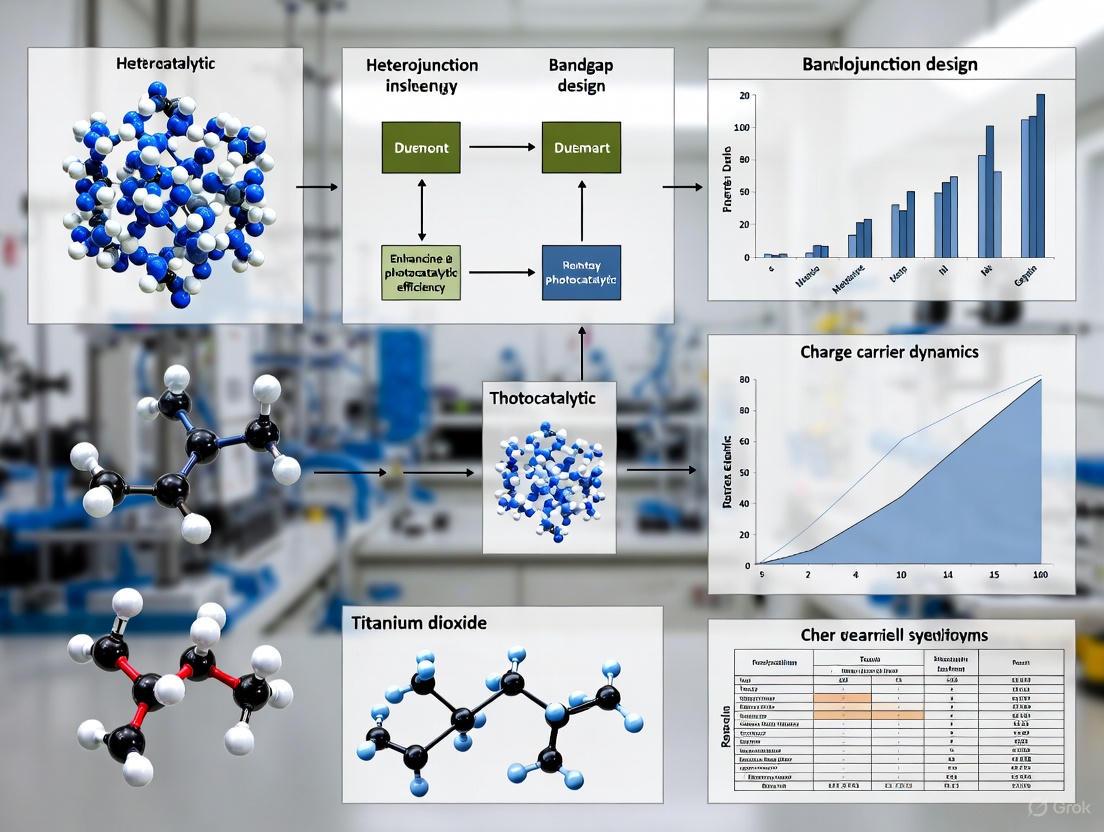

Heterojunction Design for Enhanced Photocatalysis: Principles, Materials, and Cutting-Edge Applications

This comprehensive review explores the strategic design of semiconductor heterojunctions to dramatically enhance photocatalytic efficiency for energy and environmental applications.

Heterojunction Design for Enhanced Photocatalysis: Principles, Materials, and Cutting-Edge Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the strategic design of semiconductor heterojunctions to dramatically enhance photocatalytic efficiency for energy and environmental applications. Covering foundational principles to emerging trends, it systematically examines charge separation mechanisms, material synthesis, interfacial engineering, and performance validation. The article provides researchers and scientists with a methodological framework for designing high-performance heterostructures using novel materials like perovskites, COFs, and MOFs, while addressing key challenges in scalability and computational design for biomedical and environmental remediation applications.

Understanding Heterojunction Fundamentals: Charge Separation Mechanisms and Band Engineering

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is electron-hole recombination and why is it a critical challenge in photocatalysis? Electron-hole recombination is the process where photogenerated electrons in the conduction band recombine with holes in the valence band, annihilating both charge carriers [1] [2]. This is a fundamental problem in single semiconductors because it drastically reduces the number of available electrons and holes that can migrate to the catalyst surface to drive desired chemical reactions, such as water splitting or CO2 reduction [3] [4]. In a single semiconductor, these opposite charges are generated in close proximity, leading to a high recombination rate and limited overall photocatalytic efficiency [3] [5].

2. What are the main types of recombination mechanisms? Recombination mechanisms are broadly categorized into two groups [1] [6]:

- Radiative Recombination (Band-to-Band): An electron directly transitions from the conduction band to the valence band, emitting a photon with energy similar to the band gap of the material [2]. This is prominent in direct-bandgap semiconductors.

- Non-Radiative Recombination: The energy from recombination is released as heat (phonons) rather than light. Key types include:

- Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) Recombination: Occurs through defect energy levels (traps) within the band gap, introduced by impurities or crystal imperfections [1] [6].

- Auger Recombination: The energy from recombination is transferred to another electron or hole, which then relaxes and releases heat [6].

- Surface Recombination: Caused by dangling bonds and defects on the semiconductor surface, which act as efficient recombination centers [6].

3. How does constructing a heterojunction address the recombination problem? A heterojunction is an interface between two different semiconductors. When formed, it creates a built-in electric field due to differences in their Fermi levels and electron affinities [3] [5] [7]. This internal electric field acts as a powerful driving force that spatially separates photogenerated electrons and holes, directing them to different semiconductor components [5] [7]. This physical separation significantly reduces the probability that the electrons and holes will encounter each other and recombine, thereby increasing their lifetime and availability for surface reactions [3] [4].

4. What is the difference between Type-II and S-scheme heterojunctions? Both heterojunction types enhance charge separation but differ in their charge transfer pathways and the resulting redox potential of the separated charges [3] [5].

- Type-II Heterojunction: The band alignment is "staggered." Electrons migrate from Semiconductor B (higher CB) to Semiconductor A (lower CB), while holes move from Semiconductor A (higher VB) to Semiconductor B (lower VB). This achieves good spatial separation but at the cost of the redox potential, as the electrons and holes accumulate on semiconductors with weaker reduction and oxidation power, respectively [3] [5].

- S-Scheme Heterojunction: This newer concept combines a reduction photocatalyst (with higher Fermi level and work function) and an oxidation photocatalyst. The internal electric field causes useless electrons and holes to recombine at the interface, while leaving the most powerful electrons (in the reduction photocatalyst's CB) and holes (in the oxidation photocatalyst's VB) to participate in reactions. This mechanism optimizes both charge separation and the retention of high redox potential [3] [8].

5. What experimental techniques can I use to confirm reduced recombination in my heterojunction? A combination of photoelectrochemical and spectroscopic techniques is essential to confirm improved charge separation [3]:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A direct method. A decrease in PL intensity in the heterojunction compared to the single semiconductors indicates a lower electron-hole recombination rate [9].

- Photoelectrochemical Tests: Measurements of photocurrent response and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). A stronger and more stable photocurrent, along with a smaller arc radius in the EIS Nyquist plot, suggest more efficient charge separation and transfer [9] [7].

- Surface Photovoltage (SPV) Spectroscopy: Directly probes the separation of photogenerated charges by measuring the change in surface potential upon illumination [3].

- Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (TAS): Monitors the decay kinetics of photogenerated charges, providing a direct measurement of their lifetime. A longer lifetime confirms suppressed recombination [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Recombination Rate Persists in Heterojunction

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Poor Interface Quality A disordered or defective interface between the two semiconductors can act as a recombination center instead of facilitating charge separation.

Cause 2: Incorrect Band Alignment The heterojunction may not have the intended Type-II or S-scheme alignment, leading to ineffective or counterproductive charge flow.

- Solution: Prior to synthesis, carefully calculate or experimentally determine the band edge positions (conduction and valence bands) and Fermi levels of both semiconductors. Use techniques like UV-vis spectroscopy (Tauc plot) for band gap and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) for Fermi level and valence band maximum [3].

Cause 3: High Bulk or Surface Defect Density Defects within the semiconductor bulk or on its surface can trap charge carriers and promote non-radiative Shockley-Read-Hall recombination [1] [9].

- Solution: Introduce defect engineering strategies. In some cases, carefully controlled defects like oxygen vacancies can be beneficial by creating intermediate energy levels [9]. In others, passivation of these defects is necessary. Use techniques like post-synthesis annealing in a controlled atmosphere to heal defects or intentionally create beneficial vacancies [9].

Problem: Low Photocatalytic Activity Despite Good Charge Separation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Slow Surface Reaction Kinetics Even if charges are separated and reach the surface, slow reaction kinetics can lead to their accumulation and eventual recombination at the surface [5].

