Lanthanide Complex Luminescence and Energy Transfer: Fundamental Mechanisms and Emerging Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the intricate photophysical processes and cutting-edge applications of luminescent lanthanide complexes, with a specific focus on energy transfer mechanisms crucial for biomedical innovation.

Lanthanide Complex Luminescence and Energy Transfer: Fundamental Mechanisms and Emerging Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the intricate photophysical processes and cutting-edge applications of luminescent lanthanide complexes, with a specific focus on energy transfer mechanisms crucial for biomedical innovation. We examine foundational principles of antenna effects and sensitization, advanced material design strategies for supramolecular architectures and heteronuclear systems, and optimization approaches for enhancing thermal sensitivity and emission quantum yield. The article critically evaluates performance validation methods and comparative analysis of different lanthanide ions for specific applications, including molecular thermometry, drug delivery, photodynamic therapy, and bioimaging. This resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with both theoretical understanding and practical insights to advance diagnostic and therapeutic technologies through rational lanthanide complex design.

Unraveling the Photophysical Principles of Lanthanide Luminescence

Electronic Structure of Trivalent Lanthanide Ions and 4f-4f Transitions

The trivalent lanthanide ions (Ln³⁺) are a cornerstone of modern photonic and materials science, enabling technologies from vibrant display screens and efficient lighting to sensitive biological probes. Their unique luminescent properties are a direct consequence of their distinctive electronic structure, particularly the behavior of electrons within the 4f orbitals. Unlike transition metals, the 4f orbitals in lanthanides are shielded from the external chemical environment by filled 5s² and 5p⁶ outer orbitals [1]. This shielding results in sharp, atomic-like emission lines that are minimally affected by the host material or solvent, making Ln³⁺ ions exceptionally reliable and tunable luminescent centers [1] [2]. The intraconfigurational 4f-4f transitions responsible for this luminescence are parity-forbidden, leading to long luminescence lifetimes—a critical feature for time-gated bioimaging and optical sensing [1] [3]. This technical guide delves into the fundamental principles governing the electronic structure of Ln³⁺ ions and their 4f-4f transitions, providing a framework for understanding their behavior within the broader context of luminescent lanthanide complexes and energy transfer research.

Electronic Configuration and Spectral Properties

The lanthanide series encompasses the 14 elements following lanthanum (La), in which the 4f orbital is progressively filled, from cerium (Ce, [Xe]4f¹) to lutetium (Lu, [Xe]4f¹⁴). The trivalent state (Ln³⁺) is the most common and technologically relevant, formed by the removal of the two 6s electrons and one 4f (or, in the case of Ce, one 5d) electron.

The 4fⁿ Configuration and Spin-Orbit Coupling

The core electronic structure of an Ln³⁺ ion is defined by its 4fⁿ configuration, where n ranges from 1 (Ce³⁺) to 13 (Yb³⁺). The energy levels, or term states, arising from this configuration are described by the Russell-Saunders coupling scheme, yielding spectroscopic terms of the form ²ˢ⁺¹Lⱼ. The spin-orbit coupling is exceptionally large for the 4f electrons, causing a significant splitting of these term states into their J-multiplets. The energy separation between different J-multiplets can be several thousands of cm⁻¹, which is substantially larger than the splitting induced by the crystal field of the host material [1] [2]. This results in the characteristic, sharp emission lines of Ln³⁺ ions.

Table 1: Ground State Terms and Key Emission Wavelengths for Trivalent Lanthanide Ions

| Ln³⁺ Ion | 4fⁿ Configuration | Ground State Term (²ˢ⁺¹Lⱼ) | Prominent Emission Transition | Typical Emission Wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce³⁺ | 4f¹ | ²F₅/₂ | 5d → 4f (broad band) | UV-Blue (varies widely) |

| Pr³⁺ | 4f² | ³H₄ | ³P₀ → ³H₄ | ~490 (Blue) |

| Nd³⁺ | 4f³ | ⁴I₉/₂ | ⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₁/₂ | ~1060 (NIR) |

| Eu³⁺ | 4f⁶ | ⁷F₀ | ⁵D₀ → ⁷F₂ | ~612 (Red) |

| Tb³⁺ | 4f⁸ | ⁷F₆ | ⁵D₄ → ⁷F₅ | ~545 (Green) |

| Er³⁺ | 4f¹¹ | ⁴I₁₅/₂ | ⁴I₁₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₅/₂ | ~1540 (NIR) |

| Yb³⁺ | 4f¹³ | ²F₇/₂ | ²F₅/₂ → ²F₇/₂ | ~980 (NIR) |

Shielding and Narrow Emission Lines

The shielding provided by the outer 5s and 5p orbitals is the most critical factor defining the optical properties of Ln³⁺ ions. This shielding renders the 4f electrons largely insensitive to the ligand field, or crystal field, of the surrounding environment [1]. Consequently, the 4f-4f emission spectra consist of narrow, line-like bands. The emission wavelengths are thus largely "ion-specific" and can be predicted from Dieke's diagram, which maps the energy levels of Ln³⁺ ions in a standard host [1]. For example, Eu³⁺ consistently produces red emission around 612 nm due to the ⁵D₀→⁷F₂ transition, while Tb³⁺ produces characteristic green emission at ~545 nm from the ⁵D₄→⁷F₅ transition [1].

Theory of 4f-4f Transitions

The electronic transitions within the 4fⁿ configuration are governed by specific selection rules that have profound implications for the luminescence efficiency of Ln³⁺ ions.

Selection Rules and Transition Probabilities

The primary selection rules for electronic transitions are the Laporte rule (or parity selection rule), which states that transitions between orbitals of the same parity (e.g., f-f) are forbidden, and the selection rule for total angular momentum, ΔJ = 0, ±1 (but J = 0 → 0 is forbidden). Since 4f orbitals are of odd parity, all 4f-4f transitions are Laporte-forbidden. This results in very low absorption coefficients for Ln³⁺ ions, as they cannot directly absorb light efficiently to populate their excited states [1] [2]. In practice, these transitions become partially allowed due to two key mechanisms:

- Judd-Ofelt Theory: This foundational theory posits that the crystal field of the host environment mixes odd-parity character (e.g., from 5d orbitals) into the 4f states, relaxing the Laporte rule and making the transitions partially allowed [4]. The theory parameterizes the strength of this forced electric dipole transition using three intensity parameters (Ω₂, Ω₄, Ω₆), which are dependent on the host matrix and ligand field.

- Magnetic Dipole Transitions: Certain transitions that obey the magnetic dipole selection rules (ΔJ = 0, ±1, but J = 0 → 0 is forbidden) are also allowed. The ⁵D₀→⁷F₁ transition of Eu³⁺ is a classic example of a magnetic dipole transition, and its intensity is largely independent of the chemical environment [2].

Modified Judd-Ofelt Theory

Recent advancements have extended the standard Judd-Ofelt theory to provide a more physical and quantitative insight into all transitions within the 4fⁿ configuration. In this modified model, the properties of the Ln³⁺ dopant are calculated using established atomic-structure techniques, while the crystal-field potential's influence is described by three adjustable parameters [4]. This approach has been successfully applied to Eu³⁺, an ion known to challenge the standard Judd-Ofelt theory, and has enabled the quantitative reproduction of experimental absorption oscillator strengths [4].

Energy Transfer and Sensitization: The Antenna Effect

The inherent weakness of direct 4f-4f excitation necessitates a strategy for efficiently populating the excited states of Ln³⁺ ions. This is universally achieved through the antenna effect (or sensitization), a multi-step energy transfer process from an organic ligand to the metal ion [1] [3].

The Sensitization Pathway

The mechanism of the antenna effect can be visualized and described in a series of distinct steps, as outlined below.

