Building Robustness into Inorganic Analytical Methods: A QbD Framework for Reliable Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing robust inorganic analytical methods.

Building Robustness into Inorganic Analytical Methods: A QbD Framework for Reliable Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing robust inorganic analytical methods. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation, it details how to systematically assess a method's resilience to small, deliberate variations in parameters. Readers will learn to apply Quality by Design (QbD) and Design of Experiments (DoE) for efficient robustness testing, troubleshoot common issues, and successfully integrate robustness studies into method validation and transfer protocols to ensure data integrity and regulatory compliance.

What is Robustness Testing? Core Principles for Inorganic Analysis

Defining Robustness vs. Ruggedness in Analytical Chemistry

In inorganic analytical methods research, the reliability of your data is paramount. Two key concepts that underpin this reliability are robustness and ruggedness. These are critical validation parameters that ensure your method does not produce a result that is merely a snapshot of ideal, controlled conditions, but a reproducible truth that holds under the normal variations encountered in any laboratory [1]. Understanding and testing for both is a fundamental requirement for any method intended for regulatory submission or use in quality control.

▷ The Core Definitions: What Are They?

While sometimes used interchangeably in literature, a distinct and practical difference exists between robustness and ruggedness.

- Robustness is an intra-laboratory study that measures an analytical method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in its internal method parameters [1] [2]. It answers the question: "How well does my method withstand minor, intentional tweaks to the procedure I developed?"

- Ruggedness is a measure of the reproducibility of analytical results under a variety of real-world, external conditions, often involving inter-laboratory testing [1] [3]. It answers the question: "Will my method perform consistently when used by different analysts, on different instruments, or in different labs?"

The table below summarizes the key differences.

| Feature | Robustness Testing | Ruggedness Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To evaluate performance under small, deliberate parameter variations [1]. | To evaluate reproducibility under real-world, environmental variations [1]. |

| Scope | Intra-laboratory, during method development [1]. | Inter-laboratory, often for method transfer [1]. |

| Nature of Variations | Controlled changes to internal method parameters (e.g., pH, flow rate) [1] [2]. | Broader, external factors (e.g., different analyst, instrument, laboratory) [1] [3]. |

| Primary Goal | Identify critical parameters and establish controlled limits [1]. | Demonstrate method transferability and reproducibility [1]. |

▷ Visualizing the Relationship

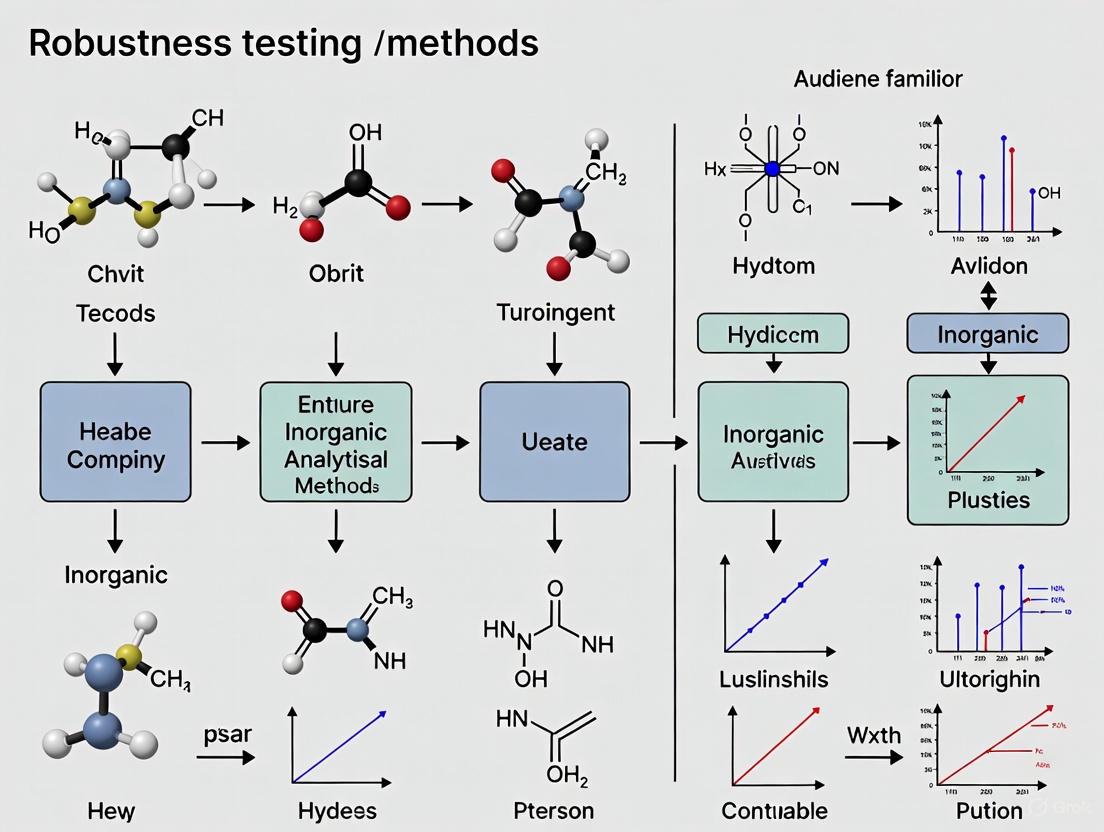

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these concepts and their place in the method lifecycle.

▷ The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Experimental Parameters

When planning robustness and ruggedness tests, you will focus on different sets of parameters. The following table details common factors investigated for each, which can be considered the essential "reagents" for your method validation experiments.

| Category | Specific Factors | Function & Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Robustness (Internal) | Mobile phase pH [1] [2] | Affects ionization, retention time, and peak shape of analytes. |

| Mobile phase composition [1] [2] | Small changes in solvent ratio can significantly alter separation and resolution. | |

| Flow rate [1] [2] | Impacts retention time, pressure, and can affect detection sensitivity. | |

| Column temperature [1] [2] | Influences retention, efficiency, and backpressure. | |

| Different column batches/suppliers [1] [2] | Tests method's susceptibility to variations in stationary phase chemistry. | |

| Ruggedness (External) | Different analysts [1] [3] | Evaluates the impact of human variation in sample prep, instrument operation, and data processing. |

| Different instruments [1] [3] | Assesses performance across different models, ages, or manufacturers of the same instrument type. | |

| Different laboratories [1] [3] | The ultimate test of transferability, accounting for environmental and operational differences. | |

| Different days [1] [3] | Checks for consistency over time, accounting for reagent degradation, ambient conditions, etc. |

▷ Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Guide: Common HPLC Issues Linked to Robustness

Problems during analysis can often be traced back to a lack of robustness in a specific parameter. Here is a guide to diagnose common issues.

| Symptom | Possible Cause (Lack of Robustness) | Investigation & Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Retention time drift | Poor temperature control; incorrect mobile phase composition; change in flow rate [4]. | Use a thermostat column oven; prepare fresh mobile phase; check and reset flow rate [4]. |

| Peak tailing | Wrong mobile phase pH; active sites on column; prolonged analyte retention [4]. | Adjust mobile phase pH; change to a different column; modify mobile phase composition [4]. |

| Baseline noise | Air bubbles in system; contaminated detector cell; leak [4]. | Degas mobile phase; purge system; clean or replace flow cell; check and tighten fittings [4]. |

| Split peaks | Contamination in system or sample; wrong mobile phase composition [4]. | Flush system with strong solvent; replace guard column; filter sample; prepare fresh mobile phase [4]. |

| Loss of resolution | Contaminated mobile phase or column; small variations in method parameters exceeding robust limits [4]. | Prepare new mobile phase; replace guard/analytical column; use robustness data to tighten control on critical parameters (e.g., pH) [1] [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When during method development should I perform a robustness test? It is best practice to perform robustness testing at the end of the method development phase or at the very beginning of method validation [1] [5]. This proactive approach identifies critical parameters early, allowing you to refine the method and establish control limits before significant resources are spent on full validation. Finding that a method is not robust late in the validation process can be costly and require redevelopment [5].

