Flux Synthesis of Metastable Inorganic Compounds: Accelerating Discovery for Advanced Materials and Biomedicine

This article explores flux synthesis, a powerful method for discovering metastable inorganic compounds that are inaccessible through traditional high-temperature solid-state reactions.

Flux Synthesis of Metastable Inorganic Compounds: Accelerating Discovery for Advanced Materials and Biomedicine

Abstract

This article explores flux synthesis, a powerful method for discovering metastable inorganic compounds that are inaccessible through traditional high-temperature solid-state reactions. We cover the foundational principles of using molten salt fluxes as reactive media to kinetically trap intermediates and novel phases at moderate temperatures. The discussion extends to cutting-edge methodological advances, including in situ characterization and autonomous laboratories, which are drastically accelerating synthesis workflows. A dedicated analysis of troubleshooting common failure modes, such as sluggish kinetics and precursor volatility, provides a practical guide for optimization. Finally, we examine how computational predictions and machine learning are being validated against experimental results, creating a synergistic loop for targeted materials design. This integrated approach holds significant promise for the rapid development of new functional materials, including those with applications in drug discovery and therapy.

Unlocking Metastability: The Core Principles of Flux Synthesis

Metastable materials—kinetically trapped phases with positive free energy above the equilibrium state—represent a frontier of materials science with profound implications for next-generation technologies. These phases often exhibit superior properties compared to their stable counterparts, offering opportunities for innovation across fields including photocatalysis, photovoltaics, ion conductors, pharmaceuticals, and advanced steels. The synthesis and stabilization of these materials challenge the traditional thermodynamic paradigm, requiring sophisticated approaches like flux synthesis to navigate the energy landscape between kinetic trapping and thermodynamic stability.

Large-scale data-mining studies of inorganic crystalline materials reveal that approximately 50.5% of all known inorganic crystalline phases are metastable, with a median metastability of 15 meV/atom and a 90th percentile at 67 meV/atom. The probability distribution of metastability versus frequency follows an approximately exponential decrease, indicating that while most metastable phases exist relatively close to stability, a significant number occupy higher-energy states [1].

Quantifying the Thermodynamic Scale of Metastability

Chemical Influences on Metastable Energy Windows

The accessible thermodynamic range of crystalline metastability exhibits strong dependence on chemical composition, particularly the strength of cohesive energy within different chemical systems. Analysis of group V, VI, and VII chemistries reveals consistent trends based on anionic character and position in the periodic table.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Scale of Metastability by Chemistry Class [1]

| Chemistry Class | Representative Elements | Median Cohesive Energy | Median Metastability (meV/atom) | 90th Percentile Metastability (meV/atom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrides | N | Strongest | Highest in class | Highest in class |

| Oxides | O | Strong | ~20 | ~85 |

| Fluorides | F | Moderate-Strong | ~18 | ~75 |

| Other Group VI | S, Se, Te | Moderate | ~15 | ~60 |

| Group VII | Cl, Br, I | Weaker | ~12 | ~45 |

The data indicates that stronger cohesive energies, particularly found in oxides, fluorides, and nitrides, enable greater accessible crystalline metastability. This relationship stems from the ability of stronger bonding to stabilize higher-energy atomic arrangements, thereby resisting transformation to the ground state. Nitrides exhibit the highest energy scale of metastability in their respective groups, followed by oxides and fluorides [1].

Flux Synthesis: A Pathway to Metastable Phases

Hydroflux Synthesis Methodology

Hydroflux synthesis represents an advanced crystal growth technique that combines elements of flux-based and hydrothermal methods to access metastable phase spaces. This approach creates unique reaction environments distinct from either water or alkali hydroxide individually, enabling the formation of metastable phases at lower temperatures (typically 180-250°C) where kinetics can dominate over thermodynamics [2].

The fundamental principle underlying hydroflux synthesis involves creating a dynamic equilibrium between hydroxide ([OH]⁻) and hydronium (H₃O⁺) or alkali (A⁺) species in a roughly equimolar solution of water and alkali hydroxide within a sealed reaction vessel. These species form temperature- and concentration-dependent complexes with introduced reagents, leading to the precipitation of novel metastable phases that cannot be accessed through conventional high-temperature solid-state synthesis [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hydroflux Synthesis [2]

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Alkali Hydroxides (AOH) | KOH•xH₂O (Fisher Chemical, 86.6%); CsOH•xH₂O (Sigma-Aldrich, 90.0%) | Creates basic hydroflux environment; provides alkali cations for structure formation |

| Copper(II) Oxide (CuO) | Thermo Scientific, 99.995% | Source of magnetic Cu²⁺ ions for magnetic sublattices |

| Tellurium Dioxide (TeO₂) | ACROS Organics, 99%+ | Source of tellurium with modifiable oxidation states (Te⁴⁺, Te⁶⁺) |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Fisher Chemical, 30% aqueous solution | Oxidizing agent to modify tellurium oxidation state; influences yield and phase purity |

| Deionized Water | 18 MΩ resistance | Solvent component; participates in hydroxide equilibrium |

| Teflon-lined Autoclave | 22 mL capacity | Sealed reaction vessel for maintaining pressure and temperature |

Experimental Protocol: Hydroflux Synthesis of Novel Tellurate Oxide-Hydroxides

Objective: Single crystal synthesis of novel alkali tellurate oxide-hydroxides via hydroflux approach for quantum materials research.

Materials Preparation:

- Combine powder reagents CuO and TeO₂ in 1:10 molar ratio with total quantity of 11 mmol

- Add alkali hydroxides (KOH•xH₂O or CsOH•xH₂O) in specified molar ratios

- Incorporate 3mL of 0%, 10%, or 30% aqueous H₂O₂ solution added last and dropwise to minimize sudden O₂ gas formation [2]

Reaction Conditions:

- Vessel: 22 mL capacity teflon-lined autoclave

- Temperature: 200°C

- Duration: 2 days in low-temperature oven

- Quench method: Benchtop cooling to room temperature [2]

Product Isolation:

- Rinse synthesized crystals with 18 MΩ deionized H₂O

- Filter using vacuum funnel

- Characterize via single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) at 213(2) K using Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) [2]

Phase-Specific Conditions:

- CsTeO₃(OH): Highest yield with 30% H₂O₂ solution:CsOH = 10:1 molar ratio; forms as white needles or spherical needle aggregates

- KCu₂Te₃O₈(OH): Forms pure phase in 0% H₂O₂ solution:KOH = 10:1; crystallizes as small blue shard clusters; no Cs incorporation observed even in CsOH-containing solutions

- Cs₂Cu₃Te₂O₁₀: Forms under varied conditions (0-30% H₂O₂ solution:CsOH = 5:1 to 7:1); appears as square-shaped green crystal clusters [2]

Structural and Magnetic Characterization of Novel Metastable Phases

Phase Structures and Properties

The hydroflux synthesis approach has enabled the discovery and characterization of several novel metastable phases with distinct structural and magnetic characteristics:

CsTeO₃(OH) represents a new member of the ATeO₃(OH) series (A = alkali metal) and is nonmagnetic. This phase demonstrates the ability of hydroflux methods to stabilize hydrated oxide frameworks that might be inaccessible through conventional synthesis [2].

KCu₂Te₃O₈(OH) contains magnetic Cu-Te sublattices arranged in a three-dimensional structure. Magnetic characterization reveals several magnetic ordering transitions at T = 6.8 K, 21 ± 3 K, and 63 ± 5 K, demonstrating the complex magnetic behavior accessible through metastable phase synthesis [2].

Cs₂Cu₃Te₂O₁₀ features two-dimensional planes of Cu²⁺ trimers and Te⁶⁺ dimers separated by disordered Cs⁺ layers. Despite the presence of magnetic copper ions, this phase remains paramagnetic down to T = 2 K, illustrating how dimensional reduction in metastable phases can suppress long-range magnetic order [2].

Magnetic Characterization Protocol

Measurement Conditions:

- Instrument: Quantum Design Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS3)

- Temperature range: 2-300 K

- Applied field: 0.1 T with and without field cooling

- Sample preparation: Powderized single crystals [2]

Data Collection:

- Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility under specified conditions

- Isothermal magnetization measurements at T = 2, 10, 50, and 300 K across a range of magnetic fields

- Analysis of ordering transitions, susceptibility behavior, and field-dependent responses [2]

Discussion: Remnant Metastability and Synthesis Design Principles

The concept of "remnant metastability" provides a crucial framework for understanding which metastable phases can be successfully synthesized. This principle proposes that observable metastable crystalline phases are generally remnants of thermodynamic conditions where they were once the lowest free-energy phase [1]. This insight guides synthetic design toward identifying and replicating those specific thermodynamic conditions—whether through pressure, temperature, chemical potential, or compositional gradients—that temporarily stabilize the target phase.

