Inorganic Semiconductor Photocatalysis: Principles, Mechanisms, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of inorganic semiconductor photocatalysis, detailing the fundamental reaction principles that govern this transformative technology.

Inorganic Semiconductor Photocatalysis: Principles, Mechanisms, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of inorganic semiconductor photocatalysis, detailing the fundamental reaction principles that govern this transformative technology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the photophysical mechanisms of charge carrier generation and separation, surveys the latest material systems from metal oxides to heterostructures, and analyzes key applications in environmental remediation and antibacterial therapy. The content further addresses critical challenges such as rapid charge recombination and limited visible-light absorption, offering strategic optimization pathways including bandgap engineering and morphology control. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of material performance and outlines future trajectories for integrating photocatalysis into biomedical and clinical research, highlighting its potential for drug synthesis, targeted therapies, and advanced sterilization.

The Photocatalytic Blueprint: Unraveling Core Principles and Mechanisms

Photocatalysis represents a green and developing technology that utilizes semiconductors to convert photon energy into chemical energy, driving a wide array of chemical reactions. This field has attracted significant scientific attention since the groundbreaking report of the Honda-Fujishima effect in 1972, which demonstrated the electrochemical photolysis of water using a titanium dioxide (TiO₂) electrode under ultraviolet (UV) light. [1] [2] This discovery established the foundational principle for using semiconductors to harness light energy for chemical processes, a phenomenon first observed in 1911 but largely unexplored until the late 20th century. [3]

The core appeal of photocatalysis lies in its ability to use light—a clean, abundant, and renewable energy source—to initiate chemical transformations under mild conditions. [4] [5] This makes it a powerful tool in addressing contemporary global challenges, including the rising demand for clean energy, environmental pollution, and the need for sustainable water treatment technologies. [4] [6] [3] In particular, its applications in the degradation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and other emerging contaminants have positioned photocatalysis as a critical advanced oxidation process (AOP) for environmental remediation. [7] [6]

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

The Photocatalytic Process

The activation of a semiconductor photocatalyst is dependent on its bandgap energy—the energy difference between its valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB). [4] [6] When a photocatalyst absorbs a photon with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, it prompts the excitation of an electron (e⁻) from the VB to the CB, generating a positively charged hole (h⁺) in the VB. This creates a photoinduced electron-hole pair. [4] [6] [3] The subsequent separation and migration of these charge carriers to the semiconductor surface is crucial, as they drive reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively. [6]

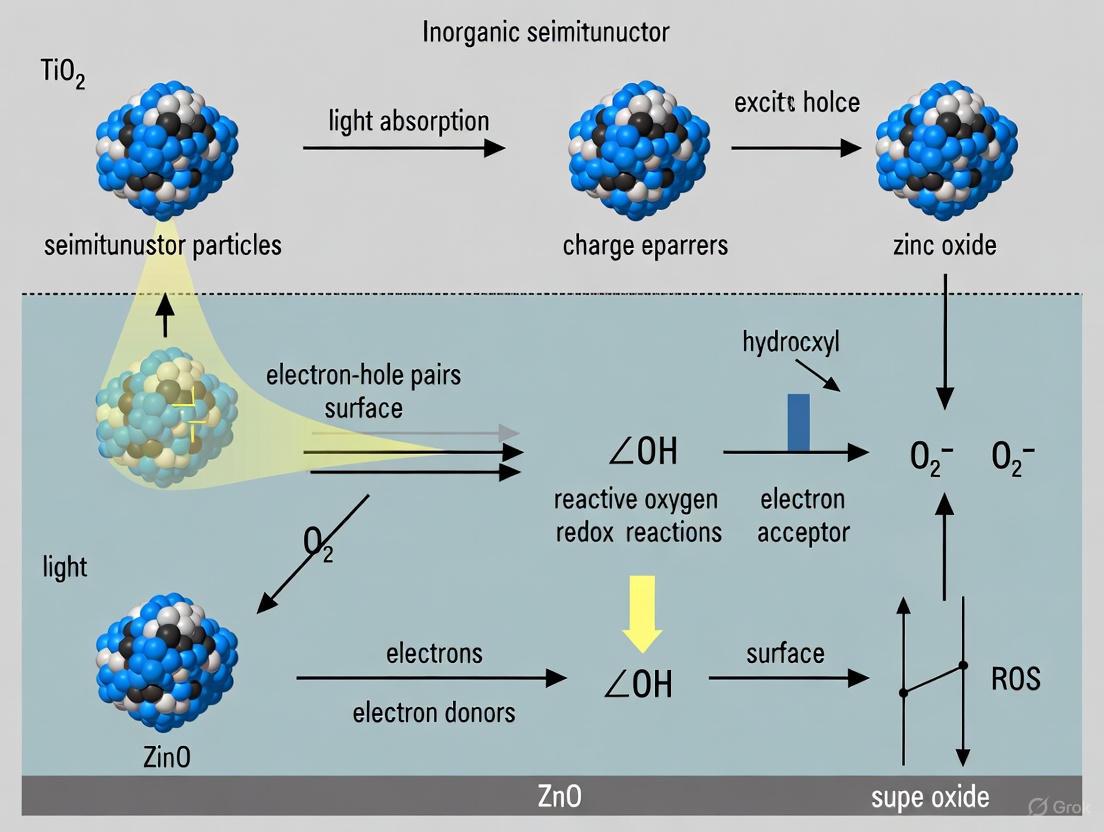

For the process to be effective, the recombination of these electron-hole pairs must be minimized. The separated charges then interact with adsorbed species, such as water and oxygen, to generate highly reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS, primarily the hydroxyl radical (•OH) and superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), are the key agents responsible for the oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. [4] [6] The following diagram illustrates this fundamental mechanism.

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Considerations

The thermodynamic driving force for photocatalysis is the photo-generated potential that enables redox reactions. [8] A critical concept is the band gap energy, which determines the minimum photon energy required for activation. While UV light (which constitutes only about 5% of the solar spectrum) is effective for wide-bandgap semiconductors like TiO₂, recent research focuses intensely on developing visible-light-responsive photocatalysts to more efficiently utilize solar energy. [6] [5] Kinetic analysis often employs models like Langmuir-Hinshelwood to describe the surface reaction rates, where the efficiency is intrinsically linked to charge carrier dynamics and the suppression of electron-hole recombination. [8]

Key Photocatalytic Materials and Synthesis

Classes of Photocatalysts

Photocatalytic materials are primarily semiconductors, with early and common examples including TiO₂, ZnO, WO₃, and CdS. [4] [6] Their performance is governed by properties such as light absorption range, charge separation efficiency, and surface area. A significant challenge with conventional semiconductors like TiO₂ is their large bandgap, which restricts activity to UV light. [6] This limitation has spurred the development of novel materials:

- Metal Oxides and Doped Materials: Introducing dopants (e.g., metal or non-metal atoms) into a semiconductor lattice can create mid-gap states, narrowing the effective bandgap and extending absorption into the visible light region. [4] [6]

- Bismuth-Based Perovskites: Materials like Bi₂WO₆, Bi₂MoO₆, and BiFeO₃ have emerged as promising visible-light-active photocatalysts. Their unique electronic structure, involving Bi 6s and O 2p orbitals, facilitates visible light absorption and charge carrier mobility. They are particularly effective for degrading pharmaceutical compounds. [9]

- Heterojunctions: Constructing interfaces between two different semiconductors (e.g., S-scheme or Z-scheme heterojunctions) can significantly enhance charge separation by creating an internal electric field, thereby boosting photocatalytic efficiency. [6] [9]

Green Synthesis and Nanotechnology

The principles of green chemistry encourage the use of biologically mediated synthesis for photocatalysts, employing plant extracts or microorganisms. This approach is environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and reduces the use of hazardous chemicals. [4] Furthermore, nanotechnology plays a pivotal role. Engineering materials at the nanoscale drastically increases their surface-area-to-volume ratio, providing more active sites for reactions and improving light absorption, which collectively enhances photocatalytic performance. [3]

Table 1: Common Photocatalytic Materials and Their Properties

| Material Class | Example Materials | Band Gap (eV) | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides | TiO₂, ZnO | ~3.0 - 3.2 | High stability, UV-active, low cost | Water splitting, self-cleaning surfaces [4] [1] |

| Bismuth-Based Perovskites | Bi₂WO₆, Bi₂MoO₆ | ~2.5 - 2.9 | Visible-light responsive, tunable morphology | Pharmaceutical degradation [9] |

| Sulfide & Other Semiconductors | CdS, ZnS, Cu₂O | ~2.0 - 2.4 | Narrow bandgap, but may suffer from photocorrosion | Selective organic synthesis [4] [6] |

| Doped/Hybrid Materials | N-doped TiO₂, TiO₂/g-C₃N₄ heterojunction | Tunable | Enhanced visible light absorption, reduced charge recombination | Broad-spectrum pollutant degradation [6] [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of Bi-based Perovskite Photocatalysts (Hydrothermal Method)

A common and effective method for synthesizing controlled nanostructures like Bi₂WO₆ nanosheets or nanoflowers is the hydrothermal method. [9]

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O) and sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na₂WO₄·2H₂O) in deionized water. The Bi precursor is often dissolved in a dilute acid (e.g., nitric acid) to prevent hydrolysis, while the W precursor is dissolved in deionized water.

