Bridging Scales: A Comprehensive Framework for Benchmarking In Situ TEM Data with Molecular Dynamics Simulations

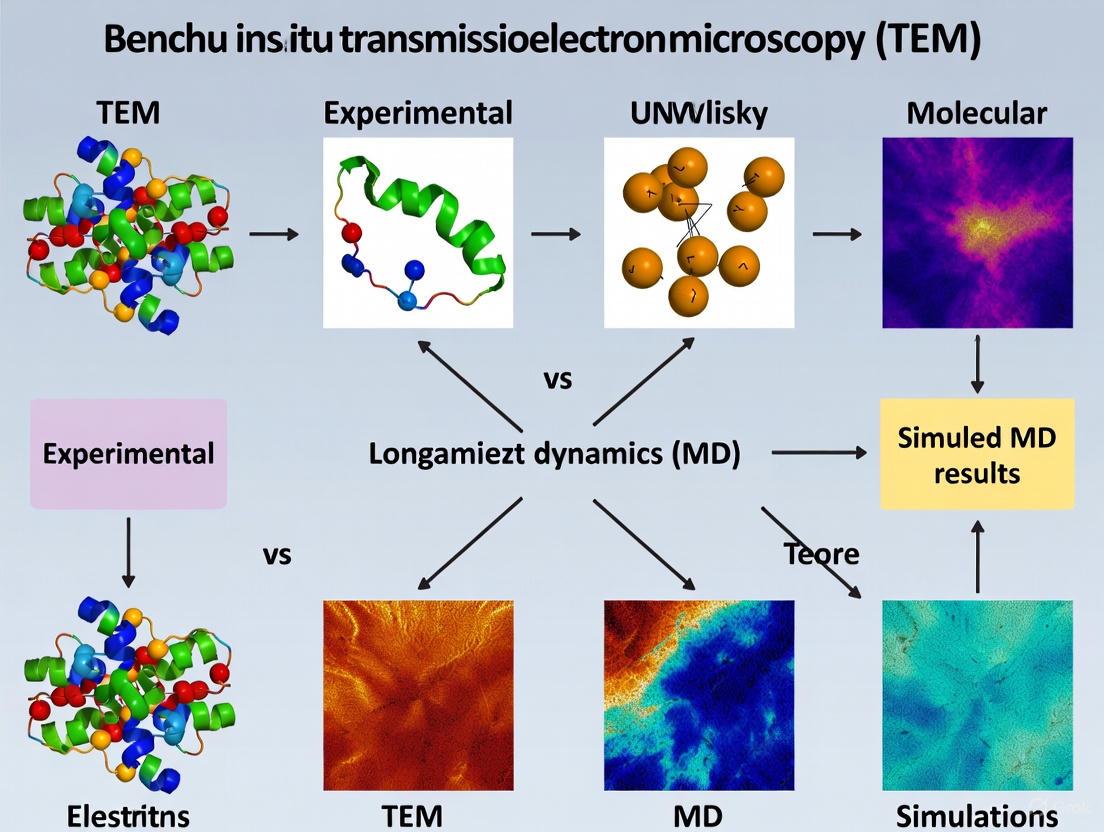

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and scientists on the integrated use of in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Bridging Scales: A Comprehensive Framework for Benchmarking In Situ TEM Data with Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and scientists on the integrated use of in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. It covers the foundational principles of both techniques, outlines robust methodological workflows for coupled experiments, addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies, and establishes rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from recent literature, we present a framework for cross-validating nanoscale observations with atomic-scale simulations, enhancing the reliability of structure-property relationships in materials science and nanotechnology.

Understanding the Synergy: Core Principles of In Situ TEM and MD Simulations

In the evolving landscape of (S)TEM, in situ and operando characterization have emerged as powerful methodologies for investigating material behaviors under dynamic conditions, moving beyond static, high-resolution imaging. These techniques are pivotal for a thesis focused on benchmarking in situ TEM data against molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, as they provide the crucial experimental footage against which computational models are validated. The fundamental distinction between these two terms is not merely semantic but defines the nature and interpretative power of the experiment. In situ (S)TEM broadly refers to the observation of a sample subjected to an external stimulus—such as heat, electrical bias, or a liquid/gas environment—within the microscope, enabling real-time visualization of dynamic processes like nanoparticle growth or defect migration. [1] [2] In contrast, operando (S)TEM is a more specific subset of in situ experiments, defined by the simultaneous collection of (S)TEM data and quantitative performance metrics of the material or device under study. [1] [3] This direct correlation allows researchers to establish definitive structure-property relationships, for instance, by observing the structural evolution of a catalyst nanoparticle while simultaneously measuring its catalytic activity and selectivity. [1]

The drive towards operando conditions is a central theme in modern microscopy, reflecting the scientific community's pursuit of relevance and translatability. While in situ techniques offer unparalleled views of nanoscale dynamics, operando methods ensure that these observations are made under conditions that closely mimic the material's real-world operation, thereby strengthening the conclusions drawn. [2] [3] This is particularly critical when using TEM data to benchmark MD simulations. Accurate simulations must replicate not only the structural outcomes but also the functional performance and kinetic pathways observed in controlled experiments. The careful design of in situ and operando experiments, therefore, provides the essential, high-fidelity dataset required to refine interatomic potentials and validate the predictive power of computational models.

Comparative Analysis: Techniques, Applications, and Data

Core Conceptual Differences and Experimental Goals

The following table outlines the fundamental distinctions between in situ and operando characterization, which dictate their respective experimental designs and analytical outputs.

Table 1: Conceptual and Operational Differences between In Situ and Operando (S)TEM

| Aspect | In Situ (S)TEM | Operando (S)TEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Observation under applied stimulus or environment. [2] | Observation under working conditions with simultaneous performance measurement. [1] [3] |

| Primary Goal | To visualize dynamic structural, morphological, or chemical changes in real-time. [4] | To directly correlate nanoscale structure with macroscopic functional properties. [1] [2] |

| Typical Measurements | Imaging, diffraction, and spectroscopy (EDS/EELS) during stimulus. [4] [2] | All in situ measurements, plus quantitative activity, selectivity, or efficiency data. [1] |

| Data Output | Videos, image series, spectra showing evolution (e.g., nanoparticle coalescence). [5] | Correlated datasets (e.g., a catalyst's atomic structure plotted against its product yield over time). [1] |

| Relation to MD | Provides visual validation for simulated dynamics (e.g., defect migration). [6] | Provides a stricter benchmark for simulations that aim to predict both structure and function. |

Technical Implementations and Holder Technologies

The practical execution of in situ and operando (S)TEM experiments relies on specialized hardware that enables the application of external stimuli and environmental control. The market offers a diverse range of solutions, from universal holder-based systems to dedicated microscope column modifications. [7] [8]

Table 2: Overview of Common In Situ and Operando (S)TEM Techniques

| Technique | Stimulus/Environment | Key Applications | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ Heating | Temperatures up to >1000°C. [7] | Studying thermal stability, phase transformations, grain growth, and annealing processes. [4] | Observation of icosahedral AuNPs transforming into decahedral structures under electron beam irradiation. [5] |

| In Situ Gas Reaction | Flowing gas environment (e.g., O₂, H₂, CO₂) at elevated temperatures. [1] [7] | Catalysis research (e.g., CO oxidation, CO₂ hydrogenation), oxidation, and reduction kinetics. [1] | Atomic-scale observation of catalyst surface structure and active sites during NO reduction reactions. [1] |

| In Situ Liquid Cell | Liquid electrolyte environment. [7] | Electrochemical processes (e.g., battery cycling, electrocatalysis), nanoparticle growth, and biological studies. [4] | Real-time visualization of nucleation and growth pathways of 0D, 1D, and 2D nanomaterials. [4] |

| In Situ Electrochemical | Applied electrical bias within a liquid or gas cell. [1] | Battery and fuel cell research, electrocatalysis, and fundamental electrochemistry. [1] [4] | Correlating electrochemical current with structural changes in electrode materials during operation. |

| In Situ Mechanical | Applied mechanical stress (e.g., via nanoindentation). [6] | Studying deformation mechanisms, dislocation dynamics, fracture, and mechanical properties. [6] | Capturing real-time 〈c + a〉 dislocation and twinning activities in pure Mg during loading/unloading. [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Cutting-edge in situ and operando research is supported by a suite of specialized tools and reagents that enable precise environmental control and stimulus application.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Situ and Operando (S)TEM

