In Situ Liquid Cell TEM for Nanomaterial Synthesis: A Comprehensive Guide to Real-Time Visualization and Control

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in situ liquid cell transmission electron microscopy (LCTEM), a revolutionary technique enabling real-time, atomic-scale observation of nanomaterial synthesis in liquid environments.

In Situ Liquid Cell TEM for Nanomaterial Synthesis: A Comprehensive Guide to Real-Time Visualization and Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in situ liquid cell transmission electron microscopy (LCTEM), a revolutionary technique enabling real-time, atomic-scale observation of nanomaterial synthesis in liquid environments. Tailored for researchers and scientists in nanotechnology and drug development, we explore the foundational principles of LCTEM, detailing its core configurations and working mechanisms. The review systematically covers advanced methodologies and their direct applications in visualizing dynamic processes like nucleation, growth, and oriented attachment. We address critical experimental challenges, including electron beam effects and resolution limitations, offering practical strategies for optimization. Finally, we validate LCTEM's capabilities by comparing it with other characterization techniques and highlighting its unique insights through case studies in catalyst and battery material development. This guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging LCTEM to accelerate the design and synthesis of next-generation nanomaterials.

Foundations of Liquid Cell TEM: Visualizing Nanomaterial Synthesis in Liquid Environments

The controllable preparation of nanomaterials faces significant challenges in controlling size, morphology, crystal structure, and surface properties, which are essential for optimizing performance in applications ranging from catalysis and energy to biomedicine [1]. A fundamental limitation has been the inability to observe nanomaterial growth processes in real time, forcing researchers to rely on ex situ characterization techniques that provide only static snapshots of dynamic processes [1]. These conventional methods capture materials before and after reactions or synthesis, missing critical transitional states and mechanistic details. This analytical gap has hindered the profound understanding of nucleation and growth mechanisms necessary for advancing nanomaterial design [1].

In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) has emerged as a transformative solution that overcomes these limitations by enabling real-time observation and analysis of dynamic structural evolution during nanomaterial growth at the atomic scale [1]. By allowing researchers to peer into nanomaterial formation processes under various conditions including high temperatures, pressures, and different chemical environments, in situ TEM has become an indispensable tool for understanding and controlling material properties at the fundamental level [1]. This capability is particularly crucial for advancing our understanding of phenomena such as Ostwald ripening, phase separation, and defect evolution, which are pivotal in determining the final properties of nanomaterials [1].

Fundamental Limitations of Ex Situ Characterization

Ex situ characterization methods present several critical limitations that impede comprehensive understanding of nanomaterial behavior:

- Temporal Gaps: Ex situ techniques capture only pre- and post-reaction states, missing intermediate phases and transient states that are critical for understanding reaction pathways [1].

- Environmental Disruption: Sample removal from native environments (liquid, gas, or stress conditions) can alter structures, leading to artifacts that misrepresent true material behavior [2].

- Incomplete Mechanistic Understanding: Without direct observation of dynamic processes, researchers must infer mechanisms from static snapshots, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about growth pathways [1].

The comparison below summarizes key differences between ex situ and in situ approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Ex Situ vs. In Situ Characterization Approaches

| Characteristic | Ex Situ Characterization | In Situ Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Static snapshots only | Real-time observation of dynamics |

| Environmental Context | Removed from native environment | Preservation of reaction conditions |

| Mechanistic Insight | Indirect inference | Direct observation of pathways |

| Atomic-Scale Information | Limited to post-process analysis | Real-time atomic-scale evolution |

| Artifact Potential | High due to sample transfer | Minimized through continuous observation |

In Situ TEM Methodologies and Capabilities

Technical Classifications of In Situ TEM

In situ TEM methodologies monitor developmental stages of material systems by establishing and activating external conditions through specialized TEM holders [1]. These can be categorized into five primary types:

- In Situ Heating Chips: Enable thermal stability studies and phase transformation observations [3].

- Electrochemical Liquid Cells: Facilitate nanomaterial synthesis and battery research in liquid environments [1].

- Graphene Liquid Cells: Provide superior imaging capabilities for liquid-phase nanomaterial growth [1].

- Gas-Phase Cells: Allow observation of catalytic reactions and gas-solid interactions [1].

- Environmental TEM (ETEM): Enables high-pressure gas environment studies [1].

The development of Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS) technology has revolutionized these methodologies, particularly for heating experiments. MEMS-based heating holders enable rapid heating and cooling of specimens, with some designs achieving heating to 800°C in 26.31 ms and cooling in 42.58 ms, while maintaining minimal sample drift of approximately 2 nm/s at 650°C [3].

Core Technical Capabilities

The multimodal approach of in situ TEM integrates imaging with spectroscopic techniques, creating a comprehensive characterization platform [1]. Key capabilities include:

- Atomic-Scale Resolution: Aberration-corrected lenses and advanced imaging modalities like high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) enable atomic-level observation [1].

- Multimodal Analysis: Simultaneous imaging with spectroscopic techniques such as energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) provides correlated structural, chemical, and electronic information [1].

- Dynamic Process Visualization: Real-time observation of nucleation events, growth pathways, and structural dynamics including defect evolution [1].

- Quantitative Analysis: Integration with deep learning approaches enables extraction of spatio-temporal information from dynamic processes, such as tracking dislocation motion in crystalline materials [4].

Experimental Setups and Methodologies

Liquid Cell Nanomaterial Synthesis

Liquid cell TEM has emerged as a particularly powerful methodology for studying nanomaterial synthesis in liquid environments, directly relevant to the thesis context of liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis research. This approach enables direct observation of colloidal nanomaterial growth, electrochemical deposition, and biological mineralization processes that occur in solution phases [1].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Situ TEM Liquid Cell Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | Metal chlorides, nitrates, acetates | Source of metal ions for nanoparticle formation |

| Reducing Agents | Sodium borohydride, ascorbic acid, citrate | Convert metal ions to neutral atoms for nucleation |

| Surfactants/Capping Agents | CTAB, PVP, gelatin | Control nanoparticle shape and prevent aggregation |

| Solvents | Water, ethylene glycol, organic solvents | Reaction medium mimicking synthetic conditions |

| Support Membranes | Silicon nitride, graphene | Encapsulate liquid while allowing electron transmission |

The experimental protocol for liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis typically involves:

- Cell Fabrication: Silicon chips with etched windows and silicon nitride membranes are used to create sealed chambers capable of containing liquid while allowing electron transmission [1].

- Solution Preparation: Precursor solutions containing metal salts, reducing agents, and surfactants are prepared at controlled concentrations [1].

- Cell Loading: Nanoliters of solution are injected between two silicon chips sealed to create a thin liquid layer [1].

- In Situ Observation: The sealed cell is loaded into a specialized TEM holder, and synthesis is initiated through thermal activation or electron beam exposure while recording dynamic processes [1].

In Situ Heating Methodologies

Heating experiments represent the most commonly used external stimulus in in situ TEM studies [3]. The methodology for in situ heating experiments involves:

- Specimen Preparation: Thin specimens (preferably below 100 nm thickness) are prepared via electropolishing or focused ion beam techniques [2].

- Holder Configuration: MEMS-based heating holders or conventional furnace holders are used with thermocouples for temperature calibration [3].

- Temperature Ramping: Controlled heating rates (e.g., 23.3°C/min) are applied while maintaining imaging conditions [2].

- Data Acquisition: Continuous recording or time-lapse imaging captures microstructural evolution, sometimes combined with spectroscopic techniques [3].

For complex analyses combining heating with electron tomography, a specialized procedure is employed: (i) using the rapid heating-and-cooling function of a MEMS holder; (ii) heating and cooling the specimen intermittently; and (iii) acquiring a tilt-series dataset when specimen heating is stopped [3]. This approach enables four-dimensional (space and time) characterization of thermal processes.

Data Analysis and Interpretation Frameworks

Quantitative Analysis Approaches

The integration of advanced computational methods has transformed in situ TEM from a qualitative observational tool to a quantitative analytical platform:

- Deep Learning Integration: Convolutional neural networks can be trained to identify and track specific microstructural features such as dislocations, enabling statistical analysis of their behavior [4].

- Digital Twin Methodology: Creating computational replicas of in situ experiments allows for matching simulations and extraction of quantitative parameters from dynamic processes [4].

