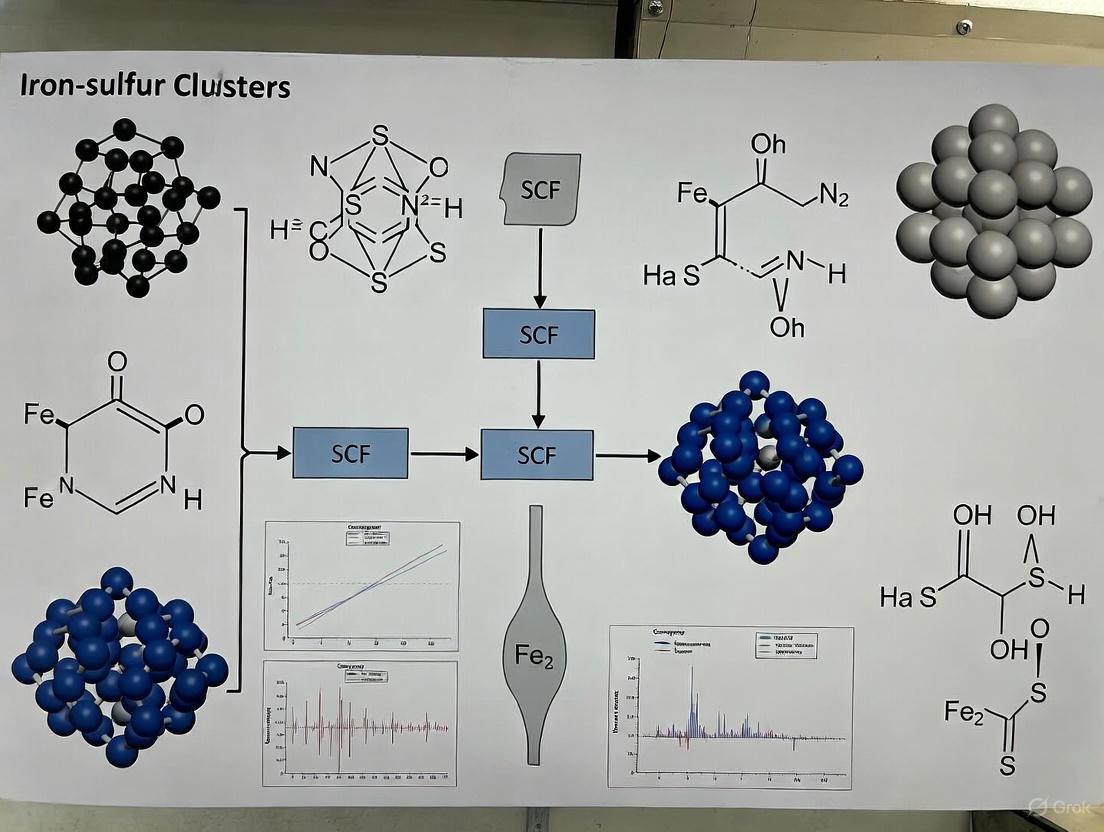

Conquering SCF Convergence in Iron-Sulfur Clusters: From Electronic Structure Challenges to Robust Computational Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists tackling the notorious self-consistent field (SCF) convergence challenges in iron-sulfur clusters.

Conquering SCF Convergence in Iron-Sulfur Clusters: From Electronic Structure Challenges to Robust Computational Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists tackling the notorious self-consistent field (SCF) convergence challenges in iron-sulfur clusters. We explore the foundational electronic structure complexities, including antiferromagnetic coupling and multi-center radical character, that make these systems difficult for standard computational methods. The review covers established and emerging methodological strategies, from broken-symmetry DFT and spin-flip techniques to novel configuration state function approaches. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers practical optimization protocols for difficult cases, while validation frameworks help benchmark results against state-of-the-art quantum and classical computations. This synthesis of current knowledge aims to equip computational chemists and drug development professionals with reliable strategies for modeling these biologically essential cofactors.

The Electronic Structure Puzzle: Why Iron-Sulfur Clusters Challenge Conventional SCF Methods

Multireference Character and Static Correlation in [4Fe-4S] Clusters

Iron-sulfur ([Fe-S]) clusters are ancient, ubiquitous protein cofactors that play vital roles in electron transfer, enzyme catalysis, and gene regulation across all domains of life. The [4Fe-4S] cluster, a cuboidal arrangement of four iron and four sulfur atoms, exhibits particularly complex electronic structures characterized by strong electron correlation and multireference character. These properties present formidable challenges for computational chemistry methods, especially self-consistent field (SCF) convergence, while simultaneously enabling the clusters' remarkable functional diversity in biological systems and their emerging potential as therapeutic targets. This technical review examines the electronic structure origins of multireference character in [4Fe-4S] clusters, details associated computational challenges and solutions, summarizes experimental characterization methodologies, and explores implications for drug development targeting Fe-S cluster-containing proteins.

Iron-sulfur clusters are among the most ancient and versatile protein cofactors, with [4Fe-4S] clusters representing one of the most common forms found in nature [1]. These clusters are essential components of numerous biological processes, including cellular respiration, DNA repair, gene regulation, and enzyme catalysis [2] [1]. Their prevalence in critical metabolic pathways across all domains of life underscores their fundamental importance to biological systems.

The electronic structure of [4Fe-4S] clusters is characterized by multiple near-degenerate electronic states and strong electron correlation effects. This arises from the partially filled 3d orbitals on the iron atoms and their antiferromagnetic coupling through bridging sulfide ligands [3]. The resulting multireference character means that no single electronic configuration can adequately describe the ground state, necessitating computational methods that account for significant static correlation. This electronic complexity directly enables the functional versatility of these clusters but also creates substantial challenges for computational modeling.

In therapeutic contexts, Fe-S clusters are increasingly recognized as potential drug targets. Their sensitivity to oxidative and nitrosative stress makes them vulnerable points in pathogenic organisms and cancer cells [2] [1]. Understanding their electronic properties is thus essential for both basic biochemical research and drug development efforts targeting Fe-S cluster-containing proteins.

Electronic Structure and Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Electronic Properties

The electronic structure of [4Fe-4S] clusters exhibits several distinctive features that directly contribute to their multireference character and computational challenges:

- High-spin iron sites: Each iron atom in [4Fe-4S] clusters typically adopts a high-spin configuration with tetrahedral coordination to sulfur atoms [3].

- Spin polarization: The iron sites demonstrate substantial spin polarization splitting between majority spin (α) and minority spin (β) molecular orbitals [3].

- Metal-ligand covalency: Strong covalent bonding exists between iron d-orbitals and sulfur ligand orbitals, with greater covalency for Fe³⁺ sites than Fe²⁺ sites [3].

- Heisenberg exchange coupling: Antiferromagnetic coupling between adjacent iron sites occurs via bridging sulfide ligands, leading to complex spin coupling patterns [3].

- Valence delocalization: In mixed-valence dimers with Fe²⁺-Fe³⁺ pairs, resonance delocalization creates additional electronic complexity [3].

Table 1: Key Electronic Properties of [4Fe-4S] Clusters and Their Computational Implications

| Electronic Property | Structural Origin | Computational Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Multireference character | Near-degenerate electronic configurations | Single-reference methods (e.g., RHF, CCSD) fail |

| Strong electron correlation | Partially filled 3d orbitals on iron atoms | Necessitates multiconfigurational methods |

| Spin polarization | High-spin iron sites with unpaired electrons | Requires spin-unrestricted calculations |

| Antiferromagnetic coupling | Superexchange through bridging sulfides | Complex spin ordering with low-spin ground states |

| Valence delocalization | Electron sharing in mixed-valence pairs | Resonance stabilization effects |

Quantum Chemical Characterization

The complex electronic structure of [4Fe-4S] clusters creates significant challenges for computational methods. Restricted Hartree-Fock (RHF) and coupled cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) methods fundamentally break down for these systems because they rely on a single-reference description that cannot capture the strong static correlation [4]. Even density functional theory (DFT) with standard functionals often struggles with the multireference character and delocalization effects.

Recent advances in quantum computing approaches have enabled more accurate treatment of these systems. The Sample-based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) method has been applied to [4Fe-4S] clusters using active spaces of 54 electrons in 36 orbitals—corresponding to a Hilbert space dimension of approximately 8.86×10¹⁵—far beyond the reach of exact diagonalization on classical computers [4]. This method has yielded ground-state energy estimates of -326.635 Eₕ for a [4Fe-4S] model system, intermediate between RHF (-326.547 Eₕ) and CISD (-326.742 Eₕ) results, demonstrating the limitations of conventional quantum chemistry methods for these systems [4].

