Inorganic Catalyst Performance Comparison 2025: Materials, Mechanisms, and Market Applications for Advanced Research

This article provides a comprehensive 2025 analysis of inorganic catalyst performance, benchmarking materials from zeolites to advanced metal-organic hybrids.

Inorganic Catalyst Performance Comparison 2025: Materials, Mechanisms, and Market Applications for Advanced Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive 2025 analysis of inorganic catalyst performance, benchmarking materials from zeolites to advanced metal-organic hybrids. It explores foundational mechanisms, industrial applications in petrochemical and pharmaceutical sectors, and strategies for enhancing stability and selectivity. Synthesizing current market data and recent scientific advances, it offers a validated comparative framework to guide catalyst selection and development for researchers and industry professionals navigating evolving technological and regulatory landscapes.

Understanding Inorganic Catalysts: Core Materials, Properties, and Market Landscape

Inorganic catalysts represent a fundamental class of materials that drive essential chemical processes across industries from petroleum refining to pharmaceutical manufacturing. These substances are defined as heterogeneous catalysts comprising metals and their oxides designed to emulate the function of natural catalysts while possessing an inorganic structure that may not necessarily contain carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen molecules [1] [2]. The global inorganic catalyst market has demonstrated consistent growth, reaching $26.81 billion in 2024 with projections indicating expansion to $33.58 billion by 2029 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.0% [1] [2]. This growth is propelled by increasing demand for petroleum and petrochemical products, industrial expansion, and a heightened focus on sustainable practices [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the classification, performance characteristics, and experimental applications of inorganic catalysts is crucial for optimizing synthetic pathways, developing novel therapeutic compounds, and improving industrial processes. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of inorganic catalyst categories, their performance metrics across different applications, and detailed experimental methodologies for evaluating their efficacy in research settings.

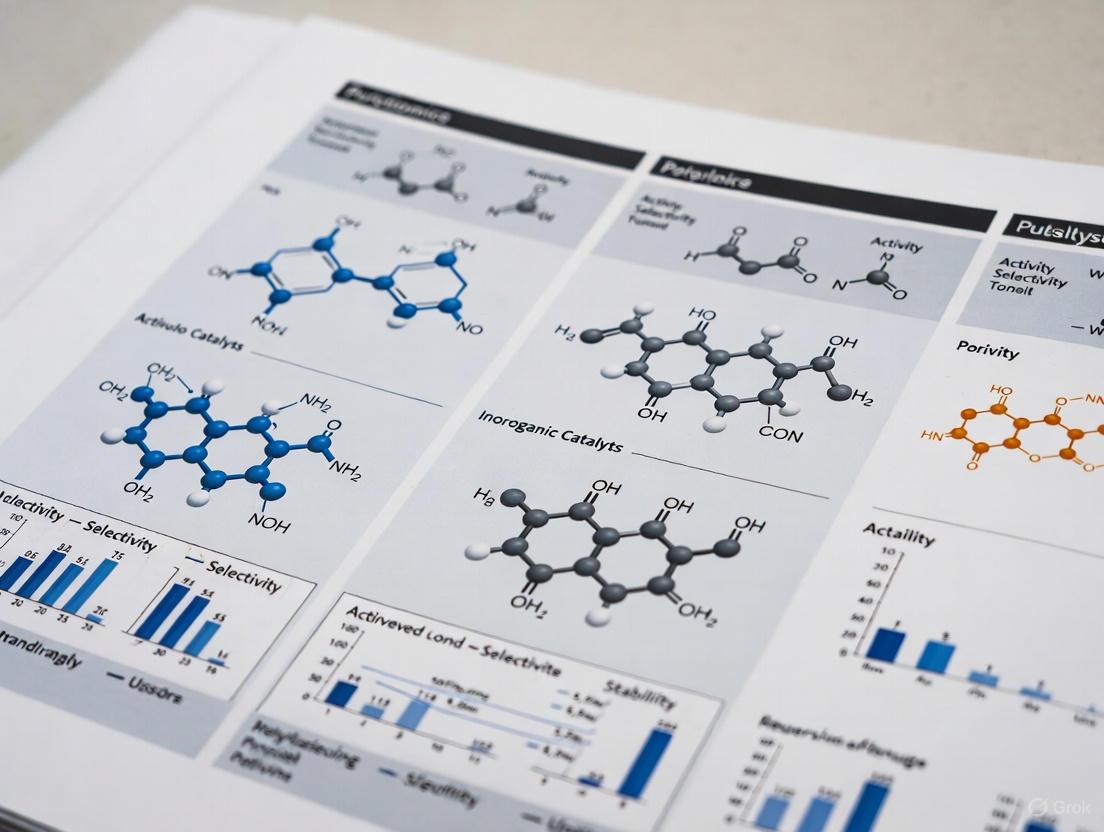

Classification and Types of Inorganic Catalysts

Inorganic catalysts are categorized based on their composition, structure, and functional properties. The primary classification includes zeolites, metals, and chemical compounds, each with distinct characteristics that determine their application suitability.

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Inorganic Catalysts

| Type | Subcategories | Structural Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolites | Natural Zeolites, Synthetic Zeolites | Crystalline, microporous aluminosilicates with well-defined channel systems | Petroleum refining, environmental purification, chemical synthesis [1] |

| Metals | Noble Metals (Pt, Pd, Rh), Base Metals (Fe, Ni, Cu) | Metallic nanoparticles on support materials or bulk metal surfaces | Automotive catalysts, hydrogenation, oxidation reactions [1] |

| Chemical Compounds | Metal Oxides, Salts and Coordination Compounds | Ionic or covalent solid-state structures with active sites | Polymerization, petrochemical processes, emission control [1] |

| Other Types | Heterogeneous, Homogeneous, Mixed Catalysts | Varied structural configurations from solid surfaces to molecular complexes | Specialized chemical transformations, pharmaceutical intermediates [1] |

Zeolite Catalysts

Zeolites represent a particularly significant category of inorganic catalysts, characterized as pure inorganic materials manufactured through hydrothermal synthesis [1] [2]. These crystalline aluminosilicates feature ordered pore structures and acidic sites that enable shape-selective catalysis—a property invaluable for discriminating between molecular isomers in complex synthetic pathways. The global emphasis on sustainability has further amplified zeolite applications in environmental remediation and green chemistry initiatives [1].

Metal-Based Catalysts

Metal catalysts encompass both noble and base metals, with selection often dictated by reaction requirements and economic considerations. Noble metal catalysts (e.g., Pt, Pd, Rh) typically exhibit superior activity and resistance to deactivation but command higher costs, while base metal catalysts (e.g., Ni, Cu, Fe) offer economical alternatives with tunable performance characteristics through appropriate support materials and promotors [1].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The performance of inorganic catalysts varies significantly across different applications and reaction conditions. The following comparative analysis highlights key performance metrics for major catalyst categories in industrial and research contexts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Inorganic Catalyst Types in Key Applications

| Catalyst Type | Activity | Selectivity | Stability | Regeneration Potential | Cost Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolites | High | Very High | Excellent | Recycling, Regeneration, Rejuvenation [1] | Moderate to High |

| Noble Metals | Very High | High | Good to Excellent | Limited | Low |

| Base Metals | Moderate to High | Variable | Moderate | Variable | High |

| Metal Oxides | Moderate | Moderate to High | Good | Recycling, Regeneration [1] | High |

| Chemical Compounds | Variable | High | Variable | Dependent on composition | Variable |

Application-Specific Performance Metrics

Petroleum Refining and Petrochemicals

In petroleum refining, zeolite catalysts, particularly fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalysts, demonstrate exceptional performance in converting heavy crude fractions into valuable transportation fuels. Technological advancements like Grace & Co's PARAGON FCC catalyst technology, which incorporates a rare-earth-based vanadium trap, have significantly enhanced operational flexibility and profitability for refiners processing diverse feedstock types [1]. The integration of such advanced catalytic systems has enabled the petrochemical industry to maintain robust efficiency despite fluctuating crude quality and increasingly stringent environmental regulations.

Chemical Synthesis and Pharmaceutical Applications

In chemical synthesis, particularly for pharmaceutical applications, inorganic catalysts enable key transformations including C-H functionalization, stereoselective additions, and cyclization reactions [3]. Recent advances in hybrid palladium catalysis have facilitated stereoselective 1,4-syn-additions to cyclic 1,3-dienes with high diastereoselectivity (dr > 20:1), enabling efficient synthesis of bioactive molecules including TRPV6 inhibitors and CFTR modulators [3]. The expanding toolkit of catalytic methodologies continues to accelerate drug discovery by providing efficient routes to complex molecular architectures.

