Electron Configuration and Chemical Periodicity: Foundational Principles and Advanced Applications for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electron configuration principles and chemical periodicity, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electron Configuration and Chemical Periodicity: Foundational Principles and Advanced Applications for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electron configuration principles and chemical periodicity, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It bridges foundational quantum mechanical theories with cutting-edge methodological applications, addressing both standard practices and troubleshooting for complex elements. The content synthesizes traditional rules with emerging experimental techniques, such as novel heavy-element chemistry, and validates these concepts through comparative analysis and computational modeling. A special focus is given to the implications of these principles in designing therapeutic molecules and radioisotopes, offering a roadmap for leveraging periodicity in biomedical innovation.

Quantum Foundations: Understanding the Core Principles of Electron Configuration

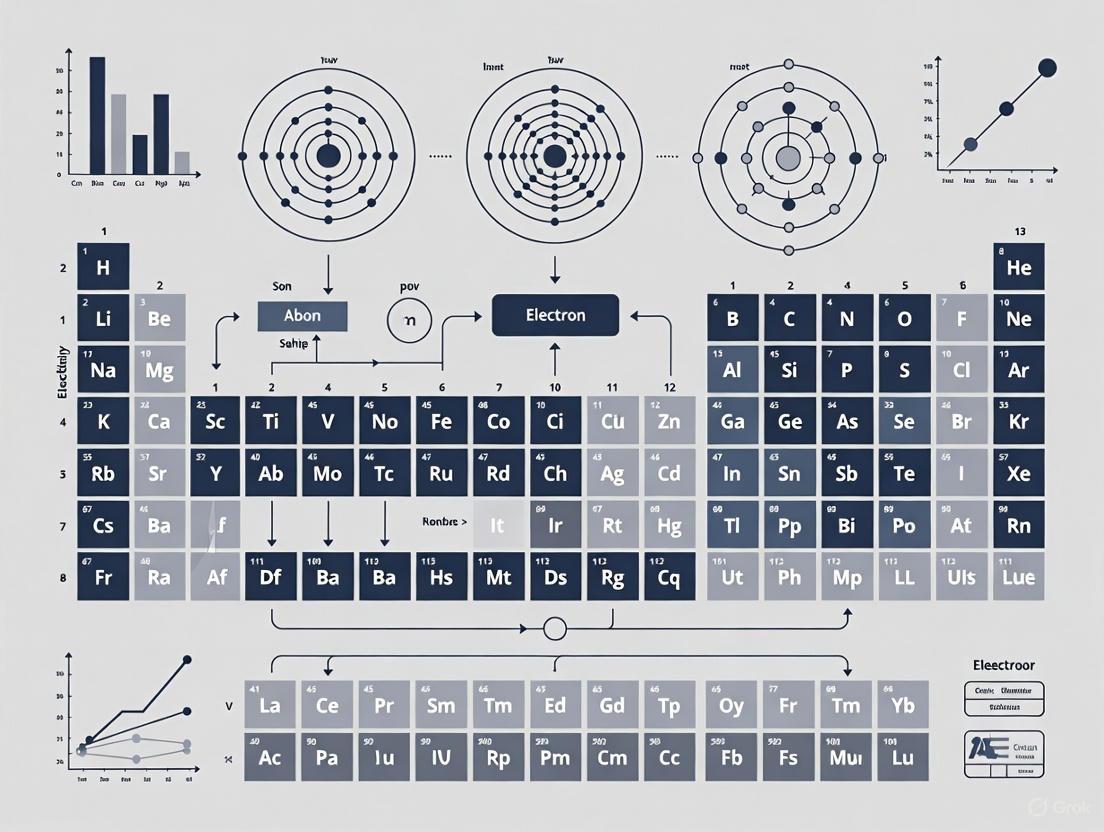

The quantum mechanical model provides the fundamental framework for understanding the behavior of electrons in atoms, which directly governs the chemical and physical properties of the elements. This model represents a revolutionary departure from earlier Bohr models by describing electrons not as particles in fixed orbits but as wavefunctions with probabilistic distributions in three-dimensional space. These wavefunctions, known as atomic orbitals, provide a statistical map of where an electron is most likely to be found around the nucleus. The precise mathematical description of these orbitals, derived from the Schrödinger equation, enables accurate prediction of chemical bonding, reactivity, and the periodic trends that form the foundation of chemical periodicity [1].

Central to this framework is the concept of electron configuration—the distribution of electrons in atomic orbitals following the Aufbau principle, Pauli exclusion principle, and Hund's rule. The arrangement of electrons into successive electron shells (principal energy levels) and subshells (s, p, d, f) directly explains the structure of the periodic table and the observed periodicity of elemental properties. As one moves across a period, electrons fill the same shell with increasing nuclear charge, leading to predictable trends in atomic radius, ionization energy, and electronegativity. Conversely, moving down a group adds new electron shells, resulting in larger atomic radii and modified chemical behavior [1] [2]. This quantum-based understanding of electron organization enables researchers to systematically predict and rationalize chemical behavior across the periodic table.

Core Principles: Orbitals and Electron Organization

Quantum Numbers and Atomic Orbitals

The quantum mechanical model describes each electron in an atom using four quantum numbers that define its energy and spatial distribution:

- Principal quantum number (n): Defines the main energy level or shell (n = 1, 2, 3...), determining the electron's average distance from the nucleus and its overall energy. As n increases, the electron resides further from the nucleus and possesses higher energy.

- Azimuthal quantum number (l): Specifies the subshell shape (l = 0 to n-1, corresponding to s, p, d, f orbitals) and contributes to the electron's angular momentum. The s orbitals (l=0) are spherical, p orbitals (l=1) are dumbbell-shaped, and d and f orbitals exhibit more complex geometries.

- Magnetic quantum number (mₗ): Defines the orbital orientation in space (mₗ = -l to +l), with each value representing a distinct orbital within a subshell.

- Spin quantum number (mₛ): Specifies the electron's intrinsic spin direction (+½ or -½), following the Pauli exclusion principle that no two electrons in an atom can share the same set of all four quantum numbers.

Table 1: Orbital Types and Their Characteristics

| Orbital Type | Angular Momentum Quantum Number (l) | Number of Orientations | Maximum Electron Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| s | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| p | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| d | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| f | 3 | 7 | 14 |

Electron Shells and Subshells

Electron shells are organized hierarchically, with each shell (defined by n) containing n subshells (defined by l), and each subshell containing 2l+1 orbitals. The filling order follows the Aufbau principle, where electrons occupy the lowest energy orbitals available, typically following the Madelung rule (n+l ordering). This systematic organization explains the structure of the periodic table: s-block elements comprise groups 1-2, p-block encompasses groups 13-18, d-block contains transition metals (groups 3-12), and f-block includes the lanthanides and actinides [2].

The periodic recurrence of similar properties at regular intervals—chemical periodicity—stems directly from this quantum mechanical organization. Elements within the same group share similar valence electron configurations, leading to comparable chemical behavior. For instance, all alkali metals (Group 1) possess a single electron in their outermost s orbital, explaining their high reactivity and tendency to form +1 cations. This periodicity enables researchers to predict properties of elements and their compounds, guiding materials design and discovery efforts [1].

Quantitative Data and Periodicity Trends

The quantum mechanical model enables precise prediction and systematization of elemental properties across the periodic table. These quantifiable trends provide critical insights for materials design and compound selection in research applications.

Table 2: Periodic Trends in Atomic Properties

| Property | Trend Across Period (Left to Right) | Trend Down Group | Quantum Mechanical Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Radius | Decreases | Increases | Increasing nuclear charge vs. electron shielding effects |

| Ionization Energy | Increases | Decreases | Increasing nuclear charge makes electron removal more difficult across periods; increased distance and shielding make it easier down groups |

| Electron Affinity | Generally increases (becomes more negative) | Generally decreases | Increased effective nuclear charge favors electron addition across periods; larger atomic size reduces this effect down groups |

| Electronegativity | Increases | Decreases | Combination of ionization energy and electron affinity trends |

These systematic variations stem directly from quantum principles: across periods, increasing nuclear charge without additional electron shielding draws electrons closer to the nucleus, while down groups, the addition of new electron shells outweighs increasing nuclear charge, resulting in larger atoms with more shielded valence electrons [1] [2].

