Comparative Efficacy of Inorganic Semiconductors in Pollutant Degradation: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of inorganic semiconductors for the photocatalytic degradation of environmental pollutants, a critical concern for researchers in environmental science and public health.

Comparative Efficacy of Inorganic Semiconductors in Pollutant Degradation: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of inorganic semiconductors for the photocatalytic degradation of environmental pollutants, a critical concern for researchers in environmental science and public health. It establishes the foundational principles of semiconductor photocatalysis, including band gap engineering and charge carrier dynamics. The article systematically compares synthesis methodologies, from chemical and biological routes to advanced deposition techniques like electrodeposition and flame spraying, linking them to catalytic performance in degrading dyes, pharmaceuticals, and other contaminants. It addresses key operational challenges, including charge recombination and catalyst stability, while presenting optimization strategies. Finally, the review offers a rigorous, evidence-based validation of various semiconductors—such as ZnO, TiO₂, γ-MnO₂, NiO, and composite heterojunctions—benchmarking their degradation efficiencies, kinetics, and reusability to guide material selection for advanced wastewater treatment and potential biomedical applications.

Fundamental Principles and Material Diversity of Semiconductor Photocatalysts

The Fundamental Photocatalytic Mechanism

Photocatalysis is an advanced oxidation process that utilizes semiconductor materials to degrade organic pollutants in wastewater. The process begins when a photocatalyst absorbs light with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, prompting electrons ((e^-)) to jump from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), thereby generating electron-hole pairs ((e^-/h^+)) [1]. The photogenerated holes in the VB possess strong oxidizing potential, capable of directly oxidizing pollutants or reacting with water molecules ((H2O)) or hydroxide ions ((OH^-)) to produce hydroxyl radicals ((•OH)) [1]. Simultaneously, electrons in the CB reduce oxygen molecules ((O2)) adsorbed on the catalyst surface to form superoxide anion radicals ((•O2^-)) [2]. These reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly (•OH) and (•O2^-), are highly oxidizing and non-selective, enabling them to decompose complex organic pollutants into smaller, less harmful molecules such as carbon dioxide and water [1] [2].

The entire process encompasses several critical stages: light absorption and charge carrier generation, charge separation and migration to the surface, and finally, surface redox reactions producing ROS that degrade pollutants [2]. The efficiency of photocatalysis depends on the catalyst's ability to effectively absorb light, minimize the recombination of electron-hole pairs, and provide active sites for ROS generation and pollutant degradation.

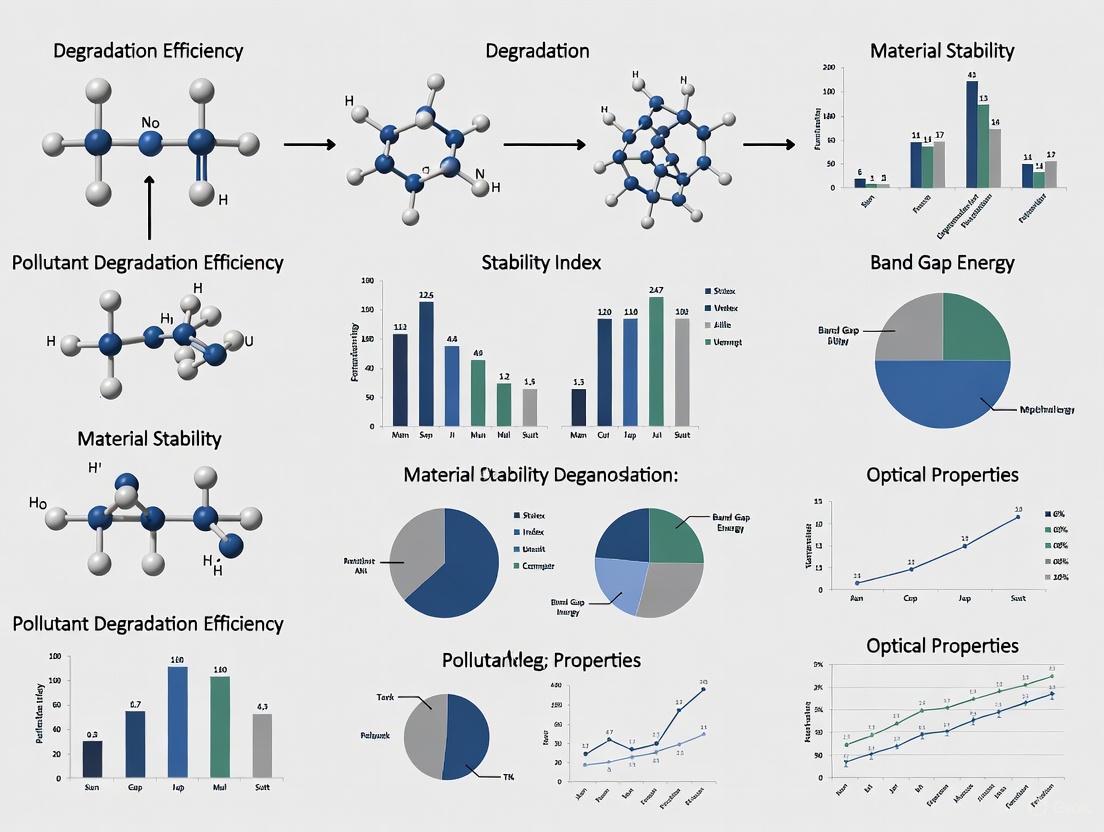

Figure 1: Fundamental steps of the photocatalytic mechanism, from light absorption to pollutant degradation.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation Pathways

Reactive oxygen species are decisive actors in photocatalytic redox chemistry, dictating both the selectivity and efficiency of pollutant degradation [2]. The primary ROS and their formation pathways in a photocatalytic system are detailed below.

Superoxide Anion Radical ((•O2^-)): This is often the primary ROS generated when photoexcited electrons reduce molecular oxygen: (O2 + e^- → •O2^-) [2]. The feasibility of this process requires that the conduction band potential of the semiconductor is more negative than the redox potential of the (O2/•O_2^-) couple (-0.33 V) [2]. These radicals can either directly oxidize substrates or undergo protonation to form hydroperoxyl radicals ((•OOH)) [2].

Hydroxyl Radical ((•OH)): These highly oxidative species are primarily generated when photogenerated holes oxidize water molecules or hydroxide ions: (h^+ + H2O → •OH + H^+) or (h^+ + OH^- → •OH) [1]. Hydroxyl radicals can also form from the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide ((H2O_2)) [2].

Hydrogen Peroxide ((H2O2)): This intermediate ROS forms primarily via a two-electron reduction of oxygen: (O2 + 2e^- + 2H^+ → H2O2) [2]. It can also be generated through the dismutation of (•O2^-) [2].

Singlet Oxygen ((^1O2)): This excited state of molecular oxygen is typically generated through energy transfer from the photoexcited catalyst to triplet oxygen ((^3O2)) [2].

Figure 2: Primary pathways for generating different Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in photocatalysis.

Comparative Performance of Semiconductor Photocatalysts

Key Photocatalytic Materials and Their Efficiencies

Extensive research has focused on various semiconductor photocatalysts for pollutant degradation. The table below summarizes the performance of prominent materials as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative photocatalytic performance of different semiconductors for pollutant degradation

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Experimental Conditions | Degradation Efficiency | Time Required | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO (Ethanol-synthesized) | Methylene Blue (5 mg/L) | 0.1 g catalyst, UV light | 98% | "Rapid" / "Brief duration" | Solvent choice (ethanol) critically influenced performance, yielding superior results vs. 1-propanol/1,4-butanediol. | [3] |

| TiO₂-Clay Nanocomposite (70:30) | Basic Red 46 (20 mg/L) | Rotary photoreactor, UV light | 98% (Dye), 92% (TOC) | 90 min | Hydroxyl radicals identified as primary oxidative species; >90% efficiency maintained after 6 cycles. | [1] |

| Biosynthesized NiO-NPs | Methylene Blue | Visible light | 90% | 1 min | Showed significantly faster degradation rates compared to chemically synthesized counterparts. | [4] |

| Chemically Synthesized NiO-NPs | Methylene Blue | Visible light | 90% | 5 min | Effective but slower than biogenic NPs; required 5x longer for similar degradation. | [4] |

| Biosynthesized NiO-NPs | 4-Nitrophenol | Visible light | 65% | 25 min | Demonstrated capability to degrade more resistant pollutants effectively. | [4] |

| Bimetallic/TiO₂ + H₂O₂ | p-Nitrophenol (PNP) | Optimized conditions with oxidants | High | N/A | Degradation efficacy strongly influenced by oxidants: H₂O₂ > K₂S₂O₈ > air. | [5] |

Advanced Material Designs for ROS Regulation

Recent research focuses on tailoring photocatalysts to selectively generate specific ROS for enhanced efficiency and application-specific performance [2].

