Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly of Molecular Cages: From Design Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article comprehensively explores the field of coordination-driven self-assembly for constructing functional molecular cages.

Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly of Molecular Cages: From Design Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

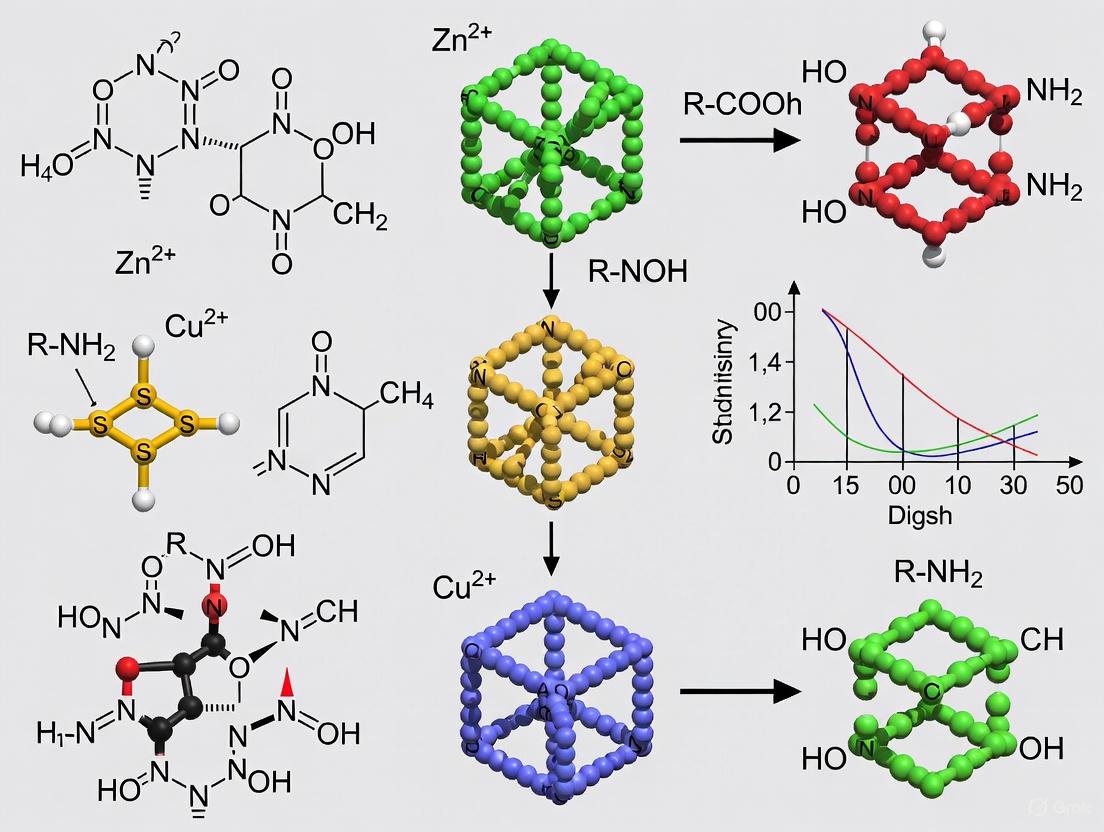

This article comprehensively explores the field of coordination-driven self-assembly for constructing functional molecular cages. It covers the foundational principles of metal-ligand coordination that enable the precise construction of 2D metallacycles and 3D cages with well-defined sizes, shapes, and geometries. The review details advanced synthetic methodologies, including multicomponent and subcomponent self-assembly, and highlights diverse applications in drug delivery, biosensing, catalysis, and photothermal therapy. Critical challenges such as optimizing water solubility, controlling self-organization, and avoiding product inhibition are addressed alongside robust characterization techniques for structural validation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource connects fundamental design concepts to practical implementation, providing a roadmap for developing next-generation smart materials and therapeutic platforms.

The Building Blocks of Nature's Toolkit: Principles and Progression of Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

Metal-ligand coordination bonds form through Lewis acid-base interactions, where metal ions (Lewis acids) accept electron pairs from ligand atoms (Lewis bases) [1]. The energy of these bonds (typically 15–50 kcal mol⁻¹) occupies a crucial middle ground—stronger than non-covalent interactions (0.5–10 kcal mol⁻¹) yet more flexible than covalent bonds (60–120 kcal mol⁻¹) [2]. This intermediate strength embodies the "Goldilocks Principle" in coordination chemistry: bonds must be sufficiently robust to create stable architectures while remaining sufficiently dynamic to allow error correction and responsiveness to external stimuli. This balance makes coordination bonds ideal for constructing complex supramolecular systems, particularly molecular cages, through self-assembly processes [2] [3].

The unique properties of metal ions—including their positive charge, diverse coordination geometries, Lewis acidity, and redox activity—provide a chemical toolkit inaccessible to purely organic systems [4]. Biology extensively exploits these properties, as evidenced by metalloenzymes that catalyze hydrolysis reactions and electron transfer proteins featuring iron-sulfur clusters or cytochromes [4]. Similarly, supramolecular chemists harness these characteristics to create functional metallacycles and cages with applications spanning catalysis, sensing, and biomedicine [2] [3].

The "Goldilocks Principle" in Practice: Bond Strength and Flexibility

Quantitative Aspects of Bond Strength

Table 1: Key Properties of Metal-Ligand Coordination Bonds

| Property | Typical Range | Significance in Self-Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Strength | 15–50 kcal mol⁻¹ [2] | Enables stable structures while allowing reversible assembly |

| Coordination Geometry | Linear, tetrahedral, square planar, octahedral, etc. [1] | Dictates final architecture shape and symmetry |

| Ligand Exchange Kinetics | Varies from labile to inert | Influences error correction capability and stability |

The functionality of coordination complexes stems from more than just bond strength. Several interrelated factors contribute to their utility in supramolecular assembly:

- Charge and Polarity: Metal ions are positively charged, but the overall complex charge can be tuned by ligand selection to create cationic, anionic, or neutral structures [4]. This enables electrostatic interactions with biological molecules or other substrates.

- Coordination Geometry: Metal ions adopt specific geometries (e.g., linear, square planar, tetrahedral, octahedral) dictated by their electronic configuration, providing structural diversity beyond organic chemistry's typical bond angles [4] [1].

- Ligand Exchange Kinetics: The rate at which ligands exchange at the metal center determines whether a complex is "labile" (undergoing fast exchange) or "inert" (experiencing slow exchange) [4]. This kinetic property is critical for self-assembly, which typically requires some reversibility for error correction.

Structural Flexibility and Adaptability

The flexibility of metal-ligand bonds enables remarkable structural adaptability. Recent research demonstrates how ring strain in coordination complexes can be strategically manipulated to control metal-ligand binding affinity [5]. By systematically varying chelate ring size in a series of Pt(II) complexes with phosphino-thioether ligands, researchers found that 5- and 6-membered rings favored thioether binding, while more strained 4-, 7-, and 8-membered rings preferred MeCN coordination [5]. This structural flexibility directly impacts molecular cage stability and stimulus responsiveness.

Advanced techniques provide molecular-level insights into this flexibility. Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) studies of coordination polymers on Cu(111) surfaces revealed how coordination angle flexibility (approximately 180° ± 20°) facilitates chain mobility, scission, and recombination upon heating [6]. This dynamic behavior at the molecular level translates to the macroscopic properties of supramolecular materials.

Diagram 1: The Goldilocks Principle in coordination bonds balances strength and flexibility to enable functional molecular cages.

Application Notes: Coordination Bonds in Molecular Cage Research

Design Principles for Molecular Cages

Molecular cages constructed via coordination-driven self-assembly generally fall into two categories: metal-organic cages (MOCs) and covalent organic cages (COCs) [7]. MOCs typically form through the subcomponent self-assembly approach, which synergistically combines coordination and covalent bond formation between organic subcomponents and metal ions [7]. Successful cage design requires:

- Complementary Building Blocks: Components must possess rigid angles, specific measurements, and symmetric structures to direct assembly toward the desired architecture [2].

- Appropriate Stoichiometry: Precise ratios of metal ions to organic ligands are essential for forming discrete structures rather than polymers [2].

- Reversible Bond Formation: The self-assembly process relies on reversible metal-ligand coordination to allow error correction and high-fidelity structure formation [3].

Table 2: Representative Metallacycle Shapes and Applications

| Metallacycle Shape | Structural Features | Emerging Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Rhomboids [2] | Formed from 60° or 120° donors | Drug delivery, molecular recognition |

| Triangles [2] | Typically use 60° donors | Anticancer agents, catalysis |

| Squares [2] | Employ 90° donors | Biosensing, protein stabilization |

| Hexagons [2] | Utilize 120° donors | Antimicrobial materials, imaging agents |

Functionalization Strategies for Biological Applications

Most metallacycles and cages require water solubility and colloidal stability for biological applications. Two primary strategies address this challenge:

- Covalent Functionalization: Ligands are modified with hydrophilic groups (e.g., polyethylene glycol chains) before assembly to enhance aqueous solubility [2].