Research Applications in Drug Development and Materials Science

ELECTRUM Fingerprint for Transition Metal Complexes

Transition metal complexes present significant challenges for computational modeling due to their diverse coordination geometries, oxidation states, and electronic structures. The recently developed ELECTRUM fingerprint addresses this gap by creating an electron configuration-based universal descriptor specifically for transition metal compounds [3]. This 598-bit fingerprint incorporates both ligand structural information and the electron configuration of the central metal atom, enabling efficient machine learning applications for predicting coordination numbers and oxidation states.

The ELECTRUM encoding methodology involves:

- Ligand fingerprint generation: Circular substructures are extracted from each ligand SMILES string up to a radius of 2 bonds, hashed, and folded into a 512-bit vector

- Ligand combination: Folded fingerprints for all ligands are combined through bitwise summation, preserving information about repeated ligands

- Metal encoding: An 86-bit binary representation of the metal's electron configuration is appended

- Machine learning integration: The resulting fingerprint trains multilayer perceptron neural networks for property prediction

This approach demonstrates remarkable efficiency, processing approximately 1.2 milliseconds per complex—significantly faster than geometry-based descriptors requiring molecular coordinates and quantum mechanical calculations [3].

Diagram: ELECTRUM Fingerprint Generation Workflow

Quantum Computing in Molecular Simulations

Quantum computing represents a paradigm shift for molecular modeling, particularly for simulating quantum systems that challenge classical computational methods. Quantum processors leverage qubits that exploit superposition and entanglement to perform calculations intractable for classical computers [4]. In pharmaceutical research, this capability enables:

- Protein folding prediction: Precise modeling of protein tertiary structure formation using D-Wave quantum annealers

- Drug-target interactions: Accurate simulation of molecular docking through direct quantum system simulation

- Electronic structure calculation: Determination of ground-state energies for complex molecules with unprecedented accuracy

Industry leaders including Pfizer, Bayer, and Cleveland Clinic have established quantum computing collaborations, with Pfizer and Gero applying hybrid quantum-classical architectures for therapeutic target discovery in fibrotic diseases [4]. Though still emerging, these quantum approaches show potential to significantly accelerate drug discovery timelines and improve success rates in clinical trials.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Coordination Number Prediction Using ELECTRUM

Objective: Predict coordination numbers of transition metal complexes from ligand structures and metal identity using machine learning.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Dataset of transition metal complexes from Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)

- SMILES representations of metal centers and ligands

- ELECTRUM fingerprint generation algorithm

- Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network architecture

- Python implementation with scikit-learn library

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Curate dataset of 217,517 transition metal complexes from CSD

- Represent each complex as concatenated SMILES strings (metal.ligand1.ligand2...)

- Annotate each complex with experimentally determined coordination number

Fingerprint Generation:

- Generate ELECTRUM fingerprints for all complexes using radius 2 and 512-bit ligand fingerprint size

- Include 86-bit metal electron configuration encoding

- Validate fingerprint quality through nearest-neighbor analysis in ELECTRUM space

Model Training:

- Configure MLP with 5 hidden layers (512-256-128-64-32 neurons)

- Implement 5-fold cross-validation with scrambled label controls

- Train models to predict coordination numbers from ELECTRUM encodings

Performance Validation:

- Compare ELECTRUM against control fingerprints (ligands-only and atomic identifier)

- Assess model accuracy on holdout test sets

- Evaluate clustering behavior in two-dimensional representations [3]

Quantum Computing for Molecular Energy Calculations

Objective: Calculate ground-state energy of complex molecules using quantum processors.

Materials and Quantum Resources:

- IBM quantum processor or equivalent quantum processing unit (QPU)

- Classical computing infrastructure for hybrid algorithm implementation

- Molecular structure files for target compounds

- Quantum chemistry software packages (Qiskit, OpenFermion)

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation:

- Map molecular electronic structure to qubit representation using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation

- Prepare initial reference state based on Hartree-Fock calculation

Algorithm Implementation:

- Employ Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) hybrid algorithm

- Design quantum circuit ansatz to prepare trial wavefunctions

- Implement quantum phase estimation for energy measurement

Execution and Optimization:

- Run iterative optimization of circuit parameters on QPU

- Utilize classical computer for parameter update using gradient descent

- Converge to ground-state energy estimate through successive iterations

Validation:

- Compare results with classical computational methods (CCSD(T), DMRG)

- Assess accuracy improvement over classical approximations

- Benchmark computational resource requirements [4]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Chemistry

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELECTRUM Fingerprint | Computational Descriptor | Encodes transition metal complex structure | Predicting coordination numbers from SMILES strings [3] |

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | Hardware | Performs quantum computations | Molecular ground-state energy calculations [4] |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Data Resource | Provides crystallographic data | Training set for metal complex property prediction [3] |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Algorithm | Hybrid quantum-classical computing | Finding molecular electronic ground states [4] |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Neural Network Architecture | Property prediction from fingerprints | Classification of metal complex properties [3] |

Future Directions and Research Applications

The integration of quantum mechanical principles with advanced computational methods continues to expand research capabilities across chemistry and drug development. Several emerging trends demonstrate particular promise:

AI-Enhanced Quantum Chemistry: Machine learning approaches increasingly complement quantum mechanical calculations, with algorithms trained on high-quality quantum chemistry data providing accurate predictions at reduced computational cost. The I-Con framework—a "periodic table" of machine learning algorithms—systematically organizes over 20 classical algorithms into a unified mathematical structure, enabling more efficient development of hybrid approaches [5].

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD): Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, and quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) integrate quantum-derived molecular properties to predict drug behavior across development stages. These "fit-for-purpose" modeling approaches align computational tools with specific research questions from discovery through post-market monitoring [6].

Quantum Machine Learning: The convergence of quantum computing and machine learning creates opportunities for enhanced molecular property prediction, with quantum neural networks potentially offering advantages for specific chemical applications. As quantum hardware advances, these approaches may address currently intractable problems in molecular design and optimization [4].

Diagram: Research Applications of Quantum Principles

The continued refinement of these computational approaches, grounded in the fundamental principles of the quantum mechanical model, promises to accelerate discovery across pharmaceutical development, materials science, and chemical research. By bridging theoretical quantum mechanics with practical application, researchers can more effectively navigate chemical space and design compounds with tailored properties for specific applications.

The electronic structure of an atom is fundamental to its chemical identity, dictating its bonding behavior, reactivity, and physical properties. For researchers and drug development professionals, predicting molecular behavior and interactions hinges on a precise understanding of these electronic foundations. The ground-state electron configuration of an atom is not arbitrary but is governed by a set of fundamental quantum mechanical rules: the Aufbau Principle, Hund's Rule, and the Pauli Exclusion Principle [7]. Together, these rules provide a systematic framework for determining how electrons occupy atomic orbitals, forming the bedrock of our understanding of chemical periodicity and the structure of the periodic table itself. This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of these core principles, framing them within ongoing research into chemical periodicity and their practical implications for material science and pharmaceutical development.

The Aufbau Principle: The "Building-Up" Process

Core Concept and Theoretical Basis

The term "Aufbau" originates from the German word "Aufbauprinzip," meaning "building-up principle" [8]. This principle states that in the ground state of an atom or ion, electrons populate atomic orbitals in a sequential order of increasing orbital energy [9]. The fundamental tenet is that electrons will always occupy the lowest energy orbitals available before filling higher energy ones [10]. This process resembles the construction of a building from the foundation upward, ensuring the most stable, lowest-energy electron configuration is achieved for the atom [7] [10].

The Madelung Energy Ordering Rule

The order of orbital filling is empirically described by the Madelung energy ordering rule (also known as the n + ℓ rule) [9]. This rule provides a reliable method for predicting the sequence of orbital occupation:

- Rule 1: Electrons are assigned to subshells in order of increasing value of the sum n + ℓ, where n is the principal quantum number and ℓ is the azimuthal quantum number.

- Rule 2: For subshells with an identical n + ℓ value, the subshell with the lower n value is filled first [9].

Table: Madelung Orbital Filling Sequence

| Orbital Subshell | n value | ℓ value | n + ℓ value | Filling Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1s | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2s | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 2p | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 3s | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| 3p | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 4s | 4 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 3d | 3 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| 4p | 4 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| 5s | 5 | 0 | 5 | 9 |

| 4d | 4 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| 5p | 5 | 1 | 6 | 11 |

| 6s | 6 | 0 | 6 | 12 |

| 4f | 4 | 3 | 7 | 13 |

| 5d | 5 | 2 | 7 | 14 |

| 6p | 6 | 1 | 7 | 15 |

| 7s | 7 | 0 | 7 | 16 |

| 5f | 5 | 3 | 8 | 17 |

| 6d | 6 | 2 | 8 | 18 |

This ordering explains the structure of the periodic table, particularly the placement of the lanthanide and actinide series (f-block elements) [9]. The following diagram visualizes the sequence in which orbitals are filled according to the Aufbau principle and the Madelung rule.