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Application in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based Chips | Microelectromechanical systems that integrate tiny heaters, electrodes, or liquid/gas channels for sample holding and stimulus application. [8] | Universal platform for heating, electrical biasing, and liquid/gas cell experiments; enables high-resolution imaging. [7] |

| Environmental TEM (ETEM) | A modified microscope column that allows a continuous gas flow around the sample, creating a high-pressure gas environment. [1] [4] | Studying catalytic reactions and material degradation in gas atmospheres without the spatial constraints of a cell. |

| Graphene Liquid Cells | Sealed liquid pockets between graphene layers that minimize electron scattering and allow high-resolution imaging of solution-phase processes. [4] | Observing nucleation and growth of nanocrystals in their native liquid synthesis environment with near-atomic resolution. [4] |

| Electrochemical Flow Cells | Liquid cell holders that allow for continuous flow of fresh electrolyte, preventing product accumulation and mimicking industrial reactor conditions. [2] | Operando electrocatalysis studies, such as CO₂ reduction, where maintaining a consistent reactant concentration is critical. [2] [3] |

| Quantitative Gas Analysis | Mass spectrometry systems integrated with the TEM gas holder or outlet to quantitatively analyze reaction products. [1] | Essential for operando catalysis studies to measure catalyst activity and selectivity (e.g., during Fischer-Tropsch synthesis). [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Correlative and Benchmarking Studies

A Generalized Workflow for In Situ/Operando Experimentation

A robust in situ or operando study follows a structured workflow to ensure the collection of meaningful, high-quality data suitable for benchmarking simulations. The diagram below outlines this multi-stage process.

Diagram Title: Generalized Workflow for In Situ/Operando (S)TEM

Step 1: Experimental Design. The process begins by defining a clear scientific question, such as understanding the atomic-scale deformation mechanisms in a magnesium alloy. The choice between in situ and operando modes is determined by the research objective. For instance, to benchmark an MD simulation of defect dynamics, an in situ mechanical testing holder for nanoindentation would be selected. The key is to define the specific structural features (e.g., dislocation activity, twin boundary migration) that will be tracked and correlated with the applied stimulus (stress/strain). [6] [2]

Step 2: Sample Preparation. The sample must be prepared in a geometry compatible with the chosen holder. For a nanoindentation experiment, this typically involves a focused ion beam (FIB) lift-out to create an electron-transparent lamella with a specific orientation. The sample surface and thickness are critical, as they directly influence the observed mechanical behavior and image resolution. [6] [2]

Step 3: Data Acquisition. The stimulus is applied while simultaneously acquiring data. In the nanoindentation example, the indenter is driven into the sample at a controlled rate. Real-time imaging and recording (often at hundreds of frames per second) capture the dynamic defect activities. For this specific protocol, it is crucial to perform control experiments to account for electron beam effects, which can induce atypical defect mobility. [6] [5]

Step 4: Data Analytics. The terabyte-scale data generated from video recording requires sophisticated analysis. Machine learning algorithms and tracking software are employed to automatically identify and trace defects like dislocations and twin boundaries over time, extracting quantitative metrics such as velocity, strain fields, and interaction statistics. [6] [2]

Step 5: Benchmarking and Validation. The extracted quantitative data serves as the direct benchmark for MD simulations. For example, the observed critical stress for twin nucleation and the glide rate of 〈c + a〉 dislocations in magnesium are compared against the values predicted by the simulation. Discrepancies can lead to refinements in the interatomic potentials used in the model. [6]

Step 6: Iterative Refinement. The process is iterative. Initial comparisons between experiment and simulation may reveal the need for more specific in situ data or adjustments to the simulation setup, creating a feedback loop that progressively enhances the fidelity of both the experimental understanding and the computational model. [6]

Case Study: Protocol for Nanoparticle Dynamics under Gaseous Environment

This protocol details an experiment to study the sintering dynamics of catalyst nanoparticles under a gas atmosphere, relevant for benchmarking MD simulations of surface diffusion and coalescence.

1. Objective: To observe the coalescence and repulsion behavior of Au nanoparticles (NPs) under a reactive gas environment and electron beam irradiation, providing data to validate MD simulations of NP surface diffusion and interaction forces. [5]

2. Materials and Setup:

- Nanoparticles: Citrate-stabilized AuNPs of two size distributions (e.g., 5.9 nm and 11.0 nm). [5]

- Substrate: Ultrathin silicon nitride (SiNₓ) membrane.

- Holder: In situ gas reaction holder with a MEMS-based heater.

- Gas Environment: Flowing O₂ or H₂ gas at a pressure of a few millibars.

3. Experimental Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Drop-cast a dilute suspension of AuNPs onto the SiN₃ membrane and load it into the gas cell holder. [5]

- Baseline Imaging: Insert the holder into the TEM and locate pairs of NPs with small interparticle distances. Acquire high-resolution images to determine initial structure and faceting.

- Stimulus Application: Introduce the gas and set the heater to the target temperature (e.g., 400°C). Simultaneously, expose the NP pairs to a controlled electron beam dose rate (e.g., from 1.2 × 10⁵ e⁻ Å⁻² s⁻¹). [5]

- Data Collection: Record a time-series of images or a video to track the particle motion, structural transformation, and eventual coalescence or repulsion. It is critical to systematically vary the beam dose rate and particle size to understand their influence on the dynamics. [5]

4. Data Analysis:

- Use image analysis software to measure the interparticle distance (dᵣ) and diffusion rate over time for different NP sizes and beam conditions. [5]

- Classify the observed dynamic processes: coalescence, repulsion, or sequential attraction-repulsion. [5]

5. Benchmarking with MD:

- The experimental metrics (diffusion coefficients, coalescence initiation distance, and final NP morphology) serve as direct inputs and validation points for MD simulations of the same process.

- The simulation can help explain the atomic-scale mechanisms behind phenomena like beam-induced repulsion, which may be driven by electrostatic charging or surface atom sputtering. [5]

Integrating Experimental Data with Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The synergy between in situ/(S) TEM and MD simulations is a cornerstone of modern materials science. This integration creates a closed-loop workflow for discovery and validation, as illustrated below.

Diagram Title: Integration Loop Between TEM and MD Simulations

From Experiment to Simulation: In situ TEM provides the critical real-space footage of material dynamics. A prime example is the study of deformation in magnesium. In situ nanoindentation experiments can capture the nucleation and glide of 〈c + a〉 dislocations—a complex process difficult to simulate from first principles alone. The experimental observation that the edge components of these dislocations become sessile while the screw components glide continuously provides a specific, quantitative phenomenon for MD simulations to replicate and explain at the atomic level. [6] Furthermore, the finding that the plastic zone in Mg is well-defined, unlike in FCC metals, offers a key topological constraint for simulations. [6]

From Simulation to Experiment: MD simulations reciprocate by revealing underlying mechanisms and guiding new experiments. In the same Mg study, MD simulations were able to investigate the early stages of indentation, revealing that a specific stacking fault bounded with a Frank loop can serve as a nucleation source for the 〈c + a〉 dislocations observed experimentally. [6] This atomic-level insight, gleaned from simulation, can direct the experimentalist to focus their in situ observations on the very initial moments of plastic deformation, searching for visual evidence of these nucleation sites.

This iterative dialogue ensures that MD models are grounded in physical reality while empowering TEM experiments to probe deeper, more specific questions. The ultimate output is a validated predictive model that can accurately forecast material behavior under a wide range of conditions, significantly accelerating the design of new materials with tailored properties.

The Role of Molecular Dynamics in Modeling Atomic-Scale Mechanisms

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in materials science, providing atomic-resolution insights into complex physical and chemical processes. Their true power is unlocked when rigorously benchmarked against and validated by experimental data, particularly from high-resolution techniques like in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). This guide explores the role of MD in modeling atomic-scale mechanisms, objectively comparing its performance against alternative computational and experimental methods within a framework designed for benchmarking against in situ TEM data.

Molecular Dynamics is a computational technique that simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, MD tracks the evolution of atomic trajectories, providing insights into dynamic processes and non-equilibrium phenomena [9]. The core of any MD simulation is the interatomic potential, a mathematical function that quantifies the interactions between atoms. The accuracy of this potential directly determines the reliability of the simulation results [9].

