Evaluating Coordination Number Determination Methods: Accuracy, Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

Accurately determining atomic coordination numbers is fundamental to understanding structure-property relationships in chemistry and materials science, with profound implications for drug development and biomedicine.

Evaluating Coordination Number Determination Methods: Accuracy, Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurately determining atomic coordination numbers is fundamental to understanding structure-property relationships in chemistry and materials science, with profound implications for drug development and biomedicine. This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of modern coordination number determination methods, from foundational geometric approaches to advanced techniques based on electron density and machine learning. We explore the principles, applications, and limitations of methods including Voronoi-Dirichlet partitioning, topological coordination analysis, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, and continuous symmetry measures. By comparing accuracy across different chemical environments and material systems, this review serves as an essential guide for researchers selecting appropriate characterization strategies for complex molecular systems, single-atom catalysts, and metalloproteins relevant to pharmaceutical development.

Fundamental Concepts and Challenges in Coordination Number Determination

The coordination number serves as a fundamental descriptor in materials science, chemistry, and physics, quantifying how many nearest neighbors surround a central atom or ion. While conceptually simple as a counting rule, practical determination reveals significant complexity, with multiple experimental and computational methodologies yielding divergent values from the same underlying structure. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of leading coordination number determination methods, examining their underlying principles, accuracy limitations, and appropriate application domains. By synthesizing experimental benchmarks and computational validations, we provide researchers with a structured framework for selecting methodologies that align with their accuracy requirements and system characteristics, particularly focusing on challenges in liquid systems and nanomaterial characterization where traditional counting rules prove inadequate.

The coordination number represents a cornerstone structural parameter across scientific disciplines, informing understanding of packing efficiency, chemical bonding, and physical properties in systems ranging from simple crystals to complex amorphous materials and biological assemblies. Traditional definitions rely on radial cutoff distances from the central atom, yet this simplistic approach falters for noncrystalline systems where bond length distributions overlap and lack clear minima. The practical determination of coordination numbers reveals substantial methodological divergence, where identical systems yield different numerical values depending on the experimental or computational technique employed.

This methodological variability stems from fundamental differences in what physical property each technique actually probes. X-ray and neutron scattering methods measure pairwise correlation functions, while spectroscopic techniques probe electronic environments, and computational approaches rely on geometric or electronic structure analysis. Consequently, the "true" coordination number becomes method-dependent, necessitating a nuanced understanding of each technique's inherent assumptions, limitations, and accuracy boundaries. This guide systematically compares these approaches within a rigorous accuracy assessment framework, providing experimental validation data and practical implementation protocols to guide method selection for specific research applications.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Experimental Determination Methods

Scattering Techniques

Scattering methods derive coordination numbers through integration of the radial distribution function (RDF), which describes particle density as a function of distance from a reference atom. The coordination number between species α and β is calculated as:

Experimental Protocol for Neutron Scattering of Liquid Argon:

- Sample Preparation: Utilize high-purity argon (≥99.99%) sealed in sample cells with neutron-transparent windows (e.g., aluminum, vanadium). Maintain temperature control (±0.1 K) using cryostat systems.

- Data Collection: Employ time-of-flight neutron diffractometers with incident wavelengths typically 0.5-2.0 Ã…. Collect data at multiple scattering angles to achieve wide Q-range (0.1 to 30 Ã…â»Â¹). Measurement duration typically 6-24 hours depending on flux and sample size.

- Data Processing: Subtract background scattering and container contributions. Apply multiple scattering corrections and normalize to absolute units using standard samples.

- Coordination Number Calculation: Fourier transform structure factor S(Q) to obtain g(r). For liquid argon at 85 K, integrate first coordination shell from Rmin = 3.10 Ã… to Rmax = 5.03 Ã…, where R_max corresponds to the first minimum in g(r) [1]. Use number density Ïâ‚€ = 0.02125 atoms/ų for calculation.

Accuracy Considerations: The upper integration limit R* significantly impacts calculated coordination numbers. For liquid argon, empirical determination establishes R* = 5.03 Ã… at 85 K based on neutron scattering data [1]. Different integration methods yield coordination numbers ranging from 10.0 to 12.5 for identical datasets, highlighting methodological sensitivity.

Spectroscopic Approaches

Spectroscopic methods, particularly nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), provide complementary coordination information through measurement of parameters sensitive to local atomic environment.

NMR Experimental Protocol for Organic Molecules:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve target molecules in deuterated solvents at concentrations 10-100 mM. Add reference standards (e.g., TMS for ¹H/¹³C referencing) and ensure sample homogeneity.

- Data Collection: Acquire ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra at controlled temperature (typically 298 K) using high-field spectrometers (≥400 MHz). For scalar coupling constants, utilize 2D experiments such as HMBC (nJCH) and COSY (nJHH) with sufficient digital resolution.

- Parameter Extraction: Measure proton-carbon (nJCH) and proton-proton (nJHH) scalar coupling constants through peak analysis. Validate experimental values against DFT-calculated benchmarks to identify misassignments [2].

- Structure Determination: Utilize measured NMR parameters as constraints for 3D structure determination through molecular modeling or DFT-based structure optimization.

Computational Determination Methods

Computational approaches offer atomic-level resolution but vary in their definition of "coordination" based on geometric or electronic criteria.

Geometric-Based Protocol:

- Cutoff Method: Identify neighbors within fixed distance threshold (e.g., first minimum of RDF). Simple but fails for disordered systems with broad bond length distributions.

- Voronoi Tessellation: Partition space into polyhedral cells around each atom. Coordination number equals number of faces, providing natural neighbor definition without distance cutoffs.

- Delaunay Triangulation: Construct tetrahedral network connecting atomic centers, useful for liquid structure analysis [1].

Electronic Structure Protocol:

- Population Analysis: Calculate coordination from molecular orbital occupancy or bond order analysis (e.g., Wiberg bond indices).

- DFT Calculations: Employ functionals such as mPW1PW91 with basis sets like 6-311 g(dp) to compute NMR parameters for validation against experimental data [2].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Method Accuracy Assessment

Table 1: Coordination Number Determination Method Comparison

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Accuracy Limit | System Applicability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutron Scattering | Ensemble average | ±0.5 coordination | Liquids, amorphous materials | Integration limit sensitivity, isotopic requirements |

| X-ray Diffraction | Ensemble average | ±0.7 coordination | Crystalline solids, dense liquids | Limited light element sensitivity, radiation damage |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Atomic local environment | Coordination trends | Molecular systems, complexes | Indirect measurement, interpretation complexity |

| Voronoi Analysis | Atomic resolution | ±0.1 coordination | Computational models, packed systems | Boundary effects in low-density systems |

| Radial Distribution | Atomic resolution | ±0.3 coordination | All atomistic systems | Cutoff distance ambiguity, thermal broadening |

Table 2: Experimental Coordination Numbers for Liquid Argon (85 K) by Method

| Determination Method | Integration/Calculation Approach | Reported Coordination Number | Reference System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutron Scattering | RDF integration to R* = 5.03 Ã… | 10.0 | Yarnell et al. [1] |

| Neutron Scattering | RDF integration to first minimum | 12.5 | Mikolaj and Pings [1] |

| Voronoi Analysis | Face counting without cutoff | 13.8-14.2 | Computational models [1] |

| Theoretical Model | Barker et al. potential | 11.3 | DFT/MD simulations [1] |

| Theoretical Model | Bae potential | 12.1 | DFT/MD simulations [1] |

Temperature Dependence and System Effects

Coordination numbers exhibit significant temperature dependence, particularly in liquid systems. For liquid argon, coordination values decrease from approximately 12 near the triple point (83.81 K) to as low as 5 approaching the critical point (150.70 K) [1]. This substantial structural variation under different thermal conditions highlights the importance of reporting temperature alongside coordination number values and selecting methods appropriate for the system's thermodynamic state.

