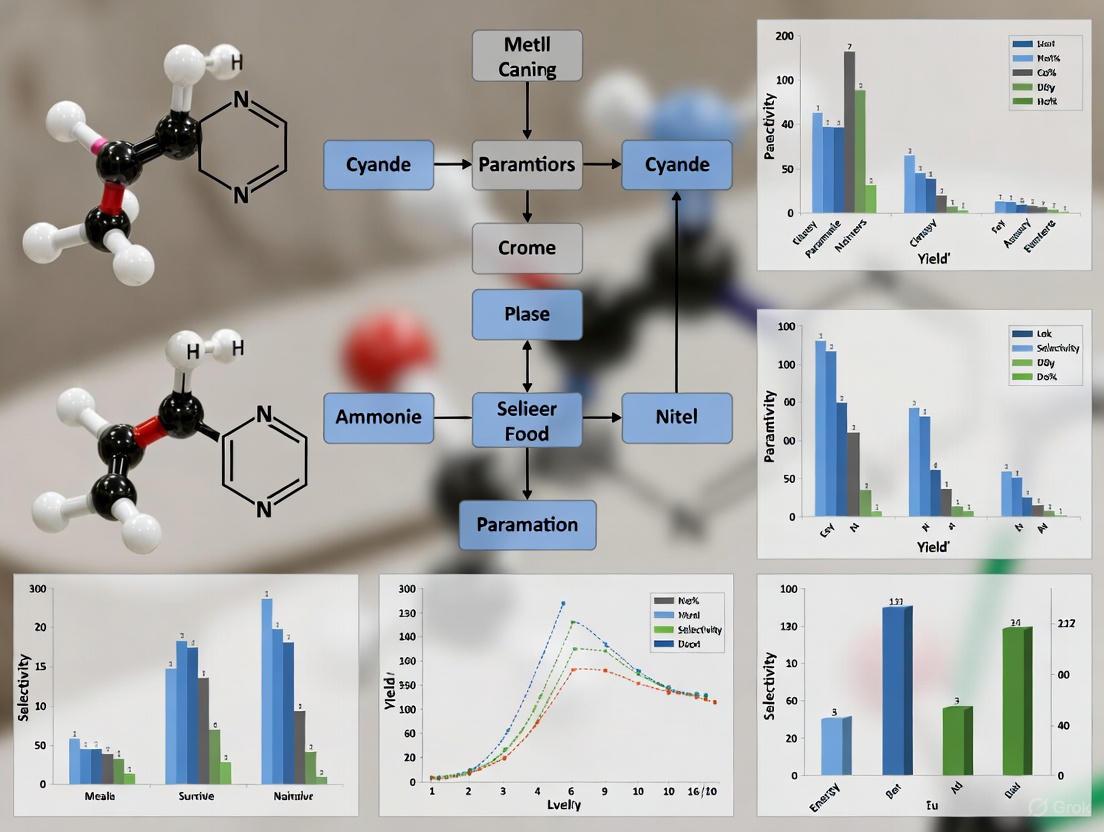

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for machine learning-guided discovery of stable inorganic compounds.

Figure 1. ML-Guided Discovery Workflow. This workflow outlines the iterative cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation for discovering stable inorganic compounds, facilitated by a machine learning framework that continuously improves with new data.

Core Computational Methodology

The ECSG Ensemble Framework

The Electron Configuration models with Stacked Generalization (ECSG) framework integrates three distinct composition-based models to minimize inductive bias and enhance predictive performance [1]. The framework operates on a two-level architecture:

- Base-Level Models: Three distinct models generate initial predictions based on different feature representations of the chemical composition.

- Meta-Level Model: A super learner model combines the outputs of the base-level models to produce the final, refined stability prediction [1].

Base-Level Model Specifications and Protocols

The ensemble's strength derives from the complementary knowledge domains of its constituent models.

Table 1. Base-Level Models in the ECSG Ensemble

| Model Name | Domain Knowledge | Input Feature Representation | Algorithm | Protocol for Feature Generation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECCNN [1] | Electron Configuration | 118 (elements) × 168 × 8 tensor encoding electron configuration | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Map elemental composition to a matrix representing the electron configuration of each constituent atom. |

| Magpie [1] | Atomic Properties | Statistical features (mean, deviation, range) of 22 elemental properties | Gradient-Boosted Regression Trees (XGBoost) | For a given composition, calculate statistical features (mean, mean absolute deviation, range, min, max, mode) across all included elements for properties like atomic number, mass, radius, etc. |

| Roost [1] | Interatomic Interactions | Complete graph of elements in the formula | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Represent the chemical formula as a graph where nodes are elements and edges represent interactions. An attention mechanism learns message-passing between atoms. |

Implementation Protocol for ECCNN:

- Input Preparation: Encode the material's composition into a 3D tensor of dimensions 118 × 168 × 8, representing the electron configurations of the constituent elements.

- Network Architecture:

- Pass the input through two convolutional layers, each using 64 filters with a 5×5 kernel.

- Apply batch normalization (BN) and a 2×2 max-pooling operation after the second convolution.

- Flatten the resulting feature maps into a one-dimensional vector.

- Feed the vector into a series of fully connected (dense) layers to generate the stability prediction [1].

- Training: Use standard backpropagation with an appropriate optimizer (e.g., Adam) and loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error) on a labeled dataset of known stable/unstable compounds.

Meta-Model and Ensemble Training Protocol

The stacked generalization procedure is implemented as follows:

- Base Model Training: Train the three base-level models (ECCNN, Magpie, Roost) on the training dataset.

- Cross-Validation Predictions: Use a k-fold cross-validation strategy on the training set to generate out-of-sample predictions from each base model. These predictions form the meta-features.

- Meta-Dataset Construction: Create a new dataset where each instance's input features are the cross-validated predictions from the three base models, and the target is the true stability label.

- Meta-Model Training: Train a meta-learner (e.g., a linear model or another XGBoost model) on this newly constructed dataset to learn how to best combine the base models' predictions [1].

Performance and Validation

The ECSG framework was validated against established benchmarks, demonstrating superior performance and efficiency.

Table 2. Quantitative Performance Metrics of the ECSG Model

| Metric | ECSG Performance | Comparative Model Performance | Evaluation Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | 0.988 | Not Reported | JARVIS Database [1] |

| Sample Efficiency | Achieves equivalent accuracy using 1/7 of the data | Requires 7x more data for same accuracy | JARVIS Database [1] |

| Validation Accuracy | Correctly identified stable compounds validated by subsequent DFT calculations | N/A | Case Studies: 2D wide bandgap semiconductors and double perovskite oxides [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Computational Tools and Databases for ML-Driven Inorganic Reaction Optimization

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) [1] | Database for acquiring training data on formation energies and compound stability. | Contains extensive DFT-calculated data for thousands of inorganic compounds. |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [1] | Database for acquiring training data on formation energies and compound stability. | A large repository of calculated thermodynamic and structural properties of materials. |

| JARVIS Database [1] | Database used for benchmarking model performance. | Includes a wide range of computed properties for materials. |

| Lifelong ML Potentials (lMLP) [2] | A continual learning approach for ML potentials that adapts to new data without catastrophic forgetting of previous knowledge. | Enables efficient, on-the-fly improvement of ML models during reaction network exploration. |

| Ensemble/Committee Model [1] | A technique for quantifying prediction uncertainty, crucial for active learning. | Uses predictions from multiple models to estimate confidence intervals and flag unreliable predictions. |

Application Notes: Case Studies

Exploration of Two-Dimensional Wide Bandgap Semiconductors

Objective: To identify novel, thermodynamically stable 2D semiconductors with wide bandgaps. Protocol:

- Define the target compositional space (e.g., specific ternary compounds).