- Spatio-Temporal Mapping: Advanced algorithms extract movement pathways and dynamics of defects, interfaces, and other microstructural features [4].

For example, in studying dislocation dynamics in Cantor high-entropy alloys, deep learning approaches have enabled the direct observation of "stick-slip motion" of single dislocations and computation of corresponding avalanche statistics, revealing scale-free distributions with power law exponents independent of driving stress [4].

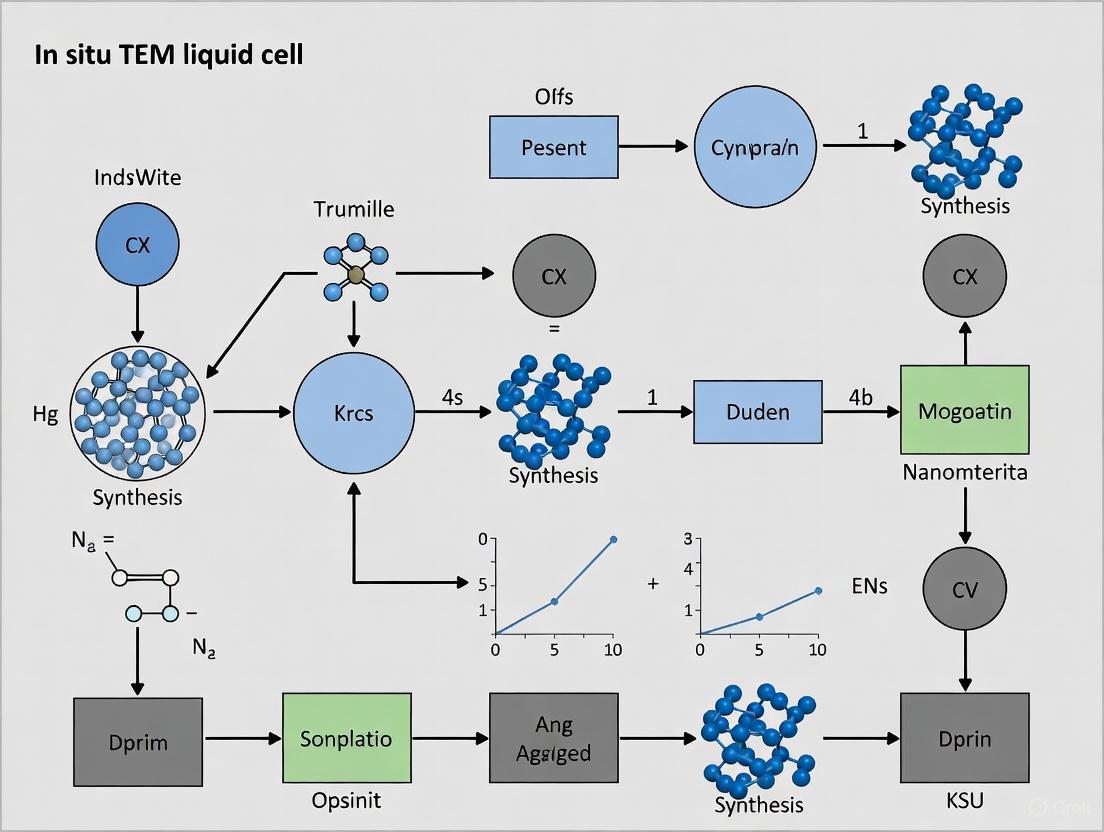

Experimental Workflow and Data Processing

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for in situ TEM experiments, from setup to data analysis:

In Situ TEM Experimental Workflow

Limitations and Validation Considerations

Despite its powerful capabilities, in situ TEM methodology presents several important limitations that researchers must consider:

- Thin Specimen Effects: Studies on nanocrystalline copper demonstrate that grain growth stagnation occurs in thin specimens (<100 nm) due to grain boundary grooving, potentially yielding different results than bulk material behavior [2].

- Electron Beam Effects: The incident electron beam can influence observed processes through radiolysis, heating, or knock-on damage, potentially altering natural progression of phenomena [1].

- Field of View Limitations: The restricted observation area may not capture representative material behavior, potentially missing rare events or heterogeneous processes [2].

- Temporal Resolution Constraints: While dramatically improved, temporal resolution may still miss ultrafast processes occurring at microsecond or faster timescales [3].

Validation studies comparing in situ TEM with bulk experiments are essential. Research on nanocrystalline HT-9 steel showed similar grain growth behavior between in situ TEM and bulk annealing, while nanocrystalline copper demonstrated significant differences, highlighting the material-dependent nature of these limitations [2]. This underscores the importance of correlating in situ TEM observations with ex situ bulk material characterization to ensure representative results [2].

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The future development of in situ TEM holds significant potential across multiple domains:

- Multi-Modal Integration: Combination with synchrotron X-ray techniques and other characterization methods will provide complementary information across different length scales [5].

- Machine Learning Enhancement: Artificial intelligence algorithms will enable automated identification of complex structural transformations and predictive modeling of material behavior [1] [4].

- Operando Methodology Expansion: Evolution from in situ observation to operando characterization, where materials are studied during actual device operation, will provide direct structure-property relationships [3].

- Temporal and Spatial Resolution Advances: Ongoing detector development and miniaturization of TEM components will push resolution limits, enabling capture of fleeting events and transient states [1].

In the specific context of liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis, future developments are expected to address critical research challenges including reaction inhomogeneity in commercial applications, fast charging processes in battery materials, and stabilization of solid-electrolyte interphases [5]. These advancements will contribute significantly to the design and preparation of nanomaterials with precisely controlled properties for targeted applications.

In situ TEM has fundamentally transformed materials characterization by overcoming the critical limitations of ex situ approaches. By enabling real-time observation of dynamic processes at the atomic scale under relevant environmental conditions, it has provided unprecedented insights into nanomaterial synthesis, phase transformations, and structure-property relationships. While methodological considerations such as thin specimen effects and electron beam interactions require careful attention, the integration of advanced computational methods and multi-modal approaches continues to expand the capabilities of this powerful characterization platform. For researchers focused on liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis, in situ TEM offers a unique window into the dynamic processes governing nanomaterial growth and evolution, enabling the rational design of next-generation materials with tailored properties for advanced applications.

In situ liquid cell Transmission Electron Microscopy (LCTEM) represents a paradigm shift in nanomaterials research, enabling direct, real-time observation of dynamic processes in liquid environments at the nanoscale. The fundamental challenge this technology addresses is the profound incompatibility between the high-vacuum environment required for electron beam transmission and the liquid media essential for studying nanomaterial synthesis, biological specimens, and electrochemical reactions. Within the context of a broader thesis on in situ TEM liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis research, the core principle of fluid encapsulation is the critical enabler, permitting researchers to peer into the "black box" of solution-phase reactions and processes. By creating a nanoscale hermetically sealed environment within the TEM column, liquid cells allow for the application of powerful atomic-scale imaging and spectroscopic techniques to systems in their native or operational liquid state, thereby bridging a fundamental gap in materials characterization [1] [6].

The ability to observe processes such as nanoparticle nucleation and growth, electrochemical deposition, and biomaterial transformation in real-time has transformative implications across multiple fields. For catalysis, it reveals active sites and mechanistic pathways; for energy storage, it elucidates interphase formation and degradation mechanisms; and for biomedicine, it enables the study of drug delivery vehicles and biological macromolecules in situ [7] [8]. The development of this capability hinges entirely on a robust and reliable method to safely encapsulate fluids without compromising the vacuum integrity of the microscope or the spatial resolution of the technique. This guide details the core principles, designs, and operational methodologies that make this possible.

Core Encapsulation Principle and Cell Architecture

The universal principle underlying all TEM liquid cells is the use of electron-transparent membranes to create a sealed, microfluidic chamber that can withstand the pressure differential between the internal liquid and the external microscope vacuum. This simple yet powerful concept allows the electron beam to pass through the cell with minimal scattering, thereby enabling high-resolution imaging while safely containing the fluid.