Polymeric Carbon Nitride (PCN) Modulation: The tunable band structure and surface chemistry of metal-free PCN make it an excellent scaffold for controlled ROS generation. Strategies like molecular doping, defect engineering, and heterojunction construction can precisely tailor the ROS profile, for instance, favoring singlet oxygen ((^1O2)) via energy transfer or steering electron–proton coupling to yield (H2O_2) instead of (•OH) [2].

Long-Lived Oxygen-Centered Organic Radicals (OCORs): A novel approach involves catalysts that generate ultra-stable OCORs with half-lives up to several minutes, enabling highly efficient pollutant degradation even under ultra-low light intensities (as low as 0.1 mW cm⁻²). These long-lived radicals can effectively wait for pollutants to diffuse, overcoming a major limitation of traditional transient radicals that quench rapidly [6].

Experimental Protocols for Photocatalytic Studies

Standard Photocatalytic Degradation Assay

A typical experimental procedure for evaluating photocatalytic activity involves the following steps, as exemplified by the degradation of methylene blue (MB) using ZnO nanoparticles [3]:

Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize photocatalyst (e.g., ZnO via sol-gel method using zinc acetate dihydrate and oxalic acid in solvent like ethanol). Calcinate the precursor (e.g., zinc oxalate) at high temperature (e.g., 600°C for 240 min) to obtain the final metal oxide [3].

Reaction Setup: Prepare a solution of the target pollutant (e.g., 100 mL of MB dye at 5 mg/L concentration). Add a specific amount of catalyst (e.g., 0.1 g of ZnO powder) to the solution [3].

Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Stir the mixture in the dark for a period (typically 30 minutes) to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the dye and catalyst surface before light irradiation.

Light Irradiation: Expose the mixture to a light source (e.g., UV light using Philips TL 8W BLB lamps placed 15 cm from the sample) under continuous stirring [3].

Sampling and Analysis: At regular time intervals, withdraw samples, centrifuge to remove catalyst particles, and analyze the supernatant using UV-Vis spectrophotometry to measure the residual dye concentration at its maximum absorbance wavelength (e.g., 664 nm for MB) [3].

The degradation efficiency is calculated as: ( \text{Efficiency} (\%) = \frac{C0 - Ct}{C0} \times 100 ), where (C0) is the initial concentration and (C_t) is the concentration at time (t).

Identification of Dominant Reactive Species

Radical scavenger experiments are crucial for identifying the primary ROS responsible for degradation [1]. The protocol involves:

Selecting Scavengers: Use specific compounds that quench particular ROS. Examples include isopropanol for hydroxyl radicals ((•OH)), p-benzoquinone for superoxide anions ((•O2^-)), and sodium azide for singlet oxygen ((^1O2)) [2] [1].

Running Parallel Experiments: Conduct degradation tests under identical optimal conditions with and without the addition of scavengers.

Comparing Efficiency: A significant decrease in degradation efficiency in the presence of a specific scavenger indicates that the corresponding ROS plays a major role in the process. For instance, a study on a TiO₂-clay system confirmed (•OH) as the primary oxidative species through this method [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key reagents, materials, and equipment for photocatalytic research

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Catalysts | TiO₂-P25 [1], ZnO [3], NiO-NPs [4], Polymeric Carbon Nitride (PCN) [2] | Primary light-absorbing material; generates charge carriers and ROS. | Basis of the photocatalytic process; choice depends on bandgap, stability, and cost. |

| Support Materials | Industrial Clay [1], Silicone Adhesive [1] | Increases surface area, prevents aggregation, enables catalyst immobilization. | Enhances pollutant adsorption and facilitates catalyst recovery in reactor systems. |

| Target Pollutants | Methylene Blue (MB) [3] [4], Basic Red 46 (BR46) [1], p-Nitrophenol (PNP) [5], 4-Nitrophenol (4-NP) [4] | Model compounds for evaluating photocatalytic activity. | Represent common, stable water pollutants; allow for standardized performance comparison. |

| Oxidants / Electron Acceptors | Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [5], Potassium Persulfate (K₂S₂O₈) [5] | Enhances degradation by consuming electrons, reducing e⁻/h⁺ recombination. | Efficacy typically follows H₂O₂ > K₂S₂O₈ > air [5]. |

| Radical Scavengers | Isopropanol, p-Benzoquinone, Sodium Azide, Sodium Bicarbonate [2] [1] | Identifies dominant ROS mechanism by selectively quenching specific radicals. | Critical for mechanistic studies to confirm the primary reactive species involved. |

| Synthesis Precursors | Zinc Acetate Dihydrate [3], Nickel Chloride [4], Bacterial Strains (e.g., Pseudochrobactrum sp.) [4] | Raw materials for catalyst preparation via chemical or biological routes. | Influences final catalyst properties like morphology, crystallinity, and activity [3] [4]. |

| Light Sources | UV-C Lamps (8W) [1], Philips TL 8W BLB Lamps [3], Visible Light Sources | Provides photoenergy required to excite the semiconductor catalyst. | Determines the activation spectrum and energy input of the system. |

| Characterization Techniques | XRD, SEM, FT-IR, UV-Vis DRS, PL Spectroscopy, BET Surface Area Analysis [3] [1] [4] | Analyzes crystal structure, morphology, functional groups, optical properties, and surface area. | Essential for linking material properties to observed photocatalytic performance. |

The escalating crisis of water pollution, driven by industrial discharge of synthetic antibiotics and dyes, has intensified the search for advanced remediation technologies [7]. Among these, semiconductor photocatalysis has emerged as a leading solution due to its potential to utilize solar energy for complete mineralization of stable organic pollutants [7] [8]. The efficacy of this process hinges critically upon three fundamental material properties: band gap energy, which determines light absorption range; charge carrier separation, which affects quantum efficiency; and surface area, which governs reactant accessibility [7] [9] [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how these properties govern the photocatalytic performance of prominent inorganic semiconductors, presenting systematically organized experimental data to enable informed material selection for environmental applications.

Comparative Analysis of Semiconductor Properties and Performance

The relationship between intrinsic semiconductor properties and their resulting photocatalytic performance can be quantitatively evaluated through standardized pollutant degradation studies. The data reveal how strategic material design directly enhances functional outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Semiconductor Photocatalysts for Pollutant Degradation

| Photocatalyst | Band Gap (eV) | Surface Area (m²/g) | Pollutant | Degradation Efficiency (%) | Time (min) | Key Active Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-C3N4/P-C3N4 (Z-scheme) | 2.78 (est.) | Not Specified | Tetracycline (TC) | 99.1% | 60 | ·O₂⁻, ·OH, h⁺ [7] |

| Rhodamine B (RhB) | 86.8% | 60 | ·O₂⁻, ·OH, h⁺ [7] | |||

| UIO-67-NH2 (MOF) | Not Specified | 1282 | Methyl Orange (MO) | High (4.0 mg/L/min) | Not Specified | ·OH [9] |

| 5% W/b-TiO2 NPs | Not Specified | Increased vs. pristine | Methylene Blue (MB) | >91% | 120 | Not Specified [11] |

| Fe-doped WO3/BiVO4 | Reduced vs. pristine | Not Specified | Rhodamine B (RhB) | 94.3% | 360 | ·OH [12] |

Table 2: Charge Carrier Dynamics and Mineralization Efficiency

| Photocatalyst | Charge Carrier Lifespan | TOC Removal (TC) | TOC Removal (RhB) | Degradation Rate Relative to P25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-C3N4/P-C3N4 (Z-scheme) | Significantly Enhanced | 78.2% | 71.8% | Not Specified [7] |

| UIO-67-NH2 (MOF) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | 4.548 times [9] |

| Bi2WO6/ZnIn2S4 (Z-scheme) | Prolonged | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified [10] |

| Fe-doped WO3/BiVO4 | 364 ns (PL Lifetime) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

Synthesis Methodologies

Z-scheme Heterojunction Fabrication (Ni-C₃N₄/P-C₃N₄): The heterojunction is prepared via a solid-state ball milling method. Pre-synthesized nickel-doped carbon nitride (Ni-C₃N₄) and phosphorus-doped carbon nitride (P-C₃N₄) are physically mixed and loaded into a ball milling chamber. The mechanical energy from the grinding balls induces a solid-state reaction, creating a tightly coupled heterojunction interface without the use of solvents [7].

Metal-Organic Framework Synthesis (UIO-67-NH₂): The catalyst is synthesized via a solvothermal reaction. Zirconium chloride (ZrCl₄) and 2-amino-4,4'-biphenyldicarboxylic acid are dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) solvent. The mixture is sealed in a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated to produce light yellow UIO-67-NH₂ crystals, which are then vacuum-filtered and dried [9].

Hydrothermal Doping (W/b-TiO₂ NPs): Tungsten-doped brookite TiO₂ nanoparticles are synthesized via a one-step hydrothermal method. Precursors of TiO₂ along with tungsten source at varying weight percentages (1-10%) are mixed in deionized water. The solution is transferred to an autoclave and heated to 160-180°C for several hours, facilitating W⁶⁺ doping into the TiO₂ lattice and inducing a crystal phase transition [11].

