Comprehensive Guide to Coordination Complex Characterization: From Fundamental Analysis to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of characterization techniques for coordination compounds, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comprehensive Guide to Coordination Complex Characterization: From Fundamental Analysis to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of characterization techniques for coordination compounds, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers fundamental principles for structural elucidation, advanced methodological applications in drug discovery, troubleshooting for complex systems, and validation strategies for clinical translation. The content integrates traditional analytical methods with emerging computational and high-resolution imaging technologies, highlighting their crucial role in developing metal-based therapeutics, diagnostic agents, and functional materials for biomedical applications.

Core Principles and Essential Techniques for Initial Coordination Complex Characterization

Elemental Analysis and Atomic Absorption Spectrometry for Composition Verification

Elemental analysis is a cornerstone technique in the characterization of coordination complexes, providing essential data on metal content and stoichiometry that confirms complex identity, purity, and composition. For researchers and drug development professionals working with metal-containing compounds, verifying the presence and concentration of specific metal atoms within molecular structures is critical for ensuring compound integrity, understanding structure-activity relationships, and meeting regulatory requirements. Within the analytical toolkit, Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) represents a well-established technique valued for its sensitivity and specificity for metal analysis, though alternative technologies offer complementary capabilities.

This guide objectively compares the performance of AAS with other elemental analysis techniques, focusing on their application in verifying the composition of coordination complexes and pharmaceutical compounds. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical considerations to inform technique selection for research and development applications.

Core Principles of Atomic Absorption Spectrometry

Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) determines elemental concentration by measuring the absorption of light at specific wavelengths by free, ground-state atoms in a gaseous state [1]. When a sample is introduced into a flame or graphite furnace, the analyte is atomized, and the resulting atoms absorb light from a source (a hollow cathode lamp) tuned to elementspecific wavelengths. The amount of light absorbed is directly proportional to the concentration of the metal element in the sample according to the Beer-Lambert Law [1].

The two primary atomization techniques in AAS offer different sensitivity profiles:

- Flame AAS (FAAS): A liquid sample is aspirated into a flame (typically air-acetylene or nitrous oxide-acetylene), where it is desolvated, vaporized, and atomized. FAAS is robust and cost-effective for analyzing elements at parts-per-million (ppm) concentrations [1] [2].

- Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS): A small sample aliquot is placed in a graphite tube that is electrically heated through a temperature program (drying, ashing, atomization). GFAAS offers significantly higher sensitivity, enabling detection at parts-per-billion (ppb) levels, making it suitable for trace element analysis [1] [2].

Specialized techniques like Hydride Generation AAS (HGAAS) for elements like arsenic and selenium, and Cold Vapor AAS (CVAAS) for mercury, enhance sensitivity and selectivity for these specific elements [2].

Comparative Analysis of Elemental Analysis Techniques

Performance Comparison: AAS vs. ICP-OES vs. ICP-MS

The selection of an elemental analysis technique involves balancing sensitivity, throughput, multi-element capability, and cost. The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of AAS compared to Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

Table 1: Technique Comparison for Elemental Analysis [3] [4] [5]

| Factor | AAS | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Good for ppm levels (GFAAS: ppb) | Excellent for ppb levels | Exceptional for ppt levels |

| Detection Limits | ~ppm (FAAS), ~ppb (GFAAS) | Parts-per-billion (ppb) | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) |

| Sample Throughput | Low (sequential single-element analysis) | High (simultaneous multi-element) | High (simultaneous multi-element) |

| Multi-Element Capability | Limited (typically single element) | Excellent (multiple elements simultaneously) | Excellent (multiple elements simultaneously) |

| Sample Versatility | Simple matrices (e.g., solutions) | Complex matrices (e.g., biofluids, wastewater) | Complex matrices |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Narrow (~2-3 orders of magnitude) | Wide (~4-6 orders of magnitude) | Very Wide (~8-9 orders of magnitude) |

| Initial Instrument Cost | Lower ($10,000 - $95,000) [3] [2] | Medium ($46,000 - $170,000) [3] [5] | High ($150,000 - $500,000+) [3] [5] |

| Operational Complexity | Low (well-established, simple workflows) | Medium (requires skilled operation) | High (requires highly skilled operation) |

Key Interpretations:

- Choose AAS for labs with a focused need to quantify one or a few specific metals in simple matrices, with budget constraints and lower sample volumes. It is a robust and cost-effective technology for routine analysis [5].

- Choose ICP-OES or ICP-MS for high-throughput laboratories requiring comprehensive multi-element profiling, analysis of complex sample matrices, or ultra-trace level detection, particularly in advanced pharmaceutical and environmental applications [4] [5]. ICP-MS is the gold standard for the highest sensitivity needs [5].

Supporting Experimental Data: Digestion Method Recovery Rates

Sample preparation is critical for accurate analysis. A comparative study of digestion methods for soil elemental analysis using AAS provides relevant recovery data, illustrating how methodology impacts results. While the matrix differs from pharmaceutical compounds, the principles of digestion efficiency are analogous.

Table 2: Percentage Recovery of Heavy Metals at 10 ppm Spike Level Using Different Digestion Methods [6]

| Digestion Method | Ni | Pb | Cu | Cd | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqua Regia (HCl + HNO₃) | 85.2 | 89.5 | 88.1 | 94.3 | 92.7 |

| Aqua Regia + Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ | 82.7 | 86.3 | 85.4 | 90.1 | 89.5 |

| HF + HClO₃ | 80.1 | 82.8 | 81.9 | 85.6 | 87.2 |

| HClO₃ + H₂SO₄ | 78.5 | 79.4 | 78.8 | 82.3 | 84.9 |

| HClO₃ + HNO₃ + HF | 83.5 | 87.2 | 85.9 | 91.5 | 90.8 |

The study concluded that Aqua Regia consistently showed high recovery rates for several metals, particularly at lower concentrations, making it a robust choice for extracting a wide range of metals [6]. The addition of sulfuric acid generally reduced recovery slightly. This highlights the importance of matching the digestion protocol to the target elements and sample matrix.

Experimental Protocols for AAS in Pharmaceutical Research

Protocol 1: Quantification of a Metal-Containing Antibiotic

Objective: To determine the concentration of a metal (e.g., Zn, Cu) in a synthesized metallo-antibiotic drug substance [7] [8].

Sample Preparation:

- Weighing: Accurately weigh a representative sample of the pharmaceutical product (~0.1 - 0.5 g) into a clean digestion vessel.

- Digestion: Add 5-10 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃) and heat on a hot plate (~100-150°C) until the sample is completely dissolved and fumes are clear. For resistant organics, a mixture of HNO₃ and HCl (Aqua Regia) or HClO₄ may be required [6] [1].

- Dilution: After cooling, quantitatively transfer the digestate to a volumetric flask and dilute to volume with deionized water. Ensure the final acid concentration is <10% v/v.

- Filtration (optional): Filter the solution if particulate matter is present to prevent nebulizer clogging [1].

Instrumental Analysis (GFAAS recommended for trace levels):

- Calibration: Prepare a series of standard solutions (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 50 ppb) from a certified stock solution of the target metal. Include a matrix modifier if necessary (e.g., Pd/Mg for volatile elements).

- Furnace Program: Set the temperature program for the graphite furnace:

- Drying: ~100-130°C (ramp, hold) to remove solvent.

- Ashing: ~300-700°C (ramp, hold) to remove organic matrix.

- Atomization: ~2000-2500°C (max power, hold) to atomize the analyte.

- Cleaning: ~2600°C (ramp, hold) to clean the tube.

- Analysis: Inject a precise aliquot (e.g., 20 µL) of each standard and sample into the graphite tube. Measure the peak area absorbance.

- Quantification: Construct a calibration curve of absorbance versus concentration and determine the unknown sample concentration from the curve [1].

Protocol 2: Studying Metal Uptake in Bacterial Cells

Objective: To quantify the accumulation of an antibiotic metal (e.g., Pt, Ag) in bacterial cells to elucidate modes of action or resistance mechanisms [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Incubation: Expose bacterial cultures to the metal-containing drug under study and appropriate controls for a specified time.

- Harvesting: Centrifuge the culture to pellet the bacterial cells. Wash the pellet 2-3 times with a buffer solution (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) to remove extracellular metal.

