Determining Coordination Complex Stability Constants: Methods, Applications, and Best Practices for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on determining the stability constants of coordination complexes.

Determining Coordination Complex Stability Constants: Methods, Applications, and Best Practices for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on determining the stability constants of coordination complexes. It covers fundamental thermodynamic principles and explores a wide array of classical and modern experimental techniques, including potentiometric, spectrophotometric, and chromatographic methods. The content further addresses critical challenges such as identifying systematic errors and optimizing data processing, with a focus on validating results for reliable application in pharmaceutical development, speciation modeling, and environmental chemistry. Practical insights are drawn from recent computational advances and established laboratory practices to bridge theoretical knowledge with real-world application.

Understanding Stability Constants: Core Concepts and Thermodynamic Principles

In coordination chemistry, stability constants are fundamental equilibrium constants that quantify the formation of complexes in solution, providing a critical measure of the binding strength between metal ions and ligands [1]. These constants are indispensable for researchers and scientists across various fields, from environmental chemistry to pharmaceutical development, as they determine the concentration of free metal ions in solution, influencing everything from plating film quality to drug efficacy and metal separation efficiency [2]. The accurate determination and interpretation of these constants enable professionals to predict complex behavior under varying conditions, design effective metal-chelating agents, and understand biological systems where metal complexes play crucial roles.

The investigation of stability constants has evolved significantly since Jannik Bjerrum developed the first general method for determining metal-ammine complex stability constants in 1941 [1]. Today, research in this field encompasses both traditional experimental approaches and cutting-edge computational methods, including machine learning models that predict stability constants for metal-ligand pairs with increasing accuracy [2]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison between the two primary expressions of complex stability: stepwise and cumulative formation constants, framing this discussion within the broader context of coordination complex stability constant determination research.

Defining Stepwise and Cumulative Stability Constants

Stepwise Stability Constants

Stepwise stability constants (denoted as K₁, K₂, K₃, etc.) represent the equilibrium constants for each individual ligand addition in the sequential formation of a metal complex [1] [3]. These constants describe the formation of complexes one ligand at a time, with each step having its own characteristic equilibrium constant.

For a complex forming through sequential ligand addition, the stepwise reactions and their corresponding constants are:

- First step: ( M + L \rightleftharpoons ML ) with ( K_1 = \frac{[ML]}{[M][L]} )

- Second step: ( ML + L \rightleftharpoons ML2 ) with ( K2 = \frac{[ML_2]}{[ML][L]} )

- n-th step: ( ML{n-1} + L \rightleftharpoons MLn ) with ( Kn = \frac{[MLn]}{[ML_{n-1}][L]} )

A key trend observed in stepwise stability constants is that they generally decrease as the number of ligands increases (( K1 > K2 > K_3 > \ldots )) due to statistical, electrostatic, and steric factors [3]. This progressive decrease reflects the increasing difficulty of adding another ligand to an already coordinated metal ion as available coordination sites diminish and ligand-ligand repulsions increase.

Cumulative Stability Constants

Cumulative stability constants (denoted as β), also called overall stability constants, represent the product of stepwise constants for the complete formation of a complex from the free metal ion and all ligands [1] [3] [4]. These constants provide a measure of the total stability of the fully formed complex.

For the formation of complex ( ML_n ) directly from its components:

- ( M + nL \rightleftharpoons MLn ) with ( \betan = \frac{[ML_n]}{[M][L]^n} )

The relationship between cumulative and stepwise constants is therefore:

- ( \betan = K1 \times K2 \times K3 \times \ldots \times K_n )

For example, if a complex ML₃ has stepwise constants ( K1 = 10^5 ), ( K2 = 10^4 ), and ( K_3 = 10^3 ), the cumulative constant would be ( \beta = 10^5 \times 10^4 \times 10^3 = 10^{12} ) [3]. This mathematical relationship highlights how the overall stability reflects the combined effect of all individual binding events.

Comparative Analysis: Stepwise vs. Cumulative Constants

The table below summarizes the key distinctions between stepwise and cumulative stability constants:

Table 1: Comparison between Stepwise and Cumulative Stability Constants

| Aspect | Stepwise Stability Constants | Cumulative Stability Constants |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Equilibrium constant for each individual ligand addition step | Product of stepwise constants for complete complex formation |

| Mathematical Expression | ( Kn = \frac{[MLn]}{[ML_{n-1}][L]} ) | ( \betan = \frac{[MLn]}{[M][L]^n} = K1 \times K2 \times \ldots \times K_n ) |

| Information Provided | Insights into each binding step; reveals decreasing trend with increasing ligand number | Measures total complex stability from free metal and ligands |

| Typical Notation | K₁, K₂, K₃, ..., Kₙ | β₁, β₂, β₃, ..., βₙ |

| Primary Application | Mechanistic studies of complex formation; understanding intermediate species | Predicting overall complex concentration; comparing total stabilities |

The relationship between these constants can be visualized through the formation pathway of a coordination complex:

Diagram Title: Relationship Between Stepwise and Cumulative Formation Constants

Experimental Determination of Stability Constants

Traditional Potentiometric Methods

The historical foundation of stability constant determination lies in potentiometric methods, particularly using pH measurements to monitor complex formation [1]. Bjerrum's pioneering method recognized that metal complex formation with a ligand represents a competition between the metal ion and hydrogen ions for the ligand. This approach involves titrating a mixture of metal ion and protonated ligand with base while carefully monitoring hydrogen ion concentration using a pH meter.

The fundamental equilibria involved are:

- Acid-base equilibrium: ( H + L \rightleftharpoons HL )

- Complex formation: ( M + L \rightleftharpoons ML )

By knowing the acid dissociation constant of the protonated ligand (HL) and tracking hydrogen ion concentration during titration, researchers can determine stability constants for metal complexes [1]. This method relies on the fact that as base is added, deprotonation occurs, making ligands available for complex formation with metal ions. The mathematical treatment of the titration data allows calculation of both stepwise and cumulative constants.

Modern Computational Approaches

Contemporary research has introduced machine learning approaches to predict stability constants, overcoming limitations of traditional experimental methods [2]. Gaussian process regression (GPR) models have been developed to predict both first overall stability constants (β₁) and higher-order constants (βₙ for n>1) using compositional and topological features of both cations and ligands.

These computational models analyze features including:

- Pauling electronegativity of metals

- Ionic properties (molecular charge, cation charge, ionic radius)

- Ligand structural features (Moreau-Broto autocorrelation of topological structures)

- Fragmental features (number of specific functional groups like -O- and -NH-)

Sensitivity analysis has revealed that electronegativities of both metal and ligand are the most important factors for predicting the first overall stability constant [2]. Interestingly, the predicted value of β₁ shows the highest correlation with higher-order stability constants (βₙ) for corresponding metal-ligand pairs, highlighting the interconnected nature of these constants.