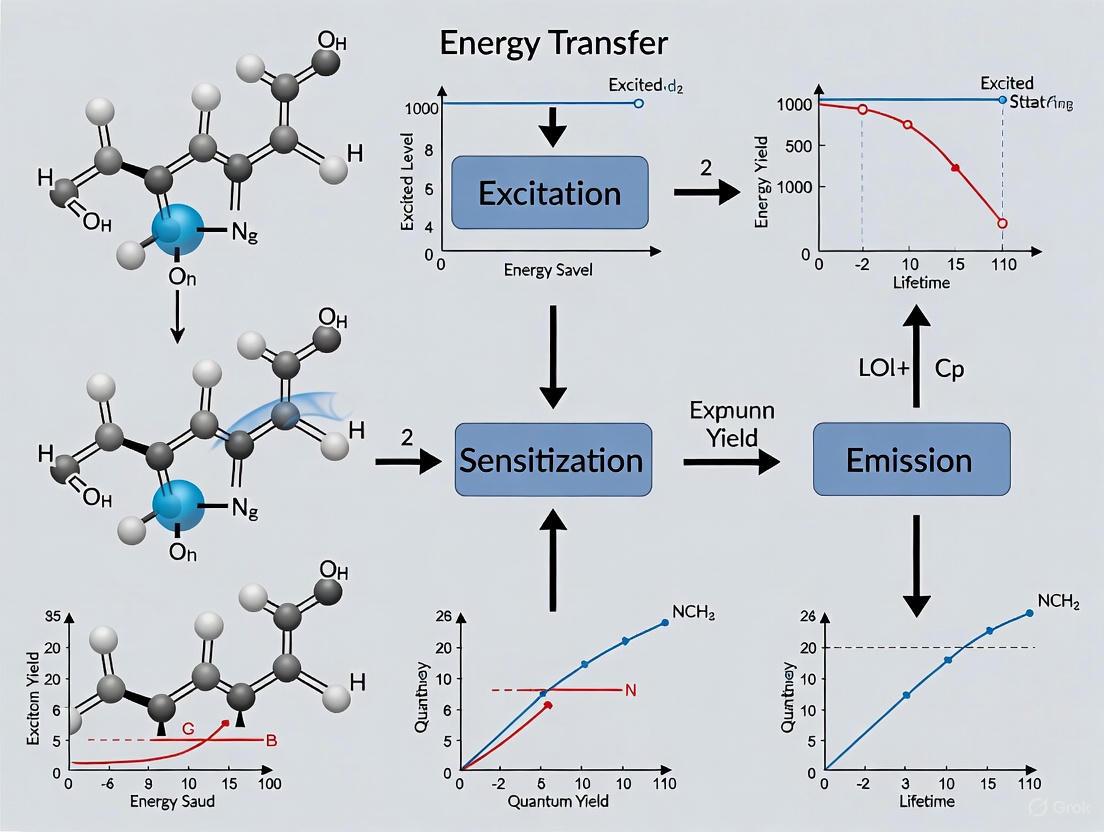

Diagram 1: Antenna effect energy transfer pathway.

- Excitation: An organic ligand (the "antenna") absorbs excitation energy, typically ultraviolet light, promoting it from its singlet ground state (S₀) to an excited singlet state (S₁).

- Intersystem Crossing (ISC): The excited ligand undergoes intersystem crossing from its singlet state (S₁) to a metastable triplet state (T₁). This process is efficient in ligands containing heavy atoms or with spin-orbit coupling promoters.

- Energy Transfer (ET): The energy from the ligand's triplet state (T₁) is non-radiatively transferred to the resonant energy level of the Ln³⁺ ion, populating its emitting state (e.g., ⁵D₄ for Tb³⁺ or ⁵D₀ for Eu³⁺). For efficient transfer, the triplet energy level of the ligand must be higher than the accepting energy level of the Ln³⁺ ion [3] [5].

- Luminescence: The Ln³⁺ ion relaxes radiatively to its lower-lying 4f levels, producing its characteristic, sharp-line luminescence.

Quenching and Back-Transfer

A critical consideration in sensitization is the energy gap (ΔE) between the ligand's T₁ state and the Ln³⁺ accepting state. If this gap is too small (< ~2000 cm⁻¹ for Tb³⁺ and Eu³⁺), thermally activated energy back-transfer from the Ln³⁺ ion to the ligand triplet state can occur, leading to luminescence quenching [5]. This phenomenon is highly temperature-dependent and is actively exploited in the design of luminescent molecular thermometers [5]. Recent research demonstrates that introducing an additional energy escape pathway from the ligand triplet state, for example, to a second lanthanide ion like Nd³⁺, can shorten the triplet state's lifetime and significantly enhance the temperature sensitivity of the Tb³⁺ emission [5].

Table 2: Key Energy Transfers and their Roles in Ln³⁺ Luminescence

| Energy Transfer Process | Description | Condition for Efficiency | Application/Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-to-Ln³⁺ (Sensitization) | Energy transfer from ligand T₁ state to Ln³⁺ excited state. | T₁ (Ligand) > Ln* (Ln³⁺) | Primary mechanism for enhancing Ln³⁺ luminescence (Antenna Effect). |

| Back-Transfer (Quenching) | Thermal energy-driven transfer from Ln³⁺ excited state back to ligand T₁ state. | Small ΔE(T₁ - Ln*) | Luminescence quenching; basis for lifetime-based thermometry [5]. |

| Ln³⁺-to-Ln³⁺ | Energy migration between identical or different Ln³⁺ ions. | Spectral overlap of donor emission & acceptor absorption. | Concentration quenching or sensitization in co-doped systems. |

| Energy Escape Pathway | Transfer from ligand T₁ state to a secondary acceptor. | T₁ (Ligand) ≈ Acceptor Level | Shortens T₁ lifetime, enhances thermal sensitivity [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol: Measuring Absolute Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

The PLQY is a critical metric defining the efficiency of a luminescent material.

- Instrumentation: Use an integrating sphere coupled to a calibrated spectrophotometer with a known excitation source.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solid sample as a finely ground pellet or a solution in a spectroscopically suitable solvent. Ensure optical density at the excitation wavelength is below 0.1 to minimize inner-filter effects.

- Measurement: a. Place the sample inside the integrating sphere. b. Excite the sample and record the emission spectrum (Esample(λ)). c. Measure the spectrum of the excitation beam scattered by a diffuse reflector (e.g., Spectralon) placed in the sample position (Eref(λ)).

- Calculation: PLQY (Φ) is calculated using the equation: Φ = [∫Esample(λ)dλ - ∫Eexcitation(λ)dλ] / [∫Lref(λ)dλ - ∫Lsample(λ)dλ] where L refers to the light spectrum measured without the sample for excitation correction [6].

Protocol: Determining Emission Lifetimes

The emission lifetime (τ) is a key parameter for applications in time-gated detection and thermometry.

- Instrumentation: Use a time-resolved fluorescence spectrometer equipped with a pulsed excitation source (e.g., Nd:YAG laser, flashlamp) and a fast detector (photomultiplier tube or avalanche photodiode).

- Measurement: Excite the sample with a short pulse of light and record the intensity decay profile, I(t), at the specific emission wavelength of the Ln³⁺ ion.

- Analysis: For a simple system, the decay is often single-exponential: I(t) = I₀ exp(-t/τ). Fit the decay curve to determine the lifetime τ. For more complex systems, a multi-exponential or stretched-exponential fit may be required [5]. For temperature sensing, this lifetime measurement is repeated at different temperatures to calibrate the thermometer [5].

Protocol: Resolving Hydration State via Lifetime Measurements

The number of water molecules (q) directly coordinated to a Ln³⁺ ion in aqueous solution is a crucial parameter, as water molecules efficiently quench luminescence via O-H vibrators.

- Measurement: Determine the emission lifetime (τ) of the Ln³⁺ ion (e.g., Eu³⁺ or Tb³⁺) in H₂O and in D₂O.

- Calculation for Eu³⁺: The number of coordinated water molecules (q) can be estimated using the empirical formula [3]: q = A (1/τH₂O - 1/τD₂O - B) where A and B are experimentally determined constants specific to Eu³⁺ (typically A = 1.05 ms and B = 0.31 ms⁻¹ for the ⁵D₀ state).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Ln³⁺ Luminescence Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hexafluoroacetylacetonate (hfa) | Anionic β-diketonate ligand; serves as a "sensitizing" antenna. | Strong electron-withdrawing CF₃ groups lower ligand triplet energy, enhance luminescence in Tb³⁺/Eu³⁺ complexes, and improve volatility/thermal stability [5]. |

| Triphenylene-derived ligands (e.g., dptp) | Neutral bridging ligand; can act as a secondary antenna. | Extended π-conjugation can tune triplet energy; capable of forming dinuclear or polynuclear complexes, enabling inter-metal energy transfer studies [5]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O, d⁶-DMSO) | Solvent for photophysical studies. | Replacing O-H oscillators with O-D reduces vibrational quenching, allowing measurement of intrinsic radiative lifetime and calculation of hydration number (q) [3]. |

| Ln(HMDS)₃ / LnCl₃(THF)ₓ | Precursors for synthesizing organometallic Ln complexes. | Ln(HMDS)₃ (lanthanide hexamethyldisilazide) is a non-halogenated, highly reactive precursor useful for metathesis reactions [6]. |

| Integrating Sphere | Essential accessory for spectrophotometers. | Required for the accurate measurement of absolute photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) of solid-state or solution samples. |

| Cryostat (e.g., He-closed cycle) | Temperature control system. | Enables temperature-dependent lifetime and intensity studies from cryogenic to room temperatures, crucial for studying thermal quenching and developing thermometers [5]. |

Applications in Energy Transfer Research

The fundamental principles of Ln³⁺ electronic structure and 4f-4f transitions directly enable advanced applications in energy transfer research. One cutting-edge example is the development of luminescent molecular thermometers. As detailed in recent work, a dinuclear Tb(III)-Nd(III) complex was designed where temperature-dependent energy transfer from the Tb(III) emitting state to the ligand triplet state serves as the sensing mechanism [5]. The innovation was the introduction of an energy "escape pathway" from the ligand triplet to the Nd(III) ion, which shortened the triplet state's lifetime and resulted in a record-high temperature sensitivity of 4.4% K⁻¹ for emission lifetime-based thermometers [5]. This exemplifies how a deep understanding of energy transfer pathways between 4f ions and their ligands can lead to highly functional materials.

The experimental workflow for developing and characterizing such a system is complex and involves multiple, interconnected steps, as visualized below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for developing Ln³⁺ functional materials.