Flux synthesis methods, particularly hydroflux approaches, excel at creating these transient thermodynamic environments through several key factors:

- Hydroxide concentration: Controls dissolution and reprecipitation equilibria

- Precursor solubility: Influences supersaturation conditions and nucleation pathways

- Oxidizing power: Modifies metal oxidation states and coordination environments

- Cation selection: Affects structural dimensionality and interlayer spacing [2]

The enhanced metastability accessible through stronger cohesive energies in oxides, fluorides, and nitrides suggests targeted synthetic opportunities in these chemical systems. The empirical observation of higher metastability thresholds in these materials indicates greater synthetic flexibility and potentially more robust kinetic trapping of desired metastable structures [1].

Flux-mediated synthesis represents a powerful methodology for accessing metastable inorganic compounds with unique structural and magnetic properties. The continuing development of hydroflux and related flux techniques enables exploration of complex phase spaces where kinetic control can overcome thermodynamic preferences, opening avenues to materials with enhanced or novel functionalities.

The quantitative understanding of metastability energy scales across different chemical systems provides essential guidance for prioritizing synthetic targets and conditions. Particularly promising directions include further exploitation of the relationship between cohesive energy and accessible metastability, refinement of oxidizing conditions to control metal valence states, and dimensional control through cation selection in low-temperature flux environments.

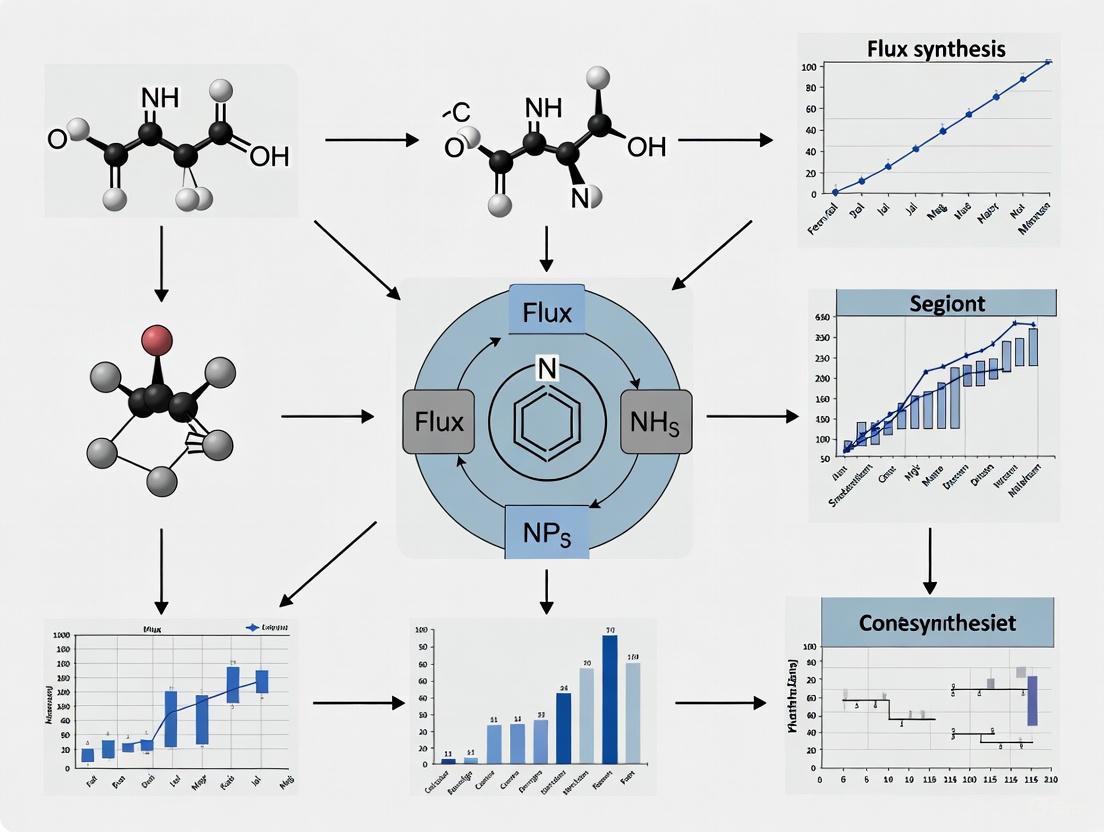

Diagram 1: Hydroflux Synthesis Workflow for Metastable Phases

Diagram 2: Cohesive Energy Enables Metastability

Application Notes

Flux synthesis, utilizing molten salts as a reactive medium, is a powerful technique for discovering and growing single crystals of metastable inorganic compounds that are inaccessible through traditional solid-state methods [3]. The molten flux acts as a high-temperature solvent, facilitating ion diffusion and providing a liquid environment that can lower reaction temperatures and stabilize intermediate phases [3]. This paradigm enables the rapid exploration of reaction and composition space, as demonstrated by the identification of four new ternary sulfides in a matter of hours via in situ X-ray diffraction studies [3]. The chemistry of the flux itself is a critical parameter; for instance, increasing the sulfur content in a reactive salt flux alters the allowable crystalline building blocks, directly influencing which metastable phases form [3]. This method provides an essential experimental complement to computational materials prediction efforts.

Quantitative Data from Flux Synthesis Studies

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research into flux-mediated crystal growth of metastable inorganic compounds.

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Data from Metastable Crystal Growth Studies

| Parameter | Value / Description | Context and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| New Compounds Identified | 4 ternary sulfides [3] | Discovered from reactive salt fluxes using in situ diffraction. |

| Reaction Time | A few hours [3] | The speed of discovery and revelation of ex situ synthesis routes. |

| O₂ Reaction Rate (k₁ at -10 °C) | 3780 ± 180 M⁻¹s⁻¹[cite [4]] | Rapid, irreversible formation of a dioxygen intermediate in a model system. |

| Peroxo Conversion Rate (k₂ at -10 °C) | 417 ± 3.2 M⁻¹s⁻¹[cite [4]] | Slower conversion of the dioxygen intermediate to a peroxo-bridged species. |

| Peroxo O-O Stretch (νo-o) | 819 cm⁻¹[cite [4]] | Isotopically sensitive vibration confirming a peroxo species formation. |

| Manganese-Peroxo Stretch (νMn-O) | 611 cm⁻¹[cite [4]] | Vibrational frequency consistent with a Mn-peroxo bond. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol:In SituX-ray Diffraction of Reactive Salt Flux Synthesis

This protocol outlines the procedure for observing the formation of metastable intermediates and new crystalline compounds in a reactive salt flux environment using in situ X-ray diffraction, based on the work of Shoemaker et al. [3].

Objective: To identify and characterize transient phases and new compounds formed during reactions in a molten salt flux.

Materials:

- High-temperature reaction stage compatible with X-ray diffraction.

- X-ray diffractometer (e.g., with a high-intensity source and rapid detector).

- Precursor salts or powders for the target inorganic compounds.

- Flux material (e.g., alkali metal polychalcogenides like K₂Sₓ or Cs₂Sₓ for sulfide growth).

- Inert atmosphere containers (glovebox, Schlenk line) to prevent oxide formation.

- Capillaries or sample holders suitable for high-temperature and potentially corrosive environments.

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Weigh out the precursor reactants and the flux material in an inert atmosphere glovebox. The flux should typically be in significant molar excess (e.g., 10-20:1 flux-to-precursor ratio) to act as an effective solvent.

- Sample Loading: Load the homogeneous mixture of precursors and flux into the appropriate capillary or sample holder for the in situ diffraction stage. Seal the container to maintain an inert atmosphere during transfer.

- Stage Setup: Mount the sample onto the high-temperature stage of the diffractometer. Ensure proper alignment for the X-ray beam.

- Data Collection Program: Program the diffractometer and furnace to perform a coordinated experiment: a. Begin collecting diffraction patterns at room temperature. b. Initiate a temperature ramp to melt the flux (e.g., 200-500 °C, depending on the flux). c. Collect sequential diffraction patterns (with exposure times of a few minutes) continuously or at set intervals throughout the heating, isothermal hold, and cooling phases.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the time- and temperature-resolved diffraction patterns to identify the appearance, transformation, and disappearance of crystalline phases. This allows for the construction of a reaction pathway and the identification of metastable intermediates.

Protocol: Synthesis and Crystallization of a Peroxo-Bridged Metal Complex from Solution

This protocol details the low-temperature synthesis and crystallization of a metastable binuclear Mn(III)-peroxo complex, {[Mnᴵᴵᴵ(SMe₂N₄(6-Me-DPEN))]₂(trans–μ–1,2–O₂)}²⁺, as a model for oxygen-derived intermediate isolation [4].