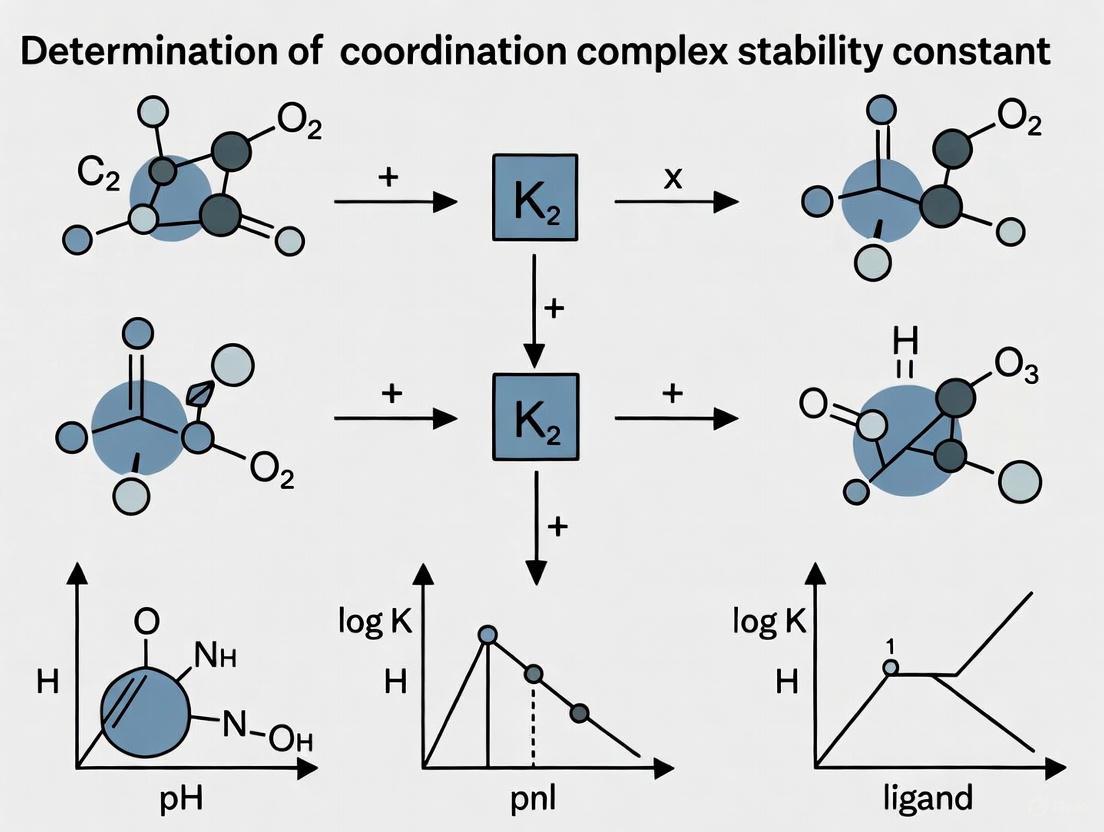

The experimental workflow for stability constant determination combines both traditional and modern approaches:

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Stability Constant Determination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful determination of stability constants requires specific reagents and instrumentation. The following table details essential materials and their functions in stability constant research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Stability Constant Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions for complex formation | Chlorides, nitrates, or perchlorates of transition metals (Cu²⁺, Ni²⁺, Zn²⁺, Co²⁺) |

| Buffers | pH control during potentiometric titrations | Acetate, phosphate, or carbonate buffers appropriate for target pH range |

| Ligands | Molecular entities that coordinate to metal ions | Ammonia, ethylenediamine, EDTA, custom-designed chelating agents |

| Titrants | For quantitative addition during titrations | Standardized NaOH or KOH solutions for acid-base titrations |

| Reference Electrodes | Potential measurement in potentiometry | Calomel or silver/silver chloride reference electrodes |

| pH Electrodes | Hydrogen ion concentration measurement | Glass electrodes with high accuracy in relevant pH range |

| Spectrophotometers | Monitoring color changes in complex formation | UV-Vis instruments for tracking chromogenic complex formation |

| Computational Resources | For machine learning approaches | Gaussian process regression algorithms, molecular descriptor databases |

The selection of appropriate metal ions and ligands is crucial, as stability constants depend significantly on factors such as metal ion charge, ionic radius, ligand denticity, and donor atom electronegativity [5]. For instance, higher positive charges on metal ions generally increase complex stability due to stronger electrostatic attractions, while multi-dentate ligands form more stable complexes than their monodentate counterparts due to the chelate effect [3] [5].

Factors Influencing Stability Constants and Experimental Design

Key Factors Affecting Stability Constants

Multiple factors influence the magnitude of both stepwise and cumulative stability constants, which researchers must consider when designing experiments:

- Charge of the Metal Ion: Higher positive charges on metal ions generally increase complex stability due to stronger electrostatic attractions between the metal ion and ligands [5].

- Nature of the Ligand: Ligands with higher donor atom electronegativity and those capable of forming multiple bonds (chelates) with the metal ion tend to form more stable complexes [5].

- Ionic Radius: Smaller metal ions can approach ligands more closely, leading to stronger bonding interactions and higher stability constants [5].

- Chelate Effect: Polydentate ligands that form ring structures with metal ions create significantly more stable complexes than monodentate ligands, with stability enhancement attributed to both entropic factors and slower dissociation rates [3].

- Solvent Effects: The solvent medium can stabilize or destabilize complexes through solvation of metal ions and ligands, significantly influencing observed stability constants [5].

The Chelate Effect: A Special Case in Stability

The chelate effect represents one of the most important phenomena in complex stability, where multidentate ligands form significantly more stable complexes than monodentate ligands with similar donor atoms [3]. This enhanced stability arises from both thermodynamic (entropic) and kinetic factors:

- Entropic Effect: When a multidentate ligand replaces multiple monodentate ligands, the total number of particles in solution increases, resulting in a positive entropy change that favors complex formation.

- Kinetic Effect: Chelate complexes dissociate more slowly because all donor atoms must dissociate simultaneously for the metal to be released, creating a significant kinetic barrier.

The magnitude of the chelate effect increases with the number of donor atoms in the ligand, with five- and six-membered chelate rings generally exhibiting the greatest stability due to favorable bond angles and reduced ring strain [3]. A classic example demonstrates this effect clearly: for ( [Ni(NH3)6]^{2+} ), log β = 8.61, while for ( [Ni(en)_3]^{2+} ) (en = ethylenediamine, a bidentate ligand), log β = 18.28 [3]. This dramatic increase in stability highlights why chelating ligands like EDTA find such widespread application in industrial and analytical chemistry.

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Industrial Contexts

Stability constants play crucial roles in pharmaceutical development and various industrial processes. In drug design, stability constants determine how effectively potential drug molecules can chelate metal ions in biological systems, influencing both therapeutic activity and toxicity profiles [2] [5]. For instance, the effectiveness of certain chemotherapy drugs relies on their ability to form stable complexes with metal ions in the body, enhancing targeted delivery to cancer cells [5].

In industrial contexts, stability constants significantly impact processes such as:

- Electroless plating, where complex stability affects free metal ion concentration and deposition quality [2]

- Selective separation of elements, particularly in recycling rare earth elements or removing toxic metals [2]

- Analytical chemistry, where complexometric titrations rely on stable complex formation for accurate metal ion quantification [3] [5]

- Environmental remediation, where chelating agents are used to mobilize or immobilize metal contaminants [5]

The continuing development of predictive models for stability constants, including machine learning approaches, promises to accelerate molecular screening and design across these applications by reducing reliance on purely experimental determination [2]. These models enable researchers to prioritize the most promising ligands for specific metals before undertaking synthetic efforts, significantly streamlining the development process.

The distinction between stepwise and cumulative stability constants represents a fundamental concept in coordination chemistry with far-reaching implications for research and industrial applications. Stepwise constants provide detailed mechanistic insights into complex formation processes, while cumulative constants offer a holistic measure of complex stability that directly influences practical applications across chemical, biological, and materials sciences.

Contemporary research continues to refine both experimental and computational approaches to stability constant determination, with machine learning models emerging as powerful tools for predicting these constants based on molecular features [2]. The integration of traditional potentiometric methods with modern computational approaches provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and predicting metal-ligand interactions, supporting advances in drug development, materials science, and environmental chemistry.

As research in this field progresses, the precise determination and application of both stepwise and cumulative stability constants will remain essential for designing novel coordination compounds with tailored properties and specific functions, ultimately driving innovation across multiple scientific and industrial domains.

The determination of stability constants for coordination complexes represents a cornerstone of inorganic chemistry and is critical for advancements in drug development, environmental science, and materials research. These constants quantify the stepwise formation of complexes between metal ions and ligands in solution, providing essential data for predicting molecular behavior under various conditions. The field has evolved dramatically from classical titration-based methods to sophisticated computational workflows, each with distinct advantages and limitations for research applications. This guide objectively compares the historical method pioneered by Bjerrum with contemporary computational approaches, providing experimental data and protocols to assist researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for their specific applications in coordination complex analysis and pharmaceutical development.

