Inorganic Photocatalysis: Mechanisms, Drug Discovery Applications, and Efficiency Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive overview of photocatalytic reactions involving inorganic compounds, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Inorganic Photocatalysis: Mechanisms, Drug Discovery Applications, and Efficiency Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of photocatalytic reactions involving inorganic compounds, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental photophysical mechanisms, including single-electron transfer and energy transfer processes, that underpin photocatalysis. The review details cutting-edge methodological applications in peptide functionalization, protein bioconjugation, and late-stage drug candidate functionalization. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for enhancing catalytic efficiency and stability, and presents rigorous validation and comparative techniques for assessing photocatalytic performance. By synthesizing foundational principles with advanced applications, this article serves as a strategic resource for leveraging inorganic photocatalysis in pharmaceutical research and development.

Unraveling the Core Principles: The Photophysical Mechanisms of Inorganic Photocatalysts

Fundamental Mechanisms of Photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is a process that combines light energy and a catalyst to accelerate chemical reactions. The term itself is composed of two parts: the prefix "photo," meaning light, and "catalysis," which is the process where a substance participates in modifying the rate of a chemical transformation without being ultimately altered [1]. More specifically, Fujishima et al. defined it as "the catalysis of a photochemical reaction over a solid surface" [1]. In practical terms, photocatalysis typically refers to the acceleration of a photoreaction by the presence of a catalyst, occurring at the interface between a catalyst and the reaction medium under irradiation with electromagnetic waves from the UV and visible spectrum [1].

The foundational interest in environmental photocatalysis began in 1972 with Fujishima and Honda's pioneering research on photoelectrochemical solar energy conversion, which involved oxidizing water and reducing carbon dioxide through a semiconductor irradiated by UV light [1]. This process mimics the natural principle of plant photosynthesis, aiming to replicate photo-induced redox reactions artificially.

The core mechanism involves a semiconductor photocatalyst with a band gap between 1.4 and 4.6 eV [1]. When this semiconductor absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap energy, electrons ((e^-)) are promoted from the filled valence band (VB) to the empty conduction band (CB), simultaneously generating positive holes ((h^+)) in the valence band [1]. This creates electron-hole pairs that can migrate to the catalyst surface and drive reduction and oxidation reactions with adsorbed molecules, generating reactive species that can undergo various chemical transformations.

Table 1: Common Semiconductor Photocatalysts and Their Properties [1]

| Photocatalyst | Band Gap Energy (eV) | Primary Absorption Range | Suitability for VOC Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | 3.2 | Near UV (~380 nm) | Suitable |

| ZnO | ~3.2 | Near UV | Information Missing |

| CdS | ~2.4 | Visible | Not Preferable |

| WO₃ | ~2.7 | Visible | Not Preferable |

| Fe₂O₃ | ~2.2 | Visible | Unsuitable |

| LiNbO₃ | 3.78 | UV | Information Missing |

Sequential Process of Photocatalytic Activation

The activation of a photocatalyst and subsequent reactions on its surface can be described by six key steps [1]:

- Photon Adsorption: The semiconductor absorbs photons with energy that matches or exceeds its band gap energy.

- Electron-Hole Pair Generation: Absorption of light promotes an electron ((e^-)) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), generating a hole ((h^+)) in the VB.

- Charge Carrier Migration: The photogenerated electrons and holes diffuse and migrate toward the surface of the semiconductor particle.

- Charge Carrier Recombination: Some electrons and holes recombine without participating in any chemical reaction, dissipating energy as heat, which is a key efficiency loss.

- Charge Carrier Trapping: Electrons and holes are stabilized at surface sites, forming trapped electrons and trapped holes, respectively, which enhances their chemical reactivity.

- Surface Redox Reactions: The trapped electrons reduce an electron acceptor (e.g., oxygen), and the trapped holes oxidize an electron donor (e.g., water or organic pollutants), generating reactive species.

Among these, the absorption of light (step 1) and the subsequent redox reactions at the surface (step 6) are the most critical processes in photocatalysis [1].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating a Doped Photocatalyst for Drug Degradation

This protocol details the fabrication of a nitrogen-doped TiO₂ (N-TiO₂) film and evaluation of its performance in the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical compounds like ciprofloxacin under visible light, based on a recent study [2].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Description | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Titania Precursor | Provides the titanium source for TiO₂ matrix formation. | Titanium isopropoxide or titanium tetrachloride. |

| Nitrogen Dopant Precursor | Introduces nitrogen atoms into the TiO₂ lattice to enhance visible light absorption. | Amine-based compounds (e.g., Urea). |

| Solvent | Medium for sol-gel reaction. | Ethanol or Methanol. |

| Pharmaceutical Pollutant | Model compound to assess photocatalytic degradation efficiency. | Ciprofloxacin solution in water (e.g., initial concentration ~10-20 mg/L). |

| Substrate for Immobilization | Support for the photocatalyst film enabling continuous flow operation. | Cylindrical quartz tube. |

| Acid or Base Catalyst | Catalyzes the hydrolysis and condensation reactions in the sol-gel process. | Hydrochloric acid (HCl) or Ammonia (NH₄OH). |

Methodology

- Sol Preparation: Prepare a TiO₂ sol-gel using a titanium precursor (e.g., titanium isopropoxide) in an alcoholic solvent (e.g., ethanol). Incorporate a controlled amount of a nitrogen precursor (e.g., urea) into the sol to achieve the desired doping level.

- Substrate Cleaning: Thoroughly clean the cylindrical quartz tube substrate with a detergent solution, followed by rinsing with deionized water and ethanol. Dry in an oven.

- Film Deposition: Immerse the quartz tube vertically into the prepared N-TiO₂ sol. Withdraw it at a controlled, uniform speed to ensure a homogeneous liquid film coats the entire surface.

- Gelation and Drying: Allow the deposited film to gel and dry at ambient conditions for a set period.

- Thermal Annealing: Transfer the coated tube to a furnace for thermal annealing. The typical protocol involves heating to 400-500°C for 1-2 hours in air. This step crystallizes the TiO₂ into the active anatase phase, removes organic residues, and ensures strong adhesion of the film to the quartz substrate.

Photocatalyst Characterization

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Determine the crystal phase (anatase, rutile) and crystallite size of the immobilized film.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Analyze the optical properties and confirm enhanced absorption in the visible light region due to nitrogen doping. Estimate the band gap energy using Tauc plots.

- X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Confirm the successful incorporation of nitrogen into the TiO₂ lattice and detail the elemental composition and electronic states on the surface.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Probe surface chemistry and functional groups.

Photocatalytic Performance Testing

- Reactor Setup: Place the N-TiO₂-coated quartz tube in a photoreactor system. Position a visible light source (e.g., LED lamp with λ > 400 nm) outside the tube.

- Reaction Procedure: Circulate an aqueous solution of ciprofloxacin through the coated tube in a continuous or recirculating mode.

- Sampling and Analysis: At regular time intervals, collect samples from the reservoir. Analyze the concentration of ciprofloxacin using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or by monitoring the absorbance decay via UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Control Experiment: Perform a control experiment under identical conditions but without light irradiation to account for any adsorption of the pollutant onto the catalyst surface.

Data Analysis and Performance Metrics

The degradation efficiency can be calculated using the formula: [ \text{Degradation Efficiency (\%)} = \frac{C0 - Ct}{C0} \times 100] Where (C0) is the initial concentration and (C_t) is the concentration at time (t).

The study employing this protocol reported a degradation efficiency of more than 85% for ciprofloxacin under visible light, attributed to effective nitrogen doping and robust film adhesion [2].

Table 3: Performance Data for Different Photocatalytic Reactions

| Photocatalytic System | Target Reaction | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-TiO₂ Film | Ciprofloxacin Degradation | Degradation Efficiency | > 85% | [2] |

| CdS-BaZrO₃ Heterojunction | Water Splitting (H₂ Production) | H₂ Production Rate | 44.77 μmol/h | [3] |

| Pt/cyano-COF | O₂ Reduction to H₂O₂ | H₂O₂ Production Rate | 903 ± 24 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ | [3] |

| N-TiO₂ (vs. P-25) | Formic Acid Degradation (UVA) | Quantum Efficiency | 3.5 (46% increase) | [3] |

Application in Drug Synthesis and Environmental Remediation

In the context of organic chemistry and drug development, photocatalysis has emerged as a powerful tool for synthesizing pharmacophores. It enables the formation of new carbon-carbon, carbon-nitrogen, or carbon-oxygen bonds under mild conditions [4]. Key transformations include the addition of aryl groups to heteroarenes, Michael-like additions, [3 + 2] cycloadditions, and the modification of benzylic compounds [4].