- Digestion: Transfer the washed cell pellet to a digestion tube. Add 1-2 mL of concentrated HNO₃ and digest as described in Protocol 1. Using a microwave-assisted digester is advantageous for complete digestion of cellular material.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Follow the GFAAS procedure from Protocol 1. The high sensitivity of GFAAS is required for the low metal concentrations expected in the small biomass samples.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the measured metal content to the cell count or protein content of the pellet to express uptake as metal per cell [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for AAS Sample Preparation and Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl, HF) | Digest organic matrices and dissolve target elements. | Essential to use trace metal grade to avoid sample contamination [1]. |

| Certified Elemental Standard Solutions | Used for instrument calibration and quality control. | Available as single-element or custom multi-element mixes from commercial suppliers. |

| Matrix Modifiers (e.g., Pd, Mg, NH₄⺠salts) | Stabilize volatile analytes during the GFAAshing stage. | Reduces loss of elements like Pb, Cd, As before atomization, improving accuracy [8]. |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) or Electrodeless Discharge Lamps (EDLs) | Provide element-specific light source for absorption measurement. | A dedicated lamp is required for each element analyzed [5]. |

| Graphite Furnace Tubes & Platforms | The sample containment and atomization device in GFAAS. | Consumable item; proper alignment and condition are critical for reproducible results. |

| Auto-sampler Tubes & Pipette Tips | For precise and automated sample introduction. | Must be clean and free of contaminants. |

| (D-Phe11)-Neurotensin | (D-Phe11)-Neurotensin Peptide | Research-grade (D-Phe11)-Neurotensin, a metabolically stable NT analog. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| (E)-4-Ethoxy-nona-1,5-diene | (E)-4-Ethoxy-nona-1,5-diene, MF:C11H20O, MW:168.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Decision Pathway

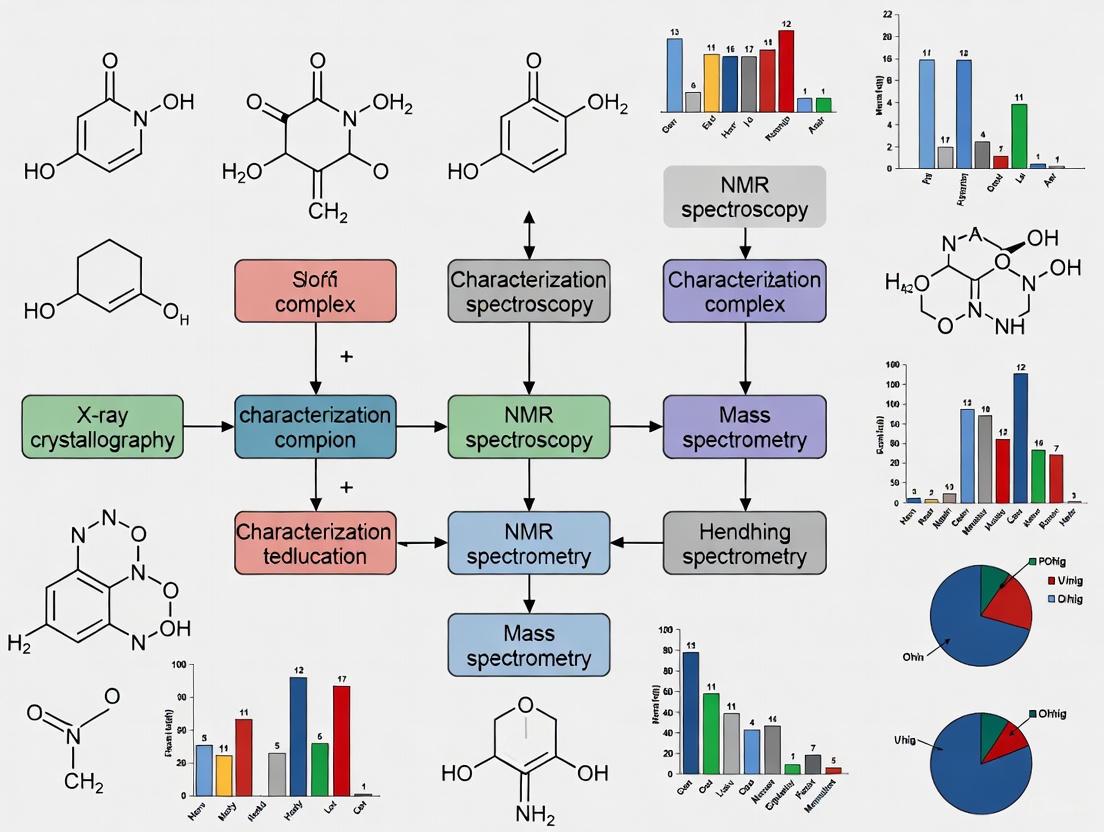

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for sample preparation and analysis via AAS, and the decision-making process for technique selection.

Diagram 1: AAS Workflow and Technique Selection

Atomic Absorption Spectrometry remains a vital technique for the specific and sensitive quantification of metal elements in coordination complexes and pharmaceuticals. Its strengths of high specificity for targeted elements, cost-effectiveness, and operational simplicity make it an excellent choice for many research and quality control laboratories. However, the choice of analytical technique must be guided by the specific research question. For comprehensive multi-element analysis, ultra-trace detection, or high-throughput needs, ICP-based techniques (ICP-OES and ICP-MS) offer superior capabilities, albeit at a higher cost and operational complexity. By understanding the comparative performance, optimal applications, and rigorous methodologies of each technique, scientists can effectively leverage elemental analysis to verify composition and advance their research in drug development.

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for characterizing metal-ligand interactions and coordination environments in diverse chemical and biological systems. This non-destructive method provides crucial information about molecular vibrations that are sensitive to changes in bond strength, coordination geometry, and ligand identity. In the context of coordination complex characterization, FTIR spectroscopy excels at identifying functional groups involved in metal binding, monitoring structural changes during complex formation, and providing insights into the electronic properties of metal centers through vibrational frequency shifts. The technique's versatility allows researchers to investigate systems ranging from simple inorganic complexes to sophisticated biological metal clusters, making it an indispensable tool in the analytical chemist's arsenal.

The fundamental principle underlying FTIR spectroscopy involves measuring the absorption of infrared radiation by molecular bonds, which occurs at characteristic frequencies corresponding to specific vibrational transitions. When ligands coordinate to metal centers, the electron density distribution within the ligand functional groups changes, leading to measurable shifts in vibrational frequencies and intensities. These spectral perturbations serve as fingerprints for identifying binding modes and assessing binding strength. Furthermore, the sensitivity of FTIR spectroscopy to the surrounding environment enables the study of metal-ligand interactions in various matrices, including solutions, solid states, and even within complex biological assemblies.

Fundamental Principles of Metal-Ligand Characterization by FTIR

Spectral Interpretation of Coordination Complexes

FTIR spectroscopy detects metal-ligand interactions through characteristic changes in the vibrational spectra of coordinating functional groups. When a ligand coordinates to a metal center, the electron density in its bonds is redistributed, leading to shifts in vibrational frequencies that can be monitored through infrared absorption. For example, coordination through carbonyl groups typically results in a decrease in the C=O stretching frequency due to back-donation of electron density from the metal to the π* orbital of the carbonyl group [9]. Similarly, coordination through amine groups produces detectable shifts in N-H bending vibrations. The extent of these frequency shifts provides qualitative information about bond strength and the nature of the metal-ligand interaction.

The interpretation of FTIR spectra relies on recognizing patterns associated with different coordination modes. Monodentate ligands often exhibit different spectral features compared to bidentate or bridging ligands. For instance, carboxylate groups can coordinate to metals in unidentate, bidentate, or bridging modes, each producing a distinct separation between the asymmetric (νas) and symmetric (νs) COO⻠stretching vibrations. The magnitude of Δν (νas - νs) serves as a diagnostic tool for determining coordination mode: unidentate coordination typically shows Δν values significantly larger than that of the free ion, while bidentate coordination shows similar or smaller Δν values [9]. This systematic approach to spectral interpretation enables researchers to deduce coordination geometry from FTIR data.