Modern MD implementations like LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) leverage robust parallel computing capabilities to simulate large-scale systems encompassing millions of atoms [9]. This scalability makes MD particularly suitable for investigating nanoscale phenomena such as radiation damage, crystal growth, and defect dynamics—processes that are often accessible to in situ TEM observation.

MD Workflow and Integration with Experimental Benchmarking

The process of integrating MD simulations with experimental validation, particularly using in situ TEM, follows a structured workflow that ensures the computational models accurately reflect real-world physical mechanisms.

The Integrated MD and Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the cyclical process of developing and validating MD simulations against experimental data.

This workflow begins with experimental observation, often from in situ TEM, which identifies a particular nanoscale phenomenon. Researchers then set up MD simulations to probe the atomic-scale mechanisms behind this phenomenon. The critical step of interatomic potential selection determines the forces between atoms. The simulation results are then validated against experimental data; agreement confirms the proposed mechanism, while disagreement necessitates model refinement, creating an iterative cycle that progressively enhances the simulation's accuracy [10].

Comparative Analysis of MD and Alternative Methods

To objectively evaluate MD's performance, it is essential to compare its capabilities, accuracy, and computational requirements against other prevalent techniques in atomic-scale modeling.

Quantitative Comparison of Atomic-Scale Modeling Techniques

Table 1: Performance comparison of molecular dynamics with other computational methods.

| Method | Key Principles | System Size | Time Scale | Key Strengths | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Numerical solution of Newton's equations of motion [9] | ~10^6-10^9 atoms [10] | Nanoseconds to microseconds [10] | Captures dynamic processes and non-equilibrium phenomena [9] | Limited by time step (femtoseconds); empirical potential accuracy [10] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Quantum mechanical treatment of electron density [10] | ~100-1000 atoms [10] | Static calculations or picoseconds | High electronic structure accuracy; predicts chemical reactions [10] | Computationally prohibitive for large systems and long time scales [10] |

| Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIP) | ML-based potential with near-DFT accuracy [10] | Comparable to MD [10] | Comparable to MD [10] | Near-DFT accuracy with MD scalability; excellent transferability [10] | Requires extensive training data; complex training process [10] |

| Monte Carlo (MC) Simulations | Random sampling to explore thermodynamic properties [9] | Comparable to MD | Not applicable | Suitable for equilibrium states and phase transitions [9] | Limited information about dynamics and kinetic pathways [9] |

Case Study: MD vs. MLIP for Platinum-Graphene Interfaces

A recent study investigating platinum crystal growth on graphene for hydrogen sensing applications provides an excellent benchmark for comparing traditional MD approaches with emerging MLIP methods [10].

Researchers developed a high-fidelity equivariant machine-learned interatomic potential to perform large-scale MD simulations with near-DFT accuracy [10]. When simulating Pt nucleation on graphene, the MLIP achieved an impressive energy mean absolute error of less than 9 meV/atom and forces MAE below 75 meV/Å [10]. The MLIP-enabled MD simulations successfully captured key growth stages—including Pt nucleation, coalescence, and the formation of either polycrystalline clusters or epitaxial thin films—under varying deposition conditions [10].

These computational predictions were validated against TEM and Raman measurements, showing that "at lower Pt loadings the structures consist predominantly of small approximately spherical clusters, which transition to slightly thicker, more planar domains as Pt loading increases" [10]. This agreement between simulation and experiment demonstrates how MLIP-enhanced MD can achieve near-DFT accuracy while accessing the length and time scales relevant to experimental observations.

Benchmarking MD Against In Situ TEM Data

In situ TEM with ion irradiation represents a powerful experimental technique for directly observing radiation effects in materials, providing ideal data for benchmarking MD simulations [11]. These instruments allow researchers to observe microstructural evolution in real-time under controlled irradiation conditions at the nanoscale [11].

Case Study: Hydrogen Retention in Fusion Materials

MD simulations have proven particularly valuable in studying hydrogen retention in reduced activation ferritic-martensitic steels, candidate structural materials for future fusion reactors [12]. Researchers used MD to evaluate hydrogen retention effects of faceted helium bubbles in body-centered cubic iron, revealing that bubble morphology significantly influences trapping capacity [12].

The simulations showed that "faceted bubbles with more stable configurations would exhibit 10∼20 % lower H retention amount than the spherical bubble with equal volume," despite having larger surface areas [12]. This counterintuitive finding demonstrates MD's ability to reveal atomic-scale mechanisms that might not be apparent from experimental observation alone. The MD approach also identified that "stress distribution on faceted He bubble surface leads to uneven distributions of trapped H atoms" [12], providing atomistic insights that complement TEM observations of bubble structures.

Experimental Protocols for MD Benchmarking

To ensure meaningful comparisons between MD simulations and experimental data, researchers should follow established protocols for both computational and experimental approaches.

MD Simulation Protocol for Radiation Damage Studies

The following protocol is adapted from studies of hydrogen retention in materials [12]:

- System Setup: Create a simulation cell with the appropriate crystal structure (e.g., BCC for iron) and dimensions sufficient to accommodate the defect structures being studied.

- Potential Selection: Choose appropriate interatomic potentials. For example, studies on iron might use an EAM potential for Fe-Fe interactions, with specific potentials for Fe-He and Fe-H interactions [12].

- Defect Introduction: Introduce specific defect structures, such as helium bubbles with controlled morphology (spherical vs. faceted with {100} and {110} planes) [12].

- Equilibration: Perform equilibration runs in the appropriate ensemble (NVT or NPT) at the target temperature (e.g., 973 K for fusion-relevant conditions) [12].

- Production Run: Execute the main simulation for sufficient time (e.g., 3.0 ns) to observe the phenomenon of interest [12].

- Analysis: Calculate relevant metrics such as cumulative distribution functions to determine trapping amounts and energies [12].

In Situ TEM with Ion Irradiation Protocol

For benchmarking MD simulations of radiation effects, in situ TEM with ion irradiation provides direct experimental validation [11]:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare electron-transparent samples of the material of interest using focused ion beam milling or electropolishing.

- Irradiation Setup: Mount the sample in a specialized holder capable of in situ ion irradiation while under TEM observation [11].

- Experimental Parameters: Select appropriate irradiation conditions (ion species, energy, flux, and temperature) to match the phenomena being simulated [11].

- Simultaneous Characterization: Perform TEM characterization (imaging, diffraction, spectroscopy) during irradiation to monitor microstructural evolution in real-time [11].

- Data Correlation: Compare the observed microstructural features (defect formation, bubble morphology, phase transformations) with MD predictions [11].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful integration of MD simulations with experimental benchmarking requires specific computational and experimental tools. The table below details key resources in this interdisciplinary field.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and tools for MD and in situ TEM studies.

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) [9] | Enables large-scale MD simulations with robust parallel computing capabilities [9] |

| Interatomic Potentials | EAM (Embedded Atom Method) [9] | Potential energy model for metallic systems accounting for multi-body interactions [9] |

| Interatomic Potentials | Tersoff Potential [9] | Empirical interatomic potential for covalent materials like silicon and carbon [9] |

| Experimental Facilities | In Situ TEM with Ion Irradiation [11] | Enables real-time observation of material response to irradiation at nanoscale [11] |

| Analysis Framework | Common Neighborhood Analysis [9] | Method for identifying local atomic structures and crystal types in MD simulations [9] |

| Validation Techniques | TEM and Raman Spectroscopy [10] | Experimental methods for validating predicted morphologies and structural changes [10] |

Molecular Dynamics simulations serve as a powerful bridge between quantum-scale accuracy and experimental-scale phenomena in materials science. When rigorously benchmarked against in situ TEM data, MD provides unparalleled insights into atomic-scale mechanisms across diverse fields—from hydrogen sensing in platinum-functionalized graphene to radiation damage in nuclear materials [10] [12]. The continuing development of machine-learned interatomic potentials promises to further enhance MD's accuracy while maintaining its ability to simulate experimentally relevant length and time scales [10]. As both computational and experimental techniques advance, this synergistic approach will increasingly drive the design and understanding of next-generation materials.

In the realm of modern scientific research, particularly in fields like materials science and structural biology, two powerful techniques offer unique windows into the behavior of matter: direct observation via in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and atomic-level prediction through Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. In situ TEM provides real-time, direct observation of dynamic processes at the nanoscale or atomic level under controlled conditions, such as heating, cooling, or mechanical stress [13] [14]. Meanwhile, MD simulations utilize computational methods to probe the dynamical properties of atomistic systems, providing a "virtual molecular microscope" that reveals the hidden atomistic details underlying material and biomolecular motions [15]. While each technique operates on fundamentally different principles—one empirical, the other computational—their combination creates a powerful synergistic relationship that enables researchers to overcome the inherent limitations of each method when used in isolation.