- Screen thousands of candidate compositions using the pre-trained ECSG model to predict decomposition energy (ΔHd).

- Select top candidates with a high predicted likelihood of stability (negative ΔHd).

- Validate the stability of selected candidates using high-fidelity DFT calculations to confirm their position on the convex hull.

- Proceed with experimental synthesis and characterization of DFT-validated compounds [1].

Discovery of Double Perovskite Oxides

Objective: To accelerate the discovery of new double perovskite oxide structures with targeted functional properties. Protocol:

- The ECSG model was applied to navigate the unexplored composition space of double perovskites.

- The model successfully identified numerous novel perovskite structures predicted to be thermodynamically stable.

- Subsequent first-principles DFT calculations confirmed the remarkable accuracy of the model's predictions, validating the stability of the newly identified compounds [1].

The application of machine learning (ML) in chemistry represents a paradigm shift, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches to a more predictive and accelerated science. For researchers focused on inorganic reactions and drug development, understanding the core ML paradigms—supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid learning—is essential for leveraging these powerful tools. These methodologies are transforming how chemical processes are optimized, new materials are discovered, and synthesis pathways are designed by extracting meaningful patterns from complex chemical data. This article details the practical application of these ML paradigms, providing structured protocols and resources tailored for scientific and industrial research environments.

Core ML Paradigms and Their Chemical Applications

The selection of an ML paradigm is dictated by the nature of the available data and the specific chemical problem to be solved. The table below summarizes the primary characteristics and applications of each paradigm in chemistry.

Table 1: Core Machine Learning Paradigms in Chemistry

| ML Paradigm | Definition | Required Data | Common Algorithms | Exemplary Chemical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Learns a mapping function from labeled input-output pairs to predict outcomes for new data. | Labeled Data (e.g., reaction yields, stability labels) | Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Random Forest | Predicting reaction yields [3] [4], forecasting thermodynamic stability of compounds [1], and identifying synthetic pathways [5]. |

| Unsupervised Learning | Identifies hidden patterns or intrinsic structures from data without pre-existing labels. | Unlabeled Data (e.g., molecular structures, spectral readouts) | Clustering (e.g., k-means), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Exploratory analysis of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data, identifying novel clusters of molecular behavior from sensor readouts [6]. |

| Hybrid Learning | Combines supervised and unsupervised techniques to leverage both labeled and unlabeled data. | Both Labeled & Unlabeled Data | Custom workflows (e.g., unsupervised feature reduction followed by supervised regression) | Single-molecule identification from complex readouts where clear labels are scarce [6], and ensemble models for property prediction [1]. |

Detailed Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Supervised Learning for Multi-Objective Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines the use of the Minerva framework, a supervised Bayesian optimization approach, for optimizing chemical reactions with multiple objectives, such as maximizing yield and selectivity simultaneously [3].

1. Problem Definition and Objective Setting

- Define Objectives: Clearly specify the objectives to be optimized (e.g., yield, selectivity, cost). In the referenced study, the objectives were area percent (AP) yield and selectivity for a nickel-catalysed Suzuki reaction [3].

- Define Search Space: Enumerate all categorical and continuous reaction parameters to be explored. This includes catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, temperatures, and concentrations. The search space can be vast, encompassing tens of thousands of potential reaction conditions [3].

2. Initial Experimental Design

- Algorithmic Sampling: Use a quasi-random sampling algorithm, such as Sobol sampling, to select an initial batch of experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate). This ensures the initial data points are well-spread and diverse across the entire reaction condition space [3].

3. ML Model Training and Iteration

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor on the collected experimental data. The GP model predicts the reaction outcomes (yield, selectivity) and, crucially, the uncertainty of its predictions for all possible conditions in the search space [3].

- Candidate Selection: Use a multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI, or q-NEHVI) to select the next batch of promising experiments. This function balances the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of known high-performing regions [3].

- Iterative Loop: Repeat the cycle of running experiments, updating the model, and selecting new candidates until objectives are met or the experimental budget is exhausted. Convergence is typically reached within a few iterations [3].

4. Validation and Scale-Up

- Validation: Validate the top-performing conditions identified by the algorithm through replication.

- Scale-Up: Successfully scale up the optimized conditions, as demonstrated by its application in pharmaceutical process development for API syntheses [3].

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Protocol 2: Hybrid Learning for Inorganic Solid-State Synthesis Prediction

This protocol describes ElemwiseRetro, a hybrid graph neural network model that predicts synthesis recipes for inorganic crystals [5]. The model uses a supervised learning core but is built upon a formulation that leverages unsupervised, knowledge-driven rules for data preprocessing.

1. Data Curation and Formulation

- Source Element Masking: From the target material's composition, classify elements as either "source elements" (must be provided by precursors, e.g., metals) or "non-source elements" (can come from the environment, e.g., O, N). This is a rule-based, unsupervised preprocessing step [5].

- Precursor Template Library: Construct a library of viable precursor templates (e.g., carbonates, oxides) from historical synthesis data. This library acts as a constrained set of building blocks [5].

2. Model Architecture and Training

- Graph Representation: Encode the target inorganic crystal as a graph. Use a pre-trained model to generate node features that represent the chemical elements [5].

- Supervised Training: Train a graph neural network to predict the correct set of precursors. The model uses the source element mask to focus on relevant elements and then classifies the appropriate precursor template for each [5].

- Probability Scoring: The model outputs a joint probability for each predicted set of precursors, allowing for the ranking of synthesis recipes by confidence [5].

3. Prediction and Validation

- Recipe Generation: For a new target material, the model generates a ranked list of potential precursor sets and their associated probabilities.

- Confidence-Based Prioritization: Use the probability score to prioritize which recipes to test experimentally first. The ElemwiseRetro model achieved a top-1 accuracy of 78.6% and a top-5 accuracy of 96.1%, significantly outperforming a popularity-based baseline [5].

The workflow for this hybrid approach is as follows.

Protocol 3: Supervised Deep Learning for Forward Reaction Prediction

This protocol covers the use of the GraphRXN model, a supervised deep learning framework that predicts the outcome of organic reactions, such as yield, directly from molecular structures [7].

1. Data Preparation and Featurization

- Input Representation: Represent the reaction using SMILES strings or, preferably, as molecular graphs for reactants and products [7].

- Graph Featurization: For each molecule, represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges in a graph. Initialize node and edge features based on chemical properties [7].

2. Model Training

- Graph Neural Network: Employ a Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN). In each step, nodes (atoms) aggregate information from their neighbors (connected atoms) to update their own feature representation [7].

- Readout and Prediction: After several message-passing steps, a "readout" function aggregates all node features into a single, fixed-length vector representing the entire molecule. Vectors for all reaction components are then combined into a final reaction vector, which is fed into a fully connected neural network to predict the reaction output (e.g., yield) [7].