Comparison with Alternative Characterization Techniques

FTIR spectroscopy occupies a unique position among techniques for characterizing metal-ligand interactions, offering distinct advantages and limitations compared to other methods. The following table summarizes key comparative aspects:

Table 1: Comparison of FTIR with Other Techniques for Metal-Ligand Characterization

| Technique | Key Information Provided | Detection Limits | Sample Requirements | Advantages for Metal-Ligand Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Vibrational frequencies, binding modes, coordination geometry | ~0.1-1 mM (solution) | Minimal, various phases possible | Direct functional group monitoring, non-destructive, rapid measurement |

| X-ray Crystallography | Precise bond lengths/angles, coordination geometry | Single crystal | High-quality crystals required | Atomic-resolution structural information |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical environment, dynamics, binding constants | ~0.01-1 mM | Solution state preferred | Atomic-level resolution, quantitative binding affinities |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | d-d transitions, charge transfer bands, oxidation state | ~1-100 µM | Transparent solutions | Sensitive to electronic structure, concentration determination |

| Circular Dichroism | Chirality, absolute configuration | ~0.1-1 mM | Chiral compounds | Stereochemical information for chiral complexes |

FTIR spectroscopy complements other structural techniques by providing information about vibrational dynamics that may not be apparent from static structural methods like X-ray crystallography. While crystallography offers precise atomic coordinates, FTIR can reveal how metal-ligand bonds respond to energy input and can monitor reactions in real-time. Compared to NMR spectroscopy, FTIR generally has higher detection limits but can handle a wider range of sample conditions, including turbid suspensions and solid materials. The combination of FTIR with other spectroscopic methods often provides the most comprehensive understanding of metal-ligand systems.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Techniques for Different Systems

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality FTIR spectra of metal-ligand complexes. The choice of preparation method depends on the physical state of the sample and the specific information required. For solid coordination complexes, the pressed pellet technique using alkali halides such as KBr or CsI is most common. These materials are transparent to mid-IR radiation and allow for the creation of homogeneous disks containing approximately 1% of the sample by weight. KBr is widely used due to its broad transmission range (40,000-400 cmâ»Â¹), though it is hygroscopic and requires careful handling to avoid water absorption [10]. For samples sensitive to moisture or pressure, Nujol mulls (mineral oil suspensions) provide an alternative preparation method.

Solution-phase FTIR studies require specialized cells with IR-transparent windows appropriate for the solvent system. Common window materials include NaCl (40,000-625 cmâ»Â¹) for organic solvents, CaFâ‚‚ (70,000-1,110 cmâ»Â¹) for aqueous solutions, and ZnSe (10,000-550 cmâ»Â¹) for broader spectral ranges [10]. The pathlength of liquid cells must be optimized to balance sufficient signal intensity with avoidance of total absorption; typical pathlengths range from 0.1-1.0 mm for aqueous solutions. For air-sensitive complexes, sealed cells with appropriate windows enable the study of compounds under controlled atmospheres. Hydrated films, prepared by evaporating solvent from a solution of the complex on an IR-transparent window, offer another approach for studying biological macromolecules like proteins with bound metal ions [9].

Advanced FTIR Methodologies

Beyond conventional transmission FTIR, several advanced methodologies extend the application of infrared spectroscopy to challenging metal-ligand systems. Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FTIR allows for direct analysis of solid and liquid samples with minimal preparation, making it ideal for monitoring coordination reactions in real-time. The technique relies on the formation of an evanescent wave that penetrates a short distance into the sample in contact with a high-refractive-index crystal (e.g., diamond, ZnSe, or Ge). Synchrotron Radiation (SR)-FTIR microspectroscopy provides approximately 1000 times the brightness of standard globar sources, enabling high signal-to-noise ratio measurements at diffraction-limited spatial resolution (3-10 μm) [11]. This exceptional sensitivity makes SR-FTIR particularly valuable for studying heterogeneous samples or small areas within biological tissues containing metal cofactors.

Temperature-dependent FTIR studies provide insights into the thermodynamics of metal-ligand binding by monitoring spectral changes as a function of temperature. This approach has been successfully applied to measure relative energies of ligand binding conformations on nanocluster surfaces, revealing binding strength and conformational dynamics [12]. For protein-metal ion systems, difference spectroscopy involves subtracting the spectrum of the free protein from that of the metal-bound protein to highlight only the vibrations affected by metal binding [9]. This method minimizes interference from the large background absorption of the protein matrix, allowing specific metal-ligand interactions to be studied.

Research Applications in Coordination Chemistry

Biological Metal Cluster Characterization

FTIR spectroscopy has provided remarkable insights into the structure and function of biological metal clusters, particularly the Mnâ‚„CaOâ‚… cluster in Photosystem II that catalyzes water oxidation in photosynthesis. Studies over the past two decades have utilized FTIR to identify amino acid residues responsible for controlling the cluster's reactivity, delineate proton egress pathways, and characterize the influence of specific residues on water molecules that serve as substrate or participants in hydrogen bond networks [13] [14]. These investigations revealed that most protein ligands of the Mnâ‚„CaOâ‚… cluster are insensitive to Mn oxidations, while extensive networks of hydrogen bonds surround the cluster and modulate its catalytic activity [13].

The application of FTIR to biological metal clusters often involves monitoring light-induced changes through reaction-induced FTIR difference spectroscopy. This method captures subtle structural changes during catalytic turnover by comparing spectra collected before and after specific experimental perturbations. For the Mnâ‚„CaOâ‚… cluster, such approaches have identified a dominant proton egress pathway leading from the cluster to the thylakoid lumen and demonstrated that H-bond strengths of multiple water molecules change during the S state cycle of water oxidation [13]. These findings illustrate how FTIR can provide dynamic information about metal clusters that is complementary to the static structural data obtained from X-ray crystallography.

Protein-Metal Ion Interaction Studies

FTIR spectroscopy serves as a powerful tool for investigating interactions between metal ions and proteins, offering insights into binding sites, conformational changes, and binding affinities. Studies with bovine serum albumin (BSA) have demonstrated that metal ion binding produces measurable changes in the protein's amide I (C=O stretching, 1700-1600 cmâ»Â¹) and amide II (C-N stretching coupled to N-H bending, ~1550 cmâ»Â¹) bands [9]. The interaction is evidenced by significant reduction in spectral intensities of these bands after complexation with metal ions, accompanied by shifting of the amide I band from 1651 cmâ»Â¹ (free BSA) to higher or lower wavenumbers depending on the specific metal ion.

Table 2: FTIR Spectral Changes in BSA Upon Metal Ion Binding

| Metal Ion | Amide I Shift (cmâ»Â¹) | α-Helix Decrease (%) | Proposed Binding Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca²⺠| 1651 → 1653 | 12.9% | Interaction with carboxylate groups |

| Ba²⺠| 1651 → 1654 | 18.3% | Interaction with carboxylate groups |

| Ag⺠| 1651 → 1649 | 40.3% | Interaction with soft base sites |

| Ru³⺠| 1651 → 1655 | 33.8% | Coordination with N/O donors |

| Cu²⺠| 1651 → 1655 | 28.6% | Strong coordination preference |

| Co²⺠| 1651 → 1654 | 27.8% | Coordination with N/O donors |

The secondary structure changes quantified by FTIR reveal that metal ion binding typically causes a marked decrease (12.9-40.3%) in α-helical content accompanied by increased β-sheet and β-turn structures [9]. These conformational alterations demonstrate that metal ions can significantly impact protein structure, potentially affecting biological function. According to the Hard and Soft Acid-Base (HSAB) theory, hard metal ions (e.g., Ca²âº, Ba²âº) preferentially interact with hard binding sites like carboxylate groups, while soft metal ions (e.g., Agâº) favor soft bases such as sulfur-containing residues [9]. FTIR spectroscopy provides experimental validation of these theoretical predictions through observable spectral changes.

Materials Science Applications

In materials science, FTIR spectroscopy facilitates the characterization of metal-ligand interactions in coordination polymers, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and energy storage materials. For instance, studies on lithium cobalt diphosphate (Liâ‚‚CoPâ‚‚O₇) have utilized FTIR to identify distinct vibrational modes characteristic of Pâ‚‚O₇â´â» groups within the material's structural framework [15]. The IR spectrum revealed vibrations between 400-1200 cmâ»Â¹ corresponding to P-O bonding environments, confirming the successful formation of the pyrophosphate structure through a solid-state reaction route. This information is crucial for understanding structure-property relationships in materials designed for energy storage applications.

The analysis of toxic metals in various matrices represents another significant application of FTIR in materials characterization. Advanced FTIR methodologies, including integration with chemometric models and hybrid analytical systems, have improved detection limits and analytical precision for identifying metal contaminants in environmental and food samples [16]. While FTIR does not directly quantify metal concentrations, it identifies functional groups that participate in metal binding and detects metal-induced biochemical alterations, providing essential insights into contamination, toxicity, and remediation methodologies.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol for Protein-Metal Ion Binding Studies

The following detailed protocol describes the investigation of metal ion interactions with bovine serum albumin (BSA) using FTIR spectroscopy, based on established methodology [9]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA, ≥99%)

- Metal salts (e.g., CaCl₂, Ba(NO₃)₂, AgCl, RuCl₃, CuCl₂, CoCl₂·6H₂O)

- Tris buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4)

- Ultrapure water (resistivity 18.2 MΩ·cm)

Instrumentation:

- FTIR spectrophotometer (e.g., Nicolet iS10 FT-IR) equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT detector

- Hydrated film sample holder

- Agate mortar for solid mixing (if using solid samples)

Procedure:

- Prepare 20 mM tris buffer (pH 7.4) by dissolving 1.21 g tris powder in 500 mL ultrapure water and adjusting pH with dilute acetic acid.