Q2: Is ruggedness testing required for all analytical methods? The requirement depends on the method's intended use. If the method will be transferred between laboratories, or used routinely in a multi-analyst environment, a ruggedness study is essential to prove its reproducibility [1]. For a method used exclusively in a single, controlled laboratory environment, extensive inter-laboratory ruggedness testing may not be necessary, though inter-analyst testing is still good practice.

Q3: How is robustness data used to set System Suitability Test (SST) limits? The ICH guidelines state that one consequence of robustness evaluation should be the establishment of system suitability parameters [5]. The results of a robustness test provide experimental evidence for setting appropriate SST limits [1] [5]. For example, if a robustness test shows that a 0.1 unit change in pH causes the resolution between two critical peaks to drop from 2.5 to 1.7, you can set a scientifically justified SST limit for resolution at, for instance, 2.0, rather than an arbitrary one.

Q4: What is the experimental design for a robustness test? Robustness tests typically use fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman experimental designs [5]. These are efficient, two-level screening designs that allow you to investigate a relatively large number of factors (e.g., 6-8 method parameters) in a minimal number of experiments. In this design, each factor is examined at a "high" and "low" level, slightly outside the expected normal operating range, to assess its effect on method responses like assay content, resolution, or tailing factor [5].

The Critical Role of Robustness in Method Lifecycle Management

FAQs on Robustness and Method Lifecycle Management

Q1: What is analytical method robustness and why is it critical? A1: Analytical method robustness is defined as the capacity of an analytical method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters and provide reliable, consistent results under typical operational conditions [6]. It is critical because it ensures that a method produces dependable data even when minor, inevitable changes occur in the laboratory environment, such as fluctuations in temperature, slight differences in reagent pH, or variations between analysts or instruments [6] [7]. A robust method reduces the risk of out-of-specification results, costly laboratory investigations, and product release delays, thereby forming the bedrock of data integrity in regulated environments [8] [9].

Q2: How does robustness fit within the broader Method Lifecycle Management (MLCM) framework? A2: Within Method Lifecycle Management (MLCM), robustness is not a one-time test but a core consideration integrated throughout the method's entire life [8] [10]. MLCM is a control strategy designed to ensure analytical methods perform as intended from development through long-term routine use [11]. Robustness is fundamentally built into the Method Design and Development stage using principles like Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) [10] [9]. Its verified during Method Performance Qualification (validation) and is continuously monitored during Continued Method Performance Verification in routine use [10] [9]. This lifecycle approach views method development, validation, transfer, and routine use as an interconnected continuum, with knowledge and risk management as key enablers for achieving and maintaining robustness [10].

Q3: What is the difference between robustness and ruggedness? A3: While sometimes used interchangeably, a key distinction exists:

- Robustness evaluates the method's resistance to small, deliberate changes in method parameters under an analyst's control, such as mobile phase pH, column temperature, or flow rate [6] [7].

- Ruggedness refers to the degree of reproducibility of test results under a variety of normal, real-world operational conditions, such as different laboratories, different analysts, different instruments, or different days [7]. In essence, robustness tests the method's inherent stability, while ruggedness tests its practical applicability across different environments [12] [7].

Q4: What are common instrumental factors that can affect method robustness in inorganic analysis? A4: For inorganic analytical techniques like ICP-MS or IC, critical factors impacting robustness include [13]:

- Sample Introduction System: Variations in peristaltic pump tubing, nebulizer pressure, and spray chamber temperature.

- Plasma Conditions: Fluctuations in RF power, plasma gas flow rates, and torch alignment.

- Interface Conditions: Changes in sampler and skimmer cone geometry and cleanliness.

- Detector Performance: Instrument drift and variations in detector voltage.

- Mobile Phase/Solvent Purity: Contamination or variability in high-purity reagents and gases, which is especially critical when dealing with emerging contaminants like PFAS or microplastics that can interfere with trace elemental testing [13].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Robustness Issues

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Shifts in Retention Time (Chromatography)

Problem: Inconsistent analyte retention times during HPLC or UHPLC analysis.

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Column Temperature | Check column oven set point and calibration. | Ensure the column thermostat is functioning correctly and use a pre-heater for all columns to avoid thermal mismatch [8]. |

| Fluctuations in Mobile Phase pH/Composition | Prepare fresh mobile phase from high-purity solvents and standardize buffer preparation. | Tighten standard operating procedures (SOPs) for mobile phase preparation and consider using an automated eluent screening system for consistency [8] [11]. |

| Mismatched Gradient Delay Volume (GDV) | Observe if retention time deviations occur during method transfer between instruments. | Utilize an LC system that allows fine-tuning of the GDV. This can be done by adjusting the autosampler's idle volume or by installing an optional method transfer kit to insert a defined volume loop [8]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Variable Sensitivity or Signal Drift (Spectroscopy)

Problem: Decreasing or drifting analytical signal in techniques like ICP-OES or UV-Vis.

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Contaminated or Degraded Sample Introduction Parts | Inspect nebulizer, torch, and cones (for MS) for wear or blockage. Check for potential emerging contaminants in solvents [13]. | Establish a routine maintenance and replacement schedule. Use high-purity, contamination-free reagents and reference materials [13]. |

| Instrument Calibration Drift | Run calibration verification standards and system suitability tests. | Implement more frequent instrument calibration and adhere to a robust calibration schedule. Use internal standards to correct for drift [14]. |

| Environmental Factors | Monitor laboratory temperature and humidity logs. | Ensure instruments are operated within manufacturer-specified environmental conditions. Use environmental control systems if necessary [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robustness Testing

Protocol 1: Robustness Evaluation Using a Plackett-Burman Experimental Design

The Plackett-Burman design is a highly efficient, fractional factorial design highly recommended for robustness studies when the number of factors to be evaluated is high [12]. It is ideal for screening which factors have a significant effect on method performance with a minimal number of experimental runs.

1. Objective: To identify critical method parameters that significantly impact the performance of an analytical method by simultaneously varying multiple factors.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Standard of the analyte of interest.

- Appropriate reagents and solvents as per the method.

- Analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC, ICP-MS) calibrated as per SOP.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Select Factors and Ranges: Choose the method parameters (e.g., flow rate, pH, column temperature, % organic solvent) and define a realistic, small variation for each (e.g., flow rate: 1.0 mL/min ± 0.05 mL/min) [6].

- Step 2: Select a Design: Choose a Plackett-Burman design matrix that can accommodate the number of factors you wish to study. These designs are available in statistical software packages.

- Step 3: Execute Experiments: Run the experiments in the randomized order prescribed by the design matrix. For each run, measure the predefined Critical Method Attributes (CMAs) such as resolution, retention time, peak area, tailing factor, etc. [12].

- Step 4: Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical analysis (e.g., multiple linear regression, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)) on the data to identify which factors have a statistically significant effect on the CMAs [12].

4. Data Interpretation: A factor is considered to have a significant effect on the method's robustness if the p-value from the statistical analysis is below a predefined significance level (typically p < 0.05). Parameters with high significance are deemed critical and must be tightly controlled in the final method procedure [12].

Protocol 2: AQbD-Based Approach for Robust Method Development

This protocol uses Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles to build robustness directly into the method during the development stage [10] [9].

1. Objective: To develop a robust analytical method by systematically understanding the relationship between method parameters and performance attributes, and defining a controlled "method operable design region" (MODR).

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP): The ATP is a pre-defined objective that summarizes the method's requirements, such as accuracy, precision, and detection limits, based on the product's Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [11] [9].

- Step 2: Identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs): Using risk assessment tools (e.g., Ishikawa diagram), identify potential factors (material, method, instrument, analyst) that could impact the ATP.

