Comparative Kinetic Studies of Transmetalation Reactions: Mechanisms, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transmetalation reaction kinetics, a pivotal yet complex step in metal-catalyzed cross-couplings essential for pharmaceutical and materials synthesis.

Comparative Kinetic Studies of Transmetalation Reactions: Mechanisms, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transmetalation reaction kinetics, a pivotal yet complex step in metal-catalyzed cross-couplings essential for pharmaceutical and materials synthesis. It explores foundational mechanisms like oxidative insertion and halogen-metal exchange, contrasting them with modern methodologies in continuous flow and biphasic systems. The review details advanced experimental and computational tools for kinetic profiling and troubleshooting common challenges such as halide inhibition and ligand effects. By comparing pathways across diverse catalytic systems—including Pd, Rh, and Au—this work establishes a framework for optimizing reaction rates and selectivity, offering critical insights for researchers developing efficient synthetic routes in drug discovery and development.

Unraveling Core Mechanisms: The Fundamental Pathways of Transmetalation

Transmetalation, also known as transmetallation, represents a fundamental elemental step in numerous catalytic cycles, serving as the critical transfer event where two metal centers exchange organic ligands. This process forms the cornerstone of modern cross-coupling chemistry, enabling the precise construction of carbon-carbon (C–C) and carbon-heteroatom (C–X) bonds that are essential to pharmaceutical development, materials science, and industrial chemistry. Within catalytic cycles, transmetalation typically occurs after oxidative addition and before reductive elimination, functioning as the key step that assembles the two coupling partners on the metal center. The efficiency and selectivity of transmetalation often govern the overall success of the catalytic transformation, influencing reaction rates, functional group tolerance, and product distribution. This guide provides a comparative analysis of transmetalation roles across diverse catalytic systems, highlighting mechanistic insights, kinetic influences, and experimental protocols crucial for research and development.

Mechanistic Foundations and Comparative Pathways

Transmetalation mechanisms exhibit significant diversity across catalytic systems, influenced by the nature of the metal catalyst, transferring reagent, ligand environment, and reaction conditions. Comparative studies reveal both common principles and system-specific peculiarities.

Classical Two-Electron Transmetalation in Pd-Catalyzed Systems

In conventional palladium-catalyzed cross-couplings such as Suzuki-Miyaura reactions, transmetalation typically proceeds through a coordinated four-center transition state, facilitating the transfer of an organic group from boron to palladium. This process involves coordination of the boronate complex to the palladium center followed by ligand exchange. Computational studies using density functional theory (DFT) have quantified the energy landscapes of these pathways, revealing how electron-rich phosphine ligands lower activation barriers by stabilizing the electron-deficient transition state [1]. The kinetics are generally first-order in both the palladium complex and the organometallic reagent, with rates highly sensitive to the coordination sphere around palladium.

Revolutionary Pd-to-Pd Transmetalation in Reductive Coupling

Recent research has uncovered a novel dimeric palladium mechanism in formate-mediated reductive cross-couplings. This system operates through a unique pathway where the active catalytic species is a dianionic Pd(I) dimer, [Pd₂I₄][NBu₄]₂ [2]. In this mechanism, Pd-to-Pd transmetalation enables rapid exchange of aryl groups between two palladium centers within iodide-bridged dimers. Experimental and computational studies confirm that hetero-diarylpalladium dimers (containing two different aryl groups) are more stable than homodimers and exhibit lower barriers to reductive elimination, thereby promoting cross-selectivity over homocoupling [2]. This represents a paradigm shift from classical transmetalation models.

Ligand-Gated Transmetalation in Copper-Catalyzed C–N Coupling

In Chan-Lam coupling of sulfenamides, transmetalation selectivity is governed by ligand control rather than inherent thermodynamic preferences. A tridentate pybox ligand overrides the competitive C–S bond formation by preventing the S,N-bis-chelation of sulfenamides to the copper center, thereby favoring N-binding and subsequent C–N bond formation [3]. Kinetic studies and EPR spectroscopy with ¹⁵N-labeled sulfenamides confirm that the interaction between the pybox ligand and the sulfenamide substrate controls the energy landscape of the transmetalation event, making N-arylation both kinetically and thermodynamically favorable [3].

Synchronized Transmetalation in Electrochemical Systems

Alternating current (AC) electrolysis introduces a temporal dimension to transmetalation control in nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings. Research demonstrates that AC frequency synchronizes with key steps in the Ni-catalyzed cycle to control product selectivity between C–N and C–C coupling [4]. Optimal C–N selectivity arises from minimizing the exposure of a key Ni(II) intermediate to reducing conditions that would otherwise promote off-cycle Ni(I) species and undesired C–C homocoupling. The timing of intermediate formation is highly dependent on the electrophilic coupling partner, enabling frequency-based control over the transmetalation step [4].

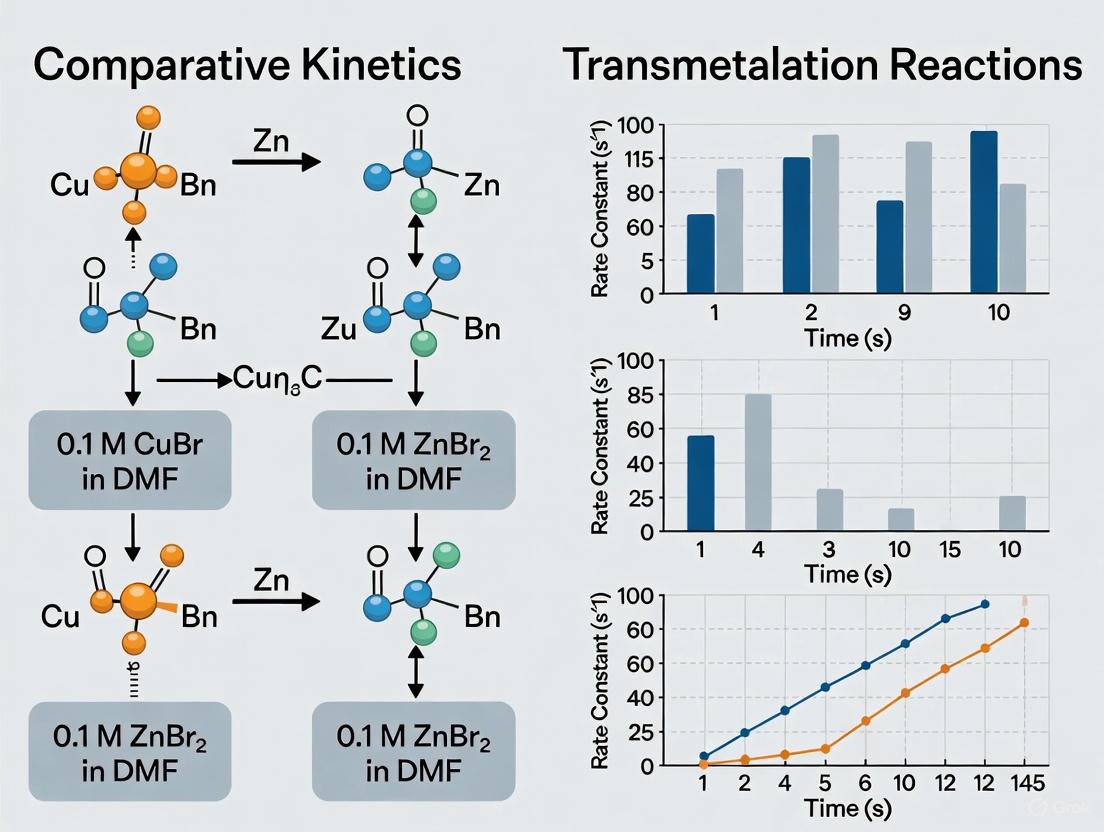

The diagram below illustrates the core positioning of transmetalation within a generic catalytic cycle and contrasts classical and contemporary mechanisms:

Comparative Kinetic Data and Experimental Metrics

The kinetics of transmetalation processes vary considerably across different catalytic systems, influenced by metal identity, ligand architecture, and transferring reagents. The following table summarizes key quantitative parameters from recent studies:

Table 1: Comparative Kinetic Parameters for Transmetalation Processes

| Catalytic System | Rate-Determining Step | Activation Energy Barrier (kcal/mol) | Turnover Frequency (h⁻¹) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd/Phosphine (Suzuki) [1] | Transmetalation | 18-25 | Varies | Ligand electron density, Oxidative addition rate |

| Pd/Pybox (Chan-Lam) [3] | Transmetalation | Not specified | Not specified | Tridentate ligand blockade, N-binding vs. S,N-bis-chelation |

| Ni/Bipyridine (AC Electrolysis) [4] | Oxidative addition → Transmetalation timing | Not specified | Not specified | AC frequency (0.2 Hz optimal), Minimized Ni(II) exposure |

| Ni-Metalated COF [5] | Not specified | Reduced via modulation | 442 (flow protocol) | Electron transfer distance, Metal center electron density |

| Pd(I) Dimeric System [2] | Reductive elimination | Not specified | Not specified | Hetero-diarylpalladium dimer stability |