- Prepare 0.5 mM BSA solution by dissolving accurately weighed BSA in tris buffer.

- Prepare 1.0 mM metal ion solutions in tris buffer and serially dilute to obtain 0.25, 0.1, and 0.025 mM concentrations.

- Mix metal ion and BSA solutions by slowly adding metal ion solutions to BSA solution with continuous stirring to achieve final concentrations of 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 mM metal ions with constant 0.25 mM BSA.

- Incubate mixtures at room temperature for 2 hours to allow complex formation.

- Collect IR spectra of pure BSA and each metal ion-BSA mixture using hydrated films over a range of 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹ at 4 cmâ»Â¹ resolution with 100 scans.

- Generate difference spectra by subtracting BSA spectrum from metal ion-BSA complex spectra.

- Analyze amide I region (1700-1600 cmâ»Â¹) by deconvolution and curve fitting to quantify secondary structure changes.

Data Analysis:

- Monitor intensity variations and shifting of amide I (1700-1600 cmâ»Â¹) and amide II (~1550 cmâ»Â¹) bands.

- Deconvolve amide I region to resolve component peaks corresponding to α-helix (1660-1650 cmâ»Â¹), β-sheet (1637-1614 cmâ»Â¹), β-turn (1680-1661 cmâ»Â¹), and random coil (1648-1638 cmâ»Â¹) structures.

- Calculate percentage changes in secondary structure elements by comparing areas of fitted peaks before and after metal ion binding.

Protocol for Solid-State Coordination Complex Analysis

This protocol describes the characterization of solid coordination complexes using the KBr pellet method [10] [15]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Coordination complex (dry powder)

- Potassium bromide (FTIR grade, dried)

- Hydraulic pellet press

- Vacuum die for pellet formation

Instrumentation:

- FTIR spectrometer with solid sample holder

- Pellet press capable of applying 8-10 tons pressure

- Agate mortar and pestle

Procedure:

- Dry KBr powder at 110°C for at least 2 hours to remove absorbed water (critical for hygroscopic materials).

- Gently grind 1-2 mg of the coordination complex with 200 mg dried KBr in an agate mortar until homogeneous (avoid excessive pressure that might induce polymorphic transitions).

- Transfer the mixture to a vacuum die and apply 8-10 tons pressure under vacuum for 2-5 minutes to form a transparent pellet.

- Mount the pellet in the solid sample holder of the FTIR spectrometer.

- Collect background spectrum with an empty holder or pure KBr pellet.

- Acquire sample spectrum over desired range (typically 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹) at 2-4 cmâ»Â¹ resolution with 32-64 scans.

- Process spectra by applying appropriate baseline correction and atmospheric suppression algorithms.

Data Interpretation:

- Identify key ligand vibrations before and after coordination (e.g., C=O, C=N, N-H, O-H stretches).

- Note frequency shifts and intensity changes indicative of metal-ligand bonding.

- Compare with literature spectra of free ligands and related complexes to assign coordination mode.

Visualizing FTIR Workflows for Metal-Ligand Systems

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for FTIR analysis of metal-ligand systems, from sample preparation to data interpretation:

FTIR Analysis Workflow for Metal-Ligand Systems

The application of FTIR spectroscopy to specific metal-ligand systems follows logical pathways for data interpretation, as illustrated in the following diagram for protein-metal ion systems:

Data Interpretation Pathway for Protein-Metal Systems

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful FTIR studies of metal-ligand systems require specific materials and instrumentation. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in FTIR experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FTIR Studies of Metal-Ligand Systems

| Category | Specific Items | Function in FTIR Experiments | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IR Transparent Materials | KBr, CsI, NaCl | Matrix for pellet preparation | KBr offers wide range; CsI extends to far-IR; NaCl avoids water absorption |

| Window Materials | CaFâ‚‚, ZnSe, Diamond | Windows for liquid and ATR cells | CaFâ‚‚ for aqueous solutions; Diamond for durability; ZnSe for broad range |

| Biological Samples | Bovine Serum Albumin | Model protein for metal-binding studies | Structure well-characterized; resembles human serum albumin |

| Metal Salts | Chlorides, nitrates, acetates | Sources of metal ions | Water-soluble salts preferred for solution studies |

| Buffer Systems | Tris, phosphate, HEPES | Maintain physiological pH | Must have minimal IR absorption in regions of interest |

| Spectrophotometers | Nicolet iS10, PerkinElmer FTIR-100 | FTIR data collection | MCT detectors recommended for high sensitivity |

| Terbiumacetate | Terbiumacetate, MF:C6H12O6Tb, MW:339.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| oxalic acid | Oxalic Acid Reagent|High-Purity|For Research Use | Bench Chemicals |

FTIR spectroscopy stands as a versatile, sensitive, and information-rich technique for probing metal-ligand bonding and coordination environments across diverse chemical and biological systems. Its ability to detect subtle changes in vibrational frequencies provides insights into binding modes, bond strengths, and structural rearrangements accompanying metal coordination. While the technique does not directly quantify metal concentrations like AAS or ICP-MS, it offers complementary information about the molecular context of metal binding that these elemental analysis methods cannot provide.

The continuing evolution of FTIR methodology, including advancements in synchrotron sources, microspectroscopy, temperature-dependent studies, and computational analysis, promises to further expand its applications in coordination chemistry. As researchers continue to develop new metal complexes for catalytic, medicinal, and materials applications, FTIR spectroscopy will remain an essential characterization tool that provides fundamental understanding of the metal-ligand interactions governing function and reactivity.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for Stability and Decomposition Profiling

The characterization of coordination complexes is fundamental to advancing research in catalysis, molecular magnetism, and pharmaceutical sciences. Among the suite of analytical techniques available, Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) stands out for its direct measurement of thermal stability and decomposition behavior. TGA provides critical data on mass changes as a function of temperature or time under controlled atmospheres, enabling researchers to identify decomposition steps, determine solvent loss, assess thermal stability, and evaluate compositional fractions in complex materials [17] [18].

This technique is particularly valuable for coordination complexes and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), where thermal behavior directly influences application potential and operational limits. When integrated with other characterization methods, TGA forms a cornerstone of comprehensive materials analysis, providing insights that complement structural data from techniques like XRD and NMR. This guide examines TGA's role in coordination complex characterization, comparing its capabilities with alternative thermal techniques and providing detailed experimental protocols to ensure research reproducibility across diverse laboratory environments.

TGA Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis with Alternative Techniques

Core Principles of Thermogravimetric Analysis

TGA operates on a straightforward yet powerful principle: precise measurement of mass changes in a material as it undergoes controlled temperature programming. The instrument consists of a high-precision balance housed within a furnace where the sample is subjected to predetermined temperature regimes. As the temperature changes, mass losses occur due to processes including dehydration, decomposition, combustion, or phase transitions, while mass gains may result from oxidation reactions [18].

The primary data output is a thermogravimetric (TG) curve plotting sample mass (or percentage mass) against temperature or time. From this curve, key parameters are derived: onset temperature (initial decomposition temperature), mass change percentage for each step, and residual mass at experiment completion. The derivative of the TG curve (DTG) is often calculated, highlighting temperatures at which decomposition rates peak and resolving overlapping thermal events that may appear as single steps in the primary TG curve [18].

TGA Versus DSC: A Direct Comparison

While TGA measures mass changes, Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) detects heat flow differences between a sample and reference, providing data on thermal transitions such as melting, crystallization, glass transitions, and curing behavior [17]. The complementary nature of these techniques often makes them ideal partners in thermal analysis.