- Step 3: Conduct Experimental Design (DoE): Use a multivariate DoE (e.g., Full Factorial, Central Composite, Box-Behnken) to explore the interaction effects of the CMPs on the CMAs. This is more comprehensive than the screening done in a Plackett-Burman design [12].

- Step 4: Establish the Method Operable Design Region (MODR): The MODR is the multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables (e.g., pH, temperature) that have been demonstrated to provide assurance that the method will meet the ATP [9]. Any set of parameters within the MODR will produce valid results.

- Step 5: Control and Verify: Create a control strategy specifying the set points and acceptable ranges for the CMPs. Continuously verify method performance during routine use [10].

Workflow Diagrams

AQbD Robustness Development Workflow

Method Lifecycle with Feedback

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and solutions critical for developing and maintaining robust analytical methods.

| Item | Function in Robustness Testing |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Materials | Certified reference materials (CRMs) are essential for accurate instrument calibration and for assessing method accuracy and precision during development and ongoing verification. High-purity materials are critical for mitigating contamination in trace analysis [13]. |

| Standardized Buffer Solutions | Buffers with precisely known pH are vital for methods where pH is a critical parameter. Using standardized solutions minimizes unintended variations in mobile phase pH, a common source of robustness failure in chromatography [8] [6]. |

| Chromatography Columns with Lot-to-Lot Consistency | Columns from different manufacturing lots can have varying selectivity. Using columns from a supplier that ensures high lot-to-lot consistency or screening multiple columns during development enhances method ruggedness [8]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Standards | A mixture of key analytes used to verify that the entire analytical system (instrument, reagents, column, and analyst) is performing adequately before a sequence of samples is run. SSTs are a frontline defense for detecting robustness issues [9]. |

| Internal Standard Solutions | A compound added in a constant amount to all samples and calibrants in an analysis. It corrects for variability in sample preparation, injection volume, and instrument response, thereby improving the precision and robustness of the method, especially in mass spectrometry [14]. |

Identifying Key Parameters for Inorganic Methods (e.g., pH, Temperature, Mobile Phase Composition)

Troubleshooting Guide: Common HPLC Issues Related to Key Parameters

This guide addresses frequent challenges in inorganic analytical methods, helping you identify and resolve parameter-related issues to ensure robust performance.

1. Why is my baseline unstable (noisy or drifting)? An unstable baseline is often linked to mobile phase composition or temperature control. Key parameters to check include:

- Mobile Phase Composition: Ensure the mobile phase is prepared correctly from fresh, high-quality solvents. Incorrect composition or contamination can cause significant baseline drift [4]. For methods employing a gradient, verify that the pump's mixer is functioning correctly [4].

- Temperature Fluctuations: Maintain a consistent column temperature using a thermostat-controlled column oven, as temperature fluctuations are a common cause of baseline drift [4].

- System Contamination: Air bubbles in the system or a contaminated detector flow cell can lead to noise and drifting. Degas mobile phases thoroughly and purge the system to remove air. Clean or replace the flow cell if contamination is suspected [4].

2. Why are my peaks tailing or fronting? Asymmetric peaks often indicate issues with secondary interactions or overload, closely tied to pH and mobile phase composition.

- Peak Tailing: For basic analytes, this can be caused by ionic interactions with residual silanols on the stationary phase. Mitigation strategies include:

- Peak Fronting: This can be caused by column overload or a column temperature that is too low. Reduce the injection volume, dilute the sample, or increase the column temperature to resolve [4].

3. Why are my retention times shifting? Retention time instability directly challenges method robustness and is influenced by several key parameters.

- pH and Mobile Phase Composition: Inconsistent mobile phase pH or composition is a primary culprit. Always prepare fresh mobile phase and use an effective buffer within ±1.0 pH unit of its pKa to maintain control [15].

- Temperature Control: Poor column temperature control leads to retention time drift. Always use a thermostat column oven for precise temperature management [4].

- Flow Rate and Equilibration: Verify the pump flow rate is accurate and ensure the column is fully equilibrated with the new mobile phase, especially after a change in solvent [4].

4. Why is my method failing during transfer to another lab (lack of ruggedness)? A method that performs well in one lab but fails in another lacks ruggedness, often due to uncontrolled key parameters.

- Parameter Sensitivity: The method may be overly sensitive to minor, unavoidable variations in parameters like mobile phase pH, flow rate, or column temperature between different instruments or operators [1].

- Insufficient Control Strategy: The method's analytical control strategy may not adequately define the proven acceptable ranges (PAR) for these parameters. Implementing a formal robustness test during method development can identify these critical parameters and establish their allowable ranges, ensuring the method can withstand real-world variations [16] [1].

5. How can I reduce metal adduction in oligonucleotide analysis by MS? For biopharmaceuticals like oligonucleotides, sensitivity in MS detection can be severely hampered by adduct formation with alkali metal ions. Key parameters and practices include:

- Mobile Phase and Sample Purity: Use high-purity, MS-grade solvents and plastic containers (instead of glass) for mobile phases and samples to prevent leaching of metal ions [17].

- System Cleanliness: Flush the LC system with 0.1% formic acid in water overnight before use to remove alkali metal ions from the flow path [17].

- Chromatographic Separation: Employ a small-pore reversed-phase or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) column in-line to separate metal ions from the analytes prior to MS detection [17].

Experimental Protocol: Robustness Testing via Factorial Design

This protocol provides a systematic methodology for identifying key parameters and establishing their Proven Acceptable Ranges (PAR) as recommended by ICH Q14 [16].

Objective: To empirically determine the effect of small, deliberate variations in method parameters on analytical performance and define the method's robustness.

Materials and Reagents

- HPLC system with thermostat-controlled column oven

- Analytical column specified in the method

- Mobile phase components (HPLC grade)

- Standard and sample solutions

- Data acquisition system

Procedure:

- Identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs): Using prior knowledge and risk assessment tools (e.g., Ishikawa diagram, FMEA), select parameters most likely to impact method performance. Common CMPs for inorganic methods include:

Define the Experimental Domain: For each CMP, define a high (+) and low (-) level that represents a small, scientifically justifiable variation from the nominal setpoint.

Design the Experiment: Use a fractional factorial design (e.g., a 2^(n-1) design) to efficiently study the main effects of multiple parameters with a manageable number of experimental runs. The table below illustrates an experimental design for three parameters.

Execute the Study: Run the analytical method according to the experimental design matrix. A typical matrix for three parameters is shown below.

| Experiment Run | Parameter A: pH | Parameter B: Flow Rate (mL/min) | Parameter C: Column Temp (°C) | Results (e.g., Resolution, Retention Time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - (e.g., 3.0) | - (e.g., 0.9) | - (e.g., 28) | ... |

| 2 | + (e.g., 3.2) | - | - | ... |

| 3 | - | + (e.g., 1.1) | - | ... |

| 4 | + | + | - | ... |

| 5 | - | - | + (e.g., 32) | ... |

| 6 | + | - | + | ... |

| 7 | - | + | + | ... |

| 8 | + | + | + | ... |

Analyze the Data: Evaluate key performance indicators (e.g., resolution, retention time, tailing factor, peak area) for each run. Statistical analysis or simple comparison to acceptance criteria can be used to determine which parameters have a significant effect.

Establish Proven Acceptable Ranges (PAR): Based on the results, define the range for each parameter within which all method performance criteria are met. These PARs become part of the method's Established Conditions and control strategy [16].

The following workflow summarizes the lifecycle of an analytical procedure, integrating robustness testing as a core development activity:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between robustness and ruggedness?

- Robustness is an intra-laboratory study that measures a method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH, temperature) [1].

- Ruggedness is an inter-laboratory study that measures the reproducibility of results when the same method is applied under real-world conditions, such as with different analysts, instruments, or laboratories [1].

When should robustness testing be performed? Robustness testing should be performed during the method development and validation stages, before the method is transferred to other laboratories or used for routine analysis. This proactive approach identifies critical parameters early, ensuring the method is reliable and reducing the risk of failure during validation or transfer [1].