- Performance: When trained on high-quality HTE data, this model can achieve a high coefficient of determination (R² of 0.712 on in-house data) for yield prediction [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ML-driven chemistry relies on both computational and experimental resources. The following table lists key components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ML-Driven Chemistry

| Category | Item | Specification/Example | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Resources | ML Optimization Framework | Minerva [3] | Manages Bayesian optimization loop for reaction screening. |

| Graph-Based Prediction Model | GraphRXN [7] | Featurizes molecules and predicts reaction outcomes from structures. | |

| Retrosynthesis Prediction Model | ElemwiseRetro [5] | Recommends precursor sets and synthesis routes for inorganic materials. | |

| Data Resources | Chemical Reaction Database | Open Reaction Database (ORD) [4] | Provides open-access, standardized reaction data for training global models. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Data | Buchwald-Hartwig, Suzuki coupling datasets [4] | Provides high-quality, consistent data for training local predictive models. | |

| Experimental Resources | HTE Robotic Platform | Automated liquid/liquid handling systems | Enables highly parallel execution of reactions (e.g., in 96-well plates) for rapid data generation [3]. |

| Analysis Instrumentation | UPLC/MS, GC/MS | Provides rapid and quantitative analysis of reaction outcomes (yield, selectivity) for data collection [3]. | |

| Chemical Reagents | Non-Precious Metal Catalysts | Nickel-based catalysts [3] | Earth-abundant alternative to precious metals for cross-coupling reactions. |

| Precursor Library | Commercial inorganic precursors (e.g., carbonates, oxides) [5] | A finite set of building blocks for predicting and executing inorganic solid-state synthesis. |

The discovery and optimization of inorganic materials and reactions are pivotal for advancements in energy storage, electronics, and drug development. Traditional experimental approaches are often limited by high costs, lengthy timelines, and the vastness of the chemical space. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool, accelerating materials research by enabling rapid prediction of properties, stability, and synthesis pathways. This article details the practical application of two key classes of ML algorithms—Random Forest and Graph Neural Networks—within inorganic chemistry research. We provide a structured comparison of their performance, detailed experimental protocols for their implementation, and visual workflows to guide researchers and drug development professionals in leveraging these powerful tools.

Algorithm Comparison and Performance Metrics

The selection of an appropriate machine learning algorithm is crucial and depends on the specific research objective, data type, and available computational resources. The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance of key algorithms as applied in materials science and chemistry.

Table 1: Key Algorithms for Inorganic Materials and Reaction Research

| Algorithm | Primary Application Area | Key Advantage | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Toxicity prediction (pIGC50) for Tetrahymena pyriformis; Chemical characterization of atmospheric organics. | High interpretability; Robust performance on structured, descriptor-based data. | R²: 0.886 (test set for toxicity prediction); Median response factor % error: -2% (for quantification). | [8] [9] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Chemical reaction yield prediction; Large-scale inorganic crystal discovery (GNoME). | Directly operates on molecular graph structure; High expressive power and generalization at scale. | Hit rate for stable crystals: >80% (with structure); MAE for energy: 11 meV atom⁻¹. | [10] [11] |

| Ensemble Model (ECSG) | Predicting thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds. | Mitigates inductive bias by combining multiple knowledge sources; High sample efficiency. | AUC: 0.988; Achieves comparable accuracy with 1/7 of the data required by other models. | [1] |

| Reinforcement Learning (PGN/DQN) | Inverse design of inorganic oxide materials. | Optimizes for multiple objectives simultaneously (e.g., properties & synthesis conditions). | Successfully generates novel, valid compounds with target properties (band gap, formation energy) and low synthesis temperatures. | [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pre-training a GNN for Chemical Reaction Yield Prediction

This protocol is adapted from the MolDescPred method, which addresses the challenge of limited reaction yield data by leveraging pre-training on a large molecular database [10].

- Objective: To improve the accuracy of a Graph Neural Network (GNN) in predicting chemical reaction yields, especially when the available training dataset of reactions is small or lacks diversity.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software: Python environment with deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) and cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., RDKit).

- Molecular Database: A large-scale set of molecular structures (e.g., ZINC database). The example study used a database with ~1.6 million molecules [10].

- Descriptor Calculator: Mordred calculator for generating 1,826 2D molecular descriptors.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Calculate Molecular Descriptors: For every molecule in the large-scale molecular database, compute a high-dimensional vector of 2D molecular descriptors using the Mordred calculator [10].

- Dimensionality Reduction with PCA: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the entire set of calculated molecular descriptors. This reduces the dimensionality (e.g., to a vector of 64 principal component scores) while preserving most of the variance, effectively denoising the data [10].

- Define Pre-text Task and Pre-train GNN: Assign the vector of principal component scores as a pseudo-label to each molecule. Pre-train a GNN model to predict this pseudo-label from the input molecular graph. This step forces the GNN to learn meaningful molecular representations that encapsulate broad chemical information [10].

- Initialize and Fine-tune Prediction Model: For the target task of reaction yield prediction, initialize a prediction model using the pre-trained GNN weights. This model takes the molecular graphs of reactants and products as input. The model is then fine-tuned on the smaller, task-specific dataset of chemical reactions and their experimentally determined yields [10].

GNN Pre-training and Fine-tuning Workflow

Protocol 2: Inverse Materials Design using Reinforcement Learning

This protocol outlines a reinforcement learning (RL) approach for the inverse design of inorganic materials with tailored properties and synthesis conditions [12].

- Objective: To generate novel, chemically valid inorganic material compositions that simultaneously satisfy multiple target objectives, such as specific band gaps, formation energies, and low calcination/sintering temperatures.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software: RL frameworks (e.g., OpenAI Gym, Stable-Baselines3), materials informatics libraries.

- Training Data: A database of inorganic oxides with associated properties (e.g., from the Materials Project) to train predictor models [12].

- DFT Software: Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) for energy validation [11].

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Frame the Problem as an RL Task: Formulate the material generation process as a sequence generation task. A state (s) is the current incomplete material composition, and an action (a) is the addition of an element and its stoichiometric coefficient [12].

- Define the Reward Function: Create a multi-objective reward function (Rt) as a weighted sum (Rt = Σ wi * Ri,t) of rewards from different objectives (e.g., Rbandgap, Rsynthesis_temperature). The reward is calculated using a predictor model that estimates the property of the fully generated material composition [12].

- Train the RL Agent: Employ a deep policy gradient (PGN) or deep Q-network (DQN) algorithm. The agent explores the compositional space by generating sequences (materials) and is rewarded based on how well the final composition meets the target objectives. The policy is updated to maximize the cumulative expected reward [12].

- Validate Generated Compositions: Pass the top-ranked compositions generated by the RL agent to a template-based crystal structure predictor to suggest feasible crystal structures. Subsequently, validate the thermodynamic stability and properties of the most promising candidates using DFT calculations [12].

Reinforcement Learning for Inverse Design

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Mordred Calculator | Open-source software to calculate a comprehensive set of 1,826 2D and 3D molecular descriptors from a molecular structure. | Generating pseudo-labels for GNN pre-training in the MolDescPred protocol [10]. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database | A free online database providing computed properties of known and predicted inorganic crystals, including formation energies and band structures. | Sourcing training data for predictor models in RL-driven materials design and for benchmarking discovery efforts [12] [11]. |

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | A software package for performing first-principles quantum mechanical calculations using density functional theory (DFT). | Providing final validation of the thermodynamic stability and properties of ML-predicted materials [11]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit containing a wide array of molecular descriptor calculations and fingerprinting methods. | Featurizing molecules for use in classical machine learning models like Random Forest [13]. |

| GNoME Models | State-of-the-art Graph Neural Networks trained at scale for predicting crystal stability and properties. | Enabling large-scale, efficient screening of hypothetical inorganic crystals, leading to the discovery of millions of new stable structures [11]. |

The exploration of chemical space, encompassing all possible molecules and materials, is a fundamental challenge in chemistry and materials science. Traditional approaches for discovering new compounds with desired properties have heavily relied on structure-based predictions, which require detailed, often experimentally determined, three-dimensional atomic coordinates. While powerful, these methods are computationally expensive and can be limited by the availability of structural data. A significant paradigm shift is occurring toward composition-based predictions, where machine learning models utilize only the chemical formula and stoichiometry to predict properties and stability. This approach enables the rapid screening of vast compositional spaces, dramatically accelerating the discovery of new materials and optimization of chemical reactions. This Application Note frames this methodological shift within the context of machine learning optimization for inorganic reactions research, providing researchers with the protocols and tools to implement these strategies.

