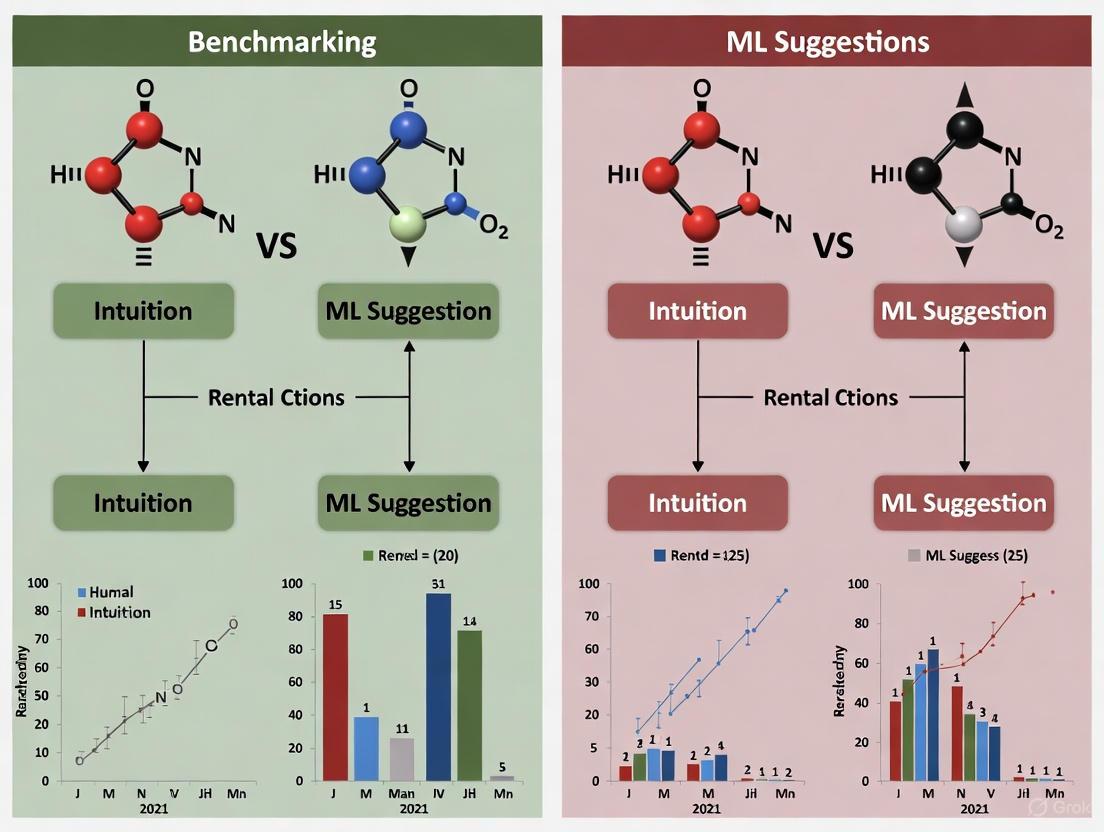

Human Intuition vs. Machine Learning: A New Benchmark for Optimizing Chemical Reactions in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on benchmarking human expertise against machine learning (ML) in reaction optimization.

Human Intuition vs. Machine Learning: A New Benchmark for Optimizing Chemical Reactions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on benchmarking human expertise against machine learning (ML) in reaction optimization. We explore the foundational shift from traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches to data-driven ML strategies. The scope covers the practical application of active learning and transfer learning in laboratory settings, tackles common challenges in human-AI collaboration, and presents validating case studies that demonstrate hybrid teams can achieve superior prediction accuracy and uncover optimal conditions faster than either humans or algorithms working alone. This synthesis aims to guide the effective integration of computational and human intelligence to accelerate synthetic workflows.

The New Frontier of Reaction Optimization: From Chemical Intuition to Data-Driven Discovery

The Limitations of One-Variable-at-a-Time and Pure Intuition

In the relentless pursuit of innovation within fields like drug discovery and chemical synthesis, researchers have traditionally relied on two foundational approaches: the One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) experimental method and the application of pure human intuition. The OFAT method involves systematically varying a single factor while holding all others constant, a process that is simple to implement and understand [1] [2]. Similarly, intuition—described as the heuristics, patterns, and rules-of-thumb derived from years of accumulated experience—has long guided scientists in navigating complex experimental landscapes [3].

However, as the systems under investigation grow more complex, the limitations of these isolated approaches have become increasingly apparent. OFAT struggles to capture critical interaction effects between variables and can be inefficient, often missing optimal conditions [1] [2]. Pure intuition, while powerful, can be inconsistent and difficult to scale or digitize [3]. This article benchmarks these traditional human-centric methods against emerging machine learning (ML) approaches, demonstrating through experimental data how their integration, rather than isolation, creates a superior paradigm for reaction optimization and scientific discovery.

Theoretical Limitations of OFAT and Pure Intuition

The Inefficiencies of One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT)

The OFAT method, while straightforward, suffers from several critical drawbacks that limit its effectiveness in exploring complex experimental spaces.

- Failure to Capture Interactions: OFAT's most significant limitation is its inherent assumption that factors do not interact. In reality, complex systems often exhibit factor interactions, where the effect of one variable depends on the level of another. OFAT is blind to these interactions, which can lead to misleading conclusions and suboptimal process settings [1].

- Inefficient Resource Use: For a given precision in estimating effects, OFAT typically requires more experimental runs than modern designed experiments. This leads to an inefficient use of time, materials, and financial resources [1] [2].

- Limited Optimization Capabilities: The method is inherently poorly suited for identifying optimal factor settings, especially when responses are nonlinear or involve complex interactions between multiple variables. It only explores a single path through the experimental space, potentially missing the true optimum entirely [1] [2].

The Challenges of Pure Intuition in Experimental Design

Human intuition, though valuable, is an unreliable standalone tool for navigating high-dimensional scientific problems.

- Limits in Processing Multivariate Systems: The human mind struggles to process situations with a multitude of interacting variables. This can cause experimenters to resort to intuitive shortcuts that may not adequately map the complex reality of the system being studied [3].

- Inconsistency and Difficulty in Digitization: Intuition is personal and often difficult to articulate or transfer consistently. This makes it a challenge to scale and integrate into standardized, automated discovery platforms, which are increasingly the norm in fields like high-throughput drug discovery [3].

Table 1: Core Limitations of Traditional Approaches

| Aspect | One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) | Pure Human Intuition |

|---|---|---|

| Factor Interactions | Fails to detect or quantify them [1] | Can sometimes perceive them, but inconsistently |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires many runs for limited insight [1] [2] | Unpredictable; can lead to wasted effort on dead ends |

| Handling Complexity | Poor; only explores a single dimension at a time | Becomes overwhelmed by high-dimensional spaces [3] |

| Optimization Power | Limited; can easily miss global optima | Unreliable; not based on systematic search |

| Scalability & Transferability | Easy to execute but scales poorly | Difficult to scale, digitize, or transfer [3] |

Experimental Benchmarking: OFAT and Intuition vs. Machine Learning

Quantifying the Performance Gap in Crystallization Optimization

A pivotal study exploring the self-assembly and crystallization of a polyoxometalate cluster ({Mo120Ce6}) provides direct, quantitative evidence of the performance gap between human intuition, ML and a combined approach [3].

In this experiment, human experimenters, an algorithm using active learning, and human-robot teams were tasked with exploring the chemical space to improve the prediction accuracy for successful crystallization. The results were revealing:

- Human experimenters alone achieved a prediction accuracy of 66.3% ± 1.8%.

- The ML algorithm alone achieved a significantly higher accuracy of 71.8% ± 0.3%.

- Critically, the human-robot collaborative team achieved the highest performance, with an accuracy of 75.6% ± 1.8% [3].

This data demonstrates that while the algorithm outperformed pure intuition, the synergy between human and machine was greater than the sum of its parts, creating a more powerful discovery engine.