Notable Exceptions to the Aufbau Principle

While the Madelung rule provides a robust general guide, several notable exceptions exist, primarily within the d-block and f-block elements. These exceptions occur when the energy difference between subshells is minimal, and the stability gained from half-filled or fully filled subshells compensates for the energy required to "promote" an electron [7] [9].

Table: Common Exceptions to the Aufbau Principle in the d-Block

| Atom | Atomic Number (Z) | Madelung-Predicted Configuration | Experimental Ground-State Configuration | Reason for Exception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromium | 24 | [Ar] 3d⁴ 4s² | [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹ | Energy stabilization of half-filled d⁵ |

| Copper | 29 | [Ar] 3d⁹ 4s² | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s¹ | Energy stabilization of fully filled d¹⁰ |

| Niobium | 41 | [Kr] 4d³ 5s² | [Kr] 4d⁴ 5s¹ | Proximity of 4d and 5s energy levels |

| Molybdenum | 42 | [Kr] 4d⁴ 5s² | [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s¹ | Energy stabilization of half-filled d⁵ |

| Silver | 47 | [Kr] 4d⁹ 5s² | [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s¹ | Energy stabilization of fully filled d¹⁰ |

| Gold | 79 | [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁹ 6s² | [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s¹ | Energy stabilization of fully filled d¹⁰ |

These exceptions are critical for researchers to recognize, as the altered electron configurations can significantly influence the oxidation states and catalytic properties of transition metals used in synthetic chemistry and drug design.

Hund's Rule: Maximizing Multiplicity

Rule Definition and Formulation

Hund's Rule addresses the filling of degenerate orbitals—orbitals that possess the same energy, such as the three p orbitals, five d orbitals, or seven f orbitals within a given subshell [11]. The rule consists of two main parts [12] [13]:

- For a given electron configuration, the state with the maximum multiplicity lies lowest in energy. Multiplicity is given by 2S+1, where S is the total spin quantum number. In practical terms, this means every orbital in a subshell is singly occupied with one electron before any one orbital is doubly occupied.

- For states with the same multiplicity, the state with the largest total orbital angular momentum quantum number (L) has the lowest energy. This aspect is more relevant for determining term symbols in atomic spectroscopy.

A third rule deals with spin-orbit coupling to determine the fine structure of atomic spectra, but the first rule is the most critical for understanding basic electron configurations in chemistry [12].

Physical Rationale and Implications

The physical basis for Hund's first rule is the minimization of electron-electron repulsion. When electrons occupy different orbitals, they are, on average, farther apart than if they were paired in the same orbital, thereby reducing Coulombic repulsion [11]. Furthermore, quantum-mechanical calculations indicate that electrons in singly occupied orbitals are less effectively screened from the nucleus, causing these orbitals to contract and increasing the electron-nucleus attraction energy [12]. The rule also mandates that all electrons in singly occupied orbitals possess the same spin (parallel spins), which is a consequence of the quantum mechanical requirement for an antisymmetric total wavefunction [11].

The application of Hund's rule is visualized below for the carbon atom, which has two electrons in its 2p subshell.

Experimental Validation via Spectroscopy

Methodology: The most direct experimental validation of Hund's rule comes from atomic emission and absorption spectroscopy. By analyzing the spectral lines of atoms, scientists can determine the energy differences between various electronic states and identify the ground state.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A pure sample of the element (e.g., nitrogen or oxygen in gaseous form) is placed in a discharge tube or a suitable cell for spectroscopic analysis.

- Energy Input: Energy is supplied to the sample via an electric discharge (for gases) or heat, promoting electrons to excited states.

- Spectral Acquisition: As electrons return to lower energy states, they emit photons of specific wavelengths. The emitted light is passed through a diffraction grating or prism to separate it into its constituent wavelengths, creating an emission spectrum.

- Data Analysis: The resulting spectrum is analyzed. The intensity and spacing of the spectral lines correspond to transitions between different electronic energy levels. For atoms like nitrogen, the spectral data confirms that the ground state is a triplet state with three unpaired electrons, each residing in a separate 2p orbital with parallel spins, consistent with Hund's rule [11]. Deviations from the predicted ground state would manifest as unexpected spectral lines or intensities.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle: The Quantum Identity Card

Fundamental Statement

Formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, the Pauli Exclusion Principle is a fundamental quantum mechanical law stating that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers (n, ℓ, mℓ, m𝑠) [14] [15]. Since the first three quantum numbers (n, ℓ, mℓ) define a specific atomic orbital, the principle directly implies that an atomic orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, and these two electrons must have opposite spins (m𝑠 = +1/2 and m𝑠 = -1/2) [7] [14].

A more rigorous, generalized statement for multi-electron systems is that the total wavefunction of a system of identical fermions (particles with half-integer spin, like electrons) must be antisymmetric with respect to the exchange of any two particles [15]. This means if the coordinates (both spatial and spin) of two electrons are swapped, the total wavefunction changes sign.

Consequences for Atomic Structure and Chemistry

The Pauli Exclusion Principle has profound implications:

- It defines electron shell capacity. The maximum number of electrons in a shell is 2n² and in a subshell is 2(2ℓ + 1) [9].

- It explains the large-scale stability of matter. Without this principle, all electrons in an atom would collapse into the 1s orbital, leading to a complete loss of chemical diversity as all atoms would have similar, compact configurations [15].

- It underpins the periodic table's structure. The sequential filling of orbitals, constrained by the Pauli principle, gives rise to the periods and groups of the periodic table [15].

Table: Quantum Number Combinations and Orbital Capacities

| Subshell | ℓ value | mℓ values | Number of Orbitals | Max Electrons (2 per orbital) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| p | 1 | -1, 0, +1 | 3 | 6 |

| d | 2 | -2, -1, 0, +1, +2 | 5 | 10 |

| f | 3 | -3, -2, -1, 0, +1, +2, +3 | 7 | 14 |

The following diagram illustrates the application of all three rules for the electron configuration of a carbon atom.

Integrated Workflow for Determining Electron Configurations

Determining the ground-state electron configuration for any element requires the simultaneous application of all three rules. The following workflow provides a robust methodology for researchers.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Determine Total Electrons: Identify the number of electrons (Z) from the atomic number of the neutral element.

- Apply Aufbau Order: Refer to the Madelung (n + ℓ) rule sequence to add electrons to orbitals in the correct energy order (1s → 2s → 2p → 3s → 3p → 4s → 3d...).

- Apply Hund's Rule: When filling a degenerate subshell (p, d, f), place one electron in each available orbital with parallel spins before pairing any electrons.

- Apply Pauli Exclusion Principle: Ensure that no orbital contains more than two electrons, and that any paired electrons are represented with opposite spins.

- Check for Known Exceptions: For transition metals like Cr, Cu, Ag, and others, consult tables of known exceptions where half-filled or fully filled subshells provide extra stability.

Example: Oxygen (Z = 8)

- Step 1: 8 electrons total.

- Step 2 (Aufbau): 2 electrons fill 1s. 2 electrons fill 2s. The remaining 4 electrons go to the 2p subshell.

- Step 3 (Hund's): Three of the four 2p electrons singly occupy each of the three 2p orbitals with parallel spins.

- Step 4 (Pauli): The fourth 2p electron pairs up with one of the existing electrons in a 2p orbital, with opposite spin.

- Final Configuration: 1s² 2s² 2p⁴. The orbital diagram shows two singly occupied 2p orbitals (with parallel spins) and one doubly occupied 2p orbital [11].

