Comparative Photocatalytic Activity of Metal-Doped Metal Oxides: Design, Applications, and 2025 Outlook

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the photocatalytic performance of metal-doped metal oxides, a class of materials gaining significant traction for their tunable properties in environmental and biomedical applications.

Comparative Photocatalytic Activity of Metal-Doped Metal Oxides: Design, Applications, and 2025 Outlook

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the photocatalytic performance of metal-doped metal oxides, a class of materials gaining significant traction for their tunable properties in environmental and biomedical applications. We explore the foundational principles governing their activity, including bandgap engineering and charge carrier dynamics. The review systematically compares synthesis methodologies and examines specific applications, from water purification to the emerging field of in vitro drug metabolism simulation. Furthermore, we address key challenges such as electron-hole recombination and stability, presenting optimization strategies including heterojunction design and defect engineering. Through a comparative lens, this work validates the efficacy of various doped metal oxides, offering researchers and drug development professionals a structured framework for selecting and developing next-generation photocatalytic materials.

Principles and Potentials: Understanding Metal-Doped Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Metal oxides have emerged as a cornerstone class of materials in the field of photocatalysis, playing a pivotal role in addressing global environmental and energy challenges. Their prominence stems from a combination of favorable characteristics, including structural diversity, inherent stability, natural abundance, and cost-effectiveness [1]. These semiconductors are extensively investigated for applications ranging from water purification and air detoxification to renewable fuel production through photocatalytic water splitting [1]. This guide provides a comparative overview of metal oxide photocatalysts, examining their fundamental properties, performance data, and the experimental methodologies used to tune their activity for enhanced efficiency.

Fundamental Principles and Advantages of Metal Oxides

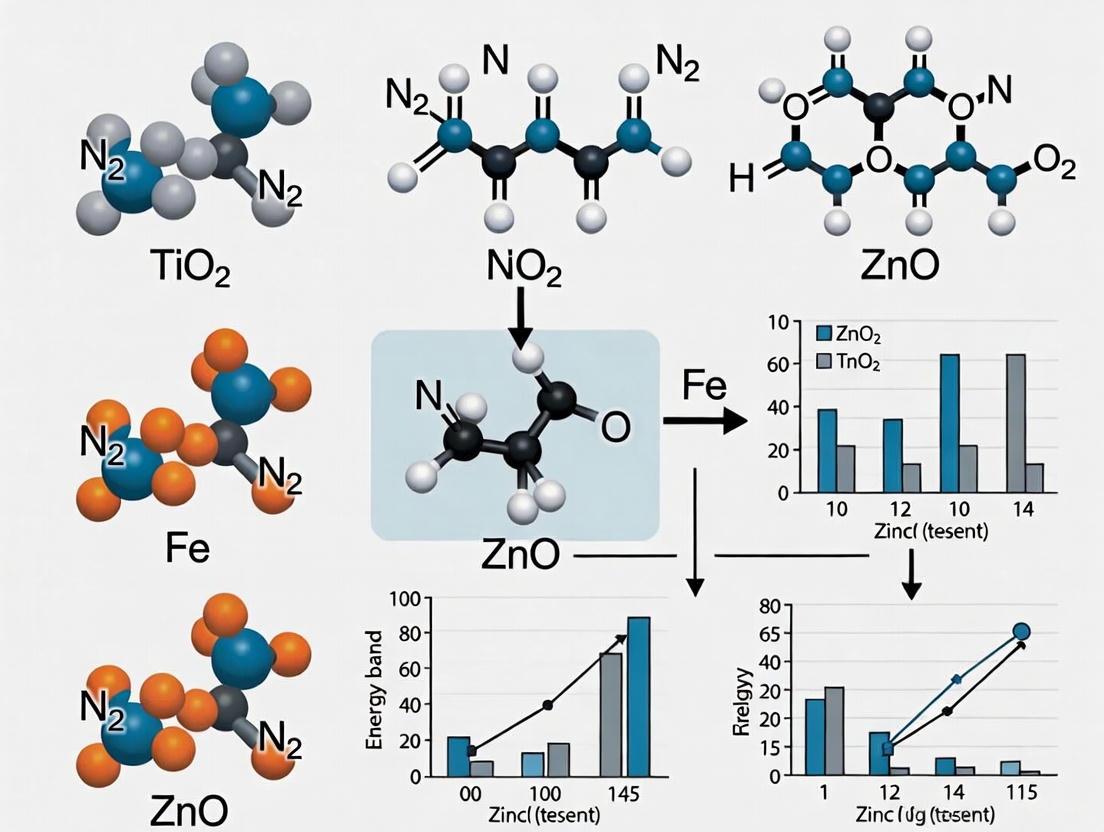

Photocatalysis is a light-driven process where a semiconductor absorbs photons to generate electron-hole pairs, which subsequently drive redox reactions. The general mechanism involves several key steps, as illustrated in the diagram below.

The comparative advantages of metal oxides over other photocatalyst classes are rooted in their material properties [1] [2]:

- Abundance: Many metal oxides, such as those of titanium, zinc, and iron, are derived from naturally occurring, earth-abundant elements, making them sustainable for large-scale applications.

- Stability: Metal oxides generally exhibit robust chemical and thermal stability, allowing them to operate under harsh reaction conditions, including in aqueous environments and under prolonged UV irradiation, without significant degradation [1] [3]. This contrasts with materials like metal sulfides, which can suffer from photocorrosion.

- Cost-Effectiveness: The raw materials are often low-cost, and synthesis methods can be scaled, contributing to their economic viability [1].

- Tunability: Their electronic structures—including bandgap energy and carrier mobility—can be tailored through synthetic control and material modification for specific redox reactions [1].

Comparative Performance of Key Metal Oxides

The photocatalytic performance of metal oxides varies significantly based on their intrinsic electronic properties and response to light. The table below summarizes key parameters for several prominent metal oxides.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Common Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Metal Oxide | Typical Bandgap (eV) | Primary Light Absorption Range | Key Strengths | Performance-Limiting Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | 3.0 - 3.2 [4] | UV | High stability, non-toxicity, high activity under UV light [1] | Wide bandgap, limited visible light use, rapid charge recombination [4] |

| ZnO | ~3.3 [3] | UV | High electron mobility, cost-effective [1] | Photocorrosion in aqueous environments, wide bandgap [3] |

| Fe₂O₃ (Hematite) | ~2.1 | Visible | Visible light absorption, abundant, low cost [5] | Very short carrier lifetime, poor charge separation [5] |

| BiVO₄ | ~2.4 | Visible | Good visible light absorption for water oxidation [1] [5] | Moderate charge carrier mobility, recombination losses [1] |

| WO₃ | ~2.6 | Visible | Good stability, visible light absorption [1] | Low conduction band level limits reduction power [1] |

| NiO | 3.4 - 4.0 [2] | UV | p-type semiconductor, stable [2] | Wide bandgap, limited visible light absorption [2] |

A critical factor governing performance is the carrier lifetime—how long the photo-generated electrons and holes remain separated and available for reactions. Recent research establishes a direct link between the electronic configuration of the metal atom and this lifetime [5].

- d⁰/d¹⁰ Oxides (e.g., TiO₂, BiVO₄): Materials with empty (d⁰) or filled (d¹⁰) d-shells lack metal-centred ligand field states, which function as fast relaxation pathways. This absence results in intrinsically longer-lived charge carriers and higher quantum yields, explaining the high efficiency of TiO₂ despite its UV-only absorption [5].

- Open d-shell Oxides (e.g., Fe₂O₃, Co₃O₄, NiO): Oxides with partially filled d-orbitals possess ligand field states that open a sub-picosecond relaxation channel, drastically reducing carrier lifetimes and quantum yields. This is a key reason why many visible-light-absorbing transition metal oxides exhibit poor photocatalytic efficiency [5]. Fe₂O₃ is a notable exception because its ligand field transitions are spin-forbidden, partially mitigating this loss pathway and enabling its moderate photoelectrochemical activity [5].