- Solution: Decorate the surface with co-catalysts (e.g., Pt, Ni(OH)2, CoO~x~). Co-catalysts provide active sites that lower the activation energy for the target redox reactions, thereby rapidly consuming the separated charges [7].

Cause 2: Inefficient Charge Migration to Surface The internal electric field may not be strong enough to drive charges to the surface, or the path may be too long.

- Solution: Design nanostructured materials, such as 3D hollow heterostructures or thin films. These architectures can shorten the diffusion distance for charges to reach the surface and provide a larger surface area for reactions [7].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Probing Charge Separation with Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy

Objective: To compare the electron-hole recombination rates of a single semiconductor and a newly synthesized heterojunction.

Materials:

- Powdered samples of single semiconductor A, single semiconductor B, and the A/B heterojunction.

- PL spectrometer with a suitable excitation wavelength (often in the UV or visible range).

- Integrating sphere (optional, but recommended for powder samples for more quantitative analysis).

Methodology:

- Place each powder sample separately in the spectrometer's sample holder, ensuring a consistent and thin layer.

- Set the excitation wavelength to a value that can excite both semiconductors (e.g., the lower band gap edge).

- Record the PL emission spectrum for each sample under identical instrument settings (e.g., slit width, detector gain, scan speed).

- Analysis: Compare the PL intensity of the heterojunction with that of the single semiconductors. A significant quenching of the PL signal in the heterojunction is direct evidence of reduced radiative recombination and improved charge separation across the interface [9].

Protocol 2: Confirming Charge Transfer Pathway with Surface Photovoltage (SPV) Spectroscopy

Objective: To provide direct evidence of the direction of charge transfer in a heterojunction.

Materials:

- Thin film or pressed pellet of the heterojunction sample.

- SPV spectrometer (Kelvin Probe setup).

- Monochromatic light source (e.g., a tunable laser or monochromator with a xenon lamp).

Methodology:

- Place the sample in the SPV setup and ensure good electrical contact.

- Measure the contact potential difference (CPD) between the sample and the Kelvin probe reference in the dark to establish a baseline.

- Illuminate the sample with monochromatic light while recording the change in CPD (this is the SPV signal).

- Analysis: The sign of the SPV signal indicates the type of majority charges accumulating at the surface. For example, a positive SPV signal suggests the upward band bending and accumulation of electrons at the surface. By analyzing the SPV spectra and comparing it with the band structures of the individual components, you can deduce the charge transfer mechanism (e.g., Type-II vs. S-scheme) [3].

Quantitative Data on Performance Enhancement

Table 1: Representative Performance Improvements via Heterojunction Engineering

| Photocatalytic System | Type of Structure | Key Metric | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La₂TiO₅ (LTO) with defects | Defect-engineered single semiconductor | Nitrogen Fixation Rate | 158.13 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ (vs. lower performance for pristine LTO) | [9] |

| Cu₂O─S@GO@Zn₀.₆₇Cd₀.₃₃S | 3D Hollow p-n Heterojunction | H₂ Production Rate | 97 times higher than pure Zn₀.₆₇Cd₀.₃₃S nanospheres | [7] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Heterojunction Photocatalyst Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| g-C₃N₄ | A metal-free, organic semiconductor photocatalyst. Often used as a component in S-scheme heterojunctions due to its appropriate band structure [8] [4]. | Building blocks for heterojunctions with TiO₂ or other semiconductors for water splitting [4]. |

| TiO₂ (e.g., P25) | A benchmark wide-bandgap semiconductor. Its well-understood properties make it an excellent reference and a common component in heterojunctions [3]. | Used in Type-II or S-scheme heterojunctions with narrow-bandgap semiconductors to extend light absorption and enhance charge separation. |

| ZnₓCd₁₋ₓS solid solutions | n-type semiconductors with tunable band gaps and excellent visible light absorption properties [7]. | Coupled with p-type semiconductors (e.g., Cu₂O) to form p-n heterojunctions for photocatalytic H₂ evolution [7]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | A 2D conductive material that acts as an electron transfer mediator and co-catalyst support. It enhances charge separation and provides a platform for building complex structures [7]. | Used as an interlayer in 3D hollow heterostructures to facilitate electron transfer between semiconductors. |

| Nickel-based Salts (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂) | Precursors for non-precious metal co-catalysts (e.g., Ni(OH)₂). These co-catalysts provide active sites for surface reduction reactions, consuming electrons and suppressing surface recombination [7]. | Photodeposited onto heterojunction surfaces to boost H₂ evolution reaction rates. |

Visualizing Recombination and Solutions

The following diagrams illustrate the core problem of recombination in single semiconductors and how heterojunctions provide a solution.

Recombination vs. Heterojunction Charge Flow

S-Scheme Charge Transfer Mechanism

A heterojunction is an interface between two layers or regions of dissimilar semiconductors, which have unequal band gaps [10]. The behavior and performance of a semiconductor junction depend crucially on the alignment of the energy bands at this interface [10]. Proper band alignment engineering is fundamental to enhancing photocatalytic efficiency, as it directly governs the separation and transfer of photogenerated charge carriers, thereby determining the redox capabilities of the system [5].

This guide provides researchers with a foundational understanding of the primary heterojunction classifications, troubleshooting for common experimental challenges, and standard protocols for characterizing these interfaces.

Heterojunction Band Alignment: Core Classifications

Semiconductor interfaces are organized into three fundamental types of heterojunctions based on their band edge alignment: straddling gap (Type I), staggered gap (Type II), and broken gap (Type III) [10] [11]. The characteristics of each are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Fundamental Heterojunction Types

| Heterojunction Type | Band Alignment | Charge Carrier Behavior | Primary Application in Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (Straddling) | Both the CB and VB of Semiconductor B are higher than those of Semiconductor A [10]. | Electrons and holes accumulate in the same semiconductor (the one with the narrower band gap) [11]. | Limited use; often leads to rapid recombination unless one carrier has a much faster transfer rate to the surface [11]. |

| Type II (Staggered) | The CB and VB of Semiconductor B are both higher than the corresponding bands of Semiconductor A, creating a "staggered" profile [10] [5]. | Electrons migrate to the lower CB, and holes migrate to the higher VB, enabling spatial separation of charge carriers [5] [11]. | Highly effective for enhancing charge separation; widely used in traditional photocatalytic systems [5] [11]. |

| Type III (Broken) | The band gaps are broken, with the CB of one material aligned with the VB of the other [10]. | Creates a tunneling junction; not typically used for conventional photocatalysis [10]. | Specialized applications, such as tunnel field-effect transistors [10]. |

Figure 1: Band alignment diagrams for Type-I, Type-II, and Type-III heterojunctions, showing distinct charge carrier pathways.

Advanced Heterojunction Architectures

Beyond conventional classifications, advanced heterojunctions like Z-scheme and S-scheme (Step-scheme) have been developed to overcome the limitation of Type-II systems, where improved charge separation sometimes comes at the cost of reduced redox power [5] [11].

- Z-Scheme Heterojunction: Mimics natural photosynthesis. The electrons from the CB of one semiconductor recombine with the holes from the VB of a second semiconductor via a solid-state mediator. This selectively retains the most energetic electrons and holes in the respective semiconductors, achieving strong spatial charge separation while preserving high redox potentials [11].

- S-Scheme Heterojunction: A newly proposed mechanism consisting of a reduction photocatalyst (RP) and an oxidation photocatalyst (OP) with staggered band structure. The internal electric field (IEF) formed at their interface drives the recombination of less useful electrons and holes, leaving the powerful charge carriers to participate in reactions. This system is particularly effective for maintaining high redox ability and inhibiting charge recombination [5] [11].

Figure 2: S-Scheme heterojunction charge transfer mechanism, combining efficient separation with high redox power.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My heterojunction photocatalyst shows poor charge separation efficiency. What could be the issue? A1: This is a common problem often traced to the band alignment itself or the interface quality.

- Verify Band Alignment: Confirm you have successfully constructed a Type-II or S-scheme heterojunction, not a Type-I, where carriers accumulate and recombine. Use UV-Vis DRS to determine band gaps and XPS valence band spectra to ascertain absolute band positions [11].

- Check Interface Quality: A poor physical interface between the two semiconductors creates a high energy barrier for charge transfer. Ensure synthesis methods like hydrothermal or solvothermal routes promote intimate contact. Techniques like HR-TEM can reveal the quality of the interface [10] [12].

- Characterize Charge Dynamics: Perform photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. A significant quenching of the PL signal in the heterostructure compared to the individual semiconductors indicates successful charge separation. Conversely, a strong PL signal suggests rapid recombination is occurring [11].

Q2: How can I experimentally distinguish between a Type-II and an S-scheme charge transfer mechanism? A2: This is a critical and non-trivial task in modern photocatalysis research. Rely on a combination of techniques rather than a single test.