Table: Key Reagents, Materials, and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Elements | Material | Serve as the fundamental subject for experimental spectroscopic analysis. | Gas-phase studies of atomic spectra for rule validation. |

| Atomic Emission Spectrometer | Instrumentation | Precisely measures the wavelengths of light emitted by excited atoms to determine energy-level differences. | Experimentally confirming the ground-state term symbol predicted by Hund's rules. |

| Computational Chemistry Software | Software | Performs quantum mechanical calculations to predict electronic structure, energies, and properties from first principles. | Modeling electron densities, calculating total energies of different electron configurations to verify stability. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS) | Instrumentation | Probes the core energy levels of atoms in molecules or materials, providing direct evidence of electron configuration and oxidation states. | Determining the oxidation state of a transition metal catalyst in a drug synthesis intermediate. |

| High-Resolution Laser Systems | Instrumentation | Allows for precision spectroscopy to resolve fine and hyperfine structure in atomic spectra. | Investigating spin-orbit coupling effects detailed by Hund's third rule. |

The Aufbau Principle, Hund's Rule, and the Pauli Exclusion Principle are not merely academic rules but are indispensable tools for predicting and rationalizing the electronic behavior of atoms. For professionals in drug development and materials science, these principles provide the foundational logic for understanding the behavior of metal catalysts in synthetic pathways, the redox chemistry of biological systems, and the design of novel materials with tailored electronic properties. While the rules provide an excellent predictive model, awareness of their exceptions is equally critical, as these often reveal elements with unique and useful reactivities. Continued research into the nuances of electron configuration remains vital for advancing our understanding of chemical periodicity and its applications across the scientific spectrum.

This technical guide provides researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for understanding and applying the principles of orbital notation and energy level ordering within the broader context of chemical periodicity and electron configuration research. The precise arrangement of electrons in atomic orbitals fundamentally dictates the chemical behavior, bonding characteristics, and physical properties of elements, making this knowledge essential for advanced research applications including rational drug design and materials development. We present detailed methodologies, quantitative data frameworks, and visualization tools to enable accurate prediction and interpretation of electronic configurations across the periodic table, with particular emphasis on transition metals and their coordination complexes which prove particularly relevant to pharmaceutical applications.

The modern understanding of electron configuration derives from quantum mechanics, where atomic orbitals are defined as mathematical functions describing the location and wave-like behavior of electrons in atoms [16]. These orbitals represent three-dimensional regions where electrons have the highest probability of being found, with their shapes and energies determined by quantum numbers [17]. The principal quantum number (n = 1, 2, 3, ...) determines the overall energy level and size of the orbital, while the orbital angular momentum quantum number (ℓ) defines the subshell shape (s, p, d, f), and the magnetic quantum number (mℓ) specifies the orbital orientation in space [17]. Each orbital can accommodate a maximum of two electrons with opposing spins, in accordance with the Pauli exclusion principle [16].

The arrangement of electrons within these orbitals follows specific principles based on energy minimization, which systematically dictates the building up of elements in the periodic table. This quantum mechanical framework provides the foundation for understanding chemical periodicity, as elements with similar electron configurations in their outermost shells display comparable chemical properties. For drug development professionals, this understanding enables prediction of molecular reactivity, binding interactions, and coordination chemistry essential to pharmaceutical design.

Fundamental Principles of Energy Level Ordering

The Aufbau Principle

The Aufbau principle (from the German "Aufbau" meaning "building up") provides the foundational rule for determining the order in which atomic orbitals are filled with electrons [18]. This principle states that electrons occupy the lowest energy orbitals available first, before filling higher energy levels. The conventional ordering of orbital energies follows the pattern:

1s < 2s < 2p < 3s < 3p < 4s < 3d < 4p < 5s < 4d < 5p < 6s < 4f < 5d < 6p < 7s < 5f < 6d < 7p

This sequence can be visualized and applied using the diagonal rule or mnemonic devices, but most effectively utilized through direct periodic table inspection [18]. The periodic table's structure directly reflects this orbital filling order, with each block (s, p, d, f) corresponding to the subshell being filled.

Hund's Rule and Pauli Exclusion Principle

Two additional quantum mechanical rules complete the framework for determining electron configurations:

- Hund's Rule: For orbitals of equal energy (degenerate orbitals), electrons occupy available orbitals singly before pairing up. This maximum multiplicity rule minimizes electron-electron repulsions [18].

- Pauli Exclusion Principle: No two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers. Consequently, any single orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, and these must have opposite spins [17] [16].

These principles collectively explain why, for example, the three 2p orbitals of nitrogen (1s²2s²2p³) contain one electron each, all with parallel spins, rather than having paired electrons in fewer orbitals.

Orbital Capacities and Quantum Numbers

Table 1: Orbital Types, Quantum Numbers, and Electron Capacities

| Orbital Type | Angular Momentum Quantum Number (ℓ) | Magnetic Quantum Numbers (mℓ) | Number of Orbitals | Maximum Electrons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| p | 1 | -1, 0, +1 | 3 | 6 |

| d | 2 | -2, -1, 0, +1, +2 | 5 | 10 |

| f | 3 | -3, -2, -1, 0, +1, +2, +3 | 7 | 14 |

The subshell electron capacities derive directly from the quantum numbers: each subshell can hold up to 2(2ℓ + 1) electrons [17]. These fundamental capacities establish the structure of the periodic table, with s-block encompassing 2 elements, p-block 6 elements, d-block 10 elements, and f-block 14 elements.

Methodologies for Determining Electron Configurations

Standard Notation Protocol

The following step-by-step methodology provides a reliable approach for writing electron configurations for any neutral atom:

- Determine Atomic Number: Identify the number of electrons from the element's atomic number (Z).

- Follow Orbital Energy Order: Fill orbitals sequentially according to the established energy ordering principle, respecting orbital capacities.

- Apply Hund's Rule: When placing electrons in degenerate orbitals (p, d, f), fill each orbital singly with parallel spins before pairing.

- Verify Total Electrons: Confirm that the sum of superscripts in the configuration equals the atomic number.

Example: Oxygen (Z = 8)

- Application: 1s² 2s² 2p⁴ (with the 2p subshell containing two singly-occupied orbitals and one paired orbital)

Noble Gas Core Abbreviation

For elements with higher atomic numbers, configurations can be abbreviated by referencing the previous noble gas configuration in brackets, followed by the remaining valence electrons [18]. This notation emphasizes the valence electron structure most relevant to chemical bonding.

Examples:

- Sodium (Z = 11): [Ne] 3s¹

- Iron (Z = 26): [Ar] 4s² 3d⁶

Exceptional Configurations

Several transition metals exhibit deviations from predicted configurations due to the extra stability associated with half-filled and completely filled d subshells [18]. These exceptions highlight the subtle energy balances between closely-spaced orbitals.

Table 2: Exceptional Electron Configurations in Transition Metals

| Element | Predicted Configuration | Actual Configuration | Stabilization Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromium (Z=24) | [Ar] 4s² 3d⁴ | [Ar] 4s¹ 3d⁵ | Half-filled d subshell |

| Copper (Z=29) | [Ar] 4s² 3d⁹ | [Ar] 4s¹ 3d¹⁰ | Fully filled d subshell |

| Silver (Z=47) | [Kr] 5s² 4d⁹ | [Kr] 5s¹ 4d¹⁰ | Fully filled d subshell |

| Gold (Z=79) | [Xe] 6s² 4f¹⁴ 5d⁹ | [Xe] 6s¹ 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ | Fully filled d subshell |

These exceptions demonstrate that energy differences between ns and (n-1)d orbitals are small enough that the stability gains from half-filled or fully filled subshells can alter the expected filling order.

Experimental Determination Methodologies

Spectroscopic Techniques

Experimental verification of electron configurations primarily relies on spectroscopic methods that probe electronic energy levels:

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy: Measures electronic transitions between orbitals, providing direct evidence of energy separations [19] [20]. The absorption spectra of coordination complexes, for example, reveal d-orbital splitting patterns that confirm the electronic structure.

Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Directly measures the ionization energies of electrons from specific orbitals, providing experimental evidence for orbital energy ordering and occupation.

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurements

The number of unpaired electrons in a species can be determined through magnetic susceptibility measurements, providing experimental confirmation of predictions based on Hund's rule [18]. Paramagnetic species with unpaired electrons are attracted to magnetic fields, while diamagnetic species with all electrons paired are weakly repelled.

Computational Approaches

Modern computational chemistry employs density functional theory (DFT) and other quantum mechanical methods to calculate electron distributions and orbital energies [21]. These approaches can predict electric anisotropies and polarizabilities that derive from specific electron configurations, providing theoretical confirmation of experimental observations.

Diagram 1: Electron configuration determination workflow (27 words)

Advanced Concepts: Coordination Complexes and d-Orbital Splitting

In coordination chemistry, which is particularly relevant to metallodrugs and catalytic systems, the presence of ligands alters the energy ordering of d-orbitals in transition metals through crystal field effects [19]. This splitting has profound implications for the optical and magnetic properties of coordination compounds.