Bjerrum's Method: The Classical Approach

Historical Development and Core Principles

Developed by Danish chemist Niels Bjerrum in the early 20th century, the classical method for determining stability constants relies on experimental titration and mathematical analysis of stepwise complex formation. The approach quantitatively describes successive complex formation in systems containing free metal ions, free ligands, and all possible MLi complexes in solution [6]. The fundamental innovation was the Bjerrum function, which relates the average number of ligands bound per metal ion to the free ligand concentration, enabling calculation of individual stability constants for each complexation step [7]. This method established the theoretical foundation for understanding metal-ligand interactions in aqueous solutions and remained the standard approach for decades of coordination chemistry research.

The mathematical core of Bjerrum's method is the Bjerrum polynomial, which is derived from mass balance equations and equilibrium expressions. Critical analysis has proven that this polynomial possesses only one positive root, confirming that a single equilibrium state exists for given initial concentrations of metal and ligand, and specified equilibrium constants [6]. This mathematical certainty provides a solid foundation for the method's reliability, though identifying this root requires careful numerical methods, with Newton's method using the initial ligand concentration as the starting point being the most effective computational approach [6].

Experimental Protocol for Bjerrum's Method

Materials and Equipment:

- pH meter with appropriate electrodes

- Burette for precise titrant delivery

- Thermostatted reaction vessel

- Standardized acid/base solutions

- High-purity metal salt solutions

- Ligand solutions of known concentration

- Inert gas supply for atmosphere control (if needed)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare a solution containing a known concentration of the metal ion of interest.

- Titrate incrementally with a standardized ligand solution while monitoring pH change after each addition.

- Maintain constant ionic strength using appropriate background electrolyte.

- Record pH readings after stabilization at each titration point.

- Conduct control experiments titrating metal solution without ligand and ligand solution without metal.

- Calculate free ligand concentration from pH measurements and known acid dissociation constants.

- Compute the formation function (average number of ligands per metal ion) at each point.

- Solve the Bjerrum polynomial numerically to determine successive stability constants.

Critical Considerations:

- Temperature control is essential as stability constants are temperature-dependent.

- Ionic strength must be maintained constant to ensure meaningful results.

- Measurements should cover a pH range where all complex species form detectably.

- Ligand purity is crucial, as impurities significantly affect calculated constants.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bjerrum's Method

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Solutions | Provides metal ions for complexation | High purity, known concentration, often perchlorate or nitrate salts to minimize anion coordination |

| Ligand Solutions | Binds to metal ions forming complexes | Precisely known concentration, high purity, stable in solution |

| Background Electrolyte | Maintains constant ionic strength | Inert (e.g., NaClO4, KNO3), does not complex with metal ions |

| Standardized Acid/Base | For pH adjustment and calibration | High purity, typically HCl or NaOH solutions |

| Buffer Solutions | pH meter calibration | NIST-traceable standards at multiple pH values |

Modern Computational Workflows

Evolution from Empirical to Computational Methods

While Bjerrum's method established the fundamental principles for stability constant determination, modern approaches have increasingly incorporated computational strategies to enhance accuracy, efficiency, and scope. The transition began with computer-assisted analysis of titration data using nonlinear regression to refine constants, evolving toward purely computational methods that predict stability constants from molecular structure. Contemporary workflows often combine elements of quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR), molecular dynamics simulations, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations to model and predict complexation behavior without extensive laboratory experimentation.

Advanced computational methods now enable researchers to predict stability constants for hypothetical ligands before synthesis, significantly accelerating ligand design for pharmaceutical applications where metal complexation plays a crucial role in drug activity, bioavailability, and toxicity. Modern deep learning approaches have shown particular promise in handling complex, nonlinear relationships in chemical data, as demonstrated by their successful application in financial time series forecasting which shares mathematical similarities with chemical equilibrium modeling [8]. These neural network architectures can identify patterns in large datasets of known stability constants and molecular descriptors to generate accurate predictions for novel compounds.

Computational Protocol for Stability Constant Prediction

Data Requirements and Preparation:

- Crystallographic structures of metal complexes and ligands

- Experimental stability constants for training datasets

- Molecular descriptors (electronic, topological, geometric)

- Solvation parameters and dielectric constants

Algorithm Selection and Training:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute relevant molecular descriptors for metal ions and ligands (charge density, hardness, volume, etc.)

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate algorithm based on dataset size and complexity (multiple linear regression, neural networks, random forests)

- Training: Optimize model parameters using known stability constant data

- Validation: Test predictive accuracy with cross-validation and external test sets

- Application: Predict stability constants for novel metal-ligand combinations

Software and Implementation:

- Chemical database software (CSD, Cambridge Structural Database)

- Molecular modeling packages (Schrödinger, Gaussian)

- Custom scripts for descriptor calculation and model building

- High-performance computing resources for intensive calculations

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Bjerrum vs. Computational Methods

| Parameter | Bjerrum's Method | Modern Computational Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Time Required | 2-5 days per system | Hours to days after model development |

| Accuracy | ±0.1-0.3 log K units | ±0.2-0.5 log K units (model-dependent) |

| Equipment Cost | Moderate ($10K-$50K) | High ($50K-$500K for computational infrastructure) |

| Sample Consumption | Micromolar to millimolar quantities | No physical sample required for predictions |

| Applicability Domain | Experimentally accessible systems | Potentially all elements and ligands |

| Throughput | Low (sequential measurements) | High (parallel predictions) |

| Primary Limitations | Requires measurable signal change, limited to soluble compounds | Training data quality, descriptor relevance, transferability |

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Application

In drug development, metal complexation can significantly impact pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. For example, fluoroquinolone antibiotics exhibit altered bioavailability due to complexation with metal ions like Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Al³⁺. When applying Bjerrum's method to ciprofloxacin-zinc complexes, researchers determined stability constants of log K₁ = 4.82 and log K₂ = 3.75 through precise pH titration, requiring approximately 48 hours of laboratory work. Computational prediction using a previously trained neural network model provided estimates of log K₁ = 4.71 and log K₂ = 3.69 in under 30 minutes, demonstrating the efficiency advantage for rapid screening.

The computational approach enabled high-throughput assessment of complexation tendencies with 15 different metal ions relevant to physiological and formulation conditions in under 8 hours, a task that would require months using traditional methods. However, the experimental precision of Bjerrum's method remained essential for validating critical drug-metal interactions where exact constants were required for regulatory submissions.

Integrated Workflows and Future Directions

Hybrid Experimental-Computational Approaches

The most effective modern strategies combine the precision of Bjerrum's method with the efficiency of computational forecasting. Hybrid workflows use computational methods for rapid screening of potential metal-ligand systems, followed by targeted experimental validation of the most promising candidates using Bjerrum-inspired titration protocols. This approach leverages the respective strengths of both methodologies while mitigating their individual limitations. For pharmaceutical applications, this enables comprehensive assessment of metal complexation potential during early-stage development when material availability is limited and rapid decision-making is crucial.

The continuing development of automated titration systems with real-time data analysis creates opportunities for high-throughput experimental determination that bridges the gap between classical and computational methods. These systems can perform parallel titrations under computer control, collecting the precise experimental data required for Bjerrum analysis with significantly reduced researcher time and sample consumption. Integration with machine learning algorithms for experimental design further optimizes the process by identifying the most informative data points to collect, reducing the number of measurements required for accurate constant determination.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Modern Stability Constant Determination

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal Standards | Provides consistent metal ion sources | Experimental validation, reference data generation |

| Ligand Libraries | Diverse molecular structures for testing | Training dataset development, structure-activity relationships |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Electronic structure calculation | Descriptor calculation, binding energy estimation |

| Cheminformatics Platforms | Molecular descriptor calculation | Feature generation for machine learning models |

| Specialized Buffer Systems | pH control for specific conditions | Physiological relevance, expanded applicability range |

| Reference Complexes | Method validation and calibration | Quality control, cross-laboratory standardization |

The evolution from Bjerrum's classical method to modern computational workflows represents a paradigm shift in stability constant determination, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific research contexts. Bjerrum's method provides unparalleled accuracy and remains the gold standard for validation studies, particularly in pharmaceutical development where precise constants are required for regulatory submissions. Computational workflows offer unprecedented throughput and predictive capability for screening and early-stage development. The most effective contemporary research strategies employ a hybrid approach, leveraging computational methods for rapid screening followed by targeted experimental validation using Bjerrum-inspired protocols. As both computational power and automated laboratory technologies continue to advance, this integration is expected to become increasingly seamless, accelerating research in coordination chemistry and its applications across drug development, materials science, and environmental chemistry.