Figure 1: Electronic Structure Relationships in [4Fe-4S] Clusters. The diagram illustrates the causal pathway from fundamental properties of iron ions to computational challenges.

SCF Convergence Challenges and Solutions

Origins of SCF Convergence Problems

The self-consistent field (SCF) procedure in quantum chemistry calculations frequently encounters severe convergence difficulties when applied to [4Fe-4S] clusters and other transition metal systems. These problems originate from several interconnected factors:

Open-shell character: Transition metal complexes, particularly open-shell species, present inherent challenges for SCF convergence [5]. The presence of multiple unpaired electrons leads to numerous near-degenerate solutions that complicate the convergence landscape.

Strong correlation effects: The significant multireference character in [4Fe-4S] clusters means that single-determinant descriptions provide poor initial guesses, leading to oscillations between different electronic configurations during the SCF procedure [4].

Metal cluster complexity: Polynuclear metal clusters like [4Fe-4S] exhibit complex potential energy surfaces with multiple local minima, causing the SCF procedure to oscillate between different solutions rather than converging to the true ground state [5].

Orbital near-degeneracy: The presence of numerous near-degenerate molecular orbitals results in small energy gaps between occupied and virtual orbitals, violating the assumptions underlying standard SCF convergence algorithms [6].

Practical Solutions for SCF Convergence

Table 2: SCF Convergence Strategies for [4Fe-4S] Cluster Calculations

| Method | Key Parameters | Applicability | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damping (!SlowConv) | Modified damping parameters | Early SCF iterations with large fluctuations | Slows convergence but stabilizes early cycles |

| KDIIS + SOSCF | SOSCFStart 0.00033 (reduced by 10x) | When DIIS struggles with trailing convergence | Faster convergence once orbital gradient threshold met |

| Second-order methods (NRSCF, AHSCF) | Exact Hessian information | Pathological cases with strong oscillations | More expensive per iteration but fewer iterations |

| TRAH (Trust Radius Augmented Hessian) | AutoTRAHTol 1.125, AutoTRAHIter 20 | Automatically activated when DIIS struggles | Robust but slower; default in ORCA 5.0+ |

| Increased iterations + MORead | MaxIter 500-1500, MORead "guess.gbw" | All difficult cases | Simple but effective; requires good initial guess |

For particularly pathological cases, specialized SCF settings are often required. The following configuration has proven effective for converging large iron-sulfur clusters [5]:

This approach combines strong damping (!SlowConv) with an expanded DIIS subspace (DIISMaxEq 15) and frequent rebuilds of the Fock matrix (directresetfreq 1) to eliminate numerical noise that hinders convergence [5].

The augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) algorithm, an exact Newton SCF method, has demonstrated particular effectiveness for strongly correlated molecules including iron-sulfur clusters, providing an excellent compromise between stability and computational cost [6].

Experimental Characterization and Methodologies

Biochemical Preparation of [4Fe-4S] Clusters

The study of [4Fe-4S] clusters requires specialized biochemical techniques to produce and stabilize these oxygen-sensitive cofactors:

Anaerobic purification: Native [4Fe-4S] cluster-containing proteins like WhiD require anaerobic purification from E. coli to obtain soluble protein with intact clusters [7]. This involves maintaining oxygen-free conditions throughout cell lysis and chromatography.

Cluster reconstitution: For proteins that express primarily as apo-forms, in vitro reconstitution can incorporate [4Fe-4S] clusters. This typically involves incubation with iron salts (e.g., FeCl₃) and sulfide sources (e.g., Na₂S) under anaerobic conditions [8].

Stabilization conditions: The stability of [4Fe-4S] clusters is highly pH-dependent, with optimal stability observed between pH 7.0 and 8.0. Low molecular weight thiols, including mycothiol analogues and thioredoxin, provide modest protective effects against cluster loss [7].

Cluster transfer assays: The functionality of assembled [4Fe-4S] clusters can be assessed through transfer experiments to apo-proteins. Studies with ISCA and NFU proteins demonstrate rapid, unidirectional [4Fe-4S]²⁺ cluster transfer to mitochondrial apo-aconitase [8].

Spectroscopic Characterization Techniques

Multiple spectroscopic methods are employed to characterize the structure and electronic properties of [4Fe-4S] clusters:

UV-visible absorption spectroscopy: Provides information on cluster type and integrity based on characteristic absorption features between 300-500 nm [8].

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy: Sensitive to cluster chirality and environment, useful for monitoring cluster conversion and degradation [8].

Resonance Raman spectroscopy: Provides vibrational information enhanced by electronic resonance, yielding details about Fe-S bonding and cluster structure [8].

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy: Detects paramagnetic states of clusters, including intermediate oxidation states and spin couplings [3] [9].

Mössbauer spectroscopy: Offers detailed information about iron oxidation states, spin states, and electronic environments in cluster irons [3].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for [4Fe-4S] Cluster Studies. The diagram outlines key methodological stages from protein preparation to functional analysis.

Iron-Sulfur Clusters as Therapeutic Targets

Mechanisms of Cluster Disruption

The inherent reactivity of Fe-S clusters with various small molecules forms the basis for their targeting by therapeutic compounds:

ROS-mediated disruption: Reactive oxygen species, including superoxide (O₂•⁻) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), can oxidize [4Fe-4S] clusters, converting them to [3Fe-4S]⁺ and ultimately to [2Fe-2S]²⁺ clusters [2]. WhiD reacts much more rapidly with superoxide than with oxygen or hydrogen peroxide [7].

NOS-mediated disruption: Nitric oxide species (NOS), particularly nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), directly attack Fe-S clusters. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, WhiB3 contains a [4Fe-4S] cluster that reacts specifically with NO, controlling redox homeostasis and virulence [2].

Metal displacement: Certain metals, including copper, aluminum, and cobalt, can displace iron from clusters or compete with iron during cluster biogenesis. Copper toxicity specifically results from liganding to sulfur atoms that coordinate the clusters [2].

Direct cluster interaction: Some drugs, such as primaquine and cluvenone derivatives, directly interact with Fe-S clusters, either destabilizing or stabilizing them depending on the specific compound [2].

Specific Therapeutic Applications

Table 3: Therapeutic Agents Targeting Fe-S Clusters

| Drug/Therapeutic Agent | Therapeutic Application | Target Fe-S Protein/Process | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyurea | Sickle cell disease, leukemia | Leu1 | ROS-mediated cluster disruption |

| Primaquine | Malaria | Rli1, aconitase | Direct Fe-S interaction and ROS-mediated damage |

| Cluvenone derivatives (MAD-28) | Cancer | MitoNEET, NAF-1 | Fe-S cluster destabilization |

| Pioglitazone | Diabetes | MitoNEET, NAF-1 | Fe-S cluster stabilization |

| β-Phenethyl isothiocyanate | Leukemia | NADH dehydrogenase (Complex I) | ROS-mediated cluster damage |

| Antibiotics | Bacterial infections | Multiple bacterial Fe-S proteins | ROS-mediated damage (debated) |

The sensing function of [4Fe-4S] clusters in regulatory proteins provides another therapeutic targeting strategy. The global iron regulator RirA in Rhizobium senses iron through reversible dissociation of Fe²⁺ from its [4Fe-4S]²⁺ cluster to form [3Fe-4S]⁰, with a dissociation constant of ~3 µM consistent with cytoplasmic iron sensing [9]. Oxygen sensing occurs through enhanced cluster degradation under aerobic conditions via oxidation of the [3Fe-4S]⁰ intermediate [9]. Understanding these sensing mechanisms could inform antimicrobial strategies targeting bacterial iron regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for [4Fe-4S] Cluster Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic chamber | Maintains oxygen-free environment | Cluster purification and manipulation |

| Iron salts (FeCl₃, FeNH₄(SO₄)₂) | Iron source for cluster reconstitution | In vitro cluster assembly |

| Sulfide sources (Na₂S) | Sulfide source for cluster reconstitution | In vitro cluster assembly |

| Low molecular weight thiols | Protective agents against cluster oxidation | Cluster stabilization during purification |

| Mycothiol analogues | Physiological thiol replacement | Protection studies in actinomycetes |

| Volatile buffers (ammonium acetate) | Maintain protein structure during MS | Non-denaturing mass spectrometry |

| Specialized EPR cuvettes | Sample containment for spectroscopy | Paramagnetic characterization of clusters |

The multireference character and static correlation effects in [4Fe-4S] clusters present both significant challenges and unique opportunities across multiple scientific disciplines. From a computational perspective, these electronic properties necessitate specialized SCF convergence strategies and advanced electronic structure methods, including emerging quantum computing approaches. For experimental biochemists, the sensitivity of these clusters to oxygen and redox changes requires sophisticated anaerobic techniques but also enables their function as biological sensors. In therapeutic development, the very reactivity that complicates computational and experimental work makes Fe-S clusters valuable targets for antimicrobial and anticancer drugs.