Concurrently, photocatalysis plays a vital role in environmental remediation within the pharmaceutical industry, particularly in treating wastewater contaminated with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), as demonstrated by the degradation of ciprofloxacin [2]. The scalability of immobilized catalyst systems, like the tubular N-TiO₂ reactor, offers a promising route for sustainable water treatment technologies, closing the loop between chemical synthesis and environmental responsibility in drug development.

The escalating global energy demand and persistent environmental pollution necessitate the development of sustainable technologies. Photocatalysis, which converts solar energy into chemical energy, has emerged as a pivotal solution for addressing these challenges. This article examines four key classes of inorganic photocatalysts—metal oxides, perovskites, polyoxometalates (POMs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)—within the context of advanced photocatalytic applications. These materials have garnered significant research attention due to their tunable electronic properties, structural diversity, and promising performance in energy conversion and environmental remediation processes.

The fundamental photocatalytic mechanism involves multiple sequential steps: light absorption, generation and migration of electron-hole pairs, and surface redox reactions. The efficiency of these processes depends critically on the photocatalyst's ability to absorb visible light, facilitate charge separation, and provide active sites for chemical transformations. Each class of photocatalyst offers distinct advantages and limitations in this context, which this review will explore through structured comparisons, experimental protocols, and performance analyses.

Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Fundamental Characteristics and Applications

Metal oxide nanoparticles represent one of the most extensively studied classes of inorganic photocatalysts. Titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), and iron oxide (Fe₃O₄) have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in photocatalytic applications due to their favorable band structures, stability, and tunable surface properties [5]. These semiconductors function by generating electron-hole pairs upon irradiation with light of sufficient energy, which subsequently initiate redox reactions at the catalyst surface.

The applications of metal oxide photocatalysts span environmental remediation and energy conversion. They have shown particular effectiveness in degrading synthetic dyes—complex organic compounds that pose significant environmental threats due to their persistence, toxicity, and widespread use in textile, leather, and furniture manufacturing [5]. The photocatalytic degradation process efficiently mineralizes these potentially carcinogenic substances into harmless byproducts, offering a sustainable water treatment technology.

Performance Optimization Strategies

A significant limitation of traditional metal oxide photocatalysts is their wide band gap, which restricts light absorption primarily to the ultraviolet spectrum. To enhance visible light absorption and overall photocatalytic efficiency, researchers have developed several optimization strategies:

Heterojunction Construction: Creating interfaces between different semiconductors (e.g., p-n junctions) facilitates charge separation through built-in electric fields, significantly reducing electron-hole recombination rates [6]. Transition metal oxide-based p-n heterojunctions have demonstrated improved performance in H₂ evolution, CO₂ reduction, overall water splitting, and photodegradation of pollutants.

Defect Engineering: Intentionally introducing controlled defects modifies the coordination microenvironment, tuning electronic structure parameters including d-band center, charge distribution, and spin moment [7]. This approach enhances light absorption and charge carrier dynamics.

Morphological Control: Synthesizing nanostructures with high surface-to-volume ratios increases the availability of active sites and improves mass transfer during photocatalytic reactions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Selected Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Application | Performance Metrics | Modification Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂-based | Dye degradation | >90% degradation of various synthetic dyes [5] | Heterojunction construction, defect engineering |

| ZnO nanoparticles | Environmental remediation | High adsorption and photocatalytic activity [5] | Morphological control, surface modification |

| Fe₃O₄ | Pollutant degradation | Magnetic separation capability [5] | Composite formation, hybridization |

Experimental Protocol: Photocatalytic Dye Degradation Using Metal Oxides

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: TiO₂ nanoparticles (Degussa P25 or synthesized)

- Target pollutant: Rhodamine B (RhB) or methylene blue solutions

- Light source: UV lamp (365 nm) or simulated solar light

- Reactor system: Batch photoreactor with magnetic stirring

Procedure:

- Prepare dye solution at specified concentration (typically 10-20 mg/L)

- Add photocatalyst to dye solution (typical loading: 0.5-1.0 g/L)

- Conduct adsorption-desorption equilibrium in dark conditions for 30 minutes

- Initiate irradiation while maintaining continuous stirring

- Collect samples at regular intervals and separate catalyst by centrifugation

- Analyze dye concentration using UV-Vis spectrophotometry

Key Parameters:

- pH adjustment critical for optimization

- Oxygen presence essential as electron scavenger

- Temperature control maintained at 25±2°C

Perovskite Photocatalysts

Structural Features and Photocatalytic Properties

Perovskite-type catalytic materials have emerged as promising alternatives to noble metal-based photocatalysts due to their structural adjustability and fascinating physicochemical properties [8]. These materials, typically with the general formula ABX₃, exhibit exceptional photoelectric characteristics including extended carrier lifetime, tunable band gaps, high absorption coefficients, and excellent charge carrier mobility.

The versatility of perovskite photocatalysts is evidenced by their application across diverse organic transformations, including C-H activation, coupling reactions, bond formation and cleavage, dehydrogenation, and ring-opening reactions [8]. Their capacity to function as single-electron redox mediators under visible light irradiation makes them particularly valuable for synthetic applications.

Application in Organic Synthesis: The Biginelli Reaction

A notable application of perovskite photocatalysts is in the visible-light-driven synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-(1H)-ones/thiones via the Biginelli reaction [9]. These heterocyclic compounds possess significant biological and pharmacological relevance, exhibiting calcium channel blocking, antihypertensive, anticancer, anti-HIV, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory activities.

CsPbBr₃ perovskites have demonstrated exceptional efficacy in this transformation, functioning as heterogeneous photocatalysts that offer simplified operation and recyclability. The photocatalytic system enables rapid reaction times (4-8 minutes) with excellent yields (86-94%) under ambient conditions using ethanol as a green solvent and blue LEDs as a renewable energy source [9].

Experimental Protocol: Biginelli Reaction Using CsPbBr₃ Perovskite

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: CsPbBr₃ perovskite (1 mol%)

- Substrates: Arylaldehyde derivatives (1.0 mmol), urea/thiourea (1.5 mmol), β-ketoesters (1.0 mmol)

- Solvent: Ethanol (3 mL)

- Light source: Blue LEDs (7 W)

- Reaction atmosphere: Air at room temperature

Procedure:

- Combine arylaldehyde, urea/thiourea, and β-ketoester in ethanol

- Add CsPbBr₃ photocatalyst (1 mol% loading)

- Stir reaction mixture at room temperature under blue LED illumination

- Monitor reaction progress by thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

- Upon completion, filter and wash catalyst with ethanol for recycling

- Purify crude product by crystallization from ethanol

Performance Characteristics:

- Broad functional group tolerance

- Catalyst recyclability (up to 6 cycles without significant activity loss)

- Gram-scale synthesis capability for industrial applications

- Average yield: 90.4% across diverse substrates

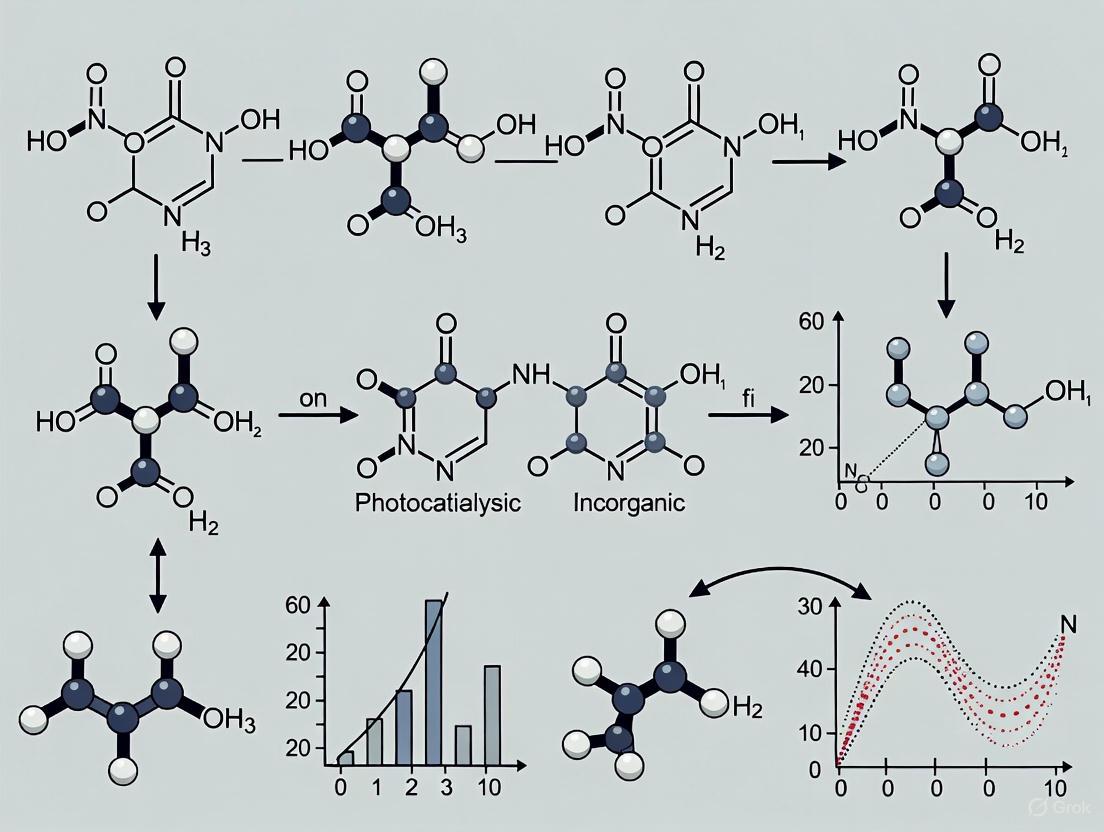

Diagram 1: Perovskite photocatalytic mechanism for Biginelli reaction showing single-electron transfer pathway

