Coordination Compounds for Next-Generation OLEDs and Optoelectronics: From Molecular Design to Clinical and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of coordination compounds as advanced materials for OLEDs and optoelectronic devices, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Coordination Compounds for Next-Generation OLEDs and Optoelectronics: From Molecular Design to Clinical and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of coordination compounds as advanced materials for OLEDs and optoelectronic devices, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of metal-organic complexes, including lanthanides and earth-abundant transition metals, and details modern methodological approaches like wet-processing and deep-learning-assisted screening. The content addresses key challenges in device optimization and stability, offering troubleshooting strategies. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of material performance and validates their potential through emerging applications, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical imaging, sensing, and clinical diagnostics.

Unraveling the Core Principles: How Coordination Compounds Power Optoelectronic Devices

Fundamental Working Principles of OLEDs and the Role of Coordination Compounds

Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs) represent a revolutionary display and lighting technology based on the use of organic compounds that emit light in response to an electric current. Unlike conventional LEDs that use inorganic semiconductors, OLEDs utilize carbon-based organic molecules as the emissive material situated between two electrodes [1] [2]. This fundamental difference in material composition enables unique advantages including flexibility, thin form factors, and self-emissive properties without requiring backlighting [2]. The field has evolved significantly since early observations of electroluminescence in organic materials in the 1950s, with the first practical OLED device demonstrated in 1987 by Ching Wan Tang and Steven Van Slyke at Eastman Kodak [1].

The integration of coordination compounds, particularly those containing lanthanide ions, has opened new frontiers in OLED performance and application, especially for near-infrared (NIR) emission [3]. These compounds offer unique photophysical properties derived from their molecular architecture, including sharp emission bands and high quantum efficiencies achievable through molecular design. This application note examines the fundamental working principles of OLEDs within the broader context of coordination compounds for optoelectronics research, providing detailed experimental protocols for device fabrication and characterization.

Fundamental Working Principles

Basic Device Architecture and Operation

A typical OLED device consists of multiple layered components that work in concert to generate light. The core structure includes six primary layers sandwiched between protective barriers [2]:

- Substrate: Bottom layer of glass or plastic that provides structural support

- Anode: Positive terminal, typically made of transparent indium tin oxide (ITO)

- Conductive Layer: Organic molecules (such as polyaniline) that transport "holes" from the anode

- Emissive Layer: Organic molecules (such as polyfluorene) that emit light upon recombination

- Cathode: Negative terminal that injects electrons

- Seal: Top protective layer that prevents oxygen and moisture degradation

The working principle begins when electrical power is applied across the electrodes. The anode withdraws electrons from the conductive layer, creating electron holes, while the cathode injects electrons into the emissive layer. Due to applied voltage, these holes and electrons move toward each other, reuniting at the emissive layer where they form transient electron-hole pairs called excitons [1] [2]. When these excitons decay to their ground state, they release energy in the form of photons through a process called recombination [2]. The specific wavelength and color of emitted light depend on the band gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the organic semiconductor material [1].

Advanced Operational Mechanisms

Beyond basic electron-hole recombination, several quantum mechanical processes govern OLED efficiency. The recombination of electrons and holes produces singlet and triplet excitons in a statistical ratio of 1:3 [1]. Decay from singlet states results in prompt fluorescence, while triplet state decay produces slower phosphorescence [1]. Conventional fluorescent OLEDs only harvest light from singlet excitons, limiting their maximum internal quantum efficiency to 25%. However, through strategic material design including the use of phosphorescent emitters and thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) materials, researchers can achieve emission from both singlet and triplet states, potentially reaching 100% internal quantum efficiency [3].

The "antenna effect" in lanthanide coordination compounds enables efficient energy transfer from the organic ligands to the metal center, resulting in sharp characteristic emission from the lanthanide ions [3]. This effect is particularly valuable for harvesting triplet excitons that would otherwise be lost to non-radiative decay pathways. Proper molecular design must optimize the energy gap between the triplet state of the ligand and the resonant acceptor level of the lanthanide ion to minimize non-radiative relaxation [3].

Coordination Compounds in OLED Applications

Lanthanide Complexes for NIR Emission

Lanthanide coordination compounds have emerged as particularly valuable emitters for specialized OLED applications, especially in the near-infrared region. Compounds containing Nd³⁺, Er³⁺, and Yb³⁺ ions exhibit narrow luminescent bands in the 880-1600 nm spectral range that are valuable for telecommunications and biomedical applications [3]. Neodymium complexes specifically emit at 880, 1060, and 1330 nm, falling within important biological tissue transparency windows [3].

Recent research has focused on fluorinated 1,3-diketonate coordination compounds of Nd³⁺ ions, which demonstrate significantly enhanced performance through strategic molecular design. The replacement of high-frequency oscillating groups (CH and OH) with fluorinated low-frequency oscillating groups suppresses multiphonon relaxation, a major pathway for luminescence quenching [3]. Successive elongation of fluorinated chains in the ligands further enhances lanthanide-centered luminescence efficiency [3].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Neodymium Coordination Compounds for NIR OLEDs

| Compound | Ligand Structure | Emission Wavelengths | PLQY | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd1 Complex | 1-(1,3-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-4,4,4-trifluorobutane-1,3-dionate | 880, 1060, 1330 nm | Up to 1.08% | Balanced volatility and solubility |

| Nd2 Complex | 1-(1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexane-1,3-dionate | 880, 1060, 1330 nm | - | Improved luminescence efficiency |

| Nd3 Complex | 4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,9,9,9-tridecafluoro-1-(1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)nonane-1,3-dionate | 880, 1060, 1330 nm | - | Highest fluorination for minimal quenching |

Material Design Considerations

The molecular architecture of coordination compounds for OLED applications requires careful balancing of multiple properties. The organic ligands must possess several key characteristics:

- Appropriate triplet energy levels that match the resonant acceptor levels of the lanthanide ion

- High volatility or solubility for deposition via thermal evaporation or spin-coating

- Structural stability to withstand device operation conditions

- Charge transport capabilities to facilitate hole and electron injection

The use of 1,3-diketonate ligands with pyrazole moieties and fluorinated chains has proven particularly effective, as these structures facilitate both efficient energy transfer and enhanced luminescence quantum yields [3]. The ancillary ligand, typically 1,10-phenanthroline, further stabilizes the complex and improves charge transport properties [3].

Experimental Protocols

OLED Fabrication Methods

Substrate Preparation Protocol

Cleaning Process:

- Use ITO-coated glass substrates with 12 Ohm/sq resistance

- Clean sequentially by ultrasonication in:

- 15% KOH alcoholic solution (10 minutes)

- Double distilled water (10 minutes)

- Isopropanol (10 minutes)

- Dry with dust-free nitrogen flow

- Perform additional UV-ozone treatment for 15 minutes [3]

Quality Control:

- Verify surface cleanliness through contact angle measurements

- Check sheet resistance with four-point probe measurements

- Inspect for visible defects under optical microscopy

Active Layer Deposition Methods

Two primary methods exist for depositing the emissive layers containing coordination compounds:

Thermal Evaporation Method

- Conduct in high vacuum chamber (<10⁻⁶ Torr)

- Heat source materials in tungsten boats

- Control deposition rate at 0.1-0.3 nm/s using quartz crystal monitor

- Achieve layer thicknesses of 30-100 nm

- Allows higher electroluminescence efficiency [3]

Spin-Coating Method

- Prepare solution of coordination compound in appropriate solvent (DMSO, chloroform, or toluene)

- Filter solution through 0.2 μm PTFE filter to remove particulates

- Dispense solution onto spinning substrate (typically 1000-3000 rpm)

- Bake on hotplate to remove residual solvent (100-150°C for 10-30 minutes)

- More suitable for mass production due to lower cost [3]

Photophysical Characterization Methods

Triplet Energy and Decay Time Measurements

Understanding the excited state dynamics is crucial for optimizing OLED materials. The following protocol enables determination of triplet energies and decay times:

Experimental Setup Components [4]:

- Laser: CryLas FQSS 266-200, triple ND:YAG operating at 266 nm, pulse energy 200 μJ, pulse width 1.5 ns

- Cryostat: Oxford Instruments Optistat DN-V2 with liquid nitrogen cooling

- Spectrograph: Andor Shamrock SR-303i-A

- Camera: Andor iStar DH320T-18F-03 ICCD detector

Measurement Procedure [4]:

- Mount sample in cryostat under vacuum for thermal isolation

- Align laser beam with beam expander for appropriate spot size

- Connect pre-trigger pulse from laser to camera for synchronization

- Set acquisition delays to account for ~72 ns propagation delay

- Acquire spectra using "kinetic series" mode with varying delays

- Use "boxcar" acquisition mode with delay time to reject fluorescence for low phosphorescence samples

- Perform multiple acquisitions and average for improved signal-to-noise ratio

Data Analysis:

- Identify T1 level by assessing intensity at first maximum peak

- Fit mathematical model to time-dependent phosphorescence decay

- Determine triplet-triplet annihilation (TTA) properties from decay curve fitting