Table 2: Transmetalation Selectivity Control Strategies

| Control Strategy | Mechanistic Basis | System Impact | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Design [3] | Prevents undesired coordination modes | Switches selectivity from C-S to C-N bond formation | EPR isotope studies, Computational mechanistic analysis |

| AC Frequency Modulation [4] | Synchronizes reducing power with intermediate formation | Suppresses C-C homocoupling in favor of C-N coupling | CV analysis, Frequency-dependent yield mapping (0.2 Hz optimal) |

| Dimeric Intermediate Control [2] | Favors hetero-diarylpalladium dimers over homodimers | Enhances cross-selectivity over homo-coupling | ESI-HRMS detection of [Pd₂I₄][NBu₄]₂, DFT calculations |

| Metal Center Electron Density Tuning [5] | Optimizes electron acceptance capability | Lowers activation barrier for transmetalation | Life cycle assessment, Computational calculations |

Essential Experimental Protocols

This protocol demonstrates how ligand selection can direct transmetalation selectivity toward C–N bond formation.

- Reaction Setup: In a microwave vial, combine sulfenamide (1.0 equiv), arylboronic acid (2.0 equiv), Cu(TFA)₂•H₂O (10 mol %), pybox ligand L3 (20 mol %), and Cy₂NMe (1.5 equiv) in MeCN (0.3 M).

- Reaction Conditions: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 24 hours under an O₂ atmosphere.

- Key Observations: The tridentate pybox ligand governs chemoselectivity by preventing S,N-bis-chelation of sulfenamides to the copper center, favoring N-binding instead.

- Analysis: Reaction monitoring by UV-Vis spectra and EPR technique confirms the Cu(II)-derived resting state of the catalyst. EPR isotope response using ¹⁵N-labeled sulfenamide verifies the key intermediate.

- Scale: Reaction performed on 0.1-0.5 mmol scale with isolated yields typically ranging from 54-87%.

This protocol illustrates the novel Pd-to-Pd transmetalation mechanism in a reductive coupling system.

- Catalyst System: Use [Pd(I)(PtBu₃)]₂ (2.5 mol%) as precatalyst with Bu₄NI (20 mol%) in dioxane:H₂O (9:1, 0.2 M) at 100°C.

- Reductant: Employ formate as the non-metallic reductant.

- Key Observations: The neutral dimeric Pd(I) precatalyst is converted to the active dianionic species [Pd₂I₄][NBu₄]₂, from which aryl halide oxidative addition is more facile.

- Mechanistic Verification: ESI-HRMS detection of [Pd₂I₄][NBu₄]₂ confirms the active species. Rapid, reversible Pd-to-Pd transmetalation delivers iodide-bridged diarylpalladium dimers, with hetero-dimers being more stable and having lower barriers to reductive elimination.

- Functional Group Tolerance: The system displays orthogonality with Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, tolerating pinacol boronates and anilines.

This protocol demonstrates how electrochemical parameters can control transmetalation timing and selectivity.

- Electrochemical System: Employ Ni(II)(di-Mebpy)Br₂ as catalyst in LiNTf₂ electrolyte (redox-inert) with AC electrolysis.

- Optimized Parameters: Apply AC frequency of 0.2 Hz with amplitude of 3.0 V for optimal C–N selectivity.

- Key Observations: Optimal C–N selectivity arises from minimizing the exposure of the key intermediate Ni(II)(Ar)Br to reducing conditions that promote off-cycle Ni(I) species and undesired C–C homocoupling.

- Analysis Method: Use cyclic voltammetry (CV) to predict optimal AC frequency across diverse aryl bromides, eliminating trial-and-error optimization. The formation rate of the key intermediate is governed by oxidative addition but largely independent of the amine coupling partner.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Transmetalation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Transmetalation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligands | Tridentate pybox (L3) [3] | Blocks undesired coordination modes, directs selectivity | Chan-Lam coupling, C–N bond formation |

| Precatalysts | [Pd(I)(PtBu₃)]₂ [2] | Forms active dianionic Pd(I) dimer species | Reductive cross-coupling, Pd-to-Pd transmetalation |

| Additives | Bu₄NI [2] | Stabilizes Pd(I) dimers, facilitates oxidative addition | Formate-mediated coupling |

| Electrocatalysis Components | Ni(II)(di-Mebpy)Br₂, LiNTf₂ [4] | Enables AC frequency control over intermediate timing | Electrochemical C–N coupling |

| Analytical Tools | EPR with ¹⁵N-labeling [3] | Verifies key intermediates and bonding modes | Mechanistic studies |

| Computational Methods | DFT/MM calculations [1] | Maps potential energy surfaces, identifies transition states | Mechanistic rationalization |

Transmetalation has evolved from a simple ligand transfer step to a sophisticated process that can be strategically manipulated through ligand design, catalyst architecture, and even external modulation such as electrochemical synchronization. The comparative data presented herein reveals that contemporary transmetalation strategies increasingly focus on controlling the coordination environment and timing of the transfer event rather than simply optimizing traditional parameters. The emergence of innovative mechanisms such as Pd-to-Pd transmetalation and frequency-synchronized transfer highlights the ongoing expansion of fundamental cross-coupling paradigms. For researchers designing catalytic systems for pharmaceutical development or complex molecule synthesis, these advances offer powerful strategies for overcoming traditional selectivity challenges and accessing novel chemical space. Future directions will likely include further integration of electrochemical control, development of heterogeneous systems with molecular precision, and increased use of computational prediction to guide transmetalation optimization.

Transmetalation is a fundamental elemental step in metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, serving as the critical transfer event where an organic group is exchanged between two metal centers. This process directly impacts the efficiency and applicability of synthetic methodologies used extensively in pharmaceutical development and materials science. Within this landscape, two principal mechanistic pathways—oxidative insertion and bridged intermediate formation—govern the transmetalation event across different catalytic systems. Framed within a broader thesis on comparative kinetic studies of transmetalation reactions, this guide provides an objective performance analysis of these pathways, supported by quantitative kinetic data and detailed experimental protocols. Understanding the distinct operational frameworks, kinetic parameters, and experimental support for each pathway is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select and optimize catalytic systems for complex synthetic challenges.

The oxidative insertion and bridged intermediate pathways represent distinct mechanistic paradigms for transmetalation, differentiated by the oxidation state changes of the metal center and the structure of the key transition state.

Oxidative Insertion Pathway: This pathway is characterized by a formal increase in the oxidation state of the metal center during the transfer of the organic group. The mechanism typically involves a nucleophilic attack by an organometallic reagent on a transition metal complex, leading to an intermediate with a higher oxidation state before reductive elimination yields the final product. This pathway is often discussed in the context of reactions involving Cu(I) complexes [6].

Bridged Intermediate Pathway: This mechanism proceeds through the formation of a ternary complex featuring a bridging atom (often oxygen) that connects the main group metal (e.g., boron) and the transition metal (e.g., palladium). Key intermediates in the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction, for instance, contain a definitive Pd–O–B linkage, the "missing link" confirmed through low-temperature NMR spectroscopy [7]. Transmetalation in this pathway occurs within this coordinated structure without a formal oxidative insertion step.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each pathway.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Transmetalation Pathways

| Feature | Oxidative Insertion Pathway | Bridged Intermediate Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Key Mechanistic Step | Nucleophilic attack & oxidation state change [6] | Formation of a bridging atom-linked complex (e.g., Pd–O–B) [7] |

| Representative System | Copper-catalyzed cross-coupling [6] | Palladium-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling [7] |

| Key Intermediate | High-valent metal species (e.g., Cu(III)) [6] | Tri- or tetra-coordinate bridged species (e.g., 6-B-3, 8-B-4) [7] |

| Oxidation State Change | Formal increase during the process [6] | Not a defining feature of the mechanism [7] |

Quantitative Kinetic Comparison

Kinetic analysis provides critical insights into the efficiency and rate-determining nature of these transmetalation pathways. The following table compiles quantitative kinetic data from experimental studies.

