Coordination Environment Analysis in Drug Development: Techniques, Applications, and Regulatory Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of coordination environment analysis techniques for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Coordination Environment Analysis in Drug Development: Techniques, Applications, and Regulatory Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of coordination environment analysis techniques for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of systems-level coordination, from molecular drug-target interactions to the regulatory frameworks governing AI and complex data. The content details advanced methodological applications, including electroanalysis and network modeling, for practical use in discovery and development. It further addresses troubleshooting and optimization strategies for analytical and regulatory challenges and concludes with validation frameworks and a comparative analysis of global regulatory landscapes. This guide synthesizes technical and regulatory knowledge essential for innovating within the modern, data-driven pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Understanding Coordination Environments: From Molecular Networks to System-Level Regulation

In pharmaceutical science, coordination describes specific, structured interactions between a central molecule and surrounding entities, dictating the behavior and efficacy of therapeutic agents. This concept extends from the atomic level, where metal ions form coordination complexes with organic ligands, to macroscopic biological networks involving drug-receptor interactions and cellular signaling pathways. The coordination environment—the specific arrangement and identity of atoms, ions, or molecules directly interacting with a central entity—is a critical determinant of a drug's physicochemical properties, biological activity, and metabolic fate [1] [2]. Understanding and manipulating these environments allows researchers to enhance drug solubility, modulate therapeutic activity, reduce toxicity, and overcome biological barriers, making coordination a fundamental principle in modern drug design and development [3] [4].

The study of coordination in pharmaceuticals bridges traditional inorganic chemistry with contemporary molecular biology. Historically, the field was dominated by metal-based drugs like cisplatin, a platinum coordination complex that cross-links DNA to exert its anticancer effects [2]. Today, the scope has expanded to include organic coordination systems such as deep eutectic solvents (DES) for solubility enhancement and sophisticated computational models that predict how drugs coordinate with biological targets [3] [5]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these diverse coordination systems, detailing their underlying mechanisms, experimental characterization techniques, and applications in the pharmaceutical industry, framed within the broader context of coordination environment analysis research.

Comparative Analysis of Coordination-Based Pharmaceutical Systems

The table below objectively compares three primary coordination systems used in pharmaceutical research and development, summarizing their core coordination chemistry, key performance parameters, and primary applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Coordination-Based Pharmaceutical Systems

| System Type | Core Coordination Chemistry | Key Performance Parameters | Reported Efficacy/Data | Primary Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Drug Complexes [1] [2] [4] | Coordinate Covalent Bonding: Central metal ion (e.g., Pt, Cu, Au, Zn) bound to electron-donating atoms in organic ligand pharmaceuticals. | - Cytotoxic Activity (IC50)- DNA Binding Affinity- Thermodynamic Stability Constant | - Cisplatin: Potent cytotoxicity against head/neck tumors [2].- [Au(TPP)]Cl complex: Significant in-vitro/in-vivo anti-cancer activity [2].- Cu(PZA)₂Cl₂: 1:2 (Metal:Ligand) coordination confirmed [1]. | |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [3] | Hydrogen Bonding: A hydrogen bond donor (HBD) and acceptor (HBA) form a mixture with a melting point lower than its individual components. | - Solubility Enhancement- Dissolution Kinetics- Thermodynamic Model Fit (e.g., UNIQUAC) | - TBPB:DEG DES increased solubility of Ibuprofen & Empagliflozin [3].- Dissolution was endothermic, increasing with temperature/DES concentration [3].- UNIQUAC model provided the most accurate correlation [3]. | |

| AI-Modeled Drug-Target Interactions [5] [6] | Non-covalent & Covalent Docking: Computational prediction of binding poses and energies via hydrogen bonding, van der Waals, electrostatic, and hydrophobic interactions. | - Binding Free Energy (ΔG, kcal/mol)- Predictive Accuracy vs. Experimental Data- Virtual Screening Enrichment | - Schrödinger's GlideScore: Maximizes separation of strong vs. weak binders [5].- DeepMirror AI: Speeds up drug discovery by up to 6x, reduces ADMET liabilities [5].- AI facilitates de novo molecular design [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Coordination Systems

Protocol 1: Solubility Enhancement with Deep Eutectic Solvents

This protocol outlines the experimental methodology for determining the solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs in aqueous Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) systems, as derived from recent research [3].

- Objective: To measure the apparent equilibrium solubility and dissolution kinetics of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in DES-water mixtures and to correlate the data with thermodynamic models.

- Materials:

- API Model Compounds: Ibuprofen (IBU) and Empagliflozin (EMPA).

- DES Synthesis: Tetrabutylphosphonium bromide (TBPB) as hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and diethylene glycol (DEG) as hydrogen bond donor (HBD), combined at a specific molar ratio.

- Solvent: Deionized water for preparing aqueous DES mixtures.

- Methodology:

- DES Synthesis & Characterization: Synthesize the DES by mixing TBPB and DEG under specific conditions. Confirm the formation of the eutectic mixture using techniques like Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to observe hydrogen bond formation.

- Preparation of Aqueous DES Systems: Prepare eleven different mass fractions of the synthesized DES in water to create a range of solvent environments with varying polarities.

- Solubility Measurement: Add an excess amount of the API (IBU or EMPA) to each DES-water mixture. Equilibrate the suspensions in an incubator shaker at controlled temperatures (e.g., 20°C, 30°C, 40°C) for 24 hours to ensure equilibrium is reached.

- Sampling & Analysis: After equilibration, separate the supernatant from undissolved solids by filtration. Analyze the concentration of the dissolved API in the supernatant using a validated analytical method, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection.

- Dissolution Kinetics: Monitor the dissolution profile over time (up to 24 hours) to differentiate between true equilibrium solubility and metastable supersaturated states.

- Data Correlation: Fit the experimental solubility data to thermodynamic models (Wilson, NRTL, UNIQUAC) using regression analysis to determine the model parameters and assess which model provides the best correlation.

- Key Findings: The study found that solubility for both drugs increased with rising temperature and DES concentration, indicating an endothermic dissolution process. Ibuprofen generally achieved higher dissolution than empagliflozin in the TBPB:DEG DES-water system. Among the models, UNIQUAC provided the most accurate correlation with the experimental data [3].

Protocol 2: Synthesis and Characterization of a Metal-Drug Complex

This protocol details the synthesis and physicochemical characterization of a coordination complex between a metal ion and a pharmaceutical ligand, using a Pyrazinamide (PZA)-Copper complex as an example [1].

- Objective: To synthesize a metal-drug coordination complex and characterize its structure, composition, and morphology.

- Materials:

- Pharmaceutical Ligand: Pyrazinamide (PZA).

- Metal Salt: Copper(II) chloride dihydrate (CuCl₂·2H₂O).

- Solvents: Suitable solvents for synthesis and purification (e.g., water, ethanol).

- Methodology:

- Synthesis: Dissolve the PZA ligand in a warm solvent. Slowly add an aqueous solution of the copper salt under constant stirring. Maintain the reaction mixture at a specific temperature and pH to facilitate complex formation. The resulting solid complex is isolated by filtration, washed thoroughly, and dried.

- Elemental Analysis (EA): Determine the elemental composition (C, H, N, S, metal content) of the complex. This data is used to confirm the Metal:Ligand (Me:L) ratio, which was found to be 1:2 for [Cu(PZA)₂]Cl₂ [1].

- Spectroscopic Characterization:

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Analyze the ligand and the complex. A shift in the vibrational frequencies of key functional groups (e.g., -C=O stretch, ring nitrogen vibrations) upon complexation indicates coordination through those atoms [1].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Use MS to confirm the molecular weight of the complex and identify fragments, which helps verify the proposed structure [1].

- Morphological Analysis:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Image the complex to analyze its particle size, shape, and surface topography. The [Cu(PZA)₂]Cl₂ complex showed acicular (needle-like) particles with an average size of about 1.5 microns [1].

- Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS): Coupled with SEM, EDS is used to detect and map the elemental composition (e.g., Cu, Cl) within the synthesized complex, confirming the presence of the metal in the sample [1].

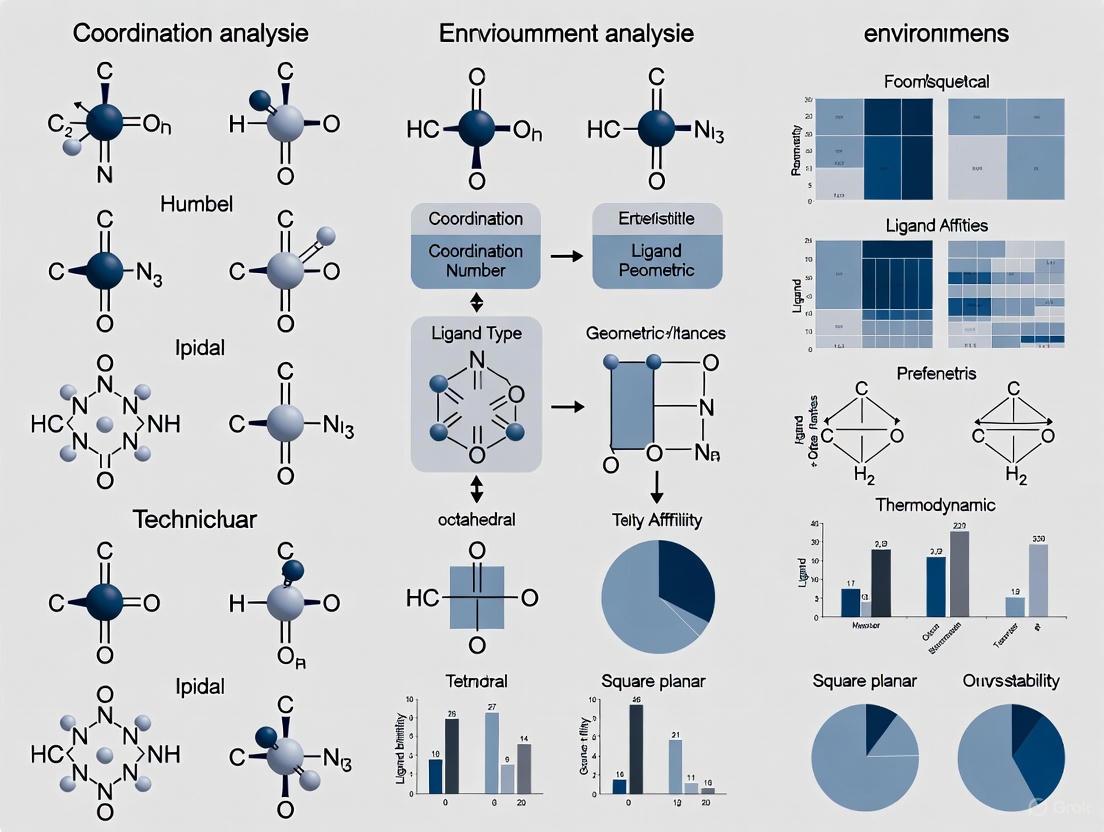

Diagram 1: Metal-Drug Complex Characterization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Successful research into pharmaceutical coordination environments relies on a suite of specialized reagents, software, and analytical instruments. The following table details the essential components of the modern scientist's toolkit in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Coordination Environment Analysis

| Tool Name/ Category | Function in Coordination Analysis | Specific Role in Pharmaceutical Development |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [3] | Serves as a tunable solvent medium whose components can coordinate with APIs. | Enhances the solubility and dissolution of poorly water-soluble drugs (e.g., Ibuprofen) by forming a coordinated network around the drug molecule. |

| Biogenic Metal Salts (e.g., Cu, Zn, Fe, Co) [2] [4] | Act as the central ion for forming coordination complexes with drug ligands. | Used to synthesize metal-based drugs to improve efficacy, alter pharmacological profiles, or provide novel mechanisms of action (e.g., cytotoxic agents). |

| Schrödinger Software Suite [5] | Provides computational modeling of coordination and binding environments. | Predicts binding affinity and pose of a drug candidate coordinating with a protein target using methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP). |

| Chemical Computing Group MOE [5] | A comprehensive platform for molecular modeling and simulation. | Facilitates structure-based drug design, molecular docking, and QSAR modeling to study and predict drug-target coordination. |

| FTIR Spectrometer [1] | Characterizes molecular vibrations to identify functional groups involved in coordination. | Detects shifts in vibrational peaks (e.g., C=O, N-H) to confirm the atoms of a drug ligand involved in binding to a metal ion. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) [1] | Images the surface morphology and particle size of solid materials. | Reveals the physical form (e.g., crystals, amorphous aggregates) of synthesized metal-drug complexes or API particles after processing. |

Visualization of Coordination Pathways and Workflows

Coordination in Drug Action: From Metal Complex to Therapeutic Effect

The therapeutic action of metal-based drugs involves a critical coordination-driven pathway. The diagram below illustrates the multi-step mechanism of how a metal-drug complex, such as a platinum or gold complex, exerts its cytotoxic effect.

Diagram 2: Metal-Drug Complex Therapeutic Pathway

Integrated Workflow for AI-Guided Drug Coordination Design

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized the design of molecules with optimized coordination properties. This workflow charts the integrated computational and experimental cycle for AI-guided drug design, from initial data processing to lead optimization.

Diagram 3: AI-Guided Drug Design Workflow

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that coordination is a unifying principle across diverse pharmaceutical disciplines, from enhancing drug solubility with Deep Eutectic Solvents to designing novel metal-based chemotherapeutics and predicting drug-target interactions with AI. The choice of coordination system is not a matter of superiority but of strategic application, dictated by the specific pharmaceutical challenge. Metal complexes offer unique mechanisms of action, DES provide a tunable platform for formulation, and AI models deliver predictive power for rapid optimization.

The future of coordination in pharmaceuticals lies in the intelligent integration of these systems. The experimental protocols and toolkits detailed herein provide a foundation for researchers to manipulate coordination environments deliberately. As characterization techniques become more advanced and computational models more accurate, the precision with which we can engineer these interactions will only increase. This will inevitably lead to a new generation of therapeutics with enhanced efficacy, reduced side effects, and tailored biological fates, solidifying the role of coordination environment analysis as a cornerstone of modern drug development.

The Role of Network Analysis in Mapping Drug-Target Interactions and Multiscale Mechanisms

Network analysis has emerged as a transformative approach in pharmacology, enabling researchers to move beyond the traditional "one drug, one target" paradigm to a more comprehensive understanding of drug action within complex biological systems. Systems pharmacology represents an evolution in this field, using computational and experimental systems biology approaches to expand network analyses across multiple scales of biological organization, explaining both therapeutic and adverse effects of drugs [7]. This methodology stands in stark contrast to earlier black-box approaches that treated cellular and tissue-level systems as opaque, often leading to confounding situations during drug discovery when promising cell-based assays failed to translate to in vivo efficacy or produced unpredictable adverse events [7].

The fundamental principle of network analysis in pharmacology involves representing biological entities as nodes (such as genes, proteins, drugs, and diseases) and their interactions as edges (including protein-protein interactions, drug-target interactions, or transcriptional regulation) [7]. This network perspective allows researchers to explicitly track drug effects from atomic-level interactions to organismal physiology, creating explicit relationships between different scales of organization—from molecular and cellular levels to tissue, organ, and ultimately organismal levels [7]. The application of network analysis in pharmacology has become increasingly crucial as we recognize that most complex diseases involve perturbations to multiple biological pathways and networks rather than single molecular defects.

Comparative Analysis of Network-Based Methodologies

Network-based approaches for mapping drug-target interactions (DTIs) can be broadly categorized into several methodological frameworks, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. The current landscape is dominated by three primary approaches: ligand similarity-based methods, structure-based methods, and heterogeneous network models [8]. Each methodology offers different capabilities for predicting drug-target interactions, with varying requirements for structural data, computational resources, and ability to integrate multiscale biological information.