The stability of coordination complexes, which are compounds formed by the interaction of a metal ion with surrounding ligand molecules, is fundamentally governed by the principles of chemical thermodynamics [9]. In both natural biological systems and engineered pharmaceutical applications, the formation and persistence of these metal-ligand complexes determine their functionality and efficacy [1]. The binding affinity between metal ions and organic ligands is quantitatively expressed through the stability constant (Kstab), an equilibrium constant that describes the formation of a complex in solution [10]. A higher Kstab value signifies a more stable complex that is less likely to dissociate, providing crucial information for predicting complex behavior under various conditions [10].

The overall stability of these complexes is determined by the interplay between enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) contributions to the binding free energy (ΔG), as described by the fundamental Gibbs free energy equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [11]. Within coordination chemistry, researchers and drug development professionals must understand how these thermodynamic components independently contribute to complex stability to design more effective metal-based drugs, environmental chelators, and diagnostic agents [12]. This guide systematically compares the experimental and computational approaches for quantifying these thermodynamic parameters, providing structured data and methodologies to inform research in complex stability constant determination.

Fundamental Thermodynamic Relationships

The formation of a metal complex between a metal ion (M) and a ligand (L) occurs through a substitution reaction where water molecules in the metal's hydration sphere are replaced by ligand molecules [9]. For a general complex formation reaction:

$$pM + qL \leftrightharpoons MpLq$$

The stability constant is defined as:

$$\beta{pq...} = \frac{[MpL_q...]}{[M]^p[L]^q...}$$

This stability constant relates directly to the Gibbs free energy change:

$$ΔG = -RT \ln \beta$$

Where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin. The free energy change comprises both enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) components:

$$ΔG = ΔH - TΔS$$

The enthalpic contribution (ΔH) primarily reflects changes in bond energies during complex formation, including the breaking of metal-water bonds and formation of metal-ligand bonds [1]. The entropic contribution (-TΔS) encompasses changes in the disorder of the system, including the release of ordered water molecules from the hydration spheres of the metal ion and ligand, and changes in rotational, translational, and vibrational freedom [1].

Table 1: Factors Influencing Enthalpic and Entropic Contributions to Complex Stability

| Factor | Impact on Enthalpy (ΔH) | Impact on Entropy (TΔS) | Overall Effect on Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Ion Characteristics | Higher charge density increases bond strength (more negative ΔH) | Smaller ions restrict ligand mobility (negative impact) | Generally increases with charge density |

| Ligand Field Strength | Strong-field ligands form stronger bonds (more negative ΔH) | May restrict metal-ligand bond vibrations | Significant enhancement of stability |

| Chelation Effect | Minimal direct impact | Multiple bonds reduce translational freedom (positive impact) | Substantial stability enhancement |

| Solvation Effects | Desolvation requires energy (positive ΔH) | Released solvent molecules increase disorder (positive ΔS) | Net positive effect when desolvation entropy dominates |

Experimental Determination Methodologies

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Protocol Overview: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) represents the gold standard for directly measuring both enthalpic and entropic contributions to complex stability in a single experiment [13]. The methodology involves the sequential injection of a ligand solution into a sample cell containing the metal ion of interest, while continuously monitoring the heat released or absorbed during each binding event.

Detailed Procedure:

- Prepare purified ligand solution in an appropriate buffer, matching pH and ionic strength with the metal ion solution

- Load metal ion solution into the sample cell (typically 0.2-0.3 mL volume) and ligand solution into the injection syringe

- Set experimental temperature appropriate for the system under study (typically 25°C)

- Program automated injections (usually 10-20 injections of 1-10 μL each) with sufficient time between injections for signal equilibration

- Measure heat flow for each injection after thorough degassing of solutions to prevent bubble formation

- Integrate peak areas to obtain a binding isotherm representing heat change versus molar ratio

- Fit binding isotherm using appropriate binding models to extract ΔH, binding constant (K, related to ΔG), and stoichiometry (n)

- Calculate entropic contribution using the relationship: TΔS = -ΔG + ΔH

Advantages and Limitations: ITC directly measures enthalpy changes without requiring labeling or modification of reactants. It provides complete thermodynamic characterization from a single experiment. However, ITC requires relatively high concentrations of samples (typically μM to mM range) and may struggle with very high affinity binding constants (K > 10^9 M^-1) [13].

Spectroscopic Methods with Van't Hoff Analysis

Protocol Overview: For systems where calorimetric measurements are challenging, temperature-dependent spectroscopic studies coupled with van't Hoff analysis provide an alternative approach for determining thermodynamic parameters.

Detailed Procedure:

- Select an appropriate spectroscopic technique (UV-Vis, fluorescence, NMR) with a signal sensitive to complex formation

- Measure binding at multiple temperatures (typically 5-8 points across a 20-30°C range)

- Determine stability constant (K) at each temperature from titration curves

- Construct van't Hoff plot of lnK versus 1/T

- Fit data to van't Hoff equation: lnK = -ΔH/R(1/T) + ΔS/R

- Extract ΔH from slope (-ΔH/R) and ΔS from intercept (ΔS/R)

Advantages and Limitations: This approach requires less material than ITC and can be applied to very high-affinity systems. However, it assumes that ΔH and ΔS are temperature-independent across the studied range, which may not always be valid, and relies on indirect measurement of thermodynamic parameters [13].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflows for determining thermodynamic parameters of complex stability

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

The selection of appropriate methodology for determining enthalpic and entropic contributions to complex stability depends on multiple factors, including the specific metal-ligand system, available equipment, and required precision.

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Methods for Thermodynamic Parameter Determination

| Method | Measured Parameters | Derived Parameters | Sample Requirements | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Directly measures ΔH and K | TΔS (calculated via ΔG = ΔH - TΔS) | High concentration (μM-mM) | Drug design, protein-ligand interactions, metal chelation studies | Challenging for very high affinity (K > 10^9 M^-1) |

| Spectroscopic Methods + Van't Hoff Analysis | K at multiple temperatures | ΔH and ΔS from temperature dependence | Lower concentration possible | Systems with spectroscopic signatures, high-affinity binding | Assumes constant ΔH and ΔS across temperature range |

| Computational Prediction (Deep Learning) | Molecular structure features | Predicted logK and thermodynamic parameters | Minimal experimental material | High-throughput screening, initial ligand design | Requires large training datasets, model validation needed |

Computational Prediction of Stability Constants

Deep Learning Approaches

Protocol Overview: Recent advances in machine learning have enabled the prediction of stability constants directly from molecular structures, providing a high-throughput alternative to experimental determination [12]. A multi-head graph attention network (GAT) model has demonstrated particular success in predicting metal-ligand stability constants by representing molecular structures as attribute graphs.