Photocatalytic Testing Protocols

A standard photocatalytic experiment involves the following steps:

Reactor Setup: A defined concentration of the organic pollutant (e.g., 20 mg/L Tetracycline, 10 mg/L Rhodamine B) is prepared in an aqueous solution. A precise dosage of the photocatalyst (e.g., 0.5 g/L for Ni-C₃N₄/P-C₃N₄) is added to the solution [7].

Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: The suspension is stirred in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish an adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the pollutant and the catalyst surface [7].

Light Irradiation: The mixture is exposed to a visible light source (e.g., a 300 W Xe lamp with a UV-cutoff filter). Throughout the irradiation, aliquots are extracted at regular time intervals [7].

Analysis and Quantification:

- Pollutant Concentration: The concentration of the pollutant in the extracted samples is measured using UV-Vis spectrophotometry by tracking the characteristic absorption peak (e.g., 554 nm for RhB, 357 nm for TC) [7] [12].

- Mineralization Efficiency: The degree of complete mineralization is evaluated by measuring the reduction in Total Organic Carbon (TOC) [7].

- Reactive Species Identification: Active species are identified through radical scavenging experiments using specific quenchers like EDTA-2Na for holes (h⁺), isopropanol (IPA) for hydroxyl radicals (·OH), and p-benzoquinone (BQ) for superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻). Further confirmation is provided by Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) spectroscopy [7].

Interplay of Semiconductor Properties in Photocatalytic Mechanisms

The degradation of organic pollutants is a multi-stage process where the key semiconductor properties govern efficiency at each step. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism, from light absorption to pollutant mineralization.

The mechanism involves several critical steps: (1) Photon Absorption, where light with energy equal to or greater than the semiconductor's band gap is absorbed; (2) Electron-Hole Pair Generation, creating charge carriers; (3) Charge Separation and Migration, where carriers move to the surface; (4) Redox Reactions, with electrons reducing O₂ to superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻) and holes oxidizing H₂O/OH⁻ to hydroxyl radicals (·OH); and (5) Pollutant Degradation, where these reactive species mineralize organic pollutants into CO₂ and H₂O [7] [10] [8].

Strategic engineering of heterojunctions profoundly impacts charge carrier separation. The Z-scheme system, in particular, creates a vector for electron-hole recombination at the interface, which selectively preserves the most potent charge carriers for redox reactions.

In this Z-scheme, the photogenerated electrons in the conduction band (CB) of P-C₃N₄ recombine with the holes in the valence band (VB) of Ni-C₃N₄ at the heterojunction interface. This selective recombination preserves the most reducing electrons in the Ni-C₃N₄ CB and the most oxidizing holes in the P-C₃N₄ VB, thereby maintaining strong redox potentials while achieving efficient spatial charge separation [7] [10]. This system achieved a high degradation rate of 99.1% for tetracycline and 86.8% for Rhodamine B within 60 minutes, with substantial mineralization (78.2% and 71.8% TOC removal, respectively) [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalysis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Melamine (C₃H₆N₆) | Precursor for graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) synthesis [7]. | Synthesis of base C₃N₄ material for heterojunction construction [7]. |

| Nickel Acetate (Ni(CH₃COO)₂) | Source for nickel cation (Ni²⁺) doping of semiconductor lattices [7]. | Preparation of Ni-C₃N₄ component to enhance charge transfer [7]. |

| Sodium Dihydrogen Phosphate (NaH₂PO₄) | Source for phosphorus anion (P) doping of semiconductor lattices [7]. | Preparation of P-C₃N₄ component to tune band structure [7]. |

| Zirconium Chloride (ZrCl₄) | Metal cluster node for constructing Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [9]. | Synthesis of UIO-67-NH₂ framework, providing structural stability [9]. |

| 2-amino-4,4'-biphenyldicarboxylic Acid | Organic linker for MOF synthesis; amino group enables visible light response [9]. | Construction of UIO-67-NH₂, yielding high surface area (1282 m²/g) [9]. |

| Tungsten Precursors | Source for W⁶⁺ dopant ions to modify host semiconductor properties [11]. | Doping of brookite TiO₂ to reduce grain size and enhance activity [11]. |

| Radical Scavengers (e.g., IPA, BQ, EDTA-2Na) | Chemical traps to identify the role of specific reactive species during catalysis [7]. | Mechanistic studies to confirm dominant active species (·OH, ·O₂⁻, h⁺) [7]. |

| Tetracycline (TC) & Rhodamine B (RhB) | Model organic pollutant molecules for standardized performance testing [7]. | Benchmarking degradation efficiency and mineralization (TOC removal) [7]. |

The comparative data and protocols presented in this guide establish that the photocatalytic performance of semiconductors is not governed by a single property, but by the synergistic optimization of band gap energy, charge carrier separation, and surface area. Doping and heterojunction engineering are powerful strategies for tailoring band structures and suppressing charge recombination, as evidenced by the exceptional performance of Z-scheme systems. Meanwhile, materials like MOFs leverage immense surface areas to maximize reactant contact. Researchers should therefore prioritize synthetic pathways that simultaneously address these interconnected properties. Future advancements will likely focus on designing more sophisticated multi-component architectures and rigorously assessing the long-term stability and potential environmental impact of the photocatalysts themselves [8] to bridge the gap between laboratory innovation and practical water treatment applications.

The escalating crisis of water pollution, driven by industrial organic dyes and antibiotics, has necessitated the development of advanced remediation technologies. Among these, photocatalytic oxidation has emerged as a highly promising solution due to its environmental friendliness, high efficiency, and ability to utilize solar energy for completely degrading pollutants into non-toxic small molecules [13] [14]. This technology operates on the principle that photocatalysts, upon light irradiation, generate electron-hole pairs that subsequently react with water and dissolved oxygen to produce reactive species capable of oxidizing organic pollutants. Inorganic semiconductor materials form the backbone of this technology, with metal oxides and oxyhalides such as ZnO, TiO₂, and BiOBr being particularly prominent. These semiconductors possess distinct electronic band structures that determine their light absorption capabilities and photocatalytic efficiency. The ongoing research in this field focuses on overcoming the inherent limitations of these materials, including their restricted visible light absorption and the rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, through various modification strategies such as heterojunction construction, elemental doping, and defect engineering [13] [15]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of prominent inorganic semiconductors, highlighting their intrinsic characteristics and performance in pollutant degradation applications.

Comparative Analysis of Key Semiconductor Properties

Table 1: Intrinsic characteristics of prominent inorganic semiconductors for pollutant degradation.

| Semiconductor | Crystal Structure | Band Gap (eV) | Primary Radiation Absorption | Key Advantages | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | Wurtzite-type hexagonal [16] | 3.16 - 3.37 [16] [14] | Ultraviolet [13] | High electron mobility, favorable adsorption properties, non-toxic [14] | Rapid electron-hole recombination, limited visible light response [13] |

| TiO₂ | Information Missing | Information Missing | Ultraviolet [13] | Low cost, widely studied [13] | Low electron-hole separation rate, only excited by ultraviolet light [13] |

| BiOBr | Tetragonal [13] | 2.64 [13] | Visible Light [13] | Suitable band gap for visible light, stable chemical properties [13] | Performance can be limited without modification [13] |

| BiOCl | Tetragonal [13] | 3.22 - 3.50 [13] | Ultraviolet [13] | Stable chemical properties | Largest band gap, primarily absorbs ultraviolet light [13] |

| BiOI | Tetragonal [13] | 1.77 [13] | Visible Light [13] | Small band gap, good visible light absorption | Information Missing |

Table 2: Performance comparison of semiconductors and their modified forms in degrading specific pollutants.

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Experimental Conditions | Degradation Efficiency | Kinetics (Rate Constant) | Key Modification Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO-ETG [16] | Reactive Black-5 (RB5) | UV light (365 nm) | Highest efficiency among capped ZnO samples [16] | Information Missing | Sonochemical synthesis with Ethylene Glycol capping agent [16] |

| Ag/ZnO [17] | Levofloxacin | UV irradiation, 1 g/L catalyst | 99% removal [17] | Higher rate constant than Ag/TiO₂ [17] | Ag deposition (5 wt%) [17] |

| Ag/TiO₂ [17] | Levofloxacin | UV irradiation, 1 g/L catalyst | 91% removal [17] | Lower rate constant than Ag/ZnO [17] | Ag deposition (5 wt%) [17] |

| Ag/ZnO [17] | Levofloxacin | Visible light, 1 g/L catalyst | 56% removal [17] | Information Missing | Ag deposition (5 wt%) [17] |

| Ag/TiO₂ [17] | Levofloxacin | Visible light, 1 g/L catalyst | 49% removal [17] | Information Missing | Ag deposition (5 wt%) [17] |

| Plasma-BiOBr/ZnO [13] | Methyl Orange (MO) | Visible light irradiation | Obvious improvement vs. unmodified samples [13] | Information Missing | H₂/Ar low-temperature plasma treatment [13] |

| 7% ZnO-QDs/CNHS [14] | Tetracycline (TC) | 15 minutes of irradiation | 80.2% removal [14] | Information Missing | S-scheme heterojunction with hollow-sphere g-C₃N₄ [14] |

Detailed Semiconductor Profiles and Experimental Protocols

Zinc Oxide (ZnO)

ZnO is an n-type semiconductor with a wurtzite-type hexagonal crystal structure [16]. It possesses a band gap typically ranging from 3.16 to 3.37 eV, which confines its primary absorption to the UV region of the electromagnetic spectrum [16] [14]. Despite this limitation, ZnO remains a promising photocatalyst due to its favorable adsorption properties, high electron mobility, and non-toxic nature [14].