The table below provides a direct comparison of these techniques for coordination complex characterization:

Table 1: Comparison of TGA and DSC for Material Characterization

| Feature | TGA | DSC |

|---|---|---|

| What it measures | Mass change | Heat flow |

| Primary applications | Thermal stability, composition, decomposition profiling | Melting points, glass transitions, crystallization, purity |

| Sample size | 5–30 mg [17] | 1–10 mg [17] |

| Output units | mg or percentage mass [18] | mW (milliwatts) [17] |

| Data provided | Decomposition steps, residual mass, volatile content | Transition temperatures, enthalpy changes, specific heat capacity |

| Ideal for coordination complexes | Solvent loss determination, decomposition pathway mapping, stability assessment | Polymorph identification, phase transition analysis, purity validation |

Complementary Thermal Techniques

Beyond DSC, other thermal analysis methods provide additional characterization dimensions:

- High-Pressure TGA (HP-TGA): Enables stability testing under realistic service conditions, including elevated pressures and corrosive atmospheres. Particularly valuable for coordination complexes destined for high-pressure applications [19].

- TGA-FTIR/TGA-MS: Coupled techniques that identify evolved gases during decomposition, providing mechanistic insights into decomposition pathways by correlating mass losses with specific gas evolution [20].

Experimental Protocols for Coordination Complex Analysis

Standard TGA Protocol for Thermal Stability Assessment

Purpose: To determine the thermal stability profile and decomposition steps of a coordination complex.

Materials and Equipment:

- TGA instrument with controlled atmosphere capability

- High-precision balance (0.1 μg sensitivity recommended) [21]

- Platinum or alumina crucibles (50-100 μL capacity)

- High-purity purge gases (nitrogen, argon, or air)

- Sample preparation tools (spatula, micro-pestle and mortar)

- Desiccator for moisture-sensitive samples

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for TGA Experiments

| Item | Function | Considerations for Coordination Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum Crucibles | Sample containment during heating | Inert, reusable; ensure chemical compatibility |

| Alumina Crucibles | Alternative sample containment | Lower cost, suitable for high temperatures |

| High-Purity Nitrogen | Inert atmosphere for pyrolysis | Prevents oxidative decomposition |

| Synthetic Air | Oxidative atmosphere | Assesses oxidative stability |

| Calibration Standards | Instrument calibration | Use certified reference materials (e.g., Curie point standards) |

| Microbalance Calibration Weights | Mass accuracy verification | Essential for quantitative measurements |

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Perform temperature and mass calibration according to manufacturer specifications using certified reference materials. Temperature calibration typically uses magnetic standards (e.g., Perkalloy, Alumel) with known Curie points [21].

- Sample Preparation: Gently grind the coordination complex to consistent particle size (avoiding excessive mechanical stress). Weigh 5-15 mg accurately using a microbalance [18].

- Baseline Measurement: Run an empty crucible through the intended temperature program to establish a baseline curve for subsequent subtraction.

- Experimental Parameters:

- Temperature range: 25°C to 800°C (or higher based on expected stability)

- Heating rate: 10°C/min (standard); adjust based on resolution needs

- Purge gas: Nitrogen at 50-100 mL/min flow rate

- Sample atmosphere: Inert (Nâ‚‚, Ar) for stability; oxidative (air, Oâ‚‚) for combustion studies

- Data Collection: Execute the temperature program while continuously recording mass data. Perform at least duplicate runs to ensure reproducibility.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot TG and DTG curves

- Identify onset temperatures for each mass loss step

- Calculate percentage mass loss for each step

- Determine final residue percentage

Advanced Protocol: Kinetic Analysis of Decomposition

Purpose: To determine kinetic parameters (activation energy, reaction order) for decomposition steps of coordination complexes.

Materials and Equipment: As in Protocol 3.1, with emphasis on precise temperature control.

Procedure:

- Multi-rate Experiments: Perform TGA experiments at multiple heating rates (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20°C/min) using identical sample masses and conditions [22] [23].

- Model-Free Kinetic Analysis: Apply isoconversional methods (e.g., Flynn-Wall-Ozawa, Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose) to determine activation energy without assuming a specific reaction model [22] [24].

- Model Fitting: Fit experimental data to various reaction models (e.g., n-th order, diffusion-controlled) to determine the most probable decomposition mechanism.

- Parameter Calculation:

- Determine activation energy (Eâ‚) and pre-exponential factor (A)

- Calculate thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔG, ΔS) for decomposition steps

- Assess consistency of kinetic parameters across conversion ranges

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard TGA experimental workflow for coordination complex analysis:

Data Interpretation and Analytical Considerations

Interpreting TGA Curves for Coordination Complexes

A systematic approach to TGA curve interpretation reveals essential information about coordination complex behavior:

- Initial Mass Loss (25-150°C): Typically indicates solvent loss (water, crystallization solvents). The temperature range and mass loss percentage help identify solvent binding strength—physisorbed versus coordinated solvent molecules [18].

- Intermediate Steps (150-400°C): Often represent decomposition of organic ligands or loss of coordinated anions. Multiple distinct steps suggest sequential decomposition processes.

- High-Temperature Events (>400°C): May indicate complete combustion of organic components or structural collapse of complex frameworks, leaving metal oxide residues.

- Final Residual Mass: Represents inorganic content (metal oxides, ash), providing validation of complex composition and stoichiometry [18].

Advanced Data Analysis Techniques

Beyond basic curve interpretation, several advanced分æžæ–¹æ³• enhance TGA utility:

- Kinetic Parameter Extraction: Using model-free methods (e.g., FWO, KAS) to calculate activation energies without assuming reaction mechanisms. For example, studies on polymers report activation energies of 58.8-64.6 kJ·molâ»Â¹ using these methods [22].

- TGA Indices for Performance Prediction: Developing quantitative indices to predict material behavior. Recent research has established correlations between TGA-derived indices and industrial performance metrics, with R² values exceeding 0.93 for certain parameters like the Volatile Matter Release Index [25].

- Machine Learning Integration: Implementing deep neural networks (DNN) to predict thermal behavior, with reported R² values ~0.999 for polymer degradation models incorporating temperature, time, and heating rate parameters [22].

Applications in Coordination Complex Research

Stability Assessment and Composition Determination

TGA provides direct evidence of coordination complex stability under thermal stress, critical for applications requiring elevated temperatures. The technique quantitatively determines:

- Solvent content and coordination environment (labile versus strongly-bound solvents)

- Thermal stability thresholds for practical application

- Decomposition pathways through stepwise mass losses

- Final composition through residual mass analysis

For example, in metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), TGA can differentiate between surface-adsorbed and pore-incorporated solvents, inform activation protocols, and establish temperature limits for structural integrity.

Validation of Synthetic Products and Quality Control

In coordination chemistry, TGA serves as a rapid validation tool for synthesized complexes by:

- Confirming expected composition through mass loss percentages

- Identifying synthetic variations between batches through curve comparison

- Detecting impurities that alter thermal profiles

- Verifying solvent removal after synthesis or activation procedures

The high sensitivity of modern TGA instruments (capable of detecting μg-level mass changes) enables quantification of minor components and contaminants that might otherwise escape detection [21].

Methodological Limitations and Advanced Solutions

Recognizing TGA Limitations

While powerful, TGA has inherent limitations that researchers must acknowledge:

- Atmospheric Effects: Decomposition temperatures and pathways can vary significantly between inert and oxidative atmospheres [19].

- Heating Rate Artifacts: Faster heating rates may shift decomposition temperatures higher and obscure overlapping events [18].

- Sample Form Effects: Particle size, packing density, and sample mass can influence heat transfer and gas exchange, altering results [23].

- Limited Volatile Detection: Standard TGA measures mass changes but cannot identify evolved gases without coupled techniques.

Advanced TGA Methodologies to Overcome Limitations

Several advanced TGA approaches address these limitations:

- High-Pressure TGA (HP-TGA): Enables testing under application-relevant pressures (up to 80 bar), revealing pressure-dependent decomposition behavior not observable at ambient pressure [19].

- Modulated TGA: Applies temperature oscillations to enhance resolution of overlapping events.

- Coupled Techniques: TGA-FTIR and TGA-MS combine mass change data with chemical identification of evolved species, providing mechanistic insights into decomposition processes [20].

Table 3: Comparison of Standard and Advanced TGA Approaches

| Parameter | Standard TGA | High-Pressure TGA | Coupled TGA-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure range | Ambient | Vacuum to 80 bar [19] | Ambient |

| Atmosphere control | Single gas | Multiple gas switching | Single gas with MS interface |

| Data output | Mass change only | Mass change at elevated pressure | Mass change + gas identification |

| Application focus | General stability | Application-mimicking conditions | Decomposition mechanism |

| Sample requirements | 5-30 mg | ~20 mg [19] | 5-15 mg |

Thermogravimetric Analysis remains an indispensable technique in the coordination chemist's characterization toolkit, providing direct, quantitative data on thermal stability and decomposition behavior that complements structural information from other analytical methods. Its strength lies in its quantitative nature, relatively simple implementation, and adaptability to various sample types and experimental conditions.