Case Study: AI-Driven Drug Discovery

The limitations of traditional trial-and-error methods are particularly evident in drug discovery, where the chemical space is vast (estimated at 10^60 to 10^100 molecules) [3]. AI-driven platforms are now compressing discovery timelines that traditionally took 4-5 years into as little as 18 months, as seen with Insilico Medicine's idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug candidate [4].

Companies like Exscientia report that their AI-driven design cycles are about 70% faster and require 10 times fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms, directly countering the inefficiency of OFAT-like approaches [4]. Furthermore, platforms like Gubra's streaMLine integrate high-throughput experimentation with ML to simultaneously optimize multiple peptide drug properties—such as potency, selectivity, and stability—a task that is fundamentally impossible for OFAT and immensely challenging for pure intuition alone [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Human Intuition Against ML

This protocol is based on the crystallization study of {Mo120Ce6} [3].

- Objective: To quantitatively compare the effectiveness of human intuition, an active learning algorithm, and their combination in exploring a chemical space and modeling crystallization outcomes.

- Experimental System: The self-assembly and crystallization of the polyoxometalate cluster Na6[Mo120Ce6O366H12(H2O)78]·200H2O.

- Methodology:

- Human Intuition Arm: Experienced chemists propose experiments based on their knowledge and heuristics. Their proposed experiments are conducted, and the results are used to build a predictive model.

- Machine Learning Arm: An active learning algorithm selects experiments sequentially based on a predefined acquisition function (e.g., aiming to reduce model uncertainty). These experiments are conducted, and the data is used to build a predictive model.

- Collaborative Team Arm: The human experimenters and the algorithm work in tandem. The algorithm suggests experiments, which are reviewed, and potentially modified, by the human experts before being conducted.

- Key Measurements: The primary metric is the prediction accuracy of the models developed by each arm, validated on a held-out test set of experimental conditions [3].

Protocol 2: Integrated AI and Automation for Reaction Optimization

This protocol reflects the workflows used in modern AI-driven discovery platforms [5] [4].

- Objective: To rapidly identify optimal reaction conditions (e.g., for a peptide synthesis) by integrating automated high-throughput experimentation with machine learning.

- Experimental System: A target reaction, such as the synthesis of a novel GLP-1 receptor agonist [5].

- Methodology:

- Design of Experiments (DOE): A factorial or response surface design is used to define a diverse set of initial reaction conditions, varying multiple factors (e.g., temperature, catalyst, concentration) simultaneously. This contrasts with OFAT by design [1].

- High-Throughput Experimentation: The reactions are conducted in a parallelized, automated platform (e.g., using robotics).

- In-line Analytics: The reaction outcomes are analyzed using automated solution like Chrom Reaction Optimization, which tracks starting materials and products across many reactions [6].

- Machine Learning-Guided Optimization: A machine learning model (e.g., on the

streaMLineplatform) uses the results to predict the outcome of untested conditions and suggests a new set of promising experiments to run, creating a closed-loop "design-make-test-analyze" cycle [4] [5].

Diagram 1: Closed-Loop AI Optimization Workflow. This iterative process integrates design, automation, and machine learning to efficiently find optimal conditions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Experimentation

| Solution / Platform | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chrom Reaction Optimization [6] | Software | Automates the analysis of large chromatography datasets from parallel reactions, enabling quick comparison of reaction outcomes. |

| streaMLine [5] | AI Platform | Combines high-throughput data generation with ML models to guide the simultaneous optimization of multiple drug candidate properties (e.g., potency, stability). |

| Exscientia's AutomationStudio [4] | Integrated Platform | Uses state-of-the-art robotics to synthesize and test AI-designed molecules, creating a closed-loop design-make-test-learn cycle. |

| AlphaFold & proteinMPNN [5] | AI Modeling Tools | Enables de novo peptide design by predicting protein structures and generating compatible amino acid sequences for a given 3D backbone. |

The Superior Alternative: Integrated Frameworks and Designed Experiments

The experimental evidence points toward a superior path that moves beyond the limitations of OFAT and pure intuition.

Design of Experiments (DOE)

DOE is a structured, statistical method that addresses the core failings of OFAT. Its key principles include [1]:

- Simultaneous Variation: Multiple factors are varied together, allowing for the efficient estimation of both main effects and critical interaction effects.

- Randomization: Running experiments in a random order helps minimize the impact of lurking variables and confounding factors.

- Replication: Repeating experimental runs provides an estimate of experimental error and improves the precision of effect estimates.

- Blocking: A technique to account for known sources of variability (e.g., different equipment or operators).

The Human-Machine Collaboration Framework

The most effective approach is not to replace the scientist but to augment them. The {Mo120Ce6} crystallization study proves that a human-robot team can outperform either alone [3]. In this framework:

- The machine learning system handles the brute-force computation, pattern recognition in high-dimensional data, and systematic exploration of the parameter space.

- The human researcher provides domain expertise, contextual knowledge, and strategic oversight. They can interpret unexpected results, incorporate "soft" knowledge, and guide the overall research hypothesis.

Diagram 2: The Augmented Scientist Framework. This synergistic relationship leverages the complementary strengths of human and artificial intelligence.

The evidence is clear: while the One-Factor-at-a-Time method and pure human intuition have served as foundational tools in scientific research, their limitations in efficiency, scope, and power are too great to ignore in the face of modern complexity. Benchmarking studies consistently show that machine learning can outperform pure intuition and that the most powerful results are achieved through collaboration between human and machine [3].

The future of optimization in drug discovery and chemical research lies not in choosing between human expertise and artificial intelligence, but in strategically integrating them. By replacing OFAT with statistically sound Design of Experiments and augmenting chemical intuition with machine learning, researchers can create a more powerful, efficient, and insightful discovery process. This synergistic approach is already delivering tangible results, compressing development timelines and enabling the systematic exploration of vast combinatorial spaces that were previously intractable.

In the field of chemical synthesis and drug development, optimizing reactions is a fundamental yet resource-intensive process. The emergence of machine learning (ML) and automated laboratories has revolutionized this process, prompting a critical question: how do we definitively measure success when comparing these new methods against traditional human intuition? This guide objectively compares the performance of human-driven, ML-driven, and collaborative human-ML strategies, providing a framework for researchers to evaluate optimization approaches based on standardized, quantitative benchmarks.

Quantifying Success: Key Performance Metrics

In optimization campaigns, "success" is not a single endpoint but a measure of efficiency and effectiveness in navigating complex experimental landscapes. The table below summarizes the core metrics used for objective comparison.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Benchmarking Optimization Performance

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Acceleration Factor (AF) [7] | The ratio of experiments a reference strategy needs to reach a target performance level compared to an active learning strategy ((AF = n{ref} / n{AL})). | An AF of 6 means the ML strategy is 6 times faster (requires 6 times fewer experiments) than the reference method. |

| Enhancement Factor (EF) [7] | The improvement in performance (e.g., yield) after a given number of experiments, normalized against random sampling ((EF = (y_{AL} - \text{median}(y)) / (y^* - \text{median}(y)))). | A higher EF indicates the strategy finds significantly better results within the same experimental budget. |

| Prediction Accuracy [3] | The accuracy of a model (or human expert) in predicting successful reaction outcomes. | Directly measures the quality of decision-making; higher accuracy leads to fewer failed experiments. |

Experimental Benchmarking: Protocols and Outcomes

The following section details specific experimental setups and results that have directly compared the performance of human intuition, ML algorithms, and hybrid teams.

Human vs. Machine in Crystallization Exploration

A foundational study directly pitted human experimenters against a machine-learning algorithm in exploring the crystallization space of a polyoxometalate cluster, {Mo120Ce6} [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To model and identify optimal conditions for the crystallization of the cluster.

- Search Space: A complex landscape of chemical parameters affecting self-assembly and crystallization.

- Methodology: Human chemists and an active learning algorithm performed separate campaigns to explore the space and build predictive models. Their performance was evaluated based on the accuracy of their models in predicting successful crystallization outcomes.

