Electronic Density of States Calculation: From Fundamental Theory to Machine Learning Advances

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electronic density of states (DOS) calculation methods, bridging traditional first-principles approaches and cutting-edge machine learning techniques.

Electronic Density of States Calculation: From Fundamental Theory to Machine Learning Advances

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electronic density of states (DOS) calculation methods, bridging traditional first-principles approaches and cutting-edge machine learning techniques. It covers foundational concepts like Van Hove singularities and effective mass, explores computational methodologies from Density Functional Theory to universal neural network models, addresses optimization strategies for accurate simulations, and validates approaches through performance benchmarking. The content specifically highlights implications for predicting material properties relevant to biomedical applications and drug development research.

Understanding Electronic Density of States: Core Concepts and Physical Significance

The Electronic Density of States (DOS) is a fundamental concept in materials science and computational chemistry that quantifies the number of electronically allowed quantum states at each energy level within a material. It serves as a cornerstone for understanding and predicting key electronic, optical, and thermal properties, thereby enabling targeted material design for applications ranging from semiconductors to drug development. This in-depth technical guide explores the core theoretical principles of DOS, details the computational methodologies for its calculation—from traditional ab-initio methods to modern machine-learning approaches—and provides a detailed analysis of its critical role in materials research through specific experimental protocols and quantitative data.

The Electronic Density of States (DOS) is a foundational concept in solid-state physics and quantum chemistry, providing a critical bridge between the atomic structure of a material and its macroscopic electronic properties. Formally, it is defined as a distribution function that describes the number of electronic states per unit volume per unit energy interval. The fundamental equation for the Total Density of States (TDOS) is given by:

[N(E) = \sumi \delta(E-\epsiloni)]

where (\epsilon_i) denotes the one-electron energy of the (i)-th quantum state, and the (\delta)-function is typically broadened in practical computations to a Lorentzian or Gaussian function for graphical representation and analysis [1]. Conceptually, a high DOS at a specific energy level indicates a high number of available electronic states at that energy. This simple concept underpins the explanation of complex phenomena; for instance, the presence of a band gap is directly observed as an energy region where the DOS is zero, and the conductivity of a material is heavily influenced by the DOS near the Fermi level.

The utility of DOS extends far beyond the total distribution. Through a Mulliken population analysis, the total DOS can be projected onto specific atoms, atomic orbitals, or groups of basis functions to create a Projected Density of States (PDOS). This decomposition allows researchers to determine the atomic or orbital character of the electronic bands. The Gross Population Density of States (GPDOS) for a specific function (\chi_\mu), for example, is calculated as:

[GPDOS: N\mu (E) = \sumi GP{i,\mu} L(E-\epsiloni)]

where (GP{i,\mu}) is the gross population of function (\chi\mu) in orbital (\phi_i) [1]. Furthermore, the Overlap Population Density of States (OPDOS) analyzes bonding interactions by revealing energies at which the interaction between two orbitals is bonding (positive values) or anti-bonding (negative values) [1]. These analyses transform the DOS from a simple distribution into a powerful tool for dissecting the chemical nature and bonding interactions within a material.

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

The accurate calculation of the Density of States is a central task in computational materials science. The methodologies can be broadly categorized into traditional electronic-structure methods and emerging machine-learning-based approaches.

1Ab-InitioCalculation Workflow

Traditional DOS calculations rely on solving the quantum mechanical equations for a system of electrons, often using Density Functional Theory (DFT). The following workflow, commonly implemented in codes like VASP, outlines the core protocol [2]:

- Geometry Optimization: The atomic positions and lattice parameters of the material's unit cell are first relaxed to their ground-state configuration to ensure the calculation is performed on a stable structure.

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: An accurate electronic ground state is computed. The output includes the charge density and the Kohn-Sham eigenvalues, which are the (\epsilon_i) in the DOS formula.

- Non-SCF DOS Calculation: A final calculation is performed using a finer k-point mesh (for periodic systems) to interpolate the bands and obtain a high-resolution DOS. The delta functions in the TDOS equation are broadened using a smearing function (e.g., Gaussian or Lorentzian) with a user-specified width parameter (a typical default is 0.25 eV) [1].

- Post-Processing and Analysis: The resulting output files (e.g.,

vasprun.xmlin VASP) are analyzed to extract and plot the TDOS and PDOS. Tools like sumo are specifically designed for this purpose, generating publication-quality plots directly from VASP output files [2].

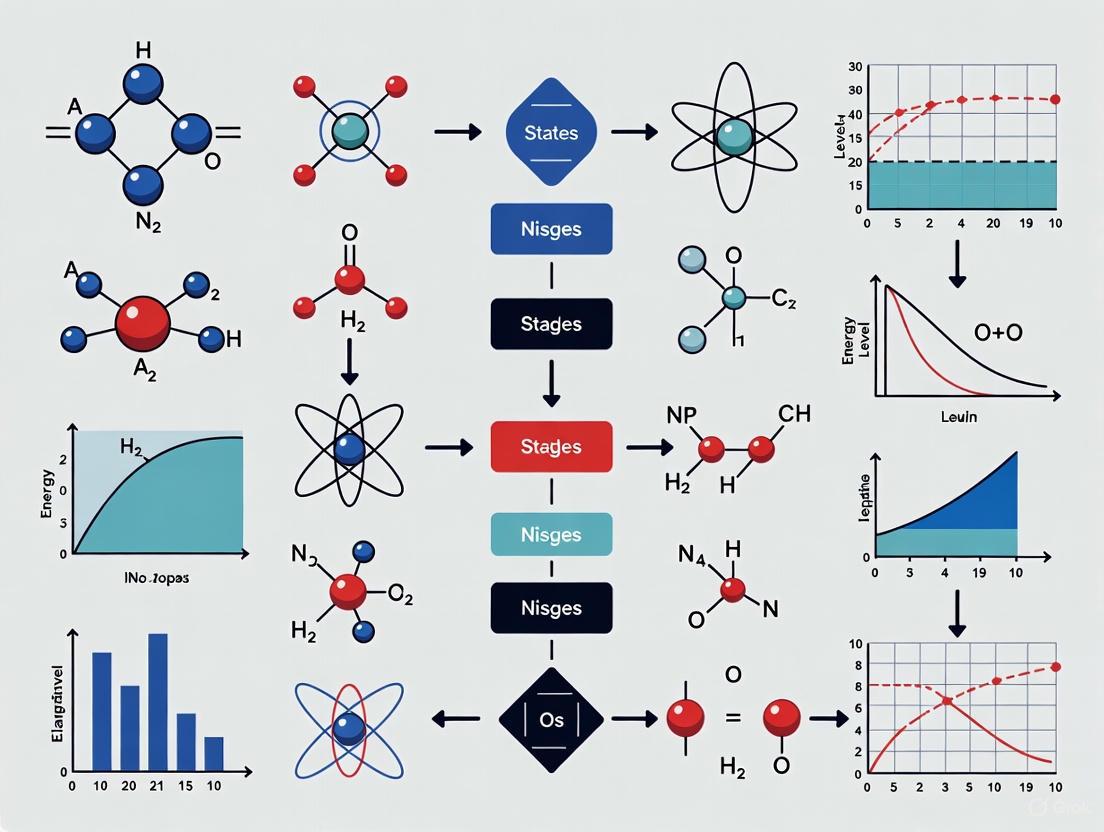

The following diagram illustrates this computational workflow and the key analyses it enables:

Machine Learning Approach with PET-MAD-DOS

A paradigm shift in DOS calculation is emerging with universal machine learning models. The PET-MAD-DOS model is a state-of-the-art example, demonstrating that ML can predict the DOS directly from atomic structures at a fraction of the computational cost of ab-initio methods [3].

- Model Architecture: PET-MAD-DOS is based on the Point Edge Transformer (PET) architecture, a transformer-based graph neural network. A key feature is that it does not enforce rotational constraints but learns equivariance through extensive data augmentation [3].

- Training Dataset: The model is trained on the Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD) dataset. This dataset is compact but highly diverse, containing about 100,000 structures including 3D crystals, 2D materials, randomized structures, surfaces, clusters, molecular crystals, and molecular fragments [3].

- Experimental Protocol for Validation: The generalizability of PET-MAD-DOS was tested using a hold-out test set from MAD and several external datasets (MPtrj, Matbench, SPICE, MD22, etc.). The model's predictions were compared to DFT-computed DOS, and the error was measured as the root-mean-square error (RMSE) in units of (\mathrm{eV^{-0.5}electrons^{-1}state}) [3].