The electronic structure of trivalent lanthanide ions, characterized by the shielded and spin-orbit coupled 4fⁿ configuration, is the fundamental origin of their unique and technologically invaluable luminescence. The parity-forbidden nature of 4f-4f transitions, while leading to weak direct absorption, results in long-lived excited states that can be efficiently populated via the antenna effect in complexed ions. Ongoing research continues to refine theoretical models like Judd-Ofelt theory and to exploit the nuances of energy transfer and quenching mechanisms. This deep understanding enables the rational design of sophisticated luminescent materials, from self-assembled supramolecular structures for sensing and imaging to advanced molecular thermometers with exceptional sensitivity. The study of 4f-4f transitions remains a vibrant and critical field, driving innovation at the intersection of molecular design, photophysics, and materials science.

The antenna effect, a cornerstone of photophysical processes in lanthanide coordination chemistry, describes the efficient light-harvesting mechanism where organic ligands absorb light and subsequently transfer energy to centrally coordinated lanthanide ions (Ln³⁺), sensitizing their characteristic luminescence [7]. This process overcomes the fundamental limitation of direct Ln³⁺ excitation—the Laporte-forbidden nature of 4f-4f transitions resulting in low molar absorption coefficients and weak emission [7]. By coordinating organic "antenna" ligands, lanthanide complexes (LLCs) synergistically combine the structural stability and tunability of organic chemistry with the exceptional optical properties of lanthanides, including long luminescence lifetimes, large Stokes shifts, narrow emission bands, and high photostability [7]. These properties make antenna effect-modulated LLCs invaluable across diverse fields from biological sensing and medical diagnostics to solar energy conversion and light-emitting devices [8] [7]. This review comprehensively examines the fundamental mechanisms, ligand design principles, experimental methodologies, and applications of ligand-to-metal energy transfer in lanthanide complexes, framed within contemporary research advances in lanthanide luminescence.

Theoretical Foundations of the Antenna Effect

The antenna effect operates through a multi-step photophysical process that efficiently converts the absorbed light energy into lanthanide-centered emission. The fundamental mechanism can be conceptualized as a coordinated energy transfer cascade with distinct stages, illustrated in the following diagram:

Diagram: Sequential steps in the antenna effect energy transfer mechanism from ligand excitation to lanthanide emission.

The energy transfer process begins with photon absorption by the antenna ligand, promoting it from the ground state (S₀) to an excited singlet state (S₁) [7]. This is followed by intersystem crossing (ISC), a non-radiative process where the ligand transitions from the singlet state (S₁) to a triplet state (T₁), facilitated by spin-orbit coupling enhanced by the heavy lanthanide atom [9]. The critical energy transfer (ET) step then occurs, where energy is transferred from the ligand's triplet state to the resonant energy level of the lanthanide ion [7]. Finally, the excited lanthanide ion undergoes radiative decay, emitting characteristically sharp-line luminescence as it returns to the ground state [7].

For efficient energy transfer to occur, the triplet state energy level of the antenna ligand must be carefully matched to the accepting energy level of the lanthanide ion. The energy gap must be sufficiently large to minimize back-energy transfer yet small enough to maintain favorable energy transfer kinetics [7]. This precise energy matching requirement makes ligand design a critical factor in determining the overall luminescence efficiency of lanthanide complexes.

Ligand Design and Classification

Antenna ligands constitute the fundamental architectural components that determine the efficiency of the ligand-to-metal energy transfer process. Based on their chemical structures and functional properties, antenna ligands can be categorized into several distinct classes, each offering unique advantages for specific applications:

Table: Classification of Antenna Ligands for Lanthanide Complexes

| Ligand Class | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Diketone Ligands | High molar absorptivity, efficient energy transfer, form stable complexes | Thenoyltrifluoroacetone (TTA), Dibenzoylmethane (DBM) | Highly luminescent materials, sensors |

| Aromatic Ligands | Rigid structures, conjugate π-systems, tunable energy levels | 2,2'-Bipyridine (bipy), 1,10-Phenanthroline (phen) | Molecular scaffolds, co-sensitizers |

| Macrocyclic Ligands | Pre-organized cavities, high stability constants, selectivity | Cyclen derivatives, DOTA, DO3A | Biomedical applications, MRI contrast agents |

| Biomolecular Ligands | Biocompatibility, specific recognition properties | Nucleotides, amino acids, proteins | Biosensing, bioimaging |

| Organic Dye Ligands | Strong light absorption, broad excitation spectra | Coumarin derivatives, cyanines | Extended spectral coverage, multiplexing |

| Nanomaterial Ligands | Large surface area, unique electronic properties | Carbon dots, graphene quantum dots | Enhanced sensitivity, composite materials |

The selection of appropriate antenna ligands depends critically on the specific lanthanide ion and application requirements. For instance, terbium (Tb³⁺) and europium (Eu³⁺) complexes typically require ligands with triplet state energies above 20,000 cm⁻¹ and 17,500 cm⁻¹, respectively, for optimal energy transfer [7]. Recent research has increasingly focused on hybrid ligand systems that combine multiple antenna types to achieve synergistic effects, such as extended spectral coverage or enhanced luminescence efficiency through co-sensitization strategies [7].

Experimental Methodologies and Monitoring Techniques

In Situ Monitoring Approaches

Understanding the dynamic processes of complex formation and energy transfer requires sophisticated in situ monitoring techniques that can track structural evolution and photophysical changes simultaneously. Recent advances have enabled researchers to correlate structural transformations with the emergence of luminescent properties during synthesis:

Diagram: Integrated in situ monitoring of lanthanide complex synthesis using simultaneous XRD and luminescence spectroscopy.

A pioneering approach combines in situ luminescence spectroscopy with synchrotron-based X-ray diffraction (XRD) to monitor the synthesis of luminescent lanthanide complexes such as [Tb(bipy)₂(NO₃)₃] [8]. This integrated methodology has revealed intricate crystallization pathways involving reaction intermediates whose formation depends on synthesis parameters like ligand-to-metal molar ratios and addition rates [8]. The ligand-to-metal energy transfer, monitored through Tb³⁺ emission intensity at 545 nm, serves as a sensitive probe for tracking complex formation kinetics in real-time [8].

Structural Characterization Techniques

Advanced structural characterization methods are essential for correlating photophysical properties with molecular architecture:

Serial X-ray Crystallography: This emerging technique utilizes bright, tightly focused X-ray sources to collect thousands of snapshot diffraction patterns from multiple microcrystals, overcoming limitations associated with beam damage and small crystal sizes [8]. The method has been successfully applied to solve structures of radiation-sensitive lanthanide complexes, including [Tb(bipy)₂(NO₃)₃], with accuracy comparable to classical single-crystal XRD [8].

Computational Structure Prediction: Tools like Architector enable high-throughput in silico generation of three-dimensional structures for lanthanide complexes from two-dimensional molecular graphs [10]. This computational approach leverages metal-center symmetry analysis, distance geometry, and fragment assembly to predict coordination structures, achieving quantitative agreement with experimentally determined configurations across thousands of complexes [10].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Computational protocols combining classical molecular dynamics and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations explicitly model lanthanide coordination structures in solution, accounting for ligand flexibility, explicit solvent molecules, anions, and chemical reactions [11]. These methods provide atomic-resolution insights into dynamic coordination environments that often differ from solid-state structures [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental investigation of antenna effects in lanthanide complexes requires specialized materials and instrumentation. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in this field:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Instrumentation for Investigating Antenna Effects

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lanthanide Salts | Tb(NO₃)₃·5H₂O, EuCl₃·6H₂O | Metal ion precursors for complex synthesis |

| Organic Ligands | 2,2'-bipyridine, 1,10-phenanthroline, β-diketones | Antenna chromophores for energy absorption and transfer |

| Structural Characterization | Synchrotron XRD, Serial crystallography | Determining three-dimensional molecular structures |

| Photophysical Analysis | Fluorolog spectrometers, Portable CCD spectrometers | Monitoring luminescence properties and energy transfer efficiency |

| Computational Tools | Architector, molSimplify, DENOPTIM | Predicting structures and properties of lanthanide complexes |

| Synthesis Control | Automated synthesis workstations (e.g., EasyMax) | Precise control over reaction parameters (temperature, addition rates) |

The integration of these research tools enables comprehensive investigation of the antenna effect, from initial complex synthesis and structural characterization to photophysical analysis and computational modeling. Automated synthesis platforms allow simultaneous multiparameter monitoring of solution conditions including pH, ionic conductivity, and luminescence during complex formation [8]. Computational structure generation tools like Architector significantly accelerate research by predicting feasible complex structures and their properties before synthetic efforts [10].

Applications in Sensing and Technology

The unique photophysical properties enabled by the antenna effect have led to diverse applications of luminescent lanthanide complexes, particularly in the realm of biological sensing and detection:

Biosensing Platforms: Antenna effect-modulated LLCs serve as transducers in fluorescence (FL) and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) sensors for detecting proteins, enzymes, nucleic acids, antibiotics, metal ions, and anions [7]. Their long luminescence lifetimes enable time-gated detection methods that eliminate short-lived background fluorescence, significantly improving signal-to-noise ratios in complex biological samples [7].