For researchers investigating coordination complexes, TGA offers unique insights into composition, stability limits, and decomposition pathways that directly influence material selection and application potential. When integrated with complementary techniques like DSC and evolved gas analysis, TGA provides a comprehensive thermal characterization profile essential for advancing materials development in catalysis, gas storage, drug development, and molecular electronics.

As TGA technology continues to evolve with enhancements in sensitivity, pressure capabilities, and computational integration, its role in coordination complex characterization will further expand, enabling more precise predictions of material behavior under operational conditions and accelerating the development of next-generation functional materials.

Magnetic Susceptibility and Molar Conductivity Measurements

In the characterization of coordination complexes, magnetic susceptibility and molar conductivity measurements serve as fundamental, complementary techniques that provide rapid insights into the electronic structure and ionic nature of novel compounds. Magnetic susceptibility reveals the number of unpaired electrons and geometry around the metal center, while molar conductivity indicates the electrolyte behavior of complexes in solution. Together, these techniques form a crucial first step in correlating structural properties with potential applications in materials science, catalysis, and pharmaceutical development. This guide objectively compares the data interpretation frameworks for these techniques and presents experimental data from recent research to illustrate their practical application in coordination chemistry.

Comparative Data Tables for Coordination Complexes

Magnetic Susceptibility and Molar Conductivity Data for Recent Complexes

Table 1: Experimental magnetic susceptibility and molar conductivity values for recently reported coordination complexes.

| Complex Formulation | Geometry | Magnetic Moment (μeff, BM) | Molar Conductivity (Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹) | Interpretation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Ni(HL)L]X (X = Clâ», NO₃â», Brâ») | Octahedral | 3.12-3.30 | 67.6-85.6 | High-spin Ni(II); 1:1 electrolyte | [26] |

| [Cu(L1)Cl]Cl | Distorted Octahedral | ~1.85 | - | dâ¹ configuration with one unpaired electron | [27] |

| [Mn(L1)Cl]Cl | Octahedral | 5.92 | - | High-spin Mn(II); five unpaired electrons | [27] |

| [Co(L1)Cl]Cl | Octahedral | 4.87 | - | High-spin Co(II); three unpaired electrons | [27] |

| Binuclear Cu(II) complex | - | - | - | Antiferromagnetic at low temperature | [28] |

Interpretation Frameworks for Measurement Data

Table 2: Standard interpretation frameworks for magnetic and conductivity data.

| Parameter | Measurement Range | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Molar Conductivity | ||

| 1-50 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹ | Non-electrolyte | |

| 60-80 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹ | 1:1 Electrolyte | |

| 120-160 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹ | 1:2 Electrolyte | |

| >200 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹ | 1:3 Electrolyte | |

| Magnetic Moment | ||

| ~1.7-2.2 BM | One unpaired electron | |

| ~2.9-3.3 BM | Two unpaired electrons | |

| ~3.7-4.0 BM | Three unpaired electrons | |

| ~4.8-5.1 BM | Four unpaired electrons | |

| ~5.6-6.1 BM | Five unpaired electrons |

Experimental Protocols

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurement Methodology

The magnetic susceptibility of coordination compounds is measured to determine the number of unpaired electrons, which provides information about oxidation states, geometry, and ligand field effects.

Sample Preparation for Solid-State Measurements

For solid-state magnetic measurements, sample preparation must prevent orientational rotation of crystallites under the applied magnetic field. Preferred methods include:

- Pelleting: Compressing polycrystalline samples into a pellet, though this may cause amorphization or loss of solvate molecules.

- Immobilization in Eicosane: Heating with eicosane above its melting point, but this may lead to solvent loss.

- Hermetic Packing in Fluorinated Oil: Preferred for coordination compounds containing solvate molecules, as it prevents decomposition under vacuum conditions used in magnetometers [29].

After measurements, the diamagnetic contribution of sample holders and packing materials must be subtracted from the total magnetization values [29].

Guoy Balance Method

The Guoy balance provides a straightforward approach for determining the presence of unpaired electrons:

- A magnet is weighed in the presence and absence of the sample.

- Diamagnetic samples cause slight repulsion, registering as heavier weight.

- Paramagnetic samples cause slight attraction, registering as lighter weight.

- The strength of attraction correlates with the number of unpaired electrons [30].

The effective magnetic moment (μeff) is calculated from the measured susceptibility and expressed in Bohr Magnetons (BM), using the relationship:

[ 1 \text{BM} =\frac{e h}{4 \pi m c} ]

where e is the electron charge, h is Planck's constant, m is electron mass, and c is the speed of light [30].

Dynamic Magnetic Susceptibility

For single-molecule magnets, dynamic magnetic susceptibility (χ_ac) measurements characterize magnetic relaxation dynamics:

- The sample is placed in an alternating magnetic field: Hac(t) = H0 cos(ωt)

- The magnetization response is measured: Mac = M0 cos(ωt - φ)

- Real (χ') and imaginary (χ") components are derived from phase relationships

- Frequency-dependent measurements reveal slow magnetic relaxation behavior [29]

Molar Conductivity Measurement Protocol

Molar conductivity measurements determine the ionic character of coordination complexes in solution:

Standard Experimental Procedure

- Prepare a 10â»Â³ M solution of the complex in appropriate solvent (typically DMSO or DMF)

- Measure conductivity at room temperature (25 ± 1°C) using a conductivity bridge

- Use a standard cell constant with platinum electrodes

- Calculate molar conductivity using the formula:

[ \Lambda_m = \frac{\kappa}{C} ]

where κ is the measured conductivity and C is the molar concentration [26] [27].

Data Interpretation

Compare measured values against established ranges for electrolyte behavior:

- Non-electrolytes: 1-50 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹

- 1:1 Electrolytes: 60-80 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹

- 1:2 Electrolytes: 120-160 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹

- 1:3 Electrolytes: >200 Ωâ»Â¹cm²molâ»Â¹ [26]

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Workflow for Characterization - This diagram illustrates the parallel measurement pathways for magnetic susceptibility and molar conductivity, demonstrating how both techniques contribute to comprehensive coordination complex characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and equipment for magnetic and conductivity measurements.

| Item | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Diamagnetic Correction Materials | Account for inherent diamagnetism | Eicosane, mineral oil, or Nujol for sample immobilization [29] |

| FTIR Spectrometer | Confirm ligand coordination | PerkinElmer 5700 for metal-ligand bond identification [31] |

| Magnetic Susceptibility Balance | Measure unpaired electrons | MSB MK1 Sherwood for effective magnetic moments [27] |

| Conductivity Bridge | Determine electrolyte behavior | MICROSIL bridge or 4510-Jenway for molar conductivity [31] [27] |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR characterization for ligands | CDCl₃ for ¹H-NMR analysis [31] |

| High-Purity Metal Salts | Complex synthesis | Ni(II), Cu(II), Co(II) chlorides for complex preparation [26] [27] |

| Schiff Base Ligands | Coordinate to metal centers | Quinoline-2-carbaldehyde thiosemicarbazone for Ni(II) complexes [26] |

| Z-Pro-Leu-Gly-NHOH | Z-Pro-Leu-Gly-NHOH, MF:C21H30N4O6, MW:434.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-Pirlindole Hydrobromide | (S)-Pirlindole Hydrobromide |

Magnetic susceptibility and molar conductivity measurements remain indispensable tools in the initial characterization of coordination complexes, providing complementary data on electronic structure and solution behavior. The experimental protocols and interpretation frameworks presented enable researchers to quickly assess fundamental properties that inform subsequent application-directed studies. Recent research continues to validate the utility of these techniques across diverse complex types, from classical Werner-type complexes to modern single-molecule magnets. As coordination chemistry advances toward increasingly sophisticated applications, these foundational characterization methods maintain their critical role in correlating molecular structure with functional properties in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

Electronic Spectroscopy for Geometric and Electronic Structure Elucidation

Electronic spectroscopy serves as a powerful analytical technique for probing the geometric and electronic structures of coordination complexes, providing crucial insights that guide their application in drug development, materials science, and catalysis. This method exploits the interaction between light and matter, measuring the absorption of ultraviolet (UV) or visible (Vis) radiation as electrons transition between molecular orbitals. The resulting spectra contain distinctive fingerprints that reveal intricate details about a complex's electronic configuration, ligand field strength, coordination geometry, and metal-ligand bonding interactions. For research scientists investigating coordination compounds, electronic spectroscopy offers a versatile approach for characterizing fundamental properties that dictate reactivity, stability, and function. Unlike many structural techniques that require high-quality crystals, electronic spectroscopy can be applied to compounds in various states, including solution phase, making it particularly valuable for studying biologically relevant systems and catalytic intermediates under operational conditions.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of electronic spectroscopy with complementary techniques, detailing experimental methodologies and illustrating how spectral data facilitates the elucidation of structural and electronic properties in coordination complexes.