Different computational potentials yield varying coordination numbers, with the Bae potential showing results comparable to more complex, three-parameter models [1]. This sensitivity to potential selection underscores the need for careful method validation against experimental data when available.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Resources

| Research Reagent/Resource | Function in Coordination Analysis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Argon (≥99.99%) | Reference sample for scattering studies | Essential for calibration of liquid structure analysis |

| Deuterated NMR Solvents | Matrix for molecular structure determination | Enables high-resolution NMR parameter measurement |

| Neutron-Transparent Cells | Sample containment for scattering experiments | Aluminum/vanadium construction minimizes background |

| DFT Software (mPW1PW91) | Computational validation of experimental data | Benchmarking level for NMR parameter calculation [2] |

| LSH Forest Indexing | Efficient neighbor identification in large datasets | Enables analysis of datasets up to 10â· points [3] |

| TMAP Algorithm | Visualization of high-dimensional data relationships | Tree-based representation preserves neighborhood structure [3] |

| URAT1 inhibitor 9 | URAT1 inhibitor 9, MF:C20H13N3O2S2, MW:391.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antibacterial agent 150 | Antibacterial agent 150, MF:C33H45NO6, MW:551.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflow for Accurate Determination

The determination of coordination numbers extends far beyond simple atom counting, encompassing diverse methodologies with inherent strengths, limitations, and accuracy boundaries. This comparative analysis demonstrates that methodological selection significantly impacts reported coordination numbers, with variations exceeding 20% observed across techniques applied to identical systems. Scattering methods provide ensemble averages with well-characterized precision but suffer from integration limit sensitivity. Spectroscopic techniques offer local environmental insight but require careful interpretation and computational validation. Geometric computational approaches deliver atomic-resolution data but depend on definitional criteria.

For researchers pursuing accurate coordination number determination, a multi-method approach with cross-validation provides the most reliable pathway. Specifically, computational studies should validate against experimental benchmarks where available, while experimental approaches should explicitly report integration limits, temperature conditions, and methodological assumptions. The development of standardized validation datasets, such as the NMR parameter collection for organic molecules [2], enables more rigorous method benchmarking. As structural characterization advances toward increasingly complex systems, acknowledging and quantifying the methodological dependence of coordination numbers becomes essential for accurate structural interpretation and material property prediction.

Historical Evolution from Geometric to Electronic Descriptors

The evolution from geometric to electronic descriptors represents a fundamental paradigm shift in computational chemistry and materials science. This transition marks a move from describing molecular structures based solely on their spatial arrangement to characterizing them by their electronic properties, which more directly govern chemical reactivity and function. Geometric descriptors, which condense the complex spatial arrangement of atoms into simplified numerical representations or counts, provided the foundational language for early structural chemistry [4]. For decades, the coordination number (CN) stood as a cornerstone geometric descriptor, traditionally defined simply as the number of atoms in the first sphere around a central atom [4]. However, the limitations of this purely geometric perspective became increasingly apparent, particularly for complex systems like intermetallic compounds or transition metal complexes, where chemical bonding mechanisms are not always clear-cut [4]. This spurred the development of electronic descriptors, which leverage the principles of quantum mechanics to describe the electron density distribution within a molecule, offering a more direct link to a material's chemical and catalytic properties [5] [6]. This guide objectively compares the accuracy, applications, and methodological underpinnings of these two descriptor classes within the specific context of evaluating coordination number determination methods.

Comparative Analysis of Descriptor Methodologies

The following tables provide a structured comparison of the fundamental characteristics and experimental validation of geometric and electronic descriptors.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Geometric and Electronic Descriptors

| Feature | Geometric Descriptors | Electronic Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Classical geometry & graph theory [6] | Quantum mechanics & density functional theory [5] [6] |

| Primary Information | Nuclear coordinates, interatomic distances, connectivity [4] [6] | Electron density distribution, orbital energies [5] [6] |

| Key Examples | Topological Coordination Number (tCN), Voronoi-Dirichlet Polyhedra, Wiener Index [4] [6] | d-band model, Principal Component (PC) descriptors of density of states, Hirshfeld Charges, HOMO/LUMO energies [5] [6] [7] |

| Data Requirement | Crystal structure metrics (atomic coordinates) [4] | Computed electronic structure (e.g., from DFT calculations) [5] [7] |

| Interpretability | Intuitive but often lacks direct link to properties [6] | More abstract but offers direct connection to chemical activity [5] |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol and Performance Comparison

| Aspect | Geometric Descriptors | Electronic Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Experimental Validation | X-ray crystallography, comparison with crystallographic databases (e.g., CSD) [4] [7] | X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), optical spectroscopy, correlation with catalytic activity/chemisorption energy [5] [8] |

| Computational Workflow | Distance analysis (e.g., Brunner-Schwarzenbach), Voronoi tessellation, solid angle calculation [4] | Density Functional Theory (DFT) optimization, electronic structure analysis (e.g., using PCA) [5] [7] |

| Typical Workflow | Structure → Interatomic distances → Coordination number [4] | Structure → DFT Optimization → Electronic Structure Analysis → Descriptor [5] [7] |

| Handling of Dynamic/Disordered Systems | Problematic; relies on static snapshots [4] | More robust; AIMD simulations can model dynamic coordination fluctuations [8] |

| Reported Accuracy in Coordination Analysis | Can lack coordination reciprocity; may over-count neighbors (Voronoi) [4] | PCA-derived electronic descriptors show competitive accuracy in predicting chemisorption properties [5] |

Evolution of Experimental Protocols

Classic Geometric Determination Protocols

Traditional geometric approaches for determining coordination numbers rely heavily on crystallographic data. The Brunner-Schwarzenbach (BS) method is a classic protocol that identifies the first coordination sphere by locating the first significant gap in the sequence of increasing interatomic distances from a central atom [4]. A more advanced protocol involves Voronoi-Dirichlet Partitioning (VDP), which divides space into polyhedra, each containing all points closer to a given atom than to any other. The number of polyhedral faces gives the maximum coordination number, which is often refined using solid angles subtended by each face to produce a weighted, effective coordination number [4]. These methods, while powerful, face challenges such as a lack of coordination reciprocity and ambiguity in defining the exact boundary of the coordination sphere [4].

Modern Electronic Structure Analysis Protocols

Modern protocols for electronic descriptor analysis are rooted in quantum mechanical calculations. A standard workflow begins with Density Functional Theory (DFT) geometry optimization of the molecular or solid-state structure, often using functionals like B3LYP and basis sets such as 6-31G* [7]. Subsequently, the electronic structure is analyzed. One powerful protocol uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the electronic density of states (DOS) [5]. In this unsupervised machine learning approach, the complex DOS data is decomposed into principal components that capture the most significant variations. These PC scores then serve as highly accurate, interpretable descriptors for predicting properties like chemisorption strength [5]. For analyzing complex, multi-component systems like metal ions in molten salts, a correlative protocol combining X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), optical spectroscopy, and multivariate curve resolution (MCR-ALS) is employed. This protocol deconvolutes the spectral data to identify and quantify the population distribution of different coordination states coexisting in dynamic equilibrium [8].