- Non-covalent Encapsulation: Metallacycles are wrapped by amphiphilic molecules through hierarchical self-assembly to form stable nanoagents [2].

Recent innovations include developing amide-based bistren-type cages for highly selective nicotine detection in human urine samples with a remarkable detection limit of 0.4 nM [8]. This demonstrates how cage functionalization enables specific molecular recognition in complex biological environments.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Subcomponent Self-Assembly of Molecular Cages

Principle: This one-pot approach simultaneously forms coordinative and covalent bonds between metal ions and organic precursors, enabling complex cage structures to self-assemble spontaneously [7].

Materials:

- Metal salts (e.g., Pt(II), Pd(II), Ru(II), or Cu(II) sources)

- Organic subcomponents (typically aldehyde and amine derivatives)

- Appropriate solvent (often acetonitrile, methanol, or DMSO)

- Acid scavenger (e.g., molecular sieves or non-nucleophilic base)

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solutions of metal salt and organic subcomponents in degassed solvent.

- Combine components in stoichiometric ratios determined by target cage architecture.

- Heat reaction mixture at 60-80°C for 12-48 hours with stirring.

- Monitor reaction progress by NMR spectroscopy or mass spectrometry.

- Purify product by precipitation, crystallization, or size exclusion chromatography.

- Characterize final cage structure using SCXRD, NMR, and HRMS.

Key Considerations:

- Strict control of stoichiometry is critical for high-fidelity assembly.

- Solvent choice affects both reaction kinetics and thermodynamics.

- Mass spectrometry is particularly valuable for monitoring formation processes and analyzing solution behavior [7].

Protocol 2: Manipulating Metal-Ligand Binding Through Ring Strain

Principle: Ring strain modulates metal-ligand binding affinity, providing a method to control allosteric behavior in coordination complexes without elaborate synthetic modifications [5].

Materials:

- Platinum precursor (e.g., (cod)PtCl₂, where cod = 1,5-cyclooctadiene)

- Hemilabile ligands with varying alkyl chain lengths

- Silver salts (e.g., AgBF₄) for chloride abstraction

- Anionic effectors (e.g., tetrabutylammonium chloride)

- Small molecule effectors (e.g., acetonitrile)

Procedure:

- Synthesize hemilabile ligands with 1-5 methylene spacer units.

- Activate Pt precursor via chloride abstraction using AgBF₄.

- React activated Pt complex with hemilabile ligands to form weak-link approach (WLA) complexes.

- Characterize initial complexes by ³¹P NMR spectroscopy and SCXRD.

- Test structural interconversion by adding effectors (Cl⁻ or MeCN).

- Analyze binding preferences and thermodynamics via variable-temperature NMR.

- Perform DFT calculations to understand stability of strained ring systems.

Key Considerations:

- Chelate ring size significantly affects structural stability and effector preference.

- 5- and 6-membered rings typically favor ligand binding, while strained systems prefer small molecule coordination.

- Vacuum treatment can remove weakly-bound effectors to favor closed complexes.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for controlling allosteric behavior through ring strain engineering.

Protocol 3: Analyzing Coordination Polymer Flexibility by STM

Principle: Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) enables direct observation of coordination polymer dynamics at the molecular level, providing insights into structural flexibility and chain mobility [6].

Materials:

- Specially designed ligand (e.g., 2,7-dicyano-9,9-dimethyl-9H-fluorene/DCF)

- Single crystal metal surface (e.g., Cu(111))

- Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) system

- Low-temperature STM with atomic resolution

Procedure:

- Design and synthesize DCF ligand with dimethyl groups to reduce surface interaction.

- Clean and characterize Cu(111) surface under UHV conditions.

- Deposit DCF molecules onto cold surface (7 K).

- Anneal to 323 K to form DCF-Cu coordination polymers.

- Acquire STM images at varying temperatures (4 K to 78 K).

- Track molecular orientation using dimethyl groups as markers.

- Analyze polymer curvature, mobility, and structural transformations.

- Perform DFT calculations to understand coordination angle flexibility.

Key Considerations:

- Ligand design should minimize surface adsorption to enhance mobility.

- Dimethyl groups serve as orientation markers for tracking individual ligands.

- Temperature-dependent studies reveal mobility variations between linear and branched structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Pt(cod)Cl₂, Pd(II) salts, Ru(II) complexes, Cu(acac)₂ | Provide metal centers with specific coordination geometries and electronic properties |

| Hemilabile Ligands | Phosphino-thioethers with variable chain lengths [5] | Enable allosteric control through tunable metal-ligand binding affinity |

| Solvents | Degassed acetonitrile, DMSO, methanol | Mediate self-assembly process while preventing oxidation |

| Effector Molecules | Tetrabutylammonium chloride, acetonitrile [5] | Trigger structural transformations in allosteric systems |

| Surface Substrates | Cu(111) single crystals [6] | Provide platforms for studying coordination polymer dynamics |

| Characterization Tools | SCXRD, ³¹P NMR, HRMS, STM | Enable structural elucidation and dynamic behavior analysis |

The "Goldilocks Principle" of metal-ligand coordination bonds—balancing strength and flexibility—continues to drive innovations in supramolecular chemistry. Current research frontiers include:

- Biological Applications: Molecular cages show increasing promise for drug delivery, biosensing, and anticancer therapy, though challenges remain in ensuring water solubility and stability in physiological environments [2] [3].

- Advanced Materials: Coordination polymers with tailored flexibility enable smart materials that respond to thermal, chemical, or mechanical stimuli [6].

- Sustainable Chemistry: Molecular cages serve as enzyme mimics for catalysis, offering rate acceleration and selectivity through substrate preorganization and transition state stabilization [3].

As characterization techniques advance, particularly in single-molecule spectroscopy and computational modeling, our understanding of metal-ligand interactions will continue to deepen. This knowledge will enable the rational design of increasingly sophisticated functional materials based on the fundamental principles of coordination chemistry.

The field of coordination-driven self-assembly represents a paradigm shift in molecular design, enabling the spontaneous organization of metal ions and organic ligands into discrete, well-defined three-dimensional structures. This approach, pioneered by visionary chemists like Jean-Marie Lehn, Makoto Fujita, and others, leverages the predictable geometry of metal coordination and the directional bonding of organic linkers to create complex molecular architectures from simple building blocks. These metallosupramolecular constructs, particularly coordination cages, have revolutionized nanotechnology, biomimetic chemistry, and drug delivery by providing confined nanospaces that mimic the functions of biological compartments [9]. The development of water-soluble coordination cages (WSCCs) has been especially transformative, opening avenues for biomedical applications where aqueous compatibility is essential. This article traces the historical evolution of this field, from its foundational discoveries to modern applications, while providing detailed experimental protocols for researchers pursuing work in this rapidly advancing area.

Historical Timeline and Key Developments

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Coordination Cage Development

| Year | Key Researcher/Group | Achievement | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Saalfrank et al. | First serendipitous tetrahedral coordination cage [9] | Demonstrated possibility of discrete metal-organic assemblies |

| 1990 | Fujita et al. | Designed molecular square in water [9] [10] | Established rational design principles for aqueous assemblies |

| 1995 | Fujita et al. | First water-soluble 3D molecular cage ([Pd6L4]12+) [9] | Created cage with large enough cavity for guest encapsulation |

| 2000s | Raymond et al. | Symmetry interaction approach for M4L6 cages [10] | Developed design principles for specific cage topologies |

| 2000s | Stang et al. | Directional bonding approach [10] | Established alternative design strategy for coordination assemblies |

| 2020s | Modern Research | Multicomponent, low-symmetry cages [11] | Implemented increased complexity and functionality |

| 2024 | Cui et al. | Dual-controlled guest release system [12] | Achieved sophisticated stimulus-responsive release mechanisms |

The conceptual foundation for coordination cages rests on two primary design strategies: the directional bonding approach and the symmetry interaction approach. The directional bonding method, exemplified by Fujita and Stang, utilizes protected metal centers (particularly cis-protected square planar palladium(II) complexes) with specific angular preferences that direct the assembly of organic ligands into discrete architectures [10]. The symmetry interaction approach, pioneered by Raymond, focuses on matching the symmetry elements of multibranched bidentate ligands with those of octahedral metal ions to predictably form structures like M4L6 tetrahedra [10]. These complementary strategies have enabled the rational design of increasingly complex cage systems.

Diagram 1: Design strategies for coordination cages

Experimental Protocols: Synthesis and Characterization of Water-Soluble Coordination Cages

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Fujita-Type [Pd6L4]12+Octahedral Cage

This protocol adapts the seminal Fujita cage synthesis for modern laboratory settings, based on the 1995 report of a [Pd6(4,4'-bipyridine)4]12+ structure [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Palladium(II) nitrate hydrate (Pd(NO3)2·xH2O)

- Ethylenediamine (en)

- 1,3,5-tris(4-pyridyl)triazine ligand

- Deionized water

- Sodium nitrate (NaNO3)

- D2O for NMR characterization

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Preparation of [(en)Pd(NO3)2] precursor:

- Dissolve 1.0 mmol Pd(NO3)2·xH2O in 10 mL deionized water.