Objective: To prepare and isolate a peroxo-bridged metal complex single crystal for structural and spectroscopic characterization.

Materials:

- Precursor complex: Mnᴵᴵ(SMe₂N₄(6-Me-DPEN)) (1) [4].

- Anhydrous, degassed solvents (e.g., propionitrile, Et₂O).

- Schlenk line or glovebox for oxygen-free manipulations.

- Dry ice/acetone bath (-80 °C).

- O₂ gas cylinder (including ¹⁸O₂ for isotopic labeling studies).

- Concentrated H₂SO₄.

- Silica gel for filtration.

- Aqueous KMnO₄ solution for H₂O₂ detection assay.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Under an inert atmosphere (glovebox), prepare a cold (-80 °C) propionitrile solution of the Mn(II) precursor complex (1).

- O₂ Exposure: Open the cooled flask to a pure O₂ atmosphere or gently bubble O₂ through the cold solution for approximately two minutes. Observe the color change from light yellow to dark green, indicating the formation of the peroxo-bridged species.

- Crystallization: Layer the dark green solution with a pre-cooled (-80 °C) non-polar solvent such as diethyl ether. Allow the diffusion to proceed slowly at low temperature (-80 °C) to yield X-ray quality crystals.

- Hydrogen Peroxide Detection (Assay): a. Protonate an aliquot of the dark green peroxo solution with a minimal amount of concentrated H₂SO₄. b. Pass the resulting mixture through a small silica plug. c. Add the eluate to a stirring aqueous solution of KMnO₄ of known concentration. d. Monitor the decrease in absorbance at 550 nm as KMnO₄ is reduced by H₂O₂. Calculate the amount of H₂O₂ released, which should be approximately 0.5 equivalents per Mn ion [4].

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Flux Synthesis & Characterization

Reaction Pathway for Metal-Peroxo Intermediate Formation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Flux Synthesis and Metastable Intermediate Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive Salt Fluxes | High-temperature solvent for crystal growth; can participate in reactions as a reactant [3]. | Examples: K₂Sₓ, Cs₂Sₓ for sulfides; low melting point; reactive. |

| Mn(II) Precursor Complexes | Starting material for modeling metal-peroxo formation relevant to biological processes [4]. | Coordinatively unsaturated; thiolate-ligated for spectroscopic handles. |

| Anhydrous Solvents | Medium for low-temperature synthesis and crystallization of air-sensitive intermediates [4]. | e.g., Propionitrile, MeCN; rigorously degassed and dried. |

| Inert Atmosphere Equipment | Protection of air- and moisture-sensitive compounds and fluxes during preparation [4]. | Glovebox; Schlenk line. |

| In Situ XRD Capability | Real-time monitoring of solid, liquid flux, and recrystallization processes to identify intermediates [3]. | High-temperature stage; rapid data collection. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Kinetic analysis of rapid reactions, such as O₂ binding, at low temperatures [4]. | Cryogenic capability; diode array detector. |

In the pursuit of novel functional materials, the most thermodynamically stable phase is not always the one with the most desirable properties for a given application. Kinetic trapping, the process of arresting a system in a metastable state during its journey toward thermodynamic equilibrium, provides a powerful pathway to access these high-value phases. This approach is particularly transformative in the field of flux synthesis metastable inorganic compounds, where the goal is to deliberately bypass stable crystalline forms to discover materials with enhanced electronic, catalytic, or magnetic properties. The controlled formation of a kinetically trapped structure requires a sophisticated understanding of the energy landscapes governing molecular and atomic rearrangements. By selecting specific process conditions—primarily deposition or synthesis temperature—the rate of transition to a more stable structure can be rendered slower than the speed at which the metastable structure grows. This article details the fundamental principles and practical protocols for leveraging kinetic trapping to expand the library of functional inorganic materials.

Theoretical Foundations of Kinetic Trapping

Energy Landscapes and Transition States

At its core, kinetic trapping is a phenomenon governed by the topography of an energy landscape. A system is considered kinetically trapped when it resides in a metastable free energy minimum, separated from the global minimum by a significant energy barrier. The stability of this trapped state is not determined by its depth, but by the height of the surrounding barriers, which govern the transition rates to more stable configurations [5]. According to transition state theory, the rate constant ( k ) for a transition from a metastable state to a more stable state can be described by the Arrhenius equation:

[ k = \nu \exp\left(-\frac{Ea}{kB T}\right) ]

where ( \nu ) is the attempt frequency, ( Ea ) is the activation energy barrier, ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, and ( T ) is the absolute temperature. The probability of kinetic trapping increases when the energy barrier ( Ea ) is high relative to the available thermal energy ( kB T ). In self-assembly processes, this often occurs when interparticle bonds are excessively strong, which, while stabilizing the final equilibrium state, also frustrates the dynamics of reorganization, leading to the formation of disordered, arrested structures [6].

The Role of Moderate Temperature

Temperature is the most critical experimental knob for controlling kinetics. A moderate temperature window is essential for successful kinetic trapping [5]:

- Lower Bound: The temperature must be high enough to provide sufficient thermal energy for desired processes, such as surface diffusion and the initial stages of aggregation, to occur on a practical time scale.

- Upper Bound: The temperature must be low enough to suppress the rate of the undesired phase transition (e.g., molecular reorientation or crystalline rearrangement) to a negligible level.

Operating within this window allows the growth of the metastable phase to outpace its conversion to the thermodynamically stable phase.

Diffusion and Trapping Cooperation

Traditional views often cast diffusion and trapping as competing processes. However, advanced modeling reveals that in the presence of a concentration or occupancy gradient, they can act cooperatively. In polycrystalline materials, for instance, higher grain boundary trap-binding energy (( E{gb} )) increases hydrogen occupancy along boundaries. This increased occupancy, in turn, creates a steeper chemical potential gradient, which can surprisingly enhance the flux of hydrogen along the grain boundaries. The decisive factor for material retention at these sites, however, remains the grain boundary diffusivity (( D{gb} )) [7]. This principle can be extended to molecular systems, where targeted diffusion pathways can be used to funnel material toward specific metastable configurations.

Case Study: Kinetic Trapping of TCNE on Cu(111)

The adsorption of tetracyanoethylene (TCNE) on a Cu(111) surface serves as a quintessential model for demonstrating controlled kinetic trapping and its profound impact on material properties [5].

TCNE on Cu(111) exhibits two distinct phases with dramatically different electronic properties:

- Metastable Phase: Features flat-lying molecules (L1 geometry).

- Stable Phase: Features upright-standing molecules (S1, S3, S4 geometries). The transition from the flat-lying to the upright-standing configuration induces a massive work function increase of approximately 3 eV [5]. This change stems from altered charge transfer and interface dipole moments at the metal-organic interface. As the interface layer dictates key electronic properties, the ability to kinetically trap the flat-lying structure is critical for applications in organic electronics, such as transistors and spintronic devices [5].

Table 1: Key Properties of TCNE on Cu(111) Phases

| Property | Flat-Lying (L1) Phase | Upright-Standing Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Orientation | Parallel to substrate | Perpendicular to substrate |

| Thermodynamic Stability | Metastable | Stable (at high dosage) |

| Work Function Change | Lower work function | ~3 eV increase |

| Target for Kinetic Trapping | Yes | No |

Energetics and Transition Barriers

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal the energetic landscape. The upright-standing geometries (S1-S4) are over 0.5 eV higher in energy (less stable) than the flat-lying L1 geometry for an isolated molecule [5]. However, at higher surface coverages, intermolecular interactions make the upright-standing phase thermodynamically favorable.

The key to kinetic trapping is the high energy barrier for the reorientation process (L1 → S1) compared to the barrier for diffusion. The calculated activation barrier for the reorientation of an individual TCNE molecule is significantly higher than that for its diffusion across the surface [5]. This difference in activation energies is the fundamental parameter that allows for the selection of a temperature where diffusion (enabling ordered growth) is active, but reorientation (leading to the thermodynamically stable phase) is virtually frozen.

Temperature-Dependent Rate Analysis

Using harmonic transition state theory, the temperature-dependent rates for diffusion (( k{\text{diff}} )) and reorientation (( k{\text{reorient}} )) can be calculated [5]. The goal is to identify a temperature ( T ) that satisfies the condition:

[ k{\text{diff}}(T) \gg k{\text{reorient}}(T) ]

This ensures that molecules can efficiently diffuse to form ordered islands of the metastable flat-lying phase before any molecule has a chance to reorient. Based on these rates, a targeted temperature window for successful kinetic trapping of flat-lying TCNE can be proposed [5].