Environmental Applications

In environmental applications, inorganic catalysts play crucial roles in emission control and pollution mitigation. Automotive catalysts, typically incorporating noble metals like platinum, palladium, and rhodium on ceramic supports, effectively reduce harmful emissions from combustion engines by promoting the conversion of carbon monoxide, unburned hydrocarbons, and nitrogen oxides to less harmful compounds [1]. The growing automotive industry, particularly the expansion of electric and hybrid vehicles, continues to drive innovation in catalytic emission control systems [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Zeolite Catalytic Activity in Hydrocarbon Cracking

Objective

To quantitatively assess the catalytic cracking performance of zeolite catalysts using model hydrocarbon compounds.

Materials and Equipment

- Zeolite catalyst (standardized particle size distribution)

- Model hydrocarbon feedstock (n-hexane, isooctane, or gas oil)

- Fixed-bed reactor system with temperature control

- Gas chromatograph with flame ionization detector (GC-FID)

- On-line product analysis system

- Mass flow controllers for feed and carrier gases

- Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) apparatus for acidity measurements

Methodology

- Catalyst Pretreatment: Activate zeolite catalyst (typically 1-2 g) under dry air flow (30 mL/min) at 500°C for 2 hours to remove moisture and contaminants.

- Reactor Loading: Load pretreated catalyst into fixed-bed reactor and establish inert atmosphere with nitrogen purge.

- Reaction Conditions: Set reactor temperature to 450-550°C and introduce hydrocarbon feedstock at weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 2-4 h⁻¹.

- Product Analysis: Direct effluent stream to GC-FID system for quantitative analysis of cracked products collected at 5-minute intervals for first hour, then 15-minute intervals for duration of experiment.

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Conversion (%) = [(Feed moles - Unreacted moles) / Feed moles] × 100

- Selectivity to product i (%) = [Moles of product i / Σ moles of all products] × 100

- Catalyst stability assessed via time-on-stream analysis over 6-24 hours

Data Interpretation

Compare product distribution patterns to determine mechanistic pathways. Higher branching ratios in C3-C5 products indicate preferential cracking at tertiary carbon positions, while light gas (C1-C2) formation suggests radical cracking mechanisms. Deactivation rates are quantified by tracking conversion decline over time.

Protocol 2: Assessing Metal Catalyst Performance in Hydrogenation Reactions

Objective

To evaluate the activity and selectivity of metal catalysts in the hydrogenation of functionalized substrates.

Materials and Equipment

- Metal catalyst (supported noble or base metal, 5-50 mg)

- Substrate solution (0.1-1.0 M in appropriate solvent)

- High-pressure batch reactor (Parr reactor or equivalent)

- Hydrogen gas supply with pressure regulation

- Magnetic stirring system with temperature control

- Sampling system with in-line filtration

- Analytical instrumentation (GC, HPLC, or NMR)

Methodology

- Catalyst Reduction: Pre-reduce catalyst under hydrogen flow (50 mL/min) at specified temperature (200-400°C) for 1-2 hours.

- Reaction Setup: Charge reactor with substrate solution and reduced catalyst, seal system, and purge with inert gas.

- Pressure and Temperature Conditions: Pressurize with hydrogen to desired pressure (1-50 bar) and heat to reaction temperature (25-150°C) with constant agitation.

- Reaction Monitoring: Collect samples at regular intervals, filter to remove catalyst particles, and analyze by appropriate chromatographic or spectroscopic methods.

- Kinetic Analysis: Determine initial reaction rates from concentration-time data and calculate turnover frequencies (TOF) based on active site quantification.

Data Interpretation

Compare hydrogenation rates across different catalyst formulations and reaction conditions. Selectivity patterns are assessed by quantifying desired product versus byproduct formation. Catalyst stability is evaluated through recyclability experiments with intermediate regeneration steps.

Experimental Workflow and Catalyst Selection Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for evaluating inorganic catalyst performance in research applications:

Experimental Workflow for Catalyst Performance Evaluation

Advanced Catalyst Technologies and Innovations

The inorganic catalyst landscape continues to evolve through technological innovations that enhance performance, sustainability, and application scope. Several emerging trends are particularly noteworthy for research professionals:

Catalyst Shaping Technology

Recent advances in catalyst manufacturing have introduced novel shaping technologies that significantly improve performance characteristics. BASF SE's X3D technology represents a groundbreaking approach utilizing additive manufacturing based on 3D printing to create catalyst structures with optimized geometry [1]. This innovation generates an open configuration that reduces pressure drop across reactors while increasing surface area, substantially enhancing catalytic performance across diverse applications including base metals, precious metal catalysts, and carrier materials [1].

Nanostructured Catalysts

The integration of nanotechnology in catalyst design has enabled unprecedented control over active site distribution and accessibility. Nanostructured catalysts featuring controlled particle sizes, morphologies, and spatial distributions demonstrate enhanced activity, selectivity, and stability compared to conventional formulations. These advanced materials particularly benefit pharmaceutical applications where precise reaction control is essential for synthesizing complex chiral molecules and therapeutic compounds [3].

Hybrid and Multifunctional Systems

The development of hybrid catalytic systems that combine multiple functional components addresses increasingly complex reaction requirements. Examples include encapsulated enzyme-metal combinations within metal-azolate frameworks (MAFs), which have demonstrated 420-fold efficiency improvements compared to conventional ZIF-8 supports while achieving 94-99% enantioselectivity in pharmaceutical precursor synthesis [3]. Such integrated systems exemplify the trend toward multifunctional catalysis that simultaneously accomplishes multiple transformation steps in streamlined processes.

Research Reagent Solutions for Catalyst Investigation

The following table details essential research reagents and materials for experimental investigation of inorganic catalysts:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Inorganic Catalyst Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Reference Standards | Benchmark materials for comparative performance testing | Petroleum cracking, shape-selective reactions | Varying Si/Al ratios, pore architectures [1] |

| Supported Metal Catalysts | Hydrogenation, oxidation, coupling reactions | Pharmaceutical intermediates, fine chemicals | Metal loading, dispersion, support composition [1] |

| Metal Oxide Powders | Acid-base catalysis, oxidation reactions | Environmental catalysis, chemical synthesis | Surface area, crystallinity, defect concentration [1] |

| Probe Molecules | Catalyst characterization and active site quantification | Acidity/basicity measurement, mechanistic studies | Thermal stability, spectroscopic properties [3] |

| Standard Reaction Feedstocks | Performance benchmarking under controlled conditions | Catalyst activity and selectivity assessment | Purity, composition reproducibility [3] |

Inorganic catalysts represent a diverse and technologically vital class of materials spanning zeolites, metals, and chemical compounds with extensive applications across petroleum refining, chemical synthesis, pharmaceutical development, and environmental protection. The continuous advancement of catalytic technologies—including novel shaping methods, nanostructured architectures, and hybrid systems—promises enhanced performance and sustainability across industrial and research domains. For drug development professionals, understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and appropriate application contexts for different catalyst categories is essential for designing efficient synthetic routes to therapeutic compounds. The experimental frameworks and performance comparisons presented in this guide provide a foundation for informed catalyst selection and optimization in research and development initiatives.

The global inorganic catalyst market represents a cornerstone of modern industrial chemistry, enabling essential processes across petroleum refining, chemical synthesis, and environmental protection. As of 2024, this market has reached a valuation of $26.81 billion, with projections indicating growth to $27.6 billion in 2025, and further expansion to $33.58 billion by 2029 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5% [2] [4]. This steady growth trajectory underscores the critical role inorganic catalysts play in global industrial systems, particularly as industries worldwide face increasing pressure to enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impact. The Asia-Pacific region has emerged as the dominant market, accounting for the largest share of global demand in 2024, driven by robust industrial expansion in China, India, and Southeast Asia [2] [4] [5].

Within the broader catalyst market, which includes both organic and inorganic variants, inorganic catalysts specifically refer to heterogeneous catalysts comprising metals and their oxides that emulate the function of natural catalysts [2]. These substances possess an inorganic structure and do not necessarily contain carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen molecules, distinguishing them from their organic counterparts. The market's growth is primarily fueled by rising demand for petroleum and petrochemical products, expansion of the automotive industry, and increasingly stringent environmental regulations worldwide [2] [4] [6]. Additionally, rapid industrialization in emerging economies, coupled with technological advancements in catalyst design, are creating new opportunities for market expansion across multiple application segments.