The integration of these approaches is becoming increasingly critical for advancing research in semiconductor development, life sciences, novel materials design, and drug discovery. As in situ TEM markets expand, projected to reach approximately $850 million by 2025 with a robust 12.5% CAGR [13], and as MD simulations continue to improve in accuracy and scope, understanding how to effectively benchmark and combine these methodologies has become a essential skill for researchers. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these techniques, offering experimental data, methodological protocols, and visualization tools to help scientists maximize their research potential through the strategic integration of direct observation and atomic-level prediction.

Technical Comparison: Capabilities and Limitations

Core Characteristics Comparison

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Direct Observation and Atomic-Level Prediction

| Feature | In Situ TEM (Direct Observation) | Molecular Dynamics (Atomic-Level Prediction) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Real-time imaging using electron beam-sample interactions [13] | Numerical solution of Newton's equations of motion for atoms [15] |

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic-scale (sub-nanometer) [16] | Atomic-scale (explicit atom positions) [15] |

| Temporal Capabilities | Real-time processes (milliseconds to hours) [13] | Picoseconds to microseconds typically [15] |

| Experimental Environment | Controlled stimuli (heating, cooling, gas, liquid) [13] [14] | Controlled simulation conditions (NPT, NVT ensembles) [17] |

| Sample Requirements | Electron-transparent thin samples; may require special holders [13] | Atomic coordinates; force field parameters [15] |

| Primary Output | Images, spectra (real-space information) [6] | Trajectories, energy data (configurational sampling) [15] |

| Key Strengths | Direct visualization; no model assumptions; real environment | Complete atomic detail; mechanistic insights; no instrument limitations |

| Inherent Limitations | Radiation damage; sample preparation complexity; projection artifacts | Sampling limitations; force field inaccuracies; timescale restrictions |

Performance Benchmarking and Applications

Table 2: Experimental Performance Benchmarks and Application Suitability

| Parameter | In Situ TEM | Molecular Dynamics |

|---|---|---|

| Timescale Range | Milliseconds to hours [13] | Femtoseconds to microseconds [15] |

| Temperature Control | -180°C to 1500°C+ [13] | Typically 0K to 500K+ (depending on method) [15] |

| Structural Accuracy | Direct measurement (spatial res. ~0.1nm) [16] | Force field-dependent (0.1-2Å RMSD from experimental structures) [15] [17] |

| Quantitative Metrics | Dislocation dynamics, phase transformations [6] | Order parameters (S²), RMSD, energy values [17] |

| Optimal Applications | Nanoscale dynamics, defect propagation, reaction monitoring [6] | Atomistic mechanisms, folding pathways, subtle conformational changes [15] |

| Validation Approach | Direct empirical evidence [6] | Comparison with experimental observables [15] |

| Primary Research Fields | Materials science, semiconductor research, life sciences [13] | Structural biology, drug design, materials science [15] [17] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated Workflow for Combined Analysis

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1In SituTEM Nanoindentation Protocol

The in situ TEM nanoindentation method enables direct observation of deformation mechanisms in materials at the nanoscale. Based on studies of defect dynamics in magnesium, the protocol involves:

Sample Preparation: Begin with preparing an electron-transparent thin sample of the material of interest. For metals like magnesium, this typically involves mechanical thinning followed by ion milling to achieve appropriate electron transparency. The sample must be oriented to favor specific crystallographic directions for observing deformation processes of interest [6].

Experimental Setup: Mount specialized in situ TEM nanoindentation holders capable of applying controlled mechanical forces. These holders incorporate piezoelectric actuators for precise displacement control and force sensors. Calibrate the indentation parameters based on material properties, typically using diamond indenter tips with tip radii ranging from 50-500 nm depending on the spatial resolution required [6].

Data Acquisition: Perform indentation experiments during TEM observation at appropriate accelerating voltages (typically 200-300 kV for metals). Record real-time videos at frame rates sufficient to capture the dynamics of interest (often 10-30 frames per second). For dislocation and twinning studies in magnesium, focus on capturing the nucleation, propagation, and interaction of defects during both loading and unloading cycles. Utilize diffraction contrast imaging conditions to enhance defect visibility [6].

Data Analysis: Analyze recorded sequences to quantify defect dynamics, including dislocation velocities, nucleation stresses, and twin boundary migration rates. Correlate mechanical response (load-displacement data) with observed deformation mechanisms. For the magnesium study, this revealed continuous glide of screw components of 〈c + a〉 dislocations while edge components became sessile during loading, with intermittent twin tip propagation but more continuous twin boundary migration [6].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

Molecular Dynamics simulations provide atomic-level insights into the mechanisms observed experimentally. The protocol for simulating nanoindentation or protein dynamics involves:

System Setup: Obtain initial atomic coordinates from experimental structures (e.g., Protein Data Bank for proteins or crystallographic data for materials). For the TEM-1 β-lactamase study, initial coordinates came from the 1XPD structure at 1.9 Å resolution. For magnesium nanoindentation, create a simulation cell with appropriate crystallographic orientation matching experimental conditions. Solvate the system with explicit water molecules in a periodic boundary box extending 10 Å beyond any protein or material atom [17] [15].

Force Field Selection: Choose appropriate force fields based on the system. For proteins, options include CHARMM22/CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, or Levitt et al. force fields. For materials, select specialized force fields parameterized for metallic systems. The choice significantly impacts results, as different force fields can produce distinct conformational distributions even when reproducing experimental observables equally well overall [15] [17].

Simulation Execution: Perform energy minimization in stages, first relaxing solvent atoms with protein restraints, then relaxing the entire system. Equilibrate the system with position restraints on protein or material heavy atoms, gradually releasing restraints. Conduct production simulations using appropriate ensembles (NPT for constant pressure, NVT for constant volume). For nanoindentation simulations, incorporate a virtual indenter represented by a repulsive potential. For the magnesium study, simulations revealed that I1 stacking faults bounded with 〈1/2c+p〉 Frank loops generated from the plastic zone could serve as nucleation sources for 〈c + a〉 dislocations observed experimentally [6] [15].

Analysis Methods: Calculate relevant observables for comparison with experimental data. For protein dynamics, compute order parameters (S²) from MD trajectories and compare with NMR-derived parameters. For nanoindentation, analyze defect nucleation, stress distributions, and atomic-scale deformation mechanisms. Utilize multiple trajectories (typically 3+ replicates of 20-200 ns each) to improve sampling and statistical significance [17] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Their Functions

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Benefit | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| In Situ TEM Holders | Enable controlled stimuli during imaging (heating, cooling, liquid, gas, mechanical testing) [13] | Studying material behavior at high temperatures, biological processes in liquid, catalytic reactions [13] |

| Specialized Force Fields | Mathematical descriptions of atomic interactions governing MD simulation accuracy [15] | Protein folding (AMBER ff99SB-ILDN), lipid membranes (CHARMM36), materials (embedded atom method) [15] |

| Cryo-EM Preparation Systems | Prepare vitrified biological samples preserving native state [13] | Structural biology, cellular tomography, single-particle analysis [13] |

| Explicit Solvent Models | Represent water environment in MD simulations (TIP3P, TIP4P-EW, SPC/E) [15] | Solvation effects on protein dynamics, ion solvation, biomolecular recognition [15] |

| Electron Detectors | High-sensitivity cameras for recording TEM images with minimal electron dose [14] | Radiation-sensitive materials, biological specimens, high-temporal resolution imaging [14] |

| Analysis Software | Process and quantify experimental and simulation data (TEM image analysis, MD trajectory analysis) [17] | Dislocation tracking, order parameter calculation, free energy estimation [17] |

Case Study: Integrated Analysis of Magnesium Deformation

A compelling example of the complementary strengths of direct observation and atomic-level prediction comes from research on deformation mechanisms in pure magnesium. The study combined in situ TEM nanoindentation with Molecular Dynamics simulations to uncover defect dynamics that would be difficult to fully characterize using either method alone [6].