Diagram 1: Kinetic trapping pathway for TCNE on Cu(111). The high barrier for reorientation from L1 to S1 allows the metastable L1 phase to be trapped.

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Trapping

Protocol: Kinetic Trapping of a Metastable Molecular Phase on a Metal Surface

This protocol is adapted from the computational study of TCNE on Cu(111) and provides a general framework for the targeted growth of metastable surface phases [5].

1. Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Crystal Substrate | Provides a well-defined, clean surface for epitaxial growth. | Cu(111), Ag(111), etc. |

| Organic Molecular Source | The functional molecule to be deposited. | Tetracyanoethylene (TCNE), HATCN, etc. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) System | Creates a contamination-free environment for preparation and analysis. | Base pressure < 1×10⁻¹⁰ mbar. |

| Evaporation Source | Provides controlled thermal evaporation of the molecular source. | Knudsen Cell (K-Cell). |

| In-Situ Characterization Tools | Monitors film growth and structure in real-time. | Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). |

2. Procedure

Step 1: Substrate Preparation

- Load the single-crystal substrate (e.g., Cu(111)) into the UHV system.

- Clean the substrate surface through repeated cycles of sputtering (e.g., with Ar⁺ ions) and thermal annealing (e.g., to 500-600°C) until surface contaminants are below the detection limit of XPS and a sharp LEED pattern is observed.

Step 2: Pre-Deposition Calibration & Calculations

- Calculate the theoretical energy barriers for the target process (diffusion) and the competing process (reorientation) using Density Functional Theory (DFT) and nudged elastic band (NEB) methods [5].

- Using transition state theory, plot the rate constants for diffusion (( k{\text{diff}} )) and reorientation (( k{\text{reorient}} )) as a function of temperature to identify the optimal deposition temperature window [5].

Step 3: Temperature-Controlled Deposition

- Pre-condition the molecular evaporation source to ensure a stable, precise flux.

- Set the substrate to the calculated moderate temperature within the identified window (e.g., a temperature where ( k{\text{diff}} ) is orders of magnitude larger than ( k{\text{reorient}} )) [5].

- Begin deposition, controlling the dosage carefully. Monitor the growth in real-time with LEED to confirm the formation of the desired metastable phase.

Step 4: Post-Growth Validation

- After deposition, without changing the substrate temperature, use LEED to confirm the long-range order of the metastable phase.

- Use XPS to characterize the electronic structure of the interface (e.g., work function, core-level shifts) and verify it matches the properties of the target metastable phase.

- If possible, cool the sample to cryogenic temperatures before performing any further analysis that might induce a phase transition.

3. Analysis and Validation

- Primary Output: A thin film of the target material in a metastable structural phase.

- Key Validation Metrics:

- LEED Pattern: Should match the simulated pattern for the metastable structure, not the thermodynamically stable one.

- Work Function: Measured via XPS or Kelvin Probe, should correspond to the value predicted for the metastable phase (e.g., a lower work function for flat-lying TCNE).

- Thermal Stability: Annealing the film at a higher temperature should trigger the transition to the thermodynamically stable phase, confirming the kinetically trapped nature of the as-grown film.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for the kinetic trapping of a surface phase.

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Computational tools are indispensable for guiding experimental efforts in kinetic trapping, as they can predict key parameters like energy barriers before any synthesis is attempted.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Nudged Elastic Band (NEB)

- Function: DFT is used to calculate the stable adsorption geometries (energy minima) of a molecule on a surface. The NEB method is then used to find the minimum energy path (MEP) and the transition state (saddle point) between two minima [5].

- Protocol:

- Geometry Optimization: Fully relax the initial (e.g., flat-lying L1) and final (e.g., upright-standing S1) states on the surface.

- Image Initialization: Generate a series of intermediate "images" between the initial and final states.

- NEB Calculation: Run an NEB calculation to relax these images onto the MEP. The image with the highest energy is the transition state.

- Barrier Extraction: The energy difference between the transition state and the initial state is the activation energy barrier (( E_a )).

Full-Field Modeling for Microstructure-Dependent Trapping

In complex microstructures like polycrystalline metals, kinetic trapping can occur at defects. Full-field models are used to simulate these scenarios.

- Model Setup: A representative volume element (RVE) of a polycrystalline microstructure is generated, often using the phase-field method [7].

- Governing Equations: The model implements a fully kinetic formulation for mass transport, combining diffusion with trapping. The trapping kinetics at grain boundaries can be described by a flux directed toward the center of trapping sites, with parameters for trap-binding energy (( E{gb} )) and grain boundary diffusivity (( D{gb} )) [7].

- Application: These models can simulate processes like hydrogen uptake and permeation, revealing how ( E{gb} ) and ( D{gb} ) cooperate to control the distribution and flux of a trapped species [7].

Kinetic trapping represents a paradigm shift in the synthesis of metastable inorganic compounds, moving from serendipitous discovery to rational design. The core principle—manipulating temperature and diffusion to navigate energy landscapes—provides a universal strategy for accessing materials with properties unattainable from equilibrium phases. As demonstrated by the TCNE on Cu(111) model system, success hinges on the precise identification of a temperature window that selectively enhances desired kinetics (diffusion) while suppressing deleterious ones (reorganization). The integration of advanced computational modeling, particularly DFT and full-field simulations, is crucial for predicting these parameters and accelerating the development of next-generation materials for electronics, energy storage, and catalysis. By mastering the kinetics of synthesis, researchers can systematically expand the realm of the possible in materials science.

The pursuit of metastable inorganic compounds represents a frontier in solid-state chemistry and materials science, offering access to novel properties and functionalities not found in thermodynamically stable phases. Within this research paradigm, flux synthesis has emerged as a powerful experimental platform for discovering and growing single crystals of metastable materials, particularly in the context of chalcogenide compounds. This methodology utilizes low-melting point solvents, or "fluxes," which facilitate enhanced diffusion of reactants at moderate temperatures, thereby enabling the crystallization of kinetically stabilized phases that are inaccessible through conventional solid-state synthesis [3]. The research community has recognized that rapid shifts in energy, technological, and environmental demands necessitate focused and efficient expansion of the library of functional inorganic compounds, requiring discovery and optimization paradigms that can rapidly reveal all possible compounds within a given reaction and composition space [3].

Chalcogenides, particularly those based on copper and tin, provide paradigmatic examples for studying metastability due to their complex structural chemistry and diverse electronic properties. These materials demonstrate remarkable versatility, with applications spanning from thermoelectric power generation and photovoltaics to catalysis and neuromorphic engineering [8]. Particularly intriguing are the electron-deficient copper chalcogenides that demonstrate metallic p-type conductivity and Pauli paramagnetism, which distinguishes them from semiconducting counterparts built from the same elements [8]. This unique combination of properties—directional bonding and low coordination numbers typical for covalent phases, coupled with metallic-type conductivity—places them in the category of "covalent metals," a classification that summarizes their distinctive structural and physical properties.

Experimental Platform: Flux Synthesis Methodologies

Fundamental Principles of Flux Synthesis

Flux synthesis operates on the principle of using a low-melting solvent medium to enhance atomic diffusion and facilitate crystal growth at temperatures significantly below those required for solid-state reactions. This approach is particularly advantageous for accessing metastable polymorphs and reactive intermediates that would otherwise decompose at higher temperatures. The flux medium serves multiple functions: it acts as a solvent for starting materials, enhances reaction kinetics through liquid-phase diffusion, and provides a microenvironment that can template specific crystal structures. By carefully controlling parameters such as cooling rate, flux composition, and reaction temperature, researchers can steer reactions toward desired metastable products rather than their thermodynamic counterparts.

The in situ X-ray diffraction studies of platforms for metastable inorganic crystal growth have demonstrated that this approach can identify new ternary sulfides from reactive salt fluxes in a matter of hours, simultaneously revealing routes for ex situ synthesis and crystal growth [3]. Changing the flux chemistry, for example by increasing sulfur content, permits comparison of the allowable crystalline building blocks in each reaction space, providing insights into the structural preferences under different chemical environments [3]. The speed and structural information inherent to in situ synthesis methods provide an experimental complement to computational efforts to predict new compounds and uncover routes to targeted materials by design.

Synthesis Protocols for Copper Chalcogenides

Alkali Polychalcogenide Flux Method

Protocol Objective: Synthesis of ternary copper sulfides and selenides using alkali polychalcogenide fluxes.