Market Segmentation and Quantitative Analysis

Global Market Size and Growth Projections

Table 1: Inorganic Catalyst Market Size and Growth Projections (2024-2029)

| Year | Market Size (USD Billion) | Year-over-Year Growth | CAGR Period | CAGR Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 26.81 | - | 2024-2025 | 3.0% |

| 2025 | 27.6 | 3.0% | 2025-2029 | 5.0% |

| 2029 | 33.58 | - | 2024-2029 | 4.6% |

Multiple market research analyses confirm the consistent growth pattern of the inorganic catalyst sector, with the market expected to grow from $26.81 billion in 2024 to $33.58 billion in 2029 at a CAGR of 5% [2] [4]. Another analysis projects growth from $27.99 billion in 2025 to $34.58 billion in 2029 at a slightly higher CAGR of 5.4% [6], while different methodology suggests the market size was valued at $25.50 billion in 2021 with a projected CAGR of 3.3% from 2022 to 2030 [7]. The variations in these estimates reflect differences in methodological approaches and specific inclusion criteria, but collectively they point toward sustained market expansion throughout the forecast period.

Market Segmentation Analysis

Table 2: Inorganic Catalyst Market Segmentation by Type, Process, and Application

| Segmentation Category | Sub-segments | Key Characteristics | Market Share Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Type | Zeolites | Natural and synthetic varieties; used in petroleum refining and chemical synthesis | Dominant segment due to extensive use in petroleum refining [2] [8] |

| Metals | Noble metals (platinum, palladium) and base metals (nickel, copper) | Critical for hydrogenation and oxidation reactions [2] | |

| Chemical Compounds | Metal oxides, salts, and coordination compounds | Widely used in polymerization and environmental applications [2] | |

| Other Types | Heterogeneous, homogeneous, and mixed catalysts | Growing segment with specialized applications [2] | |

| By Process | Recycling | Recovery and reuse of catalyst materials | Gaining importance due to cost and sustainability concerns [2] |

| Regeneration | Restoring catalytic activity through chemical processes | Common in petroleum refining and chemical synthesis [2] [5] | |

| Rejuvenation | Partial restoration of catalyst performance | Emerging process for extending catalyst lifespan [2] | |

| By Application | Petroleum Refining | Fluid catalytic cracking, hydrotreating, alkylation | Largest application segment [2] [8] |

| Chemical Synthesis | Production of chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and intermediates | Second largest application segment [5] | |

| Polymers and Petrochemicals | Ziegler-Natta catalysis, reaction initiation | Fast-growing segment driven by plastic demand [8] | |

| Environmental | Emission control, wastewater treatment | Most rapidly growing segment (5.8% CAGR) [5] |

The inorganic catalyst market demonstrates diverse opportunities across its various segments, with zeolites and metals representing the most significant share of the type segment [2] [8]. The petroleum refining application continues to dominate the market, driven by global demand for transportation fuels and chemical feedstocks. The environmental application segment is projected to experience the most rapid growth, with a CAGR of 5.8% attributed to increasingly stringent emissions regulations worldwide [5]. Regionally, Asia-Pacific leads the global market, accounting for approximately 35% of market share in 2024, with North America and Europe following as established markets with steady growth rates [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Inorganic Catalysts

Catalyst Performance Across Applications

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Major Inorganic Catalyst Types by Application

| Catalyst Type | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Experimental Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolites | Fluid catalytic cracking (FCC), isomerization, alkylation | High surface area, shape selectivity, thermal stability, tunable acidity | Susceptibility to coking, pore blockage, limited to specific molecule sizes | PARAGON FCC technology increases feedstock flexibility and operational window by 15-20% [2] [4] |

| Noble Metals (Pt, Pd, Rh) | Automotive catalytic converters, hydrogenation, oxidation reactions | High activity, resistance to poisoning, stability at high temperatures | High cost, limited availability, susceptibility to sulfur poisoning | Three-way catalysts reduce automotive emissions by >90% for CO, NOx, and hydrocarbons [9] [5] |

| Base Metals (Ni, Cu, Co) | Hydrotreatment, reforming, methanation | Lower cost, good activity for specific reactions, wider availability | Generally lower activity than noble metals, shorter lifespan in demanding applications | Ni-based catalysts achieve 85-95% conversion in methane reforming at 800°C [10] |

| Metal Oxides (V2O5, TiO2, MoO3) | Selective oxidation, DeNOx processes, polymerization | Tunable redox properties, acid-base characteristics, thermal stability | Can be susceptible to over-oxidation, limited selectivity in some applications | V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts achieve 80-95% NOx conversion in SCR systems between 300-400°C [10] |

| Chemical Compounds | Polymerization, specialty chemicals production | Precise control over reaction selectivity, customizable properties | Often higher cost, may require specialized handling | Ziegler-Natta catalysts produce polyolefins with controlled stereochemistry >95% isotactic index [8] |

The performance characteristics of different inorganic catalyst types vary significantly based on their composition and intended application. Zeolites demonstrate exceptional performance in petroleum refining applications due to their shape selectivity and acidic properties, with recent technological advancements such as Grace & Co.'s PARAGON FCC catalyst technology enhancing their operational flexibility and vanadium resistance [2] [4]. Noble metal catalysts continue to deliver unmatched performance in emission control applications, though their high cost drives research into alternative materials. Base metal catalysts offer a cost-effective solution for numerous industrial processes, with ongoing research focused on enhancing their activity and stability through structural modifications and promoter elements.

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Evaluation

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for meaningful comparison of inorganic catalyst performance across different studies and applications. The following section outlines key methodological approaches referenced in current research:

3.2.1 Catalyst Activity Testing Protocol Activity testing for inorganic catalysts typically follows a standardized approach utilizing fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor systems, depending on the intended application [10]. The general methodology involves loading a specific volume of catalyst into the reactor system, establishing controlled flow rates of reactant gases, and monitoring conversion and selectivity at predetermined temperature intervals. For petroleum refining catalysts such as FCC units, testing protocols involve microactivity testing (MAT) according to ASTM D3907 or similar standards, which measure catalyst performance in gas oil conversion under controlled conditions [2] [10]. Performance metrics including conversion percentage, product yield distribution, and selectivity to desired products are calculated based on detailed product analysis using gas chromatography and other analytical techniques.

3.2.2 Accelerated Deactivation Testing Evaluating catalyst stability and lifespan under accelerated conditions provides critical data for industrial applications [10]. Standard protocols involve exposing catalysts to elevated temperatures, increased contaminant levels, or cyclic reaction-regeneration conditions to simulate long-term operation in a compressed timeframe. For instance, FCC catalyst testing might involve repeated cycles of reaction and regeneration in the presence of vanadium and nickel contaminants to assess metal tolerance [2]. Characterization of spent catalysts using techniques such as temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) for coke quantification, BET surface area analysis, and XRD for structural changes provides insights into deactivation mechanisms and facilitates comparison of catalyst durability across different formulations.

3.2.3 Selectivity Assessment Methodologies Determining catalyst selectivity for specific desired products requires precise analytical methods and controlled reaction conditions [10]. For zeolite catalysts in chemical synthesis applications, selectivity testing typically involves monitoring product distribution from model compound reactions under standardized conditions. In metal-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions, selectivity assessment focuses on quantifying desired product formation versus over-hydrogenation byproducts. Advanced characterization techniques including in-situ spectroscopy (IR, Raman, XAS) and isotopic labeling experiments provide mechanistic insights that complement performance data, enabling rational design of more selective catalyst systems [11] [10].

Advanced Catalyst Technologies and Research Directions

Emerging Catalyst Technologies

The inorganic catalyst landscape is evolving rapidly through technological innovations that enhance performance, sustainability, and economic viability. Major players in the market are investing significantly in research and development to create advanced catalyst systems with improved characteristics:

4.1.1 Advanced Catalyst Structuring Technologies Recent breakthroughs in catalyst structuring are enabling significant improvements in performance metrics. BASF's X3D technology, launched in 2022, represents a revolutionary approach to catalyst shaping through additive manufacturing processes based on 3D printing [2] [4]. This technology creates catalysts with open structures that result in lower pressure drop across reactors and higher surface area, considerably boosting catalytic performance. The technology can be applied to a wide range of existing catalytic materials, including base or precious metal catalysts and carrier materials, offering compatibility with existing industrial processes while delivering enhanced efficiency.

4.1.2 Hybrid Organic/Inorganic Catalyst Systems An emerging frontier in catalyst design involves the development of hybrid organic/inorganic materials that combine the stability of inorganic components with the tunable functionality of organic modifiers [11]. These systems contain inorganic components that serve as sites for chemical reactions and organic components that provide diffusional control or directly participate in the formation of active site motifs. These hybrid materials show promise in controlling reaction selectivity by modifying scaling relations in adsorption and transition energies, potentially enabling more efficient catalytic processes for energy and environmental applications, including the challenging conversion of methane to methanol under mild conditions [11].