Crystal Field Theory

When ligands approach a transition metal center, they create an electrostatic field that splits the degeneracy of the d-orbitals [19]. In octahedral complexes, this results in two distinct energy levels: the higher energy eg orbitals (dx²-y² and dz²) and the lower energy t2g orbitals (dxy, dxz, dyz). The energy separation between these sets is designated as Δo (the crystal field splitting parameter).

Spectrochemical Series

The magnitude of d-orbital splitting depends on the ligand type, with the spectrochemical series organizing ligands from weak field (small Δo) to strong field (large Δo):

I⁻ < Br⁻ < Cl⁻ < F⁻ < OH⁻ < H₂O < NH₃ < CN⁻ < CO

Weak field ligands typically produce high-spin complexes (maximum unpaired electrons), while strong field ligands favor low-spin complexes (minimum unpaired electrons) [19]. This distinction is crucial for predicting magnetic properties and coloration in coordination compounds relevant to pharmaceutical applications.

Color Origin in Coordination Complexes

The colors observed in transition metal complexes result from d-d transitions, where electrons absorb photons of visible light to jump from lower-energy to higher-energy d-orbitals [20]. The specific wavelengths absorbed depend on Δo, with complementary colors transmitted to produce the observed coloration.

Diagram 2: Color origin in coordination complexes (26 words)

Table 3: Relationship Between Absorbed Wavelength and Observed Color in Complexes

| Complex | Absorbed Wavelength (nm) | Absorbed Color | Observed Color | Δo (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Ti(H₂O)₆]³⁺ | 450-600 (max 499) | Orange-Red | Purple | 239 |

| [Cu(NH₃)₄]²⁺ | 600-650 | Red | Blue | 184-200 |

| [Cu(H₂O)₆]²⁺ | 500-600 | Orange-Green | Blue | 200-240 |

The relationship between the crystal field splitting energy and the absorbed wavelength is given by Δo = hc/λ, where h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and λ is the wavelength of the absorbed photon [20]. This quantitative relationship allows researchers to calculate orbital energy separations from experimental absorption spectra.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Electron Configuration Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures absorption spectra of solutions | Determining d-d transition energies in coordination complexes [19] [20] |

| Ligand Series (Halides to CN⁻) | Creates crystal field of varying strength | Investigating spectrochemical series effects on Δo [19] |

| Magnetic Susceptibility Balance | Detects unpaired electrons | Confirming high-spin vs. low-spin configurations [19] |

| Computational Software (DFT) | Calculates electron distributions | Predicting orbital energies and charge anisotropies [21] |

| High-Purity Transition Metal Salts | Source of metal centers | Preparing coordination complexes with defined geometry |

| Inert Atmosphere Equipment | Prevents oxidation during synthesis | Handling air-sensitive organometallic compounds |

Implications for Chemical Periodicity and Pharmaceutical Research

The systematic understanding of orbital notation and energy level ordering provides the fundamental basis for explaining chemical periodicity. Elements within the same group share similar valence electron configurations, which directly dictates their chemical behavior and reactivity patterns [18].

In pharmaceutical research, this framework enables rational design of metallodrugs and diagnostic agents by predicting:

- Metal-ligand coordination preferences based on electron configuration and crystal field stabilization energies

- Redox behavior of transition metal centers in biological systems

- Spectroscopic properties for imaging and detection applications

- Structure-activity relationships in metal-containing pharmaceuticals

The deformation of electron charge distributions around atomic nuclei, as revealed through polarizability anisotropy studies [21], further refines our understanding of how electron configurations influence intermolecular interactions and binding affinities - crucial considerations in drug-receptor interactions.

Orbital notation and energy level ordering represent fundamental organizing principles in chemistry that directly derive from quantum mechanical descriptions of atomic structure. The methodologies and experimental approaches outlined in this guide provide researchers with robust tools for determining, verifying, and applying electron configurations across the periodic table. For drug development professionals, this knowledge enables predictive understanding of molecular properties, reactivity patterns, and spectroscopic behaviors essential to rational design of pharmaceutical compounds. The continued refinement of these principles through advanced spectroscopic and computational methods continues to enhance their utility in cutting-edge chemical research.

The electron configuration of an element describes the distribution of its electrons within the atomic orbitals surrounding the nucleus [18] [22]. This arrangement is governed by the principles of quantum mechanics and provides the foundational framework for understanding the periodic table's structure. The organization of elements into distinct blocks—s, p, d, and f—directly reflects the specific atomic orbitals that are being filled with electrons as the atomic number increases [23]. This systematic filling order, formalized by the Aufbau principle, alongside the Pauli exclusion principle and Hund's rule, dictates the chemical behavior and properties of elements [24]. For researchers in drug discovery and materials science, a deep understanding of these electronic structures is not merely academic; it is crucial for rational design, enabling the prediction of bonding behavior, reactivity, and the physical properties of compounds [25] [26]. The periodic table, therefore, serves as a powerful predictive map, where an element's position immediately reveals its valence electron configuration and thus its potential chemical character.

Characteristics of the s, p, d, and f Blocks

The periodic table is partitioned into blocks based on the type of atomic orbital that accepts the valence electron. This classification system offers immediate insight into the electronic structure and, consequently, the chemical properties of the elements.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Periodic Table Blocks

| Block | Orbital Filled | Group(s) | Valence Electron Configuration | General Chemical Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s-block | s orbital | 1, 2 (and He) | ns¹⁻² | Highly reactive metals (except H, He); form +1 or +2 cations [27]. |

| p-block | p orbital | 13-18 | ns² np¹⁻⁶ | Contains all non-metals, metalloids, and some metals; diverse chemistry [27]. |

| d-block | d orbital | 3-12 | (n-1)d¹⁻¹⁰ ns⁰⁻² | Transition metals; form colored complexes, multiple oxidation states [23]. |

| f-block | f orbital | Lanthanides & Actinides | (n-2)f¹⁻¹⁴ (n-1)d⁰⁻¹ ns² | Inner transition metals; typically +3 oxidation state; lanthanides are chemically very similar [23]. |

The s-Block Elements

The s-block encompasses Group 1 (alkali metals) and Group 2 (alkaline earth metals), along with hydrogen and helium. These elements are characterized by their valence electrons occupying the s orbital. Alkali metals have a configuration ending in ns¹, and alkaline earth metals end in ns² [27]. A key trait of s-block elements is their tendency to lose their valence s-electrons to form stable cations, achieving the electron configuration of the preceding noble gas. This results in common +1 and +2 oxidation states, respectively [18]. This strong electropositive character makes them highly reactive, particularly with water and oxygen.

The p-Block Elements

Spanning Groups 13 to 18, the p-block is incredibly diverse, containing non-metals, metalloids, and post-transition metals. The valence shell configuration ranges from ns² np¹ to ns² np⁶ (the latter being the noble gases) [27]. The octet rule is a dominant concept in p-block chemistry, with elements often gaining, losing, or sharing electrons to achieve a full shell of eight electrons [27]. This block exhibits the most varied range of bonding types, from covalent network solids (e.g., silicon) to diatomic gases (e.g., oxygen) and noble gases. Halogens (Group 17), with their ns² np⁵ configuration, are highly reactive non-metals seeking one electron to complete their octet.

The d-Block Elements

The d-block, or transition metals, occupies the central portion of the periodic table (Groups 3-12). Their electron configuration involves the filling of the inner (n-1)d orbitals, typically denoted as (n-1)d¹⁻¹⁰ ns¹⁻² [23]. A hallmark of these elements is the occurrence of exceptions to the Aufbau principle, notably in chromium ([Ar] 4s¹ 3d⁵) and copper ([Ar] 4s¹ 3d¹⁰), where a half-filled or fully filled d subshell provides extra stability [18] [28]. Transition metals are renowned for their ability to form multiple oxidation states, paramagnetic compounds, and brightly colored complexes, properties driven by the involvement of d-orbitals in bonding.

The f-Block Elements

The f-block consists of the lanthanide and actinide series, where the 4f and 5f orbitals are progressively filled. Their general electron configuration is (n-2)f¹⁻¹⁴ (n-1)d⁰⁻¹ ns² [23]. The lanthanides are particularly known for their striking chemical similarity to one another, as the addition of f-electrons, which are deeply buried and shielded, has minimal impact on their chemical properties. They almost exclusively exhibit a +3 oxidation state. The actinides, especially the heavier members, are radioactive and often display more complex and varied chemistry.