Performance Outcomes:

- Human Experimenters: Achieved a prediction accuracy of 66.3% ± 1.8% [3].

- Algorithm Alone: Achieved a higher accuracy of 71.8% ± 0.3% [3].

- Human-Robot Team: The collaborative approach achieved the highest accuracy of 75.6% ± 1.8%, demonstrating that the combination of human and machine can outperform either alone [3].

Large-Scale Reaction Optimization with MINERVA

In pharmaceutical process chemistry, the "Minerva" ML framework was tested in a 96-well high-throughput experimentation (HTE) campaign for a challenging nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reaction, navigating a space of 88,000 potential conditions [8].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: Maximize yield and selectivity for a Ni-catalyzed Suzuki coupling.

- Search Space: High-dimensional space (88,000 conditions) involving catalysts, ligands, solvents, and other parameters.

- Methodology: The ML-driven Bayesian optimization workflow was initiated with quasi-random sampling and then used a Gaussian Process regressor to guide subsequent experiments. Its performance was compared against traditional chemist-designed HTE plates.

Performance Outcomes:

Benchmarking Self-Driving Labs (SDLs)

A comprehensive review of SDL benchmarking studies provides a meta-analysis of performance gains across various chemical and materials science domains [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: Quantify the acceleration provided by SDLs using the metrics of AF and EF.

- Methodology: The analysis reviewed numerous studies that compared SDLs using Bayesian optimization against reference strategies like random sampling, grid searches, or human-directed experimentation.

Performance Outcomes:

- Acceleration Factor (AF): The median reported AF for SDLs is 6, meaning they typically require six times fewer experiments to achieve a target performance than the reference method. This factor tends to increase with the dimensionality of the search space [7].

- Enhancement Factor (EF): Reported EF values vary but consistently peak after conducting 10–20 experiments per dimension of the search space [7].

The following table synthesizes the quantitative results from the cited experiments, offering a direct comparison of the optimization strategies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Optimization Strategies

| Strategy | Reported Performance | Key Advantage | Context / Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Intuition | Prediction accuracy: 66.3% [3] | Excels with incomplete information and established chemical rules [3]. | Struggles in high-dimensional spaces with complex variable interactions [9]. |

| ML Algorithm Alone | Prediction accuracy: 71.8% [3]; Median AF of 6 vs. reference methods [7]. | Superior efficiency and speed in large, complex parameter spaces [8] [7]. | Can be a "black box"; may require large, high-quality data and can struggle with extrapolation [3]. |

| Human-ML Collaboration | Prediction accuracy: 75.6% [3]; Outperformed human or ML alone in reaction discovery [3]. | Maximizes strengths of both: human context and algorithmic processing power [3]. | Requires effective integration and communication between human experts and the algorithmic system. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and platforms are central to modern, data-driven reaction optimization campaigns.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Optimization

| Reagent / Platform | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [10] | A target engagement assay used to validate direct drug-target binding in physiologically relevant environments (intact cells), closing the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotic Platforms [8] [9] | Automated systems that enable highly parallel execution of numerous miniaturized reactions, making the exploration of vast condition spaces cost- and time-efficient. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms [8] [7] | A class of machine learning algorithms that balance the exploration of unknown regions and the exploitation of known promising areas to find optimal conditions with minimal experiments. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) [9] | A community-driven, open-access database intended to serve as a standardized benchmark for training and validating global reaction condition prediction models. |

The benchmarks for success in optimization are clear and quantifiable. While ML-driven strategies consistently demonstrate superior efficiency (AF) and the ability to enhance outcomes (EF) in complex spaces, the highest performance is achieved through collaboration. The synergy between human intuition and machine learning, as evidenced by the highest prediction accuracy, defines the current gold standard.

The field is moving toward tighter integration of these approaches. Future success will be driven by platforms that seamlessly blend automated, data-rich experimentation with tools that augment—rather than replace—the chemist's expertise. This will be crucial for addressing the pressing challenges of R&D productivity in the pharmaceutical industry and beyond [10] [11].

The exploration of chemical space, once a domain guided predominantly by human intuition and resource-intensive experimentation, is undergoing a profound transformation. The estimated >10⁶⁰ drug-like molecules represent a frontier too vast for traditional methods to navigate efficiently [12]. In response, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful compass, enabling researchers to traverse this expansive territory with unprecedented speed and precision. This shift is particularly evident in reaction optimization and molecular design, where the synergy between high-throughput experimentation (HTE) and ML algorithms is accelerating the discovery of optimal reaction conditions and novel functional molecules [13] [8]. The central question facing researchers today is no longer whether to integrate ML into their workflows, but how to effectively benchmark these computational approaches against the nuanced understanding of human experts. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance of contemporary ML frameworks against traditional, intuition-driven methods, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their experimental strategies.

Performance Benchmark: Machine Learning vs. Human Intuition

Recent studies have quantitatively compared ML-driven optimization with traditional, chemist-designed approaches. The results demonstrate that ML frameworks can not only match but significantly exceed the performance of human intuition in complex optimization campaigns.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML vs. Human Experts in Reaction Optimization

| Optimization Method | Reaction Type | Key Performance Metric | Result (ML) | Result (Human Expert) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minerva ML Framework [8] | Ni-catalyzed Suzuki Coupling | Area Percent (AP) Yield / Selectivity | 76% / 92% | Failed to find successful conditions |

| Minerva ML Framework [8] | Pharmaceutical Process Development (API synthesis) | Conditions achieving >95% AP Yield & Selectivity | Multiple conditions identified | Benchmark not met in comparable timeframe |

| ActiveDelta Method [14] | Drug Candidate Identification | Performance while maintaining chemical diversity | Outperformed standard approaches | Standard approach performance |

| Optimization Method | Computational Efficiency | Experimental Efficiency | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minerva ML Framework [8] | High-dimensional search spaces (up to 530 dimensions) | Identified improved process conditions in 4 weeks vs. a previous 6-month campaign | Accelerated development timelines |

| ML-Guided Docking [12] | Reduced screening cost by >1,000-fold vs. standard docking | Viable for multi-billion-compound libraries | Unlocks screening of ultralarge chemical spaces |

| Human Expert Intuition [8] [15] | Limited by cognitive constraints | Relies on serendipitous discovery and iterative OFAT testing | Domain knowledge and heuristic understanding |

The data reveals that ML approaches excel in navigating high-dimensional parametric spaces and extracting optimal conditions from thousands of possibilities, a task where human cognitive limitations become a bottleneck [16] [8]. For instance, in a direct experimental validation, an ML workflow (Minerva) exploring 88,000 conditions for a challenging nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reaction identified high-performing conditions that had eluded chemists designing two traditional HTE plates [8]. Furthermore, ML dramatically accelerates process development, as evidenced by a case where an ML framework condensed a 6-month development campaign into just 4 weeks [8].

However, the role of human expertise remains crucial. The most successful strategies leverage a synergistic "human-in-the-loop" approach, where human intuition curates data, defines fundamental model features, and provides validation [14] [15]. For example, the Materials Expert-AI (ME-AI) model "bottles" the invaluable intuition of human experts into quantifiable descriptors, then generalizes and expands upon this insight [15].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Machine Learning-Guided Reaction Optimization

The following protocol details the ML-driven workflow for reaction optimization, as exemplified by the Minerva framework [8].

Objective: To autonomously identify reaction conditions that maximize one or more objectives (e.g., yield, selectivity) within a defined chemical space.

Materials:

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform: Automated robotic system for miniaturized, parallel reaction execution (e.g., 24, 48, or 96-well plates) [8].

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC, LC-MS, or GC-MS for high-throughput analysis of reaction outcomes.

- Computational Environment: Software for machine learning (e.g., Python with libraries for Gaussian Processes and Bayesian optimization).