- Add 2.2 mmol ethylenediamine dropwise with stirring.

- Stir for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- A clear solution indicates formation of the [(en)Pd]2+ complex.

Cage self-assembly:

- Dissolve 0.67 mmol 1,3,5-tris(4-pyridyl)triazine in 15 mL deionized water with gentle heating if necessary.

- Slowly add the ligand solution to the [(en)Pd]2+ solution with constant stirring.

- Maintain stoichiometry at 6:4 metal-to-ligand ratio.

- Heat the reaction mixture at 50°C for 2 hours.

Purification and isolation:

- Cool the reaction mixture to room temperature.

- Remove any precipitate by filtration through a 0.45 μm membrane.

- Add saturated NaNO3 solution to precipitate the cage as its nitrate salt.

- Collect the precipitate by filtration and wash with cold water.

- Dry under vacuum overnight.

Characterization:

- NMR Spectroscopy: Dissolve sample in D2O. The 1H NMR spectrum should show simplified, shifted signals compared to free ligand, indicating symmetric environment.

- Mass Spectrometry: ESI-MS should show peaks corresponding to [Pd6L4]12+ with characteristic charge distribution.

- X-ray Crystallography: Slow vapor diffusion of acetone into aqueous cage solution yields crystals suitable for structural determination.

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Corannulene-Based Ag5L2and Hg5L2Cages for Dual-Controlled Release

This protocol describes the synthesis of corannulene-based cages capable of dual-controlled guest release, based on the 2024 report by Cui et al. [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- 1,3,5,7,9-penta(2,2'-bipyridin-5-yl)corannulene ligand

- Silver triflate (AgOTf)

- Mercury triflate (Hg(OTf)2)

- Anhydrous acetonitrile

- Acetone-d6

- Deuterated 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Synthesis of Ag5L2 cage:

- Dissolve 0.1 mmol corannulene-based ligand in 10 mL anhydrous acetonitrile.

- Add 0.25 mmol AgOTf as solid in one portion.

- Stir under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature for 6 hours.

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC and 1H NMR.

- Concentrate under reduced pressure and precipitate with diethyl ether.

- Collect purple solid by filtration and dry under vacuum.

Synthesis of Hg5L2 cage:

- Dissolve 0.1 mmol corannulene-based ligand in 8 mL acetonitrile/chloroform (1:1 v/v).

- Add 0.25 mmol Hg(OTf)2 in 2 mL acetonitrile dropwise.

- Heat at 40°C for 4 hours with stirring.

- Cool to room temperature and concentrate.

- Precipitate with pentane and collect beige solid.

Guest encapsulation:

- Dissolve 10 mg cage in 1 mL acetone-d6.

- Add 2 equivalents of guest molecule (e.g., C60 or organic dye).

- Sonicate for 15 minutes and stir overnight.

- Remove unencapsulated guest by centrifugation/filtration.

Characterization:

- Multinuclear NMR: 1H and 13C NMR in acetone-d6 show characteristic shifted signals confirming cage formation.

- DOSY NMR: Diffusion coefficients confirm discrete molecular assemblies.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Changes in absorption confirm guest encapsulation.

- Mass Spectrometry: High-resolution MS shows peaks corresponding to [Ag5L2]5+ or [Hg5L2]10+ species.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Coordination Cage Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Pd(NO3)2, AgOTf, Hg(OTf)2, Fe(OTf)3, Zn(OTf)2 [9] [12] | Provide structural vertices and symmetry direction | Coordination geometry, lability, oxidation state |

| Organic Ligands | 4,4'-bipyridine, 1,3,5-tris(4-pyridyl)triazine, corannulene-based pentatopic ligands [9] [12] | Form edges/faces of cages; define cavity size/shape | Rigidity, bend angles, solubility, symmetry |

| Solvents | Deionized H2O, CD3CN, CDCl3, acetone-d6 [9] [12] | Medium for self-assembly; influences thermodynamics | Polarity, coordinating ability, deuterated for NMR |

| Guest Molecules | C60, organic dyes, pharmaceutical compounds [9] [12] | Encapsulation studies; functional payloads | Size/complementarity to cavity, hydrophobic effect |

| Characterization Tools | NMR, ESI-MS, X-ray crystallography, UV-Vis [9] [12] | Structural confirmation; host-guest analysis | Sensitivity, resolution, sample requirements |

Advanced Applications and Characterization Techniques

Application Note: Dual-Controlled Guest Release Systems

The corannulene-based cage system demonstrates sophisticated controlled release capabilities requiring two simultaneous stimuli [12]. This dual-control mechanism prevents premature release and enhances targeting specificity.

Experimental Workflow:

- Encapsulation: Prepare Hg5L2 cage in acetone-d6 with guest molecule.

- Stimulus 1 - Metal exchange: Add AgOTf to trigger transmetallation to Ag5L2 while maintaining solvent environment.

- Stimulus 2 - Solvent exchange: Remove acetone and resuspend in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane-d2.

- Release confirmation: Monitor guest release via NMR and UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Key Observations:

- Hg5L2 retains guests in both acetone and tetrachloroethane

- Ag5L2 only retains guests in acetone, releasing in tetrachloroethane

- Both stimuli required for release from initial Hg5L2 system [12]

Diagram 2: Dual-controlled guest release workflow

Characterization Workflow for Coordination Cages

Comprehensive characterization is essential for confirming cage structure, purity, and host-guest interactions.

Table 3: Essential Characterization Methods for Coordination Cages

| Method | Information Obtained | Experimental Details | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Cage symmetry, purity, guest binding | Multinuclear (1H, 13C, 109Ag), DOSY, COSY | Simplified spectra indicate high symmetry; DOSY confirms discrete species |

| Mass Spectrometry | Molecular mass, stoichiometry, charge state | ESI-MS, high-resolution conditions | Characteristic isotope patterns; multiple charge states |

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic-level structure, cavity dimensions | Slow vapor diffusion crystallization | Definitive structural proof; metric parameters |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Guest encapsulation, cage stability | Titration experiments; time-course studies | Spectral shifts indicate host-guest interactions |

| Computational Modeling | Cavity volumes, binding energies, assembly pathways | Molecular dynamics, DFT calculations [10] | Rationalizes selectivity; predicts properties |

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The field of coordination cages continues to evolve toward increasingly complex and functional systems. Current research focuses on several key areas:

Biomedical Applications: Coordination cages show exceptional promise for drug delivery, with their confined spaces protecting therapeutic cargo and enabling targeted release [13]. The dual-controlled release system represents a significant advancement for avoiding premature drug release [12].

Functional Complexity: Recent efforts focus on incorporating multiple functionalities within single assemblies, moving beyond symmetric homoleptic systems to create low-symmetry, multifunctional cages that can perform complex tasks [11].

Computational Design: AI and machine learning are increasingly employed to predict assembly outcomes, guest affinities, and catalytic properties, accelerating the design of functional cages [10] [14]. These computational approaches help researchers navigate the vast chemical space of possible building blocks and predict their assembly behavior before synthetic investment.

Integration with Biological Systems: Future applications will likely involve greater integration of coordination cages with biological systems, potentially leading to artificial enzyme mimics, targeted therapeutic delivery vehicles, and smart materials responsive to physiological stimuli [9] [13].

Coordination-driven self-assembly has emerged as a powerful bottom-up strategy for constructing well-defined supramolecular architectures with precision and functionality. This approach harnesses directional metal-ligand bonding to create complex molecular ensembles from simpler building blocks. The transition from two-dimensional (2D) metallacycles to three-dimensional (3D) polyhedral cages represents a fundamental evolution in structural complexity and functional capability within supramolecular chemistry [15]. These architectures are not merely structural curiosities but serve as versatile platforms for applications ranging from molecular encapsulation to drug delivery [16].

The conceptual foundation for this field draws from Feynman's vision of manipulating matter at the smallest scales, with biological systems serving as inspiration for creating active molecular systems that "do something" rather than simply storing information [15]. The methodology, now termed nanoarchitectonics, establishes a methodology for building functional material systems from nanounits such as atoms, molecules, and nanomaterials [17]. This review examines the architectural diversity of these coordination complexes, their synthetic protocols, and their emerging biomedical applications, with particular emphasis on drug formulation and delivery systems.