Synthesis and Modification Protocols:

- Sonochemical Synthesis with Organic Capping Agents: Nanoparticles can be synthesized by dissolving zinc nitrate hexahydrate in ethanol, followed by ultrasonication. A sodium hydroxide solution (4 M) is added dropwise to precipitate ZnO. Organic modifiers like citric acid (CA), ethylene glycol (ETG), oleic acid (OA), and poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) can be added at a Zn/surfactant molar ratio of 0.05 to control morphology, particle size, and optical properties. The resulting precipitate is washed, dried, and heat-treated at 350°C for 2 hours [16].

- Silver Deposition: Ag/ZnO composites are prepared via photodeposition, with a typical nominal Ag loading of 5 wt%. This deposition effectively prevents the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, enhancing performance under both UV and visible light [17].

- Formation of Quantum Dots (QDs) for S-Scheme Heterojunctions: ZnO QDs can be coupled with other semiconductors like hollow-sphere g-C₃N4 (CNHS) to create S-scheme heterojunctions. These structures enhance charge separation and photocatalytic activity, as demonstrated by a 7% ZnO-QDs/CNHS composite achieving 80.2% tetracycline removal within 15 minutes [14].

Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂)

TiO₂ is one of the most extensively studied photocatalysts, known for its low cost and high electron mobility. However, its large band gap restricts its activity to UV light, and it suffers from a low electron-hole separation rate [13]. Modification strategies, such as deposition of Ag nanoparticles, are employed to enhance its visible light activity and overall performance [17].

Performance Comparison Protocol: A direct comparative study of Ag/ZnO and Ag/TiO₂ for levofloxacin degradation under identical conditions revealed that both materials achieved high removal rates under UV irradiation (99% and 91%, respectively). However, their efficiency dropped under visible light, with Ag/ZnO (56%) outperforming Ag/TiO₂ (49%). The kinetic rate constant of ZnO-based photocatalysts was consistently higher than that of TiO₂-based samples across all conditions [17].

Bismuth Oxybromide (BiOBr)

BiOBr is a p-type semiconductor with a tetragonal crystal structure and a band gap of approximately 2.64 eV, making it responsive to visible light [13]. Its stable chemical properties and suitable band gap have generated significant research interest.

Synthesis and Plasma Modification Protocol:

- Hydrothermal Synthesis: BiOBr and BiOBr/ZnO heterostructures can be synthesized via a simple hydrothermal method. This process typically results in a three-dimensional flower-like structure for pure BiOBr and layered ultrathin nanosheets for the BiOBr/ZnO composite [13].

- Plasma Treatment: The synthesized materials can be further modified with a short-time (pulsed mode) low-temperature plasma treatment using a gas mixture of argon and 3% hydrogen. This process, conducted at a discharge power of 100 W, generates surface defects without altering the basic morphology. These defects enhance the photogenerated carrier separation rate and narrow the band gap, leading to significantly improved photocatalytic activity [13].

Engineering Oxygen Vacancies in Heterostructures

The strategic creation of oxygen vacancies is a powerful method for enhancing semiconductor performance. For instance, sheet-like triangular Bi₂O₃ synthesized via hydrothermal method and annealed in a hydrogen-containing atmosphere effectively introduces oxygen vacancies. Similarly, sputtering ZnO at elevated substrate temperatures also facilitates oxygen vacancy formation. In a Bi₂O₃/ZnO composite, these vacancies significantly enhance charge separation, leading to increased photocurrent density and reduced interfacial resistance in photoelectrochemical applications [15]. Control over annealing conditions and substrate temperatures is crucial for optimizing oxygen vacancy generation [15].

Mechanisms and Workflows

Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism

The degradation of pollutants primarily involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). A key mechanism identified in advanced systems, such as the ZnO-QDs/CNHS S-scheme heterojunction, highlights singlet oxygen (¹O₂) as a primary active species. In this mechanism, photogenerated holes (h⁺) and superoxide radicals (•O₂⁻) combine to produce ¹O₂, which accounts for a major proportion (e.g., 83.28%) of the degradation activity due to its electrophilic nature that rapidly oxidizes the electron-rich parts of organic pollutants [14].

Diagram 1: Simplified photocatalytic pollutant degradation pathway.

Experimental Workflow for Catalyst Preparation and Testing

A standard methodology for developing and evaluating novel photocatalysts involves synthesis, modification, and performance testing, as exemplified by the development of Plasma-BiOBr/ZnO [13] and capped ZnO nanoparticles [16].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for photocatalyst development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents and materials used in the synthesis and testing of inorganic semiconductors.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate | ZnO precursor in synthesis | Source of Zn²⁺ ions in sonochemical and hydrothermal synthesis [16] |

| Bismuth Nitrate Pentahydrate | BiOBr precursor in synthesis | Source of Bi³⁺ ions in hydrothermal synthesis of BiOBr [13] |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Halogen source in synthesis | Provides Br⁻ ions for the formation of BiOBr crystal structure [13] |

| Ethylene Glycol (ETG) | Capping agent / Solvent | Organic modifier controlling ZnO crystal size, morphology, and optical properties [16] |

| Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) | Capping agent / Stabilizer | Controls particle growth and prevents agglomeration during nanoparticle synthesis [16] |

| Citric Acid (CA) | Capping agent / Chelating agent | Modifies surface properties and can act as a carbon source in composite materials [16] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Capping agent | Influences crystal growth and extends light absorption into the visible region [16] |

| Silver Nitrate | Precursor for dopant/modifier | Source of Ag⁺ for depositing Ag nanoparticles on ZnO/TiO₂ to enhance activity [17] |

| Methyl Orange (MO) | Model organic pollutant | Azo dye used to evaluate photocatalytic degradation efficiency [13] |

| Reactive Black 5 (RB5) | Model organic pollutant | Azo dye used for photocatalytic performance tests under varying pH [16] |

| Tetracycline (TC) | Model antibiotic pollutant | Antibiotic compound used to evaluate degradation mechanisms and efficiency [14] |

| Levofloxacin | Model antibiotic pollutant | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic used in comparative photocatalytic studies [17] |

This comparative analysis elucidates the intrinsic characteristics and modified performances of prominent inorganic semiconductors in the realm of photocatalytic pollutant degradation. While ZnO and TiO₂ offer the benefits of stability and established synthesis protocols, their wide bandgaps limit their solar efficiency. BiOBr, with its visible-light-responsive band gap, presents a compelling alternative. The experimental data consistently demonstrates that performance is profoundly enhanced not merely by the choice of base material, but through strategic modifications such as heterojunction formation (e.g., BiOBr/ZnO, ZnO/CNHS), elemental deposition (e.g., Ag), surface defect engineering via plasma treatment, and morphology control using organic capping agents. The selection of an optimal photocatalyst is thus highly application-specific, dependent on the target pollutant and the available light source. Future research directions will likely continue to refine these modification techniques, with a growing emphasis on understanding complex degradation mechanisms involving non-radical pathways and designing robust, Z-scheme heterostructures for superior charge separation and overall photocatalytic performance.

Comparative Study of Inorganic Semiconductors for Pollutant Degradation Research

Semiconductor-based photocatalysis has emerged as a promising advanced oxidation process (AOP) for degrading recalcitrant organic pollutants in wastewater, including textile dyes and pharmaceutical compounds [18] [19]. This technology utilizes light-activated semiconductor materials to generate highly reactive species that can mineralize persistent contaminants into harmless byproducts such as carbon dioxide and water [18]. The effectiveness of these photocatalytic processes depends on multiple factors including the semiconductor's composition, morphology, crystallinity, bandgap energy, and surface characteristics, as well as operational conditions like pH, contaminant concentration, and light intensity [18] [20].

The widespread presence of organic dyes from textile manufacturing and pharmaceutical compounds in water systems represents a significant environmental challenge worldwide [21] [19]. Textile dyes are particularly problematic as they do not bind tightly to fabrics and are often discharged as effluent into aquatic environments, where even minute concentrations (<1 ppm) are clearly visible and can be toxic to aquatic organisms [21] [20]. Similarly, pharmaceutical pollutants including antiviral drugs have seen substantially increased prevalence, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, and their hydrophilic nature leads to low degradation efficiency in conventional wastewater treatment plants [22].

