Electronic Structure of Transition Metal Complexes: From Quantum Fundamentals to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the electronic structure of transition metal complexes (TMCs), bridging fundamental quantum principles with cutting-edge applications in drug discovery and biomedicine.

Electronic Structure of Transition Metal Complexes: From Quantum Fundamentals to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the electronic structure of transition metal complexes (TMCs), bridging fundamental quantum principles with cutting-edge applications in drug discovery and biomedicine. It establishes the foundational role of d-orbitals, redox activity, and coordination geometry in defining the unique reactivity of TMCs. The content details advanced computational methodologies—including Density Functional Theory (DFT), molecular docking, and emerging machine learning frameworks like the ELECTRUM fingerprint—for predicting properties and modeling interactions with biological targets. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting the inherent challenges of simulating TMCs, such as multi-reference character and spin-state energetics. Finally, the article presents rigorous validation and comparative analyses, benchmarking computational methods against experimental data and highlighting case studies of TMCs as successful enzyme inhibitors and cytotoxic agents. This resource is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage the distinctive electronic properties of TMCs for therapeutic innovation.

Quantum Foundations: Unraveling the Electronic Principles of Transition Metal Complexes

In the realm of inorganic chemistry and transition metal complex research, d-orbitals constitute the fundamental architectural elements that dictate an extraordinary range of chemical behaviors unseen in organic molecular systems. These five atomic orbitals—dxy, dyz, dxz, dx²-y², and dz²—possess unique spatial orientations and energy characteristics that enable transition metals to engage in bonding paradigms far beyond the scope of carbon-based chemistry [1] [2]. The investigation of d-orbital behavior through crystal field theory, ligand field theory, and molecular orbital theory provides researchers with powerful predictive frameworks for understanding molecular geometry, electronic configuration, magnetic properties, and catalytic capabilities [3] [4]. For drug development professionals working with metallopharmaceuticals and researchers designing catalytic systems, mastering d-orbital fundamentals is essential for rational compound design. This whitepaper examines how the distinctive shapes, energy splittings, and electron configurations of d-orbitals underpin the unique reactivity of transition metal complexes, with direct implications for advanced materials development and therapeutic agent design.

Fundamental Characteristics of d-Orbitals

Structural and Energetic Properties

Transition metal d-orbitals represent a five-fold degenerate set (at equivalent energy in isolated atoms) characterized by complex directional orientations. Each orbital possesses a distinctive geometry: the dxy, dyz, and dxz orbitals exhibit a four-leaf clover shape oriented between the Cartesian axes, while the dx²-y² orbital is similarly shaped but oriented along the x and y axes. The dz² orbital displays a unique doughnut-shaped torus in the xy-plane with two opposing lobes along the z-axis [1] [5]. All d-orbitals contain two angular nodes, which manifest as planar angular nodes bisecting the lobes in four of the orbitals, and as conical angular nodes separating the toroidal and lobular regions in the dz² orbital [1]. These directional characteristics directly enable the diverse bonding interactions and geometric arrangements observed in transition metal complexes.

The electron occupancy of d-orbitals follows fundamental quantum mechanical principles, with each orbital capable of hosting a maximum of two electrons with opposed spins, yielding a total d-orbital capacity of ten electrons [2]. In transition metal ions—the form typically encountered in coordination compounds—the (n-1)d orbitals constitute the valence shell where bonding and electron transitions occur [6]. The energy degeneracy of these five orbitals is maintained only in spherical symmetry; when ligands approach a metal center, their directional electrostatic interactions and orbital overlaps lift this degeneracy, producing characteristic splitting patterns that dictate the complex's electronic behavior [6] [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of d-Orbitals

| Property | dxy, dyz, dxz | dx²-y² | dz² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Orientation | Between axes | Along x and y axes | Along z-axis with torus in xy-plane |

| Angular Nodes | 2 planar | 2 planar | 2 conical |

| Lobe Structure | Four cloverleaf lobes | Four cloverleaf lobes | Two lobes with equatorial torus |

| Common Orbital Set Designation | t₂g (octahedral) | eg (octahedral) | eg (octahedral) |

Quantum Mechanical Framework

The d-orbitals emerge as solutions to the Schrödinger equation for systems with principal quantum number n ≥ 3 and angular momentum quantum number l = 2 [1] [7]. The magnetic quantum number (mℓ) for d-orbitals spans integer values from -2 to +2, corresponding to the five distinct orbital functions [1]. In many-electron atoms, these orbitals are approximated using hydrogen-like wavefunctions, Slater-type orbitals, or Gaussian-type orbitals, with the latter being particularly important for computational studies of molecular systems [7].

The historical understanding of d-orbitals evolved through successive theoretical refinements, beginning with Nagaoka's "Saturnian model" (1904), Bohr's quantized orbital model (1913), and culminating in the modern quantum mechanical conception incorporating wave-particle duality [7]. The term "orbital" itself was coined by Robert S. Mulliken in 1932 as an abbreviation for "one-electron orbital wave function," reflecting the transition from classical planetary orbits to probabilistic electron distributions [7]. This theoretical progression enables researchers to accurately model the behavior of d-electrons in complex chemical environments.

Theoretical Models of d-Orbital Behavior in Coordination Complexes

Crystal Field Theory: An Electrostatic Approach

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) provides a foundational electrostatic model for understanding d-orbital splitting patterns in coordination complexes. CFT conceptualizes metal-ligand interactions as purely electrostatic attractions between point-negative charges on ligands and the positively charged metal center, complemented by repulsive interactions between ligand electrons and d-orbital electrons [6]. This approach successfully explains the color, magnetic properties, and certain stability trends in transition metal complexes through its treatment of d-orbital energetics [3].

In the octahedral coordination geometry—the most common arrangement in transition metal chemistry—the five degenerate d-orbitals split into two distinct energy sets when ligands approach along the x, y, and z axes [6] [4]. The dz² and dx²-y² orbitals (collectively termed the eg set) experience direct electrostatic repulsion with approaching ligands, raising their energy significantly. Conversely, the dxy, dxz, and dyz orbitals (the t₂g set) point between the coordinate axes and experience less direct repulsion, consequently stabilizing at lower energy [6]. The energy separation between these sets is designated the crystal field splitting parameter (Δo), a fundamental value that governs electronic configurations and resultant properties [6].

Diagram 1: d-Orbital Splitting in Octahedral Field

CFT quantitatively accounts for the energy relationships in d-orbital splitting: the two eg orbitals increase in energy by 0.6Δo, while the three t₂g orbitals decrease in energy by 0.4Δo, maintaining the barycenter (weighted average energy) of the d-orbitals [6]. This energy separation enables d-d electronic transitions that absorb specific wavelengths of light, generating the characteristic colors of transition metal complexes [6]. The magnitude of Δo varies systematically with factors including metal oxidation state, ligand identity, and periodic row position, enabling researchers to predict and manipulate complex properties [4].

Ligand Field Theory: A Molecular Orbital Perspective

Ligand Field Theory (LFT) extends beyond CFT's electrostatic model by incorporating covalent bonding through molecular orbital theory [3] [4]. LFT recognizes that ligand orbitals form bonding and antibonding combinations with metal d-orbitals, providing a more comprehensive framework for understanding electronic structure and reactivity [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for explaining phenomena such as π-backbonding in organometallic compounds and the spectrochemical series of ligand strengths [8] [4].

In LFT's treatment of octahedral complexes, the dz² and dx²-y² orbitals form strong σ-antibonding interactions with ligand donor orbitals, creating high-energy eg molecular orbitals [4]. The dxy, dxz, and dyz orbitals may form π-interactions with appropriate ligand orbitals, influencing the magnitude of Δo [4]. The resulting molecular orbital diagram features the t₂g and eg sets as primarily metal-based non-bonding and antibonding orbitals, respectively, which correspond to the crystal field splitting picture while incorporating covalent bonding effects [4]. This theoretical framework enables researchers to predict how specific ligand modifications will alter d-orbital energies and consequent complex reactivity.