Detailed Procedure:

- Data Collection: Extract known metal-ligand stability constants from comprehensive databases (e.g., IUPAC Stability Constants Database)

- Molecular Graph Representation: Represent each organic ligand as a molecular attribute graph with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges

- Feature Extraction: Utilize multi-head graph attention networks to extract molecular features from the attribute graphs

- Feature Integration: Concatenate extracted molecular features with encoded metal ion properties and experimental conditions

- Model Training: Train deep neural network using known stability constant data, typically employing 70-80% of data for training and remainder for validation/testing

- Prediction: Use trained model to predict stability constants for new metal-ligand combinations

Performance Metrics: The graph attention network model has demonstrated impressive predictive capability with determination coefficient (R²) values of 0.956 and root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.251 on test datasets, significantly outperforming traditional quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) approaches and density functional theory (DFT) calculations in both accuracy and computational efficiency [12].

Traditional QSPR Modeling

Protocol Overview: Before the advent of deep learning, quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) modeling served as the primary computational approach for predicting stability constants based on molecular descriptors.

Detailed Procedure:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors (topological, electronic, geometric) for each ligand

- Feature Selection: Identify most relevant descriptors correlated with stability constants

- Model Development: Apply multivariate regression techniques (MLR, PLS) to build predictive models

- Validation: Validate models using external test sets and statistical cross-validation

Advantages and Limitations: QSPR approaches provide interpretable relationships between molecular features and stability but typically offer lower predictive accuracy than deep learning methods and require careful descriptor selection [12].

Diagram 2: Deep learning framework for predicting stability constants using graph attention networks

Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation in Complex Stability

A significant phenomenon observed in thermodynamic studies of complex formation is entropy-enthalpy compensation, where changes in enthalpic contributions to binding are partially or fully offset by opposing changes in entropic contributions [13]. This compensation effect has substantial implications for rational ligand design in pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Characteristics of Compensation

The compensation phenomenon manifests when modifications to a ligand (such as introducing a hydrogen bond donor) result in a favorable enthalpic gain (more negative ΔH) that is counterbalanced by an unfavorable entropic penalty (more negative TΔS), resulting in minimal net change in the overall binding free energy (ΔG) [13]. In severe cases, complete compensation can occur where ΔΔH ≈ TΔΔS and ΔΔG ≈ 0, frustrating optimization efforts in drug design.

Implications for Ligand Engineering

The presence of significant entropy-enthalpy compensation complicates rational ligand design strategies [13]. When severe compensation exists:

- Engineered enthalpic gains (e.g., through additional hydrogen bonds) may be counterbalanced by entropic penalties

- Entropic optimization (e.g., through rigidification) may induce enthalpic penalties

- Focus should remain directly on optimizing binding free energy rather than individual components

However, recent critical analyses suggest that truly severe compensation may be less common than initially thought, with apparent compensation sometimes arising from correlation between experimental errors in measuring ΔH and TΔS [13]. Thus, while compensation should be considered in design strategies, it should not preclude optimization of individual thermodynamic parameters.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Thermodynamic Studies of Complex Stability

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter | High-sensitivity microcalorimeter with automated injection system | Direct measurement of binding enthalpy and stability constants | Protein-ligand interactions, metal chelation studies |

| UV-Visible Spectrophotometer | Temperature-controlled cuvette holder, scanning capability | Monitoring complex formation via absorbance changes | Van't Hoff analysis, binding constant determination |

| NMR Spectrometer | High-field (≥400 MHz) with temperature control | Structural analysis and binding studies via chemical shift changes | Metal coordination environment analysis |

| Database Access | IUPAC Stability Constants Database, Cambridge Structural Database | Source of reference data for validation and modeling | QSPR model development, deep learning training sets |

| Molecular Modeling Software | RDKit, PyTorch, TensorFlow | Molecular graph representation and deep learning implementation | Stability constant prediction, molecular descriptor calculation |

| Buffer Systems | High-purity salts, pH control, degassing equipment | Maintaining constant experimental conditions | All solution-based thermodynamic studies |

The determination and prediction of enthalpic and entropic contributions to complex stability remain active research areas with significant implications for coordination chemistry, pharmaceutical development, and environmental science. Traditional experimental approaches like ITC and van't Hoff analysis provide reliable thermodynamic parameters but require substantial experimental effort. Emerging deep learning methodologies offer promising alternatives for high-throughput prediction, with graph neural networks demonstrating particular efficacy in capturing the complex relationships between molecular structure and stability constants [12].

Future advancements will likely focus on integrating multiple methodological approaches, developing more comprehensive databases of stability constants, and improving the interpretability of computational models. For researchers and drug development professionals, a combined strategy utilizing computational prediction for initial screening followed by experimental validation of promising candidates represents the most efficient pathway for ligand design and optimization. As thermodynamic databases expand and machine learning algorithms become more sophisticated, the accuracy and applicability of these predictive approaches will continue to improve, accelerating the development of novel coordination complexes with tailored stability properties.

The stability of metal complexes is a cornerstone concept in inorganic chemistry with profound implications across scientific disciplines, from the design of novel catalysts to the development of metallodrugs. For researchers and scientists engaged in drug development, predicting and controlling the behavior of metal complexes in vivo is paramount. This stability is quantitatively captured by the stability constant (or formation constant, β), a thermodynamic parameter that measures the propensity of a complex to form from its constituent metal ion and ligands in solution [14]. A higher stability constant signifies a more stable complex [14]. Conversely, the dissociation constant (or instability constant, Ki) is also used, with the relationship β = 1/Ki [15] [14]. It is crucial to distinguish this thermodynamic stability from kinetic stability. A complex like [Co(NH3)6]^3+ may be thermodynamically unstable yet kinetically inert, reacting so slowly that it appears stable, while another like [Hg(CN)4]^2- is thermodynamically stable but kinetically labile, undergoing rapid ligand exchange [14]. This guide delves into the key factors—central metal ion, ligand properties, and chelation effects—that govern this delicate balance, providing a comparative analysis for research and development applications.

Core Factors Influencing Complex Stability

Nature of the Central Metal Ion

The identity of the central metal ion is a primary determinant of complex stability, influencing interactions through its size, charge, and electronic configuration.

- Charge Density: The charge density of a metal ion, defined as the ratio of its ionic charge to its radius, is a critical factor. Higher charge density leads to stronger electrostatic attraction with ligands, resulting in greater stability [15] [16] [17]. This principle explains why, for a given series, stability increases as ionic radius decreases.

- The Irving-Williams Series: For high-spin, octahedral complexes of divalent first-row transition metals, stability constants consistently follow the order: Mn(II) < Fe(II) < Co(II) < Ni(II) < Cu(II) > Zn(II) [17] This trend is attributed to decreasing ionic radius and increasing Crystal Field Stabilization Energy (CFSE) across the series, with the exception of Cu(II), which benefits from additional stability due to the Jahn-Teller effect [17]. Zinc(II), with a full d^10 configuration, has zero CFSE.

- Class A and Class B Metals (Hard-Soft Acid-Base Theory): Metals can be classified based on their preference for different donor atoms [15] [17]:

- Class A (Hard Acids): These include electropositive metals like Al³⁺, Cr³⁺, and Fe³⁺. They form their most stable complexes with hard donor atoms such as N, O, and F [15] [17]. The stability order for halide complexes is F⁻ > Cl⁻ > Br⁻ > I⁻ [17].

- Class B (Soft Acids): These include less electropositive metals like Pd²⁺, Pt²⁺, and Hg²⁺. They form their most stable complexes with soft donor atoms like P, S, and I [15] [17]. The stability order for halide complexes is reversed: I⁻ > Br⁻ > Cl⁻ > F⁻ [17].

Table 1: Metal Ion Properties and Their Impact on Complex Stability

| Property | Description | Impact on Stability | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Charge | Magnitude of positive charge on the metal ion. | Higher charge increases stability [18] [15] [14]. | [Fe(CN)6]^3- is more stable than [Fe(CN)6]^4- [14]. |

| Ionic Size | Radius of the metal ion. | Smaller size increases stability for a given charge [18] [15] [14]. | Cu²⁺ (69 pm) forms more stable complexes than Cd²⁺ (97 pm) [16]. |

| Crystal Field Stabilization Energy (CFSE) | Energy released when d-electrons occupy lower-energy orbitals in a ligand field. | Higher CFSE increases stability [18] [17]. | Ni(II) (high CFSE) complexes are more stable than Zn(II) (zero CFSE) [17]. |

| Metal Classification | Preference for donor atoms (Class A/B). | Dictates which ligand donor atoms yield the most stable complexes [15] [17]. | Class A: Al³⁺ with F⁻. Class B: Hg²⁺ with I⁻ [17]. |

Nature of the Ligand

The structure and properties of the ligand are equally critical in determining the stability of the resulting complex.