Comparative Analysis: Structure-Based vs. Composition-Based Prediction

The following table summarizes the core differences, advantages, and limitations of structure-based and composition-based prediction methodologies as applied to inorganic materials and reaction research.

Table 1: Comparison of Structure-Based and Composition-Based Prediction Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Prediction | Composition-Based Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input Data | Crystallographic information files (.cif), atomic coordinates, bond graphs [14] [15] | Chemical formula, elemental stoichiometry, elemental properties [1] [14] |

| Information Depth | High; includes spatial atom arrangements, symmetry, and bonding [14] | Lower; primarily stoichiometry and weighted elemental properties [14] |

| Computational Cost | High (for calculation and feature generation) [16] [15] | Low to moderate [1] |

| Throughput | Lower, suitable for later-stage validation and refinement [15] | High, ideal for initial large-scale screening [1] [15] |

| Key Advantage | Can distinguish between polymorphs and allotropes; high accuracy for known structures [17] | Applicable where structure is unknown; massively parallel screening [1] [14] |

| Primary Limitation | Structure must be known or accurately predicted a priori [14] [15] | Cannot differentiate polymorphs; may miss structure-driven properties [17] |

| Example Applications | Predicting synthesizability from crystal graphs [15], load-dependent Vickers hardness with structural descriptors [17] | Thermodynamic stability prediction [1], initial hardness screening [17], pitting resistance prediction [18] |

Featurization Strategies for Composition-Based Machine Learning

The performance of composition-based ML models hinges on the effective transformation of a chemical formula into a numerical feature vector. The following protocol details the use of the open-source Composition Analyzer Featurizer (CAF).

Protocol: Compositional Featurization Using CAF

Application Note: This protocol generates a vector of 133 human-interpretable compositional features from a list of chemical formulae, suitable for training supervised ML models for property prediction [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Python 3.7+

- Required Packages: Composition Analyzer Featurizer (CAF), pandas, numpy

- Input Data: Excel file (

.xlsx) or CSV file (.csv) containing a list of chemical formulae.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Create an Excel file with a single column headed

formula. - Populate the column with chemical formulae, ensuring they are written with standard element symbols (e.g.,

SiO2,NaCl,CaTiO3). - Critical Step: Pre-process formulae to standardize formatting and resolve any inconsistencies or typographical errors.

- Create an Excel file with a single column headed

Environment Setup:

- Install the CAF package via pip (

pip install compos-analyzer-featurizer) or from its source repository. - In a Python script or Jupyter notebook, import the necessary modules:

- Install the CAF package via pip (

Feature Generation:

- Load the input file using

pandas: - Instantiate the CAF featurizer and generate features:

- This step calculates a wide array of features, including but not limited to:

- Stoichiometric attributes: Average atomic number, stoichiometric mean, etc.

- Elemental property statistics: Mean, range, and deviation of atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electron count, etc., weighted by composition [14].

- Electronic structure indicators: Features derived from electron configuration [1].

- Load the input file using

Output and Model Integration:

- The output

feature_dfis a pandas DataFrame where each row corresponds to a formula and each column is a numerical feature. - This DataFrame can be concatenated with the original data and directly used for training machine learning models (e.g., XGBoost, SVM) for regression or classification tasks [14] [17].

- The output

Application in Predicting Thermodynamic Stability and Synthesizability

A major application of composition-based ML is the rapid assessment of a compound's thermodynamic stability and likelihood of successful synthesis, which is crucial for guiding inorganic reactions research.

Application Note: Ensemble Model for Stability Prediction

Background: Predicting thermodynamic stability via decomposition energy (ΔHd) traditionally requires constructing a convex hull using computationally intensive Density Functional Theory (DFT) [1]. Composition-based models offer a rapid and sample-efficient alternative.

Implementation:

- Model Architecture: The ECSG (Electron Configuration with Stacked Generalization) framework employs an ensemble method [1].

- Base Models: It integrates three distinct models to reduce inductive bias:

- ECCNN: A novel Convolutional Neural Network that uses the electron configuration of constituent elements as intrinsic input features [1].

- Magpie: Utilizes statistical features (mean, deviation, range) from a suite of elemental properties (e.g., atomic number, radius, electronegativity) [1] [14].

- Roost: Represents the chemical formula as a graph of elements and uses a graph neural network to model interatomic interactions [1].

- Performance: This ensemble achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) score of 0.988 on stability classification within the JARVIS database and required only one-seventh of the data used by existing models to achieve comparable performance [1].

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the integrated ECSG framework for predicting thermodynamic stability.

Protocol: Synthesizability-Guided Materials Discovery Pipeline

Application Note: This protocol uses a combined compositional and structural synthesizability score to prioritize computationally predicted compounds for experimental synthesis, bridging the gap between theoretical stability and practical synthesizability [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Python environment with necessary ML libraries (PyTorch/TensorFlow, XGBoost).

- Data Sources: Materials Project, GNoME, or Alexandria databases.

- Models: Fine-tuned compositional transformer (

fc) and structural graph neural network (fs) from the synthesizability pipeline [15].

Procedure:

- Candidate Pool Generation:

- Download a pool of computationally predicted crystal structures (e.g., ~4.4 million from GNoME) and their compositions.

Synthesizability Scoring:

- For each candidate, obtain two synthesizability probabilities:

s_c(composition-based) ands_s(structure-based). - Calculate a unified RankAvg score for candidate

iusing Borda fusion:RankAvg(i) = (1/(2N)) * Σ_{m in {c,s}} [1 + Σ_j 1(s_m(j) < s_m(i))]whereNis the total number of candidates [15]. - Critical Step: This rank-average ensemble leverages complementary signals from both composition and structure.

- For each candidate, obtain two synthesizability probabilities:

Candidate Prioritization:

- Filter candidates to retain only those with a high RankAvg score (e.g., >0.95).

- Apply secondary filters (e.g., exclude platinoid elements, toxic compounds, focus on oxides).

Synthesis Planning and Execution:

- Feed prioritized targets into a precursor-suggestion model (e.g., Retro-Rank-In) to generate viable solid-state precursors.

- Use a synthesis condition predictor (e.g., SyntMTE) to recommend calcination temperatures.

- Balance reactions and execute synthesis in a high-throughput laboratory platform.

Validation: This pipeline successfully led to the synthesis of 7 out of 16 characterized target compounds, including one novel structure, demonstrating the practical utility of synthesizability scoring [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table lists essential computational "reagents" — software tools, featurizers, and models — required for implementing composition-based machine learning in inorganic research.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Composition-Based Materials Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Composition-Based Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition Analyzer/Featurizer (CAF) [14] | Featurizer | Generates 133 human-interpretable numerical features from a chemical formula. | Core featurization tool for creating input vectors for ML models without structural data. |

| Magpie [1] [14] | Featurizer / Model | Generates statistical features from elemental properties; can also be a baseline model. | Provides a robust set of composition-based descriptors for property prediction. |

| ECCNN [1] | Model | Predicts properties using electron configuration as fundamental input. | Reduces model bias by using intrinsic atomic features, improving stability prediction. |

| XGBoost [17] [19] | Algorithm | Gradient boosted decision trees for regression and classification. | High-performing, explainable algorithm widely used for training on compositional features (e.g., hardness, oxidation temperature). |

| Matminer [14] | Featurizer | Open-source toolkit for generating materials data features. | Provides access to multiple featurization methods and data from large databases like the Materials Project. |

| Synthesizability Pipeline [15] | Integrated Model | Combines compositional and structural models to rank compounds by likelihood of successful synthesis. | Key for transitioning from virtual screening to experimental synthesis in materials discovery. |

The shift from structure-based to composition-based predictions represents a powerful evolution in the toolkit for inorganic reactions research and materials discovery. By leveraging chemical formulae and advanced featurization strategies, researchers can now navigate vast compositional spaces with unprecedented speed and efficiency. The protocols and applications detailed herein—from featurization with CAF to predicting stability with ensemble models and prioritizing candidates via synthesizability scores—provide a practical roadmap for implementation. As these machine learning methodologies continue to mature, they promise to significantly accelerate the design and optimization of novel inorganic compounds, enabling more efficient and targeted experimental campaigns.