4.1.3 Nanostructured Catalyst Materials Advances in nanotechnology are enabling precise control over catalyst architecture at the nanoscale, leading to enhancements in activity, selectivity, and stability [2] [9]. Nanostructured catalysts with controlled size, shape, and composition offer increased surface-to-volume ratios and unique electronic properties that can significantly improve catalytic performance. For example, precisely engineered metal nanoparticles on tailored supports demonstrate enhanced activity in hydrogenation reactions, while nanostructured zeolites with hierarchical pore systems overcome diffusion limitations in processing bulky molecules, expanding their application in heavy oil upgrading and biomass conversion [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for Catalyst Development

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Inorganic Catalyst Studies

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Catalyst Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Materials | Alumina, silica, titania, zeolites, carbon nanotubes | Provide high surface area for active component dispersion, influence metal-support interactions | Catalyst carrier systems for petroleum refining, environmental catalysis [10] |

| Active Metal Precursors | Metal salts (chlorides, nitrates, acetates), organometallic compounds | Source of catalytic active sites after appropriate treatment (calcination, reduction) | Preparation of metal-based catalysts for hydrogenation, oxidation reactions [10] |

| Promoter Compounds | Rare earth elements, alkali metals, alkaline earth metals | Modify electronic or structural properties of catalysts, enhance activity/selectivity/stability | FCC catalyst formulations (rare earth), synthesis gas conversion catalysts [2] |

| Probe Molecules | CO, NH3, pyridine, NO, H2 | Characterization of acid-base and redox properties through chemisorption and spectroscopy | Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD), IR spectroscopy studies [10] |

| Structural Directing Agents | Quaternary ammonium compounds, surfactants, polymers | Control pore architecture and crystal morphology during synthesis | Zeolite and mesoporous material synthesis [10] |

The development and evaluation of advanced inorganic catalysts require specialized reagents and materials that enable precise control over composition, structure, and properties. Support materials form the foundation of many heterogeneous catalyst systems, providing the necessary surface area and porosity to disperse active components effectively [10]. Active metal precursors in various forms allow researchers to tailor the nature and density of catalytic sites, while promoter compounds offer pathways to enhance specific catalyst properties that cannot be achieved through primary components alone. Probe molecules serve as essential diagnostic tools for characterizing catalyst properties, and structural directing agents enable the synthesis of tailored porous architectures with controlled accessibility and molecular transport properties.

Future Outlook and Research Opportunities

The inorganic catalyst market continues to evolve in response to technological advancements, changing regulatory landscapes, and shifting industry demands. Several key trends are expected to shape the future development of this sector:

The transition toward sustainable and circular economy principles is driving research into catalysts designed for recycling and regeneration, with the processes segment showing increasing importance in catalyst lifecycle management [2] [5]. Concurrently, the integration of digital technologies including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and high-throughput computational screening is accelerating catalyst discovery and optimization processes, reducing development timelines and enhancing performance prediction accuracy [8]. The growing emphasis on environmental applications continues to create opportunities for advanced catalyst systems capable of addressing emerging pollution challenges and enabling carbon capture and utilization technologies [10] [5].

The expansion of renewable energy and feedstock systems is generating demand for catalysts tailored to biomass conversion, water splitting, CO2 utilization, and hydrogen production [11] [10]. Additionally, advanced characterization techniques with spatial and temporal resolution are providing unprecedented insights into catalyst structure-performance relationships, enabling more rational design approaches [11] [10]. These developments collectively point toward a future where inorganic catalysts will play an increasingly sophisticated role in enabling sustainable chemical processing, clean energy systems, and environmental protection technologies across global industrial sectors.

The rational design and selection of high-performance inorganic catalysts are fundamental to advancements in chemical synthesis, energy technologies, and environmental protection. The catalytic performance of these materials is intrinsically governed by their acid-base and redox characteristics. Acid-base properties determine a catalyst's ability to donate or accept protons, facilitating key reactions such as hydrolysis, dehydration, and isomerization. Redox properties, on the other hand, govern the transfer of electrons, which is central to oxidation and reduction processes. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major inorganic catalyst classes—solid acids/bases, metal oxides, and redox-active metals—by synthesizing experimental data on their intrinsic properties, performance, and applications. It is structured to serve as a reference for researchers and development professionals in selecting and characterizing catalysts for specific industrial and synthetic processes, framed within the broader context of inorganic catalyst performance comparison research.

Comparative Analysis of Acid-Base Properties

The acid-base character of a catalyst is a primary determinant of its function in reactions involving proton transfer. The Brønsted-Lowry theory defines an acid as a proton (H⁺) donor and a base as a proton acceptor [12] [13]. In catalysis, this can manifest as specific acid-base catalysis, where the reaction rate depends only on the pH, or general acid-base catalysis, where all species capable of donating or accepting protons contribute to the rate acceleration [14] [12]. The following table summarizes the acid-base properties of key material classes, with data drawn from experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Acid-Base Properties of Key Catalyst Classes

| Material Class | Specific Examples | Intrinsic Acidic/Basic Sites | Measured Properties / Experimental Data | Primary Catalytic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolites & Aluminosilicates | Zeolite Beta, ZSM-5, MCM-41, Sandstone, Clay | Acidic: Bridged Brønsted acid sites (Si-OH-Al), Lewis acid sites (framework Al) | - Surface Area (BET): 15-25 m²/g (natural clay) [15]- Acid Site Strength: Medium to strong Brønsted acidity- Composition: ~56-65 wt% Si, ~8-9 wt% Al (in clay) [15] | Fluid catalytic cracking (FCC), alkylation, isomerization |

| Single/Mixed Metal Oxides | γ-Al₂O₃, ZrO₂ (Zirconia), SiO₂-Al₂O₃ | Amphoteric: Surface -OH groups (Brønsted sites), coordinatively unsaturated metal cations (Lewis acid sites), O²⁻ anions (basic sites) | - Surface Area (BET): High (>100 m²/g common for synthetics)- Acid/Base Strength: Tunable from weak to strong; ZrO₂ exhibits bifunctional acid-base properties [14] | Dehydration, CO₂ activation for oxidative dehydrogenation [14] |

| Supported Mineral Matrices | Basalt, Clay, Sandstone | Acidic/Basic: Variable; primarily Lewis acidity from transition metal impurities (Fe, Ti), with basicity from alkali/alkaline earth metals | - Surface Area (BET): 15-25 m²/g [15]- Elemental Composition: 2.75-3.3 wt% Fe, 0.3-0.4 wt% Ti (in basalt/clay) [15]- pKa of G2(N7)H⁺: ~2.44 (in a hexa-2'-deoxynucleoside pentaphosphate model) [16] | In-situ heavy oil upgrading, hydrocracking of asphaltenes [15] |

| Solid Brønsted Acids | Heteropoly acids (e.g., H₃PW₁₂O₄₀), Sulfonated polymers, Sulfated zirconia | Acidic: Strong, mobile Brønsted protons | - Acid Strength: Very strong (superacids possible)- Proton Mobility: High | Esterification, transesterification (e.g., biodiesel production), alkylation [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Acid-Base Characterization

A combination of techniques is required to fully characterize the acid-base properties of solid catalysts. The following are standard experimental protocols cited in research.

- Gas Sorption Analysis (BET Method): This protocol is used to determine the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of a catalyst, which directly influences the accessibility of active sites [15].

- Methodology: A sample is first degassed under vacuum at elevated temperature (e.g., 300°C) to remove adsorbed contaminants. The sample is then cooled to cryogenic temperature (typically 77 K, using liquid nitrogen), and the volume of nitrogen gas adsorbed at a series of relative pressures is measured. The data is analyzed using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory to calculate the specific surface area and other textural properties [15].

- Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD): This method probes the strength and distribution of acid or base sites on a catalyst surface.

- Methodology (for Ammonia TPD): The catalyst sample is pre-treated under an inert gas flow at high temperature to clean the surface. It is then saturated with an alkaline probe molecule like ammonia (for acidity) or an acidic probe like carbon dioxide (for basicity). Physically adsorbed molecules are removed by purging with an inert gas. The temperature is then increased in a controlled linear ramp while the desorption of the probe molecule is monitored using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The temperature of desorption peaks indicates the strength of the sites, and the area under the peaks corresponds to their concentration.

- Potentiometric Titration with Ion-Selective Electrode: This technique is used to study acid-base equilibria and determine pKa values in solution, which can be applied to molecular catalysts or the dissolved products of surface reactions.