- Fine-Tuning Protocol: For specific material systems, the universal PET-MAD-DOS model can be fine-tuned using a small amount of system-specific data. This process yields models that achieve accuracy comparable to, and sometimes better than, models trained exclusively on that specific data (bespoke models) [3].

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for DOS Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [2] | Ab-initio Electronic Structure | Periodic Systems (Crystals, Surfaces) | Industry-standard DFT code for precise DOS calculation. |

| sumo [2] | Band Structure & DOS Plotting | Post-Processing of VASP Output | Generates publication-quality DOS and band structure plots. |

| gnuplot [2] | Data Plotting | General-purpose Visualization | A flexible tool for plotting DOS data from ASCII output files. |

| dos (ADF Module) [1] | DOS Analysis | Molecular & Cluster Calculations | Computes TDOS, PDOS, OPDOS from ADF calculations. |

| PET-MAD-DOS [3] | ML-based DOS Prediction | High-Throughput Material Screening | Fast, universal DOS predictor for molecules and materials. |

Quantitative Data and Property Analysis

The DOS is not merely a theoretical output; it provides direct quantitative insights into a material's electronic properties. The following table summarizes key properties derivable from the DOS.

Table 2: Material Properties Derived from the Electronic Density of States

| Property | Mathematical Relation to DOS | Physical Significance | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Gap | Energy interval where (N(E) = 0) | Fundamental for electronic conductivity; distinguishes metals, semiconductors, and insulators. | Semiconductor device design [3]. |

| Electronic Heat Capacity ((C_v)) | (C_v(T) \propto \int N(E) \frac{\partial f(E,T)}{\partial T} E dE) | Determines how the electron gas contributes to a material's heat capacity at different temperatures. | Modeling high-temperature processes [3]. |

| Charge Density Distribution | — | Inferred from PDOS; reveals charge localization and atomic contributions to bonding. | Analyzing catalytic activity and chemical reactivity. |

| Fermi Level ((E_F)) | (\int{-\infty}^{EF} N(E) dE = n_{electrons}) | The energy level at which the electron occupation probability is 1/2 at 0 K. Critical for conductivity. | Predicting metallic behavior. |

| Optical Absorption | (\propto N(E)N(E+\hbar\omega)) | Related to joint DOS between occupied and unoccupied states; determines which light frequencies are absorbed. | Photovoltaic and optoelectronic material design. |

To validate the accuracy of ML-predicted DOS in practical research, ensemble-averaged properties can be computed from molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories. In a recent study, the electronic heat capacity of three systems—lithium thiophosphate (LPS), gallium arsenide (GaAs), and a high-entropy alloy (HEA)—was evaluated using the PET-MAD-DOS model [3]. The protocol involved:

- Running MD simulations to generate a representative set of atomic configurations at finite temperatures.

- Predicting the DOS for each snapshot in the trajectory using the universal PET-MAD-DOS model.

- Calculating the electronic heat capacity for each snapshot using the standard thermodynamic relation (outlined in Table 2).

- Averaging the results over the entire trajectory to obtain the ensemble-averaged property.

The results demonstrated that the universal PET-MAD-DOS model achieved semi-quantitative agreement with properties derived from bespoke models, and its accuracy could be further enhanced through fine-tuning [3]. This confirms its utility in complex, real-world simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key computational "reagents" and materials essential for working with and calculating the Density of States.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for DOS Calculations

| Item / Material | Function / Role in DOS Research | Example System / Context |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software (VASP, ADF) | Performs the core electronic structure calculation to obtain wavefunctions and energies from which the DOS is constructed. | VASP for periodic solids [2]; ADF for molecules and clusters [1]. |

| Machine Learning Model (PET-MAD-DOS) | Provides a fast, approximate DOS directly from atomic structure, enabling high-throughput screening. | Universal prediction across the chemical space [3]. |

| Post-Processing Scripts (sumo) | Transforms raw numerical output from DFT codes into interpretable and publishable DOS plots. | Automated plotting of TDOS and PDOS from VASP output [2]. |

| Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD) Dataset | Serves as a diverse training corpus for universal ML models, ensuring broad chemical applicability. | Training foundation for the PET-MAD-DOS model [3]. |

| Lithium Thiophosphate (LPS) | A model solid-state electrolyte system for studying ionic conduction, requiring accurate electronic structure for defect analysis. | Case study for ensemble-averaged DOS and heat capacity [3]. |

| High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs) | Complex multi-component systems where DOS calculations are crucial for understanding phase stability and properties. | Test case for ML model performance on disordered systems [3]. |

The Electronic Density of States remains an indispensable quantity in computational materials science. Its calculation, from first-principles DFT to modern machine-learning models like PET-MAD-DOS, provides profound insight into a material's electronic character, from fundamental properties like band gaps to finite-temperature thermodynamic behavior. As both computational methods and high-performance computing resources continue to advance, the role of DOS analysis will only grow more central in the rational, data-driven design of next-generation materials for energy, electronics, and pharmaceutical applications. The integration of robust machine-learning models promises to make this powerful tool accessible for high-throughput screening and complex dynamical studies previously beyond practical reach.

The Density of States (DOS) represents a fundamental concept in condensed matter physics and materials science, providing a complete description of the number of quantum states available to a system at each energy level. Formally, DOS is defined as the number of electronic states per unit energy interval per unit volume, with dimensionality expressed in states/eV. In the context of electronic structure calculations, the total DOS can be represented as D(r→,E) = Σn |ψn(r→)|² δ(E - En), where ψn(r→) is the space-dependent wavefunction of the nth state and En is the energy of the nth excitation [4]. For crystalline systems, it is often more convenient to work with densities per unit volume to allow for direct integration over Brillouin zones, yielding D(E) = Σn ∫BZ δ(E - En(k→)) dk→/(2π)³, where the integral is taken over the first Brillouin zone [4].

The DOS spectrum reveals critical information about the electronic, optical, and transport properties of materials, serving as a cornerstone for predicting material behavior and functionality. Within the broader context of electronic density of states calculation research, DOS analysis provides the critical link between computational predictions and experimentally observable material properties. The decomposition of DOS into partial components (pDOS) enables researchers to attribute specific spectral features to atomic orbitals, layers, or specific chemical elements, offering unprecedented insight into the orbital origins of material behavior [5] [4]. This technical guide explores three fundamental features extractable from DOS analysis—band edges, effective mass, and Van Hove singularities—that form the essential toolkit for researchers investigating electronic structure properties across materials classes.

Theoretical Framework and Computational Methodologies

Computational Approaches for DOS Calculation

The accurate computation of density of states requires sophisticated numerical methods and computational frameworks. Multiple approaches exist for DOS calculation, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the foundational method for most modern DOS calculations, with implementations including plane-wave pseudopotential methods, all-electron approaches, and localized basis set techniques. The Real space Electronic Structure Calculator (RESCU) represents a powerful MATLAB-based DFT solver capable of predicting electronic structure properties of bulk materials, surfaces, and molecules using numerical atomic orbitals, plane-waves, or real space bases [6].

The Elk Code provides an all-electron full-potential linearised augmented-plane wave (LAPW) implementation with advanced features for high-precision DFT calculations, including LSDA and GGA functionals, variational meta-GGA, and spin-orbit coupling [7]. For practical implementations, packages like gpaw-tools built on top of the ASE, GPAW, and PHONOPY libraries offer user-friendly interfaces for conducting DFT and molecular dynamics calculations, including DOS and band structure analysis [8]. The BAND software package provides specialized DOS analysis capabilities with configurable parameters including energy steps (DeltaE), range specifications (Min/Max), and options for calculating partial DOS (PDOS) and crystal orbital overlap population (COOP) [5].

Table 1: Computational Methods for DOS Analysis

| Method/Software | Basis Set | Key Features | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| RESCU [6] | Numerical atomic orbitals, Plane-waves, Real space | DFT+EXX (hybrid), DFT+U, Spintronics, DOS/PDOS/LDOS | Molecules, surfaces, bulk materials (up to 20k atoms) |

| Elk Code [7] | LAPW with local-orbitals | All-electron, Full-potential, SOC, NCM, EXX, RDMFT | Bulk crystals, surfaces, interfaces |

| gpaw-tools [8] | Plane-wave, LCAO | Multiple XC functionals, Structure optimization, Spin-polarized DOS | Materials science, chemistry, physics, engineering |

| BAND [5] | Not specified | Partial DOS, COOP analysis, Mulliken population analysis | Molecules, periodic systems |

Methodological Protocols for DOS Analysis

The computational determination of DOS follows specific methodological protocols to ensure accuracy and physical meaningfulness. In the BAND package, key parameters include DeltaE (energy step for DOS grid, default 0.005 Hartree), Min/Max (user-defined energy bounds with respect to Fermi energy), and IntegrateDeltaE (algorithm selection for DOS calculation) [5]. The IntegrateDeltaE parameter is particularly important as it determines whether data points represent an integral over states in an energy interval (true) or the number of states at a specific energy (false). The default integration approach (true) helps mitigate issues with wild oscillations in the DOS that might occur with discrete sampling.