Procedure:

- Search Space Definition: A chemist defines a discrete combinatorial set of plausible reaction conditions, including categorical variables (e.g., ligands, solvents, additives) and continuous variables (e.g., temperature, concentration). Practical constraints are applied to filter out unsafe or impractical combinations [8].

- Initial Sampling: The algorithm selects an initial batch of experiments (e.g., 96 conditions) using quasi-random Sobol sampling to maximize diversity and coverage of the reaction space [8].

- High-Throughput Experimentation: The initial batch is executed automatically on the HTE platform, and the reactions are analyzed to obtain outcome data (e.g., yield, selectivity).

- Machine Learning Model Training: A machine learning model (typically a Gaussian Process regressor) is trained on the accumulated experimental data to predict reaction outcomes and their uncertainties for all possible conditions in the search space [8].

- Bayesian Optimization: An acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) uses the model's predictions and uncertainties to select the next batch of experiments that best balances exploration of uncertain regions and exploitation of known high-performing areas [8].

- Iterative Loop: Steps 3-5 are repeated for multiple iterations. The chemist monitors progress and can terminate the campaign upon convergence, stagnation, or exhaustion of the experimental budget [8].

- Validation: The top-predicted conditions are validated experimentally, often at a larger scale.

Machine Learning-Accelerated Virtual Screening

This protocol describes the workflow for using ML to enable virtual screens of ultralarge, make-on-demand chemical libraries [12].

Objective: To rapidly identify top-scoring compounds for a target protein from a multi-billion-molecule library.

Materials:

- Chemical Library: A database of purchasable or make-on-demand compounds (e.g., Enamine REAL Space).

- Docking Software: A structure-based molecular docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide).

- Computational Environment: Software for machine learning (e.g., Python with the CatBoost library and the Conformal Prediction framework).

Procedure:

- Benchmark Docking: A representative subset (e.g., 1 million compounds) of the vast library is docked against the target protein to generate initial training data [12].

- Classifier Training: A machine learning classifier (CatBoost with Morgan2 fingerprints is optimal) is trained to distinguish between top-scoring ("active") and low-scoring ("inactive") compounds based on the docking results from step 1 [12].

- Conformal Prediction: The trained classifier, within the Conformal Prediction (CP) framework, is applied to the entire multi-billion-compound library. The CP framework assigns each compound a "P value" and, based on a user-defined significance level (ε), classifies them as "virtual active," "virtual inactive," or provides no assignment [12].

- Focused Docking: Only the compounds in the much smaller "virtual active" set (typically 1-10% of the original library) are subjected to explicit molecular docking calculations [12].

- Experimental Testing: The top-ranked compounds from the focused docking are procured or synthesized and tested experimentally for binding affinity and/or functional activity.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core closed-loop workflow for autonomous reaction optimization, integrating the experimental and computational components described in the protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The implementation of ML-guided exploration requires a combination of advanced computational tools and physical laboratory assets. The table below catalogs the key solutions that form the foundation of this research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Chemistry

| Tool / Solution | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Automated HTE Reactors [13] [8] | Enables highly parallel execution of numerous miniaturized reactions to generate data at scale. | 96-well plate systems; solid-dispensing robots. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks [8] [12] | Core algorithms for predictive modeling and optimization. | Minerva (for reaction optimization); CatBoost (for virtual screening). |

| Make-on-Demand Libraries [12] [17] | Provide access to billions of synthesizable compounds for virtual screening and generative design. | Enamine REAL Space (billions of molecules); GalaXi; eXplore. |

| Molecular Descriptors [12] | Convert chemical structures into numerical representations for machine learning. | Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP4); Continuous Data-Driven Descriptors (CDDD). |

| Synthesis Planning Models [17] | Ensure generative AI designs are synthetically tractable by creating viable pathways. | SynFormer (Transformer-based generative framework). |

| Lifelong ML Potentials (lMLPs) [18] | Provide accurate, computationally efficient energy calculations for reaction network exploration. | High-dimensional neural network potentials (HDNNPs) with continual learning. |

The benchmarking data and experimental protocols presented in this guide confirm that machine learning has matured into a powerful tool for navigating chemical space, consistently outperforming traditional human-expert-driven methods in terms of speed, efficiency, and the ability to manage complexity. However, the emerging paradigm is not one of replacement, but of collaboration. The most powerful strategy, as exemplified by the ME-AI model, involves "bottling" human intuition to guide AI, which then amplifies and extends that intuition to achieve discoveries that were previously out of reach [14] [15]. As these tools become more accessible and integrated, they promise to significantly accelerate the discovery and optimization of new molecules, reactions, and materials, reshaping the landscape of chemical and pharmaceutical research.

For researchers in drug development and synthetic chemistry, optimizing reactions within the vast chemical space is a monumental task. Traditional methods, reliant on expert intuition and laborious experimentation, often struggle to explore this complexity efficiently. This guide compares the performance of human intuition, machine learning (ML) algorithms, and their collaboration in navigating these challenges with minimal data, providing a benchmark for reaction optimization research.

Direct experimental comparisons reveal that a collaborative approach between human experimenters and machine learning significantly outperforms either working in isolation. This synergy is critical for operating effectively with the "small data" typical in early-stage research, where high-quality data points are often limited to the hundreds or thousands [3].

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics from a prospective study on the crystallization of a polyoxometalate cluster, Na₆[Mo₁₂₀Ce₆O₃₆₆H₁₂(H₂O)₇₈]·200H₂O{Mo₁₂₀Ce₆} [3].

Table 1: Performance Benchmark for Reaction Optimization Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Prediction Accuracy | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Intuition | Relies on chemist heuristics, patterns, and rules-of-thumb [3]. | 66.3% ± 1.8% [3] | Effective in high-uncertainty, low-information scenarios [3]. |

| Machine Learning Alone | Active learning algorithms decide subsequent experiments [3]. | 71.8% ± 0.3% [3] | Computational power to screen large combinatorial spaces [3]. |

| Human-Robot (ML) Team | Human intuition guides and interprets ML-driven exploration [3]. | 75.6% ± 1.8% [3] | Highest accuracy, combining soft and hard knowledge [3]. |

Experimental Protocols: Benchmarking Methodologies

To ensure the reproducibility of these benchmarks, the following section details the core experimental methodologies.

Protocol for Human Intuition Benchmarking

- Objective: To quantify the prediction accuracy of human experimenters using traditional chemical intuition.

- Procedure: Expert chemists were tasked with exploring the crystallization space of the

{Mo₁₂₀Ce₆}cluster. They designed and executed experiments based on their accumulated knowledge, heuristics, and observed patterns, without the aid of algorithmic guidance [3]. - Data Collection: The outcomes of their experiments were used to build a model of the chemical space, and its prediction accuracy for subsequent reactions was measured [3].

Protocol for ML and Collaborative Benchmarking

- Objective: To compare the performance of an active learning algorithm alone and in partnership with human experts.

- Procedure: An active learning algorithm was employed to autonomously decide which experiments to perform next to most efficiently improve its model of the crystallization system. In the collaborative setup, the human experimenters worked alongside the algorithm, providing guidance and interpretation of its predictions [3].

- ML Methodology: The process is self-evolving and adaptive, requiring only a very small fraction (0.03%–0.04%) of the total search space as initial input data. It can simultaneously optimize both real-valued and categorical reaction parameters [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this adaptive, human-in-the-loop ML process for reaction optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key components and their functions in a setup designed for automated or ML-guided reaction optimization, as referenced in the studies [3] [19].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Optimization

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Polyoxometalate (POM) Cluster | The target molecule ({Mo₁₂₀Ce₆}) for crystallization studies; a complex chemical system representing the optimization challenge [3]. |

| Robotic Platform / Automated Reactor | Executes chemical synthesis and crystallization experiments with high precision and reliability, enabling rapid data generation [3]. |

| In-line Analytics | Provides real-time or online analysis of reaction outcomes (e.g., crystal formation, yield), supplying the high-quality data needed for ML algorithms [3]. |

| Active Learning Algorithm | The core "intelligence" that uses acquired data to construct a model of the chemical space and decides the most informative experiments to perform next [3]. |

| Interpretable ML Model | An adaptive algorithm that not only predicts outcomes but also affords quantitative and interpretable reactivity insights, allowing chemists to formalize intuition [19]. |

Comparative Analysis: Strengths and Limitations

Understanding the inherent trade-offs between human and machine approaches is crucial for effective deployment. The following diagram and table outline the core logical relationships and comparative strengths.