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating computational and experimental approaches to better predict and control cluster behavior, developing more sophisticated quantum-chemical methods specifically designed for multireference systems, and exploiting the unique properties of Fe-S clusters for biomedical applications. As our understanding of these ancient cofactors continues to deepen, so too will our ability to harness their remarkable properties for both basic scientific advancement and therapeutic innovation.

Antiferromagnetic Coupling and High-Spin Iron Sites

Antiferromagnetic (AFM) coupling describes a magnetic phenomenon where adjacent atomic spins align in an alternating, opposite pattern, resulting in no net magnetization in the absence of an external field. [10] This phenomenon, alongside the properties of high-spin iron sites, is fundamental to understanding complex magnetic materials and biological systems, particularly iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters. These clusters are among the most ancient and versatile metal cofactors found in nature, present in proteins involved in electron transport, gene regulation, and DNA repair. [11] The study of their electronic structure, however, is notoriously hampered by challenges in achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence in quantum chemical calculations. [5] [6] This technical guide delves into the mechanisms of antiferromagnetic coupling in systems containing high-spin iron, provides detailed experimental and computational protocols for its investigation, and outlines advanced strategies to overcome the associated SCF convergence difficulties, providing a critical resource for researchers in material science, chemistry, and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Mechanisms

Fundamentals of Antiferromagnetism

In antiferromagnetic materials, the magnetic moments of atoms or molecules align in a regular pattern with neighboring spins pointing in opposite directions. [10] This magnetic order is stable only below a certain critical temperature, known as the Néel temperature. Above this temperature, thermal energy disrupts the ordered alignment, and the material transitions to a paramagnetic state. The measurement of magnetic susceptibility typically shows a maximum at the Néel temperature, which contrasts with the divergent susceptibility observed at the Curie point of ferromagnetic materials. [10] Antiferromagnetism is commonly observed in transition metal compounds, including oxides like hematite (α-Fe2O3) and nickel oxide (NiO), as well as in metals like chromium and alloys such as iron manganese (FeMn). [10]

Antiferromagnetic Coupling in Iron-Based Systems

A quintessential example of antiferromagnetic coupling involves rare earth (RE) adatoms on iron surfaces. Spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscopy (SP-STM) studies have demonstrated that thulium (Tm) and lutetium (Lu) adatoms deposited on iron monolayer islands exhibit in-plane magnetic moments that couple antiferromagnetically with the underlying iron island. [12] This occurs despite the different magnetic nature of the adatoms themselves—Tm has a partially filled 4f shell, while Lu is magnetically inert. The observed behavior is attributed to an antiparallel coupling between the induced 5d electron magnetic moment of the lanthanides and the 3d magnetic moment of the iron, with the 4f electrons playing no direct role in the spin-polarized tunneling process. [12] This indicates that the outer 5d electrons are the primary mediators of magnetic interactions in these systems.

In more complex structures like Fe/Fe₃O₄ junctions, the mechanism of antiparallel coupling can be influenced by interface structure. First-principles calculations reveal that while parallel coupling is stable for ideal junctions, the introduction of extra iron atoms on hollow sites of the spinel lattice at the interface stabilizes antiferromagnetic coupling. This suggests that magnetic frustration from a non-uniform distribution of interfacial atoms can be a critical factor. [13]

Spin Coupling in Iron-Sulfur Clusters

Iron-sulfur clusters are inorganic cofactors composed of iron and sulfur atoms, and their functionality in proteins often depends on the spin states of the iron sites and the coupling between them. [11] In a model [Fe₄S₄(SH)₄]²⁻ cubane cluster, the iron sites can exist in high-spin ferrous (Fe²⁺, S = 2) or ferric (Fe³⁺, S = 5/2) states. [14] The relative alignment of the individual spin vectors on these metal centers determines the overall magnetic state of the cluster.

Table 1: Common Oxidation and Spin States of Iron in Fe-S Clusters

| Iron Type | Oxidation State | Spin State (S) |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrous | Fe²⁺ | 2 |

| Ferric | Fe³⁺ | 5/2 |

The simplest magnetic configuration is the high-spin (HS) state, where all spins are aligned ferromagnetically. For a cubane with two ferric and two ferrous ions, this gives a total spin of S = 9. [14] However, this is typically not the most stable electronic state. Lower-energy "broken symmetry" (BS) states are achieved through antiferromagnetic coupling between different iron sites, resulting in a complex spin landscape that is computationally challenging to describe accurately. [14]

Experimental Investigations and Protocols

Probing Spin Coupling with Spin-Polarized STM

Methodology Overview SP-STM and scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) are powerful techniques for characterizing magnetic phenomena at the single-atom level. [12] The following protocol is adapted from studies on rare earth adatoms on Fe monolayers:

- Sample Preparation: Grow Fe monolayer islands pseudomorphically on a W(110) single crystal substrate. [12]

- Atom Deposition: Deposit RE atoms (e.g., Tm or Lu) onto the sample surface held at low temperature (typically 4-10 K) to ensure immobility. [12]

- SP-STM/STS Measurement:

- Use a spin-polarized tip (often coated with a magnetic material like iron).

- Acquire constant-current topographies to locate adatoms and islands.

- Perform differential conductivity (dI/dV) measurements to probe the local density of states. This is done by superposing a small AC voltage modulation (e.g., 1-10 mV rms at 831 Hz) on the DC bias voltage and measuring the resulting current modulation with a lock-in amplifier. [12]

- Record dI/dV spectra at specific points (e.g., on different islands and adatoms) and generate dI/dV maps over an area at a fixed bias to visualize magnetic contrast. [12]

- Data Interpretation: Magnetic contrast in dI/dV maps and spectra arises from the relative alignment between the tip's magnetization and the sample's spin moment. An adatom showing lower dI/dV signal than the underlying island indicates an antiparallel spin alignment, confirming antiferromagnetic coupling. [12]

Figure 1: SP-STM experimental workflow for probing antiferromagnetic coupling at the atomic scale.

Computational Protocol for Spin Coupling in Fe₄S₄ Clusters

For computational studies, achieving the correct spin-coupled state is a multi-step process:

A. Obtaining the High-Spin Reference State

- Model Construction: Build the Fe₄S₄(SH)₄²⁻ cluster model, ensuring proper coordination and geometry. [14]

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a geometry optimization using density functional theory (DFT) with an appropriate functional and basis set. This system can be difficult, so robust optimizers are required. [14]

- High-Spin Single-Point Calculation: Run a single-point energy calculation on the optimized structure with an unrestricted DFT formalism. Set the total charge to -2 and the spin polarization to 18 (corresponding to the S = 9 high-spin state with all four Fe spins aligned). [14] This calculation is generally easier to converge and provides a reference solution.

B. Achieving the Antiferromagnetically Coupled "Broken Symmetry" State

- Restart from High-Spin Solution: Set up a new single-point calculation, restarting from the converged high-spin solution. [14]

- Apply Spin Flip: Use the

SpinFlipoption to interchange the α (↑) and β (↓) electron densities on specific Fe atoms to create the desired antiferromagnetic arrangement (e.g., a 2↑:2↓ configuration). [14] - Lower Symmetry: Reduce the symmetry of the calculation (e.g., to

NOSYM) to accommodate the lower symmetry of the broken-symmetry state. [14] - SCF Convergence: Run the calculation with a reduced total spin polarization (e.g., S = 0) to converge to the broken-symmetry solution. [14]

Table 2: Key Computational Parameters for Fe₄S₄ Cluster Spin States

| Parameter | High-Spin (HS) State | Broken-Symmetry (BS) State |

|---|---|---|

| Total Charge | -2 | -2 |

| Spin Polarization | 18 | 0 |

| Unrestricted Calculation | Yes | Yes |

| Initial Guess | Default | Restart from HS solution |

| SpinFlip | Not Applied | Applied to selected Fe atoms |

| Point Group Symmetry | High (e.g., T(D)) | Low (e.g., NOSYM) |

Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges

Quantum chemical calculations of open-shell transition metal systems, especially antiferromagnetically coupled clusters, are plagued by SCF convergence failures. These arise from the presence of multiple low-lying electronic states with similar energies and the multi-center radical character of the systems. [14] [5]

Advanced SCF Algorithms and Strategies

Second-Order Convergence Methods: For pathological cases, first-order convergence algorithms like DIIS may fail. The Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) approach is a robust second-order converger that is often automatically activated in modern software like ORCA when instability is detected. [5] The augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) algorithm has also proven highly effective for strongly correlated molecules like iron-sulfur clusters, offering an excellent compromise between stability and computational cost. [6]

Keyword-Assisted Convergence: Most quantum chemistry packages offer keywords that adjust the SCF procedure for difficult cases:

- !SlowConv / !VerySlowConv: These keywords increase damping parameters to control large fluctuations in the initial SCF iterations. [5]

- !KDIIS: The KDIIS algorithm, sometimes combined with the SOSCF (Second-Order SCF) algorithm, can enable faster convergence. [5]

- Manual Tuning: For truly pathological systems, manual SCF setting adjustments are necessary. This can include increasing the maximum number of iterations (

MaxIterto 1500), increasing the number of DIIS error vectors (DIISMaxEqto 15-40), and increasing the frequency of Fock matrix rebuilds (directresetfreqto a value between 1 and 15) to reduce numerical noise. [5]

A Protocol for Converging Pathological Systems

The following protocol, effective for large iron-sulfur clusters, combines several strategies: [5]

- Initial Attempt: First, try to converge a simpler system, such as using a smaller basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) or a different functional (e.g., BP86).