For partial DOS (pDOS) calculations, the projection onto specific atomic orbitals follows the Mulliken population analysis partitioning prescription. The pDOS for localized basis functions (orbital channel μ on atom a) is defined as Daμ(E) = Σn ∫BZ |⟨φaμ|ψnk→⟩|² δ(E - En(k→)) dk→/(2π)^d, where φaμ are the localized basis functions and ψnk→ are the Bloch eigenstates [4]. The atomic pDOS is then obtained by summing over all channels on atom a: Da(E) = Σμ∈Λa Daμ(E), and the total DOS decomposes as Dtot(E) = Σa Da(E) = Σa Σμ∈Λa D_aμ(E) [4]. This decomposition enables researchers to trace specific spectral features to particular atoms or orbitals within the material.

A common challenge in DOS calculations is missing DOS in energy intervals where bands exist but no DOS appears, typically caused by insufficient k-space sampling. The recommended solution involves restarting the DOS calculation with a denser k-point grid [5]. Additionally, the treatment of Van Hove singularities requires special consideration, as standard numerical methods may artificially broaden these critical points. Recent machine learning approaches, such as quasi-Van Hove-informed refinement in graph neural networks, augment baseline models with peak-aware additive components whose amplitudes and widths are optimized under a cosine-Fourier loss with curvature and Hessian priors [4].

Band Edge Extraction from DOS Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Detection Methods

Band edges represent critical energy boundaries in electronic structure that separate occupied valence states from unoccupied conduction states. In DOS analysis, the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) are identified as the energy points where the DOS shows a transition from zero to finite values, with the fundamental band gap defined as Egap = ECBM - E_VBM. For metals, the DOS remains continuous across the Fermi level, while semiconductors and insulators exhibit a band gap where the DOS drops to zero. The precise determination of band edges requires high numerical accuracy in DOS calculations, particularly near these critical points where discrete sampling can obscure the true band edge positions.

The extraction methodology involves scanning the DOS distribution to identify the energy values where states begin to appear. In practical implementations, threshold-based algorithms are employed to distinguish between numerical noise and genuine electronic states. The energy range for DOS calculations must be carefully selected using the Min and Max parameters to ensure sufficient resolution around the Fermi energy, typically set to 0.35 Hartree below and 1.05 Hartree above the Fermi level in standard calculations [5]. The energy step parameter DeltaE must be sufficiently small (default 0.005 Hartree) to resolve sharp band edges, particularly in materials with direct band gaps where the VBM and CBM occur at the same k-point [5].

Table 2: Band Edge Characterization Techniques

| Method | Principle | Accuracy Considerations | Material Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct DOS Threshold | Identifies energy where DOS exceeds numerical threshold | Sensitive to k-point sampling and smearing | Universal application |

| DOS Derivative Analysis | Locates inflection points in DOS spectrum | Enhances precision for diffuse edges | Best for sharp band edges |

| Band Structure Alignment | Correlates DOS with electronic band dispersion | Provides k-space resolution | Requires full band calculation |

| Partial DOS Decomposition | Attributes band edges to specific atomic orbitals | Identifies orbital contributions to band edges | Essential for complex materials |

Technical Protocols for Band Edge Determination

The experimental protocol for band edge determination begins with a well-converged ground-state calculation to determine the Fermi energy (EFermi). The DOS calculation is then performed with energy referencing to EFermi, ensuring consistent alignment across different materials. The energy grid must be sufficiently dense around the Fermi level, typically requiring a DeltaE value of 0.002-0.005 Hartree for adequate resolution [5]. For materials with complex band structures or strongly correlated electrons, additional considerations include the use of hybrid functionals (HSE03, HSE06) or GW approximations to correct the underestimation of band gaps common in standard DFT functionals [8].

For partial DOS analysis, the GrossPopulations block in BAND software allows specification of projections onto atomic sites or orbital types using syntax such as FragFun 1 2 (projection onto the second function of the first atom) or Frag 2 (sum of all functions from the second atom) [5]. This enables researchers to determine whether the VBM or CBM derives primarily from specific atomic species or orbital types, information critical for designing materials with tailored band gaps. For example, in photovoltaic materials, achieving a specific band gap through elemental substitution requires understanding which orbitals dominate the band edges.

The visualization workflow for band edge analysis can be represented through the following computational pathway:

Effective Mass Determination from DOS

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation Methods

The effective mass represents a fundamental parameter governing charge carrier mobility in materials, describing how electrons or holes respond to applied electric fields. While effective mass is traditionally determined from band structure curvature via m* = ℏ² / (∂²E/∂k²), DOS analysis provides an alternative approach particularly valuable for materials with complex Fermi surfaces or anisotropic properties. The DOS effective mass relates to the density of states at the Fermi level through the relationship m*DOS = ℏ² (3π² n)^(2/3) / (2EF), where n is the carrier concentration and E_F is the Fermi energy.

For parabolic bands, the DOS effective mass can be extracted directly from the DOS energy dependence using the expression D(E) = (2m*DOS)^(3/2) / (2π² ℏ³) × √|E - Eb|, where E_b is the band edge energy [4]. This relationship demonstrates that the square-root energy dependence of DOS near band edges characteristic of parabolic bands provides a direct measurement of the effective mass. For non-parabolic bands or materials with complex dispersion, the DOS effective mass represents an average over all carrier directions and energy states, providing a single representative value for device modeling and transport property prediction.

The Elk Code implementation offers direct calculation of effective mass tensors for any state, providing both the computational framework and analytical tools for comprehensive effective mass analysis [7]. This capability is particularly valuable for anisotropic materials where carrier effective mass varies significantly with crystallographic direction. The code determines the effective mass tensor through second-derivative analysis of the band structure, with components m*ij = ℏ² / (∂²E/∂ki∂k_j), which can be correlated with DOS measurements to validate computational approaches.

Technical Implementation and Analysis Protocols

The protocol for effective mass determination from DOS begins with accurate DOS calculations spanning appropriate energy ranges relative to the band edges. For electron effective mass, the focus is on the conduction band minimum, while hole effective mass analysis requires examination of the valence band maximum. The DOS must be calculated with high energy resolution (small DeltaE) near the band edges to accurately capture the DOS(E) ∝ √|E - E_b| relationship. The CompensateDeltaE parameter should be set to "Yes" to ensure proper normalization when using the integration algorithm [5].

The analysis procedure involves fitting the calculated DOS near the band edge to the theoretical expression D(E) = C × √|E - Eb|, where C = (2m*DOS)^(3/2) / (2π² ℏ³). From the fitted parameter C, the DOS effective mass can be extracted as m*_DOS = (2π² ℏ³ C)^(2/3) / 2. This approach provides particularly accurate results for materials with isotropic band structures where a single effective mass parameter suffices. For anisotropic materials, the DOS effective mass represents a weighted average over different crystallographic directions, with the weighting determined by the relative contributions of different k-space regions to the total DOS.

The experimental workflow for effective mass determination integrates multiple computational steps:

Validation of results requires comparison with effective mass values obtained through alternative methods, particularly the band structure derivative approach implemented in codes like Elk [7]. Discrepancies between the two methods may indicate non-parabolicity, band anisotropy, or many-body effects not captured by standard DFT functionals. For such cases, advanced computational methods such as GW approximation or hybrid functionals may be necessary to obtain quantitatively accurate effective mass values [8] [7].

Van Hove Singularities Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Physical Significance

Van Hove singularities (VHS) represent critical points in the energy spectrum where the electronic density of states exhibits non-analytic behavior, typically manifesting as sharp peaks or discontinuities in the DOS. These singularities arise mathematically from points in k-space where the gradient of the electronic band dispersion vanishes (∇_k E = 0), leading to a logarithmic divergence in two dimensions or a square-root singularity in three dimensions [4]. The classification of Van Hove singularities follows from the analysis of the Hessian matrix eigenvalues at these critical points, distinguishing between minima, saddle points, and maxima in the band structure.