- Mixing and Stirring: Combine the two solutions under vigorous magnetic stirring for 30-60 minutes to form a homogeneous precursor suspension.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the mixture into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. Seal the autoclave and maintain it at a specific temperature (typically 120-180 °C) for a set duration (e.g., 12-24 hours). The temperature and time critically control the crystal size and morphology.

- Product Recovery: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool to room temperature naturally. Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation or filtration.

- Washing and Drying: Wash the solid product repeatedly with deionized water and absolute ethanol to remove ionic residuals. Dry the sample in an oven at 60-80 °C for several hours.

- Calcination (Optional): For certain applications, the dried powder may be calcined in a muffle furnace at a predetermined temperature (e.g., 400-500 °C) for 2-4 hours to enhance crystallinity.

Protocol for Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceuticals

A standard experiment to evaluate the efficiency of a photocatalyst in degrading an active pharmaceutical ingredient (e.g., tetracycline) involves the following steps: [7] [9]

- Reaction Setup: A cylindrical borosilicate glass reactor is typically used. A light source (e.g., a Xe lamp with a UV-cutoff filter for visible-light experiments) is positioned at a fixed distance from the reactor. The system is often equipped with magnetic stirring and a water-cooling jacket to maintain a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Prepare an aqueous solution of the target pollutant (e.g., 20 mg/L tetracycline). A specific dosage of the photocatalyst (e.g., 0.5 g/L) is added to the solution. Before illumination, the suspension is stirred in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish an adsorption-desorption equilibrium on the catalyst surface.

- Illumination and Sampling: Turn on the light source to initiate the photocatalytic reaction. At regular time intervals (e.g., every 10-15 minutes), withdraw a fixed volume of the suspension sample.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge or filter the sampled suspension to remove the photocatalyst particles. Analyze the clear filtrate using:

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometry: To monitor the decrease in the characteristic absorption peak of the pollutant.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): To quantify the concentration of the parent pollutant and identify any intermediate products.

- Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Analysis: To determine the extent of mineralization (conversion of organic carbon to CO₂).

The degradation efficiency can be calculated as: Degradation Efficiency (%) = [(C₀ - Cₜ) / C₀] × 100%, where C₀ is the initial concentration and Cₜ is the concentration at time t.

Advanced Material Design and Optimization Strategies

To overcome the inherent limitations of pristine semiconductors, such as rapid charge recombination and limited light absorption, several advanced design strategies are employed. The following diagram summarizes the primary approaches for enhancing photocatalytic performance.

Modern Applications

Environmental Remediation and Wastewater Treatment

Photocatalysis has proven highly effective as an Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) for wastewater treatment. [6] It is particularly adept at degrading recalcitrant organic pollutants that conventional biological plants cannot remove, including:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs): Antibiotics like tetracycline, levofloxacin, and ofloxacin. [7] [9]

- Pesticides and Industrial Chemicals. [6]

- Microplastics and Endocrine Disruptors. [6]

The process offers key advantages over other AOPs like ozonation or Fenton reactions, including operation under mild conditions, potential utilization of solar energy, minimal sludge production, and the ability to achieve complete mineralization of pollutants to CO₂ and H₂O. [6]

Energy Production

The original Honda-Fujishima effect laid the groundwork for photocatalytic water splitting. In this process, a semiconductor uses light energy to split water molecules (H₂O) into hydrogen (H₂) and oxygen (O₂). [4] [1] The produced hydrogen is a clean and sustainable fuel, making this application crucial for the global energy landscape. [3] Related processes include the photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide (CO₂), which can transform this greenhouse gas into useful hydrocarbon fuels (e.g., methane), mimicking natural photosynthesis in a process known as artificial photosynthesis. [1] [2]

Other Applications

The versatility of photocatalysis extends to several other domains:

- Organic Synthesis: Photoredox catalysis, especially in continuous flow reactors, enables novel and sustainable pathways for forming C-C and C-heteroatom bonds under mild conditions, which is valuable for pharmaceutical development. [10] [5]

- Antimicrobial and Antifouling Surfaces: The strong oxidative power of photo-generated holes and ROS can inactivate bacteria and viruses, leading to self-disinfecting surfaces. The antifouling effect, where photocatalysts decompose organic dirt, has been commercialized in self-cleaning glass and tiles. [2]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Photocatalysis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | A benchmark, wide-bandgap semiconductor; highly stable and non-toxic. [4] [1] | Used as a reference material to compare the activity of newly developed photocatalysts. [4] |

| Bismuth Nitrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O) | A common precursor for synthesizing bismuth-based perovskite photocatalysts. [9] | Reacts with tungstate or molybdate salts to form Bi₂WO₆ or Bi₂MoO₆ via hydrothermal synthesis. [9] |

| Sodium Tungstate (Na₂WO₄·2H₂O) | A source of tungsten for the synthesis of tungsten-containing photocatalysts. [9] | Key reactant for the preparation of Bi₂WO₆. [9] |

| Iridium-based Complexes (e.g., [Ir(ppy)₃]) | Homogeneous metal-based photoredox catalysts. [10] [5] | Used in organic synthesis under visible light in flow reactors for single-electron transfer processes. [10] |

| Organic Dyes (e.g., Rose Bengal) | Metal-free, organic photoredox catalysts activated by visible light. [5] | A cost-effective and readily available alternative to metal complexes for certain oxidative transformations. [5] |

| Pollutant Model Compounds | Standardized organic compounds used to evaluate photocatalytic efficiency. | Tetracycline, methylene blue, or rhodamine B are commonly used to test degradation performance. [7] [9] |

The field of photocatalysis has evolved dramatically from its foundational discovery with the Honda-Fujishima effect to a diverse and sophisticated technology with critical applications in environmental sustainability and green chemistry. The ongoing research focuses on overcoming the primary challenges of low quantum efficiency, limited visible-light utilization, and the long-term stability of photocatalysts. [6] [9]

Future directions are likely to emphasize the rational design of low-cost, non-toxic, and highly efficient visible-light photocatalysts, the integration of photocatalysis with other technologies (e.g., electrocatalysis, membrane filtration), and the advancement towards pilot-scale and industrial applications. [6] [10] [9] The continued synergy between materials science, nanotechnology, and reaction engineering will be paramount in fully realizing the potential of photocatalysis to contribute to a more sustainable and clean future.

Semiconductor band theory is the fundamental quantum mechanical framework that describes the behavior of electrons in crystalline solids and serves as the cornerstone of modern electronics and optoelectronics [11]. This theory explains how the discrete energy levels of isolated atoms evolve into continuous energy bands when atoms form a periodic crystal lattice, primarily due to the overlap of atomic orbitals and quantum mechanical interference of electron waves [12]. The unique electronic properties of semiconductors—materials that form the basis of technologies ranging from microprocessors and solar cells to advanced photocatalytic systems—stem directly from their specific band structure characteristics [12] [13].

At the heart of this theory lies the concept of the bandgap, an energy region between the highest occupied energy band (valence band) and the lowest unoccupied energy band (conduction band) where electrons cannot exist [11]. This forbidden gap fundamentally determines a material's electrical conductivity and optical properties, enabling the sophisticated manipulation of electronic behavior that underpins contemporary semiconductor technology [14]. The precise understanding and engineering of this band structure, particularly within the context of inorganic semiconductor photocatalysis, allows researchers to design materials with tailored properties for specific applications, including renewable energy production and environmental remediation [15] [13].

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Valence Band, Conduction Band, and Bandgap

In semiconductor physics, three fundamental concepts define a material's electronic characteristics:

Valence Band (VB): This represents the highest range of electron energies where electrons are present at absolute zero temperature, formed from the bonding orbitals between atoms [14]. The electrons in the valence band are responsible for chemical bonding and are typically stable under normal conditions, meaning they do not participate in electrical conduction.

Conduction Band (CB): This is the lowest range of electron energies where electrons can move freely throughout the material, enabling electrical conduction [14]. These delocalized electrons are no longer bound to individual atoms and can accelerate under an applied electric field.