How do I know which parameters to test for robustness? Parameters should be selected based on scientific rationale and prior knowledge. A risk assessment is the primary tool for this. Techniques like Ishikawa (fishbone) diagrams or Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) can help identify which method parameters (e.g., pH, mobile phase composition, temperature) have the highest potential impact on the method's performance and should be prioritized for testing [16] [18].

Is a buffer always necessary in the mobile phase? No. For the separation of neutral molecules, pure water may be sufficient. However, for ionizable analytes (acids, bases, zwitterions), the mobile phase pH must be controlled. While simple acids (e.g., TFA, formic acid) can be used, a true buffer is required to tightly control the pH for critical assays. A buffer is most effective within ±1.0 pH unit of its pKa value [15].

What is the role of an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) in parameter identification? The ATP is a foundational element from the ICH Q14 guideline. It defines what the analytical procedure is intended to measure and the required performance criteria. The ATP drives method development by forcing scientists to consider, from the outset, which method parameters and performance characteristics are critical to fulfilling this profile, thereby guiding the selection of parameters for robustness studies [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials and their functions for developing and troubleshooting inorganic analytical methods.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| pH Buffers (e.g., Phosphate, Formate, Acetate) | Control the ionic strength and pH of the mobile phase, which is critical for reproducible retention of ionizable analytes [15]. |

| MS-Grade Solvents & Additives (e.g., Formic Acid, TFA) | High-purity solvents and volatile additives minimize signal suppression and adduct formation in LC-MS applications, crucial for analyzing biomolecules [17] [15]. |

| Thermostat Column Oven | Maintains a consistent and precise column temperature, a key parameter for ensuring retention time reproducibility and baseline stability [4]. |

| Guard Column | A small, disposable cartridge placed before the analytical column to protect it from particulate matter and strongly adsorbed contaminants, extending its lifetime [4]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate regulatory requirements for robustness testing of inorganic analytical methods.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the updated ICH guidance on analytical procedure validation, and how does it impact robustness testing?

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline, implemented in June 2024, provides an expanded framework for analytical procedure validation [19]. A key change from the previous Q2(R1) involves the definition of robustness. The guideline now requires testing to demonstrate a method's reliability in response to the deliberate variation of method parameters, as well as the stability of samples and reagents [19]. This is a shift from the previous focus only on small, deliberate changes. You should investigate robustness during the method development phase, prior to formal validation, using a risk-based approach [19].

Q2: Which recent ICH guidelines should I consult for stability testing protocols?

For stability testing, consult the draft ICH Q1 guidance issued in June 2025 [20]. This document is a consolidated revision of the former Q1A(R2) through Q1E series and provides a harmonized approach to stability data for drug substances and drug products [20]. It also newly covers stability guidance for advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), vaccines, and other complex biological products [20].

Q3: Are there new FDA guidelines on manufacturing and controls relevant to analytical methods?

Yes, the FDA has recently issued several relevant draft guidances. In January 2025, the agency released "Considerations for Complying with 21 CFR 211.110," which explains in-process controls in the context of advanced manufacturing [21] [22]. Furthermore, the "Advanced Manufacturing Technologies (AMT) Designation Program" guidance was finalized in December 2024, which may influence the development and control strategies for novel manufacturing processes [21].

Q4: How does ICH Q9 on Quality Risk Management apply to robustness studies?

ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management) promotes a risk-based approach to guide your robustness studies [23] [19]. You should use risk assessment to identify the method parameters that are most critical and pose the highest risk of variation. This ensures your validation efforts are focused appropriately. For example, parameters with high human intervention or reliance on third-party consumables are often higher risk [19].

Q5: What is the role of USP guidelines in method development and validation?

The USP Drug Classification (DC) is updated annually and is used by health plans for formulary development [24]. While not directly prescribing analytical methods, its classifications can influence the requirements for the drugs you are developing. Staying informed about the USP DC 2025 and upcoming MMG v10.0 (anticipated 2026) is crucial for understanding the commercial landscape and potential regulatory expectations for your products [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Failing to Meet Robustness Criteria During Method Validation

Problem: Your analytical method shows unacceptable variation when parameters are deliberately changed, indicating a lack of robustness.

Solution:

- Investigate During Development: Robustness should be evaluated during method development, before validation begins. Use a risk-based approach to test parameters [19].

- Key Parameters to Test: The ICH Q2(R2) Annex 2 provides examples. Your investigation should consider [19]:

- Reagent Preparation: Vary concentration or pH.

- Human-Operated Steps: Vary incubation times or volumes for spiked internal standards.

- Third-Party Consumables: Test different lots of columns, cartridges, or capillaries.

- Stability: Evaluate preparation-to-analysis time for unstable reagents or samples.

- Action: If a parameter is found to be highly sensitive, define a tight, controlled operating range for it in your final method procedure.

Issue 2: Integrating a Risk-Based Approach into Robustness Studies

Problem: It is unclear how to select which parameters to include in robustness studies.

Solution:

- Follow ICH Q9: Apply formal quality risk management principles [23] [19].

- Systematic Risk Assessment:

- Identify all potential variables in your analytical procedure.

- Analyze and rank them based on the potential impact of their variation on the result and the probability of that variation occurring.

- Evaluate and prioritize high-risk parameters for your robustness studies.

- Example: A method step relying on a precise manual pipetting step is a higher risk than a step performed by a calibrated, automated dispenser.

Issue 3: Navigating Recent Updates to Multiple, Overlapping Guidelines

Problem: Staying current and ensuring compliance with simultaneous updates from ICH, FDA, and other bodies is challenging.

Solution:

- Monitor Key Sources: Regularly check the FDA's "Newly Added Guidance Documents" page and other official channels [21].

- Focus on Core ICH Updates: Prioritize understanding the recently implemented ICH Q2(R2) and the draft ICH Q1 [19] [20].

- Engage Proactively: For USP classifications, monitor annual draft releases and participate in public comment periods [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for Robustness Testing

This table details key materials and their functions when conducting robustness studies for inorganic analytical methods.

| Item | Function in Robustness Testing |

|---|---|

| Different Lots of Consumables (e.g., chromatographic columns, filters) | Evaluates the impact of natural variability in third-party materials on method performance [19]. |

| Reagents of Varying Purity/Grade | Tests the method's sensitivity to changes in reagent quality, which can affect background noise and specificity [19]. |

| Buffers at Deliberately Varied pH | Challenges the method's selectivity and ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of expected components [19]. |

| Stability-Tested Sample/Standard Solutions | Determines the allowable preparation-to-analysis time window by assessing analyte stability under various conditions (e.g., time, temperature) [19]. |

| Internal Standard Solutions | When used, varying the spiked volume tests the method's precision and accuracy under different conditions [19]. |

Experimental Workflow for Robustness Testing

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for planning and executing robustness studies, integrating risk assessment and regulatory guidance as discussed in the FAQs and troubleshooting sections.

For researchers and scientists in drug development, the reliability of inorganic analytical methods is paramount. Methods that lack robustness—the capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters—are highly susceptible to producing Out-of-Specification (OOS) and Out-of-Trend (OOT) results [25] [1]. An OOS result is a test result that falls outside established acceptance criteria, while an OOT result is a data point that, though potentially within specification, breaks an established analytical pattern over time [26]. This technical guide explores the consequences of non-robust methods and provides a structured framework for troubleshooting and investigation.

FAQ: Understanding OOS and OOT in the Context of Method Robustness

What is the fundamental link between a non-robust method and OOS results?

A non-robust method is highly sensitive to minor, uncontrolled variations in analytical conditions. In a real-world laboratory, parameters like mobile phase pH, column temperature, or instrument flow rate naturally fluctuate. If a method is not robust, these minor variations—which fall within the method's operational tolerance—can cause significant shifts in analytical results, pushing them outside specifications and triggering an OOS [25] [1]. Essentially, a non-robust method fails to account for the normal variability of a working laboratory environment.