- Use Advanced Keywords: If the default SCF fails, employ

!SlowConvand!KDIISkeywords. - Enable Second-Order Methods: If oscillations or slow convergence persist, allow the TRAH algorithm to activate or manually use a second-order method like

!NRSCF. - Manual SCF Tuning: As a last resort, implement a highly robust but expensive SCF procedure with the following settings:

- Alternative Guess: If the above fails, try converging a closed-shell oxidized state of the cluster and use its orbitals as the initial guess for the target open-shell calculation. [5]

Figure 2: Troubleshooting workflow for SCF convergence in difficult iron-sulfur systems.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Fe-S Cluster and Magnetic Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Spin-Polarized STM/STS | Probes spin-polarized local density of states at atomic scale. | Directly measuring antiferromagnetic coupling of adatoms on surfaces. [12] |

| Broken-Symmetry (BS) DFT | Computational method for describing antiferromagnetic coupling. | Calculating the electronic structure and coupling strength in Fe₄S₄ clusters. [14] |

| ADF Modeling Software | DFT software package with specialized options for spin control. | Using the SpinFlip and ModifyStartPotential keys to achieve BS states. [14] |

| ORCA Modeling Software | DFT software package with advanced SCF convergence algorithms. | Converging pathological Fe-S clusters using TRAH and manual SCF settings. [5] |

| ISC Assembly Machinery | Highly conserved biological system for Fe-S cluster biogenesis. | Studying the in-vivo assembly and insertion of Fe-S clusters in proteins. [11] |

Multiple Local Minima in Energy Landscapes

The exploration of energy landscapes is fundamental to understanding molecular behavior, particularly for complex quantum chemical systems where the existence of multiple local minima presents significant challenges for computational methods. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in systems with strong electron correlation effects, such as iron-sulfur clusters, where the potential energy surface contains numerous stationary points that can trap conventional optimization algorithms. The problem extends beyond mere computational inconvenience—these multiple minima correspond to physically distinct electronic configurations with potentially different chemical properties and reactivity [15].

In the context of self-consistent field (SCF) theory, the convergence challenges arising from multiple minima are particularly acute for open-shell electronic structures with complex spin coupling patterns. Recent investigations have revealed that iron-sulfur complexes exhibit "the potential for many local CSF energy minima," making them exceptionally difficult to optimize using standard quantum chemical approaches [15]. This multiplicity of minima is intimately connected to the near-degeneracy of configurations with different spin alignments, such as ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic states, which are characteristic of transition metal complexes [15].

The fundamental issue stems from each molecular orbital in a low-spin configuration being an eigenfunction of a different Fock operator, creating a complex optimization landscape with numerous local minima [15]. This challenge is analogous to the biological energy landscapes studied in cell fate decisions, where cells navigate multidimensional landscapes with multiple attractors representing different stable states [16]. In quantum chemistry, however, the consequences are directly computational—failed or suboptimal convergence that can lead to physically meaningless results or incorrect predictions of molecular properties.

Theoretical Framework: Energy Landscapes and SCF Convergence

Fundamental Concepts of Energy Landscapes

The concept of energy landscapes provides a powerful framework for understanding molecular stability and reactivity. In computational chemistry, an energy landscape represents the hypersurface describing the energy of a system as a function of its electronic and nuclear coordinates. Within this landscape, local minima correspond to stable or metastable states of the system, while saddle points represent transition states between them. The topography of this landscape—including the depth, distribution, and connectivity of minima—determines the system's behavior and the challenges associated with finding its true ground state [16].

The energy landscape framework has roots in Waddington's epigenetic landscape, a qualitative metaphor for cell fate decisions where pluripotent cells are visualized as marbles rolling down a landscape with multiple valleys representing different differentiation paths [16]. In quantum chemistry, this concept becomes quantitative through precise mathematical formulation, where each theoretically possible electronic configuration is assigned a specific energy value based on the system's Hamiltonian and wavefunction ansatz.

Mathematical Formulation of the Multiple Minima Problem

For electronic structure methods, the multiple minima problem can be formalized through the configuration space of molecular orbitals. Given a set of orthonormal molecular orbitals {ψi}, the electronic energy E[{ψi}] forms a complex hypersurface with critical points satisfying:

∇E[{ψi}] = 0

The Hessian matrix at these points, containing second derivatives of the energy with respect to orbital rotations, determines whether a critical point is a minimum (all positive eigenvalues), saddle point (mixed eigenvalues), or maximum (all negative eigenvalues). The presence of numerous negative or near-zero eigenvalues in the Hessian indicates a complex landscape with many stationary points [15].

In open-shell systems, the situation becomes more complex because "each orbital must be an eigenfunction of a different Fock operator" [15]. This multiplicity of Fock operators dramatically increases the complexity of the energy landscape, creating the conditions for numerous local minima that represent different orbital localization patterns and spin coupling schemes.

Iron-Sulfur Clusters: A Case Study in Complex Energy Landscapes

Electronic Structure Complexity in Iron-Sulfur Clusters

Iron-sulfur clusters represent particularly challenging systems for electronic structure calculations due to their complex electronic configurations with multiple nearly degenerate states. These inorganic cofactors, particularly the prevalent cubane-type [4Fe-4S] clusters, contain multiple metal centers with unpaired electrons that can couple in various antiferromagnetic arrangements [17]. The electronic structure is characterized by mixed valence layers where "the majority spin of two irons in a [4Fe4S] cluster is antiparallel to that of the other two according to the two-layer model" [17].

This spin coupling creates a situation where electrons are delocalized in specific patterns, effectively resulting in "a mixed valence layer of two Fe²·⁵⁺" ions [17]. The quantum mechanical phenomenon of spin coupling leads to layered arrangements of redox states in [4Fe4S] clusters, with remarkable dynamic responses to environmental changes such as light-induced redox processes observed in photolyase enzymes [17]. This complexity manifests computationally as a energy landscape with numerous local minima corresponding to different electron localization patterns.

Multiple Minima in Iron-Sulfur Cluster Calculations

Recent research has systematically investigated the energy landscape of iron-sulfur clusters using advanced computational methods. These investigations reveal that "many local minima can exist and that solutions with unpaired electrons localized in Fe 3d orbitals (which might be predicted from chemical intuition) are not necessarily local minima for all CSF spin states" [15]. This surprising finding challenges conventional chemical intuition and highlights the critical importance of thorough landscape exploration rather than relying on presumed orbital structures.

Table 1: Characteristics of Local Minima in Iron-Sulfur Cluster Energy Landscapes

| Minima Type | Electron Localization | Spin Coupling Pattern | Relative Energy | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Minimum | Biased delocalization | Antiferromagnetic | 0.0 kcal/mol | Biological relevant state |

| Local Minimum 1 | Localized Fe centers | Alternative coupling | 2.3 kcal/mol | Metastable excited state |

| Local Minimum 2 | Different delocalization | Mixed spin alignment | 5.7 kcal/mol | Non-physical solution |

| Local Minimum 3 | Symmetric delocalization | Ferromagnetic | 12.4 kcal/mol | High-energy artifact |

The table illustrates how different minima correspond to distinct electronic configurations with varying degrees of physical relevance. The existence of these multiple minima poses significant challenges for SCF convergence, as standard algorithms can easily become trapped in non-physical or metastable states that do not represent the true ground state of the system.