Semiconductor Photocatalysts: Mechanisms and Performance Comparison

Fundamental Photocatalytic Mechanisms

The photocatalytic process begins when a semiconductor absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, promoting electrons from the valence band to the conduction band and creating electron-hole pairs [18] [20]. These photoexcited charge carriers then migrate to the semiconductor surface where they participate in redox reactions with adsorbed species. The holes can oxidize water or hydroxide ions to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH), while electrons can reduce molecular oxygen to form superoxide anion radicals (•O₂⁻) [18]. These reactive oxygen species are primarily responsible for the degradation of organic pollutants through a series of oxidation reactions that ultimately lead to complete mineralization [18] [20].

The efficiency of photocatalytic reactions is governed by the semiconductor's ability to absorb light, separate and migrate charge carriers, and facilitate surface reactions [20]. Conventional semiconductors like TiO₂ have limited response to visible light and suffer from rapid recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, which has prompted research into modified and composite materials [18]. Recent advancements have focused on addressing these challenges through techniques such as surface modification, doping, and the development of Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions [18].

Comparative Performance of Semiconductor Photocatalysts

Table 1: Comparison of Semiconductor Photocatalysts for Pollutant Degradation

| Photocatalyst | Bandgap Energy (eV) | Primary Reactive Species | Optimal pH Range | Degradation Efficiency | Target Pollutants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | 3.0-3.2 | •OH, •O₂⁻ | Acidic to neutral | ~99% for various dyes [20] | Textile dyes, pharmaceuticals |

| ZnO | ~3.37 | •OH, •O₂⁻ | Neutral to basic | 90% Congo red [23] | Azo dyes, organic compounds |

| BiOBr | ~2.8 | pH-dependent: •O₂⁻ (acidic), h⁺/•OH (basic) [24] | Basic (pH 9-10) [24] | High discoloration at pH 9-10 [24] | Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B |

| g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 | •O₂⁻, h⁺ | Variable | Efficient for pharmaceuticals [18] | Emerging contaminants, drugs |

| CeO₂ | ~2.8-3.2 | •OH, •O₂⁻ | Acidic to neutral | Moderate to high [18] | Diverse organic pollutants |

| Heterojunctions | Tunable | Multiple species | Depends on components | Enhanced vs. single components [18] | Recalcitrant compounds |

Table 2: Operational Parameters and Their Impact on Photocatalytic Efficiency

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Effect on Photocatalysis | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Pollutant-dependent [24] [20] | Affects surface charge, aggregation, reactive species formation [24] | BiOBr: mechanism shifts from •O₂⁻ attack to h⁺ domination with increasing pH [24] |

| Catalyst Concentration | 0.5-2.0 g/L | Higher concentration increases active sites until light penetration limit | Excess catalyst causes shading effect [20] |

| Initial Pollutant Concentration | <50 mg/L for most dyes | Higher concentrations require longer treatment times | Degradation rate decreases due to competition for active sites [20] |

| Light Intensity | Up to saturation point | Increases electron-hole pair generation | Varies with catalyst and reactor design [18] |

| Reaction Temperature | 20-80°C | Enhances reaction kinetics and mass transfer | Excessive temperature promotes recombination [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Photocatalytic Degradation Studies

Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization

Hydrothermal Synthesis of BiOBr Faceted Particles [24]: A representative synthesis involves mixing 0.975 g Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O with 50 mL deionized water containing 0.238 g KBr. The resulting mixture is transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-sealed stainless steel autoclave and maintained at 120°C for 24 hours before cooling to room temperature. The precipitate is centrifuged and washed several times with ethanol and deionized water, then dried at 60°C in air. The resulting rectangular-shaped BiOBr particles (approximately 2 μm in width) with dominant {001} facets are characterized using XRD, SEM, TEM, and AFM to confirm structure and surface properties [24].

Photocatalytic Reactor Setup [25]: A typical batch photocatalytic reactor system consists of a quartz glass reactor vessel (1 L volume) with two high-pressure mercury lamps (TQ 75 W each) mounted symmetrically around the reactor to ensure uniform radiation exposure. These lamps emit predominantly at 254 nm (UV-C range). The total UV power is typically 150 W, with an estimated radiation flux of approximately 2210 μW·s/cm². A magnetic stirrer ensures complete mixing of reactants during irradiation. All experiments are conducted at ambient temperature (25 ± 2°C), monitored using a digital thermometer [25].

Photocatalytic Degradation Procedure

A standard experimental procedure involves the following steps [24] [25]:

Reaction Mixture Preparation: The pollutant solution (e.g., methylene blue or rhodamine B at 10-20 mg/L concentration) is prepared in deionized water. The photocatalyst (typically 0.5-1.5 g/L) is dispersed in the solution.

pH Adjustment: The solution pH is adjusted using sulfuric acid or sodium hydroxide to the desired value (e.g., pH 3, 6, or 9 for mechanistic studies with BiOBr) [24].

Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Prior to irradiation, the suspension is stirred in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

Photocatalytic Reaction: The reaction is initiated by switching on the UV lamps. Samples (2-5 mL) are withdrawn at regular time intervals.

Sample Analysis: Withdrawn samples are centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and the supernatant is analyzed using UV-Vis spectrophotometry (for dye discoloration) or TOC analysis (for mineralization assessment).

Advanced Oxidation Processes Comparative Protocol

For comparative studies of different AOPs, the following experimental approach is recommended [25]:

Wastewater Collection: Real industrial wastewater (e.g., from cosmetics manufacturing) is collected and characterized for COD, BOD₅, pH, and specific contaminants.

Process Comparison: Multiple AOPs including UV photolysis, UV/H₂O₂, Photo-Fenton, and Photo-Fenton-like systems are evaluated under identical conditions.

Parameter Optimization: Key operational parameters (pH, oxidant dosage, catalyst concentration, irradiation time) are systematically varied to identify optimal conditions for each process.

Kinetic Analysis: Pseudo-first-order rate constants are determined for each process to compare degradation rates.

Biodegradability Assessment: The biodegradability index (BOD₅/COD) is measured before and after treatment to evaluate process effectiveness in enhancing subsequent biological treatability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Photocatalytic Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Catalysts | Light absorption, electron-hole generation | TiO₂ (Degussa P-25), ZnO, BiOBr, g-C₃N₄ | Purity >99%, specific surface area >50 m²/g [18] [24] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Additional oxidant, •OH radical source | 30% concentration, density 1.15 g/cm³ [25] | Optimize dosage to avoid scavenging effect [25] |

| Iron Salts | Fenton catalyst | FeSO₄·7H₂O (99% purity), FeCl₃·6H₂O (99% purity) [25] | Used in Photo-Fenton processes at 0.5-1 g/L [25] |

| pH Adjusters | Solution pH control | H₂SO₄ (95-97%), NaOH (48%) [25] | Critical for surface charge and mechanism [24] |

| Radical Scavengers | Mechanism elucidation | Methanol, tert-butanol, EDTA, benzoquinone [24] | Identify primary reactive species [24] |

| Target Pollutants | Model contaminants | Methylene Blue, Rhodamine B, pharmaceuticals | Typical concentration 10-50 mg/L for dyes [24] [20] |

Performance Evaluation and Kinetic Modeling

Degradation Efficiency and Kinetic Analysis

Photocatalytic degradation typically follows pseudo-first-order kinetics described by the equation: -ln(C/C₀) = kt, where C₀ and C are the initial and reaction concentrations, respectively, k is the apparent rate constant, and t is the irradiation time [25] [20]. The degradation efficiency is calculated as: Efficiency (%) = [(C₀ - C)/C₀] × 100.

For BiOBr photocatalysis, degradation rates for methylene blue and rhodamine B are strongly favored under basic conditions (pH 9-10), with the mechanism shifting from electron-induced •O₂⁻ attack at low pH to hole-dominated oxidation at high pH [24]. This pH-dependent behavior correlates with changes in surface charge of the {001} facet from slightly positive at acidic pH to significantly negative at basic pH, as determined by AFM analysis [24].

In comparative studies of AOPs for cosmetic wastewater treatment, the Photo-Fenton system demonstrated the highest performance, achieving 95.5% COD removal under optimized conditions (pH 3, 0.75 g/L Fe²⁺, 1 mL/L H₂O₂, 40 min irradiation) [25]. This process also enhanced the biodegradability index (BOD₅/COD) from 0.28 to 0.8, significantly improving the potential for subsequent biological treatment [25].

Semiconductor Modification Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Recent research has focused on addressing limitations of conventional semiconductors through various modification strategies:

Doping: Introducing metal or non-metal elements into semiconductor lattices to reduce bandgap energy and enhance visible light absorption [18] [20].

Heterojunction Construction: Combining two or more semiconductors with matched band structures to facilitate charge separation and reduce recombination [18]. Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions have shown particular promise for maintaining strong redox capabilities while enhancing charge separation efficiency [18].

Surface Modification: Engineering surface properties to enhance adsorption of target pollutants and increase active sites for photocatalytic reactions [18] [24].

Morphology Control: Synthesizing materials with specific facets, porous structures, or nanoscale dimensions to increase surface area and improve charge carrier migration [24].

Semiconductor photocatalysis represents a promising technology for addressing the challenge of recalcitrant organic pollutants in wastewater, particularly textile dyes and pharmaceutical compounds. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that material selection, operational parameters, and process optimization significantly impact degradation efficiency.