Table 2: Comparison of Bonding Theories for d-Orbital Complexes

| Theory | Fundamental Approach | Explanatory Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valence Bond Theory | Hybridization of metal orbitals | Molecular geometry prediction | Inadequate for spectroscopy and magnetism |

| Crystal Field Theory | Electrostatic ligand interactions | Color, magnetic properties, stability trends | Cannot explain covalent bonding or spectrochemical series |

| Ligand Field Theory | Molecular orbital formation | Full range of electronic properties, bonding description | Computational complexity |

Experimental Determination of d-Orbital Properties

Spectroscopic Methods for Probing d-Orbital Splitting

Electronic absorption spectroscopy represents the most direct experimental methodology for determining d-orbital splitting energies (Δo) in transition metal complexes [6]. The technique measures the energy of electronic transitions between the t₂g and eg orbital sets, providing quantitative values for Δo through the relationship Δo = hc/λ, where λ is the wavelength of maximum absorption [6]. For accurate measurements, researchers prepare complex solutions at precise concentrations (typically 0.01-0.1 M) in spectroscopically transparent solvents, recording spectra across the ultraviolet-visible range (200-800 nm) [6]. The resulting data enables the construction of spectrochemical series that rank ligands by their field strength and metal centers by their oxidation states and periodic positions.

Magnetic susceptibility measurements provide complementary data for determining d-orbital electron configurations [3] [4]. The Evans method, a common NMR-based technique, quantifies paramagnetism arising from unpaired d-electrons [4]. Researchers prepare a reference solution containing pure solvent in a capillary tube placed within an NMR tube containing the complex solution, measuring the chemical shift difference between the internal and external reference signals [4]. This shift difference relates directly to the magnetic moment, which indicates the number of unpaired electrons and thus the high-spin or low-spin configuration of the complex [4]. These measurements are particularly diagnostic for metal centers with d4-d7 electron configurations, where both spin states are possible depending on the magnitude of Δo [4].

Computational Approaches for d-Orbital Analysis

Modern computational chemistry provides powerful tools for investigating d-orbital interactions that complement experimental approaches. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations with appropriate functionals (e.g., PBE, B3LYP) and basis sets (including effective core potentials for heavier metals) enable researchers to visualize d-orbital shapes, calculate energy splittings, and predict electronic spectra [9]. Crystal Orbital Hamiltonian Population (COHP) analysis quantifies bonding interactions between metal d-orbitals and ligand orbitals, with negative integrated COHP (ICOHP) values indicating stabilizing bonding character [9].

For the computational determination of d-orbital properties, researchers typically employ this standardized protocol:

- Geometry Optimization: The complex structure is optimized to its minimum energy configuration using DFT methods.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Single-point energy calculations at the optimized geometry generate the molecular orbital diagram.

- Population Analysis: Projected Density of States (PDOS) and COHP analyses decompose contributions from specific d-orbitals.

- Spectrum Prediction: Time-Dependent DFT calculations simulate electronic transitions for comparison with experimental spectra.

This methodology successfully identifies even unexpected d-orbital interactions, such as the d-d coupling between magnesium and iodine atoms under high pressure recently reported in computational studies [9].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for d-Orbital Analysis

Electronic Configurations and Magnetic Properties

High-Spin and Low-Spin Complexes

The electron configuration in d-orbital complexes is governed by the interplay between the crystal field splitting energy (Δo) and the electron pairing energy (P) [4]. When Δo is relatively small, electrons preferentially occupy higher-energy orbitals rather than pairing in lower-energy orbitals, generating high-spin complexes with maximum unpaired electrons [4]. Conversely, large Δo values favor electron pairing in lower-energy orbitals, producing low-spin complexes with minimized unpaired electrons [4]. This spin-state dichotomy directly influences molecular properties including magnetism, reactivity, and biological function.

For drug development professionals, understanding spin states is particularly relevant for metallopharmaceuticals such as iron-based anticancer compounds or cobalt-containing diagnostic agents. The spin crossover phenomenon—where external stimuli like temperature or pressure induce transitions between spin states—enables smart materials design for controlled drug release systems [4]. Researchers can predict spin states by comparing the spectroscopically determined Δo with pairing energies estimated from atomic spectra, or computationally through DFT calculations of the energy difference between possible configurations [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Spin-State Characterization

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for d-Orbital Complex Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (DMSO-d6, CDCl3) | NMR spectroscopy medium | Magnetic susceptibility via Evans method |

| Ferrocene Standard | Redox potential reference | Electrochemical studies of d-orbital energies |

| TEMPO Radical | Spin quantification standard | EPR spectroscopy calibration |

| Ionic Ligands (CN⁻, F⁻) | Strong-field/weak-field ligands | Modulating Δo for spin-state control |

| Metal Salts (FeCl₃, Co(NO₃)₂) | Synthetic precursors | Complex preparation with varied metal centers |

Implications for Reactivity and Drug Development

Catalytic Applications Through d-Orbital Manipulation

The distinctive reactivity of transition metal complexes originates directly from their partially filled d-orbitals, which enable unique bonding scenarios including oxidative addition, reductive elimination, and insertion reactions [8]. In organometallic catalysis, the energy and occupancy of metal d-orbitals determine the feasibility and selectivity of fundamental transformations including cross-couplings, hydrogenations, and polymerizations [8]. The 18-electron rule—a guiding principle for organometallic compound stability—derives from the nine valence orbitals (one s, three p, five d) available on transition metals to accommodate 18 electrons in bonding and non-bonding molecular orbitals [8].

For pharmaceutical researchers, d-orbital engineering enables the design of sophisticated catalysts for asymmetric synthesis of chiral drug molecules. Ligand modifications that alter d-orbital splitting patterns directly influence the stereochemical environment at the metal center, enabling enantioselective transformations [2]. The emerging recognition of d-d orbital coupling in non-traditional systems, including main-group elements under high pressure, further expands the toolbox for catalytic design [9]. These principles underpin technologically significant processes including pharmaceutical synthesis, materials production, and energy conversion technologies.

Therapeutic Implications of d-Orbital Chemistry

In medicinal chemistry, d-orbital characteristics directly influence the biological activity of metallopharmaceuticals. Platinum anticancer agents (cisplatin, carboplatin) exert their therapeutic effect through square planar d⁸ Pt(II) centers that coordinate to DNA nucleobases [2]. The specific geometry and ligand exchange kinetics of these complexes—dictated by d-orbital splitting patterns—determine their DNA binding selectivity and consequent cytotoxicity [2]. Similarly, gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents leverage the unpaired electrons in f-orbitals (conceptually analogous to d-orbitals) to enhance proton relaxation rates in tissues [2].

Drug development professionals can manipulate d-orbital properties through strategic ligand design to optimize therapeutic indexes. For instance, iron-containing antimalarials exploit the variable oxidation states accessible through d-electron transfer to generate reactive oxygen species toxic to Plasmodium parasites [4]. The emerging field of metalloimmunology further demonstrates how d-orbital complexes modulate immune responses through interactions with biological coordination sites, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention [2]. Understanding these structure-activity relationships enables rational design of metallopharmaceuticals with tailored target engagement and pharmacokinetic profiles.

d-Orbitals constitute the fundamental electronic feature distinguishing transition metal chemistry from organic molecular systems, enabling an extraordinary range of structural motifs, electronic phenomena, and chemical reactivities. Through Crystal Field and Ligand Field Theories, researchers can systematically understand and predict how d-orbital splitting patterns dictate molecular geometry, magnetic behavior, spectroscopic properties, and catalytic function. For drug development professionals, mastering these principles enables rational design of metallopharmaceuticals with tailored therapeutic properties, while materials researchers leverage d-orbital characteristics to develop advanced catalysts and functional materials. The continued investigation of d-orbital behavior—including emerging discoveries of d-orbital participation in main-group elements under extreme conditions [9]—promises to further expand the boundaries of chemical reactivity beyond traditional paradigms.

The electronic structure of transition metal complexes serves as a foundational concept in inorganic chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, dictating their chemical reactivity, magnetic behavior, and spectroscopic properties. This whitepaper examines three key electronic parameters—oxidation state, spin state, and coordination geometry—that collectively govern the behavior of transition metal complexes within the broader context of electronic structure research. Understanding the intricate interplay between these parameters enables researchers to rationally design complexes with tailored properties for applications ranging from anticancer drugs to redox catalysts. The oxidation state defines the metal's electron count and charge distribution, the spin state describes the arrangement of unpaired electrons, and the coordination geometry determines the spatial distribution of ligands around the metal center. Together, these parameters provide a comprehensive framework for predicting and interpreting the physical and chemical behavior of coordination compounds, forming the basis for advanced research in transition metal chemistry [10] [11].

