In Situ TEM Heating Stages: Real-Time Nanomaterial Phase Evolution for Advanced Materials Design

This article explores the transformative role of in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) heating stages in characterizing the dynamic phase evolution of nanomaterials.

In Situ TEM Heating Stages: Real-Time Nanomaterial Phase Evolution for Advanced Materials Design

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) heating stages in characterizing the dynamic phase evolution of nanomaterials. By enabling real-time, atomic-scale observation of materials under controlled thermal stimuli, this technique provides unprecedented insights into nucleation, growth, and transformation mechanisms. We cover foundational principles, methodological advances including MEMS-based systems, and applications across catalytic, energy, and biomedical nanomaterials. The review also addresses key challenges such as electron beam effects and data interpretation, while comparing in situ TEM with complementary characterization techniques. This synthesis aims to empower researchers in designing nanomaterials with tailored properties for specific applications.

Understanding Phase Evolution: The Fundamental Principles of In Situ TEM Heating

Application Notes

This document provides key insights and methodologies for studying nanomaterial phase transformations under thermal stimuli, with a specific focus on applications within in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) heating experiments. Understanding these transformations is crucial for advancing materials used in energy storage, catalysis, and drug delivery systems [1] [2].

Fundamental Concepts and Impact

Phase transformations in nanomaterials involve changes in crystal structure, often triggered by thermal energy. These changes directly dictate the material's electronic, catalytic, and mechanical properties [3]. Nano-enhanced Phase Change Materials (NePCMs) demonstrate how nanoparticle inclusions can significantly alter a material's thermal properties. Dispersing nanoparticles within a PCM matrix is a reliable and economically viable technique that can lead to an 80-150% improvement in thermal conductivity for organic PCMs with only 1-2% nanomaterial inclusion [1].

Key Insights from In Situ TEM Studies

Real-time observation using in situ heating TEM reveals unique nanoscale behaviors not apparent in bulk studies:

- High-Temperature Phase Stability: Isolated TiO₂ nanotubes can maintain a unique three-phase (anatase, rutile, brookite) structure at temperatures as high as 950°C, a phenomenon not observed in film or bulk geometries [3].

- Crystallization Initiation: Amorphous TiO₂ nanotubes begin crystallizing into anatase and rutile phases at approximately 300°C, with the brookite phase emerging at around 550°C [3].

- Dynamic Restructuring: Block copolymer nanomaterials in solution can undergo significant restructuring upon heating, transitioning from complex core-shell particles to more uniform spherical micelles, as revealed by correlative liquid-phase TEM and X-ray scattering [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Situ TEM Heating of TiO₂ Nanotubes

This protocol outlines the procedure for dynamically observing phase transformations in a single isolated TiO₂ nanotube [3].

Objective: To elucidate the temperature-dependent crystallization and phase transformation of anodic TiO₂ nanotubes in real-time.

Materials and Equipment:

- Nanomaterial: Amorphous TiO₂ nanotubes, fabricated via anodic oxidation in aqueous or organic electrolytes [3].

- Central Equipment: Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) equipped with an in situ heating holder and a Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) heating device.

- Supplementary Characterization: Ex situ X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Raman Spectroscopy, Scanning TEM (STEM), Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) [3].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer an isolated, single TiO₂ nanotube onto the MEMS heating chip of the in situ TEM holder.

- Microscope Setup: Insert the holder into the TEM column and achieve high vacuum. Use an accelerating voltage of 300 kV for all data acquisition to ensure consistency and minimize voltage-dependent beam effects [3].

- Real-Time Data Acquisition:

- Begin heating the sample at a controlled ramp rate.

- Hold the sample at each target temperature (e.g., 300°C, 550°C, 950°C) and collect data, rather than cooling between steps, to avoid microstructural changes from cooling processes [3].

- At each temperature plateau, acquire:

- High-Resolution TEM (HRTEM) images to observe crystal lattice formation.

- Selected-Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) patterns to identify emerging crystal phases.

- EELS spectra to analyze chemical and electronic structure changes.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze SAED patterns and HRTEM images to identify the emergence of anatase, rutile, and brookite crystal phases.

- Correlate phase identification with the specific temperatures at which they appear.

- Validate in situ TEM findings with ex situ XRD and Raman spectroscopy performed on nanotube films annealed under similar conditions.

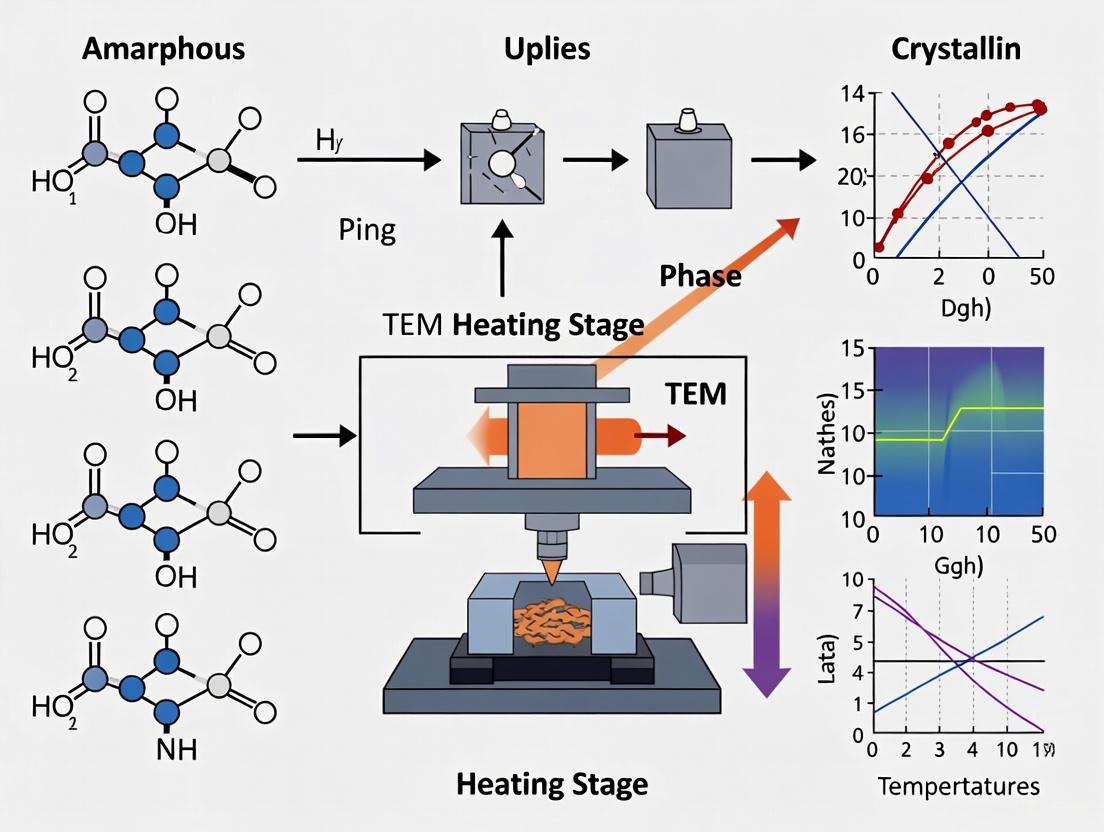

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the in situ TEM heating experiment.

Data Presentation

Quantitative Data on Phase Transformation Temperatures

The table below summarizes the phase transformation data observed in isolated TiO₂ nanotubes during in situ heating TEM [3].

Table 1: Experimentally determined phase transformation temperatures for isolated TiO₂ nanotubes.

| Material | Initial Phase | Crystallization Onset | Anatase & Rutile Formation | Brookite Formation | Final Stable Phase (at 950°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated TiO₂ Nanotube | Amorphous | 300 °C | 300 °C | 550 °C | Coexistence of Anatase, Rutile, and Brookite |

Thermophysical Property Enhancement in NePCMs

The inclusion of nanomaterials within a Phase Change Material (PCM) matrix significantly enhances its properties, as summarized below [1].

Table 2: Enhancement of thermophysical properties in Nano-enhanced Phase Change Materials (NePCMs).

| Base Material Type | Nanomaterial Inclusion | Thermal Conductivity Enhancement | Change in Heat Storage Enthalpy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic PCM | 1-2% of 0D, 1D, 2D, 3D carbon nanomaterials | 80% to 150% improvement | Not Specified |

| Form/Shape Stable PCM | 5-20% weight fraction | 700% to 900% improvement | Reduction (due to nanomaterial weight fraction) |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and their functions for experiments in nanomaterial phase transformations.