How can a method be within validation criteria but still cause OOT results?

Method validation is often conducted under "ideal" conditions. A method may pass validation criteria but still lack ruggedness, which is the reproducibility of results under different real-world conditions, such as different analysts, instruments, or laboratories [1]. This can lead to OOT results, where data begins to show unexpected patterns or drift when the method is deployed more widely or over a longer period. OOT can be an early warning signal of a method's underlying sensitivity to factors not fully explored during its initial validation [26].

What are the regulatory consequences of invalidating OOS results without a scientifically sound investigation?

Regulatory agencies like the FDA consider the thorough investigation of all OOS results a mandatory requirement under cGMP regulations (21 CFR 211.192) [27] [28]. Invalidating an OOS result without a scientifically sound assignable cause—for instance, attributing it to vague "analyst error" without conclusive evidence—is a serious compliance failure. Companies that frequently invalidate OOS results have received warning letters, which can lead to costly remediation efforts, delayed product approvals, and damage to regulatory trust [27].

What is the key difference between robustness and ruggedness testing?

While related, these two terms describe different aspects of method reliability. The table below outlines their key differences.

Table: Key Differences Between Robustness and Ruggedness Testing

| Feature | Robustness Testing | Ruggedness Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Evaluate performance under small, deliberate parameter changes [25] | Evaluate reproducibility under real-world, environmental variations [1] |

| Scope & Variations | Intra-laboratory; small, controlled changes (e.g., pH, flow rate) [25] [1] | Inter-laboratory; broader factors (e.g., different analysts, instruments, days) [1] |

| Primary Focus | Internal method parameters | External laboratory conditions |

| Typical Timing | During method development/validation [25] | Later in validation, often for method transfer [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating OOS and OOT Rooted in Method Robustness

Phase I: Preliminary Assessment

The first phase is a rapid, focused investigation to identify and correct obvious errors.

- Accuracy Assessment: The analyst and supervisor should immediately re-examine the solutions, methodology, and instrumentation used. This is a non-experimental review to identify gross laboratory errors like incorrect standard preparation, sample mix-ups, or transcription errors [28].

- Historical Data Review: Analyze previous test results and investigations for the same product or method. This helps identify any recurring patterns or previous OOT signals that may point to an inherent method weakness [28].

- Experimental Confirmation (Re-analysis): If no error is found, re-introduce the original sample preparation into the instrument. Perform at least three replicate injections to establish a mean and standard deviation, helping to rule out transient instrument malfunctions [28].

Phase II: Expanded Investigation

If Phase I does not identify a conclusive laboratory error, a comprehensive, cross-functional investigation must be initiated.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA): Apply structured methodologies like the "5 Whys" or a Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram to investigate potential causes [26]. A common framework for investigating potential method-related causes is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram: Investigating Root Causes of OOS/OOT

Re-testing and Re-sampling:

- Re-test: Perform the test again on a portion of the original, homogeneous sample. This should ideally be done by a second, experienced analyst [28].

- Re-sample: If the investigation points to a potential sampling error, obtain a new sample from the original batch. For bulk materials, use a "thief" sampler to collect representative portions from the top, middle, and bottom of the container [28].

System Suitability and Robustness Evaluation: If method robustness is suspected, a designed experiment (e.g., a Plackett-Burman or fractional factorial design) should be considered to systematically test which parameters most significantly impact the results [25]. This helps move from speculation to data-driven understanding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Robust Method Development

The following table lists essential materials and their functions in developing and troubleshooting robust analytical methods.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Robust Method Development

| Item | Primary Function | Importance for Robustness |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Calibrate instruments and verify method accuracy. | High-purity standards are fundamental for establishing a reliable baseline and detecting subtle method shifts [29]. |

| Buffers & pH Standards | Control the pH of mobile phases and sample solutions. | Critical for methods where analyte retention or response is pH-sensitive; ensures consistency across preparations [25]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | Separate analytes in HPLC/UPLC systems. | Testing different column lots and brands during validation is a key ruggedness test to ensure consistent performance [25] [1]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Serve as the mobile phase and sample diluent. | Variability in solvent purity or grade can introduce artifacts and baseline noise, affecting detection limits [29]. |

| System Suitability Test Kits | Verify that the total analytical system is fit for purpose. | Provides a daily check on key parameters (e.g., precision, resolution, tailing factor) to guard against method drift [25]. |

Proactive Protocol: Designing a Robustness Study

A well-designed robustness study during method development can prevent future OOS/OOT results. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for a screening study using a fractional factorial design.

Diagram: Robustness Study Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- Parameter Selection: Identify 4-6 critical method parameters likely to vary in routine use. For an HPLC method, these often include mobile phase pH (±0.1-0.2 units), buffer concentration (±5-10%), column temperature (±2-5°C), and flow rate (±5-10%) [25].

- Define Ranges: Set realistic "high" and "low" levels for each parameter based on expected variations in a laboratory environment (e.g., pH = 3.8 and 4.2).

- Experimental Design: Use a screening design like a Plackett-Burman or fractional factorial design. These designs allow you to efficiently study multiple factors simultaneously with a minimal number of experimental runs. For example, a Plackett-Burman design can screen up to 11 factors in only 12 experimental runs [25].

- Execution and Analysis: Execute the experiments as per the design matrix. Record critical responses for each run (e.g., retention time, peak area, tailing factor, resolution). Analyze the data using statistical software to determine which parameters have a statistically significant effect on the responses.

- Establish Controls: For parameters identified as significant, establish tight control limits in the method documentation. For non-significant parameters, the method is considered robust over the tested range [25].

Executing Robustness Studies: A Practical DoE Approach

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between a traditional approach and QbD? The traditional approach, often one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT), adjusts variables independently and can miss critical interactions, potentially leading to suboptimal methods. QbD is a systematic, proactive approach that uses statistical design of experiments (DoE) to understand how variables interact, building quality and robustness into the method from the start [30].

What is an Analytical Target Profile (ATP)? The ATP is a prospective summary of the performance requirements for an analytical method. For a chromatographic method, it defines criteria such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and the required resolution between critical pairs of analytes to ensure the method is fit for its purpose [31] [32].

What are Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) and Critical Method Attributes (CMAs)?

- CMPs are the controllable variables of an analytical method (e.g., column temperature, mobile phase pH, flow rate) that can have a direct impact on the method's performance [31].

- CMAs are the measurable outputs that define method performance (e.g., resolution between two peaks, tailing factor, retention time) [31]. The goal of AQbD is to understand the relationship between CMPs and CMAs.

What is a Method Operable Design Region (MODR)? The MODR is the multidimensional combination of CMPs (e.g., pH, temperature) and their demonstrated ranges within which the method performs as specified by the CMA acceptance criteria. Operating within the MODR provides flexibility and ensures robustness, as changes within this space do not require regulatory notification [31].

How is robustness built into a QbD-based method? Robustness is an intrinsic outcome of the AQbD process. By using DoE to model the method's behavior, you can identify a robust operating region (the MODR) where the CMA criteria are consistently met despite small, deliberate variations in method parameters [12] [31]. This is formally tested using robustness evaluation designs, such as full factorial or Plackett-Burman designs [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Poor Chromatographic Separation

This issue manifests as variable retention times, peak tailing, or insufficient resolution between critical peak pairs.

Investigation Path:

- Verify Critical Method Parameters: Check that the system is operating within the defined MODR. Confirm mobile phase composition, pH, column temperature, and flow rate against the method specifications [31].

- Review the Risk Assessment: Consult the initial Cause & Effect analysis. Key parameters to investigate include:

- Mobile Phase pH: Small variations can significantly impact the ionization and retention of ionizable compounds, leading to major shifts in selectivity [32].

- Column Temperature: Temperature fluctuations can affect retention time and resolution [33].

- Column Chemistry: Different column batches or brands, even with the same description, can have varying selectivity. Ensure a specific column brand and chemistry is used [33].