The in situ TEM observations captured real-time 〈c + a〉 dislocation and twinning activities during loading and unloading cycles. Direct visualization revealed that the screw component of 〈c + a〉 dislocations glided continuously, while the edge components rapidly became sessile during loading. Twin tip propagation occurred intermittently, while twin boundary migration was more continuous. During unloading, elastic strain relaxation caused both 〈c + a〉 dislocation retraction and detwinning. The plastic zone comprised of 〈c + a〉 dislocations in magnesium was well-defined, contrasting with the diffused plastic zones observed in face-centered cubic metals under similar conditions [6].

Complementary MD simulations provided atomic-level insights into the formation and evolution of these deformation-induced crystallographic defects at the early stages of indentation. Simulations revealed that, in addition to 〈a〉 dislocations, I1 stacking faults bounded with 〈1/2c+p〉 Frank loops could be generated from the plastic zone ahead of the indenter, potentially serving as nucleation sources for the abundant 〈c + a〉 dislocations observed experimentally. This atomic-level prediction provided the mechanistic understanding behind the experimental observations, demonstrating how specific defect configurations lead to the macroscopic deformation behavior [6].

The synergy between these techniques extended beyond simple validation. The MD simulations suggested nucleation mechanisms that could inform future in situ TEM experiments with specific crystallographic orientations or temperature conditions to test these predictions. This iterative refinement process exemplifies the powerful feedback loop possible when combining direct observation with atomic-level prediction.

The complementary strengths of direct observation via in situ TEM and atomic-level prediction through MD simulations create a powerful framework for advancing materials science, structural biology, and drug development. In situ TEM provides ground-truth validation of dynamic processes under realistic conditions, while MD simulations offer complete atomic-level mechanistic insights without instrumental limitations. The strategic integration of these approaches, as demonstrated in the magnesium deformation study, enables researchers to overcome the inherent limitations of each technique when used in isolation.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the practical implications are significant. Combining these methods can accelerate the understanding of material deformation mechanisms, protein function and dynamics, drug-target interactions, and catalytic processes. As both technologies continue to advance—with in situ TEM achieving higher temporal and spatial resolution, and MD simulations accessing longer timescales through improved algorithms and computing power—their synergistic relationship will become increasingly important for tackling complex scientific challenges at the frontiers of nanotechnology, biotechnology, and materials design.

The Generalized Planar Fault Energy (GPFE) curve serves as a fundamental theoretical framework for predicting and understanding deformation mechanisms in crystalline materials. This energy landscape describes the pathway and associated energy barriers for shearing atomic planes, effectively modeling the nucleation of planar defects such as stacking faults and deformation twins [18]. In the context of face-centered cubic (FCC) metals, the GPFE theory provides critical parameters for evaluating a material's propensity for dislocation slip (DS) versus deformation twinning (DT), a crucial determinant of mechanical properties including strength, ductility, and toughness [19].

The integration of in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) experiments with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations has established a powerful paradigm for validating and refining GPFE-based models. This benchmarking approach allows researchers to directly correlate theoretical energy landscapes with real-time, atomic-scale deformation events, creating a closed loop between prediction and experimental observation [18] [20]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, detailing experimental protocols, computational approaches, and their synergistic application in advancing our understanding of defect evolution in metallic systems.

Theoretical Foundations: The GPFE Energy Landscape

Key Parameters of the GPFE Curve

The GPFE curve maps the energy evolution as successive atomic layers are sheared along a specific crystallographic direction. This landscape features several critical points that define material deformability [18] [20]:

- Unstable Stacking Fault Energy (γusf): The energy barrier for creating a unstable stacking fault.

- Intrinsic Stacking Fault Energy (γisf): The energy of a stable intrinsic stacking fault.

- Unstable Twinning Fault Energy (γutf): The energy barrier for twin nucleation.

- Twinning Fault Energy (γtf): The energy of a stable twinning fault.

Table 1: Key Energy Parameters from GPFE Curves for Selected FCC Metals

| Material | γusf (mJ/m²) | γisf (mJ/m²) | γutf (mJ/m²) | γtf (mJ/m²) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | ~180-200 | ~120-150 | ~210-230 | ~20-30 | [18] |

| Copper | ~170-190 | ~40-70 | ~200-220 | ~10-20 | [21] |

| Nickel | ~300-320 | ~120-140 | ~330-350 | ~40-60 | [21] |

From GPFE to Mechanical Behavior

The relationship between GPFE parameters and deformation mechanisms can be quantified through parameters such as the Q-factor, which evaluates the competition between dislocation slip and deformation twinning by comparing the stresses required to activate each mechanism [19]. This approach incorporates not only intrinsic material properties but also external parameters including loading direction and sample size, enabling more accurate predictions of deformation behavior in nanostructured materials.

For nanocrystalline aluminum alloys, GPFE tuning through alloying elements (Zr, Fe, Y) has enabled deformation twinning in grains of 20-40 nm diameter—a phenomenon rarely observed in coarse-grained Al due to its high intrinsic stacking fault energy (~166 mJ/m²) [22]. This demonstrates the critical role of GPFE manipulation in achieving extraordinary strength-ductility synergy in advanced alloys.

Experimental Validation: In Situ TEM Methodologies

Protocol for In Situ TEM Tensile Testing

The experimental validation of GPFE theories relies on sophisticated in situ TEM tensile testing, which simultaneously captures mechanical response and structural evolution [18] [20]:

Sample Preparation: Single-crystalline, defect-free Al nanowires (100-200 nm diameter, 5-20 μm length) with specific crystallographic orientations (<110>) are grown via stress-induced methods on SiO₂ substrates.

Sample Mounting:

- One end of the nanowire is attached to a tungsten tip via e-beam assisted Pt deposition

- The nanowire is welded to upper and lower jigs of a push-to-pull (PTP) device

- Precise alignment ensures the long axis parallels the tensile direction

Mechanical Testing:

- The PTP device is mounted to a picoindenter capable of measuring load and displacement

- Tensile tests are conducted at initial strain rates of 1.2 × 10⁻³ s⁻¹ at ambient temperature

- Load-displacement data is recorded while simultaneously capturing real-time microstructure evolution

Data Analysis: The dissipated energy associated with deformation twinning is extracted from stress-strain curves and converted to twin formation energy for comparison with theoretical GPFE predictions.

Figure 1: Workflow for in situ TEM tensile testing and GPFE validation

Quantitative Comparison of Experimental vs. Theoretical Results

Table 2: Comparison of Twin Formation Energies from Different Methodologies

| Methodology | Twin Formation Energy (mJ/m²) | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Calculations | ~20-30 (for Al) | High accuracy for perfect crystals; No empirical parameters | Limited to small system sizes (∼100-200 atoms); 0K temperature |

| MD Simulations | ~25-35 (for Al) | Can model temperature effects, larger systems | Limited by empirical potentials; Timescale restrictions |

| In Situ TEM Testing | ~25-40 (for Al) | Direct experimental observation; Real defect dynamics | Complex sample preparation; Surface oxide effects |

The synergy between these approaches is exemplified in studies where in situ TEM observations of Al nanowires confirmed theoretical predictions that <110> tensile orientation promotes deformation twinning, validating the size-dependent competition between dislocation slip and twinning derived from GPFE analysis [19].

Computational Approaches: Molecular Dynamics Simulations

MD Protocols for Defect Evolution Analysis

Molecular dynamics simulations provide atomic-scale insights into defect nucleation and evolution, complementing experimental observations:

System Setup:

- FCC metal systems (Al, Cu, Ni) with specific crystallographic orientations

- Simulation cells ranging from 100,000 to several million atoms

- Periodic boundary conditions applied in relevant directions

Potential Selection:

Deformation Protocols:

- Tensile loading at constant strain rate (typically 10⁸-10⁹ s⁻¹)

- Temperature control via thermostat algorithms (Nose-Hoover, Langevin)

- Analysis of dislocation nucleation, motion, and interaction

Defect Identification:

- Common neighbor analysis (CNA) for crystal structure identification

- Dislocation analysis algorithm (DXA) for defect characterization

- Visualization of stacking faults, twin boundaries, and partial dislocations

Advanced Sampling Methods

The Projected Average Force Integrator (PAFI) method enables calculation of temperature-dependent generalized stacking fault free energy (GSFFE) profiles, extending beyond the 0K limitations of standard GSFE calculations [21]. This approach:

- Utilizes the minimum energy path (MEP) from nudged elastic band (NEB) calculations as a reaction coordinate

- Performs constrained sampling on hyperplanes perpendicular to MEP

- Extracts the minimum free energy path (MFEP) at specific temperatures

- Accounts for anharmonic thermal vibrations without approximations

For FCC Cu, PAFI-GSFFE calculations demonstrate that temperature increases facilitate dislocation nucleation by reducing both unstable stacking fault energies and the gradient of GSFFE curves [21].