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for thermal phase transformation studies.

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| In Situ TEM Heating Holder | A specimen holder with an integrated heating element to thermally stimulate samples inside the TEM. | Real-time observation of phase transformations in nanomaterials like TiO₂ nanotubes [3]. |

| MEMS Heating Chip | A microchip that holds the nanomaterial sample and allows for precise, rapid heating. | Used as a substrate for heating isolated nanotubes and nanowires [3]. |

| Block Copolymer Nanomaterials | "Smart" polymers that self-assemble and restructure in response to temperature changes. | Studying thermally triggered nanoscale restructuring for drug delivery applications [4]. |

| Anodic TiO₂ Nanotubes | Self-organized, vertically aligned nanotube arrays formed by anodization of titanium. | Model system for investigating crystallization and phase stability in low-dimensional semiconductors [3]. |

| Nano-enhanced PCM (NePCM) | A composite material where nanoparticles are dispersed in a phase change matrix to improve thermal properties. | Enhancing thermal energy storage and release rates in solar thermal systems [1]. |

The Critical Role of Atomic-Scale Observation in Unraveling Nucleation and Growth Mechanisms

The controllable synthesis of nanomaterials, essential for applications in catalysis, energy, and biomedicine, is often hindered by an incomplete understanding of their formation mechanisms. Traditional ex situ characterization techniques fall short as they cannot capture the dynamic structural evolution occurring during synthesis [5]. In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) overcomes this limitation by enabling real-time observation and analysis of dynamic processes, such as nucleation and growth, at the atomic scale [5]. This capability is fundamental for directing the design and fabrication of nanomaterials with precisely tailored properties. This Application Note details the protocols and insights derived from in situ TEM heating studies, providing a framework for investigating phase evolution in nanomaterials.

Key Investigated Nanomaterial Systems

In situ TEM heating studies have been pivotal in elucidating the nucleation and growth mechanisms across various nanomaterial systems. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Atomic-Scale Insights from In Situ TEM Heating Studies on Selected Nanomaterials

| Nanomaterial System | Experimental Conditions | Key Atomic-Scale Observation | Quantitative Data / Thresholds | Implication for Nanomaterial Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC Ta Nanocrystals [6] | In situ TEM straining at RT | Size-dependent transition from reluctant (slow) to facile (fast) twin growth | Transition diameter: 15 nmYield stress (10nm): ~6.8 GPaYield stress (23nm): ~4.6 GPa | Exploiting twinning-induced plasticity can break the strength-ductility limit in BCC metallic nanostructures. |

| Isolated TiO2 Nanotubes [3] | In situ heating in vacuum | Crystallization and unique high-temperature phase stability | Crystallization onset: 300 °CBrookite emergence: 550 °CStable 3-phase coexistence up to: 950 °C | Isolated geometry can prevent complete transition to rutile, enabling stabilization of mixed phases for specialized applications. |

| Pb Nanodroplets on PbTiO3 [7] | Electron-beam induced nucleation at RT | Two-step nucleation pathway: precipitation → coalescence | Electron dose: ~11,000 e/ŲsCoalescence time for 10nm crystals: < 3 s | Provides atomic-scale evidence of non-classical growth routes like particle attachment and coalescence. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: In Situ TEM Straining of Metallic Nanocrystals

This protocol is adapted from studies on deformation twinning in Body-Centered Cubic (BCC) Ta nanocrystals [6].

1. Objective: To investigate the atomic-scale mechanisms of deformation twinning and plasticity in BCC metallic nanocrystals under tensile stress.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Nanocrystal Synthesis: Tantalum (Ta) source material, facilities for physical vapor deposition or electrochemical synthesis.

- TEM Support: Specialized MEMS-based in situ TEM straining holder and chips.

3. Equipment:

- Microscope: Aberration-corrected (scanning) transmission electron microscope ((S)TEM).

- Detection: High-resolution TEM camera (e.g., CMOS-based), electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) system.

- Holder: In situ TEM straining holder.

4. Procedure:

1. Sample Preparation: Fabricate single-crystalline Ta nanobridges or nanowires directly onto the MEMS straining chips using a focused ion beam (FIB) or vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) growth method [6].

2. Holder Setup: Load the prepared MEMS chip into the in situ TEM straining holder according to the manufacturer's instructions.

3. Microscope Alignment: Insert the holder into the (S)TEM. Align the microscope and locate a suitable, electron-transparent region of a nanocrystal along the <110> zone axis.

4. In Situ Experiment:

* Begin applying a controlled tensile strain along the [001] crystal direction at a constant strain rate.

* Simultaneously, record the deformation process using high-speed HRTEM imaging. Ensure the electron dose rate is sufficient for clear atomic resolution without causing significant beam damage.

* Continue straining until the nanocrystal fractures or undergoes substantial plastic deformation.

5. Data Acquisition: Capture real-time HRTEM image series or videos. Record corresponding selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns at different strain levels to monitor crystal structure evolution.

5. Data Analysis: * Analyze the HRTEM image series to identify the critical stress and atomic-scale site for twin nucleation. * Track the migration of twinning partials and coherent twin boundaries (CTBs) to measure twin growth rates. * Correlate the applied strain (from the holder data) with the observed deformation mechanisms (dislocation slip vs. twinning).

Protocol B: In Situ Heating of Oxide Nanotubes for Phase Evolution

This protocol is adapted from the study of phase transformations in isolated TiO2 nanotubes [3].

1. Objective: To dynamically elucidate the crystallization and phase transformation pathways in an individual amorphous oxide nanotube under controlled heating.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Nanotube Synthesis: Titanium foil, electrolyte (e.g., aqueous or organic-based with fluoride ions), platinum counter electrode for anodic oxidation.

- TEM Support: Silicon-based in situ TEM heating holder and MEMS heating chips with electron-transparent silicon nitride windows.

3. Equipment:

- Microscope: (S)TEM equipped with EELS.

- Detection: STEM detector, EELS spectrometer, HRTEM camera.

- Holder: In situ TEM heating holder.

4. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: * Synthesize TiO2 nanotube arrays via anodic oxidation of Ti foil [3]. * Carefully scrape the nanotube array film from the substrate and disperse in ethanol. * Drop-cast the suspension onto a MEMS heating chip, allowing isolated nanotubes to adhere. 2. Holder Setup: Load the chip into the heating holder, ensuring electrical contacts are secure. 3. Microscope Alignment: Insert the holder into the (S)TEM. Locate an isolated, well-defined nanotube in STEM or TEM mode. 4. In Situ Experiment: * Set a controlled temperature ramp (e.g., 10-50 °C/min). Acquire data at key temperature points (e.g., 25°C, 300°C, 550°C, 950°C). * At each temperature plateau, acquire: * STEM-BF images to monitor morphological changes. * SAED patterns to identify the emergence of crystalline phases. * HRTEM images to resolve crystal structures and interfaces. * EELS spectra (if available) to analyze chemical and electronic structure changes, particularly the Ti L-edge and O K-edge. 5. Data Acquisition: Hold the temperature constant during data acquisition at each plateau to avoid transient effects.

5. Data Analysis: * Index the SAED patterns to identify crystalline phases (anatase, rutile, brookite) present at each temperature. * Use HRTEM images to measure crystal grain size and spatial distribution of different phases within a single nanotube. * Analyze EELS spectra for fine-structure changes that indicate phase transformation and the formation of oxygen vacancies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for In Situ TEM Nanomaterial Studies

| Item Name | Function / Application | Critical Notes for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS Heating Chips [5] [3] | Provide a controlled high-temperature environment for samples within the TEM. Enable real-time observation of phase transformations. | Ensure chips have low thermal drift and electron-transparent windows (e.g., SiNx). Compatible with your TEM holder. |

| In Situ TEM Straining Holder [6] | Applies precise tensile or compressive stress to nanoscale samples. Crucial for studying deformation mechanics. | Calibration of the force/displacement is critical for quantitative stress-strain data. |

| Graphene Liquid Cells [5] | Encapsulate liquid reagents between graphene sheets. Allow for atomic-scale observation of nucleation and growth in a liquid environment. | Minimizes electron beam scattering compared to traditional silicon-based liquid cells. |

| Gas-Phase Cells / Environmental TEM [5] | Enable the introduction of gaseous environments around the sample. Essential for studying catalysts or materials under reactive atmospheres. | Allows researchers to correlate nanoscale structural changes with gas exposure. |

| Monochromated EELS System [8] | Provides high-energy resolution for analyzing the chemical bonding, electronic structure, and local chemistry of materials at the atomic scale. | Key for detecting subtle changes in electronic structure during phase evolution or at defects. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Generalized in situ TEM experimental workflow for studying nucleation and growth.