Medical Diagnostics: Lanthanide complexes functionalized with specific recognition elements enable sensitive detection of disease biomarkers in body fluids, offering potential for early disease diagnosis [7]. The sharp emission bands and large Stokes shifts facilitate multiplexed detection schemes where multiple analytes can be monitored simultaneously using different lanthanide reporters [7].

Environmental Monitoring: LLC-based sensors detect hazardous substances including heavy metal ions, pesticides, and organic pollutants in environmental samples [7]. The antenna effect can be modulated by analyte binding, creating highly sensitive detection platforms that combine the recognition properties of specialized ligands with the exceptional optical properties of lanthanides [7].

The antenna effect represents a fundamental photophysical process that has been successfully harnessed to overcome intrinsic limitations in lanthanide luminescence. Through rational ligand design and sophisticated monitoring techniques, researchers have developed increasingly efficient luminescent lanthanide complexes with tailored photophysical properties. The integration of advanced structural characterization methods, particularly in situ monitoring combining synchrotron XRD with luminescence spectroscopy, provides unprecedented insights into the dynamic processes of complex formation and energy transfer.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: (1) developing novel antenna ligands with improved energy matching and higher molar absorptivity; (2) creating multi-chromophoric systems for broader spectral coverage and enhanced efficiency; (3) advancing in situ and operando characterization techniques to unravel dynamic processes in real time; and (4) integrating computational prediction with experimental synthesis to accelerate materials discovery. As these developments progress, antenna effect-modulated luminescent lanthanide complexes will continue to enable new technologies in sensing, imaging, and energy conversion, bridging fundamental photophysical principles with practical applications across scientific disciplines.

Radiative and Non-Radiative Transition Pathways in Ln(III) Complexes

Lanthanide (Ln(III)) complexes exhibit unique photophysical properties that make them invaluable across scientific and industrial domains, from biomedical imaging and sensing to security inks and light-emitting devices. Their luminescence originates from electronic transitions within the partially filled 4f shell, which is effectively shielded by outer 5s² and 5p⁶ orbitals. This shielding results in characteristic sharp, line-like emission bands that are largely insensitive to the surrounding environment [12] [1]. The trivalent lanthanide ions possess a wealth of electronic energy levels, enabling emissions that span the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared spectral regions [1].

A fundamental challenge, however, is that these 4f-4f transitions are parity-forbidden, leading to very low molar absorption coefficients. This limitation is overcome through the antenna effect, where organic ligands absorbing light efficiently transfer the captured energy to the lanthanide ion, thereby populating its excited states and sensitizing its luminescence [3] [13] [12]. The overall luminescence efficiency of a Ln(III) complex is governed by the balance between radiative transition pathways, which produce light, and non-radiative transition pathways, which dissipate excitation energy as heat. Understanding and controlling these competing pathways is a central focus in the design of high-performance luminescent lanthanide materials [3] [12].

Radiative Transition Pathways

Radiative transitions in Ln(III) ions result in the emission of photons and are characterized by long luminescence lifetimes, typically on the order of microseconds to milliseconds [1]. These transitions occur between discrete 4f electronic energy levels.

Characteristics of f-f Radiative Transitions

The radiative process involves the decay from a higher-energy 4f state to a lower-energy 4f state. Due to the shielding of the 4f orbitals, the energies of these transitions are largely independent of the ligand field, yielding the signature sharp emission spectra of lanthanides. The observed emission color is thus a direct consequence of the specific lanthanide ion's energy level structure [12] [1]. For instance:

- Eu³⁺ emits intense red light around 612 nm (⁵D₀ → ⁷F₂) [1].

- Tb³⁺ emits green light around 545 nm (⁵D₄ → ⁷F₅) [1].

- Er³⁺ and Tm³⁺ are known for their near-infrared (NIR) and upconversion emissions [14] [1].

Although the f-f transitions are Laporte-forbidden, they gain some allowedness through mixing with higher-energy electronic states of opposite parity (e.g., 5d orbitals) induced by the ligand field. The strength of this interaction, and thus the intensity of the emission, is influenced by the symmetry of the complex; lower symmetry generally enhances the radiative transition probability [12].

The Antenna Effect as a Radiative Pathway

The antenna effect (or photosensitization) is not a radiative transition itself but is the primary mechanism for populating the excited states that lead to radiative emission. This process involves a series of steps [3] [13]:

- Absorption: The organic antenna chromophore (ligand) absorbs a photon, promoting it to a singlet excited state.

- Intersystem Crossing (ISC): The sensitizer undergoes ISC to a longer-lived triplet excited state.

- Energy Transfer (ET): The energy from the ligand's triplet state is non-radiatively transferred to the resonant energy level of the Ln(III) ion.

- Emission: The Ln(III) ion relaxes radiatively to its ground state, emitting characteristic light.

Table 1: Key Radiative Transitions for Selected Ln(III) Ions

| Ln(III) Ion | Principal Radiative Transition | Emission Wavelength (nm) | Emission Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu³⁺ | ⁵D₀ → ⁷F₂ | ~612 | Red |

| Tb³⁺ | ⁵D₄ → ⁷F₅ | ~545 | Green |

| Nd³⁺ | ⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴I₉/₂ | ~880, ~1060 | Near-Infrared (NIR) |

| Yb³⁺ | ²F₅/₂ → ²F₇/₂ | ~980 | Near-Infrared (NIR) |

Non-Radiative Transition Pathways

Non-radiative decay pathways compete directly with radiative emission, deactivating the excited state of the Ln(III) ion without the emission of a photon. Minimizing these pathways is critical for achieving high luminescence quantum yields [12].

Vibrational Quenching

The dominant non-radiative pathway in many systems, especially for NIR-emitting lanthanides, is vibrational quenching. The energy gap between the emitting state and the next lower energy state is dissipated through vibrational energy matches with oscillators in the immediate environment [12]. High-energy oscillators are particularly efficient quenchers.

- O-H Oscillators: O-H bonds (~3500 cm⁻¹) are highly efficient quenchers of excited states. The presence of a single O-H oscillator from a coordinated water molecule can drastically reduce luminescence intensity [3] [12].

- N-H and C-H Oscillators: N-H bonds (~3300 cm⁻¹) and C-H bonds (~2950 cm⁻¹) also contribute to quenching, though they are less efficient than O-H oscillators [15].

- Mitigation Strategies: A primary design strategy is to replace high-energy oscillators with low-energy counterparts. For instance, deuterated bonds (O-D, C-D) and fluorinated bonds (C-F) have lower vibrational frequencies and are much less effective at promoting non-radiative decay [12]. The number of inner-sphere water molecules (q) coordinated to the Ln(III) center is a key parameter that can be determined from luminescence lifetime measurements in H₂O and D₂O [3] [15].

Other Non-Radiative Pathways

- Cross-Relaxation and Energy Migration: In concentrated systems, dipole-dipole interactions can lead to cross-relaxation between two nearby Ln(III) ions, deactivating the emitter. This can be mitigated by diluting the lanthanide ions in a host matrix or using specific ligand designs to increase intermolecular distances [12].

- Defect-Mediated Quenching: In lanthanide-doped nanocrystals, surface defects, lattice imperfections, and interactions with surface ligands or solvents can create non-radiative energy transfer pathways, severely reducing the upconversion quantum yield [14].

- Electronic Energy Back Transfer: In some cases, energy can be transferred back from the excited Ln(III) ion to a low-lying energy level of the ligand, a process that becomes more probable if the ligand's triplet state energy is too low [12].

Table 2: Major Non-Radiative Pathways and Mitigation Strategies

| Non-Radiative Pathway | Mechanism | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrational Quenching | Energy transfer to high-frequency vibrations (O-H, N-H, C-H) | Use deuterated solvents/ligands; employ fluorinated ligands; exclude water from the inner coordination sphere [12]. |

| Cross-Relaxation | Energy transfer between two nearby Ln(III) ions | Dilute Ln(III) ions in a host matrix; control Ln-Ln distance via molecular design [12]. |

| Energy Migration | Migration of excitation energy to a quenching site | Use core-shell nanostructures to isolate activators from surface quenchers [14]. |

| Defect-Mediated Quenching | Energy transfer to lattice defects or surface quenchers in nanomaterials | Synthesize high-quality nanocrystals with a passivating shell [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis

Accurate characterization of radiative and non-radiative pathways is essential for developing efficient luminescent materials.

Determining the Hydration Number (q)

The number of water molecules in the inner coordination sphere of a Ln(III) ion is a critical parameter for quantifying vibrational quenching.

Protocol for Eu³⁺ or Tb³⁺ Complexes (Horrocks' Method) [15]

- Sample Preparation: Prepare degassed solutions of the Ln(III) complex in H₂O and D₂O. Ensure identical concentration and buffering conditions.

- Lifetime Measurement: Measure the luminescence lifetime (τ) of the emitting state (⁵D₀ for Eu³⁺, ⁵D₄ for Tb³⁺) in both solvents. Use a pulsed excitation source and time-resolved detector.