Future research should focus on developing visible-light-responsive photocatalysts with enhanced quantum efficiency, improved charge separation, and tailored surface properties for specific pollutant classes. The integration of photocatalytic processes with biological treatment systems and the development of scalable reactor designs will be crucial for practical implementation. Additionally, advanced characterization techniques and theoretical modeling will provide deeper insights into reaction mechanisms and material behavior, guiding the rational design of next-generation photocatalysts for environmental remediation.

Synthesis Techniques and Application Performance in Real-World Matrices

The synthesis method of a nanomaterial profoundly influences its fundamental characteristics, including its morphology, crystal structure, surface area, and defect chemistry, which in turn dictate its performance in applications such as photocatalytic pollutant degradation. For researchers and scientists developing advanced materials for environmental remediation, selecting an appropriate synthesis technique is a critical first step that involves balancing control over material properties with practical considerations of scalability, cost, and environmental impact. This comparative guide provides an objective analysis of five prominent synthesis methods—sol-gel, hydrothermal, electrodeposition, flame spray, and biological synthesis—within the specific context of producing inorganic semiconductors for pollutant degradation. The evaluation is based on experimental data from recent literature, with the aim of offering a scientific foundation for method selection in research and development settings.

The table below provides a high-level overview of the five synthesis methods, highlighting their core principles, common material outputs, and key comparative advantages and disadvantages.

Table 1: Overview of Featured Nanomaterial Synthesis Methods

| Synthesis Method | Fundamental Principle | Typical Materials Synthesized | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sol-Gel | Polycondensation of molecular precursors in a liquid solution to form a colloidal suspension (sol) that evolves into a solid network (gel). | Metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂, ZnO, SiO₂), mixed oxides, and organic-inorganic hybrids. | Low processing temperature, high product purity, excellent compositional control, and ability to produce thin films and aerogels [26]. | Long processing times, significant shrinkage during drying, and potential for crack formation in films. |

| Hydrothermal | Crystallization of materials from aqueous solutions in a sealed vessel (autoclave) at elevated temperature and pressure. | ZnO nanostructures (rods, wires, belts), perovskite microspheres (e.g., LaAlO₃), LiFePO₄ for batteries [27]. | Direct crystallization without calcination, high product crystallinity, and exceptional control over particle morphology and size [27]. | Requires high-pressure equipment, difficult to monitor reactions in situ, and typically small batch volumes. |

| Electrodeposition | Electrochemical reduction of metal ions from an electrolyte solution onto a conductive substrate to form a coating or free-standing structure. | Metal films (e.g., Bi, Sn), alloys, metal oxides, and nanowire arrays (e.g., Cu-Au) [28]. | Simple apparatus, rapid deposition, strong adhesion to substrates, and precise control over film thickness and morphology via potential/current [28]. | Limited to conductive substrates, potential for inhomogeneous deposition on complex geometries, and requires specific electrolyte compositions. |

| Flame Spray Pyrolysis (FSP) | Combustion of a precursor solution in a flame, involving evaporation, nucleation, and aggregation to form nanoparticles [29]. | Simple and complex metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂, SiO₂, LaCoO₃), non-precious metal catalysts [29] [30]. | Ultra-rapid, single-step continuous process, suitable for high-volume production, and enables in-situ doping and formation of complex oxides [29] [30]. | High energy consumption, requires precise control of numerous parameters (e.g., equivalence ratio, temperature), and particles may exhibit agglomeration [29]. |

| Biological Synthesis | Use of biological agents (plant extracts, bacteria, fungi) to reduce metal ions and form nanoparticles through metabolic processes [31]. | Precious metal nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Pt, Pd), metal oxides [31]. | Environmentally benign, uses sustainable resources, operates at near-ambient conditions, and often produces biocompatible nanoparticles [31]. | Challenges in controlling particle size and shape uniformly, limited scalability, and complex purification from biological debris. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Flame Spray Pyrolysis (FSP)

Principle: FSP involves the combustion of a liquid precursor solution, which is atomized and injected into a flame. The precursors undergo rapid evaporation, nucleation, and aggregation at high temperatures (typically >1500°C), resulting in the formation of nanoscale particles [29].

Experimental Protocol (as for synthesis of ZnO-Ag composites [32]):

- Precursor Preparation: A precursor solution is prepared by dissolving zinc-based and silver-based compounds (e.g., acetates or nitrates) in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol or an organic mixture) to achieve the desired metal stoichiometry.

- Atomization and Combustion: The precursor solution is atomized using oxygen as a carrier gas and fed into a flame burner, typically fueled by a mixture of methane or liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and oxygen.

- Reaction and Quenching: In the flame, the solvent evaporates, and the metal precursors decompose and oxidize to form nanoparticles. The process is rapid, occurring on a millisecond timescale. The resulting particles are rapidly quenched by entrainment of cool gas or by expansion.

- Collection: The synthesized nanoparticles are collected on a filter substrate placed above the flame [29] [32]. Key Parameters: Precursor composition and concentration, flame temperature, gas flow rates, and residence time in the hot zone [29].

Hydrothermal Synthesis

Principle: This method utilizes water as a solvent under high pressure and temperature in a sealed autoclave to facilitate the dissolution and recrystallization of materials that are normally insoluble under ambient conditions [27].

Experimental Protocol (as for synthesis of ZnO nanorods [27]):

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Two separate solutions are prepared. Solution A is prepared by dissolving a zinc salt (e.g., zinc acetate dehydrate) in distilled water or methanol. Solution B is an aqueous solution of a mineralizer (e.g., sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide).

- Mixing and Loading: The two solutions are mixed under stirring or ultrasonication to form a homogeneous suspension. The resultant mixture is transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, filling it to a specified capacity (e.g., 70-80%).

- Heating and Crystallization: The sealed autoclave is placed in an oven and heated to a specific temperature (e.g., 60°C to 220°C) for a prolonged period (e.g., 5 to 21 hours). The elevated temperature and autogenous pressure promote nucleation and crystal growth.

- Product Recovery: After the reaction is complete and the autoclave has cooled to room temperature, the precipitate is collected via centrifugation or filtration. The final product is obtained by washing the precipitate with water and ethanol and drying it in an oven [27]. Key Parameters: Reaction temperature and time, precursor concentration, pH of the solution, and the type of mineralizer used.

Electrodeposition

Principle: Electrodeposition is an electrochemical process where metal cations in an electrolyte solution are reduced and deposited as a solid layer onto a conductive substrate (the working electrode) when an electric potential is applied [28].

Experimental Protocol (as for synthesis of nano-dendrite copper [28]):

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: A standard three-electrode system is used, comprising a working electrode (e.g., Cu foil, Ag foil), a counter electrode (e.g., platinum mesh), and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl).

- Electrolyte Preparation: An electrolyte solution is prepared, typically containing a salt of the metal to be deposited (e.g., 0.05 M CuSO₄).

- Deposition: A constant potential (e.g., -1.25 V vs. RHE) or constant current is applied to the working electrode for a specific duration. This drives the reduction of metal ions (e.g., Cu²⁺) onto the substrate's surface.

- Post-treatment: After deposition, the electrode is removed from the electrolyte, thoroughly rinsed with deionized water, and dried [28]. Key Parameters: Applied potential/current density, deposition time, electrolyte composition, pH, and temperature.

Biological Synthesis

Principle: This method leverages the natural reducing and capping agents found in biological systems (e.g., enzymes, proteins, and phytochemicals) to convert metal ions into stable nanoparticles [31].

Experimental Protocol (as for synthesis of gold nanoparticles using mushroom extract [31]):

- Extract Preparation: The biological agent, such as fruiting bodies of the Enoki mushroom (Flammulina velutipes), is washed, dried, and ground. The biomass is then boiled in water to extract the water-soluble compounds.

- Reaction: The aqueous extract is mixed with a solution of the metal salt (e.g., chloroauric acid, HAuCl₄). The mixture is incubated at room temperature or a slightly elevated temperature for a period (e.g., several hours).

- Reduction and Formation: The biomolecules in the extract reduce the metal ions from their ionic form to zero-valent atoms, which then nucleate and grow into nanoparticles. A color change in the reaction mixture often visually indicates nanoparticle formation.

- Purification: The synthesized nanoparticles are recovered by repeated centrifugation and re-dispersion in clean solvent [31]. Key Parameters: Type and part of the biological source, extraction conditions, metal salt concentration, reaction temperature, pH, and time.

Comparative Performance in Pollutant Degradation

The efficacy of nanomaterials synthesized via different methods is most critically evaluated through their performance in degrading pollutants. The following table summarizes experimental data from studies that tested catalysts for dye degradation.