Integrated Workflow: Benchmarking In Situ TEM Against MD Simulations

The convergence of experimental and computational approaches establishes a robust framework for validating GPFE theories and defect evolution models:

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for benchmarking MD simulations against in situ TEM data

Case Study: Deformation Twinning in Nanocrystalline Aluminum

The synergistic application of these methodologies is exemplified in studies of deformation twinning in nanocrystalline Al alloys [22]:

Initial DFT Calculations: Predicted that alloying Al-Mg with Zr, Fe, or Y would tune GPFEs to enable deformation twinning.

MD Simulations: Modeled partial dislocation nucleation and propagation in nanocrystalline structures with grain sizes of 20-40 nm.

Experimental Validation: Mechanical alloying produced Al-8.5Mg-1X (X=Zr, Fe, Y) alloys, with atom probe tomography confirming solute dissolution.

In Situ Characterization: TEM observations revealed uniplanar twinning accompanied by grain rotations in 20-40 nm grains, replacing conventional multiplanar twinning.

Model Refinement: Critical resolved shear stress (CRSS) equations were applied to quantify the nucleation of full and partial dislocations, explaining the grain-size-dependent twinning behavior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for GPFE and Defect Evolution Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal Powders | Fabrication of nanocrystalline alloys via mechanical alloying | Al, Mg, Zr, Fe, Y (purity > 99.9%) [22] |

| Methyltrichlorosilane (MTS) | Chemical vapor infiltration of SiC matrix for composite materials | CH₃SiCl₃ precursor for β-SiC deposition [23] |

| Propylene (C₃H₆) | Pyrolytic carbon interphase deposition | Carbon source for interphase in SiC/SiC composites [23] |

| Projector Augmented Wave Pseudopotentials | First-principles DFT calculations of GPFE curves | Implemented in VASP for fault energy calculations [18] [20] |

| Embedded Atom Method (EAM) Potentials | MD simulations of metallic systems | Parameterized for specific metals (Cu, Al, Ni) [21] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | High-accuracy MD simulations with near-DFT fidelity | PACE (Performant Atomic Cluster Expansion) for Cu [21] |

| Push-to-Pull (PTP) Devices | In situ TEM tensile testing | Converts compressive force to tensile loading [18] [20] |

The integration of GPFE theory with advanced experimental and computational methodologies has created a robust framework for predicting and validating defect evolution in crystalline materials. The benchmarking of in situ TEM observations against MD simulations establishes a closed feedback loop that continuously refines theoretical models and computational approaches. This synergistic methodology has enabled precise manipulation of deformation mechanisms in metallic systems, as demonstrated by the activation of deformation twinning in traditionally non-twinnable aluminum alloys through strategic GPFE tuning.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on enhancing the temporal and spatial resolution of in situ characterization techniques, improving the accuracy and transferability of machine learning potentials for MD simulations, and extending GPFE analysis to more complex material systems including high-entropy alloys and multiphase composites. The continued convergence of these pathways will further solidify GPFE as a foundational framework for defect engineering and advanced materials design.

Executing Integrated Workflows: From Sample Preparation to Data Acquisition

In materials science and biological research, the fidelity of data obtained from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is paramount. The process of sample preparation, especially for specific geometries like nanowires or site-specific phases, directly influences the quality of this data and, consequently, the reliability of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that are benchmarked against it. Techniques such as Focused Ion Beam (FIB) lift-out and the direct growth of nanostructures via focused beam-induced deposition are critical for creating well-defined samples. This guide objectively compares the performance of established and emerging sample preparation methods, providing supporting experimental data to help researchers select the optimal technique for correlative TEM and MD studies.

Comparative Analysis of Sample Preparation Techniques

The following sections provide a detailed comparison of two primary sample preparation methodologies: the FIB lift-out technique for creating TEM lamellae and focused beam-induced deposition for crafting specialist geometries like nanowires and electrical contacts.

FIB Lift-Out for TEM Specimen Preparation

The FIB lift-out technique has revolutionized site-specific TEM sample preparation, enabling the extraction of thin foils from precise locations, such as across a grain boundary or from individual powder particles [24].

Experimental Protocol: In-Situ FIB-SEM Lift-Out The following workflow details the standard protocol for preparing a TEM specimen using a dual-beam FIB-SEM system [24].

- Site Selection and Protection: Identify the region of interest (e.g., a specific grain boundary or phase) using the SEM. Deposit a protective layer of platinum (Pt) via electron or ion beam-induced deposition to shield the top surface from ion beam damage during milling.

- Trench Milling: Use the FIB at a relatively high beam current (e.g., several nA) to mill trenches on both sides of the region of interest, isolating a thin wall of material (the "lamella").

- Undercutting and Lift-Out: Thin the lamella to electron transparency (typically <100 nm) using progressively lower ion beam currents to reduce damage. Use a micromanipulator needle, controlled in-situ within the FIB-SEM chamber, to weld onto the lamella, cut it free, and lift it out.

- Mounting: Transfer the lifted-out lamella to a TEM grid. Weld the lamella onto the grid using Pt deposition and then cut the connection to the micromanipulator.

- Final Cleaning and Polishing: Perform a final "polish" of the lamella using a low-energy ion beam (e.g., 2-5 kV) to minimize the amorphous damage layer and reduce ion implantation artifacts.

The technique's key advantage is its site-specificity and applicability to a vast range of materials, including hydrogen-sensitive metals like titanium alloys and fine powders, without the need for embedding media [24].

Figure 1: FIB-SEM Lift-Out Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps for preparing a site-specific TEM lamella.

Focused Beam-Induced Deposition for Specialist Geometries

For creating specialist geometries such as nanowires, electrical contacts, or three-dimensional nanostructures, Focused Electron/Ion Beam-Induced Deposition (FEBID/FIBID) are direct-write techniques. A significant advancement in this field is the development of cryogenic-assisted deposition (Cryo-FIBID/Cryo-FEBID), which offers a dramatic improvement in growth rate [25] [26].

Experimental Protocol: Cryo-FIBID for Metallic Nanowires The following methodology is used for the ultra-fast direct growth of metallic structures using Cryo-FIBID [25] [26].

- Substrate Cooling: Cool the substrate below the condensation temperature of the precursor material (e.g., -100°C for W(CO)₆).

- Precursor Condensation: Introduce the precursor gas via the Gas Injection System (GIS) to form a homogeneous condensed layer several nanometers thick on the cold substrate.

- Focused Ion Beam Irradiation: Irradiate the condensed layer with the focused ion beam (e.g., Ga⁺) according to the desired pattern. The required irradiation dose is drastically lower (~50 μC/cm²) than in conventional FIBID.

- Revelation by Heating: Heat the substrate to a temperature above the precursor's condensation point (e.g., 50°C). The unexposed condensed precursor layer becomes volatile and desorbs, leaving behind the deposit grown only in the irradiated areas.

This process benefits from the thick layer of precursor molecules available for dissociation, leading to a growth rate hundreds to thousands of times higher than conventional room-temperature FIBID [25].

Figure 2: Cryo-FIBID Process. This diagram illustrates the steps for ultra-fast deposition of metallic structures using a cryogenic precursor layer.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Deposition Techniques

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for room-temperature FIBID, cryogenic-FIBID (Cryo-FIBID), and cryogenic-FEBID (Cryo-FEBID), based on experimental data from the search results [25] [26].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Focused Beam-Induced Deposition Techniques

| Performance Metric | RT FIBID | Cryo-FIBID | Cryo-FEBID | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate (Volume per Dose) | ~0.1 μm³/nC [26] | ~60 μm³/nC [26] (600x faster than RT FIBID) | "Several hundred/thousand times higher than RT FEBID" [25] | Using W(CO)₆ precursor. |

| Typical Resistivity | 100–500 μΩ·cm [26] | Metallic, not far from RT deposits [25] | Information Not Specified | W-C based deposits. |

| Required Dose (for ~30 nm thick layer) | ~10⁴ – 10⁵ μC/cm² [26] | ~50 μC/cm² [26] | "Extremely low charge dose" [25] | Enables very fast processing. |

| Ga+ Concentration | ~10 at.% [26] | ≤0.2% [26] | Not Applicable | Reduced ion damage and implantation. |

| Lateral Resolution | ~20-30 nm | 38 nm demonstrated [26] | Information Not Specified | Enables nanoscale patterning. |

Application-Based Comparison of FIB Methodologies

The table below compares the core applications, advantages, and limitations of FIB lift-out and FIBID, helping to guide the choice of technique based on research goals.