- Calculation:

- For Tb³⁺: ( q = A (\tau{H₂O}^{-1} - \tau{D₂O}^{-1} - B) ), where A and B are empirically derived constants (e.g., A = 5 ms, B = 0.06 ms⁻¹ for Tb³⁺) [15].

- For Eu³⁺: A similar, ion-specific formula is applied.

This method leverages the significant difference in quenching efficiency between H₂O and D₂O to estimate the number of proximate water molecules.

Measuring Relative Quantum Yields (Φ)

The quantum yield is the ultimate measure of a complex's luminescence efficiency, representing the number of photons emitted per photon absorbed.

Conventional Gradient Method Protocol [15]

- Reference Standard: Select a luminescence standard with a known quantum yield (e.g., [Tb(L1)]⁻ with Φ = 0.47 [15]).

- Absorbance Matching: Prepare solutions of the sample and the standard with the same absorbance (typically < 0.1 at the excitation wavelength) to minimize inner filter effects.

- Emission Measurement: Measure the integrated luminescence intensity of both sample and standard upon excitation at the same wavelength.

- Calculation: The quantum yield is calculated using the formula: ( Φ{sample} = Φ{standard} \times (I{sample}/I{standard}) \times (A{standard}/A{sample}) \times (n{sample}^2/n{standard}^2) ) where ( I ) is integrated emission intensity, ( A ) is absorbance, and ( n ) is the refractive index of the solvent.

High-Throughput Cherenkov Radiation Method [15] This novel method allows for the rapid, simultaneous comparison of multiple complexes.

- Sample Arraying: Place solutions of terbium complexes (adjusted by ICP-OES to 5-25 nmol) in a well-plate.

- Cherenkov Excitation: Add a 10 μCi aliquot of the PET isotope ¹⁸F (as Na¹⁸F) to each well. The Cherenkov radiation emitted by the isotope serves as a broadband UV excitation source.

- Imaging: Acquire luminescence images using a small animal fluorescence imager with emission collection from 500-875 nm.

- Data Analysis: Quantify radiance using region-of-interest (ROI) analysis. The relative quantum yield is calculated by scaling the observed radiance by the compound's absorbance cross-section relative to the reference compound [15].

Visualization of Pathways and Processes

The following diagrams illustrate the core energy transfer mechanisms and experimental workflows.

Antenna Effect and Quenching Pathways

Diagram 1: Antenna effect and key deactivation pathways. The pathway illustrates light absorption by the ligand, intersystem crossing (ISC), energy transfer to the lanthanide, and subsequent radiative or non-radiative decay. Competing non-radiative pathways like vibrational quenching and back energy transfer are shown.

Quantum Yield Measurement Workflow

Diagram 2: Workflow for determining relative quantum yield via the conventional gradient method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Studying Ln(III) Transitions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O, CD₃OD) | Used to determine inner-sphere hydration number (q) via lifetime measurements and to reduce vibrational quenching in spectroscopic studies [12]. |

| β-Diketonate Ligands (e.g., HFA, TTA) | Classic antenna ligands with high triplet state energies, efficient at sensitizing Eu³⁺ and Tb³⁺ luminescence. Fluorinated versions (e.g., HFA) minimize vibrational quenching [13] [12]. |

| Macrocyclic Chelators (e.g., DO3A, DOTA derivatives) | Provide rigid, stable coordination cages that protect the Ln(III) ion from solvent access, minimizing q and non-radiative decay [15]. |

| Aromatic Sensitizers (e.g., Picolinates, Terpyridines) | Act as efficient "antennae" with strong absorption; their structures can be modified to optimize the energy gap between their triplet state and the Ln(III) accepting level [15] [13]. |

| Radionuclides (e.g., ¹⁸F as Na¹⁸F) | Source of Cherenkov radiation for high-throughput, relative quantum yield measurements of Tb complexes in a well-plate format [15]. |

| Reference Complexes (e.g., [Tb(L1)]⁻) | Complexes with known, high quantum yields (Φ) serve as essential standards for calibrating and determining the Φ of new compounds [15]. |

The rational design of highly luminescent Ln(III) complexes hinges on a deep understanding of radiative and non-radiative transition pathways. The strategic manipulation of the ligand field—through the choice of antenna chromophore, the exclusion of high-energy oscillators like O-H, and the control over ion-ion interactions—enables researchers to tip the balance in favor of efficient radiative emission. Advanced experimental protocols, from lifetime-based hydration number determination to innovative high-throughput screening methods, provide the necessary tools to quantify these effects. As this field progresses, the principles outlined in this guide will continue to underpin the development of next-generation lanthanide-based materials for advanced applications in sensing, bioimaging, photonics, and security technologies.

Intersystem Crossing and Triplet State Dynamics in Sensitization

In the field of photophysics, the efficient sensitization of luminescent materials hinges on the critical photophysical processes of intersystem crossing (ISC) and triplet state dynamics. These processes are particularly pivotal in the luminescence of lanthanide complexes, where organic ligands act as "antennas," absorbing light and transferring energy to the lanthanide ion, ultimately resulting in its characteristic sharp-line emission [3] [16]. The journey of energy from initial photon absorption to final lanthanide emission involves a intricate pathway through singlet and triplet excited states of the ligand. The efficiency of this pathway, especially the ISC from the ligand's singlet to triplet state and the subsequent dynamics of the triplet state, fundamentally dictates the overall luminescence quantum yield [17]. This technical guide delves into the mechanisms, current research, and experimental methodologies surrounding these core processes, providing a foundational resource for ongoing research in lanthanide luminescence and energy transfer.

Fundamental Energy Transfer Pathways

The sensitization of lanthanide ions (Ln³⁺) via organic ligands, known as the "antenna effect," follows a well-established sequence of photophysical events. A comprehensive visualization of this pathway, including a novel strategy for enhanced thermometry, is provided in the diagram below.

Photoabsorption and Intersystem Crossing: The process initiates when a ligand absorbs a photon, promoting it from the ground state (S₀) to an excited singlet state (S₁) [16]. The S₁ state then undergoes intersystem crossing, a spin-forbidden process whereby the molecule crosses to an excited triplet state (T₁). The efficiency of this ISC step is critical. Recent studies on lanthanide nanocrystals functionalized with specific ligands, such as carbazole-phosphine oxide hybrids (CzPPOA), have demonstrated ISC rates accelerated to less than 1 nanosecond, with conversion efficiencies reaching up to 98.6% [18]. This high efficiency is facilitated by the ligand's molecular design, which promotes strong spin-orbit coupling.

Triplet Energy Transfer and Quenching: The ligand's T₁ state then transfers its energy to a resonant accepting energy level of the Ln³⁺ ion, populating its emitting state [5] [16]. For complexes of Tb³⁺ and Eu³⁺, a small energy gap (ΔE(T₁−Ln*) of less than 2000 cm⁻¹ can lead to thermal competition; at elevated temperatures, energy can back-transfer from the Ln³⁺ ion to the ligand's T₁ state, quenching the luminescence [5]. This long-lived T₁ state is a primary limitation for applications like luminescent molecular thermometers, as it restricts thermal sensitivity.

The Energy Escape Pathway: A novel strategy to enhance performance involves creating an energy escape pathway from the ligand's T₁ state. As demonstrated in a Tb(III)–Nd(III) dinuclear complex, an alternative energy acceptor (e.g., Nd³⁺) with an energy level matched to the ligand triplet can be introduced. This provides a route for the T₁ state energy to rapidly drain away, shortening its lifetime and thereby reducing the probability of back-energy transfer that quenches the Tb³⁺ emission. This approach has yielded a record-high temperature sensitivity of 4.4% K⁻¹ in emission lifetime-based thermometry [5].

Current Research and Advancements

Recent investigations have significantly advanced the understanding and control of triplet state dynamics in sensitization.

Enhancing Triplet Energy Harvesting

A breakthrough in electroluminescence of insulating lanthanide nanocrystals was achieved through tailored ligand design. Functionalizing NaGdF₄:Tb nanocrystals with carbazole–phosphine oxide ligands (ArPPOA) created a soft electronic interface that efficiently harvests excitons [18]. Ultrafast spectroscopic studies confirmed that coordination to the nanocrystal surface accelerates ISC to sub-nanosecond timescales and enables triplet energy transfer efficiencies of up to 96.7%. This approach decouples charge transport from photon emission, allowing efficient electroluminescence from an otherwise insulating material and achieving an external quantum efficiency exceeding 5.9% for Tb³⁺ [18].

Computational Prediction of Triplet Energies

Predicting triplet energies is vital for designing efficient sensitizer-acceptor pairs. A recent computational method moves beyond static calculations by using quasiclassical molecular dynamics to sample vertical energy gaps along molecular vibrations [19]. This approach, which provides theoretical support for the "hot-band" mechanism of energy transfer, demonstrated excellent predictive performance against experimental triplet energies (R² = 0.97, MAE = 1.7 kcal/mol). This represents a significant improvement over conventional static, adiabatic calculations (R² = 0.51, MAE = 9.5 kcal/mol) and is particularly valuable for predicting E/Z-isomerization outcomes under energy transfer conditions [19].