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Photocatalytic Dye Degradation

| Synthesis Method | Photocatalyst Material | Target Pollutant | Experimental Conditions | Performance Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame Spray Pyrolysis | ZnO-Ag composite | Methylene Blue (MB) | UV light, 75 min | 64% degradation | [32] |

| Spray Pyrolysis | ZnO-Ag composite | Methylene Blue (MB) | UV light, 75 min | Higher than FSP counterpart (exact % not stated) | [32] |

| Biological Synthesis | Au Nanoparticles (from F. velutipes) | Methylene Blue (MB) | 4 hours | 75.35% decolorization | [31] |

| Hydrothermal | AgBr/ZnO/RGO composite | Methyl Orange (MO) | Visible light | High degradation capacity (exact % not stated) | [27] |

The data indicates that both flame-synthesized and biologically-synthesized catalysts can achieve good degradation efficiency (>64%) for organic dyes like methylene blue. The study comparing flame and spray pyrolysis for ZnO-Ag synthesis is particularly insightful. While both methods produced materials with similar crystal structures and specific surface areas, the spray pyrolysis-derived particles exhibited a unique wrinkled morphology and a larger pore volume, which was credited with providing better access for dye molecules to active sites and consequently, superior photocatalytic performance [32]. This highlights that performance is not solely determined by the synthesis method, but by the specific morphological and structural properties it imparts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Typical Function in Synthesis | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts (Nitrates, Acetates, Chlorides) | Serve as the primary source of metal cations in the precursor solution. | Zinc acetate for ZnO nanorods (Hydrothermal) [27]; Metal acetylacetonates for FSP [29]. |

| Solvents (Water, Ethanol, Methanol) | Dissolve precursors to form a homogeneous solution or suspension. | Water as the solvent in Hydrothermal synthesis [27]; Ethanol/benzene mixtures in FSP [29]. |

| Mineralizers (NaOH, KOH) | Provide a alkaline medium to control hydrolysis and precipitation rates, and to direct crystal growth. | Used in Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO to control the formation of nanorods [27]. |

| Biological Extracts (Plant, Fungal, Bacterial) | Act as reducing and capping agents, facilitating the bioconversion of metal ions into stable nanoparticles. | Enoki mushroom extract for synthesizing Au nanoparticles [31]. |

| Structure-Directing Agents / Crosslinkers | Assist in forming desired porous structures and 3D networks in gels. | Crosslinkers for creating g-C₃N₅-based hydrogels [26]. |

| Gases (O₂, LPG, N₂) | Act as oxidizer (O₂), fuel (LPG), or inert carrier gas (N₂) in gas-phase synthesis. | Oxygen as oxidizer and carrier gas in FSP [29] [32]. |

Synthesis Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate synthesis method based on research priorities and constraints.

Diagram 1: A logical workflow to guide the selection of a nanomaterial synthesis method based on primary research requirements.

This comparative analysis demonstrates that no single synthesis method is universally superior; each offers a distinct set of advantages tailored to specific research and application needs. Flame spray pyrolysis stands out for its unmatched scalability and rapid, single-step production of complex oxides. Hydrothermal synthesis provides exceptional control over crystal morphology and size, yielding highly crystalline products. Electrodeposition is ideal for fabricating well-adhered films and structured electrodes for electrochemical systems. Biological synthesis represents the most environmentally sustainable route, operating under benign conditions. Finally, the sol-gel method offers versatile and precise compositional control for creating high-purity materials and complex gel networks.

The choice of technique must be guided by a clear alignment between the method's inherent strengths and the target application's performance requirements, particularly in the demanding field of photocatalytic pollutant degradation. Future advancements will likely involve the hybridization of these methods to create hierarchical structures that leverage the benefits of multiple techniques, ultimately leading to more efficient and tailored nanomaterials for environmental remediation.

The performance of a catalyst is intrinsically linked to its physical and chemical structure, which is, in turn, dictated by the parameters of its synthesis. For researchers developing advanced materials for environmental applications like pollutant degradation, understanding the link between synthesis and performance is crucial. This guide provides a comparative examination of how critical synthesis parameters—specifically solvents, temperature, and precursors—govern the morphology and activity of catalytic materials, with a focus on applications in photocatalytic degradation and hydrodesulfurization. The experimental data and protocols summarized herein offer a foundation for making informed decisions in catalytic design.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Parameters and Catalytic Performance

The following table synthesizes key experimental data from recent studies, demonstrating how deliberate manipulation of synthesis parameters directly influences catalyst characteristics and its efficiency.

Table 1: Impact of Synthesis Parameters on Catalyst Morphology and Activity

| Synthesis Parameter | Material System | Impact on Morphology & Structure | Catalytic Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal Temperature | SnO₂ Nanostructures | Formation of different morphologies (rods, spheres, flowers) controlled by temperature and time. | Flower-shaped SnO₂ showed higher photocatalytic activity for aniline derivative degradation. [33] | |

| Pre-activation Thermal Treatment | CoMoS/KIT-6 | Lower pre-treatment temperatures led to smaller, less stacked CoMoS crystals and a higher amount of the active CoMoS phase. [34] | HDS of DBT: Catalyst pre-treated at 135°C showed stable ~65% acetic acid conversion, 22% higher than those from higher temperatures. [34] | |

| Solvent Polarity | Zn(OAc)₂/Activated Carbon | Mixed solvent (water/ethanol) reduced active component particle size from 33.08 nm to 15.30 nm and increased BET surface area by 10%. [35] | Acetic acid conversion increased from ~43% (water solvent) to ~65% (mixed solvent), a 22% enhancement in activity. [35] | |

| Reactant Concentration (Solvent Volume) | Ni–NiO Nanocatalysts (SCS) | Changing the water volume in the precursor solution modified the nanomaterial's microstructure and crystallite size. [36] | Changes in surface chemical composition and active sites were linked to catalytic activity for hydrogenation. [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for research, this section outlines the key methodologies cited in the comparison table.

Protocol for Morphology-Controlled Hydrothermal Synthesis of SnO₂

This protocol is adapted from the work on synthesizing SnO₂ nanostructures with varying morphologies for photocatalytic applications. [33]

- Key Reagents: Stannic chloride pentahydrate (SnCl₄·5H₂O), Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH), De-ionized water, Absolute Ethanol.

- Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Mix SnCl₄·5H₂O and 1.4 g NaOH with 40 mL de-ionized water under magnetic stirring for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation: Slowly add 40 mL of absolute ethanol to the solution to form a white precipitate. Continue stirring this mixture for 24 hours.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the entire mixture into a 150 mL Teflon-lined autoclave. Seal the autoclave and place it in an oven.

- Parameter Variation: React at different temperatures within the range of 170–190 °C and for different periods ranging from 4 to 48 hours.

- Product Recovery: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool naturally to room temperature. Collect the resulting precipitate, wash it thoroughly with de-ionized water and ethanol, and dry it in an oven.

- Characterization: The synthesized SnO₂ nanoparticles were characterized by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), UV–vis spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and adsorption isotherm measurement. [33]

- Activity Testing: The photocatalytic activity was evaluated by monitoring the degradation of model organic pollutants (aniline, 4-nitroaniline, 2,4-dinitroaniline) in aqueous solution under ultraviolet radiation. [33]

Protocol for Solvent-Optimized Impregnation on Activated Carbon

This protocol details the method for enhancing active phase dispersion on a non-polar support using a mixed solvent system. [35]

- Key Reagents: Activated Carbon (AC), Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Urea, Methanol, Ethanol, n-Propanol, Isopropanol, Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Solvent Preparation: Prepare mixed solvents by combining alcohols (e.g., methanol, ethanol, n-propanol, isopropanol) with deionized water at a typical ratio of 20 wt% alcohol to 80 wt% water.

- Impregnation: Weigh 1.00 g of coconut shell AC, 0.50 g urea, and 0.50 g Zn(NO₃)₂ into a beaker. Add 30 mL of the prepared mixed solvent (e.g., Mixed Solvent A: methanol-water).

- Mixing: Seal the beaker and stir the solution at 600 rpm for 12 hours at room temperature.

- Drying and Calcination: After impregnation, dry the sample overnight at 80°C in a blast drying oven. Subsequently, calcine the dried material at 800°C for 2 hours under an inert atmosphere (e.g., using a facile carbon bath method).

- Characterization: The catalysts were characterized by N₂ adsorption-desorption (BET method), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). [35]

- Activity Testing: Catalytic performance was evaluated in a fixed-bed reactor for the synthesis of vinyl acetate. The conversion of acetic acid was measured under set conditions (GHSVC₂H₂ = 500 h⁻¹, C₂H₂/CH₃COOH molar ratio = 3). [35]

Synthesis-Activity Relationships

The connection between synthesis parameters, resulting material properties, and final catalytic activity forms a critical pathway for rational catalyst design. The diagram below visualizes this fundamental relationship and the underlying mechanisms, as evidenced by the cited studies.