Table 1: Comparison of Network-Based Methodologies for DTI Prediction

| Methodology | Key Features | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Similarity-Based Methods (e.g., DTiGEMS, Similarity-based CNN) | Compares drug structural similarity using SMILES or molecular fingerprints [8] | Drug chemical structures, known DTIs | Computationally efficient; leverages chemical similarity principles [8] | Overlooks dynamic interactions and complex spatial structures; assumes structurally similar drugs share targets [8] |

| Structure-Based Methods (e.g., DeepDTA, DeepDrug3D) | Uses molecular docking and 3D structural information of proteins and drugs [8] | 3D structures of targets and ligands; binding affinity data | Provides mechanistic insights into binding interactions; high accuracy when structural data available [8] | Limited to proteins with known structures; computationally intensive; requires high-quality binding data [8] |

| Heterogeneous Network Models (e.g., MVPA-DTI, iGRLDTI) | Integrates multisource data (drugs, proteins, diseases, side effects) into unified network [8] | Multiple biological data types (sequence, interaction, phenotypic) | Captures higher-order relationships; works with sparse data; integrates biological context [8] | Complex model architecture; requires careful integration of heterogeneous data sources [8] |

| Large Language Model Applications (e.g., MolBERT, ProtT5) | Applies protein-specific LLMs to extract features from sequences [8] | Protein sequences, drug molecular representations | Does not require 3D structures; captures functional relevance from sequences; generalizes well [8] | Limited direct structural insights; dependent on pretraining data quality and coverage [8] |

Performance Comparison of DTI Prediction Methods

Quantitative evaluation of network-based DTI prediction methods reveals significant differences in performance metrics across benchmark datasets. The integration of multiple data types and advanced neural network architectures in recent heterogeneous network models has demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional approaches.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of DTI Prediction Methods

| Method | AUROC | AUPR | Accuracy | F1-Score | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVPA-DTI (Proposed) | 0.966 [8] | 0.901 [8] | - | - | Multiview path aggregation; molecular attention transformer; Prot-T5 integration [8] |

| iGRLDTI | - | - | - | - | Edge weight regulation; regularization in GNN [8] |

| DTiGEMS+ | - | - | - | - | Similarity selection and fusion algorithm [8] |

| Similarity-based CNN | - | - | - | - | Outer product of similarity matrix; 2D CNN [8] |

| DeepDTA | - | - | - | - | Incorporates 3D structural information [8] |

The MVPA-DTI model demonstrates state-of-the-art performance, showing improvements of 1.7% in AUPR and 0.8% in AUROC over baseline methods [8]. This performance advantage stems from its ability to integrate multiple views of biological data, including drug structural information, protein sequence features, and heterogeneous network relationships.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

MVPA-DTI Workflow Implementation

The MVPA-DTI (Multiview Path Aggregation for Drug-Target Interaction) framework implements a comprehensive workflow for predicting drug-target interactions through four major phases: multiview feature extraction, heterogeneous network construction, meta-path aggregation, and interaction prediction [8]. The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow:

Protocol Details: Multiview Feature Extraction

Drug Structural Feature Extraction Protocol: The molecular attention transformer processes drug chemical structures to extract 3D conformational features through a physics-informed attention mechanism [8]. This approach begins with molecular graph representations, where atoms are represented as nodes and bonds as edges. The transformer architecture incorporates spatial distance matrices and quantum chemical properties to compute attention weights that reflect both structural and electronic characteristics of drug molecules. The output is a continuous vector representation that encodes the three-dimensional structural information critical for understanding binding interactions.

Protein Sequence Feature Extraction Protocol: The Prot-T5 model, a protein-specific large language model, processes protein sequences to extract biophysically and functionally relevant features [8]. The protocol involves feeding amino acid sequences through the pretrained transformer architecture, which has been trained on massive protein sequence databases to understand evolutionary patterns and structural constraints. The model generates contextual embeddings for each residue and global protein representations that capture functional domains, binding sites, and structural motifs without requiring explicit 3D structural information.

Protocol Details: Heterogeneous Network Construction

The heterogeneous network integrates multiple biological entities including drugs, proteins, diseases, and side effects from multisource databases [8]. The construction protocol involves:

- Node Identification: Define nodes for each entity type with unique identifiers and metadata annotations.

- Edge Establishment: Create edges based on known interactions (drug-target, drug-disease, target-disease) and similarity metrics (drug-drug similarity, target-target similarity).

- Feature Assignment: Assign the extracted drug and protein features to corresponding nodes.

- Network Validation: Verify connectivity and biological relevance through cross-referencing with established biological databases.

This constructed network serves as the foundation for the meta-path aggregation mechanism that captures higher-order relationships between biological entities.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The implementation of advanced network analysis methods for drug-target interaction prediction requires specialized computational tools and biological resources. The following table details essential research reagents and solutions used in the featured methodologies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Network Analysis in DTI Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models | Prot-T5, ProtBERT, TAPE [8] | Extract features from protein sequences; capture functional relevance without 3D structures [8] | Feature extraction from protein sequences; transfer learning for DTI prediction [8] |

| Molecular Representation | Molecular Attention Transformer, MolBERT, ChemBERTa [8] | Process drug chemical structures; generate molecular embeddings [8] | Drug feature extraction; molecular property prediction [8] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Regulation-aware GNN, Meta-path Aggregation frameworks [8] | Model heterogeneous biological networks; learn node representations [8] | Heterogeneous network construction; relationship learning between biological entities [8] |

| Interaction Databases | DrugBank, KEGG, STRING, BioGRID | Provide known DTIs; protein-protein interactions; pathway information | Ground truth data for model training; biological validation [7] [8] |

| Omics Technologies | Genomic sequencing; Transcriptomic profiling; Proteomic assays [7] | Generate systems-level data on drug responses; identify genetic variants affecting drug efficacy [7] | Multiscale mechanism analysis; personalized therapy development [7] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | AUROC/AUPR calculation; Cross-validation; Case study protocols [8] | Quantitative performance assessment; real-world validation [8] | Method comparison; practical utility assessment [8] |

Case Study: KCNH2 Target Application

A concrete application of the MVPA-DTI framework demonstrates its practical utility in drug discovery. For the voltage-gated inward-rectifying potassium channel KCNH2—a target relevant to cardiovascular diseases—the model was employed for candidate drug screening [8]. Among 53 candidate drugs, MVPA-DTI successfully predicted 38 as having interactions with KCNH2, with 10 of these already validated in clinical treatment [8]. This case study illustrates how network analysis approaches can significantly accelerate drug repositioning efforts by prioritizing candidates with higher probability of therapeutic efficacy.

The following diagram illustrates the network relationships and prediction workflow for the KCNH2 case study:

This case study exemplifies how heterogeneous network analysis successfully integrates multiple data types—including known drug interactions, disease associations, and protein interaction partners—to generate clinically relevant predictions for drug repositioning.

Network analysis has fundamentally transformed our approach to mapping drug-target interactions and understanding multiscale mechanisms of drug action. The progression from simple ligand-based similarity methods to sophisticated heterogeneous network models that integrate multiview biological data represents a paradigm shift in pharmacological research [7] [8]. These approaches have demonstrated superior performance in predicting drug-target interactions while providing insights into the complex network relationships that underlie both therapeutic efficacy and adverse effects.

The future of network analysis in pharmacology will likely focus on several key areas: (1) enhanced integration of multiscale data from genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics; (2) development of more interpretable models that provide mechanistic insights alongside predictive accuracy; (3) application to personalized medicine through incorporation of individual genomic variation; and (4) expansion to model dynamic network responses to drug perturbations over time [7]. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will increasingly enable the prediction of therapeutic efficacy and adverse event risk for individuals prior to commencement of therapy, ultimately fulfilling the promise of personalized precision medicine [7].