- Analyze temperature dependence of decay profiles from 77K to room temperature

Table 2: Key Parameters for Triplet Energy Measurements

| Parameter | Specification | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Wavelength | 266 nm | Higher energy than emission for accurate Stokes shift measurement |

| Pulse Width | 1.5 ns | Sufficiently short to resolve rapid decay processes |

| Detection Range | 350-700 nm | Covers both fluorescence and phosphorescence emission |

| Temperature Range | 77K-300K | Enables study of thermal behavior of excitons |

| Time Resolution | Nanoseconds to seconds | Captures both fast fluorescence and slow phosphorescence |

Electroluminescence Characterization

For complete OLED device characterization:

Current-Voltage-Luminance (J-V-L) Measurements:

- Use source measure unit and calibrated photodiode

- Measure from 0V to operating voltage in 0.1V steps

- Calculate external quantum efficiency (EQE) and current efficiency

Spectral Measurements:

- Use integrating sphere with spectrometer

- Measure electroluminescence spectra at multiple driving voltages

- Determine CIE color coordinates and color rendering index

Lifetime Testing:

- Operate devices at constant current

- Monitor luminance decay over time

- Extract LT50 and LT70 lifetimes (time to 50% and 70% initial luminance)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for OLED Device Fabrication with Coordination Compounds

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hole Injection Materials | PEDOT:PSS (Lumtec LT-PS001) | Facilitates hole injection from anode, improves surface morphology | Lumtec, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Host Materials | Tris(4-carbazoyl-9-ylphenyl)amine (TCTA) | Host matrix for emissive dopants, balanced charge transport | Lumtec, TCI Chemicals |

| Electron Transport Materials | 2,2',2"-(1,3,5-Benzinetriyl)-tris(1-phenyl-1-H-benzimidazole) (TPBi, Lumtec LT-E302) | Electron transport and hole blocking | Lumtec, Ossila |

| Emissive Layer Materials | Fluorinated 1,3-diketonate Nd³⁺ complexes | NIR emission via triplet harvesting | Custom synthesis [3] |

| Cathode Materials | LiF (Lumtec LT-E001)/Al | Electron injection, environmental protection | Lumtec, Kurt J. Lesker |

| Substrates | ITO-coated glass (12 Ohm/sq) | Transparent conductive substrate | Lumtec, Colorado Concept |

| Characterization Tools | Spectroscopic ellipsometers (Horiba Jobin Yvon FF-1000) | Thin film thickness and optical properties | Horiba [5] |

Performance Optimization and Data Analysis

Efficiency Enhancement Strategies

Optimizing OLED performance requires systematic approach to material selection and device architecture:

Exciton Management:

- Incorporate appropriate host-guest energy transfer systems

- Utilize triplet-triplet annihilation (TTA) materials for enhanced efficiency

- Implement graded heterojunctions to improve charge injection balance [1]

Charge Transport Balance:

- Select hole and electron transport materials with balanced mobility

- Incorporate blocking layers to prevent exciton quenching at electrodes

- Optimize layer thickness to reduce operating voltage

Optical Outcoupling Enhancement:

- Use micro-lens arrays to extract trapped waveguide modes

- Implement scattering layers for enhanced light extraction

- Optimize electrode thickness for constructive interference

Data Interpretation Guidelines

When analyzing characterization data from OLED devices:

Photoluminescence Data:

- Compare PLQY values in solution vs. solid state to assess concentration quenching

- Analyze Stokes shift to understand structural relaxation in excited state

- Examine full width at half maximum (FWHM) for color purity assessment

Electroluminescence Data:

- Calculate external quantum efficiency from current efficiency values

- Analyze efficiency roll-off at high current densities to identify loss mechanisms

- Correlate spectral shifts with driving voltage to understand field effects

Transient Decay Data:

- Fit multi-exponential decays to identify different recombination pathways

- Calculate average lifetime weighted by amplitude contributions

- Correlate lifetime changes with temperature to understand thermally-activated processes

The integration of coordination compounds, particularly lanthanide complexes, into OLED architectures continues to expand the capabilities of organic optoelectronics. Through careful molecular design, optimized fabrication protocols, and comprehensive characterization, researchers can harness the unique photophysical properties of these materials for advanced applications in displays, lighting, and specialized NIR emitters.

The antenna effect describes a photophysical process in luminescent coordination compounds where organic ligands act as "antennas," absorbing incident light energy and efficiently transferring it to a central metal ion, which then emits light with its characteristic properties [6]. This mechanism is crucial for enhancing the luminescence of lanthanide (Ln³⁺) ions, which typically suffer from low molar absorption coefficients due to Laporte-forbidden 4f-4f transitions [6]. By coordinating organic ligands with high absorption coefficients to these metal ions, the antenna effect overcomes this intrinsic limitation, resulting in materials that exhibit long luminescence lifetimes, large Stokes shifts, narrow emission spectra, and high photostability [6]. These properties make antenna effect-modulated coordination compounds particularly valuable for advanced optoelectronic applications, including organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and biological sensing platforms.

In the context of OLED technology, the antenna principle extends beyond sensitizing lanthanide ions. Similar energy transfer mechanisms are harnessed in hyperfluorescent OLED systems, where a "sensitizer" molecule (such as a thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) emitter or phosphorescent complex) acts as the energy donor, transferring excitons to a final "emitter" molecule via a process analogous to the antenna effect [7] [8]. This review details the fundamental principles, quantitative performance, experimental methodologies, and key reagents for developing and characterizing antenna effect-based materials for optoelectronic research.

Fundamental Principles and Signaling Pathways

The antenna effect involves a coordinated sequence of photophysical steps between a light-harvesting organic ligand and a metal ion. The generalized signaling pathway can be summarized as follows:

- Photoexcitation: An organic ligand with a high absorption coefficient absorbs an incident photon, promoting it from its ground state (S₀) to a higher-energy singlet excited state (S₁).

- Intersystem Crossing (ISC): The excited singlet state undergoes intersystem crossing to form a triplet excited state (T₁) of the ligand.

- Energy Transfer: The energy from the ligand's triplet state is transferred to the emissive energy level of the metal ion. For lanthanides, this is typically a 4f orbital.

- Luminescence: The metal ion relaxes to its ground state, emitting characteristically narrow-band light.

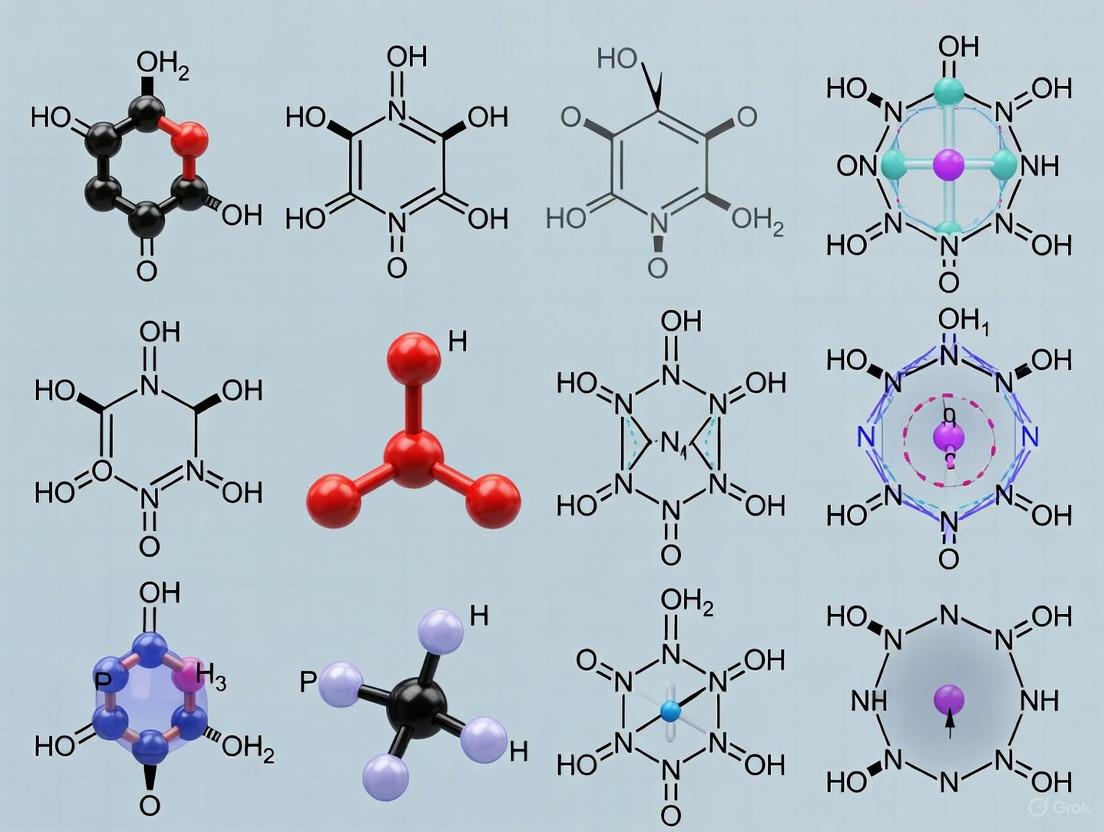

The following diagram illustrates this core energy transfer pathway.