Diagram 2: Phase evolution pathway for an isolated TiO₂ nanotube under heating.

In situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) has emerged as a transformative tool in nanomaterials research, enabling direct observation of dynamic processes such as Ostwald ripening, sintering, and solid-state phase transitions in real-time. By applying external stimuli like heating to specimens within the microscope, researchers can quantify the structural and compositional evolution of nanomaterials with high spatial and temporal resolution. This application note details the key phenomena, quantitative findings, and experimental protocols central to a thesis on in-situ TEM heating stage studies, providing a structured framework for researchers and scientists engaged in the development and characterization of advanced materials.

Key Phenomena and Quantitative Data

Ostwald Ripening

Ostwald ripening is a thermodynamically-driven process where larger particles grow at the expense of smaller ones due to differences in surface energy and solubility. The driving force is the higher chemical potential of atoms on the surface of smaller particles, described by the Gibbs-Thomson relation [9] [10]. The Lifshitz-Slyozov-Wagner (LSW) theory quantitatively describes the kinetics of this process for diffusion-controlled systems, where the cube of the average particle radius increases linearly with time [9] [10].

Table 1: Quantitative Descriptors of Ostwald Ripening in Metallic Nanoparticles

| Material System | Experimental Conditions | Quantified Ripening Rate/Behavior | Key Parameters Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiAu Nanoparticles [11] | During catalytic CO₂ hydrogenation in situ TEM | Smaller particles migrated and coalesced faster; Growth of larger particles at expense of smaller ones | Particle diameter/area, circularity, instantaneous migration velocity |

| General Theory (LSW) [9] [10] | Solution or solid-state | ( \langle R \rangle^3 - \langle R \rangle0^3 = \frac{8\gamma c{\infty}v^2 D}{9R_gT}t ) | Average radius ⟨R⟩, time ( t ), interfacial energy ( \gamma ), solubility ( c_{\infty} ), molar volume ( v ), diffusion coefficient ( D ) |

Sintering and Coalescence

Sintering involves the coalescence of adjacent nanoparticles into a single, larger particle upon contact, driven by the reduction of total surface energy. In-situ TEM studies have quantified the migration and coalescence pathways of nanoparticles under reaction conditions [11].

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Nanoparticle Sintering and Migration

| Material System | Experimental Conditions | Migration & Coalescence Behavior | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiAu Nanoparticles [11] | In situ TEM during CO₂ hydrogenation | Particles migrated only when catalytic reactions induced continuous reshaping; migration led to collision and sintering | Directed migration along surface regions with most significant reshaping; sintering via coalescence and ripening |

| PdCu Nanoparticles [11] | In situ TEM during hydrogen oxidation | Oscillatory structural changes evolved into an asymmetric head-tail structure, driving directed migration | Asymmetric PdCu head and Cu₂O tail formation acted as a driving force for particle movement |

Solid-State Phase Transitions

Solid-state phase transitions are transformations from one crystal structure to another without passing through a liquid state. In-situ TEM heating reveals mechanisms like transition through a metastable liquid phase or spinodal decomposition [12] [13].

Table 3: Characteristics of Solid-State Phase Transitions Observed via In-Situ TEM

| Material System | Experimental Conditions | Phase Transition Characteristics | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Au-Cu-Ag-Si BMG [12] | Fast Differential Scanning Calorimetry (FDSC) & In-situ TEM heating | Metastable crystalline state → Metastable liquid → More stable crystalline state | Transformation occurred via a metastable liquid at a temperature far below the equilibrium eutectic temperature |

| Au-Pd Nanoparticles [13] | In situ TEM heating up to 1000 °C | Initial alloy formation (400-800°C), followed by phase separation into Au and Pd phases above 850°C | Formation of a stable, phase-separated Janus Au-Pd nanostructure at 1000 °C |

| Al-Mg-Si-Cu Alloy [14] | In situ heating TEM | Precipitation, phase transformation, and dissolution of nanoscale precipitates | Direct tracking of specific precipitates undergoing phase transformations during heating |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: General In-Situ TEM Heating for Phase Evolution Analysis

This protocol outlines the procedure for observing temperature-induced phenomena like Ostwald ripening, sintering, and phase transitions in nanoparticles [11] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions & Key Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for In-Situ TEM Heating Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metallic Precursor Salts [11] | To synthesize target nanoparticles via wet-chemistry | E.g., Ni(acac)₂, HAuCl₄•4H₂O for NiAu systems; high purity (>99.9%) |

| Solvents & Surfactants [11] | To facilitate nanoparticle synthesis and stabilize dispersion | E.g., Oleylamine (OAm), ethanol; act as reducing agents and colloidal stabilizers |

| In-Situ TEM Heating Holder [5] | Specialist TEM holder to heat specimen while observing | Micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS) based heating chips |

| In-Situ Gas Cell (Optional) [11] [5] | To introduce reactive gas environments during heating | Allows for observations under catalytic reaction conditions (e.g., CO₂, H₂) |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Nanomaterial Synthesis: Synthesize nanoparticles using established wet-chemical methods. For NiAu, dissolve Ni(acac)₂ in oleylamine, then add an ethanolic solution of HAuCl₄•4H₂O under specific temperature and stirring conditions [11].

- TEM Specimen Preparation: Deposit a dilute suspension of the synthesized nanoparticles onto a specialized MEMS-based heating chip. Allow the solvent to evaporate, leaving a dispersed layer of nanoparticles on the chip [5].

- In-Situ Loading: Carefully insert the prepared heating chip into the in-situ TEM holder and load the assembly into the TEM column, ensuring proper electrical contact for heating [5].

- Experimental Parameter Setup:

- Imaging: Establish stable, high-resolution TEM imaging conditions (e.g., HAADF-STEM).

- Heating Profile: Program the desired temperature ramp and hold sequences into the holder controller (e.g., ramp to 400-1000°C at controlled rates).

- Data Acquisition: Start continuous video recording or series image acquisition at a frame rate sufficient to capture dynamic events [11].

- Data Analysis: Utilize deep learning-driven quantification methods (e.g., instance segmentation with Mask R-CNN) to track particle size, shape, position, and trajectory from the recorded video data [11].

Figure 1: In-Situ TEM Heating Experimental Workflow

Protocol 2: Quantifying Nanoparticle Dynamics via Deep Learning

This protocol details the analysis of in-situ TEM video data to extract quantitative descriptors of nanoparticle behavior [11].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Pre-processing: Prepare the recorded in-situ TEM video by correcting for drift and noise, and extract individual frames for analysis.

- Instance Segmentation: Apply a deep learning instance segmentation model (e.g., Mask R-CNN) to identify and separate every nanoparticle in each video frame, even when they are touching or overlapping. This generates a precise mask for each particle [11].

- Multi-Particle Tracking: Link the segmentation masks of individual particles across all frames to construct a complete trajectory for each nanoparticle over time [11].

- Descriptor Extraction: For each particle trajectory, calculate evolving descriptors such as:

- Geometric: Projected area, equivalent diameter, circularity.

- Dynamic: Instantaneous velocity, migration direction, displacement [11].