Key Strategies for Enhancing Photocatalytic Activity

The performance of pristine metal oxides is often limited by factors such as rapid electron-hole recombination and limited visible light absorption. Several strategies are employed to overcome these barriers, as detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Common Modification Strategies for Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Strategy | Mechanism | Example & Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Doping | Introduces new energy levels within the bandgap, narrowing the bandgap and/or trapping charge carriers to suppress recombination [6] [3]. | Transition metal doping: DFT+U calculations show Co or Fe doping in α-NiS modulates bandgap (1.10-2.57 eV) and enhances carrier mobility [6]. Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs): Isolated metal atoms on a support (e.g., Cu on TiO₂-rGO) maximize atom efficiency and improve electron transfer [7]. |

| Heterojunction Construction | Couples two semiconductors with aligned band structures to promote spatial separation of electrons and holes [2]. | NiS/TiO₂ p-n heterostructure: Achieved 98% degradation of methyl orange in 20 min by enhancing charge separation [6]. |

| Defect Engineering | Creates oxygen vacancies or other point defects that act as active sites and can modify light absorption properties [3]. | Controlled oxygen vacancies in NiO influence its reactivity and p-type conductivity [2]. |

| Nanostructuring & Morphology Control | Increases specific surface area, providing more active sites for reactions and shortening charge migration paths [1]. | Synthesis techniques like sol-gel and hydrothermal routes fine-tune crystal size, shape, and porosity [1]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of Metal and Metal-Doped Metal Oxides

The sol-gel method is a widely used, versatile technique for producing metal oxide nanoparticles. A representative protocol for creating metal-doped TiO₂ fabrics is as follows [4]:

- Precursor Preparation: Titanium-based precursors (e.g., titanium alkoxides) are dissolved in a solvent (e.g., ethanol).

- Doping Introduction: Aqueous solutions of dopant metal salts (e.g., Cu, Ag, Zn nitrates) are added to the precursor solution in trace molar ratios.

- Hydrolysis and Gelation: The mixture is stirred vigorously, and a controlled amount of water is added to initiate hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions, forming a wet gel.

- Aging and Drying: The gel is aged to complete the reaction network and then dried to remove the solvent, resulting in a xerogel.

- Calcination: The dried powder is calcined at elevated temperatures (e.g., 400-500°C) to crystallize the amorphous material into the desired metal oxide phase (e.g., anatase TiO₂).

- Immobilization (for fabrics): The synthesized nanoparticles can be functionalized with silane coupling agents and immobilized onto substrates like cotton fabric using a pad-dry-cure process [4].

Characterization and Photocatalytic Testing

Evaluating the performance of a photocatalyst involves a series of standardized characterizations and tests.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photocatalysis Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursors | (e.g., titanium alkoxides, zinc nitrate). The foundation for synthesizing the metal oxide framework. |

| Dopant Sources | (e.g., AgNO₃, Cu(NO₃)₂). Introduce foreign metal ions to modify the electronic structure. |

| Structural Probe Molecules | (e.g., N₂ gas). Used in physisorption measurements to determine surface area and porosity. |

| Model Pollutant Targets | (e.g., Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B dyes). Standard compounds for benchmarking degradation performance. |

| Sacrificial Reagents | (e.g., methanol, triethanolamine). Consume holes or electrons to study specific half-reactions. |

A typical experimental workflow for assessing photocatalytic degradation activity is as follows [6] [4]:

- Reactor Setup: A common laboratory-scale setup involves a photoreactor (e.g., a beaker or quartz cell) with a light source (e.g., a Xe lamp simulating sunlight, with specific UV or visible light filters).

- Reaction Mixture: The photocatalyst powder (or a functionalized fabric) is dispersed in an aqueous solution of a target pollutant (e.g., methylene blue at a concentration of ~10 mg/L).

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: The suspension is stirred in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish an equilibrium of pollutant adsorption on the catalyst surface.

- Irradiation: The light source is turned on to initiate the photocatalytic reaction. Aliquots of the solution are taken at regular time intervals.

- Analysis: The concentration of the remaining pollutant in each aliquot is measured, typically using UV-Vis spectroscopy by tracking the characteristic absorption peak of the dye. The degradation efficiency (η) is calculated as: η (%) = [(C₀ - Cₜ) / C₀] × 100, where C₀ is the initial concentration and Cₜ is the concentration at time t.

Metal oxides offer a compelling combination of abundance, stability, and cost-effectiveness, establishing them as foundational materials in photocatalysis research. While intrinsic properties like electronic configuration dictate fundamental performance limits, advanced strategies such as doping and heterojunction engineering provide powerful pathways for activity enhancement. The ongoing refinement of single-atom catalysts and the precise engineering of interfaces represent the cutting edge of this field, aiming to bridge the gap between laboratory demonstrations and scalable, real-world applications in environmental remediation and renewable energy.

The Critical Role of Bandgap Engineering in Photocatalytic Activity

Bandgap engineering is a cornerstone of modern photocatalysis, enabling the precise manipulation of a semiconductor's electronic structure to optimize its performance for energy conversion and environmental remediation. By modifying the bandgap energy and the positions of the valence and conduction bands, researchers can enhance a material's ability to absorb visible light, improve the separation of photogenerated charge carriers, and ultimately increase the efficiency of photocatalytic reactions such as hydrogen production and pollutant degradation [8] [9]. This comparative guide objectively analyzes the performance of various bandgap-engineered photocatalysts, focusing on metal-doped metal oxides and other strategic material systems, to provide researchers with a clear understanding of their capabilities based on experimental data.

The fundamental principle driving photocatalysis is the absorption of photons with energy equal to or greater than the semiconductor's bandgap, which promotes electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating electron-hole pairs that drive redox reactions [10] [9]. However, most native metal oxide semiconductors possess wide bandgaps that limit their activity to ultraviolet light, which constitutes only about 5% of the solar spectrum [8] [10]. Bandgap engineering addresses this critical limitation through various strategies, including elemental doping, solid solution formation, and heterostructure construction, each offering distinct pathways to enhance photocatalytic performance for specific applications.

Fundamentals of Bandgap Engineering

Bandgap engineering encompasses multiple sophisticated approaches to tailor the electronic properties of semiconductors:

Elemental Doping: Introducing foreign atoms into a semiconductor lattice can create new energy states within the bandgap, effectively reducing the energy required for electron excitation and extending light absorption into the visible range. Different dopants function through distinct mechanisms; for instance, Mn doping in CdS modifies its electronic structure to enhance visible light absorption [11], while Ta/Sb doping in Nb₃O₇(OH) relocates both the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum, decreasing the bandgap from 1.7 eV to approximately 1.2 eV [12].

Solid Solution Formation: Combining two or more semiconductors with different bandgap energies can create materials with continuously tunable band structures. In Zn₁₋ₓCdₓS solid solutions, the bandgap can be precisely controlled from 2.39 eV (CdS) to 3.73 eV (ZnS) by adjusting the Zn/Cd ratio [13]. This approach simultaneously engineers light absorption and redox potential while facilitating charge separation through spontaneously formed homojunctions [13].

Heterostructure Construction: Engineering interfaces between different semiconductors enables sophisticated charge transfer pathways, such as type-II band alignment or Z-scheme mechanisms, which effectively separate photogenerated electrons and holes to suppress their recombination [11] [14]. For example, constructing a Z-scheme heterojunction between MnₓCd₁₋ₓS and CoP significantly enhances photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance [11].

The following diagram illustrates the primary bandgap engineering strategies and their effects on the electronic structure of semiconductors:

Comparative Performance of Bandgap-Engineered Photocatalysts

Metal-Doped Metal Oxide Systems

Table 1: Performance comparison of metal-doped metal oxide photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Dopant/Modification | Bandgap Change | Photocatalytic Performance | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb₃O₇(OH) | Ta doping (4.16%) | 1.7 eV → 1.266 eV | Enhanced visible light absorption & charge carrier mobility | DFT calculations (TB-mBJ+SO) | [12] |

| Nb₃O₇(OH) | Sb doping (4.16%) | 1.7 eV → 1.203 eV | Improved electrical conductivity & visible light activity | DFT calculations (TB-mBJ+SO) | [12] |

| CdS | Mn doping (Mn₀.₃Cd₀.₇S) | Bandgap engineered for visible light | H₂ production: 10,937.3 μmol/g/h (6.7× higher than CdS) | Shale gas wastewater, visible light | [11] |

| TiO₂ | Various dopants | Wide → Narrow bandgap | Enhanced dye degradation under visible light | Multiple literature studies | [8] [9] |

Solid Solution and Composite Systems

Table 2: Performance comparison of solid solution and composite photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Composition | Bandgap Energy | Photocatalytic Performance | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn₁₋ₓCdₓS | Zn₀.₅Cd₀.₅S | 2.67 eV | Simultaneous H₂ & glyceric acid production | Glycerol photoreforming | [13] |

| Zn₁₋ₓCdₓS | CdS | 2.39 eV | Limited UV-visible activity | Reference material | [13] |

| Zn₁₋ₓCdₓS | ZnS | 3.73 eV | UV-only activity | Reference material | [13] |

| MoS₂ | Monolayer | ~1.8 eV (A-exciton) | Spatial separation of oxidation and reduction sites | H₂ production from water | [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hydrothermal Synthesis of Metal-Doped Photocatalysts

The synthesis of metal-doped photocatalysts typically employs hydrothermal methods to achieve precise crystallographic control. For MnₓCd₁₋ₓS synthesis [11]:

Precursor Preparation: Dissolve appropriate molar ratios of manganese acetate tetrahydrate (Mn(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O) and cadmium acetate dihydrate (Cd(CH₃COO)₂·2H₂O) in deionized water under constant stirring.