Bandgap (E₉): This critical parameter represents the energy difference between the top of the valence band (Valence Band Maximum, VBM) and the bottom of the conduction band (Conduction Band Minimum, CBM) [12]. The bandgap magnitude determines how easily electrons can be excited from the valence to the conduction band, thereby defining the material's fundamental electrical and optical properties.

Table 1: Classification of Solids Based on Band Structure

| Material Type | Bandgap Characteristics | Electrical Conductivity | Example Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductor | No bandgap; valence and conduction bands overlap | Very high | Metals (Al, Cu, Ag) |

| Semiconductor | Moderate bandgap (typically 0.1-3.0 eV) | Tunable from low to moderate | Si (1.12 eV), GaAs (1.42 eV) |

| Insulator | Large bandgap (>3.0 eV) | Very low | Diamond (5.5 eV), SiO₂ (9 eV) |

Formation of Energy Bands

The formation of energy bands in semiconductors can be understood through quantum mechanical principles. When isolated atoms with discrete electronic energy levels approach each other to form a crystalline lattice, their atomic orbitals begin to overlap [11]. According to the Pauli exclusion principle, no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state, causing originally degenerate atomic energy levels to split into closely spaced levels [12]. With a macroscopic number of atoms (~10²² atoms/cm³) in a crystal, these split levels merge into continuous energy bands separated by forbidden regions where electrons cannot exist [12] [11].

The behavior of electrons in these periodic structures is described by Bloch's theorem, which states that electron wavefunctions in a crystal can be represented as plane waves modulated by periodic functions with the same periodicity as the crystal lattice [11]. This periodicity allows scientists to represent the electronic band structure in momentum space (k-space), where the relationship between electron energy and crystal momentum is visualized along high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone (typically denoted as Γ, X, L, K, W) [12].

Band Theory in Photocatalysis Principles

Photocatalytic Mechanism and Band Structure

In photocatalytic applications, semiconductors function by absorbing photons with energy equal to or greater than their bandgap, promoting electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, thus creating electron-hole pairs [13]. These photogenerated charge carriers then migrate to the semiconductor surface where they participate in reduction and oxidation reactions with adsorbed species [16].

The overall photocatalytic process involves three fundamental steps:

- Photon Absorption: Semiconductor absorbs light, generating electron-hole pairs if photon energy (hν) ≥ E₉ [13]

- Charge Separation and Migration: Photogenerated electrons and holes separate and move to the catalyst surface [13]

- Surface Reactions: Electrons and holes drive reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively [13]

For water splitting—a key reaction in renewable hydrogen production—the semiconductor band structure must satisfy specific energy requirements. The conduction band minimum must be more negative than the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) potential (0 V vs. NHE at pH 0), while the valence band maximum must be more positive than the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) potential (1.23 V vs. NHE) [13]. This creates a minimum theoretical bandgap requirement of 1.23 eV, though practical materials require larger bandgaps to overcome overpotentials and kinetic barriers.

Advanced Band Structure Considerations

Several sophisticated aspects of band structure critically influence photocatalytic efficiency:

Direct vs. Indirect Bandgaps: In direct bandgap semiconductors (e.g., GaAs), the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum occur at the same crystal momentum value (k-vector), enabling efficient photon absorption and emission without momentum transfer [12]. In contrast, indirect bandgap semiconductors (e.g., Si) have VBM and CBM at different k-points, requiring phonon (lattice vibration) participation to conserve momentum during electronic transitions [12]. This makes indirect transitions less probable and reduces their optical efficiency, though both material types find applications in photocatalysis.

Band Alignment in Heterostructures: Combining different semiconductors creates heterojunctions where band alignment (type-I, type-II, or Z-scheme) determines charge separation efficiency [13]. For instance, a type-II staggered alignment facilitates spatial separation of electrons and holes across the interface, reducing recombination losses and enhancing photocatalytic activity [13] [16].

Doping Effects on Band Structure: Intentional introduction of impurities can significantly modify band structures. As demonstrated in SrZrO₃ doping studies, incorporating germanium (Ge) atoms at zirconium (Zr) sites progressively reduces the bandgap from 3.72 eV to 1.20 eV, extending light absorption into the visible spectrum [15]. This bandgap engineering enables more efficient utilization of solar energy.

Table 2: Bandgap Modification in Doped SrZrO₃ Perovskites [15]

| Material Composition | Bandgap (eV) | Photocatalytic Activity | Semiconductor Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| SrZrO₃ | 3.72 | Baseline (UV-active) | p-type |

| SrZr₀.₉₆Ge₀.₀₄O₃ | 2.43 | Moderate enhancement | p-type |

| SrZr₀.₉₂Ge₀.₀₈O₃ | 2.18 | Significant enhancement | p-type |

| SrZr₀.₈₈Ge₀.₁₂O₃ | 1.20 | Maximum enhancement | p-type |

Computational and Experimental Methods

First-Principles Computational Approaches

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the most powerful and widely used computational tool for investigating electronic band structures from first principles [12]. DFT calculations enable researchers to predict material properties based solely on fundamental physical constants and atomic compositions, without empirical parameters.

The standard DFT workflow for band structure analysis includes:

- Structure Optimization: Geometric relaxation of atomic positions and lattice constants to find the ground-state configuration [12]

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: Determination of the ground-state charge density and total energy [12]

- Non-SCF Band Structure Calculation: Computation of electronic eigenvalues along high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin zone [12]

However, traditional DFT implementations using Local Density Approximation (LDA) or Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functionals systematically underestimate bandgaps by 50-80% compared to experimental values—a limitation known as the "bandgap problem" [12]. For instance, standard GGA calculations for silicon yield a bandgap of approximately 0.6 eV, significantly lower than the experimental value of 1.12 eV [12]. This error stems from DFT's formulation for ground-state properties, while the bandgap is fundamentally an excited-state property.

Advanced computational approaches have been developed to address these limitations:

- Hybrid Functionals (HSE06): Incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange energy, significantly improving bandgap accuracy with reasonable computational cost [12]

- GW Approximation: A many-body perturbation theory method that provides highly accurate quasiparticle bandgaps but requires substantial computational resources [12]

- DFT+U: Adds an effective Hubbard U parameter to correct for strong electron correlations in localized d or f orbitals [12]

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Experimental validation of computational predictions employs several sophisticated spectroscopic methods:

UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Measures the absorption spectrum to determine the optical bandgap through Tauc plot analysis [13]. This technique distinguishes between direct and indirect bandgaps based on the relationship between absorption coefficient and photon energy.

Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Detects light emission from electron-hole recombination, providing information about bandgap energy and defect states [17]. Advanced temperature-dependent and power-dependent PL studies can reveal complex phenomena like bandgap renormalization effects in perovskite materials [17].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Determines absolute binding energies of electronic states and band alignment at heterojunctions [11]. For example, XPS measurements of ZnO/Si heterostructures precisely quantified valence band offsets (ΔEᵥ) and conduction band offsets (ΔE𝒸), confirming type-II band alignment [11].

Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy (ARPES): Directly maps the electronic band structure in momentum space [11]. Recent advancements enabled spin-resolved ARPES measurements that revealed spin-split bands in antiferromagnetic MnTe₂, opening possibilities for spintronic applications [11].

Current Research and Applications

Bandgap Engineering for Enhanced Photocatalysis

Recent research has focused extensively on bandgap engineering strategies to develop more efficient photocatalytic materials:

Doping and Alloying: As demonstrated in SrZrO₃ perovskites, strategic doping with germanium atoms progressively reduces the bandgap while maintaining the p-type semiconductor character, creating more holes in the valence band for hydroxyl free radical generation [15]. The sharp peak in the valence band of all compositions indicates their p-type nature, beneficial for photocatalysis [15].

Perovskite Materials: Organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites represent a promising class of photovoltaic and photocatalytic materials due to their exceptional optoelectronic properties and structural tunability [17]. Unlike conventional semiconductors, perovskite bandgaps exhibit unusual temperature dependence attributed to static and dynamic lattice distortions in their soft crystal structures [17].

Nanostructuring and Low-Dimensional Materials: Reducing material dimensions to the nanoscale (1-100 nm) creates quantum confinement effects that increase bandgaps and enhance charge separation efficiency [16]. Two-dimensional materials like transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) and graphene facilitate shorter charge migration distances to active surfaces, reducing recombination losses [18].

Dual-Functional Photocatalysis

Advanced photocatalytic systems now enable simultaneous hydrogen production and pollutant degradation, creating synergistic environmental and energy benefits [16]. Nanostructured semiconductors demonstrate significantly enhanced performance in these dual-function applications due to their high surface-to-volume ratios, reduced electron-hole recombination rates, and greater pore volumes compared to bulk materials [16].