Quantitative Data: Electron Configurations Across the Periodic Table

The following table provides the ground-state electron configurations for the first 36 elements, demonstrating the systematic application of the Aufbau principle and the structure of the s, p, and d blocks [28].

Table 2: Electron Configurations of Elements (Atomic Numbers 1-36)

| Atomic Number | Element | Block | Full Electron Configuration | Noble Gas (Shorthand) Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydrogen | s | 1s¹ | 1s¹ |

| 2 | Helium | s | 1s² | 1s² |

| 3 | Lithium | s | 1s² 2s¹ | [He] 2s¹ |

| 4 | Beryllium | s | 1s² 2s² | [He] 2s² |

| 5 | Boron | p | 1s² 2s² 2p¹ | [He] 2s² 2p¹ |

| 6 | Carbon | p | 1s² 2s² 2p² | [He] 2s² 2p² |

| 7 | Nitrogen | p | 1s² 2s² 2p³ | [He] 2s² 2p³ |

| 8 | Oxygen | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁴ | [He] 2s² 2p⁴ |

| 9 | Fluorine | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁵ | [He] 2s² 2p⁵ |

| 10 | Neon | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ | [He] 2s² 2p⁶ |

| 11 | Sodium | s | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s¹ | [Ne] 3s¹ |

| 12 | Magnesium | s | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² | [Ne] 3s² |

| 13 | Aluminum | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p¹ | [Ne] 3s² 3p¹ |

| 14 | Silicon | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p² | [Ne] 3s² 3p² |

| 15 | Phosphorus | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p³ | [Ne] 3s² 3p³ |

| 16 | Sulfur | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁴ | [Ne] 3s² 3p⁴ |

| 17 | Chlorine | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁵ | [Ne] 3s² 3p⁵ |

| 18 | Argon | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ | [Ne] 3s² 3p⁶ |

| 19 | Potassium | s | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s¹ | [Ar] 4s¹ |

| 20 | Calcium | s | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² | [Ar] 4s² |

| 21 | Scandium | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹ 4s² | [Ar] 3d¹ 4s² |

| 22 | Titanium | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d² 4s² | [Ar] 3d² 4s² |

| 23 | Vanadium | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d³ 4s² | [Ar] 3d³ 4s² |

| 24 | Chromium* | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁵ 4s¹ | [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹ |

| 25 | Manganese | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁵ 4s² | [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s² |

| 26 | Iron | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁶ 4s² | [Ar] 3d⁶ 4s² |

| 27 | Cobalt | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁷ 4s² | [Ar] 3d⁷ 4s² |

| 28 | Nickel | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁸ 4s² | [Ar] 3d⁸ 4s² |

| 29 | Copper* | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s¹ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s¹ |

| 30 | Zinc | d | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² |

| 31 | Gallium | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p¹ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p¹ |

| 32 | Germanium | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p² | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p² |

| 33 | Arsenic | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p³ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p³ |

| 34 | Selenium | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁴ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁴ |

| 35 | Bromine | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁵ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁵ |

| 36 | Krypton | p | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ |

*Indicates an exception to the typical filling order, demonstrating the stability of half-filled (Cr) and fully-filled (Cu) d subshells.

Advanced Research Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Protocol: Determining Electron Configuration via Atomic Spectroscopy

Theoretical predictions of electron configuration, such as those derived from the Aufbau principle, require experimental validation. Atomic emission and absorption spectroscopy serve as primary methods for this purpose.

- Sample Preparation: A pure sample of the element is vaporized and atomized within a high-temperature source, such as an arc, spark, or inductively coupled plasma (ICP) torch. For gaseous elements, the sample is simply introduced into a discharge tube.

- Excitation: The atoms are energized (excited) by the thermal energy of the source or by an electrical discharge. This promotes electrons from their ground-state orbitals to higher-energy, excited-state orbitals.

- Emission/Absorption:

- In emission spectroscopy, the excited electrons spontaneously relax back to lower energy levels, emitting photons of specific wavelengths. The emitted light is collected.

- In absorption spectroscopy, a broadband light source is passed through the vaporized sample. Atoms absorb specific wavelengths of light, promoting electrons to higher energy levels. The transmitted light is analyzed for missing wavelengths.

- Dispersion and Detection: The collected light is passed through a monochromator (e.g., a diffraction grating) to separate it into its constituent wavelengths, creating a spectrum.

- Data Analysis: The resulting spectrum consists of discrete lines. The wavelengths of these lines are used to calculate the energy differences between atomic orbitals using the Rydberg formula and the relation ( E = hc/\lambda ). By analyzing the complete set of possible transitions, the energy levels of the atom can be mapped, thereby confirming its ground-state electron configuration.

Computational Protocol: Employing Semi-Empirical Methods for Drug Discovery Applications

Modern computational chemistry uses sophisticated methods to model electron configurations in complex molecules, which is vital for drug discovery [29]. These methods provide a "universal force field" capable of modeling drug-like molecules, including their tautomers and protonation states.

- System Setup: The molecular system of interest (e.g., a ligand or a ligand-protein complex) is constructed, and its initial 3D geometry is defined.

- Method Selection: A semi-empirical quantum mechanical (QM) method is chosen. Common choices include:

- NDDO-based methods: PM6, PM7, ODM2. These methods neglect certain diatomic differential overlaps to drastically reduce computational cost while parameterizing remaining integrals to experimental data [29].

- Density-Functional Tight-Binding (DFTB): DFTB3, which is a further approximation of Density Functional Theory (DFT), offers a good balance of speed and accuracy [29].

- Hybrid QM/Machine Learning (QM/Δ-MLP): State-of-the-art methods like AIQM1 and QDπ use a semi-empirical QM model as a base and apply a machine-learned correction to achieve accuracy near high-level ab initio methods, crucial for predicting binding free energies [29].

- Geometry Optimization: The initial structure is computationally relaxed to find its minimum energy configuration, where the electron distribution and nuclear positions are in equilibrium.

- Property Calculation: The optimized structure and its electron configuration are used to calculate key properties for drug discovery:

- Partial atomic charges and molecular electrostatic potential.

- Orbital energies (HOMO-LUMO gap), indicative of reactivity.

- Conformational energies and intermolecular interaction energies (e.g., with a protein target).

- Energetics of different tautomers and protonation states.

- Validation: Computational results are validated against experimental data (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or cryo-Electron Microscopy) or higher-level, but more computationally expensive, ab initio calculations.

Visualization of Electron Configuration and Periodicity

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the Aufbau principle, the resulting electron configuration, and the structure of the periodic table, highlighting how this foundational knowledge connects to modern technological applications.

Diagram Title: From Aufbau Principle to Technological Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Electronic Structure Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Source | A high-temperature plasma (~6000-10000 K) used to efficiently vaporize, atomize, and excite electrons in a wide range of elemental samples. | Experimental determination of elemental composition and electron energy levels via ICP-Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES). |

| Styrene Maleic Acid (SMA) Copolymer | A polymer used to extract membrane proteins directly from the lipid bilayer, forming "SMALPs" that preserve the protein's native lipid environment [26]. | Enables more native-like structural studies of membrane proteins (~60% of drug targets) via Cryo-EM and other techniques. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | A structural biology technique where protein samples are flash-frozen and imaged with electrons to determine high-resolution 3D structures [26]. | Visualizing protein-ligand complexes and conformational states critical for structure-based drug design, informed by electronic properties. |

| Semi-Empirical QM Software (e.g., MOPAC) | Software implementing methods like PM6 and PM7 for rapid quantum mechanical calculations on large molecular systems [29]. | Initial geometry optimizations, conformational searching, and property prediction for drug-like molecules. |

| Hybrid QM/ML Potentials (e.g., QDπ, AIQM1) | Advanced computational models that correct fast semi-empirical QM methods with machine learning to achieve high accuracy [29]. | Highly accurate calculation of binding energies, tautomerization, and protonation state energetics in drug discovery. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes | Ab initio computational methods for solving the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and solids using functionals of the electron density. | Providing benchmark reference data for training ML potentials and detailed electronic structure analysis (e.g., orbital interactions). |

The intrinsic link between electron configuration and the periodic table's s, p, d, and f blocks provides the fundamental language of chemistry. This framework allows scientists to predict and rationalize the behavior of elements, from the violent reactivity of an s-block metal to the catalytic versatility of a d-block transition metal. For professionals in drug development and materials science, this knowledge moves beyond theory into practical application. The ability to understand and compute electronic structures enables the rational design of novel semiconductors like gallium nitride (GaN) for power electronics [25], and is increasingly critical in drug discovery for accurately modeling the behavior of small molecules in complex biological environments [29]. Future progress in this field will be driven by the integration of advanced computational methods, particularly hybrid QM/machine learning potentials, which promise to deliver both the speed required for high-throughput screening and the accuracy needed to reliably predict molecular interactions [29]. Furthermore, experimental techniques like cryo-EM are providing unprecedented views of biological macromolecules, revealing how their function is dictated by the electronic properties of their constituent atoms [26]. The continued synergy between the foundational principles of electron configuration and cutting-edge computational and experimental technologies will undoubtedly unlock new frontiers in scientific research and innovation.