The Hermetic Sealing and Membrane System

At the heart of any liquid cell are the electron-transparent windows. These are typically ultra-thin, low-stress silicon nitride (SiN) membranes, often on the order of 10 to 50 nanometers thick, fabricated on a silicon support chip [9] [10]. Silicon nitride is the material of choice due to its excellent mechanical strength, chemical inertness, and low atomic number, which minimizes electron scattering. The membrane sealing is achieved through two primary architectures:

- Two-Chip Cells: This common design involves a pair of identical Si chips, each featuring a SiN window. The chips are aligned face-to-face, with integrated spacers (e.g., patterned SiO₂, polystyrene microspheres, or deposited metal) precisely defining the height of the liquid channel, typically between 100 nm and 1 µm [9] [10]. The assembly is then clamped within a specialized TEM holder to form a seal.

- Monolithic Cells: To address challenges of membrane bulging and liquid layer non-uniformity in two-chip designs, a pillar-supported monolithic cell was developed. In this design, the upper and lower SiN membranes are fabricated on a single silicon chip, with silicon dioxide pillars providing permanent, robust support. This design eliminates the need for spacer particles and significantly reduces membrane deformation, leading to a more uniform liquid layer and superior imaging performance [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and the pathway of the electron beam through this encapsulated system:

The Specialized TEM Holder and Microfluidics

The sealed liquid cell is mounted into a specialized TEM holder that serves as the interface between the cell and the microscope. This holder is a complex piece of engineering that incorporates microfluidic channels for liquid delivery and removal. Using precision syringe pumps, researchers can control the flow of liquid, allowing for the introduction of reagents, mixing of solutions, and purging of products or bubbles during an experiment [8]. This dynamic control is vital for studying reaction kinetics and for maintaining a stable, representative liquid environment. The holder is designed with multiple safety interlinks and leak-detection systems to immediately seal fluidic paths in the event of a pressure anomaly, providing a primary layer of protection for the multi-million-dollar TEM column [8].

Classification and Comparison of Liquid Cell Technologies

Liquid cell technologies can be categorized based on their window material and primary function. The choice of cell type involves a trade-off between ease of fabrication, liquid thickness control, signal-to-noise ratio, and chemical compatibility.

Table 1: Classification of Primary Liquid Cell Types for In Situ TEM

| Cell Type | Core Structure | Key Features | Optimal Applications | Inherent Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiN Windowed Cell [9] [10] | Two Si chips with silicon nitride (SiN) windows, separated by spacers. | Well-established fabrication; integrated microfluidics for flow and mixing; compatible with electrical biasing and heating. | General purpose synthesis of nanomaterials; electrochemistry (batteries, electrocatalysis); biomineralization. | Potential for membrane bulging; limited spatial resolution if liquid layer is too thick. |

| Monolithic Pillar-Supported Cell [9] | Single Si chip with two SiN membranes supported by internal SiO₂ pillars. | Highly uniform, spacer-free liquid layer; minimized membrane bulging; enables atomic-resolution imaging and quantitative EELS. | High-resolution imaging and spectroscopy of processes in liquids; quantitative analysis. | More complex fabrication process; fixed liquid channel height. |

| Graphene Liquid Cell (GLC) [1] | One or two layers of graphene as the sealing membrane. | Ultimate signal-to-noise ratio due to atomically thin windows; sub-nanometer resolution. | Studying high-resolution nucleation and growth of nanoparticles. | Fragile and challenging to fabricate and load reproducibly; limited viewing area. |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Optimization

Achieving high-quality data from LCTEM experiments requires careful optimization of several interdependent parameters to balance spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and electron beam effects.

Spatial Resolution and Liquid Thickness

The spatial resolution in LCTEM is primarily limited by the scattering of the electron beam as it passes through the multiple layers of the cell. The total thickness of the SiN membranes and the liquid layer determines the amount of inelastic scattering, which introduces chromatic aberration [9]. For a standard cell with 50 nm SiN membranes on the top and bottom and a 500 nm water layer, approximately 75% of the incident electrons will be scattered. However, high-resolution imaging remains possible, albeit with a loss in contrast and signal-to-noise ratio. The monolithic pillar-supported cell design, by ensuring a highly uniform and minimal liquid thickness, has demonstrated imaging resolution down to 0.24 nm in both TEM and STEM modes [9].

Managing Electron-Beam Effects

A critical consideration in LCTEM is the interaction of the high-energy electron beam with the liquid medium. This interaction can radiolyze water, generating reactive species such as hydrated electrons (e⁻ₐq), hydrogen radicals (H•), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [11] [6]. These species can participate in unintended chemical reactions, such as the reduction of metal precursors to form nanoparticles, or the degradation of sensitive (bio)organic molecules. To manage this, strategies include:

- Minimizing the Electron Dose: Using the lowest possible beam current and frame rates consistent with the required image quality.

- Using Radical Scavengers: Adding chemicals like sodium ascorbate to the solution to consume radiolytic species before they can interact with the sample of interest [11].

- Pulsed or Triggered Imaging: Acquiring images intermittently rather than continuously to reduce the total dose on the sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful LCTEM experimentation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials designed for compatibility with the microfabricated cells and the TEM environment.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for LCTEM

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SiN Membrane E-Chips [8] [10] | Sample support and fluid encapsulation. | MEMS-based devices with predefined window sizes; may include integrated heaters or electrodes for multimodal experiments. |

| Precursor Salts (e.g., Ammonium hexachloroplatinate) [10] | Source of metal ions for nanoparticle synthesis studies. | Dissolved in solvents (e.g., water, ethylene glycol) to create a precursor solution for flow-cell experiments. |

| Supporting Electrolytes (e.g., LiClO₄, CuSO₄) [8] [6] | Enable ionic conductivity for electrochemical experiments. | Essential for studying battery plating/stripping and electrocatalytic reactions within the liquid cell. |

| Radical Scavengers (e.g., Sodium Ascorbate) [11] | Mitigate electron beam-induced damage by reacting with radiolytic radicals. | Crucial for studying beam-sensitive materials, including biomolecules and soft materials. |

| Inert Solvents (e.g., Degassed Water, Toluene) [10] | Liquid medium for the reaction of interest. | Must be purified and degassed to minimize bubble formation in the microfluidic circuit under vacuum. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Liquid Cell Assembly and Imaging

The following protocol, adapted from established methodologies in the field, outlines the critical steps for preparing and conducting a basic nanoparticle synthesis experiment using a silicon nitride windowed liquid cell [10].

- Liquid Cell Preparation: Secure a pair of clean SiN E-chips into the designated slots of the Poseidon AX holder or equivalent, ensuring the SiN windows are properly aligned.

- Sample Loading:

- Pipette a small volume (≈ 0.5 - 1 µL) of the nanoparticle precursor solution (e.g., 1 mM hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (HAuCl₄) in water) onto the lower E-chip.

- Carefully engage the cell closure mechanism to bring the upper and lower E-chips together, forming a sealed liquid chamber. The spacer thickness determines the final liquid layer thickness.

- Holder Insertion: Follow the manufacturer's precise instructions to insert the loaded holder into the TEM airlock. Slowly pump down the airlock to evacuate any gas from the external surfaces of the cell before transferring it into the main TEM column.

- Imaging and Reaction Initiation:

- Navigate the TEM to locate the SiN window area. Adjust the electron beam to a low-dose condition (e.g., < 10 e⁻/Ųs) to locate the area of interest while minimizing beam effects.

- Begin real-time data acquisition using a direct electron detection camera. To initiate nanoparticle growth, the energy of the electron beam can be used as the sole trigger (beam-induced synthesis), or a second reagent can be introduced via the microfluidic inlet lines to mix with the precursor (solution-mediated synthesis).

- Data Collection and Analysis: Record the dynamic process as nanoparticles nucleate and grow. Use integrated software suites (e.g., AXON) for real-time drift correction, dose mapping, and metadata indexing [8]. Subsequent analysis of the video data may involve particle tracking and machine learning-based denoising to extract quantitative growth kinetics and mechanisms.

The field of LCTEM continues to advance rapidly. Future developments are focused on achieving even higher spatial and temporal resolution, improving the control over the liquid environment, and minimizing beam damage. Key directions include the integration of machine learning and AI for automated image analysis and real-time experiment feedback, the development of more robust and thinner window materials, and the combination with other in situ techniques such as optical spectroscopy [11] [6]. Furthermore, the push towards standardization and reproducibility in sample preparation and data handling is critical for LCTEM to become a routine analytical tool rather than a specialized technique [8] [12].