- Basicity and Strength: For a series of similar ligands, the basicity (tendency to donate an electron pair) is a good indicator of complex stability. Stronger bases generally form more stable complexes [15] [16] [17]. For example, CN⁻ is more basic than NH₃ and typically forms more stable complexes [16].

- Spectrochemical Series: The ability of a ligand to split the d-orbitals of the metal ion is ranked by the spectrochemical series: I⁻ < Br⁻ < Cl⁻ < F⁻ < OH⁻ < H₂O < NH₃ < en < NO₂⁻ < CN⁻ ≈ CO [18] Strong-field ligands (e.g., CN⁻, CO, en) cause large splitting (Δ), which favors low-spin complexes and results in higher CFSE and greater stability, especially for metals with d⁴ to d⁷ configurations [18].

- Steric Effects: Steric hindrance occurs when bulky groups on a ligand create repulsion with other ligands or the metal ion, weakening the metal-ligand bond and decreasing stability [18] [15] [19]. This is a crucial consideration in catalyst and drug design.

Ligand Property Impact on Stability

Chelation and Macrocyclic Effects

Chelation is one of the most powerful strategies for enhancing complex stability and is widely exploited in medicinal and environmental chemistry.

- The Chelate Effect: This refers to the greater thermodynamic stability of complexes formed with polydentate ligands (chelators) compared to complexes with similar monodentate ligands [20] [21]. For instance, the stability constant for

[Ni(en)₃]²⁺is approximately 10¹⁰ times larger than that for[Ni(NH₃)₆]²⁺[20]. This effect is primarily entropy-driven; replacing multiple monodentate ligands with one multidentate ligand increases the number of molecules in the system, leading to a more favorable entropy change (ΔS) [20] [21]. - Ring Size and Number: The size and number of chelate rings are critical.

- Ring Size: For saturated ligands, 5-membered rings are the most stable, as they have minimal angle strain. Six-membered rings are less stable, and four-membered rings are generally unstable [15] [20]. However, for unsaturated ligands with conjugated double bonds, six-membered rings can be very stable due to resonance [15].

- Number of Rings: Increasing the number of chelate rings per ligand significantly enhances stability. A classic example is the increasing stability constants in the series of Ni(II) complexes with NH₃, en, trien, and a pentadentate ligand [15].

- The Macrocyclic Effect: Macrocyclic ligands (e.g., porphyrins in heme and chlorophyll) form complexes that are even more stable than their chelate counterparts due to their pre-organized structure, which results in a more favorable enthalpy change upon complexation [18] [22].

Table 2: Stability Enhancement through Chelation (Data for Ni(II) Complexes in Aqueous Solution) [15] [20]

| Ligand | Ligand Type | Complex Formed | Approx. log β | Number of Chelate Rings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonia (NH₃) | Monodentate | [Ni(NH₃)₆]²⁺ |

8 | 0 |

| Ethylenediamine (en) | Bidentate | [Ni(en)₃]²⁺ |

18 | 3 |

| Triethylenetetramine (trien) | Tetradentate | [Ni(trien)]²⁺ |

20.2 | 4 |

| Trimethylenediamine (tn) | Bidentate | [Ni(tn)₃]²⁺ |

12 | 3 |

Experimental Determination of Stability Constants

Accurate determination of stability constants is essential for quantifying complex stability. Below are key methodological approaches.

Potentiometric Methods

Potentiometric methods, particularly Bjerrum's method and the Irving-Rossotti method, are classical and widely used techniques [22]. They are based on monitoring the change in pH (and thus proton concentration) as a ligand competes between a metal ion and H⁺.

- Protocol Outline:

- A solution containing the metal ion and the ligand is prepared.

- The solution is titrated with a standard acid or base while the pH is continuously measured.

- The formation function (average number of ligands bound per metal ion,

n) is calculated from the pH data. - From a plot of

nvs. free ligand concentration (p[L]), the successive stability constants (K₁, K₂, ... Kₙ) are determined.

- Applications: Primarily used for ligands that are weak acids or bases, such as polyamines and polycarboxylates [22].

Spectroscopic Methods

These methods rely on changes in a spectroscopic signal (e.g., UV-Vis absorbance, NMR chemical shift) as a function of the metal-to-ligand ratio [22].

- Protocol Outline (Job's Method of Continuous Variation):

- A series of solutions is prepared where the total concentration of metal and ligand is constant, but their mole ratio varies.

- The absorbance (or other property) of each solution is measured at a specific wavelength.

- A plot of absorbance vs. mole fraction of ligand is constructed. The stoichiometry of the complex is indicated by the maximum in the Job's plot.

- Applications: Useful for complexes with distinct spectroscopic signatures and when single species dominate in solution.

Advanced Computational Simulations

Modern in silico approaches provide atomistic-level insights into complex formation and stability that are challenging to obtain experimentally [23].

- Protocol Outline (Molecular Dynamics with Enhanced Sampling):

- Force Field Parameterization: Interatomic potentials are finely tuned, often using 12-6-4 Lennard-Jones type models, to accurately reproduce metal-ligand and metal-solvent interactions [23].

- Enhanced Sampling: Techniques like metadynamics are used to overcome the high energy barriers associated with ligand exchange, allowing for efficient sampling of the formation and dissociation pathways [23].

- Free Energy Calculation: The equilibrium populations of all stable and metastable species (MLₙSₘ) are determined, from which stability constants (K_i) and formation/dissociation rates are directly calculated [23].

- Applications: Ideal for unraveling the thermodynamic, kinetic, and mechanistic contributions to phenomena like the chelate effect, providing a complete picture of the coordination equilibrium [23].

Stability Constant Determination Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Stability Constant Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ethylenediamine (en) & analogs | Bidentate chelating ligand model for studying the chelate effect and ring size impact [15] [20]. | Comparing stability constants of [M(en)n] vs. [M(NH3)6] [20]. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Hexadentate chelator; high stability constant with many metals used as a reference and in titration analyses [21]. | Determining water hardness (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺ concentration) via complexometric titration. |

| Crown Ethers (e.g., 18-crown-6) | Macrocyclic ligands for studying the macrocyclic effect and selective binding of alkali/alkaline earth metals [22]. | Selective complexation and extraction of K⁺ ions. |

| Standard pH Buffers & Electrodes | Essential for accurate pH measurement in potentiometric determination of stability constants [14]. | Used in Bjerrum's method to track proton displacement during complexation. |

| Tuned Force Fields (e.g., 12-6-4 LJ) | Computational models parameterized for realistic simulation of metal-ion interactions in solution [23]. | Molecular dynamics simulations of stepwise complex formation and ligand exchange dynamics. |

| Enhanced Sampling Software (e.g., PLUMED) | Software plugins enabling metadynamics and other advanced sampling for free energy calculations [23]. | Calculating the free energy landscape of metal complex formation and dissociation pathways. |

The stability of coordination complexes is not governed by a single factor but by the intricate interplay between the central metal ion's properties, the ligand's character, and the powerful stabilizing effects of chelation. The charge density and class (A/B) of the metal ion determine its fundamental binding preferences, while the basicity and field strength of the ligand fine-tune the interaction. The chelate and macrocyclic effects provide a dramatic boost in stability, primarily through entropic and pre-organization advantages, respectively. For researchers in drug development, mastering these principles is essential. It allows for the rational design of stable metallodrug carriers, the creation of effective chelation therapies for metal poisoning, and the predictive modeling of metal complex behavior in biological systems. The continued advancement of computational methods, as highlighted, promises to further deepen our atomistic understanding, enabling the in silico design of next-generation coordination compounds with tailored stability and reactivity.