Multiple Sensitization Pathways in Aqueous Media

The development of water-stable lanthanide luminophores is crucial for bioimaging but challenging due to water-induced quenching. Research on the small luminophore PAnt, which dynamically coordinates with Tb(III) and Eu(III) in water, revealed different sensitization mechanisms for Eu(III) and Tb(III) [20]. A combined photophysical and TD-DFT computational study showed that while the triplet state is involved for Tb(III), an intraligand charge-transfer (ILCT) state is likely the dominant pathway for sensitizing Eu(III). This understanding of multiple, metal-dependent pathways in aqueous media is key to developing improved bioimaging agents [20].

Quantitative Data and Analysis

The performance of lanthanide complexes is governed by quantitative relationships between energy levels, transfer rates, and quantum yields.

Table 1: Key Energy Transfer Parameters and Their Impact on Quantum Yield (ϕ)

| Parameter | Description | Optimal Range / Desired Characteristic | Impact on Quantum Yield (ϕ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE(S₁-T₁) | Energy gap between singlet and triplet states of the ligand | Small gap | Increases ISC rate, positively affecting ϕ [17] |

| ΔE(T₁-Ln*) | Energy gap between ligand triplet and lanthanide accepting level | 2000–4000 cm⁻¹ | Maximizes forward transfer, minimizes back-transfer [17] |

| k_ISC | Rate constant for intersystem crossing | High (>10⁹ s⁻¹) | Increases population of T₁, positive effect on ϕ [18] [17] |

| k_ET | Rate constant for triplet energy transfer to Ln³⁺ | High | Increases efficiency of sensitization (η_sens), positive effect on ϕ [18] |

| k_Ln | Decaying rate of the Ln³⁺ emitting state | Low | The main negative effect on ϕ; optimization is crucial [17] |

| Presence of LMCT | Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer state | Absent or high in energy | LMCT states can introduce strong quenching pathways, significantly altering the effects of other rates on ϕ [17] |

Table 2: Experimental Triplet Energy Transfer Efficiencies in Recent Studies

| System Description | Ligand / Sensitizer | Ln³⁺ Acceptor | Reported Triplet Energy Transfer Efficiency | Key Finding / Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Functionalized Nanocrystal [18] | tBCzPPOA | Tb³⁺ | 94.7% | Small T₁–⁵D₄ gap (0.33 eV) promotes high transfer. |

| Ligand-Functionalized Nanocrystal [18] | CzPPOA | Tb³⁺ | 96.7% | Near-unity transfer despite larger gap (0.49 eV); high PLQY of 25.55% in films. |

| Dinuclear Complex for Thermometry [5] | hfa/dptp ligands | Tb³⁺ / Nd³⁺ | N/A (Pathway utilized) | Introduction of Nd³⁺ energy escape pathway enhanced thermal sensitivity to 4.4% K⁻¹. |

Chemometric analysis of the rate equations governing these complexes has quantified the effects of various transition rates on the quantum yield. This analysis confirms that increasing the ISC rate (k_ISC) generally improves the quantum yield. Furthermore, it reveals that in systems with ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) states, the behavior is more complex, as several transition rates and their interactions can have significant effects with similar magnitudes, making the system more challenging to optimize [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section details the core experimental approaches for probing intersystem crossing and triplet state dynamics.

Probing Intersystem Crossing and Triplet Transfer Dynamics

Objective: To quantitatively determine the rates and efficiencies of ISC and triplet energy transfer in a ligand-lanthanide complex or nanocrystal system.

Materials:

- Ultrafast Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Setup: A femtosecond pump laser, white light continuum probe, and fast detector. This is essential for resolving sub-nanosecond ISC processes [18].

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence System: For measuring triplet state and lanthanide emission lifetimes (from nanoseconds to milliseconds).

- Sample: The lanthanide complex or nanohybrid of interest, dissolved in a degassed solvent (e.g., 2-MeTHF) to prevent oxygen quenching.

Procedure:

- Ultrafast ISC Kinetics:

- Excite the sample with a femtosecond pump pulse tuned to the ligand's absorption band.

- Probe the transient absorption spectrum from the UV to the near-IR (e.g., 350–1500 nm) at time delays from femtoseconds to nanoseconds.

- Identify the spectral signatures of the S₁ state (initial photoinduced absorption) and the T₁ state (evolving photoinduced absorption features).

- Perform kinetic analysis at key wavelengths to extract the ISC time constant. The acceleration of ISC upon coordination with lanthanide ions, often to <1 ns, is a key indicator of efficient coupling [18].

- Triplet Energy Transfer Efficiency:

- Measure the phosphorescence lifetime of the ligand's T₁ state in a reference compound, typically a Gd³⁺ complex (where energy transfer to the ion is negligible due to its high-energy states).

- Measure the T₁ lifetime of the ligand when coordinated to the emissive Ln³⁺ ion (e.g., Tb³⁺ or Eu³⁺).

- Calculate the triplet energy transfer efficiency (ηTET) using the formula: ηTET = 1 - (τTb / τGd) where τTb and τGd are the T₁ lifetimes in the Tb³⁺ and Gd³⁺ complexes, respectively. A substantial decrease in lifetime indicates efficient transfer [18].

Evaluating Thermal Sensitivity via Emission Lifetime

Objective: To characterize the performance of a lanthanide complex as a luminescent molecular thermometer, based on the temperature-dependent competition between emission and quenching pathways.

Materials:

- Temperature-Controlled Stage or Cryostat: Precise control from cryogenic to elevated temperatures (e.g., 100-400 K).

- Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) or Phosphorescence Lifetime Setup.

- Sample: The thermometric complex (e.g., [TbNd(hfa)₆(dptp)₂]) in solid state or solution [5].

Procedure:

- Place the sample in the temperature-controlled stage and allow thermal equilibration at a set starting temperature.

- Excite the sample with a pulsed light source and record the decay curve of the lanthanide emission (e.g., Tb³⁺ at 547 nm).

- Fit the decay curve to an appropriate model (e.g., single or multi-exponential) to extract the emission lifetime (τ) at that temperature.

- Incrementally increase the temperature and repeat steps 2-3 to collect lifetime data across the desired temperature range.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the emission lifetime (τ) or the relative change in lifetime ((τ-τref)/τref) as a function of temperature.

- Calculate the Relative Thermal Sensitivity (% K⁻¹) at a specific temperature T using the formula: S_r(T) = (1/τ) × |dτ/dT| × 100%

- The high sensitivity of 4.4% K⁻¹, as reported, stems from the introduced energy escape pathway that modulates the lifetime's temperature dependence [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Triplet State Dynamics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Investigation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Gadolinium (Gd³⁺) Complexes | Used as a reference compound to determine intrinsic ligand triplet state properties (energy, lifetime), as Gd³⁺ has no low-lying energy acceptors. | [Gd₂(hfa)₆(dptp)₂] used to characterize the unquenched triplet state of the ligands [5]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, d⁸-THF) | Used to minimize vibrational quenching, particularly from O-H oscillators, thereby extending luminescence lifetimes and simplifying kinetic studies. | Measurement of luminescence lifetimes in H₂O vs. D₂O is a standard method for estimating the number of inner-sphere water molecules in a complex [3]. |

| Carbazole-Phosphine Oxide Ligands (ArPPOA) | Act as both sensitizers and charge-transport media in nanohybrids. Their intramolecular charge-transfer character can be tuned to optimize ISC and energy transfer. | CzPPOA and tBCzPPOA ligands used to functionalize NaGdF₄:Tb nanocrystals, achieving >96% triplet energy transfer efficiency [18]. |

| Hexafluoroacetylacetonate (hfa) Ligands | A β-diketonate ligand used to form stable, highly luminescent complexes with lanthanides. Its triplet energy level is suitable for sensitizing ions like Tb³⁺ and serves as a donor in energy escape designs. | Used in the dinuclear [TbNd(hfa)₆(dptp)₂] complex to enable the energy escape pathway to Nd³⁺ [5]. |

| Heteronuclear Ln³⁺ Complexes | Designed to study inter-ion energy transfer and create energy escape pathways, which can be used to modulate triplet state lifetimes and enhance sensor function. | The Tb(III)–Nd(III) complex where energy transfer from hfa to Nd³⁺ provides a short-lived excited state for enhanced thermometry [5]. |

Shielding Effects of 4f Electrons and Coordination Geometry Influences

The unique photophysical properties of trivalent lanthanide ions (Ln³⁺) and their complexes have established them as indispensable components in modern technological applications, ranging from lighting and displays to biomedical imaging and sensing [1]. The distinctive optical behavior of these elements primarily stems from the intricate shielding effects of 4f electrons and the profound influence of coordination geometry around the lanthanide center [21]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of these fundamental principles, framed within the broader context of advancing luminescence and energy transfer research in lanthanide-based systems.

The exceptional electronic configuration of lanthanides, characterized by progressive filling of the 4f orbitals across the series, creates a unique scenario where the optically active 4f electrons are shielded by fully occupied 5s² and 5p⁶ outer orbitals [1] [21]. This shielding results in weak interactions with the surrounding ligand environment and crystal field effects, making the 4f-4f electronic transitions remarkably insensitive to external perturbations compared to transition metal complexes [22] [1]. Consequently, Ln³⁺ ions exhibit sharp, characteristic emission lines rather than broad bands, with relatively long excited-state lifetimes typically ranging from microseconds to milliseconds [23] [24].