The physical significance of VHS stems from their profound influence on electronic, optical, and magnetic properties. The enhanced DOS at Van Hove singularities leads to increased electron-electron correlation effects, potentially driving phenomena such as superconductivity, charge density waves, and magnetic ordering [4] [7]. In low-dimensional materials like graphene, the presence of Van Hove singularities near the Fermi level creates unique opportunities for tuning electronic properties through doping or gating, with potential applications in optoelectronics and quantum devices.

Recent advances in machine learning approaches for DOS prediction have incorporated specific treatment of Van Hove singularities through quasi-Van Hove-informed refinement. This method augments baseline graph neural network models with peak-aware additive components whose amplitudes and widths are optimized under a cosine-Fourier loss with curvature and Hessian priors [4]. The approach identifies candidate singularities as zeros of the derivative of the GNN representation of the DOS: ∂/∂E [GNN1[Dtotal(E - EFermi)]] = 0, effectively locating critical points that may be smoothed over by conventional numerical methods or machine learning predictions [4].

Computational Identification and Analysis Protocols

The computational identification of Van Hove singularities requires high-resolution DOS calculations with dense k-point sampling and minimal numerical broadening. The standard protocol involves first-principles DFT calculations with increasingly dense k-meshes to converge the DOS near singular points, often requiring 4-10 times higher k-point density than typical DOS calculations. The Elk Code provides specialized implementations for identifying and analyzing critical points in the band structure, including automatic determination of muffin-tin radii and full symmetrization of density and magnetization [7].

The analysis methodology involves several sequential steps: (1) calculation of the total DOS with high energy resolution, (2) numerical differentiation to identify points of discontinuity or rapid change, (3) tracing identified features to specific k-points in the Brillouin zone, and (4) classification of singularity type based on the band curvature analysis. For complex materials with multiple bands, each singularity must be associated with specific band indices and k-point locations to enable physical interpretation. The computational workflow can be represented as:

For advanced analysis, the OverlapPopulations block in BAND software enables calculation of overlap population weighted DOS (OPWDOS), also known as crystal orbital overlap population (COOP), which provides additional insight into the bonding/antibonding character of states near Van Hove singularities [5]. The syntax OVERLAPPOPULATIONS LEFT {Frag 1} RIGHT {Frag 2} generates the OPWDOS between specified fragments, revealing how singularities correlate with specific bonding interactions in the material [5].

Table 3: Classification and Properties of Van Hove Singularities

| Singularity Type | Hessian Eigenvalues | DOS Behavior | Dimensionality | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 (Minimum) | (+, +, +) | D(E) ∝ √(E - E_0) | 3D | Band edge onset |

| M1 (Saddle Point) | (+, +, -) | D(E) ∝ -log|E - E_0| | 2D/3D | Enhanced correlations |

| M2 (Saddle Point) | (+, -, -) | D(E) ∝ -log|E - E_0| | 2D/3D | Enhanced correlations |

| M3 (Maximum) | (-, -, -) | D(E) ∝ √(E_0 - E) | 3D | Band edge termination |

The effective implementation of DOS analysis requires specialized computational tools and software packages, each offering unique capabilities for electronic structure calculation and analysis. This section provides a comprehensive overview of essential resources for researchers investigating band edges, effective mass, and Van Hove singularities through DOS analysis.

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for DOS Analysis

| Software/Resource | Primary Function | Key Features for DOS Analysis | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAND [5] | DOS/PDOS Calculation | Configurable energy grid, PDOS projections, COOP analysis | Requires careful k-grid convergence |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [9] | Plane-wave DFT | Open-source, pseudopotential-based, extensive functionality | Community-supported development |

| Elk Code [7] | All-electron LAPW | High-precision, all-electron, full-potential, EXX, SOC | Memory-intensive for large systems |

| RESCU [6] | MATLAB-based DFT | Real-space calculations, large systems (20k atoms), hybrid functionals | MATLAB environment required |

| gpaw-tools [8] | GUI/UI for DFT | User-friendly interface, multiple XC functionals, structure optimization | Built on ASE/GPAW libraries |

The selection criteria for DOS analysis tools depend on multiple factors including system size, required accuracy, computational resources, and specific properties of interest. For high-precision calculations of Van Hove singularities in bulk crystals, all-electron codes like Elk provide the most accurate treatment of electronic states [7]. For larger systems such as surfaces or nanostructures, plane-wave pseudopotential methods implemented in Quantum ESPRESSO or real-space approaches in RESCU offer favorable scaling with system size [9] [6]. For rapid prototyping or educational applications, user-friendly interfaces like gpaw-tools lower the barrier to entry for DOS analysis [8].

The computational requirements for accurate DOS analysis vary significantly based on the specific feature being investigated. Band edge determination typically requires moderate k-point densities and standard DFT functionals. Effective mass analysis demands high energy resolution near band edges and potentially advanced functionals for quantitative accuracy. Van Hove singularity identification requires the most computationally intensive approach with high k-point densities, potentially hybrid functionals, and careful convergence testing. Across all applications, the critical importance of k-point sampling cannot be overstated, with insufficient sampling representing the most common source of error in DOS analysis [5].

The analysis of density of states provides essential insights into the electronic structure of materials, with band edges, effective mass, and Van Hove singularities representing three fundamental features extractable from DOS distributions. Band edge determination enables classification of materials as metals, semiconductors, or insulators and provides the foundation for understanding electronic and optical properties. Effective mass analysis from DOS offers valuable information about charge carrier behavior and transport characteristics, particularly valuable for materials with complex Fermi surfaces. Van Hove singularity identification reveals critical points in the electronic structure that govern enhanced correlation effects and potential instabilities.

Future developments in DOS analysis will likely focus on several key areas. Machine learning enhancements, such as the quasi-Van Hove-informed refinement approach already being developed, will improve the accuracy and efficiency of DOS predictions [4]. Advanced computational methods including higher-order exchange-correlation functionals, GW approximations, and Bethe-Salpeter equation solutions will address current limitations in predicting quantitatively accurate DOS distributions, particularly for strongly correlated materials [8] [7]. High-throughput computational screening leveraging DOS analysis across materials databases will enable the identification of novel materials with optimized electronic properties for specific applications.

The integration of DOS analysis with emerging experimental techniques, particularly scanning tunneling spectroscopy and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, will continue to bridge the gap between computational predictions and experimental observations. As computational resources expand and methodological improvements continue, DOS analysis will remain a cornerstone of electronic structure research, providing fundamental insights that drive materials discovery and technological innovation across electronics, energy, and quantum technologies.

The Critical Role of DOS in Determining Material Properties and Behavior

The Electronic Density of States (DOS) is a fundamental concept in condensed matter physics and materials science that describes the number of electronic states available at each energy level in a material. Formally, it represents the distribution of permissible energy levels that electrons can occupy. The DOS is not merely a theoretical construct; it serves as a powerful bridge between a material's atomic structure and its macroscopic properties. By analyzing the DOS, researchers can gain profound insights into why materials behave as metals, semiconductors, or insulators, and can predict key characteristics such as optical response, thermal properties, and chemical stability. The shape, intensity, and fine features of the DOS plot provide a concise yet highly informative summary of the electronic structure, revealing details about electron interactions, bonding character, and the effective dimensionality of electrons within the material [10] [11].

Theoretical Foundations and Calculation Methodologies

Fundamental Principles

The DOS is intrinsically linked to the solution of the quantum mechanical equations that govern electron behavior in a solid. In density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the Kohn-Sham equations are solved to obtain the eigenvalues (energy levels) and eigenvectors (wavefunctions) for the system. The DOS, denoted as ρ(E), is then calculated from these eigenvalues. For a periodic solid, the DOS is computed by integrating over the Brillouin zone:

ρ(E) = Σₙ ∫_{BZ} [d𝐤 / (2π)ᵈ] δ(E - Eₙ(𝐤))

where n is the band index, 𝐤 is the wave vector, d is the dimensionality, and Eₙ(𝐤) is the energy of the n-th band at wave vector 𝐤 [12]. This formula essentially counts the number of electronic states per unit energy per unit volume. The resulting DOS plot reveals critical features such as band gaps, band edges, and Van Hove singularities—points where the derivative of the DOS becomes discontinuous, indicating high densities of states that significantly influence material properties [10].