In conclusion, the core principle of safely encapsulating fluids in a TEM vacuum rests on the elegant combination of hermetic sealing with electron-transparent membranes, precision microfluidics, and specialized holder technology. This powerful toolkit has opened a unique window into the dynamic world of nanoscale processes in liquids, directly contributing to advancements in nanotechnology, materials science, and drug development. As these encapsulation technologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly unlock deeper insights and foster further innovation across the scientific spectrum.

In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) has revolutionized materials science by enabling real-time observation of dynamic processes at the nanoscale. Liquid cell TEM (LCTEM), a specialized in situ technique, allows researchers to study materials in their native liquid environments, providing unprecedented insights into fundamental processes in fields ranging from electrochemistry to cell biology [13]. This technical guide focuses on the two predominant liquid cell configurations: microchip-based cells and graphene liquid cells. These configurations enable the safe encapsulation of liquids within the high-vacuum environment of a TEM, facilitating the direct visualization of nanomaterial synthesis, electrochemical reactions, and biological phenomena [13] [1]. The development of these techniques addresses a long-standing challenge in electron microscopy: conventional TEM requires high vacuum and thin, solid specimens, making the observation of liquid-phase reactions impossible without specialized equipment [13]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these core technologies, their methodologies, and their applications within the broader context of nanomaterial synthesis research.

Core Technology Comparison

Microchip-based liquid cells and graphene liquid cells represent two advanced approaches to encapsulating liquid samples for TEM observation. Although they share a common goal, their designs, fabrication processes, and performance characteristics differ significantly.

Microchip-based liquid cells typically consist of two silicon microchips, each featuring an electron-transparent membrane, often made from amorphous silicon nitride (SiN) [13]. These chips are separated by a spacer to create a cavity that confines the liquid specimen. The fabrication relies on standard photolithography and etching processes, allowing for the integration of additional functionalities such as patterned electrodes for electrochemistry, heating elements for thermal control, and channels for fluid flow [13] [14]. This system is commercially available and widely adopted for its versatility.

Graphene liquid cells (GLCs), a more recent innovation, utilize one or more layers of graphene as the primary encapsulation material [15]. These cells are formed by sealing a small volume of liquid, often less than 0.01 picolitres, between two graphene sheets suspended across a holey carbon support film on a conventional TEM grid [13] [15]. This approach leverages graphene's exceptional properties, including its atomic thinness, high mechanical strength, and low atomic number.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Technical Specifications

| Feature | Microchip-based Liquid Cell | Graphene Liquid Cell (GLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Window Material | Silicon Nitride (SiN), typically 10-50 nm thick [13] | Graphene, atomically thin (~0.3 nm per layer) [15] |

| Typical Liquid Thickness | Tens of nanometers to a micrometer [13] | Extremely thin, often sub-100 nm [15] |

| Liquid Volume Capacity | Nanolitre scale [13] | Sub-picolitre scale (< 0.01 pL) [13] |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited by window and liquid thickness scattering [13] | Atomic resolution achievable; less scattering [15] |

| Additional Functionalities | Yes (e.g., flow, electrical biasing, heating) [13] | Limited; primarily imaging [13] |

| Sample Preparation | Involves chip assembly and loading [13] | Delicate; involves graphene transfer and encapsulation [15] |

| Compatibility | Requires dedicated TEM holder [13] | Compatible with standard TEM holders [15] |

Table 2: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Primary Applications

| Aspect | Microchip-based Liquid Cell | Graphene Liquid Cell (GLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Strengths | Versatile functionality (e.g., electrochemistry); larger liquid volume enables longer-term dynamic studies; established commercial systems [13]. | Superior spatial resolution; reduced beam scattering; minimal sample prep time with automated systems [16] [15]. |

| Key Limitations | Lower resolution due to thicker windows; higher electron beam scattering [13]. | Very small liquid volume limits reactant availability; difficult to handle and fabricate; limited functional control [13] [15]. |

| Ideal Applications | Electrochemical processes (e.g., battery studies); nanomaterial growth with reactant flow; biological processes requiring larger volumes [13] [14]. | High-resolution studies of nanomaterial dynamics, atomic-scale etching, and growth; imaging of pristine nanoparticles and biological macromolecules [15] [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Microchip-based Liquid Cell Workflow

The protocol for a standard microchip-encapsulated liquid cell experiment involves specific equipment and careful assembly to ensure success and vacuum integrity [13].

Key Materials and Equipment:

- Silicon microchips with low-stress SiN windows (e.g., 50 nm thick) [14].

- Specialized liquid cell TEM holder.

- Spacer material (e.g., metal or SiO₂).

- Syringe pump system for liquid injection (if flow is used).

- Nanoscale specimen of interest in solution.

Detailed Procedure:

- Chip Preparation: Inspect the silicon microchips for defects or contamination on the SiN window [13].

- Specimen Loading: Pipette a small droplet (e.g., 0.5-1 µL) of the liquid specimen onto the center of the bottom microchip's SiN window.

- Spacer Placement: If not pre-fabricated, place spacer materials around the liquid droplet to define the cell height.

- Cell Assembly: Carefully lower the top microchip onto the bottom chip, ensuring the SiN windows are aligned. The assembly is typically clamped within a specific holder to create a sealed chamber [14].

- Holder Insertion: Insert the fully assembled liquid cell into the dedicated TEM holder, connecting any fluidic or electrical ports.

- TEM Imaging: Insert the holder into the TEM and initiate imaging. Parameters like beam energy and dose rate must be optimized to minimize radiolysis while achieving sufficient contrast [13].

Graphene Liquid Cell Workflow

The preparation of GLCs is a delicate, multi-step process focused on creating sealed pockets of liquid between graphene layers [15].

Key Materials and Equipment:

- Holey amorphous carbon TEM grids (e.g., gold grids to prevent etching) [15].

- CVD graphene on a copper substrate.

- Etching solution (e.g., 1g sodium persulfate in 10mL deionized water) [15].

- Plasma cleaner (optional, for surface treatment).

Detailed Procedure:

- Graphene Cleaning: Clean the graphene-on-copper piece by washing it in warm acetone (~50°C) three times to remove residual poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [15].

- Grid Transfer: Place holey carbon TEM grids onto the graphene surface with the carbon film in contact with graphene. Apply a droplet of isopropanol to improve contact and allow to dry for several hours to ensure bonding [15].

- Copper Etching: Float the graphene-on-copper piece with adhered grids on the surface of the sodium persulfate solution. Etch overnight until the copper is fully dissolved, leaving the graphene suspended on the grids [15].

- Washing: Transfer the floating graphene-coated grids through three washes in clean deionized water to remove etchant residue. Finally, pick up the grids and dry them on filter paper [15].

- Liquid Encapsulation: Pipette a small droplet (e.g., 1-2 µL) of the nanomaterial solution onto a pristine graphene-coated grid. Use a second graphene-coated grid to cover the droplet, creating a sandwich structure. Capillary forces can form sealed pockets of liquid suitable for TEM imaging [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of LCTEM experiments requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details essential items and their functions for both microchip and graphene-based approaches.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Liquid Cell TEM Experiments

| Item | Function / Purpose | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| SiN Microchips | Forms the primary enclosure; SiN windows are electron-transparent and mechanically robust to withstand pressure differences [13] [14]. | Microchip-based |

| Graphene-on-Copper | Source material for creating atomically thin, electron-transparent windows that enable high-resolution imaging [15]. | Graphene Liquid Cell |

| Holey Carbon TEM Grids (Gold) | Support structure for graphene layers; gold is inert and prevents unwanted electrochemical etching during preparation [15]. | Graphene Liquid Cell |

| Spacer Material (e.g., SiO₂) | Defines the height of the liquid chamber in microchip cells, controlling liquid thickness [13]. | Microchip-based |

| Sodium Persulfate Solution | Aqueous etchant used to remove the copper substrate from CVD graphene without damaging the graphene itself [15]. | Graphene Liquid Cell |

| Patterned Electrodes (Pt) | Integrated into microchips to apply electrical potentials for in situ electrochemistry experiments (e.g., battery studies) [13] [14]. | Microchip-based |

Microchip-based and graphene liquid cells are powerful and complementary tools in the field of in situ TEM for nanomaterial synthesis. The choice between them depends on the specific research question: microchip cells offer functional versatility and control for studying complex electrochemical and dynamic processes, while graphene cells provide unparalleled spatial resolution for atomic-scale mechanistic studies [13] [15] [1]. Future developments are likely to focus on mitigating the current limitations of both techniques. For microchip cells, advances in membrane materials and design aim to reduce thickness and improve resolution [11]. For graphene cells, efforts are directed towards standardizing and automating the fabrication process to improve reliability and accessibility [16]. Furthermore, the integration of LCTEM with other characterization techniques, such as the correlative approach with cryo-atom probe tomography, represents a cutting-edge frontier for obtaining comprehensive nanoscale chemical and structural information from liquid-solid interfaces [17]. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly deepen our fundamental understanding of nanoscale dynamics in liquids and accelerate the rational design of next-generation nanomaterials.

