Imaginary Phonon Modes: How Force Constants Reveal Material Instabilities and Guide Discovery

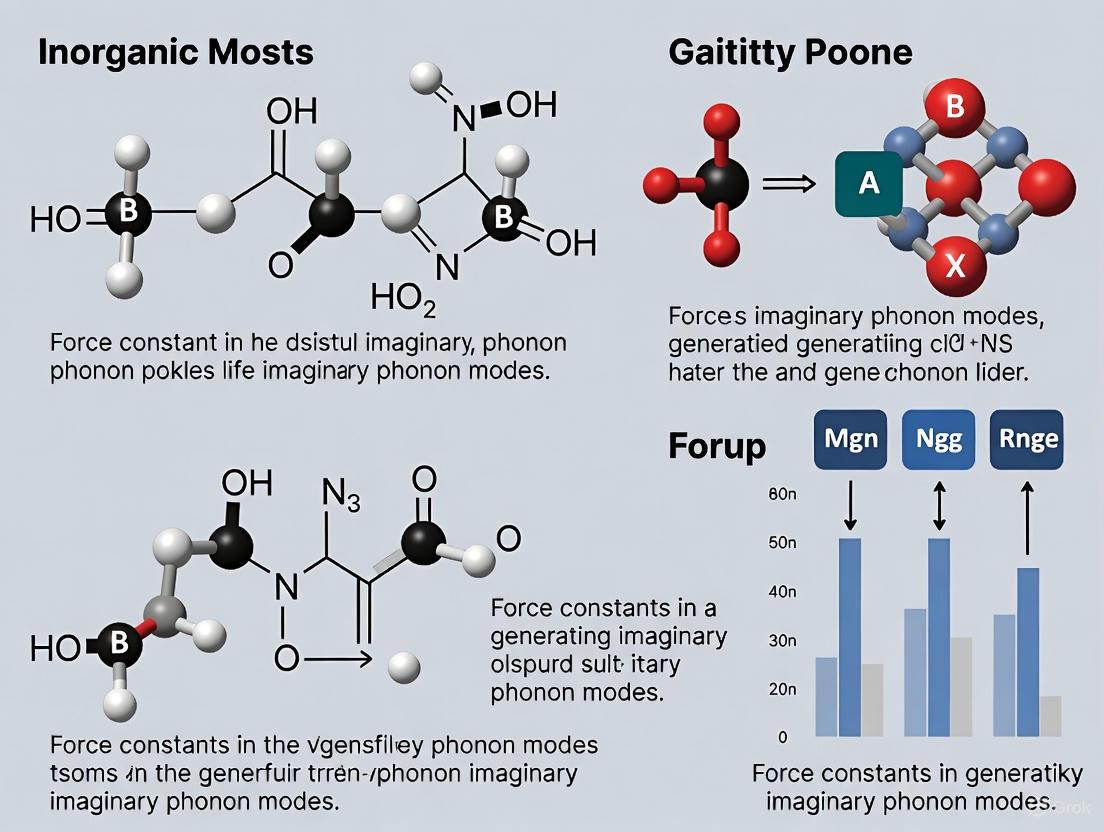

This article explores the critical role of interatomic force constants (IFCs) in generating and interpreting imaginary phonon modes—key indicators of dynamic instability in materials.

Imaginary Phonon Modes: How Force Constants Reveal Material Instabilities and Guide Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of interatomic force constants (IFCs) in generating and interpreting imaginary phonon modes—key indicators of dynamic instability in materials. We cover the foundational theory, from the harmonic approximation to anharmonic corrections, and detail modern computational methods, including high-throughput workflows and machine learning potentials, for calculating IFCs. The article also addresses troubleshooting common computational challenges and validating predictions against experimental spectroscopic data. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current advancements to enable the accurate prediction of phase transitions and the discovery of metastable materials for applications in thermoelectrics, catalysis, and drug development.

The Physics of Imaginary Phonons: Unstable Frequencies and Force Constants

Imaginary phonons, evidenced by negative eigenvalues in lattice dynamical matrices, are a definitive signature of structural instability in crystalline materials. This technical guide examines the fundamental role of force constants in generating these imaginary phonon modes, framing their existence not as computational artifacts but as physical indicators that a crystal structure resides at a saddle point, rather than a minimum, on the potential energy surface. We detail the mathematical foundation connecting the Hessian matrix to phonon frequencies, present validated computational protocols for detecting and interpreting these instabilities, and provide systematic methodologies for guiding unstable structures toward stable configurations. Within the broader thesis of force constant research, this review establishes that imaginary phonon analysis, particularly when accelerated by modern machine learning potentials, provides a powerful, rational pathway for crystal structure prediction and the discovery of metastable polymorphs.

The dynamical stability of a crystal structure is fundamentally governed by the curvature of the potential energy surface (PES) at its equilibrium configuration. This curvature is encoded in the force constant matrix, a mathematical entity whose eigenvalues determine the vibrational—or phonon—spectrum of the material. Within the harmonic approximation, the force constants are the second-order derivatives of the PES, defining the energetic cost of infinitesimal atomic displacements. When these force constants produce negative eigenvalues upon diagonalization of the dynamical matrix, the resultant phonon frequencies are imaginary, signaling a structural instability. The core thesis of this research is that force constants are not merely computational outputs but the fundamental determinants of crystal stability, and a rigorous analysis of the imaginary phonons they generate provides a rational roadmap for navigating the PES to discover physically realizable, dynamically stable structures [1] [2].

Mathematical Foundation: From the Hessian to Imaginary Frequencies

The journey from interatomic forces to phonon frequencies begins with the construction of the force constant matrix. In the context of a periodic crystal, this is generalized to the dynamical matrix.

The Force Constant and Dynamical Matrices

The potential energy ( E ) of an atomic system can be expanded as a Taylor series in atomic displacements: [ E = E0 + \sum{p\alpha i} \frac{\partial E}{\partial u{p\alpha i}} u{p\alpha i} + \frac{1}{2} \sum{p\alpha i, p'\alpha' i'} \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial u{p\alpha i} \partial u{p'\alpha' i'}} u{p\alpha i} u{p'\alpha' i'} + \cdots ] where ( u{p\alpha i} ) is the displacement of atom ( \alpha ) in the unit cell at ( \mathbf{R}p ) in the Cartesian direction ( i ) [3]. The matrix of force constants, also known as the Hessian, is defined as: [ \Phi{i\alpha, i'\alpha'}(\mathbf{R}p, \mathbf{R}{p'}) = \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial u{p\alpha i} \partial u{p'\alpha' i'}}. ] For a periodic crystal, the dynamical matrix ( D(\mathbf{q}) ) at wavevector ( \mathbf{q} ) is the Fourier transform of the force constant matrix: [ D{\alpha i, \alpha' i'}(\mathbf{q}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{m\alpha m{\alpha'}}} \sum{p'} \Phi{i\alpha, i'\alpha'}(0, \mathbf{R}{p'}) e^{-i\mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{R}{p'}}. ] The eigenvalues of the dynamical matrix ( \lambda\mathbf{q} ) are related to the phonon frequencies ( \omega\mathbf{q} ) by ( \omega\mathbf{q} = \sqrt{\lambda_\mathbf{q}} ) [2].

The Physical Interpretation of Negative Eigenvalues

A negative eigenvalue ( \lambda\mathbf{q} < 0 ) implies an imaginary phonon frequency ( \omega\mathbf{q} = i\sqrt{|\lambda_\mathbf{q}|} ). Mathematically, this signifies a negative curvature of the PES along the direction of the corresponding eigenvector. Physically, the structure is not at a minimum but at a saddle point. A displacement of the atoms along this "soft mode" will lower the system's energy, driving a symmetry-breaking structural distortion toward a dynamically stable configuration [2]. This relationship is foundational for connecting computational output to material behavior.

Table 1: Mathematical Interpretation of Phonon Frequency Eigenvalues

| Eigenvalue (λ) | Phonon Frequency (ω) | Curvature of PES | Structural State |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( \lambda > 0 ) | ( \omega > 0 ) (Real) | Positive Curvature | Local Minimum (Stable) |

| ( \lambda < 0 ) | ( \omega = i\sqrt{|λ|} ) (Imaginary) | Negative Curvature | Saddle Point (Unstable) |

Computational Detection and Analysis

Accurately computing phonon band structures is essential for identifying imaginary modes and assessing dynamic stability.