Table 3: Representative Photocatalytic Materials and Their Band Structures

| Material | Bandgap (eV) | Band Edge Positions | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | 3.0-3.2 | Suitable for OER, limited HER without sensitization | UV-driven photocatalysis, self-cleaning surfaces |

| SrZrO₃ | 3.72 (pristine) | Favorable for overall water splitting | Hydrogen production, environmental remediation |

| CdS | ~2.4 | CB more negative than H⁺/H₂ | Visible-light H₂ production, CO₂ reduction |

| g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 | Appropriate for OER, moderate HER potential | Organic synthesis, pollutant degradation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials and Methods

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Band Structure Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Computational Codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | First-principles calculation of electronic band structures | Predicting bandgaps, density of states, and optical properties [12] |

| GGA/PBE Functional | Standard exchange-correlation functional for DFT calculations | Initial band structure screening; requires correction for accurate bandgaps [12] [15] |

| HSE06 Hybrid Functional | Advanced functional mixing exact Hartree-Fock exchange | Improved bandgap accuracy with reasonable computational cost [12] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Tunable porous semiconductor materials | Photocatalytic H₂ production, CO₂ reduction, pollutant degradation [16] |

| Perovskite Precursors (FAI, MABr, PbI₂) | Synthesis of hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites | Solar cells, light-emitting diodes, photocatalytic systems [17] |

| XPS Measurement System | Experimental determination of band alignment and chemical states | Quantifying band offsets in heterostructures, surface chemistry analysis [11] |

Semiconductor band theory provides the fundamental framework for understanding and manipulating the electronic properties of materials critical to photocatalysis and renewable energy technologies. The precise control of bandgap values through doping, nanostructuring, and heterojunction engineering has enabled significant advances in photocatalytic efficiency, particularly for solar-driven hydrogen production and environmental remediation.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more sophisticated multiscale computational methods that bridge quantum mechanical accuracy with device-level performance prediction, alongside advanced characterization techniques that probe band structure dynamics under operational conditions. The integration of machine learning approaches with high-throughput computational screening offers particular promise for accelerating the discovery of optimal photocatalytic materials with tailored band structures for specific applications.

As the field progresses, a deeper understanding of complex phenomena such as bandgap renormalization, spin-polarized band structures, and dynamic lattice effects will further enhance our ability to design next-generation photocatalytic systems that efficiently harness solar energy for sustainable chemical transformations.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive breakdown of the fundamental mechanisms underlying heterogeneous photocatalysis with inorganic semiconductors. Framed within broader thesis research on reaction principles, this whitepsper systematically details the sequential processes from initial photon absorption to subsequent surface redox reactions. We examine the critical parameters governing each step, present quantitative data on representative photocatalyst systems, outline essential experimental methodologies, and visualize key mechanistic pathways. The information presented herein aims to equip researchers and scientists with a foundational understanding of photocatalytic principles relevant to energy and environmental applications, including solar fuel production and environmental remediation.

Heterogeneous photocatalysis represents a multidisciplinary field centered on utilizing photon energy to drive chemical reactions using semiconductor materials. This process mimics natural photosynthesis by converting solar energy into chemical energy [4]. The foundational discovery, often termed the Honda-Fujishima effect, was demonstrated in 1972 with the photoelectrochemical water splitting using a titanium dioxide (TiO₂) electrode [19] [20]. This discovery sparked extensive research into semiconductor photocatalysts for various applications, including hydrogen production via water splitting, carbon dioxide reduction, and pollutant degradation [4] [19] [5].

A photocatalytic reaction is initiated when a photoexcited electron is promoted from the filled valence band (VB) of a semiconductor photocatalyst to the empty conduction band (CB), provided the absorbed photon energy (hυ) equals or exceeds the semiconductor's band gap energy (Eg) [20]. This results in the formation of an electron-hole pair (e⁻–h⁺) [20]. The subsequent spatial separation and migration of these charge carriers to the semiconductor surface enables them to participate in reduction and oxidation reactions with adsorbed species, respectively [19]. The efficiency of the entire process depends on a delicate balance between the competing processes of charge carrier generation, separation, migration, and recombination [19] [21].

Step-by-Step Mechanistic Breakdown

Step 1: Photon Absorption and Electron-Hole Pair Generation

The photocatalytic process commences with the absorption of light. When a semiconductor photocatalyst is illuminated by light with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap energy, an electron (e⁻) in the valence band absorbs the photon's energy and is excited across the band gap to the conduction band [20]. This transition leaves behind a positively charged vacancy in the valence band, known as a hole (h⁺) [20]. The fundamental equation for this photoexcitation is:

Photoexcitation: Semiconductor (e⁻ in VB) + hυ ≥ E₉ → Semiconductor (e⁻ in CB + h⁺ in VB) Or, more simply: SC + hυ → e⁻CB + h⁺VB [20]

The ability of a photocatalyst to absorb light is primarily determined by its band gap energy, which defines the theoretical limit of its solar energy utilization efficiency [19]. Ultraviolet (UV) light constitutes only a minor fraction (~5%) of the total solar spectrum, making the development of visible-light-responsive photocatalysts a paramount importance for practical applications [19] [20].

Step 2: Charge Carrier Separation and Migration

Following photoexcitation, the spatially separated electron and hole must migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst to participate in chemical reactions. This step is critical as the photogenerated charge carriers are highly susceptible to recombination, a process where the electron falls back into the hole, releasing energy as heat or photons and thus becoming unavailable for catalysis [19] [20]. The following reactions describe charge carrier trapping and recombination:

Charge carrier trapping: e⁻CB → e⁻TR (Trapped electron) h⁺VB → h⁺TR (Trapped hole) [20]

Electron-hole recombination: e⁻TR + h⁺VB (or h⁺TR) → e⁻CB + heat [20]

Enhancing the efficiency of charge separation is crucial for the overall photocatalytic efficiency [19]. Strategies to improve this include coupling with other semiconductors to form heterojunctions, modifying crystal facets, and defect engineering [19] [21]. The lifetime of separated charge carriers is typically in the picosecond to nanosecond range, and their effective separation prolongs their availability for surface reactions [20].

Step 3: Surface Redox Reactions

The final stage involves the trapped electrons and holes reaching the catalyst surface and interacting with adsorbed species. The hole, a powerful oxidant, can directly oxidize an organic donor molecule (D) or react with water or hydroxide ions to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which are non-selective, potent oxidants [20]. Concurrently, the electron, a potent reductant, typically reduces molecular oxygen (O₂) adsorbed on the catalyst surface, forming superoxide radical anions (O₂•⁻) [4] [20]. These reactive oxygen species (ROS) are integral to oxidative degradation processes.

The primary surface reactions in an aqueous medium are outlined below [20]:

Oxidation Pathways:

- Direct oxidation: D + h⁺VB → D•⁺ (Oxidized donor)

- Hydroxyl radical generation: H₂O + h⁺VB → •OH + H⁺ or OH⁻ + h⁺VB → •OH

- Organic radical formation: R-H + •OH → R• + H₂O

Reduction Pathways:

- Oxygen reduction: O₂ + e⁻CB → O₂•⁻

- Protonation of superoxide: O₂•⁻ + H⁺ → HOO•

- Hydrogen peroxide formation: HOO• + e⁻CB → HOO⁻ followed by HOO⁻ + H⁺ → H₂O₂

These reactive intermediates (e.g., •OH, h⁺, O₂•⁻, HOO•) act concomitantly to oxidize a wide variety of organic pollutants [20]. For water splitting, the half-reactions are: the reduction of protons to H₂ by electrons and the oxidation of water to O₂ by holes [19].

Quantitative Data for Representative Photocatalysts

The photocatalytic activity of a material is intrinsically linked to its electronic structure. The band gap energy determines the range of light absorption, while the relative positions of the valence and conduction bands dictate the thermodynamic feasibility of various redox reactions.