Methodological Approaches: Navigating Complex Energy Landscapes

Advanced SCF Algorithms for Challenging Systems

To address the challenges posed by multiple minima in energy landscapes, several advanced computational approaches have been developed:

Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM): This approach employs "quasi-Newton Riemannian optimization on the orbital constraint manifold to provide robust convergence," extending the GDM approach to open-shell electronic structures with arbitrary genealogical spin coupling [15]. The CSF-GDM variant specifically addresses configuration state functions with complex spin coupling.

Three-State Logic Framework: Adapted from biological network modeling, this approach decouples gene expression (ON/OFF) from its effect on targets (positive/negative/neutral) to remove inadvertent symmetries in energy landscapes [16]. While developed for biological networks, this conceptual framework inspires analogous approaches in electronic structure theory.

Stochastic Landscape Exploration: This method "probes the shape of the energy landscape through weighted random walk," effectively releasing multiple starting points to map the probability of reaching different attractors [16]. This approach helps identify the basins of attraction for different minima.

Experimental Protocols for Energy Landscape Mapping

Comprehensive characterization of energy landscapes requires systematic protocols:

The protocol involves iterative cycles of SCF optimization from randomly perturbed starting points, followed by characterization of the resulting stationary points through Hessian analysis. This approach ensures comprehensive mapping of the energy landscape rather than finding a single solution.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Addressing Multiple Minima

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Limitations | Applicability to Fe-S Clusters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF-GDM | Riemannian optimization on orbital manifold | Robust convergence, mean-field cost | Requires specialized implementation | Excellent for arbitrary spin coupling |

| Stochastic Sampling | Weighted random walk on landscape | Comprehensive basin mapping | Computationally intensive | Good for small clusters |

| Meta-dynamics | Modified potential energy surface | Enhances barrier crossing | Parameter-dependent | Limited application |

| Generalized SCF | Multiple Fock operators | Theoretically rigorous | Convergence difficulties | Standard approach with limitations |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF-GDM Algorithm | Orbital optimization for low-spin CSFs | Open-shell system SCF convergence | Riemannian optimization, mean-field cost [15] |

| Dynamic Crystallography | Imaging electron density changes | Experimental validation of spin coupling | Cryo-trapping, serial Laue diffraction [17] |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) | Analysis of multiple datasets | Identifying common features in dynamic data | Joint analysis of variable conditions [17] |

| Three-State Logic Framework | Removing inadvertent symmetries | Energy landscape construction | Decouples expression from effect [16] |

| inSituX Platform | In situ Laue diffraction at room temperature | Protein crystallography of metal clusters | Automated serial data collection [17] |

| Quantum Chemical Codes | Electronic structure calculations | Energy landscape mapping | Support for complex spin states [15] |

Implications for Drug Development and Metalloprotein Engineering

The challenges posed by multiple local minima in energy landscapes have significant implications for drug development targeting metalloenzymes and metalloprotein engineering. Iron-sulfur clusters are essential cofactors in numerous biological processes, including DNA repair, cellular respiration, and enzymatic catalysis [17]. Accurate computational prediction of their electronic properties is crucial for:

Rational Drug Design: Understanding the electronic structure of metalloenzyme active sites enables targeted inhibitor development. The presence of multiple minima complicates predictions of ligand binding affinities and reaction mechanisms.

Protein Engineering: Designing novel metalloproteins with specific redox properties requires accurate computational models that can reliably predict ground states rather than becoming trapped in non-physical local minima.

Mechanistic Studies: Elucidating reaction mechanisms in metalloenzymes depends on correct identification of the electronic ground state and accessible excited states, all of which are complicated by the complex energy landscape.

The convergence difficulties in SCF calculations for these systems can lead to incorrect predictions of spin states, redox potentials, and spectroscopic properties if computations settle in non-physical local minima rather than the true ground state. This underscores the critical importance of robust optimization algorithms that can navigate complex energy landscapes effectively.

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The study of multiple local minima in energy landscapes represents an ongoing challenge at the intersection of computational chemistry, physics, and biology. Future research directions include:

Improved Optimization Algorithms: Development of more sophisticated optimization techniques that efficiently navigate complex energy landscapes while maintaining physical meaningfulness of solutions.

Machine Learning Approaches: Application of machine learning methods to predict landscape topography and identify promising regions for thorough investigation, potentially reducing computational costs.

Experimental-Computational Integration: Tighter coupling between advanced experimental techniques like dynamic crystallography [17] and computational mapping of energy landscapes to validate predictions.

Multiscale Modeling: Bridging between quantum mechanical energy landscapes and biological function to understand how electronic complexity enables biological specificity.

In conclusion, the problem of multiple local minima in energy landscapes presents significant challenges for SCF convergence in iron-sulfur cluster research and other complex quantum chemical systems. Through advanced computational methods like the CSF-GDM algorithm [15] and sophisticated experimental approaches like dynamic crystallography [17], researchers are developing increasingly powerful tools to navigate these complex landscapes. The solution lies not in avoiding the complexity but in developing methods that embrace and characterize the full topography of these multidimensional surfaces, ultimately leading to more accurate predictions and deeper understanding of molecular behavior.

Breakdown of the Mean-Field Approximation

Mean-field theory (MFT) represents a foundational approximation approach for tackling complex many-body problems across physics, chemistry, and beyond. Its core principle involves replacing all intricate interactions between a body and its many neighbors with a single, averaged, or effective interaction, thereby reducing an intractable high-dimensional problem to a more manageable one-body problem [18]. In quantum chemistry and materials science, this concept materializes in the Hartree-Fock (HF) method and its extensions, where each electron is considered to move independently within an average field generated by all other electrons. While this approximation offers tremendous computational advantages and often provides a valuable first approximation, its breakdown in systems with strong correlations presents a significant challenge, particularly in the study of complex transition metal systems such as iron-sulfur clusters [19] [15].

The formal validity of MFT is governed by the nature of fluctuations and dimensionality. Heuristically, if a particle experiences many random interactions, they tend to cancel out, making the mean effective interaction a good approximation. This is often true in high-dimensional systems or those with long-range forces [18]. However, the Ginzburg criterion formally expresses how fluctuations can render MFT a poor approximation, particularly in low-dimensional systems or near critical points [18]. In the context of electronic structure theory, these "fluctuations" translate to strong electron correlation, a regime where the mean-field assumption of independent electron motion fails catastrophically. This whitepaper details the theoretical origins of this breakdown, its manifestation in iron-sulfur cluster research, and the advanced methodologies developed to move beyond the mean-field approximation.

Theoretical Foundations of Mean-Field Breakdown

Formal Basis and the Bogoliubov Inequality

The formal basis for MFT is often derived from the Bogoliubov inequality, which provides a variational principle for bounding the free energy of a system. For a Hamiltonian ( \mathcal{H} = \mathcal{H}0 + \Delta \mathcal{H} ), the free energy ( F ) satisfies ( F \leq F0 \equiv \langle \mathcal{H} \rangle0 - T S0 ), where ( F0 ) is the free energy of a simpler, tractable Hamiltonian ( \mathcal{H}0 ), and ( S0 ) is the corresponding entropy [18]. The mean-field approximation is obtained by choosing a non-interacting ( \mathcal{H}0 ) and optimizing this upper bound. Consequently, MFT is inherently a zeroth-order expansion of the Hamiltonian in fluctuations, and its accuracy depends on the smallness of these fluctuations [18].

Table: Key Concepts in Mean-Field Theory Formalisms

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Bogoliubov Inequality | ( F \leq \langle \mathcal{H} \rangle0 - T S0 ) | Variational principle justifying MFT; MFT provides an upper bound for the true free energy. |

| Mean-Field Hamiltonian | ( \mathcal{H}0 = \sum{i=1}^N hi(\xii) ) | Non-interacting reference system; degrees of freedom are decoupled. |

| Molecular Field | ( hi^{MF}(\xii) = \sum{{j}} \text{Tr}j V{i,j} P{0}^{(j)} ) | Effective field experienced by a single component due to the averaged influence of all others. |

| Ginzburg Criterion | N/A | Formal condition determining the spatial dimension and parameter range below which MFT fails due to fluctuations. |

The Correlation Problem and Its Physical Manifestations

The primary source of mean-field breakdown is the neglect of correlations. In HF theory, the wavefunction is modeled as a single Slater determinant, which is exact for a system of non-interacting particles. This description fails to account for the correlated motion of electrons that minimizes their Coulomb repulsion. In strongly correlated systems, the true ground state wavefunction is a quantum superposition of multiple Slater determinants with similar weights. A single determinant is a qualitatively poor starting point in such cases, leading to severe errors in predicted energies, spin densities, and other properties [15]. This "static correlation" or "near-degeneracy" problem is endemic in systems with partially filled d- or f-orbitals, such as transition metal complexes, where multiple electronic configurations are close in energy.