Theoretical Foundations of Electronic Spectra

The information content in electronic spectra of coordination complexes derives from several types of electronic transitions, each governed by specific selection rules and influencing factors.

d-d Transitions

In transition metal complexes with partially filled d-orbitals, the most characteristic transitions involve electron promotion between metal-centered d-orbitals that have been split in energy by the ligand field. These d-d transitions provide direct information about the ligand field strength, represented by the crystal field splitting parameter (Δ₀ for octahedral complexes). For a d¹ system in an octahedral field, a single transition is expected, corresponding to the energy difference between the t₂g and eg orbitals. However, for systems with multiple d-electrons (e.g., d²), the situation becomes more complex due to electron-electron repulsions, requiring the use of Term Symbols to account for all possible microstates and transitions [32].

The intensity of d-d transitions is governed by two primary selection rules:

- Spin selection rule: Transitions between states of different spin multiplicities are forbidden.

- Laporte rule: Transitions between orbitals of the same parity (e.g., g→g or u→u) are forbidden in centrosymmetric molecules [32].

These selection rules explain why d-d transitions are typically weak in intensity. However, vibrational coupling or deviations from perfect centrosymmetry can partially relax these rules, providing evidence for geometric distortions.

Charge-Transfer Transitions

Charge-transfer transitions involve electron movement between molecular orbitals predominantly localized on the metal to those predominantly localized on the ligands, or vice versa. Unlike d-d transitions, charge-transfer bands are often intense because they are both spin- and Laporte-allowed [32].

- Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): Occur when electrons transition from ligand-centered orbitals to metal-centered orbitals. These transitions are favored when the metal is in a high oxidation state (stabilizing the accepting d-orbitals) and the ligands are good Ï€-donors with high-energy orbitals (e.g., O²⻠in MnOâ‚„â») [32].

- Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): Involve electron promotion from metal-centered orbitals to low-lying empty Ï€* orbitals on the ligands. These are common with Ï€-acceptor ligands (e.g., phenanthroline, CNâ», CO) and metals in low oxidation states with high electron density (e.g., Cu(I) in bis(phenanthroline)copper(I)) [32].

Table 1: Characteristics of Electronic Transitions in Coordination Complexes

| Transition Type | Energy Range | Intensity | Structural Information | Example Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-d Transitions | Visible / Near-IR | Weak (ε = 10-200 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) | Ligand field strength (Δ₀), coordination geometry, oxidation state | [Cr(Hâ‚‚O)₆]³âº, [Ti(Hâ‚‚O)₆]³⺠|

| LMCT | UV-Vis | Strong (ε > 1,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) | Metal oxidation state, ligand donor strength | MnOâ‚„â», CrO₄²⻠|

| MLCT | UV-Vis | Strong (ε > 1,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) | Metal reducing power, ligand Ï€-acceptor ability | [Ru(bpy)₃]²âº, [Cu(phen)â‚‚]⺠|

| σ-Bonding Transitions | UV | Variable | Metal-ligand σ-bond formation | Various σ-bonded complexes |

| π-Backbonding | UV-Vis | Medium to Strong | Extent of metal→ligand π-donation | [Fe(CO)₅], [RuCl₂(CO)₃]₂ [33] |

Comparative Analysis of Characterization Techniques

While electronic spectroscopy provides crucial electronic structure information, a complete characterization of coordination complexes typically requires a multi-technique approach. The table below compares the capabilities of electronic spectroscopy with other common spectroscopic methods.

Table 2: Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques for Coordination Complex Characterization

| Technique | Information Obtained | Sample Form | Detection Limits | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Spectroscopy | Ligand field strength, oxidation state, coordination geometry, charge-transfer transitions | Solution, solid, film | ~10â»âµ M | Broad bands complicate deconvolution, requires interpretation with theory |

| Infrared Spectroscopy | Ligand identity, metal-ligand bonding, π-backbonding (via CO stretches) | Solid, solution, KBr pellets | ~1% | Primarily surface/bulk, overlapping signals in complex systems |

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy | Oxidation state, local coordination geometry, interatomic distances | Solid, solution, frozen glass | ~100 ppm | Requires synchrotron source, complex data analysis |

| Magnetic Circular Dichroism | Geometric and electronic structure, spin state, ligand field parameters | Solution, frozen glass | ~10â»â´ M | Specialized equipment, low temperatures often required |

| Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy | Heme and non-heme iron centers, Fe-ligand bonding | Solid | N/A | Extremely specialized, limited to specific isotopes |

| Mass Spectrometry | Molecular mass, complex stoichiometry, fragmentation patterns | Solution | ~fmol | Requires volatilization, may not represent native solution structure |

Electronic spectroscopy excels in probing the electronic ground state and excited states of complexes, directly revealing ligand field effects and electronic transitions that are often correlated with reactivity. However, its limitation in providing precise geometric parameters necessitates combination with techniques like X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), which provides element-specific local structural information including oxidation state through XANES and bond distances/coordination numbers through EXAFS [34]. For challenging systems such as integer-spin non-heme Fe(II) centers, Near-IR Variable-Temperature Variable-Field Magnetic Circular Dichroism has emerged as a powerful methodology, as these dⶠions have an S = 2 ground state with no EPR signal at X-band but exhibit diagnostic C-term MCD signals [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Measurement

Protocol 1: Solution-Phase UV-Vis Spectroscopy

- Solvent Selection: Choose a solvent that is transparent in the spectral region of interest. Common choices include acetonitrile, dichloromethane, and water. Avoid solvents that absorb in the UV region if measuring below 300 nm.

- Sample Purity: Ensure the complex is pure and free from absorbing impurities that could obscure the spectral features.

- Concentration Optimization: Prepare solutions with concentrations typically between 10â»Â³ to 10â»âµ M. Adjust concentration so that the absorbance of the strongest band falls within the linear range of the instrument (ideally <1.5 AU).

- Cuvette Selection: Use quartz cuvettes for UV-Vis measurements (transparent down to ~200 nm). Glass cuvettes can be used for visible-only measurements (>350 nm).

- Baseline Correction: Collect a baseline spectrum using pure solvent in both sample and reference compartments.

- Data Collection: Scan an appropriate wavelength range (e.g., 200-800 nm) with a moderate scan speed and resolution. Perform multiple scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Data Analysis: Identify peak positions (λmax), calculate molar absorptivity (ε) using the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcl), and analyze band shapes and intensities.

Protocol 2: Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Solids

- Sample Preparation: Grind the solid complex to a fine, uniform powder to minimize light scattering.

- Reference Standard: Use a non-absorbing standard such as barium sulfate or spectralon.

- Sample Loading: Pack the sample into a holder designed for diffuse reflectance measurements.

- Data Collection: Collect spectra over the desired range. The instrument typically measures and converts diffuse reflectance to a function proportional to absorption (e.g., Kubelka-Munk function).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the transformed spectra similarly to solution spectra, noting that direct comparison of intensities with solution data may not be valid.

Data Interpretation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for interpreting electronic spectra of coordination complexes:

Case Studies in Coordination Complex Analysis

Ruthenium Carbonyl Complexes with Poly(4-vinylpyridine)

The coordination complex formed between dichlorotricarbonylruthenium(II) and poly(4-vinylpyridine) demonstrates the power of combining electronic and vibrational spectroscopy. In this system, the pyridine nitrogen lone pair coordinates to the Ru²⺠center, which has a low-spin dⶠelectronic configuration. The characteristic infrared stretching frequencies of the terminal CO ligands (1900-2150 cmâ»Â¹) provide information about metal-ligand σ-bonding, molecular symmetry, and Ï€-back-donation. When strong σ-donors like pyridine coordinate to ruthenium, the CO absorptions shift to lower energy due to enhanced Ï€-back-donation from filled metal tâ‚‚g orbitals to empty Ï€* orbitals of carbon monoxide [33]. This synergism between σ-donation and Ï€-back-donation strengthens the metal-ligand bond while simultaneously providing a spectroscopic handle for monitoring coordination geometry and electronic effects.