Table 1: Band Gap and Characteristics of Common Inorganic Semiconductor Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Band Gap (eV) | Primary Light Absorption Range | Key Applications | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ (Rutile/Anatase) | ~3.0 - 3.2 eV [20] | Ultraviolet (UV) | Water splitting [19], pollutant degradation [20] [5] | Widely studied; requires UV activation. |

| ZnO | ~3.2 eV [4] | Ultraviolet (UV) | Organic synthesis [5], water treatment [5] | Similar bandgap to TiO₂. |

| WO₃ | ~2.6 - 2.8 eV [4] | Visible Light | Oxidation reactions [4] | Visible-light-responsive. |

| CdS | ~2.4 eV [4] | Visible Light | Hydrogen evolution [4] | Good visible light absorption but suffers from photocorrosion. |

| g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 eV [21] | Visible Light (~450 nm) [21] | Water splitting [21], CO₂ reduction [21] | Metal-free, organic semiconductor. |

| NaTaO₃ | ~4.0 eV [19] | Ultraviolet (UV) | Water splitting [19] | High crystallinity and surface nanostructure enhance activity. |

Table 2: Key Reactive Species in Photocatalytic Processes and Their Roles

| Reactive Species | Formation Pathway | Primary Role in Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Photogenerated Hole (h⁺) | Direct product of photoexcitation [20]. | Powerful oxidant; can directly oxidize pollutants or generate •OH from H₂O/OH⁻ [20]. |

| Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) | H₂O/OH⁻ + h⁺VB → •OH + H⁺ [20]. | Highly potent, non-selective oxidant for degrading organic contaminants [20] [5]. |

| Superoxide Anion (O₂•⁻) | O₂ (ads) + e⁻CB → O₂•⁻ [20]. | A reductant and oxidant; leads to formation of H₂O₂ and other ROS [20]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | HOO• + e⁻CB → HOO⁻; HOO⁻ + H⁺ → H₂O₂ [20]. | Can be photolyzed to form more •OH radicals [4]. |

Essential Experimental Methodologies

Protocol for Evaluating Photocatalytic Activity for Pollutant Degradation

A standard experimental setup for assessing photocatalytic degradation of pollutants in aqueous solution involves the following steps [20] [5]:

- Reactor Setup: A common configuration is a slurry batch reactor, typically a Pyrex glass vessel, equipped with a magnetic stirrer to keep the photocatalyst particles in suspension. The light source (e.g., Xenon lamp with appropriate filters to simulate solar spectrum or select specific wavelengths) is positioned at a fixed distance from the reactor.

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: A known volume (e.g., 100-200 mL) of the pollutant solution at a specific initial concentration (e.g., 10-50 mg/L) is added to the reactor. A precisely weighed amount of the photocatalyst powder (e.g., 0.5 - 1.0 g/L) is added to the solution.

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Before illumination, the suspension is stirred in the dark for a predetermined period (typically 30-60 minutes) to establish an adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the pollutant and the photocatalyst surface. This step is crucial for obtaining an accurate baseline.

- Illigation and Sampling: The light source is turned on, marking time zero (t = 0). At regular time intervals (e.g., every 15-30 minutes), small aliquots (e.g., 3-5 mL) of the suspension are withdrawn from the reactor.

- Sample Analysis: The withdrawn samples are centrifuged or filtered through a membrane (e.g., 0.22 or 0.45 µm) to remove the photocatalyst particles. The clear filtrate is then analyzed to determine the residual concentration of the pollutant. Common analytical techniques include:

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometry: Monitoring the decrease in the characteristic absorption peak of the pollutant.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): For more precise quantification and to track the formation of intermediate products.

- Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Analysis: To measure the degree of mineralization (conversion of organic carbon to CO₂).

The degradation efficiency can be calculated as: Efficiency (%) = [(C₀ - Cₜ) / C₀] × 100, where C₀ is the initial concentration after the dark adsorption period and Cₜ is the concentration at time t.

Protocol for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution via Water Splitting

The experimental setup for measuring photocatalytic water splitting activity, particularly for H₂ evolution, requires an airtight system and often the use of a sacrificial agent [19].

- Reactor Setup: A top-irradiation or side-irradiation reaction vessel made of quartz or Pyrex is connected to a closed gas circulation system. The system is thoroughly evacuated to remove air before the reaction.

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: The photocatalyst powder (e.g., 50-100 mg) is dispersed in an aqueous solution (e.g., 100-200 mL). To consume the photogenerated holes and thereby suppress electron-hole recombination, a sacrificial reagent is typically added. Common sacrificial reagents for H₂ evolution include methanol, lactic acid, or triethanolamine (typically 10-20 vol%).

- Co-catalyst Loading: To enhance H₂ evolution kinetics, a co-catalyst (e.g., Pt, Au, Ni) is often photodeposited or impregnated onto the photocatalyst surface. Pt is a common choice due to its low overpotential for proton reduction.

- Reaction and Analysis: The reaction mixture is sealed and evacuated. The light source is turned on to initiate the reaction. The reaction is usually maintained at constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) using a water-cooling jacket. The evolved gases (H₂ and, in overall water splitting, O₂) are periodically analyzed using gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a molecular sieve column.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in photocatalysis relies on a set of essential materials and reagents, each serving a specific function in the synthesis, characterization, and activity testing of photocatalysts.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Photocatalysis Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Core Photocatalysts | TiO₂ (P25 is a common benchmark), ZnO, WO₃, CdS, g-C₃N₄, novel perovskites [4] [19] [20]. | The active material that absorbs light and catalyzes the redox reaction. |

| Precursors for Synthesis | Metal alkoxides (e.g., Ti tetra-isopropoxide for TiO₂), metal salts (nitrates, chlorides), urea or melamine for g-C₃N₄ [20] [21]. | Used in the fabrication of semiconductor photocatalysts via sol-gel, precipitation, or thermal condensation methods. |

| Sacrificial Agents | Methanol, Triethanolamine, Lactic Acid, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) [19]. | Electron donors (for H₂ evolution) or acceptors (for O₂ evolution) that scavenge photogenerated holes or electrons to enhance charge separation. |

| Co-catalysts | Platinum (H₂PtCl₆), Gold, Nickel, Manganese Oxide (MnOx), Cobalt Oxide (CoOx) [19] [21]. | Nanoparticles deposited on the photocatalyst surface to provide active sites and lower the overpotential for H₂ evolution or O₂ evolution reactions. |

| Target Reactants | Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B, Phenol, 4-Chlorophenol, Methylene Blue (for degradation) [20] [5]. H₂O (with sacrificial agents or for overall splitting) [19]. | Model compounds used to quantitatively evaluate the photocatalytic activity and efficiency. |

| Analytical Standards & Reagents | Certified gas standards (H₂ in N₂, O₂ in N₂, CO₂), pure solvents for HPLC (Acetonitrile, Water), TOC calibration standards. | Used for calibration and quantitative analysis of reaction products and remaining reactants via GC, HPLC, and TOC analyzers. |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals derived from molecular oxygen, playing dual roles as both destructive agents in oxidative stress and constructive signaling molecules in physiological processes [22] [23]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core ROS—hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hydrogen peroxide—within the context of inorganic semiconductor photocatalysis reaction principles. We summarize their distinct chemical properties, biological functions, and generation mechanisms, with particular emphasis on photocatalytic ROS production pathways relevant to environmental remediation and therapeutic applications. The document includes standardized experimental protocols for ROS detection, detailed reagent solutions, and visualization of key reaction mechanisms to support research and development efforts in semiconductor photocatalysis and pharmaceutical development.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) encompass a range of molecules with oxidizing properties, including free radicals like superoxide (O₂•⁻) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), as well as non-radical species such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [23] [24]. These compounds are intrinsic to cellular functioning, present at low and stationary levels in normal cells where they participate in essential signaling and homeostasis [23]. The "oxygen paradox" describes the fundamental challenge aerobic organisms face: while oxygen is indispensable for life, it also generates dangerous by-products through its metabolic reduction [22].

In semiconductor photocatalysis, ROS generation represents a crucial mechanism for driving redox reactions aimed at environmental remediation and energy production [4]. When photocatalysts such as TiO₂, ZnO, or CdS absorb photons with energy equal to or greater than their bandgap energy, electrons are excited from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron-hole pairs [4]. These photogenerated charge carriers can then react with surface-adsorbed H₂O, O₂, and OH⁻ to yield various ROS species, which subsequently participate in oxidative degradation of organic pollutants [4]. Understanding the specific roles, reactivity, and detection methods for each major ROS is thus fundamental to advancing photocatalytic research and applications.

Characterization of Key ROS Species

Chemical Properties and Comparative Analysis

The three primary ROS species exhibit distinct chemical behaviors that dictate their biological and photocatalytic roles. Table 1 summarizes their fundamental properties.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Key Reactive Oxygen Species

| Property | Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) | Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | HO• | O₂•⁻ | H₂O₂ |

| Molecular Weight (g·mol⁻¹) | 17.007 [25] | 31.998 [26] | 34.014 [27] |

| Nature | Free Radical | Free Radical | Non-radical Oxidant |

| Reactivity | Extremely high (reacts at diffusion-limited rates) [28] | Moderate (can act as both oxidant and reductant) [29] | Relatively low (requires activation) [23] |

| Half-Life | ~10⁻⁹ seconds [25] [28] | Seconds to minutes (depending on environment) | Relatively stable |

| Membrane Permeability | Limited (highly reactive) | Poor (charged species) [22] | Good (diffuses through aquaporins) [24] |

| Primary Detection Methods | Spin trapping + EPR, fluorescence probes [26] | Cytochrome c reduction, NBT test, chemiluminescence [29] | Fluorometric assays, peroxidase-based methods [27] |

Individual ROS Profiles

Hydroxyl Radical (•OH)

The hydroxyl radical is the most reactive and chemically aggressive ROS, with an oxidation potential of 2.8 eV [28]. It is the neutral form of the hydroxide ion and contains an unpaired electron [25]. Its extreme reactivity leads to a half-life of approximately 10⁻⁹ seconds, during which it can damage virtually all types of macromolecules: carbohydrates, nucleic acids (causing mutations), lipids (initiating lipid peroxidation), and amino acids [25] [28]. Unlike superoxide, hydroxyl radicals cannot be eliminated by specific enzymatic reactions, making them particularly dangerous to biological systems [25] [28]. In photocatalytic systems, •OH represents the primary oxidative species responsible for non-selective degradation of organic pollutants [4].