Figure 1: Core signaling pathway of the Antenna Effect, showing the sequential energy transfer from ligand absorption to metal-centered luminescence.

For OLED applications, this principle is adapted into device architectures that separate the functions of charge transport, exciton formation, and light emission. A common strategy involves using a sensitizer layer, such as a phosphorescent Pt(II) complex, which transfers energy to a separate layer of a fluorescent dye via interfacial energy transfer, resulting in highly efficient near-infrared (NIR) emission [7]. The workflow for developing and characterizing such a hyperfluorescent OLED system is detailed below.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for developing hyperfluorescent OLEDs using interfacial energy transfer, from material selection to device performance testing.

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of luminescent materials and devices utilizing the antenna effect is quantified through key photophysical and electroluminescence parameters. The tables below summarize representative data from recent research for lanthanide complexes, OLED devices, and non-lanthanide systems.

Table 1: Performance of Antenna Effect-Modulated Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes (LLCs) in Sensing Applications

| Analyte Detected | Ln³⁺ Ion | Antenna Ligand Type | Application | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthrax Spore Biomarker | Eu³⁺ | Dual-ligand two-dimensional structure | Fluorescence Sensor | Ratiometric detection in solid state | [6] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Eu³⁺ | Gelatinous coordination polymer | Fluorescence Sensor | Ratiometric detection in biological media | [6] |

| Flumequine (Antibiotic) | Eu³⁺ | Covalent Organic Framework (COF) | Fluorescence Sensor | Specific detection via pore restriction & antenna effect | [6] |

| Imidacloprid (Pesticide) | Eu³⁺ | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Sensor | Dual-source signal amplification | [6] |

Table 2: Performance of OLEDs Utilizing Energy Transfer Mechanisms

| Emitter / System Type | Emission Max (nm) | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Key Performance Feature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Hyperfluorescence (BTP-eC9) | 925 | 2.24% (avg 1.94 ± 0.18%) | Record high radiance of 39.97 W sr⁻¹ m² for >900 nm fluorescence OLED | [7] |

| NIR Hyperfluorescence (BTPV-eC9) | 1022 | Reported | Validation of interfacial energy transfer principle at >1000 nm | [7] |

| Blue Multiple Resonance TADF (mCNDB) | 459 | > 23% | Narrow FWHM of 13 nm; maintains ~20% EQE at 1000 cd m⁻² | [8] |

| Green Phosphorescent (NiO:MoO₃-complex HTL) | - | - | 189% increased current efficiency vs. MoO₃-based devices | [9] |

| Blue Phosphorescent (NiO:MoO₃-complex HTL) | - | 17% | Superior to conventional HATCN-based devices | [9] |

Table 3: Performance of Non-Lanthanide Complexes for OLEDs

| Complex / Material | Type | PLQY (%) | Emission Lifetime (μs) | Emission Color | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(II) Complexes | Fluorescent (LC/LLCT) | - | - | Tunable across visible spectrum | [10] |

| Pd(II) Complex Pd1 | TADF | 82 | 2.19 | Orange-Red | [11] |

| Pd(II) Complex Pd2 | TADF | 89 | 0.97 | Orange-Red | [11] |

| OLED with Pd1/Pd2 | TADF-based OLED | Max EQE: 27.5-31.4% | - | - | [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Hyperfluorescent NIR OLED via Interfacial Energy Transfer

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating a bilayer structure of a self-assembled Pt(II) complex donor and a transfer-printed NIR dye acceptor for high-performance NIR OLEDs, based on the work in [7].

Principle: Exploit interfacial energy transfer from a phosphorescent donor to a fluorescent acceptor to achieve efficient NIR electroluminescence, bypassing the need for co-deposition that can disrupt molecular self-assembly.

Materials:

- Donor material: Pt(fprpz)₂ (or similar self-assembling Pt(II) complex)

- Acceptor material: BTP-eC9 (or similar NIR fluorescent dye, e.g., Y11, BTPV-eC9)

- Substrates: Pre-patterned ITO glass substrates

- Organic host and charge transport materials (e.g., CBP, TAPC, TmPyPb)

- Metal electrodes (e.g., LiF, Al)

Procedure:

- Donor Layer Fabrication: a. Prepare a solution of Pt(fprpz)₂ in a suitable solvent (e.g., chlorobenzene). b. Deposit the Pt(fprpz)₂ layer onto a cleaned ITO substrate via spin-coating (e.g., 3000 rpm for 30 s) under inert atmosphere. c. Anneal the film on a hotplate at 80°C for 10 minutes to facilitate self-assembly and remove residual solvent. Confirm film formation and self-assembly via Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM).

Acceptor Layer Transfer-Printing: a. Fabricate a standalone film of the NIR dye (BTP-eC9) on a separate, temporary substrate (e.g., PDMS stamp) via spin-coating. b. Carefully bring the dye film on the stamp into conformal contact with the surface of the pre-formed Pt(fprpz)₂ layer. c. Apply uniform pressure and gently peel away the temporary substrate, leaving the BTP-eC9 layer intact on top of the Pt(fprpz)₂ layer. This non-destructive transfer preserves the self-assembled structure of both layers.

OLED Device Completion: a. Load the bilayer substrate into a thermal evaporation chamber. b. Sequentially deposit the remaining organic layers (e.g., hole transport layer, electron transport layer) through a shadow mask under high vacuum (< 5 × 10⁻⁶ Torr). c. Deposit the cathode (e.g., 1 nm LiF followed by 100 nm Al) through the shadow mask. d. Encapsulate the completed devices immediately using a glass lid and UV-curable epoxy in a nitrogen glovebox to prevent degradation.

Characterization:

- Time-resolved Photoluminescence (TrPL): Use a femtosecond laser (e.g., 505 nm excitation) to measure the donor photoluminescence lifetime in the single layer and the bilayer. A significant reduction in the donor lifetime in the bilayer structure confirms efficient energy transfer.

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure the PLQY of the bilayer film using an integrating sphere.

- OLED Performance: Measure current-voltage-luminance (J-V-L) characteristics, external quantum efficiency (EQE), and electroluminescence (EL) spectrum of the completed devices.

Protocol: Synthesis and Characterization of a Zn(II) Complex for Fluorescent OLEDs

This protocol describes the general synthesis and evaluation of Zn-based complexes as eco-friendly emitters, based on the review in [10].

Principle: Utilize ligand-centered (LC) and ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (LLCT) transitions in Zn(II) complexes to achieve tunable, efficient fluorescence without heavy metals.

Materials:

- Metal salt: Zn(II) salt (e.g., Zn(OAc)₂, ZnCl₂)

- Organic ligands: Selected based on desired emission color (e.g., β-diketones, aromatic N-donor ligands)

- Solvents: High-purity methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, dichloromethane

- Base: e.g., triethylamine or sodium methoxide

Procedure:

- Synthesis: a. Dissolve the organic ligand (1.0 equiv) in a suitable warm solvent (e.g., 20 mL methanol) under nitrogen atmosphere. b. In a separate flask, dissolve the Zn(II) salt (0.5 equiv for a bis-complex) in a minimal amount of the same solvent. c. Add the metal salt solution dropwise to the ligand solution with vigorous stirring. d. Add a base (e.g., 1-2 equiv of triethylamine) to deprotonate the ligand and promote complexation. e. Heat the reaction mixture under reflux for 4-12 hours. f. Cool the solution slowly to room temperature, then further to 4°C to promote crystallization. g. Collect the precipitate by vacuum filtration and wash with cold solvent. h. Purify the crude product by recrystallization.