The principles of chemical periodicity are fundamentally rooted in the electronic structure of atoms. The character of an element, dictating its reactivity, bonding, and physical properties, is predominantly governed by the configuration and energy of its electrons. These electrons are categorized into two distinct classes: core electrons and valence electrons [30] [31]. Core electrons are those occupying the innermost electron shells, tightly bound to the nucleus and forming the atomic core [31]. In contrast, valence electrons reside in the highest occupied principal energy level and are the primary participants in chemical bonding and reactions [30] [32]. This dichotomy is the cornerstone of understanding an element's "chemical personality," as the number and arrangement of valence electrons determine how an atom interacts with others, while core electrons play a crucial, albeit indirect, screening role [33] [31]. Research in electron configuration consistently demonstrates that it is the valence electrons that are involved in the making and breaking of bonds, whereas core electrons remain largely inert chemically [33].

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Core Electrons

Core electrons are defined as electrons that are not valence electrons and are found in complete, inner electron shells [31] [32]. They are tightly bound to the nucleus, with their energies significantly lower than those of valence electrons [31]. The primary chemical role of core electrons is not direct participation in bonding, but rather the screening of the positive charge of the atomic nucleus from the valence electrons [31]. This shielding effect influences the effective nuclear charge experienced by the valence electrons, thereby indirectly modulating an atom's chemical reactivity [33] [34]. For example, in a sulfur atom (Z=16), the 10 electrons in the configurations of the first and second shells (1s²2s²2p⁶) are considered core electrons [35].

Valence Electrons

Valence electrons are the electrons in the highest occupied principal energy level of an atom [30]. For main-group elements, these are the electrons residing in the electronic shell of the highest principal quantum number n [32]. It is these electrons that participate in bond formation, whether by being shared in covalent bonds or transferred in ionic bonds [30] [32]. The number of valence electrons is the primary determinant of an element's chemical properties and its valence [32]. An atom with a closed shell of valence electrons, mimicking a noble gas configuration, tends to be chemically inert. Atoms that are one or two electrons away from a closed shell are highly reactive, as they tend to gain, lose, or share electrons to achieve stability [33] [32].

Orbital Theory and Quantum Mechanical Descriptions

A more nuanced understanding requires atomic orbital theory. In many-electron atoms, the energy of an electron depends on both the principal quantum number (n) and the azimuthal (angular momentum) quantum number (l) [36] [35]. The increase in energy for subshells of increasing angular momentum is due to electron-electron interactions, particularly the ability of low-l electrons (like s-electrons) to penetrate more effectively toward the nucleus, experiencing less screening [31]. For transition metals, the definition of a valence electron expands. It is an electron that resides outside a noble-gas core, which can include electrons in the (n-1)d orbitals that are very close in energy to the ns electrons [32]. For instance, manganese ([Ar] 4s² 3d⁵) effectively has seven valence electrons, consistent with its +7 oxidation state in permanganate (MnO₄⁻) [32].

Diagram 1: Electron classification and influence.

Quantitative Analysis and Periodic Trends

The number of valence electrons for an element can be determined from its position in the periodic table, providing a powerful predictive tool for researchers [32].

Table 1: Valence Electron Count by Periodic Table Group

| Group(s) | Valence Electrons | Element Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (IA) & 11 (IB) | 1 | H, Li, Na, K, Cu |

| 2 (IIA) & 12 (IIB) | 2 | Be, Mg, Ca, Zn |

| 13 (IIIA) | 3 | B, Al, Ga |

| 14 (IVA) | 4 | C, Si, Ge |

| 15 (VA) | 5 | N, P, As |

| 16 (VIA) | 6 | O, S, Se |

| 17 (VIIA) | 7 | F, Cl, Br |

| 18 (VIIIA) | 8 | Ne, Ar, Kr (He has 2) |

For transition metals (Groups 3-12), the situation is more complex. The number of valence electrons can range from 3 to 12 as it includes electrons in the ns and (n-1)d orbitals [31] [32]. For example, scandium ([Ar] 4s² 3d¹) has three valence electrons, while zinc ([Ar] 4s² 3d¹⁰) has two, as its full 3d subshell does not typically participate in bonding [32].

The concept of core charge is quantitatively described by the equation for effective nuclear charge (Zₑₕₕ): Zₑₕₕ = Z - S where Z is the atomic number (number of protons) and S is the shielding constant, approximately the number of core electrons that shield the valence electrons from the nucleus [34]. This core charge is the effective positive charge experienced by an outer-shell electron and is a key parameter in explaining periodic trends [31].

Table 2: Core Charge Calculation for Selected Elements

| Element | Atomic Number (Z) | Core Electrons | Core Charge (Zₑₕₕ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium (Li) | 3 | 2 (1s²) | +1 |

| Carbon (C) | 6 | 2 (1s²) | +4 |

| Sodium (Na) | 11 | 10 ([Ne]) | +1 |

| Chlorine (Cl) | 17 | 10 (1s²2s²2p⁶) | +7 |

These core charge values rationalize several fundamental periodic trends [31] [34] [37]:

- Atomic Radius: Decreases across a period due to increasing core charge pulling the valence electrons closer. Increases down a group due to the addition of electron shells.

- Ionization Energy: The energy required to remove an electron increases across a period as the core charge increases, holding electrons more tightly. It decreases down a group as the outer electrons are farther from the nucleus.

- Electronegativity: The ability to attract bonding electrons increases across a period with increasing core charge and decreases down a group.

Methodologies for Experimental Determination and Analysis

Establishing Electron Configuration

The foundational step in distinguishing core and valence electrons is determining the atom's ground-state electron configuration. This is achieved by applying three key rules to an orbital energy diagram [35]:

- The Aufbau Principle: Electrons are added to the lowest energy orbitals first [18] [35].

- Pauli Exclusion Principle: No two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers; an orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins [35].

- Hund's Rule: For degenerate orbitals, electrons fill each orbital singly before any pairing occurs [35].

Workflow Example: Electron Configuration of Sulfur (Z=16)

- Fill 1s orbital: 1s² (2 electrons, core).

- Fill 2s and 2p orbitals: 2s²2p⁶ (8 electrons, core). The core is now equivalent to [Ne].

- Fill 3s orbital: 3s² (2 electrons, valence).

- Fill 3p orbitals following Hund's Rule: 3p⁴ (4 electrons, valence).

- Result: The full configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁴, or [Ne]3s²3p⁴. This atom has 10 core electrons and 6 valence electrons [35].

Probing Core and Valence Electrons with X-ray Spectroscopy

A key experimental protocol for directly studying core electrons is X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). This technique relies on the photoelectric effect to probe electronic structure [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The solid material to be analyzed is placed in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber to prevent surface contamination.

- Irradiation: The sample is irradiated with a monochromatic beam of X-rays (e.g., Al Kα or Mg Kα).

- Photoemission: Core electrons absorb X-ray photons and are ejected as photoelectrons if the photon energy exceeds their binding energy.

- Energy Analysis: The kinetic energy (KE) of the emitted photoelectrons is measured by a high-resolution electron energy analyzer.

- Data Interpretation: The binding energy (BE) of the core electrons is calculated using the equation: BE = hν - KE, where hν is the known X-ray photon energy. The resulting spectrum shows peaks at characteristic binding energies, identifying the elements present and their chemical states. A core-hole created by the emission decays within 10⁻¹⁵ seconds, either by emitting a characteristic X-ray (X-ray fluorescence) or by ejecting another electron (Auger electron) [31].