- Statistical Analysis: Correlate the extracted descriptors with experimental parameters (e.g., temperature, time) to understand kinetics and mechanisms of ripening, sintering, or phase transitions [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Experiment | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based In-Situ Heating Chips [5] | Heats the nanomaterial specimen inside the TEM; low thermal mass enables fast heating rates. | Studying phase transitions in Al-Mg-Si-Cu alloys [14] and coalescence in NiAu NPs [11]. |

| In-Situ Gas Cell Holder [11] [5] | Creates a gaseous microenvironment around the sample for realistic condition studies. | Observing catalyst nanoparticle dynamics during CO₂ hydrogenation [11]. |

| Deep Learning Models (Mask R-CNN) [11] | Performs instance segmentation on TEM videos to identify and track multiple nanoparticles accurately. | Quantifying migration velocity and coalescence events of hundreds of NiAu NPs [11]. |

| Fast Differential Scanning Calorimetry (FDSC) [12] | Measures heat flow associated with phase transitions at very high heating/cooling rates. | Identifying metastable melting and re-crystallization in bulk metallic glasses [12]. |

| Aberration-Corrected (S)TEM [5] | Provides atomic-scale resolution imaging, crucial for resolving structural and compositional changes. | Direct visualization of phase separation in Au-Pd alloys at near-atomic scale [13]. |

Visualization of Phenomena and Mechanisms

Figure 2: Key Phenomena and Their Underlying Mechanisms

The controlled synthesis and thermal treatment of nanomaterials are fundamental to advancing technologies in catalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine. Traditionally, understanding material evolution during heating has relied on ex situ characterization, where samples are analyzed before and after processing, providing only static snapshots of dynamic processes. This approach creates a critical knowledge gap regarding the real-time mechanisms of phase transformations, crystallization, and microstructural changes. In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with specialized heating stages has emerged as a transformative technology, enabling researchers to directly observe and manipulate nanomaterial evolution at the atomic scale under controlled microenvironmental conditions [5]. This Application Note details the protocols and experimental frameworks that allow researchers to overcome traditional limitations, providing a dynamic window into nanomaterial behavior during thermal processing.

Application Notes: Key Insights from Real-Time Observation

In situ heating TEM has revealed complex, non-equilibrium processes that challenge classical theories of nanomaterial behavior, providing insights essential for designing materials with tailored properties.

Unconventional Phase Stability in Isolated Nanostructures

A landmark study investigating the phase evolution of isolated TiO₂ nanotubes revealed exceptional high-temperature stability that diverges significantly from bulk material behavior and previously studied nanotube arrays. Using in situ heating TEM and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), researchers documented that crystallization of amorphous TiO₂ nanotubes initiated at 300°C, forming both anatase and rutile phases simultaneously [3]. Contrary to expectations and prior ex situ studies on array films, a third phase (brookite) emerged at 550°C, and this unique three-phase coexistence (anatase-rutile-brookite) remained stable even at temperatures as high as 950°C [3]. This finding is technologically significant because it demonstrates that isolated nanotubes can maintain metastable phase configurations that enhance functional properties like photocatalytic activity, unlocking new application potential.

Direct Observation of Sintering Dynamics

The sintering process of copper (Cu) nanoparticles has been directly visualized using in situ heating TEM, providing crucial information on neck formation, grain growth, and the role of surface coatings. When heated to 250°C, Cu nanoparticles coated with a thin gelatin biopolymer film began forming contact points (necks) between neighboring particles within 230 seconds, with the process continuing over 630 seconds [15]. Remarkably, the gelatin layer partially decomposed but remained as a 2-5 nm surface layer, preventing oxidation while allowing solid-state diffusion to proceed. Analysis confirmed lattice-fringe continuity at contact regions and pure copper chemistry without oxidation, demonstrating that sintering can proceed effectively with organic capping agents present [15].

Advanced Technique Integration: 4D Nanoscale Tomography

The integration of electron tomography (ET) with in situ heating represents a cutting-edge advancement, enabling three-dimensional characterization of microstructural evolution over time (4D analysis). This approach utilizes rapid heating and cooling capabilities of MEMS-based specimen holders to intermittently freeze the material's state during a tilt-series acquisition for ET [15]. Technical innovations including direct electron detection cameras and faster goniometers have reduced dataset acquisition times to the second level, making it feasible to capture 3D structural changes during thermal processing [15]. This 4D approach provides unprecedented insight into volume changes, pore evolution, and particle interactions that are inaccessible through conventional 2D imaging.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing in situ heating TEM experiments, derived from published studies and commercial platforms.

Protocol: In Situ Heating TEM for Phase Evolution Analysis

Application: Investigating temperature-induced phase transformations in nanomaterials [3].

Sample Preparation

- Nanomaterial Isolation: Disperse individual nanotubes or nanoparticles in ethanol via ultrasonication. Drop-cast suspension onto a MEMS-based heating chip and allow to dry.

- Holder Selection: Use a commercially available in situ heating TEM holder (e.g., Fusion AX from Protochips) [16].

Microscope Setup

- Accelerating Voltage: 300 kV for high-resolution imaging and EELS analysis [3].

- Detector Configuration: Use HAADF-STEM for Z-contrast imaging. Synchronize EELS acquisition for chemical analysis.

- Data Acquisition Rate: Adjust camera acquisition to 1-10 frames per second for dynamic processes.

In Situ Experiment Execution

- Initial Characterization: Acquire baseline images, SAED patterns, and EELS spectra at room temperature.

- Ramped Heating: Increase temperature to target (e.g., 300°C, 550°C, 950°C) at 5-10°C/s using holder software.

- Dwell and Analyze: Hold at each target temperature, acquiring time-series data (images, diffraction, spectra).

- Cooling Phase: Document structural changes during cooling to room temperature.

Data Analysis

- Phase Identification: Correlate HRTEM lattice fringes with SAED patterns for crystal structure assignment.

- Quantitative Morphology: Track dimensional changes (diameter, wall thickness) using image analysis software.

- Spectral Analysis: Process EELS data to identify chemical shifts and phase signatures.

Protocol: 4D In Situ Heating Tomography

Application: Capturing 3D structural evolution of nanomaterials during thermal processing [15].

Specimen Preparation

- Grid Preparation: Deposit nanoparticles onto a MEMS heating chip with minimal debris.

- Fiducial Markers: Use gold nanoparticles as fiducial markers for alignment.

Tomography Acquisition

- Tilt-Series Parameters: Acquire images from -70° to +70° with 1-2° increments.

- Temperature Protocol: Rapidly heat to target temperature, then cool to below reaction temperature during tilt-series acquisition.

- Automated Acquisition: Use software to synchronize heating, cooling, and tilt-series acquisition.

3D Reconstruction and Analysis

- Alignment: Align tilt-series using fiducial or cross-correlation methods.

- Reconstruction: Apply weighted back-projection or SIRT algorithms.

- Segmentation: Use threshold-based methods to identify different material phases.

- 4D Visualization: Create 3D models for each time point to visualize evolution.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Phase Transformation Data for TiO₂ Nanotubes

| Temperature (°C) | Anatase Phase | Rutile Phase | Brookite Phase | Key Structural Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 (Room Temp) | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | Amorphous structure; smooth nanotube walls |

| 300 | Present | Present | Not Present | Initiation of crystallization; both anatase and rutile nucleate simultaneously |

| 550 | Present | Present | Present | Brookite phase emerges; three-phase coexistence established |

| 950 | Present | Present | Present | Unique three-phase structure remains stable; no complete transition to rutile |

Data derived from in situ heating TEM/EELS analysis of isolated TiO₂ nanotubes [3]

Table 2: Technical Specifications for In Situ Heating TEM Methodologies

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Temperature Range | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ Heating TEM | Atomic (~0.1 nm) | Seconds to minutes | Room temp to 1200°C+ | Phase transformations, crystallization, grain growth | Potential electron beam effects; vacuum environment limitations |

| In Situ Heating STEM | Atomic (~0.1 nm) | Seconds to minutes | Room temp to 1000°C | Nanomaterial sintering, elemental mapping via EDS | Z-contrast imaging; higher beam dose possible |

| In Situ Heating ET | ~1-2 nm | 10-60 minutes per volume | Room temp to 400°C+ | 3D particle sintering, pore evolution, volume changes | Rapid heating/cooling required; thermal drift challenges |

| Liquid Phase TEM with Heating | 1-2 nm | Seconds | -160°C to 1000°C | Nanocrystal growth in solution, shape transformation | Radiolysis effects; liquid cell thickness limitations |

Technical specifications compiled from multiple studies [5] [16] [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for In Situ Heating TEM

| Item | Function/Specification | Example Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS Heating Chip | Silicon-based microheater; enables rapid temperature control | General in situ heating experiments | Low thermal drift; compatible with EDS/EELS [15] |

| Graphene Liquid Cell | Encapsulates liquid for solution-phase reactions | Nanocrystal growth in aqueous/organic media | Enables atomic-resolution imaging of liquid-phase processes [5] |

| Gas-Phase Cell | Creates controlled gas environment in TEM column | Catalyst studies under reactive atmospheres | Can replicate realistic catalytic conditions [5] |

| Protochips Poseidon AX | Commercial system for liquid phase TEM with heating | Nanoparticle etching; shape transformation | Allows mixing of reactants and temperature control [16] |

| Protochips Atmosphere AX | Commercial system for gas-phase reactions | Nanowire growth via vapor deposition | Operates at various pressures including 1 bar [16] |

Workflow Visualization

The implementation of in situ heating TEM methodologies represents a fundamental shift in materials characterization, moving from static snapshots to dynamic observation of nanoscale processes. The protocols and applications detailed in this Note demonstrate how researchers can directly observe phase transformations, sintering dynamics, and structural evolution with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution. As these technologies continue to evolve—particularly through integration with machine learning, faster detectors, and multi-modal analysis—the capability to design and optimize nanomaterials based on direct observation of their behavior under processing conditions will become increasingly sophisticated. This paradigm shift enables a more rational design of nanomaterials for specific applications across energy, electronics, and biomedical fields.