- Characterization: a. Structural Analysis: Confirm complex formation and structure via ( ^1 \text{H} ) and ( ^13\text{C} ) NMR spectroscopy, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and elemental analysis. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction is ideal for definitive structural confirmation. b. Thermal Analysis: Perform Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to determine decomposition temperature (T_d) and assess thermal stability. c. Photophysical Analysis: i. Record UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra in solution and solid-state (doped film). ii. Measure the Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) using an integrating sphere. iii. Perform transient PL decay measurements to obtain the fluorescence lifetime.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antenna Effect and OLED Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-diketone Ligands | Antenna ligands for Ln³⁺ complexes | High molar absorptivity, efficient energy transfer to Ln³⁺ ions | Standard for sensitizing Eu³⁺ and Tb³⁺ [6] |

| Aromatic Ligands | Antenna ligands for Ln³⁺ complexes | Rigid structure, tunable energy levels via substituents | Used in LLCs for biosensing [6] |

| Macrocyclic Ligands | Antenna ligands for Ln³⁺ complexes | Form highly stable and well-defined complexes with Ln³⁺ | e.g., cyclen derivatives [6] |

| Pt(fprpz)₂ | Phosphorescent energy donor in NIR OLEDs | High PLQY (~80%), self-assembling, MMLCT emission ~740 nm [7] | Key for interfacial energy transfer [7] |

| BTP-eC9 | NIR fluorescent energy acceptor in OLEDs | Strong absorption overlapping donor emission, emits at ~940 nm in film [7] | Final emitter in hyperfluorescent system [7] |

| CzDB / mCNDB | Multiple Resonance (MR) TADF emitter | Narrowband blue emission; mCNDB features deeper HOMO for reduced charge trapping [8] | Blue emitter for high-color-purity displays [8] |

| NiO:MoO₃-complex | Charge injection layer for OLEDs | Tunable work function (4.47–6.34 eV), enhances conductivity and charge balance [9] | Hole injection layer for high-efficiency OLEDs [9] |

| Pd(II) Complexes (Pd1, Pd2) | TADF emitters for OLEDs | Metal-perturbed ILCT state, high PLQY, short lifetime, high operational stability [11] | Efficient and stable alternative to Ir/Pt complexes [11] |

Trivalent lanthanide ions (Ln³⁺), particularly Neodymium (Nd³⁺), Erbium (Er³⁺), and Ytterbium (Yb³⁺), are pivotal in advancing modern optoelectronics and biomedicine due to their unique photophysical properties [12]. Their emission originates from well-shielded 4f-4f electronic transitions, resulting in characteristically sharp, narrow-band emissions in the near-infrared (NIR) region, which are nearly independent of the surrounding chemical environment [13] [14] [12]. These transitions lead to high emission color purity, long excited-state lifetimes, and large Stokes shifts, making these ions ideal for applications requiring high spectral precision [15] [12].

The integration of these lanthanide complexes into a broader thesis on coordination compounds for OLEDs and optoelectronics highlights their dual significance. For telecommunications, NIR emissions from Er³⁺ (around 1550 nm) align perfectly with the low-loss transmission window of silica optical fibers [14]. In biomedicine, the deep tissue penetration and minimal autofluorescence offered by NIR light from Nd³⁺, Er³⁺, and Yb³⁺ complexes are exploited for high-contrast bioimaging and sensing [16] [12]. This application note details the core photophysical properties, provides experimental protocols for their study, and outlines their specific applications, serving as a practical guide for researchers and scientists in the field.

Photophysical Properties & Quantitative Data

The utility of Nd³⁺, Er³⁺, and Yb³⁺ complexes stems from their distinct energy level structures. The antenna effect is critical for their function, as Ln³⁺ ions have low molar absorptivity; organic ligands absorb light efficiently and transfer the energy to the lanthanide ion, which then emits its characteristic light [13] [12]. The following table summarizes the key emission properties of these ions.

Table 1: Characteristic Near-Infrared (NIR) Emission Properties of Select Lanthanide Ions

| Lanthanide Ion | Main Emission Wavelength (nm) | Transition | Key Application Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nd³⁺ (Neodymium) | ~900, ~1060, ~1330 | ⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴I₉/₂, ⁴I₁₁/₂, ⁴I₁₃/₂ | Bioimaging, lasers [14] [12] |

| Er³⁺ (Erbium) | ~1550 | ⁴I₁₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₅/₂ | Telecommunications, bioimaging [14] [12] |

| Yb³⁺ (Ytterbium) | ~980 | ²F₅/₂ → ²F₇/₂ | Sensitizer for upconversion, bioimaging [14] [12] |

The emission efficiency is governed by the efficiency of the ligand-to-metal energy transfer process. Recent studies on chiral Schiff base ligands, such as (R,R)-dnsalcd, demonstrate that the coordination geometry and intramolecular interactions (e.g., π-π stacking) can significantly influence the antenna effect and the resulting luminescence intensity [14]. Furthermore, the design of the ligand's triplet state (T₁) is crucial; its energy must be optimally matched to the resonance level of the lanthanide ion to enable efficient sensitization while minimizing back-energy transfer, which causes quenching [17].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Recent Lanthanide Complexes in Optoelectronic Devices

| Complex / Material System | Quantum Yield / EQE | Emission Lifetime | Key Finding/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu(dbm)₃SDZP | EQE: 6.7% | Not Specified | High-efficiency OLED via Se-modified ligand [18] |

| NaGdF₄:Tb@CzPPOA | PLQY: 44.3% (sol.) | Prolonged vs. ligand-free | Efficient electroluminescence via ligand engineering [15] |

| Yb(tpOp)₃ | Not Specified | 20 μs | Model for long-lived NIR emission [14] |

Application Note: Telecommunications

The ~1550 nm emission of Er³⁺ is the international standard for fiber-optic communications because it corresponds to the wavelength of minimum attenuation and dispersion in silica fibers [14]. Research focuses on developing erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs) and organic molecular complexes that can be integrated into planar lightwave circuits.

Experimental Protocol: Measuring NIR Photoluminescence in Solution

This protocol is adapted from studies of mononuclear Ln³⁺ complexes to characterize their emissive properties for telecommunications [14].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Lanthanide Salt: Er(NO₃)₃·xH₂O or ErCl₃·xH₂O.

- Organic Ligand: e.g., (R,R)-H₂dnsalcd or tetraphenyl imidodiphosphonate (HtpOp) [14].

- Base: Triethylamine (TEA), used to deprotonate the ligand for coordination.

- Solvents: Anhydrous/degassed 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME), methanol, acetonitrile, or 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF).

Procedure:

- Complex Synthesis (in-situ): a. Dissolve the organic ligand (e.g., 0.136 mmol (R,R)-H₂dnsalcd) in 5 mL of DME. b. Add triethylamine (2 equivalents, 0.272 mmol) to the solution and stir for 15 minutes to form the deprotonated species. c. In a separate vial, dissolve the Er³⁺ salt (e.g., 0.068 mmol) in 2 mL of methanol. d. Add the Er³⁺ solution dropwise to the ligand solution with stirring. A color change or precipitate may form. e. Stir the mixture for an additional 10-60 minutes. For crystal growth, use slow diethyl ether vapor diffusion.

Sample Preparation: Transfer the reaction mixture or a purified, isolated solid into a quartz cuvette. Dilute with a suitable anhydrous solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) to an optical density suitable for measurement (e.g., <0.1 at the excitation wavelength).

Spectroscopic Measurement: a. Use a spectrophotometer equipped with a NIR-sensitive detector (e.g., a liquid nitrogen-cooled InGaAs photodiode array). b. Set the excitation wavelength to the ligand's maximum absorption (e.g., 352 nm for (R,R)-dnsalcd-based complexes) [14]. c. Record the emission spectrum in the NIR range (e.g., 1450-1650 nm for Er³⁺). d. For lifetime measurement, use a pulsed laser source (e.g., Nd:YAG) and a digital oscilloscope to record the decay of the emission at 1550 nm. Fit the decay curve to an exponential function to determine the lifetime.

Diagram 1: The "Antenna Effect" energy transfer pathway from ligand to Er³⁺ ion, leading to NIR emission for telecommunications.

Application Note: Biomedicine

NIR-emitting lanthanide complexes are invaluable tools in biomedicine. Their deep tissue penetration, minimal photodamage, and absence of autofluorescence from biological samples enable high-sensitivity imaging and sensing [16] [12]. Nd³⁺ and Yb³⁺ are particularly useful for these applications.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Hydration Number and Stability in Aqueous Media

A critical parameter for biological application is the complex's stability in aqueous media. The number of water molecules directly coordinated to the Ln³⁺ ion (hydration number, q) can be determined using luminescence lifetime measurements, as water molecules quench the excited state via O-H vibrators [13].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Lanthanide Complex: Purified solid of the Nd³⁺, Er³⁺, or Yb³⁺ complex.

- Solvents: High-purity H₂O and D₂O.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: a. Prepare two solutions of the complex in H₂O and D₂O with identical concentrations (e.g., 0.1 mM). Ensure the complex is sufficiently soluble. b. Use quartz or specialized NIR cuvettes for measurement.

Lifetime Measurement: a. Using a pulsed laser and NIR detector, measure the luminescence lifetime (τ) of the complex in both H₂O and D₂O. For Nd³⁺, the measurement is typically taken from the ⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₃/₂ transition. b. Repeat the measurement 3-5 times to obtain an average value.