- Methodology: As described in a study on ammonium nitrate decomposition, a thermostatic reactor equipped with a reflux condenser and a magnetic stirrer is used [15]. The working solution containing the acidic/basic species is prepared. An ion-selective electrode (e.g., for ammonium ions) and a reference electrode (e.g., silver chloride) are immersed in the solution. The concentration of the target ion is monitored in real-time using a universal ionometer as the pH is changed or as a reaction proceeds, allowing for the calculation of acidity constants [15].

Comparative Analysis of Redox Characteristics

Redox catalysis involves the transfer of electrons between the catalyst and reactant molecules, often cycling through different oxidation states. This is crucial for reactions such as oxidations, reductions, and epoxidations [17]. The activity of materials for reactions like oxygen evolution is attributed to their ability to participate in surface redox catalysis, where a metal ion is oxidized to a higher, more electron-attractive valence state [17]. The table below compares the redox features of several important catalytic classes.

Table 2: Comparative Redox Properties of Key Catalyst Classes

| Material Class | Specific Examples | Redox-Active Components | Measured Properties / Experimental Data | Primary Catalytic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titanosilicates | TS-1, Ti-MCM-41, Ti-HMS, Ti-SBA-15 | Framework Ti⁴⁺ | - Oxidation State: Ti⁴⁺/Ti³⁺ cycle- Pore Size: Microporous (TS-1, ~0.55 nm) vs. Mesoporous (Ti-MCM-41, ~2-10 nm)- Activity: High selectivity for epoxidation with H₂O₂; Ti-MCM-41 effective for larger substrates like 2,6-DTBP [17] | Selective oxidation with H₂O₂ (e.g., propene epoxidation), hydroxylation of benzene |

| Transition Metal Oxide Catalysts | V₂O₅, MoO₃, Co₃O₄, MnO₂ | V⁵⁺, Mo⁶⁺, Co³⁺, Mn⁴⁺ (and other lower states) | - Multiple Oxidation States: Accessible and stable- Redox Thermostability: High under reaction conditions | Ammoxidation, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx, total oxidation |

| Noble Metal & Complexes | Pt/γ-Al₂O₃, Pd complexes, Chiral Mn(III) salen | Pt²⁺/Pt⁰, Pd²⁺/Pd⁰, Mn³⁺/Mn²⁺ | - Pt Effect on Purine pKa: (dien)Pt²⁺ coordination to N7 acidifies the (N1)H⁺ site, demonstrating metal-proton reciprocal acidification [18]- Immobilized Mn-salen ee: 68-71% for styrene epoxidation [17] | Exhaust catalysis (CO and hydrocarbon oxidation), enantioselective epoxidation, aerobic oxidation of alcohols |

| Natural Mineral Matrices | Basalt, Iron/Clay | Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺, Ti⁴⁺/Ti³⁺ impurities | - Composition: 2.75-3.3 wt% Fe as Fe₂O₃ in basalt/clay [15]- Activity: Catalytic activity observed in hydrocracking of asphaltenes and oxidation of CO/hydrocarbons [15] | In-situ oil upgrading, hydrocracking, oxidation reactions |

Experimental Protocols for Redox Characterization

Evaluating the redox performance and stability of a catalyst requires specific experimental setups that simulate process conditions.

- Catalytic Activity Testing in a Flow Reactor: This is a standard method for assessing redox activity in gas-solid heterogeneous catalysis, particularly for oxidation reactions [15].

- Methodology: A fixed mass of catalyst (e.g., 1.0 g) is placed in a tubular flow reactor. A gas mixture with precisely controlled concentrations of the reactant (e.g., 1.0 vol% methane), oxidant (e.g., 10 vol% oxygen), and an inert balance gas (e.g., nitrogen) is passed through the catalyst bed at a defined flow rate (e.g., 2.4 L/h). The reactor temperature is controlled, often within a range of 623–873 K. The composition of the effluent gas stream is analyzed in real-time using gas chromatography (GC) to determine conversion of the reactant and selectivity to desired products [15].

- Microreactor System for Hydrocracking: This protocol is used for liquid-phase redox reactions under pressure, such as the hydrocracking of heavy hydrocarbons.

- Methodology: As employed in studying asphaltene hydrocracking, a small-scale (e.g., 50 ml) autoclave reactor made of a chemically stable alloy (e.g., Hastelloy) is used [15]. The initial compound (e.g., asphaltenes) is loaded with the catalyst. The reactor is pressurized with hydrogen to the desired pressure (e.g., 1.0 MPa) and heated to the reaction temperature (e.g., 473–573 K) with controlled stirring. After the reaction, the products are separated and analyzed gravimetrically (e.g., into toluene-soluble asphaltenes and n-heptane-soluble maltenes) or via chromatography to assess conversion and selectivity [15].

- Electrochemical Characterization for Redox Catalysis: This is used to determine the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of molecular redox catalysts, especially those relevant to energy conversion.

- Methodology: The catalyst is immobilized on an electrode surface or dissolved in the electrolyte. Techniques such as cyclic voltammetry (CV) are employed. By analyzing the shape of the voltammogram (e.g., peak potentials and currents) under varying conditions, key parameters like turnover frequency, overpotential, and catalytic efficiency can be determined [17].

Visualization of Relationships and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core conceptual relationships between catalyst properties and function, as well as a generalized experimental workflow for catalyst evaluation.

Catalyst Property-Performance Relationship

(Diagram 1: The interrelationship between intrinsic catalyst properties, the techniques used to characterize them, and the resulting catalytic performance metrics.)

Catalyst Evaluation Workflow

(Diagram 2: A generalized experimental workflow for the synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation of catalysts.)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, materials, and instrumentation essential for research in the field of acid-base and redox catalysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Molecules for Sorption | To characterize surface area, pore size, and acid-base properties. | - N₂ (77 K): BET surface area and porosity [15].- NH₃ / CO₂: Acid/Base site strength and concentration via TPD. |

| Standard Redox Catalysts | As benchmark materials for performance comparison in oxidation/reduction reactions. | - Pt/γ-Al₂O₃: Benchmark for CO oxidation [15].- TS-1: Benchmark for H₂O₂-propene epoxidation [17]. |

| High-Pressure Autoclave Reactors | For conducting liquid-phase reactions under controlled pressure and temperature (e.g., hydrocracking, hydrogenation). | - Material: Hastelloy C-276 for corrosion resistance [15].- Application: Hydrocracking of asphaltenes at 1.0 MPa H₂ pressure [15]. |

| In-Situ Spectroscopic Cells | For real-time monitoring of reactions on catalyst surfaces to identify intermediates and mechanisms. | - DRIFTS (Diffuse Reflectance IR): To monitor surface species.- In-Situ XRD: To track structural changes under reaction conditions. |

| Ion-Selective Electrodes | For precise potentiometric determination of specific ion concentrations in solution-phase studies. | - Application: Monitoring NH₄⁺ concentration during ammonium nitrate decomposition studies [15]. |

| Model Compound Feedstocks | Well-defined reactants for standardized testing of catalyst activity, selectivity, and stability. | - For Redox: Methane, carbon monoxide for oxidation tests [15].- For Acid-Base: Ethylbenzene for dehydrogenation with CO₂ [14]. |

Inorganic catalysts, composed of metals, oxides, or sulfides, are fundamental to modern industrial processes, accelerating reaction rates without being consumed to ensure cost-effective and sustainable operations. [19] They play critical roles in petrochemicals, energy, automotive, and pharmaceutical sectors, contributing to both economic and environmental objectives. The global inorganic catalyst market, valued at US$28 billion in 2024, is projected to reach US$31.7 billion by 2030, driven by rising energy demands, stringent environmental regulations, and technological advancements. [19] Within this landscape, BASF, Johnson Matthey, and Clariant have emerged as dominant innovators, each developing specialized catalyst technologies that address complex industrial challenges across various applications.

Company-Specific Catalyst Technologies and Applications

BASF SE

BASF provides a diverse portfolio of catalytic technologies across multiple segments, leveraging its global scale and extensive research capabilities. The company's product offerings are categorized into several key business units:

- Environmental Catalyst and Metal Solutions (ECMS): This standalone entity provides catalysis and precious metals services to various industries, offering full-loop services through precious metals trading and recycling. [20]

- Chemical Catalysts and Adsorbents: As a global leader in chemical catalysts, BASF develops cutting-edge catalyst chemistry focused on customer-specific needs. [20]

- Refinery Catalysts: The company's Fluid Catalytic Cracking (FCC) catalysts and additives, combined with technical services, create value within refinery unit constraints. [20]

- Battery Materials: BASF develops innovative materials for current and next-generation lithium-ion batteries and future battery systems. [20]

BASF has particular strength in sulfuric acid catalysts, having invented the vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) catalyst in 1913. [21] The company operates its own acid plants, providing unique operational understanding that informs catalyst development for superior physical and chemical properties ensuring long-lasting, high performance. [21]

Johnson Matthey

Johnson Matthey specializes in advanced catalytic technologies for chemical synthesis and emission control, with particular expertise in large-scale industrial processes. The company's innovations focus on enhancing efficiency, durability, and sustainability in demanding applications.