Sulfur Source Addition: Gradually introduce sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na₂S·9H₂O) as a sulfur source into the metal ion solution, resulting in immediate precipitate formation.

Hydrothermal Treatment: Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 160-200°C for 12-24 hours to facilitate crystal growth and dopant incorporation.

Product Recovery: Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation or filtration, wash thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol, and dry at 60-80°C to obtain the final photocatalyst powder.

For Zn₁₋ₓCdₓS solid solutions, a similar hydrothermal process is employed using zinc acetate dihydrate, cadmium acetate dihydrate, and thioacetamide as precursors, with the specific Zn/Cd ratio determining the final band structure [13].

Photocatalytic Performance Evaluation

Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Protocol [11]:

Reactor Setup: Utilize a gas-closed circulation system with a top-window Pyrex reactor connected to a gas chromatography system for automated gas analysis.

Reaction Mixture: Disperse 50 mg of photocatalyst in 100 mL of aqueous solution containing sacrificial agents (e.g., 0.35 M Na₂S and 0.25 M Na₂SO₃).

Light Source: Employ a 300 W Xe lamp with a 420 nm cutoff filter to provide visible light irradiation, maintaining constant stirring during illumination.

Gas Analysis: Periodically sample the headspace gas (every 30 minutes) using a gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector to quantify hydrogen production.

Dye Degradation Protocol [8] [9]:

Pollutant Solution: Prepare an aqueous solution of the target organic pollutant (dye, pharmaceutical, or POP) at concentrations ranging from 10-50 mg/L.

Photocatalyst Loading: Add photocatalyst at typically 0.5-1.0 g/L concentration to the pollutant solution.

Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Stir the mixture in darkness for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption equilibrium before illumination.

Light Irradiation: Expose the mixture to visible light illumination (typically using a Xe lamp with appropriate filters) while maintaining constant stirring and temperature control.

Sample Analysis: Withdraw aliquots at regular intervals, remove photocatalyst particles by centrifugation or filtration, and analyze supernatant concentration using UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC.

The following workflow diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental process for evaluating photocatalytic materials:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for photocatalyst development

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Cadmium acetate dihydrate, Zinc acetate dihydrate, Manganese acetate tetrahydrate, Niobium salts | Source of metal cations in photocatalyst structure | High purity (>99%), solubility in aqueous/organic solvents |

| Dopant Sources | Tantalum precursors, Antimony precursors, Transition metal salts | Bandgap modification through elemental doping | Controlled oxidation states, compatible ionic radii |

| Sulfur Sources | Sodium sulfide nonahydrate, Thioacetamide | Provide sulfur anions for metal sulfide formation | Controlled decomposition, uniform reactivity |

| Sacrificial Agents | Sodium sulfite, Sodium sulfide, Triethanolamine | Electron donors or hole scavengers to enhance charge separation | Appropriate redox potential, non-toxic byproducts |

| Pollutant Models | Methylene blue, Rhodamine B, Tetracycline, Phenol | Standard compounds for photocatalytic activity evaluation | Known degradation pathways, representative structures |

| Structural Directing Agents | Various surfactants, Templates | Control morphology and surface area during synthesis | Selective adsorption, thermal stability |

Bandgap engineering represents a powerful strategy for enhancing the photocatalytic performance of semiconductor materials, with different approaches offering distinct advantages for specific applications. Metal doping effectively reduces bandgap energy and extends light absorption into the visible region, as demonstrated by the significantly enhanced hydrogen production of MnₓCd₁₋ₓS compared to pristine CdS [11]. Solid solutions like Zn₁₋ₓCdₓS provide continuously tunable bandgaps and redox potentials, enabling simultaneous optimization of light absorption and charge separation [13]. Meanwhile, advanced heterostructures and 2D materials offer unprecedented control over charge carrier dynamics and reactive site engineering [15] [14].

The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that optimal photocatalytic performance requires careful balancing of bandgap narrowing with adequate redox potential preservation. While narrower bandgaps enhance visible light absorption, they may compromise the thermodynamic driving force for specific redox reactions. Future research directions should focus on developing more precise doping techniques, exploring multi-element doping strategies, designing sophisticated heterostructures with controlled interfaces, and applying machine learning approaches to predict optimal material compositions [10] [14]. As characterization techniques continue to advance, particularly in situ and operando methods, our understanding of structure-activity relationships in bandgap-engineered photocatalysts will further mature, enabling the rational design of next-generation materials for sustainable energy and environmental applications.

In the field of photocatalysis, the performance of metal oxide-based materials is not inherent but is governed by a complex interplay of several key physicochemical parameters [1]. Among these, surface area, crystallinity, and charge carrier mobility are fundamental properties that critically determine the efficiency of photocatalytic reactions, from environmental remediation to renewable energy production [1] [16]. The rational design of high-performance photocatalysts requires a deep understanding of how these parameters interconnect and influence the underlying mechanisms of charge generation, separation, transport, and surface reactions [1] [16]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these parameters, offering experimental data and methodologies to aid researchers in the strategic optimization of metal oxide photocatalysts for advanced applications.

Comparative Analysis of Key Parameters

The following section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of how surface area, crystallinity, and charge carrier mobility individually and collectively impact photocatalytic performance.

Surface Area

The specific surface area of a photocatalyst is a primary determinant for the availability of active sites where photocatalytic reactions occur [1] [16]. A higher surface area generally facilitates greater adsorption of reactant molecules (e.g., pollutants, water, CO2) and provides more locations for photocatalytic redox reactions to proceed [16] [17].

Table 1: Impact of Surface Area on Photocatalytic Performance

| Material | Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Synthesis Method | Photocatalytic Reaction | Performance Metric | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeO₂ Nanorods (NRs) | 87.1 | Hydrothermal | NO Oxidation | ~45% NO removal | Superior activity linked to high surface area and oxygen vacancies. | [18] |

| CeO₂ Nanoparticles (NPs) | 63.5 | Hydrothermal | NO Oxidation | ~25% NO removal | Lower activity compared to NRs. | [18] |

| Aggregated TiO₂ (P23) | Similar to P25 (theoretically) | Thermal Decomposition | Sulfathiazole Degradation | Lower efficiency | Significant aggregation in solution reduced accessible surface area, impairing performance. | [19] |

| Metal Oxide Nanocomposites | Significantly Enhanced | Various (e.g., with carbon materials) | Pollutant Degradation / H₂ Production | Highly Improved | Composite structures prevent nanoparticle agglomeration, maximizing active sites. | [16] |

Crystallinity

Crystallinity refers to the degree of structural order in a solid material. High crystallinity typically implies fewer bulk defects, which can function as recombination centers for photogenerated charge carriers [1]. The crystal phase (polymorph) is equally critical, as it directly influences the electronic band structure and charge mobility [1] [19].

Table 2: Impact of Crystallinity and Crystal Phase on Photocatalytic Performance

| Material | Crystalline Phase | Key Crystallinity Feature | Photocatalytic Reaction | Performance Implication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ Samples | Anatase, Rutile, or Mixed | Phase composition and crystallite size | Degradation of emerging contaminants | Efficiency varied with polymorphic phase; no clear size-bandgap correlation due to phase mixing. | [19] |

| CeO₂ Nanorods (NRs) | Fluorite Cubic | Predominant exposure of (110) crystal facets | NO Oxidation & CO₂ Conversion | Highly active facets favor oxygen vacancy formation and reactant adsorption. | [18] |

| General Metal Oxides | Various | High crystallinity | General Photocatalysis | Reduces bulk charge recombination losses, improving charge carrier mobility and lifetime. | [1] |

| ZrO₂ Thin Films | Crystalline | Improved grain alignment post-annealing | Electrical Properties | Annealing reduced defect density, enhancing charge carrier mobility. | [20] |

Charge Carrier Mobility

Charge carrier mobility dictates how efficiently photogenerated electrons and holes can migrate to the catalyst surface to drive reactions. Low mobility leads to high recombination rates, wasting the absorbed light energy as heat [1] [16]. Strategies such as constructing heterojunctions, doping, and morphology control are employed to enhance this parameter [16].