Methodological Considerations

Supercell Size Convergence: The choice of supercell size is critical. A supercell that is too small may fail to capture long-range interactions, leading to spurious imaginary frequencies that are numerical artifacts rather than true instabilities. Studies on monolayer MoS₂ demonstrate that a 5×5×1 supercell is sufficient for convergence, whereas smaller 3×3×1 and 4×4×1 supercells exhibit unphysical imaginary frequencies [4].

The Center and Boundary Phonon (CBP) Protocol: For high-throughput screening, calculating the full phonon band structure is computationally expensive. The CBP protocol offers an efficient alternative by evaluating the Hessian matrix for a 2×2 supercell. This method assesses phonon stability at the Brillouin zone center (Γ-point) and specific high-symmetry boundaries, providing a reliable approximation of dynamic stability with a significantly reduced computational cost [5].

A Structured Workflow for Stability Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for diagnosing and addressing imaginary phonons, integrating the core concepts of the force constant matrix and the CBP protocol.

Diagram 1: Workflow for diagnosing and treating imaginary phonons.

Experimental Protocols: From Instability to Stability

When a true instability is identified, it can be leveraged as a guide to discover new stable polymorphs.

The Following Imaginary Phonon Mode (FIPM) Workflow

The FIPM approach is a systematic recursive procedure for crystal structure prediction [1]:

- Global Structure Search: Generate a wide pool of candidate crystal structures through an ab-initio random structure search or similar method.

- Geometry Optimization: Relax each candidate structure to the nearest local minimum on the PES.

- Lattice Dynamics Calculation: Perform a phonon calculation on the optimized structure to classify it as dynamically stable or unstable.

- Mode Displacement and Relaxation: For every structure exhibiting imaginary modes, displace the atomic coordinates along the eigenvector of the most unstable phonon mode. The displacement magnitude is typically chosen to produce a maximum atomic displacement of ~0.1 Å [5].

- Recursive Application: Feed the newly obtained distorted structures back into step 2, repeating the process until no imaginary frequencies remain. This workflow can be fully automated and significantly accelerated using machine learning potentials [1].

The CBP Protocol for Structure Generation

This protocol, widely used for 2D materials, provides a specific implementation of the FIPM philosophy [5]:

- Hessian Calculation: For a given input structure, compute the Hessian matrix of a 2×2 supercell.

- Instability Identification: Diagonalize the Hessian to find eigenvalues. A negative eigenvalue confirms a dynamic instability.

- Atomic Displacement: Displace all atoms in the supercell along the eigenvector corresponding to the unstable mode.

- Structure Relaxation: Without symmetry constraints, fully relax the atomic positions and the cell shape of the distorted supercell.

- Validation: Perform a final phonon calculation on the resulting relaxed structure to confirm dynamic stability. Application of this protocol to 137 unstable 2D materials successfully yielded dynamically stable crystals in 49 cases, with properties like electronic band gaps differing significantly from the original unstable structures [5].

Diagram 2: The fundamental path from instability to stability via symmetry breaking.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Protocols for Imaginary Phonon Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DFPT | Computational Method | Efficiently calculates second-order force constants and phonon band structures directly from electronic structure. |

| Finite Displacement Method | Computational Method | Constructs the force constant matrix by applying small atomic displacements in a supercell and calculating forces. |

| CBP Protocol | Computational Protocol | Provides a high-throughput stability screening test by evaluating phonons only at the Brillouin zone center and boundary [5]. |

| FIPM Approach | Computational Workflow | A systematic, recursive procedure for guiding unstable structures to stable minima by following imaginary phonon modes [1]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Computational Accelerator | Trained on DFT data, MLPs drastically reduce the cost of energy and force calculations, enabling complex searches on the PES [1] [3]. |

| VASP, ABINIT, Quantum ESPRESSO | Software Package | First-principles electronic structure codes used for computing the underlying energies and forces for force constant matrices. |

Imaginary phonons, rooted in the negative eigenvalues of the force constant matrix, are precise indicators of structural instability that provide a rational pathway for crystal structure prediction. The rigorous computational protocols outlined—from the foundational FIPM workflow to the efficient CBP test—demonstrate that these instabilities are not dead ends but rather signposts directing researchers toward lower-energy, dynamically stable configurations. The integration of machine learning potentials is poised to further accelerate this exploratory process. Therefore, within the broader thesis on the role of force constants, the analysis of imaginary phonon modes stands as a cornerstone technique for the systematic discovery and design of novel functional materials.

Force Constants as the Second Derivative of the Potential Energy Surface

In computational chemistry and materials science, the concept of the potential energy surface (PES) is fundamental to understanding and predicting the behavior of atomic systems. The PES describes the energy of a system as a function of the positions of its constituent atoms. Within this framework, force constants emerge as critical mathematical entities, formally defined as the second derivatives of the PES with respect to atomic displacements. These constants form the foundation for analyzing vibrational dynamics, harmonic phonons, and lattice mechanical properties across diverse materials, from simple molecules to complex crystalline structures [3].

The calculation and application of force constants are particularly crucial for investigating dynamical stability through the identification of imaginary phonon modes. These modes, indicated by negative frequencies in phonon dispersion calculations, signal structural instabilities and potential phase transitions. The precision of force constant calculations directly impacts the reliability of such predictions, making methodological advancements in this area essential for accurate materials modeling and drug development research where stability assessment is critical [6].

This technical guide examines the fundamental role of force constants as second derivatives of the PES, detailing computational methodologies for their extraction, their critical relationship to imaginary phonon modes, and advanced research applications. We provide structured comparisons of computational approaches, detailed experimental protocols, and specialized toolkits to support researchers in implementing these techniques effectively.

Fundamental Theory and Mathematical Foundation

The Potential Energy Surface and Its Derivatives

The potential energy surface represents the energy landscape of an atomic system, where the configuration space is defined by the positions of all atoms. Mathematically, for a system with N atoms, the PES is a 3N-dimensional hypersurface. The second-order force constants, also known as the Hessian matrix elements, are defined as:

[ \Phi{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial xi \partial xj} = -\frac{\partial Fi}{\partial x_j} ]

where (E) is the potential energy, (xi) and (xj) are atomic displacement coordinates, and (F_i) is the force on coordinate (i) [6] [3]. Within the harmonic approximation, which assumes a parabolic shape of the PES near equilibrium, these second derivatives fully characterize the vibrational properties of the system.

In crystalline solids, this formulation extends to the dynamical matrix, which is the Fourier transform of the force constant matrix. Diagonalization of this matrix yields phonon frequencies ((\omega)) and their corresponding polarization vectors for each wave vector ((\mathbf{q})) in the Brillouin zone [3]:

[ D(\mathbf{q}) \epsilon{\mathbf{q}} = \omega^2(\mathbf{q}) \epsilon{\mathbf{q}} ]

From Force Constants to Phonons and Imaginary Modes

The eigenvalues resulting from the diagonalization of the dynamical matrix represent the squares of the phonon frequencies. When all force constants are physically meaningful and the structure is dynamically stable, all eigenvalues ((\omega^2)) are positive, yielding real phonon frequencies. However, when the PES curvature is negative along certain vibrational directions, the resulting negative eigenvalues produce imaginary phonon frequencies (mathematically represented as negative (\omega^2) or imaginary (\omega)) [6].

These imaginary frequencies directly reflect instabilities in the crystal structure, indicating that the current atomic configuration corresponds to a saddle point rather than a true minimum on the PES. The accurate calculation of force constants is therefore essential for reliably identifying these instabilities and predicting phase transitions or structural rearrangements.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Quantities in Force Constant Analysis

| Quantity | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Force Constant Matrix | (\Phi{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial xi \partial x_j}) | Measures curvature of PES; determines vibrational frequencies |

| Dynamical Matrix | (D{ab}^{\alpha\beta}(\mathbf{q}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ma mb}} \sum{\mathbf{R}} \Phi_{ab}^{\alpha\beta}(\mathbf{R}) e^{i\mathbf{q}\cdot\mathbf{R}}) | Fourier transform of force constants; determines phonon dispersion |

| Phonon Frequency | (\det[D(\mathbf{q}) - \omega^2(\mathbf{q})I] = 0) | Square root of eigenvalues of dynamical matrix |

| Imaginary Phonon Mode | (\omega^2 < 0) | Indicates structural instability; negative PES curvature |

Computational Methodologies for Force Constant Calculation

Finite-Displacement Approach

The finite-displacement method remains one of the most widely used approaches for calculating force constants from first principles. This method involves systematically displacing atoms from their equilibrium positions and computing the resulting forces through quantum mechanical calculations, typically using Density Functional Theory (DFT) [6] [7]. The force constants are then derived from the force-displacement relationships through central difference formulae:

[ \Phi{ij} \approx -\frac{Fi(\pm\delta xj) - Fi(0)}{\delta x_j} ]

where (Fi(\pm\delta xj)) represents the force on atom (i) when atom (j) is displaced by (\pm\delta x_j) from its equilibrium position.