A significant recent development is the KATALCO 71-7F catalyst for high-temperature shift (HTS) reactions in ammonia production. [22] This catalyst features an innovative 'F' shape designed to provide lower lifetime pressure drop, enabling large-scale plants to increase ammonia production capacity. [22] Johnson Matthey's HTS catalysts benefit from improved intimacy between Fe₃O₄ active sites and chromium/copper promoters, which stabilizes the active species responsible for catalyzing the water-gas shift reaction. [22]

The company also maintains a strong position in the industrial rare earth denitrification catalyst market, developing technologies that utilize rare earth metals like cerium and lanthanum to boost conversion efficiency and operational stability in meeting stringent NOx emission regulations. [23]

Clariant

Clariant has established itself as an independent provider of specialized catalytic solutions across multiple domains, with particularly strong offerings in purification and hydrogenation processes. The company's R&D efforts focus on developing tailored solutions for specific industrial challenges.

In feed purification, Clariant provides optimized catalysts and adsorbents for removing impurities from feed gases used in sustainable fuel and chemical production. [24] Their comprehensive portfolio includes:

- ActiSorb series: Guard bed catalysts for removing contaminants like chlorides (ActiSorb Cl 2), mercury (ActiSorb Hg 1), and metal carbonyls (ActiSorb 400/410). [24]

- HDMax series: Hydrodesulfurization catalysts for removing sulfur from hydrocarbon feedstocks. [24]

- ShiftMax series: Water-gas shift catalysts for syngas conditioning, including high-temperature and sour-gas shift applications. [24]

In hydrogenation processes, Clariant offers four distinct catalyst families: [25]

- NiSat: Nickel-based catalysts for hydrogenation, hydro-finishing, and fuel upgrading

- HyMax: Copper-chromite catalysts for selective conversion of aldehydes, ketones, or esters to alcohols

- HySat: Sustainable chromium-free copper catalysts as environmentally responsible alternatives

- HyFlex: Precious-metal and base-metal catalysts for specialty chemical hydrogenation

Clariant also participates in the complex iron desulfurization catalyst market, providing solutions for ultra-low sulfur fuels in petroleum refining and natural gas processing. [26]

Comparative Performance Analysis

High-Temperature Shift Catalysts: Johnson Matthey vs. Clariant

The high-temperature shift (HTS) reaction is crucial in ammonia, hydrogen, and methanol production processes, where catalyst durability and pressure drop characteristics significantly impact operational efficiency and productivity.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of High-Temperature Shift Catalysts

| Catalyst | Manufacturer | Key Features | Performance Advantages | Tested Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KATALCO 71-7F | Johnson Matthey | Innovative 'F' shape; Improved Cr promoter intimacy with Fe₃O₄ sites | Lower lifetime pressure drop; Superior strength after thermal ageing; Withstands demanding duty cycles | Large-scale ammonia plants (3,300 t/d) |

| KATALCO 71-6F | Johnson Matthey | Advanced pore network; Enhanced shape design | Excellent durability in large plants; Reduced pressure drop vs. previous generations | Large-scale ammonia plants with demanding duties |

| ShiftMax 120 HCF | Clariant | Virtually no hexavalent chromium (Cr⁶⁺); Combined high activity & thermal stability | Withstands boiler leakages; Eliminates health risks in handling | Hydrogen production units |

Experimental Protocol for HTS Catalyst Evaluation: Catalyst strength was measured before and after representative thermal ageing to simulate "regular" durability requirements for HTS catalysts. [22] Additional "steaming" ageing tests were conducted to represent more demanding duty cycles where catalysts are exposed to steam during reactor start-up. [22] Long-term durability was assessed using accelerated ageing conditions with multiple ageing cycles, comparing performance retention across different catalyst generations. [22]

For a 3,300 t/d ammonia plant, Johnson Matthey calculates that the 0.10 bar pressure drop benefit provided by KATALCO 71-7F translates to approximately 8.9 t/d of extra ammonia production, potentially generating up to $1.5 million in extra annual sales based on specific economic assumptions. [22]

Sulfuric Acid Catalysts: BASF vs. Haldor Topsoe

Sulfuric acid production represents another domain where catalyst performance significantly impacts plant efficiency, emission control, and operational costs.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Sulfuric Acid Catalysts

| Catalyst | Manufacturer | Key Features | Performance Advantages | Environmental Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VK38+ | Haldor Topsoe | Potassium-promoted; Daisy shape design | Higher activity without compromising strength; Works in all SO₂ converter beds | ~35% emission reduction; ~50% less catalyst waste |

| Vanadium Pentoxide (V₂O₅) | BASF | Traditional formulation; BASF inventor in 1913 | Superior physical/chemical properties; Long-lasting performance | Proven emission control capabilities |

Experimental Protocol for Sulfuric Acid Catalyst Evaluation: Conversion efficiency was measured at different catalyst volumes to determine the relationship between catalyst volume and achievable conversion rates. [27] Testing evaluated the capacity for higher SO₂ strength operation and its impact on energy consumption and CO₂ emissions. [27] Lifetime assessments compared operational duration before activity falls below levels required to meet emission targets. [27]

In a 1,000 t/d sulfur-burning sulfuric acid plant in Sweden, implementation of VK38+ enabled operation with unprecedented SO₂ concentration levels while maintaining higher conversion rates than previous catalyst charges. [27] The higher performance translated to potentially 50% longer catalyst lifetime or up to 5% higher capacity. [27]

Denitrification Catalysts: Comparative Market Position

All three companies maintain significant presence in the denitrification catalyst market, particularly for industrial applications requiring NOx reduction.

Table 3: Denitrification Catalyst Capabilities

| Company | Key Technologies | Market Position | Specialized Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BASF | Rare earth denitrification catalysts | Industry leader with broad portfolio | Environmental applications across industries |

| Johnson Matthey | Rare earth denitrification catalysts | Leading innovator focused on R&D | Large-scale industrial denitrification |

| Clariant | EnviCat series for emission control | Specialist in tailored solutions | Nitrous oxide (N₂O) removal from nitric acid plants |

The industrial rare earth denitrification catalyst market is characterized by advancements in formulations utilizing cerium, lanthanum, and other rare earth oxides to enhance thermal resilience and reduce reactor pressure drops. [23] Recent innovations include iron-cerium composite catalysts for selective catalytic reduction systems and samarium-doped zeolite supports to enhance catalyst lifespan in nitrogen oxide removal applications. [23]

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

Technological Advancements in Catalyst Design

The inorganic catalyst sector is experiencing transformative changes driven by several technological innovations:

- Nanotechnology Integration: Nano-engineered catalysts with increased surface area and enhanced reactivity provide superior performance in energy-intensive processes, reducing energy consumption and operational costs. [19]

- Computational Modeling and AI: Machine learning algorithms simulate catalytic reactions at molecular levels, accelerating discovery of novel catalysts with improved properties and reducing reliance on expensive scarce metals. [19]

- Advanced Manufacturing: Additive manufacturing, including 3D printing, facilitates production of complex catalyst structures with enhanced functionality in industrial processes. [19]

- Hybrid Organic/Inorganic Materials: Emerging research explores hybrid catalysts containing both inorganic components (as reaction sites) and organic components (providing diffusional control or participating in active site formation) to control reaction selectivity. [11]

Sustainability-Driven Innovation

Environmental regulations and sustainability goals are reshaping catalyst development priorities across the industry:

- Chromium-Free Formulations: Clariant's introduction of HySat 320, a robust chromium-free catalyst solution, aligns with broader sustainability goals without sacrificing performance in hydrogenation processes. [25]

- Carbon Capture and Utilization: Clariant's wide range of adsorbents and catalysts enable optimized systems for carbon dioxide purification in CCUS applications. [24]

- Energy Efficiency Enhancement: Haldor Topsoe's EARTH technology, a drop-in assembly for reformer tubes, increases catalyst activity and heat recovery while minimizing energy consumption and CO₂ emissions (>30% fuel savings and >10% decreased CO₂ footprint). [24]