The pursuit of new functional materials is a central driver of innovation across fields ranging from clean energy to information processing. A critical first step in this pursuit is the identification of materials that are thermodynamically stable, as this property is a key indicator of a material's synthesizability and its ability to endure under operational conditions. Traditional experimental approaches to establishing stability are characterized by low throughput and high costs, creating a significant bottleneck in the discovery pipeline.

This Application Note frames the concepts of decomposition energy and the convex hull within the modern context of machine learning (ML)-optimized inorganic materials research. We detail the computational protocols for determining these stability metrics and demonstrate how data-driven models are revolutionizing our ability to predict and discover new stable compounds at an unprecedented scale and efficiency.

Computational Foundations of Thermodynamic Stability

Core Definitions

The thermodynamic stability of a material is quantitatively assessed through its tendency to decompose into other, more stable compounds within its chemical space.

- Decomposition Energy (ΔHd): This is defined as the total energy difference between a given compound and its most stable competing phases in a specific chemical space. A negative ΔHd indicates that the compound is stable and will not decompose spontaneously [1].

- Energy Above the Convex Hull (Ehull): This parameter is a direct measure of a compound's thermodynamic stability. It is calculated as the energy difference between the compound and the linear combination of stable phases on the convex hull that represent its most stable decomposition products. A stable compound exhibits an Ehull of zero, meaning it lies directly on the convex hull. More positive values indicate decreasing stability [20].

The Phase Diagram and Convex Hull

The convex hull is a mathematical construction derived from the phase diagram. It is formed by plotting the formation energies of all known compounds in a given chemical system and finding the set of points for which no other point in the set lies below a line connecting any two of them. Compounds lying on this lower envelope are considered thermodynamically stable, while those above it are metastable or unstable [1] [20].

Diagram: The Convex Hull of a Hypothetical Binary System

This diagram illustrates stable phases residing on the convex hull and an unstable compound above it, showing its decomposition pathway to more stable constituents.

The Machine Learning Revolution in Stability Prediction

The conventional method for determining stability involves constructing phase diagrams using energies from density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which are computationally expensive and limit high-throughput exploration [1]. Machine learning models trained on vast DFT-computed databases now offer a paradigm shift, predicting stability with high accuracy orders of magnitude faster.

Key Machine Learning Frameworks

Several advanced ML architectures have been developed specifically for materials stability prediction.

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Frameworks for Stability Prediction

| Model/Framework | Architecture | Input Features | Key Advantage | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECSG [1] | Ensemble (Stacked Generalization) | Electron Configuration, Atomic Properties, Interatomic Interactions | Mitigates inductive bias from single models; High sample efficiency. | AUC = 0.988 |

| GNoME [11] [21] | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Crystal Structure / Composition | Unprecedented scale and generalization; Discovered millions of stable crystals. | >80% precision (with structure), ~11 meV/atom MAE |

| Perovskite Stability Predictor [20] | Extra Trees Classifier / Kernel Ridge Regression | Elemental Property Statistics | Tailored for complex perovskite oxides with A-/B-site alloying. | Predicts Ehull within DFT error bars |

Protocol: Active Learning for Materials Discovery

The GNoME framework exemplifies a modern, scalable protocol for discovering stable materials, leveraging an active learning loop [11] [21].

Diagram: GNoME Active Learning Workflow

This workflow demonstrates the iterative active learning process that enables efficient discovery of stable materials, dramatically improving model performance and discovery rates over time.

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol: Calculating Decomposition Energy via DFT

This protocol details the process for determining a compound's thermodynamic stability using first-principles calculations [1] [20].

1. Energy Calculation of Target Compound

- Perform a full DFT geometry optimization and energy calculation for the target compound using standardized settings (e.g., as in the Materials Project).

- Software: VASP, CP2K.

- Functional: PBE, PBEsol, or SCAN, often with dispersion corrections (D3).

2. Construct the Relevant Chemical Phase Space

- Identify all known compounds in the chemical system of the target compound (e.g., for La-Sr-Co-Fe-O, include all binaries, ternaries, and quaternaries).

- Obtain their optimized crystal structures and energies from databases (Materials Project, OQMD) or calculate them ab initio.

3. Build the Convex Hull

- Using a tool like the Phase Diagram module in Pymatgen, input the formation energies of all compounds in the chemical system.

- The algorithm will compute the lower convex envelope of these points.

4. Determine Decomposition Energy (Ehull)

- The tool calculates the energy above the hull (Ehull) for the target compound.

- A compound with Ehull = 0 is on the hull and is thermodynamically stable.

- A positive Ehull value represents the decomposition energy (ΔHd) required for the compound to decompose into the most stable phases on the hull.

Protocol: Feature Engineering for Composition-Based ML Models

For composition-based models, transforming a chemical formula into a numerical feature vector is crucial. The following protocol is adapted from successful implementations like Magpie and perovskite predictors [1] [20].

1. Elemental Property Compilation

- For each element in the compound, compile a list of fundamental properties:

- Atomic number, atomic mass, group, period.

- Atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electron count.

- Ionization energy, electron affinity.

- Block (s, p, d, f).

2. Generate Statistical Features

- For a compound with multiple elements, calculate statistical measures for each property across its constituent elements:

- Mean, minimum, maximum, range.

- Standard deviation (or mean absolute deviation).

- Mode (for categorical data like block).

3. Feature Selection (Optional but Recommended)

- Use feature selection algorithms (e.g., Stability Selection, Recursive Feature Elimination) to identify the top ~70-100 features that show the highest correlation with stability [20]. This reduces overfitting and improves model performance.

Case Study: Predicting Perovskite Oxide Stability

This case study applies the stability prediction protocol to the technologically important family of perovskite oxides (ABO₃) [20].

Objective: To rapidly screen the vast composition space of doped perovskite oxides (e.g., La₀.₃₇₅Sr₀.₆₂₅Co₀.₂₅Fe₀.₇₅O₃) for thermodynamic stability.

Methods:

- Dataset: A labeled dataset of 1,929 perovskite oxides with DFT-calculated Ehull values was used.

- Feature Engineering: A set of 791 features was generated from elemental properties using the statistical protocol in Section 4.2. This was refined to the top 70 features via recursive feature elimination.

- Model Training:

- Classification (Stable/Unstable): An Extra Trees Classifier was trained.

- Regression (Predict Ehull value): A Kernel Ridge Regression model was trained.