Linking Microstructural Evolution to Macroscopic Material Properties

Understanding the intrinsic relationship between a material's microstructural evolution and its resulting macroscopic properties is a cornerstone of advanced materials science and engineering. This relationship is particularly critical for nanomaterials, where subtle changes in phase, composition, and morphology at the atomic scale can dramatically alter functional properties. In situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) heating stages have emerged as a transformative tool, enabling researchers to directly observe and quantify these dynamic microstructural processes in real-time under controlled conditions. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for leveraging in situ TEM heating experiments to establish predictive links between nanoscale evolution and macroscopic material behavior, with a specific focus on phase evolution in functional nanomaterials.

Experimental Protocols for In Situ TEM Heating

Protocol: Phase Transformation Analysis in Single TiO2 Nanotubes

This protocol details the methodology for observing the thermally-driven crystallization and phase transformation of an individual amorphous TiO2 nanotube, as derived from foundational research [3].

- Objective: To dynamically elucidate the crystallization temperature, phase transformation sequence, and high-temperature phase stability in an isolated TiO2 nanotube.

- Materials:

- Nanomaterial: Isolated amorphous TiO2 nanotubes, fabricated via anodic oxidation of titanium foil in aqueous or organic electrolytes [3].

- TEM Support: Electron-transparent MEMS-based in situ heating chip or holder.

- Equipment:

- Transmission Electron Microscope operating at 300 kV.

- In situ heating holder with thermal control unit.

- Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) detector.

- Scanning TEM (STEM) capability.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Disperse fabricated TiO2 nanotubes in ethanol via ultrasonication. Deposit a small volume onto the MEMS heating chip and allow to dry [3].

- Microscope Setup: Insert the heating holder into the TEM. Locate a single, isolated nanotube suitable for observation.

- In Situ Heating Experiment:

- Set the initial temperature to 25°C (room temperature).

- Acquire baseline STEM images, Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) patterns, and EELS spectra.

- Ramp the temperature to a target value (e.g., 300°C) and hold the sample at this temperature for data acquisition [3].

- At each temperature plateau, acquire a full dataset: STEM images, SAED, and EELS.

- Repeat the heating and data acquisition cycle at increasing temperature intervals (e.g., 300°C, 550°C, 950°C).

- Maintain a constant electron beam energy (300 kV) throughout the experiment to ensure consistency and minimize beam-induced artifacts [3].

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze SAED patterns to identify the emergence of crystalline phases (Anatase, Rutile, Brookite) and their crystal planes.

- Use high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images to measure lattice fringes and confirm phase identity.

- Process EELS data to monitor changes in the electronic structure and chemical environment during phase transitions.

Protocol: Microstructure Evolution in Additively Manufactured Alloys

This protocol outlines the approach for characterizing the complex thermal history-driven microstructure in alloys produced by techniques like Selective Laser Melting (SLM), using Ti-6Al-4V as a model system [17].

- Objective: To correlate the thermal gradients and solidification conditions during additive manufacturing (AM) with the resulting grain structure, texture, and solid-state phase transformations.

- Materials: Additively manufactured metallic alloy sample (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V), prepared as an electron-transparent lamella via focused ion beam (FIB) milling.

- Equipment:

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD).

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM).

- Procedure:

- Macro-scale Analysis (SEM/EBSD):

- Map the sample using EBSD to determine grain orientation, size distribution, and texture across different sections (e.g., longitudinal vs. wall section) [17].

- Identify regions of interest, such as columnar grain boundaries and melt pool boundaries.

- Micro/Nano-scale Analysis (TEM):

- Prepare a TEM lamella from a specific region of interest using FIB.

- Perform TEM imaging to analyze fine-scale phases within grains.

- Use SAED to identify metastable phases (e.g., martensite α') and stable phases (α, β) [17].

- In Situ Heating (Optional): Subject the TEM lamella to thermal cycles within the in situ holder to observe phase dissolution, precipitate formation, or grain growth in real-time, replicating post-processing heat treatments.

- Macro-scale Analysis (SEM/EBSD):

Quantitative Data and Property Correlation

The following tables consolidate quantitative data from model systems, demonstrating the direct link between processing conditions, microstructural evolution, and final material properties.

Table 1: Phase Transformation and Stability in a Single TiO2 Nanotube (from in situ heating TEM) [3]

| Temperature (°C) | Observed Phase Transformation | Key Microstructural Observations | Implication for Macroscopic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | Crystallization Initiation | Simultaneous formation of Anatase and Rutile phases. | Activates functional properties (e.g., photocatalysis, electronic conductivity). |

| 550 | Brookite Emergence | Brookite phase appears alongside Anatase and Rutile. | May lead to enhanced or modified photocatalytic activity due to facet-specific effects. |

| 950 | Three-Phase Coexistence | Anatase, Rutile, and Brookite phases remain stable. | Exceptional high-temperature stability prevents full conversion to Rutile, unlocking new high-temp applications. |

Table 2: Microstructure-Property Relationships in Additively Manufactured Ti Alloys [17] [18]

| Material & Process | Grain Structure | Phase Composition | Resulting Macroscopic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti-6Al-4V (SEBM/SLM) | Columnar prior-β grains along build direction [17]. | α/β basket-weave; or acicular α' martensite [17]. | Anisotropic mechanical properties; high yield strength but reduced ductility in certain orientations [17]. |

| TNT5Zr β-Ti Alloy (SLM + HIP + Aging) | Equiaxed β grain matrix [18]. | Nano-sized intragranular α″ precipitates (5-10 nm) [18]. | High ultimate tensile strength (~853 MPa) and superior strength-to-modulus ratio, ideal for load-bearing implants [18]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for In Situ TEM Heating Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anodic TiO2 Nanotubes | Model 1D nanomaterial for studying phase transformations [3]. | Fabrication electrolyte (aqueous vs. organic) determines nanotube dimensions and wall morphology [3]. |

| MEMS In Situ Heating Chips | Provides a thermally conductive, electron-transparent platform for holding samples inside the TEM [5]. | Allows for precise temperature control and real-time observation during heating experiments. |

| Ti-6Al-4V & β-Ti Alloy Powders | Feedstock for additive manufacturing studies [17] [18]. | Powder chemistry and morphology critically influence melt pool dynamics and final microstructure. |

| FIB/SEM System | Preparation of site-specific, electron-transparent TEM lamellae from bulk or AM samples. | Essential for targeting specific microstructural features like grain boundaries or melt pools. |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

In Situ Heating Workflow

AM Microstructure Evolution

Advanced Methodologies and Applications in Thermal Nanomaterial Analysis

Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS)-based heating holders represent a transformative technology for in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM), enabling researchers to observe nanoscale material dynamics in real-time under controlled thermal conditions. These specialized holders facilitate the application of precise thermal stimuli—ranging from cryogenic temperatures of -175°C to extreme highs exceeding 1200°C—directly to samples within the TEM column vacuum environment. The integration of MEMS technology has revolutionized in situ TEM techniques by providing unprecedented control over experimental conditions while maintaining the high spatial resolution necessary for atomic-scale observation. This capability is particularly crucial for phase evolution nanomaterials research, where understanding thermal transformation kinetics, stability thresholds, and structural evolution dynamics is fundamental to materials design and optimization.