Step 1: Reagent Preparation

- Prepare alkali polychalcogenide flux by reacting alkali metals (Na, K) with chalcogens (S, Se) in liquid ammonia. Alternatively, generate polychalcogenide fluxes in situ by using metal chalcogenides (Na₂Q, K₂Q, where Q = S or Se) in combination with elemental chalcogen [8].

- Prepare copper source: Use elemental copper foil/powder or pre-formed binary copper chalcogenides (Cu₂S, CuS, Cu₂Se, etc.).

Step 2: Reaction Assembly

- In an argon-filled glovebox (O₂ & H₂O < 0.1 ppm), weigh and mix reagents in appropriate stoichiometric ratios.

- Load mixture into a fused silica (quartz) or borosilicate (Pyrex) ampule based on reaction temperature requirements (quartz for >500°C, Pyrex for <500°C).

- Seal ampule under vacuum (<10⁻² Torr) using an oxygen-methane torch.

Step 3: Thermal Reaction Profile

- Place sealed ampule in a programmable muffle furnace.

- Heat from room temperature to 350–1100°C at a rate of 200°C/hour [8].

- Dwell at maximum temperature for 6–48 hours to ensure complete homogenization.

- Cool slowly to 200°C at a rate of 2–5°C/hour to promote crystal growth.

- Finally, cool to room temperature at 100°C/hour.

Step 4: Product Isolation

- Carefully open ampule in a fume hood.

- Remove excess flux by washing with deionized water and polar organic solvents (DMF, DMSO, or ethanol).

- Filter through a fine porosity fritted funnel and dry under vacuum.

Alternative Flux Chemistry Methods

A. Hydroxide-Halide Flux Method

- Application: Synthesis of charge-unbalanced phases such as Na₃Cu₄Se₄ (isostructural with K₃Cu₄Se₄) [8].

- Special Requirements: Highly reactive flux incompatible with glass ampules or alumina crucibles.

- Procedure:

- Use mixed alkali hydroxides-sodium iodide flux in a glassy carbon boat.

- Perform reaction under nitrogen flow in a tube furnace.

- Similar thermal profile to polychalcogenide method but with lower maximum temperatures (typically 350–600°C).

B. Thiocyanate Flux Method

- Application: Synthesis of phases such as BaCu₂S₂ and CsCu₅S₃ [8].

- Procedure:

- Use potassium or cesium thiocyanate as flux.

- Two-step process where thiocyanate acts primarily as a solvent.

- For CsCu₅S₃, cesium thiocyanate flux assists the formation and incorporates cesium into the structure.

C. Boron-Chalcogen Mixture (BCM) Method

- Application: Synthesis of copper chalcogenides with elements of high oxygen affinity (e.g., NaCuUS₃) [8].

- Procedure:

- React metal oxides (e.g., U₃O₈) with copper, sodium carbonate, boron, and sulfur.

- Boron binds oxygen in the system, while sulfur reacts with metals to form chalcogenides.

- Reaction performed in sealed silica tubes at 500–900°C.

D. Hydrothermal Synthesis

- Application: Alternative route for selenides such as CsCu₄Se₃ [8].

- Procedure:

- React mixture of K₂Se₄, Cu, and CsCl with minimal water (0.5 mL) in sealed quartz ampoule.

- Moderate temperature range (120–170°C).

- Significantly lower temperature than conventional flux methods.

Workflow Visualization: Flux Synthesis for Metastable Chalcogenides

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Chalcogenide Synthesis

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Copper Chalcogenide Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali Metals | Sodium (Na), Potassium (K) | Formation of alkali polychalcogenide fluxes; charge compensation in crystal structures | Strict exclusion of air and moisture; use in glovebox |

| Chalcogen Sources | Sulfur (S), Selenium (Se), Tellurium (Te) | Framework formation in chalcogenide crystals; tuning of electronic properties | Toxic (especially Se, Te); adequate ventilation required |

| Copper Precursors | Elemental copper, Cu₂S, CuS, CuO, CuI | Primary metal source for chalcogenide framework formation | Oxide precursors require stronger reducing conditions |

| Flux Media | Na₂Sₓ, K₂Se₄, NaOH-NaI, KSCN | Low-melting solvents enabling crystal growth at moderate temperatures | Moisture-sensitive; some are highly corrosive (hydroxide fluxes) |

| Reaction Vessels | Quartz ampules, Pyrex tubes, Glassy carbon crucibles | Contain reaction mixtures at high temperatures; withstand pressure buildup | Thermal stress management; pressure considerations for sealed tubes |

| Oxygen Scavengers | Boron, Carbon | Create reducing atmosphere; essential for BCM method with oxide precursors | Stoichiometric control crucial to avoid side products |

Structural and Electronic Features of Copper Chalcogenides

Classification by Electronic Structure

Copper chalcogenides can be fundamentally divided into two major groups based on their electronic characteristics:

Formally Charge-Balanced Compounds: These phases adhere to conventional oxidation state formalism, typically exhibiting semiconducting behavior with band gaps that enable applications in photovoltaics and electronic devices.

Formally Charge-Unbalanced (Electron-Deficient) Compounds: These materials demonstrate a deviation from oxidation state formalism, where the oxidation state of Cu is consistently +1, while mixed +1/+2 states have been ruled out [8]. This results in a deficit of formal negative charge in both binary (CuS, CuSe, Cu₃Se₂) and ternary (NaCu₄S₃, NaCu₄Se₃) phases [8]. The holes originating from a mismatch between the number of molecular orbitals and available valence electrons become delocalized over structural units, leading to metallic p-type conductivity—a hallmark of electron-deficient covalent metals.

Structural Building Blocks

The compositions and structures of many copper chalcogenides can be rationalized based on two primary two-dimensional nets with specific topologies:

Honeycomb Net Topology: Characterized by hexagonal arrangements of atoms that create porous layers with six-membered rings, often facilitating ion transport or incorporation of additional species.

Square Lattice Net Topology: Featuring four-connected nodes forming grid-like layers that provide different electronic delocalization pathways and coordination environments.

These fundamental building blocks can be arranged into more complex structures through various stacking sequences, though only a limited number of these hypothetical arrangements have been realized in actual materials, indicating significant opportunity for future discovery [8].

Quantitative Data Compilation: Copper Chalcogenide Phases

Table 2: Structural and Electronic Properties of Selected Copper Chalcogenides

| Compound | Crystal System | Structural Features | Conductivity Type | Magnetic Properties | Synthesis Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuS (Covellite) | Hexagonal | Layered structure with CuS and Cu₂S₂ layers; S-S bonds | Metallic p-type | Pauli paramagnetism | Binary direct synthesis |

| CuSe (Klockmannite) | Hexagonal | Similar layered structure to covellite | Metallic p-type | Pauli paramagnetism | Binary direct synthesis |

| NaCu₄S₃ | Orthorhombic | Electron-deficient 2D copper-sulfide slabs | Metallic p-type | Pauli paramagnetism | Polychalcogenide flux |

| NaCu₄Se₄ | Tetragonal | Charge-balanced composition | Semiconducting | Diamagnetic | Polychalcogenide flux |

| Na₃Cu₄Se₄ | Tetragonal | Electron-deficient; formally charge-unbalanced | Metallic p-type | Pauli paramagnetism | Hydroxide-halide flux |

| CsCu₄Se₃ | Monoclinic | Ternary analogue with cesium | Metallic p-type | Pauli paramagnetism | Hydrothermal or BCM |

Characterization Techniques and Property Evaluation

Structural Characterization Protocol

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

- Equipment: Powder X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å)

- Parameters: 2θ range 5–90°, step size 0.01–0.02°, collection time 1–2 seconds per step

- Data Analysis:

- Rietveld refinement for phase identification and quantification

- Lattice parameter determination

- In situ high-temperature XRD for monitoring phase transitions

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction

- Crystal Selection: Under optical microscope, select well-formed crystal of appropriate size (0.1–0.3 mm)

- Data Collection: Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at various temperatures (100–300 K)

- Structure Solution: Direct methods followed by full-matrix least-squares refinement against F²

Electronic Properties Measurement Protocol

Electrical Transport Measurements

- Sample Preparation: Dense pellets for polycrystalline materials; single crystals for anisotropic measurements

- Electrode Application: Four-probe configuration with gold wires and silver epoxy contacts

- Measurement Conditions: Temperature range 2–400 K using closed-cycle refrigerator system

- Data Collection:

- Resistivity as function of temperature (ρ vs. T)

- Hall coefficient measurements for carrier concentration and mobility

- Seebeck coefficient for thermoelectric characterization

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurements

- Technique: Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID) magnetometry

- Parameters: Temperature range 2–400 K, applied fields 0–7 T

- Data Analysis:

- Curie-Weiss fitting for paramagnetic components

- Identification of Pauli paramagnetism in metallic systems

- Detection of possible magnetic ordering at low temperatures

The study of copper and tin chalcogenides through flux synthesis methodologies provides a paradigmatic example of how metastable inorganic compounds can be discovered and optimized for targeted functionalities. The experimental platform described herein, combining innovative flux chemistry with advanced characterization techniques, offers a robust pathway for expanding the library of functional inorganic materials. The unique electronic characteristics of electron-deficient copper chalcogenides—particularly their metallic conductivity arising from delocalized holes in covalent frameworks—present intriguing opportunities for fundamental research and technological applications alike.