Superoxide (O₂•⁻)

Superoxide anion represents the first intermediate in the stepwise reduction of molecular oxygen to water [26]. It is formed by the monovalent reduction of oxygen and can act as both an oxidant and a reductant in biological systems [29]. Although less reactive than •OH, superoxide serves as a precursor to more damaging ROS species through secondary reactions [22]. It does not easily cross cellular membranes due to its charge, making its actions more localized [22]. In phagocytic cells, superoxide production via NADPH oxidase constitutes a crucial defense mechanism against pathogens [29]. In photocatalytic contexts, superoxide forms when photogenerated electrons reduce molecular oxygen at the semiconductor surface [4].

Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂)

Hydrogen peroxide is the simplest peroxide, featuring an oxygen-oxygen single bond [27]. It is more stable than radical ROS species but can be activated to form hydroxyl radicals via Fenton or Haber-Weiss reactions in the presence of transition metals [28] [24]. H₂O₂ is membrane-permeable and can diffuse across biological membranes through aquaporin channels [24]. At low concentrations, it functions as an important signaling molecule in physiological processes; at high concentrations, it becomes toxic to cells [23] [24]. In photocatalysis, H₂O₂ forms both through the disproportionation of superoxide and the direct two-electron reduction of oxygen [4].

ROS Generation Pathways in Photocatalysis

Fundamental Photocatalytic Mechanisms

In semiconductor photocatalysis, ROS generation follows a well-defined sequence of events initiated by photon absorption. Figure 1 illustrates the primary reaction pathways in a heterogeneous photocatalytic system.

Figure 1: Primary ROS Generation Pathways in Semiconductor Photocatalysis

The photocatalytic process begins when a semiconductor absorbs a photon with energy (hν) equal to or greater than its bandgap energy (E_g), promoting an electron from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), thus creating an electron-hole pair (e⁻ CB/h⁺ VB) [4]:

The photogenerated charge carriers then migrate to the catalyst surface where they participate in redox reactions with adsorbed species. The hole (h⁺ VB) possesses strong oxidizing power and can directly oxidize organic compounds or react with water/hydroxyl ions to produce hydroxyl radicals [4]:

Meanwhile, the excited electron (e⁻ CB) can reduce molecular oxygen to superoxide [4]:

Superoxide subsequently undergoes disproportionation to form hydrogen peroxide [4]:

Hydrogen peroxide can then be reduced to hydroxyl radicals through photolytic or catalytic pathways [4]:

Secondary Reaction Pathways

Several secondary reactions contribute to ROS generation and interconversion in photocatalytic systems. The Haber-Weiss reaction and Fenton chemistry play particularly important roles in •OH production:

Haber-Weiss Reaction:

Fenton Reaction:

In semiconductor systems, transition metal impurities or intentionally incorporated dopants can catalyze Fenton-like reactions, enhancing •OH production and overall photocatalytic efficiency [28] [24].

Experimental Protocols for ROS Detection

Hydroxyl Radical Detection

Fluorescence Probe Method

Principle: Hydroxyl radicals react with non-fluorescent compounds to form highly fluorescent products. Common probes include terephthalic acid, which reacts with •OH to form 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid.

Procedure:

- Prepare 0.2 mM terephthalic acid solution in alkaline condition (pH ~10)

- Add the solution to your photocatalytic system

- Illuminate the system with appropriate light source

- Collect aliquots at regular time intervals

- Measure fluorescence intensity at excitation 315 nm / emission 425 nm

- Quantify •OH concentration using a calibration curve with standard 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid solutions

Applications: Suitable for quantifying •OH generation in aqueous photocatalytic systems; can be adapted for time-resolved measurements [28].

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) with Spin Trapping

Principle: Short-lived •OH radicals are trapped by spin traps (e.g., DMPO) forming stable adducts detectable by EPR spectroscopy.

Procedure:

- Prepare 100 mM spin trap solution (e.g., DMPO) in appropriate solvent

- Add to photocatalytic system ensuring anaerobic conditions when necessary

- After irradiation, transfer sample to flat cell for EPR measurement

- Record spectrum using typical parameters: modulation frequency 100 kHz, modulation amplitude 1 G, microwave power 20 mW

- Identify DMPO-OH adduct with characteristic 1:2:2:1 quartet signal (aN = aH = 14.9 G)

Applications: Direct detection and identification of free radical species; provides structural information about radical adducts [26].

Superoxide Detection

Nitroblue Tetrazolium (NBT) Reduction Assay

Principle: NBT is reduced by O₂•⁻ to form blue formazan precipitate, providing visible color change.

Procedure:

- Prepare 0.5 mM NBT solution in appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer pH 7.4)

- Add to photocatalytic system

- Illuminate with appropriate light source

- Monitor absorbance at 560 nm over time

- Calculate superoxide concentration using extinction coefficient ε = 28,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹

Applications: Simple, cost-effective method for quantifying superoxide production; suitable for initial screening of photocatalytic activity [29].

Cytochrome c Reduction Assay

Principle: Superoxide reduces ferricytochrome c to ferrocytochrome c, producing measurable absorbance change.

Procedure:

- Prepare 50 μM cytochrome c solution in appropriate buffer

- Add to photocatalytic system

- Illuminate with appropriate light source

- Monitor absorbance at 550 nm over time

- Calculate superoxide concentration using Δε550 = 21,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹

- Include controls with superoxide dismutase to confirm specificity

Applications: Specific detection of superoxide in biological and photocatalytic systems; well-established quantitative method [29].

Hydrogen Peroxide Detection

Fluorometric Assay Using Peroxidase

Principle: Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) catalyzes H₂O₂-mediated oxidation of non-fluorescent substrates to fluorescent products.

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing 10 U/mL HRP and 50 μM Amplex Red reagent in appropriate buffer

- Add to samples containing H₂O₂

- Incubate in dark for 30 minutes at room temperature

- Measure fluorescence at excitation 560 nm / emission 590 nm

- Quantify H₂O₂ concentration using standard calibration curve

Applications: Highly sensitive detection of H₂O₂ in complex mixtures; suitable for both biological and photocatalytic systems [27] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2 compiles key reagents and materials essential for ROS research in photocatalytic and biological contexts.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ROS Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Terephthalic Acid | Fluorescent probe for •OH detection | Forms 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid with •OH; excitation/emission at 315/425 nm [28] |

| DMPO (5,5-Dimethyl-1-Pyrroline N-Oxide) | Spin trap for EPR spectroscopy | Forms stable radical adducts with •OH and O₂•⁻; characteristic EPR spectra [26] |

| Nitroblue Tetrazolium (NBT) | Colorimetric superoxide detection | Reduced by O₂•⁻ to purple formazan; absorbance at 560 nm [29] |

| Cytochrome c | Superoxide detection | Reduction measurable at 550 nm; specific for O₂•⁻ [29] |

| Amplex Red | Fluorometric H₂O₂ detection | HRP-coupled assay; excitation/emission at 560/590 nm [27] |

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | Specific O₂•⁻ scavenger | Enzyme that catalyzes O₂•⁻ dismutation to H₂O₂; used in control experiments [29] [26] |

| Catalase | H₂O₂ decomposition enzyme | Specific H₂O₂ scavenger; used to confirm H₂O₂ involvement [24] |

| Mannitol | •OH scavenger | Sugar alcohol that reacts with hydroxyl radicals; scavenging control [25] |

| TiO₂ Nanoparticles | Benchmark photocatalyst | Wide bandgap semiconductor (3.2 eV); UV-activated ROS generation [4] |

Hydroxyl radicals, superoxide, and hydrogen peroxide represent the core reactive oxygen species in both biological systems and semiconductor photocatalysis applications. Their distinct chemical properties, generation pathways, and detection methodologies require specialized experimental approaches. The protocols and reagents detailed in this technical guide provide a foundation for rigorous investigation of ROS in photocatalytic research. Understanding the nuanced roles and behaviors of these species is essential for advancing applications in environmental remediation, energy conversion, and therapeutic development. Future research directions should focus on developing more selective and sensitive detection methods, particularly for real-time monitoring of ROS dynamics in complex systems, and designing photocatalysts with enhanced ROS generation efficiency and specificity.