Table 3: Impact of Charge Carrier Mobility and Separation Strategies

| Material/Strategy | Approach to Enhance Mobility/Separation | Photocatalytic Reaction | Performance Outcome | Underlying Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOx-based Heterojunctions | Coupling with other semiconductors | Pollutant degradation, H₂ production | Highly enhanced activity | Synergistic effects improve charge separation and broaden light absorption. | [16] |

| CeO₂ with Oxygen Vacancies | Defect Engineering (e.g., Mn-doping) | CO₂ conversion, NO oxidation | Enhanced performance | Oxygen vacancies reduce e–/h+ recombination rate and expand light response. | [18] |

| Annealed ZrO₂ Films | Post-deposition annealing | Capacitor performance | Increased capacitance | Reduced defect density and improved charge carrier mobility. | [20] |

| Bioglass with ZrO₂ | Incorporation of metal ions | Bioactivity & Antibacterial | Enhanced conductivity | Increased non-bridging oxygen content improved ion mobility. | [21] |

Interrelationship of Key Parameters

The optimization of photocatalysts requires a holistic view, as the key parameters are deeply interconnected. Engineering one parameter can directly affect the others, sometimes creating trade-offs [1]. For instance, while high-temperature processing can improve crystallinity, it may also cause sintering, reducing the surface area [1]. Similarly, creating a high surface area nanostructured material with abundant pores can introduce defects that hinder charge carrier mobility [1] [16]. The most effective strategies, such as forming crystallographically controlled heterojunctions, successfully enhance multiple parameters simultaneously—maintaining a high surface area, providing pathways for efficient charge separation and mobility, and leveraging the beneficial crystallographic properties of each component [16] [18]. The diagram below illustrates this complex interplay and the strategies used to manage it.

Figure 1: Interplay of Key Parameters in Photocatalyst Design

This diagram illustrates the synergistic and often competing relationships between surface area, crystallinity, and charge carrier mobility. Effective photocatalyst design requires balancing these parameters through targeted engineering strategies to achieve optimal overall performance.

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Analysis

Accurate characterization of these key parameters is fundamental to establishing structure-activity relationships. Below are detailed methodologies for core experimental analyses cited in this guide.

Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis for Morphological Control

This protocol is adapted from studies on CeO₂, which successfully produced distinct morphologies (nanorods, nanoparticles) to investigate the effect of surface area and exposed crystal facets [18].

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve a specific mass of the metal precursor (e.g., Cerium(III) nitrate hexahydrate, Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O) in deionized water using a stirrer for 15 minutes to ensure complete dissolution.

- pH Adjustment: Add a mineralizer (e.g., Sodium hydroxide, NaOH) to the solution to create an alkaline environment, which is critical for directing crystal growth and morphology.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the homogeneous solution to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. Seal the autoclave and place it in a preheated oven.

- For Nanorods (NRs): Use specific precursor/NaOH ratios (e.g., 4.0 g Ce-precursor, 8.0 g NaOH) and react at a defined temperature and time (e.g., 100°C for 24 hours) [18].

- For Nanoparticles (NPs): Use different ratios (e.g., 1.0 g Ce-precursor, 0.2 g NaOH) and react at a lower temperature and/or shorter time (e.g., 100°C for 6 hours) [18].

- Washing and Drying: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool naturally to room temperature. Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation (e.g., 8000 rpm for 10 minutes). Wash the precipitate several times with deionized water and absolute ethanol to remove impurities. Dry the final product in an oven at 60°C for 12 hours.

- Calcination: Optional step: Calcine the dried powder in a muffle furnace at a specified temperature (e.g., 400-500°C for 2 hours) to enhance crystallinity.

Protocol: Electrical Characterization via Impedance Spectroscopy

This method is used to probe electrical properties, including conductivity and charge carrier mobility, in materials like bioglass and thin films [21] [20].

- Sample Preparation:

- For powders: Pelletize the sample under high pressure (e.g., 5-10 tons) to form a dense disc. Apply a conductive coating (e.g., silver paste) on both parallel surfaces to form electrodes.

- For thin films: Use capacitors with a Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) structure, where the metal oxide (e.g., ZrO₂) is the insulator sandwiched between two electrodes (e.g., Aluminum) [20].

- Equipment Setup: Connect the sample to an impedance analyzer (e.g., Agilent 4294A) using a two-probe or four-probe configuration. Place the sample in a shielded probe station to minimize noise.

- Data Acquisition: Measure the impedance over a wide frequency range (e.g., 40 Hz to 2 MHz) at a small AC signal amplitude (e.g., 50 mV). The measurement can be performed at room temperature or across a temperature range to study thermal activation.

- Data Analysis: Model the obtained data using an equivalent circuit (e.g., a resistor and capacitor in parallel) to extract parameters like bulk resistance (R). The conductivity (σ) can be calculated using the formula: σ = d / (R × A), where d is the sample thickness and A is the electrode area. Analysis of the frequency response can also provide insights into charge carrier mobility and relaxation mechanisms.

Protocol: Photocatalytic Performance Testing for Pollutant Degradation

A standard test to evaluate the efficacy of a photocatalyst for degrading organic pollutants in water [19] [17].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare an aqueous solution of a model pollutant (e.g., sulfathiazole, bisphenol, paracetamol) at a specific concentration (e.g., 10 mg/L). Add a precise mass of the photocatalyst (e.g., 100 mg) to a volume of the pollutant solution (e.g., 100 mL) in a photoreactor vessel.

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Before illumination, stir the suspension in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish an adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the catalyst and the pollutant.

- Illumination: Turn on the light source (e.g., a Xe lamp simulating solar light, or a specific UV/visible light source). Maintain constant stirring throughout the illumination to keep the catalyst suspended.

- Sampling: At regular time intervals (e.g., every 15-30 minutes), withdraw a small aliquot (e.g., 3-5 mL) of the suspension. Immediately separate the catalyst from the solution by filtration (using a 0.22 μm syringe filter) or centrifugation.

- Analysis: Analyze the clear filtrate using an appropriate analytical technique (e.g., UV-Vis spectrophotometry to monitor the decrease in characteristic absorption peak, or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for more accurate quantification). Calculate the degradation efficiency as (C₀ - C)/C₀ × 100%, where C₀ is the initial concentration and C is the concentration at time t.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions, as derived from the experimental protocols and studies cited in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cerium(III) Nitrate Hexahydrate | Metal precursor for the synthesis of ceria (CeO₂) nanostructures. | Hydrothermal synthesis of CeO₂ nanorods and nanoparticles [18]. |

| Titanium-based Precursors | Source of titanium for forming TiO₂ photocatalysts. | Sol-gel and thermal decomposition synthesis of TiO₂ nanoparticles [19]. |

| Zirconium Dioxide (ZrO₂) | Dopant or composite material to enhance electrical and biological properties. | Incorporated into 45S5 Bioglass to improve conductivity and bioactivity [21]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Mineralizer/Precipitating agent to control pH and morphology during synthesis. | Creating an alkaline environment in hydrothermal synthesis of CeO₂ [18]. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Solution mimicking human blood plasma for in-vitro bioactivity assessment. | Evaluating the formation of hydroxyapatite on bioglass surfaces [21]. |

| Model Organic Pollutants | Target compounds for evaluating photocatalytic degradation efficiency. | Sulfathiazole, Bisphenol, Paracetamol used in degradation tests [19]. |

| Aluminum (Al) Targets | Electrode material for physical vapor deposition (e.g., sputtering). | Fabricating electrodes for thin-film capacitor structures [20]. |

Metal oxides represent a cornerstone class of materials in the field of photocatalysis, offering a versatile platform for addressing pressing global challenges in environmental remediation and renewable energy. Their significance stems from a combination of remarkable stability, abundance, cost-effectiveness, and tunable electronic structures that can be engineered for specific redox reactions [1]. Among the myriad of photocatalytic materials investigated, titanium dioxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), tungsten trioxide (WO3), and chromium oxide (Cr2O3) have received particular attention from researchers and scientists focused on developing top-tier nanomaterials that are environmentally friendly, multifunctional, and high-performing [22]. The fundamental principle underlying their photocatalytic activity involves the generation of electron-hole pairs upon light absorption, which subsequently drive chemical transformations for applications ranging from water purification and air detoxification to renewable fuel production [1].