Table 3: Strengths and Limitations of Each Strategy

| Strategy | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Human Intuition | Does not require full knowledge; performs well under uncertainty [3]. Effective at identifying which outcomes are valuable and which may be ignored [3]. | The human mind struggles to process situations with a multitude of variables, potentially leading to inconsistent exploration [3]. The process can be time-consuming [3]. |

| Machine Learning (Alone) | Capable of tackling large combinatorial spaces that are infeasible for traditional methods [3]. Can be predictive without needing explicit mechanistic details of the system [3]. | Deep learning approaches require very large amounts of high-quality data to be effective [3]. Models can be predictive but not interpretable, ignoring molecular context [3]. |

| Human-ML Collaboration | Mitigates the "small data" problem by guiding exploration with expert knowledge [3] [19]. Achieves superior performance by leveraging the strengths of both human and machine intelligence [3]. | Requires cultural buy-in and can face resistance from employees skeptical of external best practices [20]. |

The evidence demonstrates that the most effective strategy for reaction optimization in a small-data context is not a choice between human expertise and machine intelligence, but a collaboration between them. The integration of human intuition's heuristic strength with the computational power of adaptive machine learning creates a synergistic team, achieving a level of predictive accuracy and exploration efficiency that neither can alone. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this collaborative model is key to overcoming the core challenge of operating effectively with small data.

Implementing ML-Guided Optimization: Active Learning, Transfer Learning, and HTE Platforms

The optimization of chemical reactions, a cornerstone of drug discovery and materials science, has traditionally relied on researcher intuition and iterative, often labor-intensive, experimental methods. The immense scale of chemical space and the complexity of reaction outcomes make this a formidable challenge. Machine learning (ML) strategies are now transforming this domain by providing data-driven, efficient pathways to discovery. This guide objectively compares three pivotal ML strategies—Bayesian Optimization (BO), Active Learning (AL), and Transfer Learning (TL)—within the context of benchmarking their performance against traditional human intuition for reaction optimization. We will dissect their operational principles, present quantitative performance data from recent studies, and detail the experimental protocols that validate their utility, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting the appropriate tool for their discovery pipeline.

Core Principles and Comparative Workflows

Each ML strategy is designed for a specific type of problem. Understanding their core objectives is key to proper application.

- Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a sample-efficient strategy for finding the global optimum of a black-box, expensive-to-evaluate function. It is ideal when the goal is to find the single best combination of parameters (e.g., reaction conditions that maximize yield) with as few experiments as possible [21] [22].

- Active Learning (AL) is an iterative feedback process designed to train an accurate model of the entire experimental space. It is best suited for tasks like mapping a reaction landscape or identifying a diverse set of successful conditions, where the objective is knowledge acquisition rather than finding a single optimum [23] [24] [25].

- Transfer Learning (TL) aims to leverage knowledge from a data-rich source domain to accelerate learning or improve performance in a data-scarce target domain. It is particularly valuable when starting a new optimization campaign with limited data but with existing datasets on related reactions [26].

The following diagrams illustrate the typical workflow for each strategy, highlighting their iterative nature and key decision points.

Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Active Learning Workflow

Active Transfer Learning Workflow

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

The true measure of these ML strategies lies in their empirical performance. The following tables summarize key quantitative results from recent, high-impact studies, benchmarking their efficiency and success against traditional methods.

Table 1: Benchmarking Bayesian Optimization in Reaction Optimization

| Application Context | Comparison | Key Performance Metric | Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-objective reaction optimization | BO (TSEMO algorithm) vs. NSGA-II (evolutionary algorithm) | Hypervolume improvement & convergence speed | TSEMO achieved better performance and Pareto frontiers within 68-78 iterations [21] | |

| Bioprocess media optimization | BO vs. Design of Experiments (DOE) | Final product titer | BO-designed media yielded higher titers than classical DOE methods [27] | |

| Ultra-fast lithium–halogen exchange | BO for precise parameter control | Precision in residence time control | Achieved sub-second residence time control within 50 experiments [21] |

Table 2: Benchmarking Active Learning in Chemical Discovery

| Application Context | Comparison | Key Performance Metric | Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-scale combination drug screens (BATCHIE) | AL (PDBAL criterion) vs. Fixed Experimental Designs | Fraction of search space explored to find hits | Accurately predicted synergies after exploring only 4% of 1.4 million possible experiments [23] | |

| Discovery of complementary reaction conditions | AL vs. Random Sampling | Coverage of reactant space | AL strategies identified high-coverage condition sets more efficiently than random sampling [25] | |

| DNA sequence optimization | AL vs. One-Shot Optimization | Final expression level | AL outperformed one-shot approaches in complex landscapes with high epistasis [28] |

Table 3: Benchmarking Transfer Learning in Reaction Optimization

| Application Context | Comparison | Key Performance Metric | Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amine-acid C–C cross-coupling | Active Transfer Learning (ATL) vs. Rational Selection | Yield improvement over baseline | ATL consistently improved yields within three batches of experiments [26] | |

| ATL vs. Active Learning or Transfer Learning alone | Speed of identifying viable conditions | ATL was faster than using either strategy in isolation [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of how these benchmarks are established, we detail the core methodologies from the cited studies.

Protocol: Bayesian Optimization for Multi-Objective Reaction Optimization

This protocol is based on the TSEMO (Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective) algorithm framework used to optimize chemical reactions with multiple, competing objectives [21].

- Initialization: A small initial dataset is generated using Latin Hypercube Sampling or other space-filling designs across the input variables (e.g., temperature, concentration, residence time).

- Surrogate Modeling: A Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model is trained to map the input variables to the multiple objective functions (e.g., yield and selectivity).

- Acquisition Function Optimization: The TSEMO acquisition function is used. It works by:

- Sampling a set of random functions from the current GP posterior.

- Identifying the Pareto front for each sampled function using the NSGA-II algorithm.

- Selecting the next point to evaluate by finding the one that, when added to the dataset, causes the largest shift in the identified Pareto front across the samples.

- Experimental Evaluation: The selected reaction conditions are run in the lab, and the objectives (e.g., yield, E-factor) are measured.

- Iteration and Termination: The new data is added to the training set, and the process repeats from Step 2 until a predefined number of iterations is reached or the Pareto front converges.

Protocol: Active Learning for Combination Drug Screening (BATCHIE)

The BATCHIE (Bayesian Active Treatment Combination Hunting via Iterative Experimentation) protocol demonstrates how AL manages immense experimental spaces [23].

- Problem Setup: Define the search space, which can be enormous (e.g., 206 drugs combined over 16 cell lines, resulting in 1.4M possible experiments).

- Initial Batch Design: Use a design of experiments (DoE) approach to create an initial batch of experiments that efficiently covers the drug and cell line space.

- Model Training: Train a hierarchical Bayesian tensor factorization model on all accumulated experimental data. The model decomposes drug combination responses into cell-line effects, individual drug-dose effects, and interaction effects.

- Informatics-Driven Batch Design: For subsequent batches, use the Probabilistic Diameter-based Active Learning (PDBAL) criterion. This algorithm selects the next batch of experiments that is expected to most effectively reduce the uncertainty (the "diameter") of the model's posterior distribution over the entire search space.

- Iteration: The newly designed batch is run experimentally, and the model is updated with the results. This loop continues until the experimental budget is exhausted or model uncertainty is sufficiently low.

- Hit Identification: The final, optimally trained model is used to predict and prioritize the most effective drug combinations across all cell lines for final experimental validation.