Inorganic semiconductor photocatalysis has emerged as a cornerstone technology for addressing global challenges in renewable energy and environmental remediation. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of four fundamental material classes—metal oxides, sulfides, phosphides, and carbon-based semiconductors—that are driving innovations in photocatalytic applications. The principles governing these materials, including their electronic structure, charge carrier dynamics, and surface properties, form the critical foundation for developing efficient photocatalytic systems for hydrogen production, CO₂ reduction, and organic pollutant degradation. Framed within broader research on inorganic semiconductor reaction principles, this guide examines the intrinsic and extrinsic parameters that dictate photocatalytic performance, offering researchers and drug development professionals a systematic framework for material selection and optimization in advanced catalytic applications.

Fundamental Principles of Semiconductor Photocatalysis

Photocatalytic Mechanism

Semiconductor photocatalysis operates on the principle of photoexcitation where absorption of photons with energy equal to or greater than the material's bandgap energy (E_g) promotes electrons (e⁻) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), simultaneously generating holes (h⁺) in the VB [30] [31]. This process creates electron-hole pairs that migrate to the semiconductor surface to drive reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively. The resulting charge carriers can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radicals (•O₂⁻), which possess strong oxidative capabilities for degrading organic pollutants [32] [33].

The overall photocatalytic efficiency depends on three sequential steps: (1) photon absorption and exciton generation, (2) charge carrier separation and migration to surface active sites, and (3) surface redox reactions with adsorbed species [34]. The quantum yield of photocatalytic reactions is often limited by the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, with time-resolved spectroscopic studies revealing that approximately 90% recombine rapidly after excitation [33].

Band Structure Engineering

The electronic band structure serves as the primary determinant of a semiconductor's photocatalytic capabilities. The bandgap energy dictates the spectral range of light absorption, while the relative positions of the valence and conduction bands govern the thermodynamic feasibility of redox reactions [30].

Table 1: Bandgap Energies and Applications of Semiconductor Classes

| Material Class | Representative Materials | Bandgap Range (eV) | Primary Light Absorption | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides | TiO₂, ZnO, WO₃, Fe₂O₃ | 2.1-3.6 | UV to Visible | Water treatment, H₂ production [30] [31] |

| Metal Sulfides | CdS, ZnS, CuS, ZnIn₂S₄ | 1.0-2.4 | Visible | H₂ production, CO₂ reduction [34] [35] |

| Metal Phosphides | CoP, Ni₂P, Cu₃P, WP | 1.0-2.0 | Visible | Cocatalysts for H₂ evolution [36] |

| Carbon-Based | g-C₃N₄, Graphene, Carbon dots | 1.6-2.7 | Visible | Pollutant degradation, H₂ production [32] |

For a photocatalytic reaction to proceed efficiently, the conduction band minimum must be more negative than the reduction potential of the target reaction, while the valence band maximum must be more positive than the oxidation potential [30]. Metal oxides typically exhibit wider bandgaps, limiting their activity to UV light, whereas metal sulfides possess narrower bandgaps with broader visible light absorption [34] [30]. The valence bands of most metal sulfides consist of S 3p orbitals, which are more negative than O 2p orbitals found in metal oxides, resulting in narrower bandgaps [34].

Figure 1: Fundamental Photocatalytic Mechanism in Semiconductors

Metal Oxide Semiconductors

Material Properties and Characteristics

Metal oxides represent the most extensively studied class of photocatalytic semiconductors, valued for their exceptional chemical stability, non-toxicity, and robust photocatalytic activity [33] [31]. Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) has emerged as the benchmark photocatalyst due to its high photoreactivity, cost-effectiveness, biological inertness, and photostability [33]. The electronic structure of metal oxides features a configuration where the valence band consists of O 2p orbitals, while the conduction band comprises metal d or sp orbitals [31]. These materials typically exhibit bandgap energies ranging from 2.1 eV (Fe₂O₃) to 3.6 eV (SnO₂), with TiO₂ positioned at approximately 3.2 eV, primarily absorbing in the UV region [30].

The photocatalytic activity of metal oxides originates from two primary sources: the generation of •OH radicals through oxidation of OH⁻ anions and the production of •O₂⁻ radicals via reduction of O₂ [30]. These radical species demonstrate remarkable effectiveness in degrading organic pollutants into less harmful byproducts, ideally mineralizing them to CO₂ and H₂O [33]. The surface morphology of metal oxides critically influences their photocatalytic performance, with nanoscale particles exhibiting enhanced activity due to quantum size effects that increase redox potential and improved charge carrier transport to the surface [30].

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Hydrothermal Synthesis of TiO₂ Nanoparticles:

- Precursor Preparation: Mix titanium alkoxide (e.g., titanium isopropoxide) with ethanol under vigorous stirring.

- Hydrolysis: Add the solution dropwise to deionized water maintained at pH 1-3 using nitric acid, resulting in the formation of a white precipitate.

- Aging: Transfer the suspension to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 200°C for 12-24 hours to promote crystallization.

- Washing and Drying: Centrifuge the resulting nanoparticles, wash repeatedly with ethanol and deionized water, and dry at 80°C for 12 hours.

- Calcination: Anneal the powder at 400-500°C for 2-4 hours to obtain the desired crystalline phase (typically anatase) [33] [31].

Sol-Gel Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve zinc acetate dihydrate in ethanol with continuous stirring at 60°C.

- Precipitation: Add a solution of sodium hydroxide in ethanol dropwise to initiate precipitation.

- Aging: Maintain the reaction mixture at 60°C for 2 hours with constant stirring to promote nanoparticle growth.

- Purification: Recover nanoparticles by centrifugation, wash with ethanol, and dry at 80°C.

- Thermal Treatment: Calcinate the powder at 300-400°C to enhance crystallinity [31].

Performance optimization for metal oxides typically involves morphological control to increase surface area, elemental doping to extend light absorption into the visible range, and heterojunction construction with other semiconductors to improve charge separation [30] [31].

Metal Sulfide Semiconductors

Material Properties and Characteristics

Metal sulfides have gained significant attention as visible-light-driven photocatalysts due to their narrow band gaps, exceptional light-harvesting capabilities, and abundant exposed active sites [34]. Representative materials include CdS (Eg ≈ 2.4 eV), ZnS, and complex quaternary sulfides such as Cu₂ZnSnS₄. The electronic structure of metal sulfides features a valence band composed of S 3p orbitals, which are much more negative than O 2p orbitals in metal oxides, resulting in narrower band gaps and broader visible light absorption [34]. The conduction band contains d and sp metal orbitals, contributing to excellent electron mobility and reduction capability [34].

Despite their advantageous optical properties, metal sulfides suffer from limited photoelectrochemical stability due to light-induced photocorrosion, where photogenerated holes oxidize surface sulfide ions (S²⁻) to elemental sulfur (S⁰) or sulfate (SO₄²⁻) [34] [35]. This phenomenon severely hampers their practical implementation and has motivated extensive research into stabilization strategies. Survey data indicates a 4.1-fold increase in publications and a remarkable 171.6-fold increase in citations on metal sulfide photocatalysis from 2011 to 2020, underscoring the growing research interest in this material class [34].

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

CdS Nanoparticle Synthesis via Hydrothermal Method:

- Precursor Mixing: Dissolve Cd(NO₃)₂ and Na₂S in deionized water separately.

- Reaction: Slowly add the Na₂S solution to the Cd(NO₃)₂ solution with constant stirring, resulting in a yellow precipitate.

- Hydrothermal Treatment: Transfer the suspension to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 160-200°C for 12-24 hours.

- Product Recovery: Collect the resulting CdS nanoparticles by centrifugation, wash with ethanol and deionized water, and dry at 60°C under vacuum [34] [35].

Photodeposition of Cocatalysts on CdS:

- Suspension Preparation: Disperse CdS nanoparticles in an aqueous solution containing methanol (10-20 vol%) as a sacrificial electron donor.

- Cocatalyst Precursor Addition: Introduce H₂PtCl₆ solution (0.4 wt% Pt relative to CdS) to the suspension.

- Irradiation: Expose the system to visible light (λ ≥ 420 nm) for 1-2 hours with continuous stirring to facilitate Pt nanoparticle deposition.

- CrOx Shell Formation: Add K₂CrO₄ solution to the Pt/CdS suspension and continue irradiation to form a core-shell Pt@CrOx structure [35].