Table 2: Comparison of FIB-Based Techniques for Different Research Applications

| Aspect | FIB Lift-Out | Conventional FIBID | Cryo-FIBID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Site-specific TEM lamella preparation [24]. | Direct growth of nanoscale structures & contacts [25]. | Ultra-fast growth of metallic structures & contacts [26]. |

| Key Advantage | Unmatched site-specificity; works on powders & sensitive materials [24]. | High metal content in deposits; single-step process [25]. | Extreme growth rate; very low ion damage & Ga+ implantation [25] [26]. |

| Main Limitation | Potential for ion beam damage (mitigated by low-kV polish) [24]. | Very slow growth rate; high ion dose causes substrate damage [25] [26]. | Requires cryogenic cooling stage; resolution may be slightly lower [25]. |

| Ideal for MD Benchmarking | Preparing lamellae from specific crystal orientations or phase boundaries for high-resolution structural validation [24]. | Creating connecting pads for electrical testing of devices; limited by substrate damage. | Rapid fabrication of nanowires and low-resistance contacts for electromechanical simulation models [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for FIB and Deposition Techniques

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Dual-Beam FIB-SEM | Combines a Focused Ion Beam for milling/deposition and a Scanning Electron Microscope for high-resolution imaging and navigation [24]. |

| Gas Injection System (GIS) | Delcribes precursor gases in a controlled manner to the substrate surface for electron or ion beam-induced deposition or etching [25]. |

| In-Situ Micromanipulator | A needle system used inside the FIB-SEM chamber to lift and transfer TEM lamellae onto a TEM grid [24]. |

| Pt Precursor (e.g., (CH₃)₃Pt(CpCH₃)) | Used for depositing conductive Pt-C protective layers and pads via FEBID or FIBID [25]. |

| W(CO)₆ Precursor | Tungsten hexacarbonyl precursor for depositing W-C based metallic nanowires and contacts via FIBID. Key for Cryo-FIBID [25] [26]. |

| Kleindiek Manipulator | A specific brand of high-precision micromanipulator commonly used for in-situ lift-out procedures [24]. |

| TEM Grid | A small, usually copper, mesh structure onto which the lifted-out lamella is mounted for TEM analysis [24]. |

The choice between FIB lift-out and focused beam-induced deposition techniques is dictated by the end goal of the research. FIB lift-out remains the indispensable method for preparing site-specific TEM samples from bulk materials or fragile powders, providing the structural data essential for validating MD simulations. For the direct fabrication of functional specialist geometries like nanowires and electrical contacts, cryogenic-assisted FIBID emerges as a superior alternative to conventional methods, offering unparalleled speed and minimized sample damage. Integrating these advanced preparation techniques ensures the acquisition of high-fidelity TEM data, creating a robust experimental foundation for the development and benchmarking of accurate molecular dynamics models.

In situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) has revolutionized materials science by enabling real-time observation of nanoscale dynamic processes as they occur under external stimuli. This capability provides direct experimental validation for computational models, particularly molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, creating a powerful feedback loop for predictive materials design. For researchers aiming to benchmark in situ TEM data against MD simulations, selecting the appropriate stimulus and holder technology is paramount, as it defines the fidelity and quantitative accuracy of the experimental data.

This guide provides a structured comparison of in situ TEM holders, focusing on their operational principles, performance metrics, and applications. It is designed to help researchers align their experimental setups with simulation frameworks, thereby bridging the gap between observed nanoscale phenomena and computational predictions.

Classifications and Comparisons of In Situ TEM Holders

In situ TEM methodologies are primarily classified by the type of external stimulus they apply. The choice of holder determines the environmental conditions and the nature of the data that can be collected, which in turn dictates how directly it can be compared with MD simulation outcomes [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary In Situ TEM Holder Types

| Holder Type | Key Stimuli | Typical Performance Range | Key Applications | Critical for MD Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heating Holder | Temperature | >1,100°C to -175°C [27] [28] | Phase transitions, nanoparticle sintering, grain growth [4] [28] | Provides temperature-dependent kinetic data for validating thermal activation models. |

| Biasing Holder | Electrical Field / Current | Not specified in results | Studying memristive materials, electronic properties, conduction mechanisms [27] | Directly correlates electric field with atomic-scale structural transformations. |

| Gas Cell Holder | Gas Environment + (Heating) | Up to 2 bar pressure, up to 1,000°C [27] | Catalyst structural changes under reactive environments, gas-solid interactions [4] [27] | Models catalytic reactions and surface dynamics in operando conditions. |

| Liquid Cell Holder | Liquid Environment | nm-scale resolution [27] | Nanoparticle nucleation & growth, electrochemical processes, biomolecular studies [4] [27] | Observes solution-phase growth mechanisms and interfacial phenomena. |

| Mechanical Holder | Strain / Deformation | Not specified in results | Fracture, dislocation dynamics, phase transformations under stress [29] | Provides stress-strain data at the atomic scale for validating mechanical property simulations. |

Advanced and Multi-Functional Holders

The frontier of in situ TEM lies in multi-modal experimentation, where multiple stimuli are applied simultaneously to mimic complex real-world conditions. For example, MEMS-based chips now enable concurrent heating and biasing experiments within the TEM [30]. Furthermore, advanced holders like the DENSsolutions Lightning Arctic can span a tremendous temperature range from cryogenic -175 °C to high temperatures while maintaining atomic resolution, allowing for the complete characterization of phase transitions in a single experiment [28]. This multi-stimuli capability is crucial for benchmarking MD simulations that also account for coupled physical fields.

Experimental Protocols for Key In Situ TEM Experiments

A rigorous experimental protocol is essential for generating reliable, quantitative data for MD benchmarking. The following sections detail methodologies for two common in situ TEM experiments.

Protocol for In Situ Heating Experiments

In situ heating is widely used to study thermal stability and phase transformations. The following protocol, based on a study of phase transitions in single-crystal BaTiO₃, outlines key steps [28]:

- Sample Preparation: Thin specimens are prepared using focused ion beam (FIB) milling and transferred to a MEMS-based heating chip. A carbon protection layer may be deposited to minimize beam damage.

- Holder Setup: A double-tilt MEMS heating holder (e.g., DENSsolutions Lightning) is used. The chip allows for active, four-point probe temperature measurement and control.

- Microscope Conditions: The TEM is operated at 300 kV. Imaging is performed in Bright-Field (BF) TEM or High-Angle Annular Dark-Field (HAADF) STEM mode. A constant, relatively low beam current (e.g., 3 nA for BF-TEM) is used to reduce electron-beam effects.

- Temperature Routine: The sample temperature is ramped from -175 °C to 200 °C at a controlled rate (e.g., 10 °C/min). The experiment includes pauses at specific temperatures to hold and observe phase stability.

- Data Acquisition: Images are acquired sequentially with a fast frame rate (e.g., 750 ms/frame). Simultaneous acquisition of analytical signals like EDS or EELS can be performed to monitor compositional or electronic structure changes.

Protocol for In Situ Liquid Cell Studies

Liquid cell TEM is used to investigate materials synthesis and electrochemical processes in liquid environments [4] [27].

- Cell Assembly: The liquid sample is sealed between two electron-transparent silicon nitride (SiN) windows in a microchip cell. This assembly isolates the liquid from the microscope's high vacuum.

- Holder Setup: A liquid-flow holder (e.g., Hummingbird liquid-flow holder) is used, allowing for control of the liquid chemistry and flow rate during the experiment.

- Microscope Conditions: The TEM is typically operated at lower accelerating voltages (e.g., 200 kV) to reduce beam damage to the liquid and specimens. Imaging resolution is typically limited to a few nanometers due to electron scattering in the liquid.

- Process Initiation: The reaction of interest (e.g., nanoparticle growth) is initiated, either by mixing reactants within the cell or by starting a flow of a new solution.

- Data Acquisition: Real-time imaging is performed to capture nucleation and growth events. Electron diffraction can be used concurrently to identify crystallographic phases of the forming nanostructures.