Systems pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in pharmacology, applying computational and experimental systems biology approaches to the study of drugs, drug targets, and drug effects [9] [10]. This framework moves beyond the traditional "one drug, one target" model to consider drug actions within the complex network of biological systems, enabling a more comprehensive analysis of both therapeutic and adverse effects [11]. By studying drugs in the context of cellular networks, systems pharmacology provides insights into adverse events caused by off-target drug interactions and complex network responses, allowing for rapid identification of biomarkers for side effect susceptibility [9].

The approach integrates large-scale experimental studies with computational analyses, focusing on the functional interactions within biological networks rather than single transduction pathways [11]. This network perspective is particularly valuable for understanding complex patterns of drug action, including synergy and oscillatory behavior, as well as disease progression processes such as episodic disorders [11]. The ultimate goal of systems pharmacology is to develop not only more effective therapies but also safer medications with fewer side effects through predictive modeling of therapeutic efficacy and adverse event risk [9] [10].

Methodological Framework and Comparison with Alternative Approaches

Core Principles of Systems Pharmacology

Systems pharmacology employs mechanistically oriented modeling that integrates drug exposure, target biology, and downstream effectors across molecular, cellular, and pathophysiological levels [12]. These models characterize fundamental properties of biological systems behavior, including hysteresis, non-linearity, variability, interdependency, convergence, resilience, and multi-stationarity [11]. The framework is particularly useful for describing effects of multi-target interactions and homeostatic feedback on pharmacological response, distinguishing symptomatic from disease-modifying effects, and predicting long-term impacts on disease progression from short-term biomarker responses [11].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP), a specialized form of this approach, has demonstrated significant impact across the drug development continuum [12]. QSP models integrate drug disposition characteristics, target binding kinetics, and transduction dynamics to create a common drug-exposure and disease "denominator" for performing quantitative comparisons [12]. This enables researchers to compare compounds of interest against later-stage development candidates or marketed products, evaluate different therapeutic modalities for a given target, and optimize dosing regimens based on simulated efficacy and safety metrics [12].

Comparative Analysis with Other Pharmacological Methods

Systems pharmacology differs fundamentally from traditional pharmacological approaches and other modern techniques in its theoretical foundation and application. The table below provides a structured comparison of these methodologies:

Table 1: Comparison of Systems Pharmacology with Alternative Methodological Approaches

| Methodology | Theoretical Foundation | Application Scope | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems Pharmacology | Network analysis of biological systems; computational modeling of drug-target interactions [9] | Prediction of therapeutic and adverse effects through network context [9] [11] | Large-scale experimental data, network databases, computational resources [10] | Identifies multi-scale mechanisms; predicts network-level effects [10]; enables target identification and polypharmacology [9] | Complex model development; requires multidisciplinary expertise; computational intensity |

| Gene Chip Technology | Experimental high-throughput screening; microarray hybridization of known gene sequences [13] | Target prediction through experimental measurement of gene expression changes | Gene chips, laboratory equipment for RNA processing and hybridization | Direct experimental measurement; does not require prior published data | Higher cost; longer time requirements; experimental variability [13] |

| Traditional PK/PD Modeling | Physiology-based pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models with linear transduction pathways [11] | Characterization of drug disposition and effect relationships using simplified pathways | Clinical PK/PD data, drug concentration measurements | Established regulatory acceptance; simpler mathematical framework | Fails to explain complex network interactions; limited prediction of adverse events [11] |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Mechanistic modeling connecting drug targets to clinical endpoints across biological hierarchies [12] [14] | Dose selection and optimization; safety differentiation; combination therapy decisions [12] [14] | Systems biology data, omics technologies, knowledge bases, clinical endpoints [12] | Supports regulatory submissions; enables virtual patient populations; predicts long-term outcomes [14] | High resource investment; model qualification challenges; specialized expertise required |

Experimental Evidence: Direct Comparison Study

A 2022 comparative study directly evaluated the performance of systems pharmacology against gene chip technology for predicting targets of ZhenzhuXiaojiTang (ZZXJT), a traditional Chinese medicine formula for primary liver cancer [13]. The research provided quantitative experimental data on the relative performance of these approaches:

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Target Prediction Performance Between Systems Pharmacology and Gene Chip Technology

| Performance Metric | Systems Pharmacology | Gene Chip Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Identified Target Rate | 17% of predicted targets | 19% of predicted targets |

| Molecular Docking Performance | Top ten targets demonstrated better binding free energies | Inferior binding free energies compared to systems pharmacology |

| Core Drug Prediction Consistency | High consistency with experimental results | High consistency with experimental results |

| Core Small Molecule Prediction | Moderate consistency | Moderate consistency |

| Methodological Advantages | Cost-effective; time-efficient; leverages existing research data [13] | Direct experimental measurement; no prior data requirement |

| Methodological Limitations | Dependent on quality of existing databases | Higher cost; longer experimental duration; technical variability |

This experimental comparison demonstrated that while gene chip technology identified a slightly higher percentage of targets (19% vs. 17%), the systems pharmacology approach predicted targets with superior binding energies in molecular docking studies, suggesting higher quality predictions [13]. Furthermore, systems pharmacology achieved these results with significantly reduced cost and time requirements, highlighting its efficiency advantages for initial target screening and hypothesis generation [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for Systems Pharmacology Analysis

The implementation of systems pharmacology follows a structured workflow that ensures reproducible development and qualification of models. This workflow encompasses data programming, model development, parameter estimation, and qualification [12]. The progressive maturation of this workflow represents a necessary step for efficient, reproducible development of QSP models, which are inherently iterative and evolutive [12].

Table 3: Core Components of a Standardized Systems Pharmacology Workflow

| Workflow Component | Key Features | Implementation Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Data Programming | Conversion of raw data to standard format; creation of master dataset for exploration [12] | Common data format for QSP and population modeling; automated data processing |

| Model Development | Multiconditional model setup; handling of heterogeneous datasets; flexible model structures [12] | Ordinary differential equations; possible agent-based or partial differential equation components |

| Parameter Estimation | Multistart strategy for robust optimization; assessment of parameter identifiability [12] | Profile likelihood method; Fisher information matrix; confidence interval computation |

| Model Qualification | Evaluation of model performance across experimental conditions; assessment of predictive capability [12] | Visual predictive checks; benchmarking against experimental data; sensitivity analysis |

Detailed Protocol for Network-Based Target Identification

The following experimental protocol outlines the standard methodology for identifying drug targets using systems pharmacology, as applied in the ZZXJT case study [13]:

Screening of Active Ingredients and Targets

- Source active ingredients from relevant databases (e.g., Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database - TCMSP)

- Apply ADME-based screening criteria (Oral Bioavailability ≥ 30%; Drug-likeness ≥ 0.18)

- Remove ingredients without known targets and integrate target protein information

- Normalize target information using standardized protein databases (UniProt)

Disease Target Identification

- Mine disease-related targets from specialized databases (OMIM, GeneCards)

- Apply relevance score filtering (e.g., GeneCards relevance score ≥ 15)

- Merge data from multiple sources to create comprehensive disease target dataset

Network Construction and Analysis

- Identify intersecting targets between drug and disease using Venn diagrams

- Submit intersecting targets to interaction databases (STRING) to construct Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks

- Set appropriate confidence levels (≥ 0.4) and organism parameters (Homo sapiens)

- Import networks to visualization software (Cytoscape) and analyze core potential proteins by "combined degree" values

Gene Enrichment Analysis

- Perform pathway analysis using specialized databases (Metascape)

- Conduct Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis

- Execute Gene Ontology (GO) analysis across three categories: Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF)

- Apply appropriate statistical thresholds (p < 0.01) and display results using data visualization tools

Experimental Validation through Molecular Docking

To validate predictions from systems pharmacology, molecular docking serves as a critical experimental confirmation step [13]. The protocol includes:

- Preparation of Predicted Targets: Select top target proteins from systems pharmacology predictions

- Ligand Preparation: Generate 3D structures of active compounds identified through systems pharmacology screening

- Docking Simulation: Perform computational docking studies to evaluate binding interactions and calculate binding free energies

- Benchmark Comparison: Compare docking results with positive control targets to assess relative performance against alternative prediction methods

This validation approach demonstrated that systems pharmacology predictions had superior binding free energies compared to gene chip-based predictions, confirming the method's value for identifying high-quality targets [13].