The broader thesis of comparative photocatalytic activity of metal-doped metal oxides research centers on understanding, enhancing, and implementing these materials for industrial applications, given their numerous attractive attributes [22]. This comparative guide objectively examines the performance of these four common metal oxide platforms, providing supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to offer researchers, scientists, and development professionals a comprehensive resource for selecting and optimizing photocatalysts for specific applications. The continuous pursuit of high-performance photocatalysts has revealed inherent trade-offs, where improved light absorption can inadvertently lead to higher recombination rates or decreased stability, underscoring the need for a systematic understanding of how multiple parameters interact to control catalytic efficiency [1].

Fundamental Properties and Characteristics

The photocatalytic performance of metal oxides is intrinsically linked to their fundamental structural, electronic, and optical properties. Each material possesses a unique combination of characteristics that dictates its suitability for various photocatalytic applications.

TiO2 stands out as a promising material owing to its remarkable stability, non-toxic nature, cost-effectiveness, and abundant presence on Earth [22]. It exists primarily in three crystalline phases: anatase, rutile, and brookite, with anatase being the most photocatalytically active. However, TiO2's photocatalytic activity is limited primarily to the UV region of the solar spectrum due to its noteworthy band gap energy of 3.2 eV [22]. Additionally, TiO2 is susceptible to accelerated recombination of exciton species, which hinders its effectiveness [22].

ZnO is an inexpensive, wide band gap metal oxide (3.37 eV) whose photocatalytic behavior has been found to be similar to TiO2 [23]. It possesses a wurtzite crystal structure that facilitates rapid electron transport, though it suffers from photocorrosion in acidic environments, potentially limiting its long-term stability in certain applications [23].

WO3 presents itself as a viable option for constructing heterojunction catalysts with a band gap that exhibits variation depending on its layer structure [22]. It stands at 2.6 eV for the bulk form and increases to 3.6 eV for composites, enabling better utilization of the visible light spectrum compared to TiO2 and ZnO [22]. WO3 is claimed to be a proper material for photoelectrocatalytic applications due to its high resistance to photocorrosion, stability in acidic media, and good electron transport properties [24].

Cr2O3 is a transition metal oxide with a corundum-type crystal structure and a band gap of approximately 3.4-3.6 eV, though doping strategies can significantly reduce this value to enhance visible light absorption [25]. Research has demonstrated that Ba-doped Cr2O3 photocatalysts exhibit remarkable efficacy in degrading Congo Red dye, achieving an impressive efficiency of 95% under visible light illumination [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Common Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Property | TiO2 | ZnO | WO3 | Cr2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure | Anatase, Rutile, Brookite | Wurtzite | Cubic ReO3/Monoclinic | Corundum (α-phase) |

| Band Gap (eV) | 3.0-3.2 | 3.37 | 2.6-3.6 | 3.4-3.6 (tunable with doping) |

| Primary Radiation Absorption | UV | UV | Visible/UV | Visible/UV (with doping) |

| Stability | Excellent | Good (except in acids) | Excellent in acidic media | Good |

| Electron Transport | Moderate | Good | Good | Moderate |

| Toxicity | Non-toxic | Non-toxic | Non-toxic | Low toxicity |

Comparative Photocatalytic Performance

The efficacy of metal oxide photocatalysts is typically evaluated through standardized degradation tests using model organic pollutants under controlled illumination conditions. Comparative studies reveal significant performance variations based on the specific material properties, synthesis methods, and experimental conditions.

In the degradation of azo dyes, which represent a significant class of water pollutants from textile industries, both TiO2 and ZnO have demonstrated substantial photocatalytic activity. Studies comparing nanocrystalline TiO2 and ZnO particles prepared through sol-gel and precipitation methods respectively showed that ZnO exhibited superior performance for both Coralene Red F3BS and Acid Red 27 dyes compared to TiO2 [23]. The enhanced performance of ZnO was attributed to its more efficient generation of electron-hole pairs under UV illumination, though its susceptibility to dissolution in acidic conditions might limit practical applications.

Research on WO3-based composites has revealed their exceptional potential when properly engineered. Studies on WO3:Fe/TiO2 (TW) nanocomposites demonstrated that their microstructural evolution and photocatalytic performance are strongly influenced by annealing temperature [22]. When the annealing temperature was raised from 300°C to 500°C, the crystallite size increased from 25 nm to 48 nm, and the band gap widened from 2.34 eV to 2.88 eV [22]. Notwithstanding the increase in particle size, the TW500 sample achieved a reaction rate constant that was over three times higher than that of the TW300 sample, highlighting the complex interplay between structural and electronic properties in determining photocatalytic efficiency [22].

For Cr2O3, doping strategies have proven highly effective in enhancing photocatalytic performance. Ba-doped Cr2O3 photocatalysts synthesized via a low-cost, simple sol-gel method demonstrated remarkable efficacy in degrading Congo Red dye under visible light, achieving 95% degradation compared to 66.25% for pure Cr2O3 [25]. The boosted performance was ascribed to changes in structure, reduced energy band gap, restricted recombination, and efficient transportation and separation of charge carriers at the surface [25].

Table 2: Comparative Photocatalytic Degradation Performance

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Light Source | Degradation Efficiency | Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 (Commercial) | Imazapyr herbicide | UV | Baseline | Varies | [26] |

| TiO2/CuO composite | Imazapyr herbicide | UV | Highest efficiency | Varies | [26] |

| ZnO nanoparticles | Acid Red 27 dye | UV | Superior to TiO2 | Varies | [23] |

| WO3:Fe/TiO2 (500°C annealed) | Methylene Blue | UV | ~3x higher than 300°C sample | Varies | [22] |

| Ba-doped Cr2O3 | Congo Red dye | Visible | 95% | 140 min | [25] |

| Pure Cr2O3 | Congo Red dye | Visible | 66.25% | 140 min | [25] |

A comparative investigation of TiO2-based composites, including those with ZrO2, ZnO, Ta2O3, SnO, Fe2O3, and CuO, assessed their potential for enhancing photocatalytic applications through degradation of the herbicide Imazapyr under UV illumination [26]. Results revealed that all composites exhibited more effective photo-activity than commercial Hombikat UV-100 TiO2, with performance following the order: TiO2/CuO > TiO2/SnO > TiO2/ZnO > TiO2/Ta2O3 > TiO2/ZrO2 > TiO2/Fe2O3 > Hombikat TiO2-UV100 [26]. The superior performance of these composites was attributed to enhanced light absorption and improved charge separation at the heterojunction interfaces.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis Techniques

Various synthesis methods are employed to prepare metal oxide photocatalysts with tailored properties, each offering distinct advantages for controlling morphological and structural characteristics.

The sol-gel method is particularly advantageous for TiO2 synthesis due to its simple process, low cost, and low-temperature requirements [23]. A typical protocol involves preparing a sol of TiO2 by dissolving titanium tetra isopropoxide (12 mL) in isopropanol (10 mL), followed by addition of water (150 mL) and acetic acid (5 mL) as a chelating agent [23]. The mixed solution is heated at 80°C for 3 hours with vigorous stirring, followed by calcination to obtain the crystalline product.

For ZnO nanoparticles, the precipitation method is most suitable because of its simplicity and cost-effectiveness [23]. This typically involves dissolving zinc nitrate in distilled water and adding sodium hydroxide solution dropwise under constant stirring, followed by washing and calcination of the precipitated powder.

Electrochemical anodization under hydrodynamic conditions using a rotary disk electrode has been successfully employed for synthesizing WO3 and TiO2 nanostructures [24]. For WO3 nanostructures, anodization of tungsten is typically carried out at 375 rpm, applying 20 V for 4 hours using an electrolyte of 1.5 M methanosulfonic acid and 0.01 M citric acid at 50°C [24]. After anodization, the WO3 nanostructures are annealed for 4 hours at 600°C in an air atmosphere to achieve the desired crystallinity.

The sol-gel route is also effective for producing doped Cr2O3 photocatalysts, as demonstrated in the synthesis of Ba-doped Cr2O3, which offers a low-cost, simple approach that yields catalysts with enhanced visible light activity [25].