Table 2: Comparative Kinetic Data for Transmetalation Pathways

| Catalytic System | Transmetalation Step | Rate Constant (k) | Activation Enthalpy (ΔH‡) | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel / Arylzinc Reagents [8] | Transmetalation of ArZnCl with Ar'Ni(II)R | 0.04 - 0.31 M⁻¹ s⁻¹ | 14.6 kcal/mol (for PhZnCl) | Not specified |

| Copper / Bipyridyl Complex [6] | Oxidative Addition of Rf-I to [Cu(bipy)(C₆F₅)] | - | 21.3 kcal/mol (calc.) | THF, DFT calculations (B3LYP-D3) |

The data highlights that transmetalation can be the rate-limiting step in a catalytic cycle, as definitively shown in nickel-catalyzed couplings [8]. The measured rate constants for different arylzinc reagents provide a quantitative basis for evaluating substituent effects on reactivity. In the copper system, the barrier for the oxidative addition step, which is part of the oxidative insertion pathway, was computationally determined to be 21.3 kcal/mol [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol A: Studying Bridged Intermediates via RI-NMR

This methodology details the generation and observation of elusive Pd–O–B bridged intermediates [7].

- Objective: To generate, observe, and characterize pre-transmetalation intermediates containing Pd–O–B linkages in the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction.

- Key Techniques: Rapid Injection NMR Spectroscopy (RI-NMR) at low temperatures; Kinetic analysis via reaction monitoring; Computational analysis (DFT calculations).

- Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Synthesize and isolate the oxidative addition complex, e.g., (Ph₃P)₂Pd(Ph)Br.

- Intermediate Generation: Rapidly mix the palladium complex with the organoboron reagent (e.g., a boronic acid or a pre-formed boronate salt) at low temperatures (-80 to -60 °C) in a suitable anhydrous solvent like THF.

- Rapid Injection NMR: Use a specialized RI-NMR probe to inject the cold reaction mixture into an NMR tube pre-cooled in the NMR spectrometer. Acquire NMR spectra immediately and at timed intervals.

- Species Identification: Identify the intermediates (e.g., the tri-coordinate 6-B-3 boronic acid complex and the tetra-coordinate 8-B-4 boronate complex) by characteristic chemical shifts in the ¹¹B and ³¹P NMR spectra.

- Kinetic Competence: Demonstrate that the observed intermediates proceed to form the cross-coupling product at a rate consistent with the catalytic reaction.

- Critical Notes: The success of this protocol hinges on the speed of mixing and transfer to minimize decomposition of the highly reactive intermediates. The use of low temperatures is essential to stabilize the intermediates for observation.

Protocol B: Kinetic Analysis of an Oxidative Insertion Pathway

This protocol outlines a combined experimental and computational approach to probe a copper-based system where oxidative insertion is operative [6].

- Objective: To determine the kinetic parameters and mechanism of homocoupling product formation in a copper-catalyzed system, revealing a transmetalation step involving Cu(I) and Cu(III) species.

- Key Techniques: Kinetic monitoring via NMR or other spectroscopic methods; Hammett analysis; Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Monitoring: Conduct the reaction between [Cu(bipy)(C₆F₅)] and a specialized aryl iodide (e.g., 3,5-dichloro-2,4,6-trifluorophenyl iodide) in THF.

- Product Quantification: Use NMR spectroscopy to track the formation of both cross-coupling (Rf–Pf) and homocoupling (Pf–Pf and Rf–Rf) products over time.

- Concentration Dependence: Perform a series of reactions with varying initial concentrations of the Cu(I) complex to assess its order in the rate law.

- Data Fitting: Fit the concentration-time data for all products to different kinetic models (e.g., Model I: double oxidative addition vs. Model II: transmetalation from a Cu(III) intermediate).

- Computational Validation: Use DFT calculations (e.g., B3LYP-D3 functional with an SMD/THF solvation model) to map the Gibbs energy profile, locate transition states, and calculate energy barriers for oxidative addition, reductive elimination, and the proposed transmetalation step between Cu(I) and Cu(III).

- Critical Notes: The choice of the fluorinated aryl iodide is crucial, as it stabilizes the Cu–C bond and allows the transient Cu(III) intermediate to be intercepted. The observation that homocoupling product formation is dependent on the concentration of the Cu(I) complex is key evidence for the bimolecular transmetalation event.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and their functions for studying transmetalation mechanisms.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Transmetalation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Palladium Phosphine Complexes (e.g., (Ph₃P)₂Pd(Ph)Br) [7] | Pre-formed oxidative addition complex to study subsequent transmetalation steps. |

| Organoboron Reagents (Boronic acids & boronate salts) [7] | React with Pd complexes to form Pd–O–B bridged intermediates. |

| Copper(I) Complexes (e.g., [Cu(bipy)(C₆F₅)]) [6] | Catalyst and nucleophile in oxidative insertion pathways. |

| Specialized Aryl Iodides (e.g., Rf–I) [6] | Substrates designed to stabilize high-valent metal intermediates for mechanistic study. |

| Deuterated Solvents (THF-d₈, Acetone-d₆) | Medium for NMR-based kinetic studies and intermediate observation. |

| Phosphine Ligands (e.g., Trialkylphosphines, Triarylphosphines) | Modify steric and electronic properties of metal centers to influence mechanism and rates [7]. |

The comparative analysis of transmetalation pathways reveals a clear mechanistic dichotomy. The bridged intermediate pathway, exemplified by the Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura reaction, is characterized by well-defined, observable complexes whose stability and reactivity are highly dependent on ligand environment. In contrast, the oxidative insertion pathway, observed in certain copper systems, involves high-energy intermediates and bimolecular interactions that can divert selectivity toward homocoupling products. Kinetic data unequivocally establishes that transmetalation can be the rate-limiting step in these catalytic cycles, with measured activation parameters providing a quantitative framework for reaction optimization. For researchers in drug development, this comparative insight is invaluable: the bridged pathway offers greater control for predictable cross-coupling, while the oxidative insertion pathway requires careful management of catalyst loading and concentration to suppress homocoupling side reactions. The choice between these inherent pathways, governed by the metal and ligands selected, is therefore fundamental to the design of efficient and scalable synthetic processes.

The study of halogen-metal exchange kinetics represents a critical frontier in modern organometallic chemistry, particularly for the synthesis of complex pharmaceutical intermediates and functionalized molecules. This transformation, wherein a halogen atom on an organic molecule is replaced by a metal, generates highly reactive organometallic species that serve as pivotal intermediates in constructing carbon-carbon bonds. Traditional batch processing of these reactions is often hampered by poor heat transfer and difficulties in controlling the exothermic exchange process, leading to decomposition and side-product formation. The integration of these reactions into continuous flow systems has unveiled a new realm of kinetic possibilities, enabling the generation, study, and utilization of millisecond-lived intermediates that were previously inaccessible.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of halogen-metal exchange methodologies, focusing specifically on the kinetic advantages afforded by continuous flow technology. By examining direct experimental data and protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the practical knowledge to select and implement optimal exchange strategies for their specific synthetic challenges, particularly within the broader context of comparative transmetalation kinetics.

Comparative Kinetic Platforms: Batch vs. Flow Chemistry

The fundamental difference between batch and flow reactors for halogen-metal exchange lies in the unprecedented control over reaction parameters offered by flow systems. Table 1 summarizes the key kinetic and operational advantages of flow chemistry that enable the study and utilization of millisecond intermediates.

Table 1: Kinetic Comparison of Halogen-Metal Exchange in Batch vs. Flow Reactors

| Parameter | Batch Reactor | Continuous Flow Reactor |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer | Limited, leading to hot spots and decomposition | Superior due to high surface-to-volume ratio [9] |

| Mixing Efficiency | Slow, diffusion-dependent | Highly efficient, reduces local concentration gradients [9] [10] |

| Reaction Time Control | Seconds to hours (limited by mixing) | Milliseconds to seconds (precise via residence time) [9] |

| Intermediate Stability | Decomposition common for unstable species | Cryogen-free generation and immediate trapping of sensitive intermediates [9] |

| Reaction Scalability | Nonlinear, requires re-optimization | Linear, via numbering-up or prolonged operation [9] [11] |

| Kinetic Data Quality | Lower resolution for fast reactions | High-resolution, enables study of ultrafast kinetics [9] |

A critical insight from recent studies is that achieving optimal results in flow is not merely about maximizing mixing efficiency. The flow regime—determined by the mixer design and flow rate—is paramount. Variation in these parameters can alter product distribution and stereoselectivity, as molecules assemble into transient supramolecular structures (supramers) whose reactivity depends on how reagents are presented to one another [10]. Therefore, the goal is not always the fastest possible mixing, but rather the correct mixing for the desired reaction pathway.

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Studies in Flow

Protocol 1: Ultrafast Halogen-Lithium Exchange and Trapping

This protocol, pioneered by Yoshida, demonstrates the generation and trapping of organolithium intermediates on a millisecond timescale, a feat impractical in batch reactors [9].

- Objective: To perform a Br/Li exchange on an aryl bromide and trap the resulting aryllithium intermediate with an electrophile.

