Breaking the 100% Barrier: Innovative Methods to Increase Quantum Yield in Photocatalytic Reactions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest groundbreaking strategies for enhancing quantum yield in photocatalytic reactions, a critical efficiency parameter for researchers and drug development professionals.

Breaking the 100% Barrier: Innovative Methods to Increase Quantum Yield in Photocatalytic Reactions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest groundbreaking strategies for enhancing quantum yield in photocatalytic reactions, a critical efficiency parameter for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the fundamental principles of quantum yield and efficiency, detail advanced methodological breakthroughs including novel materials and reaction designs that enable quantum yields exceeding 100%, discuss troubleshooting and optimization techniques for experimental conditions, and present cutting-edge validation methods for performance comparison. The content synthesizes recent scientific advances that challenge traditional photochemical limits, offering practical insights for applications in pharmaceutical synthesis, energy conversion, and biomedical research.

Quantum Yield Fundamentals: Understanding the Photocatalytic Efficiency Landscape

Quantum Yield (QY) and Quantum Efficiency (QE) are fundamental parameters used to quantify the effectiveness of photocatalytic processes. While sometimes used interchangeably in casual conversation, they have distinct scientific definitions. Quantum Yield typically refers to the number of specific molecular events per absorbed photon, while Quantum Efficiency generally describes the ratio of output particles or energy to input photons in various optoelectronic systems. For researchers working to enhance photocatalytic performance, accurately understanding, measuring, and optimizing these parameters is crucial for evaluating catalyst materials and reaction systems, ultimately driving innovation in sustainable chemical synthesis and energy conversion technologies.

Fundamental Definitions and Distinctions

What is Quantum Yield (QY) in photochemical terms?

Quantum Yield (Φ) is defined as the number of times a specific defined event occurs per photon absorbed by the system [1]. For photochemical reactions, this is expressed as:

Φ = (Number of molecules reacting or formed) / (Number of photons absorbed) [2] [1]

This definition emphasizes that quantum yield is calculated based specifically on absorbed photons, not incident photons. The "defined event" can vary based on the system being studied—it could be the formation of a product molecule, decomposition of a pollutant, or generation of an electron-hole pair [2].

What is Quantum Efficiency (QE)?

Quantum Efficiency is a broader parameter that describes a system's ability to convert between "input" and "output" in various photonic and electronic processes [3]. Unlike quantum yield, which is predominantly used in photochemistry, quantum efficiency terminology appears across multiple disciplines including solar energy, light-emitting devices, and detection systems [3] [4].

What are the practical differences between QY and QE in photocatalytic research?

The terminology can vary significantly across different subfields, but these general distinctions apply:

Table: Key Differences Between Quantum Yield and Quantum Efficiency

| Parameter | Definition Focus | Primary Application Context | Photon Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Yield (QY) | Molecular events per photon | Photochemical reactions [2] [1] | Absorbed photons |

| Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) | Electrons transferred per photon | Photocatalysis screening [5] | Incident photons |

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Electron generation per photon | Solar cells, photodetectors [3] [6] | Incident photons |

| Internal Quantum Efficiency (IQE) | Electron generation per photon | Material characterization [6] | Absorbed photons |