The core advantage of MEMS-based heating systems lies in their miniaturized architecture, which incorporates heating elements, temperature sensors, and sometimes electrical contacts into a chip-scale device compatible with standard TEM holders. This sophisticated design enables rapid thermal response and exceptional temperature stability while minimizing thermal drift that traditionally hampered high-resolution imaging during heating experiments. For researchers investigating phase transformations, these systems provide direct visualization capability of phenomena such as nucleation events, grain boundary migration, precipitate evolution, and solid-state reactions as they occur, rather than relying on post-mortem analysis of heat-treated samples.

Design Principles of MEMS Heating Chips

Fundamental Architecture

MEMS heating chips employ sophisticated microfabrication techniques to create miniature heating circuits and sensing elements on silicon-based substrates with electron-transparent windows, typically made of silicon nitride (Si₃N₄). The fundamental design incorporates a resistive heating element patterned around a thin membrane window that allows electron beam transmission while withstanding significant thermal stress. This architecture achieves extremely fast thermal response times and excellent temperature uniformity across the sample area due to the minimal thermal mass of the microfabricated components. The heating elements are typically fabricated from materials with favorable high-temperature resistivity characteristics, such as platinum or doped silicon, which maintain structural integrity and predictable electrical properties throughout the operational temperature range.

The membrane material selection represents a critical design consideration, as it must satisfy competing requirements for electron transparency, mechanical strength, and thermal stability. Silicon nitride membranes typically range from 10-50 nm in thickness, providing sufficient strength to withstand atmospheric pressure differentials while allowing high-resolution imaging. Advanced MEMS designs incorporate multiple electrical contacts—up to nine in state-of-the-art systems—enabling simultaneous heating and electrical biasing experiments for investigating more complex multistimuli material responses [19]. The entire MEMS chip is engineered for compatibility with standard TEM holder form factors, allowing integration without instrument modification.

Temperature Sensing and Control

Accurate temperature measurement and control represents one of the most challenging aspects of MEMS heater design, addressed through integrated four-point resistance sensing methodology. This approach eliminates lead resistance artifacts that would otherwise compromise temperature measurement accuracy, particularly at extreme temperatures. The sensing element is strategically positioned in close proximity to the heating circuit to provide real-time temperature feedback with minimal lag, enabling sophisticated closed-loop control systems that can maintain temperature stability within ±0.1°C for extended durations exceeding 100 hours [19].

The temperature calibration process correlates the measured electrical resistance with temperature through previously established resistance-temperature relationships for the sensing material, often requiring sophisticated modeling to account for thermal gradients across the MEMS structure. Advanced systems incorporate shielded electrical cables and filtering electronics to minimize electromagnetic interference that could compromise sensitive current measurements during operation. This precise thermal control enables researchers to not only set specific isothermal conditions but also to program complex thermal profiles including ramps, spikes, and cycles that mimic real-world thermal processing conditions experienced by materials in service.

Mechanical Stability and Imaging Compatibility

MEMS heating holders incorporate sophisticated mechanical designs to maintain sample stability at high magnifications despite thermal expansion effects. Double-tilt versions feature high-precision goniometer mechanisms with beta-tilt accuracy better than 0.01 degrees and negligible backlash when reversing tilt direction [19]. This exceptional mechanical stability is essential for collecting meaningful data during dynamic thermal processes, as it minimizes image drift that would otherwise complicate analysis of time-resolved microstructural evolution.

The strategic material selection and compact design of MEMS heating chips ensures compatibility with key TEM analytical techniques throughout the operational temperature range. The holders maintain analytical capability for energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) without interference, enabling correlative structural and chemical analysis during thermal treatments [19]. The localized heating approach minimizes thermal load on the surrounding holder components, protecting sensitive electronics and mechanical assemblies from degradation while enabling the extreme temperature capabilities that make these systems indispensable for modern materials research.

Temperature Capabilities and Performance Specifications

Table 1: Technical specifications of commercial MEMS heating holders

| Parameter | Single-Tilt Holder | Double-Tilt Holder |

|---|---|---|

| Tilt Range | Up to ±45° (depending on objective pole) | Up to ±20° (alpha and beta) |

| Beta-Tilt Accuracy | Not applicable | <0.01 degree |

| Electrical Contacts | 9 | 9 |

| Maximum Operating Temperature | >1000°C | >1000°C |

| Settled Resolution at 1000°C | Up to TEM resolution | Up to TEM resolution |

| Temperature Stability | >100 hours | >100 hours |

| Temperature Measurement | 4-point resistance sensing | 4-point resistance sensing |

| EDS/EELS Compatibility | Full temperature range | Full temperature range |

MEMS-based heating systems demonstrate exceptional temperature performance characteristics that enable previously impossible experimental observations. Commercial systems routinely achieve temperatures exceeding 1000°C while maintaining atomic-resolution imaging capabilities, with some specialized configurations reaching even higher temperatures [19]. The thermal stability performance is particularly remarkable, with demonstrated capability to maintain setpoint temperatures within tight tolerances for continuous durations exceeding 100 hours, enabling investigation of slow kinetic processes such as Ostwald ripening, grain growth, and long-term phase stability.

The rapid thermal response of MEMS heaters facilitates experiments with complex thermal histories, including quenching studies, thermal cycling, and short-term annealing treatments. This capability has proven invaluable for investigating processes such as precipitate dissolution in aluminum alloys, where in situ heating TEM observations have revealed the transformation kinetics of nanoscale Al-Mg-Si-Cu precipitates with direct correlation to bulk thermal treatments [20]. The combination of high temperature capability, precise control, and exceptional stability establishes MEMS heating holders as essential tools for probing the thermal behavior of nanomaterials across virtually all material classes.

Experimental Protocols for MEMS Heating Studies

Sample Preparation Methods

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful in situ heating experiments, with several established methodologies available depending on sample characteristics. The micro-manipulator transfer approach provides precise, damage-free placement of specific samples onto MEMS windows, utilizing controlled electrostatic attraction between a tungsten probe tip and the sample [21]. This protocol begins with dispersing the sample material (nanowires, 2D flakes, or FIB lamellae) in ethanol via 10-minute sonication, followed by deposition onto an anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) membrane filter to minimize contact area. Selection of an appropriately sized tungsten tip (typically 100 nm radius for nanomaterials) is essential, with optional application of low bias voltage (0.1-1V) to enhance electrostatic attraction when needed [21].

The MEMS Dropcasting Tool (MDT) offers an alternative approach specifically designed to confine droplets to designated areas, preventing particle migration under O-rings and reducing contamination risks [22]. This 3D-printed, cost-effective solution addresses one of the principal challenges of traditional dropcasting by physically limiting droplet spread, thereby increasing successful preparation rates and experimental reproducibility. For focused ion beam (FIB)-prepared samples, specialized protocols involve eliminating side carbon deposition with low-current (few pA) Ga+ ion milling at 30 kV to facilitate manipulation, though subsequent metallic contact reinforcement via FIB or lithography is recommended to minimize sample drift during heating experiments [21].

In Situ Heating Experiment Workflow

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for MEMS-based heating experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS Heating Chips | Sample support & thermal stimulus | Available with various window sizes & contact configurations |

| Anodic Aluminum Oxide (AAO) Membrane | Temporary substrate for sample selection | 20 nm pore diameter minimizes contact area |

| Tungsten Micro-Manipulator Tips | Precision sample handling | Select tip radius matching sample size (100-1000 nm) |

| Ethanol Solvent | Sample dispersion medium | Enables uniform deposition via dropcasting |

| FIB Preparation Materials | Site-specific sample fabrication | Requires low-current finishing to reduce damage |

The experimental workflow for in situ heating studies follows a systematic sequence to ensure data quality and instrument integrity. Initial system calibration establishes the relationship between heater resistance and actual temperature, accounting for chip-specific characteristics and potential thermal gradients. Sample loading proceeds with careful alignment on the MEMS window, ensuring optimal thermal contact and electrical connection if biasing is incorporated. Once inserted into the TEM, preliminary imaging establishes the initial microstructure before thermal treatment, with specific regions of interest documented for subsequent tracking.

During thermal cycling, simultaneous multimodal data acquisition is recommended, combining high-resolution imaging, scanning diffraction for structural analysis, and spectroscopic techniques where applicable. For example, studies of precipitate evolution in Al-Mg-Si-Cu alloys successfully employed scanning precession electron diffraction at multiple thermal stages to identify phase transformations in individual precipitates during heating [20]. This approach enables direct quantitative assessment of precipitation phenomena, providing insights unattainable through conventional ex situ methods. Experimental parameters including heating rates, hold temperatures, and acquisition intervals should be predetermined based on scientific objectives, with real-time adjustment capability to respond to unexpected observations.