For reliable results, displacement magnitudes must be carefully chosen—typically between 0.01-0.05 Å—to balance numerical accuracy with the harmonic approximation's validity [8] [7]. This approach requires 3N × 3N DFT calculations for full force constant matrix determination, making it computationally demanding for large systems but conceptually straightforward and easily parallelizable.

Advanced Force Constant Extraction Methods

Recent methodological advances have addressed the computational limitations of conventional finite-displacement approaches:

Compressive Sensing Lattice Dynamics (CSLD): This technique leverages the inherent sparsity of real-space force constants (their rapid decay with increasing interatomic distance) to reconstruct the complete force constant matrix from a reduced set of random atomic displacements [6]. By applying ℓ₁ regularization, CSLD identifies the most significant force constants while minimizing overfitting, substantially reducing the number of required supercell calculations.

Minimal Molecular Displacement (MMD): Specifically designed for molecular crystals, the MMD approach utilizes a natural basis of molecular coordinates (rigid-body displacements and intramolecular vibrations) rather than individual atomic displacements [7]. This method reduces computational cost by 4-10× while maintaining accuracy, particularly for the critical low-frequency region where imaginary modes typically appear.

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs): MLPs like MACE-MP-0 and fine-tuned variants train on DFT force-displacement data to predict forces for new configurations [8] [9]. Once trained, these models can generate force constants at a fraction of the computational cost of direct DFT calculations, enabling high-throughput phonon screening across diverse materials systems.

Table 2: Comparison of Force Constant Calculation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Computational Cost | Accuracy Considerations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finite-Displacement | Direct numerical differentiation of forces | High (3N×3N calculations) | Sensitive to displacement size; exact within harmonic approximation | Small to medium systems; benchmark calculations |

| Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) | Analytical linear response to atomic displacements | Medium (calculation for each q-point) | Highly accurate; includes long-range electrostatics | Phonon dispersions; infrared/Raman intensities |

| Compressive Sensing Lattice Dynamics (CSLD) | Sparse recovery from random displacements | Reduced vs finite-displacement | Effective for sparse IFCs; may miss small couplings | Complex crystals with many atoms; high-order anharmonicity |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Trained interatomic potentials | Very low after training | Depends on training data quality and diversity | High-throughput screening; large systems |

Workflow: Force Constants to Phonon Stability Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete computational workflow from atomic structure to phonon stability assessment, highlighting the central role of force constant calculations:

Diagram 1: Workflow for phonon stability analysis via force constants. The central path shows the finite-displacement method, while dashed lines indicate alternative approaches like DFPT and machine learning potentials.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Force Constant Analysis

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Force Constant and Phonon Calculations

| Tool Name | Type | Key Functionality | Force Constant Calculation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pheasy | Python package | High-order IFC extraction & phonon properties | CSLD, regression on force-displacement data [6] |

| Phonopy | Fortran/Python code | Phonon analysis from supercell forces | Finite-displacement method [6] |

| Alamode | C++ package | Anharmonic lattice dynamics | CSLD, compressive sensing techniques [6] |

| hiPhive | Python library | High-order force constants | Structure mapper, machine learning approaches [6] |

| AMS | Software suite | Phonons with multiple engines | Finite-displacement, DFPT with ADF, BAND engines [10] |

| MACE-MP-MOF0 | ML Potential | Phonons in metal-organic frameworks | Fine-tuned on DFT forces; predicts full phonon DOS [9] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT suite | Ab initio calculations | DFPT, finite-displacement via phonon codes [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Force Constant Determination

Finite-Displacement Method with DFT

Objective: Calculate the complete second-order force constant matrix using systematic atomic displacements and DFT force calculations.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- DFT software (Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, or AMS)

- Phonon analysis tool (Phonopy, Pheasy, or Alamode)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: Fully optimize the atomic structure until maximum forces are below 1 meV/Å and stresses are minimized [9].

- Supercell Construction: Build a supercell large enough to capture relevant interatomic interactions (typically 2×2×2 or 3×3×3 conventional cells).

- Atomic Displacements: Generate structures with individual atoms displaced by ±0.01-0.015 Å in Cartesian directions [8].

- Force Calculations: Perform DFT calculations on each displaced structure to obtain the atomic forces.

- Force Constant Extraction: Compute matrix elements using central difference formula: (\Phi{ij} = -\frac{Fi(+\deltaj) - Fi(-\deltaj)}{2\deltaj}).

- Symmetrization: Apply crystal symmetry operations to force constants to ensure they satisfy translational and rotational invariance [6].

- Dynamical Matrix Construction: Build the mass-reduced dynamical matrix for wavevectors throughout the Brillouin zone.

- Phonon Calculation: Diagonalize the dynamical matrix to obtain phonon frequencies and eigenvectors.

Validation:

- Check acoustic sum rules (acoustic modes at Γ-point should be zero)

- Verify stability criteria (no imaginary modes for known stable structures)

- Compare with experimental spectroscopic data where available

Machine Learning Potential Training for Force Constants

Objective: Train a machine learning interatomic potential to predict forces and derive force constants for high-throughput phonon calculations.

Materials:

- Reference DFT database (energy, forces, stresses for diverse configurations)

- MLP architecture (MACE, NequIP, or other graph neural network)

- Training framework (JAX, PyTorch, or TensorFlow)

Procedure:

- Dataset Curation: Collect diverse atomic configurations including:

- Model Training: Optimize MLP parameters to minimize loss function: (L = wE \cdot \text{MSE}(E) + wF \cdot \text{MSE}(F) + w_V \cdot \text{MSE}(V))

- Model Validation: Assess force errors on held-out test configurations (target: <50 meV/Å RMSE).

- Force Constant Calculation: Use trained MLP to compute forces for finite displacements or implement analytical second derivatives if supported by architecture.

- Phonon Property Prediction: Calculate phonon band structure, density of states, and thermal properties.

Quality Control:

- Test on known stable and unstable structures to verify imaginary mode detection

- Validate against full DFT phonon calculations for representative systems

- Assess transferability to unseen structural motifs [8]

Applications in Imaginary Phonon Mode Research

Detecting Structural Instabilities

The primary application of force constants in imaginary phonon mode research lies in detecting structural instabilities in crystalline materials. When diagonalization of the dynamical matrix yields imaginary frequencies, this indicates that the current structure is not a true minimum on the PES. The pattern and magnitude of these imaginary modes provide crucial insights:

- Global Instabilities: Widespread imaginary modes throughout the Brillouin zone suggest a completely different crystal structure may be stable.

- Soft Modes: Imaginary modes at specific wavevectors indicate predisposition to charge density waves, magnetic ordering, or other broken-symmetry states.

- Temperature Effects: The quasi-harmonic approximation can reveal temperature-dependent stabilization where imaginary modes disappear at operational temperatures [6].

Materials Design and Screening

Force constant calculations enable high-throughput screening for dynamical stability in materials discovery. For example:

- Metal-Organic Frameworks: The MACE-MP-MOF0 potential has been fine-tuned specifically for phonon calculations in MOFs, correctly predicting imaginary modes that indicate structural collapse in overly strained frameworks [9].

- Polymorph Stability: Computational phonon analysis can predict the relative stability of different polymorphs, crucial for pharmaceutical development where metastable forms can have significantly different bioavailability.

- Anharmonic Materials: For strongly anharmonic systems, the standard harmonic approximation may falsely predict imaginary modes, requiring more advanced treatments like the self-consistent harmonic approximation or temperature-dependent effective potential methods [6].

Force constants as second derivatives of the potential energy surface provide the fundamental connection between atomic structure and vibrational dynamics in materials. Their accurate calculation enables reliable detection of imaginary phonon modes that signal structural instabilities—a critical capability for materials design and drug development. While finite-displacement methods remain important for benchmark calculations, emerging approaches like compressive sensing lattice dynamics and machine learning potentials are dramatically accelerating force constant computation, enabling high-throughput stability screening across diverse materials classes.