Despite the shielding provided by outer orbitals, the coordination environment exerts subtle yet crucial influences on the luminescent properties of lanthanide complexes through symmetry imposition and vibronic coupling. The coordination geometry directly affects the radiative transition probabilities by mixing opposite parity states into the 4f wavefunctions, partially relaxing the Laporte forbiddenness of f-f transitions [23]. This relationship between molecular structure and photophysical behavior provides the foundation for rational design of lanthanide-based materials with tailored optical properties for specific applications.

Fundamental Electronic Structure of Lanthanide Ions

4f Orbital Shielding and Its Consequences

The electronic structure of trivalent lanthanide ions is characterized by the progressive filling of the 4f orbitals, which are deeply embedded within the electronic cloud and shielded by outer 5s² and 5p⁶ orbitals [1] [21]. This shielding results in several distinctive photophysical properties:

Weak Environmental Coupling: The 4f orbitals experience minimal perturbation from the surrounding ligand environment, causing 4f-4f transitions to remain largely unaffected by ligand field or host lattice variations [1]. This results in characteristic sharp emission lines that are elemental fingerprints, unlike the broad emission bands typically observed in transition metal complexes or organic fluorophores [1].

Parity-Forbidden Transitions: Intraconfigurational 4f-4f transitions are Laporte-forbidden, leading to weak absorption coefficients and long excited-state lifetimes (microseconds to milliseconds) [22] [24]. The shielding effect reduces the extent of mixing with opposite parity configurations, maintaining the forbidden character of these transitions.

Limited Spectral Shifting: The emission spectra of Ln³⁺ ions show minimal Stokes shift and maintain consistent spectral positions across different host matrices due to the protection of 4f orbitals from external influences [1].

Table 1: Characteristic Emission Properties of Selected Trivalent Lanthanide Ions

| Ln³⁺ Ion | Primary Emission Wavelength (nm) | Color | Lifetime Range | Main Transitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu³⁺ | 612-615 | Red | µs-ms | ^5^D~0~ → ^7^F~J~ |

| Tb³⁺ | 545 | Green | µs-ms | ^5^D~4~ → ^7^F~J~ |

| Sm³⁺ | 645-650 | Orange-red | µs-ms | ^4^G~5/2~ → ^6^H~J~ |

| Dy³⁺ | 575, 480 | Yellow | µs-ms | ^4^F~9/2~ → ^6^H~J~ |

| Yb³⁺ | 980 | NIR | µs-ms | ^2^F~5/2~ → ^2^F~7/2~ |

| Nd³⁺ | 1064 | NIR | µs-ms | ^4^F~3/2~ → ^4^I~J~ |

Theoretical Framework: Judd-Ofelt Theory and Beyond

The Judd-Ofelt theory, established in 1962, provides the fundamental framework for understanding 4f-4f transition intensities in lanthanide ions [22]. The theory accounts for how the ligand field influences transition probabilities through several key mechanisms:

Forced Electric Dipole (FED) Mechanism: In non-centrosymmetric ligand fields, the odd component of the crystal field Hamiltonian mixes opposite parity configurations (4f^N-1^5d^1^, 4f^N-1^5g^1^, etc.) into the 4f^N^ configuration, partially relaxing the parity selection rule and enabling electric dipole transitions [22].

Dynamic Coupling (DC) Mechanism: This mechanism involves interaction between lanthanide 4f electrons and the secondary electric field induced by polarization of ligand electron density due to the incident radiation field [22]. The DC mechanism can dominate in some Eu³⁺ complexes and is responsible for hypersensitive transitions that exhibit unusual intensity dependence on the chemical environment.

Magnetic Dipole Transitions: Transitions such as the ^5^D~0~ → ^7^F~1~ in Eu³⁺ are magnetic dipole in nature and are practically independent of the chemical environment, making them useful as internal references for determining other radiative rates [22].

The Judd-Ofelt theory parameterizes transition intensities using three intensity parameters (Ω~2~, Ω~4~, Ω~6~) that contain information about the ligand field and coordination environment, with Ω~2~ being particularly sensitive to the asymmetry and covalency of the lanthanide site [22].

Coordination Geometry and Its Influence on Luminescence

Coordination Number and Symmetry Considerations

Lanthanide ions typically exhibit high coordination numbers (8-12) due to their large ionic radii, with coordination geometry playing a critical role in determining luminescence efficiency through symmetry control [23] [25]. The coordination polyhedron directly influences the extent of 4f-5d orbital mixing, which governs the radiative transition probabilities according to the Judd-Ofelt theory [23].

Table 2: Common Coordination Geometries in Lanthanide Complexes and Their Photophysical Impact

| Coordination Number | Common Geometries | Point Group Symmetry | Radiative Rate Influence | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Pentagonal bipyramid, Capped octahedron | C~2v~, D~5h~ | High due to pronounced asymmetry | [Eu(β-diketonate)~3~(L)~2~] |

| 8 | Square antiprism, Trigonal dodecahedron, Bicapped trigonal prism | D~4d~, D~2d~, C~2v~ | Moderate to high | Q[Ln(L)~4~] tetrakis complexes |

| 9 | Tricapped trigonal prism, Capped square antiprism | D~3h~, C~4v~ | Lower due to higher symmetry | [Ln(H~2~O)~9~]³⁺ aqua complexes |

Seven-Coordinate Lanthanide Complexes

Seven-coordinate lanthanide complexes have attracted significant research interest due to their highly asymmetric structures that enhance radiative transition rates [23]. The lower coordination number creates a more distorted coordination polyhedron compared to the more common eight or nine-coordinate geometries, resulting in several distinctive photophysical characteristics:

Enhanced Radiative Rates: The pronounced asymmetry in seven-coordinate structures promotes greater mixing of 4f and 5d orbitals, increasing the radiative rate constant (k~r~) and consequently improving luminescence efficiency [23]. For example, seven-coordinate Tb³⁺ complexes can achieve photosensitized quantum yields as high as 86% [23].

Large Crystal Field Splitting: The low symmetry environment creates substantial crystal field splitting, which can be exploited for applications in temperature sensing and oxygen detection [23].

Structural Diversity: Seven-coordinate geometries include pentagonal bipyramidal, capped octahedral, and capped trigonal prismatic arrangements, each imparting distinct photophysical properties based on the specific symmetry elements present [23].

Eight- and Nine-Coordinate Systems

Eight-coordinate lanthanide complexes represent one of the most common coordination environments, particularly in homoleptic tetrakis complexes of the type Q[Ln(L)~4~] [22]. These systems typically form {LnO~8~} polyhedra with geometries including square antiprism (D~4d~), trigonal dodecahedron (D~2d~), and bicapped trigonal prism (C~2v~) [22] [23]:

Homoleptic Tetrakis Complexes: The Q[Ln(L)~4~] architecture, where L represents bidentate organic ligands like β-diketonates, creates a homoleptic coordination environment that prevents coordination of solvent molecules with high-energy oscillators (e.g., O-H bonds), thereby minimizing non-radiative decay pathways and enhancing luminescence quantum yields [22].

Steric Effects: The four identical ligands in tetrakis complexes create steric interactions that prevent binding of other molecules to the metal ion, resulting in improved emission quantum yields compared to tris-complex systems of the same ligand [22].

Counterion Influence: While spectroscopic properties primarily depend on the anionic ligand, the counterion (Q⁺) in tetrakis complexes can disturb the chemical environment of the anionic group through intermolecular interactions and steric hindrances, enabling modulation of photophysical properties [22].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Spectroscopic Techniques for Probing Shielding and Geometry Effects

Advanced spectroscopic methods are essential for characterizing the relationships between coordination geometry and luminescence properties in lanthanide complexes:

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Emission spectra, particularly for Eu³⁺, provide detailed information about site symmetry through analysis of ^5^D~0~ → ^7^F~J~ transition splitting patterns. The number of crystal field components correlates with the site symmetry of the Eu³⁺ chemical environment, with lower symmetries (C~2~, C~i~, C~s~) producing the maximum (2J+1) components [22].

Lifetime Measurements: Excited-state lifetime determinations in different media (H~2~O vs. D~2~O) enable quantification of inner-sphere water molecules and assessment of non-radiative decay pathways, providing insight into how coordination environment affects luminescence efficiency [23].

Magnetic Circular Dichroism (MCD): This technique provides information about electronic energy level structure and is particularly useful for analyzing systems with degenerate ground states, complementing traditional luminescence spectroscopy [21].

X-ray Crystallography: Single-crystal structural analysis remains the definitive method for determining coordination geometry and understanding structure-property relationships in lanthanide complexes [22] [23].

Theoretical Modeling Approaches

Computational methods have become increasingly important for interpreting experimental data and predicting luminescence properties:

Judd-Ofelt Analysis: Parameterization of 4f-4f transition intensities using Ω~2~, Ω~4~, and Ω~6~ parameters provides quantitative information about the coordination environment, with Ω~2~ being particularly sensitive to ligand polarizability and complex asymmetry [22].