Integrating In Situ TEM and Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The integration of in situ TEM and MD simulations creates a "computational microscope" that provides a complete picture of material behavior, from atomic-scale mechanisms to observable dynamics. In situ TEM offers ground-truth experimental data on real-world processes, while MD simulations provide the atomic-level interpretation and predictive power that experiments alone cannot.

Recent advances in machine learning force fields (MLFFs), as demonstrated by systems like AI2BMD, are dramatically accelerating this synergy [31]. AI2BMD uses a protein fragmentation scheme and MLFF to achieve ab initio accuracy for energy and force calculations for proteins comprising over 10,000 atoms, reducing computational time by several orders of magnitude compared to density functional theory (DFT) [31]. This allows for hundreds of nanoseconds of dynamics simulations that can directly match the temporal and spatial scales probed by in situ TEM experiments.

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow for coupling in situ TEM experiments with MD simulations to accelerate materials discovery and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful in situ TEM experimentation relies on specialized components that enable the application of stimuli while maintaining imaging quality.

Table 2: Essential Materials for In Situ TEM Experiments

| Item | Function | Example & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS-based Chips | Microfabricated devices that hold the sample and integrate components for heating, biasing, or liquid/gas confinement. | Protochips Aduro (heating/biasing); DENSsolutions Climate (gas); DENSsolutions Lightning Arctic (heating/cryo) [30] [27] [28]. |

| Electron-Transparent Windows | Thin membranes that seal samples in liquid or gas environments while allowing the electron beam to pass through. | Silicon Nitride (SiN) windows, typically 10-50 nm thick, used in liquid and gas cell holders [27]. |

| Specialized TEM Holders | The hardware that inserts into the TEM, applies the stimulus, and connects to external control units. | Gatan, Protochips, and DENSsolutions holders for heating, cooling, biasing, liquid, and gas environments [27] [29]. |

| Fast, Sensitive Cameras | To capture dynamic processes at high temporal resolution with high signal-to-noise. | Gatan K3 IS camera, capable of recording at 5 fps on a 11520 x 8184 pixel array [29]. |

| Analytical Detectors | For simultaneous chemical and electronic structure analysis during in situ experiments. | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) and Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) systems, such as the Gatan GIF Continuum [4] [29]. |

The objective comparison of in situ TEM holders reveals a suite of highly specialized tools, each optimized for a specific set of stimuli and experimental conditions. For researchers benchmarking against MD simulations, the choice of holder dictates the quality and type of validation data. Heating and biasing holders provide direct input parameters for simulations, while environmental (gas and liquid) cells offer unparalleled insight into complex reaction dynamics.

The future of this field lies in the tighter integration of multi-modal in situ TEM data with increasingly accurate and scalable MD simulations, particularly those enhanced by machine learning. This powerful combination is transforming materials science from an observational discipline to a truly predictive one, enabling the rational design of next-generation materials for catalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine.

Within a research thesis focused on benchmarking in situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) data against molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the design of complementary MD models is paramount. In situ TEM experiments provide real-time, atomic-scale observations of material phenomena, such as defect dynamics during deformation [6] [32]. However, these observations alone often cannot reveal the underlying atomic-level mechanisms or the full three-dimensional stress state. MD simulations fill this gap by providing a dynamic, atomistic view of the processes imaged by TEM. The fidelity of this comparison hinges on two critical design choices: the selection of an appropriate interatomic potential and the implementation of physically meaningful boundary conditions. This guide objectively compares the available alternatives for these choices, providing the experimental data and protocols needed to inform robust simulation design.

A Comparative Analysis of Interatomic Potentials

The interatomic potential is the heart of an MD simulation, defining the energy and forces between atoms. Its choice dictates the reliability of the simulated material behavior.

Criteria for Potential Selection

A potential must be evaluated on its ability to reproduce key material properties relevant to the in situ experiment. For a study on mechanical deformation, these properties include:

- Elastic constants of the initial (e.g., austenite) and product (e.g., martensite) phases.

- Transformation stresses for phase transitions.

- Stress hysteresis during loading-unloading cycles.

- Recoverable strains and tension-compression asymmetry [33].

A common pitfall is validating a potential with only a single test case. A robust benchmarking process involves a high-throughput set of simulations across a wide range of conditions (different temperatures, orientations, and stress states) to thoroughly identify the limitations of each model [33].

Direct Comparison of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Potentials

A seminal study directly compared four interatomic potentials for NiTi (RS, ZGZ, KGN, TWL) under identical simulation conditions, providing a model for objective comparison [33]. The table below summarizes their performance against experimental data.

Table 1: Comparison of MD Interatomic Potentials for NiTi Superelasticity

| Potential (Type) | Transformation Stress | Stress Hysteresis | Elastic Moduli | Recoverable Strain | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS (Finnis-Sinclair) | Closer to exp. (300-600 MPa) | Closer to exp. (50-200 MPa) | Shows discrepancies | Varies with orientation | Stabilizes martensite phase |

| ZGZ (MEAM) | Over-predicts (>1 GPa) | Over-predicts (>1 GPa) | Shows discrepancies | Varies with orientation | High energy barrier |

| KGN (MEAM) | Over-predicts (>1 GPa) | Over-predicts (>1 GPa) | Shows discrepancies | Varies with orientation | High energy barrier |

| TWL (Deep Learning) | Over-predicts (>1 GPa) | Over-predicts (>1 GPa) | Shows discrepancies | Varies with orientation | High energy barrier |

Supporting Experimental Data: The study simulated uniaxial loading along the ({\langle 011\rangle }_{B2}) direction at room temperature. The RS potential predicted transformation stresses and hysteresis (300-600 MPa and 50-200 MPa, respectively) that fell within the experimental range. In contrast, the ZGZ, KGN, and TWL potentials consistently over-predicted these values, exceeding 1 GPa, which was attributed to an over-prediction of the energy barrier for phase transformation [33].

Potential Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for selecting and validating an interatomic potential, ensuring it is fit for purpose in benchmarking against in situ TEM data.

Implementing Physically Realistic Boundary Conditions

Boundary conditions (BCs) define the environment of the simulated system and are crucial for mimicking the experimental setup observed in in situ TEM.

Types of Boundary Conditions

- Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs): These are the standard choice for simulating bulk material behavior. PBCs approximate an infinite crystal by tiling the simulation box in all directions. As an atom exits one side of the box, it re-enters from the opposite side, and interactions are computed with the closest image of other atoms (the minimum-image convention) [34].

- Fixed (Dirichlet) Conditions: These specify the value of a variable, such as fixing the position of atoms in a boundary layer to simulate a rigid grip or surface [35].

- Free (Neumann-type) Conditions: These specify the derivative of a variable, such as applying a traction force to a surface [35].

PBCs for Bulk Behavior and Their Artifacts

PBCs are essential for studying bulk defect activity, such as the nucleation and glide of 〈c + a〉 dislocations in Mg, as they prevent free surfaces from acting as uncontrolled sinks for defects [6] [32]. However, they introduce specific artifacts that must be considered:

- Artificial Correlations: The periodicity does not respect the full translational invariance of a real system [34].

- Size Limitations: The simulation box must be large enough to prevent a defect from interacting with its own periodic image, which would produce unphysical dynamics. A common guideline is to have at least 1 nm of solvent (or material) around the molecule (or defect) of interest in every dimension [34].

- Wave Truncation: The wavelength of sound waves, shock waves, and phonons is limited by the box size [34].

- Charge Neutrality: For systems with ionic interactions, the net charge of the unit cell must be zero to avoid summing to an infinite charge under PBCs [34].

Table 2: Boundary Condition Types and Their Applications in MD

| Boundary Condition | Mathematical Definition | Primary Application in MD | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Periodic (PBC) | Value and derivatives match at opposite boundaries [34] | Simulating bulk material properties; defect dynamics [6] [33] | Box size must prevent self-interaction; can introduce correlational artifacts [34] |

| Dirichlet | Specifies the value of a variable (e.g., fixed displacement) [35] | Constraining surfaces or layers to mimic a rigid boundary | Can over-constrain the system and suppress natural relaxation |

| Neumann | Specifies the derivative of a variable (e.g., applied traction) [35] | Applying surface stresses or pressures | Less commonly used as a primary BC in atomic-scale deformation simulations |

Relating MD Boundary Conditions to In Situ TEM Experiments