Visualization of Systems Pharmacology Framework

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and network interactions in systems pharmacology, highlighting the integration of data sources, computational modeling, and outcome prediction:

Figure 1: Systems Pharmacology Workflow Integrating Multiscale Data for Therapeutic and Adverse Effect Prediction

Implementation of systems pharmacology requires specialized databases, software tools, and computational resources. The following table catalogs essential research reagents and solutions for conducting systems pharmacology research:

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Systems Pharmacology Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | TCMSP (Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database) [13] | Active ingredient identification and ADME screening | Initial compound screening for natural products and traditional medicines |

| Target Databases | UniProt Protein Database [13] | Protein target normalization and standardization | Unified target information across multiple data sources |

| Disease Target Resources | OMIM, GeneCards [13] | Disease-related target mining and prioritization | Identification of pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets |

| Network Analysis Tools | STRING Database [13] | Protein-protein interaction network construction | Contextualizing drug targets within cellular networks and pathways |

| Visualization Software | Cytoscape [13] | Network visualization and analysis | Identification of core network components and key targets |

| Pathway Analysis Resources | Metascape [13] | Gene enrichment analysis and functional annotation | Biological interpretation of target lists through KEGG and GO analysis |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock, Schrödinger Suite | Validation of target-compound interactions through binding energy calculations | Experimental confirmation of predicted drug-target interactions |

| QSP Modeling Platforms | MATLAB, R, Python with specialized systems biology libraries | Mathematical model development, simulation, and parameter estimation | Implementation of multiscale mechanistic models for drug and disease systems |

Regulatory Applications and Impact Assessment

The implementation of systems pharmacology, particularly Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP), has demonstrated significant impact in regulatory decision-making. Landscape analysis of regulatory submissions to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reveals increasing adoption of these approaches [14]. Since 2013, there has been a notable increase in QSP submissions in Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, New Drug Applications (NDAs), and Biologics License Applications (BLAs) [14].

The primary applications of QSP in regulatory contexts include dose selection and optimization, safety differentiation between drug classes, and rational selection of immuno-oncology drug combinations [12] [14]. These models provide a common framework for comparing compounds within a dynamic pathophysiological context, enabling fair comparisons between investigational drugs and established therapies [12]. The growing regulatory acceptance of QSP underscores the maturity and impact of systems pharmacology approaches in modern drug development.

QSP has proven particularly valuable in supporting efficacy and safety differentiation within drug classes, as demonstrated by applications comparing sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes treatment [12]. Additionally, QSP models have enabled rational selection of immuno-oncology combination therapies based on efficacy projections, addressing the exponential growth in potential combination options [12]. These applications highlight how systems pharmacology frameworks facilitate more informed decision-making throughout the drug development pipeline, from early discovery to regulatory submission and post-market optimization.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally reshaping the pharmaceutical landscape, from accelerating drug discovery to optimizing manufacturing processes. This technological shift presents both unprecedented opportunities and unique challenges for global regulators tasked with ensuring patient safety, product efficacy, and data integrity. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have emerged as pivotal forces in establishing governance for these advanced tools. While both agencies share the common goal of protecting public health, their regulatory philosophies, approaches, and technical requirements are developing with distinct characteristics. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, navigating this complex and evolving regulatory environment is essential for the successful integration of AI into the medicinal product lifecycle. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the FDA and EMA frameworks, offering a foundational understanding of their current oversight structures for AI and complex data [15] [16].

Comparative Analysis of FDA and EMA Regulatory Philosophies

The FDA and EMA are spearheading the development of regulatory pathways for AI, but their approaches reflect different institutional priorities and legal traditions. The following table summarizes the core philosophical and practical differences between the two agencies.

Table 1: Core Philosophical Differences Between FDA and EMA AI Regulation

| Aspect | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | European Medicines Agency (EMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Philosophy | Pragmatic, risk-based approach under existing statutory authority [16]. | Prescriptive, control-oriented, and ethics-focused, integrated with new legislation like the AI Act [15] [16]. |

| Guiding Principle | Establishes model "credibility" for a specific "Context of Use (COU)" [15]. | Extends well-established Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) principles to AI, prioritizing predictability and control [15]. |

| Scope of Initial Guidance | Broad, covering the entire product lifecycle (non-clinical, clinical, manufacturing) where AI supports regulatory decisions [17] [15]. | Narrower and more deliberate, initially focused on "critical applications" in manufacturing via GMP Annex 22 [15]. |

| Approach to Model Adaptivity | Accommodates adaptive AI through a "Life Cycle Maintenance Plan," creating a pathway for continuous learning [15]. | Restrictive; proposed GMP Annex 22 prohibits adaptive models in critical processes, allowing only static, deterministic models [15]. |

| Primary Regulatory Tool | Draft guidance: "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence..." (Jan 2025) [17] [15]. | Reflection paper (2024); proposed GMP Annex 22 on AI; EU AI Act [18] [15] [19]. |

The FDA's strategy is characterized by flexibility. Its central doctrine is the "Context of Use (COU)", which means the agency evaluates the trustworthiness of an AI model for a specific, well-defined task within the drug development pipeline. This allows for a nuanced, risk-based assessment rather than a one-size-fits-all rule. The FDA's choice of the term "credibility" over the traditional "validation" is significant, as it acknowledges the probabilistic nature of AI systems and allows for acceptance if the COU includes appropriate risk mitigations [15].

In contrast, the EMA's approach, particularly for manufacturing, is deeply rooted in the established principles of GMP: control, predictability, and validation. The proposed GMP Annex 22 seeks to integrate AI into this existing framework rather than create a entirely new paradigm. This results in a more restrictive and prescriptive stance, especially regarding the types of AI models permitted. The Annex explicitly mandates the use of only static and deterministic models in critical GMP applications, effectively prohibiting continuously learning AI, generative AI, and Large Language Models (LLMs) in these settings due to their inherent variability [15].

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical progression of the two regulatory pathways, from development to ongoing oversight.

Detailed Framework Requirements and Experimental Protocols

For researchers, understanding the specific technical and documentation requirements is crucial for compliance. Both regulators demand rigorous evidence of an AI model's safety, performance, and robustness, though the nature of this evidence differs.

The FDA's Credibility Assessment Framework

The FDA's draft guidance outlines a multi-step, risk-based framework for establishing and documenting an AI model's credibility for its intended COU [15]. The agency's assessment of risk is a function of "model influence" (how much the output drives a decision) and "decision consequence" (the impact of an incorrect decision on patient health or product quality) [15].

Table 2: Key Phases of the FDA's AI Model Credibility Assessment

| Phase | Core Objective | Key Documentation & Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Definition | Precisely define the question the AI model will address and its specific Context of Use (COU). | A detailed COU specification document describing the model's purpose, operating environment, and how outputs inform decisions [15]. |

| 2. Risk Assessment | Evaluate the model's risk level based on its influence and the consequence of an error. | A risk assessment report classifying the model as low, medium, or high risk, justifying the classification with a defined risk matrix [15]. |

| 3. Planning | Develop a tailored Credibility Assessment Plan to demonstrate trustworthiness for the COU. | A comprehensive plan detailing data management strategies, model architecture, feature selection, and evaluation methods using independent test data [15] [20]. |

| 4. Execution & Monitoring | Execute the plan and ensure ongoing performance through the product lifecycle. | Model validation reports, performance metrics on test data, and a Life Cycle Maintenance Plan for monitoring and managing updates [15]. |

A critical component of the FDA's framework is the Life Cycle Maintenance Plan. This plan acts as a regulatory gateway for adaptive AI systems, requiring sponsors to outline [15]:

- Performance monitoring metrics and frequency

- Triggers for model re-testing or re-validation

- Procedures for managing and documenting model updates

The EMA's Principles for AI in the Medicinal Product Lifecycle

The EMA's approach, detailed in its reflection paper and supported by the network's AI workplan, emphasizes a human-centric approach where AI use must comply with existing legal frameworks and ethical standards [18] [19]. For manufacturing specifically, the proposed GMP Annex 22 is highly prescriptive.