The Specific Challenge of Iron-Sulfur Clusters

Electronic Structure and Multi-Reference Character

Iron-sulfur clusters are ubiquitous metallocofactors in biology, essential for electron transfer, catalysis, and regulatory functions [20]. A common motif is the [4Fe-4S] cluster, a cubane-like structure of four iron and four sulfur atoms, typically ligated by cysteine residues from the protein scaffold [20]. These clusters are paradigm examples of strongly correlated electron systems. The iron sites are typically in a high-spin state, and the presence of multiple metal centers with direct metal-metal bonding interactions through bridging sulfurs leads to a complex electronic landscape with many low-lying spin states [19] [15].

The [4Fe-4S] cluster in its common 2+ oxidation state contains two ferric (Fe³⁺) and two ferrous (Fe²⁺) ions, but the valence is delocalized over mixed-valence pairs (Fe²˙⁵−Fe²˙⁵), resulting in a net spin S = 0 ground state [20]. This electron delocalization and antiferromagnetic coupling between the iron sites creates a quantum-mechanical state that cannot be described by a single electronic configuration where electrons are assigned to specific atoms. The true ground state is a linear combination of multiple configurations, a situation where single-reference HF theory is fundamentally inadequate.

Convergence Pathologies in Self-Consistent Field Procedures

The application of standard mean-field methods to iron-sulfur clusters is plagued by SCF convergence challenges. The presence of many near-degenerate states leads to a complex electronic energy landscape with multiple local minima [15]. Standard SCF algorithms based on Fock matrix diagonalization can oscillate between these states or converge to an unphysical saddle point rather than the true energy minimum.

Recent research highlights that even advanced open-shell methods like Restricted Open-Shell Hartree-Fock (ROHF) face significant hurdles. As noted in recent work, "optimizing a low-spin configuration using self-consistent field (SCF) theory has been a long-standing challenge, since each orbital must be an eigenfunction of a different Fock operator" [15]. Furthermore, computational studies reveal that "solutions with unpaired electrons localized in Fe 3d orbitals (which might be predicted from chemical intuition) are not necessarily local minima for all CSF spin states," indicating the rugged and non-intuitive nature of the potential energy surface for these systems [15].

Advanced Methodologies Beyond Standard Mean-Field

Cluster Mean-Field and Linear Combination Approaches

To address the limitations of single-site mean-field theory, Cluster Mean-Field (cMF) theory has been developed. In cMF, the system is partitioned into small fragments or clusters. The wavefunction is expressed as a factorized tensor product of optimized cluster states, thereby including all electron correlations within each cluster but neglecting correlations between clusters [19]. This approach provides a more nuanced framework than HF, as it can capture local strong correlations exactly.

A recent innovation, Linear Combination of cMF (LC-cMF), further advances this concept by combining wavefunctions from different cluster tilings of the lattice. This creates a non-orthogonal configuration interaction that alleviates the dependence of the results on a single, arbitrary choice of cluster partitioning [19]. Benchmark calculations on the challenging ( J1 )-( J2 ) Heisenberg model—a proxy for frustrated magnetic systems like certain iron-sulfur clusters—show that LC-cMF provides a "semi-quantitative description" in the highly frustrated regime (( 0.4 \lessapprox J2/J1 \lessapprox 0.6 )), which is notoriously difficult for other methods [19].

Table: Beyond-Mean-Field Computational Methods for Strong Correlation

| Method | Core Idea | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Mean-Field (cMF) | Partition system into clusters; correlate electrons within but not between clusters. | Captures local correlations; more flexible than HF; lower cost than full CI. | Sensitivity to cluster size and shape; misses inter-cluster correlations. |

| LC-cMF | Linear combination of cMF states with different cluster tilings. | Reduces tiling-dependence; improves accuracy for frustrated systems. | Higher computational cost than single-tile cMF. |

| Configuration State Function (CSF) ROHF | Uses a single CSF with localized orbitals as a reference for low-spin states. | Conserves spin symmetry; compact representation for antiferromagnetic states. | Challenging orbital optimization; multiple local minima possible. |

| Broken-Symmetry DFT (BS-DFT) | Uses a single Slater determinant that breaks spin symmetry to estimate energy of low-spin state. | Low cost; practical for large systems; often good qualitative insights. | Spin contamination; results can be method-dependent; artificial symmetry breaking. |

Configuration State Functions and Geometric Direct Minimization

For open-shell systems like iron-sulfur clusters, an alternative to the multi-cluster approach is to use a single Configuration State Function (CSF) built from localized molecular orbitals. A CSF is a spin-adapted linear combination of Slater determinants that is an eigenfunction of the total spin operators ( \hat{S}^2 ) and ( \hat{S}_z ) [15]. This approach can provide a compact reference for antiferromagnetic states.

However, optimizing the orbitals for a low-spin CSF is difficult. A recent breakthrough, the CSF-based Geometric Direct Minimization (CSF-GDM) algorithm, addresses this by employing quasi-Newton Riemannian optimization on the orbital constraint manifold. This provides robust convergence to a local energy minimum, a significant improvement over traditional Fock-diagonalization-based ROHF algorithms [15]. This tool has enabled the systematic exploration of the electronic energy landscape of iron-sulfur clusters, revealing the existence of "many local CSF energy minima" [15].

Experimental Protocols for Probing Mean-Field Breakdown

Protocol: Assessing Multi-Reference Character via CSF-GDM

Objective: To identify the optimal CSF reference and characterize the local minima landscape for an iron-sulfur cluster.

- Initial Setup: Select a spin-coupling pattern consistent with the expected antiferromagnetic ordering in the [4Fe-4S] cluster. Generate an initial guess using localized fragment orbitals.

- Wavefunction Optimization: Employ the CSF-GDM algorithm [15] to minimize the ROHF energy. The Riemannian optimizer ensures convergence to a local minimum even with near-degeneracies.

- Landscape Mapping: Repeat the optimization from multiple, randomly perturbed initial orbital guesses. This helps map the various local minima on the electronic energy surface.

- Analysis: Compare the energies and physical properties (e.g., spin densities, orbital localization) of the converged solutions. The solution with the lowest energy is the global minimum for that specific CSF ansatz. The presence of multiple low-lying minima with distinct properties is a direct signature of strong correlation and mean-field breakdown.

Protocol: Calculating Redox Potentials with Beyond-Mean-Field Methods

Objective: To compute the relative midpoint potentials ((E_m)) of the FX, FA, and FB clusters in Photosystem I, where mean-field methods like HF are insufficient.

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the crystal structure (e.g., PDB: 1JB0). Add missing atoms and residues, solvate the system in a water box, and add counterions to achieve neutrality [20].

- Electronic Structure Calculation: For each iron-sulfur cluster in its oxidized and reduced states, perform a single-point energy calculation using a method that handles correlation and spin, such as Broken-Symmetry Density Functional Theory (BS-DFT) [20]. BS-DFT is a practical, albeit approximate, method for treating antiferromagnetic coupling in these systems.

- Continuum Electrostatics: Use a method like Multi-Conformer Continuum Electrostatics (MCCE) [20] to compute the solvation and protein environment effects on the energy. This step incorporates the electrostatic influence of the protein matrix, which is critical for accurate potential prediction.

- Potential Calculation: The midpoint potential is computed as ( Em = -\frac{\Delta G}{nF} + E{ref} ), where (\Delta G) is the free energy change of reduction, (n) is the number of electrons, (F) is Faraday's constant, and (E_{ref}) is a reference electrode potential. The strong pairwise electrostatic interactions with surrounding residues, particularly ligating cysteines and backbone atoms, are key determinants of the relative potentials [20].

Diagram: Workflow for Calculating Redox Potentials in Iron-Sulfur Clusters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Investigation |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Crystal Structures (e.g., PDB: 1JB0) | Provides the atomic-level structural model essential for any computational study, defining the protein environment and ligand geometry around the metal clusters [20]. |

| Parameterized Molecular Potentials (e.g., AMBER) | Defines the force field for classical energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations, preparing a stable initial structure for quantum calculations [20]. |

| Cluster Mean-Field (cMF) Code | Software implementation that enables the system to be divided into correlated fragments, going beyond single-site mean-field to capture local correlations [19]. |

| Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) Algorithm | Advanced optimizer that ensures robust convergence of the wavefunction to a local minimum, crucial for challenging open-shell systems like iron-sulfur clusters [15]. |

| Broken-Symmetry DFT (BS-DFT) | A practical computational workhorse that allows for a qualitative description of antiferromagnetic coupling and redox properties in large metalloprotein systems [20]. |

| Multi-Conformer Continuum Electrostatics (MCCE) | A computational methodology that classically computes the effect of the protein and solvent environment on redox potentials and pKa values, critical for biological relevance [20]. |

The breakdown of the mean-field approximation is not a mere theoretical curiosity but a central challenge in modern computational chemistry, particularly in the study of biologically essential iron-sulfur clusters. This failure stems from the intrinsic strong electron correlations, multi-reference character, and complex antiferromagnetic coupling present in these systems. The pathologies of SCF convergence are direct manifestations of an underlying electronic structure that is incompatible with a single-determinant description.