The Critical Role of Speciation in Biological and Environmental Systems

The term "speciation" carries critical importance in two distinct scientific fields: evolutionary biology and environmental chemistry. In biology, speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species, serving as the primary driver of Earth's biodiversity [24]. In chemical and environmental contexts, speciation refers to the specific chemical forms or species in which an element exists, a property that fundamentally governs its behavior, mobility, bioavailability, and toxicity in environmental and biological systems [25]. Understanding both concepts is essential for researchers and professionals tackling challenges from drug development to environmental remediation.

This guide compares the methodological approaches and applications of speciation studies, with a particular focus on its role in coordination complex stability constant determination, a fundamental parameter predicting metal ion behavior.

Analytical Speciation Techniques: A Comparative Guide

Determining the stability constants of coordination complexes is pivotal for predicting metal ion behavior in biological and environmental contexts. The following table compares the core analytical techniques used in such speciation studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Analytical Techniques for Speciation and Stability Constant Determination

| Technique | Core Principle | Typical Application in Speciation | Key Metric Obtained | Reference Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometry | Measures potential change of an ion-selective electrode versus reagent volume. | Determination of stability constants for metal complexes (e.g., Metformin with Cu²⁺, Mn²⁺) in aqueous media. | Stability constants (log β); protonation constants. | Experiments conducted at 27°C ± 0.5°C in 0.1 M NaClO₄ [26]. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | Uses computational models to correlate molecular structure descriptors with biological activity or property. | Predicting stability constants of uranium coordination complexes from molecular composition alone. | Predicted stability constant; model accuracy (R²). | CatBoost regressor model achieving R² = 0.75 on external test set [27]. |

| Coordination Capillary Gas-Liquid Chromatography (GLC) | Measures retention times of analytes on a chiral stationary phase to study complexation. | Determining stability constants of intermediates in chiral Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes with Schiff's bases. | Stability constants of transient intermediates. | Chiral salen complexes dissolved in OV-17 used as stationary phases [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Stability Constant Determination

Detailed Protocol: Potentiometric Determination

The potentiometric titration method is a cornerstone technique for determining stability constants in aqueous solution [26].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the ligand (e.g., 0.001M metformin) and the metal ion of interest. The ionic strength is maintained constant using a supporting electrolyte like 0.1 M NaClO₄.

- System Calibration: Standardize the pH meter (with a glass electrode) using standard buffer solutions to ensure accurate measurement of hydrogen ion concentration.

- Titration Procedure: Titrate the metal-ligand solution with a standard carbonated-free sodium hydroxide solution (e.g., 0.02M) under a nitrogen atmosphere to exclude atmospheric CO₂.

- Data Collection: Record the pH (or emf) after each addition of titrant once equilibrium is established. The temperature must be held constant (e.g., 27°C ± 0.5°C).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the proton-ligand formation constant (pK) and metal-ligand stability constant (log K) from the titration data using computational methods like SCOGS or MINIQUAD.

Detailed Protocol: QSAR Modeling for Prediction

For elements like radionuclides where experimental determination can be challenging, QSAR offers a computational alternative [27].

- Dataset Curation: Compile a dataset of known stability constants for a set of related complexes (e.g., 108 uranium coordination complexes).

- Feature Selection/Generation: Define molecular descriptors for the ligands, which can include physicochemical properties, coordination numbers, molecular charge, and solvation-related features (e.g., number of water molecules).

- Model Training & Validation: Split the dataset into training and test sets. Train a machine learning algorithm (e.g., CatBoost regressor) on the training set and perform hyperparameter optimization.

- Model Evaluation & Application: Validate the model's predictive performance on the external test set. Perform an applicability domain analysis to define the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable. The final model can predict stability constants for novel ligands based on their molecular structure alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in speciation and stability constant studies requires specific, high-purity materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Speciation and Stability Constant Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., NaClO₄) | Maintains a constant ionic strength in solution, which is critical for obtaining accurate and thermodynamically meaningful stability constants in potentiometric titrations [26]. |

| Standard NaOH Solution | Acts as the titrant in acid-base potentiometry. Must be carbonated-free to prevent the formation of metal-carbonate complexes that would interfere with measurements. |

| Ligands of Interest (e.g., Metformin, Schiff's Bases) | The molecules whose complexation with metal ions is under study. Purity and accurate characterization are essential [28] [26]. |

| High-Purity Metal Salts | The source of the metal ion (e.g., CuCl₂, UO₂(NO₃)₂). Purity is paramount to avoid competition from contaminant metals. |

| Inert Atmosphere (N₂ or Ar) | Used to blanket solutions during titration to prevent interference from oxygen (oxidation) and carbon dioxide (carbonate formation) [26]. |

| Thermodynamic Database (e.g., BASSIST) | A curated collection of thermodynamic constants used for modeling and predicting speciation under various conditions [25]. |

| Speciation Modeling Software (e.g., JCHESS, JESS) | Computer programs that calculate the equilibrium distribution of all chemical species in a defined system, using known stability constants [25]. |

Conceptual Workflows and Logical Pathways

The process of determining stability constants and its connection to broader applications can be visualized as a logical workflow. The following diagram illustrates the two primary methodological pathways and their roles in environmental and biological contexts.

Pathways for Determining Metal Complex Stability

Interdisciplinary Connections and Broader Implications

Biological Speciation and Biodiversity

In parallel to chemical speciation, biological speciation is the engine of biodiversity, which is critical for ecological health and human survival. This process generates novel traits and functions through mechanisms like adaptive radiation, as seen in the cichlid fishes of African Great Lakes, where a common ancestor rapidly diversified into hundreds of species with different ecological roles [29]. Understanding these mechanisms provides a model for innovation systems that prioritize territorial uniqueness and co-evolution [29]. Furthermore, the principles of speciation extend back to the origin of life itself, where primitive chemical compartments may have allowed for the diversification of prebiotic molecular systems, creating a form of "origin of species before origin of life" [30].

Environmental and Health Applications

The determination of stability constants through speciation studies has direct and critical applications in environmental science and drug development.

- Environmental Remediation: Speciation studies are "of prime importance" for understanding the behavior of radionuclides and heavy metals in the environment [25]. For instance, predicting the migration and retention of uranium in wastewater or soil requires accurate stability constants for its coordination complexes, guiding the design of effective adsorbents [27].

- Drug Development and Bioactivity: The biological activity of metal-complexing drugs is directly influenced by speciation. The stability of a metal-metformin complex, for example, impacts its efficacy and interaction with biological targets [26]. Research into chiral complexes, like those of Ni(II) and Cu(II) with Schiff's bases, is also relevant for developing asymmetric catalysts used in pharmaceutical synthesis [28].

The synergy between the precise, molecular focus of chemical speciation and the systemic, macro-level focus of biological speciation offers a powerful, interdisciplinary framework for solving complex problems in public health and environmental management.

A Practical Guide to Experimental and Computational Determination Methods

In the field of coordination chemistry, understanding the stability constants of metal complexes is fundamental to research spanning from drug development to materials science. Among the various analytical techniques available, potentiometric titration stands as a classical, robust, and highly versatile method for studying proton-dependent equilibrium systems [31]. This technique measures the potential difference between electrodes to monitor chemical reactions as a function of added titrant, providing critical data for determining stability constants of metal-ligand complexes [31]. For researchers and pharmaceutical professionals working with proton-dependent systems, potentiometric titration offers a thermodynamically rigorous approach to characterizing complexation behavior under various conditions. The technique is particularly valuable for studying metalloproteins and redox-active cofactors that determine thermodynamic driving forces for electron transfer in biological processes [31]. Despite the emergence of modern analytical methods, potentiometric titration remains a cornerstone technique in coordination complex research due to its direct measurement approach, relatively simple instrumentation, and ability to provide precise thermodynamic parameters.