Architectural Classification and Structural Fundamentals

From 2D Metallacycles to 3D Cages

The structural landscape of coordination-driven self-assemblies spans from simple 2D metallacycles to complex 3D polyhedral cages. Two-dimensional metallacycles include triangles, squares, rectangles, and hexagons formed through coordination between metal acceptors and organic donors [16]. These structures typically possess a single well-defined two-dimensional cavity [18]. In contrast, three-dimensional polyhedral cages encompass architectures such as prisms, truncated tetrahedra, cuboctahedra, and dodecahedra [15], which contain one or more three-dimensional cavities capable of encapsulating guest molecules [18].

The transition from 2D to 3D structures introduces significant complexity through the implementation of multiple design strategies. The directional bonding approach, pioneered by Stang and others, uses rigid electron-poor metal centers and complementary electron-rich organic donors to create well-defined polygons and polyhedra [15] [19]. The symmetry interaction strategy, advanced by Raymond, constructs highly symmetric coordination clusters using naked metal ions and multibranched chelating ligands [19]. Fujita's molecular paneling method employs face-directed self-assembly to create 3D assemblies with large interior cavities [19]. Mirkin's weak link approach utilizes hemilabile, flexible ligands to form post-self-assembled structures under kinetic control [19], while Cotton's dimetallic building block strategy employs paddlewheel frameworks as structural elements [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Design Strategies in Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

| Approach | Key Innovators | Control Mechanism | Characteristic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directional Bonding | Stang et al. | Thermodynamic | Rigid building blocks, predictable geometries |

| Symmetry Interaction | Raymond et al. | Thermodynamic | High symmetry, multibranched chelators |

| Molecular Paneling | Fujita et al. | Thermodynamic | Face-directed, large cavities |

| Weak Link | Mirkin et al. | Kinetic | Hemilabile ligands, post-assembly modification |

| Dimetallic Building Block | Cotton et al. | Thermodynamic | Paddlewheel frameworks |

Structural Diversity in 3D Cage Architectures

Three-dimensional cages exhibit remarkable architectural diversity, ranging from simple mononuclear cages to complex multi-cavity systems. Discrete M₂L₄ coordination cages represent one of the most well-studied families, formed using square-planar, square-pyramidal, or octahedral coordinated metal ions (Pd, Pt, Co, Cu, Ni, Zn) with bis(monodentate) N-ligands [19]. These structures feature well-defined internal cavities capable of encapsulating anionic, neutral, or cationic guest molecules [19].

More complex conjoined-cage systems represent recent advances in the field. These architectures feature multiple 3D cavities within a single discrete structure. For instance, a family of Pd(II)-based conjoined-cages with formulations [Pd₄(La)₂(Lb)₄], [Pd₅(Lb)₄(Lc)₂], and [Pd₆(Lc)₆] contain two, three, and four cavities, respectively [18]. These multi-cavity systems enable sophisticated functions such as compartmentalization of different guests or processes within a single supramolecular entity [18].

Table 2: Representative Cage Architectures and Their Characteristics

| Cage Type | Structural Formula | Cavity Characteristics | Metal Ions | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M₂L₄ | Two metal centers, four ligands | Single 3D cavity | Pd²⁺, Pt²⁺, Co²⁺, Cu²⁺, Ni²⁺, Zn²⁺ | Molecular encapsulation, catalysis |

| M₃L₆ | Three metal centers, six ligands | Single larger 3D cavity | Pd²⁺ | Larger guest encapsulation |

| Conjoined Cages | [Pd₄(La)₂(Lb)₄], [Pd₅(Lb)₄(Lc)₂], [Pd₆(Lc)₆] | Multiple 3D cavities (2-4) | Pd²⁺ | Multi-compartmental encapsulation |

| Corannulene-based | Hg₅L₂, Ag₅L₂ | Solvent-responsive cavity | Hg²⁺, Ag⁺ | Dual-controlled guest release |

Figure 1: Architectural progression from 2D metallacycles to 3D polyhedral cages with associated functions. The diagram illustrates the synthetic pathways from basic building blocks to complex architectures and their applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Synthesis of M₂L₄ Coordination Cages

The synthesis of M₂L₄ cages typically follows self-assembly protocols under thermodynamic control, where the system reversibly forms the most stable structure [19]. A representative procedure for constructing heterometallic coordination nano-cages is outlined below:

Materials:

- Metal salts: [Cp*RhCl₂]₂, Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O, AgOTf

- Ligands: 1,2,3-triazole-4,5-dicarboxylic acid (LH₃tzdc), various pyridyl donor ligands (L1 to L5)

- Solvents: Methanol, acetonitrile, chloroform

- Equipment: Standard Schlenk line for inert atmosphere, rotary evaporator

Procedure:

- Dissolve the sodium or potassium salt of LH₃tzdc (157 mg, 0.1 mmol) in anhydrous MeOH (10 mL)

- Add [Cp*RhCl₂]₂ (0.05 mmol) to the ligand solution with stirring

- Introduce AgOTf (0.3 mmol) to abstract chloride ions and stir for 12 hours

- Filter the reaction mixture to remove AgCl precipitate

- Add pyridyl donor ligands (L1 to L5, 0.6 mmol) and Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O (0.2 mmol) to the filtrate

- Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 24 hours

- Concentrate the solution under reduced pressure and precipitate using diethyl ether

- Collect the resulting coordination cages (complexes 1-5) by filtration [20]

Characterization: Successful cage formation is confirmed through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), and X-ray crystallography. The cage structures exhibit characteristic symmetry in their NMR spectra, while ESI-MS confirms the molecular formula through isotope pattern matching [20].

Synthesis of Conjoined-Cage Architectures

The construction of multi-cavity conjoined-cages requires careful ligand design and self-assembly conditions. A representative synthesis of [Pd₆(Lc)₆] conjoined-cages is described below:

Materials:

- Metal precursor: Pd(NO₃)₂

- Ligands: Specifically designed "E-shaped" neutral tris-monodentate ligands (L1-L6)

- Solvents: Nitromethane, acetonitrile, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

Procedure:

- Dissolve Pd(NO₃)₂ (0.03 mmol) in nitromethane (3 mL)

- Add the appropriate tris-monodentate ligand (0.04 mmol for [Pd₃L₄] cages) or tetradentate ligand (for higher nuclearity cages)

- Heat the mixture at 60°C for 12 hours with continuous stirring

- Cool the reaction mixture slowly to room temperature

- Allow the product to crystallize by vapor diffusion of diethyl ether into the solution [18]

Key Considerations: The formation of specific conjoined-cage architectures depends on integrative self-sorting processes, where the system selectively assembles into the thermodynamically most stable structure [18]. The backbone structure and denticity of the ligands dictate the final nuclearity and cavity arrangement in the conjoined-cage system.

Drug Loading and Release Studies

Drug Loading Protocol:

- Prepare a suspension of the coordination cage (5 mg) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Add the drug candidate (e.g., Febuxostat) at appropriate concentration

- Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 24 hours with gentle shaking

- Remove unencapsulated drug by dialysis or centrifugation

- Quantify drug loading efficiency using HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy [20]

In Vitro Release Studies:

- Place the drug-loaded cage formulation in a two-chamber diffusion cell

- Use synthetic membrane or excised skin as barrier

- Maintain temperature at 32°C to simulate skin conditions

- Collect aliquots from the receptor compartment at predetermined time intervals

- Analyze drug concentration using validated analytical methods [20]

Transdermal Drug Delivery Assessment:

- Apply drug-loaded cage complexes suspended in water to skin surfaces

- Assess skin penetration using Franz diffusion cells

- Determine the amount of drug permeated per unit area (μg/cm²)

- Evaluate skin irritation through erythema assessment (ΔEI values) [20]

Biomedical Applications and Case Studies

Anticancer Applications

Metal-organic cages have demonstrated significant potential as anticancer agents, with activity against malignant tumors in the lung, cervical, breast, colon, liver, prostate, ovarian, brain, and other tissues [16]. The anticancer mechanisms include inducing membrane damage, cell apoptosis, autophagy, DNA damage, and increased p53 expression [16].

Notable examples include:

- MOC 2: A Ru-Pt metallacycle that accumulates in mitochondria and exhibits near-infrared emission, strong two-photon absorption, and high singlet oxygen generation efficiency. In vivo studies using A549 tumor-bearing nude mice showed tumor reduction to 78% of original size on day 14, with no noticeable body weight loss [16].

- MOCs 5 and 6: Pt(II) triangles containing pyridyl-functionalized BODIPY ligands that combine chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy (PDT). These systems demonstrated excellent synergistic effects against HeLa cells [16].

- MOCs 7-10: BODIPY-containing palladium triangles/squares showing selective cytotoxicity to brain cancer (glioblastoma) cells over normal fibroblasts [16].