Practical Calculation Workflows

Obtaining a converged and physically meaningful DOS requires a carefully structured computational approach. The typical workflow involves two sequential steps:

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: The first step involves performing a self-consistent calculation to determine the ground-state electron density of the system. This requires a sufficiently dense k-point grid (e.g., an 8×8×8 Monkhorst-Pack set) to ensure accurate sampling of the Brillouin zone and convergence of the atomic charges. The SCF cycle is iterated until the total energy and charge density converge to within a specified tolerance (e.g., 1×10⁻⁵ eV) [13].

Non-Self-Consistent Field (NSCF) Calculation: Using the converged charge density from the SCF calculation, a second calculation is performed on a different set of k-points. For the total DOS, a uniform, dense k-point grid is used. For the band structure, k-points are selected along high-symmetry lines in the Brillouin zone (e.g., Z-Γ-X-P for anatase) [12] [13]. This two-step process ensures an accurate electronic structure is obtained without the computational expense of achieving self-consistency on a very large k-point set.

The following diagram illustrates this standard workflow for computing the DOS:

Advanced DOS Analysis: PDOS and COOP

To move beyond the total DOS and understand the atomic and orbital contributions to the electronic structure, researchers employ more advanced analyses:

Partial Density of States (PDOS): PDOS decomposes the total DOS into contributions from specific atoms, atomic species, or orbitals (e.g., s, p, d). This is crucial for identifying the chemical nature of bonds and the atomic origins of specific electronic features. For example, in anatase TiO₂, PDOS reveals that the valence band edge is composed primarily of oxygen p-orbitals, while the conduction band edge consists of titanium d-orbitals [13]. PDOS is typically calculated using projection schemes like the Mulliken population analysis, which partitions the total DOS based on the contributions from selected basis functions [5].

Crystal Orbital Overlap Population (COOP) / COHP: This analysis weighs the DOS by the overlap population between atoms, providing direct insight into bonding character. A positive COOP indicates bonding states, a negative value indicates anti-bonding states, and values near zero indicate non-bonding states. This is an invaluable tool for understanding the strength and nature of chemical bonds in materials [5].

Material Properties Deduced from DOS Analysis

The DOS serves as a powerful diagnostic tool, enabling the determination of numerous critical material properties. The table below summarizes key properties that can be directly extracted or inferred from a thorough analysis of the DOS.

Table 1: Material Properties Accessible from Density of States Analysis

| Property Category | Specific Property | How to Deduce from DOS |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure | Band Gap & Metallicity | Energy difference between the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM). A zero gap indicates a metal/semimetal [14] [12]. |

| Band Dispersion & Effective Mass | Curvature of the band edges; a steeper slope implies a lighter effective mass for electrons (e⁻) or holes (h⁺) [14] [10]. | |

| Dimensionality & Van Hove Singularities | Characteristic sharp peaks in the DOS reveal quasi-low-dimensional electron behavior and critical points in the band structure [10]. | |

| Chemical Bonding | Orbital Hybridization | PDOS analysis shows contributions from specific atoms and orbitals (s, p, d), revealing the nature of chemical bonds [13]. |

| Bonding/Anti-bonding Character | COOP/COHP analysis identifies the energy regions of bonding and anti-bonding interactions [5]. | |

| Physical Properties | Optical Transitions | DOS reveals available initial and final states for electron excitation, influencing absorption spectra [14] [15]. |

| Transport Properties | The DOS at the Fermi level (E_F) heavily influences electrical conductivity. The band gap determines the intrinsic carrier concentration in semiconductors [15]. | |

| Magnetic Properties | Spin-polarized DOS shows different distributions for spin-up and spin-down electrons, indicating magnetism [14]. |

Interpretation of Key Electronic Properties

Band Gap and Metallicity: The most immediate property determined from the DOS is the fundamental band gap. It is calculated as the energy difference between the CBM and the VBM. Materials are classified as metals (no gap, finite DOS at the Fermi level), semiconductors (small gap), or insulators (large gap) based on this value. It is crucial to note that standard DFT calculations (using LDA or GGA functionals) are known to underestimate band gaps by approximately 40-50% compared to experimental values due to approximations in the exchange-correlation functional [12].

Effective Mass: The effective mass of charge carriers is a critical parameter governing charge transport. It is inversely proportional to the curvature of the bands near the VBM (for holes) and CBM (for electrons). A flatter band in the band structure corresponds to a higher DOS and a heavier effective mass, while a more dispersive (steeply curved) band indicates a lighter effective mass, typically leading to higher carrier mobility [14] [10].

Computational Tools and Experimental Protocols

Essential Software and Visualization Tools

A range of software packages is available for performing DFT calculations and subsequent DOS analysis. The choice of software often depends on the target material system (solid or molecular), desired properties, and available resources.

Table 2: Representative DFT Software for DOS Calculations

| Software | Main Target System | Key Features | Main Compatible Viewer | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Solid | Industry standard for solid-state/periodic systems [15]. | p4vasp, VESTA [15] | Paid |

| Quantum Espresso | Solid | Open-source software for solid-state calculations [15]. | VESTA [15] | Free |

| Gaussian | Molecular | Industry standard for molecular systems; GUI available [15]. | GaussView, Avogadro [15] | Paid |

| ORCA | Molecular | Strong in optical properties and high-precision calculations [15]. | Avogadro, ChemCraft [15] | Paid (Academic free) |

| DFTB+ | Solid/Molecular | Fast DFT-based tight-binding method; used for DOS/PDOS [13]. | - | Free |

For visualizing results, tools like VESTA (for crystal structures and volumetric data) and sumo (specifically for generating publication-quality band structure and DOS plots) are widely used. The sumo package, for instance, can be invoked via command line (sumo-dosplot) to automatically generate DOS plots from VASP output files, significantly streamlining the analysis process [2].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Computational Reagents

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagents" for DOS Calculations

| Item / Concept | Function in DOS Calculations |

|---|---|

| Pseudopotentials / Basis Set | Defines the interaction between valence electrons and ionic cores. Choice impacts accuracy and computational cost [15]. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Approximates the quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects. Determines accuracy of band gaps (e.g., PBE underestimates, HSE improves) [12]. |

| k-Point Grid | A mesh of points in the Brillouin zone for numerical integration. A denser grid is needed for accurate DOS than for ground-state energy [12] [13]. |

| Slater-Koster Files | Precomputed integral tables for DFTB+ calculations, analogous to pseudopotentials in full DFT [13]. |

| Mulliken Population Analysis | A method for projecting the total DOS onto atomic orbitals to obtain the PDOS [5]. |

Protocol for Accurate DOS Calculation and Analysis

The following protocol outlines the key steps for obtaining and validating a DOS, drawing from the methodologies of high-throughput frameworks like the Materials Project [12].

- Geometry Optimization: Fully relax the atomic coordinates and unit cell of the structure to its ground-state configuration before any electronic structure analysis.

- SCF Calculation with Dense k-Point Grid: Perform a self-consistent calculation with a high-quality k-point mesh (e.g., determined by a convergence test) to obtain the ground-state charge density.

- NSCF DOS Calculation: Using the converged charge density, perform a non-self-consistent calculation on an even denser k-point grid specifically for the DOS. The

DeltaEparameter (energy grid spacing) should be chosen for sufficient resolution (e.g., 0.005 Hartree ~0.14 eV) [5]. - Validation and Gap Analysis: Cross-check the band gap from the DOS with the gap from the band structure calculation. If a material shows an unexpected metallic state (0 eV gap), recompute the gap from the DOS using the

get_gap()method in analysis tools likepymatgento rule out parsing artifacts [12]. - Projected DOS Calculation: Execute the PDOS calculation by specifying the atoms and orbitals of interest in the input file (e.g., using the

ProjectStatesblock in DFTB+ or equivalent in other codes) [13]. - Post-Processing and Visualization: Use visualization tools (e.g.,

dp_dos,sumo,xmgrace) to plot the total and partial DOS, aligning the Fermi level to zero energy.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of electronic structure analysis is rapidly evolving, with new methods enhancing both the accuracy and efficiency of DOS calculations.

Beyond Standard DFT: To address the well-known band gap problem, methods like GW approximation and hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE) are being increasingly employed. These methods provide a more accurate description of electron-electron interactions, yielding band gaps and DOS profiles that are in closer agreement with experimental data [12].