As computational methodologies continue advancing, the integration of experimental data through fused learning approaches [11] and the development of specialized potentials for complex materials like MOFs [9] will further enhance the accuracy and scope of force constant applications. These developments will solidify the role of force constant analysis as an indispensable tool for predicting material stability and properties across scientific disciplines.

The study of atomic vibrations in solids forms a cornerstone of modern condensed matter physics, enabling the understanding and prediction of a vast array of physical phenomena including thermal transport, phase transitions, and superconductivity [6]. At the heart of this understanding lies the harmonic approximation, a foundational model that provides the mathematical framework for describing how atoms oscillate in materials. This approximation, despite its simplifying assumptions, offers remarkable predictive power for numerous material properties and serves as the essential starting point for more sophisticated treatments of lattice dynamics.

Within the context of advanced research on imaginary phonon modes, the harmonic approximation and its central component—the dynamical matrix—take on particular significance. Imaginary phonon frequencies, which manifest as negative eigenvalues when solving the dynamical matrix, directly indicate dynamical instabilities in crystal structures [12]. These instabilities often foreshadow structural phase transitions or reveal materials that cannot persist in their current configuration. The force constants, which populate the dynamical matrix, thus serve as the critical link between a material's atomic structure and its vibrational stability. This primer explores the mathematical foundation of the harmonic approximation, details the construction and diagonalization of the dynamical matrix, and examines its profound implications for understanding lattice dynamics, with special emphasis on its role in identifying vibrational instabilities through imaginary modes.

Fundamental Theory of Atomic Vibrations

The Potential Energy Surface and Harmonic Expansion

In quantum mechanics, atoms in molecules and solids never cease vibrating, even at absolute zero temperature [3]. These vibrational behaviors evolve with internal structure, environmental factors, and external stimuli, forming the foundation of structure-dynamics-property relationships in materials science [3]. To quantitatively describe these atomic vibrations, we begin with the potential energy surface (PES) of an atomistic system.

The potential energy (V) can be expressed as a Taylor expansion with respect to atomic displacements [3]:

Where:

- V₀ represents the potential energy at equilibrium

- x_iα denotes the displacement of atom i in Cartesian direction α

- The first derivatives (∂V/∂x_iα) correspond to the negative of the interatomic forces

- The second derivatives (∂²V/∂xiα∂xjβ) represent the force constants

Within the harmonic approximation, this expansion is truncated after the second-order term, effectively assuming the potential energy profile takes a parabolic shape near the equilibrium configuration [3]. This simplification neglects higher-order anharmonic terms but provides an mathematically tractable model that successfully describes many essential aspects of vibrational behavior.

From Newton's Laws to the Dynamical Matrix

Applying Newton's second law to each atom in the system leads to the equations of motion that describe vibrational dynamics. For a crystalline solid, we consider the displacement of atom a in unit cell k as [3]:

Where:

- U_a is the polarization vector of atom a

- k is the wavevector in the reciprocal space

- r_ak is the position vector of atom a in unit cell k

- ω represents the angular frequency

The equations of motion collectively yield the eigenvalue equation [3]:

Where D(k) is the dynamical matrix at wavevector k. This matrix represents the Fourier transform of the force constant matrix and contains all information about how atoms interact through the crystal lattice.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components of the Harmonic Approximation

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy Expansion | V = V₀ + ½∑Φijuiuj |

Parabolic approximation of interatomic interactions |

| Force Constants | Φij = ∂²V/∂ui∂uj |

Measure of interaction strength between displaced atoms |

| Dynamical Matrix | Dαβ(aa',k) = (1/√(m_am_a'))∑Φαβ(0a,ka')exp[-ik·(r_ka'-r_0a)] |

Fourier transform of force constants governing vibration patterns |

| Eigenvalue Equation | ω²U = D(k)U |

Master equation determining vibrational frequencies and patterns |

The Dynamical Matrix: Construction and Diagonalization

Mathematical Formulation

The dynamical matrix D(k) is a 3N×3N matrix for a crystal with N atoms per unit cell. Its elements are constructed from the force constants and exhibit specific symmetry properties that reflect the crystal structure. For the interaction between atoms a and a', the dynamical matrix elements are given by [3]:

Where:

- ma and ma' are the masses of atoms a and a'

- Φ_αβ(0a,k'a') are the force constants between atom a in the home unit cell and atom a' in unit cell k'

- r0a and rk'a' are position vectors

- The sum is over all unit cells k' in the crystal

This formulation satisfies the translational invariance of the crystal, requiring that the force on any atom remains unchanged when all atoms are displaced equally.

Diagonalization and Physical Interpretation

Diagonalization of the dynamical matrix for each wavevector k yields eigenvalues ω²(k) and eigenvectors ε(k), where:

- The eigenvalues ω_j²(k) correspond to the squared frequencies of the normal modes

- The eigenvectors ε_j(k) describe the polarization and relative phase of atomic displacements for each mode

The index j runs from 1 to 3N, representing the different vibrational branches: three acoustic branches (where frequency approaches zero as k→0) and 3N-3 optical branches.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Force Constants and Dynamical Matrix

| Method | Fundamental Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finite-Displacement (Frozen Phonon) | Numerical differentiation of forces in systematically displaced supercells [6] | Straightforward implementation; Systematic extension to higher orders [6] | Combinatorial explosion of configurations for high-order terms [6] |

| Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) | Analytical calculation of derivatives using linear response theory [6] | Direct calculation in reciprocal space; No supercell required [6] | Implementation complexity; Pseudopotential dependence [6] |

| Compressive Sensing Lattice Dynamics | Linear regression with sparsity constraints on force constants [6] [12] | Efficient extraction of high-order terms; Minimal training configurations [6] [12] | Challenging for long-range interactions in infrared-active solids [6] |

Figure 1: Workflow from atomic structure to phonon properties, highlighting the central role of the dynamical matrix in determining vibrational stability.

Imaginary Phonon Modes and Dynamical Instability

Physical Interpretation of Imaginary Frequencies

When the diagonalization of the dynamical matrix yields negative eigenvalues (ω² < 0), the corresponding phonon frequencies become imaginary quantities (ω = i|ω|). Physically, this indicates that the assumed crystal structure does not represent a stable minimum on the potential energy surface but rather a saddle point or maximum [12]. Rather than oscillating around their equilibrium positions, atoms experience forces that drive them toward new, more stable configurations.

In research focused on force constants and imaginary phonon modes, these imaginary frequencies serve as crucial indicators of several phenomena:

- Structural phase transitions where the crystal transforms to a different symmetry at lower temperatures

- Dynamical instability preventing certain crystal structures from persisting at specific conditions

- Metastable materials that may be stabilized by anharmonic effects or external factors

Computational Detection and Analysis

The high-throughput framework for lattice dynamics incorporates specific protocols for handling imaginary modes [12]. When harmonic calculations reveal imaginary frequencies, the workflow performs phonon renormalization to obtain real effective phonon spectra at finite temperatures. This process involves calculating anharmonic corrections to the force constants, which often eliminate the imaginary frequencies that appear in the purely harmonic treatment [12].