- Circular Economy Integration: BASF's Environmental Catalyst and Metal Solutions unit provides full-loop services through precious metals trading and recycling, supporting circular economy principles in catalytic applications. [20]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Catalyst Evaluation

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Performance Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function in Evaluation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ActiSorb Cl 2 | Removes HCl from hydrogen-rich gas streams | Prevents poisoning of downstream catalysts in steam reforming units [24] |

| Sorbead Adsorbents | Desiccants for natural gas drying | Hydrocarbon gas processing and purification [21] |

| Selexsorb CD & CDX | Selective adsorption of contaminants | Industrial gas treatment in refining, food processing, semiconductors [21] |

| Molecular Sieves (3A, 4A, 5A) | Selective adsorption based on molecular size | Gas separation and purification processes [21] |

| VK38+ Catalyst | SO₂ oxidation in sulfuric acid production | High-efficiency sulfuric acid plants with lower emissions [27] |

| KATALCO 71-7F | High-temperature shift reaction | Ammonia production plants seeking lower pressure drop [22] |

| HySat 320 | Chromium-free hydrogenation | Sustainable chemical production without chromium [25] |

HTS Catalyst Testing Methodology

BASF, Johnson Matthey, and Clariant each bring distinct strengths and specialized technologies to the global inorganic catalyst market. BASF leverages its extensive portfolio and historical expertise in chemical catalysis across multiple industrial segments. Johnson Matthey demonstrates exceptional capability in developing highly durable, efficiency-focused catalysts for large-scale applications like ammonia production. Clariant excels in providing tailored purification and hydrogenation solutions with increasing emphasis on sustainable chemistry.

The competitive landscape continues to evolve as these companies invest in R&D, form strategic partnerships, and adapt to changing regulatory requirements and market dynamics. Future success will depend on their ability to innovate in response to emerging trends, particularly the growing emphasis on environmental sustainability, circular economy principles, and digitalization of catalyst design processes.

Inorganic catalysts are fundamental substances that accelerate chemical reactions without being consumed in the process, playing a pivotal role in modern industrial operations [28]. The performance and adoption of these catalysts are primarily driven by three powerful, interconnected global forces: the robust demand for petrochemical products, the expansive growth of the automotive industry, and increasingly stringent environmental regulations. These drivers not only dictate the volume of catalyst consumption but also steer the trajectory of research and innovation within the field. This guide provides a comparative analysis of inorganic catalyst performance across these key industrial domains, presenting structured data, experimental protocols, and essential research tools to support scientific and developmental professionals in navigating this dynamic landscape.

Quantitative Analysis of Market Drivers

The demand for inorganic catalysts is directly correlated with the growth and regulatory shifts in its primary end-use industries. The tables below synthesize key quantitative data to illustrate the scale and impact of these primary drivers.

Table 1: Global Market Outlook for Inorganic Catalysts (2024-2030+)

| Market Metric | 2024 Baseline | 2029 Forecast | 2030+ Forecast | Key Growth Trends (CAGR) | Primary Driver Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Catalyst Market [1] [2] | $26.81 - $27.6 Billion | $33.58 - $34.58 Billion | ~$19.3 - $27.4 Billion by 2030 [9] | 5.0% - 5.4% CAGR (2024-2029) | Combined effect of all three drivers |

| Petrochemical Market [29] [30] | $645.7 - $700.1 Billion | ~$971.2 Billion by 2033 | $1,193.26 Billion by 2034 [29] | 4.6% - 6.11% CAGR | Rising demand for polymers and derivatives |

| Automotive (EV Sales) [1] | >10 Million Units (2022) | 14 Million Units (2023) | N/A | 35% YoY Growth (2022-2023) | Push for cleaner emissions and efficient operation |

Table 2: Catalyst Market Segmentation and Key Drivers

| Segment | Dominant Catalyst Type | Market Size / Share | Application & Function | Driver Linkage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petroleum Refining [1] [28] | Zeolites (FCC) | Dominant Application Segment [28] | Fluid Catalytic Cracking to produce fuels | Petrochemical Demand |

| Environmental [1] [31] | Noble Metals (Pt, Pd, Rh) | 36.2% share of catalyst market [31] | Automotive catalytic converters for emission control | Environmental Regulations / Automotive Expansion |

| Polymers & Petrochemicals [1] [2] | Zeolites, Metals, Chemical Compounds | Core Application Segment | Chemical synthesis for plastics and materials | Petrochemical Demand |

| Chemical Synthesis [1] [31] | Heterogeneous Catalysts | 73.6% share by type [31] | Enabling diverse industrial chemical production | Industrial Growth & Environmental Regulations |

Comparative Experimental Analysis of Inorganic Catalysts

Evaluating catalyst performance requires standardized tests that simulate industrial conditions. The following section outlines a generalizable experimental protocol and presents comparative performance data for common inorganic catalysts.

Generalized Experimental Protocol for Catalyst Evaluation

Objective: To quantitatively compare the activity, selectivity, and stability of inorganic catalysts under controlled conditions relevant to industrial applications.

Methodology:

- Catalyst Preparation: Secure commercial samples or synthesize catalysts (e.g., Zeolite Y, Pt/Al₂O₃, and a mixed metal oxide). For supported catalysts, the impregnation method is standard. Pre-treatment typically involves calcination in air (e.g., 500°C for 4 hours) followed by in-situ reduction in H₂ (e.g., 400°C for 2 hours) prior to reaction [28].

- Reactor System Setup: Employ a fixed-bed flow reactor system constructed with inert materials (e.g., stainless steel). The system must include mass flow controllers for gases, a liquid feed pump for reactants, a temperature-controlled furnace, and a downstream analysis system (e.g., an online Gas Chromatograph (GC) with appropriate columns and detectors) [28].

- Performance Testing (Activity & Selectivity):

- Load a known mass of catalyst into the reactor.

- Establish reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, feed flow rate) specific to the process being modeled (e.g., cracking, oxidation).

- After system stabilization, sample the effluent stream and analyze composition via GC.

- Calculate key metrics:

- Conversion (%) = (Moles of reactant consumed / Moles of reactant fed) × 100

- Selectivity (%) = (Moles of desired product formed / Moles of reactant consumed) × 100

- Yield (%) = Conversion × Selectivity

- Stability Testing: Operate the catalyst under constant conditions for an extended period (e.g., 100 hours). Monitor conversion and selectivity at regular intervals to assess deactivation rate.

- Post-Reaction Characterization: Use techniques like Surface Area and Porosity Analysis (BET), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) on spent catalysts to study changes in physical structure and coke deposition.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes hypothetical but representative performance data for different catalyst types, based on insights from the market reports which indicate their dominant applications.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Inorganic Catalysts in Key Applications

| Catalyst Type | Target Reaction | Typical Operating Conditions | Conversion (%) | Selectivity to Target Product (%) | Key Stability Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolite (FCC) [28] [30] | Gasoil Cracking | 500-550°C, Fluidized Bed | High (80-95) | Moderate (70-85) | Coke deposition, dealumination |

| Pt-Pd-Rh (Automotive TWC) [31] | CO/NOx Oxidation/Reduction | 400-600°C, Exhaust Stream | High (>90 at light-off) | High (>95 for N₂) | Thermal sintering, poison (e.g., S) |

| Mixed Metal Oxides [1] [28] | Selective Oxidation | 300-450°C, Fixed Bed | Moderate to High (60-90) | Variable, can be Very High (>90) | Over-oxidation, phase change |

| Base Metal (e.g., Ni) [28] | Hydrogenation | 150-300°C, Fixed Bed | High (80-95) | High (85-98) | Sulfur poisoning, sintering |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for catalyst evaluation, outlining the sequence from preparation to final characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials and their functions for researchers conducting experiments in inorganic catalyst development and testing.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Powders (e.g., ZSM-5, Zeolite Y) [1] | Acid catalyst for cracking, isomerization, and alkylation reactions. High surface area and tunable acidity. | Zeolite Y is the primary catalyst for Fluid Catalytic Cracking (FCC) in refineries, valued for its microporous structure and strong acid sites [1]. |

| Precious Metal Salts (e.g., H₂PtCl₆, PdCl₂) [31] | Precursors for synthesizing supported noble metal catalysts (Pt, Pd, Rh) used in emission control and hydrogenation. | Chloroplatinic acid is a common precursor for impregnating Pt onto alumina supports for automotive catalytic converters [31]. |

| Metal Oxide Carriers (e.g., γ-Al₂O₃, SiO₂, TiO₂) [28] | High-surface-area supports to disperse and stabilize active metal components, providing mechanical strength. | Gamma-alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) is widely used due to its high surface area, thermal stability, and controllable pore structure [28]. |

| Base Metal Precursors (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂, Co(NO₃)₂) [28] | Cost-effective alternatives to noble metals for hydrogenation, reforming, and other reduction-oxidation reactions. | Nickel nitrate is used to prepare nickel-based catalysts for methanation and steam reforming processes [28]. |

| Gaseous Reactants (Calibration Mixtures) | High-purity gases (H₂, N₂, O₂, CO, NOx, SO₂) for reaction studies, catalyst activation, and simulating industrial feedstocks. | A 10% CO / 90% N₂ mixture is used in laboratory tests to simulate automotive exhaust and evaluate three-way catalyst (TWC) performance [31]. |