Theoretical Framework

Crystal Field Theory Fundamentals

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) provides a quantitative model for understanding how transition metal complexes behave based on their electronic structure. CFT describes the breaking of degeneracies of electron orbital states, usually d or f orbitals, due to a static electric field produced by a surrounding charge distribution of ligands. The theory assumes metal-ligand interactions are purely electrostatic in nature, where ligands are treated as point charges interacting with the central metal ion's d-orbitals [12] [13] [14].

In an octahedral complex, the five degenerate d-orbitals split into two distinct energy levels: the higher-energy eg orbitals (d{x^2-y^2} and d{z^2}) that point directly toward the ligands, and the lower-energy t{2g} orbitals (d{xy}, d{xz}, and d{yz}) that point between the ligands. The energy difference between these sets is known as the crystal field splitting parameter, Δo (or Δoct) [15] [14]. The magnitude of Δo is critical as it determines whether a complex will adopt a high-spin or low-spin configuration, which in turn affects magnetic properties, spectroscopic behavior, and stability [15] [13].

Table: Crystal Field Splitting in Different Geometries

| Geometry | Orbital Splitting | Splitting Magnitude | Common Electron Configurations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Octahedral | eg higher than t{2g} | Δ_o | High-spin: d^4-d^7; Low-spin: d^4-d^7 |

| Tetrahedral | e higher than t_2 | Δtet ≈ 4/9Δo | Almost always high-spin |

| Square Planar | Complex splitting | Largest Δ | d^8 metals (Ni^2+, Pd^2+, Pt^2+, Au^3+) |

For tetrahedral complexes, the d-orbital splitting is inverted compared to octahedral complexes, with the e orbitals (d{z^2} and d{x^2-y^2}) lower in energy than the t2 orbitals (d{xy}, d{xz}, and d{yz}). Additionally, the magnitude of splitting is smaller, with Δtet being roughly 4/9 of Δo for equivalent metals and ligands. This smaller splitting energy means tetrahedral complexes are almost invariably high-spin [15] [13].

Oxidation States

The oxidation state of a transition metal represents its formal charge within a complex and significantly influences its electronic properties. Higher oxidation states lead to larger crystal field splitting due to contracted metal orbitals and stronger metal-ligand interactions. For example, a V^3+ complex will have a larger Δ_o than a V^2+ complex with the same ligands because the higher charge density allows ligands to approach more closely, increasing electrostatic repulsions with the d-orbitals [13] [11].

The oxidation state directly affects the d-electron count, which determines how electrons populate the split d-orbitals. This electron configuration influences properties such as color, magnetism, and catalytic activity. In research settings, accurately determining oxidation states is crucial for understanding reaction mechanisms, particularly in redox-active catalysts where metals cycle between different oxidation states during catalytic cycles [11].

Spin States

Spin states in transition metal complexes describe the distribution of electrons among the d-orbitals and the resulting number of unpaired electrons. Complexes can exist in high-spin or low-spin configurations depending on the relative magnitudes of the crystal field splitting energy (Δ_o) and the spin-pairing energy (P) [15] [14].

- High-spin complexes: Occur when Δ_o < P, favoring maximum unpaired electrons according to Hund's rule

- Low-spin complexes: Occur when Δ_o > P, favoring electron pairing in lower-energy orbitals

The spin state affects numerous physical properties, including magnetic behavior, ionic radii, and ligand exchange rates. Low-spin complexes typically have smaller ionic radii and slower ligand exchange rates compared to their high-spin counterparts with the same metal and oxidation state [15].

Table: Spin State Configurations for Octahedral Complexes

| d-electron count | High-spin configuration | Unpaired electrons (high-spin) | Low-spin configuration | Unpaired electrons (low-spin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d^4 | t{2g}^3 eg^1 | 4 | t_{2g}^4 | 2 |

| d^5 | t{2g}^3 eg^2 | 5 | t_{2g}^5 | 1 |

| d^6 | t{2g}^4 eg^2 | 4 | t_{2g}^6 | 0 |

| d^7 | t{2g}^5 eg^2 | 3 | t{2g}^6 eg^1 | 1 |

Second and third-row transition metals invariably form low-spin complexes due to their larger crystal field splitting energies, while first-row transition metals can exhibit both high-spin and low-spin configurations depending on the ligand field strength [15].

Coordination Geometry

The spatial arrangement of ligands around the central metal ion, known as coordination geometry, profoundly influences d-orbital splitting patterns. The most common geometries include octahedral, tetrahedral, and square planar, each producing distinct splitting patterns that govern the electronic properties of the complex [15] [13].

Octahedral geometry produces the characteristic splitting into t{2g} and eg sets, while tetrahedral geometry creates a smaller, inverted splitting. Square planar geometry, often adopted by d^8 metal ions like Ni^2+, Pd^2+, Pt^2+, and Au^3+, results from significant splitting that removes degeneracy from all d-orbitals [15]. The geometry directly affects the crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE), which contributes to the complex's thermodynamic stability and kinetic lability.

Experimental Determination Methods

Spectroscopic Techniques

Advanced spectroscopic methods provide powerful tools for characterizing the electronic parameters of transition metal complexes.

L-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) directly probes metal-derived 3d valence orbitals through dipole-allowed 2p→3d transitions. This technique is particularly sensitive to oxidation state changes, showing distinct blue shifts in absorption energies with increasing oxidation state. For example, Mn L-edge XAS demonstrates a clear energy shift between Mn^II(acac)2 and Mn^III(acac)3 complexes, enabling researchers to quantify charge and spin density changes at the metal center [11]. The experimental setup for L-edge XAS of dilute solutions utilizes a partial-fluorescence yield (PFY) detection method with an in-vacuum liquid jet sample injector to overcome radiation damage issues, with spectra collected using a reflective zone plate spectrometer for spatial separation of metal and solvent signals [11].

Electronic (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy measures d-d transitions that correspond to the energy difference between split d-orbital sets. The absorption spectra provide direct information about the crystal field splitting energy (Δ_o) and are influenced by both oxidation and spin states. Charge-transfer bands can also provide insights into metal-ligand bonding interactions [10].

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy is particularly valuable for characterizing paramagnetic complexes, providing information about unpaired electrons, their spin states, and local symmetry. EPR parameters such as g-values and hyperfine coupling constants are sensitive to the electronic structure and coordination environment [10].

Magnetic Measurements

The magnetic properties of transition metal complexes provide direct insight into their spin states through the determination of magnetic moments. Complexes with unpaired electrons exhibit paramagnetism, with magnetic moments that can be correlated to the number of unpaired electrons using the spin-only formula:

μ_eff = √[n(n+2)] Bohr magnetons

where n is the number of unpaired electrons. High-spin complexes typically show higher magnetic moments than low-spin complexes of the same metal ion due to their greater number of unpaired electrons. These measurements are typically performed using SQUID magnetometry or Evans method NMR techniques [15] [13].

Structural Analysis

X-ray Crystallography provides direct evidence of coordination geometry and metal-ligand bond lengths. The latter parameter correlates with spin state, as high-spin complexes typically exhibit longer metal-ligand bonds due to increased electron density in anti-bonding e_g orbitals. For example, high-spin Fe^2+ complexes show Fe-N bond lengths of approximately 2.1-2.2 Å, while low-spin Fe^2+ complexes exhibit shorter bonds of ~1.9-2.0 Å [15] [11].

EXAFS (Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure) can probe local structure around the metal center even in non-crystalline samples, providing bond length and coordination number information that complements crystallographic data [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Electronic Parameter Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specific Utility |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Molecule drawing, descriptor calculation, and chemical property prediction [16] |

| Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) | Java-based cheminformatics library | Chemical structure representation, molecular descriptor calculation, and SAR analysis [16] |

| MayaChemTools | Collection of command-line cheminformatics tools | Molecular descriptor calculation and molecular property prediction [16] |

| L-edge XAS Setup | Partial-fluorescence yield X-ray absorption spectroscopy | Direct probing of metal 3d orbitals and oxidation state determination [11] |

| Dotmatics Vortex | Data visualization and analysis platform | Cheminformatics analyses, including R-group, enumeration, SAR, and matched molecular pairs [17] |

| Molinspiration Cheminformatics | Molecular property calculation and visualization | Calculation of logP, polar surface area, and other molecular properties [18] |

Advanced Protocols

Oxidation State Determination via L-edge XAS

Protocol Objective: Determine the oxidation state and local electronic structure of manganese complexes in solution.