Data Analysis: a. The hydration number (q) can be estimated using the formula derived from Horrocks' method for NIR lanthanides (simplified): ( q = A ( τ{H₂O}^{-1} - τ{D₂O}^{-1} ) ) where A is a proportionality constant specific to the lanthanide ion (e.g., ~0.25 ms for Nd³⁺), and τ({}{H₂O}) and τ({}{D₂O}) are the measured lifetimes in H₂O and D₂O, respectively [13]. b. A lower q value indicates better shielding of the Ln³⁺ ion from the aqueous environment, suggesting higher stability and reduced luminescence quenching, which is desirable for bio-applications.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for determining the hydration state and aqueous stability of NIR-emitting lanthanide complexes for biomedical use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Developing NIR-Emitting Lanthanide Complexes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Hexafluoroacetylacetonate (hfa) | Anionic β-diketonate ligand; acts as a strong "antenna" and improves volatility/thermal stability [17]. | Used in [TbNd(hfa)₆(dptp)₂] for its triplet state energy [17]. |

| Triphenylene Bridging Ligands (e.g., dptp) | Connects metal centers in polynuclear complexes; its triplet level can be tuned for energy transfer [17]. | Facilitates energy escape pathway in dinuclear thermometer complexes [17]. |

| Chiral Schiff Base Ligands (e.g., (R,R)-H₂dnsalcd) | Provides a chiral coordination environment; can induce Circularly Polarized Luminescence (CPL) and strong antenna effect [14]. | Used in (teaH)[Ln((R,R)-dnsalcd)₂] for NIR emission and chiroptical activity [14]. |

| Selenium-modified Phenanthroline (e.g., SDZP) | Neutral ancillary ligand; heavy atom effect can enhance intersystem crossing, improving sensitization efficiency [18]. | Co-ligand in Eu(dbm)₃SDZP for high-efficiency OLEDs [18]. |

| Carbazole-Phosphine Oxide Ligands (e.g., CzPPOA) | Functionalized coating for nanocrystals; acts as an exciton harvester and charge transport medium for electroluminescence [15]. | Used in NaGdF₄:Tb@CzPPOA nanohybrids for efficient EL [15]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (D₂O) | Used in photophysical studies to measure luminescence lifetimes without O-H vibrational quenching [13]. | Critical for determining the hydration number (q) of complexes in aqueous solution [13]. |

The field of organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and light-emitting electrochemical cells (LECs) faces a critical sustainability challenge. Current high-performance devices predominantly rely on phosphorescent emitters based on scarce and expensive metals like iridium and platinum. Their low abundance on Earth creates supply chain risks and conflicts with the principles of sustainable technology development [19]. Consequently, research has pivoted toward earth-abundant transition metal complexes, with copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) emerging as the most promising candidates. These metals offer a compelling combination of environmental safety, cost-effectiveness, and tunable optoelectronic properties [10]. This application note details the synthesis, properties, and device integration of Cu and Zn complexes, providing essential protocols for researchers developing next-generation sustainable optoelectronics.

Material Properties and Cost-Benefit Analysis

Abundance and Precursor Economics

The core advantage of Zn and Cu lies in their high crustal abundance and the low cost of their precursor salts, which directly translates to reduced material costs for large-scale production.

Table 1: Abundance and Cost of Key Metal Precursors [19]

| Metal | Abundance in Earth's Crust (ppm) | Common Synthesis Precursor | Approximate Precursor Cost (euro/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iridium (Ir) | 0.000037 | IrCl₃·xH₂O | 58,000 |

| Copper (Cu) | 27 | CuI | 117 |

| [Cu(CH₃CN)₄][PF₆] | 5,000 | ||

| Zinc (Zn) | 72 | Zn(OAc)₂·2H₂O | 27 |

| Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | 26 |

Photophysical Properties and Emission Mechanisms

Zinc(II) and Copper(I) complexes operate via distinct photophysical mechanisms, which dictate their application in devices:

- Zinc (Zn(II)) Complexes: Typically, Zn²⁺ is a closed-shell d¹⁰ ion. Its complexes are usually fluorescent and do not exhibit strong spin-orbit coupling. Their emission primarily stems from ligand-centered (LC) or ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (LLCT) transitions. The theoretical internal quantum efficiency (IQE) cap for these fluorescent materials is 25%, but their color can be precisely tuned through sophisticated ligand design [10].

- Copper (Cu(I)) Complexes: These are highly attractive due to their ability to exhibit thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF). Their emission is based on metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transitions. A key challenge is their tendency to undergo excited-state distortion (flattening), which opens non-radiative decay pathways. This can be mitigated through careful ligand design to create a more rigid coordination environment [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This protocol describes the synthesis of a blue-emitting Zn complex with a pyrazolone-based azomethine ligand, suitable for OLED applications.

Objective: To synthesize and characterize [ZnL·H₂O], a complex for blue electroluminescence.

Reagents & Materials:

- 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-formylpyrazol-5-one (ligand precursor)

- Propane-1,3-diamine

- Zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(OAc)₂·2H₂O)

- Methanol, sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

Synthetic Procedure:

- Ligand (H₂L) Synthesis: React 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-formylpyrazol-5-one with propane-1,3-diamine in a 2:1 molar ratio in methanol. Stir the mixture at room temperature for 4-6 hours. Recover the product by recrystallization from methanol.

- Complex ([ZnL·H₂O]) Synthesis: Dissolve the synthesized H₂L ligand in methanol. Add an aqueous solution of NaOH (2 equivalents) to deprotonate the ligand. Add a methanolic solution of Zn(OAc)₂·2H₂O (1 equivalent) dropwise with stirring. Maintain the reaction at 60°C for 2 hours. Cool the mixture to room temperature to allow for the formation of needle-like crystals.

- Dehydration: The coordinated water molecule can be removed by heating the complex to 192-258°C under an inert atmosphere, yielding the anhydrous complex [ZnL] with significantly enhanced photoluminescence quantum yield (QY) [20].

Characterization & Analysis:

- Structural: Confirm molecular structure via X-ray Diffraction (XRD), ¹H NMR, and IR spectroscopy.

- Thermal: Perform Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to determine stability up to 192°C and dehydration characteristics.

- Photophysical: Record UV-Vis absorption (bands at ~265 nm, ~292 nm, and a broad 330-400 nm MLCT band) and photoluminescence (PL) spectra in the solid state. The complex exhibits a blue emission maximum at 416 nm. Determine the solid-state PL quantum yield.

Device Fabrication (OLED):

- Prepare a thin film of the [ZnL] complex as the emissive layer on a pre-cleaned ITO substrate.

- The device exhibits blue emission with a reported maximum brightness of up to 5300 Cd/A [20].

Diagram Title: Zinc Complex Synthesis and Device Workflow

This protocol outlines the fabrication of an LEC using a TADF-active Cu(I) complex as the emitter.

Objective: To fabricate a thin-film LEC using a Cu(I) complex as the single-component emitter.

Reagents & Materials:

- Cu(I) complex (e.g., complex 1, 2, or 3 from [19], with N^N and P^P ligands)

- Ionic electrolyte (e.g., [BMIM][PF₆])

- Solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or chlorobenzene)

- ITO-coated glass substrate

- Metal cathode (e.g., Al)

Device Fabrication Procedure:

- Emissive Layer Ink Preparation: Dissolve the Cu(I) complex and the ionic electrolyte in a molar ratio of ~100:1 in an anhydrous, polar organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) to form a homogeneous ink. Typical concentrations are 10-20 mg/mL.

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the ITO-coated glass substrate thoroughly with solvents and oxygen plasma treatment to ensure a clean, hydrophilic surface.

- Film Deposition: Deposit the emissive layer onto the ITO substrate using a solution-based technique such as spin-coating or inkjet printing. Spin-coating is typically performed at 1500-3000 rpm for 30-60 seconds.

- Film Annealing: Anneal the deposited film on a hotplate at 50-70°C for 15-30 minutes to remove residual solvent.

- Cathode Deposition: Thermally evaporate a metal cathode (e.g., Aluminum, 100 nm) onto the emissive layer under high vacuum conditions.

Device Characterization:

- Electroluminescence (EL): Measure the emission spectrum, maximum brightness (in cd/m²), and CIE coordinates.

- Efficiency: Calculate the external quantum efficiency (EQE) and power efficiency (in lm/W).

- Lifetime: Determine the operational half-lifetime (t₁/₂) at a constant current density.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Earth-Abundant Metal Complexes in Devices

| Complex | Metal | Emission Color | Emission Max (nm) | PLQY | Device Performance | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex 1 [19] | Cu(I) | Blue | 497 | 86% | LEC: 22.2 cd m⁻², t₁/₂ = 16.5 min | Giobbio et al., 2025 |

| Complex 2 [19] | Cu(I) | Blue | 470 | 42% | LEC: 205 cd m⁻², EQE = 0.11% | Giobbio et al., 2025 |

| Complex 3 [19] | Cu(I) | Red | 675 | 5.6% | LEC: Irradiance = 129.8 μW cm⁻² | Giobbio et al., 2025 |

| [ZnL] [20] | Zn(II) | Blue | 416 | 55.5%* | OLED: Brightness = 5300 Cd/A | MDPI, 2025 |

*Quantum yield after dehydration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Emitter Synthesis and Device Fabrication

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Zn(OAc)₂·2H₂O | Inexpensive precursor for Zn(II) complex synthesis. | Cost-effective (~27 €/mol); easy to handle. [19] |

| CuI | Common precursor for Cu(I) complex synthesis. | Low cost (~117 €/mol); air-stable. [19] |

| N^N Bidentate Ligands (e.g., bipyridine, phenanthroline derivatives) | Key ligands for constructing Cu(I) and Zn(II) complexes. | Critical for controlling MLCT energy and color tuning. |

| P^P Bidentate Ligands (e.g., phosphines) | Bulky ligands for Cu(I) complexes to suppress non-radiative decay. | Prevents flattening distortion in the excited state. [19] |

| Schiff Base Ligands | Versatile chelating ligands for Zn(II) complexes. | Pyrazolone-based ligands enable bright blue emission. [20] |

| Ionic Electrolytes (e.g., [BMIM][PF₆]) | Essential component for LEC operation. | Enables ion migration and in-situ p-n junction formation. |

| ITO-coated Glass | Transparent anode substrate for OLED/LEC devices. | Requires rigorous cleaning and plasma treatment. |

Pathways and Operational Principles

Understanding the charge transfer mechanisms is vital for molecular design.