Table 3: Biomedical Applications of Selected Metal-Organic Cages

| Cage System | Metal Ions | Application | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOC 2 | Ru, Pt | Photodynamic therapy | Tumor reduction to 78% in 14 days in A549 models | [16] |

| Complexes 1-5 | Rh, Cu | Transdermal drug delivery | Sustained release of Febuxostat over 24 hours | [20] |

| MOCs 5, 6 | Pt | Chemo-PDT combination | Synergistic effects against HeLa cells | [16] |

| Hg₅L₂, Ag₅L₂ | Hg, Ag | Dual-controlled release | Metal- and solvent-dependent guest release | [12] |

| MOCs 7-10 | Pd | Brain cancer targeting | Selective toxicity to glioblastoma cells | [16] |

Controlled Release Systems

Recent advances in cage design have enabled sophisticated controlled release systems. A notable example is the dual-controlled release system based on corannulene-based coordination cages (Hg₅L₂ and Ag₅L₂) [12]. This system requires two simultaneous stimuli—changing metal cations and solvent environment—to trigger guest release, providing enhanced control for complex delivery applications [12].

The release mechanism operates as follows:

- Hg₅L₂ cages maintain guest encapsulation across all studied solvents

- Ag₅L₂ cages encapsulate guests in acetone-d₆ but release them in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane-d₂

- Transmetallation between Hg₅L₂ and Ag₅L₂ enables dual-control release pathways [12]

This dual-controlled system represents a significant advancement over single-stimulus responsive systems, potentially reducing undesired premature release in therapeutic applications.

Biocompatibility and Targeting

Assessment of biocompatibility is essential for biomedical applications. Erythema tests evaluating coordination cage complexes suspended in water demonstrated no significant increase in ΔEI values, indicating high biocompatibility with skin [20]. This property is crucial for transdermal drug delivery applications.

Targeting strategies include:

- Passive targeting: Utilizing the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect for tumor accumulation [16]

- Active targeting: Incorporating biologically specific sequences for targeted drug delivery [16]

- Cellular targeting: Designing cages that localize to specific organelles such as mitochondria [16]

Figure 2: Therapeutic applications and mechanisms of action of coordination cages in drug delivery. The diagram illustrates the relationship between stimulus-responsive systems and their biomedical applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Coordination Cage Synthesis and Study

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | [Cp*RhCl₂]₂, Pd(NO₃)₂, Pt(PEt₃)₂(OTf)₂, AgOTf, Hg(OTf)₂ | Structural nodes, coordination centers | Varying coordination geometries, labile ligands |

| Organic Ligands | Pyridyl-based donors, 1,2,3-triazole-4,5-dicarboxylate, corannulene-based pentadentate ligands | Building blocks, cavity definition | Specific denticity, predetermined angles, functionalizable |

| Solvents | MeOH, CH₃CN, CHCl₃, nitromethane, DMSO | Reaction medium, crystallization | Anhydrous conditions, varying polarity for self-assembly |

| Characterization | NMR solvents (CD₃CN, CDCl₃, acetone-d₆), crystallization agents (diethyl ether) | Structural confirmation, purity assessment | Deuterated for NMR, high purity for accurate analysis |

| Biological Assay | PBS buffer, Franz diffusion cells, synthetic membranes | Application testing, efficacy assessment | Physiological conditions, standardized protocols |

The architectural diversity from 2D metallacycles to 3D polyhedral cages demonstrates the remarkable progress in coordination-driven self-assembly. The field has evolved from creating aesthetically pleasing structures to designing functional systems with sophisticated capabilities in molecular encapsulation, controlled release, and biomedical applications [16] [12].

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas:

- Advanced Controlled Release: Expanding dual- and multi-stimuli responsive systems for precision therapeutic applications [12]

- Multi-Functional Cages: Designing architectures that combine targeting, imaging, and therapeutic capabilities in single platforms [16]

- Biomimetic Systems: Creating cages that mimic biological compartments for complex chemical processes [18]

- Computational Design: Implementing predictive modeling for tailored cage structures with specific functions

As the field progresses, the integration of coordination cages into practical applications—particularly in pharmaceutical formulations and drug delivery systems—will require continued attention to scalability, biocompatibility, and regulatory considerations. The fundamental understanding of self-assembly processes and structure-function relationships will enable the rational design of next-generation supramolecular systems with enhanced capabilities for addressing complex challenges in drug development and beyond.

In coordination-driven self-assembly, structural motifs are specific, recurring geometric arrangements of atoms and bonds that define the architecture of supramolecular structures. These motifs—including rhomboids, triangles, squares, and trigonal prisms—serve as fundamental building blocks (Secondary Building Units, or SBUs) for constructing complex molecular cages and frameworks. The geometry and connectivity of these motifs directly determine critical properties such as cavity size, host-guest interactions, catalytic activity, and magnetic behavior. Control over these motifs is achieved through careful selection of metal centers, organic linker design, and reaction conditions, enabling the rational design of functional materials for applications in drug delivery, sensing, and catalysis.

Defining the Key Motifs

Rhomboid

The rhomboid is a quasi-planar, four-connected motif commonly observed in coordination chemistry, particularly with copper(I) halides and chalcogen-based ligands. It is characterized by a Cu2X2E4 core (where X is a halide and E is a donor atom like S or Se), forming a dinuclear structure with two bridging halides and four ligand donor atoms arranged in a flattened, rhomboidal geometry [21]. This motif is highly adaptable and is often favored by sterically hindered or flexible ligands. Rhomboids are typically non-luminescent or only weakly emissive, making their structural role more significant than their photophysical properties in many applications [21].

Triangle

The triangular motif is foundational for constructing two-dimensional and three-dimensional supramolecular architectures. It is inherently stable due to its geometric efficiency and is a key element in fractal-based assemblies like the Sierpiński triangle [22]. In coordination chemistry, triangles can be homometallic or heterometallic, often serving as faces of larger polyhedra. The self-assembly of triangular units, especially using <tpy-Ru2+-tpy> (tpy = 2,2':6',2''-terpyridine) connectors, allows for the construction of intricate, high-order fractal architectures with self-similarity across multiple scales [22].

Square

The square motif is a common two-dimensional arrangement where four components occupy the corners of a square plane. This motif is prominent in metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and discrete coordination clusters. A notable example is the "square-in-square" topology observed in octanuclear 3d-4f clusters, where a square of four lanthanide ions (e.g., Dy(III)) is inscribed within a larger square of four transition metal ions (e.g., Mn(III), Cr(III), or Fe(III)) [23]. This [M4Ln4] core exemplifies how the square motif can be used to create complex, heterometallic aggregates with potential applications in molecular magnetism.

Trigonal Prism

The trigonal prism is a less common six-coordinate geometry where atoms or ligands are arranged at the vertices of a triangular prism, in contrast to the more prevalent octahedral geometry [24]. This motif is characterized by D3h symmetry and is often stabilized by specific ligand constraints or as part of an extended network structure. It is frequently observed for d0, d1, and d2 transition metal complexes with covalent ligands and small charge separation [24]. An ideal trigonal prismatic geometry has been achieved in a cobalt-based honeycomb MOF, where the triptycene-based ligand enforces this coordination around the Co(II) ion, leading to significant uniaxial magnetic anisotropy [25].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Structural Motifs

| Structural Motif | Coordination Number / Core Geometry | Representative Examples | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhomboid | 4 / Quasi-planar | Cu2I2S4 [21] |

Adaptable packing; often non-luminescent |

| Triangle | Varies / 2D Planar | Sierpiński Triangles (Solution Assembled) [22] | Basis for fractals and high-symmetry polyhedra |

| Square | 4 / 2D Planar | [M4Ln4] "square-in-square" clusters [23] |

Found in MOFs and heterometallic clusters |

| Trigonal Prism | 6 / Prismatic | W(CH3)6, [Co(o-TT)] MOF [24] [25] |

D3h symmetry; strong magnetic anisotropy |

Quantitative Structural Data

A comparative analysis of bond metrics and angles provides a quantitative foundation for understanding the stability and properties of these structural motifs.

Table 2: Quantitative Structural Parameters of Key Motifs

| Motif & Example | Metal-Ligand Bond Length (Å) | Key Bond Angles | Point Group / Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trigonal Planar (e.g., BF₃) [26] | B-F: ~1.30 Å (typical) | F-B-F: 120° | D3h |

Rhomboid (Cu2I2S4) [21] |

Cu-S, Cu-I: Varies with ligand | Cu-X-Cu: ~70-80°; S-Cu-S: ~110-120° | Quasi-D2h |

Trigonal Prism ([Co(o-TT)]) [25] |

Co-O: 2.047 - 2.132 Å | Bailar twist angle (α): ~0.3-0.6° | D3h (near ideal) |

Square (in [M4Ln4] clusters) [23] |

M-O, Ln-O: Varies | M-O-Ln: ~108-120° | C4 (approximate) |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines the synthesis of an octanuclear [Mn4Dy4] cluster, a representative example of a square-in-square motif.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Ligand Solution: 0.1 mmol of t-butyldiethanolamine (

t-bdeaH2) in 10 mL of dry acetonitrile. - Metal Precursors: 0.1 mmol of

Dy(NO3)3·6H2Oand 0.1 mmol of a preformed hexanuclear manganese cluster[Mn6O2(O2CBut)10(4-Me-py)2.5(HO2CBut)1.5]("Mn6"). - Anion Source: 0.5 mmol of sodium azide (

NaN3). - Solvent: Dry acetonitrile and toluene.