Addressing this challenge requires a move beyond standard Hartree-Fock theory. The field is advancing through innovative methods like cluster mean-field theory, linear combinations of cMF states, and robust optimization of spin-adapted configuration state functions. These approaches, coupled with practical tools like broken-symmetry DFT and continuum electrostatics, provide a powerful, multi-faceted toolkit for probing the electronic properties of these complex systems. Understanding and overcoming the mean-field breakdown is thus pivotal for accurately modeling iron-sulfur clusters and advancing our knowledge of their critical role in bioenergetics and catalysis.

Near-Degenerate Configurations and Complex Spin Alignment

Electronic Structure and Theoretical Background

Iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters are ubiquitous inorganic cofactors that perform a wide variety of essential reactions, from electron transport to enzyme catalysis, in virtually all living organisms [21] [22]. Their unique reactivity is rooted in their rich electronic structures, which differ significantly from the active sites of mononuclear iron enzymes [21]. Foundational to their chemical behavior are two key phenomena: superexchange antiferromagnetic coupling and spin-dependent electron delocalization (double-exchange) [21].

The electronic description of Fe-S clusters begins with their composition, which typically involves high-spin tetrahedral Fe²⁺ (S=2) and Fe³⁺ (S=5/2) ions bridged by inorganic sulfide ions (S²⁻) [21]. In biological systems, the most common structural motifs include [2Fe-2S], open-cuboidal [Fe3S4], and cuboidal [Fe4S4] clusters, which are often ligated by protein-derived amino acids, most commonly cysteine thiolates [21].

Antiferromagnetic Coupling and Superexchange

The interaction between adjacent iron sites via bridging sulfides leads to strong antiferromagnetic coupling. This phenomenon is generally described using the Heisenberg-Dirac-van Vleck Hamiltonian:

[ \widehat{H}{Heis} = J \overrightarrow{S}1 \cdot \overrightarrow{S}_2 ]

where ( J ) is the exchange coupling constant. For this formulation, positive values of ( J ) indicate antiferromagnetic coupling, which favors spin anti-alignment and low overall spin states [21]. The energy of a given total spin state ( S ) is given by:

[ E = \frac{J}{2} S(S+1) ]

with the possible values of the total spin ( S ) constrained by the triangle inequality ( |S1 - S2| \le S \le |S1 + S2| ) [21]. In cuboidal [Fe₄S₄]ⁿ⁺ clusters, this coupling typically results in ground states with total spin S=0 for the [Fe₄S₄]²⁺ oxidation state and S=1/2 for the [Fe₄S₄]¹⁺/³⁺ states [21].

Spin-Dependent Electron Delocalization (Double-Exchange)

Simultaneously, Fe-S clusters exhibit spin-dependent electron delocalization, where electrons can hop between iron sites of differing valence (Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ pairs) [21]. This double-exchange mechanism favors ferromagnetic alignment and high spin states, creating a complex energy landscape where antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic tendencies compete. It is this competition, combined with the presence of multiple nearly degenerate electronic configurations, that gives rise to the challenging electronic structure of Fe-S clusters, particularly at physiologically relevant temperatures where numerous electronic excited states are thermally populated [21].

Table 1: Common Iron-Sulfur Cluster Types and Their Electronic Properties

| Cluster Type | Common Oxidation States | Typical Ground Spin State | Key Electronic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2Fe-2S] | 1+, 2+ | Mixed-valence pairs | Antiferromagnetic coupling between Fe sites |

| [Fe₃S₄] | 0, 1+ | Complex spin ladder | Open structure with delocalized electrons |

| [Fe₄S₄] (Fd-type) | 1+, 2+ | S=1/2, S=0 | Two Fe²⁺, two Fe³⁺ ions in cuboidal structure |

| [Fe₄S₄] (HiPIP-type) | 2+, 3+ | S=0, S=1/2 | Mixed valence delocalization over four sites |

Figure 1: Competing electronic interactions in iron-sulfur clusters leading to near-degeneracy and SCF convergence challenges. Antiferromagnetic superexchange and ferromagnetic double-exchange create competing energy states.

SCF Convergence Challenges and Computational Methodologies

The complex electronic structure of Fe-S clusters presents significant challenges for Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence in computational chemistry calculations. The near-degeneracy of multiple electronic configurations and the competition between different spin alignments mean that modern SCF algorithms often struggle to find a stable converged solution [5].

Root Causes of Convergence Failure

For iron-sulfur clusters specifically, convergence difficulties arise from several interconnected factors:

- Open-Shell Transition Metal Character: The presence of multiple open-shell iron centers with unpaired electrons creates a complex potential energy surface with many local minima [5].

- Near-Degenerate States: The energy separation between different spin configurations is often small compared to the convergence criteria of standard SCF procedures [21].

- Spin Contamination: The tendency for unrestricted calculations to experience significant spin contamination makes it difficult to converge to a pure spin state.

- Broken-Symmetry Solutions: The search for broken-symmetry solutions, which are essential for properly describing antiferromagnetically coupled systems, introduces additional instability into the SCF process.

Practical SCF Convergence Protocols

When standard SCF procedures fail for Fe-S clusters, the following methodologies have proven effective, particularly within the ORCA computational chemistry package [5] [23]:

Initial Steps:

- Increase Maximum Iterations: For calculations showing signs of convergence, simply increasing the maximum SCF iterations can help:

%scf MaxIter 500 end[5]. - Utilize TRAH Algorithm: The Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) approach in ORCA is a robust second-order converger that activates automatically when the regular DIIS-based SCF struggles. Manual control is possible via: [5]

Advanced Strategies for Pathological Cases: For particularly challenging Fe-S cluster systems, the following combination of settings often succeeds where standard approaches fail [5]:

This combination employs strong damping (!SlowConv), allows for a very high number of iterations, increases the number of Fock matrices remembered for DIIS extrapolation, and reduces numerical noise by frequently rebuilding the Fock matrix [5].

Alternative Pathway: If the above approach remains ineffective, these additional strategies may help:

- Converge a simpler method (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP) and read the orbitals as a guess using

! MORead[5]. - Converge a closed-shell oxidized state and use its orbitals as a starting point for the target system [5].

- Use the KDIIS algorithm with SOSCF:

! KDIIS SOSCF, potentially with delayed SOSCF startup for transition metal complexes [5].

Table 2: SCF Convergence Thresholds for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Calculations

| Convergence Criterion | LooseSCF | NormalSCF (Default) | TightSCF (Recommended) | VeryTightSCF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TolE (Energy Change) | 1e-5 | 1e-6 | 1e-8 | 1e-9 |

| TolRMSP (RMS Density) | 1e-4 | 1e-6 | 5e-9 | 1e-9 |

| TolMaxP (Max Density) | 1e-3 | 1e-5 | 1e-7 | 1e-8 |

| TolErr (DIIS Error) | 5e-4 | 1e-5 | 5e-7 | 1e-8 |

| TolG (Orbital Gradient) | 1e-4 | 5e-5 | 1e-5 | 2e-6 |

| Recommended Use Case | Preliminary scans | Standard organic molecules | Transition metal complexes | Final single-point energies |

Figure 2: Systematic protocol for addressing SCF convergence challenges in iron-sulfur cluster calculations, progressing from simple to advanced strategies.

Experimental Characterization and Validation

Computational predictions of electronic structure require validation through experimental techniques capable of probing the electronic and magnetic properties of Fe-S clusters. Several spectroscopic methods have proven particularly valuable for this purpose.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

XAS is an element-specific technique that uses synchrotron radiation to probe the electronic, structural, and magnetic properties of specific elements in materials [24]. The method measures the X-ray absorption coefficient µ as a function of incident X-ray energy near and above the core-level binding energies of a particular atom [24]. Key aspects include:

- Element Specificity: The element to probe is selected by tuning the X-ray energy to an appropriate absorption edge [24].

- Information Content: XAS provides data on oxidation states, coordination chemistry, and electronic structure [24].

- Experimental Setup: Measurements typically require synchrotron radiation sources to obtain intense, tunable X-ray beams across a broad energy spectrum [24].