Characterization Methods

Comprehensive characterization is essential for correlating material properties with photocatalytic performance:

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) determines crystalline phase, crystallite size, and phase purity [22] [26].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) reveal morphological features, particle size distribution, and structural details at micro- and nano-scale dimensions [22] [26].

- UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy determines band gap energy and optical absorption characteristics [22].

- Photoelectrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (PEIS) analyzes electrochemical and photoelectrochemical behavior, including charge transfer resistance and recombination dynamics [24].

- Raman Spectroscopy provides information about crystal structure, phase composition, and defect states [24].

Photocatalytic Activity Assessment

Standardized protocols for evaluating photocatalytic activity typically involve the degradation of model organic pollutants under controlled illumination:

A common methodology employs a photoreactor equipped with appropriate light sources (UV or visible). The photocatalyst is dispersed in an aqueous solution of the target pollutant at a specific concentration (typically 10-20 ppm) [24] [26]. The suspension is stirred in the dark for 30 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium before illumination begins. Samples are periodically withdrawn, centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and analyzed by techniques like UV-Vis spectroscopy or high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC-MS) to determine pollutant concentration [24] [26].

For photoelectrocatalytic (PEC) degradation, which combines electrolytic and photocatalytic processes, the catalyst is immobilized on a conductive substrate as a photoanode [24]. The PEC degradation is typically carried out under lighting conditions (AM 1.5) at an applied potential (e.g., 0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a specified duration, with the degradation progress monitored through analytical techniques [24].

Diagram Title: Photocatalytic Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in metal oxide photocatalysis requires specific materials and reagents tailored to synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Precursors | TiO2 synthesis | Titanium tetra isopropoxide (TTIP), titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) |

| Zinc Precursors | ZnO synthesis | Zinc nitrate, zinc acetate, zinc chloride |

| Tungsten Sources | WO3 synthesis | Tungsten metal foils for anodization, tungsten salts |

| Chromium Compounds | Cr2O3 synthesis | Chromium salts, chromium nitrate nonahydrate |

| Dopant Sources | Material modification | Fe(III) oxide, Ba compounds, CuO, etc. for enhancing properties |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Morphology control | Citric acid, acetic acid, ammonium fluoride |

| Model Pollutants | Performance evaluation | Methylene Blue, Congo Red, Imazapyr, Rhodamine B |

| Electrolytes | Photoelectrocatalysis | H2SO4, NaOH, Na2SO4 at various concentrations and pH |

| Calibration Standards | Analytical quantification | Certified reference materials for HPLC, ICP-MS |

Performance Optimization Strategies

Enhancing the photocatalytic efficiency of metal oxides typically involves strategic modifications to address inherent limitations such as wide band gaps and rapid electron-hole recombination.

Doping with transition metals or non-metals represents a primary strategy for improving visible light absorption and charge separation. Iron doping in WO3/TiO2 systems has been shown to alter the band gap energy in the vicinity of the visible light spectrum, thereby enhancing photocatalytic performance [22]. Similarly, Ba doping in Cr2O3 resulted in structural changes, reduced energy band gap, restricted recombination, and efficient transportation and separation of charge carriers at the surface [25].

Heterojunction formation between different metal oxides creates synergistic effects that enhance photocatalytic activity by improving charge separation, broadening light absorption, and increasing surface area [16]. The construction of WO3:Fe/TiO2 nanocomposites takes advantage of their beneficial band alignments, with extensive research undertaken on oxide/TiO2 composites in the context of photocatalytic processes aimed at eliminating dye pollutants [22]. Similarly, TiO2/ZnO hybrid nanostructures have been developed to increase TiO2 photoelectrochemical properties [24].

Annealing temperature control during synthesis significantly impacts microstructural evolution and photocatalytic performance. Studies on WO3:Fe/TiO2 nanocomposites revealed that increasing the annealing temperature from 300°C to 500°C caused the band gap to widen from 2.34 eV to 2.88 eV, with the higher temperature sample exhibiting a reaction rate constant over three times higher despite increased particle size [22].

Morphological engineering through nanostructuring approaches (nanoparticles, nanorods, nanotubes) increases surface area and exposes more active sites for photocatalytic reactions [26]. The fabrication of nanostructured electrodes with high surface area has been shown to improve photoelectrocatalytic performance for degradation of persistent organic pollutants [24].

The comparative analysis of TiO2, ZnO, WO3, and Cr2O3 photocatalysts reveals a complex landscape where each material offers distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications. TiO2 remains the most extensively studied photocatalyst due to its excellent stability and nontoxic nature, though its wide band gap limits solar energy utilization. ZnO demonstrates comparable performance to TiO2 in UV-driven processes but faces challenges with stability in acidic conditions. WO3 stands out for its visible light response and exceptional stability in acidic media, making it ideal for composite structures. Cr2O3, particularly when doped with appropriate elements, shows remarkable enhancement in visible light activity, achieving degradation efficiencies up to 95% for specific dyes.

Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated composite architectures that leverage the complementary properties of these metal oxides, creating Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions that maximize charge separation while maintaining strong redox potentials [16]. The integration of machine learning approaches into experimental workflows shows significant promise for accelerating the optimization of electrocatalysis performance, representing a potential advancement in developing efficient and sustainable photocatalytic technologies [27]. Additionally, greater emphasis on real-world testing conditions, including complex pollutant mixtures and long-term stability assessments, will be crucial for translating laboratory success into practical environmental remediation and energy production applications [1]. As research continues to address the fundamental challenges of charge recombination, limited visible light absorption, and scalability, metal oxide photocatalysts are poised to play an increasingly important role in sustainable water treatment and renewable energy systems.

Heterogeneous photocatalysis using metal oxide semiconductors is a promising advanced oxidation process (AOP) for environmental remediation and energy applications. This technology leverages the unique photoelectrochemical properties of semiconductors to generate powerful reactive species that can degrade persistent organic pollutants [28] [29]. The process begins when a semiconductor material absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, leading to the excitation of electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), thus creating electron-hole pairs [29]. These photogenerated charge carriers then migrate to the catalyst surface where they can participate in redox reactions with adsorbed species, ultimately generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radical anions (O₂•⁻) [28] [29].

The effectiveness of photocatalytic systems depends significantly on the properties of the semiconductor material and operational conditions. Metal oxides, particularly titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), and iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), have emerged as prominent photocatalysts due to their favorable band structures, cost-effectiveness, abundance, and chemical stability [30] [2]. However, these materials face challenges including rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, limited visible light absorption due to wide bandgaps, and low charge carrier mobility [29] [2]. To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed various strategies including doping with metals and non-metals, creating heterojunctions with other semiconductors, surface functionalization, and morphology control [31] [2]. This article examines the fundamental mechanisms driving photocatalysis and compares the performance of various metal-doped metal oxides through experimental data and mechanistic analysis.

Electron-Hole Pair Generation and Charge Carrier Dynamics

Fundamental Principles of Photoactivation

The photocatalytic process initiates with the absorption of photons by a semiconductor catalyst. When the energy of incident photons (hν) matches or exceeds the bandgap energy (E_g) of the semiconductor, electrons (e⁻) are promoted from the valence band to the conduction band, leaving positively charged holes (h⁺) in the valence band [29]. This process creates electron-hole pairs that can migrate to the catalyst surface. The bandgap energy is a critical parameter determining the light absorption capability of the photocatalyst. For instance, TiO₂ has a wide bandgap of approximately 3.2 eV, requiring UV light for activation (λ < 390 nm), which constitutes only a small portion (~5%) of the solar spectrum [30] [29]. This limitation has motivated research into modifying existing photocatalysts or developing new ones with narrower bandgaps suitable for visible light activation [29].

The overall photocatalysis process involves five complementary steps: (1) light harvesting, (2) electron-hole pair generation under light irradiation, (3) charge carrier separation and migration to the photocatalyst surface, (4) oxidation and reduction reactions with surface-adsorbed reactants, and (5) possible recombination of charge carriers on the catalyst surface [29]. The efficiency of photocatalysis depends on the competition between the utilization of charge carriers in surface redox reactions and their recombination, which releases energy as heat or light [31] [28]. Nanoparticles are particularly effective for photocatalysis due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, which reduces the distance charge carriers must travel to reach the surface, thereby decreasing recombination probability [29].