- Check System Suitability: Ensure the system suitability test (SST) is passing. If SST fails, it indicates a fundamental problem with the method setup or instrument performance that must be addressed before sample analysis.

Solution: If parameters are within the MODR and the problem persists, it may indicate that the MODR was not adequately defined. A focused DoE, such as a full factorial design around the suspected critical parameters (e.g., pH ± 0.2, temperature ± 5°C), can be used to remap a more robust operating space [12] [32].

Problem: Method Fails During Transfer to a New Laboratory

The method, which worked well in the development lab, does not meet performance criteria in another lab.

Investigation Path:

- Compare Equipment and Reagents: Differences in HPLC instrument models, dwell volume, detector characteristics, or reagent suppliers (e.g., buffer salt purity, water quality) can cause failure [32].

- Audit the Procedure: Ensure the receiving lab is following the exact documented procedure, including sample preparation steps, sonication time, and filtration techniques.

- Analyze the MODR: The failure may occur because the new lab's "standard operating conditions" fall outside the true robust region of the method. The method may be too sensitive to a parameter that was not adequately controlled.

Solution: Prior to transfer, use a risk assessment focused on inter-lab variability. Then, perform a co-validation or inter-lab ruggedness study. This involves both labs testing the same samples using a DoE to confirm the MODR is applicable in both environments. This collaborative approach builds a more resilient method [32].

Problem: Lack of Specificity in a Complex Sample Matrix

The method cannot adequately distinguish the analyte from interfering peaks, such as degradation products or excipients.

Investigation Path:

- Perform Forced Degradation Studies: Stress the sample under acid, base, oxidative, thermal, and photolytic conditions. This helps identify potential degradation products and confirms that the method can separate the analyte from its impurities [33] [34].

- Revisit the Scouting Stage: The selected chromatographic conditions (column chemistry and mobile phase) may not be optimal for the required selectivity. A systematic screening of different column chemistries (e.g., C18, phenyl, cyano) and organic modifiers (acetonitrile vs. methanol) may be necessary [33] [32].

Solution: Employ a QbD-based screening approach. Use a software-assisted platform to automatically screen multiple columns and mobile phase conditions across a wide pH range. The data generated will help identify the chromatographic conditions that provide the best selectivity and peak shape for the analyte and its potential impurities [33].

Experimental Protocols for Key QbD Activities

Protocol: Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

| Aspect | Description | Example for an HPLC Assay Method |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Define what the method must achieve [31]. | "To quantify active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in film-coated tablets and related substances." |

| Technique | Select the analytical technique [31]. | Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) with UV detection. |

| Performance Requirements | Define the required method performance with acceptance criteria [32]. | "The procedure must be able to accurately and precisely quantify drug substance over the range of 70%-130% of the nominal concentration such that reported measurements fall within ± 3% of the true value with at least 95% probability." |

| Critical Method Attributes (CMAs) | List the key output characteristics to measure [31] [34]. | Resolution between critical pair ≥ 2.0; Tailing factor ≤ 2.0; Theoretical plates ≥ 2000. |

Protocol: Conducting a Risk Assessment using a Cause & Effect Matrix

| Step | Action | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Deconstruct the Method | Break down the analytical procedure into unit operations [32]. | e.g., Sample Preparation, Chromatographic Separation, Data Analysis. |

| 2. List Inputs & Attributes | For each unit operation, list all input parameters (CMPs) and output attributes (CMAs). | CMPs: Weighing, dilution volume, sonication time, mobile phase pH, column temperature, flow rate, wavelength.CMAs: Accuracy, Precision, Resolution, Tailing Factor. |

| 3. Score & Prioritize | Use a risk matrix to score the impact of each CMP on each CMA (e.g., High/Medium/Low) [32]. | Mobile phase pH has a High impact on Resolution.Sonication time may have a Low impact on Accuracy. |

| 4. Identify High-Risk CMPs | Focus experimental efforts on the parameters with the highest risk scores. | Parameters like mobile phase pH, gradient profile, and column temperature are typically high-risk and require investigation via DoE. |

Protocol: Defining the MODR using a Box-Behnken Design (BBD)

This is a response surface methodology used for optimization [12] [34].

- Select Critical Factors: Choose 3 high-risk CMPs identified from the risk assessment (e.g., Factor A: Mobile Phase pH, Factor B: Column Temperature, Factor C: Flow Rate).

- Define Ranges: Set a low, middle, and high level for each factor based on scientific judgment.

- Run the Experiments: The BBD will generate a set of experimental runs (typically 15 for 3 factors) that efficiently explore the experimental space.

- Analyze Responses: For each experimental run, measure the CMAs (e.g., Resolution, Tailing).

- Build a Model: Use statistical software to build a mathematical model linking the CMPs to the CMAs.

- Establish the MODR: Using Monte Carlo simulations, calculate the combination of CMP ranges where there is a high probability (e.g., ≥90%) that the CMA criteria will be met. This region is your MODR [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in AQbD |

|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | A statistical tool to plan, design, and analyze multivariate experiments. It is core to efficiently understanding factor interactions and building the MODR [12] [34]. |

| Quality Risk Management Tools | Structured methods like Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) and Fishbone (Ishikawa) diagrams. Used to systematically identify and prioritize potential sources of method failure [30] [32]. |

| Method Scouting Columns | A set of HPLC columns with different chemistries (e.g., C18, Phenyl, Cyano). Essential for the initial screening phase to select the column that provides the best selectivity for the analyte and its impurities [33]. |

| pH Buffers & Mobile Phase Modifiers | High-purity reagents to prepare mobile phases. Critical for controlling retention and selectivity, especially for ionizable compounds. Their consistency is vital for robustness [31] [34]. |

| Forced Degradation Reagents | Chemicals (e.g., HCl, NaOH, H₂O₂) used to intentionally degrade the sample. This helps validate method specificity by ensuring the method can separate the API from its degradation products [33] [34]. |

AQbD Workflow Diagram

Robustness Evaluation Logic

Troubleshooting Guides for Screening Experiments

Issue 1: Unreliable or Inconsistent Effect Estimates

- Problem: After running your screening design, the effect estimates for factors are confusing or do not align with scientific expectation.

- Solution: Check the alias structure of your design. In Resolution III designs like Plackett-Burman, main effects are confounded with two-factor interactions [35] [36]. If an active two-factor interaction is aliased with a main effect, it can distort the estimate of that main effect.

- Action: Use a normal probability plot of the effects to help distinguish active factors from inert ones; active effects will deviate from the straight line formed by the inactive effects [35]. If resources allow, fold over the entire design (a technique available in software like Minitab) to break the aliasing between main effects and two-factor interactions [37].

Issue 2: The Design Requires Too Many Experimental Runs

- Problem: A full factorial design is not feasible due to a high number of factors.

- Solution: Employ a highly fractional design. A Plackett-Burman design allows you to study up to

k = N-1factors inNruns, whereNis a multiple of 4 (e.g., 12, 20, 24) [35] [38]. This is often more flexible than a standard fractional factorial, where the run size is a power of two [36].

Issue 3: Suspecting Curvature or Nonlinear Effects

- Problem: You suspect the relationship between a factor and the response is not linear, but your screening design only has two levels.

- Solution: Add center points to your two-level design [37]. Replicating several runs at the mid-point level of all factors provides a check for curvature and an independent estimate of pure experimental error without significantly increasing the number of runs.

Issue 4: Handling a Large Number of Factors with Limited Runs

- Problem: You need to screen more than 15 factors with a very limited budget for runs.

- Solution: A Plackett-Burman design is specifically suited for this. For example, you can screen 11 factors in just 12 runs, or 19 factors in 20 runs [35] [38]. Be aware that this economy comes at the cost of more complex confounding patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary goal of a screening design? The goal is to efficiently identify the few critical factors from a large set of potential factors that have significant effects on your response. This allows you to focus further, more detailed optimization experiments on these vital few factors [36] [37].