Diagram Title: Zn and Cu Complex Emission Mechanisms

Earth-abundant transition metals like Zinc and Copper present a viable and sustainable pathway for the future of optoelectronics. While Zn(II) complexes offer stability and straightforward tuning for blue emission, Cu(I) complexes hold immense promise due to their TADF activity, which allows for high theoretical efficiencies. Current research continues to address challenges such as the operational lifetime of Cu(I)-based LECs and the pursuit of deeper blue and efficient red emission. The experimental protocols and data summarized in this note provide a foundational toolkit for researchers to advance the development of cost-effective and environmentally friendly lighting and display technologies.

In the pursuit of advanced optoelectronic devices, such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), the photophysical properties of the active materials are paramount. For coordination compounds, which are central to a broad thesis on OLED and optoelectronics research, three properties are particularly critical: the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), the energy levels of the frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO), and the efficient harvesting of triplet excitons. These properties collectively govern the efficiency, color, and overall performance of light-emitting devices [21]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the characterization and optimization of these key properties, framed within the context of developing coordination compounds for next-generation optoelectronics.

Core Property 1: Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Definition and Significance in Coordination Compounds

The Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) is a dimensionless parameter that defines the efficiency of a luminescent material to convert absorbed photons into emitted photons. It is a ratio of the number of photons emitted to the number of photons absorbed. For coordination compounds used in OLEDs, a high PLQY is essential for achieving high device efficiency, as it directly influences the internal and external quantum efficiency of the device [22]. In lanthanide-based NIR emitters, for instance, PLQY is strongly influenced by the energy gap between the triplet state of the ligand and the resonant acceptor level of the Ln³⁺ ion, as well as the suppression of non-radiative relaxation pathways caused by high-frequency oscillators like C-H and O-H bonds in the coordination sphere [3].

Quantitative Data from Recent Studies

Table 1: Reported PLQY Values for Various Coordination Compounds in OLED Applications.

| Material Class | Specific Compound | PLQY Value | Application/Note | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-Emitting Lanthanide Complex | Fluorinated 1,3-diketonate Nd³⁺ complex | Up to 1.08% | NIR OLED; suppression of non-radiative decay | [3] |

| Zinc(II) Heteroligand Complex | ZnL23 in PFO matrix | Not explicitly stated | Solution-processed OLED; EQE up to 1.84% | [23] |

| Multi-Resonance TADF (MR-TADF) | Various (ML-predicted) | High PLQY predicted | Blue OLEDs; high color purity | [22] |

Experimental Protocol for PLQY Measurement

Protocol Title: Absolute PLQY Measurement of Solid-State Coordination Compound Films using an Integrating Sphere.

Principle: This method involves placing the sample inside an integrating sphere to capture all emitted light, allowing for an absolute measurement without the need for a reference standard.

Materials and Reagents:

- Spectrofluorometer: Horiba JobinYvon Fluorolog QM or equivalent.

- Integrating Sphere: Attachment for the spectrofluorometer.

- Sample Substrates: Quartz cells for solutions [3] or prepared thin films on suitable substrates (e.g., glass, silicon).

- Reference Sample: A non-fluorescent standard (e.g., Spectralon) for sphere calibration.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a thin, uniform film of the coordination compound on a substrate using a suitable technique (e.g., spin-coating, thermal evaporation). Ensure the film is free from pinholes and excessive scattering.

- System Setup: Install the integrating sphere onto the spectrofluorometer. Follow the manufacturer's instructions for alignment and calibration.

- Background Measurement: Place a blank substrate identical to the one used for the sample into the integrating sphere. Acquire an emission spectrum with the excitation wavelength (e.g., 350 nm).

- Sample Measurement: Carefully replace the blank substrate with the prepared sample film at the center of the sphere. Acquire the emission spectrum using the same excitation parameters.

- Data Analysis: The PLQY (Φ) is calculated from the acquired spectra using the software provided with the instrument, typically based on the following equation: Φ = (Isample - Iblank) / (Eblank - Esample) where I is the integrated intensity of the emitted light and E is the integrated intensity of the excitation light scattered by the sample or blank.

Core Property 2: HOMO-LUMO Energy Levels

Definition and Role in Device Performance

The Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) are the frontier orbitals that dictate the charge injection and transport properties of a semiconductor material. In OLEDs, the alignment of these energy levels between adjacent layers is critical for minimizing charge injection barriers, facilitating efficient recombination, and achieving low operating voltages [24] [21]. For coordination compounds, tuning the HOMO-LUMO levels through ligand design is a fundamental strategy for optimizing device performance.

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Table 2: Experimentally Determined HOMO and LUMO Energy Levels for OLED Materials.

| Material | HOMO Level (eV) | LUMO Level (eV) | HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) | Measurement Technique | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical OLED Materials (e.g., TCTA, TPBi) | -5.0 to -6.0 | -2.0 to -3.0 | ~3.0 | Cyclic Voltammetry (Solution) | [24] |

| Pyrazole-substituted 1,3-diketonate Nd³⁺ complexes | Data not explicitly listed but determined via CV | Data not explicitly listed but determined via CV | Data not explicitly listed but determined via CV | Cyclic Voltammetry | [3] |

| Zinc(II) heteroligand complexes | Data not explicitly listed but calculated | Data not explicitly listed but calculated | Data not explicitly listed but calculated | DFT Calculations | [23] |

Experimental Protocol for HOMO-LUMO Level Determination

Protocol Title: Determination of HOMO and LUMO Energy Levels using Cyclic Voltammetry in Solution.

Principle: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) measures the oxidation and reduction potentials of a material. These potentials can be correlated to the HOMO and LUMO energy levels, respectively, using a known reference (e.g., ferrocene/ferrocenium, Fc/Fc⁺) and converting to the vacuum energy scale [24].

Materials and Reagents:

- Potentiostat: IPC-Pro potentiostat or equivalent.

- Electrochemical Cell: Three-electrode setup.

- Working Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode.

- Auxiliary Electrode: Platinum grid electrode.

- Reference Electrode: Saturated calomel electrode (SCE) or Ag/Ag⁺.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate (TBABF₄) in anhydrous acetonitrile.

- Analyte: The coordination compound of interest, dissolved in the electrolyte solution.

- Internal Standard: Ferrocene (Fc), highly purified.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the supporting electrolyte (0.1 M TBABF₄) in anhydrous acetonitrile. Add the analyte (coordination compound) to a concentration of approximately 1 mM.

- System Setup: Assemble the electrochemical cell with the three electrodes. Purge the solution with an inert gas (e.g., argon) for at least 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Initial Scan: Record a cyclic voltammogram of the analyte solution over a suitable potential range (e.g., -2.0 V to +1.5 V vs. SCE) at a scan rate of 0.1 V/s.

- Internal Standard Addition: Add a small amount of ferrocene (Fc) directly to the solution to act as an internal standard. Record a new cyclic voltammogram under identical conditions.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the half-wave potentials for the oxidation (E1/2,ox) and reduction (E1/2,red) of the analyte.

- Identify the half-wave potential of the Fc/Fc⁺ couple (E1/2,Fc).

- Convert potentials to the vacuum scale using the formula: HOMO (eV) = - ( E1/2,ox (vs. Fc/Fc⁺) + 4.8 ) LUMO (eV) = - ( E1/2,red (vs. Fc/Fc⁺) + 4.8 )

- The electrochemical gap is Egap,CV = LUMO - HOMO.

Core Property 3: Triplet Harvesting

Mechanisms and Importance

Triplet harvesting refers to the process of utilizing non-emissive triplet excitons for light emission, which is crucial for breaking the 25% internal quantum efficiency limit of fluorescent OLEDs. For coordination compounds, this is primarily achieved through two mechanisms:

- Phosphorescence: In heavy metal complexes (e.g., Pt, Ir), strong spin-orbit coupling enhances intersystem crossing (ISC), allowing radiative decay from the triplet state (T₁) to the ground state (S₀) [25] [26].

- Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (TADF): In purely organic or light metal complexes, a small energy gap (ΔEST) between the singlet (S₁) and triplet (T₁) states enables reverse intersystem crossing (RISC), converting triplet excitons back to singlets which then emit light [25].