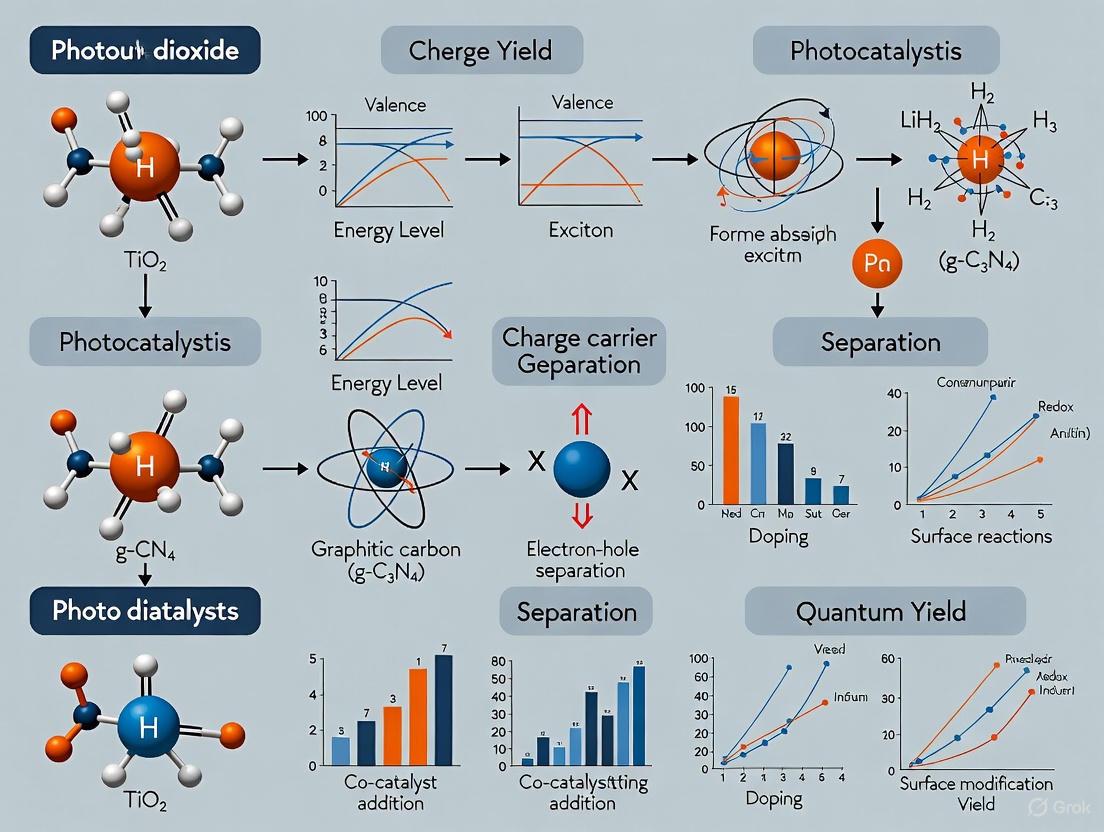

Diagram 1: Photon fate in photocatalytic processes shows multiple pathways that determine overall efficiency.

Critical Measurement Methodologies

How do I properly measure Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) for photocatalytic reactions?

AQY measurement requires monochromatic light and careful quantification of both reaction products and photon flux [5]:

AQY (%) = (Number of electrons transferred × 100) / (Number of incident photons) [5]

For hydrogen production reactions, the formula becomes: AQE (%) = 2 × (Number of H₂ molecules) / (Number of incident photons) × 100 [3]

The factor of 2 accounts for the two electrons needed to produce one H₂ molecule. Measurements should be performed under initial rate conditions to minimize secondary reactions and should specify the exact wavelength used [5].

What is the difference between absolute and relative quantum yield measurement methods?

Table: Comparison of Quantum Yield Measurement Methods

| Method | Principle | Requirements | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Method | Direct comparison of emitted to absorbed photons using integrating sphere [7] | Integrating sphere accessory | Solid samples, powders, scattering materials [7] | Requires specialized equipment |

| Relative Method | Comparison to reference standard with known quantum yield [1] [7] | Suitable reference compound with similar optical properties | Transparent liquid samples [7] | Limited by availability of appropriate standards |

What are the essential experimental protocols for accurate QY determination?

Use monochromatic light sources - LEDs or lasers with narrow bandwidth are preferred over broadband sources with filters [5]

Precisely measure photon flux - Use calibrated photodiodes or chemical actinometers to quantify the number of incident photons [2]

Control reaction conditions - Maintain constant temperature, stirring, and substrate concentrations during measurements [2]

Analyze products quantitatively - Employ appropriate analytical techniques (GC, HPLC, spectrophotometry) with calibration curves [5]

Perform initial rate measurements - Limit conversion to avoid secondary reactions and product inhibition effects [5]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Why is my measured quantum yield unexpectedly low?

Low quantum yields typically result from competitive processes that divert energy from the desired pathway:

- Charge carrier recombination - Electron-hole pairs recombine before participating in reactions [8]

- Insufficient active sites - The catalyst surface lacks appropriate coordination sites for the reaction [9]

- Mass transfer limitations - Reactants cannot reach active sites quickly enough [8]

- Competitive side reactions - Photogenerated species participate in unproductive pathways [9]

- Optical losses - Significant light scattering or reflection reduces effective absorption [2]

Why might my quantum yield measurements lack reproducibility?