Materials and Equipment:

- Synchrotron radiation source with soft X-ray capability

- In-vacuum liquid jet sample injector with rapid replenishment

- Reflective zone plate (RZP) spectrometer

- CCD camera for fluorescence detection

- Mn(acac)2 and Mn(acac)3 samples in appropriate solvents

Procedure:

- Prepare dilute solutions (~1-10 mM) of Mn^II(acac)2 and Mn^III(acac)3 in appropriate solvents

- Utilize in-vacuum liquid jet for sample delivery to minimize radiation damage

- Scan incident X-ray energy across Mn L-edge (approximately 635-660 eV) in small steps

- At each energy step, detect Mn L_α,β partial fluorescence using RZP spectrometer for spatial separation from solvent oxygen signal

- Normalize fluorescence yield to incident photon flux using zeroth-order reflection from RZP

- Record PFY-XAS spectra for both compounds

- Analyze spectral position and shape differences to determine oxidation state-dependent shifts

- Complement experimental data with quantum-chemical restricted active space (RAS) simulations to quantify charge and spin density distributions

Data Interpretation: The L-edge XAS spectrum of Mn^III(acac)3 will show a distinct blue shift compared to Mn^II(acac)2 due to increased electron affinity in the core-excited states. Theoretical simulations help uncouple effects of oxidation-state changes from geometric influences [11].

Spin State Characterization

Protocol Objective: Determine the spin state of Fe^3+ complexes through magnetic and spectroscopic measurements.

Materials and Equipment:

- SQUID magnetometer or Evans method NMR setup

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Fe^3+ complexes with strong-field (e.g., CN^-) and weak-field (e.g., H_2O) ligands

Procedure:

- Synthesize or obtain Fe^3+ complexes with varying ligand fields

- Measure magnetic susceptibility using SQUID magnetometry across temperature range 2-300 K

- Calculate effective magnetic moment using μeff = 2.828√(χM·T) BM

- Compare experimental magnetic moments with spin-only values for high-spin (5.92 BM) and low-spin (2.12 BM) configurations

- Record UV-Vis spectra to determine Δ_o from d-d transitions

- Correlate magnetic results with spectral data to assign spin states

Data Interpretation: High-spin Fe^3+ complexes will exhibit magnetic moments near 5.9 BM with larger ionic radii, while low-spin complexes show moments near 2.2 BM with smaller ionic radii [15].

Data Visualization and Workflows

Electronic Parameter Determination Workflow

Crystal Field Splitting Diagrams

The electronic structure of transition metal complexes, governed by the interplay of oxidation states, spin states, and coordination geometry, represents a fundamental aspect of inorganic chemistry with broad implications for drug discovery, materials science, and catalysis. This whitepaper has outlined the theoretical foundations, experimental methodologies, and practical protocols for characterizing these key electronic parameters. Advanced spectroscopic techniques like L-edge XAS provide direct probes of metal electronic structure, while magnetic measurements and computational methods offer complementary insights. The integration of these approaches enables researchers to establish structure-property relationships essential for rational design of transition metal complexes with tailored electronic characteristics. As research in this field advances, particularly in areas like redox catalysis and metallodrug development, a deep understanding of these electronic parameters will continue to drive innovation across chemical sciences and biomedical applications.

The interaction between redox activity and ligand field theory represents a cornerstone in understanding the biological chemistry of transition metal complexes. The electronic structures of these complexes, dictated by the ligand field, govern their redox potential, spin-state, and ultimately, their biochemical reactivity. This synergy is critical in biological systems, where metalloenzymes utilize earth-abundant transition metal centers, such as iron, nickel, and zinc, to catalyze essential multielectron transformations including nitrogen fixation, oxygen reduction, and radical-mediated synthesis [19]. The operational principles of these enzymes rely on the close cooperation between the metal ion and surrounding organic, redox-active cofactors, providing a blueprint for bio-inspired catalyst design [19]. In this framework, ligand field theory (LFT) provides the predictive power to understand how the coordination environment—the "material genes" of a complex—controls physical and chemical properties by defining the splitting of metal d-orbitals and their hybridization with ligand orbitals [20]. When combined with the electron-transfer capability of redox-active ligands, this creates a powerful paradigm for designing complexes with tailored reactivity for biological applications, from synthetic catalysis to therapeutic intervention.

Theoretical Foundations

Ligand Field Theory Principles

Ligand field theory elegantly combines the electrostatic crystal field theory with the covalent bonding considerations of molecular orbital theory. Its central tenet is that the local coordination geometry around a transition metal ion splits the energy of its five degenerate d-orbitals. The pattern and magnitude of this splitting are exquisitely sensitive to the identity, geometry, and electronic properties of the surrounding ligands, thereby dictating the complex's magnetic, spectroscopic, and redox properties [20]. In an octahedral field, the d-orbitals split into a higher-energy eg set (dx²−y² and dz²) and a lower-energy t2g set (dxy, dxz, dyz). The energy separation between them is the crystal field splitting parameter, ΔO. Tetragonally distorted octahedral or square planar geometries, common in biological Cu(II) and Ni(II) sites, further lift degeneracies, creating more complex splitting patterns that can be analyzed to predict electronic transitions and spin-states [20].

The strength of the ligand field determines the ground state electronic configuration. Weak-field ligands (e.g., H₂O, Cl⁻) produce a small Δ, favoring high-spin complexes where electron pairing energy exceeds the cost of occupying higher-energy orbitals. Conversely, strong-field ligands (e.g., CN⁻, CO) create a large Δ, stabilizing low-spin complexes. This fundamental distinction has profound biological implications; for instance, the iron in hemoglobin is high-spin, facilitating oxygen binding and release, while the iron in cytochrome c is low-spin, suited for electron transfer [20].

Redox-Active Ligands: From Spectators to Participants

Traditional "redox-innocent" ligands maintain a constant oxidation state during metal-centered redox processes. In contrast, redox-active ligands possess frontier orbitals with energies comparable to metal d-orbitals, allowing them to directly participate in electron transfer events [19]. This blurs the classical assignment of oxidation states, creating a continuum of electronic configurations described as "metal-ligand covalency" or "non-innocence" [19].

The redox activity of a ligand is not an intrinsic property but is actuated by its coordination environment. The geometry imposed by the metal center can switch redox activity on or off. For example, in a square planar field, the ligand's π* orbital is often lower in energy than the metal's dₓ²₋ᵧ² orbital, favoring a ligand-centered radical upon reduction. The same ligand in a trigonal planar geometry may result in a metal-centered reduction because the lower-energy antibonding d-orbitals are now more favorable for the unpaired electron [21]. This principle was dramatically demonstrated with the ubiquitous acetylacetonate (acac) ligand, typically considered redox-inactive. By employing a high-spin Cr(II) center and labile axial ligands, researchers could chemically control electron transfer to the acac ligand, effectively using the ligand field as a switch to trigger metal-ligand redox cooperativity [22].

Table 1: Common Redox-Active Ligand Classes and Their Properties

| Ligand Class | Key Redox Unit | Oxidized Form | Reduced Form | Biological/Synthetic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| o-Diimines | α-Diimine (e.g., bipyridine, phenanthroline) | Diimine | Diimine radical anion | Electron reservoirs in nickel catalysis [21] [23] |

| o-Quinones | o-Benzoquinone | Quinone | Semiquinone / Catecholate | Models for quinone cofactors in enzymes [19] |

| Amidophenolates | o-Iminobenzoquinone | Iminoquinone | Iminosemiquinonate / Amidophenolate | Used in Zr/Ti complexes for oxidative addition [19] |

| Verdazyls | Tetrazine ring | Verdazyl radical | Anionic tetrazine | Magnetic materials and electronic lability studies [24] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Probing Electronic Structure

A multi-technique approach is essential to decipher the complex electronic structures of complexes with redox-active ligands, where the oxidation state is ambiguous.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a primary tool for characterizing redox activity. Complexes with redox-active ligands often exhibit sequential, ligand-centered one-electron reductions or oxidations at defined potentials. CV reveals the thermodynamic feasibility of electron transfers and the stability of redox states. For instance, systematic CV of bidentate N-ligand nickel complexes shows that complexation shifts reduction potentials positively and narrows differences between ligands, providing crucial benchmarks for catalytic activity [21]. A detailed protocol is provided in Section 3.3.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy is indispensable for characterizing paramagnetic intermediates. The g-values and hyperfine coupling constants (to ligand atoms like ¹⁴N or ¹H) can distinguish between metal- and ligand-centered radicals. For example, reduction of a (iPrbiIm)Ni(II) aryl complex yields a solution whose EPR spectrum shows hyperfine splitting from two nitrogen and two hydrogen atoms, confirming the radical is primarily localized on the bi-imidazoline ligand [21].