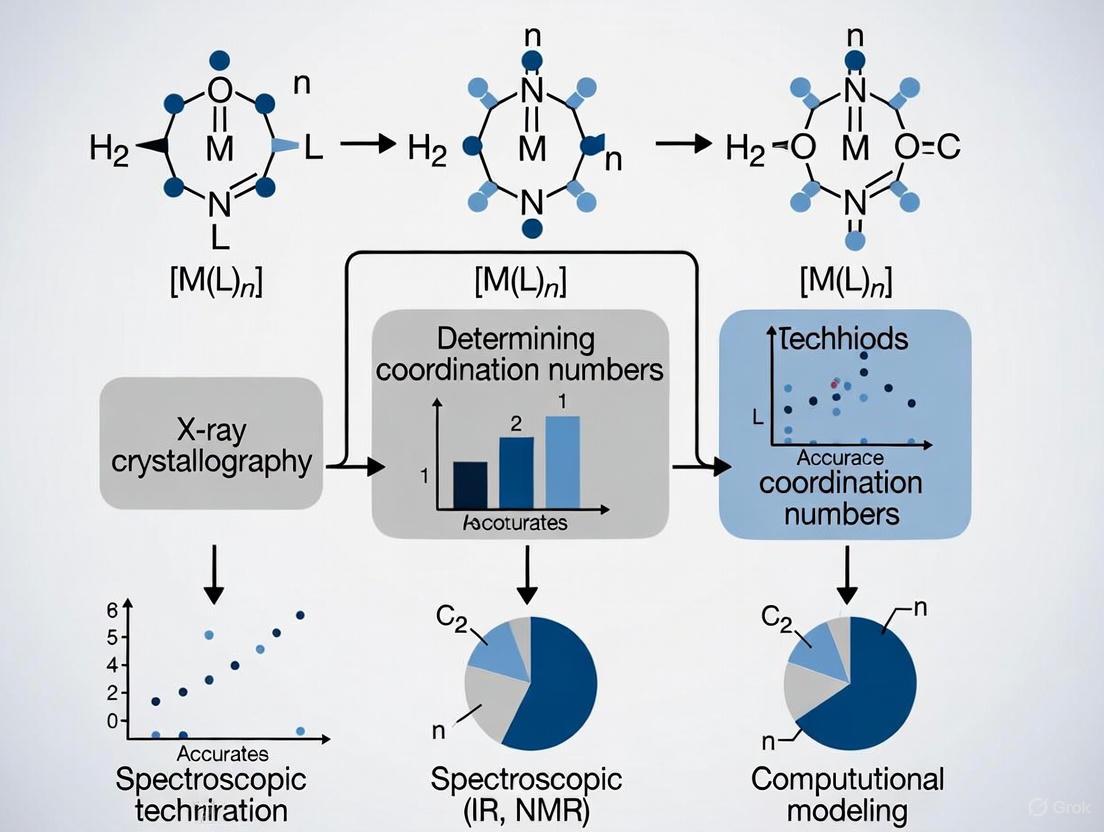

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison of geometric and electronic descriptor generation and application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Descriptor Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Descriptor Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Software Suite | Performing DFT calculations for geometry optimization and electronic property derivation [7]. |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Generating molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) and traditional 2D descriptors [9] [7]. |

| Amber | Molecular Simulation | Utilizing force field parameters (e.g., GAFF2) for molecular mechanics simulations [7]. |

| molSimplify | Open-Source Code | High-throughput generation and screening of transition metal complex structures [10]. |

| Demeter | Software Package | Processing and analyzing X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) data [8]. |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Database | Repository of experimental crystallographic data for validation and trend analysis [10] [7]. |

| pan-HCN-IN-1 | pan-HCN-IN-1, MF:C23H37N3O2, MW:387.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyk2-IN-2 | Pyk2-IN-2, MF:C27H27N7O, MW:465.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Accuracy Assessment in Coordination Number Determination

The accuracy of coordination number determination is highly context-dependent. Geometric descriptors, particularly the topological coordination number (tCN) based on the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM), offer an improvement over traditional methods by naturally accounting for different atomic sizes and providing coordination-consistent scenarios [4]. However, they still face challenges in systems with high structural disorder or dynamic fluctuation.

Electronic descriptors, particularly those derived from machine learning analysis of electronic structure, demonstrate superior accuracy for predicting chemical activity. Studies show that principal-component (PC) descriptors of the electronic density of states yield machine learning models with competitive accuracy in predicting chemisorption properties on metal alloys and oxides compared to models using established descriptors [5]. Furthermore, in complex systems like molten salts, electronic structure analysis combined with AIMD simulations is essential for accurately identifying the population distribution of coordination states that dynamically coexist, a feat difficult to achieve with static geometric methods [8].

For drug discovery applications, the choice of descriptor impacts predictive performance. A comparative study on ADME-Tox targets found that models using traditional 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors could outperform those based solely on molecular fingerprints for certain machine learning algorithms [9]. This underscores that the "best" descriptor is often task-dependent, but electronic and higher-dimensional descriptors generally provide a more chemically-grounded foundation for predicting biologically-relevant properties.

Diagram 2: Experimental protocol for electronic analysis of coordination states in complex systems like molten salts [8].

The historical evolution from geometric to electronic descriptors reflects the chemical sciences' progression from descriptive to predictive capabilities. While geometric descriptors remain invaluable for structural classification and initial analysis, their limitations in explaining and predicting chemical behavior are evident. Electronic descriptors, powered by advances in quantum mechanical computations and machine learning, provide a more fundamental and accurate link to a material's properties, from catalytic activity to speciation in complex fluids. The ongoing integration of these descriptor types, alongside sophisticated experimental validation protocols, continues to enhance the accuracy of coordination number determination and beyond, paving the way for the accelerated design of novel materials and drugs.

The coordination number (CN) is a fundamental descriptor in crystallography and materials science, condensing the complex spatial arrangement of atoms around a central atom into a single integer. Despite its conceptual simplicity, a significant challenge exists in moving beyond a purely geometric definition to one that is chemically meaningful and physically consistent. The determination of an accurate CN is often complicated by two principal factors: the requirement for coordination reciprocity and the influence of atomic size effects. This guide objectively compares the performance of established and emerging methods for CN determination, with a specific focus on how they address these two challenges, providing researchers with a framework for selecting the appropriate analytical tool.

The traditional approach of analyzing interatomic distances, such as the Brunner-Schwarzenbach method, often fails to deliver reciprocity, meaning that for the same A–B distance, atom A might be counted in the coordination sphere of B, but not vice versa. This violates physical chemistry principles, as bonding interactions are inherently pairwise symmetric [4]. Furthermore, methods based on Voronoi-Dirichlet partitioning (VDP), while providing a unique geometric CN, typically do not naturally account for differences in atomic sizes, requiring additional corrections and weighting schemes [4]. This guide evaluates methods based on their foundational principles, summarizing key differentiators in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Coordination Number Determination Methods

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Handles Coordination Reciprocity? | Accounts for Atomic Size Effects? | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-Based (e.g., Brunner-Schwarzenbach) | Identification of large gaps in interatomic distance sequences [4] | No (Often violates reciprocity) [4] | No (Purely metric) [4] | Traditional crystallographic analysis |

| Voronoi-Dirichlet Partitioning (VDP) | Geometric partitioning of space into atomic domains; atoms sharing a polyhedron face are neighbors [4] | Yes (By construction) | No (Requires empirical weighting e.g., solid angles) [4] | Intermetallic compounds, complex alloys [4] |

| Topological Coordination Number (tCN) | Analysis of electron density via QTAIM; solid angles of interatomic surfaces [4] | Yes (Includes reciprocity requirements) [4] | Yes (Naturally includes atomic electron-density decay) [4] | Quantum crystallography, intermetallic phases [4] |

| Data-Driven/Machine Learning (e.g., TOSS, GNNs) | Statistical learning from large datasets of known structures (e.g., ICSD, CSD) [11] [10] | Implicitly learned from data | Implicitly learned from data (e.g., via coordination radii) [11] | High-throughput materials screening, predicting novel complexes [11] [10] |

| Atomic Density Field | Coarse-grained field variable capturing local atomic packing [12] | Not a direct CN method (Provides a related descriptor) | Yes (Captures both neighbor count and interatomic spacing) [12] | Mesoscale modeling of defects (e.g., grain boundaries) [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

The accuracy of any CN determination method must be validated against reliable experimental or computational benchmarks. The following protocols detail key methodologies used to generate reference data in this field.

In Silico Benchmarking with Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD)

Objective: To compute reference structural properties, including coordination numbers, for phases under extreme or complex conditions where traditional experiments are challenging [13].

Workflow:

- System Setup: Construct a supercell of the crystal structure (e.g., 2000 atoms for BCC-Fe) to ensure thermodynamic stability and avoid finite-size effects [13].

- DFT Calculations: Perform AIMD simulations using software like VASP. Employ a plane-wave basis set with a defined energy cut-off (e.g., 400 eV) and the GGA for exchange-correlation energy. Use the NVT ensemble to maintain target temperature and pressure conditions [13].

- Data Collection: Run the simulation for thousands of timesteps (e.g., 8000 with a 1.0 fs timestep) to ensure proper equilibration.