The standard procedure involves:

- Identification of wavevectors with imaginary frequencies in the Brillouin zone

- Analysis of the corresponding eigenvectors to understand the atomic displacement pattern

- Renormalization using anharmonic IFCs to obtain temperature-dependent effective phonons

- Free energy calculation comparing the stable and unstable structures to determine phase stability

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

High-Throughput Workflow for Lattice Dynamics

Modern computational approaches have developed automated frameworks for calculating lattice dynamical properties from first principles [12]. The comprehensive workflow involves multiple steps:

Step 1: Structure Optimization and Force Calculations

- Stringent structure optimization of the initial primitive cell using density functional theory (DFT)

- Self-consistent field (SCF) force calculations in systematically displaced supercells

- Recommended DFT parameters: PBEsol functional (superior to PBE for lattice parameters), projector-augmented wave pseudopotentials [12]

Step 2: Force Constants Fitting

- Extraction of harmonic and anharmonic force constants using advanced fitting algorithms

- Package recommendations: HiPhive (Python-integratable with flexible fitting methods) [12]

- Optimal supercell size: ~20 Å for convergence [12]

Step 3: Phonon Renormalization (if unstable)

- Calculation of effective phonons at finite temperatures for dynamically unstable compounds

- Obtaining real phonon spectra through anharmonic corrections [12]

Step 4: Thermal Property Calculation

- Lattice thermal conductivity from Boltzmann transport equation (ShengBTE or Phono3py)

- Vibrational free energy and entropy calculations [12]

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Lattice Dynamics Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Constants Extraction | ALAMODE [12], hiPhive [12], CSLD [6], Pheasy [6] | Extract IFCs from force-displacement data | Building lattice dynamical models from DFT calculations |

| Phonon Property Calculators | Phonopy [12], Phono3py [12], ShengBTE [12] | Calculate phonon dispersion, DOS, thermal conductivity | Harmonic and anharmonic lattice dynamics |

| Ab Initio Packages | VASP [12], Quantum ESPRESSO [6], Abinit [6] | Perform DFT calculations for forces and energies | Generating training data for force constants |

| Workflow Managers | atomate [12], Fireworks [12] | Automate job submission and coordination | High-throughput lattice dynamics screening |

| Structure Handling | pymatgen [12], ASE [12] | Crystal structure manipulation and analysis | Structure generation and transformation |

Figure 2: Computational workflow for calculating phonon properties from first principles, showing the pathway from quantum mechanical calculations to macroscopic thermal properties.

Advanced Considerations and Applications

Machine Learning Accelerated Approaches

Recent advances have incorporated machine learning to dramatically accelerate lattice dynamics calculations [3] [13]. Graph neural networks, such as the Crystal Attention Graph Neural Network (CATGNN), can predict spectral properties like phonon density of states with several orders of magnitude reduction in computational cost compared to full DFT calculations [13]. These approaches are particularly valuable for high-throughput screening of materials for specific thermal properties.

In the context of force constants and imaginary modes, machine learning potentials (MLPs) face specific challenges. As noted in research on sodium superionic conductors, "universal machine learning potentials cannot be straightforwardly deployed for quickly screening fast ionic transport materials" because "the majority of the training data used for training such MLPs are near equilibrium, while ion migration in superionic conductors usually involves out-of-equilibrium movement" [14]. This limitation highlights the continued importance of understanding the fundamental harmonic approximation and its extensions.

Connection to Macroscopic Thermal Properties

The harmonic approximation, despite its limitations, provides access to several important macroscopic thermal properties through analytical expressions. The vibrational free energy (Fvib), entropy (Svib), and constant-volume heat capacity (C_v) can be derived directly from the phonon densities of states [3]:

Where g(ω) is the phonon density of states obtained from the dynamical matrix solutions across the Brillouin zone.

Beyond Harmonicity: Anharmonic Corrections

While the harmonic approximation provides the essential foundation, many important phenomena require consideration of anharmonic effects. Thermal expansion, finite thermal conductivity, and temperature-induced phase transitions all originate from anharmonicity [3] [12]. The theoretical framework extends the potential energy expansion to include third- and fourth-order force constants:

Where:

- Ψ_ijk represent the third-order force constants governing phonon-phonon scattering

- χ_ijkl represent the fourth-order force constants contributing to temperature-dependent frequency shifts

In the context of imaginary mode research, anharmonic corrections often eliminate instabilities that appear in harmonic calculations, revealing that some materials which appear harmonically unstable can actually be stabilized at finite temperatures through anharmonic effects [12].

The harmonic approximation, with the dynamical matrix as its centerpiece, provides an indispensable foundation for understanding lattice dynamics in materials. Through its mathematical formalism, researchers can connect fundamental atomic interactions—encoded in force constants—to experimentally observable vibrational phenomena. The identification and analysis of imaginary phonon modes represents one of the most critical applications of this framework, enabling the prediction of structural instabilities and phase transitions.

While modern computational materials science has developed sophisticated high-throughput workflows and machine-learning-accelerated approaches, these advanced methods remain rooted in the harmonic approximation as their conceptual starting point. The continued research into force constants and their manifestation in the dynamical matrix ensures that this classic framework will remain essential for designing and discovering materials with tailored thermal and vibrational properties. As lattice dynamics research expands to encompass increasingly complex materials systems and extreme conditions, the harmonic approximation will continue to provide the fundamental language for describing how atoms move collectively in condensed matter.

In the study of lattice dynamics, the harmonic approximation has long served as the foundational model, treating atomic vibrations as simple, independent harmonic oscillators. This framework successfully predicts vibrational spectra for many systems but fails dramatically when nuclear quantum effects and strong interatomic anharmonicity become significant. Such failures are starkly evidenced by the appearance of imaginary phonon modes in harmonic calculations—modes with negative frequencies that indicate a dynamical instability and a spontaneous lowering of the crystal's potential energy through lattice distortion [15]. This whitepaper examines how moving beyond the harmonic paradigm to include anharmonic effects is not merely a refinement but a fundamental necessity for accurately predicting the stability, spectroscopic signatures, and functional properties of a wide range of materials, from complex organic molecules to high-temperature superconductors.

The core of the issue lies in the nature of the interatomic potential. The harmonic approximation assumes a parabolic potential well, where force constants are independent of atomic displacements. In reality, potentials are anharmonic, leading to phonon-phonon interactions, temperature-dependent frequencies, and finite phonon lifetimes. When the curvature of the true potential energy surface differs significantly from the harmonic estimate, particularly for low-frequency soft modes, the harmonic solution becomes unstable. Anharmonicity renormalizes these modes, often stabilizing what harmonic calculations label as imaginary and providing a correct physical description of the lattice dynamics [16] [17] [18].

Theoretical Foundations: From Harmonic Instability to Anharmonic Stabilization

The Origin of Imaginary Modes

Within the harmonic approximation, the phonon eigenfrequencies ( \omega ) are determined by solving the secular equation derived from the dynamical matrix, which is built from the second-order interatomic force constants. When the harmonic potential surface exhibits a curvature that is not positive definite for all vibrational modes, the solution for some modes yields ( \omega^2 < 0 ), resulting in an imaginary frequency [15]. This imaginary frequency is a mathematical artifact of the harmonic approximation, signaling that the high-symmetry structure is not a minimum on the true anharmonic potential energy surface. The system can lower its energy by distorting along the coordinates of the imaginary modes, a phenomenon linked to electronic instabilities, such as those originating from flat bands near the Fermi level [15].

The Anharmonic Stabilization Mechanism

Anharmonicity stabilizes these soft modes by coupling different vibrational degrees of freedom. The critical theoretical advance is to replace the static harmonic potential with a effective potential that incorporates the quantum and thermal fluctuations of the atoms. This is the essence of the Stochastic Self-Consistent Harmonic Approximation (SSCHA). The SSCHA employs a variational principle to find an auxiliary harmonic potential that best approximates the free energy of the true anharmonic system [16] [17]. In this framework, the force constants are not calculated at the static lattice positions but are self-consistently averaged over a distribution of atomic displacements caused by anharmonic vibrations.

This process can be understood as a "dressing" of the phonons by anharmonic interactions. The result is a new set of renormalized phonon frequencies where the original imaginary modes are shifted to positive, real values, reflecting the true dynamic state of the system, which may be dynamically stable despite the harmonic prediction [17] [18]. The transition from harmonic instability to anharmonic stability can be conceptualized as a phonon pseudo-Jahn–Teller lattice instability, where the anharmonic interactions lift the degeneracy of vibrational modes [18].

Table: Fundamental Concepts in Mode Stability

| Concept | Harmonic Picture | Anharmonic Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy Surface | Parabolic | Curved, with quartic and higher-order terms |

| Force Constants | Constant, independent of atomic displacement | Renormalized by thermal and quantum fluctuations |

| Soft Mode Frequency | Imaginary (( \omega^2 < 0 )), signaling instability | Real and positive, stabilized by mode coupling |

| Physical Interpretation | Structure is dynamically unstable | Structure is dynamically stable at finite temperature |

Theoretical Workflow for Stability Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from identifying a harmonic instability to achieving an anharmonic stabilization, integrating the key theoretical concepts and computational methods.

Computational Methodologies for Capturing Anharmonicity

The Stochastic Self-Consistent Harmonic Approximation (SSCHA)

The SSCHA is a variational method that minimizes the free energy of the system with respect to the parameters of an auxiliary harmonic trial density matrix. The workflow involves [17]:

- Initialization: Starting from a harmonic phonon calculation to generate an initial ensemble of atomic configurations.