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) and Magnetic Circular Dichroism (XMCD) provide element-specific information about oxidation state and local geometry. At synchrotron sources like the ALBA beamline, XAS can probe the metal K-edge, while XMCD is highly sensitive to the metal's spin and oxidation state, helping to resolve metal-ligand covalency [24].

X-ray Crystallography offers the most direct structural evidence. Elongation of formal C–O or C–N bonds in ligands like acetylacetonate or diimines upon reduction is a classic signature of ligand-centered redox chemistry, as population of antibonding π* orbitals weakens these bonds [22].

Computational Analysis with Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations are a critical partner to experiment. However, the strong electron correlation and nearly degenerate electronic states in these systems present a significant challenge [23]. The choice of the exchange-correlation functional is paramount. Studies on tris(diimine) iron complexes show that spin-state energy splittings often depend linearly on the amount of exact exchange in the functional [23]. A common pitfall is convergence to a local minimum that does not represent the global minimum electronic structure, sometimes detectable by an anomalous dependence of spin-state energetics on the exact exchange admixture [23]. A robust protocol involves testing multiple functionals, validating results against spectroscopic data (e.g., EPR hyperfine couplings), and carefully analyzing molecular orbitals and spin densities to assign the correct electronic configuration.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry of Redox-Active Complexes

This protocol outlines the procedure for characterizing the redox properties of a transition metal complex with a suspected redox-active ligand, adapted from methodologies in the search results [21] [24].

Objective: To determine the redox potentials, reversibility, and ligand-centered nature of electron transfer processes in a target complex.

Materials and Reagents:

- Electrochemical Cell: A standard three-electrode cell.

- Working Electrode: Platinum disk electrode (e.g., 2 mm diameter).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Pseudo-Reference Electrode: Silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl).

- Potentiostat: Standard commercial instrument.

- Solvent: High-purity, anhydrous acetonitrile (CH₃CN) or tetrahydrofuran (THF).

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate ([nBu₄N][PF₆]). Ensure this is thoroughly dried and free of contaminants.

- Internal Potential Reference: Ferrocene (Fc).

- Analyte: Purified transition metal complex (e.g., Ni, Zn, or Fe complex with a redox-active ligand).

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the platinum working electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) on a microcloth, followed by rinsing with purified solvent and drying.

- Solution Preparation: In an inert atmosphere glovebox, prepare the electrochemical solution. Dissolve the supporting electrolyte ([nBu₄N][PF₆]) in the solvent (e.g., CH₃CN) to a concentration of 0.1 M. Add the analyte complex to a concentration of approximately 1-2 mM. Finally, add a small amount (~0.5 mM) of ferrocene as an internal standard.

- Instrument Setup: Transfer the solution to the electrochemical cell, ensuring an oxygen-free environment. Assemble the three-electrode system and connect to the potentiostat.

- Data Acquisition: Run cyclic voltammetry scans over a suitable potential window (e.g., -2.0 V to +1.0 V vs. Fc⁺/⁰ initial scan). Use a moderate scan rate (e.g., 100 mV/s) to identify redox events. For each observed wave, perform scans at multiple rates (50, 100, 200 mV/s) to assess reversibility (i.e., peak current ratio iₚc/iₚa ≈ 1 and ΔEₚ ~ 59/n mV). For quasi-reversible or irreversible processes, analysis of scan rate dependence can provide kinetic information.

- Data Analysis:

- Referencing: Reference all measured potentials to the ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc⁺/⁰) couple, which is defined as 0 V.

- Potential Reporting: Report formal potentials (E₁/₂) as the average of the anodic and cathodic peak potentials for reversible couples: E₁/₂ = (Epa + Epc)/2.

- Ligand-Centered Assignment: Compare the CV of the metal complex to the CV of the free ligand. A shift to more positive reduction potentials (or more negative oxidation potentials) upon metal binding, along with spectroscopic evidence, supports ligand-centered redox activity.

Diagram 1: CV Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for conducting cyclic voltammetry analysis of redox-active complexes, highlighting the critical use of an internal standard and multi-scan rate analysis.

Biological Signaling and Therapeutic Context

The Biological "Redox Code"

Biological systems operate under a sophisticated set of principles known as the "redox code" [25]. This code governs how redox reactions are organized to support life:

- Bioenergetic Organization: Catabolism and anabolism are organized through high-flux NADH and NADPH systems, which operate near equilibrium with central metabolic fuels.

- Sulfur Switches: Macromolecular structure and function are linked to these pyridine nucleotide systems via kinetically controlled redox switches on cysteine and methionine residues in the proteome.

- Spatiotemporal Signaling: Activation/deactivation cycles of H₂O₂ production, linked to NADH/NADPH systems, support redox signaling for differentiation and development.

- Adaptive Networks: Integrated redox networks, from microcompartments to entire organisms, form an adaptive system that dynamically responds to the environment [25].

In this framework, reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), act as second messengers. They trigger cellular signals through the reversible oxidation of critical protein cysteine residues, controlling processes from embryogenesis to neural activity [25]. The fine-tuned balance between oxidant production and removal—redox homeodynamics—is essential. Deviation towards excessive oxidants causes oxidative distress, associated with aging and disease, while inadequate oxidant levels impair signaling, leading to reductive distress [25].

Metalloenzymes and Redox-Active Cofactors

Nature masterfully employs redox-active ligands in metalloenzyme catalysis. The active sites of many enzymes feature earth-abundant metals (Fe, Ni, Mn, Cu) coordinated by organic cofactors that can undergo redox changes, enabling multielectron transformations that are otherwise challenging for metal centers that prefer one-electron steps [19]. For instance, in the radical SAM enzyme superfamily, a [4Fe-4S]⁺ cluster, coordinated by a redox-active cysteine residue, interacts with S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to generate a highly oxidizing 5'-deoxyadenosyl radical that initiates diverse reactions including DNA repair and enzyme activation. This exemplifies perfect synergy between a transition metal-sulfur cluster and an organic cofactor to achieve controlled radical biochemistry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Redox-Active Complexes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Bidentate N-Ligands (e.g., Bi-oxazoline, Bi-imidazoline, Bipyridine) | Provide tunable coordination geometry and electronic properties; can be redox-active. | Used to stabilize nickel radical intermediates in cross-coupling catalysis [21]. |

| Acetylacetonate (acac) & Derivatives | Common chelating β-diketonate ligand; can be rendered redox-active via strong ligand field. | Actuated to redox-activity in high-spin Cr(II) complexes with labile axial ligands [22]. |

| Verdazyl-based Ligands (e.g., dipyvdH) | Intrinsic stable radical ligands that can be reduced; used to study magnetic exchange and electronic lability. | Form complexes with Zn, Ni, Fe, Co exhibiting ligand-centered oxidation and spin crossover [24]. |

| Chemical Reductants (e.g., KC8, CoCp*₂) | Strong reducing agents used to generate reduced complexes for studying electron transfer. | KC8 with 18-crown-6 used to reduce (iPrbiIm)Ni(II) complexes, generating ligand radicals [21]. |

| Chemical Oxidants (e.g., [Cp₂Fe][PF₆], PhICl₂) | One- and two-electron oxidants used to probe oxidative electron transfer and reactivity. | [Cp₂Fe][PF₆] oxidizes Zr amidophenolate complexes, triggering C–C reductive elimination [19]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (CD₃CN, THF-d₈) | For NMR characterization of diamagnetic complexes and monitoring ligand exchange dynamics. | Used to observe dynamic pyridine exchange in [Cr(acac)₂(py)₂] complexes by ¹H-NMR [22]. |

| Tetraalkylammonium Salt Electrolytes (e.g., [nBu₄N][PF₆]) | Electrolyte for non-aqueous electrochemistry (CV); provides ionic conductivity without reacting. | Standard 0.1 M electrolyte for measuring redox potentials in CH₂Cl₂ or THF [21] [22]. |

The integration of ligand field theory with the concept of redox-active ligands provides a profound and predictive framework for manipulating the electronic structure of transition metal complexes. This understanding is fundamental to deciphering biological redox regulation and for designing next-generation catalytic and therapeutic agents. The "redox code" in biology underscores the complexity and sophistication of these systems in maintaining homeodynamics [25]. Future advances will rely on the continued development of sophisticated spectroscopic and computational methods to precisely characterize metal-ligand cooperativity. Furthermore, the deliberate design of ligand fields to actuate redox activity in common, inexpensive ligands—as demonstrated with acetylacetonate [22]—opens a vast arena for creating new earth-abundant catalysts that mimic the multielectron efficiency of metalloenzymes. Integrating these principles holds the key to innovations in green chemistry, targeted redox therapies, and synthetic biology.