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Substrate Solution: 0.1-0.3 M solution of the aryl bromide in a suitable solvent (e.g., THF).

- Exchange Reagent: n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi, 1.1-1.5 equiv) in hexanes.

- Electrophile Solution: Aldehyde, ketone, or other electrophile (1.2-2.0 equiv) in the same solvent.

- Flow Setup and Procedure:

- Reactors: A two-stage continuous flow system is assembled using micromixers (e.g., T-shaped or more advanced designs) connected to micro-tubular reactors.

- Stage 1 - Exchange: The substrate and n-BuLi solutions are pumped into the first mixer. The residence time in the subsequent tube reactor is controlled to be 10-100 milliseconds by adjusting the flow rate and reactor volume. This short, precise time is sufficient for the exchange but minimizes decomposition of the new organolithium species.

- Stage 2 - Trapping: The outflow from the first reactor is immediately mixed with the electrophile solution in a second mixer. The combined stream then passes through a second tubular reactor with a residence time of 1-30 seconds to complete the trapping reaction.

- Quenching: The reaction mixture is collected into a quenching solution (e.g., water or a pH buffer).

- Kinetic Insight: The superior heat and mass transfer of the microreactor allows this highly exothermic exchange to be performed at higher temperatures than in batch, while the exact control over residence time prevents the decomposition of the sensitive aryllithium intermediate, enabling high-yield reactions [9].

Protocol 2: Bromine-Sodium Exchange in Continuous Flow

This protocol addresses the historical challenge of using organosodium reagents, which are often insoluble and difficult to handle, by employing a continuous flow setup [12].

- Objective: To achieve a Br/Na exchange on an (hetero)aryl bromide using a hexane-soluble sodium reagent.

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Substrate Solution: 0.1 M solution of the aryl bromide in toluene.

- Exchange Reagent: 2-Ethylhexylsodium (approx. 1.2 equiv) in hexanes. This novel reagent overcomes the solubility issues of traditional sodium organometallics.

- Electrophile Solution: Trimethylchlorosilane (TMSCI, 2.0 equiv) or other electrophile in toluene.

- Flow Setup and Procedure:

- The substrate and 2-ethylhexylsodium solutions are pumped through a commercially available flow reactor (e.g., a chip-based mixer or a tubular reactor).

- The residence time for the exchange is set to a few seconds.

- The resulting aryl sodium species is subsequently mixed with the electrophile solution in a second mixing unit.

- The final mixture is quenched in-line or collected for workup.

- Kinetic Insight: The use of toluene as a solvent and the continuous flow environment facilitate this exchange with enhanced efficiency and broader functional group tolerance compared to some traditional lithium-based exchanges, providing a complementary tool for synthesis [12].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and reactor configuration for a generic two-step halogen-metal exchange and trapping sequence in a continuous flow system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of kinetic studies in halogen-metal exchange relies on a set of specialized reagents and equipment. Table 2 details the key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Halogen-Metal Exchange Kinetics

| Tool/Reagent | Function & Specific Role | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi) | Classic Br/Li and I/Li exchange reagent. | High reactivity; requires precise stoichiometric control and cryogenic conditions in batch [9]. |

| 2-Ethylhexylsodium | Novel reagent for Br/Na exchange. | Hexane-soluble, overcoming a major limitation of organosodium chemistry [12]. |

| iPrMgBr·LiCl | Turbo-Grignard reagent for halogen-magnesium exchange. | Fast exchange in toluene; excellent functional group tolerance [12]. |

| T-Shaped Micromixer | Fundamental device for initial reagent mixing. | Efficiency highly dependent on flow rate; can exhibit engulfment regime at higher flows for better mixing [10]. |

| Micro-Tubular Reactor | Provides controlled residence time. | Enables precise reaction times from milliseconds to minutes [9]. |

| Syringe Pumps | Delivers reagents at precise, constant flow rates. | Critical for maintaining stable residence times and reproducible kinetics. |

| In-line Spectrometer | Real-time reaction monitoring (PAT). | Enables kinetic data acquisition and immediate feedback on intermediate formation [11]. |

The migration of halogen-metal exchange reactions into continuous flow systems has fundamentally transformed our ability to study and harness their kinetics. The protocols and data presented herein confirm that flow chemistry is not merely an alternative to batch processing, but a superior platform for investigating and executing these sensitive transformations. The precise control over temperature, mixing, and residence time allows for the reproducible generation of millisecond-lived intermediates, providing cleaner reaction profiles, higher yields, and enhanced safety.

The future of this field lies in the deeper integration of process analytical technology (PAT), automation, and advanced reactor designs [11]. Real-time monitoring with in-line IR and NMR spectrometers will generate richer kinetic data, enabling closed-loop optimization of reaction conditions. Furthermore, the combination of halogen-metal exchange with other catalytic modalities, such as photoredox or electrocatalysis in telescoped flow sequences, promises to unlock novel reaction pathways and streamline the synthesis of complex molecules [11]. As these technologies mature, the kinetic principles governing halogen-metal exchange will continue to serve as a critical foundation for the broader field of comparative transmetalation research.

Directed metalation has emerged as a powerful strategy for achieving precise regiocontrol in C–H functionalization, a cornerstone of modern synthetic chemistry. This approach utilizes coordinating functional groups, known as directed metalation groups (DMGs), to guide metal catalysts to specific C–H bonds, enabling their selective activation and subsequent functionalization [13]. For researchers in drug development, this methodology offers a streamlined pathway to complex molecules, reducing the need for pre-functionalized starting materials and minimizing synthetic steps.

A significant historical limitation of these reactions, particularly those employing highly reactive organolithium bases, has been the requirement for cryogenic conditions (e.g., -78 °C) to maintain the stability of reactive intermediates and suppress unwanted side reactions [14]. However, recent technological and methodological advances are systematically overcoming this barrier. The integration of continuous flow chemistry and the development of novel main group metal bases now enable numerous metalation reactions to proceed at ambient temperatures, enhancing both the safety and scalability of these transformations [9] [15]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these strategies, focusing on their performance in achieving regioselectivity and operating under practical temperature conditions.

Comparative Analysis of Directed Metalation Approaches

The field of directed metalation encompasses a variety of approaches, which can be evaluated based on their inherent regioselectivity, operational temperature range, and compatibility with other reagents. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of prominent strategies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key Directed Metalation Strategies

| Metalation Strategy | Typical Bases/Reagents | Inherent Regioselectivity (DMG Power) | Typical Operational Temperature | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aryl O-Carbamate (ArOAm) DoM [14] | Alkyllithiums (e.g., n-BuLi) | Very High (especially Ar-OCONEt₂) | Traditionally -78 °C (Cryogenic) | Strongest of the O-based DMGs; effective in AoF rearrangement and iterative sequences [14]. | Hydrolysis resistance; traditionally requires cryogenics [14]. |

| Continuous Flow Metalation [9] | RLi, LiNR₂, TMPZnCl·LiCl | Enhanced by control & kinetics | 0 °C to 25 °C (Ambient/Cryogen-free) | Superior heat/mass transfer; safe handling of pyrophoric reagents; scalable [9]. | Requires specialized flow reactor equipment. |

| s-Block & Main Group Metal Bases [15] | TMPMgCl·LiCl, TMP₂Zn·2MgCl₂·2LiCl | High, guided by substrate & base design | 25 °C (Ambient) | Excellent functional group tolerance; generates robust intermediates; room temperature operation [15]. | Constitution of active intermediates can be complex and uncertain [15]. |

| 8-Aminoquinoline DG Halogenation [16] | Fe catalysts, Cu mediators, Electrochemistry | High, via bidentate chelation | 25 °C to 100 °C (Ambient/Mild Heating) | Enables remote C–H functionalization; compatible with "green" solvents (e.g., water) and oxidants (e.g., air) [16]. | Requires installation and potential removal of the directing group. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To translate these comparative profiles into practical action, this section outlines general experimental workflows for the two most transformative strategies: traditional batch DoM and modern continuous flow metalation.

Traditional Workflow: DirectedorthoMetalation (DoM) in Batch

The classical DoM process, as exemplified by the use of the ArOAm DMG, follows a well-established protocol [14].

- Step 1 – Substrate Preparation: The substrate molecule is functionalized with a powerful DMG, such as the diethylcarbamate group (Ar-OCONEt₂).

- Step 2 – Cryogenic Metalation: The substrate is dissolved in an anhydrous aprotic solvent (e.g., THF). The solution is cooled to -78 °C under an inert atmosphere, and a strong base (e.g., n-BuLi) is added dropwise. The mixture is stirred at this cryogenic temperature for a specified time to generate the aryllithium intermediate.

- Step 3 – Electrophilic Quench: An electrophile (E⁺) is introduced to the reaction vessel. The mixture is typically allowed to warm slowly to room temperature to ensure complete reaction.