Anti-Photocorrosion Strategy - Oxide Coating: TiO₂ coating on CdS surfaces effectively suppresses photocorrosion by providing a physical barrier against sulfur oxidation while facilitating hole transfer for water oxidation. This is achieved through controlled hydrolysis of titanium precursors followed by calcination at moderate temperatures (300-400°C) [35].

Metal Phosphide Semiconductors

Material Properties and Characteristics

Transition metal phosphides (TMPs) have emerged as highly efficient cocatalysts for enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, offering advantages including low cost, abundant availability, high electrical conductivity, and favorable physical and chemical properties [36]. Common TMPs include CoP, Ni₂P, Cu₃P, WP, and MoP, which can be synthesized in various morphologies such as nanoparticles, nanosheets, nanorods, and hollow structures [36]. According to their chemical bond types, TMPs can be classified as ionic compounds, metal bond compounds, or covalent bond compounds, with stoichiometries ranging from M₃P to MP₃ [36].

The primary application of TMPs in photocatalysis involves serving as cocatalysts that enhance the apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) of hydrogen evolution reactions [36]. Their functions encompass multiple aspects: (1) improving light absorption capacity through plasmonic effects or sensitization; (2) providing abundant active sites for proton reduction; (3) facilitating charge transfer and separation through efficient electron extraction; (4) optimizing water activation by lowering the energy barrier for water dissociation; and (5) enhancing photostability by protecting the main photocatalyst from degradation [36]. Bimetallic phosphides such as cobalt-nickel phosphides have demonstrated superior performance due to their enhanced metallicity and dual active sites for HER [36].

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Solvothermal Synthesis of CoP Nanoparticles:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve cobalt acetate and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in a mixed solvent of oleylamine and octadecene.

- Phosphorization: Add tri-n-octylphosphine (TOP) as the phosphorus source to the solution under inert atmosphere.

- Reaction: Heat the mixture to 300-320°C and maintain for 2-4 hours to facilitate nanoparticle growth.

- Purification: Precipitate the CoP nanoparticles by adding ethanol, collect by centrifugation, and wash repeatedly with cyclohexane and ethanol [36].

Alternative Phosphidation Method Using NaH₂PO₂:

- Support Preparation: Disperse the primary semiconductor (e.g., CdS or g-C₃N₄) in ethanol.

- Impregnation: Add cobalt nitrate solution to the suspension and evaporate the solvent to achieve uniform metal precursor distribution.

- Phosphidation: Place the material together with NaH₂PO₂ in a tube furnace, with NaH₂PO₂ positioned upstream.

- Thermal Treatment: Heat at 300-400°C for 2 hours under N₂ flow to convert the metal precursor to phosphide [36].

Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Testing with TMP Cocatalysts:

- Reactor Setup: Combine TMP-modified photocatalyst (50 mg) with an aqueous solution (100 mL) containing sacrificial agents (e.g., 10 vol% triethanolamine or 0.1 M Na₂S/0.02 M Na₂SO₃).

- Deaeration: Purge the system with N₂ for 30 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Irradiation: Expose to simulated solar light (300 W Xe lamp with appropriate cutoff filters) with continuous stirring.

- Gas Analysis: Quantify evolved H₂ using gas chromatography with a thermal conductivity detector at regular intervals [36].

Carbon-Based Semiconductors

Material Properties and Characteristics

Carbon-based semiconductors encompass a diverse family of materials including graphene, carbon nanotubes, carbon dots, carbon fibers, graphyne, carbon aerogels, and fullerene [32]. These materials rarely function as standalone photocatalysts but instead serve as exceptional cocatalysts that enhance the performance of primary semiconductors through multiple mechanisms: (1) acting as multifunctional supports to enhance conductivity, adsorption, and catalytic performance; (2) serving as electron mediators to effectively separate electron-hole pairs; (3) functioning as photosensitizers to broaden the light absorption range; (4) providing stabilization to prevent aggregation and corrosion of semiconductors; and (5) forming semiconductor-carbon heterojunctions to facilitate charge separation [32].

Graphene possesses an extensive theoretical specific surface area of 2600 m²/g and a wide π-π conjugate structure that enhances pollutant adsorption and catalytic activity [32]. Carbon dots exhibit unique up-conversion photoluminescence properties, extending light absorption to near-infrared regions [32]. Graphyne, as an emerging carbon allotrope, demonstrates favorable electron-hole pair mobility and adjustable bandgap, showing significant potential in photoelectrocatalysis applications [32].

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Preparation of Graphene-Semiconductor Composites:

- Graphene Oxide Synthesis: Employ modified Hummers' method to oxidize graphite to graphene oxide (GO).

- Composite Formation: Dispense GO in water through ultrasonication, add semiconductor precursors (e.g., TiCl₄ for TiO₂), and adjust pH to facilitate deposition.

- Reduction: Hydrothermally treat the mixture at 120-180°C for 12-24 hours to simultaneously reduce GO to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and crystallize the semiconductor.

- Product Recovery: Collect the composite by filtration or centrifugation, wash thoroughly, and dry at 60°C [32].

Carbon Dot Synthesis via Hydrothermal Carbonization:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve carbon-rich precursors (e.g., citric acid) in deionized water.

- Hydrothermal Treatment: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 180-250°C for 4-12 hours.

- Purification: Dialyze the resulting solution against deionized water using a membrane (MWCO 1000 Da) to remove unreacted precursors.

- Composite Formation: Combine carbon dots with semiconductor precursors during material synthesis or through post-synthesis mixing [32].

Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation Experiments:

- Electrode Preparation: Deposit carbon-based semiconductor composites on conductive substrates (e.g., FTO glass) using drop-casting, spin-coating, or electrophoretic deposition.

- Reactor Setup: Configure a three-electrode system with the composite as photoanode, Pt wire as counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl as reference electrode in electrolyte containing target pollutants.

- Bias Application: Apply external bias (typically 0.5-1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl) using a potentiostat while irradiating with simulated solar light.

- Analysis: Monitor pollutant concentration decay using UV-vis spectroscopy or HPLC, and quantify mineralization through TOC measurements [32].

Comparative Analysis and Performance Metrics

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Semiconductor Classes in Photocatalytic Applications

| Material Class | H₂ Evolution Rate (μmol·h⁻¹·g⁻¹) | AQE (%) | Stability | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides | TiO₂: 10-100 (UV) | 1-10 (UV) | Excellent | Limited visible light absorption, recombination [33] |

| Metal Sulfides | CdS: 219-568 (visible) | 10.2@450nm | Moderate-Poor | Photocorrosion, toxicity concerns [34] [35] |

| Metal Phosphides | CoP/g-C₃N₄: Enhanced 5-10x | 15-20 | Good | Primarily cocatalysts, synthesis complexity [36] |

| Carbon-Based Composites | rGO/TiO₂: 2-5x improvement | 5-15 | Good-Excellent | Cost, complex fabrication [32] |

The performance metrics in Table 2 illustrate the trade-offs between activity, stability, and practical implementation across material classes. Metal sulfides demonstrate superior visible-light activity but suffer from stability issues, while metal oxides offer stability but limited visible light response. Metal phosphides excel as cocatalysts but rarely function as standalone photocatalysts. Carbon-based materials provide exceptional enhancement capabilities but involve more complex composite fabrication.

Figure 2: Advanced Z-Scheme Configuration for Efficient Water Splitting

Figure 2 illustrates a sophisticated Z-scheme system integrating n-type CdS and BiVO₄ with a [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/[Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻ mediator, achieving 10.2% apparent quantum yield at 450 nm with stoichiometric H₂/O₂ evolution [35]. This configuration demonstrates how material classes can be strategically combined to overcome individual limitations, with oxide coatings enhancing stability while maintaining high activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Photocatalysis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium Isopropoxide (TTIP) | TiO₂ precursor | Metal oxide synthesis | Hydrolysis sensitivity, requires anhydrous handling |

| Cadmium Nitrate Tetrahydrate | Cd²⁺ source for sulfide synthesis | Metal sulfide preparation | Toxicity, requires controlled disposal |

| Sodium Sulfide Nonahydrate | S²⁻ source for sulfide synthesis | Metal sulfide preparation | Moisture sensitivity, releases H₂S |

| Tri-n-octylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphorus source for phosphides | TMP synthesis | Air-sensitive, pyrophoric properties |

| NaH₂PO₂ | Alternative solid P source | Phosphidation processes | Requires inert atmosphere during thermal treatment |

| H₂PtCl₆•6H₂O | Pt precursor for cocatalysts | Noble metal deposition | Concentration controls nanoparticle size |

| K₂CrO₄ | CrOx shell precursor | Core-shell cocatalyst formation | Controls shell thickness and coverage |