Factors Influencing Charge Carrier Dynamics

Several factors significantly impact the generation, separation, and recombination of electron-hole pairs in semiconductor photocatalysts. The physical structure and composition of the catalyst play crucial roles in determining photocatalytic efficiency [31]. Nanoparticles produced by methods such as pulsed electron beam evaporation (PEBE) often form mesoporous aggregates with high specific surface area and absorption properties, leading to increased concentrations of surface-active sites per unit mass [31]. Post-synthesis treatments including electron irradiation, thermal annealing, and doping can substantially alter the properties of nanoparticles and consequently their photocatalytic activity [31].

Table 1: Factors Affecting Charge Carrier Dynamics in Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Factor | Effect on Charge Carriers | Influence on Photocatalytic Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size & Surface Area | Smaller particles reduce migration distance for charge carriers to reach surface [29] | Increased surface area provides more active sites for redox reactions [31] |

| Aggregation State | Dense aggregates shield internal particles from illumination, promoting recombination [28] | Optimal dispersion minimizes light shielding and recombination centers [28] |

| Crystal Structure & Defects | Defects can trap charge carriers, reducing recombination [31] [2] | Oxygen vacancies enhance charge separation but excessive defects may act as recombination centers [2] |

| Doping | Creates intermediate energy levels, modifying band structure [31] [29] | Extends light absorption range and facilitates charge separation [31] |

| Heterojunction Formation | Enables spatial separation of electrons and holes [31] [32] | Significantly reduces recombination rate; enhances quantum yield [31] |

Temperature treatment also significantly affects photocatalyst properties. Annealing can influence specific surface area, pore number and size, and structural integrity of nanoparticles [31]. However, excessive annealing temperatures can cause nanoparticle sintering, increasing agglomeration size and reducing active surface area [31]. Studies investigating the dependence of photocatalytic activity on annealing temperature have observed a specific correlation where activity initially increases with temperature then decreases after optimal conditions due to these effects [31].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production Pathways

Primary ROS Formation Mechanisms

Reactive oxygen species are highly oxidative molecules and radicals that play a central role in photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. The primary ROS generated in photocatalytic systems include hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide radical anions (O₂•⁻), singlet oxygen (¹O₂), and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [33] [28]. These species are formed through a series of reactions initiated by photogenerated electrons and holes migrating to the catalyst surface [28].

Photogenerated holes in the valence band can directly oxidize water molecules or hydroxide ions to produce hydroxyl radicals: [ h⁺ + H₂O \rightarrow \bullet OH + H⁺ ] [ h⁺ + OH⁻ \rightarrow \bullet OH ]

Meanwhile, photogenerated electrons in the conduction band can reduce molecular oxygen to form superoxide radical anions: [ e⁻ + O₂ \rightarrow O₂\bullet⁻ ]

These primary reactive species can then participate in further reactions to form secondary ROS. For instance, superoxide radical anions can undergo disproportionation to form hydrogen peroxide, which can subsequently be cleaved to yield additional hydroxyl radicals [33] [28]. The relative contribution of different ROS to pollutant degradation depends on the specific photocatalyst, reaction conditions, and the nature of the target pollutant [34].

Table 2: Primary Reactive Oxygen Species in Photocatalytic Systems

| ROS Species | Formation Pathway | Oxidation Potential (V) | Primary Role in Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) | h⁺ + H₂O/OH⁻ → •OH [30] | 2.8 | Non-selective oxidation of organic pollutants [28] |

| Superoxide Anion (O₂•⁻) | e⁻ + O₂ → O₂•⁻ [30] | ~1.3 | Selective reduction; generates secondary ROS [33] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | O₂•⁻ + 2H⁺ + e⁻ → H₂O₂ or O₂•⁻ + O₂•⁻ + 2H⁺ → H₂O₂ + O₂ [33] | 1.78 | Precursor for •OH generation via Fenton reactions [33] |

| Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) | Energy transfer from photoexcited catalyst to O₂ [33] | ~1.2 | Selective oxidation of electron-rich compounds [33] |

Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles can generate ROS through various mechanisms beyond direct photocatalysis, including corrosion, Fenton reactions, Haber-Weiss reactions, and interactions with biomolecules [33]. For example, the corrosion of metals like copper and silver in aqueous environments can produce H₂O₂ as a main side product without forming O₂•⁻ intermediates [33]. Additionally, dissolved metal ions from nanoparticle surfaces can participate in Fenton-like reactions where H₂O₂ is transformed into hydroxyl radicals [33].

Enhanced ROS Generation Through Material Engineering

Various strategies have been developed to enhance ROS generation in photocatalytic systems. Doping with transition metals (e.g., Fe, Ni, Cu, Mo, Pd) can impart favorable physicochemical features including narrowed optical band gaps, increased oxygen vacancy concentrations, and reduced charge recombination [35]. For instance, doping ZrO₂ nanoparticles with F⁻ ions induced a transition from tetragonal to monoclinic structure, leading to increased photocatalytic activity [31]. Similarly, for Zn₁₋ₓFeₓO nanocomposite produced by a chemical method, changes in energy levels and reduction in bandgap were observed [31].

The application of metal nanocoatings (e.g., Au, Ag, Al) onto photocatalyst surfaces provides another effective approach for enhancing ROS generation [31]. Introducing a metal phase facilitates electron accumulation by metal particles, helping to overcome the potential barrier of many reduction reactions and reducing the probability of electron-hole recombination within the semiconductor bulk [31]. The electronic contact between metal and semiconductor results in formation of a common Fermi level for the nanocomposite, positioned between the Fermi levels of the original components [31].

Creating heterojunctions between different semiconductors represents a particularly effective strategy for enhancing ROS production. When two semiconductors with different band structures combine in a single nanocomposite, charge carriers generated by light absorption become localized on different components, enabling spatial and energy separation of charges [31]. This separation reduces the likelihood of recombination of photogenerated charges while increasing the quantum yield of photocatalytic reactions [31]. In such binary nanocomposites, a high-bandgap semiconductor is typically paired with a low-bandgap semiconductor possessing a more negative conduction band level, enhancing light conversion efficiency and broadening the photosensitivity range [31].

Comparative Performance of Metal-Doped Metal Oxides

Titanium Dioxide-Based Photocatalysts

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) remains the most extensively studied and applied photocatalyst due to its exceptional chemical and photochemical stability, cost-effectiveness, low toxicity, and high activity under UV light [30]. TiO₂ with a bandgap of approximately 3.2 eV can mineralize a broad spectrum of organic contaminants, including herbicides, dyes, pesticides, phenolic compounds, and pharmaceuticals [30]. However, its practical application is limited by its reliance on UV light, which constitutes only a small portion of the solar spectrum [30].

Doping TiO₂ with transition metals has proven effective in enhancing its photocatalytic performance under visible light. Research has shown that TiO₂ doped with transition metals (Fe, Ni, Cu, Mo, Pd) and subsequently modified with 2D Ti₃C₂ MXene significantly enhances peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation under both UV and visible light [35]. Among these dopants, Fe and Ni imparted the most favorable features, including narrowed optical band gaps, increased oxygen vacancy concentrations, and reduced photogenerated charge recombination [35]. Post-synthetic MXene integration further improved interfacial charge separation and visible-light absorption, achieving >99% total organic carbon (TOC) mineralization of a ternary pharmaceutical mixture (tetracycline, levofloxacin, and paracetamol) in real tap water under UV irradiation [35].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Metal-Doped TiO₂ Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Dopant/Modification | Target Pollutant | Degradation Efficiency | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | Fe, Ni | Ternary pharmaceutical mixture | >99% TOC mineralization [35] | Optimal defect structure, enhanced redox activity [35] |

| TiO₂ | MXene modification | Pharmaceuticals in tap water | >95% activity over 5 cycles [35] | Excellent stability with minimal metal leaching [35] |

| TiO₂ (P25) | None (reference) | Model pollutants | Varies with probe compound [28] | Standard reference material for comparative studies [28] |

Experimental studies using P25 Aeroxide TiO₂ suspensions photoactivated by UV-A radiation have demonstrated the production of both photogenerated holes and hydroxyl radicals over time [28]. The interaction between iodide and photogenerated holes was influenced by iodide adsorption on the TiO₂ surface, describable by a Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism [28]. Parameters for this mechanism varied with TiO₂ concentration and irradiation time, highlighting the complex interplay between catalyst properties and reaction conditions in determining photocatalytic efficiency [28].