Polyoxometalate (POM) Photocatalysts

Structural Diversity and Functional Properties

Polyoxometalates represent a class of discrete metal-oxide clusters with unique photoelectric properties that make them promising candidates for photocatalytic applications [10]. These compounds typically comprise early transition metals (Mo, W, V, Nb, Ta) in their highest oxidation states, organized into diverse structural architectures including Keggin, Wells-Dawson, and wheel-type structures.

POMs exhibit semiconductor-like electronic structures with occupied valence bands and unoccupied conduction bands, enabling photocatalytic mechanisms similar to traditional semiconductors like TiO₂ [10]. Their exceptional redox properties, structural specificity, and tunable composition through heteroatom incorporation or organic functionalization provide unparalleled opportunities for photocatalytic system design.

Applications in Environmental Remediation and CO₂ Reduction

POM-based photocatalysts have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in degrading persistent organic pollutants, including dyes, pesticides, and pharmaceutical compounds [10]. The photocatalytic mechanism involves the generation of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydroxyl radicals (˙OH), which efficiently mineralize organic contaminants into harmless byproducts.

Recently, POMs have shown great potential for photocatalytic CO₂ reduction (PCR), converting this greenhouse gas into valuable chemicals and fuels (e.g., CO, CH₄, HCOOH, C₂H₄) while achieving carbon cycling and mitigating the greenhouse effect [11]. Their reversible multi-electron redox transitions while maintaining structural stability make POMs particularly suited for the multi-electron reduction processes required for CO₂ conversion.

Performance Enhancement Strategies

Transition Metal Substitution: Incorporating transition metal heteroatoms (e.g., Fe³⁺) into POM structures enhances visible light absorption through charge transfer transitions and provides additional catalytic centers [10]. For instance, PW₁₁O₃₉Fe³⁺(H₂O)⁴⁻ completely degrades Rhodamine B within 80 minutes under visible light irradiation.

Hybrid Material Construction: Combining POMs with complementary materials such as semiconductors, carbon nanomaterials, or metal nanoparticles creates synergistic effects that improve charge separation and light absorption.

Molecular Engineering: Designing large POM clusters with wheel-like or hollow spherical structures provides expansive anionic cavities that function as nanoreactors, enhancing substrate-catalyst interactions and catalytic efficiency.

Table 2: Representative POM Photocatalysts and Their Applications

| POM Catalyst | Application | Performance | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keggin-type POMs | Organic dye degradation | Complete RhB degradation in 80 min [10] | ROS generation, good stability |

| Transition metal-substituted POMs | Visible-light-driven photocatalysis | Enhanced visible light absorption [10] | Metal-centered redox activity |

| POM-based composites | CO₂ reduction | Conversion to CO, CH₄, etc. [11] | Multi-electron transfer, tunable band gaps |

Experimental Protocol: Photocatalytic Dye Degradation Using POMs

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: Transition metal-substituted POM (e.g., PW₁₁Fe)

- Target pollutant: Rhodamine B (RhB) solution (10 mg/L)

- Light source: Visible light (λ > 420 nm)

- Reaction vessel: Batch photoreactor with temperature control

Procedure:

- Prepare RhB solution at specified concentration

- Add POM catalyst (typical concentration: 0.1-0.5 g/L)

- Achieve adsorption-desorption equilibrium in dark for 30 minutes

- Initiate visible light irradiation with continuous stirring

- Withdraw samples at regular intervals

- Separate catalyst by centrifugation or filtration

- Analyze RhB concentration by UV-Vis spectroscopy at 554 nm

Mechanistic Insights:

- Hydroxyl radicals identified as primary reactive species

- Iron centers undergo reversible redox cycling (Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺)

- Oxygen acts as electron scavenger, generating H₂O₂ and O₂˙⁻

Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) Photocatalysts

Structural Advantages and Photocatalytic Mechanisms

Metal-organic frameworks represent an emerging class of porous coordination polymers that have garnered significant attention as visible-light-driven photocatalysts [12]. These crystalline materials, constructed from metal ions/clusters and multitopic organic linkers, offer exceptional structural tunability, high surface areas, and ordered porous architectures that facilitate reactant adsorption and mass transport.

MOFs exhibit unique photoactive behaviors characterized by the "antenna effect," where organic linkers harvest light energy and transfer it to metal cluster sites, enabling efficient light utilization [13]. This linker-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) process generates electron-hole pairs that drive photocatalytic reactions while minimizing recombination losses.

Applications in Energy and Environmental Domains

The versatility of MOF photocatalysts is evidenced by their application across diverse domains:

CO₂ Reduction: Since the pioneering 2012 report of NH₂-MIL-125(Ti) for visible-light-driven CO₂ reduction, MOF-based photocatalysts have flourished in this area [12]. Their tunable pore environments and chemical functionalities enable selective CO₂ adsorption and conversion to value-added products.

Hydrogen Production: MOFs demonstrate promising performance in photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen generation, offering a clean and renewable energy source [7]. Their structural designability allows for precise control of active sites and band gap engineering.

Organic Transformations: MOFs serve as efficient photocatalysts for various organic reactions, including selective oxidation, cross-coupling, and cyclization reactions [12]. Their single-site heterogeneity facilitates catalyst recovery and reuse.

Pollutant Degradation: MOFs effectively degrade organic pollutants in water and air through advanced oxidation processes, mineralizing contaminants into harmless substances [7].

Performance Enhancement Strategies

Multiple strategies have been developed to optimize the photocatalytic performance of MOFs:

Metal Site Engineering: Selecting appropriate metal nodes (e.g., Ti⁴⁺, Fe³⁺, Zr⁴⁺) tunes the electronic structure, band gap, and charge transfer characteristics [12]. Incorporating multiple metal species enables metal-to-metal charge transfer, enhancing spatial electron-hole separation.

Ligand Functionalization: Modifying organic linkers with electron-donating groups (e.g., -NH₂) or extending π-conjugation red-shifts light absorption and narrows band gaps [7]. Porphyrin-based ligands have demonstrated exceptional photocatalytic activity in various organic transformations.

Heterojunction Construction: Combining MOFs with complementary materials (semiconductors, carbon materials, polymers) creates interfacial electric fields that suppress charge recombination [13].

Defect Engineering: Intentionally introducing coordinatively unsaturated metal sites or missing linkers creates additional active sites and modifies electronic structures to enhance photocatalytic efficiency [7].

Table 3: MOF Photocatalysts and Their Modification Strategies

| MOF Platform | Modification Strategy | Application | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH₂-MIL-125(Ti) | Amino-functionalization | CO₂ reduction | Enhanced visible light absorption [12] |

| Porphyrin MOFs | Metalation (In³⁺, Sn⁴⁺) | Organic transformations | Improved charge separation [12] |

| UiO-66 | Defect engineering | Pollutant degradation | Increased active sites [7] |

| MIL-100/101 | Heterojunction construction | H₂ production | Reduced charge recombination [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Photocatalytic CO₂ Reduction Using MOFs

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: Amino-functionalized MOF (e.g., NH₂-MIL-125(Ti))

- Reaction medium: CO₂-saturated acetonitrile/water mixture

- Sacrificial donor: Triethanolamine (TEOA)

- Light source: Visible light (λ > 420 nm)

- Reactor: Gas-tight photocatalytic system

Procedure:

- Activate MOF photocatalyst by heating under vacuum

- Disperse catalyst in solvent/sacrificial donor mixture

- Purge reaction system with CO₂ to ensure saturation

- Illuminate with visible light under continuous stirring

- Analyze gas products by gas chromatography at regular intervals

- Quantify liquid products by NMR or HPLC

Key Parameters:

- Catalyst loading: 5-10 mg/mL

- Water content critical for proton source

- Temperature maintained at 25°C

- Reaction time typically 4-6 hours

Diagram 2: MOF photocatalytic mechanism showing Linker-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Photocatalytic Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ Perovskite | Single-electron redox mediator | Biginelli reaction [9] | Visible light absorption, recyclable, band gap ~2.3 eV |

| Transition metal-substituted POMs | Visible-light photocatalyst | Dye degradation, CO₂ reduction [10] | Tunable redox properties, ROS generation |

| NH₂-MIL-125(Ti) | MOF photocatalyst | CO₂ reduction, organic transformations [12] | Amino-functionalized, visible light responsive |

| Triethanolamine (TEOA) | Sacrificial electron donor | CO₂ reduction, H₂ production experiments | Hole scavenger, enhances charge separation |

| Rhodamine B | Model pollutant | Photocatalytic degradation studies [10] | Visible light absorption, standard for efficiency testing |

The diverse classes of inorganic photocatalysts—metal oxides, perovskites, polyoxometalates, and metal-organic frameworks—each offer unique advantages and limitations for photocatalytic applications. Metal oxides provide stability and established synthesis protocols, perovskites offer exceptional optoelectronic properties and structural tunability, POMs deliver reversible redox activity and structural specificity, while MOFs combine high surface areas with molecular precision.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing visible light absorption, improving charge separation efficiency, increasing active site density, and ensuring long-term stability under operational conditions. The integration of computational design with experimental synthesis will accelerate the development of next-generation photocatalysts with tailored properties for specific applications. As these materials continue to evolve, they hold tremendous promise for addressing critical challenges in renewable energy generation and environmental sustainability.

Photoredox catalysis represents a revolutionary branch of photochemistry that utilizes single-electron transfer (SET) processes to enable novel organic transformations under mild conditions [14]. This catalytic platform has experienced significant renaissance since the late 2000s, emerging as a powerful strategy for activating small molecules through the conversion of visible light into chemical energy [15]. The field is founded upon the ability of photoredox catalysts—typically transition metal complexes or organic dyes—to absorb visible light photons and engage in SET events with organic substrates, thereby generating reactive intermediates that are otherwise inaccessible through traditional thermal activation pathways [15]. The unique capacity of excited photoredox catalysts to act as both strong oxidants and reductants simultaneously provides access to previously elusive redox-neutral reaction manifolds, contrasting directly with traditional electrochemical methods where the reaction medium is exclusively either oxidative or reductive [15].

The fundamental importance of photoredox catalysis extends across multiple disciplines, including pharmaceutical development, material science, and biomedical research [16]. Within organic chemistry specifically, this methodology has enabled remarkable advances in C-C and C-X bond formations, late-stage functionalization of complex molecules, and the development of asymmetric synthetic protocols [16] [15]. The ongoing evolution of photoredox catalysis continues to address longstanding challenges in synthetic chemistry while aligning with principles of sustainable chemistry through the use of visible light as a traceless reagent [17] [16].

Fundamental Mechanisms

The photoredox cycle begins with the absorption of a photon of visible light by the catalyst, prompting an electron to move from the metal-centered d orbital to a ligand-centered π* orbital in a process known as metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) [14]. This initial excited electronic state rapidly relaxes through internal conversion to a singlet excited state, which then undergoes intersystem crossing to form a longer-lived triplet excited state [14]. For the common photosensitizer tris-(2,2'-bipyridyl)ruthenium ([Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺), this triplet excited state exhibits a substantial lifetime of approximately 1100 nanoseconds, providing sufficient time for subsequent electron transfer processes to compete effectively with radiative decay pathways [14].

The photophysical properties governing this excitation process are crucial for catalytic efficiency. According to the Rehm-Weller equation, the redox potentials of the excited state can be estimated from ground-state electrochemical data and spectroscopic parameters [14]:

- E*¹/₂red = E₁/₂red + E₀,₀ + wᵣ (Reduction potential of excited state)

- E*¹/₂ox = E₁/₂ox - E₀,₀ + wᵣ (Oxidation potential of excited state)

Here, E₀,₀ represents the zero-zero excitation energy (typically approximated from the fluorescence spectrum), and wᵣ represents the work function accounting for electrostatic interactions during electron transfer [14]. This relationship demonstrates how visible light absorption translates into significantly enhanced redox power, with the excited triplet state of common photocatalysts possessing 50-60 kcal/mol of additional energy compared to their ground states [15].

Table 1: Redox Properties of Common Photoredox Catalysts

| Catalyst | E₁/₂⁺ Ox (V vs SCE) | E₁/₂ Red (V vs SCE) | E*₁/₂ Ox (V vs SCE) | E*₁/₂ Red (V vs SCE) | Excited State Lifetime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ | +1.29 | -1.33 | -0.81 | +0.77 | ~1100 ns |

| Ir(ppy)₃ | +1.73 | -2.19 | -0.96 | +0.31 | ~1900 ns |

| 4CzIPN | +1.35 | -1.21 | -0.75 | +0.81 | ~16 ns |

Single-Electron Transfer (SET) Pathways

The long-lived triplet excited state of photoredox catalysts engages in outer-sphere electron transfer with organic substrates, following the principles of Marcus theory [14]. This electron tunneling process occurs most efficiently when the transfer is thermodynamically favorable and exhibits low intrinsic reorganization energy. The rigid, octahedral geometry of complexes like [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ minimizes structural reorganization during electron transfer, resulting in fast SET kinetics that compete effectively with the natural decay of the excited state [14].

Two distinct SET pathways are operative in photoredox cycles:

Oxidative Quenching: The excited catalyst (*PC) donates an electron to an electron acceptor (A), generating a reduced acceptor radical anion (A•⁻) and an oxidized catalyst (PC•⁺). The ground state catalyst is subsequently regenerated through SET from an electron donor (D), producing a donor radical cation (D•⁺) [17].

Reductive Quenching: The excited catalyst (*PC) accepts an electron from an electron donor (D), producing a reduced catalyst (PC•⁻) and a donor radical cation (D•⁺). The ground state catalyst is then regenerated through SET to an electron acceptor (A), yielding an acceptor radical anion (A•⁻) [17].

These complementary pathways generate radical ion intermediates that participate in various bond-forming steps, with the specific quenching mechanism determined by the relative redox potentials of the reaction components and the catalyst's photophysical properties [14] [17].

Diagram 1: Photoredox catalytic cycles showing oxidative and reductive quenching pathways

Advanced Multi-Photon Mechanisms

Recent advances have overcome the energy limitations of single-photon processes through multi-photon strategies that mimic natural photosynthesis. The seminal concept of consecutive photoinduced electron transfer (conPET) enables the generation of super-reductants and super-oxidants capable of activating exceptionally stable substrates [17].

In reductive conPET, initial excitation of the photocatalyst by a single photon is followed by reduction with a sacrificial SET donor to yield a catalyst radical anion. This semi-stable, higher energy ground-state species accumulates in sufficient concentration to absorb a second photon, generating a super-reducing excited state with reduction potentials reaching approximately -3.0 V vs SCE [17]. Conversely, oxidative conPET pathways generate super-oxidants through analogous two-photon accumulation, enabling the oxidation of challenging substrates with potentials beyond +2.0 V vs SCE [17].

These advanced mechanisms significantly expand the scope of photoredox catalysis beyond the inherent energy limitations of single visible light photons (1.8-3.1 eV), providing access to reactive intermediates previously only accessible through UV photolysis or highly energetic reagents [17].

Experimental Protocols

General Setup for Photoredox Catalytic Reactions

Purpose: To provide a standardized procedure for conducting photoredox catalytic transformations under controlled conditions.

Materials:

- Photoredox catalyst (e.g., [Ru(bpy)₃]Cl₂, Ir(ppy)₃, or organic dyes such as 4CzIPN)

- Anhydrous, deoxygenated solvents (acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO)

- Substrates and reagents (typically electron donors/acceptors)

- Sacrificial agents (e.g., triethylamine, diisopropylethylamine, or ascorbate)

- Inert atmosphere equipment (nitrogen or argon Schlenk line)

- Appropriate light source (blue, green, or white LEDs)

Equipment:

- Photoreactor with calibrated LED light source (wavelength appropriate for catalyst absorption)

- Schlenk flasks or sealed reaction vessels

- Magnetic stirrer with heating capability (if required)

- Syringes and needles for anhydrous reagent transfer

- Quartz or borosilicate glassware

Procedure:

- Reaction Preparation: In an inert atmosphere glove box or under nitrogen/argon purge, charge the reaction vessel with photoredox catalyst (typically 0.1-5 mol%), substrates, and sacrificial agents (if required).

- Solvent Addition: Add degassed, anhydrous solvent to achieve final substrate concentrations of 0.01-0.5 M.

- Deoxygenation: Perform three freeze-pump-thaw cycles or sparge the reaction mixture with inert gas for 20-30 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Irradiation: Place the reaction vessel at a fixed distance from the LED light source and initiate irradiation while maintaining constant stirring.