- Structure Analysis: Compute the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) from the trajectory. The coordination number is derived by integrating the RDF up to the first minimum [13].

Supporting Experimental Data: This approach was crucial in resolving the structure of iron under Earth's core conditions. AIMD simulations of a 2000-atom BCC-Fe supercell at 560 GPa and ~7000 K produced a coordination number of ~11, successfully matching experimental EXAFS data that was previously ambiguous [13].

Multi-Modal Speciation in Molten Salts

Objective: To identify and quantify the population distribution of different coordination states of a metal ion (e.g., Ni(II)) in a molten salt matrix as a function of temperature and composition [14].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare molten salt mixtures (e.g., LiCl–KCl, NaCl–MgCl₂) with a low concentration (e.g., 1 wt%) of the metal salt (e.g., NiCl₂) in an inert atmosphere glovebox to prevent oxidation and moisture contamination [14].

- In Situ Spectroscopy:

- Data Deconvolution:

- Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the optical spectra to determine the number of unique coordination states.

- Apply Multivariate Curve Resolution – Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS) analysis to the XANES data to extract pure spectral components for each coordination state and their mixing fractions [14].

- Structure Identification: The extracted spectral components are assigned to specific coordination geometries (e.g., tetrahedral, octahedral) by comparing them with spectra from AIMD simulations of candidate structures [14].

Data-Driven Oxidation State and Coordination Analysis

Objective: To determine chemically intuitive oxidation states (OS) and infer coordination environments in crystal structures from large datasets, providing a validation source for CN analysis [11].

Workflow (Tsinghua Oxidation States in Solids - TOSS):

- Data Ingestion: Preprocess a large dataset of crystal structures (e.g., from the Materials Project).

- Library Building ("Digesting"): For each atomic site, analyze its local coordination environment across a range of distance tolerance parameters. This process is repeated over the entire dataset to build a library of distance distributions and coordination radii for each element pair [11].

- OS Assignment ("Practicing"): For each structure, determine the OSs by minimizing a loss function based on the Bayesian maximum a posteriori probability (MAP), using the previously built library as the prior. The algorithm seeks the most probable OS assignment that is consistent with the observed local coordination environments across the dataset [11].

- Model Training: The resulting OS-labeled data can be used to train a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) model for rapid OS prediction, achieving high accuracy (>97%) against human-curated labels [11].

Diagram 1: The TOSS workflow for data-driven oxidation state assignment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for Coordination Environment Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | A repository of experimentally determined organic and metal-organic crystal structures used for data mining and trend analysis [10]. | Curating datasets of ligands with known metal-coordination behavior to train machine learning models [10]. |

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | A software package for performing DFT calculations and AIMD simulations [13]. | Modeling the structure and coordination of phases under extreme pressures and temperatures [13]. |

| molSimplify | An open-source software for the automated generation and analysis of transition metal complexes [10]. | High-throughput in silico structure generation and screening of TMCs with realistic coordination geometries [10]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | A class of machine learning models that operate on graph-structured data, ideal for molecular structures [10]. | Predicting the coordinating atoms and denticity of a ligand directly from its SMILES string [10]. |

| Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR-ALS) | A chemometric analysis technique that deconvolutes mixed spectroscopic signals into pure components [14]. | Resolving the XANES spectra of Ni(II) in molten salts into contributions from distinct coordination states (e.g., 4-, 5-, 6-coordinate) [14]. |

| Antitubercular agent-38 | Antitubercular agent-38|Anti-TB Research Compound | Antitubercular agent-38 is a novel investigational compound for tuberculosis research. It is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| MorHap | MorHap, MF:C39H38N2O3S, MW:614.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accurate determination of coordination numbers is a non-trivial problem at the heart of materials science and chemistry. As this guide demonstrates, the choice of method directly impacts the ability to resolve the core challenges of coordination reciprocity and atomic size effects. While traditional geometric methods are computationally simple, they often fail to deliver chemically consistent results. The emerging paradigm, exemplified by the topological CN approach and data-driven machine learning models, integrates physical principles with statistical learning to provide a more robust and meaningful analysis of atomic coordination. This progression is critical for developing reliable structure-property relationships, ultimately accelerating the design of new materials and catalysts.

The Critical Distinction Between Geometric and Chemical Coordination Numbers

In the fields of crystallography, inorganic chemistry, and materials science, the term "coordination number" (CN) is a fundamental descriptor of atomic architecture. However, its interpretation varies significantly depending on the conceptual framework applied, leading to a critical distinction between geometric coordination numbers and chemical coordination numbers. The geometric coordination number is a purely structural metric derived from the immediate spatial arrangement of atoms, calculated by counting neighboring atoms within a defined radial cutoff or by analyzing the geometry of coordination polyhedra [15] [16]. In contrast, the chemical coordination number is intimately tied to bonding models, representing the number of atoms chemically bonded to the central atom, which requires an understanding of the nature and strength of the interatomic interactions [15] [16]. The International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) explicitly acknowledges this duality, stating that the coordination number of an atom in a crystalline solid "depends on the chemical bonding model used" [15] [16]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two paradigms, examining their determination methods, underlying assumptions, and applications, with a focus on evaluating the accuracy of coordination number determination methods within modern research contexts.

Comparative Analysis: Geometric vs. Chemical Coordination Number

The following table summarizes the fundamental distinctions between geometric and chemical coordination numbers, highlighting their defining characteristics and methodological approaches.

Table 1: Core Distinctions Between Geometric and Chemical Coordination Numbers

| Feature | Geometric Coordination Number | Chemical Coordination Number |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Purely geometrical and topographical arrangement of atoms in space [15] | Chemical bonding model applied to the atomic structure [15] [16] |

| Primary Determination Method | Analysis of interatomic distances (e.g., Brunner-Schwarzenbach method, Voronoi-Dirichlet partitioning) [15] [16] | Analysis based on bonding interactions, often involving electron density analysis (e.g., QTAIM) and chemical intuition [15] |

| Dependence on Bonding Model | Independent; does not require a predefined bonding model [15] | Dependent; the value is defined by the chosen bonding model [16] |

| Coordination Reciprocity | Often not pairwise symmetric (e.g., atom A may be a neighbor of B, but not vice versa) [15] | Inherently pairwise symmetric due to the nature of a chemical bond [15] |

| Output Nature | Often an integer, but can be a weighted effective CN (ECoN) [16] | An integer count of chemical bonds |

| Example of Discrepancy | In the α-iron (BCC) structure, the geometric CN can be considered 8 (nearest neighbors) or 14 (including next-nearest) [16]. | From a chemical bonding perspective, the CN may be considered 8, focusing on the strongest interactions [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Coordination Number Determination

Accurate determination of coordination numbers relies on specific experimental and computational protocols. The methodologies differ significantly depending on whether the goal is to extract geometric or chemical structural information.

Protocol for Geometric Coordination Number Analysis

The geometric coordination number is most commonly derived from crystallographic data obtained via X-ray, neutron, or electron diffraction experiments [16].

Step 1: Data Collection and Structure Refinement

- Procedure: A crystal of the material is analyzed via diffraction techniques. The resulting diffraction pattern is used to solve and refine the crystal structure, yielding a set of atomic coordinates, lattice parameters, and space group symmetry [15].

- Key Consideration: High-resolution data is crucial for accurate interatomic distance calculations.

Step 2: Interatomic Distance Calculation and Gap Analysis

- Procedure: A list of all interatomic distances from a central atom is generated and sorted in increasing order. The established Brunner-Schwarzenbach (BS) method is then applied to identify the first large gap in this distance sequence [15] [16].

- Mathematical Application: The gap signifies the boundary between the first coordination sphere and subsequent neighbors. The number of atoms before this gap is the geometric CN.

- Challenge: This method can produce non-reciprocal coordination (e.g., atom B is in A's coordination sphere, but A is not in B's) and may show multiple gaps of similar size, requiring a cut-off parameter [15].

Step 3: Voronoi-Dirichlet Partitioning (VDP) - An Alternative Geometric Method

- Procedure: Space is partitioned into polyhedral domains around each atom, comprising all points closer to that atom than to any other. Atoms whose Voronoi polyhedra share a face are considered neighbors [15].