Data Collection and Analysis Protocols

Effective data collection during in situ heating experiments requires strategic planning to capture relevant transformation events while managing electron dose to minimize beam effects. Scanning diffraction approaches combined with data postprocessing enable comprehensive analysis of phase distribution and crystal structure evolution at multiple thermal stages [20]. This methodology proved particularly effective for tracking precipitate transformations in aluminum alloys, identifying specific precipitates that underwent phase changes during heating through sequential phase mapping.

For quantitative analysis, automated image acquisition protocols help maintain consistent imaging conditions throughout extended experiments, with specific attention to focus maintenance as thermal expansion occurs. Advanced data analysis approaches include multivariate statistical analysis of spectral data sets and machine learning-assisted feature identification in image sequences to extract subtle transformation kinetics. Crucially, researchers should account for potential specimen thickness effects when extrapolating results from electron-transparent lamellae (typically ≈90 nm thick) to bulk material behavior, as demonstrated by comparative studies showing differences in transformation kinetics between in situ and ex situ heated specimens [20].

Application Examples in Nanomaterials Research

MEMS-based heating holders have enabled groundbreaking research across diverse material systems, particularly in quantifying phase transformation dynamics at the nanoscale. Studies of Al-Mg-Si-Cu alloys have elucidated the precipitation sequence and dissolution behavior of strengthening phases, directly correlating thermal exposure with precipitate evolution through in situ observations [20]. This approach revealed differences in transformation kinetics between electron-transparent lamellae and bulk specimens, highlighting the importance of specimen geometry in thermal studies [20].

In two-dimensional materials research, heating holders have uncovered unique phase transformations in transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), with studies demonstrating temperature-initiated phase conversions beginning around 500°C, with diffusion velocities dependent upon the applied stimulus [19]. These observations provided critical insights into the thermal stability and phase control of 2D materials for electronic applications. Similar approaches have revealed atomic-scale diffusion phenomena in quantum dots, showing coalescence processes at 650°C, and enabled observation of vacancy migration mechanisms for synthesizing sub-10 nm crystalline TMD nanocrystals [19].

The versatility of MEMS heating systems continues to expand their application space, with recent work including controlled self-assembly in phase-change nanowires, interfacial reactions at one-dimensional interfaces of 2D materials, and real-time observation of crystallization processes. This diverse application portfolio demonstrates the transformative impact of MEMS heating technology across the broader landscape of nanomaterials research, establishing it as an indispensable methodology for understanding material behavior under thermal stimulus.

In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) represents a revolutionary advancement in materials characterization, enabling researchers to directly observe dynamic processes at the nanoscale and atomic level under various external stimuli. Unlike conventional TEM, which is limited to static observations in high vacuum, specialized reactor designs now permit real-time investigation of materials during gas-solid interactions and liquid-phase reactions. These developments are particularly transformative for research on phase evolution in nanomaterials, where understanding dynamic structural changes under operational conditions is critical for developing next-generation materials for catalysis, energy storage, and conversion technologies.

The core principle behind these specialized reactor designs involves integrating microelectromechanical systems (MEMS)-based chips that can apply thermal, electrical, or environmental stimuli to samples while simultaneously allowing high-resolution imaging, diffraction, and spectroscopic analysis. For catalytic studies, gas-cell TEM enables direct visualization of catalysts during exposure to reactive atmospheres, providing unprecedented insights into structure-activity relationships. Similarly, liquid-cell TEM has opened new frontiers for investigating electrochemical processes, including battery cycling, electrocatalysis, and nanoparticle self-assembly in liquid media, with near-atomic resolution. These techniques have become indispensable tools for advancing our fundamental understanding of nanomaterial behavior under realistic conditions, effectively bridging the gap between idealized ex situ characterization and complex operational environments.

Gas-Cell TEM for Catalytic Studies

Technical Fundamentals and Working Principles

Gas-cell TEM employs specialized specimen holders and microfabricated cells to create a confined reactive atmosphere around the sample while maintaining the high vacuum required for electron microscopy. The fundamental design incorporates two ultra-thin electron-transparent windows (typically silicon nitride) that trap a thin layer of reactive gas between them, with the nanomaterial of interest positioned within this gaseous environment. This configuration minimizes electron scattering by the gas while allowing the material to interact with the reactive atmosphere, enabling direct observation of dynamic structural changes during catalytic reactions. Advanced systems can achieve local gas pressures up to atmospheric pressure while maintaining TEM resolution at the nanometer scale, though higher pressures necessitate thicker windows that can slightly reduce resolution.

The integration of heating capabilities within gas-cell TEM systems is particularly valuable for studying thermal catalytic processes. MEMS-based heating chips can rapidly elevate sample temperatures to levels relevant for industrial catalysis (often exceeding 1000°C) with precise control and minimal drift, allowing researchers to directly correlate thermal activation with structural transformations in catalyst materials. These systems simultaneously permit the application of multiple stimuli, enabling studies on how temperature, gas composition, and catalyst structure interact to determine catalytic performance. The development of correlated data collection approaches, where images, diffraction patterns, and spectroscopic signals are acquired simultaneously with quantitative measurements of reaction conditions and catalytic activity, has further enhanced the utility of gas-cell TEM for mechanistic studies in heterogeneous catalysis [23] [24].

Experimental Protocol: Catalytic NO Reduction on Rh Nanoparticles

Objective: To investigate the dynamic structural changes of Rh nanoparticle surfaces during catalytic reduction of NO using gas-cell TEM.

Materials and Equipment:

- Environmental TEM or conventional TEM equipped with gas-cell holder

- MEMS-based gas-cell system with heating capability

- Rh nanoparticle catalyst supported on oxide substrate

- High-purity NO and H₂ gases

- Mass spectrometer system for gas analysis (optional but recommended)

- High-speed camera or direct electron detector for image acquisition

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Disperse Rh nanoparticles onto a MEMS chip with silicon nitride windows compatible with the gas-cell system.

- Ensure uniform distribution of nanoparticles and secure the chip in the gas-cell holder according to manufacturer specifications.

System Setup:

- Insert the gas-cell holder into the TEM and establish stable imaging conditions.

- Connect gas delivery lines to the holder, ensuring leak-free connections.

- For systems with integrated gas analysis, connect the outlet to a quadrupole mass spectrometer for real-time monitoring of reaction products.

- Calibrate the heating element using known melting point standards or via EELS thermal calibration.

Reaction Conditions:

- Introduce a mixture of NO and H₂ gases (typical ratio 1:2 to 1:5) at a total pressure of 2-20 mbar.

- Ramp temperature gradually from room temperature to operational range (200-500°C) while monitoring structural changes.

- Maintain constant gas flow throughout the experiment to ensure steady-state reaction conditions.

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire time-resolved high-resolution TEM images at 1-10 frames per second to capture surface dynamics.

- Record selected area electron diffraction patterns at regular intervals to identify phase transformations.

- Simultaneously collect mass spectrometry data to correlate structural changes with catalytic activity.

- Continue observation for sufficient time to capture multiple cycles of dynamic behavior (typically 10-60 minutes).

Data Analysis:

- Track changes in nanoparticle morphology, surface faceting, and atomic-scale features.

- Correlate structural changes with temperature, gas composition, and reaction products.

- Quantify dynamics such as surface reconstruction rates, particle sintering, or redispersion [25].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Gas-Cell TEM Study of NO Reduction on Rh Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Composition | NO:H₂ = 1:2 to 1:5 | Stoichiometric balance for complete reduction to N₂ and H₂O |

| Total Pressure | 2-20 mbar | Optimized for electron transparency while maintaining relevant catalytic conditions |

| Temperature Range | 200-500°C | Covers typical operating conditions for NO reduction catalysts |

| Imaging Rate | 1-10 frames/sec | Balances temporal resolution with electron dose considerations |

| Spatial Resolution | <1 nm | Enables observation of surface steps, facets, and atomic rearrangements |

Application Example: Operando Analysis of Catalytic Systems

A representative application of gas-cell TEM involves the operando analysis of dynamic structural changes on Rh nanoparticle surfaces during catalytic reduction of NO. In such studies, researchers have directly observed the formation and reduction of surface oxides, facet-dependent reactivity, and particle restructuring under cycling reaction conditions. These observations have revealed how transient surface structures dictate catalytic activity and selectivity, providing mechanistic insights that could not be obtained through post-reaction characterization alone. The integration of mass spectrometry with TEM imaging enables direct correlation between structural dynamics and catalytic function, offering a comprehensive view of the structure-activity relationships that govern catalyst performance [25].