- Validation: Models achieved predictive accuracy within typical DFT error bars, providing a fast screening tool that reduces the need for costly DFT calculations on unstable candidates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Stability Prediction Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Access / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) | Database | Provides a vast repository of DFT-calculated crystal structures and energies for convex hull construction and model training. | materialsproject.org |

| Pymatgen | Python Library | Core library for materials analysis; includes modules for phase diagram construction and Ehull calculation. | pymatgen.org |

| DeePMD-kit | Software Package | Used to train neural network potentials (NNPs) for molecular dynamics simulations at near-DFT accuracy. | github.com/deepmodeling/deepmd-kit |

| VASP | Software Package | Industry-standard software for performing DFT calculations to determine total energies for convex hulls and generate training data. | vasp.at |

| GNoME Models | AI Model | Pre-trained graph neural network models for high-accuracy stability prediction, enabling large-scale discovery. | [Nature 624, 80–85 (2023)] [11] |

The accurate definition of thermodynamic stability through decomposition energy and the convex hull remains a cornerstone of inorganic materials research. The integration of machine learning has transformed this foundational concept into a dynamic tool for discovery. Frameworks like GNoME and ECSG demonstrate that ML models can achieve remarkable accuracy and generalization, guiding researchers toward promising, stable compounds in a vast compositional space. As these models continue to improve through active learning and larger datasets, they will undoubtedly accelerate the discovery and development of next-generation materials for energy, electronics, and beyond.

Methods in Action: Ensemble Learning and Data-Driven Discovery of Inorganic Materials

The accurate prediction of synthesis outcomes and material properties is a cornerstone of accelerating inorganic materials discovery. Traditional machine learning (ML) models in chemistry often rely on a single hypothesis or a limited domain of knowledge, which can introduce significant inductive biases and limit model generalizability [1]. This is particularly problematic in inorganic synthesis research, where datasets are often sparse, noisy, and imbalanced [22] [23]. Ensemble model frameworks, which strategically combine multiple models grounded in diverse knowledge sources, have emerged as a powerful paradigm to mitigate these biases. By integrating complementary perspectives—from atomic-scale electron configurations to macroscopic elemental properties—these ensembles compensate for the individual shortcomings of constituent models, leading to more robust, accurate, and reliable predictions for guiding experimental research [1].

The Case for Ensemble Frameworks in Inorganic Chemistry

Limitations of Single-Source Knowledge Models

Single-model approaches are often constructed based on specific, pre-defined domain knowledge. While powerful, this can lead to a narrow view of the complex physical and chemical relationships governing inorganic reactions and material stability.

- Inductive Bias: Models built on idealized scenarios or a single type of input feature (e.g., only elemental composition) may have their parameter space bounded in a way that excludes the ground truth, leading to reduced predictive accuracy [1].

- Data Scarcity and Imbalance: Inorganic synthesis data is characterized by a long tail of underrepresented reactions and chemistries. Models trained on such imbalanced data tend to be biased toward majority classes, failing to accurately predict outcomes for novel or rare materials [22] [23].

- Opacity of Black-Box Models: Advanced models like the Molecular Transformer, while achieving high accuracy, can be opaque "black boxes." Without interpretability, it is difficult to discern if a correct prediction is made for the right chemical reasons or due to hidden biases in the training data [24].

The Ensemble Advantage: A Multi-Faceted Learning Approach

Ensemble frameworks address these limitations by amalgamating models rooted in distinct domains of knowledge. This approach, often implemented via stacked generalization, creates a "super learner" that is less susceptible to the biases of any single component [1]. The strength of an ensemble lies in the diversity of its constituents; for example, combining models based on interatomic interactions, statistical atomic properties, and quantum mechanical electron configurations ensures a more holistic representation of the factors governing material behavior [1]. This synergy diminishes individual model biases and enhances overall performance, sample efficiency, and generalizability to unexplored compositional spaces.

Key Ensemble Frameworks and Performance

Recent research has yielded several innovative ensemble frameworks with direct application to inorganic chemistry. The table below summarizes two prominent approaches, their architectures, and their validated performance.

Table 1: Key Ensemble Frameworks for Mitigating Bias in Inorganic Materials Research

| Framework Name | Constituent Models & Knowledge Sources | Ensemble Method | Application & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECSG (Electron Configuration with Stacked Generalization) [1] | 1. ECCNN: Electron configuration (Quantum-scale)2. Roost: Interatomic interactions (Atomistic-scale)3. Magpie: Elemental property statistics (Macroscopic-scale) | Stacked Generalization | Task: Predict thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds.Performance: Achieved an AUC of 0.988 on the JARVIS database. Demonstrated high sample efficiency, requiring only one-seventh of the data to match the performance of existing models. |

| Language Model (LM) Ensemble [23] | Off-the-shelf LMs (GPT-4, Gemini 2.0 Flash, Llama 4 Maverick) with diverse pre-training corpora. | Ensembling of model outputs | Task: Precursor recommendation and condition prediction for solid-state synthesis.Performance: Top-1 precursor accuracy up to 53.8%; Top-5 accuracy of 66.1%. Predicted calcination/sintering temperatures with MAE < 126 °C. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Ensemble Framework

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for developing an ensemble model to predict the thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds, based on the ECSG framework [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Data for Ensemble Modeling

| Item | Function / Description | Example Source / Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Database | Provides curated data for training and validation (e.g., formation energies, stability labels). | Materials Project (MP), Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), JARVIS [1] |

| Feature Sets | Diverse numerical representations of materials to train base models. | Electron configuration matrices, elemental stoichiometry, elemental property statistics (Magpie) [1] |

| Base Model Algorithms | The core set of diverse learning algorithms that form the ensemble. | Graph Neural Networks (e.g., Roost), Convolutional Neural Networks (e.g., ECCNN), Gradient Boosting (e.g., XGBoost) [1] |

| Ensemble Wrapper Library | A software library to facilitate the implementation of stacking. | Scikit-learn (StackingClassifier/Regressor) |

| Interpretation Tool | To diagnose model behavior and validate chemical reasonableness. | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [25] [26] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Source your dataset from a structured database such as the Materials Project. The key label is the decomposition energy ((\Delta H_d)) or a binary stability indicator (stable/unstable) derived from the convex hull [1].

- Preprocess the data: Handle missing values, and ensure a consistent format for all chemical compositions.

Step 2: Feature Engineering and Multi-View Dataset Creation Create three separate datasets for the same set of compounds, each representing a different "view" or knowledge source:

- View A (Electron Configuration): Encode each material's composition as a 2D matrix representing the electron configuration of its constituent elements. This serves as input for the ECCNN model [1].

- View B (Interatomic Interactions): Represent the chemical formula as a graph of elements. Use this representation for the Roost model, which applies a graph neural network with an attention mechanism to capture interatomic relationships [1].

- View C (Elemental Statistics): Calculate a set of statistical features (mean, range, mode, etc.) from a list of elemental properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity, valence) for the composition. This is the input for the Magpie model [1].

Step 3: Base-Level Model Training

- Split the full dataset into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. Using the training set, independently train the three base models:

- Train ECCNN on the electron configuration matrices (View A).

- Train Roost on the graph representations (View B).

- Train Magpie (using an algorithm like XGBoost) on the statistical features (View C) [1].

- Perform hyperparameter tuning for each model via cross-validation on the training set.

Step 4: Generating Meta-Features via Stacked Generalization

- Use the trained base models to make predictions on a hold-out portion of the training set (e.g., via 5-fold cross-validation). This prevents target leakage.

- The predicted probabilities (for classification) or values (for regression) from the three base models are then combined to form a new meta-feature dataset.

- The true labels from the hold-out data are retained as the target for this new dataset.

Step 5: Meta-Learner Training

- Train a final model, the meta-learner, on the meta-feature dataset. A logistic regression or a simple linear model is often effective for this purpose [1].

- This meta-learner learns the optimal way to weight and combine the predictions of the three base models.

Step 6: Model Validation and Interpretation

- Validate the final ECSG ensemble model on the held-out test set. Evaluate performance using metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC), accuracy, and F1-score.

- Interpret the model using SHAP analysis. This helps quantify the contribution of each base model to the final prediction and validates that the model's decision-making aligns with chemical intuition [25] [1].