- Stochastic Sampling: Generating a population of supercell configurations where atoms are displaced according to a trial phonon distribution.

- Force Calculation: Computing the energy and quantum-mechanical forces for each configuration in the ensemble. To make this computationally feasible for large systems, Machine-Learning Force Fields (MLFFs)—such as ANI-1ccx, ANI-2x, or Moment Tensor Potentials (MTP)—trained on high-level ab initio data are employed [16] [17].

- Updating: The trial phonon parameters (centroid positions and force constants) are updated to minimize the free energy.

- Self-Consistency: Steps 2-4 are repeated until convergence is achieved, yielding the anharmonically renormalized phonon frequencies.

Time-Dependent Extensions and Spectral Properties

While the static SSCHA provides renormalized phonon frequencies, it does not capture phonon lifetime broadening or the appearance of combinational modes. The time-dependent SSCHA (tdSSCHA) extends the formalism to simulate the quantum dynamics of the nuclei, allowing for the calculation of the spectral function [16]. This linear response technique can reveal the natural lifetime broadening of peaks due to anharmonic scattering and the emergence of overtone and combination bands, providing a far richer and more accurate description of the vibrational spectrum compared to the static approximation.

Practical Workflow for Anharmonic Phonon Calculations

The following diagram details the sequential steps involved in a typical anharmonic phonon calculation, highlighting the integration of machine-learning force fields and the progressive increase in computational cost and physical accuracy.

Table: Comparison of Computational Methods for Vibrational Spectra

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Phonon Lifetimes | Overtone/Combinational Modes | Computational Cost | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic | Second-order force constants at equilibrium geometry | Infinite | No | Low | Initial screening, high-symmetry stable crystals |

| Static SSCHA | Free-energy minimization with an auxiliary harmonic potential | Infinite | No | Medium | Temperature-dependent frequency shifts, stabilizing soft modes |

| Dynamic SSCHA (tdSSCHA) | Linear response theory on anharmonic free energy surface | Finite (broadening) | Yes | High | Accurate spectral line shapes, lifetime analysis, complex spectra |

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Complex Organic Molecules and Vibrational Spectroscopy

For complex organic molecules like nucleic acids (adenine, cytosine, guanine, etc.), symmetry is low and vibrational spectra are dense and challenging to interpret. The FAbulA method, which combines tdSSCHA with MLFFs, has demonstrated remarkable success in predicting and assigning peaks in Raman and IR spectra [16]. For instance, in cytosine, the method correctly identifies the positions and relative intensities of most active vibrational modes. The quantitative agreement with experiment validates the anharmonic treatment, as a simple harmonic calculation would fail to capture the correct spectral features without empirical scaling [16].

Superconducting Hydrides and Carbides

Anharmonicity plays a critical role in the properties of high-Tc superconducting hydrides and carbides.

- In LaBeH8, a superconducting hydride, quantum ionic and anharmonic effects significantly soften high-frequency phonon modes. This softening enhances the electron-phonon coupling, which is crucial for superconductivity. Accurate prediction of Tc requires an anharmonic treatment beyond the harmonic approximation [17].

- Y₂C₃ provides a striking example where the high-symmetry phase exhibits imaginary zone-center optical phonon modes due to the wobbling motion of C dimers and an electronic instability. Upon lattice distortion to a lower-symmetry structure, these imaginary modes stabilize into low-energy phonons that carry a strong electron-phonon coupling, giving rise to the observed superconductivity with Tc up to 18 K [15]. This case demonstrates that discarding compounds with harmonic imaginary modes can lead to overlooking promising superconducting candidates.

Pre-Martensitic Transitions and Phonon Domains

In shape-memory alloys like Ni-Mn-Ga, the parent austenite phase exhibits "pre-martensitic" phenomena, such as tweed patterns and diffuse scattering in diffraction, long before the martensitic transition occurs. A Grüneisen-type phonon theory explains this as a phonon spinodal decomposition into elastic-phonon domains [18]. The incomplete softening of a low-energy phonon branch, combined with strong phonon-strain coupling, leads to a lattice instability and the formation of domains characterized by broken dynamic symmetry. This transition is a direct consequence of anharmonicity and provides a unified explanation for a range of precursor anomalies that defy harmonic models [18].

Table: Quantitative Impact of Anharmonicity in Different Material Classes

| Material System | Observable | Harmonic Prediction | Anharmonic Prediction | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acids (e.g., Cytosine) | Raman/IR peak positions (cm⁻¹) | Requires empirical scaling | Within ~1% of experiment, correct relative intensities [16] | Experimental Raman/IR spectra [16] |

| LaBeH8 (80 GPa) | Tc (Superconducting critical temperature) | Underestimates or overestimates Tc | Corrects Tc towards experimental value (~110 K) [17] | Synthesis & measurement at 80 GPa [17] |

| Y₂C₃ | Dynamical Stability | Unstable (Imaginary modes) | Stable (after distortion), Tc ~18 K [15] | Synthesis at 4.0-5.5 GPa, Tc measurement [15] |

| CrFeCoNiCu HEA | Lattice Thermal Conductivity (κL) | Overestimated | Strongly suppressed, agrees with low experimental values [19] | -- |

Table: Key Computational and Modeling Tools for Anharmonicity Research

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANI-1ccx / ANI-2x | Machine-Learning Force Field (MLFF) | Provides near-ab initio accuracy forces for energy landscapes of organic molecules [16]. | Anharmonic vibrational spectra of drugs, proteins [16]. |

| Moment Tensor Potentials (MTP) | Machine-Learning Force Field (MLFF) | Describes interatomic interactions in materials; adaptable via active learning [17]. | SSCHA calculations for superconducting hydrides [17]. |

| Stochastic Self-Consistent Harmonic Approximation (SSCHA) | Computational Method | Performs variational anharmonic free energy minimization [16] [17]. | Stabilizing imaginary modes, obtaining temperature-dependent frequencies. |

| Time-Dependent SSCHA (tdSSCHA) | Computational Method | Calculates dynamical anharmonic spectral function [16]. | Predicting broadband IR/Raman spectra with overtone bands. |

| Bond Capacitor Model | Analytical Model | Computes Raman tensor and IR intensities for large molecules at low cost [16]. | Predicting peak activities in vibrational spectra of organic molecules [16]. |

The journey "Beyond Harmony" reveals that anharmonicity is not a minor perturbation but a central player in determining the structural stability and vibrational properties of materials. The presence of imaginary phonon modes in a harmonic calculation is not a dead end but a signpost pointing toward rich physics that can only be uncovered by embracing the anharmonic nature of the interatomic potential. Methodologies like the SSCHA and tdSSCHA, supercharged by machine-learning force fields, have created a paradigm shift. They now enable the accurate and efficient prediction of properties ranging from the vibrational spectra of drug molecules to the superconducting transition temperatures of high-pressure hydrides. As these tools continue to evolve and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly unlock new frontiers in the design and discovery of advanced functional materials.

Calculating Force Constants: From Ab Initio Methods to AI-Driven Potentials

Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) for Direct IFC Calculation

Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) provides a powerful framework for efficiently computing the second-order derivatives of the total energy of a crystal with respect to atomic displacements, known as the interatomic force constants (IFCs). These IFCs form the fundamental building blocks for calculating phonon spectra and assessing lattice dynamical stability. Within the context of investigating imaginary phonon modes, DFPT offers a direct and computationally efficient pathway to the force constant matrix, which, upon diagonalization, reveals the phonon frequencies throughout the Brillouin zone. The central object in this formalism is the matrix of force constants, which is mathematically equivalent to the Hessian matrix of the potential energy surface, E [2]:

$$ D{i\alpha,i^{\prime}\alpha^{\prime}}(\mathbf{R}p,\mathbf{R}{p^{\prime}})=\frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial u{p\alpha i}\partial u_{p^{\prime}\alpha^{\prime}i^{\prime}}}, $$

where $u{p\alpha i}$ represents the displacement of atom $\alpha$ in the unit cell at $\mathbf{R}p$ along the Cartesian direction $i$. The eigenvalues of this Hessian matrix determine the curvature of the energy landscape. A positive eigenvalue indicates a positive curvature (a minimum in the potential energy surface), leading to a stable vibrational mode with a real, positive phonon frequency. Conversely, a negative eigenvalue signifies a negative curvature (a maximum). The corresponding phonon frequency, calculated as the square root of this eigenvalue, becomes an imaginary frequency (often denoted as a 'soft mode') [2]. This is a critical indicator in computational materials science, as the presence of such imaginary modes suggests that the crystal structure is dynamically unstable—it is at a saddle point on the energy landscape rather than a local minimum. Displacing the atoms along the direction of the eigenvector associated with the imaginary mode can guide the search for a lower-energy, stable structure [2].