Diagram 2: XPS experimental workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions for Electronic Structure Research

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Electronic Structure Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Monochromatic X-ray Source (Al Kα, Mg Kα) | Provides a precise and known energy of irradiation to eject core electrons in techniques like XPS. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) Chamber | Maintains an atomically clean sample surface by eliminating atmospheric contamination during surface-sensitive analyses. |

| Hemispherical Electron Energy Analyzer | Precisely measures the kinetic energy of electrons emitted from a sample, enabling the determination of their original binding energy. |

| Reference Elements (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu) | Used for energy scale calibration of spectrometers to ensure accurate and reproducible binding energy measurements. |

| Computational Chemistry Software | Models atomic and molecular orbitals, calculates electron densities, and predicts properties like ionization energy and electronegativity from first principles. |

Applications in Scientific Research and Drug Development

The principles governing valence and core electrons are not merely academic; they have profound implications in applied research, particularly in drug development and materials science.

Rational Drug Design and Molecular Interactions: The reactivity of organic molecules and pharmaceutical compounds is dictated by the valence electrons of their constituent atoms. Electronegativity, a direct consequence of core charge and atomic radius, determines the polarity of bonds in drug molecules [34]. This polarity influences key interactions such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and dipole-dipole interactions with biological targets like enzymes or receptors [38] [34]. For example, the high electronegativity of oxygen and nitrogen in a drug molecule allows it to form strong hydrogen bonds with a protein's active site, which is critical for binding affinity and specificity [34].

Catalysis and Transition Metal Complexes: In catalysis, many processes rely on transition metals whose d-electrons (valence electrons) can readily change oxidation states and form coordination complexes [33] [32]. The ability to predict the number and behavior of these valence electrons is essential for designing catalysts that facilitate chemical reactions in industrial processes and synthetic chemistry for drug manufacturing [32].

Materials Science and Semiconductor Design: The classification of elements as metals, nonmetals, and metalloids based on their valence electron count guides the design of novel materials [34]. In semiconductor technology, doping silicon (Group 14, 4 valence electrons) with elements from Group 13 (3 valence electrons) or Group 15 (5 valence electrons) creates p-type or n-type semiconductors, respectively, by introducing holes or extra electrons into the valence band [32]. This principle is fundamental to modern electronics and sensor technology.

From Theory to Practice: Writing Configurations and Applying Periodicity in Research

The electron configuration of an element describes the distribution of its electrons within the available atomic orbitals [22]. This distribution is the fundamental determinant of an element's chemical properties and its position in the periodic table [18] [39]. The modern periodic table is structured so that elements with similar electron configurations, and hence similar chemical behaviors, are aligned into the same groups [18] [39]. This periodicity—the repeating patterns in elemental properties—stems directly from the recurring patterns in the valence electron shells [40]. For researchers in drug development, understanding electron configurations enables the prediction of molecular bonding behavior, reactivity, and the interactions between potential pharmaceutical compounds and biological targets. This guide provides a detailed methodology for accurately determining both the complete and abbreviated electron configurations of atoms and ions, a foundational skill in rational molecular design.

Foundational Principles

Writing correct electron configurations relies on three fundamental quantum mechanical rules.

The Aufbau Principle

The Aufbau principle (from the German "Aufbau" for "building up") states that electrons occupy the lowest energy orbitals available first [18] [41]. The order of fill is determined by calculations of orbital energies and follows a specific sequence, which can be remembered using the periodic table or a standard Aufbau diagram [18] [27].

The Pauli Exclusion Principle

The Pauli exclusion principle stipulates that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers [22] [24]. A direct consequence is that an atomic orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, and they must have opposite spins [41].

Hund's Rule

Hund's rule states that when electrons occupy degenerate orbitals (orbitals of the same energy, such as the three p orbitals), they must occupy them singly with parallel spins before any pairing occurs [18] [41]. This "half-fill before you full-fill" approach minimizes electron-electron repulsion and results in the lowest energy configuration [18].

Table 1: Orbital Capacities and Properties

| Orbital Type | Azimuthal Quantum Number (l) | Number of Orbitals | Maximum Electrons |

|---|---|---|---|

| s | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| p | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| d | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| f | 3 | 7 | 14 |

Methodology for Neutral Atoms

Step-by-Step Protocol for Complete Electron Configurations

The following protocol provides a reproducible method for determining the ground-state electron configuration for any neutral atom.

- Identify the Atomic Number (Z): Determine the number of electrons in the neutral atom from its atomic number. For example, iron (Fe) has an atomic number of 26, and thus 26 electrons [18].

- Fill Orbitals in Order of Increasing Energy: Add electrons to the orbitals sequentially, following the established order of fill: 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, ... [18] [27]. Adhere to the maximum capacity for each orbital type as defined in Table 1.

- Apply Hund's Rule: When filling a subshell containing multiple orbitals (p, d, f), place one electron in each orbital with parallel spins before adding a second electron to any orbital [41].

- Write the Configuration: Notate the configuration by listing the occupied subshells in order of fill, with a superscript indicating the number of electrons in that subshell [22].

Table 2: Order of Orbital Filling and Examples

| Element | Atomic Number | Complete Electron Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O) | 8 | 1s² 2s² 2p⁴ [18] |

| Chlorine (Cl) | 17 | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁵ [27] |

| Iron (Fe) | 26 | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² 3d⁶ [18] |

| Iodine (I) | 53 | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² 3d¹⁰ 4p⁶ 5s² 4d¹⁰ 5p⁵ [24] |

Step-by-Step Protocol for Abbreviated Electron Configurations

For elements with high atomic numbers, the complete configuration can be lengthy. The abbreviated notation offers a concise alternative.

- Locate the Element on the Periodic Table: Identify the element and find the noble gas that immediately precedes it in the table [22] [24].

- Write the Noble Gas Symbol in Brackets: This represents the element's core electrons, which have a configuration identical to that noble gas [22].

- Write the Valence Electrons: Continue the electron configuration from the point where the noble gas left off, writing the configuration for the remaining valence electrons [18] [24].

Table 3: Comparison of Complete and Abbreviated Notations

| Element | Complete Configuration | Abbreviated Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphorus (P) | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p³ | [Ne] 3s² 3p³ [22] |

| Titanium (Ti) | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² 3d² | [Ar] 4s² 3d² [22] |

| Iodine (I) | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² 3d¹⁰ 4p⁶ 5s² 4d¹⁰ 5p⁵ | [Kr] 5s² 4d¹⁰ 5p⁵ [24] |

Common Exceptions in the d-Block

Stability is enhanced by half-filled or fully filled d subshells. This leads to notable exceptions in the electron configurations of chromium (Cr) and copper (Cu) and their respective group members [18] [41].

- Chromium (Z=24): Expected: [Ar] 4s² 3d⁴. Actual: [Ar] 4s¹ 3d⁵. The half-filled 3d subshell provides greater stability [41].

- Copper (Z=29): Expected: [Ar] 4s² 3d⁹. Actual: [Ar] 4s¹ 3d¹⁰. The fully filled 3d subshell provides greater stability [41].

Advanced Configurations: Ions

Protocol for Anions

Anions form when atoms gain extra electrons. To write the configuration for an anion:

- Determine the total number of electrons (atomic number plus the magnitude of the negative charge).

- Add the additional electrons to the next available orbitals in the order of fill, following the Aufbau principle and Hund's rule [18].

- Example: The oxide ion (O²⁻) has 10 electrons. Its configuration is 1s² 2s² 2p⁶, which is identical to neon [18].

Protocol for Cations

Cations form when atoms lose electrons. For transition metal (d-block) cations, electrons are removed from the highest principal quantum number shell first, which is often the ns orbital before the (n-1)d orbitals [18].

- Write the electron configuration for the neutral atom.

- Remove the required number of electrons from the highest n value orbitals first [18].

- Example: Iron (Fe) is [Ar] 4s² 3d⁶. The Fe³⁺ ion is formed by removing two 4s electrons and one 3d electron, resulting in [Ar] 3d⁵ [18].

Visualization of Electron Configuration Logic

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for writing electron configurations for atoms and ions, integrating the rules and protocols detailed in this guide.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Electronic Structure Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PyMOL [42] | Molecular Visualization Software | Open-source system for generating publication-quality imagery and animations of molecular structures, including orbital visualization. |

| ChimeraX [42] | Molecular Visualization Software | Next-generation interactive system for analyzing molecular structures and related data, with high-performance graphics and an extensible plugin repository. |