In situ liquid cell Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) has emerged as a revolutionary technique for directly observing dynamic processes during nanomaterial synthesis and electrochemical reactions in liquid environments. This capability provides unprecedented insight into nucleation, growth, and degradation mechanisms at the nanoscale [6] [18]. The core technological achievement enabling these observations is the liquid cell, a microfluidic device that hermetically seals a thin liquid layer between electron-transparent windows while maintaining the high vacuum required for TEM operation. The performance and reliability of these liquid cells fundamentally depend on three essential components: silicon nitride membranes, spacers, and electrodes. These components collectively enable the creation of a controlled nanoscale experimental environment within the microscope, allowing researchers to apply stimuli such as electrical bias and track subsequent morphological and compositional changes in real-time [19]. This technical guide details the properties, functions, and operational considerations of these core components within the context of advanced nanomaterial synthesis research.

Silicon Nitride Membranes

Function and Properties

Silicon nitride (SiN(_x)) membranes serve as the primary electron-transparent window material in commercial liquid cell systems. Their critical function is to encapsulate the liquid sample, protecting the TEM column from contamination while allowing the electron beam to penetrate with minimal scattering. This enables high-resolution imaging of dynamic processes in the liquid phase [18]. These membranes are typically fabricated onto silicon support chips, which provide the necessary mechanical stability to withstand the pressure differential between the liquid cell and the microscope vacuum.

Technical Specifications and Beam Effects

A key technical consideration is membrane thickness, which typically ranges from 10 to 50 nanometers for the electron-transparent window regions [18]. However, a significant challenge identified in recent research is the electron beam-induced oxidation of SiN(x) membranes when immersed in water. Studies using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) have demonstrated that under high electron dose rates, SiN(x) chemically transforms into silicon oxide (SiO(x)) [20]. This oxidation process is accompanied by the release of nitrogen (N(2)) and oxygen (O(_2)) gas, which can create bubbles and potentially instigate further chemical reactions within the liquid cell. This effect must be carefully considered during experimental design, as it can alter the local chemical environment and influence the processes being observed [20].

Table 1: Characteristics and Considerations for Silicon Nitride Membranes

| Property | Typical Specification | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Silicon Nitride (SiN(_x)) | Provides mechanical strength and electron transparency. |

| Window Thickness | 10 - 50 nm [18] | Thinner membranes improve image resolution but reduce mechanical stability. |

| Key Challenge | Electron beam-induced oxidation to SiO(_x) in water [20] | Alters local chemistry and may release gas bubbles, confounding experiments. |

| Primary Function | Electron-transparent liquid encapsulation | Maintains vacuum integrity while allowing specimen imaging. |

Spacers

Role in Liquid Cell Configuration

Spacers are a fundamental component that defines the geometry of the liquid sample environment. They are placed between the two SiN(_x) membrane windows to create a cavity of controlled height for the liquid specimen. The precise configuration of these spacers determines the thickness of the liquid layer, which is a critical parameter for image resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

Types and Impact on Experimentation

Spacers can be fabricated from various materials, including silicon, silicon dioxide, or polymer films, and their dimensions can be precisely engineered. The liquid layer thickness, defined by the spacer height, typically ranges from a few hundred nanometers to over a micron [18]. This thickness is a compromise: thinner liquid layers, enabled by smaller spacers, reduce electron scattering and improve image contrast and spatial resolution. Thicker layers allow for more complex reaction environments but at the cost of increased noise and reduced resolution. Advanced liquid cell designs incorporate flow channels, which are integrated microfluidic networks defined by spacer patterns. These channels enable the continuous delivery of fresh reactants and removal of products during imaging, as demonstrated in platforms that allow simultaneous control of heating, biasing, and liquid flow [19]. This capability is vital for studying reaction kinetics and processes like nanoparticle growth under realistic synthesis conditions.

Electrodes

Integration and Functionality

Microfabricated electrodes are integrated into liquid cells to introduce electrochemical control and electrical bias into the nanoscale reaction environment. These electrodes enable in situ studies of electrochemical reactions critical to energy storage, conversion, and electrocatalysis [6] [19]. They are typically patterned via lithography onto the surface of the SiN(_x) membrane chips, creating a miniaturized electrochemical cell. A standard two-electrode setup is common, but more advanced three-electrode configurations, including a reference electrode, are increasingly available for more precise electrochemical control.

Advanced Configurations and Applications

The presence of electrodes allows researchers to apply potentials and observe dynamic processes such as electrochemical deposition, dendrite formation in batteries, and the evolution of electrocatalysts [6]. For instance, studies have utilized these systems to investigate copper nucleation on platinum electrodes and observe how electrolyte flow modulates dendrite growth—shorter under flow conditions and longer under static conditions due to ion depletion [19]. A significant recent advancement is the development of systems that incorporate a standard reference electrode, such as a Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode, placed outside the microscope. This design offers greater flexibility and better correlates nanoscale observations with bulk-scale electrochemical experiments, bridging a critical gap in the field [21]. Furthermore, cutting-edge platforms now provide simultaneous control over electrochemical bias, temperature, and liquid flow, creating a highly flexible system for mimicking real-world electrochemical environments [19].

Table 2: Electrode Configurations in Liquid Cell TEM

| Electrode Type | Configuration | Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Electrode | Working and Counter electrodes patterned on the chip. | Simplicity of design and integration. | Basic biasing experiments, observing electrodeposition. |

| Three-Electrode (On-chip) | Working, Counter, and Reference electrodes patterned on the chip. | Enables accurate potential control within the cell. | Precise electrochemical synthesis and degradation studies. |

| Three-Electrode (External Reference) | Working/Counter on-chip, Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) outside the microscope [21]. | Flexibility, uses standard electrochemistry equipment, improves correlation to bulk studies. | Benchmarking nanoscale reactions against known electrochemical data. |

Experimental Protocols for Liquid Cell Operation

Liquid Cell Assembly and Workflow

A standardized protocol is essential for obtaining reproducible and reliable data from in situ liquid cell TEM experiments. The following workflow outlines the key steps, from preparation to data analysis:

- Cell Cleaning: Meticulously clean the liquid cell holder and silicon chips with the patterned SiN(_x) membranes and integrated electrodes using appropriate solvents (e.g., acetone, isopropanol) and oxygen plasma treatment to remove organic contaminants.

- Spacer Definition: Apply a spacer material to one of the silicon chips to define the liquid cavity height. This can involve placing a solid spacer (e.g., a SiO(_2) fragment) or depositing a polymer film with a defined thickness.

- Liquid Injection: Pipette a small volume (typically 0.5 - 2 µL) of the liquid sample or precursor solution onto the membrane window of the bottom chip.

- Cell Sealing: Carefully align the top chip, membrane-side down, onto the bottom chip. The assembly is then clamped within the liquid cell holder, creating a hermetically sealed chamber.

- Holder Insertion: Insert the sealed liquid cell holder into the TEM column, ensuring all electrical contacts for biasing and/or heating are properly engaged.

- Experiment Initiation: Locate the region of interest at low electron dose rates to minimize beam effects. Begin the experiment by initiating data acquisition (video recording), and applying the desired external stimuli (electrical bias, heating, liquid flow).