- Result: The number of faces of the Voronoi polyhedron gives the maximum possible geometric CN. This method provides a unique, topology-based value but often overcounts compared to chemically expected coordination [15].

Protocol for Chemical Coordination Number Analysis

Determining the chemical coordination number moves beyond metrics to identify chemically meaningful bonds, which is particularly crucial in complex or disordered solids.

Step 1: Theoretical Electron Density Calculation

- Procedure: Employ quantum chemical calculations (e.g., Density Functional Theory) to obtain the theoretical electron-density distribution for the crystallographically determined structure. According to the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, this density defines all ground-state properties [15].

- Objective: To move beyond purely geometric analysis to a quantum-mechanical basis for identifying atomic interactions.

Step 2: Topological Analysis via QTAIM

- Procedure: The Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) is applied to the calculated electron density. In this framework, atomic basins are defined by zero-flux surfaces in the electron density gradient field. A bond path between two atoms indicates a chemical interaction [15].

- Innovation: Recent research utilizes triangulated surface data sets of QTAIM interatomic surfaces to calculate the solid angles subtended at each nuclear position. This allows for the calculation of a topological effective coordination number (tCN) that naturally includes the effect of different atomic sizes and satisfies coordination reciprocity [15].

Step 3: Coordination-Consistent Scenario Ranking

- Procedure: The tCN approach incorporates weighting functions to rank different possible coordination scenarios. This is vital in complex structures like intermetallic phases (e.g., TiNiSi type), where multiple coordination environments may be similarly plausible [15].

- Output: Instead of a single integer, the analysis may yield a list of different coordination scenarios with their relative weights and associated effective coordination numbers, providing a more nuanced chemical picture [15].

Visualization of Methodologies and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and workflows involved in differentiating and determining coordination numbers.

Conceptual Relationship and Determination Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Modern Coordination Number Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Coordination Number Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Single Crystals | High-quality, single-crystal samples are essential for obtaining high-resolution diffraction data required for accurate geometric and electron density analysis [16]. |

| X-ray Diffractometer | The primary instrument for experimental determination of crystal structures. Provides the atomic coordinate data that is the starting point for all coordination number analysis [16]. |

| Neutron Source | Provides neutron beams for neutron diffraction, which is particularly valuable for locating light atoms (e.g., H, Li) and distinguishing between elements with similar atomic numbers [16]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software packages (e.g., for DFT calculations) are used to compute the electron density distribution from the crystal structure, forming the basis for topological CN analysis [15]. |

| Topological Analysis Code | Specialized software (e.g., for QTAIM analysis) is required to perform topological analysis on the electron density to identify bond paths and calculate properties like the tCN [15]. |

| Hdac-IN-62 | Hdac-IN-62|HDAC Inhibitor|For Research Use |

| Src-3-IN-2 | Src-3-IN-2, MF:C15H12F3N5, MW:319.28 g/mol |

The distinction between geometric and chemical coordination numbers is not merely semantic but represents a fundamental divergence in approach between purely descriptive crystallography and interpretive chemical bonding analysis. The geometric coordination number offers a reproducible, if sometimes chemically naive, metric that is invaluable for structural classification and database creation. In contrast, the chemical coordination number seeks to reflect the physical reality of bonding, a goal increasingly within reach through modern electron-density-based approaches like the topological coordination number (tCN). The emerging paradigm, especially for complex structures, is to move beyond a single integer and embrace a weighted, multi-scenario description of atomic environment [15]. This nuanced understanding is critical for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on accurate structural descriptors to rationalize material properties, reactivity, and biological activity, ultimately feeding into the development of more predictive AI models for structure-property relationships [15].

The precise characterization of atomic coordination environments is a cornerstone of modern materials science and biochemistry, directly impacting the development of advanced catalysts, functional materials, and therapeutic agents. Coordination numbers (CN) and the spatial arrangement of neighboring atoms dictate fundamental properties such as catalytic activity, mechanical strength, and biological function. However, accurately determining CNs remains challenging across complex systems including intermetallic compounds, single-atom catalysts (SACs), and biomolecules, where dynamic behavior, structural complexity, and limitations of analytical techniques introduce significant uncertainties. This review systematically compares experimental and computational methods for CN determination across these diverse systems, evaluating their accuracy, limitations, and applicability through direct comparison of published data and methodologies. By framing this analysis within the broader thesis of coordination number determination accuracy, we provide researchers with a critical framework for selecting appropriate characterization strategies based on their specific system requirements and accuracy constraints.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Coordination Number in Context

The concept of coordination number originated from Werner's early work in coordination chemistry as a descriptor for the number of atoms directly bonded to a central atom [4]. In crystalline solids, CN represents a condensation of complete geometrical information about spatial atomic arrangements into a single numerical value specifying how many atoms inhabit the coordination environment of a central atom. While seemingly straightforward, the term lacks a universal mathematical definition, leading to methodological dependencies in its determination [4]. The International Union of Crystallography acknowledges that CN "depends on the chemical bonding model used," highlighting the tension between purely geometric and chemically meaningful definitions [4].

Methodological Approaches to CN Determination

Table 1: Comparison of Coordination Number Determination Methods

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Accuracy Limitations | Optimal Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Effective CN (tCN) | Analysis of electron density distributions via QTAIM; calculates solid angles subtended at nuclear positions by diatomic contact surfaces | Natural inclusion of atomic size effects; requires high-quality electron density data | Complex intermetallic phases; systems with significant atomic size disparities |

| Voronoi-Dirichlet Partitioning (VDP) | Geometric partitioning of space into regions closer to each atom than any other | Overcounts neighbors (maximal CN); sensitive to metric data alone; violates coordination reciprocity | Preliminary analysis of high-symmetry structures |

| Brunner-Schwarzenbach (BS) | Identifies first large gap in interatomic distance sequence | Cut-off parameter dependence; often non-reciprocal (A in B's sphere but not vice versa) | Binary and simple ternary compounds with clear coordination gaps |

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) | Measures fine structure of absorption edges to probe local coordination environment | Limited to ~0.02 nm distance resolution; requires reference compounds | SACs; dilute systems; in situ/operando studies |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Probes local magnetic field environment and dynamics via relaxation profiles | Limited to NMR-active nuclei; interpretation complexity in paramagnetic systems | Biomolecular systems; dynamics over wide timescales |

The topological coordination number (tCN) approach represents a significant advancement by leveraging electron density distributions from the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) [4]. This method calculates solid angles subtended at nuclear positions by diatomic contact surfaces, effectively generalizing the VDP approach while naturally incorporating atomic size effects. Even in highly symmetrical elemental structures, differences between VDP and tCN results emerge due to atomic electron-density decay utilizing available degrees of freedom in the crystal structure [4]. For complex structures like TiNiSi-type compounds, tCN enables numerical ranking between different sub-coordination scenarios of similar importance, providing a more precise characterization through listing different scenarios with relative weights and associated effective coordination numbers [4].

Intermetallic Compounds

Structural Complexity and CN Challenges

Intermetallic phases exhibit beneficial combinations of high strength, low density, and corrosion resistance, making them ideal for high-temperature applications and severe environments [17]. The accurate determination of coordination environments in these systems is complicated by often complex structures, mixed bonding character, and the presence of multiple constituent elements with different atomic sizes and electronegativities.

In high-entropy intermetallics (HEIs), additional complexity arises from the presence of five or more elements in ordered structures. For example, in L1â‚€-ordered PtCoNiFeCu HEI catalysts, the distribution of constituent elements creates local atomic segregation and cluster formation, leading to sub-angstrom strain that significantly influences catalytic performance [18]. This strain results from displacement of transition metal atoms in the TM layers due to local clustering/segregation driven by the stabilizing effect of Pt layers [18].