DFPT Methodology and Workflow

Core Computational Workflow

The practical application of DFPT for calculating IFCs follows a structured workflow, which can be visualized in the diagram below. This process directly computes the dynamical matrix and its derivatives for efficient phonon property extraction.

Key DFPT Input Parameters

DFPT calculations, as implemented in codes like VASP, are controlled by specific input flags that dictate the method of computation. The table below summarizes the essential parameters for a standard DFPT phonon calculation.

Table 1: Essential input parameters for DFPT phonon calculations in VASP.

| Input Parameter | Recommended Setting | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

IBRION |

7 or 8 | Selects the DFPT method for phonon calculations. IBRION=8 uses symmetry to reduce the number of displacements [20]. |

LEPSILON |

.TRUE. |

Computes the ionic contribution to the dielectric tensor and Born effective charges [20]. |

EDIFF |

1E-6 to 1E-8 |

Tight convergence criterion for the electronic self-consistent loop to ensure accurate forces [21]. |

LPEAD |

.TRUE. (optional) |

Improves the accuracy of derivatives for the exchange-correlation functional in some cases [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Codes

A successful DFPT investigation relies on a suite of software tools and computational protocols. The following table details the key "research reagents" for this field.

Table 2: Essential software tools and computational protocols for DFPT and phonon analysis.

| Tool/Protocol | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | First-Principles Code | A widely used DFT code that implements DFPT (via IBRION=7/8) for direct force constant calculation [20]. |

| Phonopy | Post-Processing Code | An open-source package used for post-processing force constants to obtain phonon dispersion, density of states, and thermodynamic properties [22]. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | Advanced Modeling | Frameworks like GAP, MACE, NEP, and HIPHIVE can be trained on DFT data to enable high-order anharmonic calculations infeasible with pure DFPT [21]. |

| Structural Relaxation | Computational Protocol | A mandatory pre-step to bring the crystal to its equilibrium geometry with near-zero forces on atoms, ensuring the system is at a minimum before phonon analysis [23]. |

Analysis of Imaginary Phonon Modes

Interpretation and Significance

The primary output of a DFPT phonon calculation is a set of phonon frequencies and their corresponding eigenvectors. The distinction between stable and unstable modes is fundamental [2]:

- Stable Mode (

f): A positive eigenvalue of the force constant matrix, indicating a real, positive phonon frequency. The structure is at a minimum in the energy surface along this vibrational direction. - Imaginary/Soft Mode (

f/i): A negative eigenvalue of the force constant matrix, resulting in an imaginary phonon frequency. This signifies that the structure is at a maximum along this vibrational direction and is dynamically unstable. The eigenvector of this soft mode indicates the specific atomic displacement pattern that will drive the system toward a lower-symmetry, stable structure.

It is crucial to note that the harmonic approximation inherent in standard DFPT calculations implies that the presence of an imaginary frequency is a direct indicator of dynamical instability at 0 K [2]. The role of temperature and anharmonicity can be complex. In some cases, finite temperature can stabilize a structure that appears unstable in harmonic calculations, but capturing this effect requires going beyond the harmonic approximation and explicitly including anharmonic terms (phonon-phonon interactions) [2] [21].

Protocol for Resolving Instabilities

When imaginary modes are detected, a systematic protocol should be followed to identify and resolve the structural instability.

Critical Considerations and Advanced Treatments

- Supercell Convergence: While DFPT efficiently calculates the dynamical matrix at specific q-points, obtaining a full phonon dispersion or ensuring force constants decay properly requires computing IFCs in a sufficiently large supercell or using Fourier interpolation [20] [23]. Inadequate sampling can lead to unphysical long-range interactions.

- Anharmonicity and High-Order IFCs: For a complete picture of stability, especially near phase transitions or at high temperatures, third- and fourth-order IFCs are critical. These high-order anharmonic processes govern phonon-phonon scattering and can renormalize phonon frequencies [21]. However, their calculation with DFPT is computationally prohibitive for most systems. Here, machine learning force fields (MLFFs) trained on DFT/DFPT data offer a powerful and scalable alternative to access these high-order interactions [21].

- Functional Dependence: The choice of the exchange-correlation functional in DFT can significantly impact the calculated phonon frequencies. Instabilities predicted with one functional (e.g., GGA-PBE) may not appear with another (e.g., LDA or hybrid functionals). It is good practice to verify key results with different functionals where feasible.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

The landscape of first-principles phonon calculations is primarily dominated by two approaches: DFPT and the finite-displacement (frozen-phonon) method. The table below provides a detailed comparison of these methodologies.

Table 3: Comparative analysis of DFPT and the finite-displacement method for phonon calculations.

| Feature | Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) | Finite-Displacement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Computes derivatives of the wavefunctions and electron density analytically via linear response [20]. | Uses finite differences by explicitly displacing atoms and calculating forces via the Hellmann-Feynman theorem [23]. |

| Computational Cost | Generally more efficient for dense q-point sampling and large primitive cells, as it avoids large supercells for q=0 [20]. | Requires a supercell larger than the interaction range of the IFCs, leading to many independent calculations (scales with 3N-3 atoms) [23]. |

| Key Inputs (VASP) | IBRION = 7 or 8 [20]. |

IBRION = 5 or 6 (phonon using finite differences). |

| Precision | Avoids numerical errors associated with choosing a displacement magnitude (POTIM) [20]. |

Accuracy depends on the carefully chosen displacement magnitude (POTIM); too small or too large can introduce errors [20] [23]. |

| Implementation & Limitations | Implementation in codes like VASP is sometimes considered rudimentary; limited to LDA and GGA functionals in some cases [20]. | More universally applicable and can be used with any DFT functional. Requires careful supercell construction to avoid interactions between periodic images [23]. |

| Best Use Cases | - Quick assessment of zone-center (Γ-point) phonons.- Systems with long-range forces.- Dielectric properties and Born effective charges [20]. | - Robust, easy-to-use method for any functional.- Necessary when DFPT implementation is unavailable or limited for the desired property. |

The finite-displacement method (FDM), also known as the frozen phonon approach, is a cornerstone technique in computational materials science for calculating phonon spectra and force constants in solid-state systems [24] [25]. Within the context of research on force constants and their role in generating imaginary phonon modes, this method provides the fundamental data connecting atomic structure to dynamical properties. Imaginary phonon modes (negative frequencies in calculated spectra) indicate dynamical instabilities in the crystal structure, often stemming from inaccuracies in calculated force constants or genuine structural instabilities. The finite-displacement method operates by systematically displacing atoms from their equilibrium positions and using density functional theory (DFT) calculations to determine the resulting forces, from which the interatomic force constants and subsequent phonon properties are derived [24].

The supercell approximation is intrinsically linked to this approach, as it imposes periodic boundary conditions on defect-containing systems or allows for the calculation of phonons at arbitrary wavevectors beyond the primitive cell limitations [26]. This guide details the practical workflow for implementing the finite-displacement method, with specialized strategies for supercell construction to ensure accurate and efficient determination of force constants and phonon properties, with particular attention to diagnosing and understanding imaginary phonon modes.

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Principles

The finite-displacement method is built upon the harmonic approximation, where the potential energy of the crystal is expanded as a Taylor series around the equilibrium positions. The central quantity of interest is the force constant matrix, defined as:

[ \Phi{i\alpha, j\beta} = - \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial u{i\alpha} \partial u{j\beta}} \approx \frac{F{i\alpha}(\Delta u{j\beta}) - F{i\alpha}(0)}{\Delta u_{j\beta}} ]

where ( E ) is the total energy of the crystal, ( u{i\alpha} ) is the displacement of atom ( i ) in the Cartesian direction ( \alpha ), and ( F{i\alpha} ) is the corresponding force component [25]. In practice, this partial derivative is approximated through finite differences by applying small atomic displacements and calculating the resulting changes in forces.