- Radical Trapping Experiments: Use specific chemical scavengers (e.g., BQ for •O₂⁻, EDTA-2Na for h⁺) to identify the active species in a reaction. In an S-scheme, you typically find evidence of highly oxidizing holes from one semiconductor and highly reducing electrons from the other, which would not be the case in a conventional Type-II [12].

- XPS Analysis: Measure the binding energy shifts of core elements under light irradiation. In an S-scheme, the direction of electron flow due to the internal electric field can cause characteristic shifts in the XPS spectra, which differ from those in a Type-II system [11].

- In-situ Irradiated KPFM: Use Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy under light to directly measure the surface potential changes. This can visually map the direction of electron transfer across the junction, providing strong evidence for the S-scheme pathway [5].

Q3: What are the best practices for synthesizing a high-quality, intimate heterojunction? A3: The synthesis method is paramount.

- Use Sequential Growth Methods: For core-shell structures, methods like atomic layer deposition (ALD) offer exceptional control over thickness and uniformity, creating clean, lattice-matched abrupt interfaces [11].

- Leverage Self-Assembly: Techniques like electrostatic self-assembly of pre-synthesized nanosheets (e.g., Bi₂WO₆ with NixMo₁₋ₓS₂) can create large, intimate contact areas with minimal defects, facilitating excellent charge transport [12] [11].

- Control Crystallization: In-situ hydrothermal/solvothermal methods where one component grows in the presence of the other often yield better junctions than simple mechanical mixing of pre-formed powders [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Bi₂WO₆/NiₓMo₁₋ₓS₂ Heterojunction

The following protocol, adapted from recent literature, outlines the synthesis and basic characterization of a heterojunction photocatalyst for antibiotic degradation [12].

1. Synthesis of Ni-doped MoS₂ (Ni₀.₀₈Mo₀.₉₂S₂)

- Materials: Nickel acetate tetrahydrate (Ni(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O), Sodium molybdate dihydrate (Na₂MoO₄·2H₂O), L-Cysteine, Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve 2 mmol Na₂MoO₄·2H₂O and a calculated amount of Ni(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O (to achieve 8 at% Ni doping) in 35 mL of deionized water. Stir for 30 minutes.

- Add 8 mmol of L-Cysteine (acts as both a sulfur source and a reducing agent) to the solution and stir for an additional hour until homogeneous.

- Transfer the solution into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and maintain it at 200°C for 24 hours.

- After natural cooling, collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation, wash several times with ethanol and deionized water, and dry in a vacuum oven at 60°C for 12 hours.

2. Synthesis of Bi₂WO₆

- Materials: Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O), Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na₂WO₄·2H₂O).

- Procedure:

- Precisely weigh 2 mmol of Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O and 2 mmol of Na₂WO₄·2H₂O.

- Dissolve each precursor separately in 20 mL of deionized water, then mix the two solutions together.

- Stir vigorously for 1 hour to form a homogeneous precursor suspension.

- Transfer the mixture into a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 160°C for 16 hours.

- Cool naturally, collect the product by centrifugation, wash thoroughly, and dry at 60°C.

3. Construction of the Bi₂WO₆/Ni₀.₀₈Mo₀.₉₂S₂ Heterojunction

- Procedure:

- Disperse a specific mass of the as-synthesized Ni₀.₀₈Mo₀.₉₂S₂ powder (e.g., 100 mg) in 40 mL of ethylene glycol via ultrasonication for 30 minutes.

- Add a calculated mass of Bi₂WO₆ powder to achieve the desired weight ratio (e.g., 8 wt% Bi₂WO₆).

- Continue stirring the mixture for 6 hours to ensure intimate contact through self-assembly.

- Collect the final heterojunction composite by centrifugation, wash with ethanol, and dry at 60°C for subsequent use and characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Heterojunction Photocatalyst Research

| Material/Reagent | Function & Role in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| L-Cysteine | A common sulfur source and reducing agent in hydrothermal synthesis of metal sulfides. It also can act as a capping agent to control morphology. | Used in the synthesis of Ni-doped MoS₂ to provide sulfur and control crystal growth [12]. |

| Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O | A standard bismuth precursor for synthesizing bismuth-based semiconductors (e.g., Bi₂WO₆, BiVO₄, BiOX), which are known for their visible-light activity and layered structures. | Reacted with Na₂WO₄ to form the visible-light-active Bi₂WO₆ photocatalyst [12]. |

| Na₂WO₄·2H₂O | A common tungsten source for synthesizing tungsten-containing semiconductors like Bi₂WO₆ or WO₃. | Used as a precursor for the Bi₂WO₆ component in the heterojunction [12]. |

| Ethylene Glycol | A solvent and dispersing medium used in solvothermal synthesis and self-assembly processes. Its high viscosity can help stabilize colloidal suspensions and prevent aggregation. | Used as a medium to facilitate the electrostatic self-assembly between Bi₂WO₆ and Ni₀.₀₈Mo₀.₉₂S₂ nanosheets [12]. |

| Scavengers (e.g., BQ, EDTA-2Na, TBA) | Critical reagents for mechanistic studies. They selectively quench specific reactive species (•O₂⁻, h⁺, •OH) to identify the primary active species in a photocatalytic reaction. | Used to confirm that •O₂⁻ and h⁺ were the primary active species in the degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) [12]. |

The quest for efficient solar-driven technologies has positioned semiconductor photocatalysis as a pivotal strategy for addressing energy and environmental challenges. A significant bottleneck in this field, however, is the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs in single-component semiconductors, which drastically reduces quantum efficiency. Heterojunction design, which involves integrating two or more semiconducting materials, has emerged as a powerful research direction to overcome this limitation. By creating a composite material, it is possible to achieve improved light absorption, more efficient charge separation, and enhanced charge transfer [5]. Furthermore, heterojunctions enable better alignment of band edge potentials with the redox potentials of reactants, promoting the selective formation of desired products with higher yields [5]. Among the various heterojunction configurations, Z-scheme and its evolved form, the S-scheme (Step-scheme), have garnered significant attention for their ability to achieve superior spatial charge separation while maintaining strong redox capabilities [13] [14]. This technical resource center is designed to support researchers in navigating the complexities of these advanced charge transfer models, providing clear troubleshooting guidance and foundational knowledge to accelerate the development of high-performance photocatalytic systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Core Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a Type-II heterojunction and a Z-scheme/S-scheme heterojunction? While both systems feature staggered band alignments, their charge transfer pathways and final redox outcomes are fundamentally different. In a Type-II heterojunction, photogenerated electrons migrate to the semiconductor with the more positive conduction band (CB), while holes migrate to the semiconductor with the more negative valence band (VB). This achieves charge separation but at the cost of retaining charge carriers with weaker redox abilities [5].

In contrast, Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions are designed to mimic natural photosynthesis. They facilitate the recombination of useless electrons and holes at the interface, thereby preserving the most energetic electrons in the CB of the reduction photocatalyst and the most powerful holes in the VB of the oxidation photocatalyst. The S-scheme is a recent refinement of the Z-scheme concept, offering a more direct and clearer mechanistic understanding of the charge transfer process without requiring redox mediators [13] [14].

Q2: Why is the S-scheme considered an optimization of the traditional Z-scheme? The traditional Z-scheme concept, while effective, came with several practical challenges that the S-scheme aims to overcome. The table below summarizes the key distinctions.

Table 1: Comparison of Z-scheme and S-scheme Heterojunctions

| Feature | Traditional Z-Scheme (Liquid-Phase) | All-Solid-State Z-Scheme | S-Scheme (Step-Scheme) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Mediator | Shuttle redox couple (e.g., Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺, IO₃⁻/I⁻) | Solid electron mediator (e.g., Au, Ag, graphene) | No mediator; direct interface |

| Key Limitation | Backward reactions, limited pH stability, light shielding by ions | High cost, photo-corrosion of metals, difficult controllable synthesis | N/A |

| Charge Transfer Path | Indirect, via redox couple | Indirect, via solid conductor | Direct, facilitated by internal electric field |

| Redox Power | Strong | Strong | Strong |

The S-scheme heterojunction simplifies the system by eliminating the need for a mediator. Charge transfer is driven by the built-in electric field (BIEF) formed at the interface, band bending, and Coulombic attraction, which collectively promote the recombination of less useful charges and preserve those with the strongest redox power [13] [14].

Q3: What are the primary experimental techniques used to confirm an S-scheme or Z-scheme mechanism? Confirming the charge transfer pathway is critical and requires a combination of experimental techniques.

- In-situ X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Can detect the shifting of core energy levels and the formation of a built-in electric field at the interface under light illumination.

- Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy: A powerful tool for directly tracking electron transfer paths on ultrafast (femtosecond to picosecond) timescales, allowing researchers to visualize the flow of charge carriers and identify recombination partners [15].