Experimental Approaches and Key Findings

Table 2: Coordination Environment Analysis in Selected Intermetallic Systems

| Material System | Primary Characterization Methods | Key Findings on Coordination Environment | Performance Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1â‚€-PtCoNiFeCu HEI [18] | In situ XRD, XAFS, Rietveld refinement, atomic-resolution STEM | Sub-angstrom strain in TM layers; N-doping induces tensile strain (3.680±0.003Ã… vs 3.675±0.003Ã…) | Mass activity: 2.19 A mgâ‚šâ‚œâ»Â¹ (MOR); Current density: 1388 mA cmâ»Â² at 0.7V after 90k cycles |

| Pt₃Co IMC [19] | Coordination-in-pipe engineering using SBA-15 templates, AC-HAADF-STEM, DFT | Particle size control (3-9 nm) via template diameter; coordination number manipulation via N-source | Mass activity: 2.19 A mgâ‚šâ‚œâ»Â¹ for MOR (highest with 1,10-phenanthroline N source) |

| TiNiSi-type compounds [4] | Topological CN (tCN) via QTAIM electron density analysis | Multiple weighted sub-coordination scenarios; superior to VDP in complex structures | Input for AI applications predicting structure-property relationships |

Advanced synthesis methods enable precise control over coordination environments in intermetallics. The coordination-in-pipe engineering approach using SBA-15 templates allows simultaneous regulation of particle size (3-9 nm) and coordination environments in Pt-based intermetallic compounds (Pt-IMCs) [19]. This method confines metal precursors and nitrogen sources within the pipes of SBA-15 before pyrolysis, effectively hindering nanoparticle growth radially while nitrogen-doped carbon restricts longitudinal growth [19]. The coordination numbers between metal and nitrogen can be regulated using different N sources, significantly impacting catalytic performance [19].

The sub-angstrom strain in HEI catalysts introduces anisotropic strain that distinguishes them from binary intermetallic compounds [18]. This strain, combined with the pinning effect of metal-N bonds and the high-entropy effect, contributes to exceptional stability, providing current density of 1388 mA cmâ»Â² at 0.7 V after 90,000 cycles under heavy-duty vehicle conditions [18]. Nitrogen doping further amplifies these effects through interstitial doping, creating tensile strain evidenced by larger lattice parameters in N-HEI/KB (3.680 ± 0.003 Ã…) compared to HEI/KB (3.675 ± 0.003 Ã…) [18].

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs)

Coordination Environment Significance

In single-atom catalysts, where isolated metal atoms are anchored on support materials, the coordination environment fundamentally determines catalytic performance. Unlike nanoparticles or intermetallic compounds, SACs lack metal-metal bonds, making the support-coordinate bonds exclusively responsible for stabilizing metal centers and modulating electronic properties. The coordination number in SACs typically refers to the number of heteroatoms (N, O, S, P) from the support directly bonded to the metal center, creating well-defined active sites with nearly 100% atom utilization.

Engineering Coordination Environments in SACs

Table 3: Coordination Engineering in Single-Atom Catalysts

| Catalyst System | Coordination Environment | Synthesis Strategy | Catalytic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt-IMCs on N-doped C [19] | Pt-Nâ‚“ coordination; tunable via N-source | Coordination-in-pipe engineering with SBA-15 templates | MOR mass activity: 2.19 A mgâ‚šâ‚œâ»Â¹; enhanced due to high chemical states of Pt/Co |

| Cu-N-C SACs [20] | Cu-Nâ‚“ sites in N-doped carbon | Pyrolysis of Cu precursors with N/C sources | Nitrate to ammonia conversion; performance depends on Cu speciation |

| M-N-C (M=Fe, Co, Ni) [20] | M-Nâ‚„ moieties in carbon matrix | Wet-impregnation or templating methods | ORR activity; stability challenges due to metal leaching |

Coordination engineering in SACs focuses on manipulating the number, identity, and spatial arrangement of atoms directly bonded to the metal center. The coordination-in-pipe engineering strategy demonstrates how both particle size and coordination environments can be simultaneously controlled in Pt-based catalysts [19]. By selecting appropriate nitrogen sources (e.g., 1,10-phenanthroline), the coordination number of interface metal atoms can be adjusted at the angstrom scale, directly influencing catalytic performance [19].

The chemical states of surface atoms, affected by nitrogen coordination number, facilitate electron accumulation on active sites, reduce activation energy of rate-determining steps, and enhance catalytic performance [19]. For Pt₃Co IMCs using 1,10-phenanthroline as the nitrogen source, the high chemical states of surface Pt and Co contribute to exceptional methanol oxidation reaction performance [19].

Biomolecular Systems

Coordination Complexity in Biological Contexts

Biomolecular coordination environments exhibit dynamic, often transient characteristics that complicate precise CN determination. In metalloproteins and supramolecular assemblies, metal centers frequently display coordination numbers that fluctuate in response to environmental conditions, substrate binding, and allosteric effects. The Cu/Zn/histidine supramolecular assemblies inspired by natural Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) exemplify how coordination environment optimization can dramatically enhance biological function [21].

Experimentation and Analysis in Biomolecular Systems

Table 4: Biomolecular Coordination Environment Studies

| System | Experimental Methods | Coordination Environment Details | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu/Zn/His Supramolecular Assemblies [21] | Gibbs free energy calculations, SOD activity assays | Optimized Cu²⺠site: 1 amino, 1 carboxyl, 2 imidazolyls (vs 4 imidazolyls in natural SOD) | SOD activity: 37,900 U/mg (5.4× natural SOD); promotes M1→M2 macrophage polarization |

| Biomolecular Dynamics [22] | Field-cycling NMR relaxometry, sample shuttling | Probing dynamics from ns-ms timescales; dipole-dipole, quadrupolar, CSA interactions | Atomic-resolution mobility mapping in near-physiological conditions |

In the CuZnHis system, researchers systematically compared different coordination modes for Cu²⺠sites [21]. Calculations revealed that replacing two imidazolyl coordinations with one amino and one carboxyl group (Structure D) created an optimized coordination environment with lower overall energy and reduced energy for coordination bond breaking/reformation during catalysis [21]. This optimized coordination environment yielded dramatically enhanced SOD activity of 37,900 U/mg, at least 5.4 times higher than natural Cu-Zn-SOD [21].

NMR relaxometry provides unique insights into biomolecular coordination dynamics through field-dependent relaxation profiles [22]. This approach probes dynamic processes over wide timescales by measuring nuclear relaxation rates across magnetic fields from ~200 μT to over 100 MHz [22]. The technique is particularly valuable for characterizing metal coordination environments in paramagnetic biomolecular systems, where electron-nuclear interactions dominate relaxation mechanisms [22].

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Cross-System Method Evaluation

The accuracy of coordination number determination varies significantly across methodological approaches and system types. Topological CN (tCN) analysis based on electron density distributions offers particular advantages for complex intermetallic phases, where it naturally incorporates atomic size effects and enables numerical ranking of competing sub-coordination scenarios [4]. This approach avoids the coordination reciprocity problems inherent in traditional geometric methods like Brunner-Schwarzenbach, where atom A may be counted in B's coordination sphere but not vice versa [4].

For SACs and supported catalysts, X-ray absorption spectroscopy provides element-specific coordination information but requires careful interpretation and reference compounds [19] [18]. The coordination-in-pipe engineering approach demonstrates how synthetic control can manipulate coordination environments while providing built-in validation through systematic variation of template sizes and nitrogen sources [19].