- Post-situ Analysis: After the in situ experiment, disassemble the cell and often recover the sample for further ex situ analysis using techniques such as spectroscopy or atomic force microscopy to validate the in situ findings.

Protocol for Investigating Nanomaterial Electrodeposition

This specific methodology details an experiment for observing bias-induced nucleation and growth of metals, such as copper, on a working electrode.

- Objective: To visualize the real-time electrochemical nucleation and growth of copper nanostructures on a platinum working electrode under different flow conditions.

- Materials:

- Liquid cell holder with capabilities for biasing and flow.

- Silicon chips with patterned Pt working and counter electrodes.

- Spacers (e.g., ~1 µm thick).

- Electrolyte: 0.1 M Copper Sulfate (CuSO(_4)) in water.

- Reference electrode (if applicable), such as an external Ag/AgCl electrode [21].

- Method:

- Assemble the liquid cell with the Pt electrode chips and spacers following the standard workflow.

- Inject the CuSO(_4) electrolyte into the cell.

- Insert the holder into the TEM and locate the electrode edge at a low beam dose.

- Connect the potentiostat and set the desired potential/current parameters for copper reduction.

- Start video acquisition simultaneously with the application of an electrochemical bias (e.g., a negative potential sufficient to reduce Cu²⁺ to Cu⁰).

- Record the dynamic processes of nucleation, growth, and dendritic formation at the electrode interface.

- In a separate experiment, activate the liquid flow pump to introduce fresh electrolyte and observe how convective mass transport alters the growth morphology, noting the suppression of dendritic growth due to mitigated ion depletion [19].

- Data Analysis: Track particle trajectories and analyze growth rates from the recorded videos. Software tools like LEONARDO, a physics-informed generative AI model, can be employed to learn the complex diffusion and interaction of nanoparticles from thousands of extracted trajectories [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Liquid Cell TEM Experiments

| Item | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride Membrane Chips | Electron-transparent windows for liquid encapsulation. | Choose thickness based on resolution needs vs. robustness. Be aware of beam-induced oxidation [20]. |

| Spacer Material (e.g., SiO₂, Polymer) | Defines the height of the liquid cavity. | Determines liquid path length, a key factor for image quality. |

| Patterned Electrode Chips | Enable in situ electrochemical control and biasing. | Pt is a common electrode material. Designs can include working, counter, and reference electrodes. |

| Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions | Provide the chemical environment for electrochemical reactions or nanoparticle synthesis. | Concentration and pH must be carefully controlled. Examples include metal salts for electrodeposition. |

| Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) | Provides a stable potential reference for quantitative electrochemistry [21]. | Can be integrated on-chip or placed externally in advanced setups. |

| Liquid Cell Holder | Holds the chip assembly and provides electrical/fluidic connections to the outside. | Must be compatible with the TEM model and have ports for bias, heating, and flow. |

System Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and control logic of a state-of-the-art liquid cell TEM experiment with multiple in situ stimuli.

The sophisticated application of in situ liquid cell TEM for nanomaterial synthesis research is underpinned by the precise engineering and synergistic operation of its three core components: silicon nitride membranes, spacers, and electrodes. Continuous improvements in membrane stability, spacer design for controlled flow, and electrode integration with standard reference systems are pushing the boundaries of this technique. Furthermore, the growing integration of artificial intelligence, as seen in tools like LEONARDO for analyzing nanoparticle diffusion [22] and aquaDenoising for enhancing image quality [23], is set to revolutionize data analysis and extraction. As these components and computational methods advance, liquid cell TEM will continue to provide deeper, more quantitative insights into the dynamic processes of nanomaterial formation and transformation, solidifying its role as an indispensable tool in materials science and chemical research.

The controlled synthesis of nanomaterials represents a cornerstone of modern nanotechnology, with applications spanning catalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine. Despite decades of research, a fundamental challenge persists: the precise control over nanomaterial size, morphology, crystal structure, and surface properties remains elusive, primarily due to limitations in directly observing the dynamic growth processes at the atomic scale [1]. Classical and non-classical nucleation theories have attempted to explain the initial stages of material formation, yet the reality of atomic migration dynamics, interfacial evolution, and structural transformation during synthesis often deviates from these theoretical predictions [1].

The emergence of in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM), particularly liquid-phase TEM (LPTEM), has revolutionized our ability to probe these previously hidden processes. This technique overcomes the limitations of traditional ex situ characterization by enabling real-time observation and analysis of dynamic structural evolution during nanomaterial growth with atomic-scale resolution [1]. By providing a window into the liquid-phase synthesis environments where most nanomaterials are formed, in situ TEM has transformed our understanding of nucleation and growth mechanisms, moving the field from speculative models to direct experimental visualization [24]. This technical guide examines how atomic-scale observation is refining classical theories of nucleation and growth, with a specific focus on methodologies, key insights, and experimental protocols within the broader context of in situ TEM liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis research.

Classical Theories and Modern Challenges

Foundational Theoretical Frameworks

Traditional understanding of crystal formation has been guided by several foundational theories that describe different pathways from disordered units to ordered structures:

- Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT): Describes the formation of crystal embryos from liquid phase via nucleation, where small nuclei tend to dissolve unless they exceed a critical size, thereby overcoming the free energy barrier [25].

- Non-classical Crystallization Pathways: Encompasses mechanisms such as oriented attachment, coalescence, and pre-nucleation cluster formation that deviate from CNT [25].

- Growth Mode Theories: Include Volmer-Weber (island formation), Frank-van der Merwe (layer-by-layer), and Stranski-Krastanov (layer-then-island) models for thin film growth [25].

- Wulff Construction: A geometrical principle used to predict the equilibrium shape of crystals based on surface energy minimization [25].

The Nanoparticle Paradigm Challenge

Nanoparticles inhabit an intermediate length scale that presents unique challenges for theoretical modeling. Their size is comparable to environmental factors such as solvent molecules and ligands, creating complex multiscale coupling and nonadditivity in interactions [25]. This complexity means that nanoparticle crystallization often proceeds through more complicated pathways than either atomic systems or micron-sized colloids, requiring direct observation rather than theoretical prediction alone.

In Situ TEM Methodologies: A Technical Framework

The application of in situ TEM to nucleation and growth studies relies on specialized instrumentation that enables the creation of microenvironmental conditions within the high-vacuum environment of a transmission electron microscope.

Liquid Cell Architectures

Liquid Cell TEM Architectures

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for In Situ TEM Liquid Cell Experiments

| Item | Function | Technical Specifications | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based E-chips | Microfabricated silicon chips with electron-transparent windows to encapsulate liquid samples | 500 × 50 μm windows with 50 nm thick amorphous silicon nitride (SiN) films [26] | General liquid-phase nanomaterial synthesis studies [26] |

| Graphene Liquid Cells | Advanced encapsulation using graphene sheets for superior signal-to-noise ratio | Single or few-layer graphene, liquid thickness up to 100 nm [27] | High-resolution imaging of atomic-scale processes [27] |

| Heating Liquid Cells | Precision temperature control for studying thermal effects on nucleation and growth | Resistive heating elements integrated into silicon substrate, range: RT to 100°C [26] | Temperature-dependent kinetic studies of gold nanoparticle formation [26] |

| Precursor Solutions | Chemical reactants dissolved in appropriate solvents to initiate nanomaterial growth | Concentration typically 0.1-100 mM in aqueous or organic solvents [28] [24] | Metal salt solutions (e.g., HAuCl₄, AgNO₃) for noble metal nanoparticle synthesis [24] |

| Stabilizing Ligands | Surface-active molecules to control growth kinetics and prevent aggregation | Polymers (e.g., PVP), surfactants (e.g., CTAB), thiolated compounds [27] | Shape-controlled synthesis of anisotropic nanostructures [27] |

Advanced Imaging and Analysis Modalities

The integration of complementary characterization techniques with in situ TEM has significantly expanded its analytical capabilities:

- Scanning TEM (STEM): Enables high-resolution imaging with Z-contrast, particularly useful for visualizing heavy elements in liquid environments [26].

- Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS): Provides information about electronic structure and chemical composition during growth processes [1].

- Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS): Allows elemental mapping and compositional analysis of evolving nanostructures [1].

- Fast Electron Tomography: Enables 3D reconstruction of nanoparticle assemblies in their native liquid environment, revealing structural details often obscured in 2D projections [27].