Protocol: Active Transfer Learning for Reaction Condition Optimization

This protocol outlines the method used to optimize challenging C(sp3)–C(sp3) cross-couplings by leveraging prior data [26].

- Source Model Training: A source model (e.g., a Random Forest classifier) is trained on a large, previously collected dataset of related reactions (e.g., amine-acid couplings with less challenging substrates).

- Target Task Initialization: The target task is defined with a small or non-existent initial dataset, focusing on challenging substrates (e.g., sterically hindered amines).

- Iterative ATL Cycle:

- Ranking: The transferred source model is used to rank reaction conditions in the target space by their predicted probability of success.

- Experiment Selection: An ensemble of models may be used to reduce uncertainty. The top-ranked conditions (e.g., those with the most "votes" from the ensemble) are selected for experimentation.

- Model Update: The newly collected experimental data from the target space is used to update the source model, refining its predictions for the specific challenge at hand.

- Termination: The cycle is typically run for a small number of iterations (e.g., 3 batches), after which the best-performing conditions identified are validated.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The successful implementation of these ML strategies relies on a combination of computational tools and experimental resources.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Experimentation

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function in ML-Guided Workflows | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Models | Computational | Serves as the probabilistic surrogate model in BO, quantifying prediction uncertainty. | Modeling the relationship between reaction parameters and yield [21] [22]. |

| Random Forest Classifier/Regressor | Computational | A versatile model used for predicting reaction outcomes; often used in AL and TL for its robustness. | Classifying reaction success in active learning screens [26] [25]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Experimental | Enables the rapid parallel synthesis and testing of large batches of reactions or compounds. | Generating initial data and validating batches recommended by AL/BO [23] [29]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software (e.g., BoTorch, Summit) | Computational | Provides algorithms and frameworks for implementing end-to-end Bayesian optimization. | Optimizing multi-objective reaction parameters in an automated workflow [21] [22]. |

| One-Hot Encoded (OHE) Vectors | Computational | A simple representation for categorical variables (e.g., catalyst, solvent) so they can be processed by ML models. | Featurizing reaction conditions for a machine learning classifier [25]. |

| Source Dataset | Data | A pre-existing dataset from a related but distinct chemical context. | Pre-training a model for transfer learning to accelerate a new optimization [26]. |

The benchmarking data clearly demonstrates that Bayesian Optimization, Active Learning, and Transfer Learning are not merely theoretical concepts but are practical tools that outperform traditional human intuition and one-shot optimization methods in complex, resource-constrained environments. BO excels in finding global optima with stunning efficiency, AL is unmatched for intelligently mapping vast chemical spaces, and TL provides a powerful mechanism for bootstrapping new projects with limited data. The choice of strategy is contingent on the research goal: use BO to find a single best answer, AL to understand the entire landscape, and TL to hit the ground running. As these methodologies become more integrated with automated laboratory platforms, they form the core of a new, more rational, and dramatically accelerated paradigm for scientific discovery.

Leveraging High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for Data Generation

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) has emerged as a transformative approach in chemical and pharmaceutical research, enabling the rapid parallel execution of hundreds to thousands of reactions. This capability makes HTE particularly valuable for generating the comprehensive datasets required to benchmark human intuition against machine learning (ML) suggestions in reaction optimization. By systematically exploring chemical space, HTE provides the empirical data necessary to objectively evaluate the predictive performance of computational models versus human expertise. This comparison guide examines how HTE-generated data is advancing our understanding of human-ML collaboration in chemical reaction optimization, with specific focus on performance metrics, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions that facilitate this research.

Performance Comparison: Human Intuition vs. Machine Learning

Quantitative benchmarking studies reveal distinct performance patterns when comparing human intuition, machine learning algorithms, and their collaborative potential in reaction optimization. The following data, synthesized from multiple research studies, provides a comparative analysis of these approaches.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Reaction Optimization Strategies

| Optimization Strategy | Prediction Accuracy | Key Advantages | Limitations | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Experts Alone | 66.3% ± 1.8% [3] | Contextual understanding, pattern recognition in complex systems [3] | Limited capacity for multivariate optimization [3] | Crystallization screening, reaction discovery [3] |

| ML Algorithms Alone | 71.8% ± 0.3% [3] | Rapid exploration of large parameter spaces, data-driven predictions [3] | Requires large, high-quality datasets; limited interpretability [3] | Virtual screening, lead optimization [30] |

| Human-Robot Teams | 75.6% ± 1.8% [3] | Combines computational power with chemical intuition, outperforms either approach alone [3] | Requires specialized infrastructure and workflow integration [31] | Polyoxometalate crystallization, radiochemistry optimization [32] [3] |

The performance advantage of human-ML collaboration demonstrates the synergistic potential of combining computational efficiency with human expertise. This hybrid approach achieves a statistically significant improvement over either method in isolation, particularly in complex optimization scenarios such as the self-assembly and crystallization of the polyoxometalate cluster {Mo120Ce6} [3]. The collaboration effectively navigates the trade-off between the human ability to recognize chemically meaningful patterns and the algorithm's capacity to process multidimensional data.

Table 2: HTE-Generated Benchmarking Data Across Chemical Applications

| Application Domain | HTE Scale (Reactions) | Key Performance Findings | Data Type Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination | 96-well plates [32] | ML-identified conditions successfully scaled 10-fold with maintained efficiency [32] | Radiochemical conversion (RCC) values across substrates [32] |

| Compound Activity Prediction (CARA Benchmark) | Millions of compound records [30] | Model performance varies significantly between virtual screening (VS) and lead optimization (LO) assays [30] | Bioactivity measurements, compound-protein interactions [30] |

| Reaction Condition Optimization | 0.03%-0.04% of search space [19] | LabMate.ML competitive with human experts in double-blind comparisons [19] | Yield optimization, impurity profiling [19] [33] |

Experimental Protocols for HTE-Based Benchmarking

HTE Radiochemistry Optimization Protocol

The following detailed methodology describes an HTE approach for optimizing copper-mediated radiofluorination reactions, generating data for benchmarking human intuition against ML predictions [32]:

Equipment and Materials:

- 96-well reaction blocks (1 mL glass vials)

- Aluminum transfer plates (custom 3D-printed)

- Teflon sealing film (Analytical Sales SKU 96967 or 24269)

- Capping mat (Analytical Sales SKU 99685)

- Multichannel pipettes

- Preheated aluminum reaction block

- [18F]fluoride solution

- Cu(OTf)2 stock solution

- (Hetero)aryl pinacol boronate ester substrates (1-12)

- Additives: pyridine, n-butanol

Procedure:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare homogenous stock solutions of Cu(OTf)2, ligands, and additives. Create substrate solutions in appropriate solvents.

- Plate Setup: Dispense reagents using multichannel pipettes in the following order to ensure reproducibility:

- Cu(OTf)2 solution with additives/ligands

- Aryl boronate ester substrates

- [18F]fluoride solution (approximately 25 mCi total, ~1 mCi per reaction)

- Reaction Execution:

- Use transfer plate to simultaneously move all vials to preheated reaction block

- Seal with capping mat and secure with wingnuts and rigid top plate

- Heat at predetermined temperature for 30 minutes

- Transfer back to cooling position using transfer plate

- Parallel Analysis: Employ one of three quantification methods:

- PET scanners for initial rapid screening

- Gamma counters for quantitative measurement

- Autoradiography for visual assessment

- Data Processing: Calculate Radiochemical Conversion (RCC) for each well, comparing human-predicted outcomes versus ML-predicted outcomes.

This protocol enables the parallel setup of 96 reactions in approximately 20 minutes with minimal radiation exposure, generating statistically significant data for benchmarking human and ML performance [32].