Zinc Oxide-Based Photocatalysts

Zinc oxide (ZnO) has emerged as a promising alternative to TiO₂ due to its remarkable properties including low cost, high oxidation capability, non-toxic nature, high stability to photocorrosion, and natural abundance [32] [30]. With a bandgap of approximately 3.37 eV, unmodified zinc oxide is not considered a strong photocatalyst under visible light due to its relatively high bandgap and rapid charge carrier recombination rate [32]. Its practical use is strongly limited because it is primarily active in ultraviolet light, which covers only about 5% of the solar spectrum [32].

To address these limitations, researchers have developed ZnO-based composites with various metal oxides. A comparative study of ZnO coupled with different metal oxides (Mn₃O₄, Fe₃O₄, CuO, NiO) in a 1:1 molar ratio revealed distinct performance characteristics [32]. The ZnO/Fe₃O₄ nano-catalyst showed the best photodegradation efficiency for methylene blue under natural solar irradiation [32]. This enhanced performance was attributed to the formation of Fe₃O₄/ZnO as a p/n heterojunction, which reduces the recombination of photo-generated electron/hole pairs and broadens the solar spectral response range [32].

Table 4: Performance of ZnO/Metal Oxide Composites for Methylene Blue Degradation

| Photocatalyst | Bandgap (eV) | Methylene Blue Degradation Efficiency | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO/Fe₃O₄ | Not specified | Highest efficiency [32] | p/n heterojunction reduces e⁻/h⁺ recombination [32] |

| ZnO/Mn₃O₄ | Not specified | Moderate efficiency [32] | Mn₃O₄ bandgap = 2.0 eV [32] |

| ZnO/CuO | Not specified | Moderate efficiency [32] | CuO bandgap = 1.4 eV [32] |

| ZnO/NiO | Not specified | Moderate efficiency [32] | NiO bandgap = 3.5 eV [32] |

| Pure ZnO | ~3.37 [32] | Reference efficiency [32] | Rapid charge carrier recombination [32] |

The hydrothermal synthesis method used to prepare these ZnO-based composites proved effective for creating high-quality binary composites suitable for mass production [32]. The formation of heterostructures between ZnO and various metal oxides resulted in improved charge separation and broader light absorption capabilities, demonstrating the potential of composite materials for enhancing photocatalytic performance [32].

Other Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Beyond TiO₂ and ZnO, researchers have explored numerous other metal oxides for photocatalytic applications. Tungsten trioxide (WO₃) has emerged as a promising alternative due to its capability to absorb visible light, making it more suitable for photocatalytic oxidation of volatile organic pollutants under natural sunlight [30]. Similarly, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have gained significant attention as photocatalysts due to their high photostability, environmental friendliness, and catalytic properties dependent on their shape and size [30].

Cerium oxide (CeO₂)-based photocatalysts have also shown considerable promise. Studies investigating CeO₂ nanoparticles produced by the pulsed electron beam evaporation (PEBE) method demonstrated that doping with transition metals like Ni significantly enhances photocatalytic activity [35]. The Ni–CeO₂–MXene composite was identified as particularly efficient, showing optimal defect structure, redox activity, and electronic conductivity [35]. This catalyst maintained >95% activity over five reuse cycles with minimal leaching, highlighting its potential for practical applications [35].

Lead monoxide (PbO) nanoparticles have attracted research interest due to their exceptional mechanical, optical, and electrical properties [29]. The photocatalytic activity of PbO nanoparticles has been investigated for the degradation of organic pollutants, though detailed performance comparisons with other metal oxides require further research [29].

Experimental Methodologies for Mechanism Study

Probe-Based ROS Detection Methods

Experimental protocols for measuring reactive species generation have been developed using molecular probes that are highly selective chemicals whose reaction products can be easily quantified by spectrophotometric and fluorimetric methods [28]. These protocols represent effective tools to directly assess reactivity and increase understanding of complex chemical-physical interaction mechanisms [28].

For monitoring photogenerated holes (h⁺), iodide (dosed as potassium iodide, KI) serves as an effective probe compound, oxidizing to iodine (I₂) which can be quantified spectrophotometrically [28]. The interaction between iodide and photogenerated holes is influenced by iodide adsorption on the TiO₂ surface, describable by a Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism whose parameters vary with TiO₂ concentration and irradiation time [28].

For monitoring hydroxyl radicals (•OH), terephthalic acid (TA) is commonly used as a probe compound, converting to 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid (2-HTA) which exhibits strong fluorescence that can be quantified [28]. This method has been successfully applied to study hydroxyl radical production in TiO₂ nanoparticle photocatalysis, providing insights into the factors influencing ROS generation [28].

The experimental setup typically involves photocatalyst suspensions in batch reactors continuously mixed on a magnetic stirrer and irradiated at specific wavelengths (e.g., 365 nm) [28]. Radiation intensity on the liquid surface is carefully monitored using radiometers, and the geometrical characteristics of the reaction vessel are controlled to ensure consistent illumination conditions [28]. Time-resolved measurements of reactive species production provide valuable kinetic data for modeling photocatalytic processes.

Characterization Techniques for Photocatalyst Analysis

Comprehensive characterization of photocatalysts is essential for understanding structure-activity relationships. X-ray diffraction (XRD) provides information about crystal structure, phase composition, and crystallite size [32]. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) reveals morphological features and surface characteristics, while Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) enables elemental analysis [32]. Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) determines optical properties and bandgap energies, which are crucial for understanding light absorption capabilities [32].

Additional characterization techniques include photoluminescence spectroscopy, which provides insights into charge carrier recombination behavior [35], and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), which reveals surface composition, elemental oxidation states, and oxygen vacancy concentrations [35]. Specific surface area and porosity measurements using methods like BET analysis help correlate textural properties with photocatalytic activity [31].

The fractal dimension of nanoparticle aggregates, determined by light scattering techniques, provides important information about aggregate structure that influences light penetration and reactive site accessibility [28]. These structural parameters significantly impact photocatalytic efficiency as dense aggregates can shield internal particles from illumination, reducing overall activity [28].

Visualization of Photocatalytic Mechanisms

Fundamental Photocatalytic Process Diagram

The DOT script below generates a visualization of the fundamental photocatalytic mechanism, showing the sequential processes from light absorption to reactive species generation and pollutant degradation:

Diagram Title: Photocatalytic Mechanism Overview

Experimental Workflow for ROS Measurement

The DOT script below illustrates the experimental methodology for measuring reactive oxygen species using molecular probes:

Diagram Title: ROS Measurement Methodology

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Photocatalytic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| P25 Aeroxide TiO₂ | Benchmark photocatalyst for comparative studies [28] | Reference material for evaluating new photocatalysts [28] |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Probe compound for detecting photogenerated holes [28] | Oxidizes to I₂ measurable by spectrophotometry [28] |

| Terephthalic Acid (TA) | Probe compound for detecting hydroxyl radicals [28] | Converts to 2-HTA measurable by fluorescence [28] |

| Metal Salt Precursors | Sources for doping (Fe, Ni, Cu, Mo, Pd) [35] | Enhancing visible light absorption and charge separation [35] |

| 2D MXene (Ti₃C₂) | Cocatalyst for improving charge separation [35] | Enhancing interfacial charge transfer in composites [35] |

| Methylene Blue | Model organic pollutant for degradation studies [32] [30] | Standard compound for evaluating photocatalytic activity [32] |

| Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) | Oxidant for advanced oxidation processes [35] | Enhancing degradation through sulfate radical generation [35] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and model pollutants is crucial for standardized evaluation of photocatalytic materials. Methylene blue serves as a common model pollutant due to its well-defined degradation pathway and ease of monitoring via spectrophotometry [32] [30]. Its degradation follows specific mechanisms involving reaction with hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anions, ultimately mineralizing to CO₂, H₂O, and inorganic ions [30]. Other organic dyes, antibiotics, and pharmaceuticals provide additional model pollutants for evaluating photocatalyst performance under different conditions [30].

The fundamental mechanisms of electron-hole pair generation and reactive oxygen species production in metal-doped metal oxide photocatalysts involve complex interrelated processes that determine overall photocatalytic efficiency. The comparative analysis presented in this review demonstrates that material engineering strategies including doping, heterojunction formation, and surface modification significantly enhance photocatalytic performance by improving charge separation, extending light absorption range, and increasing active surface areas. The experimental methodologies and characterization techniques discussed provide researchers with standardized approaches for evaluating new photocatalytic materials. As research in this field advances, the development of more efficient, stable, and visible-light-responsive photocatalysts will continue to drive innovations in environmental remediation and sustainable energy applications.

Synthesis and Deployment: Fabrication Techniques and Real-World Applications