Quantitative Insights into Nucleation and Growth Dynamics

Direct observation through in situ TEM has yielded substantial quantitative data on nucleation and growth parameters across diverse material systems.

Nucleation Dynamics and Phase-Dependent Behavior

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Nucleation and Growth Dynamics in Different Microenvironments

| Material System | Microenvironment | Nucleation Mechanism | Growth Rate | Final Structure Characteristics | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe-based heterostructures [28] | Oil phase | Au formation on CdSe surface | Not specified | ~52% polycrystalline, balance single crystal | Phase-dependent interfacial energy |

| CdSe-based heterostructures [28] | Water phase | AuSe nucleation | Not specified | ~79% polycrystalline, balance single crystal | Aqueous phase chemistry |

| CdSe-based heterostructures (in situ case) [28] | Controlled liquid cell | Two-step amorphous-to-crystalline transition | Not specified | ~76% single crystals | Reduced kinetic barriers |

| Au nanoparticles on MoS₂ [29] | Aqueous solution (pristine MoS₂) | Galvanic displacement | Between diffusion-limited and reaction-limited | Larger size distribution at edges | Substrate atomic structure |

| Au nanoparticles on MoS₂ [29] | Aqueous solution (S-vacancy MoS₂) | Enhanced nucleation at vacancy sites | Diffusion and coalescence-dominated | Improved size control | Defect-mediated interactions |

Experimental Protocol: Temperature-Controlled Nucleation Study

A detailed methodology for investigating temperature effects on nanoparticle nucleation and growth exemplifies the sophisticated protocols developed for in situ TEM studies [26]:

- Microscope Alignment: Configure STEM-HAADF imaging mode with small condenser aperture and spot size to minimize electron dose rate and reduce radiolysis effects.

- Liquid Cell Assembly:

- Handle MEMS E-chips carefully using carbon-tip tweezers to prevent damage to SiN windows.

- Pipette 50-100 nL of precursor solution (e.g., 1 mM HAuCl₄ in water) onto the bottom E-chip.

- Carefully place the spacer chip and top E-chip to create a sealed liquid enclosure.

- Insert the assembled liquid cell into the specialized TEM holder with heating capabilities.

- Temperature Calibration: Establish correlation between setpoint temperature and actual sample temperature using calibrated standards.

- In Situ Experimentation:

- Initiate time-resolved imaging at frame rates appropriate for capturing nucleation events (typically 1-10 fps).

- Ramp temperature to desired setpoint (e.g., 25°C to 95°C) while maintaining continuous imaging.

- Monitor nucleation density, growth rates, and morphological evolution in real-time.

- Data Analysis:

- Apply automated image processing algorithms to extract quantitative data on nanoparticle size, number density, and growth kinetics.

- Correlate temperature parameters with nucleation rates and growth mechanisms.

Case Studies: Connecting Observation to Theory

Metal-Semiconductor Heterostructure Formation

The synthesis of CdSe-based heterostructures provides compelling evidence for microenvironment-dependent nucleation pathways. In situ TEM revealed that the same material system follows dramatically different formation mechanisms depending on the solvent phase [28]. In oil-phase microenvironments, Au directly forms on CdSe surfaces, while in water-phase environments, AuSe compounds nucleate instead. This phase-dependent behavior resulted in significantly different final crystalline structures, with water-phase synthesis producing predominantly polycrystalline nanoparticles (∼79%) compared to oil-phase (∼52%) [28]. Remarkably, under optimized in situ conditions with controlled reaction parameters, the proportion of single crystals increased substantially to ∼76%, demonstrating the critical importance of precise microenvironment control [28].

Substrate-Directed Nucleation and Growth

The role of two-dimensional substrates in directing nucleation processes was elegantly demonstrated through in situ TEM studies of Au nanoparticle formation on MoS₂ nanoflakes [29]. Real-time observation revealed that growth mechanisms on pristine MoS₂ surfaces operate in a regime between diffusion-limited and reaction-limited models, influenced by electrochemical Ostwald ripening. More importantly, significant differences emerged between edge and interior sites: Au particles at MoS₂ edges exhibited larger size distribution and greater orientation variation compared to those on basal planes [29]. Sulfur vacancies dramatically altered growth dynamics by inducing Au particle diffusion and coalescence during growth. Density functional theory calculations correlated these observations with atomic-scale interactions, showing that exposed molybdenum atoms at edges with dangling bonds strongly interact with Au atoms, while sulfur atoms on interiors with no dangling bonds interact weakly [29].

Nanoparticle Assembly and Superlattice Formation

Liquid-phase TEM has provided unprecedented insights into the non-classical crystallization pathways of nanoparticle superlattices. Direct imaging revealed the existence of pre-nucleation precursors in nonclassical crystallization and surface energy-dependent growth patterns [25]. These observations showed that nanoparticle assembly follows pathways distinct from atomic crystals, with capillary waves and fluctuating dynamics playing significant roles in structure formation. The technology enabled charting of phase coordinates and thermodynamic quantities at the nanoscale, providing experimental validation for theoretical frameworks [25].

Emerging Frontiers and Computational Integration

Advanced 3D Structural Analysis

Traditional TEM analysis is limited to 2D projections, but recent advances in liquid-phase electron tomography now enable quantitative 3D structural analysis of nanoparticle assemblies under native conditions [27]. This approach combines fast data acquisition in commercial liquid-cells with specialized alignment and reconstruction workflows to overcome challenges related to limited tilt range, image distortion, and environmental noise. Comparative studies have revealed significant structural differences between dried and liquid-state nanoparticle assemblies, with liquid-phase configurations exhibiting less compact and more distorted structures with expanded interparticle distances [27]. These findings emphasize the critical importance of characterizing nanomaterial formation in native environments rather than relying on ex situ analysis of dried specimens.

AI-Enhanced Analysis of Nanoparticle Dynamics

The complex stochastic motion of nanoparticles in liquid environments presents significant challenges for traditional analytical methods. Recent research has introduced LEONARDO, a deep generative model that leverages physics-informed loss functions and attention-based transformer architecture to learn nanoparticle diffusion from LPTEM trajectories [30]. This AI framework successfully captures statistical properties reflecting the heterogeneity and viscoelasticity of the liquid cell environment, enabling the identification of complex motion patterns that combine Gaussian and non-Gaussian characteristics. By serving as a black-box simulator, this approach can generate synthetic trajectories that replicate experimental observations across different electron beam dose rates and particle sizes, providing a powerful tool for understanding nanoscale interactions [30].

Research Evolution Pathway

The integration of in situ TEM liquid cell technology into nanomaterials research has fundamentally transformed our understanding of nucleation and growth processes. By providing direct access to atomic-scale dynamics in native liquid environments, this approach has revealed complex pathways that often diverge from classical theoretical predictions. The methodology has evolved beyond simple observation to encompass sophisticated temperature control, 3D tomographic reconstruction, and AI-enhanced analysis of stochastic behaviors.

These technical advances have established a new paradigm for nanomaterials synthesis research, where direct visualization informs rational design rather than relying on empirical optimization. As computational integration deepens and instrumental capabilities expand, the synergy between atomic-scale observation and theoretical frameworks will continue to drive innovations in controlled nanomaterial fabrication, enabling increasingly sophisticated applications across catalysis, energy storage, biomedicine, and beyond.

Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Nanomaterial Research

In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) has emerged as a transformative tool for the real-time observation and analysis of dynamic processes at the nanoscale. This capability is particularly valuable for investigating electrochemical reactions and nanomaterial synthesis in liquid environments. The development of specialized microchip-based liquid cells has been instrumental in these advances, allowing researchers to achieve high-resolution imaging of nanoscale processes in real time under controlled electrochemical conditions [14] [1]. These systems overcome the limitations of traditional ex situ characterization techniques by encapsulating the liquid sample between electron-transparent membranes, enabling direct observation of phenomena such as nucleation, growth, and phase transformations in nanomaterials [14] [1].

The integration of electrochemical control within these liquid cells represents a significant technical advancement, providing a platform to study electrochemical reactions in liquid with a standard scanning electron microscope (SEM) or TEM [14]. This technical guide details the design principles, fabrication methodologies, and experimental protocols for a microchip-based liquid cell system for electrochemical experiments, framed within the broader context of in situ TEM liquid cell nanomaterial synthesis research.