- Step 4 – Work-up and DMG Manipulation: The reaction is quenched, and the product is isolated. The robust ArOAm DMG can then be hydrolyzed to a phenol or engaged in cross-coupling reactions [14].

Advanced Workflow: Continuous Flow Metalation

The continuous flow protocol leverages reactor engineering to overcome the limitations of the batch process [9].

- Step 1 – Reagent Preparation: Solutions of the substrate and the organometallic base are prepared in suitable solvents.

- Step 2 – Inline Mixing and Reaction: The substrate and base streams are pumped into a continuous flow microreactor. The high surface-to-volume ratio allows for instantaneous mixing and highly efficient heat exchange, controlling the exothermic metalation step even at higher temperatures.

- Step 3 – Inline Quenching: The resulting stream containing the metalated intermediate is immediately mixed with a third stream containing the electrophile in a second reactor module. The extremely short residence times (milliseconds to seconds) prevent the decomposition of unstable intermediates.

- Step 4 – Product Collection: The reacted mixture exits the flow reactor and is collected for standard work-up and purification. This telescoped process avoids the isolation of sensitive organometallic species [9].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the challenges of traditional metalation and the solutions provided by modern approaches, highlighting the critical shift away from cryogenic dependency.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of advanced metalation strategies requires a toolkit of specialized reagents. The following table details key compounds and their specific functions in enabling high-regioselectivity reactions under mild conditions.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Modern Metalation Protocols

| Reagent / Base | Primary Function | Key Feature / Rationale | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMPZnCl·LiCl (Turbo-Hauser Base) [15] | Chemoselective C–H zincation of arenes and heteroarenes. | Moderate reactivity allows for room temperature metalation with high functional group tolerance (e.g., nitro, ester, nitrile groups) [15]. | Direct zincation of 2,4-difluoronitrobenzene at 25 °C, followed by Negishi cross-coupling [15]. |

| TMPMgCl·LiCl (Knochel's Base) [15] | Regioselective C–H magnesiation of fluoroarenes. | Operates in toluene at room temperature; generates bis-aryl magnesium intermediates compatible with various electrophiles [15]. | Metalation of fluoropyridines and perfluoroarenes at 25 °C [15]. |

| 8-Aminoquinoline [16] | Bidentate directing group for remote C–H functionalization. | Forms stable 5-membered palladacycles or other metallacycles, enabling high regiocontrol for C–X (X = Halogen) bond formation [16]. | Iron-catalyzed C5-bromination of quinolines in water at room temperature [16]. |

| Diethylcarbamoyl Group (Ar-OCONEt₂) [14] | Powerful O-based DMG for Directed ortho Metalation (DoM). | Ranked as one of the strongest O-DMGs; provides excellent ortho-directing ability in anisole derivatives [14]. | Serendipitous discovery of ArOAm-directed ortho-lithiation and anionic ortho-Fries (AoF) rearrangement [14]. |

| Flow Reactor Systems [9] | Enabling technology for safe and controlled exothermic reactions. | Provides precise control over residence time and temperature, allowing the use of RLi bases at significantly higher temperatures than in batch [9]. | Lithiation–electrophile trapping sequences for pharmaceutical intermediates (e.g., fenofibrate, montelukast) without cryogenics [9]. |

The strategic evolution of directed metalation is marked by a clear transition from cryogenic-dependent batch processes to more practical, sustainable, and scalable methodologies. The objective data confirms that while traditional DMGs like the aryl O-carbamate offer unmatched regioselectivity, their full potential is now being unlocked by modern engineering and reagent design.

The comparative analysis underscores that continuous flow chemistry and advanced main group metal bases are not merely incremental improvements but are paradigm-shifting solutions. They directly address the core challenges of thermal control and intermediate stability, thereby circumventing the need for cryogenics. For researchers engaged in kinetic studies of transmetalation or the development of active pharmaceutical ingredients, the adoption of these tools translates to enhanced safety, reduced operational complexity, and more viable paths from discovery to large-scale synthesis. The future of directed metalation lies in the continued integration of these strategies, further expanding the accessible chemical space for drug development.

Organometallic reagents, characterized by carbon-metal bonds, constitute a cornerstone of modern synthetic organic chemistry, enabling the efficient construction of complex molecular architectures. Among them, organolithium, organomagnesium (Grignard reagents), and organozinc compounds are fundamental tools for practicing chemists. The unique reactivity of each reagent class stems from the nature of the carbon-metal bond, which exhibits varying degrees of ionic character that directly influence nucleophilicity, basicity, and functional group compatibility. Recent advances have not only refined our understanding of their traditional applications but have also unlocked new reactivity paradigms through continuous flow technologies, transmetalation strategies, and the development of stabilized reagents. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these essential organometallic reagents, focusing on their performance characteristics, kinetic behavior in transmetalation processes, and practical applications in complex synthesis, particularly within pharmaceutical and materials science research. The integration of these reagents into modern continuous flow systems has further revolutionized their utility by enhancing safety, scalability, and reaction control for traditionally challenging transformations [9].

Comparative Analysis of Key Organometallic Reagents

The table below provides a detailed comparison of the three key organometallic reagent classes, highlighting their distinct properties, reactivity, and suitability for different synthetic applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Organolithium, Organomagnesium (Grignard), and Organozinc Reagents

| Characteristic | Organolithium Reagents | Organomagnesium Reagents (Grignard) | Organozinc Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-M Bond Ionic Character | High (∼30%) [17] | Moderate (∼20%) [17] | Low (Covalent) [18] [17] |

| General Reactivity | Very high (strong base/nucleophile) | High (good nucleophile) | Moderate (mild nucleophile) |

| Functional Group Tolerance | Low; incompatible with many protic, electrophilic groups | Moderate; tolerates some functions better than Li, but still reactive | High; tolerates esters, ketones, nitriles, nitro groups [18] |

| Key Preparation Methods | Direct halogen-lithium exchange, direct metalation [19] [17] | Direct oxidative insertion of Mg(0) (Grignard formation), Br/Mg-exchange ("turbo-Grignard") [19] [20] | Direct Zn(0) insertion (aided by LiCl), transmetalation from Mg or Li, direct zincation [19] [18] |

| Typical Stability & Handling | Air- and moisture-sensitive; often pyrophoric; requires cryogenic temperatures and inert atmosphere | Air- and moisture-sensitive; requires inert atmosphere; generally less pyrophoric than RLi | Less pyrophoric than RLi or RMgX; can be stored using standard Schlenk techniques [18] |

| Primary Synthetic Uses | Directed metalation, nucleophilic addition, halogen-lithium exchange | Broadly useful nucleophile for additions to carbonyls, cross-couplings | Excellent for Negishi cross-coupling, transmetalation agent, Reformatsky-type reactions [19] [18] |

Experimental Insights and Kinetic Behavior in Transmetalation

Transmetalation, the transfer of an organic group from one metal to another, is a critical elementary step in numerous catalytic cycles and synthetic sequences. The kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of these reactions are highly dependent on the specific metal pairing and the reaction environment.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Transmetalation

Detailed mechanistic studies of transmetalation processes often employ a combination of techniques:

- In-situ Spectroscopy: Low-temperature NMR spectroscopy can be used to monitor the formation and consumption of organometallic species during transmetalation.

- Stoichiometric Studies: Combining pre-formed organometallic reagents with transition metal salts (e.g., Pd, Cu, Fe, Co) in a controlled, stepwise manner allows for the isolation and characterization of key intermediates [21].

- Kinetic Profiling: Monitoring reaction rates under different concentrations and temperatures provides activation parameters and reveals the order of the transmetalation step.

- Fluorescence Microscopy: For heterogeneous reactions, such as the formation of organozinc reagents on zinc metal surfaces, fluorescence microscopy has been used to visualize and quantify the formation and solubilization of surface intermediates, revealing that activators like LiCl operate by accelerating solubilization rather than the oxidative addition step itself [22].

Key Findings in Transmetalation Kinetics and Selectivity

- Zinc Transmetalation: Organozinc reagents are premier partners in transmetalation. The carbon-zinc bond's covalent nature and low polarity make it relatively stable yet able to readily transfer organic groups to transition metals like palladium (in Negishi coupling) or copper. The kinetics of this transfer are favorable, often occurring rapidly at or below room temperature. A notable protocol involves the in-situ trapping of organolithium intermediates with ZnCl₂ or other zinc salts in a continuous flow reactor, minimizing side reactions and enabling the preparation of polyfunctional organozincs [9] [19].

- Magnesium to Zinc Transmetalation: This is a common method for preparing functionalized organozinc reagents. For instance, a "turbo-Grignard" reagent (iPrMgCl·LiCl) can undergo a fast halogen-magnesium exchange with an organic halide. The resulting aryl magnesium species is then transmetalated to zinc by the addition of ZnCl₂, providing an organozinc reagent suitable for cross-coupling [19].