Human-ML Collaborative Benchmarking Workflow

The following DOT script visualizes an integrated workflow for benchmarking human intuition against ML suggestions using HTE-generated data:

Workflow for HTE-Based Human-ML Benchmarking

Crystallization Screening Protocol

For benchmarking human intuition against ML in polyoxometalate crystallization, the following protocol was employed [3]:

Experimental Design:

- Chemical System: Na6[Mo120Ce6O366H12(H2O)78]·200H2O ({Mo120Ce6})

- Parameters Screened: Concentration, temperature, additive identity, mixing conditions

- Human Input: Experimental choices based on chemical intuition and heuristics

- ML Algorithm: Active learning method for experiment selection

- Evaluation Metric: Prediction accuracy for successful crystallization conditions

Implementation:

- Initial dataset generation through HTE screening of crystallization conditions

- Parallel experiment selection by human researchers and ML algorithm

- Performance comparison based on prediction accuracy of crystallization outcomes

- Collaborative phase where human intuition guides algorithmic exploration

This approach demonstrated that the human-robot team achieved 75.6% prediction accuracy, exceeding either human experts (66.3%) or the algorithm alone (71.8%) [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for HTE Benchmarking

The successful implementation of HTE for benchmarking human intuition against ML requires specialized research reagents and equipment. The following table details essential components for establishing these experimental workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTE Benchmarking

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTE Benchmarking | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Blocks & Plates | 96-well reaction blocks (1 mL glass vials) [32], 384-well plates [34] | Parallel reaction execution at micro-scale | Copper-mediated radiofluorination in 96-well format [32] |

| Sealing Systems | Teflon film (Analytical Sales SKU 96967) [32], capping mats (SKU 99685) [32] | Prevent evaporation and cross-contamination | Secure sealing during heated radiofluorination reactions [32] |

| Transfer Systems | Aluminum transfer plates, 3D-printed transfer fixtures [32] | Simultaneous movement of multiple reactions | Efficient transfer to preheated reaction blocks [32] |

| Chemical Libraries | (Hetero)aryl boronate esters [32], diverse ligand sets [35] | Substrate and condition variability for robust benchmarking | Informer libraries for reaction scope evaluation [32] |

| Analysis Integration | UHPLC systems [34], radio-TLC/HPLC [32], automated peak detection [34] | High-throughput data generation for benchmarking | Rapid analysis of 384-well plates in HTE [34] |

| Software Platforms | Katalyst D2D [31], LabMate.ML [19], Peaksel [34] | Workflow integration, data management, and analysis | Bayesian Optimization for ML-guided DoE [31] |

HTE Data Management and Analysis Workflow

Effective benchmarking requires robust data management and analysis pipelines. The following DOT script illustrates the integrated data flow from HTE experimentation through to human-ML benchmarking:

HTE Data Management and Benchmarking Workflow

The integration of High-Throughput Experimentation as a data generation platform for benchmarking human intuition against machine learning reveals several strategic insights for research organizations. The demonstrated performance advantage of human-ML collaboration (75.6% accuracy) over either approach alone establishes a compelling case for hybrid research models. HTE-generated data provides the empirical foundation for objective comparison, enabling organizations to strategically allocate resources between human expertise and computational approaches based on specific research contexts. As HTE methodologies continue to advance in scalability and analytical sophistication, they will increasingly serve as critical validation platforms for evaluating emerging AI tools in chemical research and development. The protocols, reagent solutions, and data management workflows detailed in this comparison guide provide a foundation for implementing these benchmarking approaches across diverse chemical applications.

In pharmaceutical and chemical development, optimizing reactions for maximum yield and selectivity has traditionally relied on expert intuition and laborious, one-factor-at-a-time experimentation. This process remains slow, expensive, and heavily dependent on chemical experience [36]. Machine learning (ML), particularly fine-tuning techniques, is transforming this paradigm by adapting general-purpose models to specific reaction classes, enabling accelerated discovery and development. This guide benchmarks these data-driven approaches against traditional human intuition, providing a comparative analysis of their performance in real-world reaction optimization scenarios.

Fine-Tuning Fundamentals: From Global Knowledge to Local Expertise

Fine-tuning in chemical AI involves adapting models pre-trained on broad reaction databases (source domain) to specialized reaction classes or specific optimization goals (target domain). This process mirrors how chemists use general chemical principles and apply them to specific problems [37].

Global vs. Local Modeling Approaches

Global models exploit information from comprehensive databases to suggest general reaction conditions for new reactions. These models require large, diverse datasets for training but offer wider applicability across reaction types [9].

Local models focus on fine-tuning specific parameters for a given reaction family to improve yield and selectivity. These typically utilize smaller, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) datasets for targeted optimization [9].

Figure 1: Fine-tuning transfers knowledge from general chemical data to specific reaction classes.

Comparative Performance: Fine-Tuning vs. Human Intuition

Experimental studies demonstrate how fine-tuned ML models perform against traditional expert-driven approaches in identifying optimal reaction conditions.

Case Study: Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction Optimization

In a 96-well HTE optimization campaign exploring 88,000 possible conditions for a challenging nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reaction, ML-guided optimization identified conditions achieving 76% area percent yield and 92% selectivity. By comparison, two chemist-designed HTE plates failed to find successful reaction conditions [8].

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Process Development

For active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis, ML fine-tuning identified multiple conditions achieving >95% yield and selectivity for both Ni-catalyzed Suzuki coupling and Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig reactions. This approach led to improved process conditions at scale in just 4 weeks compared to a previous 6-month development campaign [8].

Case Study: Small Data Optimization with LabMate.ML

In nine proof-of-concept studies, the LabMate.ML approach using only 0.03%-0.04% of search space as input data successfully identified optimal conditions across diverse chemistries. Double-blind competitions and expert surveys revealed its performance was competitive with human experts [19].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Approaches

| Optimization Method | Reaction Type | Performance Outcome | Experimental Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Expert HTE | Nickel-catalyzed Suzuki | Failed to find successful conditions | 2 HTE plates | [8] |

| ML Fine-tuning (Minerva) | Nickel-catalyzed Suzuki | 76% yield, 92% selectivity | 96-well campaign | [8] |

| Traditional Development | API Synthesis (Buchwald-Hartwig) | >95% yield/selectivity | 6-month campaign | [8] |

| ML Fine-tuning | API Synthesis (Buchwald-Hartwig) | >95% yield/selectivity | 4-week campaign | [8] |

| Human Experts | Various Transformations | Variable performance | Expert-dependent | [19] |

| LabMate.ML | Nine Diverse Chemistries | Competitive with experts | 0.03-0.04% search space | [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Fine-Tuning in Reaction Optimization

Implementing effective fine-tuning for chemical reactions requires specific methodological considerations.

Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The Minerva framework demonstrates a robust protocol for ML-guided reaction optimization [8]:

- Search Space Definition: Define plausible reaction parameters guided by domain knowledge and practical constraints

- Initial Sampling: Use quasi-random Sobol sampling to select initial experiments, maximizing reaction space coverage

- Model Training: Train Gaussian Process regressors on initial experimental data to predict reaction outcomes

- Acquisition Function: Apply functions balancing exploration and exploitation to select promising next experiments

- Iterative Refinement: Repeat the process with new experimental data until convergence or budget exhaustion

Transfer Learning Implementation

For scenarios with limited data, transfer learning protocols enable effective model adaptation [37]:

- Source Model Selection: Choose models pre-trained on large reaction databases (e.g., Reaxys, ORD)

- Target Data Curation: Compile small, focused datasets relevant to the specific reaction class

- Feature Mapping: Identify generalizable patterns across reaction spaces

- Model Fine-tuning: Adapt pre-trained models using target domain data

- Validation: Prospectively test model recommendations in the laboratory

Figure 2: Bayesian optimization workflow for iterative reaction improvement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of fine-tuning approaches requires both computational and experimental components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Optimization | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Enables highly parallel execution of numerous reactions at miniaturized scales | Screening 96+ reaction conditions in parallel [8] |

| Gaussian Process Regressors | Predicts reaction outcomes and uncertainties for all condition combinations | Modeling complex relationships in multi-parameter spaces [8] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Balances exploration of unknown regions with exploitation of known successes | Guiding experiment selection in Minerva framework [8] |

| Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions | Handles optimization of competing objectives (yield, selectivity, cost) | q-NParEgo, TS-HVI for simultaneous yield/cost optimization [8] |

| Chemical Descriptors | Converts molecular entities into numerical representations for ML | Encoding solvents, catalysts, and additives for algorithm processing [8] |

| Transfer Learning Frameworks | Adapts knowledge from broad reaction databases to specific classes | Fine-tuning pre-trained models for carbohydrate chemistry [37] |

Fine-tuning approaches demonstrate compelling advantages over traditional expert-driven methods for reaction optimization across multiple performance dimensions. ML-guided strategies consistently identify high-performing conditions with significantly greater efficiency, successfully navigating complex chemical spaces where human intuition reaches limitations. For pharmaceutical and chemical development, these data-driven methods offer accelerated timelines, improved success rates, and the ability to systematically explore broader reaction spaces. While chemical expertise remains essential for defining plausible reaction spaces and interpreting results, integrating fine-tuned ML models into optimization workflows represents a paradigm shift in reaction development methodology.