Ensemble Modeling Workflow

Application Note: Diagnosing and Correcting Dataset Bias

Even powerful ensembles can be misled by inherent biases in the training data. It is critical to diagnose and, if possible, correct for these biases.

Protocol for Bias Diagnosis

Objective: To identify if a model is making "Clever Hans" predictions—arriving at the correct answer for the wrong, biased reasons [24].

Procedure:

- Quantitative Interpretation with SHAP: Use SHAP analysis on your trained ensemble model. For a given prediction, SHAP quantifies the contribution of each input feature to the final output [25] [26]. Scrutinize whether the model is relying on chemically reasonable features.

- Data Attribution via Latent Space Similarity: For a given prediction, identify the top-k most similar reactions or compounds in the training set based on the Euclidean distance of their latent space vectors (learned by the model) [24]. This reveals which data points the model considers most relevant.

- Adversarial Validation: Design adversarial examples where the input is subtly altered to contradict the suspected bias. If the model's prediction changes incorrectly, it confirms reliance on the biased feature [24].

Example from Organic Synthesis: The Molecular Transformer achieved high accuracy in predicting Friedel-Crafts acylation reactions. However, interpretation techniques revealed the model was incorrectly using the presence of a Lewis acid catalyst (AlCl₃) as a shortcut to predict the product, rather than learning the underlying electronic effects of the aromatic substrate. When presented with an adversarial example without the catalyst, the model failed, confirming the bias [24].

Bias Correction via Data Debiasin,g

- Solution: If a significant bias is identified (e.g., scaffold bias where certain molecular frameworks are overrepresented), create a new train/test split that ensures no overly similar structures are present in both sets.

- Outcome: This provides a more realistic assessment of model performance and forces it to learn the underlying chemistry rather than memorizing superficial patterns [24]. Retraining the ensemble on this debiased dataset, potentially augmented with synthetic data from language models [23], enhances its generalizability and real-world utility.

Ensemble model frameworks represent a significant leap forward for machine learning in inorganic reactions research. By systematically integrating diverse knowledge sources—from quantum-level electron configurations to data-mined synthesis precedents—these frameworks effectively mitigate the inductive biases that plague single-model approaches. The implemented protocols for ensemble construction and bias diagnosis provide researchers with a robust toolkit for developing more reliable predictive models. As the field progresses, the combination of ensemble methods with interpretability tools and bias-correction strategies will be indispensable for unlocking new, high-performance materials and streamlining their synthesis.

The discovery and optimization of inorganic materials are pivotal for advancements in energy storage, catalysis, and electronics. Traditional experimental approaches and first-principles calculations, while accurate, are often resource-intensive and slow, creating a bottleneck in materials innovation. Machine learning (ML) presents a transformative alternative by enabling rapid prediction of material properties, such as thermodynamic stability, directly from compositional information. A critical challenge in this domain is feature engineering—the process of representing a material's chemical formula as a numerical vector that a model can learn from. The choice of feature representation significantly influences model performance, sample efficiency, and generalizability. This note details three advanced feature engineering methodologies—Electron Configuration, Magpie, and Roost—framed within the context of optimizing ML workflows for inorganic reactions research.

Feature Engineering Approaches: Core Concepts and Protocols

The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of three distinct paradigms for feature engineering in inorganic materials informatics.

Electron Configuration-Based Feature Engineering

Core Concept: This approach leverages the fundamental electron configuration (EC) of atoms as a primary input for model development. The electron configuration delineates the distribution of electrons within an atom's energy levels, providing an intrinsic property that is directly correlated with an element's chemical behavior and reactivity. Using EC aims to minimize inductive biases introduced by hand-crafted features, providing a more foundational representation of the atom [1].

Protocol: Implementing the ECCNN Model

The Electron Configuration Convolutional Neural Network (ECCNN) is a specific implementation that uses ECs as its input [1].

Input Representation:

- Encoding: The electron configuration of a material is encoded into a 2D matrix with dimensions of 118 (elements) × 168 × 8. The specific methodology for this encoding is detailed in the base-level models section of the source material [1].

- Rationale: This structured format allows the model to process the electronic structure information in a spatially coherent manner, suitable for convolutional operations.

Model Architecture:

- Convolutional Layers: The input matrix is passed through two consecutive convolutional operations. Each convolution uses 64 filters with a kernel size of 5×5, designed to extract local patterns from the electron configuration data.

- Batch Normalization and Pooling: The output of the second convolutional layer undergoes Batch Normalization (BN) to stabilize and accelerate training. This is followed by a 2×2 max pooling operation to reduce dimensionality and introduce translational invariance.

- Classification/Regression: The pooled features are flattened into a one-dimensional vector and passed through a series of fully connected (dense) layers to produce the final prediction (e.g., thermodynamic stability) [1].

Magpie: Hand-Engineered Statistical Descriptors

Core Concept: The Magpie (Materials Agnostic Platform for Informatics and Exploration) system constructs feature vectors based on statistical summaries of elemental properties. It is a classic example of a hand-engineered, domain-knowledge-driven descriptor generation framework [1].

Protocol: Constructing a Magpie Descriptor

Elemental Property Selection: For each element present in a material's composition, a suite of fundamental atomic properties is gathered. These typically include:

Statistical Summarization: For each of the selected properties, six statistical measures are calculated across all elements in the compound, weighted by their stoichiometric fractions:

- Mean

- Mean absolute deviation

- Range

- Minimum

- Maximum

- Mode [1].

Feature Vector Formation: The calculated statistics for all properties are concatenated into a single, fixed-length feature vector that represents the material composition.

Model Training: This feature vector is typically used as input for traditional machine learning models. The original Magpie implementation utilizes Gradient-Boosted Regression Trees (XGBoost) for property prediction [1].

Roost: Representation Learning from Stoichiometry

Core Concept: Roost (Representation Learning from Stoichiometry) eschews hand-engineered features in favor of a deep learning model that automatically learns optimal material representations directly from the stoichiometric formula. Its key insight is to reformulate a chemical formula as a dense weighted graph [29].

Protocol: Implementing the Roost Framework

Graph Construction:

- Nodes: Each unique element in the chemical formula is represented as a node in a fully connected graph.

- Node Weights: The fractional abundance (stoichiometric proportion) of each element is assigned as its node weight.

- Initial Node Features: Each element node is initialized with a feature vector. This can be a simple one-hot vector or a more informed embedding, such as Matscholar embeddings, which capture prior knowledge about elements [29] [30].

Message-Passing Neural Network:

- The model employs a message-passing mechanism with a weighted soft-attention mechanism to update node representations.

- Step 1 - Coefficient Calculation: For each pair of elements (i, j), an unnormalized attention coefficient

e_ijis computed using a single-hidden-layer neural network acting on the concatenated feature vectors of the two nodes [30]. - Step 2 - Normalization: The coefficients are normalized using a weighted softmax function, where the weights are the fractional abundances of the elements [30].

- Step 3 - Node Update: Each node's feature vector is updated in a residual manner by aggregating learned perturbations from all other nodes, weighted by the computed attention coefficients. This update is performed multiple times (a hyperparameter

T) and can use multiple attention heads (M) [29] [30].

Global Representation and Prediction:

- After

Tmessage-passing steps, a fixed-length representation for the entire material is created via a second weighted soft-attention-based pooling operation. - This global material representation is fed into a feed-forward neural network to make the final property prediction [29].