Table 3: Core Requirements under EMA's Proposed GMP Annex 22 for AI

| Requirement Category | EMA Expectation & Protocol |

|---|---|

| Model Type & Explainability | Only static, deterministic models are permitted for critical applications. "Black box" models are unacceptable; models must be explainable, and outputs should include confidence scores for human review [15]. |

| Data Integrity & Testing | Test data must be completely independent of training data, representative of full process variation, and accurately labeled by subject matter experts. Use of synthetic data is discouraged [15]. |

| Human Oversight & Accountability | Formalized "Human-in-the-Loop" (HITL) oversight is required. Ultimate responsibility for GMP decisions rests with qualified personnel, not the algorithm [15]. |

| Change Control | Deployed models are under strict change control. Any modification to the model, system, or input data sources requires formal re-evaluation [15]. |

The following workflow diagram synthesizes the core experimental and validation protocols that researchers should embed into their AI development process to meet regulatory expectations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for AI Regulation

For scientists and developers building AI solutions for the regulated pharmaceutical space, the following "reagents" or core components are essential for a successful regulatory submission.

Table 4: Essential Components for AI Research and Regulatory Compliance

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose in the Regulatory Context |

|---|---|

| Context of Use (COU) Document | Precisely defines the model's purpose, boundaries, and role in decision-making. This is the foundational document for any regulatory evaluation [15]. |

| Credibility Assessment Plan (FDA) | A tailored protocol detailing how the model's trustworthiness will be established for its specific COU, including data strategy, evaluation methods, and acceptance criteria [15]. |

| Independent Test Dataset | A held-out dataset, completely separate from training and tuning data, used to provide an unbiased estimate of the model's real-world performance [15] [20]. |

| Model Card | A standardized summary document included in labeling (for devices) or submission packages that communicates key model information, such as intended use, architecture, performance, and limitations [20]. |

| Bias Detection & Mitigation Framework | A set of tools and protocols used to identify, quantify, and address potential biases in the training data and model outputs to ensure fairness and generalizability [20] [21]. |

| Life Cycle Maintenance Plan | A forward-looking plan that outlines the procedures for ongoing performance monitoring, drift detection, and controlled model updates post-deployment [15]. |

The regulatory environment for AI in pharmaceuticals is dynamic and complex, with the FDA and EMA forging distinct but equally critical paths. The FDA's flexible, risk-based "credibility" framework offers a pathway for a wide array of AI applications across the drug lifecycle, including those that are adaptive. In contrast, the EMA's prescriptive, control-oriented approach, particularly in manufacturing, prioritizes stability and absolute understanding through strict model constraints. For the global research and development community, success hinges on embedding regulatory thinking into the earliest stages of AI project planning. By understanding these frameworks, implementing robust experimental and data governance protocols, and proactively engaging with regulators, scientists and drug developers can harness the power of AI to bring innovative treatments to patients safely and efficiently.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into drug development represents a paradigm shift, offering the potential to accelerate discovery, optimize clinical trials, and personalize therapeutics. However, this promise is tempered by a complex set of challenges that form the core of this analysis. Within the framework of coordination environment analysis techniques, this guide examines three interdependent obstacles: the inherent opacity of black-box AI models, the pervasive risk of data bias, and the increasingly fragmented international regulatory landscape. The inability to fully understand, control, and standardize AI systems creates a precarious coordination environment for researchers, regulators, and industry sponsors alike. This article objectively compares the performance and characteristics of different approaches to these challenges, providing drug development professionals with a structured analysis of the current ecosystem.

The Black Box Problem: Interpretability vs. Performance

A "black box" AI describes a system where internal decision-making processes are opaque, meaning users can observe inputs and outputs but cannot discern the logic connecting them [22]. This is not an edge case but a fundamental characteristic of many advanced machine learning models, including the large language models (LLMs) and deep learning networks powering modern AI tools [23].

Comparative Analysis of AI Model Transparency

The trade-off between model performance and interpretability is a central tension in the field. The table below compares different types of AI models based on their transparency and applicability in drug development.

Table 1: Comparison of AI Model Types in Drug Development

| Model Type | Interpretability | Typical Applications in Drug Development | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Rule-Based AI | High (White Box) | Automated quality control, operational workflows | Limited power and flexibility for complex tasks [22] |

| Traditional Machine Learning (e.g., Logistic Regression) | High (White Box) | Preliminary patient stratification, initial data analysis | Lower predictive accuracy on complex, unstructured data [22] |

| Deep Learning/LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Claude) | Low (Black Box) | Drug discovery, molecular behavior prediction, original content creation [22] [24] | Opacity conceals biases, vulnerabilities, and reasoning [22] [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Interpretability

Researchers are developing techniques to peer into the black box. The following experimental methodologies are central to evaluating model interpretability:

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): This technique creates simpler, local surrogate models that approximate the behavior of the original complex model around a specific prediction. It helps identify which input features most influenced a single decision, making the model's local behavior more understandable [25].

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Based on cooperative game theory, SHAP assigns each feature an "importance" value for a particular prediction. It quantifies the contribution of each feature to the difference between the actual prediction and a baseline prediction, providing a consistent and globally relevant measure of feature importance [25].

- Counterfactual (CF) Approximation Methods: These methods involve systematically modifying input data (e.g., a specific text concept) and observing changes in the model's output. This helps researchers approximate how a model's decision would change if certain factors were different, aiding in causal effect estimation [25].

The diagram below illustrates a typical experimental workflow for interpreting a black-box AI model in a research setting.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Interpreting a Black-Box AI Model

Bias in AI is a systematic and unfair discrimination that arises from flaws in data, algorithmic design, or human decision-making during development [26] [27]. In drug development, biased models can lead to skewed predictions, unequal treatment outcomes, and the perpetuation of existing health disparities.

Typology and Comparative Impact of AI Bias

Bias can infiltrate AI systems at multiple stages. The following table classifies common types of bias and their potential impact on drug development processes.

Table 2: Types of AI Bias and Their Impact in Drug Development

| Bias Type | Source | Impact Example in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Data/Sampling Bias [26] [27] | Training data doesn't represent the target population. | Medical imaging algorithms for skin cancer show lower accuracy for darker skin tones if trained predominantly on lighter-skinned individuals [26]. |

| Historical Bias [26] | Past discrimination patterns are embedded in training data. | An AI model for patient recruitment might under-represent certain demographics if historical clinical trial data is non-diverse [26] [28]. |

| Algorithmic Bias [27] | Algorithm design prioritizes efficiency over fairness. | A model optimizing for trial speed might inadvertently select healthier, less diverse patients, limiting the generalizability of results. |

| Measurement Bias [26] | Inconsistent or flawed data collection methods. | Pulse oximeter algorithms overestimated blood oxygen levels in Black patients, leading to delayed treatment decisions during COVID-19 [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Mitigating bias requires a proactive, lifecycle approach. The experimental protocols for bias mitigation are often categorized by when they are applied:

Pre-processing Mitigation: These techniques modify the training data itself before model training. Methods include:

- Resampling: Systematically adding copies of instances from under-represented groups or removing instances from over-represented groups to create a balanced dataset [29].

- Reweighting: Assigning higher weights to instances from under-represented groups during the model training process to ensure they have a stronger influence on the learning algorithm [29].

- Disparate Impact Remover: A pre-processing algorithm that edits feature values to improve group fairness while preserving the data's utility [29].