The interplay between petrochemical demand, automotive expansion, and environmental regulations creates a complex and dynamic environment for inorganic catalyst research and development. The quantitative data and comparative analysis presented in this guide underscore that while zeolites and precious metals currently dominate specific high-volume applications, innovation is continuous. Advancements in nanotechnology, catalyst shaping technologies like 3D printing [2], and the integration of AI in development [28] are pushing the boundaries of catalytic performance. For researchers and industry professionals, success hinges on a deep understanding of these industrial drivers and a rigorous, data-driven approach to catalyst evaluation, as outlined in the provided experimental protocols and research toolkit.

Industrial Deployment and Performance Metrics in Key Sectors

In the field of inorganic catalysis, quantifying performance is paramount for both fundamental research and industrial application. The efficacy of a catalyst is fundamentally governed by three core metrics: activity, selectivity, and lifetime [32]. These benchmarks provide a standardized framework for comparing diverse catalytic systems, from traditional metal oxides to advanced single-atom catalysts (SACs).

Activity refers to the catalyst's ability to increase the rate of a chemical reaction, often measured by turnover frequency (TOF), which is the number of reaction cycles per catalyst site per unit time [32]. Selectivity defines the catalyst's ability to direct a reaction toward a desired product, especially when multiple products are possible from the same reactants [32]. For instance, the same reactants (CO and H₂) can yield methane (with a Ni catalyst), methanol (with Cr oxide/Zn oxide), or formaldehyde (with Cu) [32]. Lifetime measures the operational stability and durability of a catalyst, often quantified by its turnover number (TON), the total number of catalytic cycles it completes before deactivation [32]. These metrics are interdependent, and their optimization is critical for developing efficient, sustainable, and economically viable chemical processes.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking Tables

The following tables synthesize quantitative performance data for various inorganic catalysts across different applications, providing a basis for direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for Metal Oxide CO₂ Capture Catalysts

| Catalyst Material | Modification/Support | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Oxide (MgO) | Fibrous Silica [33] | CO₂ Absorption Capacity | 9.77 mmol/g | CO₂ Capture |

| Magnesium Oxide (MgO) | Activated Carbon Nanofibers [33] | CO₂ Absorption Capacity | 2.72 mmol/g | CO₂ Capture |

| Calcium Oxide (CaO) | Nanoparticles from CaCO₃ [33] | CO₂ Conversion Increase | 20% vs. bulk CaO | CO₂ Capture |

| Calcium Oxide (CaO) | Dispersed on γ-Al₂O₃ [33] | Capacity Retention after 20 cycles | 90% (vs. 50% for bulk CaO) | CO₂ Capture |

| Zinc-Copper (Zn-Cu) | Bimetallic Electrocatalyst [33] | Selectivity (Faradaic Efficiency for CO) | 97% | CO₂ to CO Conversion |

Table 2: Industrial Catalyst Market Performance and Selectivity Segmentation

| Catalyst Type / Segment | Key Performance Attribute | Benchmark / Market Data | Context & Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxalate Hydrogenation Catalyst (Selectivity >95%) [34] | Market Share (2025) | 65% | Dominant in cost-sensitive polyester and ethylene glycol production [34] |

| Oxalate Hydrogenation Catalyst (Selectivity >98%) [34] | Formulation | Premium Formulations | Used for superior conversion efficiency and operational stability [34] |

| Polyester Application Segment [34] | Market Share (2025) | 58% | Leading application sector for oxalate hydrogenation catalysts [34] |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts [35] | Market Share (2024) | >60% | Dominant catalyst type in the industrial market [35] |

Table 3: Advanced and Single-Atom Catalyst (SAC) Performance

| Catalyst System | Key Feature | Performance Highlight | Application Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| CuO-ZnO-ZrO₂ [33] | Graphene Oxide (GO) Support | Excellent efficiency in CO₂ to methanol conversion | CO₂ Utilization |

| Iron-based SACs [36] | Single-Atom Dispersion | Significantly reduced energy requirements for water splitting | Hydrogen Production |

| Platinum-based SACs [36] | Single-Atom Dispersion | Excellent catalytic activity for Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) | Fuel Cells |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure consistency and reproducibility in catalyst evaluation, standardized experimental protocols are essential. These methodologies span from traditional laboratory syntheses to modern computational screenings.

Synthesis and Characterization Protocols

Sol-Gel Synthesis for Nanostructured Catalysts: This wet-chemical method is used for synthesizing metal oxides and other nanostructured catalysts.

- Procedure: A molecular precursor (e.g., a metal alkoxide) is dissolved in a solvent and hydrolyzed to form a colloidal suspension (sol). Further processing leads to the formation of a gel, which is then dried and calcined at high temperatures to yield the final solid catalyst with controlled porosity and surface area [33].

- Application: This method is particularly noted for producing high-surface-area metal oxides like MgO and CaO used in CO₂ capture [33].

Solvothermal Synthesis for Crystalline Materials: This method is used to produce high-quality crystalline catalyst structures, such as Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs).

- Procedure: A precursor and a solvent are placed in a sealed vessel (e.g., an autoclave) and heated to a temperature significantly above the solvent's boiling point. The high temperature and pressure facilitate the crystallization of the product [33].

- Application: Ideal for synthesizing defined structures like HKUST-1 MOF, which has shown CO₂ capture capacities of up to 7.52 mmol/g [33].

Performance Evaluation Protocols

Activity Measurement via Turnover Frequency (TOF):

- Procedure: The reaction rate is measured under standardized conditions (temperature, pressure, reactant concentrations). The TOF is calculated as the number of moles of product formed per mole of active catalytic site per unit time (e.g., seconds or hours). For solid catalysts, determining the exact number of active sites often requires chemisorption techniques [32].

Selectivity Measurement in Competitive Reactions:

- Procedure: A reactant mixture is passed over the catalyst in a controlled reactor (e.g., a fixed-bed flow reactor). The product stream is analyzed using techniques like Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Selectivity for a specific product is calculated as (Moles of desired product formed / Total moles of all products formed) × 100% [32].

Lifetime and Stability Testing:

- Procedure: The catalyst is subjected to long-term operation under reaction conditions, often over hundreds of hours. The Turnover Number (TON) is the cumulative measure of total product molecules formed per catalytic site before deactivation. Accelerated aging tests may also be conducted at higher temperatures to predict long-term stability [32].

AI-Enhanced Catalyst Screening Protocol

The development of Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) now heavily relies on a multi-stage computational protocol accelerated by Artificial Intelligence (AI) [36].

- Workflow Description: The process begins with Density Functional Theory (DFT) and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to generate foundational data on catalytic mechanisms and stability. This data is used to build extensive databases. Machine Learning (ML) regression models then analyze this data to identify key features that influence catalytic performance. Subsequently, Neural Networks (NNs) screen known structural models to predict candidates with high catalytic activity. Finally, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can design novel catalyst structures tailored to specific requirements [36].

AI-Driven Workflow for Single-Atom Catalyst Design [36]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials and computational tools used in modern inorganic catalyst research, as cited in the literature.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Research

| Material / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides (MgO, CaO, ZnO) | Act as solid adsorbents and catalysts, prized for thermal stability and selectivity under harsh conditions [33]. | CO₂ capture and conversion processes (e.g., glycerol to glycerol carbonate) [33]. |

| Zeolites | Microporous, aluminosilicate minerals used as solid acid catalysts and molecular sieves [1] [2]. | Petroleum refining, fluid catalytic cracking (FCC), and chemical synthesis [1] [2]. |

| Noble Metals (Pt, Pd) | Provide highly active sites for reactions, often used in dispersed form on supports [36] [35]. | Fuel cell electrodes, automotive catalytic converters, and hydrogenation reactions [36] [35]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Crystalline porous materials with ultra-high surface area and tunable functionality [33]. | High-capacity CO₂ adsorption and selective catalytic reduction [33]. |