- Iron-Catalyzed Coupling with Organosodium Reagents: Recent groundbreaking work has demonstrated the use of highly ionic organosodium compounds in iron-catalyzed homocoupling and cross-coupling. A key finding is that bidentate additives are crucial for controlling reactivity, likely by coordinating to both the sodium and iron centers, thus taming the inherently high and unselective reactivity of the C-Na bond [21]. This highlights how additive control can override innate kinetic reactivity patterns.

Advanced Applications and Workflows in Modern Synthesis

The Power of Continuous Flow Reactors

The integration of organometallic chemistry into continuous flow systems represents a major advancement, particularly for handling highly exothermic reactions and unstable intermediates [9]. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for conducting organometallic reactions in a continuous flow setup.

Diagram 1: Continuous Flow Organometallic Workflow

This setup provides several key advantages for handling organometallic reagents:

- Superior Thermal Control: The high surface-to-volume ratio of microreactors allows for efficient heat dissipation, making highly exothermic reactions like halogen-lithium exchange safer and more controllable [9].

- Precise Residence Time: Reactions can be quenched after very short, precisely defined times (milliseconds to seconds), enabling the generation and immediate trapping of highly reactive organolithium and organomagnesium intermediates that would decompose under standard batch conditions [9].

- Telescoped Multistep Synthesis: Unstable organometallic intermediates generated in one reactor can be directly pumped into a second reactor containing an electrophile or a transmetalation agent, enabling complex, multistep sequences without isolation [9]. For example, continuous flow lithiation-electrophile trapping protocols have been scaled for the synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates like fenofibrate and montelukast [9].

Directed Ortho-Metalation (DoM) as a Powerful Tool

Directed ortho-metalation (DoM) using organolithium reagents is a premier strategy for the regioselective functionalization of aromatic rings. A directing metalation group (DMG) on the arene coordinates to the lithium atom, steering the deprotonation to the adjacent ortho position. This overcomes the limitations of traditional electrophilic substitution, allowing for the predictable synthesis of polysubstituted aromatics [17]. The resulting aryl lithium species can then be trapped with a wide range of electrophiles (e.g., alkyl halides, carbonyl compounds, halogens) or transmetalated to other metals like zinc or boron for further cross-coupling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues key reagents and materials commonly used in modern organometallic research and synthesis, highlighting their specific functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Modern Organometallic Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| iPrMgCl·LiCl ("Turbo-Grignard") | Highly soluble Grignard reagent for efficient halogen-magnesium exchange under mild conditions, enabling preparation of functionalized aryl magnesium reagents [19] [20]. |

| TMPMgCl·LiCl / TMPZnCl·LiCl | Powerful yet non-nucleophilic bases for regioselective directed metalation of sensitive heterocycles and arenes, tolerating a wide range of functional groups [19] [20]. |

| LiCl Additive | Critical additive for activating zinc metal and facilitating the solubilization of organozinc intermediates from the metal surface during oxidative addition, enabling milder reaction conditions [22]. |

| Iron Catalysts (e.g., Fe(acac)₃) | Abundant, non-toxic, and sustainable catalysts for coupling reactions, recently shown to be effective with traditionally challenging organosodium reagents for homocoupling and cross-coupling [21]. |

| Bidentate Donor Additives (e.g., DMI, DMPU) | Used to control aggregation and reactivity of highly ionic organometallic species (e.g., organosodium); crucial for achieving selectivity in iron-catalyzed couplings [21]. |

| Continuous Flow Microreactor | Engineered system for safe and efficient execution of fast, exothermic organometallic reactions, providing superior mixing, thermal control, and handling of unstable intermediates [9]. |

Organolithium, organomagnesium, and organozinc reagents each occupy a vital and distinct niche in the synthetic chemist's arsenal. The choice between them is dictated by a balance of reactivity, functional group tolerance, and the specific transformation required. The ongoing evolution of this field is being shaped by several clear trends: the push towards more sustainable and abundant metals, as seen in the renaissance of iron catalysis and the exploration of organosodium chemistry [21]; the integration of continuous flow technology to enhance safety and access novel reactivity [9]; and the development of ever-more sophisticated reagent systems like "turbo-Grignards" and TMP-bases that expand the scope of possible transformations [19] [20]. A deep understanding of the comparative kinetics and mechanisms of transmetalation processes involving these reagents remains fundamental to driving innovation in catalytic cross-coupling and complex molecule synthesis.

Advanced Kinetic Methodologies and Synthetic Applications

Within synthetic chemistry, particularly in the development of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and complex organic molecules, the choice of reactor system profoundly impacts the efficiency, safety, and scalability of a process. While batch chemistry has long been the traditional mainstay, continuous flow chemistry has emerged as a transformative platform that directly addresses numerous limitations inherent to batch processing [23]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methodologies, focusing on their performance in mixing, thermal control, and scalability. The analysis is framed within a critical research context: the kinetic study of transmetalation reactions, a class of highly sensitive and rapid organometallic transformations pivotal to modern synthetic chemistry [9]. The superior characteristics of continuous flow systems enable not only safer and more efficient execution of these reactions but also facilitate more precise kinetic studies, thereby accelerating process development and optimization for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis: Batch vs. Continuous Flow Chemistry

The fundamental difference between the two methodologies lies in their operation: batch chemistry involves combining all reactants in a single vessel where the reaction proceeds over a set time, whereas continuous flow chemistry involves pumping reactants through a tubular reactor where the reaction occurs during transit [23]. This core operational distinction gives rise to significant differences in performance, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of batch and continuous flow chemistry characteristics.

| Feature | Batch Chemistry | Continuous Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Flexible mid-reaction adjustments; suitable for exploratory synthesis [23]. | Superior precision over residence time, temperature, and mixing; ideal for optimized processes [23]. |

| Mixing Efficiency | Limited by stirring efficiency; can be inhomogeneous, leading to side reactions [23]. | Excellent mixing due to small internal diameters; enhanced mass transfer improves selectivity [9]. |

| Heat Transfer & Thermal Control | Limited surface-to-volume ratio; risk of localized hot spots and runaway reactions [24]. | High surface-to-volume ratio enables excellent heat management and isothermal operation [25] [9]. |

| Scalability | Scale-up is complex and nonlinear; requires re-optimization at larger vessel sizes [23]. | Seamless scale-up via "numbering-up" or increased flow rates; minimal re-optimization needed [11] [23]. |

| Safety | Higher risk for hazardous reactions due to large volumes of reagents [23]. | Inherently safer; small reagent volumes at any given time mitigate risks [23] [9]. |

| Reaction Time | Typically hours to days [26]. | Drastically reduced; often minutes to hours [26]. |

| Suitability for Sensitive Intermediates | Challenging; intermediates accumulate and can degrade [9]. | Ideal; unstable intermediates are generated and consumed immediately [9]. |

Application in Transmetalation Reaction Kinetics

The study of reaction kinetics, especially for fast and exothermic reactions like transmetalation, is a area where continuous flow systems offer distinct advantages over traditional batch methods.

The Kinetic Analysis Challenge in Batch

In batch reactors, obtaining reliable kinetic data for transmetalation reactions is challenging. These reactions are often highly exothermic and sensitive to mixing efficiency, which can lead to localized hot spots and concentration gradients [9]. This results in side reactions and byproduct formation, corrupting the kinetic data. Furthermore, the rapid consumption of reagents and potential degradation of sensitive organometallic intermediates make it difficult to collect consistent, time-point samples that accurately represent the reaction profile [27].

The Continuous Flow Advantage

Continuous flow reactors enable a more reliable approach to kinetic analysis. A key methodology is the acquisition of kinetic data at steady state [27]. By maintaining constant flow rates, temperature, and pressure, the system reaches a steady state where the product composition remains constant over time. Researchers can then systematically vary one parameter, such as residence time (adjusted via flow rate) or temperature, to determine its effect on conversion and yield. This approach, combined with in-line analytical tools, provides a rich and highly accurate dataset for kinetic modeling [27] [28].

Diagram: Workflow for kinetic analysis of transmetalation reactions in continuous flow.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Case Study: Barbier-Type Transmetalation in Flow

A robust transmetalation protocol was reported by the Knochel group, showcasing the capabilities of continuous flow systems [9].

- Objective: To perform a transmetalation of an organolithium intermediate to an organozinc species, followed by trapping with an electrophile.

- Challenge: Organolithium compounds are highly reactive and prone to decomposition, making their controlled generation and use in batch difficult.

- Flow Setup and Procedure:

- Feedstreams: Two precursor solutions are prepared: an aryl halide in a solvent and a base such as lithium diisopropylamide (LDA).