In biomolecular systems, where coordination environments are dynamic and often transient, NMR relaxometry and thermodynamic analysis of coordination bond breaking/reformation offer insights into functional coordination numbers under near-physiological conditions [21] [22]. The CuZnHis system exemplifies how computational guidance (Gibbs free energy calculations of different coordination modes) can direct the design of optimized coordination environments with enhanced biological activity [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Coordination Environment Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Coordination Studies | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|

| SBA-15 Templates | Mesoporous silica with tunable pore diameters (4-18 nm) for size-controlled synthesis | Confinement synthesis of Pt-IMCs with controlled particle size [19] |

| Nitrogen Sources (1,10-phenanthroline, etc.) | Coordination ligands that determine metal-N coordination number and chemical states | Adjusting coordination environments in Pt-IMCs for enhanced MOR activity [19] |

| Field-Cycling NMR Relaxometers | Instruments measuring nuclear relaxation rates from 0.01-100+ MHz Larmor frequency | Probing biomolecular dynamics over wide timescales [22] |

| Metal Precursors (Pt, Co, Ni, Fe, Cu salts) | Source of metal centers for intermetallic and SAC synthesis | Preparation of high-entropy intermetallic PtCoNiFeCu catalysts [18] |

| Histidine and Derivatives | Multidentate ligands for biomimetic coordination environments | Constructing optimized Cu catalytic sites in SOD-mimetic assemblies [21] |

| Lmp7-IN-2 | Lmp7-IN-2|Potent Immunoproteasome Inhibitor|Research Use | Lmp7-IN-2 is a potent immunoproteasome subunit inhibitor for autoimmune disease and cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Hdac6-IN-33 | Hdac6-IN-33, MF:C14H11F2N5O, MW:303.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comparative analysis reveals that accurate coordination number determination requires method selection tailored to specific system characteristics and research objectives. For intermetallic compounds with complex structures, topological approaches leveraging electron density distributions provide the most chemically meaningful CNs. In single-atom catalysts, coordination engineering combined with spectroscopic validation enables precise manipulation of active sites. For biomolecular systems, dynamic analysis through techniques like NMR relaxometry captures functionally relevant coordination environments. Across all systems, the integration of multiple complementary methods and computational guidance offers the most robust approach to characterizing coordination environments and correlating them with functional properties. As coordination environment design continues to gain importance in developing advanced materials and therapeutics, methodological advances in accurate CN determination will remain crucial for establishing reliable structure-property relationships.

Modern Analytical Methods for Coordination Environment Characterization

Voronoi-Dirichlet partitioning is a fundamental geometric construction for analyzing atomic environments in crystallography and materials science. The method partitions space into convex polyhedra (Voronoi cells) around generating points (atomic nuclei), where each location within a cell is closer to its generating point than to any other. Mathematically, for a set of generators (P = {p1, p2, \ldots, pn}) in space (Z), the standard Voronoi cell is defined as (V(pi) = \bigcap{j \ne i} {p \in Z | d(p,pi) < d(p,p_j) }), where (d) is the Euclidean distance [23]. In the context of coordination number determination, these cells provide an intuitive geometric framework for identifying neighboring atoms and quantifying local atomic environments by analyzing the faces, edges, and vertices of the resulting polyhedra.

The method's significance extends across multiple scientific domains. In quantum crystallography, Voronoi-based analysis helps refine crystal structures beyond the independent atom model, enabling more accurate electron density mapping and chemical bonding analysis [24]. For materials informatics, it facilitates high-throughput screening of ion transport pathways in solid electrolytes and electrode materials by characterizing void space geometry [23]. Recently, Voronoi tessellations have been integrated into deep learning models for catalyst discovery, where they provide structurally constrained graph representations that improve property prediction accuracy [25].

Comparative Analysis of Voronoi Method Variants

Fundamental Methodologies and Their Applications

The standard Voronoi decomposition, while mathematically elegant, proves inadequate for many crystallographic applications where atoms have significantly different radii. This limitation has spurred the development of several variants, each designed to address specific challenges in structural analysis.

Table 1: Key Variants of Voronoi-Dirichlet Partitioning in Structural Science

| Method Variant | Mathematical Foundation | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Voronoi | (V(pi) = \bigcap{j \ne i} {p \in Z | d(p,pi) < d(p,pj) }) [23] | Initial structure analysis, monodisperse systems | Computational simplicity, intuitive geometric interpretation |

| Radical Voronoi | (V(pi) = \bigcap{j \ne i} {p \in Z | d(p,pi)^2 - ri^2 < d(p,pj)^2 - rj^2 }) [23] | Crystals with atoms of unequal radii, ionic transport analysis | Accounts for atomic size differences, maintains convex polyhedra |

| Voronoi S | (V(pi) = \bigcap{j \ne i} {p \in Z | d(p,pi) - ri < d(p,pj) - rj }) [23] | Theoretical modeling of polydisperse systems | Most accurate representation of size-asymmetric systems |

| Residual-Weighted CVT | Adaptive sampling based on Voronoi tessellation with residual constraints [26] | Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for PDE solutions | Improves prediction accuracy and stability in computational physics |

The radical Voronoi decomposition (also called Voronoi S-tessellation) represents a crucial advancement for practical crystallographic applications. It effectively compromises between the computational simplicity of the standard approach and the physical accuracy of the Voronoi S method, which produces curved boundaries that are computationally challenging to handle [23]. The radical method's ability to generate convex polyhedra while accounting for atomic radii makes it particularly suitable for analyzing structures with mixed elements, such as intermetallic compounds and ionic crystals.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Evaluating the performance of these methods reveals significant differences in their practical utility for coordination environment analysis. The CAVD Python package, specifically designed for crystal structure analysis, implements radical Voronoi decomposition with environment-aware ionic radii to address coordination-dependent size variations [23].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Voronoi-Based Methods for Structural Analysis

| Method Variant | Mobile Ion Site Recovery Rate | Computational Efficiency | Stability Across PDE Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Voronoi | Limited (excludes face-centered sites) [23] | High | Limited for nonlinear equations [26] |

| Radical Voronoi (CAVD) | 99% (6,955 ionic compounds) [23] | Moderate | Not specifically tested |

| Residual-Constrained V.T. (RVT) | Not applicable | Comparable to other sampling methods | Superior across various PDE problems [26] |

| Residual-Weighted CVT (RCVT) | Not applicable | Comparable to other sampling methods | Superior across various PDE problems and initialization conditions [26] |

The exceptional 99% recovery rate for mobile ion sites achieved by the CAVD tool demonstrates the critical importance of method selection. This performance advantage stems directly from its incorporation of Voronoi polyhedra faces as potential sites for mobile ions, whereas standard approaches typically consider only vertices and edges [23]. This comprehensive mapping of the void space enables more accurate prediction of ionic transport pathways in solid electrolytes and electrode materials.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation Workflow for Geometric Analysis

The standard experimental protocol for Voronoi-Dirichlet analysis in coordination number determination follows a systematic workflow implemented in tools like CAVD and ToposPro:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for Voronoi-Dirichlet analysis in crystal structures

The process begins with crystal structure input followed by symmetry analysis using libraries like Spglib [23]. The critical atomic radius assignment step combines the rigorous coordination number definition by O'Keeffe with Shannon's effective ionic radii to account for coordination environment effects [23]. The core radical Voronoi decomposition is then performed, typically implemented via modified versions of the Voro++ library [23]. Finally, the resulting Voronoi network is analyzed to calculate structural descriptors and identify transport pathways.

Advanced Computational Frameworks

In machine learning applications, particularly for catalyst discovery, Voronoi tessellations enrich graph neural network representations. The experimental protocol involves:

- Graph Construction: Crystal structures are represented as graphs with atoms as nodes

- Voronoi Enhancement: Voronoi tessellation calculates solid angles and contact types as edge features, and Voronoi volumes as node characteristics [25]

- Property Prediction: The enhanced graph representation improves prediction of catalytic properties and formation energies [25]

This approach has demonstrated significant performance improvements, reducing the mean absolute error to 6 meV/atom on intermetallics datasets, well below the physically significant 20 meV/atom threshold [25].

Limitations and Methodological Constraints

Fundamental Geometric Limitations

Despite its mathematical elegance, Voronoi-Dirichlet partitioning exhibits several inherent limitations that affect its accuracy for coordination number determination:

Atomic Size Disparity: The standard Voronoi decomposition becomes increasingly inaccurate for structures containing atoms with significantly different radii [23]. This poses particular challenges for organometallic compounds and minerals containing heavy and light elements.

Dynamic Behavior Neglect: Traditional Voronoi analysis provides a static geometric snapshot, unable to capture thermal motion and dynamic disorder effects crucial for understanding ionic transport mechanisms [24].

Face-Centered Site Oversight: Standard Voronoi network approaches that consider only vertices and edges fail to identify mobile ion positions located on Voronoi polyhedra faces [23], potentially missing critical migration pathways.