- Temperature Control: Maintain reaction temperature at 20-25°C using appropriate cooling if necessary, as LED systems can generate significant heat.

- Reaction Monitoring: Periodically monitor reaction progress using TLC, GC-MS, or LC-MS until completion.

- Work-up: Upon completion, concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure and purify using standard techniques (flash chromatography, recrystallization, or precipitation).

Safety Considerations:

- Always use appropriate eye protection when working with high-intensity light sources

- Employ fume hoods for reactions generating volatile compounds

- Exercise caution when handling pressurized vessels during deoxygenation cycles

Protocol for conPET-Mediated Super-Reductive Transformations

Purpose: To implement consecutive photoinduced electron transfer for substrate activation requiring extreme reduction potentials.

Modified Materials:

- conPET-active photocatalyst (e.g., pyrene-based redox catalysts, fluorinated organic dyes)

- Strong sacrificial electron donor (e.g., triethylamine, BNAH, or DIPEA)

- Enhanced light source (high-intensity blue or white LEDs)

Procedure:

- Follow steps 1-4 of the general setup protocol with the following modifications:

- Catalyst Selection: Employ conPET-active catalysts specifically designed for radical anion formation and subsequent excitation.

- Donor Optimization: Use stoichiometric amounts of sacrificial electron donor (1.5-3.0 equivalents relative to limiting substrate).

- Light Source Selection: Employ high-intensity LEDs with emission spectra matching both the primary catalyst and radical anion absorption bands.

- Reaction Monitoring: Pay particular attention to potential over-reduction side products through careful analytical monitoring.

Key Applications:

- Reductive cleavage of unactivated carbon-halogen bonds

- Generation and utilization of hydrated electrons for pollutant degradation [18]

- Detoxification of halogenated organic waste through reductive dehalogenation [18]

Protocol for Bismuth-Based Semiconductor Photocatalysis

Purpose: To utilize low-toxicity bismuth-based semiconductors for atom transfer radical addition (ATRA) reactions and related transformations.

Materials:

- Bismuth oxide (Bi₂O₃, 1-5 mol%) or other bismuth-based materials (Bi₂S₃, BiVO₄)

- Terminal alkene substrates

- Organic bromides (e.g., diethyl bromomalonate, CBr₄)

- Anhydrous DMSO or other polar aprotic solvents

Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: Pre-dry Bi₂O₃ at 120°C under vacuum for 2 hours to remove adsorbed moisture.

- Reaction Setup: In a Schlenk flask, combine Bi₂O₃ (1 mol%), terminal alkene (1.0 equiv), and organic bromide (1.2-2.0 equiv) under inert atmosphere.

- Solvent Addition: Add anhydrous DMSO (0.1 M concentration relative to alkene).

- Deoxygenation: Sparge the suspension with argon for 20 minutes.

- Irradiation: Illuminate the reaction mixture with white or blue LEDs (10-20 W) with vigorous stirring to maintain catalyst suspension.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor by TLC or GC-MS for consumption of starting material (typically 6-24 hours).

- Work-up: Dilute reaction with ethyl acetate, filter through Celite to remove catalyst, wash with brine, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude material by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Mechanistic Note: Commercial Bi₂O₃ may undergo partial dissolution in the presence of certain brominated substrates to form homogeneous BinBrm species that serve as the actual photocatalysts [19]. This homogeneous-heterogeneous dichotomy should be considered when optimizing reactions and interpreting results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Photoredox Catalysis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts | Light absorption, SET mediation | Long excited-state lifetimes, tunable redox properties | [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, Ir(ppy)₃, [Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy)]⁺ |

| Organic Photoredox Catalysts | Metal-free SET mediation | Lower cost, biocompatibility, diverse structures | 4CzIPN, Eosin Y, Mes-Acr⁺ |

| Bismuth-Based Catalysts | Sustainable semiconductor photocatalysis | Low toxicity, visible light absorption, heterogeneous/homogeneous duality | Bi₂O₃, BiVO₄, Bi₂WO₆, Bi₂S₃ |

| Sacrificial Electron Donors | Catalyst reductive regeneration | Favorable oxidation potential, stability of radical cations | Triethylamine, DIPEA, BNAH, ascorbate |

| Sacrificial Electron Acceptors | Catalyst oxidative regeneration | Favorable reduction potential, stability of radical anions | SF₆, persulfates, aryl diazonium salts |

| Solvents for Photoredox | Reaction medium | Anhydrous, degassed, minimal light absorption | MeCN, DMF, DMSO, acetone |

| LED Light Sources | Photon delivery | Specific wavelengths, controllable intensity | Blue (450 nm), green (525 nm), white (broad spectrum) |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Frontiers

Synthetic Organic Chemistry Applications

The implementation of photoredox catalysis in organic synthesis has enabled remarkable transformations that challenge traditional paradigm. The asymmetric α-alkylation of aldehydes represents a landmark achievement, solving a long-standing synthetic challenge through the synergistic combination of photoredox catalysis and enamine organocatalysis [15]. In this dual catalytic system, photoredox cycles generate electron-deficient radicals while chiral organocatalysts form enamine intermediates that capture these radicals with high enantioselectivity [15].

Photoredox catalysis has also revolutionized amine α-functionalization through the generation of α-amino radicals and iminium ion intermediates [15]. The seminal photoredox-catalyzed aza-Henry reaction demonstrated this principle, wherein single-electron oxidation of N-arylamines generates amine radical cations with significantly acidic α-C-H bonds [15]. Deprotonation yields α-amino radicals that can be further oxidized to iminium ions, which subsequently react with carbon-centered nucleophiles to form new C-C bonds [15]. This mechanistic manifold has been extended to incorporate diverse nucleophilic partners including malonates, cyanide, trifluoromethyl anions, electron-rich aromatics, and phosphonates [15].

Environmental and Green Chemistry Applications

The "green" potential of photoredox catalysis is exemplified by its application in environmental remediation, particularly through the sustainable generation and utilization of hydrated electrons for pollutant degradation [18]. Innovative mechanisms that combine energy and electron transfer in supramolecular environments enable the production of these extremely strong reductants using only visible light photons and bioavailable ascorbate as sacrificial donor [18]. This approach has demonstrated efficacy in the reductive detoxification of halogenated organic waste, including model compounds like chloroacetate that traditionally required high-energy UV-C radiation for electron generation [18].

The field continues to evolve through integration with complementary activation modes, including dual catalytic strategies that merge photoredox cycles with nickel catalysis for cross-coupling reactions, electrocatalysis in photoelectrochemistry (PEC), and energy transfer processes that enable novel cycloadditions and isomerizations [17] [15]. These interdisciplinary approaches leverage the unique advantages of each activation mode while mitigating their individual limitations, collectively expanding the synthetic toolbox available for complex molecule construction.

Diagram 2: Photoredox-catalyzed amine α-functionalization via α-amino radical and iminium ion intermediates

The photoredox cycle, with its intricate interplay of single-electron transfer and energy transfer mechanisms, has fundamentally transformed synthetic chemistry by providing unprecedented access to reactive intermediates under exceptionally mild conditions. The continued evolution of this field—from fundamental photophysical studies to sophisticated multi-photon processes and sustainable applications—demonstrates the enduring potential of photoredox catalysis to address longstanding challenges in organic synthesis. As mechanistic understanding deepens and catalyst design becomes increasingly sophisticated, photoredox catalysis will undoubtedly continue to enable novel bond disconnections and streaml

Band Gap Engineering and Charge Carrier Dynamics in Inorganic Semiconductors

Band gap engineering serves as a foundational strategy for optimizing inorganic semiconductors for photocatalytic applications, enabling precise control over light absorption and energy conversion processes. In photocatalytic reactions, a semiconductor's band gap determines the portion of the solar spectrum it can absorb, while the alignment of its valence and conduction bands dictates its redox capabilities for driving chemical transformations [20]. The burgeoning field of bismuth-based photocatalysts exemplifies this principle, where materials like Bi₂O₃ (band gap ~2.5-2.8 eV) and Bi₂S₃ (band gap ~1.3 eV) demonstrate tunable absorption across the visible light spectrum, making them particularly valuable for organic synthesis applications under solar irradiation [19]. Similarly, halide perovskites (HPs) have emerged as promising photocatalysts due to their highly tunable band structures, which can be modulated through compositional adjustments to the A, B, or X sites in their ABX₃ crystal structure [21].

The strategic design of heterostructures represents an advanced approach to band gap engineering, particularly through the integration of two-dimensional (2D) materials with inorganic semiconductors. These configurations create interfacial properties that enhance light absorption, improve charge separation and transfer, and provide energetic redox capacity [21]. For instance, coupling halide perovskites with 2D materials such as graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄), transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), or MXenes can compensate for the deficiencies of individual materials while leveraging their synergistic properties [21]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for implementing band gap engineering strategies and analyzing charge carrier dynamics to advance photocatalytic research in inorganic compound synthesis.