- Triplet-Triplet Annihilation (TTA): Two triplet excitons interact to form one higher-energy singlet exciton [25] [27].

Key Findings and Performance Data

Table 3: Triplet Harvesting Mechanisms and Their Performance in Optoelectronic Devices.

| Mechanism | Material Example | Key Performance Metric | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorescence | Platinum(II) complexes | High efficiency in solution-processed OLEDs | [26] |

| TADF | Multi-resonance (MR) emitters | High color purity and theoretical 100% IQE | [25] [22] |

| TTA | Blue fluorescent OLED with fast TTA channels | Maximum EQE of 11.4% | [27] |

| "Antenna-effect" | 1,3-diketonate Ln³⁺ complexes (e.g., Nd³⁺) | Triplet harvesting via energy transfer to lanthanide ion | [3] |

Experimental Workflow for Triplet Harvesting Material Study

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for developing and characterizing triplet-harvesting coordination compounds, from synthesis to device integration.

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing triplet-harvesting materials, showing parallel theory and experiment paths.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials for OLED Coordination Compound Research.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Hole-injection layer; improves anode contact and film uniformity. | Used in both NIR Nd³⁺-based [3] and Zn(II)-based [23] OLED architectures. |

| TPBi | Electron-transport material; facilitates electron injection and blocks holes. | Employed as an electron transport material in NIR OLEDs [3] and with Zn(II) emitters [23]. |

| TCTA | Host material with high triplet energy; confines excitons and prevents quenching. | Used as a host material in NIR OLED structures [3]. |

| Poly(9,9-di-n-octylfluorenyl-2,7-diyl) (PFO) | Conjugated polymer host for blue emission; enables FRET to guest emitters. | Served as host for Zn(II) compounds in solution-processed OLEDs [23]. |

| 1,3-diketone ligands | Act as "antenna" ligands; absorb light and transfer energy to the lanthanide ion. | Fluorinated derivatives used to synthesize NIR-emitting Nd³⁺ complexes [3]. |

| 1,10-phenanthroline | Ancillary ligand; saturates coordination sphere and improves complex stability/volatility. | Used in NIR-emitting Nd³⁺ complexes to complete coordination [3]. |

The strategic characterization and optimization of PLQY, HOMO-LUMO levels, and triplet harvesting mechanisms form the cornerstone of developing high-performance coordination compounds for OLEDs and other optoelectronic devices. The application notes and detailed protocols provided here offer a framework for researchers to systematically evaluate and improve these key properties. As the field advances, the integration of synthetic chemistry, photophysical analysis, and device engineering—aided by emerging tools like machine learning [22]—will continue to drive the discovery of novel materials that bridge the gap between efficiency, stability, and color purity.

Synthesis to Systems: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Optoelectronics and Biomedicine

The fabrication of high-performance organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and other optoelectronic devices critically depends on the deposition technique employed to form thin-film functional layers. The choice between thermal evaporation and solution-based processing methods like spin-coating represents a fundamental technological branch point that influences device architecture, material selection, performance parameters, and ultimately commercial viability. Within the broader thesis context of coordination compounds for advanced optoelectronics, understanding these deposition methodologies becomes paramount, as the technique must be compatible with the often delicate molecular structures of emissive complexes while achieving the morphological control necessary for optimal device operation.

The deposition method directly impacts critical device characteristics including interfacial sharpness, film uniformity, morphological stability, and charge transport properties. For coordination compounds and complex organometallic systems used in OLED and photovoltaic applications, the thermal stability, solubility characteristics, and tendency for crystallization often dictate which deposition approach is most suitable. This application note provides a structured comparison between vacuum thermal evaporation and spin-coating/wet-processing techniques, with specific consideration for their application in devices utilizing coordination compounds.

Technical Comparison of Deposition Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Thermal Evaporation operates on physical vapor deposition principles where source materials are heated under high vacuum conditions (typically ≤10⁻⁶ Torr) to their sublimation point, forming a vapor phase that condenses onto substrates to create thin films. This line-of-sight process allows for precise thickness control through quartz crystal monitoring and enables sequential deposition of multiple layers without solvent incompatibility issues. The technique is particularly suitable for materials with well-defined vaporization temperatures and low molecular weights, though recent advances have extended its application to larger functional molecules.

Spin-Coating and Wet-Processing relies on solution-phase deposition where a precursor solution is dispensed onto a substrate that is subsequently rotated at high speeds (typically 1000-6000 RPM). Centrifugal force spreads the material uniformly while solvent evaporation promotes film formation. This process involves complex fluid dynamics with distinct stages: deposition, spin-up, spin-off, and evaporation-dominated drying. The final film morphology depends on multiple factors including solution viscosity, evaporation rate, surface tension, and substrate interactions, often requiring careful optimization of processing conditions and solvent mixtures.

Quantitative Comparison of Technical Parameters

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Thermal Evaporation and Spin-Coating Techniques

| Parameter | Thermal Evaporation | Spin-Coating |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Thickness Range | 10 nm - 1 μm | 50 nm - 10 μm |

| Thickness Uniformity | ±1-3% across substrate | ±2-5% within wafer |

| Typical Deposition Rate | 0.1-5 Å/s | 1-100 μm/s (initial) |

| Material Utilization Efficiency | 5-20% (point source) | 90-98% (wasted) |

| Solvent/Additive Requirements | None | Required (often toxic) |

| Vacuum Requirements | High vacuum (10⁻⁶ Torr) | Ambient or controlled atmosphere |

| Multilayer Capability | Excellent (no solvent damage) | Poor (requires orthogonal solvents) |

| Throughput | Moderate to low | High |

| Capital Equipment Cost | High ($100k-$1M+) | Low to moderate ($10k-$100k) |

| Operational Cost | Moderate (vacuum maintenance) | Low (consumables) |

| Scalability to Large Areas | Challenging | Moderate |

| Film Doping Precision | Excellent (co-evaporation) | Good (pre-mixed) |

| Environmental Sensitivity | Minimal (encapsulated) | High (oxygen/moisture) |

Application-Specific Considerations for Coordination Compounds

Coordination compounds present unique challenges for thin-film deposition due to their complex molecular structures, thermal sensitivity, and tendency for concentration quenching. Thermal evaporation must be carefully optimized to prevent ligand dissociation or complex degradation at elevated temperatures, though the high vacuum environment minimizes oxidative damage during processing. The technique preserves molecular integrity for thermally stable complexes and enables precise control over dopant concentrations in host matrices through co-evaporation, which is particularly valuable for phosphorescent emitter systems in OLEDs [28].

Spin-coating offers advantages for processing coordination compounds with limited thermal stability but sufficient solubility in appropriate solvents. The ability to process at room temperature avoids thermal degradation pathways, while solution shearing during spinning can promote beneficial molecular orientation. However, coordination compounds often require specific solvent properties to maintain solvation without ligand substitution or complex dissociation, limiting formulation options. Post-deposition treatments like thermal annealing may be necessary to remove residual solvent and optimize morphology, potentially introducing thermal stress that negates the low-temperature processing advantage.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Thermal Evaporation of Coordination Compounds

Principle: This protocol details the vacuum thermal evaporation process for depositing thin films of coordination compounds, with specific adaptations for the thermal sensitivity and complex structure of these materials.

Materials and Equipment:

- High vacuum deposition system (≤10⁻⁶ Torr base pressure)

- Substrate (typically ITO-coated glass for OLED applications)

- Source materials (purified coordination compound)

- Shadow masks for patterning (if required)

- Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) thickness monitor

- Substrate heater with temperature controller

Procedure:

- Material Preparation: Purify the coordination compound using gradient sublimation or recrystallization. Load 50-200 mg into a clean, degassed evaporation crucible (typically ceramic or metal).

- Substrate Preparation: Pattern ITO substrates using standard photolithography and etching. Clean sequentially in ultrasonic baths of detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol (15 minutes each). Treat with oxygen plasma for 5-10 minutes to improve surface energy.

- System Evacuation: Load substrates and source materials into the deposition chamber. Pump down to high vacuum (≤10⁻⁶ Torr). This typically requires 2-6 hours depending on system volume and pump configuration.

- Pre-deposition Heating: Optionally heat substrates to 50-150°C (depending on material system) using the substrate heater. Maintain temperature for 30 minutes to desorb residual contaminants.

- Rate-Calibration Shutter: Engage the calibration shutter over the QCM. Slowly increase source current to establish a stable deposition rate of 0.5-2.0 Å/s. Monitor rate stability for 30-60 seconds.

- Film Deposition: Open the main deposition shutter while maintaining the calibrated rate. Deposit to the target thickness (typically 20-100 nm for emissive layers). For doped systems, use separate sources for host and dopant materials with individually calibrated rates to achieve the target doping concentration.

- Layer Completion: Close the deposition shutter and slowly decrease source current to zero. Allow the source to cool for 5-10 minutes before proceeding to subsequent layers.

- Post-processing: Transfer samples directly to an interconnected glovebox for encapsulation or further processing to prevent ambient degradation.