FAQ 2: When should I choose a Plackett-Burman design over a fractional factorial design? Choose a Plackett-Burman design when you need more flexibility in the number of runs, especially when the number of factors is large and you are strictly focused on screening main effects [36]. For example, with 10 factors, you might choose a 12-run Plackett-Burman over a 16-run fractional factorial to save resources [36]. If you need clearer information on two-factor interactions from the start, a higher-resolution fractional factorial or a Definitive Screening Design might be better [37].

FAQ 3: What does "Resolution III" mean, and why is it important? Resolution III means that while main effects are not confounded with each other, they are confounded with two-factor interactions [35] [36]. It is important because it implies that if a two-factor interaction is active, it can bias the estimate of the main effect it is aliased with. Therefore, the validity of a Resolution III design relies on the assumption that two-factor interactions are negligible during the initial screening phase [36].

FAQ 4: Can I estimate interaction effects with a Plackett-Burman design? Typically, no. Plackett-Burman designs are primarily used to estimate main effects [35]. While it is mathematically possible to calculate some two-factor interaction effects, they are heavily confounded with many other two-factor interactions, making it very difficult to draw clear conclusions [36]. For instance, in a 12-run design for 10 factors, a single two-factor interaction may be confounded with 28 others [36].

FAQ 5: How is robustness testing of an analytical method related to screening designs? Robustness testing evaluates an analytical method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [1]. When the number of potential parameters (e.g., pH, mobile phase composition, temperature) is high, a Plackett-Burman design is the most recommended and employed chemometric tool to efficiently identify which parameters have a significant effect on the method's results, thus defining its robustness [12].

Comparison of Screening Design Properties

The table below summarizes key characteristics of different screening design approaches.

| Feature | Full Factorial | Fractional Factorial (2k-p) | Plackett-Burman |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Estimate all main and interaction effects | Screen main effects and some interactions | Screen main effects only [35] |

| Run Structure | Power of 2 (e.g., 8, 16, 32) | Power of 2 (e.g., 8, 16, 32) | Multiple of 4 (e.g., 12, 20, 24) [36] [38] |

| Design Resolution | Resolution V+ (depends on size) | Varies (e.g., III, IV, V) | Resolution III [35] [36] |

| Aliasing (Confounding) | None | Clear, complete aliasing (e.g., D=ABC) [38] | Complex, partial aliasing [36] |

| Typical Use Case | Small number of factors (e.g., <5) | Balanced screening with some interaction insight | Highly economical screening of many factors [35] [39] |

Experimental Protocol for a Robustness Study Using a Plackett-Burman Design

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying a Plackett-Burman design to robustness testing of an analytical method.

Step 1: Define Factors and Levels Identify the method parameters (factors) to be investigated (e.g., pH, flow rate, column temperature, mobile phase composition). For each factor, define a high (+1) and low (-1) level that represents a small, deliberate variation from the nominal method setting [1].

Step 2: Select the Design

Based on the number of factors k, select a Plackett-Burman design with N runs, where N is the smallest multiple of 4 greater than k. For example, for 7-11 factors, a 12-run design is appropriate [35] [38]. Software like Minitab or JMP can automatically generate the design matrix.

Step 3: Execute Experiments and Collect Data Run the experiments in a randomized order to protect against systematic biases [35]. For each run, measure the critical quality responses (e.g., retention time, peak area, resolution).

Step 4: Analyze the Data

- Calculate Main Effects: For each factor, the main effect is the difference between the average response at the high level and the average response at the low level [35] [39].

- Identify Significant Effects: Use statistical significance testing (e.g., Pareto chart, t-tests) and/or a normal probability plot to determine which factors have effects larger than what would be expected by random chance [35].

Step 5: Draw Conclusions and Plan Next Steps Factors with statistically significant main effects are considered critical to the method's robustness. The method should be refined to tightly control these sensitive parameters, or their operating ranges should be adjusted to a more robust region [1]. Non-significant factors can be considered robust within the tested ranges.

Workflow for a Screening Experiment

The diagram below visualizes the logical workflow for planning, executing, and analyzing a screening design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and solutions used in developing and validating analytical methods where screening designs are applied.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Essential for preparing mobile phases and standards in techniques like HPLC and ICP-MS. High purity is critical to minimize background noise and contamination that could skew results during robustness testing [13]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used to calibrate instruments and validate method accuracy. Their use is a key part of robust QC protocols, ensuring data traceability and regulatory compliance [13]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | Different column batches or types from various manufacturers are often included as a categorical factor in robustness testing to ensure method performance is not column-sensitive [1]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Used to control pH, which is a frequently tested parameter in robustness studies for methods like ion chromatography (IC) and LC-MS to ensure stability of the analytical conditions [1]. |

| Internal Standards | Used in mass spectrometry (e.g., ICP-MS) and chromatography to correct for instrument fluctuations and sample preparation errors, improving the precision and ruggedness of the method. |

In the development and validation of inorganic analytical methods, such as those using ICP-MS or IC, ensuring robustness is a critical requirement. Robustness is defined as a measure of your method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters, indicating its reliability during normal usage conditions [1]. Experimental optimization designs provide a structured, statistical framework to achieve this by systematically exploring how multiple input variables (factors) influence key output responses (e.g., detection limit, signal intensity, precision). This technical support guide is designed to help researchers and scientists effectively employ Full Factorial Design and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to build robustness directly into their analytical methods, thereby reducing the risk of method failure during transfer to quality control laboratories or regulatory submission [12] [1].

Core Optimization Concepts: A FAQ Guide

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a screening design and an optimization design?

- Screening designs (e.g., two-level full factorial or Plackett-Burman designs) are used in the early stages of method development to identify which factors from a large set have a significant influence on your analytical response. They are efficient for evaluating main effects but provide limited information on complex interactions or curvature [12] [40].

- Optimization designs (e.g., RSM designs like Central Composite or Box-Behnken) are used after critical factors are identified. They model the non-linear, quadratic relationships between factors and responses, allowing you to pinpoint the precise combination of factor levels that delivers the optimal performance, such as maximum signal-to-noise or minimal impurity interference [40].

FAQ 2: Why is a Full Factorial Design considered the foundation for many robustness tests? A Full Factorial Design investigates all possible combinations of the levels for all factors. Its strength lies in its ability to comprehensively estimate not only the main effect of each individual factor but also the interaction effects between them [41]. In an analytical context, this means you can determine if the effect of changing the mobile phase pH, for example, depends on the level of the column temperature. This complete picture is essential for understanding a method's behavior and establishing its robust operating ranges [41] [1].

FAQ 3: My experimental resources are limited, and a full factorial design has too many runs. What are my options? When a full factorial design is too resource-intensive, you have several efficient alternatives:

- Fractional Factorial Designs: These study a carefully chosen fraction (e.g., half, a quarter) of the full factorial combinations. While this is highly efficient, it comes at the cost of confounding some interaction effects with main effects, which must be considered during the design phase [41].

- D-Optimal Designs: These are computer-generated designs that select the set of experimental runs from a candidate list that maximizes the information matrix's determinant for a specific model. They are particularly useful when the design space is constrained or when standard designs require too many runs [42].

FAQ 4: How does Response Surface Methodology (RSM) help in finding the true optimum? RSM is a collection of statistical techniques used to explore the relationships between several explanatory variables and one or more response variables. The core idea is to use a sequence of designed experiments (like a Central Composite Design) to fit an empirical, often second-order, polynomial model [40]. This model allows you to create a "response surface"—a 3D map that visualizes how your response changes with your factors. By examining this surface, you can accurately locate the peak (maximum), valley (minimum), or ridge (target value) of your response, moving beyond the linear estimates provided by simpler two-level designs [40].