Fundamental Principles and Key Concepts

Band Gap Theory in Semiconductor Photocatalysis

In photocatalytic systems, the band gap represents the energy difference between the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB), determining the minimum photon energy required to generate electron-hole pairs [20]. For inorganic semiconductors, this energy gap falls typically between 0.5-4.0 eV, corresponding to light absorption from infrared to ultraviolet wavelengths. The band gap directly influences a photocatalyst's efficiency by determining:

- Spectral Absorption Range: Narrow band gap semiconductors (e.g., Bi₂S₃ at ~1.3 eV) absorb broader solar spectra but exhibit reduced redox potential, while wider band gap materials (e.g., TiO₂ at ~3.2 eV) possess stronger redox capability but limited visible light absorption [19].

- Charge Carrier Generation: Photons with energy exceeding the band gap excite electrons from the VB to the CB, creating electron-hole pairs that drive surface redox reactions.

- Recombination Dynamics: The band structure influences the probability of electron-hole recombination, with indirect band gap materials typically exhibiting longer charge carrier lifetimes than direct band gap semiconductors [20].

Charge Carrier Dynamics in Photocatalytic Systems

Upon photoexcitation, charge carriers in inorganic semiconductors undergo complex dynamics that ultimately determine photocatalytic efficiency:

- Generation: Light absorption promotes electrons to the CB, leaving holes in the VB, with generation rates dependent on absorption coefficient and light intensity.

- Separation and Migration: Internal electric fields and band bending facilitate charge separation, with carriers migrating toward semiconductor surfaces.

- Recombination: Bulk, surface, or Auger recombination processes can annihilate electron-hole pairs before they participate in chemical reactions.

- Surface Transfer: Electrons and holes transfer to adsorbed reactant molecules, initiating reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively [21].

The timescales of these processes vary significantly, with light absorption occurring in 10⁻¹⁵–10⁻⁹ seconds, charge separation and migration in <10⁻¹⁵ seconds, recombination in 10⁻⁷–10⁻⁶ seconds, and surface redox reactions in 10⁻³–10⁻¹ seconds [21]. This disparity highlights the critical need to suppress recombination to enhance photocatalytic efficiency.

Table 1: Characteristic Time Scales of Charge Carrier Processes in Photocatalytic Systems

| Process | Time Scale | Impact on Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Light Absorption | 10⁻¹⁵ – 10⁻⁹ s | Determines initial carrier generation rate |

| Charge Separation & Migration | <10⁻¹⁵ s | Governs initial separation efficiency |

| Charge Recombination | 10⁻⁷ – 10⁻⁶ s | Primary efficiency loss mechanism |

| Surface Redox Reactions | 10⁻³ – 10⁻¹ s | Rate-limiting step for product formation |

Research Reagent Solutions for Band Gap Engineering

The following table catalogues essential materials and their functions in band gap engineering and photocatalytic studies:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Band Gap Engineering and Photocatalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Oxide (Bi₂O₃) | Medium-bandgap photocatalyst (2.5-2.8 eV) for visible light absorption | α-alkylation of aldehydes, ATRA reactions [19] |

| Bismuth Sulfide (Bi₂S₃) | Low-bandgap photocatalyst (~1.3 eV) for broad spectrum absorption | Photocatalytic radical reactions [19] |

| Halide Perovskites (ABX₃) | Tunable bandgap semiconductors for customizable optoelectronic properties | H₂ evolution, CO₂ reduction, organic synthesis [21] |

| 2D Materials (g-C₃N₄, MXenes, TMDs) | Heterostructure components for enhanced charge separation | HP/2D composite photocatalysts [21] |

| Diethyl Bromomalonate | Radical precursor in photocatalytic organic transformations | ATRA reactions with olefins [19] |

| MacMillan Imidazolidinone | Chiral organocatalyst for enantioselective transformations | Asymmetric α-alkylation of aldehydes [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Band Gap Engineering and Analysis

Protocol: Band Gap Tuning through Halide Perovskite Compositional Control

Principle: The band gap of halide perovskites (ABX₃) can be systematically tuned by varying the halide composition (X site) while maintaining the crystal structure, enabling precise control over light absorption properties [21].

Materials:

- Lead halide precursors (PbI₂, PbBr₂, PbCl₂)

- Organic cations (MA⁺, FA⁺) or inorganic cations (Cs⁺)

- Solvents (DMF, DMSO, γ-butyrolactone)

- 2D material substrates (g-C₃N₄, MXenes, graphene oxide)

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Prepare 1M solutions of lead halides in anhydrous DMF with molar ratios adjusted to target composition (e.g., Pb(I₁₋ₓBrₓ)₂ for mixed halide perovskites).

- Cation Incorporation: Add organic cations (e.g., methylammonium iodide) at equimolar ratios relative to lead content under inert atmosphere.

- Thin Film Deposition: Spin-coat precursor solutions onto substrates at 2000-5000 rpm for 30-60 seconds.

- Thermal Annealing: Anneal films at 90-100°C for 10-30 minutes to facilitate crystallization.

- Heterostructure Formation: For 2D/3D composites, pre-deposit 2D material layers prior to perovskite deposition.

- Band Gap Characterization: Utilize UV-Vis spectroscopy with Tauc plot analysis to determine optical band gaps.

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain strict control over humidity (<1% RH) during processing

- Optimize annealing temperature/time to prevent halide segregation

- For mixed halide systems, confirm homogeneous distribution through XRD mapping

Protocol: Photocatalytic ATRA Reaction Using Bi₂O₃

Principle: Bismuth oxide serves as a visible-light photocatalyst for atom transfer radical addition (ATRA) reactions, leveraging its band structure to generate radicals from organic bromides for carbon-carbon bond formation [19].

Materials:

- Bi₂O₃ photocatalyst (commercial or synthesized)

- Terminal alkene substrate (e.g., 5-hexen-1-ol)

- Alkyl bromide radical precursor (e.g., diethyl bromomalonate)

- Anhydrous DMSO as solvent

- Visible light source (blue LEDs, 450-470 nm)

- Inert atmosphere equipment (glove box or Schlenk line)

Procedure:

- Catalyst Activation: Pre-treat Bi₂O₃ (1 mol%) at 150°C under vacuum for 1 hour to remove surface contaminants.

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: In a dried glass vial, combine alkene (1.0 equiv), alkyl bromide (1.2 equiv), and activated Bi₂O₃ in anhydrous DMSO (0.1 M concentration).

- Deoxygenation: Purge reaction mixture with argon or nitrogen for 15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Photoreaction: Irradiate mixture under blue LEDs (10-15 W) with constant stirring at room temperature for 12-24 hours.

- Reaction Monitoring: Track conversion via TLC or GC-MS sampling at 2-hour intervals.

- Product Isolation: Centrifuge to remove catalyst, extract with ethyl acetate, and purify via column chromatography.

Mechanistic Insight: The photogenerated electrons in Bi₂O₃ facilitate reductive cleavage of organic bromides, forming carbon radicals that add to alkenes. The resulting radical intermediates undergo either radical-polar crossover (oxidation by holes) or halogen atom transfer to yield bifunctionalized products [19].

Protocol: Charge Carrier Dynamics Analysis via Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

Principle: Transient absorption spectroscopy enables direct observation of charge carrier generation, recombination, and transfer processes in photocatalytic materials with femtosecond to microsecond temporal resolution.

Materials:

- Semiconductor thin films or nanoparticle suspensions

- Pump laser source (wavelength tunable, typically 400-800 nm)

- Probe light source (white light continuum)

- Spectrometer with fast detector (CCD or photodiode array)

- Data acquisition system with temporal resolution <100 fs

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thin films with optimized thickness (100-500 nm) or colloidal solutions with appropriate optical density (0.3-1.0 at excitation wavelength).

- Instrument Alignment: Align pump and probe beams with spatial and temporal overlap, ensuring proper polarization conditions.

- Pump-Probe Delay Scan: Collect transient spectra at delay times from 100 fs to 10 μs using automated delay stage.

- Global Analysis: Fit time-dependent spectral data to kinetic models to extract decay-associated spectra.

- Charge Transfer Analysis: Compare dynamics in bare semiconductors versus heterostructures to quantify interfacial transfer rates.