Future research directions in this field should focus on several key areas, including the development of novel flux systems with tailored chemical properties, the integration of computational prediction with experimental synthesis to accelerate discovery, the exploration of previously inaccessible composition spaces, and the precise control of defect structures to engineer specific electronic and thermal transport properties. As the demand for advanced functional materials continues to grow across energy, electronics, and sensing applications, the paradigm of flux-assisted metastable materials synthesis will undoubtedly play an increasingly vital role in materials discovery and design.

Advanced Workflows: From In Situ Analysis to Autonomous Discovery

In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction (XRD) has emerged as a powerful technique for elucidating real-time reaction pathways in materials synthesis, providing unparalleled insights into the formation mechanisms of metastable inorganic compounds. This Application Note details the protocols and methodologies for employing in situ synchrotron XRD, specifically within the context of flux synthesis research. The intense, bright beams generated by synchrotron sources enable time-resolved monitoring of dynamic crystallization processes, intermediate phase formation, and structural evolution under non-ambient conditions. By capturing transient states and non-equilibrium intermediates, this technique is instrumental for tailoring synthesis protocols to target and isolate metastable phases with unique functional properties.

The fundamental advantage of in situ/operando synchrotron X-ray techniques over ex situ characterization lies in their ability to probe dynamic processes as they occur. Key benefits include [9]:

- Instant Probing: Measurements instantly probe reactions at specific locations within a sample, providing higher reliability and precision for data analysis.

- Continuous Monitoring: Operando measurements continuously monitor electrochemical, physical, or chemical processes on a single sample under operating conditions, eliminating the need for multiple sample preparations and providing near real-time information.

- Capturing Transients: This method allows the investigation of non-equilibrium or fast-transient processes, enabling the detection of short-lived intermediate states or species that cannot be captured by ex situ characterizations [9].

- Preserving Sample Integrity: In situ approaches remove the possibility of contamination, relaxation, or irreversible changes of highly reactive samples during preparation, handling, and transfer for ex situ measurements [9].

For the study of flux synthesis, where reaction pathways are often dictated by kinetic control and the formation of metastable intermediates, these capabilities are transformative. They allow researchers to move beyond post-synthesis analysis and actively observe the sequence of phase formations that lead to a final metastable product.

Application Notes: Resolving Complex Reaction Pathways

In situ synchrotron XRD is uniquely suited to tackle the complexities of flux synthesis. The following applications highlight its capabilities:

Monitoring Crystallization Pathways and Intermediates

The structural evolution during the synthesis of functional materials can be directly monitored to uncover complex crystallization pathways. For instance, in the synthesis of the luminescent complex [Tb(bipy)2(NO3)3], the combination of in situ luminescence measurements with synchrotron-based XRD revealed a reaction pathway dependent on parameters like ligand-to-metal molar ratios, involving the formation of a distinct reaction intermediate [10]. Identifying such intermediates is a critical step towards developing targeted synthesis protocols for metastable compounds.

Probing Phase Transformations under Non-Ambient Conditions

Custom-designed sample environments allow for the application of various physical fields during diffraction experiments. For example, a custom sample chamber developed for PETRA III at DESY enables XRD experiments at temperatures ranging from 100 K to 1250 K combined with the application of electric fields [11]. This is particularly relevant for studying polar materials and phase transitions driven by external stimuli, which are common in the search for new functional inorganic compounds.

Investigating Complex Systems with Multi-Modal Analysis

The complexity of reactions in multi-component systems often necessitates a combination of complementary characterization techniques. Synchrotron facilities allow for the combination of XRD with techniques like X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray pair distribution function (PDF) analysis [9]. This multi-modal approach provides correlated information on long-range order, local coordination, and electronic structure, offering a more complete picture of the reaction mechanism.

Table 1: In Situ Synchrotron XRD Techniques for Reaction Monitoring

| Technique | Key Application in Flux Synthesis | Information Gained | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Resolved XRD | Tracking phase evolution as a function of time and temperature. | Crystallization kinetics, sequence of phase formation, stability ranges. | [9] [10] |

| XRD under Electric Field | Studying field-induced phase transitions in polar materials. | Ferroelectric, piezo- and pyroelectric behavior under applied bias. | [11] |

| XRD + PDF Analysis | Investigating materials with short-range order or amorphous intermediates. | Local structure, bond distances, and coordination environments. | [9] |

| Serial X-ray Crystallography | Interrogating individual micro-crystallites from a reaction mixture. | Structure solution from microcrystals, assessing sample homogeneity. | [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Successful in situ experiments require careful planning, from cell design to data collection. The following protocol provides a generalized framework for studying flux synthesis reactions.

Protocol: Time-Resolved Study of a Flux Crystallization Reaction

Objective: To capture the real-time phase evolution and identify transient intermediates during the cooling of a high-temperature inorganic flux reaction.

Materials and Equipment:

- Synchrotron Beamline: Equipped for high-energy X-ray diffraction (transmission geometry) with a fast-readout 2D detector.

- In Situ Furnace: A high-temperature capable furnace (up to at least 1600°C) with low-absorption X-ray windows (e.g., Kapton, amorphous carbon).

- Sample Environment: A custom-designed capillary cell or a reaction holder compatible with the furnace and corrosive flux materials.

- Precursors and Flux: High-purity metal oxides/carbonates and the selected flux medium (e.g., molten salts like chlorides, hydroxides).

Procedure:

Pre-experiment Planning (ex situ):

- Conduct preliminary ex situ experiments to identify approximate reaction temperatures and phase formation sequences. These results provide critical references for designing the in situ experiment and for subsequent data analysis [9].

- Prepare the precursor mixture by thoroughly grinding the reactant powders with the flux material in the desired molar ratio.

In Situ Cell Assembly and Loading:

- Load the precursor mixture into a capillary sample holder (e.g., a thin-walled quartz or sapphire capillary) that is chemically resistant to the flux at high temperatures.

- Assemble the cell within the in situ furnace, ensuring the X-ray beam path passes through the sample and the windows. The cell should be designed for easy assembly/disassembly and highly reproducible positioning [9].

- For reactions releasing gases, ensure the cell design can accommodate pressure changes.

Beamline Setup and Alignment:

- Align the sample in the X-ray beam. Use a beam shutter to minimize unnecessary radiation exposure to the sample until data collection begins, thereby reducing potential beam damage [9].

- Calibrate the detector distance and orientation using a standard reference material (e.g., CeO₂).

- Set up the data acquisition software to collect sequential diffraction patterns with an exposure time short enough to capture the kinetics of the reaction (e.g., 1-10 seconds per pattern).

Data Acquisition:

- Initiate the programmed temperature protocol (e.g., ramp to a homogenization temperature, hold, then cool at a controlled rate).

- Simultaneously, begin the automated collection of diffraction patterns throughout the entire thermal cycle.

- Monitor the data in real-time to identify the onset of crystallization and phase changes.

Post-experiment Data Processing and Analysis:

- Convert the series of 2D diffraction images into 1D diffractograms (intensity vs. 2θ).

- Perform phase identification on each diffractogram in the time series using profile fitting and database matching (e.g., ICDD PDF-4+).

- Track the integrated intensity of characteristic diffraction peaks for each identified phase to plot concentration profiles as a function of time and temperature.

- Use multivariate analysis or parametric refinement to identify and model the presence of any transient, low-crystallinity intermediates.

Critical Considerations for Protocol Design

- Window Materials: The material covering the X-ray windows must be chemically and electrochemically stable, impermeable to oxygen and moisture, and stiff enough to apply uniform pressure. Kapton film is widely used for hard X-rays, but its softness can be a limitation. Beryllium, while ideal for transmission, poses safety hazards and can oxidize [9].

- Background Signal: Cell components in the X-ray beam path (windows, current collectors, etc.) will generate background signals. It is crucial to design the cell for high reproducibility so that background signals from an empty cell can be precisely measured and subtracted during data analysis [9].

- Beam Damage: The high-intensity synchrotron beam can alter the sample. Intermittent probing (using a shutter) or moving the sample region is recommended to reduce the total radiation dose unless continuous data collection is essential [9].