- Lithiation: The streams are pumped into a temperature-controlled microreactor (e.g., at -20 °C to -78 °C) with a precise residence time to generate the aryllithium intermediate.

- Transmetalation: The resulting stream is immediately mixed with a solution of a zinc salt (e.g., ZnCl₂) in a second reactor. The efficient mixing ensures rapid and complete transmetalation to form the arylzinc species.

- Quenching: The organozinc stream is then mixed with an electrophile (e.g., an acid chloride or allylic bromide) in a final reactor coil to yield the desired coupled product.

- Key Outcome: The process benefits from rapid mixing and short, precisely controlled residence times, which significantly reduce side reactions associated with the sensitive organolithium and organozinc intermediates, leading to higher yields and purities [9].

Table 2: Quantitative performance data for chemical synthesis in different reactor systems.

| Process / Metric | Batch Reactor Performance | Continuous Flow Reactor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| General Scalability | Non-linear scale-up; requires re-optimization [23]. | Linear scale-up via numbering-up; 60 g/h demonstrated for MOFs [26]. |

| Particle Size Control | Broad distribution [26]. | Precise control (e.g., 100 nm to 1 μm for MOFs) [26]. |

| Heat Transfer Coefficient (U) | Lower, due to limitations of stirred tank design [24]. | Significantly higher, enabling more efficient cooling/heating [24]. |

| Space-Time Yield (STY) | Lower; limited by heat/mass transfer [26]. | Exceptional; e.g., 4533 Kg·m⁻³·day⁻¹ for HKUST-1 MOF [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and equipment for continuous flow transmetalation experiments.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Syringe or HPLC Pumps | To deliver reagent solutions at a constant and precise flow rate [26]. |

| Temperature-Controlled Microreactors | Typically PFA or stainless-steel coils; provide a controlled environment for reaction steps [9]. |

| T-Mixers or Static Mixers | To ensure rapid and efficient mixing of different reagent streams [9]. |

| Organolithium Bases (e.g., LDA) | To perform directed lithiation or halogen-lithium exchange on substrate [9]. |

| Zinc Salts (e.g., ZnCl₂) | To transmetalate the organolithium intermediate to a more stable organozinc species [9]. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) | To maintain a constant pressure within the system, preventing solvent degassing [26]. |

| In-line Analytic (e.g., FTIR) | For real-time monitoring of reaction conversion and intermediate formation [28]. |

The objective evidence comparing batch and continuous flow chemistry consistently highlights the latter's superior performance in mixing, thermal control, and scalable synthesis. For the specific case of kinetic studies in transmetalation reactions, the continuous flow paradigm is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental enabler. It permits the safe handling of sensitive organometallic species, provides the precise control necessary for high-quality kinetic data acquisition, and offers a direct and predictable path from laboratory discovery to industrial production. As the demands for efficiency, safety, and sustainability in chemical synthesis continue to grow, continuous flow systems are poised to become an indispensable tool in the arsenal of researchers and process chemists.

Phase-transfer catalysis (PTC) has emerged as an indispensable methodology for conducting reactions between reagents residing in immiscible liquid phases, typically aqueous and organic solvents. This technique enables the transfer of ionic reagents from the aqueous or solid phase into the organic phase where reaction with organic substrates occurs, overcoming inherent solubility limitations that would otherwise impede reactive contact. The fundamental principle involves a catalyst, often a quaternary ammonium or phosphonium salt, that shuttles between phases, facilitating the transport of anionic species as lipophilic ion pairs. This process dramatically enhances reaction rates, improves yields, and permits milder reaction conditions compared to conventional single-phase systems.

The economic and environmental significance of PTC systems extends across multiple industrial domains, including pharmaceutical synthesis, agrochemical production, polymer chemistry, and specialty chemical manufacturing. The technology aligns with green chemistry principles by potentially avoiding hazardous organic solvents, reducing energy consumption through lower temperature requirements, and minimizing waste generation. From an engineering perspective, biphasic PTC systems offer the distinct advantage of facile catalyst separation and recycling, bridging the gap between homogeneous catalysis's high efficiency and heterogeneous catalysis's easy separation. The following sections provide a comprehensive comparison of various PTC systems, their kinetic behaviors, solvent effects, and applications in synthetic chemistry, with particular emphasis on transmetalation reactions central to cross-coupling methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Phase-Transfer Catalyst Systems

Catalyst Types and Structural Features

Phase-transfer catalysts exhibit considerable structural diversity, each with distinct advantages for specific applications. Traditional single-site PTCs, such as tetraalkylammonium salts, contain one catalytic center per molecule and have been widely employed since the technology's inception. More recently, multi-site phase-transfer catalysts (MPTCs) have been developed, featuring multiple catalytic centers within a single molecule. These MPTCs demonstrate enhanced economic and efficiency benefits due to their ability to transport multiple anions simultaneously during each catalytic cycle. For instance, 1,4-bis-(propylmethyleneammounium chloride)benzene (BPMACB) represents a bis-quaternary ammonium compound that significantly accelerates polymerization reactions compared to conventional single-site catalysts [29].

The structural evolution of PTCs has expanded their application scope. In aqueous biphasic hydroformylation, polymer latices created through microemulsion polymerization and nonionic surfactant micelles have been employed as effective phase mediators. These systems enable the conversion of higher alkenes (≥C6) that exhibit insufficient water solubility for direct application of aqueous biphasic protocols. Polymer latices maintain a biphasic system with excess alkene phase, where hydrophobic cores encapsulate substrate molecules, enabling reaction at the aqueous phase interface through electrostatic interactions with water-soluble catalysts. Conversely, nonionic surfactants can form water-in-oil microemulsions under reaction conditions, creating inverse micelles that encapsulate the catalyst within a continuous organic phase, thereby enhancing interfacial contact areas [30].

Table 1: Comparative Features of Phase-Transfer Catalyst Types

| Catalyst Type | Structural Features | Key Advantages | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-site PTC | Single quaternary ammonium/phosphonium center | Wide commercial availability, established applications | Tetrabutylammonium bromide, Benzyltriethylammonium chloride |

| Multi-site PTC (MPTC) | Multiple catalytic centers per molecule | Higher efficiency per molecule, cost reduction | 1,4-bis(propylmethyleneammonium chloride)benzene (BPMACB) |

| Polymer-supported PTC | Catalytic sites bound to polymer matrix | Facile recovery and reuse, continuous operation potential | Polymer latices with embedded catalytic sites |

| Surfactant-based PTC | Amphiphilic structure with hydrophilic-lipophilic balance | Forms microemulsions, greatly increased interfacial area | Marlophen NP 9, Marlipal 24/70 |

Performance Metrics in Model Reactions

The efficacy of different PTC systems can be quantitatively assessed through their performance in representative transformations. In the aqueous biphasic hydroformylation of higher alkenes using a rhodium-SulfoXantPhos catalyst system, both polymer latices and nonionic surfactant micelles demonstrate concentration-dependent activity enhancements. Higher PTC concentrations generally correlate with improved reaction progress, with surfactant systems exhibiting particularly low rhodium losses—a critical consideration for technical implementation and catalyst recycling [30].

In Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions under biphasic conditions, the incorporation of phase-transfer catalysts generates remarkable 12-fold rate enhancements. This dramatic acceleration stems from a fundamental shift in the transmetalation mechanism from an oxo-palladium pathway to a boronate-based pathway. The PTC facilitates this mechanistic switch by enabling direct transmetalation between the arylpalladium(II) halide complex and the tetracoordinate (8-B-4) arylboronate species, bypassing the requirement for hydroxide-mediated preactivation [31]. This pathway alteration underscores the profound influence that PTCs can exert on fundamental reaction mechanisms beyond simple mass transfer improvements.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PTC Systems in Various Reactions

| Reaction System | Catalyst Type | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroformylation of 1-dodecene | Nonionic surfactant (Marlophen NP 9) | High conversion, low Rh losses (<1%), effective catalyst recycling | [30] |

| Suzuki-Miyaura coupling | Tetraalkylammonium salts | 12-fold rate enhancement, shift in transmetalation pathway | [31] |

| Polymerization of MABE | Multi-site PTC (BPMACB) | Rate enhancement up to 70× vs. batch, high molecular weight polymers | [29] |

| Benzoin condensation | Quaternary ammonium salts | Modeled yield >90% with optimal solvent/PTC combination | [32] |

Solvent Effects and Reaction Engineering

Thermodynamic Considerations and Modeling

The design and optimization of PTC systems necessitate comprehensive understanding of the thermodynamic principles governing solute partitioning between phases. A systematic modeling framework has been developed to predict physical and chemical equilibria in PTC systems with minimal experimental data requirements. This framework incorporates thermodynamic models such as NRTL, eNRTL, SAC, and e-KT-UNIFAC to estimate partition coefficients of species between aqueous and organic phases—a critical parameter influencing reaction rates and selectivity [32].