Inconsistent QY measurements often stem from these common experimental variables:

- Light source instability - Fluctuations in intensity or spectral output [2]

- Inaccurate photon flux determination - Improper calibration of light measurement devices [5]

- Catalyst heterogeneity - Non-uniform composition or surface properties between batches [9]

- Oxygen contamination - Residual O₂ quenches excited states in many systems [9]

- Uncontrolled temperature effects - Local heating alters reaction kinetics [2]

How can I distinguish between catalyst-related and measurement-related issues?

Diagram 2: Systematic approach to diagnose low quantum yield results by categorizing potential failure points.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Can quantum yields exceed 100%, and what does this indicate?

Yes, quantum yields exceeding 100% are possible and indicate chain reactions where a single photon initiates multiple reaction events [10] [1]. Recent research has demonstrated quantum yields approaching or exceeding 100% in photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production systems [10]. These high values typically occur when:

- The reaction follows a radical chain mechanism [1]

- Multiple products form per photon through secondary reactions [10]

- Energy transfer cascades amplify the initial photonic input [9]

What strategies are emerging to increase quantum yields in photocatalysis?

Recent advances focus on both material design and reaction engineering:

- Dual cocatalyst systems - Separate reduction and oxidation sites to minimize recombination [8]

- Defect engineering - Create controlled vacancies or dopants to trap charge carriers [9]

- Z-scheme heterostructures - Mimic natural photosynthesis with two-photon systems [9]

- Plasmonic enhancement - Use metal nanoparticles to concentrate light energy [9]

- Molecular sensitization - Extend spectral response through dye molecules [9]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Quantum Yield Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations for QY Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic Light Source | Provides specific wavelength illumination for AQY [5] | Wavelength should match catalyst absorption peak; intensity must be measurable |

| Calibrated Reference Photodiode | Measures photon flux accurately [2] | Regular calibration essential; positioning critical for reproducible results |

| Chemical Actinometers | Provides alternative photon flux measurement [5] | Ferrioxalate is common; must match wavelength range |

| High-Purity Solvents | Reaction medium without quenchers | Remove dissolved oxygen; check for fluorescent impurities |

| Standard Reference Materials | Quantum yield benchmarks [1] [7] | Quinine sulfate, fluorescein for fluorescence; catalyst standards emerging |

| Integrating Sphere | Absolute quantum yield measurement [7] | Essential for powders, solids; captures all emitted/scattered light |

Accurately defining and measuring Quantum Yield and Quantum Efficiency is fundamental to advancing photocatalytic research. While QY focuses on molecular events per absorbed photon and finds primary application in photochemistry, QE encompasses broader conversion efficiencies across optoelectronic devices. As research progresses toward systems with quantum yields exceeding 100% through sophisticated chain reaction mechanisms [10], the precise understanding and application of these metrics becomes increasingly important. By implementing rigorous measurement protocols, systematically troubleshooting common issues, and leveraging emerging catalyst design strategies, researchers can continue to push the boundaries of photocatalytic efficiency for sustainable energy and chemical production.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental reasons why Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) was traditionally limited to below 100%? The AQY is the product of photon absorption efficiency, photon-electron conversion efficiency, and catalytic efficiency. Conventionally, a single absorbed photon can generate, at most, one electron-hole pair for subsequent catalytic reactions, provided the photon energy is greater than the material's bandgap. This fundamental principle placed a theoretical upper limit of 100% on the AQY, as achieving this would require near-perfect performance in all three efficiency categories simultaneously, a significant challenge for semiconductor materials [11].

FAQ 2: What is charge carrier recombination, and why is it a major bottleneck? Charge carrier recombination is the process by which photogenerated electrons and holes recombine before they can reach the catalyst surface to drive a chemical reaction. This process wastes the absorbed photon's energy, often releasing it as heat. In organic photocatalysts, this is a particularly severe limitation due to inherent properties like the formation of Frenkel excitons (bound electron-hole pairs), the presence of numerous energetic defects, and low charge separation efficiency [12]. Minimizing recombination is thus synonymous with maximizing device efficiency [13].

FAQ 3: Is it possible for the quantum yield to exceed 100%, and if so, how? Yes, recent research has demonstrated AQYs exceeding 100%. This phenomenon counters the traditional one-photon-to-one-electron paradigm. For instance, a process called photo-thermal synergistic impact ionization has been shown to achieve an AQY of up to 247.3%. In this mechanism, collisions of photoexcited electrons and thermal-activated electrons can produce more than one free electron per absorbed photon, breaking the traditional sub-100% barrier [11]. Other strategies involve designing reactions where both reduction and oxidation pathways produce the same valuable product, such as hydrogen peroxide, thereby potentially doubling the output per photon absorbed [10].