The exploration of chemical space for discovering new molecules and optimizing reactions is a foundational challenge in materials science and drug development. Traditional methods, reliant on chemist intuition and years of specialized training, struggle to efficiently navigate the vast landscape of synthetically feasible molecules, estimated at 10⁶⁰ to 10¹⁰⁰ possibilities [3]. This case study objectively compares the performance of human intuition, machine learning (ML) algorithms, and their synergistic combination for probing the self-assembly and crystallization of a complex polyoxometalate cluster, Na₆[Mo₁₂₀Ce₆O₃₆₆H₁₂(H₂O)₇₈]·200H₂O ({Mo₁₂₀Ce₆}). The findings provide a quantitative framework for benchmarking these approaches within the broader thesis of reaction optimization research [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Crystallization System under Study

The benchmark study focused on the self-assembly and crystallization of the giant polyoxometalate cluster {Mo₁₂₀Ce₆}. This system presents inherent challenges for crystal structure prediction due to the difficulty of finding a digital format that accurately represents a crystalline solid for statistical learning procedures [3].

Human Intuition Protocol

Human experimenters relied on heuristics and accumulated chemical experience to explore the crystallization space. This approach involved pattern recognition, analogies, and rule-of-thumb strategies developed through years of training. The human participants established exploration directions based on a general overview of the system without processing the full multitude of variables, a known limitation of human cognitive capacity [3].

Machine Learning Algorithm Protocol

The machine learning approach employed active learning methodologies to decide which experiments to perform next for most efficiently improving system understanding. The algorithm was designed to navigate the complex parameter space without requiring full mechanistic knowledge of the system. Key components included [3]:

- An interpretable, adaptive machine-learning algorithm

- Capability to optimize multiple real-valued and categorical parameters simultaneously

- Minimal computational resource requirements

- Random sampling of only 0.03%–0.04% of the total search space as initial input data

Human-Robot Team Collaboration Framework

The hybrid approach integrated human intuition with algorithmic precision. Human experts refined ML-suggested experiments, applying judgment to focus on those most likely to yield meaningful results. This strategic selection was crucial for conducting experiments within practical throughput constraints while exploring promising pathways that pure models might overlook [3] [38].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Prediction Accuracy Benchmarking

The performance of each approach was quantitatively evaluated based on prediction accuracy for crystallization outcomes, with the following results:

Table 1: Prediction Accuracy for Crystallization Outcomes

| Experimental Approach | Prediction Accuracy (%) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Human Experimenters Only | 66.3 | ± 1.8 |

| ML Algorithm Only | 71.8 | ± 0.3 |

| Human-Robot Team | 75.6 | ± 1.8 |

Data from the direct comparison study demonstrates that the human-robot team achieved significantly higher prediction accuracy than either approach working in isolation. The collaboration increased accuracy by 3.8 percentage points over the algorithm alone and by 9.3 percentage points over human experimenters working independently [3].

Performance Trajectory Analysis

Research observations identified two key areas of special interest in the performance evolution (conceptualized in Figure 1):

- Area A: Performance where human-robot team results exceed both human-only and algorithm-only performance

- Area B: Intermediate performance between human experimenters and the algorithm [3]

The successful collaboration demonstrated that human-robot teams can consistently operate in Area A, achieving superior performance that beats either humans or robots working alone [3].

Workflow Visualization

Active Learning Experimental Workflow

Human-in-the-Loop Active Learning Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools

| Reagent/Instrument | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Na₆[Mo₁₂₀Ce₆O₃₆₆H₁₂(H₂O)₇₈]·200H₂O | Target polyoxometalate cluster for crystallization studies [3] |

| Interferometric Scattering (iSCAT) Microscopy | Label-free imaging technique for real-time monitoring of individual crystal growth at single-particle resolution [39] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational method for accurate calculation of energies, forces, and stress in crystal structures [40] |

| Neural Network Force Fields (MLFFs) | Machine learning force fields for structure relaxation with uncertainty estimation [40] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Principle framework for guiding experimental selection in data-efficient ways [38] |

Discussion and Research Implications

Synergistic Performance Advantages

The demonstrated 14% relative improvement in prediction accuracy achieved by human-robot teams (75.6% vs. 66.3% for humans alone) provides compelling evidence for integrated approaches in reaction optimization [3]. This synergy addresses fundamental limitations of each method in isolation: human difficulty in processing multivariate systems and ML's requirement for large, high-quality datasets and poor performance outside its knowledge base [3].

Translation to Pharmaceutical Applications

The human-in-the-loop active learning framework shows particular promise for pharmaceutical applications, especially in continuous crystallization optimization for active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) purification. Recent research has demonstrated similar frameworks can handle impurity levels as high as 6000 ppm while maintaining product quality, significantly expanding the acceptable range of contamination for pharmaceutical compounds [38].

Framework for Future Research

This case study establishes a reproducible framework for benchmarking human and machine capabilities in reaction optimization. The quantitative results enable researchers to make evidence-based decisions about resource allocation between human expertise and computational approaches for specific crystallization challenges in drug development pipelines.

Bridging the Gap: Strategies for Effective Human-AI Collaboration in the Lab

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) into chemical reaction optimization promises to accelerate the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle in drug discovery [41]. However, the transition from theoretical potential to reliable laboratory application is fraught with challenges. This guide objectively compares the performance of human expertise and ML suggestions, framing the analysis within a critical thesis: that robust benchmarking must account for failure modes, not just success rates. In the high-stakes environment of pharmaceutical research, understanding when and why ML models fail is as valuable as recognizing their efficiencies. This analysis draws on recent experimental data and case studies to provide a clear-eyed view of the current state of ML-guided optimization, offering researchers a pragmatic framework for integrating these tools.

Theoretical Limits: Inherent Challenges in ML for Chemical Research

Before examining experimental data, it is crucial to understand the fundamental limitations of ML that can necessitate human intervention. These pitfalls are not merely bugs but often stem from the core principles of how these models learn and operate.

- Data Quality and Quantity: ML models, particularly deep learning, require vast amounts of high-quality, well-annotated data. In chemical research, data can be sparse, noisy, and biased towards successful reactions, leading models to perform poorly on novel or under-represented reaction types [42] [43].

- The "Black Box" Problem: The interpretability of complex ML models remains a significant hurdle. When a model suggests a set of reaction conditions, it can be difficult for a chemist to understand the underlying reasoning, making it challenging to trust or refine the suggestion based on chemical intuition [42].

- Over-reliance on Correlation: ML excels at finding correlations in training data but cannot inherently establish causation. A model might associate a specific solvent with high yield based on historical data without understanding the underlying physical organic chemistry principles, leading to poor generalizability [44].

- Algorithmic Bias and Confounding Factors: Models can inadvertently learn and amplify biases present in their training data. For instance, if a dataset over-represents certain catalyst classes, the model may fail to explore potentially superior but less-documented alternatives [44].

Case Study Analysis: Quantitative Performance Comparison