The partition behavior of PTCs themselves significantly impacts system performance. For quaternary ammonium salts, the equilibrium between ionic forms in the aqueous phase (Q+X⁻) and neutral ion pairs in the organic phase (QY) governs catalytic efficiency. Model-based analyses reveal that solvent selection dramatically affects this equilibrium, with factors such as dielectric constant, hydrogen bonding capacity, and hydrophobicity determining the extent of ion-pair extraction. For instance, in benzoin condensation and chlorination of organobromines, predictive models successfully identify optimal solvent-PTC combinations that maximize product yield while minimizing impurities [32].

Interfacial Phenomena and Mass Transfer

In biphasic systems, reaction rates often depend on interfacial area and mass transfer efficiency rather than intrinsic kinetics. The presence of PTCs alters interfacial tension, potentially increasing the available contact area between phases. Additionally, certain PTC systems, particularly surfactant-based approaches, can generate microemulsions with interfacial areas several orders of magnitude greater than conventional stirred systems. These microemulsions exist as thermodynamically stable, optically isotropic dispersions characterized by extremely low droplet sizes (typically 10-100 nm), which dramatically enhance mass transfer rates [30].

Engineering parameters such as stirring rate, temperature, and phase ratio significantly influence reaction performance through their effects on mass transfer. In aqueous biphasic hydroformylation, the transition from micelles in the aqueous phase to inverse micelles in the organic phase under reaction conditions substantially improves substrate-catalyst contact. This microstructural evolution, reversible upon cooling for product separation, represents a key advantage of thermoregulated surfactant-based PTC systems [30].

Experimental Protocols for PTC Evaluation

Hydroformylation of Higher Alkenes with Surfactant PTCs

Objective: To evaluate the efficiency of nonionic surfactants as phase-transfer agents in the aqueous biphasic hydroformylation of 1-dodecene using a water-soluble rhodium-SulfoXantPhos catalyst.

Reagents and Materials:

- Rh(acac)(CO)₂ precursor (0.025 mmol)

- SulfoXantPhos ligand (0.1 mmol, metal/ligand ratio = 1/4)

- 1-Dodecene (50 mmol)

- Nonionic surfactant (e.g., Marlophen NP 9, 5-10 wt%)

- Water (25 mL) and organic phase (typically 2:1 organic-to-water volume ratio)

Procedure:

- Prepare the catalyst complex by preforming with Rh precursor and ligand in water.

- Charge aqueous catalyst solution, surfactant, and 1-dodecene to a pressurized reactor.

- Purge the system with syngas (CO:H₂ = 1:1) and pressurize to 10-20 bar.

- Heat with stirring to reaction temperature (80-120°C) and monitor pressure drop.

- Maintain constant pressure by syngas replenishment during reaction.

- After reaction completion, cool to room temperature for phase separation.

- Analyze organic phase by GC for conversion and aldehyde selectivity.

- Determine rhodium leaching to organic phase by ICP-MS.

Key Observations: Systems forming three-phase regions (oil, microemulsion, water) at reaction temperature typically exhibit superior conversion rates. Surfactants with lower ethoxylation degrees (e.g., Marlipal 24/70 with n=7) facilitate three-phase system formation at lower temperatures, enabling efficient hydroformylation under milder conditions [30].

Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling with PTC Acceleration

Objective: To investigate the rate enhancement effect of phase-transfer catalysts in the biphasic Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of benzyl bromide with 4-methoxyphenylboronic acid pinacol ester.

Reagents and Materials:

- XPhos Pd G2 catalyst (0.5-2 mol%)

- Benzyl bromide (1.0 mmol)

- 4-Methoxyphenylboronic acid pinacol ester (1.2 mmol)

- Phase-transfer catalyst (e.g., tetrabutylammonium bromide, 10 mol%)

- Potassium phosphate tribasic (2.0 mmol)

- 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF) and water (typically 1:1 v/v)

Procedure:

- Charge organic substrates and Pd catalyst to reaction vessel.

- Add aqueous solution containing base and PTC.

- Stir vigorously at room temperature with automated sampling.

- Analyze reaction progress by HPLC with UV detection.

- Monitor boronate speciation to distinguish transmetalation pathways.

- Compare initial rates and full conversion time profiles with and without PTC.

- Determine kinetic orders by variable time normalization analysis (VTNA).

Key Observations: PTC incorporation typically generates substantial rate enhancements (up to 12-fold) accompanied by a mechanistic shift from oxo-palladium to boronate transmetalation pathway. Reactions exhibit approximately first-order dependence on catalyst and 1.8-order dependence on base, consistent with rate-determining transmetalation with base-mediated pre-equilibrium [31].

Kinetic Studies of Transmetalation Reactions

Mechanistic Pathways in Transmetalation

Transmetalation, the transfer of an organic group from a main group element to a transition metal, represents a fundamental step in cross-coupling reactions. In Suzuki-Miyaura couplings, two competing pathways have been identified: the boronate pathway (Path A) involving direct reaction between LnPd(aryl)(X) and a tetracoordinate (8-B-4) arylboronate, and the oxo-palladium pathway (Path B) proceeding through a LnPd(aryl)(OH) intermediate generated by halide-hydroxide exchange. Under conventional biphasic conditions, Path B typically dominates; however, introduction of PTCs shifts the preference toward Path A, resulting in significant rate enhancements [31] [7].

The existence of Pd-O-B-containing intermediates, long postulated as the "missing link" in Suzuki-Miyaura transmetalation, has been confirmed through low-temperature rapid injection NMR spectroscopy. These studies have identified and characterized two distinct intermediates: a tricoordinate (6-B-3) boronic acid complex and a tetracoordinate (8-B-4) boronate complex, both of which undergo transmetalation to yield cross-coupling products. The relative contribution of each pathway depends critically on reaction conditions, including ligand concentration, solvent system, and the presence of phase-transfer agents [7].

Kinetic Analysis Techniques

Elucidating transmetalation mechanisms requires specialized kinetic analysis techniques adapted for biphasic systems. Variable time normalization analysis (VTNA) has emerged as a powerful method for determining reagent orders in complex reaction networks. This approach involves conducting parallel reactions with different initial reagent concentrations and analyzing the time-dependent concentration profiles to extract reaction orders. For PTC-enhanced Suzuki-Miyaura couplings, VTNA has established approximately first-order dependence on palladium catalyst, 0.75-order dependence on boronic ester, and 1.8-order dependence on base [31].

Automated sampling platforms coupled with online HPLC analysis address the reproducibility challenges inherent in biphasic kinetic studies. These systems enable highly reproducible sampling and analysis while avoiding artifacts associated with sample aging. Additionally, rapid injection NMR techniques permit direct observation of transient intermediates with half-lives as short as several seconds, providing unprecedented insight into the transmetalation process [31] [7].

Figure 1: Transmetalation pathway shift induced by phase-transfer catalysts in Suzuki-Miyaura coupling

Advanced Reactor Technologies for Biphasic Catalysis

High-Performance Liquid/Liquid Counter Current Chromatography

High-performance liquid/liquid counter current chromatography (HPCCC) represents a revolutionary approach to biphasic reaction engineering that dramatically accelerates reaction rates through intensified mixing. This technology utilizes a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tube coiled onto a rotating drum that simultaneously revolves around its central axis while rotating around its own axis, creating wave-mixing effects equivalent to more than two million partitioning events per hour. The enormous interfacial area generated enables remarkable rate enhancements—up to 70-fold compared to traditional batch reactors and 10-fold compared to segmented flow systems [33].

HPCCC has demonstrated exceptional utility in stereoselective phase-transfer catalyzed reactions and biocatalytic processes. In the stereoselective alkylation of N-(diphenylmethylene)glycine tert-butyl ester, HPCCC achieved 73% yield with 87% enantiomeric excess in just 10.7 minutes residence time, substantially outperforming both batch and segmented flow systems. Similarly, lipase-catalyzed transesterification of octanol with vinyl acetate proceeded quantitatively in 6 minutes under HPCCC conditions, compared to 40% yield after 4.5 hours in conventional batch reactors [33].

Ultrasound-Assisted Phase-Transfer Catalysis

The synergistic combination of ultrasound irradiation with phase-transfer catalysis (US-PTC) represents another innovative approach to process intensification. Ultrasound induces cavitation phenomena that generate extreme local temperatures and pressures while producing intense micro-mixing at phase boundaries. In the polymerization of methacrylic acid butyl ester (MABE) using a multi-site PTC, ultrasound assistance significantly increased reaction rates compared to silent (non-ultrasonic) conditions [29].