- Electron Spin Resonance (ESR): Used to identify the active radical species (e.g., •O₂⁻, •OH) generated during photocatalysis, which helps verify the potential levels of the surviving electrons and holes.

- Selective Photodeposition: Depositing metal or metal oxide particles (e.g., Pt, PbO₂) selectively on the surfaces where electrons or holes accumulate provides spatial evidence of the charge migration path.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for S-scheme and Z-scheme Heterojunction Experiments

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low charge separation efficiency | Poor interfacial contact between semiconductors. | Optimize synthesis method (e.g., in-situ growth) to ensure intimate contact. |

| Incorrect band alignment, leading to a Type-II pathway. | Re-evaluate semiconductor pair selection using UV-Vis DRS and UPS/XPS to precisely determine band positions. | |

| Weak photocatalytic activity | High recombination of useful charges at the interface. | Introduce atomic-level bridges (e.g., covalent bonds) or control facet engineering to steer charge transfer. |

| Insufficient active sites on the surface. | Design morphologies with high surface area (e.g., porous structures, 2D/2D contact) [16]. | |

| Poor reproducibility of heterojunction | Inconsistent synthesis conditions affecting morphology and interface. | Strictly control reaction parameters (temperature, time, precursor concentration) during hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis. |

| Uncontrolled growth of the second semiconductor. | Use pre-synthesized, uniform primary particles as substrates for secondary growth. | |

| Difficulty in verifying mechanism | Over-reliance on indirect evidence. | Combine multiple characterization techniques (e.g., in-situ XPS, fs-TA, ESR) to build a conclusive case for the S-scheme pathway [15]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of a Z-Scheme MoS₂/WO₃ Heterojunction

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully created a spherical MoS₂/WO₃ composite for efficient Rhodamine B degradation [17].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Reagents for MoS₂/WO₃ Synthesis

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Sodium Tungstate Dihydrate (Na₂WO₄·2H₂O) | Tungsten (W) precursor for WO₃. |

| Ammonium Tetrathiomolybdate ((NH₄)₂MoS₄) | Source of Molybdenum (Mo) and Sulfur (S) for MoS₂. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Provides acidic condition for the precipitation of WO₃. |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for the hydrothermal reaction. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1.65 g of Na₂WO₄·2H₂O in 60 mL of deionized water under magnetic stirring.

- Precipitation of WO₃: Slowly add 3 M HCl solution to the above solution under continuous stirring until the pH reaches approximately 1.5, leading to the formation of a pale-yellow precipitate.

- Addition of MoS₂ Precursor: Add a calculated amount of (NH₄)₂MoS₄ (e.g., 50 wt% relative to the theoretical WO₃ yield) to the mixture and stir for 1 hour to ensure homogeneity.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the final suspension into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. Seal the autoclave and maintain it at 180°C for 24 hours.

- Product Recovery: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool to room temperature naturally. Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation, wash it several times with deionized water and ethanol, and dry it in an oven at 60°C for 12 hours.

Key Characterization Data for MW-50 Composite [17]:

- Degradation Performance: Achieved 94.5% degradation of RhB in 60 minutes under visible light.

- Electrochemical Impedance: Low charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 7.42 × 10² Ω.

- Photocurrent Density: High value of 87 μA·cm⁻², indicating efficient charge separation.

Protocol: Fabrication of an S-scheme ZnO/g-C₃N₄ Heterojunction

This protocol is based on the construction of a hierarchically porous S-scheme heterojunction for H₂O₂ production [13].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential Reagents for ZnO/g-C₃N₄ Synthesis

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Melamine (C₃H₆N₆) | Precursor for graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄). |

| Zinc Acetate Dihydrate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂·2H₂O) | Zinc (Zn) precursor for ZnO. |

| Urea (CH₄N₂O) | Acts as a pore-forming agent and fuel during calcination. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Synthesis of g-C₃N₄: Place 5 g of melamine in a covered alumina crucible and heat in a muffle furnace at 550°C for 2 hours with a ramp rate of 5°C/min. The resulting yellow bulk g-C₃N₄ should be ground into a fine powder.

- Preparation of the Hybrid Precursor: Dissolve a specific mass of the as-prepared g-C₃N₆ powder (e.g., 0.5 g) and an appropriate mass of Zn(CH₃COO)₂·2H₂O (e.g., 12 wt% ratio) in a mixture of water and ethanol via ultrasonication for 30 minutes.

- Addition of Urea: Add a excess of urea to the suspension and continue stirring.

- Calcination: Dry the mixture completely and then calcine the solid powder in an open crucible at 500°C for 2 hours in air.

- Product Collection: The final product is a light-yellow powder of the ZnO/g-C₃N₄ composite.

Key Characterization Data for ZCN12 Composite [13]:

- H₂O₂ Production: Yield of 1544 μmol L⁻¹ under light irradiation.

- Proposed Mechanism: The S-scheme charge transfer pathway was identified as more suitable than a Type-II model, leading to enhanced spatial charge carrier separation and high redox ability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Characterization Techniques

Table 5: Essential Techniques for Mechanistic Investigation

| Technique | Function & Application | Key Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) | Tracks ultrafast charge transfer and recombination pathways [15]. | Direct visualization of electron flow from one CB to another VB in an S-scheme, on femtosecond-picosecond scales. |

| In-situ Irradiated XPS | Probes changes in the electronic structure at the interface under light. | Identifies the direction of electron flow and confirms the formation of a built-in electric field (BIEF). |

| Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) | Detects radical species generated during photocatalysis. | Verifies the presence of ·O₂⁻ (from CB electrons) and ·OH (from VB holes), confirming their high redox potentials. |

| Photoelectrochemical Measurements | Assesses the efficiency of charge separation and transfer in a macroscopic assembly. | Higher photocurrent and lower electrochemical impedance (Rct) indicate better charge separation in the heterojunction [17]. |

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

S-scheme Heterojunction Charge Transfer Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for Heterojunction Synthesis & Validation

Band gap engineering is a fundamental process in materials science that involves controlling or altering the band gap of a semiconductor to achieve desired electronic and optical properties [18]. In the context of photocatalysis, this technique is crucial for developing materials that can effectively harness visible light, which constitutes a significant portion of the solar spectrum [19]. For researchers working on heterojunction design, understanding band gap engineering principles is essential for creating photocatalysts with enhanced charge separation, improved visible light absorption, and superior redox capabilities for applications in environmental remediation and energy production [5] [20].

The band gap refers to the energy difference between the top of the valence band and the bottom of the conduction band in semiconductors and insulators [18]. This energy barrier determines what portion of the solar spectrum a material can absorb and thus directly influences its photocatalytic efficiency [19]. By strategically engineering this band gap through various methods, researchers can tailor materials to maximize their performance under visible light irradiation while maintaining sufficient redox potential to drive target reactions.

Fundamental Concepts & FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the significance of band gap values for visible light photocatalysis?

Answer: The band gap value directly determines the range of light absorption in semiconductor materials. For effective visible light absorption, which spans approximately 1.65 eV to 3.10 eV (750 nm to 400 nm), ideal photocatalysts should have band gaps within or slightly above this range [18]. Materials with wider band gaps (e.g., >3.1 eV) primarily absorb UV light, which constitutes only about 4-5% of the solar spectrum, making them inefficient for solar-driven applications. Band gap engineering aims to reduce wide band gaps to visible light-responsive ranges while maintaining adequate redox potentials for catalytic reactions.

Table: Band Gap Values of Common Semiconductor Materials

| Material | Symbol | Band Gap (eV) @ 302K | Light Absorption Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germanium | Ge | 0.67 | Infrared |

| Gallium Arsenide | GaAs | 1.43 | Visible to Infrared |

| Silicon | Si | 1.14 | Visible to Infrared |

| Gallium Phosphide | GaP | 2.26 | Visible |

| Gallium Nitride | GaN | 3.4 | UV |

| Diamond | C | 5.5 | UV |

| Aluminium Nitride | AlN | 6.0 | UV |

FAQ 2: What is the difference between direct and indirect band gaps, and why does it matter?

Answer: In materials with a direct band gap, the momentum of the lowest energy state in the conduction band and the highest energy state of the valence band have the same value, allowing direct electron transitions with photon absorption/emission [18]. In contrast, indirect band gap materials require a change in momentum during electron transitions, necessitating involvement of both a photon and a phonon (lattice vibration).

This distinction critically impacts photocatalytic efficiency because:

- Direct band gap materials exhibit stronger light absorption and emission properties

- Indirect band gap materials have weaker absorption and lower probability of electron transitions

- Direct band gap semiconductors are generally more efficient for photocatalysis, LEDs, and solar cells [18]

For heterojunction design, understanding the band gap nature of component materials helps predict charge transfer efficiency and interfacial behavior.

FAQ 3: How does band gap engineering enhance charge separation in heterojunctions?