- Atmosphere: An inert nitrogen or argon atmosphere is required for all steps.

Procedure:

- Dissolution: Combine the

Dy(NO3)3·6H2O, the "Mn6" cluster, andNaN3in a 100 mL Schlenk flask. - Ligand Addition: Add the ligand solution of

t-bdeaH2in acetonitrile to the reaction mixture. - Reaction: Stir the resulting mixture at room temperature for 4 hours under an inert atmosphere.

- Crystallization: Carefully layer toluene onto the top of the reaction solution. Allow the system to stand undisturbed at room temperature for several days to facilitate slow diffusion and the growth of single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis.

- Isolation: Collect the resulting crystals by filtration, wash with a small amount of cold acetonitrile, and dry under a vacuum.

This protocol describes the synthesis of [Co(o-TT)]·3CH3CN, which exhibits an ideal trigonal prismatic coordination geometry around the cobalt centers.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Ligand: 9,10-[1,2]benzenoanthracene-2,3,6,7,14,15(9H,10H)-hexaone (

o-TT). - Metal Salt:

Co(II)salt (specific salt used in the original study is detailed in the ESI of the reference). - Solvent: Acetonitrile (

CH3CN), high purity.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dissolve the

o-TTligand and theCo(II)salt in acetonitrile within a sealed reaction vessel. - Solvothermal Reaction: Heat the solution at 85°C for 48 hours to promote the self-assembly of the metal-organic framework.

- Crystallization: Cool the reaction vessel slowly to room temperature at a controlled rate of 5°C per hour to enable the formation of high-quality single crystals.

- Isolation: Collect the resulting dark-colored crystals by filtration, wash with fresh acetonitrile, and dry.

This protocol demonstrates how solvent choice can exert kinetic control to selectively form a low-symmetry cage topology.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Aldehyde Solution: Fluorinated aldehyde

Fin methanol. - Amine Solution: (2,4,6-triethylbenzene-1,3,5-triyl)trimethanamine (

Et) in methanol. - Solvents: Dry chloroform and methanol.

Procedure:

- Kinetic Control Setup: Add the amine solution

Etdropwise to a stirred solution of aldehydeFin methanol at room temperature. - Precipitation: Stir the mixture for 3 days. The target

Tri²₂Tri²cage (Et2F2) will precipitate from the solution as a kinetically trapped intermediate. - Isolation (Kinetic): Collect the precipitated solid via filtration.

- Thermodynamic Control Setup: For comparison, stir equimolar amounts of

EtandFin chloroform and heat at 60°C for 3 days. Under these conditions, the system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium, favoring a mixture that includes the highly symmetricTri4Tri4cage. - Stabilization: The dynamic imine cages can be permanently stabilized by reduction with sodium borohydride (

NaBH4) to form the corresponding amine cages.

Diagram 1: Pathway Control in Self-Assembly. The selection of reaction conditions (kinetic vs. thermodynamic control) and building block properties directs the formation of specific structural motifs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful self-assembly relies on a toolkit of well-defined molecular building blocks and metal precursors.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Self-Assembly | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| N-Substituted Diethanolamine Ligands (e.g., t-bdeaH₂) [23] | "Softer" donors for 3d metal ions; alkoxy groups bridge to oxophilic 4f ions. | Assembling heterometallic 3d-4f "square-in-squ are" clusters. |

| Carboxylic Acids (e.g., Pivalic acid, Benzoic acid) [23] | Coligands that saturate the coordination sphere of lanthanide cations and provide charge balance. | Modulating the formation and stability of coordination clusters. |

| Triptycene-based Quinone Ligands (e.g., o-TT) [25] | 3-fold symmetric, rigid bridging ligand with bidentate chelating sites. | Enforcing an ideal trigonal prismatic geometry in 2D honeycomb MOFs. |

Terpyridine-based Metalloligands (e.g., <tpy-Ru²⁺-tpy> modules) [22] |

Shape-persistent, directional linkers for constructing complex architectures. | Synthesis of high-generation fractal assemblies (Sierpiński triangles). |

| Trimethylaluminum (TMAL) & Water [27] | Precursors for forming methylaluminoxane (MAO) activators. | Generating the aluminoxane framework and chemisorbed Lewis acid sites. |

Rhomboids, triangles, squares, and trigonal prisms represent a foundational toolkit for the rational design of molecular cages via coordination-driven self-assembly. The geometry of the final architecture is not predetermined by the building blocks alone but is a function of the interplay between metal ion characteristics, ligand design, and carefully controlled reaction parameters. Mastery of these motifs and the principles governing their formation enables researchers to precisely engineer complex functional materials with tailored properties for advanced applications in catalysis, sensing, and drug development.

Molecular self-assembly is a powerful bottom-up approach for constructing complex supramolecular systems from relatively simple starting materials through reversible noncovalent interactions [28]. Inspired by biological processes, where cells assemble complex molecular structures with remarkable efficiency, synthetic self-assembly strategies significantly reduce synthetic costs while often yielding a single thermodynamic product [28]. The coordination-driven approach to self-assembly represents a particularly robust methodology, utilizing metal-ligand coordination bonds to direct the spontaneous formation of well-defined two-dimensional (2D) polygons and three-dimensional (3D) polyhedra [28].

Central to this process is the concept of molecular information—the structural and electronic properties encoded within molecular subunits that determine recognition selectivity and direct the pathway to specific supramolecular architectures [28]. This application note examines how geometric parameters and symmetry considerations serve as critical information inputs to program self-assembly outcomes, with particular emphasis on coordination-driven cage formation relevant to pharmaceutical and materials sciences.

Theoretical Framework: Geometric Control in Self-Assembly

The Directional Bonding Approach

Coordination-driven self-assembly relies on the directional bonding approach, where rigid molecular subunits with predefined geometry and binding vectors interact to form predictable structures [28]. This approach enables precise control over the geometric factors that determine final supramolecular architecture:

- Acceptor Geometry: Square-planar metal centers (e.g., Pt(II), Pd(II), Ru(II)) impose specific angular relationships between coordinating ligands

- Donor Angularity: Organic donors with specific bond angles (e.g., linear, rectangular, trigonal, tetrahedral) dictate polygon or polyhedron formation

- Binding Vector Orientation: The spatial arrangement of binding sites on both acceptors and donors directs assembly pathways

The combination of these geometric parameters with reversible metal-ligand coordination allows for self-correction during assembly, yielding highly symmetric, thermodynamically stable products [28].

Symmetry Considerations

Symmetry operations govern the formation of closed supramolecular structures. The final architecture reflects the point group symmetry resulting from the combination of molecular components [28]. For instance, combining tetrahedral donors with square planar acceptors typically yields assemblies with high symmetry such as D4h or Td, while lower symmetry components may result in reduced overall symmetry of the supramolecule.

Geometric Programming in Self-Assembly: This workflow illustrates how molecular inputs with defined geometric parameters direct the formation of specific supramolecular architectures through coordination-driven self-assembly.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Self-Assembly of Ru(II)-Metallocycles Based on 4-Amino-1,8-Naphthalimide Scaffold

Purpose: To synthesize [2+2] self-assembled Ru(II)-metallocycles for heparin polyanion sensing applications [29].

Materials:

- Tröger's base derivative (TBNap) supramolecular scaffold

- Half-sandwiched Ru(II) acceptors (M1-M4)

- Anhydrous solvents: acetonitrile, methanol, dichloromethane

- Heparin sodium salt (for binding studies)

Procedure:

- Ligand Preparation: Dissolve TBNap (0.1 mmol) in 10 mL anhydrous acetonitrile with gentle heating (40°C) until fully dissolved [29].

- Metallocycle Formation: Add Ru(II) acceptor (0.1 mmol) dissolved in 5 mL acetonitrile dropwise to the ligand solution with constant stirring [29].

- Reaction Conditions: Heat the mixture at 65°C for 8 hours under nitrogen atmosphere [29].

- Product Isolation: Cool the reaction mixture to room temperature, then concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Precipitation: Add diethyl ether (30 mL) to precipitate the metallocycle product.

- Purification: Collect precipitate by filtration, wash with ether (3 × 10 mL), and dry under vacuum [29].

- Characterization: Confirm structure by ( ^1\text{H} ) and ( ^{13}\text{C} ) NMR, FT-IR, and ESI-MS [29].

Applications: The resulting tetranuclear Ru(II)-metallocycles exhibit strong fluorescence emission that is quantitatively quenched by heparin polyanions, enabling sensing and quantification of heparin concentration with Stern-Volmer quenching constants (K(_\text{SV})) ~10(^5) M(^{-1}) [29].