Crystal Field Modeling: Ligand field parameters (B~q~^k^) can be determined from spectroscopic data or calculated using ab initio methods like complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) calculations, enabling correlation between structural features and optical properties [21].

Energy Transfer Calculations: Theoretical models for non-radiative energy transfer processes, including exchange, dipole-dipole, dipole-quadrupole, and quadrupole-quadrupole mechanisms, help elucidate how coordination geometry influences sensitization efficiency [26].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for characterizing shielding and geometry effects in lanthanide complexes

Advanced Applications and Material Systems

Lanthanide-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks (LnMOFs)

Lanthanide metal-organic frameworks represent an important class of materials where coordination geometry and shielding effects are exploited for advanced applications [25] [24]. In LnMOFs, lanthanide ions serve as structural nodes connected by organic linkers, creating extended structures with unique photophysical properties:

Energy Transfer Control: The periodic arrangement of lanthanide centers and organic linkers in LnMOFs enables precise control over energy transfer processes, including ligand-to-metal energy transfer (LMET), metal-to-metal energy transfer (MMET), and ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) [25].

Sensing Applications: The transformative energy transfer processes in luminescent LnMOFs make them excellent materials for physical sensing (temperature, pressure, mechanical stress) and chemical sensing (metal ions, small molecules) applications [24].

Anti-Counterfeiting Technologies: The sharp emission lines and long lifetimes of LnMOFs, combined with their tunable emission color through lanthanide doping, make them ideal for advanced anti-counterfeiting materials with complex, difficult-to-replicate spectral signatures [25].

Electroluminescent Materials

Recent advances have demonstrated efficient electroluminescence from insulating lanthanide fluoride nanocrystals functionalized with specially designed organic ligands [18]. In these systems:

Ligand Design Principle: Carbazole-phosphine oxide ligands (e.g., CzPPOA) with carboxyl and P=O coordination sites effectively sensitize lanthanide nanocrystals by modulating intraligand charge transfer characteristics [18].

Energy Transfer Dynamics: Ultrafast spectroscopic studies reveal that strong coupling between functionalized ligands and lanthanide nanocrystals facilitates intersystem crossing (<1 ns) and highly efficient triplet energy transfer to nanocrystals (up to 96.7%) [18].

Device Performance: Through careful control of dopant composition and concentration, wide-ranging multicolour electroluminescence can be achieved without altering device architecture, reaching external quantum efficiencies exceeding 5.9% for Tb³⁺ [18].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Shielding and Geometry Effects

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Diketonate Ligands | thenoyltrifluoroacetonate (TTA), dibenzoylmethane (DBM) | Primary sensitizing ligands | Efficient antenna effect, formation of stable complexes |

| Ancillary Ligands | 1,10-phenanthroline, 2,2'-bipyridine | Saturate coordination sphere | Shield Ln³⁺ from solvent quenching, enhance structural rigidity |

| Counterions | Alkylammonium, imidazolium, inorganic cations | Charge balance in tetrakis complexes | Modulate intermolecular interactions, affect crystal packing |

| Lanthanide Salts | LnCl~3~, Ln(ClO~4~)~3~, Ln(CF~3~SO~3~)~3~ | Ln³⁺ source | Varying anion coordinating ability influences final structure |

| Solvents | Acetonitrile, dimethylformamide, ethanol | Reaction medium | Polarity and donor properties affect complex formation |

The intricate relationship between 4f electron shielding effects and coordination geometry in lanthanide complexes represents a fundamental aspect of their photophysical behavior that continues to inspire both basic research and technological innovation. The shielding of 4f orbitals by outer 5s and 5p electrons creates a unique electronic scenario where transitions are largely protected from environmental fluctuations, yet the coordination geometry exerts precise control over transition probabilities through symmetry imposition.

Future research directions in this field include the development of more sophisticated theoretical models that can accurately predict both optical and magnetic properties based on molecular structure, the design of heteroleptic complexes with optimized coordination environments for specific applications, and the exploration of lanthanide complexes in emerging technologies such as quantum information processing and neuromorphic computing. The continued refinement of our understanding of how coordination geometry influences shielding effects will undoubtedly lead to new generations of lanthanide-based materials with enhanced performance and novel functionalities.

Understanding the subtle interplay between the shielded 4f electrons and the coordination environment remains essential for advancing luminescence and energy transfer research in lanthanide systems. As characterization techniques and theoretical methods continue to improve, researchers will gain increasingly precise control over the photophysical properties of lanthanide complexes through rational design of their coordination geometry, enabling new applications across diverse fields from biomedical imaging to optical communications.

Advanced Material Design and Biomedical Implementation Strategies

Ligand Engineering for Optimal Energy Transfer Efficiency

In the field of lanthanide-based luminescence, achieving high efficiency is paramount for applications ranging from electroluminescent devices and advanced sensors to bioimaging and anti-counterfeiting technologies. The intrinsic electronic structure of trivalent lanthanide ions (Ln³⁺), characterized by shielded 4f orbitals, results in sharp, characteristic emission lines but also leads to inherently weak light absorption due to parity-forbidden 4f-4f transitions. Ligand engineering has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome this fundamental limitation, enabling efficient light emission through sophisticated energy transfer mechanisms known as the "antenna effect." This process involves the absorption of light by organic ligands surrounding the lanthanide center, followed by intersystem crossing and subsequent energy transfer to the lanthanide ion's excited states, ultimately resulting in strong, characteristic lanthanide emission [1].

The precise control of energy transfer pathways through molecular design represents a critical frontier in photophysical research. Recent breakthroughs demonstrate that tailored ligand structures can dramatically enhance luminescence efficiency by optimizing key steps in the energy transfer cascade, including intersystem crossing rates, triplet energy matching, and mitigation of competing quenching processes. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, quantitative performance metrics, and experimental methodologies underpinning modern ligand engineering approaches for achieving optimal energy transfer efficiency in lanthanide-based systems, with particular emphasis on emerging design strategies that push the boundaries of photophysical performance [18] [1] [5].

Fundamental Energy Transfer Mechanisms

The photophysical processes in lanthanide complexes follow several well-defined pathways where ligand engineering plays a decisive role in determining overall efficiency. The primary mechanisms include the antenna effect, ligand-to-metal energy transfer (LMET), ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT), and metal-to-metal energy transfer (MMET). Understanding these pathways provides the foundation for rational ligand design.

The Antenna Effect and LMET: This represents the most common sensitization pathway in lanthanide complexes. The process begins with photon absorption by the organic ligand, promoting it to a singlet excited state (S₁). Through intersystem crossing (ISC), the excited electron transitions to a triplet state (T₁). The energy from this triplet state is then transferred to the emitting energy level of the lanthanide ion. The efficiency of this process hinges critically on the energy gap between the ligand's T₁ state and the acceptor level of the Ln³⁺ ion, with optimal matching being crucial for high transfer rates [25] [1].

Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): In some systems, particularly those involving certain metal clusters, LMCT states can compete with or disrupt the desired energy transfer pathway. For instance, in lanthanide-titanium-oxo clusters (LTOCs), LMCT to Ti⁴⁺ can effectively quench lanthanide luminescence. Strategic ligand design to replace LMCT-inducing ligands with non-LMCT alternatives has been shown to dramatically enhance luminescence output by eliminating this deleterious pathway [27].

Metal-to-Metal Energy Transfer (MMET): In heteronuclear systems containing different lanthanide ions, energy can be transferred directly between metal centers. This pathway is exploited in dinuclear complexes, such as Tb(III)-Nd(III) systems, where energy escape pathways from the ligand triplet state can be created to develop advanced molecular thermometers with enhanced temperature sensitivity [5].

The following diagram illustrates the primary energy transfer pathways and competing processes in engineered lanthanide complexes.

Diagram 1: Energy transfer pathways and competing processes in lanthanide complexes. Optimal LMET leads to efficient Ln³⁺ emission, while LMCT and poor energy matching cause quenching.

Quantitative Performance of Engineered Ligand Systems

Recent research has yielded quantitative data on the performance of various engineered ligand systems. The table below summarizes key photophysical parameters for selected ligand architectures, highlighting the profound impact of molecular structure on energy transfer efficiency.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Engineered Ligand Systems in Lanthanide Complexes and Nanocrystals

| Ligand / System | Ln³⁺ Emitter | Key Photophysical Parameters | Reported Efficiency | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CzPPOA [18] | Tb³⁺ | ISC: <1 ns; Triplet Energy Transfer: 96.7%; PLQY (film): 25.55% | External Quantum Efficiency: >5.9% | Electroluminescence Devices |

| tBCzPPOA [18] | Tb³⁺ | T₁–⁵D₄ Energy Gap: 0.33 eV; Triplet Energy Transfer: 94.7% | N/A | Electroluminescence Devices |

| TbNd(hfa)₆(dptp)₂ [5] | Tb³⁺ | Energy escape pathway to Nd³⁺; Short-lived hfa T₁ state | Thermal Sensitivity: 4.4% K⁻¹ | Luminescent Thermometry |

| LTOCs (LMCT-Minimized) [27] | Eu³⁺ | Suppression of Ligand-to-Ti⁴⁺ Charge Transfer | "Remarkable enhancement" in intensity | Fundamental Photochemical Studies |