In-processing Mitigation: These techniques modify the learning algorithm itself to incorporate fairness constraints.

- Adversarial Debiasing: An adversarial network architecture where a primary model learns to make predictions, while an adversary simultaneously tries to predict the sensitive attribute (e.g., race, gender) from the primary model's predictions. The primary model is trained to maximize predictive accuracy while minimizing the adversary's ability to predict the sensitive attribute, thus removing bias [29].

- Fairness Constraints: Incorporating mathematical fairness definitions (e.g., demographic parity, equalized odds) directly into the model's objective function as regularization terms [29].

Post-processing Mitigation: These techniques adjust the model's outputs after training.

- Threshold Adjustment: Applying different decision thresholds for different demographic groups to equalize error rates (e.g., false positive rates) [29].

- Output Calibration: Calibrating the model's probability scores for different subgroups to ensure they reflect true likelihoods equally well across groups.

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between these mitigation strategies and the machine learning lifecycle.

Diagram Title: AI Bias Mitigation Strategies in the ML Lifecycle

International Regulatory Divergence: A Comparative Analysis

As AI transforms drug development, regulatory agencies worldwide are developing frameworks to ensure safety and efficacy. However, a lack of alignment in these approaches creates significant challenges for global drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

The following table compares the evolving regulatory approaches to AI in drug development across major international agencies.

Table 3: Comparison of International Regulatory Approaches to AI in Drug Development

| Regulatory Agency | Key Guidance/Document | Core Approach | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | "Considerations for the Use of AI to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Drug and Biological Products" (Draft, 2025) [24] | Risk-based "Credibility Assessment Framework" centered on the "Context of Use" (COU) [24] [30]. | Focuses on the AI model's specific function and scope in addressing a regulatory question. Acknowledges challenges like data variability and model drift [24]. |

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) | "Reflection Paper on the Use of AI in the Medicinal Product Lifecycle" (2024) [24] | Structured and cautious, prioritizing rigorous upfront validation and comprehensive documentation [24]. | Issued its first qualification opinion on an AI methodology for diagnosing inflammatory liver disease in 2025, accepting AI-generated clinical trial evidence [24]. |

| UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) | "Software as a Medical Device" (SaMD) and "AI as a Medical Device" (AIaMD) principles [24] | Principles-based regulation; utilizes an "AI Airlock" regulatory sandbox to test innovative technologies [24]. | The sandbox allows for real-world testing and helps the agency identify regulatory challenges. |

| Japan's Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) | "Post-Approval Change Management Protocol for AI-SaMD" (2023) [24] | "Incubation function" to accelerate access; formalized process for managing post-approval AI changes. | The PACMP allows predefined, risk-mitigated modifications to AI algorithms post-approval without full resubmission, facilitating continuous improvement [24]. |

Experimental Protocol for Regulatory Compliance: The Context of Use (COU) Framework

A key experimental and documentation protocol emerging from the regulatory landscape is the FDA's Context of Use (COU) framework [24] [30]. For a researcher or sponsor, defining the COU is a critical first step in preparing an AI tool for regulatory evaluation. The protocol involves:

- Defining the Purpose: Precisely articulate the AI model's function within the drug development process (e.g., "to predict patient risk of a specific adverse event from Phase 2 clinical trial data").

- Specifying the Scope: Detail the boundaries of the model's application, including the target population, input data types, and the specific decisions or outputs it will inform.

- Linking to Regulatory Impact: Clearly state how the AI-generated information will be used to support a specific regulatory decision regarding safety, efficacy, or quality.

- Conducting a Risk-Based Credibility Assessment: Following the FDA's draft guidance, build evidence to establish trust in the model's output for the defined COU. This involves a seven-step process focusing on the model's reliability, which includes evaluating data quality, model design, and performance [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To effectively navigate the challenges outlined, researchers require a suite of methodological and software tools. The following table details key "research reagents" for developing responsible AI in drug development.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Addressing AI Challenges

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIME & SHAP [25] | Software Library | Provide local and global explanations for model predictions. | Black-Box Interpretability |

| AI Fairness 360 (AIF360) [29] | Open-Source Toolkit (IBM) | Provides a comprehensive set of metrics and algorithms for testing and mitigating bias. | Data Bias Mitigation |

| Fairlearn [29] | Open-Source Toolkit (Microsoft) | Assesses and improves the fairness of AI systems, supporting fairness metrics and mitigation algorithms. | Data Bias Mitigation |

| Context of Use (COU) Framework [24] [30] | Regulatory Protocol | Defines the specific circumstances and purpose of an AI tool's application for regulatory submissions. | Regulatory Compliance |

| Federated Learning [28] | Technical Approach | Enables model training across decentralized data sources without sharing raw data, helping address privacy and data access issues. | Data Bias & Regulatory Hurdles |

| Disparate Impact Remover [29] | Pre-processing Algorithm | Edits dataset features to prevent discrimination against protected groups while preserving data utility. | Data Bias Mitigation |

| Adversarial Debiasing [29] | In-processing Algorithm | Uses an adversarial network to remove correlation between model predictions and protected attributes. | Data Bias Mitigation |

The coordination environment for AI in drug development is defined by the intricate interplay of technical opacity (black-box models), embedded inequities (data bias), and disparate governance (regulatory divergence). A comparative analysis reveals that while highly interpretable models offer transparency, they often lack the power required for complex tasks like molecular design. Conversely, the superior performance of black-box deep learning models comes with significant trade-offs in explainability and trust. Furthermore, the effectiveness of bias mitigation strategies is highly dependent on when they are applied in the AI lifecycle and the accuracy of the data they use. The emerging regulatory frameworks from the FDA, EMA, and PMDA, while converging on risk-based principles, demonstrate key divergences in their practical application, creating a complex landscape for global drug development. Success in this field will therefore depend on a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach that prioritizes explainability techniques, embeds bias mitigation throughout the AI lifecycle, and actively engages with the evolving international regulatory dialogue.

Advanced Analytical and Computational Methods for Coordination Analysis

The quantitative detection of drugs and their metabolites is a critical challenge in modern pharmaceutical research, therapeutic drug monitoring, and clinical toxicology. Within the broader context of coordination environment analysis techniques, electroanalytical methods provide powerful tools for studying speciation, reactivity, and concentration of pharmaceutical compounds. Among these techniques, voltammetry and potentiometry have emerged as versatile approaches with complementary strengths for drug analysis [31] [32]. Voltammetric techniques measure current resulting from electrochemical oxidation or reduction of analytes under controlled potential conditions, offering exceptional sensitivity for direct drug quantification [31] [33]. Potentiometry measures potential differences at zero current, providing unique information about ion activities and free drug concentrations that often correlate with biological availability [32]. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics, applications, and limitations of these techniques specifically for pharmaceutical analysis, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers' selection of appropriate analytical strategies.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Basis

Theoretical Foundations

Voltammetry encompasses a group of techniques that measure current as a function of applied potential to study electroactive species. The potential is varied in a controlled manner, and the resulting faradaic current from oxidation or reduction reactions at the working electrode surface is measured [31] [34]. The current response is proportional to analyte concentration, enabling quantitative determination of drugs and metabolites. Common voltammetric techniques include cyclic voltammetry (CV), square wave voltammetry (SWV), and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), with SWV being particularly advantageous for trace analysis due to its effective background current suppression [34].

Potentiometry measures the potential difference between two electrodes (indicator and reference) at zero current flow in an electrochemical cell [35] [32]. This potential develops across an ion-selective membrane and relates to the activity of the target ion through the Nernst equation: E = K + (RT/zF)lnaᵢ, where E is the measured potential, K is a constant, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is ion charge, F is Faraday's constant, and aᵢ is the ion activity [32]. Potentiometric sensors detect the thermodynamically active, or free, concentration of ionic drugs, which is often the biologically relevant fraction [32].