Protocol 2: Construction of Zn(II) Hexahedral Coordination Cages for Cascade Reactions

Purpose: To design and self-assemble octanuclear Zn(8)L(6) cages with tunable cavity sizes for promoting cascade condensation and cyclization reactions [30].

Materials:

- Tetraphenylethylene (TPE)-derived tetraamine ligands (L1, L2)

- Zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate (Zn(OTf)(_2))

- 2-Formylpyridine

- Solvents: CH(2)Cl(2), CH(_3)CN, THF, 1,4-dioxane

- Anthranilamide and aromatic aldehydes (for catalytic testing)

Procedure:

- Cage Assembly: Combine Zn(OTf)(2) (0.08 mmol), TPE ligand (L1 or L2, 0.06 mmol), and 2-formylpyridine (0.24 mmol) in 15 mL mixed solvent (CH(2)Cl(2):CH(3)CN, 2:1 v/v) [30].

- Heating Step: Heat the mixture at 70°C for 12 hours in a sealed vessel [30].

- Crystallization: Obtain single crystals by slow diffusion of Et(2)O/THF or 1,4-dioxane/THF (1:1 v/v) into saturated CH(3)CN cage solution [30].

- Characterization:

- Analyze by ( ^1\text{H} ) and ( ^{13}\text{C} ) NMR to confirm discrete, symmetric assembly [30]

- Perform diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) to determine hydrodynamic radius [30]

- Conduct Q-TOF-MS to verify multicomponent assembly [30]

- Characterize by single-crystal X-ray diffraction for structural elucidation [30]

Catalytic Application: The TPE-based cages catalyze cascade condensation and cyclization of anthranilamide and aromatic aldehydes to produce nonplanar 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones with remarkable rate enhancements (k(\text{cat})/k(\text{uncat}) up to 38,000) and multiple turnovers [30].

Quantitative Data Analysis

Structural Parameters of Coordination Cages

Table 1: Geometric Parameters of Representative Coordination Cages

| Cage System | Framework Formula | Cavity Volume (ų) | Window Dimensions (Ų) | Metal-Metal Distances (Å) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPE-1 [30] | [(Zn(8)L(6))(OTf)(_{16})] | 522.3 | 3.7 × 7.8 | 10.27-11.47 | Cascade catalysis |

| TPE-2 [30] | [(Zn(8)L(6))(OTf)(_{16})] | 2222.4 | 13.7 × 6.4 | 14.59-18.34 | Cascade catalysis |

| Ru(II)-metallocycles [29] | Tetranuclear [2+2] | N/R | N/R | N/R | Heparin sensing |

N/R: Not reported in the cited literature

Self-Organization Efficiency in Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

Table 2: Control Factors Governing Self-Organization Efficiency

| Control Factor | Effect on Self-Organization | Example System | Degree of Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dipolar interactions [28] | Promotes specific orientation of asymmetric ligands | Unsymmetrical bidentate ligands with Pt(II) acceptors | Absolute |

| Steric interactions [28] | Subtly tuned through small structural variations | Multiple complementary Pt(II) acceptors and pyridyl donors | Amplified to Absolute |

| Geometric parameters [28] | Size, angularity, and dimensionality differences direct specific assembly | 2D polygons and 3D polyhedra from Pt(II) acceptors | Statistical to Absolute |

| Solvent and temperature [28] | Modifies thermodynamic preferences | Complex mixtures of multiple subunits | Variable |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Self-Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Acceptors | Pt(II), Pd(II), Ru(II), Zn(II) complexes [28] [29] [30] | Provide structural vertices with defined geometry; coordinate with donors |

| Organic Donors | Pyridyl-based donors, tetraphenylethylene derivatives, naphthalimide scaffolds [29] [30] | Serve as bridging ligands with specific angular relationships |

| Structural Directants | Tröger's base, tetraphenylethylene, asymmetric bidentate ligands [28] [29] [30] | Impart steric and electronic information to control assembly outcome |

| Assembly Solvents | Acetonitrile, dichloromethane, dimethylformamide [29] [30] | Medium for reversible bond formation and error correction |

Advanced Applications in Drug Development

The precise geometric control achievable through coordination-driven self-assembly enables sophisticated applications in pharmaceutical sciences:

Molecular Recognition and Sensing: Ru(II)-metallocycles constructed from 4-amino-1,8-naphthalimide Tröger's base scaffolds function as effective heparin sensors, demonstrating strong fluorescence emission that is quantitatively quenched upon heparin binding with high sensitivity (K(_\text{SV}) ~10(^5) M(^{-1})) [29]. This application leverages the defined cavity size and shape complementary to the heparin polyanion.

Enzyme-Mimetic Catalysis: Zn(II) hexahedral cages with tunable cavities promote cascade condensation and cyclization reactions with remarkable efficiency [30]. The confined environment of the cage orients reactants for optimal interaction, mimicking enzyme active sites while achieving substantial rate enhancements (k(\text{cat})/k(\text{uncat}) up to 38,000) and multiple catalytic turnovers [30].

Drug Delivery Systems: The ability to construct cages with specific cavity volumes and window dimensions enables encapsulation and controlled release of therapeutic agents. The geometric parameters directly influence guest binding affinity and release kinetics, providing a foundation for targeted drug delivery platforms.

Pharmaceutical Applications of Coordination Cages: This diagram illustrates how specific cage properties enable various pharmaceutical applications, from molecular sensing to drug delivery.

Geometric parameters and symmetry considerations constitute fundamental molecular information that directly dictates outcomes in coordination-driven self-assembly. Through careful design of metal acceptor geometry and organic donor angularity, researchers can program the formation of specific 2D and 3D architectures with precision. The experimental protocols and quantitative data presented herein provide a framework for exploiting these principles in constructing functional supramolecular systems with applications in sensing, catalysis, and drug development.

The integration of geometric control with functional group incorporation enables the creation of sophisticated supramolecular devices that bridge the gap between synthetic systems and biological complexity. As understanding of molecular information encoding deepens, further advances in tailored supramolecular synthesis for pharmaceutical applications will continue to emerge.

Blueprints and Real-World Impact: Synthetic Strategies and Functional Applications

The field of supramolecular chemistry has witnessed significant advances through the development of self-assembly methodologies for constructing complex molecular architectures. Among these, coordination-driven self-assembly (CDSA) and subcomponent self-assembly represent two powerful strategies for building discrete supramolecular structures, particularly molecular cages. These approaches enable the spontaneous formation of well-defined two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) architectures from relatively simple building blocks under mild conditions, often with high efficiency and selectivity [7] [28].

These self-assembled systems have gained prominence in molecular cage research due to their structural precision, functional versatility, and potential applications in catalysis, drug delivery, sensing, and biomimetic chemistry [31]. The ability to design cages with specific geometries, cavity sizes, and functional properties has opened new avenues for controlling molecular recognition and reactivity in confined spaces. This article provides a detailed comparison of these core methodologies, including quantitative comparisons, standardized protocols, and practical implementation guidelines for researchers in supramolecular chemistry and drug development.

Conceptual Frameworks and Key Distinctions

Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly (CDSA)

CDSA relies on the directional coordination between metal acceptors and organic donors to form discrete supramolecular architectures. This approach typically uses pre-formed, complementary molecular components with specific binding angles and coordination geometries [28] [32]. The metal centers (often Pt(II), Pd(II), or Zn(II)) serve as structural vertices that direct the overall geometry of the assembly through their coordination preferences, while organic ligands with specific angularity act as spacers or edges [32] [30]. The resulting structures include 2D metallacycles and 3D metallacages whose geometries are predetermined by the angles between coordination sites on both metal and ligand components [30].

Subcomponent Self-Assembly

Subcomponent self-assembly represents a more convergent approach where complex structures form through the synergistic formation of both coordination and covalent bonds from simpler starting materials [7]. In this methodology, organic subcomponents (typically amines and aldehydes) first undergo dynamic covalent bond formation (imine condensation) to form ligands, which then coordinate to metal ions in situ [7]. This one-pot process generates complex architectures through a network of simultaneous reactions that are reversible and can therefore self-correct, often leading to a single thermodynamic product [7].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiating Factors

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between CDSA and Subcomponent Self-Assembly

| Parameter | Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly | Subcomponent Self-Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Formation | Primarily coordination bonds | Synergistic coordination and covalent bonds |

| Assembly Process | Step-wise: pre-formed components | Convergent: in situ formation of ligands |

| Key Building Blocks | Metal acceptors + organic donors | Metal ions + amines + aldehydes |

| Structural Control | Directional bonding + component geometry | Metal coordination geometry + covalent bond formation |

| Reversibility | Coordination bonds (reversible) | Coordination + covalent bonds (both reversible) |

| Common Metal Centers | Pt(II), Pd(II), Zn(II) | Various transition metals and lanthanides |

Quantitative Comparison of Methodological Features

The practical implementation of these methodologies reveals significant differences in structural features, functional properties, and application potential. The following table summarizes key quantitative and qualitative parameters relevant to molecular cage design.