Experimental Data Dependence: Quantum crystallographic applications using Voronoi-based methods remain heavily dependent on high-quality experimental data, as evidenced by dedicated efforts to obtain accurate temperature-dependent structure factors for reliable electron density analysis [24].

Implementation Challenges

Practical implementation of Voronoi methods faces several computational and methodological hurdles:

Radius Assignment Ambiguity: The accuracy of radical Voronoi methods depends critically on appropriate atomic radius selection, complicated by the dependence of ionic radii on coordination environments [23].

Boundary Approximation: The radical Voronoi approach, while more computationally tractable than the Voronoi S method, only approximates the true curved boundaries between atoms of different sizes [23].

High-Dimensional Extension: Current Voronoi-based sampling methods for physics-informed neural networks have proven effective for two-dimensional problems, but extension to three-dimensional cases requires further development [26].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Computational Infrastructure

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Voronoi-Dirichlet Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CAVD Python Package | Geometric analysis of void space in crystals | High-throughput screening of ionic transport materials [23] |

| Voro++ Library | Periodic radical Voronoi decomposition | Core computational engine for space partitioning [23] |

| Spglib | Symmetry analysis of crystal structures | Preprocessing for Voronoi tessellation [23] |

| Shannon Ionic Radii | Effective ionic radii database | Atomic size parameterization for radical Voronoi [23] |

| Open Catalyst Project Dataset | Benchmark dataset for catalytic properties | Validation of Voronoi-enhanced machine learning models [25] |

The CAVD Python package exemplifies the modern implementation of Voronoi-based structural analysis, specifically designed for high-throughput ion-transport analysis and freely available to the research community [23]. It builds upon the computational geometry capabilities of the Voro++ library while adding chemistry-aware functionality through proper atomic radius assignment and consideration of Voronoi faces in network construction.

Specialized Methodological Components

For quantum crystallographic applications, specialized tools have been developed to address specific refinement challenges:

- Hirshfeld Atom Refinement (HAR): Integrates quantum chemical electron densities with X-ray diffraction data, moving beyond the independent atom model [24]

- NoSpherA2: Implements effective core potentials with ZORA to accelerate refinement of heavy-element structures [24]

- expHAR: Alternative electron density partition scheme that improves hydrogen position accuracy [24]

- ReCrystal: Employs periodic DFT-derived multipoles for tailored refinement without external libraries [24]

These tools represent the cutting edge of crystallographic refinement, addressing fundamental limitations of traditional independent atom model approaches that still dominate routine structure determination.

Voronoi-Dirichlet partitioning remains an indispensable geometric approach for coordination number determination and structural analysis across crystallography, materials science, and computational chemistry. The method's fundamental strength lies in its intuitive geometric representation of atomic environments and void space topology. The development of radical Voronoi variants has significantly addressed the critical limitation of atomic size disparity, enabling accurate analysis of complex multi-element systems as demonstrated by the 99% site recovery rate achieved by the CAVD tool.

Nevertheless, important limitations persist, particularly regarding the treatment of dynamic processes, electron density deformations in chemical bonds, and computational challenges in high-dimensional applications. The ongoing integration of Voronoi-based descriptors into machine learning frameworks represents a promising direction, combining geometric intuition with data-driven pattern recognition. As quantum crystallography continues to advance beyond the independent atom model, Voronoi-inspired methodologies will likely play an increasingly important role in bridging experimental measurement and quantum mechanical theory, ultimately enabling more accurate structure-property relationships for materials design and drug development.

Topological Coordination Numbers from Electron Density Distributions

In crystallography and materials science, the coordination number (CN) is a fundamental descriptor that condenses the complex spatial arrangement of atoms surrounding a central atom into a single number. Traditionally, this parameter has been determined through geometric approaches analyzing interatomic distances or Voronoi partitioning. However, these methods possess significant limitations, including coordination reciprocity violations where atom A may be counted in the coordination sphere of B, but not vice versa, despite the same interatomic distance. This inconsistency presents substantial challenges for physical chemistry applications where bonding interactions are inherently pairwise symmetric [15].

The emerging paradigm of quantum crystallography, which celebrates the centenary of quantum mechanics in 2025, bridges crystallographic experimentation with quantum theoretical approaches [24]. Within this framework, a novel methodology has been developed: topological coordination numbers (tCNs) derived from electron density distributions. This approach leverages the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) to provide a more physically meaningful characterization of atomic coordination that obeys coordination reciprocity principles [15] [27]. This analysis is particularly valuable for understanding complex structures such as intermetallic phases and represents a significant advancement in digitizing structural information for artificial intelligence applications predicting structure-property relationships [15].

Methodological Comparison: Traditional vs. Topological Approaches

Established Coordination Number Determination Methods

Traditional CN evaluation methods rely primarily on geometric information derived from crystal structures:

- Distance-Based Methods: The Brunner-Schwarzenbach (BS) approach identifies the first large gap in the sequence of increasing interatomic distances. Used in major databases like Pearson's Crystal Data, this method suffers from subjectivity in gap identification and frequent reciprocity violations [15].

- Voronoi-Dirichlet Partitioning (VDP): This geometric construction defines spatial domains around each atom, with coordination determined by polyhedra sharing faces. While more systematic, VDP typically overcounts coordination (yielding higher CNs than chemically expected) and doesn't naturally account for atomic size differences [15].

- Effective Coordination Numbers (ECoN): This refinement applies weights to neighbors based on solid angles or other parameters, but often requires empirical corrections [15] [28].

Topological Coordination Number (tCN) Methodology

The tCN approach represents a paradigm shift by using the fundamental electron density distribution rather than purely geometric considerations:

- Foundation in Electron Density: According to the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, all ground-state properties of a system, including structure, are determined by its electron density distribution [15].

- QTAIM Framework: The method employs triangulated surface data sets of QTAIM interatomic surfaces to calculate solid angles subtended at nuclear positions by each diatomic contact surface [15] [29].

- Coordination Reciprocity: A fundamental advantage is built-in pairwise symmetry, ensuring that if atom A coordinates to B, then B also coordinates to A—a physical requirement often violated in traditional methods [15] [27].

- Atomic Size Effects: Unlike VDP, the tCN approach naturally incorporates different atomic sizes through their distinct electron density decay profiles [15].

- Multiple Scenarios with Weights: Rather than forcing a single CN value, tCN analysis can identify and rank multiple chemically plausible sub-coordination scenarios with associated weights, providing a more nuanced description, especially in complex structures [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Coordination Number Determination Methods

| Method | Fundamental Basis | Reciprocity Guaranteed? | Accounts for Atomic Size? | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunner-Schwarzenbach | Interatomic distances | No | No | Multiple gaps of similar size; cutoff parameter dependent |

| Voronoi-Dirichlet | Geometric space partitioning | Yes (by face sharing) | No (without corrections) | Overcounts coordination; purely geometric |

| Effective Coordination (ECoN) | Weighted solid angles/overlaps | Not necessarily | With parameterization | Requires empirical corrections |

| Topological CN (tCN) | Electron density distribution (QTAIM) | Yes | Yes, naturally | Computationally more demanding |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Theoretical Foundation and Computational Framework

The tCN methodology builds upon the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) developed by Bader [15] [29]. The core principle involves analyzing the topology of the electron density distribution Ï(r), particularly its gradient vector field ∇Ï(r) and Laplacian ∇²Ï(r). Atomic basins are defined by zero-flux surfaces satisfying ∇Ï(r)·n(r) = 0, where n(r) is the unit vector normal to the surface. Bond critical points (BCPs) occur where ∇Ï(r) = 0, and atomic interaction lines connecting nuclei through BCPs define the molecular graph representing chemical bonding [29].

For tCN determination, the key innovation involves calculating solid angles subtended by QTAIM interatomic surfaces at nuclear positions. These solid angles provide a quantitative measure of the "share" each neighbor has in the coordination sphere. The topological effective coordination numbers are then derived by summing these contributions according to specific weighting functions based on geometrical properties of square and semicircle areas [15].

Workflow for tCN Determination

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for determining topological coordination numbers from initial structure to final coordination analysis:

Workflow for tCN Determination

Application to Material Classes