- After

Comparative Analysis of Feature Engineering Methods

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance and key characteristics of the three feature engineering methods as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feature Engineering Approaches

| Feature Engineering Method | Core Principle | Representative Model(s) | Reported Performance (AUC/Other) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Configuration | Uses intrinsic electron configuration as model input. | ECCNN, ECSG (Ensemble) | AUC: 0.988 for stability prediction in JARVIS [1]. High sample efficiency (1/7 data for same performance) [1]. | Minimal inductive bias; High physical relevance; Exceptional sample efficiency. | Complex input encoding; Computationally intensive. |

| Magpie | Statistical summarization of elemental properties. | Magpie (XGBoost) | Used as a baseline and in ensemble models [1] [27]. | Interpretable features; Simple to implement; Works with small datasets. | Relies on domain knowledge for property selection; Fixed, hand-crafted features. |

| Roost | Learns representations from stoichiometry via graph neural networks. | Roost, Pre-trained Roost variants | State-of-the-art for structure-agnostic methods; Lower errors, higher sample efficiency than fixed-descriptor models [29]. | No need for feature engineering; Systematically improvable with more data; Captures complex interactions. | Requires larger datasets; "Black-box" nature; Computationally intensive to train. |

Integrated Workflow: The ECSG Ensemble Framework

To mitigate the limitations of individual models and harness their complementary strengths, an ensemble framework based on Stacked Generalization (SG) can be employed. The Electron Configuration models with Stacked Generalization (ECSG) framework integrates models based on distinct knowledge domains [1].

Base-Level Models: Train three distinct models as base learners:

- ECCNN: Provides a perspective based on the internal electronic structure.

- Roost: Provides a perspective based on learned interatomic interactions from stoichiometry.

- Magpie (XGBoost): Provides a perspective based on statistical summaries of elemental properties [1].

Meta-Level Model: The predictions from these three base models are used as input features to train a final meta-learner (a super learner), which produces the final, aggregated prediction [1].

Outcome: This ensemble approach has been shown to achieve a remarkable AUC of 0.988 for predicting thermodynamic stability, demonstrating the synergy of combining diverse feature engineering philosophies [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and integration of these methods within the ECSG ensemble framework.

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for implementing the described feature engineering protocols.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| JARVIS Database | Materials Database | Source of data for training and benchmarking models, particularly for stability prediction [1]. |

| Materials Project (MP) | Materials Database | Provides extensive data on crystal structures and properties for training and validation [27]. |

| OQMD | Materials Database | Another primary source of data for pretraining and finetuning models like Roost [30]. |

| Matbench Benchmark | Benchmarking Suite | A standardized test suite for evaluating and comparing the performance of materials property prediction models [30] [28]. |

| XGBoost | Machine Learning Algorithm | The primary algorithm used to train predictive models based on Magpie feature vectors [1]. |

| Matscholar Embeddings | Elemental Representation | Pre-trained element embeddings often used to initialize node features in the Roost model [30]. |

| CGCNN Embeddings | Structural Representation | Pretrained structural embeddings from a graph neural network, used in multimodal learning to transfer structural knowledge to structure-agnostic models [30]. |

Advanced Applications & Protocol Enhancement

Enhancing Performance with Pretraining Strategies

The performance of structure-agnostic models like Roost can be significantly improved through advanced pretraining strategies, which is particularly beneficial for data-scarce scenarios [30].

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL):

- Protocol: Use the Barlow Twins framework. Create two augmented views of a material's stoichiometry by randomly masking a percentage (e.g., 10%) of the nodes in the formula graph. The Roost encoder is pretrained to make the representations of these two augmented views similar, learning robust, noise-invariant features without labeled data [30].

Fingerprint Learning (FL):

- Protocol: Pretrain the Roost encoder to predict hand-engineered Magpie fingerprints. This forces the model to learn the information encapsulated in the expert-crafted features while retaining the benefits of a learnable framework [30].

Multimodal Learning (MML):

- Protocol: Leverage materials with known crystal structures. Pretrain the Roost encoder to predict the structural embeddings generated by a pretrained structure-based model (e.g., a CGCNN from the Crystal Twins framework). This allows the stoichiometry-based model to implicitly learn representations that contain structural information [30].

Improving Out-of-Distribution Generalization

Generalization to out-of-distribution (OOD) data is a critical challenge. The choice of feature encoding plays a vital role.

- Challenge: Models trained with common one-hot element encodings often perform poorly on compositions or property ranges not seen during training, especially with small datasets [28].

- Recommended Protocol: Use physically-informed encoding instead of one-hot encoding. Incorporating fundamental atomic properties (e.g., group number, period, electronegativity, atomic radius) as node features in models like Roost or ALIGNN has been shown to significantly improve OOD performance by providing a stronger inductive bias grounded in chemistry [28].

The discovery of new inorganic compounds is fundamentally limited by the challenge of predicting their thermodynamic stability. Conventional methods, which rely on density functional theory (DFT) calculations or experimental trials to construct phase diagrams, are characterized by substantial computational expense and time consumption [1]. Machine learning (ML) offers a promising avenue for rapidly and accurately predicting stability, thereby accelerating the exploration of novel materials [1] [31]. However, many existing ML models are constructed based on specific domain knowledge or idealized scenarios, which can introduce significant inductive biases and limit their predictive performance and generalizability [1].

This application note details a case study on the Electron Configuration models with Stacked Generalization (ECSG) framework, an ensemble machine learning approach designed to accurately predict the thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds. The ECSG framework effectively mitigates the limitations of individual models by integrating diverse knowledge domains, demonstrating remarkable efficiency and accuracy in navigating unexplored compositional spaces [1]. Its application is particularly valuable in research and development for fields such as two-dimensional wide bandgap semiconductors and double perovskite oxides, where traditional methods act as a bottleneck for innovation [1].

The ECSG framework is an ensemble method based on the concept of stacked generalization. Its core innovation lies in amalgamating three distinct base models, each rooted in different domains of knowledge—electron configuration, atomic properties, and interatomic interactions. This diversity ensures that the strengths of one model compensate for the weaknesses of others, thereby reducing collective inductive bias and enhancing overall predictive performance [1].

The framework operates on a two-level architecture: a base level and a meta-level. The base-level models make initial predictions based on the chemical composition of a compound. These predictions are then used as input features to train a meta-level model, which produces the final, refined prediction for thermodynamic stability [1].

Composition-Based Model Rationale

The models within the ECSG framework are composition-based, meaning they use only the chemical formula of a compound as input. While structure-based models contain more extensive geometric information, determining precise crystal structures for new, hypothetical materials is often challenging, computationally expensive, or impossible. Composition-based models can significantly advance the efficiency of new materials discovery, as composition information is known a priori and can be readily used to sample vast compositional spaces [1].

Base-Level Models

The performance of the ECSG ensemble depends on the complementary nature of its three constituent models.

Table 1: Summary of Base-Level Models in the ECSG Framework

| Model Name | Underlying Knowledge Domain | Core Algorithm | Key Input Features | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECCNN (Electron Configuration Convolutional Neural Network) | Electron Configuration [1] | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [1] | Electron configuration matrix (118×168×8) [1] | Leverages an intrinsic atomic property; introduces minimal inductive bias [1] |

| Roost | Interatomic Interactions [1] | Graph Neural Network (GNN) with attention mechanism [1] | Chemical formula represented as a graph [1] | Effectively captures critical interactions between atoms in a crystal structure [1] |

| Magpie | Atomic Properties [1] | Gradient-Boosted Regression Trees (XGBoost) [1] | Statistical features (mean, deviation, range, etc.) of elemental properties [1] | Captures broad diversity among materials using a wide range of elemental attributes [1] |

Experimental Protocol

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for implementing the ECSG framework to predict the thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

1. Source the Training Data:

- Primary Source: Acquire a dataset of inorganic compounds with known thermodynamic stability, typically represented by the decomposition energy (ΔH_d). Large, open-source databases such as the Materials Project (MP) or the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) are excellent starting points [1].