Technical Specifications & Equipment

The core of this methodology is a specialized sample environment that allows for the application of extreme conditions while permitting X-ray access.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Situ Synchrotron XRD

| Item / Component | Function / Relevance | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Sample Chamber | Provides a controlled vacuum or inert atmosphere environment for applying temperature and electric fields during XRD. | Modular vacuum vessel with a temperature range of 100-1250 K and electrical capabilities for 1 V - 5 kV [11]. |

| Hemispherical Domes | Provides extensive angular freedom for X-ray access, crucial for single-crystal studies and measuring oblique reflections. | Exchangeable domes made from polymers like PEEK, PS, or PC, which differ in X-ray absorption and scattering characteristics [11]. |

| In Situ Electrochemical Cell | Allows for operando XRD studies during battery charge/discharge cycles, relevant for studying ion intercalation in metastable compounds. | AMPIX cell, capillary cells; designed with X-ray transparent windows and minimal background interference [9]. |

| High-Temperature Heater | Enables studies of synthesis and phase stability at the high temperatures typical of flux growth. | UHV button heater with LN2 cooling base, capable of short-term peak power of 60 W for temperatures up to 1750 K [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Visualization & Data Analysis

Effective visualization of the experimental workflow and subsequent data analysis is critical for interpreting complex reaction pathways.

Experimental Workflow for In Situ Reaction Monitoring

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a typical in situ synchrotron XRD experiment, from preparation to final analysis.

Data Interpretation Workflow

After data collection, the raw diffraction patterns must be processed and interpreted to reconstruct the chemical "reactome" – the network of phases and transformations.

For complex systems with large, multi-variable datasets, robust statistical frameworks like the High-Throughput Experimentation Analyzer (HiTEA) can be employed. HiTEA uses random forests, Z-score analysis, and principal component analysis to deduce statistically significant correlations between reaction components (e.g., flux composition, temperature) and outcomes (e.g., formation of a metastable phase), thereby elucidating the hidden "reactome" from the data [12].

Application Notes

The A-Lab represents a transformative approach in inorganic materials science, functioning as a closed-loop autonomous laboratory that integrates artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and active learning to accelerate the discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials, including metastable phases highly relevant to flux synthesis research [13] [14]. This system is designed to bridge the critical gap between computational prediction and experimental realization of materials [13].

Over an initial 17 days of continuous operation, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 target compounds, achieving a 71% success rate [15] [13]. Subsequent analysis indicated this rate could be improved to 78% with minor enhancements to its decision-making algorithms and computational techniques [13]. The lab operates around the clock, capable of testing between 100 to 200 samples per day, which represents a 50 to 100-fold increase in throughput compared to human researchers [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of the A-Lab

| Performance Metric | Result | Details/Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Operation Duration | 17 days | Continuous, 24/7 operation [13] |

| Target Compounds | 58 | Primarily oxides and phosphates [15] [13] |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 compounds | 71% initial success rate [15] [13] |

| Potential Success Rate | 78% | With improved algorithms and computations [13] |

| Daily Throughput | 100-200 samples | 50-100x faster than human researchers [14] |

| Elements Spanned | 33 | Demonstrates broad chemical scope [13] |

| Structural Prototypes | 41 | Indicates diversity of synthesized structures [13] |

Relevance to Metastable Inorganic Compounds and Flux Synthesis

The A-Lab's mission directly intersects with the challenges of synthesizing metastable inorganic compounds. These materials, which can possess unique and useful properties not found in stable phases, are often difficult or impossible to isolate using conventional solid-state methods [16] [17]. The A-Lab's AI-driven, adaptive experimentation is particularly suited to navigating complex energy landscapes to identify synthesis pathways for these metastable targets [13].

While the A-Lab's published work primarily used solid-state powder reactions [13], its underlying principles are highly applicable to flux synthesis metastable inorganic compounds research. Flux methods, including hydroflux (a hybrid of hydrothermal and flux techniques), utilize a solvent or melt to facilitate diffusion and reaction at lower temperatures, often favoring the formation of kinetically stabilized metastable phases over thermodynamically stable products [16] [2]. The A-Lab's active learning algorithms, which are designed to efficiently explore complex reaction parameter spaces, can be adapted to optimize flux-related variables such as:

- Flux chemistry and composition [2]

- Hydroxide concentration and pH in hydrofluxes [2]

- Temperature and reaction time [3]

- Precursor solubility and oxidizing agent concentration [2]

This capability enables the exploration of novel phase spaces that are inaccessible through traditional high-temperature solid-state routes [2].

Experimental Protocols

Autonomous Workflow for Synthesis and Characterization

The A-Lab's end-to-end autonomous workflow can be conceptualized in several key stages, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Target Material Selection

- Objective: Identify novel, air-stable inorganic compounds predicted to be synthesizable.

- Procedure:

- Screen large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from sources like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind [13].

- Select target materials predicted to be on or near (<10 meV per atom) the thermodynamic convex hull [13].

- Filter candidates to exclude compounds containing radioactive, rare, or toxic elements, and verify novelty against databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [15] [13].

- Cross-reference with handbooks and other resources to finalize a list of targets with readily available precursors [15].

AI-Driven Synthesis Recipe Generation

- Objective: Propose initial synthesis recipes and conditions for the selected targets.

- Procedure:

- Literature-Inspired Recipes: Use natural-language processing (NLP) models trained on vast historical synthesis literature to assess target "similarity" and propose precursor sets and reactions based on analogous known materials [13].

- Temperature Prediction: Employ machine learning (ML) models trained on literature heating data to predict effective synthesis temperatures based on precursor properties and thermodynamic driving forces [15] [13].

- Active Learning Initiation: If initial recipes fail, the ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm takes over. This algorithm [15] [13]:

- Integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed outcomes.

- Prioritizes precursor sets that avoid unwanted reactions.

- Seeks intermediates with a large thermodynamic driving force to form the final target.

- Leverages a growing database of pairwise reactions observed in the lab's own experiments to reduce the search space.

Robotic Synthesis and Characterization Execution

- Objective: Physically perform the synthesis and characterize the resulting product.

- Synthesis Procedure:

- Preparation: Robotic arms dispense and mix precise quantities of precursor powders from a library of ~200 materials [14].

- Heating: The mixture is transferred to an alumina crucible and loaded into one of four (or more) box furnaces for heating according to the proposed thermal profile [15] [13].

- Cooling: The sample is allowed to cool after the reaction [15].

- Characterization Procedure:

AI Phase Analysis and Active Learning

- Objective: Determine the success of the synthesis and plan subsequent actions.

- Procedure:

- Phase Identification: A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based model analyzes the XRD pattern to identify the crystalline phases present and estimate their weight fractions [15].

- Validation: An automated Rietveld refinement approach validates the phase identification [15] [13].

- Decision Point: If the target material is obtained as the majority phase (>50% yield), the process is deemed successful. If not, the results are fed back to the active learning algorithm (ARROWS3), which proposes a new set of experimental conditions, and the loop repeats [13].

Protocol Adaptation for Flux Synthesis Exploration

The general A-Lab workflow can be adapted for flux synthesis, a critical method for discovering metastable phases. The diagram below outlines a proposed autonomous flux synthesis workflow.

- Key Modifications for Flux Synthesis:

- Precursor and Flux Handling:

- Reaction Vessels:

- Utilize sealed autoclaves with Teflon liners to contain hydroflux or other flux reactions at moderate temperatures (e.g., 180-250°C) [2].

- Optimization Parameters:

- Program the active learning AI to key experimental variables critical to flux synthesis, such as [2]:

- Hydroflux composition (H2O-to-AOH molar ratio).

- Concentration of oxidizing agents (e.g., H2O2).

- Precursor solubility.

- Heating temperature and duration.

- Cooling rate.

- Program the active learning AI to key experimental variables critical to flux synthesis, such as [2]:

- Characterization:

- Integrate Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD) for detailed structural determination of crystals grown from flux [2].