Machine Learning Accelerated DOS Prediction: A significant emerging trend is the application of machine learning (ML) to predict DOS patterns. One demonstrated approach uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to compress DOS data and simple features (d-orbital occupation, coordination number) to reconstruct the DOS with 91-98% similarity to DFT results at a fraction of the computational cost. This ML method scales independently of the number of electrons, breaking the traditional O(N³) scaling of DFT and allowing for the rapid screening of material libraries [11].

The Density of States is far more than a simple electronic histogram; it is a critical tool for elucidating the fundamental principles that govern material behavior. Through careful computational calculation—involving converged SCF cycles, appropriate k-point sampling, and projective techniques—the DOS provides a detailed window into the electronic soul of a material. It allows researchers to directly connect atomic-scale arrangements to macroscopic properties, from conductivity and optical response to chemical bonding and catalytic activity. As computational methods advance, with machine learning offering new pathways for high-throughput discovery and advanced electronic structure theories delivering ever-greater accuracy, the role of DOS as a cornerstone of materials research is not only secure but poised for continued growth and influence.

The electronic density of states (DOS) is a foundational concept in computational materials science and chemistry, quantifying the distribution of available electron energy levels in a system. Its significance extends across diverse applications, from predicting electronic transport properties and optical characteristics to informing the design of semiconductors and catalysts [3] [16]. Within the framework of density functional theory (DFT) calculations, two complementary views of the DOS emerge: the total density of states (Total DOS), a global property of the entire structure, and the atom-projected local density of states (LDOS), which decomposes this global picture into atomic contributions. This distinction is not merely academic; it is crucial for interpreting complex electronic structure calculations, especially for heterogeneous systems like surfaces, doped materials, and molecules adsorbed on substrates. The progression from global to local analysis represents a core theme in modern electronic structure research, enabling scientists to bridge the gap between macroscopic material properties and atomic-scale interactions [17] [18]. This guide delves into the fundamental principles, computational methodologies, and practical applications of both Total DOS and LDOS, providing researchers with the tools to leverage these concepts in their investigations.

Theoretical Foundations: From Global DOS to Atomic Projections

Total Density of States (DOS)

The Total DOS, denoted as ( \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon) ), is defined such that ( \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon)d\varepsilon ) represents the number of electronic states in the energy interval between ( \varepsilon ) and ( \varepsilon + d\varepsilon ) for the entire system [17]. For a periodic crystalline solid, this is mathematically formulated as an integral over the Brillouin Zone (BZ):

[ \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon) = \frac{1}{\Omega{\text{BZ}}} \sum{n} \int{\text{BZ}} \delta(\varepsilon - \varepsilon{n}(\mathbf{k})) d\mathbf{k} ]

Here, ( \varepsilon{n}(\mathbf{k}) ) is the energy of the ( n )-th electronic band at point ( \mathbf{k} ) in the reciprocal space, ( \Omega{\text{BZ}} ) is the volume of the Brillouin zone, and the sum runs over all bands [19]. In practical computations, this integral is approximated by summing over a finite grid of ( k )-points:

[ \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon) \approx \frac{1}{N{\mathbf{k}}} \sum{n, \mathbf{k}} \delta(\varepsilon - \varepsilon_{n, \mathbf{k}}) ]

where ( N_{\mathbf{k}} ) is the number of ( k )-points sampled [17]. The Total DOS provides a global overview of the electronic energy spectrum, revealing key features such as band gaps, band widths, and the presence of sharp peaks (van Hove singularities) that dominate many physical properties.

Atom-Projected Local Density of States (LDOS)

The Atom-Projected LDOS, or ( \mathcal{D}_{i}(\varepsilon) ), decomposes the total DOS into contributions originating from specific atoms or atomic orbitals within the structure. This decomposition can be achieved through several physical projection schemes, fundamentally relying on the principle of partitioning space or the wavefunction [17].

One common method involves a real-space partition, where the physical space is divided into non-overlapping atomic basins surrounding each atom. The LDOS for atom ( i ) is then obtained by integrating the space-resolved DOS, ( \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon, \mathbf{r}) ), over the volume of its basin:

[ \mathcal{D}{i}(\varepsilon) = \int\limits{\text{atom } i} \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon, \mathbf{r}) d\mathbf{r} ]

The space-resolved DOS is given by:

[ \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon, \mathbf{r}) = \frac{1}{N{\mathbf{k}}} \sum{n, \mathbf{k}} |\psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r})|^{2} \delta(\varepsilon - \varepsilon{n, \mathbf{k}}) ]

where ( \psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) ) is the Kohn-Sham wavefunction [17]. An alternative approach employs a Hilbert-space partition using a basis set of atom-centered orbitals, ( { \phi{\alpha} } ). Expressing the wavefunctions in this basis (( |\psi{n\mathbf{k}}\rangle = \sum{\alpha} c{n\mathbf{k}, \alpha} |\phi{\alpha}\rangle )), the projected DOS can be defined via the basis functions localized on a particular atom [18]. This orbital-projected density of states (PDOS) is particularly useful for interpreting chemical bonding and orbital hybridization.

Table 1: Core Concepts of Total DOS and Atom-Projected LDOS

| Feature | Total DOS (( \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon) )) | Atom-Projected LDOS (( \mathcal{D}_{i}(\varepsilon) )) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Global property of the entire structure | Contribution from a specific atom or atomic basin |

| Information Scale | Macroscopic, system-averaged | Local, atom-resolved |

| Key Applications | Identifying band gaps, system-wide metallic character | Analyzing local bonding, surface states, catalytic sites |

| Theoretical Basis | Sum over all electronic states in the Brillouin Zone | Partitioning of real space or Hilbert space |

Computational Methodologies and Machine Learning Advances

Conventional DFT Workflows

In conventional DFT calculations, the workflow for obtaining the DOS and LDOS begins with solving the Kohn-Sham equations self-consistently to obtain the ground-state electron density and Kohn-Sham wavefunctions [16] [19]. For periodic systems, this calculation is performed on a carefully selected grid of ( k )-points within the Brillouin Zone to ensure proper convergence [19]. The DOS is then computed by summing the obtained eigenvalues, typically using a broadening function (e.g., Gaussian or Methfessel-Paxton) to approximate the Dirac delta function in the DOS formula. Projecting the DOS onto atomic or orbital contributions requires additional post-processing, using one of the partitioning schemes mentioned in Section 2.2. The convergence of these quantities with respect to the ( k )-point grid density and the basis set size is critical for obtaining accurate, physically meaningful results.

Machine Learning for DOS and LDOS

Recent advances have introduced machine learning (ML) as a powerful surrogate for direct DFT calculations, offering orders-of-magnitude speedups for DOS/LDOS evaluation [3] [16] [17]. Two primary ML paradigms have emerged:

- Learning the Structural DOS: Models like PET-MAD-DOS are "universal" machine-learning models trained on diverse datasets (e.g., the Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD) dataset) to predict the total DOS directly from the atomic structure. These models use architectures such as the Point Edge Transformer (PET) and demonstrate semi-quantitative agreement with DFT across a wide range of materials [3].

- Learning the Atomic LDOS: An alternative, more scalable approach involves learning the atomic LDOS, ( \mathcal{D}{i}(\varepsilon) ), from the local chemical environment of each atom [17]. The total DOS is then obtained by summing these local contributions: ( \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon) = \sum{i} \mathcal{D}_{i}(\varepsilon) ). This method leverages the "nearsightedness" principle of electronic matter, which states that the local electronic structure is largely determined by the immediate atomic neighborhood [17]. This approach boasts superior transferability and scalability to very large systems.

These ML models typically use a rotationally invariant representation (or learn invariance from data) to map the local atomic environment around a point (or atom) to the electron density or LDOS at that location [16]. The mapping is learned by neural networks trained on reference DFT data.

Diagram 1: Machine learning workflows for predicting global DOS and local LDOS.

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models for DOS Prediction

| Model / Approach | Architecture | Training Data | Key Performance Metric | Reported Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET-MAD-DOS (Global DOS) [3] | Point Edge Transformer (PET) | Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD) dataset | RMSE on external datasets (e.g., MPtrj, SPICE) | Semi-quantitative agreement; error < 0.2 eV⁻⁰.⁵ for most structures |

| Atomic LDOS Learning [17] | Neural Networks on local environments | Silicon and Carbon structures | RMSE for LDOS and derived total DOS | LDOS learning achieves higher accuracy for total DOS than direct structural DOS learning |

Experimental Protocols and a Scientist's Toolkit

Detailed Protocol: Machine Learning of Atomic LDOS

The following protocol outlines the key steps for developing a machine learning model to predict the atom-projected LDOS, as demonstrated in recent literature [17].