Core Principles and Comparative Advantages

Fundamental Mechanism of Potentiometric Titration

Potentiometric titration is a volumetric analysis method where the endpoint is determined by monitoring the electrical potential between two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a reference electrode—as a titrant is added to the solution [32]. Unlike colorimetric methods that rely on visual indicators, potentiometric titration measures the change in potential resulting from ion concentration variations during the titration process [32]. The reference electrode maintains a constant, known potential, while the indicator electrode responds to the activity of specific ions in the solution [32]. As titrant is added, the potential difference shifts, and these changes are plotted to generate a titration curve where the equivalence point is identified by a sharp inflection point [32]. This approach is particularly effective for proton-dependent systems because it directly measures hydrogen ion activity, making it ideal for studying acid-base equilibria and metal-ligand complexes where proton competition affects stability.

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Techniques

The following table summarizes how potentiometric titration compares with other common methods for stability constant determination:

Table 1: Comparison of Techniques for Stability Constant Determination

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Detection Limits | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometric Titration | Measures potential change between reference and indicator electrodes [32] | Proton-dependent systems; determination of pKa values; metal-ligand complexes [31] | Total sample concentrations below 10⁻⁶ M with optimal systems [33] [34] | Requires significant sample volume; potential electrode drift; overlapping equilibrium constants complicate analysis [31] |

| HPLC | Separation based on chemical partitioning between mobile and stationary phases [35] | Complex mixtures; quality control of pharmaceuticals [35] | Varies with detector and analyte | Requires reference standards; less direct for thermodynamic parameters [35] |

| Spectrophotometric Titration | Monitors changes in light absorption at specific wavelengths | Systems with distinct chromophores; single-component systems | Limited by molar absorptivity | Background interference; requires chromophoric groups [36] |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Measures heat change during binding interactions | Direct determination of thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS) | Limited by magnitude of enthalpy change | Requires significant sample concentration; instrumentation cost |

Potentiometric titration offers distinct advantages for specific research scenarios. It provides superior accuracy for proton-dependent systems because it directly measures hydrogen ion activity rather than inferring it from indirect signals [32]. The technique is particularly valuable for studying complex biological systems like metalloproteins, where it can determine reduction potentials of redox-active cofactors that govern electron transfer processes in respiration and photosynthesis [31]. Additionally, unlike methods that require chromophoric groups or fluorescent labels, potentiometric titration can be applied to colorless solutions and systems without special spectroscopic properties [32].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Potentiometric Titration Protocol for Stability Constants

The following workflow illustrates the generalized experimental process for determining stability constants of coordination complexes:

Diagram 1: Potentiometric Titration Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Solution Preparation: Dissolve a precisely weighed quantity of the metal ion and ligand in an appropriate solvent, typically aqueous medium with controlled ionic strength. For poorly soluble compounds, co-solvents like ethanol may be employed, requiring extrapolation to zero co-solvent concentration [31].

Electrode System Setup: Insert the appropriate electrode pair into the solution. A double-junction reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or calomel) provides stable potential, while the indicator electrode (e.g., glass pH electrode, ion-selective electrode, or platinum electrode) monitors changes in ion activity [32] [37]. For non-aqueous titrations, specialized electrodes with alcoholic electrolytes (e.g., LiCl in ethanol) are required [38].

Titration Process: Titrate the metal-ligand solution with standard acid or base (typically HCl or NaOH) using an automated burette for precise volume delivery. Near the equivalence point, add titrant in smaller increments to better define the inflection point [32].

Data Collection: After each titrant addition, record the equilibrium potential and corresponding volume. Continuous stirring ensures homogeneity, and adequate time between additions allows the system to reach equilibrium [32].

Endpoint Determination: Identify the equivalence point from the titration curve's inflection point, where the potential change per volume unit is maximal [32]. For complex systems with multiple equilibria, several inflection points may be present.

Data Analysis: Calculate stability constants using computational methods that account for all relevant equilibrium processes in the system. Specialized software solves the simultaneous equations derived from mass-balance and charge-balance relationships.

Advanced Approach: EPR-Monitored Potentiometric Titrations for Metalloproteins

For complex systems like metalloproteins containing paramagnetic metal centers, researchers often combine potentiometric titrations with Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy [31]. This hybrid approach provides both thermodynamic and structural information.

Specialized Protocol:

Sample Preparation: Prepare the metalloprotein solution in an appropriate buffer with redox mediators to facilitate equilibrium between the electrode and protein. Common mediators include 1,2-naphthoquinone (Eₘ = +157 mV), duroquinone (Eₘ = +5 mV), and methyl viologen (Eₘ = -440 mV) [31].

Titration Setup: Use a custom electrochemical cell with a platinum working electrode and standard reference electrode (e.g., saturated calomel electrode). Maintain an oxygen-free environment by purging with argon passed through oxygen-scrubbing solutions [31].

Redox Titration: Titrate the protein solution stepwise with a reducing agent (e.g., sodium dithionite) or oxidizing agent while monitoring the potential.

EPR Measurement: At each potential, transfer samples to EPR tubes and freeze in liquid nitrogen for analysis. Quantify the reduced and oxidized forms by measuring characteristic EPR signals [31].

Data Processing: Plot the fraction of reduced species against the solution potential. Fit the data to the Nernst equation to determine the midpoint potential (Eₘ) for each redox center.

Limitations: This method is restricted to EPR-active species under non-catalytic conditions and cannot detect transient paramagnetic intermediates formed during enzyme catalysis. Signal overlap from multiple species may also complicate quantification [31].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of potentiometric titrations requires specific reagents and instrumentation. The following table details the essential components of a potentiometric titration system:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrode | Maintains constant, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl, calomel) [32] | Provides stable reference potential; requires proper filling solution [37] |

| Indicator Electrode | Sensitive to ion of interest (e.g., glass pH electrode, ion-selective electrode, Pt electrode) [32] | Choice depends on reaction type: pH electrode for acid-base, Pt for redox, ion-selective for specific ions [38] |

| Titrant Solutions | Standardized acid/base (HCl, NaOH) or complexing agents (EDTA) of known concentration [32] | Concentration typically 0.01-0.1 M; must be standardized against primary standards [37] |

| Redox Mediators | Small molecules that shuttle electrons between electrode and protein (e.g., quinones, viologens) [31] | Essential for protein titrations; mixture required to cover relevant potential range [31] |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster | Inert salt (e.g., KCl, NaClO₄) at high concentration (0.1-0.5 M) | Maintains constant ionic strength, minimizing activity coefficient variations during titration |

| Primary Standards | Ultra-pure compounds (e.g., potassium hydrogen phthalate, potassium dichromate) for titrant standardization [35] | Ensures accuracy through traceable calibration; critical for quantitative results |

For specialized applications, additional components may be necessary. Non-aqueous titrations require electrodes with non-aqueous electrolytes (e.g., Solvotrode) to prevent junction potential issues [38]. Automated titration systems incorporate motorized burettes, stirrers, and data acquisition interfaces that significantly improve precision and efficiency compared to manual methods [38]. Modern digital electrodes (dTrodes) with integrated memory chips automatically store calibration data and usage history, enhancing traceability for regulated environments like pharmaceutical quality control [38].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Titration Curve Analysis and Equilibrium Calculations

The primary data from a potentiometric titration is a curve of electrode potential (E) or pH versus titrant volume. The equivalence point appears as a sharp inflection where the slope (ΔE/ΔV) reaches its maximum [32]. For stability constant determination, the data before and after the equivalence point are analyzed to extract thermodynamic parameters.

For a simple 1:1 metal-ligand complex (ML), the stability constant β₁ is defined as:

β₁ = [ML]/([M][L])

During titration, the hydrogen ion concentration is measured directly, and the free ligand concentration is determined from mass balance equations. Computer programs like Hyperquad or SPECFIT are typically used to solve the simultaneous equations and refine stability constants through nonlinear regression analysis.

Advanced Data Processing Techniques