Comparative Response Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental Response Characteristics of Voltammetry and Potentiometry

| Feature | Voltammetry | Potentiometry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Current (amperes) | Potential (volts) |

| Fundamental Relationship | Current proportional to concentration | Nernst equation: logarithmic dependence on activity |

| Analytical Information | Concentration of electroactive species | Activity of free ions |

| Detection Limit Definition | Signal-to-noise ratio (3× standard deviation of noise) | Intersection of linear response segments [32] |

| Typical Measurement Time | Seconds to minutes | Seconds to establish equilibrium |

| Key Advantage | Excellent sensitivity for trace analysis | Information on free concentration/bioavailability |

Performance Comparison in Drug Analysis

Detection Limits and Sensitivity

Voltammetry generally offers superior sensitivity for trace-level drug analysis, with detection limits frequently extending to nanomolar or even picomolar ranges when advanced electrode modifications are employed [31] [33]. For instance, a carbon nanotube/nickel nanoparticle-modified electrode achieved a detection limit of 15.82 nM for the anti-hepatitis C drug daclatasvir in human serum [33]. Square wave voltammetry is particularly effective for trace analysis, with capabilities to detect analytes at nanomolar concentrations due to effective background current suppression [34].

Potentiometric sensors have undergone significant improvements, with modern designs achieving detection limits in the range of 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹¹ M for total sample concentrations [32]. It is crucial to note that the definition of detection limits differs between techniques, with potentiometry using a unique convention based on the intersection of linear response segments rather than signal-to-noise ratio [32]. When calculated according to traditional protocols (three times standard deviation of noise), potentiometric detection limits are approximately two orders of magnitude lower than those reported using the potentiometric convention [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Detection Capabilities for Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Technique | Representative Drug Analyte | Achieved Detection Limit | Linear Range | Sample Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square Wave Voltammetry | Daclatasvir (anti-HCV drug) | 15.82 nM | 0.024-300 µM | Human serum, tablets [33] |

| Voltammetry (carbon-based sensors) | Multiple antidepressants | Low nanomolar range | Varies by compound | Pharmaceutical formulations, clinical samples [31] |

| Potentiometry (Pb²⁺ ISE) | Lead ions (model system) | 8×10⁻¹¹ M | Not specified | Drinking water [32] |

| Potentiometry (Ca²⁺ ISE) | Calcium ions (model system) | ~10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻¹¹ M | Not specified | Aqueous solutions [32] |

Selectivity and Interference Considerations

Voltammetric selectivity depends on the redox potential of the target analyte relative to potential interferents. Electrode modifications with selective recognition elements (molecularly imprinted polymers, enzymes, or selective complexing agents) can significantly enhance selectivity [31] [33]. Carbon-based electrodes modified with nanomaterials offer excellent electrocatalytic properties that improve selectivity for specific drug compounds [31].

Potentiometric selectivity is governed by the membrane composition and is quantitatively described by the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation: E = E⁰ + (2.303RT/zᵢF)log(aᵢ + Σkᵢⱼaⱼ^(zᵢ/zⱼ)), where kᵢⱼ is the selectivity coefficient, and aᵢ and aⱼ are activities of primary and interfering ions, respectively [35]. Low selectivity coefficient values indicate minimal interference. Modern potentiometric sensors incorporate ionophores and other selective receptors in polymeric membranes to achieve exceptional discrimination between similar ions [32].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Voltammetric Sensor for Drug Detection

Protocol: Development of Carbon Nanotube/Nickel Nanoparticle Sensor for Daclatasvir [33]

Working Electrode Preparation:

- Polish glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter) with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad

- Rinse thoroughly with distilled water and dry at room temperature

- Prepare modifier suspension by dispersing 1 mg multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) in 1 mL DMF via ultrasonic agitation for 30 minutes

- Deposit 5 µL of MWCNT suspension onto GCE surface and allow to dry

- Electrodeposit nickel nanoparticles by cycling potential between 0 and -1.1 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 15 cycles at 50 mV/s in 0.1 M NiCl₂ solution

- Rinse modified electrode with distilled water before measurements

Electrochemical Measurements:

- Use three-electrode system: modified GCE working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, platinum wire counter electrode

- Employ square wave voltammetry with parameters: potential range 0.3-0.8 V, step potential 4 mV, amplitude 25 mV, frequency 15 Hz

- Prepare drug standard solutions in supporting electrolyte (0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0)

- Record voltammograms after 60-second accumulation at open circuit with stirring

- Measure oxidation peak current at approximately 0.55 V for quantification

Validation in Real Samples:

- For tablet analysis: Powder and dissolve tablets in methanol, dilute with buffer, and analyze directly

- For human serum analysis: Dilute serum samples with buffer (1:1 ratio), centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, and analyze supernatant

Potentiometric Sensor for Trace Analysis

Protocol: Lead-Selective Electrode with Low Detection Limit [32]

Membrane Preparation:

- Prepare ion-selective membrane composition: 1.0% ionophore (lead-selective), 0.2% ionic sites (potassium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate), 65.8% plasticizer (2-nitrophenyl octyl ether), and 33.0% poly(vinyl chloride)

- Dissolve components in 3 mL tetrahydrofuran and evaporate slowly to form homogeneous membrane

- Cut membrane discs (6 mm diameter) and mount in electrode body

Electrode Assembly and Conditioning:

- Use inner filling solution containing 10⁻³ M PbCl₂ and 10⁻² M NaCl

- Incorporate chelating resin in inner solution or EDTA to minimize primary ion fluxes

- Condition assembled electrode in 10⁻³ M PbCl₂ solution for 24 hours before use

- Store in 10⁻⁵ M PbCl₂ solution when not in use

Potential Measurements:

- Use double-junction reference electrode with outer chamber filled with 0.1 M KNO₃ or 1 M LiOAc

- Measure potentials in stirred solutions at room temperature

- Allow potential stabilization until drift <0.1 mV/min

- Record EMF values starting from low to high concentrations to minimize memory effects

- Perform calibration in Pb²⁺ solutions from 10⁻¹¹ to 10⁻³ M

Data Analysis:

- Plot EMF vs. logarithm of Pb²⁺ activity

- Determine detection limit as intersection of extrapolated linear segments of the calibration curve

- Calculate selectivity coefficients using separate solution method or fixed interference method

Analytical Applications and Case Studies

Voltammetric Analysis of Psychotropic Drugs

Voltammetric techniques have been successfully applied to the detection of numerous antidepressant drugs, including agomelatine, alprazolam, amitriptyline, aripiprazole, carbamazepine, citalopram, and many others [31]. Carbon-based electrodes, particularly glassy carbon electrodes modified with carbon nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes), demonstrate excellent performance for these applications due to their wide potential windows, good electrocatalytic properties, and minimal fouling tendencies [31]. The combination of voltammetry with advanced electrode materials enables direct determination of these drugs in both pharmaceutical formulations and clinical samples with minimal sample preparation.

Electrochemical techniques also facilitate simulation of drug metabolism pathways. Using a thin-layer electrochemical cell with a boron-doped diamond working electrode, researchers have successfully mimicked cytochrome P450-mediated oxidative metabolism of psychotropic drugs including quetiapine, clozapine, aripiprazole, and citalopram [36]. The electrochemical transformation products characterized by LC-MS/MS showed strong correlation with metabolites identified in human liver microsomes and patient plasma samples, validating this approach for predicting metabolic pathways while reducing animal testing [36].

Potentiometric Monitoring of Bioavailable Fractions

Potentiometric sensors provide unique advantages in speciation studies, as they respond specifically to the free, uncomplexed form of ionic drugs [32]. This capability has been exploited in environmental and biological monitoring, such as measuring free copper concentrations in seawater and tracking cadmium uptake by plant roots as a function of speciation [32]. For pharmaceutical applications, this feature enables monitoring of the biologically active fraction of ionic drugs, which is particularly valuable for compounds with high protein binding or those prone to complex formation in biological matrices.