Answer: Band gap engineering facilitates the creation of heterojunctions with optimized band alignment, which significantly enhances charge separation through built-in electric fields [5]. In S-scheme heterojunctions particularly, engineering the band gaps and band positions of the two semiconductors creates an internal electric field at the interface that promotes the recombination of useless charges while preserving the powerful photogenerated electrons and holes with strong redox capabilities [8] [21]. This strategic charge transfer pathway overcomes the limitations of traditional type-II heterojunctions where redox potential is compromised for better charge separation.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Insufficient Visible Light Absorption

Symptoms:

- Low photocatalytic efficiency under visible light

- High performance only under UV irradiation

- Poor quantum yield in visible spectrum

Solutions:

- Cation/Anion Doping: Introduce foreign elements into the host lattice to create intermediate energy levels. For example, copper doping in MgWO₄ as demonstrated in Mg₁₋ₓCuₓWO₄/Bi₂WO₆ heterojunctions [22].

- Solid Solution Formation: Create homogeneous mixtures of isostructural semiconductors with different band gaps to tune optical properties continuously [22].

- Dye Sensitization: Anchor visible-light-absorbing dye molecules to wider band gap semiconductors to extend absorption range [19].

Problem: Rapid Charge Carrier Recombination

Symptoms:

- High photoluminescence intensity

- Low photocurrent generation

- Decreased photocatalytic activity despite good light absorption

Solutions:

- Heterojunction Construction: Combine semiconductors with appropriate band alignment to create internal electric fields that separate electrons and holes [5]. S-scheme heterojunctions have shown particular promise for maintaining strong redox potential while enhancing charge separation [8] [21].

- Co-catalyst Loading: Deposit noble metal nanoparticles (Pt, Au) or metal oxides (NiO, CoOₓ) as electron or hole sinks to extract specific charge carriers.

- Defect Engineering: Carefully introduce specific defects that trap one type of charge carrier, though this requires precision as excessive defects can become recombination centers.

Problem: Inconsistent Band Gap Measurements

Symptoms:

- Variable band gap values for the same material

- Poor correlation between measured band gap and photocatalytic performance

- Difficulty comparing results across different research groups

Solutions:

- Standardized Methodology: Use the Kubelka-Munk transformation on diffuse reflectance UV-Vis spectra, which provides sharper absorption edges and more reliable data compared to log(1/R) methods [23].

- Proper Baseline Correction: Account for pre-absorption edge features that can distort Tauc plot interpretations [23].

- Multiple Technique Validation: Complement optical measurements with XPS, UPS, and IPES spectroscopies for accurate band gap and band position determination [23].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Band Gap Engineering via Solid Solution Formation

Based on: Mg₁₋ₓCuₓWO₄/Bi₂WO₆ heterojunction construction [22]

Materials:

- Magnesium acetate tetrahydrate

- Copper(II) acetate monohydrate

- Sodium tungstate dihydrate

- Bismuth(III) nitrate pentahydrate

- Hydrochloric acid (for pH adjustment)

Procedure:

- Prepare Mg₁₋ₓCuₓWO₄ solid solution by dissolving appropriate molar ratios of magnesium and copper acetates in deionized water.

- Add sodium tungstate solution dropwise under continuous stirring.

- Adjust pH to 9-10 using dilute NaOH or HCl.

- Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and hydrothermally treat at 180°C for 24 hours.

- Separately prepare Bi₂WO₆ by dissolving bismuth nitrate in dilute nitric acid and adding sodium tungstate solution.

- Hydrothermally treat the Bi₂WO₆ precursor at 160°C for 12 hours.

- Combine the two semiconductors through mechanical mixing or secondary hydrothermal treatment.

- Characterize the heterojunction using XRD, DRS, and photoelectrochemical measurements.

Key Parameters:

- Copper doping ratio (x) typically between 0.1-0.5 for optimal visible light absorption [22]

- pH control critical for phase purity

- Secondary thermal treatment temperature should not exceed component degradation points

Protocol 2: S-scheme Heterojunction Construction

Based on: Yb₆Te₅O₁₉.₂/g-C₃N₄ (YTO/GCN) composite synthesis [21]

Materials:

- Ytterbium(III) nitrate pentahydrate

- Tellurium tetrachloride

- Melamine (for g-C₃N₄ synthesis)

- Sodium hydroxide

- Ethane-1,2-diol (ethylene glycol)

Procedure:

- Synthesize g-C₃N₄ by thermal polycondensation: heat melamine at 540°C for 4 hours in a muffle furnace (ramp rate: 10°C/min).

- Prepare YTO via hydrothermal method: mix ytterbium nitrate and tellurium tetrachloride in deionized water.

- Adjust pH to 12 using NaOH solution (2 M).

- Hydrothermally treat at 200°C for 48 hours in Teflon-lined autoclave.

- Wash precipitate with absolute ethanol and deionized water, dry at 60°C overnight.

- Create composites with varying GCN weight ratios (5-90%) by dispersing GCN in ethane-1,2-diol via ultrasonication.

- Add YTO powder, stir for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Hydrothermally treat at 100°C for 4 hours.

- Filter, wash with deionized water, and dry at 60°C overnight.

Characterization Methods:

- XRD for crystal structure analysis

- SEM/TEM for morphology examination

- DRS for band gap determination

- PL spectroscopy for charge separation efficiency

- XPS for chemical states and interfacial interaction

- BET surface area analysis

Material Selection Guide

Table: Material Selection Based on Target Application

| Application | Recommended Materials | Ideal Band Gap Range | Heterojunction Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Reduction | YTO/GCN [21], Bi₂WO₆-based [22], MOFs [23] | 2.0-2.8 eV | S-scheme heterojunction for strong redox power preservation |

| H₂ Evolution | g-C₃N₄-based [21], CdS/MnO₂ [20] | 2.2-2.8 eV | S-scheme or type-II with co-catalysts |

| Pollutant Degradation | YTO/GCN [21], MgCuWO₄/Bi₂WO₆ [22] | 2.3-3.0 eV | Type-II for efficient charge separation |

| Selective Oxidation | In₂O₃/ZnIn₂S₄ [20] | 2.4-2.9 eV | S-scheme for simultaneous oxidation and reduction |

Visualization: Heterojunction Charge Transfer Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Band Gap Engineering Research

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Provide cationic components for semiconductor synthesis | Yb(NO₃)₃·5H₂O for YTO [21], Cu salts for doping [22] |

| Non-Metal Precursors | Source of anionic components | TeCl₄ for YTO [21], Na₂WO₄ for tungsten oxides [22] |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Control morphology and crystal growth | NaOH for pH control [21], surfactants for nanostructuring |

| Carbon/Nitrogen Sources | Form carbon nitride-based semiconductors | Melamine, urea for g-C₃N₄ synthesis [21] |

| Dopant Sources | Modify band structure through elemental incorporation | Cu salts for MgWO₄ doping [22], Ti for MOF modification [23] |

| Solvents for Synthesis | Medium for hydrothermal/solvothermal reactions | Deionized water, ethane-1,2-diol [21] |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Proper characterization is essential for validating band gap engineering outcomes:

Optical Properties:

- Use diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) with Kubelka-Munk transformation for accurate band gap determination [23]

- Employ Tauc plot analysis to distinguish between direct and indirect band gaps [23]

- Apply Kramers-Kronig transformation and Boltzmann regression for complex materials like MOFs [23]

Electronic Structure:

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for surface composition and chemical states [21]

- Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) for valence band positions [21]

- Electron spin resonance (ESR) for detecting active radical species [21]

Structural and Morphological Analysis:

- XRD for crystal structure and phase identification [21]

- SEM/TEM for morphology, interface analysis, and elemental mapping [21]

- BET surface area analysis for porosity and surface properties [21]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of band gap engineering continues to evolve with several promising developments:

Novel Material Systems:

- MOFs and COFs: These porous materials offer tunable band gaps through ligand design and metal cluster selection [23] [20]. Proper band gap analysis is crucial as these materials often exhibit complex electronic transitions [23].

- Rare Earth Materials: Compounds like Yb₆Te₅O₁₉.₂ leverage 4f electronic structures for unique optical properties and catalytic activity [21].

Advanced Heterojunction Concepts:

- Hybrid Charge Separation: Combining asymmetric energetics (AE) and asymmetric kinetics (AK) approaches for superior charge management [5].

- Defect-Engineered Interfaces: Precisely controlled defects at heterojunction interfaces to create additional charge transfer pathways.

System-Level Integration:

- Reactor Design Optimization: Coupling advanced materials with engineered reactor configurations for improved light utilization and mass transfer [19].

- Hybrid Process Integration: Combining photocatalysis with other advanced oxidation processes or electrocatalysis for synergistic effects [19].