Data Interpretation:

- Rapid decay components (<100 ps) typically represent defect trapping

- Intermediate decays (100 ps - 10 ns) often correspond to band-to-band recombination

- Long-lived components (>10 ns) indicate separated charges with potential for photocatalytic activity

Visualization of Charge Transfer Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the charge transfer dynamics in a halide perovskite/2D material heterostructure, a key configuration for enhanced photocatalytic performance:

Diagram 1: Charge Transfer in Semiconductor Heterostructure - This visualization depicts the enhanced charge separation in a halide perovskite/2D material heterostructure, where electrons transfer to the 2D material's conduction band while holes remain in the perovskite, suppressing recombination and enhancing surface redox reactions for photocatalysis [21].

Application Notes for Photocatalytic Organic Synthesis

α-Alkylation of Aldehydes Using Bi₂O₃ Photocatalysis

The application of band-gap engineered semiconductors in organic synthesis is exemplified by the α-alkylation of aldehydes using Bi₂O₃ as a visible-light photocatalyst [19]. This transformation combines the photophysical properties of the semiconductor with the stereocontrol of organocatalysis:

Reaction Mechanism:

- Photoexcitation: Visible light promotes electrons from the VB to the CB of Bi₂O₃, generating electron-hole pairs.

- Radical Generation: Photoexcited electrons reduce α-bromocarbonyl compounds via single-electron transfer, generating carbon radicals and bromide anions.

- Enamine Formation: Aldehydes condense with chiral imidazolidinone organocatalysts to form enamine intermediates.

- Radical Addition: Carbon radicals add to enamines, forming α-amino radicals.

- Oxidation and Regeneration: Holes in the VB oxidize the α-amino radicals, regenerating iminium ions that hydrolyze to release products and regenerate the organocatalyst.

Optimization Guidelines:

- Catalyst loading: 1-5 mol% Bi₂O₃ provides optimal efficiency

- Light source: Blue LEDs (450 nm) align with Bi₂O₃ absorption edge

- Solvent selection: DMSO or DMF facilitates both semiconductor excitation and organocatalysis

- Atmosphere: Inert conditions prevent radical quenching by oxygen

Heterostructure Design for Enhanced CO₂ Reduction

The construction of halide perovskite/2D material heterostructures represents a cutting-edge application of band gap engineering for photocatalytic CO₂ reduction [21]:

Design Principles:

- Band Alignment: Select 2D materials with conduction bands more negative than CO₂ reduction potentials (-0.24 V to -1.90 V vs. SHE depending on product).

- Interface Engineering: Maximize contact area between components to facilitate charge transfer.

- Morphology Control: Tailor perovskite dimensionality (3D, 2D, 0D) to optimize band structure and surface-to-volume ratio.

Performance Metrics:

- Quantum efficiency: >5% for practical applications

- Selectivity: >80% toward desired C₁ or C₂ products

- Stability: >100 hours operational lifetime

Analytical Methods for Characterization

Band Gap Determination Techniques

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Band Gap and Charge Carrier Characterization

| Technique | Information Obtained | Experimental Parameters | Applications in Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy | Optical band gap via Tauc plot analysis | Scan range: 200-800 nm, Baseline correction | Determination of light absorption range and band gap type (direct/indirect) [20] |

| Photoelectron Spectroscopy | Valence band maximum, ionization energy | Ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁹ mbar), X-ray or UV source | Band alignment studies for heterostructure design [22] |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy | Flat band potential, carrier density | Frequency range: 0.1 Hz-1 MHz, DC bias sweep | Determination of band positions relative to redox potentials [21] |

| Transient Absorption Spectroscopy | Charge carrier lifetimes, recombination kinetics | Femtosecond to microsecond time resolution | Quantification of charge separation efficiency in heterostructures [21] |

| Photoluminescence Spectroscopy | Defect states, recombination pathways | Excitation wavelength matching band gap | Identification of trap states and evaluation of material quality |

Protocol: Tauc Plot Analysis for Band Gap Determination

Principle: The Tauc method transforms optical absorption data to determine semiconductor band gap energy and distinguish between direct and indirect transitions.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Collect UV-Vis absorption spectrum of semiconductor thin film or powder.

- Baseline Correction: Subtract background scattering using baseline scan.

- Tauc Transformation: Calculate (αhν)¹/ⁿ versus hν, where α is absorption coefficient, hν is photon energy, and n depends on transition type (n=1/2 for indirect, n=2 for direct allowed transitions).

- Linear Extrapolation: Identify the linear region of the Tauc plot and extrapolate to the energy axis.

- Band Gap Assignment: The intercept provides the optical band gap energy.

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Direct band gap materials show distinct linear regions in (αhν)² vs. hν plots

- Indirect band gap materials exhibit linearity in (αhν)¹/² vs. hν plots

- Urbach tail analysis provides information on structural disorder

The integration of band gap engineering strategies with advanced charge carrier dynamics analysis provides a powerful framework for developing efficient photocatalytic systems for organic synthesis. By systematically applying the protocols and characterization methods outlined in this document, researchers can design semiconductor materials with optimized light absorption and charge separation properties, ultimately advancing the field of photocatalytic organic transformations.

Synergistic Effects in Inorganic-Organic Hybrid Photocatalytic Systems

The integration of inorganic and organic components into hybrid photocatalytic systems represents a transformative strategy to overcome the inherent limitations of single-component photocatalysts. While inorganic semiconductors (e.g., TiO₂, SrTiO₃) offer robust framework structures and efficient charge transport, they often suffer from limited visible-light absorption and rapid recombination of photogenerated carriers [23]. Conversely, organic semiconductors (e.g., covalent organic frameworks, conjugated polymers) provide excellent synthetic tunability, strong visible-light absorption, and structural versatility, but are typically constrained by short exciton diffusion lengths and low charge carrier mobility [23] [24]. By strategically combining these materials, researchers can create synergistic systems that enhance light harvesting, improve charge separation, and increase the overall efficiency of photocatalytic reactions, including water splitting, H₂O₂ production, and organic transformations relevant to drug discovery [23] [25] [24].

The synergy in these hybrid systems primarily manifests at the interface between the inorganic and organic components, where optimized energy alignment facilitates the transfer of photogenerated charges. This interaction helps to suppress the recombination of electron-hole pairs, thereby increasing the population of long-lived charge carriers available for surface redox reactions [23]. For solar-driven overall water splitting, a process with a theoretical thermodynamic minimum of 1.23 eV but practical requirements often exceeding 1.7 eV due to overpotentials, such enhancements are critical for achieving viable solar-to-hydrogen (STH) conversion efficiencies [23]. Similarly, in the context of H₂O₂ production and organic synthesis, these hybrid systems can enhance selectivity and yield under mild reaction conditions, making them particularly attractive for pharmaceutical applications [25] [24].

Fundamental Synergistic Mechanisms

Charge Transfer and Separation Dynamics

The primary synergistic mechanism in inorganic-organic hybrid photocatalysts involves the efficient separation and migration of photogenerated charge carriers across their interface. Upon photoexcitation, several key processes occur on different timescales [23]:

- Photoinduced Electron Transfer: Electrons can be injected from the organic component (e.g., a photosensitizer) to the conduction band of the inorganic semiconductor, particularly when the organic material possesses a higher-energy excited state.

- Hole Transfer Conversely: Holes may migrate in the opposite direction, from the inorganic valence band to the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the organic material.

- Interface Engineering: The formation of a Type-II (staggered) band alignment or a Z-scheme heterojunction at the hybrid interface is often deliberate, facilitating the spatial separation of electrons and holes and thereby reducing recombination [23] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the primary charge transfer pathways that underpin the synergy in these hybrid systems:

These charge transfer processes are crucial for enhancing the performance of multi-electron reactions, such as water oxidation and oxygen reduction, which are fundamental to processes like overall water splitting and H₂O₂ production [23] [24]. The inorganic framework often acts as a robust charge transport highway, while the organic component can be tuned to expand the light absorption profile and provide specific catalytic sites [23].

Enhanced Light Harvesting and Stability

The complementary optical properties of inorganic and organic materials enable hybrid systems to achieve a broader solar spectrum utilization. Organic components can be molecularly engineered to absorb specific visible wavelengths, acting as effective antennas that transfer energy to the inorganic component or directly participate in the redox chemistry [23] [25]. Furthermore, the interaction between the two components can lead to improved stability; for instance, the organic polymer in a polyaniline/ZnO hybrid was shown to promote directional charge transfer, which not only boosted photocatalytic activity but also enhanced the operational stability of the system [23].

Application Protocols for Hybrid Photocatalysis

Protocol for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution via Biomass Photoreforming

Principle: This protocol utilizes organic–inorganic hybrid (OIH) photocatalysts to produce hydrogen (H₂) through the photoreforming (PR) of biomass derivatives. PR is an alternative to overall water splitting, as it couples H₂ evolution with the oxidation of organic substrates (e.g., biomass, glycerol), which is a thermodynamically more favorable process (ΔG° < 0) [26]. The organic content of the biomass acts as a hole scavenger, suppressing charge recombination and enabling H₂ production under milder conditions.