FAQ 4: How does the "cage escape" process influence quantum yield in photoredox reactions? Cage escape is a critical step in photoredox catalysis. After photoinduced electron transfer, the resulting radical pair (the reduced acceptor and the oxidized donor) is confined within a solvent cage. For a productive reaction to occur, these species must physically separate, or "escape," from this cage before they undergo a wasteful thermal reverse electron transfer. The quantum yield of this cage escape (ΦCE) directly governs the overall quantum yield of the photoredox reaction. Different photocatalysts can have inherently different ΦCE values, which explains why some catalysts are more efficient than others even with similar light absorption and electron transfer capabilities [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Charge Recombination

Problem: Low photocatalytic efficiency suspected to be caused by rapid charge recombination.

Symptoms:

- Low hydrogen evolution rate despite strong light absorption.

- Short carrier lifetime measurements (e.g., rapid voltage decay in photovoltage measurements) [13].

- Poor performance under low-light intensities, where recombination outcompetes extraction.

Solutions:

- Strategy A: Engineering Polymer Structure. For organic semiconductors, design the polymer backbone to enhance charge separation. Introducing a difluorothiophene (ThF) π-linker between acceptor-donor-acceptor (A-D-A) moieties can facilitate inter-unit charge transfer, leading to better charge separation and enabling activity under both visible and near-infrared light [15].

- Strategy B: Utilize Cocatalysts. Decorate the photocatalyst surface with dual or noble-metal-free cocatalysts. These act as efficient electron or hole sinks, extracting specific charge carriers and thereby suppressing recombination. This strategy has been used to achieve AQYs over 89% [11].

- Strategy C: Optimize Reaction Temperature. Increasing the reaction temperature can provide thermal energy that helps charge carriers overcome energy barriers for separation and migration. This photo-thermal synergy is a key factor in achieving ultra-high AQYs [11].

Guide 2: Achieving High Apparent Quantum Yield

Problem: Quantum yield is stuck at a plateau below desired levels.

Symptoms:

- Efficiency fails to improve even with reduced recombination.

- Performance drops significantly at longer wavelengths (lower photon energy).

Solutions:

- Strategy A: Leverage Impact Ionization. Select photocatalyst materials and conditions where a single high-energy photon can generate multiple charge carriers. This requires an incident photon energy greater than the bandgap but can be enhanced by synergistic thermal effects, as demonstrated with Cd0.5Zn0.5S at high temperatures [11].

- Strategy B: Optimize Photon Flux. Operate in the region of low light intensity. At high light intensities, high carrier densities can increase Auger recombination (a three-particle recombination process), which becomes a limiting factor and reduces the measured AQY [11] [13].

- Strategy C: Select a High-Cage-Escape Photocatalyst. For photoredox transformations, the choice of photocatalyst is critical. For example, [Ru(bpz)3]²⁺ has been shown to have consistently higher cage escape quantum yields than [Cr(dqp)2]³⁺ with various donors, directly leading to higher product formation rates and quantum yields [14].

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

| Photocatalyst System | Reaction | Highest Reported AQY | Key Innovation / Mechanism | Critical Experimental Conditions | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd0.5Zn0.5S | H2 Production | 247.3% | Photo-thermal synergistic impact ionization | High temperature; photon energy > bandgap but < 1.5x bandgap | [11] |

| PITIC-ThF Pdots | H2 Production | 4.76% @ 700 nm | A-D-A polymer with difluorothiophene π-linker for enhanced charge separation | Use of polymer nanoparticles (Pdots) for better dispersity | [15] |

| SrTiO3:Al with cocatalysts | H2 Production | ~100% @ 350 nm | Rh/Cr2O3 and CoOOH cocatalysts | UV light irradiation | [12] |

| [Ru(bpz)3]²⁺ with TAA-OMe | Photoredox Model | ΦCE = 58% | High cage escape quantum yield | Electron donor (TAA-OMe) in large excess | [14] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Photocatalysis | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Cd0.5Zn0.5S Solid Solution | Primary light absorber; platform for demonstrating impact ionization. | Synthesized via a precipitation-hydrothermal method for H2 production [11]. |

| ITIC/BTIC-based Polymers | Organic semiconductor with tunable bandgap for visible/NIR absorption. | Used as a single-component photocatalyst when formed into Pdots [15]. |