The electronic structure of transition metal complexes, characterized by their incompletely filled d-orbitals, is the cornerstone of their unique reactivity. Unlike main-group elements, the diverse electron arrangements available to transition metals such as platinum, palladium, and nickel enable them to facilitate a wider array of chemical transformations, including the fundamental reaction known as oxidative addition [26] [27]. In this process, a molecule A–B adds to a metal center, breaking the A–B bond and forming two new metal-ligand bonds (M–A and M–B). This reaction is a critical step in numerous catalytic cycles, including cross-coupling and hydrogenation [28].

For decades, textbook descriptions have asserted that oxidative addition proceeds primarily through a mechanism where the electron-rich metal center donates electrons into the σ* antibonding orbital of the substrate, facilitating bond cleavage and resulting in a formal increase in the metal's oxidation state [26] [29]. This paradigm has long guided catalyst design, favoring electron-dense metal complexes to promote this key step. However, recent discoveries have challenged this conventional understanding, revealing previously unrecognized pathways that operate under different electronic principles. This whitepaper explores these groundbreaking findings, which are reshaping fundamental chemical theory and expanding the toolbox for researchers and drug development professionals designing new catalytic syntheses.

A Paradigm Shift: Electron Flow Reversal in Oxidative Addition

Discovery of a Heterolytic Pathway

A landmark study from Penn State University has uncovered a novel mechanism for the oxidative addition of hydrogen (H₂) to palladium (Pd) and platinum (Pt) centers [26] [29]. Contrary to the established model, this pathway does not require an electron-rich metal. Instead, the researchers demonstrated that the reaction can be initiated by electron transfer from the organic substrate to the metal center, a process known as heterolysis [26].

Using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to monitor reactions in real-time, the team observed a key intermediate that forms when electron-deficient Pd(II) or Pt(II) complexes are exposed to H₂ gas. This intermediate provides direct evidence that the first step involves H₂ donating electrons to the metal, prior to the system relaxing into a final product indistinguishable from that formed via the traditional oxidative addition route [26] [29]. This finding elegantly explains why certain oxidative additions are paradoxically accelerated by electron-deficient metal complexes—a phenomenon that lacked a satisfactory explanation under the old model.

Implications for Catalyst Design

This discovery fundamentally expands the conceptual framework for oxidative addition. It demonstrates that the same net reaction can be achieved through two distinct electronic pathways, effectively adding a "new play" to the transition metal chemistry playbook [26]. For chemists designing catalysts for pharmaceutical synthesis or other fine chemical applications, this opens new strategic avenues. It suggests that electron-deficient metals, previously overlooked for such steps, could be strategically employed to activate specific substrates, potentially leading to more efficient or selective catalytic processes [29]. Furthermore, this new understanding could inform the design of catalysts for challenging environmental applications, such as breaking down stubborn pollutants [26].

Expanding the Scope: Oxidative Addition Across Diverse Systems

Recent research has extended the study of oxidative addition beyond traditional contexts, revealing its occurrence on novel catalytic surfaces and with non-traditional substrates.

On Palladium Nanoparticles

Oxidative addition has traditionally been studied in molecular Pd(0) complexes. However, a 2024 computational study pioneered the exploration of this reaction on the surfaces of palladium nanoparticles (NPs), which are common active species in "cocktail"-type catalytic systems [30]. Using density functional theory (DFT) modeling and semi-empirical metadynamics simulations, the study analyzed the oxidative addition of phenyl bromide to Pd NPs.

The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Insights from Oxidative Addition to Palladium Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Active Site | Edges of (1 1 1) facets [30] | Reaction is localized to low-coordinate, high-energy sites on the nanoparticle surface. |

| Kinetic Feasibility | Activation free energy ≤ 11 kcal mol⁻¹ [30] | The reaction is kinetically facile at ambient temperatures. |

| Thermodynamics | Thermodynamically favorable [30] | The process drives toward the product, supporting its role in catalytic cycles. |

| Post-Reaction Mobility | Phenyl group migrates along edges; Bromine atom remains tightly bound to (1 0 0) facets [30] | Reveals dynamic behavior of fragments after bond cleavage, which could influence subsequent catalytic steps. |

This work underscores that oxidative addition is not limited to molecular complexes and must be considered in the broader context of dynamic catalytic systems where multiple, interconverting Pd species may be present [30].

The Conceptual Frontier: Reductive Addition

The very definition of oxidative addition is being challenged by work with highly electropositive substrates. A 2025 study investigated reactions of a Zn–Zn bonded complex, CpZnZnCp, with main group carbene analogues (e.g., of silicon, aluminum) [28]. According to the IUPAC definition of oxidation state, the addition of the Zn–Zn bond to these elements—which are less electronegative than zinc—constitutes a formal reductive addition [28].

This research proposes a continuum of redox outcomes for such addition processes, spanning oxidative, redox-neutral, and reductive, depending on the relative electronegativities of the atoms involved [28]. This nuanced view moves beyond a binary classification and provides a deeper framework for understanding how bonds form and break across a wide spectrum of elemental combinations.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Probing an Alternative Oxidative Addition Pathway with H₂

Objective: To demonstrate the heterolytic oxidative addition of H₂ to electron-deficient Pd/Pt centers [26] [29].

Materials:

- Transition Metal Precursors: Pd(II) or Pt(II) complexes, specifically selected for their electron-deficient character [26].

- Substrate: Hydrogen gas (H₂) [26].

- Solvent: Anhydrous, deoxygenated solvent appropriate for the metal complexes (e.g., benzene, toluene) [26] [28].

- Monitoring Instrument: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer [26].

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: The Pd(II) or Pt(II) complex is dissolved in the anhydrous, deoxygenated solvent within an NMR tube equipped with a J. Young valve or under an inert atmosphere in a glovebox [26].

- Gas Introduction: The atmosphere above the solution is replaced with pure H₂ gas [26].

- Reaction Monitoring: The NMR tube is placed in the spectrometer, and a time-course series of spectra is acquired at a controlled temperature [26].

- Data Analysis: The NMR spectra are analyzed for changes in chemical shift and the appearance of new resonances. The critical evidence is the observation of a transient intermediate species, characterized by distinct NMR signals, which forms prior to the final product [26] [29].

- Intermediate Characterization: The chemical shifts and properties of this intermediate are consistent with a structure where H₂ has donated electron density to the metal center (heterolysis), supporting the proposed alternative mechanism [26].

Computational Analysis of Oxidative Addition to Nanoparticles

Objective: To characterize the oxidative addition of an aryl halide to the surface of a palladium nanoparticle [30].

Materials:

- Computational Models: Atomistic models of Pd nanoparticles (e.g., Pd₅₅, Pd₇₉, Pd₁₄₀) with defined geometries like truncated octahedrons [30].

- Substrate Model: A single molecule of phenyl bromide (PhBr) [30].

- Software: DFT and semi-empirical quantum chemistry software packages.

Methodology:

- System Preparation: The Pd nanoparticle and PhBr molecule are positioned in a computational cell with periodic boundary conditions or in a cluster model [30].

- Metadynamics Simulations: Employ semi-empirical metadynamics (MTD) simulations (using the GFN1-xTB Hamiltonian) to efficiently explore the reaction pathway. This technique uses a "history-dependent" bias potential to push the system over energy barriers and locate transition states [30].

- Pathway Identification: Analyze MTD trajectories to identify the most probable reaction pathways and the corresponding transition state structures [30].

- Energy Profiling: Perform more accurate Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on the identified stationary points (reactants, transition states, products) to refine the geometry and obtain the final energy profile [30].

- Site Activity Comparison: Compare the activation energies and reaction pathways for different sites on the nanoparticle (e.g., edges, vertices, facets) and against known molecular Pd(0) complexes [30].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Oxidative Addition Mechanistic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the two competing mechanistic pathways for oxidative addition, as revealed by recent research.