Dataset Curation:

- Source: Generate a diverse set of atomic structures (e.g., bulk crystals, surfaces, molecules, defected structures) relevant to the target material class.

- Reference Calculations: Perform ab-initio DFT calculations for these structures to obtain the ground-state electron density and wavefunctions.

- Projection: Compute the reference atom-projected LDOS, ( \mathcal{D}_{i}(\varepsilon) ), for each atom ( i ) in every structure, using a chosen projection scheme (e.g., real-space basin or orbital projection).

Feature Engineering (Fingerprinting):

- For each atom ( i ) in the dataset, compute a numerical descriptor (fingerprint) that mathematically represents its local chemical environment. This descriptor must be rotationally and translationally invariant.

- Example: Use a hierarchy of features comprising scalar, vector, and tensor invariants derived from Gaussian functions centered on the atom, which capture radial and angular information of neighboring atoms [16].

Model Training:

- Architecture: Design a neural network (e.g., with multiple hidden layers) that takes the atomic fingerprint as input.

- Output: The output layer should predict the discretized LDOS spectrum for the atom. The number of output neurons corresponds to the number of energy windows.

- Loss Function: Train the network by minimizing a loss function, typically the Mean Squared Error (MSE), between the predicted and DFT-calculated LDOS for all atoms in the training set.

Validation and Prediction:

- Validation: Assess the model on a held-out test set of structures not seen during training. Evaluate the accuracy for both the atomic LDOS and the total DOS (obtained by summing predicted LDOS).

- Deployment: For a new, unknown structure, extract the local environment and fingerprint for each atom, use the trained model to predict its LDOS, and sum contributions to obtain the total DOS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Methods for DOS/LDOS Analysis

| Tool / Method | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-Principles Calculation | Solves Kohn-Sham equations to obtain ground-state electronic structure, wavefunctions, and energies [16] [19]. |

| Projection Scheme (e.g., Bader, Mulliken, Löwdin) | Analysis Algorithm | Partitions the total DOS into atom-projected or orbital-projected contributions (LDOS/PDOS) [17] [18]. |

| k-point Sampling | Computational Parameter | Discretizes the Brillouin Zone for periodic systems; critical for converging properties of metals and semiconductors [19]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (e.g., PET) | Surrogate Model | Learns a mapping from atomic structure to electronic properties (DOS, LDOS) or energies/forces, bypassing expensive DFT [3]. |

| Local Environment Descriptor (e.g., SOAP, ACE) | Featurization Method | Encodes the geometric and chemical arrangement of an atom's neighbors into a rotationally invariant vector for ML models [16]. |

Application in Property Prediction and Materials Design

The utility of DOS and LDOS extends far beyond a simple visualization of the electronic spectrum; they are directly used to compute fundamental physical properties.

- Band Energy: The sum of occupied Kohn-Sham eigenvalues, crucial for total energy calculations, is computed as ( E{\text{band}} = \int{-\infty}^{\varepsilon_F} \varepsilon \mathcal{D}(\varepsilon) d\varepsilon ) [17].

- Fermi Energy and Electronic Heat Capacity: The Fermi energy (( \varepsilonF )) is determined by requiring the integral of the DOS up to ( \varepsilonF ) equals the total number of electrons. The electronic heat capacity is proportional to the DOS at the Fermi level, ( D(\varepsilon_F) ), in metals [3] [17].

- Magnetic Susceptibility: The Pauli paramagnetic susceptibility is also directly related to ( D(\varepsilon_F) ) [17].

- Interpreting Quantum Transport: In molecular electronics, the PDOS is routinely used to interpret the quantum conductance of molecular junctions, often by correlating conductance peaks with features in the PDOS of specific molecular orbitals (e.g., HOMO, LUMO) [18].

Diagram 2: Key material properties derived from total DOS and atom-projected LDOS.

The local perspective offered by LDOS is indispensable for materials design. It allows researchers to pinpoint the atomic species or specific sites responsible for a particular electronic feature. For instance, in a high-entropy alloy, LDOS can reveal how different elements contribute to states at the Fermi level, governing stability and electronic transport [3]. In catalyst design, the LDOS of surface atoms can be analyzed to understand their reactivity and identify descriptors for activity, such as the position of the d-band center.

The journey from the global picture of the Total DOS to the atomically resolved detail of the LDOS is more than a change in scale—it is a fundamental shift towards interpretability and causal understanding in electronic structure theory. While the Total DOS provides the overarching electronic landscape of a material, the Atom-Projected LDOS serves as a powerful lens, magnifying the roles of individual atoms and their local environments. As computational methods evolve, particularly with the rise of machine learning models that learn these quantities directly from atomic structure, the integration of global and local analysis will become increasingly seamless. This synergy is poised to accelerate the discovery and rational design of next-generation materials for applications ranging from drug development to energy storage and quantum computing, solidifying its place as a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and chemistry.

The electronic structure of a material, fundamentally described by its density of states (DOS), governs its electrical, optical, and magnetic properties. The DOS quantifies the number of available electronic states per unit energy interval and is defined as (D(E) = N(E)/V), where (N(E)\delta E) is the number of allowed states in the energy range between (E) and (E + \delta E), and (V) is the system volume [20]. A critical factor influencing the form and function of the DOS is the dimensionality of the system. The physical confinement of electrons in one, two, or three dimensions leads to profound changes in the energy dispersion relations, which are directly reflected in the DOS [20]. Understanding these dimensionality effects is essential for tailoring materials for specific applications in nanoelectronics, catalysis, and energy conversion. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundations of DOS across different dimensionalities, explores advanced computational frameworks for its prediction, and provides detailed protocols for data-driven analysis, contextualized within modern materials research.

Theoretical Foundations of DOS by Dimensionality

The dimensionality of a system directly dictates the topology of its k-space and confines the momentum of particles within it. This confinement results in distinct DOS profiles for systems of different dimensionalities, particularly under the assumption of a parabolic energy dispersion [20].

Table 1: Analytical Density of States Formulas for Different Dimensionalities

| Dimensionality | System Examples | Dispersion Relation | Density of States (D(E)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D (Bulk) | Bulk crystals (Si, Pt), Fermi gases | (E \propto k^2) | (D_{3D}(E) \propto E^{1/2}) [20] |

| 2D (Quantum Wells) | 2D Electron Gases (2DEG), Graphite layers | (E \propto k^2) | (D_{2D} = \text{constant}) [20] |

| 1D (Quantum Wires) | Carbon nanotubes, quantum wires | (E \propto k^2) | (D_{1D}(E) \propto E^{-1/2}) [20] |

The physical manifestation of these formulas is significant. In three-dimensional (3D) bulk materials, the DOS scales with the square root of energy, (E^{1/2}). This continuous, smooth function is characteristic of standard bulk semiconductors and metals. In contrast, two-dimensional (2D) systems, such as graphene or quantum wells, exhibit a step-like DOS that is constant between sub-band edges. This leads to unique optical and transport properties. The most dramatic change occurs in one-dimensional (1D) systems like carbon nanotubes, where the DOS exhibits sharp, singular peaks at the sub-band energies, described by an (E^{-1/2}) relationship. These van Hove singularities dominate the optical response and electronic behavior of 1D materials [20]. Furthermore, in isolated systems such as molecules or quantum dots, which can be considered zero-dimensional (0D), the DOS is not a continuous function but a set of discrete delta functions at specific energy levels, representing the atomic-like or molecular orbitals [20].

Diagram 1: Relationship between material dimensionality and the resulting DOS profile.

Computational and Machine Learning Frameworks

Accurately calculating the electronic structure of low-dimensional systems using traditional Density Functional Theory (DFT) is computationally demanding, especially for large or complex structures. While slab-based DFT simulations can accurately capture surface properties, they are computationally intensive and not readily scalable for high-throughput screening [21]. This computational bottleneck has driven the development of innovative machine learning (ML) frameworks designed to predict electronic properties directly from atomic structures with DFT-level accuracy but at a fraction of the cost.

Universal Deep Learning for Hamiltonian Prediction

A significant advancement is the NextHAM framework, a neural E(3)-symmetry and expressive correction model for electronic-structure Hamiltonian prediction [22]. NextHAM addresses generalization challenges across diverse elements by using the zeroth-step Hamiltonian, ( \mathbf{H}^{(0)} ), as a physically informative input descriptor. This Hamiltonian is constructed from the initial electron density without expensive matrix diagonalization. The model then learns to predict the correction term ( \Delta\mathbf{H} = \mathbf{H}^{(T)} - \mathbf{H}^{(0)} ), which simplifies the learning task and enhances fine-grained prediction accuracy [22]. The model is trained on a large, diverse dataset (Materials-HAM-SOC) containing 17,000 materials spanning 68 elements, enabling robust predictions across the periodic table.