Core System Design and Components

Design Principles and Architecture

The microchip-based liquid cell system is designed as a vacuum-sealed electrochemical cell that can be inserted and operated within a standard SEM or TEM. The central component is a microfabricated chip featuring a thin (approximately 50 nm) electron-transparent window, typically made of silicon-rich silicon nitride (SiN(_x)), which is strong enough to withstand the pressure difference between the liquid sample and the microscope vacuum [14]. Lithographically defined platinum microelectrodes are integrated onto the chip surface, providing the necessary interfaces for applying electrical potentials and measuring currents within the liquid environment [14]. The system also incorporates the possibility for an electrochemical reference electrode and a counter electrode, enabling precise control over electrochemical conditions [14].

The complete setup consists of a polycarbonate chip holder with Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) seals and spacers, the electrochemical (EC) chip itself with the membrane and electrodes, and a clamping lid to ensure a secure and leak-proof assembly [14]. The holder includes a central channel leading to a reservoir under the chip and an offshoot channel for a reference electrode inlet [14]. This design allows the system to be used and reused multiple times by simply flushing out the liquid and exchanging the EC-SEM chip [14].

Key Components and Materials

Table 1: Core Components of the Microchip-based Liquid Cell

| Component | Material/Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Electron-Transparent Window | 50 nm thick Si-rich Silicon Nitride (SiN(_x)) | Seals liquid while allowing electron beam transmission for imaging and analysis [14]. |

| Microelectrodes | Lithographically patterned Platinum (Pt) | Serve as Working Electrode (WE) and Counter Electrode (CE) to apply potential and measure current [14]. |

| Reference Electrode | Customizable (e.g., Ag/AgCl) | Provides a stable, known potential for accurate control of the working electrode potential [14]. |

| Spacer Layer | PDMS or Silicon (50 nm - several µm) | Defines the height of the liquid chamber, controlling liquid volume and flow dynamics [14] [31]. |

| Chip Holder & Seals | Polycarbonate, PDMS | Provides structural support, fluidic connections, and maintains vacuum integrity [14]. |

Fabrication and Assembly Protocol

Microchip Fabrication

The fabrication of the central microchip begins with a silicon wafer. The process involves depositing a thin layer of Si-rich silicon nitride (SiN(x)) which will form the electron-transparent window. Photolithography and etching techniques are used to define the window area and pattern the platinum microelectrodes on the chip surface. The backside of the silicon wafer is typically etched away to release the free-standing SiN(x) membrane in the window region [14].

System Assembly

The assembly process must be performed with precision to ensure a leak-proof seal capable of maintaining the pressure differential between the liquid and the microscope vacuum:

- Cleaning: The EC chip and all holder components are thoroughly cleaned.

- Sealing: The EC chip is placed in the rectangular recession of the polycarbonate holder. PDMS seals and spacers are positioned to define the liquid chamber height and provide a gasket.

- Clamping: A clamping lid is secured to press the chip against the seals, creating a vacuum-tight enclosure. The system must be leak-checked in an external vacuum station before insertion into the microscope [14] [31].

Experimental Characterization and Applications

Beam Current Characterization

A crucial initial characterization is measuring the electron beam current deposited in the liquid sample, as this directly affects the experiments by inducing chemical reactions and localized heating [14]. Measurements are performed by comparing the beam current in high vacuum to the current passing through the liquid cell. One study found that most current passes through the cell, with about 5% lost to backscatter; at lower acceleration voltages, a fraction is also lost to secondary electron emission [14]. This characterization is essential for understanding and quantifying beam effects.

Key Experimental Applications

Electroless Deposition

The system can be used to induce non-spontaneous chemical reactions using the electron beam, a process known as Liquid Phase Electron-Beam-Induced Deposition (LP-EBID) [14].

- Protocol: The liquid cell is filled with a solution for electroless plating, such as a solution containing 2.5 g nickel (II) sulfate hexahydrate and 2.5 g sodium hypophosphite monohydrate dissolved in 50 ml deionized water [14].

- Procedure: The electron beam is scanned over the window area. The deposition of nickel onto the SiN(_x) window is monitored in real-time. The rate and morphology of deposition are dependent on the electron beam current density [14].

Table 2: Summary of Electroless Deposition Experimental Parameters and Outcomes

| Parameter | Specification | Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Solution | 2.5g NiSO₄·6H₂O, 2.5g NaH₂PO₂·H₂O in 50ml DI H₂O | Electron beam induces deposition of Ni on the SiN(_x) window [14]. |

| Beam Effect | Increased current density | Leads to increased deposition rate of nickel [14]. |

| Imaging Mode | Large-Field-Detector (LFD) in low vacuum mode | Provides comparable or better imaging than backscatter detector for this application [14]. |

In Situ Electrolysis

The integrated electrodes enable the study of electrochemical reactions such as electrolysis, where electrical energy drives a non-spontaneous chemical reaction.

- Protocol: The cell is filled with an electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M H₂SO₄) [14].

- Procedure: A potential difference is applied between the two platinum electrodes to induce electrolysis of water. The current between the electrodes is measured as a function of time. The formation of gas bubbles (hydrogen and oxygen) is observed directly via SEM or TEM imaging, demonstrating the system's ability to withstand gas generation [14].

Table 3: Summary of Electrolysis Experimental Parameters and Outcomes

| Parameter | Specification | Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte | 0.1 M H₂SO₄ aqueous solution | Application of potential induces electrolysis, generating H₂ and O₂ gas bubbles [14]. |

| Electrodes | Integrated Pt microelectrodes | Survive bubble generation, proving robustness of the setup [14]. |

| Key Result | Real-time observation | Bubbles are imaged directly, providing insight into nucleation and growth dynamics [14]. |

Hydrodynamic Considerations in Flow Cells

For flow cell systems, understanding reagent mixing is critical for controlling chemical reactions. Hydrodynamic characterization can be performed by monitoring transmitted electron intensity while flowing a solution with a strong electron-scattering contrast agent [32]. Numerical models of solute transport have shown that the geometry of the flow channel dictates whether convective or diffusive transport dominates, allowing for control over the spatio-temporal reactant concentration at the nanoscale [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Liquid Cell EC-TEM

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Salts Solution | Precursor for electroless deposition studies. Provides metal ions for electron-beam-induced reduction [14]. | LP-EBID of Nickel: Solution of NiSO₄ and NaH₂PO₂ for studying electron-beam-induced metal deposition [14]. |

| Aqueous Electrolytes | Enable electrochemical reactions by providing ionic conductivity in the liquid cell [14] [33]. | Electrolysis: 0.1 M H₂SO₄ used to study gas bubble formation from water splitting [14]. |

| Lithium Ion Electrolytes | Study energy storage materials and mechanisms like SEI formation under operando conditions [33]. | Battery Research: LiPF₆ in EC/DEC electrolyte for visualizing electrode-electrolyte interfaces in Li-ion batteries [33]. |

| Thermoresponsive Polymers | Study of phase transitions and self-assembly of soft matter in liquid environments [31]. | Polymer Science: Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) to observe lower critical solution temperature (LCST) behavior [31]. |

| Silicon Nitride (SiN(_x)) | Electron-transparent membrane material. Provides mechanical strength to withstand pressure differential [14] [31]. | Standard window material for commercial and custom liquid cells. Thickness typically 50-100 nm [14] [31]. |

| Platinum (Pt) | Material for microfabricated electrodes. Chosen for its chemical inertness and excellent electrochemical properties [14]. | Standard electrode material for working, counter, and reference electrodes in microchips [14]. |

The microchip-based liquid cell for electrochemical control represents a powerful platform for advancing in situ TEM and SEM research. By integrating microfabricated electrodes with electron-transparent windows, this system enables high-resolution observation and manipulation of electrochemical processes and nanomaterial synthesis in liquid environments. The precise design, careful fabrication, and thorough characterization of beam-effects are critical for obtaining reliable quantitative data. As these methodologies continue to evolve, integrating advanced data analysis and correlative techniques, they hold great potential for driving breakthroughs in nanotechnology, materials science, and drug development by providing unprecedented insight into dynamic nanoscale phenomena.