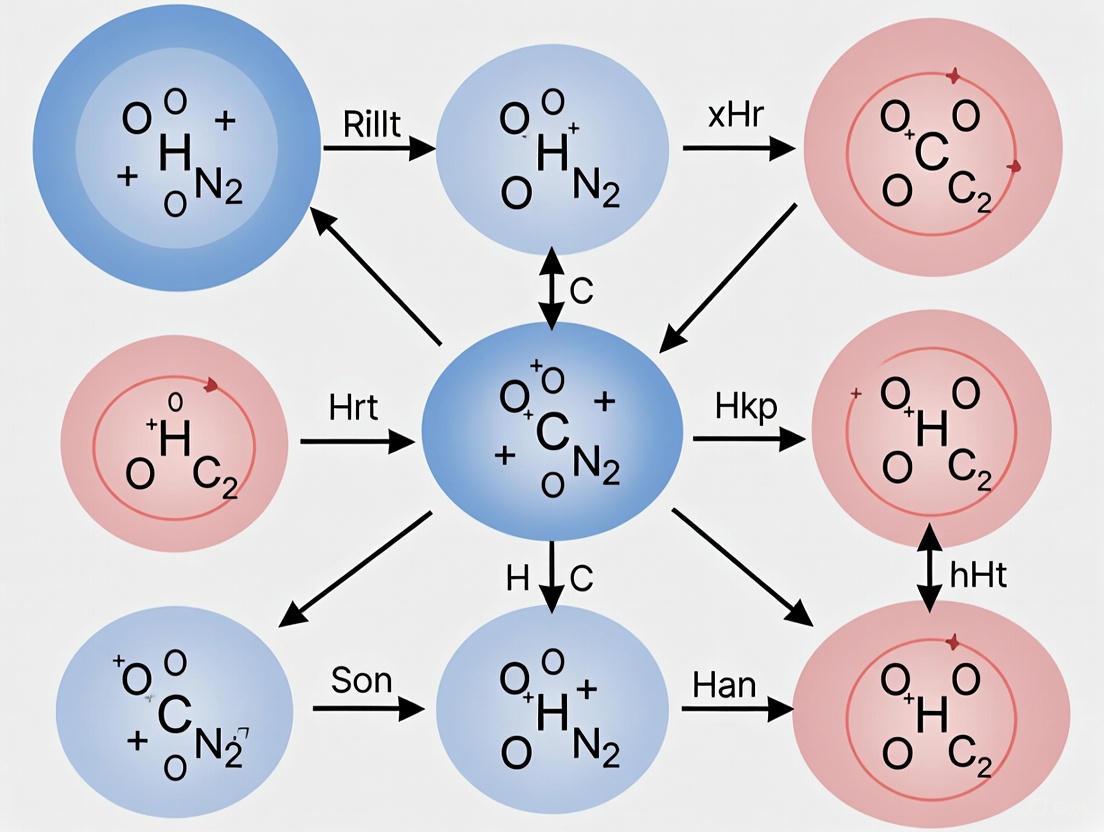

Diagram 1: Two pathways for oxidative addition: conventional (red) and heterolytic (blue).

Experimental Workflow for Mechanistic Elucidation

The experimental and computational approach used to uncover the new heterolytic pathway is summarized below.

Diagram 2: Key steps in the experimental workflow for probing oxidative addition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Oxidative Addition Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role in Research | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium/Platinum Complexes | The central transition metal catalyst for the oxidative addition reaction. Electron-deficient M(II) species were key to discovering the new pathway [26] [29]. | Probing alternative oxidative addition mechanisms [26]. |

| Dihydrogen (H₂) | A fundamental model substrate for oxidative addition studies. Its simple bond structure makes it ideal for mechanistic elucidation [26] [28]. | Oxidative addition to Pd/Pt centers [26]. |

| Aryl Halides (e.g., PhBr) | Common substrates in cross-coupling chemistry. Their oxidative addition is a critical step in many synthetic applications [30]. | Studying OA on Pd nanoparticles [30]. |

| NMR Spectrometer | An essential analytical instrument for monitoring reactions in solution, identifying intermediates, and characterizing products [26]. | Observing heterolysis intermediate in H₂ activation [26]. |

| DFT & Metadynamics Software | Computational tools used to model reaction pathways, locate transition states, and calculate energy profiles for reactions on surfaces and in complexes [30] [28]. | Mapping OA on Pd NPs [30]; Analyzing reductive addition [28]. |

| Zn–Zn Bonded Complex (CpZnZnCp) | A model complex with a bond isolobal to H–H, used to probe the fundamentals of addition reactions with electropositive elements [28]. | Investigating reductive addition to main group elements [28]. |

The recent discoveries in oxidative addition chemistry underscore a dynamic and evolving field. The identification of a heterolytic pathway for H₂ activation, the demonstration of facile oxidative addition on palladium nanoparticle surfaces, and the exploration of the conceptual limits of addition chemistry through reductive processes collectively signal a significant expansion of our understanding of how transition metals mediate bond-breaking and bond-forming events [26] [30] [28].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights are more than academic curiosities. They provide a revised and more nuanced conceptual framework that can guide the rational design of new catalysts. By moving beyond traditional assumptions and leveraging these new mechanistic "plays," scientists can explore unconventional catalytic systems, potentially leading to more efficient, selective, and sustainable synthetic methodologies for pharmaceutical synthesis and beyond. The electronic structure of transition metals continues to offer rich territory for fundamental discovery with direct practical implications.

Computational and Practical Tools: Modeling TMCs for Biomedical Applications

Transition metal complexes (TMCs) represent a cornerstone of modern inorganic chemistry with profound implications across medicine, materials science, and catalysis. Their unique electronic properties, derived from partially filled d-orbitals, govern their reactivity, magnetic behavior, and biological activity. The investigation of TMCs has been revolutionized by computational methodologies that provide atomic-level insights often inaccessible through experimental approaches alone. Density functional theory (DFT), molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) have emerged as indispensable tools for deciphering the structure-property relationships of these sophisticated systems. These computational workhorses enable researchers to predict electronic structures, simulate binding interactions with biological targets, and model time-dependent behavior in complex environments. Within the broader context of electronic structure research, these methods form a complementary toolkit that bridges quantum mechanical principles with macroscopic observables, driving innovation in rational drug design and advanced materials development.

Density Functional Theory: Deciphering Electronic Structure

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Density functional theory has become the predominant quantum mechanical method for investigating the electronic structure of transition metal complexes due to its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy. DFT operates on the fundamental principle that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines all properties of a many-electron system, bypassing the need for computing the complex many-electron wavefunction. For TMCs, this approach enables the calculation of crucial electronic properties including orbital energies, electron density distributions, and spin states that dictate reactivity and function.

The application of DFT to transition metal complexes requires careful selection of exchange-correlation functionals and thorough methodological validation. The full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method, as implemented in the WIEN2k code, is widely recognized as one of the most accurate approaches for calculating the electronic structure of crystalline solids containing transition metals [31]. This method expands electronic wave functions, charge density, and crystal potential using spherical harmonics within atomic-centered spheres and plane waves in the interstitial region, providing high precision for complex TMC systems. For molecular TMCs, popular alternatives include the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method and Gaussian-type orbital approaches implemented in codes such as Gaussian and ORCA.

The treatment of exchange-correlation effects presents particular challenges for TMCs due to strongly correlated d-electrons. Standard generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals like PBE often require augmentation for improved accuracy. Common strategies include:

- DFT+U: Incorporates an on-site Coulomb interaction (Hubbard U parameter) to better describe localized d-electrons [31]

- meta-GGA functionals: Utilize the kinetic energy density for improved exchange-correlation treatment

- Hybrid functionals: Include a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0)

- Modified Becke-Johnson (mBJ) potential: Provides accurate band gaps without the computational cost of hybrids [31]

Table 1: Exchange-Correlation Functionals for TMC Studies

| Functional Type | Representative Examples | Best Use Cases | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE, PBEsol | Structural optimization, metallic systems | Underestimates band gaps |

| GGA+U | PBE+U, PBEsol+U | Systems with localized d-electrons | U parameter must be carefully chosen |

| Hybrid | B3LYP, PBE0, HSE06 | Electronic excitation, molecular properties | Increased computational cost |

| mBJ | mBJ, TB-mBJ | Band gaps, optical properties | Primarily for periodic systems |

Application to Transition Metal Complex Electronic Structure

DFT provides profound insights into the electronic structure of transition metal complexes, enabling prediction of properties directly relevant to their applications. In a comprehensive DFT investigation of MoO₂ polymorphs, researchers demonstrated how local structural arrangements dramatically influence electronic behavior [31]. The study revealed that while monoclinic (P2₁/c) and tetragonal (P4₂/mnm) phases of MoO₂ exhibit metallic character, the hexagonal polymorph (P6₃/mmc) undergoes a metal-to-semiconductor transition with an computed indirect band gap of 0.635 eV. This fundamental transition was attributed to local Mo 4d ordering, highlighting how DFT can uncover subtle structure-property relationships in TMCs [31].