Direct DOS Prediction with Transformers

Another approach bypasses the Hamiltonian and predicts the DOS directly. The PET-MAD-DOS model is a universal, rotationally unconstrained transformer model built on the Point Edge Transformer (PET) architecture [3]. Trained on the Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD) dataset—which includes molecules, bulk crystals, surfaces, and clusters—this model demonstrates semi-quantitative agreement for the ensemble-averaged DOS of technologically relevant systems like lithium thiophosphate (LPS) and gallium arsenide (GaAs) [3]. A key advantage is its ability to be fine-tuned with small, system-specific datasets to achieve performance comparable to models trained exclusively on that data.

Linear Mapping and Similarity Descriptors

For scenarios with limited data, simpler, more interpretable models can be highly effective. A PCA-based linear mapping framework has been successfully demonstrated to predict the surface DOS directly from the bulk DOS for Cu–B–S chalcogenides [21]. This method relies on the finding that low-dimensional representations (PCA scores) of bulk and surface DOS are linearly related. A transformation matrix, trained on a small set of compounds with known surface and bulk DOS, can then predict the surface DOS for new compositions, bypassing expensive slab-DFT calculations [21].

For data analysis, a tunable DOS fingerprint has been developed to encode the DOS into a binary-valued 2D map [23]. This descriptor allows for a tailored weighting of spectral features, providing a finer discretization near focus regions like the Fermi level. The similarity between two materials can then be quantified using the Tanimoto coefficient (Tc), enabling unsupervised clustering and the discovery of materials with analogous electronic properties, even across different chemical and structural families [23].

Diagram 2: Workflow of machine learning frameworks for predicting electronic structure.

Experimental and Data Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: PCA Linear Mapping for Surface DOS Prediction

This protocol enables the prediction of surface density of states from widely available bulk DOS data, using a linear mapping approach [21].

Data Collection:

- Perform bulk and surface DFT calculations for a small set of reference compounds (e.g., Cu–Nb–S, Cu–Ta–S, Cu–V–S) to generate the training data.

- The surface models should be slab-based with appropriate vacuum spacing and atomic relaxation.

Dimensionality Reduction with PCA:

- Compile the bulk and surface DOS spectra for the training set into two separate data matrices.

- Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to each matrix independently. Retain the top n principal components that capture the majority of the variance in the data. This projects the high-dimensional DOS onto a low-dimensional latent space defined by the PCA scores.

Linear Transformation:

- Let ( S{\text{bulk}} ) and ( S{\text{surface}} ) be the matrices of PCA scores for the bulk and surface DOS of the training set, respectively.

- Compute the linear transformation matrix ( M ) that maps bulk scores to surface scores using the least-squares solution: ( M = S{\text{surface}}^T \cdot (S{\text{bulk}}^T)^{\dagger} ), where ( \dagger ) denotes the pseudoinverse.

Prediction for New Compositions:

- For a new compound with a known bulk DOS (e.g., CuCrS), project its bulk DOS onto the pre-trained bulk PCA model to obtain its bulk score vector, ( s_{\text{bulk, new}} ).

- Predict the surface PCA scores: ( s{\text{surface, pred}} = M \cdot s{\text{bulk, new}} ).

- Reconstruct the predicted surface DOS from the predicted scores using the inverse PCA transform.

Protocol 2: DOS Similarity Analysis and Clustering

This protocol details the creation of a DOS fingerprint and its use in unsupervised clustering to identify materials with similar electronic structures [23].

Constructing the DOS Fingerprint:

- Energy Shifting: Shift the DOS spectrum so that a key reference energy (e.g., the Fermi level, ( E_F )) is at zero (( \varepsilon = 0 )).

- Non-uniform Histogramming: Integrate the DOS over an even number (( N\varepsilon )) of intervals of variable widths, ( \Delta \varepsiloni ). The width function is defined as ( \Delta \varepsiloni = n(\varepsiloni, W, N) \Delta \varepsilon{\text{min}} ), where ( n ) is an integer-valued function that increases from 1 to ( N ) as ( |\varepsilon| ) exceeds the feature region width ( W ). This creates a histogram ( {\rhoi} ) with fine resolution near ( \varepsilon=0 ) and coarser resolution elsewhere.

- Pixel Rasterization: Discretize each histogram column i into a grid of ( N\rho ) pixels of height ( \Delta \rhoi ) (also computed with a variable width function). The number of filled pixels in a column is ( \min(\lfloor \rhoi / \Delta \rhoi \rfloor, N_\rho) ).

- The final fingerprint is a binary vector ( \mathbf{f} ) of length ( N\varepsilon \times N\rho ), where each element corresponds to a pixel being filled (1) or not (0).

Calculating Similarity and Clustering:

- Compute the Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) to measure the similarity between two fingerprints ( \mathbf{f}i ) and ( \mathbf{f}j ): ( S(\mathbf{f}i, \mathbf{f}j) = \frac{\mathbf{f}i \cdot \mathbf{f}j}{|\mathbf{f}i|^2 + |\mathbf{f}j|^2 - \mathbf{f}i \cdot \mathbf{f}j} ).

- Apply a clustering algorithm, such as hierarchical clustering or DBSCAN, to the matrix of pairwise Tanimoto similarities to group materials with similar electronic structures.

Cluster Characterization:

- Introduce additional descriptors for atomic composition (e.g., stoichiometry, electronegativity) and crystal structure (e.g., space group, coordination numbers) to rationalize the electronic-structure-based clustering results. This helps identify whether clusters consist of isoelectronic materials, share crystal symmetry, or contain unexpected outliers.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for Electronic Structure Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Dimensionality Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [21] [3] | Public Database | Repository of pre-computed bulk material properties via DFT. | Source of bulk crystal structures and properties for training ML models or as input for surface prediction [21]. |

| Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB) [23] | Public Database | Curated repository of calculated properties for two-dimensional materials. | Benchmark for testing dimensionality effects and applying DOS similarity analysis [23]. |

| Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD) Dataset [3] | ML Training Dataset | Diverse set of structures including molecules, bulks, surfaces, and clusters. | Training universal ML models like PET-MAD-DOS that generalize across dimensionalities and chemistries [3]. |

| Zeroth-Step Hamiltonian (( \mathbf{H}^{(0) )) [22] | Computational Descriptor | Initial Hamiltonian from sum of atomic charge densities. | Physically meaningful input feature for ML models that simplifies learning and improves generalization [22]. |

| DOS Fingerprint [23] | Analytical Descriptor | Binary vector representing a DOS spectrum with tunable focus. | Enables quantitative comparison and unsupervised clustering of materials based on electronic structure similarity [23]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient (Tc) [23] | Similarity Metric | Measures the overlap between two binary fingerprints. | Core metric for quantifying electronic structure similarity in unsupervised learning tasks [23]. |

The manifestation of electronic structure is intrinsically governed by the dimensionality of the material system. From the continuous DOS of 3D bulks to the discrete states of 0D quantum dots, dimensionality imposes fundamental constraints that dictate a material's electronic behavior. The emergence of sophisticated machine learning frameworks, such as universal Hamiltonian predictors and direct DOS models, is revolutionizing our ability to compute and analyze these properties at scale. These tools, combined with robust data analysis protocols for similarity and prediction, provide researchers with an unprecedented capacity to navigate the complex landscape of materials space. This integrated approach—rooted in fundamental physics and accelerated by data-driven methods—is pivotal for the targeted design of next-generation functional materials, where precise control over electronic properties through dimensional engineering is paramount.

Computational Approaches: From Traditional DFT to Modern Machine Learning

The electronic density of states (DOS) is a fundamental property in materials science and quantum chemistry that describes the number of available electron states per unit volume per unit energy range [20]. Formally defined as ( D(E) = N(E)/V ), it quantifies how electronic states are distributed across different energy levels in a material [20]. This function governs crucial bulk material properties including specific heat, paramagnetic susceptibility, and various transport phenomena in conductive solids [24]. In practical terms, the DOS reveals whether a material behaves as a metal, semiconductor, or insulator—for electrons in a semiconductor's conduction band, an increase in energy makes more states available for occupation, while no states are available within the band gap energy range [20].