Critical Parameters:

- Vacuum quality: Maintain pressure below 5×10⁻⁶ Torr during deposition

- Deposition rate: 0.5-2.0 Å/s for most coordination compounds

- Substrate temperature: Optimized for specific material system

- Source-to-substrate distance: 30-50 cm for uniform deposition

Protocol: Spin-Coating of Coordination Compounds

Principle: This protocol describes the formation of thin films of coordination compounds using spin-coating, with emphasis on solution formulation and processing conditions that maintain molecular integrity.

Materials and Equipment:

- Programmable spin-coater with vacuum chuck

- Substrates (typically ITO-coated glass)

- Coordination compound solution in appropriate solvent

- Solvent filtration unit (0.2 μm PTFE membrane)

- Glovebox with integrated spin-coater (for oxygen/moisture-sensitive materials)

- Hotplate for post-annealing

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the coordination compound in an appropriate solvent (commonly chlorobenzene, toluene, or chloroform) at a concentration of 5-20 mg/mL. Stir for 2-12 hours at 30-50°C until complete dissolution. Filter through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter to remove particulates.

- Substrate Preparation: Clean ITO substrates following the same procedure as in Section 3.1. Apply appropriate surface treatment (UV-ozone, oxygen plasma, or self-assembled monolayers) to modify wettability.

- Static Dispense Method: Place substrate on vacuum chuck. Pipette 50-100 μL of solution (for 1×1 cm substrate) onto the stationary substrate center. Allow 5-30 seconds for initial spread and solvent evaporation.

- Spinning Process: Program the spin-coater with a two-step recipe:

- Step 1: 500-1000 RPM for 5-10 seconds (spread phase)

- Step 2: 1500-4000 RPM for 20-60 seconds (thinning phase)

- Exact parameters optimized for specific solution properties

- Solvent Annealing (Optional): Immediately after spinning, transfer the wet film to a sealed chamber containing a small volume of a poor solvent (typically diethyl ether or hexane) for 30-180 seconds to control crystallization.

- Thermal Annealing: Transfer the film to a preheated hotplate at 70-150°C (optimized for specific material) for 10-30 minutes to remove residual solvent and improve film morphology.

- Device Fabrication: For multilayer devices, ensure subsequent processing solvents are orthogonal (non-dissolving) to the deposited layer.

Critical Parameters:

- Solution concentration: 5-20 mg/mL (optimized for target thickness)

- Spin speed: 1500-4000 RPM (final thickness stage)

- Ambient control: <1 ppm O₂/H₂O for sensitive materials

- Acceleration rate: 500-1000 RPM/s for uniform films

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Deposition of Coordination Compounds

| Category | Specific Material/Equipment | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Deposition | Ceramic evaporation crucibles | Source containment | Withstand temperatures >1000°C |

| Quartz crystal monitors | Thickness/rate measurement | 6 MHz sensitivity standard | |

| Shadow masks | Device patterning | Typically stainless steel or invar | |

| Solution Processing | Chlorobenzene | Primary solvent | High boiling point (131°C) |

| PTFE syringe filters (0.2 μm) | Solution purification | Remove particulates >200 nm | |

| Self-assembled monolayers | Surface modification | Improve wettability/adhesion | |

| Substrate Materials | ITO-coated glass | Transparent conductor | 10-20 Ω/sq sheet resistance |

| Pre-patterned OLED substrates | Device test structures | Standardized electrode layouts | |

| Characterization | Spectroscopic ellipsometer | Film thickness measurement | Non-contact optical technique |

| Atomic force microscope | Surface morphology | Nanoscale roughness analysis | |

| Photoluminescence quantum yield | Optoelectronic quality | Absolute measurement capability |

The selection between thermal evaporation and spin-coating for depositing coordination compounds in optoelectronic devices represents a fundamental trade-off between precision and processability. Thermal evaporation offers unparalleled control over layer architecture and interfacial sharpness, making it indispensable for complex multilayer devices and materials with limited solubility. Recent developments in large-area evaporation sources and in-situ monitoring techniques continue to address scalability challenges, maintaining its dominance in commercial OLED manufacturing [28].

Spin-coating and related wet-processing techniques provide compelling advantages in materials utilization, throughput, and capital cost, particularly for rapidly prototyping new coordination compounds and investigating structure-property relationships. The growing emphasis on hybrid evaporation-solution processing approaches, where critical functional layers are evaporated while transport or blocking layers are solution-processed, represents an emerging compromise that leverages the strengths of both methodologies.

For coordination compounds specifically, the deposition technique must be evaluated within the broader context of molecular stability, device architecture requirements, and target application specifications. As material design advances produce complexes with enhanced thermal stability or tailored solubility characteristics, the optimal deposition strategy will continue to evolve, driving innovations in both vacuum and solution-based processing technologies.

Molecular Design and Synthesis of Fluorinated Ligands for Enhanced Efficiency and Stability

The strategic incorporation of fluorine atoms into organic ligands represents a powerful tool for advancing the performance of coordination compounds in optoelectronics and related fields. Fluorination confers beneficial modifications to key physicochemical properties, including enhanced thermal stability, improved charge carrier mobility, and superior oxidative resistance [29] [30]. In Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs), these property enhancements directly translate to devices with higher efficiency, purer color emission, and extended operational lifetimes [31] [32]. This Application Note provides a detailed experimental framework for the design, synthesis, and characterization of fluorinated ligands, with a specific focus on their application in coordination compounds for next-generation OLEDs. The protocols are designed to be accessible to researchers and scientists engaged in materials development for optoelectronics and drug development.

Quantitative Performance Data of Fluorinated Coordination Compounds

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for various fluorinated coordination compounds, highlighting the impact of ligand design on device efficacy.

Table 1: Performance of Fluorinated Neodymium(III) Complexes in NIR-OLEDs [3] [33]

| Complex ID | Fluorinated Ligand Structure | PLQY (%) | EQE (%) | Key Emission Wavelengths (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd1 | 4,4,4-trifluorobutane-1,3-dionato | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | 880, 1060, 1330 |

| Nd2 | 4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexane-1,3-dionato | 1.08 | 1.38×10⁻² | 880, 1060, 1330 |

| Nd3 | tridecafluorononane-1,3-dionato | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | 880, 1060, 1330 |

Table 2: Performance of Ytterbium(III) Complexes with a Trifluoroacetylpyrazolone Ligand in NIR-OLEDs [34]

| Ancillary Ligand | Power Density (µW/cm²) | Peak Emission Wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Bathophenanthroline | 2.17 | 978 |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | 1.92 | 1005 |

| 2,2'-Bipyridine | Data Not Specified | 978 & 1005 |

Table 3: Device Performance Enhancement Using a LiF/SiNx Capping Layer [32]

| Device Color | Current Efficiency (Control, cd/A) | Current Efficiency (with LiF/SiNx, cd/A) | FWHM (Control, nm) | FWHM (with LiF/SiNx, nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | 125.0 | 163.6 | 20 | 10 |

| Red | 71.2 | 110.1 | 26 | 14 |

| Blue | 43.1 | 53.1 | 21 | 12 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Fluorinated 1,3-Diketone Ligand (Representative Procedure)

This protocol outlines the synthesis of 5-methyl-2-phenyl-4-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one (HL), a ligand used in highly luminescent lanthanide complexes [34].

- Objective: To synthesize a trifluorinated pyrazolone-based ligand via acylation.

- Principle: A 5-methyl-2-phenylpyrazol-3-one core is functionalized at the 4-position using trifluoroacetic anhydride in a basic environment, forming the chelating β-diketone analog.

Materials:

- 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one

- Trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA)

- Anhydrous Pyridine

- Diethyl Ether or n-Hexane (for precipitation)

- Round-bottom flask (250 mL)

- Magnetic stirrer with heating plate

- Water bath (for cooling)

- Dropping funnel

- Vacuum filtration setup

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve 12.8 g (73 mmol) of 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one in 80 mL of dry pyridine in a 250 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar.

- Acylation: Cool the reaction flask in a cold water bath (maintaining temperature below 40°C). Using a dropping funnel, add 10 mL (72 mmol) of trifluoroacetic anhydride dropwise with vigorous stirring.

- Stirring and Completion: After the addition is complete, remove the cooling bath and stir the resulting dark red-brown solution at room temperature for 2 hours. Monitor the reaction by TLC.

- Precipitation and Isolation: Pour the reaction mixture into a beaker containing approximately 200 mL of ice-cold water or acidified ice water (to neutralize pyridine). The crude product should precipitate.

- Purification: Collect the solid product by vacuum filtration. Wash the filter cake thoroughly with cold water, followed by a small volume of cold diethyl ether or n-hexane to remove impurities. Recrystallize the crude solid from an appropriate solvent (e.g., ethanol) to obtain the pure ligand (HL) as crystalline solid.

- Characterization: Confirm the structure and purity by (^1)H NMR, (^{19})F NMR, and elemental analysis.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a Solution-Processed OLED with Zinc(II) Complexes