For molecular qubits based on transition metal complexes, DFT and multiconfigurational methods enable the prediction of key magnetic properties essential for quantum information science. In the study of pseudo-tetrahedral complexes for molecular qubit applications, researchers calculated zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameters and energy gaps between electronic spin states [32]. These parameters determine the suitability of complexes as qubits, with preferred |D| values below 20 GHz for compatibility with X-band EPR spectroscopy. The investigation compared complexes with different metal centers (Ti, V, Cr, Mo, W) possessing d² electronic configurations, finding that Ti(II) and V(III) complexes offered potentially superior electronic stability compared to the Cr(IV) prototype [32].

The versatility of DFT extends to predicting redox properties of TMCs, as demonstrated in a study generating a comprehensive dataset of 2,267 iron complexes [33]. By combining tight-binding DFT with standard DFT calculations, researchers accurately computed redox potentials for Fe(II)/Fe(III) couples, subsequently using this data to train graph neural networks for property prediction [33]. This integrated approach exemplifies how DFT serves as the foundation for machine learning applications in TMC research.

Diagram 1: DFT Calculation Workflow for TMCs (55 characters)

Experimental Protocol: DFT Calculation for TMC Electronic Structure

Protocol Title: DFT Investigation of Electronic Structure in Transition Metal Oxides

Based on: Computational approach from "Density functional theory investigation of the metallic-to-semiconductor transition in MoO₂ polymorphs" [31]

Software Requirements: WIEN2k code (version 24.1 or newer) OR Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ORCA, or Gaussian

Computational Parameters:

- Exchange-correlation functional: GGA-PBE, GGA-PBEsol, GGA-PBE+U, or mBJ

- k-point mesh: Monkhorst-Pack grid with minimum 8×8×8 for solids

- Basis set: FP-LAPW (WIEN2k) OR plane-wave cutoff ≥500 eV (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO)

- Convergence criteria: Energy change < 0.1 mRy, force < 2 mRy/bohr

Procedure:

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain crystal structure (monoclinic P2₁/c, tetragonal P4₂/mnm, hexagonal P6₃/mmc for MoO₂) from Materials Project database or crystallographic data

- Geometry Optimization:

- Perform full relaxation of atomic positions with fixed lattice parameters

- Use force convergence criterion of 2.0 mRy/bohr

- For molecular TMCs, optimize all structural parameters

- Electronic Structure Calculation:

- Conduct self-consistent field (SCF) calculations with selected functional

- Include spin-orbit coupling if investigating magnetic properties

- For DFT+U, employ Hubbard U parameter (e.g., U = 4.38 eV for Mo 4d states)

- Property Analysis:

- Compute band structure along high-symmetry points in Brillouin zone

- Calculate density of states (DOS) and partial DOS (pDOS)

- Determine optical properties via dielectric function calculation

- Validation: Compare calculated lattice parameters, bond lengths, and electronic properties with experimental data where available

Molecular Docking: Predicting Biomolecular Interactions

Theoretical Foundations of Protein-Ligand Recognition

Molecular docking stands as a pivotal element in computer-aided drug design, consistently contributing to advancements in pharmaceutical research involving transition metal complexes [34]. At its core, molecular docking employs computational algorithms to identify the optimal binding mode between two molecules, most commonly a protein and a small molecule ligand. For TMCs with therapeutic potential, docking predicts how these inorganic compounds interact with biological targets, providing insights into their mechanism of action and facilitating rational drug design.

The physical basis of molecular docking rests on the principles of molecular recognition driven by non-covalent interactions [34]. The four primary interaction types include:

- Hydrogen bonds: Polar electrostatic interactions (D—H⋯A) with strength ~5 kcal/mol

- Ionic interactions: Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged pairs

- Van der Waals interactions: Nonspecific forces from transient dipoles (~1 kcal/mol)

- Hydrophobic interactions: Entropy-driven aggregation of nonpolar molecules

The stability of protein-ligand complexes is governed by the Gibbs binding free energy (ΔGbind = ΔH - TΔS), where enthalpic contributions arise from formed chemical bonds and entropic contributions reflect changes in system randomness [34]. Molecular docking algorithms aim to predict the bound association state that minimizes this free energy, effectively identifying the most stable binding configuration.

Three conceptual models describe molecular recognition mechanisms [34]:

- Lock-and-key model: Rigid complementarity between protein and ligand

- Induced-fit model: Conformational changes in protein upon ligand binding

- Conformational selection: Ligand binding selectively to pre-existing protein conformations

For TMCs, the coordination geometry and ligand exchange kinetics introduce additional complexity to docking protocols, as the metal center may participate in coordinate covalent bonding with biological targets.

Application to Transition Metal Complex Drug Candidates

Molecular docking has proven invaluable for evaluating the therapeutic potential of transition metal complexes, particularly in predicting their interactions with biological macromolecules. Studies have demonstrated that organo-ruthenium(II) complexes exhibit stronger binding interactions with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and calf thymus DNA (CT-DNA) compared to their free ligands [35]. This enhanced binding correlates with increased cytotoxic effects observed in cancer cells, highlighting how docking can predict biological activity of TMCs.

In antimalarial research, molecular docking combined with DFT calculations has identified promising copper(II), nickel(II), cobalt(II), and zinc(II) complexes with benzaldehyde and thiosemicarbazone derivatives [35]. These studies revealed that zinc(II) complexes containing 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde derivatives showed particularly high efficacy against malaria and oxidative stress. Docking simulations further confirmed superior antimalarial activity of the metal complexes compared to ligands alone, demonstrating how computational methods guide the selection of promising therapeutic candidates [35].

For neurological disorders, docking studies have explored how ruthenium(III) complexes with azole ligands inhibit Aβ amyloid aggregation in Alzheimer's disease [36]. These complexes displace chloride ligands to coordinate with histidine residues at positions 13 and 14 of the Aβ peptide, while the organic ligands form additional hydrophobic contacts and hydrogen bonds [36]. Such detailed interaction models inform the rational design of metal-based therapeutics with specific molecular targets.

Table 2: Molecular Docking Applications for Transition Metal Complexes

| Therapeutic Area | Target | TMC Types | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | DNA, BSA | Ru(II), Pt(II) | Stronger DNA/protein binding than organic ligands |

| Malaria | Unknown target | Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II), Zn(II) | Zinc complexes most effective; enhanced vs. ligands |

| Alzheimer's | Aβ peptide | Ru(III) azole complexes | Coordination to His13/14 inhibits aggregation |

| Parasitic infections | Trypanothione reductase | Au(I/III) NHC complexes | Enzyme inhibition predicted |

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Docking of TMCs with Biological Targets

Protocol Title: Molecular Docking of Transition Metal Complexes with Protein Targets

Based on: Methodology from "Docking strategies for predicting protein-ligand interactions" and medicinal applications from transition metal complex research [34] [35] [36]

Software Requirements: Docking software (AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide), molecular visualization (PyMOL, Chimera), force field with metal parameters

Preparation Steps:

- Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structure from Protein Data Bank (PDB)

- Remove water molecules and heteroatoms (except essential cofactors)

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges

- Define binding site based on experimental data or binding cavity detection

- TMC Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structure from synthesis or database

- Assign proper bond orders and formal charges

- Determine coordination geometry and oxidation state

- Parameterize metal center and coordinate bonds for force field

Docking Procedure:

- Grid Generation:

- Define search space encompassing binding site

- Set grid dimensions (e.g., 20×20×20 Å) with 1.0 Å spacing

- Center grid on known binding site or predicted active site

Docking Execution:

- Run multiple docking simulations (minimum 10 runs)

- Set exhaustiveness parameter ≥8 for improved sampling

- Generate multiple poses per ligand (minimum 10 poses)

Pose Analysis and Selection:

- Cluster results based on RMSD (typically 2.0 Å cutoff)

- Analyze binding interactions (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts, metal coordination)

- Select poses based on complementarity and interaction energy

Validation:

- Redock known crystallographic ligands to validate protocol

- Compare calculated RMSD with experimental reference (<2.0 Å acceptable)

Diagram 2: Molecular Docking Workflow (41 characters)

Molecular Dynamics: Modeling Dynamic Behavior

Methodological Approaches for Transition Metal Complexes