For researchers in this field, success requires a multidisciplinary approach combining materials synthesis, sophisticated characterization, theoretical modeling, and practical application testing. The continuous development of new band gap engineering strategies and heterojunction designs promises further enhancements in photocatalytic efficiency for sustainable energy and environmental applications.

Material Synthesis and Application-Specific Heterojunction Design Strategies

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

This section addresses specific issues researchers might encounter when working with emerging photocatalytic heterostructures.

FAQ 1: My g-C3N4-based heterostructure shows rapid electron-hole recombination. How can I improve charge separation?

Answer: Rapid recombination in g-C3N4 is often due to its inherent electronic structure and insufficient interfacial contact in the heterostructure [24] [25]. Implement these solutions:

- Optimize Heterojunction Type: Move from a Type-II to a more advanced S-scheme or Z-scheme heterojunction. These systems more effectively separate electron-hole pairs while preserving the strongest redox potentials [24] [26]. For instance, an S-scheme heterojunction uses a built-in electric field to recombine less useful charges, allowing powerful charges to participate in reactions [26].

- Enhance Interface Engineering: Improve the intimacy of contact at the heterojunction interface. For g-C3N4, this can be achieved by in-situ growth of the second material onto the g-C3N4 surface rather than simple physical mixing [24].

- Apply External Fields: Combine photocatalysis with ultrasound (sonophotocatalysis). The mechanical energy from ultrasound can disrupt charge agglomeration and enhance mass transfer, as demonstrated in BiVO4 systems [27].

FAQ 2: What are the primary strategies to improve the stability of lead halide perovskites for photocatalytic applications?

Answer: The instability of all-inorganic lead halide perovskites (e.g., CsPbX3) under operational conditions (moisture, light, heat) is a critical challenge [28]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Encapsulation: Use protective matrices like polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) or metal-organic frameworks (e.g., ZIF-8) to shield the perovskite from environmental factors. CsPbBr3/PMMA composites have shown high stability while maintaining 99.18% degradation efficiency for methylene blue [28].

- Heterostructure Construction: Coupling perovskites with more stable semiconductors. A CsPbBr3-TiO2 heterostructure improves stability and achieves a 94% removal rate of tetracycline [28].

- Surface Passivation: Treat the perovskite surface with agents that bind to defect sites (e.g., uncoordinated lead atoms), reducing surface energy and preventing degradation initiation [29].

FAQ 3: The photocatalytic performance of my BiVO4 is limited by poor charge transport. How can I address this?

Answer: Poor charge transport is a known limitation of pristine BiVO4 [27] [30]. Solutions involve structural and compositional engineering:

- Construct Isotype Heterojunctions: Create junctions between different crystalline phases of the same material. For example, forming a heterostructure between the monoclinic and tetragonal phases of BiVO4 can create an internal electric field that drives better charge separation [27].

- Form Type-II Heterojunctions with WO3: Coupling BiVO4 with WO3 to create a WO3/BiVO4 heterostructure is a highly effective strategy. This setup facilitates electron transfer from BiVO4 to WO3, reducing recombination. This approach has achieved photocurrent densities of 6.85 mA cm⁻² and high TOC removal for glycerol [30].

- Introduce Oxygen Vacancies: Synthesis conditions that create oxygen vacancies can improve charge separation and provide more active sites, as indicated by shifts in Raman spectra [30].

FAQ 4: How can I overcome the poor solubility and aggregation tendency of Perylene Diimide (PDI) molecules in solution-based processing?

Answer: PDI's strong π-π stacking leads to aggregation and poor processability [26]. Functionalization and compositing are key:

- Chemical Substituents: Introduce hydrophilic ionic groups (e.g., ammonium salts, carboxylic acids, sulfonic acids) or non-ionic polar groups (e.g., polyethylene glycol) at the bay, imide, or ortho positions of the PDI core. This significantly enhances water solubility and disrupts excessive aggregation [26].

- Covalent Bonding to Supports: Anchor PDI molecules to other materials via covalent bonds. For instance, PDI can be connected to amino-functionalized MIL-125(Ti) through amidation reactions, ensuring a stable and well-dispersed heterostructure [26].

- Form Supramolecular Structures: Direct the self-assembly of PDI into defined nanostructures like nanofibers or layered assemblies, which can enhance charge transport properties and create a higher surface area for reactions [26].

Experimental Protocols for Key Heterostructures

This protocol produces a mixed-phase BiVO4 catalyst with enhanced charge separation.

- Key Reagents: Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O), Ammonium vanadate (NH₄VO₃), Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Nitric acid (HNO₃), Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve 2.5 mmol of Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O in 10 mL of 2 M HNO₃. Separately, dissolve 2.5 mmol of NH₄VO₃ in 15 mL of 2 M NaOH with continuous stirring at 70°C.

- Mixing: Slowly add the Bi(NO₃)₃ solution to the NH₄VO₃ solution under vigorous stirring.

- Surfactant Addition: Add a controlled amount of Sodium lauryl sulfate (e.g., 0.2 g) to the mixture. The surfactant dosage is critical for phase control.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the final mixture into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave (50 mL capacity). Seal and maintain it at 180°C for 24 hours.

- Product Recovery: After natural cooling, collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation. Wash repeatedly with deionized water and absolute ethanol to remove impurities.

- Drying: Dry the product in an oven at 60°C for 12 hours to obtain the final powder.

- Characterization: Use X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm the coexistence of monoclinic (JCPDS card no. 14-0688) and tetragonal (JCPDS card no. 14-0133) phases.

This method creates a thin-film heterostructure photoanode for simultaneous hydrogen production and pollutant degradation.

- Key Reagents: Tungsten (W) metal foil, Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%), Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O), Potassium iodide (KI), Vanadyl acetylacetonate (C₁₀H₁₄O₅V), p-Benzoquinone, Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- WO3 Nanoplates Synthesis: Clean a W foil substrate. Prepare a hydrothermal growth solution. React the W foil in a Teflon-lined autoclave to grow vertically-aligned WO3 nanoplates.

- BiVO4 Deposition: Prepare a precursor solution containing Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O, KI, and C₁₀H₁₄O₅V in a mixture of water and ethanol. Drop-cast this solution onto the synthesized WO3 nanoplates.

- Annealing: Anneal the composite film at 450°C in air to crystallize the BiVO4 layer, forming the WO3/BiVO4 heterostructure.

- Testing: Perform photoelectrochemical (PEC) measurements in a 0.5 M Na₂SO₄ electrolyte with and without 0.5 M glycerol. Apply AM 1.5 G illumination and measure photocurrent density. Analyze solution for hydrogen evolution and use TOC analysis to quantify glycerol mineralization.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the photocatalytic performance of various heterostructures for different applications, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Halide Perovskite vs. Traditional Photocatalysts [28]

| Sample | Application | Synthesis Method | Photocatalytic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/TiO₂ | Degradation of Methylene Blue (MB) | Sol-gel | 98.86% degradation (5 mg/L, 250 min) |

| CsPbBr₃/PMMA | Degradation of Methylene Blue (MB) | Electrospinning | 99.18% degradation (5 mg/L, 60 min) |

| TiO₂/PCN-224 | H₂ Production | Vacuum Filtration | 1.88 mmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ H₂ production rate |

| CsPbBr₃ | H₂ Production | Hot Injection | 133.3 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ H₂ evolution rate |

| TiO₂/rGO/Cu₂O | Degradation of Tetracycline (TC) | Hummers method | 99.38% removal (100 mg/L, 40 min) |

| CsPbBr₃–TiO₂ | Degradation of Tetracycline (TC) | Solvothermal | 94% removal (20 mg/L, 60 min) |

Table 2: Performance of g-C3N4 and BiVO4-Based Heterostructures

| Photocatalyst | Application | Performance Metrics | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| WO₃/BiVO₄ | Photoelectrochemical Glycerol Degradation & H₂ Production [30] | Photocurrent density: 6.85 mA cm⁻²; TOC removal: ~82% (120 min). | Dual-functional system for simultaneous energy production and environmental remediation. |

| LaFeO₃/g-C₃N₄/ZnO | Degradation of Bisphenol (BP) and related compounds [28] | 97.43% BP degradation (120 min); >90% degradation for BPA, PNP, DCP (60 min). | Effective for a wide range of persistent organic pollutants. |

| g-C₃N₄/Mg-ZnFe₂O₄ | Dye Degradation [24] | Significant enhancement in dye decomposition. | Highlights the versatility of g-C3N4 composites in water purification. |

| BiVO₄ (Isotype Heterostructure) | Degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) [27] | Enhanced degradation under sonophotocatalysis (visible light + ultrasound). | Synergistic effect of combined irradiation modes improves efficiency. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and their functions in synthesizing and modifying the featured photocatalytic heterostructures.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Heterostructure Research |

|---|---|

| Urea / Melamine / Thiourea | Low-cost, nitrogen-rich precursors for the thermal synthesis of g-C₃N₄ [24] [31]. |

| Bismuth Nitrate Pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O) | Common Bi-precursor for the synthesis of BiVO₄ and Bismuth-based perovskites [27] [30]. |

| Ammonium Vanadate (NH₄VO₃) | Standard V-precursor for the hydrothermal synthesis of BiVO₄ [27]. |

| Perylene Dianhydride | Starting material for the synthesis of various Perylene Diimide (PDI) derivatives [26]. |

| Cesium Bromide (CsBr) / Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Common precursors for the synthesis of all-inorganic CsPbBr₃ perovskite nanocrystals [28]. |

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | Surfactant used to control the crystalline phase (tetragonal vs. monoclinic) during BiVO₄ synthesis [27]. |

| Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) | A polymer used for encapsulating and stabilizing halide perovskites like CsPbBr₃ against environmental degradation [28]. |

Heterojunction Charge Transfer Mechanisms

Understanding the pathway of photogenerated electrons and holes is fundamental to designing efficient heterostructures. The diagrams below illustrate the three primary mechanisms.