Non-Heme Iron Enzyme Active Sites

Mononuclear non-heme iron enzymes utilize Fe(II) sites to activate dioxygen for diverse oxidation reactions. These ferrous active sites present characterization challenges as they are integer-spin (S = 2) systems with no EPR signal at X-band. A specialized methodology using near-IR variable-temperature, variable-field magnetic circular dichroism has been developed to probe these centers. The d-d transitions of Fe(II) sites are very sensitive to the ligand field, with six-coordinate sites showing transitions around 10,000 cmâ»Â¹, five-coordinate square pyramidal sites showing transitions in the >10,000 cmâ»Â¹ and ≈5000 cmâ»Â¹ regions, and four-coordinate tetrahedral sites exhibiting transitions only in the 5000-7000 cmâ»Â¹ region [35]. This sensitivity allows researchers to determine coordination number and geometry from the MCD spectra, providing crucial insights into how these enzymes control Oâ‚‚ activation through coordination unsaturation that is only present when substrates are bound.

Polymer-Metal Complexes of Modified Polystyrene-alt-Maleic Anhydride

Recent studies on polymer-metal complexes derived from modified polystyrene-alt-maleic anhydride with Mn(II), Ni(II), Co(II), and Cu(II) ions demonstrate how electronic spectroscopy complements other characterization techniques. These complexes were characterized using UV-Vis spectroscopy alongside magnetic moment susceptibility, conductance measurements, FT-IR spectroscopy, and thermogravimetric analysis. The electronic spectra, combined with magnetic data, confirmed an octahedral geometry for all the divalent metal complexes [36]. For such polymer-metal coordination systems, electronic spectroscopy provides crucial information about the metal ion environment despite the complexity of the polymeric ligand structure, enabling researchers to correlate geometric structure with functional properties like thermal stability and potential biomedical applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electronic Spectroscopy Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Provide medium for solution measurements without interfering absorptions | Acetonitrile (UV), Dichloromethane (UV), Water (UV-Vis); must be spectrophotometric grade |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Contain samples for UV-Vis measurement | Required for UV range (<350 nm); various path lengths (0.1-10 cm) available |

| Reference Standards | Wavelength and absorbance calibration | Holmium oxide filter (wavelength), Neutral density filters (absorbance) |

| Spectrophotometer | Measure light absorption across UV-Vis range | Should cover 190-1100 nm; double-beam preferred for stability |

| Integrating Sphere | Measure diffuse reflectance of solid samples | Essential for powder samples; converts reflectance to absorption data |

| Temperature Controller | Maintain constant temperature during measurement | Important for temperature-dependent studies; cryostats for low-temperature work |

| Ligand Libraries | Systematic variation of coordination environment | Series of related ligands to probe electronic and steric effects |

| Inert Atmosphere Equipment | Handle air-sensitive complexes | Glove boxes, Schlenk lines for oxygen-sensitive compounds |

| 2-(3-Ethynylphenoxy)aniline | 2-(3-Ethynylphenoxy)aniline, MF:C14H11NO, MW:209.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Octyl acetate | 4-Octyl Acetate|CAS 5921-87-9|Research Chemicals | 4-Octyl Acetate, also known as 4-Octanol, acetate (CAS 5921-87-9). This reagent is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of electronic spectroscopy continues to evolve with advancements in technology and data analysis methods. For bioinspired and biomimetic systems, coordination chemistry provides a flexible framework for designing functional materials that mimic natural processes. Electronic spectroscopy plays a crucial role in characterizing these systems, particularly those inspired by metalloproteins and metalloenzymes [37]. The development of advanced computational methods, including density functional theory and machine learning, has enhanced our ability to interpret electronic spectra and predict electronic structures of novel complexes [37] [38].

Recent innovations in hyphenated techniques, such as the combination of electrospray ionization with laser spectroscopy, allow for the study of isolated molecular ions free from perturbing solvent or matrix effects [39]. This approach enables precise mapping of the intrinsic properties of multicenter transition metal complexes and has revealed pronounced conformer/isomer dependencies of physical and chemical properties that are often obscured in condensed-phase measurements. As these advanced spectroscopic methodologies continue to develop alongside computational approaches, they promise to deepen our understanding of structure-function relationships in coordination complexes and accelerate the rational design of materials with tailored electronic properties.

Advanced Structural Elucidation and Biomedical Application-Oriented Techniques

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction for Definitive Structural Determination

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SC-XRD) stands as the undisputed gold standard for determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of crystalline materials [40]. This technique provides irrefutable evidence of molecular structure, enabling researchers across chemistry, materials science, and pharmaceutical development to visualize compounds with atomic resolution. The power of SC-XRD lies in its ability to precisely determine lattice parameters, atomic positions, bond lengths, bond angles, and configuration—information that forms the foundation for understanding structure-property relationships in functional materials and therapeutic agents [41].

For researchers characterizing coordination complexes and other crystalline materials, SC-XRD offers unparalleled definitive structural information that techniques like NMR spectroscopy or powder diffraction cannot match in resolution or unambiguity [42]. While alternative methods exist for structural analysis, each with particular strengths and limitations, SC-XRD remains unique in its capacity to provide a complete three-dimensional structural model from first principles, without requiring prior structural knowledge. This comprehensive guide examines the technical capabilities, experimental methodologies, and strategic applications of SC-XRD within the broader context of structural characterization techniques.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Capabilities

Core Theoretical Foundation

SC-XRD operates on the principle that X-rays, when directed at a crystalline sample, interact with the electrons of atoms in the crystal lattice and diffract in specific directions according to Bragg's Law: nλ = 2d sinθ, where λ is the X-ray wavelength, d is the interplanar spacing, θ is the diffraction angle, and n is an integer [43]. The resulting diffraction pattern represents a Fourier transform of the electron density within the crystal. By measuring the angles and intensities of these diffracted beams, a three-dimensional electron density map can be reconstructed, from which atomic positions and thermal parameters are derived [42] [41].

The technique requires high-quality single crystals, typically ranging from 30 to 300 microns in size, which must be sufficiently ordered to maintain coherent diffraction across their volume [41]. The quality of the resulting structural model is directly dependent on the crystal quality, the completeness of the diffraction data, and the resolution (typically expressed in Ångströms) to which data are collected. Modern instruments can routinely achieve atomic resolution (better than 1.2 Å), allowing for precise localization of atoms and detailed analysis of chemical bonding [44].

Information Content in SC-XRD Data

A comprehensive SC-XRD analysis provides multiple layers of structural information, each contributing to a complete understanding of the material under investigation:

- Primary Molecular Structure: Precise bond lengths (with uncertainties often < 0.001 Å) and bond angles (uncertainties < 0.1°), enabling detailed analysis of molecular geometry and bonding character [41].

- Stereochemical Configuration: Absolute configuration of chiral molecules, critical for understanding biological activity and reaction mechanisms in asymmetric synthesis [42].

- Crystal Packing and Supramolecular Features: Non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and van der Waals contacts that define solid-state properties [40].

- Thermal Motion Parameters: Anisotropic displacement parameters that model atomic vibrations and, in some cases, reveal static disorder within the crystal lattice [44].

- Electronic Structure Information: Through advanced charge density analysis, SC-XRD can provide insights into chemical bonding and electron distribution [44].

Table 1: Structural Information Accessible Through SC-XRD Analysis

| Information Type | Typical Precision | Significance for Materials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bond lengths | ±0.001-0.005 Å | Reveals bond order, strain, and coordination geometry |

| Bond angles | ±0.1-0.5° | Determines molecular geometry and hybridization |

| Torsion angles | ±0.5-1.0° | Defines molecular conformation and flexibility |

| Interatomic distances | ±0.01-0.05 Å | Maps supramolecular interactions and packing |

| Absolute structure | >99% reliability for light atoms | Determines handedness of chiral molecules |

| Thermal parameters | ±5-10% | Indicates atomic vibration and disorder |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Techniques

SC-XRD Versus Powder XRD and MicroED

While SC-XRD provides the most comprehensive structural information, several alternative diffraction methods offer complementary capabilities for situations where growing single crystals of sufficient size and quality proves challenging.

Table 2: Technical Comparison of SC-XRD with Alternative Diffraction Methods

| Parameter | Single-Crystal XRD | Powder XRD | MicroED | Single-Crystal Electron Diffraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Requirement | 30-300 μm single crystals | Polycrystalline powder | Nanocrystals (100 nm - 1 μm) | Nanocrystals (100 nm - 1 μm) |

| Structural Information | Complete 3D structure with atomic resolution | Limited by peak overlap, usually partial structure determination | Near-atomic resolution 3D structure | Near-atomic resolution 3D structure |