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: Pt nanoparticles photodeposited on an organic–inorganic hybrid substrate (e.g., a covalent organic framework integrated with TiO₂ or another metal oxide).

- Reaction Medium: Aqueous solution containing a biomass-derived substrate (e.g., 10% v/v glycerol or lactic acid).

- Light Source: 300 W Xe lamp with a water filter to remove infrared radiation.

- Reactor: Multimodal flow reactor or a simple batch reactor with quartz window for top-irradiation [27].

- Gas Detection: Real-time gas analyzer mass spectrometer (RTGA-MS) or gas chromatography (GC) for H₂ quantification.

Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation (Photodeposition of Pt):

- Disperse the base OIH photocatalyst (e.g., 100 mg) in an aqueous solution containing the biomass substrate (e.g., 10% glycerol in 100 mL water).

- Add the Pt precursor (e.g., chloroplatinic acid, H₂PtCl₆) to the suspension.

- Irradiate the suspension with the Xe lamp for 1-2 hours under constant stirring to facilitate the reduction of Pt ions and their deposition as metallic nanoparticles on the photocatalyst surface.

- Photocatalytic Reaction:

- Load the Pt-deposited OIH photocatalyst (e.g., 50 mg) into the reactor containing the aqueous biomass solution.

- Purge the reactor with an inert gas (e.g., Argon) at a controlled flow rate (e.g., 20 mL min⁻¹) to remove dissolved oxygen and establish an inert atmosphere [27].

- Initiate irradiation with the Xe lamp under constant stirring. Maintain the reactor temperature at 25°C using a recirculating water chiller.

- Continuously monitor the effluent gas stream using RTGA-MS to quantify H₂ production in real-time.

- Calculation of Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY):

- The AQY can be calculated using the formula:

AQY (%) = (Number of reacted electrons / Number of incident photons) × 100= [(2 × Number of evolved H₂ molecules) / Number of incident photons] × 100[27]. - The incident photon flux should be measured using a calibrated photodiode at the specific wavelength of interest.

- The AQY can be calculated using the formula:

Protocol for Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) Production

Principle: H₂O₂ is produced photocatalytically via a two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (2e⁻ ORR: O₂ + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂O₂) and/or a two-electron water oxidation reaction (2e⁻ WOR: 2H₂O + 2h⁺ → H₂O₂ + 2H⁺) [24]. Organic-inorganic hybrid photocatalysts are particularly suited for this as the organic component can be tuned to favor the 2e⁻ pathway for O₂ reduction, while the inorganic component can aid in charge separation.

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: A hybrid material such as carbon nitride integrated with BiVO₄ or a similar system designed for selective O₂ reduction.

- Reaction Medium: Pure water or an aqueous electrolyte solution.

- Oxidant: Molecular oxygen (O₂) saturated in the solution.

- Light Source: Solar simulator or LED array (e.g., 420 nm blue LED).

- Analysis: Colorimetric detection using titanium oxalate or cerium sulfate to quantify the produced H₂O₂.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Dissolve oxygen in the reaction solution by bubbling O₂ gas for at least 30 minutes prior to the experiment.

- Disperse the hybrid photocatalyst (e.g., 20 mg) in the O₂-saturated solution (e.g., 40 mL) in a batch reactor.

- Illumination:

- Irradiate the suspension under constant O₂ bubbling and stirring.

- Control the temperature using a water jacket.

- Quantification:

- At regular time intervals, withdraw a sample of the reaction mixture (e.g., 1 mL) and centrifuge to remove the catalyst particles.

- Mix the clear supernatant with the colorimetric reagent and measure the absorbance of the resulting complex using a UV-Vis spectrometer. Calculate the H₂O₂ concentration by comparing against a standard calibration curve.

Quantitative Performance Data of Hybrid Systems

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Hybrid Photocatalytic Systems

| Hybrid Photocatalyst | Reaction Type | Performance Metric | Value | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt/SrTiO₃:Al (Inorganic Benchmark) | Overall Water Splitting | Solar-to-Hydrogen (STH) Efficiency | 0.76% | [23] |

| Polyaniline/ZnO Hybrid | Water Splitting | Activity & Stability | Significantly Enhanced vs. ZnO alone | [23] |

| Organic–Inorganic Hybrids | H₂O₂ Production | Yield | Higher than single-component systems | [24] |

| Pt/TiO₂ (Anatase) | H₂ Evolution (from MeOH/H₂O) | Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY @ 340 nm) | 55% ± 2% | [27] |

| Cu/TiO₂ | H₂ Evolution (from Glycerol) | Hydrogen Production | 1240 μmol L⁻¹ | [26] |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Photocatalyst Components

| Material Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic | TiO₂, SrTiO₃, WO₃, BiVO₄ | High stability, efficient charge transport, cost-effective | Narrow light absorption, rapid charge recombination |

| Organic | Carbon Nitride, Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs), Conjugated Polymers | Tunable absorption & energy levels, synthetic versatility | Short exciton diffusion length, low carrier mobility |

| Organic–Inorganic Hybrid | COF-BiVO₄, Polyaniline-TiO₂, Dye-Sensitized ZnO | Synergistic light harvesting, improved charge separation, enhanced stability | Interface complexity, potential stability issues under long-term operation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Hybrid Photocatalysis Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| [Ru(bpy)₃]Cl₂ | Organometallic photoredox catalyst; engages in Single-Electron Transfer (SET) upon visible light excitation. | Peptide functionalization and tyrosine-specific bioconjugation [25]. |

| Ir-based Complexes (e.g., [Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy)]PF₆) | High-performance photoredox catalyst with long-lived excited states and strong oxidizing power. | Decarboxylative macrocyclization of peptides [25]. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Crystalline, porous organic polymers with predictable structures and high surface areas. | Sp² carbon-conjugated COFs enable efficient visible-light absorption and long-range exciton transport [23]. |

| Pt Nanoparticles | Cocatalyst for proton reduction; provides active sites for H₂ evolution. | Photodeposited on TiO₂ or hybrid substrates to drastically enhance H₂ production yield [27]. |

| Methanol / Glycerol | Sacrificial electron donor (hole scavenger); consumed to prevent electron-hole recombination. | Used in H₂ evolution half-reactions (e.g., photoreforming) to significantly boost efficiency [26] [27]. |

Experimental Workflow for Hybrid System Evaluation

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for preparing, testing, and evaluating a hybrid photocatalytic system, from initial catalyst synthesis to final performance assessment.

Translating Light into Innovation: Photocatalytic Methods in Drug Discovery

Peptide Functionalization and Macrocyclization via Photoredox Catalysis

The integration of photoredox catalysis into peptide science represents a transformative advancement, aligning with broader research on photocatalytic reactions involving inorganic compounds. This approach provides synthetic chemists with a powerful, mild, and versatile toolset for modifying peptides and constructing macrocyclic architectures that are increasingly important in modern drug discovery [28]. Unlike traditional thermal reactions, photoredox catalysis utilizes visible light to generate highly reactive radical intermediates under gentle conditions, allowing for exceptional functional group tolerance and chemoselectivity [29] [28]. This is particularly valuable for modifying complex peptides bearing sensitive functionalities.

The fundamental principle involves photoexcited catalysts, typically transition metal complexes or organic dyes, that engage in single-electron transfer (SET) processes with peptide substrates [29]. These processes unlock unique reaction pathways, enabling precise functionalization at specific amino acid residues and facilitating challenging macrocyclization reactions through novel mechanistic pathways [30]. This application note details key protocols and illustrative examples to equip researchers with practical knowledge for implementing these methods in drug development contexts.

Key Principles and Mechanistic Insights

Photoredox catalysis operates through several well-established mechanisms. The most common involves oxidative or reductive quenching cycles of the photoexcited catalyst [29]. Upon absorption of a photon, the photocatalyst (PC) reaches an excited state (*PC) that acts as both a strong oxidant and reductant. In peptide chemistry, this excited state can oxidize native functional groups, such as carboxylates, generating radical species that participate in subsequent bond-forming steps [31]. The catalytic cycle is maintained by a terminal oxidant or reductant, ensuring the photocatalyst turns over multiple times.

A critical advantage in peptide applications is the ability to exploit subtle differences in the oxidation potentials of various functional groups to achieve site-selectivity. For instance, the C-terminal carboxylate of a peptide can be selectively oxidized over the side-chain carboxylic acids of aspartic or glutamic acid residues due to its lower oxidation potential, enabling precise modification at a single site without protecting groups [31] [32]. This principle underpins many of the most powerful photoredox methods for peptide chemistry.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Decarboxylative Macrocyclization of Peptides

This protocol describes the synthesis of macrocyclic peptides via a photoredox-catalyzed decarboxylative radical addition, enabling the formation of C-C bonds to close the peptide ring [31] [32].