- Include characterization of functional properties, such as magnetic susceptibility measurements using a Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS3) for magnetic metastable phases [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Autonomous Synthesis and Flux Growth

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powder Library | Starting materials for solid-state and flux reactions. | ~200 different powders, including common oxides (e.g., CuO, TeO2) [2] [14]. |

| Alkali Hydroxides (AOH) | Key component of hydrofluxes; creates a basic reaction environment. | KOH·xH2O, CsOH·xH2O; concentration and A+ cation size influence product formation [2]. |

| Aqueous Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) | Oxidizing agent in flux synthesis; influences product composition and purity. | Typically used at 0-30% concentration; affects the yield of specific phases [2]. |

| Robotic Arms (3) | Core automation hardware for transferring samples and labware between stations [15] [14]. | |

| Box Furnaces (4-8) | For heating solid-state reactions; programmable with different thermal profiles [15] [13]. | |

| Teflon-lined Autoclaves | Sealed vessels for performing hydroflux and hydrothermal syntheses at moderate temperatures. | 22 mL capacity; heated in ovens at ~200°C [2]. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | Primary tool for phase identification and quantification of synthesis products [15] [13]. | |

| Single-Crystal X-ray Diffractometer | For determining the atomic-level crystal structure of single crystals grown from flux. | Essential for characterizing novel metastable phases [2]. |

Reactive flux synthesis is an advanced crystal growth technique that utilizes molten salts as a solvent medium to facilitate the dissolution and reaction of precursor materials at moderate temperatures. Unlike inert fluxes, reactive fluxes actively participate in the chemical reaction, serving as a source of specific anions that become incorporated into the final crystalline product. This methodology has emerged as a powerful platform for discovering and growing metastable inorganic compounds that are inaccessible through conventional solid-state synthesis routes. The fundamental principle involves designing flux chemistry to control the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of crystal formation, thereby directing phase selection toward targeted materials.

Within the context of metastable inorganic compounds research, reactive flux design provides a critical pathway to explore energy landscapes beyond the global thermodynamic minimum. By tuning flux composition, researchers can manipulate reaction pathways to favor the crystallization of metastable phases with unique properties. The selection of specific polysulfide salts (e.g., K₂S₃ vs. K₂S₅) represents a strategic variable that governs the oxidizing power, viscosity, and solubility characteristics of the flux system, ultimately determining which crystalline phases nucleate and grow from the reaction medium.

Fundamental Principles of Flux Chemistry Tuning

Chemical Potential Control through Flux Composition

The chemistry of the flux medium directly controls the chemical potential of reactive species in solution, thereby influencing which crystalline phases become energetically favorable. In polysulfide flux systems, the sulfur chemical potential varies significantly with the sulfur chain length in the salt. Longer polysulfide chains (as in K₂S₅) create a higher sulfur chemical potential compared to shorter chains (as in K₂S₃), promoting the formation of phases with higher sulfur content or more oxidized metal centers. This principle was demonstrated in studies where "changing the flux chemistry, here accomplished by increasing sulfur content, permits comparison of the allowable crystalline building blocks in each reaction space" [3].

The free energy landscape of crystal formation is profoundly affected by flux composition. While computational methods can predict thermodynamic stability, experimental flux synthesis accesses metastable intermediates that may form rapidly under kinetic control. The flux medium lowers energy barriers for the formation of these metastable phases by providing a liquid environment that facilitates diffusion and reversible binding interactions. Through careful flux design, researchers can effectively "traverse" the free energy landscape to isolate intermediates that would be inaccessible in solid-state reactions.

Kinetic Control over Nucleation and Growth

Beyond thermodynamic considerations, flux chemistry governs the kinetic factors of crystal growth, including dissolution rates of precursors, diffusion coefficients of soluble species, and nucleation barriers. Viscosity variations between different flux compositions affect diffusion rates, while the coordinating ability of the flux ions influences the dehydration and assembly of molecular precursors into extended structures. These kinetic factors often determine whether a reaction pathway leads to a metastable or thermodynamic product.

The oxidative power of the flux represents another crucial variable that can be tuned through salt selection. In hydroflux systems (combining water with alkali hydroxides), the addition of oxidizing agents like H₂O₂ significantly impacts product formation. For example, in the synthesis of CsTeO₃(OH), "increasing the solution concentration of H₂O₂ led to a higher yield and greater purity" [2]. This demonstrates how intentional modification of the redox potential directs phase selection by controlling metal oxidation states.

Quantitative Data on Flux-Dependent Phase Formation

Table 1: Phase Selection as a Function of Flux Chemistry in Sulfide Systems

| Target System | Flux Composition | Sulfur Content | Resulting Phases | Crystal Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ternary Sulfides | K₂S₃-based flux | Lower | Phases with reduced sulfur content | Shorter chain building units |

| Ternary Sulfides | K₂S₅-based flux | Higher | Four new ternary sulfides [3] | Different building blocks |

| CsTeO₃(OH) | CsOH/H₂O with 0% H₂O₂ | Low oxidizing power | Lower yield | White needles/Spherical aggregates |

| CsTeO₃(OH) | CsOH/H₂O with 30% H₂O₂ | High oxidizing power | Higher yield and purity [2] | White needles/Spherical aggregates |

Table 2: Hydroflux Synthesis Conditions and Resulting Magnetic Properties

| Compound | Flux Composition | Crystal System | Magnetic Properties | Synthesis Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsTeO₃(OH) | CsOH + H₂O + H₂O₂ (varying %) | Triclinic [2] | Nonmagnetic | 200°C, 2 days |

| KCu₂Te₃O₈(OH) | KOH + H₂O (0% H₂O₂) | Monoclinic [2] | Magnetic transitions at 6.8K, 21K, 63K | 200°C, 2 days |

| Cs₂Cu₃Te₂O₁₀ | CsOH + H₂O + H₂O₂ (varying %) | Monoclinic [2] | Paramagnetic down to 2K | 200°C, 2 days |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Situ X-ray Diffraction of Polysulfide Flux Reactions

This protocol enables real-time observation of crystal formation pathways in reactive flux systems, allowing identification of metastable intermediates and optimization of reaction parameters [3].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Precursor Salts: High-purity metal precursors (e.g., CuO, TeO₂)

- Polysulfide Flux: K₂S₃ and K₂S₅ of >99% purity

- Inert Atmosphere: Argon gas glovebox (<0.1 ppm O₂/H₂O)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Combine precursor materials (11 mmol total) with flux medium (10:1 flux:precursor molar ratio) in an alumina crucible within an argon glovebox.

- Reaction Setup: Transfer the crucible to a custom in situ X-ray diffraction system with a high-temperature stage and environmental control.

- Thermal Program: Heat from room temperature to 200°C at 5°C/min, then hold for 2-48 hours depending on target phase.

- Data Collection: Continuously collect X-ray diffraction patterns (5-60° 2θ, 30s/pattern) throughout the heating and isothermal stages.

- Phase Identification: Analyze diffraction patterns in real-time to identify crystalline phases and track phase evolution.

- Process Termination: Quench the reaction once the target phase dominates the diffraction pattern.

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for establishing time-temperature-transformation diagrams for metastable phases and identifying optimal processing windows for target compounds.

Protocol: Hydroflux Synthesis with Oxidizing Agent Tuning

This procedure demonstrates how controlled oxidation potential in hydroflux systems directs the formation of complex oxide-hydroxide phases with specific magnetic properties [2].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Metal Oxides: CuO (99.995%), TeO₂ (99%+)

- Hydroxide Sources: KOH·xH₂O (86.6%), CsOH·xH₂O (90.0%)

- Oxidizing Solutions: 10%, 30% H₂O₂ aqueous solutions

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Combine CuO and TeO₂ powders in a 1:10 molar ratio (11 mmol total) in a Teflon-lined autoclave.

- Flux Preparation: Add alkali hydroxides (KOH or CsOH) to achieve molar ratios specific to target phase:

- For CsTeO₃(OH): CsOH:H₂O₂ solution = 10:1

- For KCu₂Te₃O₈(OH): KOH alone or KOH:CsOH mixture

- Oxidizer Addition: Add H₂O₂ solution (0%, 10%, or 30%) dropwise to minimize O₂ gas formation.

- Reaction: Seal the autoclave and heat to 200°C for 2 days in a laboratory oven.

- Product Recovery: Quench to room temperature, rinse with 18 MΩ deionized H₂O, and filter using a vacuum funnel.

- Characterization: Analyze products by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, SEM-EDS, and magnetic susceptibility measurements.

Applications: This method enables exploration of novel phase spaces containing unusual bonding geometries relevant to quantum materials synthesis, particularly for compounds with magnetic interactions.

Protocol: Bismuth Flux Synthesis for Intermetallic Crystals

This protocol describes the use of bismuth as a reactive flux for growing millimeter-sized single crystals of intermetallic phases, enabling direction-dependent physical property studies [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Metal Precursors: High-purity transition metals and rare-earth elements

- Flux Medium: Bismuth metal (99.999%)

- Crucibles: Alumina or silica crucibles

Procedure:

- Charge Preparation: Combine reactant metals with bismuth flux in atomic ratios typically ranging from 1:9 to 1:20 (metal:Bi).

- Loading: Seal the mixture in an appropriate crucible (alumina or silica) under inert atmosphere.