The absorption process follows Beer's Law: [ I = I0 e^{-\mu t} ] where ( I0 ) is the incident X-ray intensity, ( t ) is the sample thickness, and ( I ) is the transmitted intensity [24].

Additional Spectroscopic Methods

Other crucial techniques for characterizing Fe-S cluster electronic structure include:

- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR): Historically fundamental to Fe-S cluster research, with Beinert's 1960 observation of novel signals in reduced, non-heme iron enzymes marking a key early development [21].

- Mössbauer Spectroscopy: Provides information on oxidation states, spin states, and electronic environments of iron nuclei [21].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Can probe the electronic structure through hyperfine interactions, with early studies contributing significantly to understanding clostridial ferredoxins [21].

Experimental Workflow for Electronic Structure Analysis

A comprehensive approach to validating computational predictions of near-degenerate states involves:

- Sample Preparation: Purified Fe-S cluster proteins or synthetic analogues under controlled anaerobic conditions to prevent oxidative degradation [25].

- Multi-Technique Data Collection: Concurrent application of XAS, EPR, and Mössbauer spectroscopy to obtain complementary electronic structure information.

- Variable-Temperature Measurements: Characterization across a temperature range to probe thermally accessible excited states [21].

- Computational-Experimental Correlation: Direct comparison of experimental spectra with those predicted from converged computational models.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synchrotron Radiation | X-ray source for XAS measurements | Broad spectrum of energies (1000+ eV) needed for absorption edges [24] |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Oxygen-free sample environment | Prevents cluster degradation during preparation [25] |

| Cysteine Desulfurase (NFS1) | Provides inorganic sulfur during cluster biogenesis | Forms persulfide intermediate on Cys381 [22] |

| Scaffold Protein (ISCU) | Platform for de novo [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly | Cys138 receives persulfide sulfur from NFS1 [22] |

| Frataxin (FXN) | Enhances sulfur transfer to ISCU | Facilitates conformational change in NFS1 [22] |

| ISD11 (LYRM4) | Stabilizes cysteine desulfurase NFS1 | Accessory protein essential for NFS1 function [22] |

| Acyl-Carrier Protein (ACP/NDUFAB1) | Component of initial core biosynthetic complex | Binds ISD11 in Fe-S cluster assembly machinery [22] |

Computational Strategies: From Broken-Symmetry DFT to Advanced Wavefunction Methods

Spin-Flip and ModifyStartPotential Approaches in ADF

Iron-sulfur clusters, particularly the ubiquitous [4Fe-4S] cores found in numerous metalloproteins, present significant challenges for electronic structure calculations using density functional theory (DFT). These systems exhibit multi-center radical character where the relative alignment of individual iron site spins dramatically influences the computed electronic structure and properties. The self-consistent field (SCF) convergence process for these complexes is notoriously difficult due to the presence of multiple nearly degenerate electronic states with different spin couplings, often leading to convergence to unphysical states or complete SCF failure. Within the Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF) package, two specialized approaches have been developed to address these challenges: the SpinFlip method and the ModifyStartPotential option. These techniques enable researchers to guide the SCF process toward specific spin-coupled solutions that correspond to physically meaningful states, particularly the broken-symmetry (BS) configurations essential for properly describing the antiferromagnetic couplings in iron-sulfur clusters [14].

The fundamental challenge stems from the electronic structure of [4Fe-4S] clusters, where iron sites can exist in high-spin ferrous (Fe^3+^, S = 5/2) or ferric (Fe^2+^, S = 2) states. For the oxidation level occurring in proteins like rubredoxin and high-potential iron-sulfur proteins (HIPIPs), the cluster contains two ferrous and two ferric ions with a total charge of -2. The antiferromagnetic coupling between these sites creates a complex potential energy surface where the high-spin (HS) state with all spins parallel often converges readily, while the lower-energy broken-symmetry states with anti-parallel spin alignments prove difficult to stabilize during SCF iterations [14]. This tutorial explores the two primary methods in ADF for overcoming these challenges, providing researchers with practical tools for investigating iron-sulfur clusters and similar multi-center radical systems.

Theoretical Foundation of Spin Coupling Methods

Electronic Structure of Iron-Sulfur Clusters

Iron-sulfur clusters in their [4Fe-4S] form exhibit complex electronic behavior due to the presence of multiple transition metal centers with unpaired electrons. The iron sites are typically high-spin, with ferrous ions (Fe^3+^) having S = 5/2 and ferric ions (Fe^2+^) having S = 2. The resulting spin couplings between these centers determine the overall electronic ground state and properties of the cluster. For the biologically relevant oxidation state with total charge -2, the system contains two ferrous and two ferric ions, creating a complex spin landscape where antiferromagnetic couplings often dominate [14].

The Heisenberg-Dirac-van Vleck (HDvV) Hamiltonian provides the theoretical framework for understanding these exchange interactions:

[ \hat{H} = \sum{j>i=1}^{4} J{ij} \hat{S}i \cdot \hat{S}j ]

where (J{ij}) represents the exchange coupling constants between sites i and j, and (\hat{S}i) are the spin operators. When (J{ij} > 0), the interaction is antiferromagnetic, favoring antiparallel spin alignment, while (J{ij} < 0) indicates ferromagnetic coupling favoring parallel alignment. In typical [4Fe-4S] clusters, a combination of strong antiferromagnetic couplings between certain sites and weaker ferromagnetic couplings between others creates the potential energy landscape that makes SCF convergence challenging [26].

Broken-Symmetry Approach in DFT

The broken-symmetry (BS) approach in DFT represents a practical methodology for describing antiferromagnetic coupling in multi-center systems without the need for computationally expensive multi-determinant methods. This approach utilizes a single determinant where different magnetic centers are assigned different spin projections (α or β), effectively mimicking the antiferromagnetic state. While this wavefunction is not a pure spin eigenstate, it provides a reasonable approximation for calculating energies and properties of antiferromagnetically coupled systems [26].

In ADF, the BS solutions are obtained through two primary methods: the SpinFlip technique, which modifies a converged high-spin solution, and the ModifyStartPotential approach, which directly initializes a specific spin arrangement at the start of the SCF process. Both methods address the core challenge that the BS solution often exists at an energy minimum that is difficult to locate through standard SCF procedures starting from atomic superposition or default initial guesses [14].

Table 1: Key Electronic Structure Concepts for Iron-Sulfur Clusters

| Concept | Description | Significance in [4Fe-4S] Clusters |

|---|---|---|

| High-Spin (HS) State | All iron site spins aligned parallel | S = 9 for [Fe₄S₄(SH)₄]²⁻; easier SCF convergence |

| Broken-Symmetry (BS) State | Antiferromagnetic coupling with antiparallel spins | Lower energy than HS; physically correct description |

| Spin Polarization | Difference between α and β electrons | Controlled by SpinPolarization key in ADF |

| Local Spins | Individual metal center spin states | Fe³⁺: S = 5/2; Fe²⁺: S = 2 |

| Exchange Coupling Constants (J) | Measure of spin-spin interaction strength | Determines overall magnetic behavior |

The SpinFlip Methodology

Theoretical Basis of SpinFlip

The SpinFlip approach implements a two-step procedure originally introduced by Noodleman and coworkers for generating broken-symmetry solutions from converged high-spin calculations. The fundamental principle relies on first obtaining the SCF solution for the ferromagnetic state where all site spins are aligned parallel (all α spins), which typically converges readily due to the unambiguous spin alignment. Subsequently, the α and β electron densities centered at specific sites targeted for antiferromagnetic coupling are exchanged, and the calculation is restarted from this modified electron density [14].

This spin flipping procedure effectively transforms the high-spin |4↑:0↓⟩ configuration into various broken-symmetry states such as |2↑:2↓⟩ by inverting the spin projection on selected metal centers. The resulting BS state often corresponds to a lower energy electronic state that properly represents the antiferromagnetic couplings present in the system. However, because this approach typically lowers the electronic symmetry of the system while retaining structural symmetry, the resulting solution is referred to as a broken-symmetry state [14].

Practical Implementation of SpinFlip

The implementation of SpinFlip in ADF requires careful preparation and execution. The step-by-step methodology for a typical [4Fe-4S] system is as follows:

Obtain High-Spin Solution: First, converge an unrestricted calculation for the high-spin state with all spins aligned. For [Fe₄S₄(SH)₄]²⁻, this corresponds to a spin polarization of 18 (S = 9), calculated as 2 × 5/2 + 2 × 2 [14].

Configure BS Calculation: Create a new single-point calculation with the target BS spin polarization. For the |2↑:2↓⟩ state, this would be spin polarization 0 (S = 0) [14].

Set Restart Options: In the Restart panel (Model → Restart), specify the engine restart file from the high-spin calculation (typically