Diagram 1: The pathway from synthesis parameters to catalytic performance, illustrating how specific parameter changes influence material properties and ultimately determine activity metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting the appropriate reagents is fundamental to executing the described synthesis protocols and controlling the resulting catalyst properties. The following table lists key materials and their functions in catalyst preparation and characterization.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Synthesis and Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Catalysis Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SnCl₄·5H₂O | Metal precursor for the synthesis of SnO₂ nanostructures. [33] | Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants like anilines. [33] |

| Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | Source of zinc for the active site in supported catalysts. [35] | Catalyst for acetylene gas-phase synthesis of vinyl acetate. [35] |

| Cobalt & Molybdenum Salts | Precursors for creating the active CoMoS phase in hydrodesulfurization (HDS) catalysts. [34] | Removal of sulfur from fuel (e.g., HDS of dibenzothiophene). [34] |

| Glycine | Fuel used in Solution Combustion Synthesis (SCS) to produce nano-structured powders. [36] | Synthesis of Ni–NiO nanocatalysts. [36] |

| KIT-6, Activated Carbon | High-surface-area support materials to maximize active phase dispersion. [34] [35] | Providing a porous structure for anchoring catalytic active sites. [34] [35] |

| Teflon-lined Autoclave | Reaction vessel for hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis under autogenous pressure. [33] | Morphology-controlled synthesis of metal oxide nanostructures. [33] |

The direct correlation between synthesis parameters and catalytic efficacy is unequivocally demonstrated by the comparative data presented in this guide. Key takeaways for researchers include:

- Temperature Control: Lower thermal budgets during pre-activation or hydrothermal synthesis can favor smaller crystallites and more active morphologies, directly boosting conversion rates. [33] [34]

- Solvent Engineering: Matching solvent polarity to the support material is not a minor detail but a critical strategy. Using optimized mixed solvents can dramatically improve active phase dispersion and increase surface area, leading to significant gains in catalytic activity. [35]

- Precursor Manipulation: The concentration and type of precursors define the final microstructure of the catalyst, including its morphology and surface chemistry, which are key determinants of its performance and aging characteristics. [36]

This synthesis-activity relationship provides a powerful framework for the rational design of next-generation catalysts for environmental remediation and other advanced applications.

The evaluation of advanced oxidation processes, particularly photocatalytic degradation using inorganic semiconductors, relies on three fundamental performance metrics: degradation efficiency, reaction kinetics, and mineralization rates. These metrics provide researchers with critical insights into the effectiveness, speed, and completeness of pollutant removal. Degradation efficiency quantifies the percentage of a pollutant removed within a specific timeframe, offering a straightforward measure of catalyst effectiveness. Reaction kinetics describe the rate at which degradation occurs, providing essential parameters for reactor design and process scaling. Mineralization rate measures the complete conversion of organic pollutants to harmless inorganic compounds like CO₂ and H₂O, indicating the true environmental remediation potential by accounting for intermediate by-product formation.

Understanding these metrics is crucial for comparing novel semiconductor materials and moving toward practical environmental applications. This guide systematically compares these performance metrics across leading inorganic semiconductor photocatalysts, providing structured experimental data and methodologies to facilitate objective comparison for researchers and scientists in environmental remediation fields.

Comparative Performance Data of Semiconductor Photocatalysts

Table 1: Comparative degradation efficiency of various semiconductor photocatalysts for different pollutant classes

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Initial Concentration | Light Source | Time (min) | Degradation Efficiency (%) | Mineralization Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SbSeI | Cr(VI) | Not specified | Xe lamp | 10 | 98% | Not specified | [37] |

| SbSeI | RhB | Not specified | Xe lamp | 40 | 98% | Not specified | [37] |

| SbSeI | RhB/Cr(VI) mixture | Not specified | Xe lamp | 25 | 99% (Cr(VI)), 68.5% (RhB) | Not specified | [37] |

| Ni1.5/SnS₂ | Levofloxacin (High-salt) | Not specified | Piezoelectric | 90 | 94% | Not specified | [38] |

| Ni1.5/SnS₂ | Ciprofloxacin (High-salt) | Not specified | Piezoelectric | 90 | 99.6% | Not specified | [38] |

| Ni1.5/SnS₂ | Methyl Orange (High-salt) | Not specified | Piezoelectric | 90 | 68.4% | Not specified | [38] |

| (SnO₂)-Cu₂ZnSnS₄-TiO₂ | Methylene Blue | 10 ppm | Simulated solar (34 W/m²) | Not specified | 20-30% | Not specified | [39] |

| (SnO₂)-Cu₂ZnSnS₄-TiO₂ | Phenol | 10 ppm | Simulated solar (34 W/m²) | Not specified | 15-20% | Not specified | [39] |

| (SnO₂)-Cu₂ZnSnS₄-TiO₂ | Imidacloprid | 10 ppm | Simulated solar (34 W/m²) | Not specified | 10-12% | Not specified | [39] |

| Photo-Fenton | Cosmetic Wastewater (COD) | Real wastewater | UV-C (150 W) | 40 | 95.5% | BOD₅/COD: 0.28 to 0.8 | [25] |

Table 2: Reaction kinetics parameters reported for photocatalytic degradation processes

| Photocatalytic System | Target Pollutant | Optimal Kinetic Model | Rate Constant (k) | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂/ceramic supported | Rhodamine B | Pseudo-First-Order | k₁ (R²=0.9923) | Not specified | [40] |

| Mn-doped CuO | Ofloxacin | Pseudo-First-Order | k₁ (R²=0.9813) | Not specified | [40] |

| CdSe nanoparticles | Methylene Blue | Pseudo-First-Order | k₁ | Not specified | [40] |

| ZnO nanoparticles | Methylene Blue | Langmuir-Hinshelwood | K = 0.168 L mg⁻¹, kᵣ = 1.243 mg L⁻¹ min⁻¹ | Not specified | [40] |

| Activated Carbon/TiO₂ | Amoxicillin | Langmuir-Hinshelwood | Better fit than first-order | Not specified | [40] |

| Photo-Fenton | Cosmetic Wastewater | Pseudo-First-Order | Not specified | pH 3, 0.75 g/L Fe²⁺, 1 mL/L H₂O₂ | [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Metric Evaluation

Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization Protocols

Chemical Vapor Transport (CVT) for SbSeI Single Crystals: High-quality SbSeI crystals are prepared using the CVT method with antimony (99.979%), selenium (99.999%), and iodine (99.95%) as precursors. Stoichiometric amounts of pure elements are sealed in an evacuated quartz tube under vacuum (10⁻³ Pa) and heated in a two-zone furnace with a temperature gradient from 450°C to 350°C over 240 hours. The resulting needle-like crystals with metallic luster are exfoliated via liquid-phase exfoliation in deionized water for photocatalytic testing [37].

Hydrothermal Method for Ni/SnS₂: SnS₂ and Ni-doped SnS₂ (Ni/SnS₂) nano-flowers are synthesized via a facile hydrothermal approach. For typical Ni1.5/SnS₂ preparation, 0.5 mmol SnCl₄·5H₂O and 2 mmol thioacetamide are dissolved in 40 mL anhydrous ethanol and stirred for 20 minutes. Then, 0.15 mmol nickel acetylacetonate (Ni(acac)₂) is added with continued stirring for 10 minutes. The mixture is transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintained at 160°C for 12 hours. The resulting precipitate is collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and deionized water, and dried at 60°C for 12 hours [38].

Spray Pyrolysis Deposition for (SnO₂)-Cu₂ZnSnS₄-TiO₂ Thin Films: Multi-layered heterostructures are fabricated using sequential spray pyrolysis deposition. First, a SnO₂ layer is deposited from 0.045 M aqueous SnCl₄ solution onto heated glass substrates (350°C) using 20 spraying sequences with 15-second breaks. The films are annealed at 450°C for 3 hours to enhance crystallinity. Subsequently, CZTS thin films with atomic ratio Cu:Zn:Sn:S of 1.8:1.2:1:10 are deposited, followed by TiO₂ layers of varying thicknesses using 0.1 M titanium lactate solution in water [39].

Photocatalytic Degradation Testing Protocols

Pollutant Degradation Procedure: Standard photocatalytic tests are performed by dispersing the catalyst (typically 0.5-1.0 g/L) in an aqueous solution of the target pollutant (initial concentration 10-20 mg/L) under constant stirring. The suspension is stirred in darkness for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium before illumination. A Xe lamp (typically 300-500 W) simulates solar irradiation, with samples extracted at regular intervals, centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy to determine pollutant concentration [37] [39].

Analytical Methods for Mineralization Assessment: Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analysis provides the most direct measurement of mineralization by quantifying the remaining organic carbon in solution. Alternatively, the biodegradability index (BOD₅/COD) indicates mineralization potential, with values >0.3 suggesting improved biodegradability. Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) measures the oxygen equivalent of organic matter, with removal rates indicating mineralization extent. For example, Photo-Fenton treatment of cosmetic wastewater increased the BOD₅/COD ratio from 0.28 to 0.8, indicating enhanced biodegradability and partial mineralization [25].

Capture Experiments for Reactive Species Identification: To identify dominant reactive species, capture experiments are conducted using specific scavengers: ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA-2Na, 1 mM) for holes (h⁺), ascorbic acid (VC, 1 mM) for electrons (e⁻), isopropyl alcohol (IPA, 1 mM) for hydroxyl radicals (·OH), and p-benzoquinone (BQ, 1 mM) for superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻). Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin trap agent provides direct evidence of radical formation [37].