The experimental workflow for such catalytic studies typically involves systematically varying reaction conditions while monitoring both catalyst structure and reaction products, as illustrated below:

Liquid-Cell TEM for Electrochemical Processes

Technical Fundamentals and Working Principles

Liquid-cell TEM utilizes specialized cells with electron-transparent windows to encapsulate liquid environments, enabling direct observation of processes in liquids with nanoscale resolution. The fundamental design consists of two silicon nitride membranes (typically 10-50 nm thick) separated by a spacer that defines a liquid cavity with controlled height (usually 100-1000 nm). This configuration minimizes electron scattering in the liquid while allowing the electron beam to penetrate the sample immersed in solution. Recent advances have integrated microfabricated electrodes directly into the liquid cell, enabling precise control of electrochemical potentials during TEM observation and facilitating studies of battery materials, electrocatalysts, and electrochemical deposition processes.

A significant advantage of liquid-cell TEM is its ability to capture nanoparticle dynamics in their native liquid environment, including growth, self-assembly, and transformation processes. For electrochemical applications, specialized cells with integrated working, counter, and reference electrodes allow for potentiostatic and galvanostatic control during imaging, directly correlating structural changes with electrochemical response. However, careful optimization of experimental parameters is essential, as the electron beam can influence the processes being observed through radiolysis effects, generating reactive species in the liquid that may interfere with natural or electrochemically driven processes. Advanced strategies to mitigate beam effects include using lower electron doses, faster imaging detectors, and incorporating scavengers to neutralize radiolytic products [26] [24].

Experimental Protocol: Nanoparticle Self-Assembly in Liquid Cell

Objective: To investigate the self-assembly dynamics of platinum nanoparticles during solvent drying using liquid-cell TEM.

Materials and Equipment:

- Liquid-cell TEM holder and compatible silicon chips

- Silicon nitride window chips (window thickness ~25 nm)

- Platinum nanoparticle dispersion (8.3 nm diameter, stabilized with oil-amine)

- Solvent mixture: orthodichlorobenzene, pentadecane, and oil-amine

- Microinjection system for liquid cell loading

- Optical microscope for chip inspection

- Copper aperture grids with 600 μm holes

Procedure:

- Liquid Cell Assembly:

- Inspect silicon nitride window chips for defects using optical microscopy.

- Pattern indium spacers onto the bottom chip using photolithography.

- Align top and bottom chips and bond at 100°C to create a sealed liquid cell.

Sample Loading:

- Prepare nanoparticle dispersion by mixing platinum nanoparticles with orthodichlorobenzene, pentadecane, and oil-amine.

- Using a microinjection system, load 100 nL of the dispersion into the liquid cell reservoir.

- Remove excess dispersion using filter paper to control liquid thickness.

- Allow the cell to stand in ambient air for 10 minutes to partially evaporate the orthodichlorobenzene.

TEM Imaging:

- Mount the liquid cell in a standard TEM holder and insert into the microscope.

- Begin continuous image acquisition as solvent drying proceeds.

- Use a low electron dose (1-100 e⁻/Ų·s) to minimize beam effects on assembly process.

- Acquire images at 0.5-2 second intervals to capture assembly dynamics.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate radial distribution functions from sequential TEM images.

- Track nanoparticle motion and assembly kinetics using tracking algorithms.

- Correlate solvent drying front movement with assembly behavior [26].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Liquid-Cell TEM Study of Nanoparticle Self-Assembly

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Type | Oil-amine capped Pt | Provides uniform size and controlled surface chemistry |

| Particle Diameter | 8.3 nm | Optimal for tracking individual particles while observing collective behavior |

| Liquid Layer Thickness | 100-500 nm | Balances electron transmission with realistic confinement effects |

| Electron Dose Rate | 1-100 e⁻/Ų·s | Minimizes beam-induced artifacts while maintaining usable signal |

| Imaging Interval | 0.5-2 seconds | Captures relevant timescales for assembly dynamics |

Application Example: Electrochemical Deposition and Battery Materials

Liquid-cell TEM has proven particularly valuable for studying electrochemical processes, including electrode-electrolyte interfaces in battery systems and electrochemical deposition phenomena. For battery materials, researchers have directly observed lithium ion transport, interfacial reactions, and phase transformations during cycling, providing crucial insights into degradation mechanisms and informing strategies for performance enhancement. Similarly, studies of electrochemical deposition have revealed nucleation and growth processes at the nanoscale, showing how applied potential and electrolyte composition influence deposit morphology and growth kinetics. These observations have challenged classical models of electrochemical phase formation and led to improved processing strategies for functional nanomaterials.

The experimental workflow for liquid-cell TEM studies of electrochemical processes typically involves coordinating electrochemical stimulation with high-resolution imaging, as illustrated below:

Comparative Analysis and Technical Considerations

Performance Metrics and Limitations

Both gas-cell and liquid-cell TEM offer unique capabilities for in situ studies, but each approach has distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal application domains. Gas-cell TEM typically provides higher spatial resolution (often sub-nanometer) due to lower scattering from gas compared to liquid, making it preferable for atomic-scale surface studies. Liquid-cell TEM, while generally offering slightly lower resolution due to increased scattering in liquids, enables investigation of solution-phase processes essential for understanding electrochemical systems, biological samples, and synthetic pathways in nanomaterial growth. Both techniques face challenges related to electron beam effects, which can alter the processes being observed, though specific mitigation strategies have been developed for each configuration.

The table below summarizes key technical considerations when selecting between these specialized reactor designs for specific research applications:

Table 3: Comparison of Gas-Cell vs. Liquid-Cell TEM Capabilities

| Parameter | Gas-Cell TEM | Liquid-Cell TEM |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Spatial Resolution | 0.5-2 nm | 1-5 nm |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond-second | Second-minute |

| Maximum Pressure/Concentration | ~1 atm (gas) | ~1 M (solution) |

| Primary Applications | Heterogeneous catalysis, gas-solid reactions, oxidation/reduction | Electrochemistry, battery studies, nanoparticle growth, biological processes |

| Key Advantages | Higher resolution, well-established for catalysis, compatible with various gases | Enables study of solution-phase processes, direct observation of electrochemical interfaces |

| Main Limitations | Limited to gas-solid interfaces, potential beam-induced reactions | Increased electron scattering, more pronounced beam effects, complex cell fabrication |

| Beam Effect Considerations | Radiolysis can create reactive species; manageable with dose control | Significant radiolysis producing radicals and hydrated electrons; requires careful dose management |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of specialized reactor TEM experiments requires careful selection of materials and reagents optimized for specific research objectives. The following table details essential components for both gas-cell and liquid-cell TEM studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Specialized Reactor TEM

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based Chips with Heaters | Provides controlled thermal stimulation while allowing electron transparency | Phase transformation studies, thermal catalysis, annealing processes |

| Silicon Nitride Membrane Windows | Creates sealed environment while maintaining electron transparency | Both gas-cell and liquid-cell containment, typically 10-50 nm thickness |

| Microfabricated Electrodes | Enables electrochemical control during TEM observation | Battery cycling studies, electrocatalysis, electrodeposition processes |

| High-Purity Gases (NO, H₂, O₂, CO) | Creates reactive atmospheres for catalytic studies | Heterogeneous catalysis, oxidation/reduction reactions, environmental TEM |

| Stabilized Nanoparticle Dispersions | Model systems for studying assembly and transformation dynamics | Nanocrystal growth, self-assembly studies, catalytic nanoparticle behavior |

| Specialized Solvents (Orthodichlorobenzene, Pentadecane) | Low vapor pressure solvents for liquid cell experiments | Nanoparticle self-assembly, controlled drying processes |

| Electron Sensitive Detectors | Enables high-speed, low-dose imaging | Capturing dynamic processes while minimizing beam damage |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | Correlates structural changes with reaction products | Operando catalysis studies, quantification of reaction kinetics |