Type-II Heterojunction Mechanism

This diagram shows the charge transfer in a Type-II heterojunction, where electrons (e⁻) migrate to Semiconductor B's CB and holes (h⁺) to Semiconductor A's VB. This spatially separates the charges but can reduce the redox power available for reactions [24] [26].

S-Scheme Heterojunction Mechanism

This diagram illustrates the S-scheme mechanism. The internal electric field promotes the recombination of less useful electrons in the OP's CB with less useful holes in the RP's VB. This leaves the most powerful electrons (in the RP's CB) and holes (in the OP's VB) to perform surface redox reactions, achieving both high charge separation and strong redox ability [26].

Experimental Workflow for Heterostructure Synthesis and Testing

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for developing and evaluating a photocatalytic heterostructure, integrating steps from the cited protocols.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when fabricating heterojunction photocatalysts. The guidance is framed within research aimed at enhancing photocatalytic efficiency for applications in environmental remediation and energy conversion.

Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Synthesis

Q1: My hydrothermal product shows low crystallinity and poor photocatalytic activity. What could be wrong? This is often due to incorrect reaction kinetics or contamination.

- Cause Analysis: The crystallinity of hydrothermally synthesized materials is highly sensitive to reaction temperature, time, and precursor concentration. Inadequate parameters can hinder complete crystallization. Impurities from non-precursor reagents can also act as crystallization inhibitors.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Temperature and Duration: Ensure the autoclave reaches and maintains the target temperature for the full duration. Standard crystallization often requires 6 to 24 hours at 120-200°C.

- Optimize Precursor Concentration: Overly high concentrations can lead to amorphous aggregates instead of well-defined crystals. Perform a series of experiments with varying concentrations to find the optimum.

- Check for Contaminants: Ensure all equipment and reagents are clean. Use high-purity precursors (e.g., K₃[Fe(CN)₆] for α-Fe₂O₃) to avoid introducing impurities that disrupt crystal growth [32].

- Use a Mineralizer: Add a mineralizer like NaOH or urea to the reaction mixture. These agents increase the solubility of the precursor material, facilitating the dissolution-recrystallization process necessary for forming highly crystalline products [32].

Q2: How can I control the final morphology of my hydrothermal product? Morphology is controlled by manipulating the relative rates of nucleation and crystal growth.

- Cause Analysis: The morphology (e.g., spheres, rods, cubes) is directed by the use of surfactants or capping agents that selectively adsorb to specific crystal facets, inhibiting their growth and promoting anisotropic shapes.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Introduce a Structure-Directing Agent: Use surfactants like sodium citrate. For example, sodium citrate can assist in the self-assembly of α-Fe₂O₃ nanoparticles into microspheres or microcylinders, with the final shape being dependent on the citrate concentration [32].

- Adjust the Solvent Composition: Mixing water with organic solvents (e.g., ethanol) can alter the surface energy and reaction kinetics, leading to different morphologies.

- Control the Heating Ramp Rate: A slower heating rate can promote the formation of more uniform and thermodynamically stable structures.

Sol-Gel Synthesis

Q3: My sol-gel derived film is cracking during drying. How can I prevent this? Cracking is caused by capillary stresses during the evaporation of the liquid phase.

- Cause Analysis: Rapid drying creates high capillary forces that pull the solid network together, causing stress that exceeds its mechanical strength, resulting in cracks.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Control Humidity: Dry the gel in a controlled humidity environment. Slowly reducing the humidity over several days allows for gradual solvent removal and minimizes stress.

- Use a Drying Control Chemical Additive (DCCA): Additives like formamide or glycerol can reduce capillary pressure by modifying the pore structure and surface tension of the solvent.

- Optimize the Aging Time: Allow the wet gel to age in its own solvent for a longer period (e.g., 24-72 hours). This strengthens the network through continued condensation reactions, making it more resistant to cracking [33].

- Apply Supercritical Drying: For the highest quality aerogels (e.g., TiO₂ aerogels), remove the solvent under supercritical conditions (e.g., using high-temperature CO₂). This avoids the liquid-gas interface entirely, preventing capillary forces and resulting in an uncracked, low-density solid gel [34] [33].

Q4: The bandgap of my sol-gel semiconductor is not optimal for visible light absorption. How can I modify it? The electronic structure can be tuned during the sol-gel process.

- Cause Analysis: The innate bandgap of a pure metal oxide (e.g., TiO₂) may be too wide for efficient visible light utilization.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Dope with Metal or Non-Metal Ions: Introduce dopant precursors directly into the sol. For instance, adding a nitrogen source (e.g., urea) or metal salts (e.g., FeCl₃) to a titanium alkoxide sol can create doped TiO₂ with a narrowed bandgap.

- Employ the Pechini Process: For multi-cation oxides, use the Pechini process. Chelate metal cations (e.g., Sr²⁺, Ti⁴⁺) with citric acid and then form a polymer network with ethylene glycol. This immobilizes the cations, ensuring atomic-level homogeneity upon calcination and preventing the formation of separate binary oxide phases, which is crucial for consistent electronic properties [33].

- Control Calcination Temperature: The final thermal treatment (firing) temperature significantly affects crystallinity, particle size, and defect concentration, all of which influence the bandgap. Optimize this parameter carefully.

Self-Assembly Fabrication

Q5: The components of my heterojunction are not forming an intimate interface, leading to poor charge transfer. This indicates insufficient interfacial contact, which is critical for effective charge separation across the heterojunction [5].

- Cause Analysis: Physical mixing or non-uniform coating fails to create the large, coherent interface needed for efficient electron and hole migration between semiconductors.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Utilize In-Situ Growth: Grow the second semiconductor directly on the surface of the first. For a WO₃@TCN heterojunction, this can be achieved by reacting a tungsten precursor with ammonia released during the thermal polymerization of melamine, followed by calcination to form WO₃ nanoparticles anchored onto the carbon nitride tubes [35].

- Employ Molecular Linkers: Use bifunctional molecules that can chemically bond to both materials, facilitating self-assembly and improving interfacial adhesion.

- Adopt a Charge-Induced Assembly: Manipulate the surface charges (zeta potential) of the pre-synthesized components so they attract each other electrostatically, promoting spontaneous and uniform heterojunction formation.

Q6: My self-assembled structure is unstable and disaggregates under reaction conditions. Instability arises from weak interactions between the building blocks.

- Cause Analysis: The forces holding the assembly together (e.g., van der Waals, hydrogen bonding) may be too weak to withstand the mechanical stress or chemical environment of photocatalytic reactions.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Strengthen Inter-Component Bonds: Replace physical interactions with stronger covalent or coordination bonds. For example, using covalent organic framework (COF) chemistry to link building blocks into a robust 2D network can greatly enhance stability [36].

- Optimize the Assembly Conditions: Parameters such as pH, ionic strength, and concentration are critical for stable assembly. Systematically vary these to find conditions that maximize the strength and number of inter-particle interactions.

- Apply a Stabilizing Overcoat: In some cases, a thin, conformal layer of an inert material (e.g., alumina or silica) can be applied to "lock" the assembled structure in place.

Experimental Protocols for Key Heterojunction Systems

Protocol 1: Hydrothermal Synthesis of α-Fe₂O₃ Microspheres

This protocol details the synthesis of self-assembled hematite microspheres for use as a photocatalyst component [32].

- Objective: To synthesize self-assembled α-Fe₂O₃ microspheres via a sodium citrate-assisted hydrothermal route.

- Materials:

- Precursor: Potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆])

- Structure-directing agent: Sodium citrate

- Base: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

- Solvent: Deionized water

- Procedure:

- Dissolve 1 mmol of K₃[Fe(CN)₆] and 1.7 mmol of sodium citrate in 10 mL of deionized water to form a homogeneous solution.