The force constants are directly used to construct the dynamical matrix, whose eigenvalues yield the squared phonon frequencies. The appearance of imaginary phonon modes (negative squared frequencies) in this framework can originate from several sources: (1) genuine structural instabilities where the crystal would transform to a lower-energy structure, (2) insufficient supercell size leading to unphysical long-range interaction truncation, or (3) numerical inaccuracies in the force calculations, often due to inadequate DFT parameters [24].

Comparison with Density Functional Perturbation Theory

The finite-displacement method provides an alternative approach to density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) for phonon calculations. While DFPT computes force constants by solving for the linear response of electrons to atomic displacements within perturbation theory, the finite-displacement method uses direct force calculations in real space [24]. Key comparative aspects include:

- Implementation: FDM relies on multiple DFT force calculations with atomic displacements, while DFPT solves the Sternheimer equation for the response of the electronic system.

- Supercell Requirements: FDM requires supercells large enough to capture the range of atomic interactions, particularly challenging for systems with long-range forces. DFPT can work with the primitive cell but requires dense q-point sampling.

- Computational Efficiency: For small systems and full phonon dispersions, DFPT is generally more efficient. FDM can be advantageous for complex systems with broken symmetry, such as defects or disordered alloys, where DFPT implementations may be limited [25].

Table 1: Finite-Displacement Method vs. Density Functional Perturbation Theory

| Aspect | Finite-Displacement Method | Density Functional Perturbation Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Real-space finite differences | Linear response in k-space |

| Supercell Size | Must be large enough to capture force constants | Primitive cell often sufficient |

| Defect Compatibility | Naturally handles broken symmetry | Implementation more challenging |

| Computational Scaling | Scales with number of displacements | More favorable for full dispersion |

| Implementation | Multiple DFT force calculations | Self-consistent response equations |

Computational Workflow

The complete finite-displacement method workflow encompasses structure preparation, displacement generation, force calculation, and post-processing, with careful attention to parameters that affect the accuracy of force constants and potential appearance of imaginary modes.

Diagram 1: Finite-Displacement Method Workflow

Supercell Construction Strategies

The construction of appropriate supercells is critical for accurate force constant determination and avoiding spurious imaginary modes. Several specialized approaches have been developed:

Conventional Supercells: Traditional supercells are created by replicating the primitive cell in integer multiples along lattice vectors. The size must be sufficient to capture the range of atomic interactions, with convergence testing essential [26].

Special Quasi-random Structures (SQS): For disordered alloys, SQS supercells are designed to mimic the most representative random distribution of atom types among disordered sites, capturing the relevant local environments while maintaining periodicity [25].

Non-Diagonal Supercells: For phonon calculations at specific q-points not commensurate with the primitive cell, non-diagonal supercells can be constructed that fold the desired q-point to the Γ-point, enabling calculation of those specific phonon modes [27].

Defect-Optimized Supercells: For point defect systems, the "one defect, one potential" strategy involves creating defect-specific machine learning interatomic potentials trained on a limited set of perturbed supercells, enabling accurate phonon calculations with reduced computational cost [28].

Table 2: Supercell Construction Approaches for Different Material Systems

| Material System | Recommended Approach | Key Considerations | Typical Size Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ordered Crystals | Conventional supercells | Convergence with size; symmetry | 64-512 atoms |

| Disordered Alloys | SQS supercells | Representative local environments | 50-200 atoms |

| Specific q-point Phonons | Non-diagonal supercells | Commensurability with target q-point | Variable |

| Point Defects | Defect-optimized supercells | Isolation of defect; local relaxation | 96-360 atoms |

| Surfaces/Interfaces | Layered supercells | Vacuum thickness; interface separation | System-dependent |

Displacement Generation and Force Calculation

The generation of atomic displacements and subsequent force calculations form the core of the finite-displacement method:

Displacement Patterns: For a supercell containing N atoms, phonon calculations using the finite-displacement method typically require 3N or 6N DFT calculations when using the single-displacement or double-displacement schemes, respectively [28]. Symmetry can significantly reduce this number by identifying equivalent atomic displacements.

Displacement Magnitude: The displacement amplitude represents a critical parameter balancing numerical accuracy and anharmonic effects. Typical values range from 0.01-0.04 Å [28]. Too small displacements exacerbate numerical noise in force calculations, while excessively large displacements introduce anharmonic effects that violate the harmonic approximation.

Force Calculation Precision: The accuracy of force constants depends directly on the precision of the calculated forces. Tight convergence criteria for electronic structure calculations (e.g., 1-10 meV/Å force convergence) are essential, particularly for detecting small imaginary modes that might indicate subtle instabilities [28].

Specialized Supercell Methodologies

Defect Phonons and the "One Defect, One Potential" Strategy

Recent advances in machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have enabled novel supercell strategies for defect phonon calculations. The "one defect, one potential" approach involves training a defect-specific MLIP on a limited set of perturbed supercells, yielding phonons with accuracy comparable to DFT regardless of supercell size [28].

The training data generation involves creating multiple supercell configurations where atoms are randomly displaced within a sphere of radius rmax = 0.04 Å centered at their equilibrium positions [28]. The MLIP, typically based on equivariant neural network potentials like NequIP or Allegro, then learns the potential energy surface, enabling rapid force evaluations for phonon calculations while maintaining DFT-level accuracy for properties such as Huang-Rhys factors and phonon dispersions.

This approach demonstrates particular value for large supercells (e.g., 104 atoms) where direct DFT calculations would be computationally prohibitive, reducing computational expenses by more than an order of magnitude while maintaining accuracy in predicting key phonon-assisted phenomena such as nonradiative carrier capture rates and photoluminescence spectra [28].

Efficient Approximation for Disordered Alloys

For disordered phases in alloy systems, researchers have developed efficient approximations to the supercell approach that maintain accuracy while reducing computational cost. These methods exploit the characteristics of recovery forces (the forces that restore displaced atoms to equilibrium), which exhibit well-defined statistical distributions [25].

The approximation involves focusing DFT calculations on perturbed configurations with unique local environments whose chemistry resembles that of the alloy, rather than calculating all possible displacement configurations. Studies have demonstrated that the harmonic approximation of the supercell approach shows limited sensitivity to the uncertainty of force inputs, particularly when the uncertainty is smaller than the force magnitude [25].

This efficient approximation has been successfully applied to calculate temperature-dependent thermodynamic properties and phase diagrams, such as for the Cr-Ni system, demonstrating predictions in good agreement with previous thermodynamic assessments while significantly reducing computational burden [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Finite-Displacement Phonon Calculations

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Interoperability |

|---|---|---|---|

| PH-NODE | Phonon node searching | DFPT and finite-displacement based; topological phonon analysis | WIEN2k, Elk, ABINIT |

| supercell | Supercell generation | Combinatorial structure generation; symmetry analysis; charge balancing | Stand-alone with structure file input |

| Yambo/YamboPy | Exciton and phonon-assisted optics | Finite-displacement luminescence; exciton-phonon coupling | Quantum ESPRESSO |

| Allegro/NequIP | Machine learning potentials | Equivariant interatomic potentials; high data efficiency | VASP, LAMMPS |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT calculations | Plane-wave pseudopotential method; phonon modules | Multiple third-party tools |

| VASP | DFT calculations | Projector augmented-wave method; force calculations | Multiple third-party tools |

Practical Implementation Protocol

Step-by-Step Workflow for Phonon Calculation

Initial Structure Preparation

- Begin with a fully relaxed primitive cell using high-precision DFT settings.

- Confirm convergence of key parameters (energy cutoff, k-point sampling, force thresholds).

Supercell Construction

- Select appropriate supercell size based on the interaction range in your system.

- For conventional crystals, use integer multiples of lattice vectors.

- For specific q-point phonons, construct non-diagonal supercells that fold the target q-point to Γ [27].

Supercell Relaxation

- Perform structural relaxation of the supercell using the same DFT parameters as the primitive cell.

- Ensure forces on all atoms are minimized (typically < 1 meV/Å for precise phonons).

Displacement Generation

- Generate displacement patterns according to the desired phonon wavevectors.

- Apply displacements with magnitude of 0.01-0.04 Å, verifying they break symmetry appropriately [28].

- Utilize symmetry operations to reduce the number of unique displacements.

Force Calculation

- Perform DFT calculations for each displaced configuration.

- Use consistent computational parameters across all configurations.

- Extract forces for all atoms in each configuration.

Force Constant and Phonon Calculation