Table 2: Structural and Functional Properties of Representative Self-Assembled Cages

| Property | Coordination-Driven Assemblies | Subcomponent Assemblies |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Nuclearity | Dinuclear to octanuclear [32] [30] | Varies from simple to high nuclearity |

| Cavity Volume Range | 522.3 ų to 2222.4 ų [30] | Tunable based on subcomponent size |

| Common Architectures | Rhomboids, rectangles, hexagons, cubes [32] [30] | Helicates, grids, cages, complex polyhedra |

| Stimuli-Responsiveness | Incorporation of photochromic units (e.g., diarylethene) [32] | pH, chemical, or redox triggers common |

| Characterization Challenges | Dynamic coordination bonds, crystallization difficulties [33] | Complex reaction monitoring required [7] |

| Catalytic Applications | Confined space catalysis (e.g., cascade reactions) [30] | Biomimetic catalysis, artificial enzymes [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly of a Pt-Based Rhomboid

This protocol details the synthesis of a rhomboidal structure through CDSA, adapted from published procedures [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CDSA Rhomboid Formation

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Pt-based precursor 1 | 60° bite angle between square planar Pt(II) acceptors | Metal acceptor with structural control |

| Pyridine-based precursor 2 | 1,3-bis(pyridin-4-ylethynyl)benzene, 120° donor angle | Organic donor with specific angularity |

| Acetone | HPLC-grade | Solvent system |

| Nitrate salts | Counterion source | Charge balance in coordination complex |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the Pt-based precursor 1 (10 μmol) and pyridine-based precursor 2 (10 μmol) separately in 1 mL of HPLC-grade acetone.

- Mixing: Combine the two solutions in a 5 mL vial with stirring at room temperature.

- Reaction Monitoring: Allow the reaction to proceed for 2 hours with continuous stirring.

- Characterization: Analyze the reaction mixture by ion mobility-mass spectrometry (IM-MS) and NMR spectroscopy to confirm rhomboid formation.

Critical Notes

- The 60° bite angle of the Pt acceptor and 120° donor angle of the pyridine-based precursor are essential for rhomboid formation [33].

- Optimized IM-MS instrument parameters are crucial for accurate characterization: reduce source and extraction cone voltages to minimize collision-induced dissociation [33].

- The expected product is a rhomboidal supramolecular complex with overall charge 4+ (m/z 689) from loss of four nitrate anions [33].

Protocol 2: Subcomponent Self-Assembly of a Zn₈L₆ Coordination Cage

This protocol describes the synthesis of a hexahedral coordination cage via subcomponent self-assembly, based on published work [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Subcomponent Cage Assembly

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc triflate (Zn(OTf)₂) | High purity (>99%) | Metal ion source for vertices |

| Tetraphenylethylene-based tetraamine ligand (L1/L2) | Tetrakis-bidentate ligand with extended aromatic panels | Structural face for cage assembly |

| 2-Formylpyridine | >98% purity | Subcomponent for imine formation |

| Solvent system | CH₂Cl₂:CH₃CN (2:1 v/v) | Reaction medium |

| Crystallization solvents | Et₂O, THF, 1,4-dioxane | Crystal growth by vapor diffusion |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Reaction Setup: Combine Zn(OTf)₂ (0.08 mmol), tetraphenylethylene-based tetraamine ligand (L1 or L2, 0.06 mmol), and 2-formylpyridine (0.48 mmol) in a mixture of CH₂Cl₂ and CH₃CN (10 mL total volume, 2:1 ratio).

- Heating: Heat the reaction mixture at 70°C for 24 hours with stirring.

- Product Isolation: Cool the reaction to room temperature and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Recrystallize via vapor diffusion by layering a saturated CH₃CN solution of the crude product with Et₂O/THF or 1,4-dioxane/THF (1:1 v/v).

- Characterization: Analyze by ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, Q-TOF-MS, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction (if suitable crystals form).

Critical Notes

- The reaction proceeds through simultaneous imine formation and metal coordination [30].

- Crystal formation may require optimization of solvent combinations and diffusion rates.

- Yields typically range from 35-64% depending on the specific ligand and crystallization efficiency [30].

- The resulting cage has a general formula [(Zn₈L₆)(OTf)₁₆]·G (where G = guest molecule) with a cavity volume of 522.3 ų for TPE-1 and 2222.4 ų for TPE-2 [30].

Analytical and Characterization Strategies

Advanced Mass Spectrometry Techniques

Mass spectrometry, particularly ion mobility-mass spectrometry (IM-MS), has emerged as a powerful tool for characterizing self-assembled systems [33]. IM-MS provides a direct measure of the size and shape of CDSA complexes, overcoming limitations of NMR and X-ray crystallography for dynamic systems [33].

Key Considerations for IM-MS Analysis:

- Instrument Tuning: Proper tuning parameters are critical to observe intact, solution-phase ion structures. This includes reducing source potentials (source and extraction cones) and trap bias potentials to minimize collisional activation [33].

- Fragmentation Patterns: CID of intact ions can reveal topology, as loss of mass and charge often occurs in factors related to the symmetry of the assembly [33].

- Adduct Formation: Counterion adduction (e.g., nitrate) can stabilize self-assembly products in the gas phase, observed as different charge states [33].

Supplementary Characterization Methods

- Multinuclear NMR (¹H, ¹³C, ³¹P) to confirm symmetry and purity [32] [30]

- Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy (DOSY) for hydrodynamic radius determination [30]

- X-ray Crystallography for definitive structural assignment when suitable crystals form [30]

- Theoretical Calculations (DFT) to understand stability and conformational preferences [32]

Method Selection Guide

The choice between CDSA and subcomponent self-assembly depends on research goals, desired structural features, and functional requirements. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate methodology.

Coordination-driven and subcomponent self-assembly represent complementary methodologies for constructing functional molecular cages. CDSA offers precise geometric control through pre-designed components and is particularly suited for incorporating stimuli-responsive units and creating well-defined confined spaces for catalysis [32] [30]. Subcomponent self-assembly provides a more convergent route to complex architectures through synergistic bond formation and is especially valuable for creating biomimetic systems and artificial enzymes [7] [31].

The continued advancement of these methodologies, coupled with improved characterization techniques like IM-MS, promises to expand the structural diversity and functional scope of self-assembled molecular cages. Future directions will likely focus on increasing complexity through self-organization phenomena, enhancing catalytic efficiency in confined spaces, and developing integrated systems for biomedical applications including drug delivery and theranostics [28] [31].

The coordination-driven self-assembly of molecular cages represents a powerful frontier in supramolecular chemistry, enabling the construction of complex, well-defined three-dimensional structures from molecular building blocks [34]. This process leverages the predictable coordination geometries of metal ions and the directed connectivity of organic ligands to spontaneously form discrete architectures. Among the various metal ions studied, Pd(II), Pt(II), Ru(II), and Zn(II) have emerged as particularly versatile and widely used platforms for constructing these sophisticated systems [34] [7]. These metal nodes provide a combination of well-defined coordination geometry, kinetic stability, and diverse reactivity that makes them indispensable for creating functional supramolecular assemblies, including metal-organic cages (MOCs) and metallacages [7] [35]. The resulting structures are not merely of academic interest; they find direct utility in catalysis, molecular encapsulation, sensing, and biomedicine, often mimicking the complex functions of biological systems through a synthetic, bottom-up approach [31] [34] [35]. This application note details the design principles, synthetic protocols, and key functional applications of supramolecular coordination complexes based on these four foundational metal ion platforms, providing a practical guide for researchers in the field.

Fundamental Design Principles and Metal Node Characteristics

The rational design of coordination-driven assemblies hinges on a deep understanding of the inherent properties of the metal ion nodes. The geometry, lability, and electronic character of the metal center dictate the final architecture's shape, stability, and function. The subcomponent self-assembly approach, which relies on the synergistic formation of coordination and covalent bonds between organic subcomponents and metal ions, is a particularly effective methodology for constructing these complex architectures [7]. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the four metal platforms central to this note.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Pd(II), Pt(II), Ru(II), and Zn(II) Metal Nodes in Self-Assembly

| Metal Ion | Preferred Coordination Geometry | Key Ligand Partners | Kinetic Profile | Primary Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd(II) | Square planar | Pyridyl, N-heterocyclic carbenes | Moderately labile | High structural predictability, robust self-assembly, excellent for cages and polygons [34] |

| Pt(II) | Square planar | Pyridyl, Phosphines | Slow, inert | High thermodynamic and kinetic stability, stable in biological media [34] |

| Ru(II) | Octahedral | 2,2'-Bipyridine, Terpyridine | Inert | Photoactive properties, useful in light-harvesting and photocatalysis [34] |

| Zn(II) | Tetrahedral, Octahedral | Pyridyl, Carboxylate, Imidazole | Labile | Biocompatibility, catalytic activity (e.g., Lewis acid), common in enzyme mimics [31] |