FAQ 5: What are the critical parameters to evaluate when assessing the robustness of an optimized analytical method? Once a method is optimized, its robustness is tested by introducing small, deliberate variations to critical method parameters identified during optimization. Key parameters to test for a chromatographic method include [1]:

- Mobile Phase Composition: Slight changes in the ratio of solvents (e.g., ± 1-2%).

- pH of the Buffer: A small, justifiable fluctuation (e.g., ± 0.1 units).

- Flow Rate: A minor shift (e.g., ± 0.1 mL/min).

- Column Temperature: A small fluctuation (e.g., ± 2°C).

- Different Instrumentation or Columns: Using columns from different batches or manufacturers.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Inability to Reproduce Optimal Conditions from RSM Model

- Problem: The predicted optimal settings from your RSM model do not yield the expected performance in the laboratory.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Verify Model Significance: Check the statistical significance of your regression model (p-value for the model from ANOVA) and the coefficient of determination (R²). A low R² or an insignificant model indicates a poor fit to your data [40].

- Check for Lack of Fit: A significant "lack-of-fit" p-value in the ANOVA suggests the model is insufficient to describe the relationship in the experimental data. You may need to include additional factors or consider a different model form [40].

- Confirm Factor Ranges: Ensure the optimal point is not extrapolated far outside the experimental region you tested. The model is only an approximation within the studied space [40].

- Replicate the Optimum: Always include replication runs at the predicted optimum conditions to empirically verify the response and estimate the pure error.

Issue 2: High Variation in Responses Obscuring Factor Effects

- Problem: Experimental "noise" is so high that it becomes difficult to distinguish the true signal (the effect of the factors).

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Implement Blocking: If experiments were conducted over multiple days or by different analysts, use "blocking" in your design to account for this known source of variation [41].

- Increase Replication: Replicate critical points or center points in your design to obtain a better estimate of experimental error, which increases the power of your statistical tests [41].

- Randomize Run Order: Ensure the order of your experimental runs was fully randomized to mitigate the influence of lurking variables and time-dependent effects [41].

- Review Procedures: Standardize and meticulously document all sample preparation and measurement procedures to minimize introduced variability.

Issue 3: The Optimized Method Fails During Ruggedness or Inter-Laboratory Testing

- Problem: The method performs well in the development lab but fails when used by a different analyst, on different equipment, or in a different laboratory.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Distinguish Robustness from Ruggedness: Understand that robustness tests small, deliberate changes to method parameters (intra-lab), while ruggedness assesses the method's performance under real-world variations like different analysts, instruments, and labs [1].

- Expand Robustness Testing: The factors causing the failure (e.g., a specific instrument model) may not have been included in your original robustness study. Revisit and expand your robustness testing plan to include these "environmental" factors [1].

- Tighten Control Limits: If a parameter (e.g., mobile phase pH) is found to be highly sensitive during ruggedness testing, establish tighter control limits for it in the method's standard operating procedure (SOP).

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Two-Level Full Factorial Robustness Test

This protocol is ideal for a final robustness assessment of an optimized method with a limited number (typically 3-5) of critical parameters [12] [1].

Objective: To evaluate the impact of small variations in critical method parameters on the analytical response and establish the method's robustness.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Select Factors and Levels: Choose 3 to 5 critical parameters (e.g., Flow Rate, Column Temperature, %Organic). For each, define a nominal level (the optimum) and a high/low level representing a small, realistic variation (e.g., Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min [nominal], ±0.1 mL/min [variation]) [1].

- Generate the Design Matrix: For a 3-factor design, this will be a 2³ full factorial, requiring 8 experimental runs. The matrix will list all combinations of the high and low levels for each factor.

- Randomize and Execute: Randomize the run order to prevent bias. Perform the experiments and record your primary response (e.g., peak area, retention time).

- Statistical Analysis:

- Perform an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine which factors have a statistically significant effect (p-value < 0.05) on the response [41].

- Use Pareto charts or normal probability plots of the effects to visually identify significant factors and interactions.

- Interpretation: A method is considered robust if no factor or interaction shows a statistically significant effect on critical responses at the chosen level of variation.

Table: Example 2³ Full Factorial Design Matrix for Robustness Testing of an HPLC Method

| Experiment Run | Flow Rate (mL/min) | Column Temp (°C) | %Organic | Response: Retention Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 (0.9) | -1 (33) | -1 (48) | 4.52 |

| 2 | +1 (1.1) | -1 (33) | -1 (48) | 4.48 |

| 3 | -1 (0.9) | +1 (37) | -1 (48) | 4.21 |

| 4 | +1 (1.1) | +1 (37) | -1 (48) | 4.19 |

| 5 | -1 (0.9) | -1 (33) | +1 (52) | 4.95 |

| 6 | +1 (1.1) | -1 (33) | +1 (52) | 4.91 |

| 7 | -1 (0.9) | +1 (37) | +1 (52) | 4.60 |

| 8 | +1 (1.1) | +1 (37) | +1 (52) | 4.58 |

Protocol for Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology (Central Composite Design)

This protocol is used after critical factors are known to model curvature and find a true optimum [40].

Objective: To build a quadratic model for the response surface and identify the factor levels that maximize or minimize the analytical response.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Select Factors: Choose 2 or 3 critical factors identified from prior screening experiments.

- Generate the Design Matrix: A Central Composite Design (CCD) is commonly used. It consists of:

- A factorial part (2^k points, from a full factorial).

- Center points (usually 3-6 replicates to estimate pure error).

- Axial (star) points (2k points) located at a distance ±α from the center, which allow for the estimation of curvature.

- Execute the Experiment: Run all experiments in a fully randomized order.

- Model Fitting and Analysis:

- Fit a second-order polynomial model to the data using regression analysis.

- Use ANOVA to check the significance and adequacy of the model.

- Analyze contour plots and 3D response surface plots to visualize the relationship between factors and the response.

- Optimization and Validation: Use the fitted model to locate the optimal conditions. Conduct confirmatory experiments at the predicted optimum to validate the model's accuracy.

Table: Comparison of Common Response Surface Designs

| Design Type | Number of Runs for k=3 Factors | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Composite (CCD) | 15 - 20 | Highly efficient; provides excellent estimation of quadratic effects; rotatable or nearly rotatable [40]. | General-purpose optimization when the experimental region is not highly constrained. |

| Box-Behnken | 15 | Requires fewer runs than CCD for the same factors; all points lie within a safe operating region (no extreme axial points) [12]. | Optimization when staying within safe factor boundaries is a priority. |

| Three-Level Full Factorial | 27 (for k=3) | Comprehensive data; can model all quadratic and interaction effects directly [41]. | When a very detailed model is needed and resources are not limited. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Robustness Testing of Inorganic Analytical Methods

| Item | Function in Experiment | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Materials | Serves as a calibration standard with a known, traceable concentration to ensure analytical accuracy [13]. | Critical for quantifying elements in ICP-MS and ensuring method validity during parameter variations. |

| Certified Mobile Phase Reagents | Used as solvents in chromatographic separations (IC). Their purity and pH are critical factors in robustness [1]. | Use HPLC or MS-grade solvents. Variations in lot-to-lot purity can be a source of ruggedness issues. |

| Internal Standard Solutions | A known amount of a non-interfering element/compound added to samples and standards to correct for instrument drift and matrix effects [13]. | Essential for maintaining data integrity in ICP-MS during robustness testing when parameters fluctuate. |

| Different Batches/Columns | Used to test the method's sensitivity to the specific brand or batch of the consumable [1]. | A key test for ruggedness; a robust method should perform consistently across different columns from the same manufacturer. |

| Buffer Salts & pH Standards | Used to prepare mobile phases with precise pH, a parameter often tested in robustness studies [1]. | Use high-purity salts and regularly calibrate pH meters to ensure the accuracy of this critical parameter. |

Workflow Visualization for Experimental Optimization

The diagram below outlines the strategic workflow for moving from screening to optimization and final robustness validation.

Strategic Path for Analytical Method Optimization

Establishing System Suitability Criteria from Robustness Data

Frequently Asked Questions