- Introduce 10 mL of a NaOH aqueous solution (150 mM final concentration) into the mixture.

- Irradiate the mixture with ultrasonic waves for 5 minutes to ensure thorough mixing.

- Transfer the solution into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave (e.g., 50 mL capacity).

- Seal the autoclave and maintain it at 180°C for 12 hours in an oven.

- After natural cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting red precipitate by centrifugation.

- Wash the product sequentially with deionized water and absolute ethanol several times.

- Dry the final product in an oven at 60°C for 6 hours.

- Key Parameters for Heterojunction Design: The sodium citrate acts as a chelating agent and shape modifier, enabling the formation of a microsphere morphology through self-assembly. This structure provides a high surface area for subsequent coupling with other semiconductors.

Protocol 2: Self-Assembly of a WO₃@Tubular Carbon Nitride (TCN) Heterojunction

This protocol describes the creation of a heterojunction between WO₃ and metal-free carbon nitride for enhanced visible-light photocatalysis [35].

- Objective: To fabricate a WO₃@TCN heterojunction photocatalyst using a self-assembly method driven by pH modulation.

- Materials:

- TCN precursor: Melamine

- WO₃ precursor: Sodium tungstate or other tungsten salts

- Acid for pH regulation: Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

- Solvent: Deionized water

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of TCN:

- Hydrothermally treat melamine to form a hexagonal prismatic melamine-cyanuric acid (MC) supramolecular precursor.

- Thermally polymerize this precursor. The center of the prisms sublimates, yielding hollow tubular carbon nitride (TCN) [35].

- In-Situ Growth of WO₃ on TCN:

- Disperse the as-prepared TCN in water.

- Add the tungsten precursor to the suspension.

- During the thermal polymerization of melamine, released ammonia reacts with the WO₃ precursor to form ammonium tungstate.

- Acidify the system with HCl, causing ammonium tungstate to convert to tungstic acid.

- A final calcination step converts tungstic acid to WO₃ nanoparticles anchored on the TCN surface, forming the WO₃@TCN heterojunction [35].

- Synthesis of TCN:

- Key Parameters for Heterojunction Design: This one-pot, in-situ method ensures an intimate interface between WO₃ and TCN. The hollow tube structure of TCN facilitates charge carrier migration, while the heterojunction promotes spatial separation of photogenerated electrons and holes, which is critical for enhancing photocatalytic activity [35].

Protocol 3: Sol-Gel Synthesis of a g-C₃N₄ Based Covalent Organic Framework (COF)

This protocol outlines the chemical modification of g-C₃N₄ to create a COF with optimized electron-hole separation [36].

- Objective: To synthesize CN-306, a modified g-C₃N₄ COF, for highly efficient H₂O₂ production.

- Materials:

- g-C₃N₄ precursor: Urea

- Organic linkers: Terephthalaldehyde, para-aminobenzaldehyde, p-nitrobenzaldehyde

- Catalyst: Acetic acid

- Solvent: Ethanol

- Procedure:

- Synthesize Bulk g-C₃N₄ (Product A): Heat urea at 580°C in air for 4 hours. Wash and dry the resulting yellow solid.

- Form Intermediate Products (B, C, D):

- React Product A with terephthalaldehyde in ethanol with acetic acid catalyst at 80°C for 12 hours to yield Product B.

- Under identical conditions, react B with para-aminobenzaldehyde to obtain Product D.

- Synthesize CN-306: Condense Product D with p-nitrobenzaldehyde in ethanol using acetic acid as a catalyst.

- Purification: Wash and dry the final product [36].

- Key Parameters for Heterojunction Design: The introduction of a strong electron-withdrawing group (nitro group) via molecular engineering alters the electron cloud density distribution of the conjugated framework. This modification enhances the separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs by extending the distance between them, a fundamental principle for improving the quantum efficiency of photocatalysts [36].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Photocatalysts Synthesized via Different Methods

| Synthesis Method | Photocatalyst System | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Assembly | 3% WO₃@TCN | Rate constant for tetracycline degradation | 2x higher than pure TCN | [35] |

| Self-Assembly | CN-306 COF | H₂O₂ Production Rate | 5352 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ | [36] |

| Self-Assembly | CN-306 COF | Surface Quantum Efficiency (at 420 nm) | 7.27% | [36] |

| Theoretical (Heterojunction) | g-C₁₂N₇H₃ /g-C₉N₁₀ | Bandgap (HSE06 calculation) | 3.24 eV (marginal visible light) | [4] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Heterojunction Fabrication

| Reagent Category | Example Reagents | Primary Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Precursors | Metal alkoxides (e.g., Ti(OR)₄), K₃[Fe(CN)₆], Melamine, Urea | Source of metal or non-metal elements for the semiconductor oxide or framework. |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Sodium citrate, Pluronic surfactants, CTAB | Control morphology and particle size by selective facet adsorption. |

| Chelating Agents | Citric Acid (for Pechini Process) | Sterically entrap cations in solution to ensure compositional homogeneity in multi-cation oxides. |

| Catalysts & pH Modulators | Acetic Acid, HCl, Ammonia, NaOH | Control hydrolysis and condensation rates in sol-gel; trigger in-situ reactions in self-assembly. |

| Solvents & Drying Agents | Ethanol, Ethylene Glycol, Formamide (DCCA) | Dissolve precursors; control reaction medium; minimize capillary stress during gel drying. |

Process Visualization Diagrams

Heterojunction Charge Transfer Mechanisms

Hydrothermal Self-Assembly Workflow

Sol-Gel and Self-Assembly Hybrid Process

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common challenges in photocatalytic H₂ production and CO₂ reduction, with a focus on systems utilizing heterojunction designs.

FAQ 1: Why is the overall quantum efficiency of my photocatalytic system so low?

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Rapid Charge Recombination: This is a primary cause of low efficiency [37]. If using a single semiconductor, consider constructing a heterojunction, specifically an S-scheme heterojunction, to spatially separate electrons and holes and enhance redox power [8] [38] [39].

- Insufficient Active Sites: The surface may not provide enough locations for the reaction. Solution: Integrate a co-catalyst (e.g., Pt, Ni) to lower the activation energy for H₂ evolution or CO₂ reduction and provide more active sites [37].

- Limited Light Absorption: The photocatalyst may only absorb UV light, which constitutes a small portion of the solar spectrum [37]. Solution: Employ bandgap engineering through doping or form heterojunctions with narrow-bandgap semiconductors (e.g., modified SrTiO₃, CdS) to enhance visible light absorption [37] [40].

FAQ 2: My system produces hydrogen, but the yield is poor and the rate decreases over time. What could be wrong?

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Charge Recombination at Surface Defects: Defects can trap charge carriers, leading to recombination [5]. Solution: Apply interface engineering to create well-defined, strongly bonded interfaces, which improve charge transfer [41] [39].

- Reverse Reaction: The produced hydrogen and oxygen can recombine back into water on the catalyst surface, especially in a one-pot system without proper separation [37]. Solution: Use sacrificial reagents (e.g., triethanolamine) to consume the holes (or oxygen), thereby suppressing the reverse reaction and stabilizing hydrogen production [37] [39].

- Photocorrosion or Catalyst Instability: The semiconductor itself may degrade under illumination [42]. Solution: Utilize more stable oxide semiconductors or protect the core catalyst with a stable shell layer.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the selectivity for a specific product in photocatalytic CO₂ reduction (e.g., CO vs. CH₄)?

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Unoptimized Reaction Pathway: The catalyst surface may not favor the desired reaction intermediates. Solution: Use interface engineering to manipulate interfacial interactions, which can orchestrate thermodynamics and kinetics to enhance selectivity [41]. For example, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) can be designed to induce preferential adsorption and activation of CO₂, favoring specific products [39].

- Insufficient Redox Potential: The retained electrons and holes may not have sufficient energy to drive the desired multi-electron reaction. Solution: Implement an S-scheme heterojunction, which is specifically designed to preserve charge carriers with the strongest redox potentials, enhancing the ability to drive challenging reactions like CO₂ reduction to hydrocarbons [8] [38] [5].

FAQ 4: What are the critical parameters to monitor in a standard photocatalytic experiment?

- Key Parameters:

- Light Source & Intensity: Use a calibrated solar simulator or Xe lamp; intensity directly affects charge carrier generation [37] [42].

- Catalyst Loading: Excessive loading causes light scattering and reduces penetration, decreasing efficiency [42].

- Solution pH: Affects the surface charge of the catalyst and the adsorption of reactants [42].

- Sacrificial Reagent Concentration: Essential for consuming unwanted holes and boosting the target reduction reaction [37] [39].

- Temperature: Moderate temperatures can enhance reaction kinetics, but extremes may degrade the catalyst [42].

Performance Data and Protocols