| Cocatalysts (e.g., Pt, CoOOH) | Facilitate charge transfer at the interface; reduce overpotential and suppress recombination. | Essential for achieving near-unity AQY on SrTiO3:Al [12] and high AQY on Cd0.5Zn0.5S [11]. |

| Sacrificial Donors (e.g., Na2S, Na2SO3, TAA) | Consume photogenerated holes, allowing the evaluation of proton reduction in half-reactions. | Used in H2 production experiments to enhance electron availability [11] [14]. |

| Polymer Nanoparticles (Pdots) | Enhance water dispersity, increase active surface area, and reduce charge diffusion length in organic photocatalysts. | Formed from ITIC-based polymers to improve photocatalytic performance [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating the Effect of Temperature and Wavelength on AQY

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to achieve AQY >100% [11].

Objective: To measure the AQY for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution under varying temperatures and incident light wavelengths.

Materials:

- Photocatalyst: Cd0.5Zn0.5S nanorods.

- Reactor: A gas-closed circulation system with a top-grade quartz window.

- Light Source: A 300 W Xe lamp with a tunable monochromator to select specific wavelengths.

- Gas Chromatograph (GC): Equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) to quantify evolved H2.

- Sacrificial Agent: Aqueous solution containing 0.35 M Na2S and 0.25 M Na2SO3.

- Temperature Control System: Thermostatic bath or heater to maintain reaction temperature (e.g., from 20°C to 70°C).

Procedure:

- Catalyst Dispersion: Disperse 10 mg of the Cd0.5Zn0.5S catalyst in 100 mL of the sacrificial agent aqueous solution.

- System Evacuation: Load the suspension into the reactor and evacuate the entire system to remove dissolved air.

- Temperature Equilibration: Set and maintain the reaction mixture at a desired temperature.

- Irradiation: Irradiate the suspension with monochromatic light of a specific wavelength (e.g., 420 nm). Precisely measure the light intensity (in mW cm⁻²) at the reactor window using a power meter.

- Gas Analysis: After a set irradiation time (e.g., 1 hour), analyze the gas in the system using the GC to determine the volume of produced H2.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 3-5 for different temperatures and wavelengths while keeping all other parameters constant.

- Calculation: Calculate the AQY using the formula:

- AQY (%) = [ (Number of reacted electrons) / (Number of incident photons) ] × 100

- Number of reacted electrons = [Moles of H₂ produced] × 2 (since 2 electrons are needed to produce one H₂ molecule) × Avogadro's number.

- Number of incident photons = [ (Light intensity × Area × Time) / (Photon energy at the given wavelength) ].

Mechanism and Workflow Visualizations

In semiconductor photocatalysis, Quantum Yield (QY) is a crucial metric that quantifies the efficiency of a photocatalytic process. It is defined as the number of defined events occurring per photon absorbed by the system [2]. For monochromatic radiation, it is calculated as the ratio of the number of molecules of a product formed to the number of photons absorbed [2]. A higher quantum yield indicates a more efficient photocatalyst, making it a key benchmark for comparing different materials and system configurations.

This technical guide synthesizes current research to provide a clear framework for measuring, troubleshooting, and improving quantum yields in your photocatalytic experiments, particularly for reactions like hydrogen evolution.

Benchmark Quantum Yields in Recent Literature

The following table summarizes benchmark quantum yields reported in recent, high-impact studies. These values represent the current state-of-the-art and provide targets for your own research.

| Photocatalytic System | Reaction | Reported Quantum Yield | Conditions & Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon nitride with radical trapping | H₂ Evolution | 132% (Apparent Quantum Yield) | Intermittent light at 360 nm; yield >100% due to current doubling effect [16]. | |

| K-PHI carbon nitride | H₂ Evolution | 68% (Apparent Quantum Yield) | Continuous 360 nm illumination [16]. | |

| H₂O₂ Production Systems | H₂O₂ Production | ~100% (External Quantum Yield) | Via Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR); multiple systems [17]. | |

| MoS₂ Monolayer | H₂ Evolution | Spatially Mapped (Internal Quantum Efficiency) | A-excitons outperform C-excitons; efficiency varies across flake [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Quantum Yield Measurement

Accurate measurement is foundational to reliable research. Below are detailed methodologies for determining quantum yield.

General Calculation Methodology

The fundamental equation for quantum yield (Φ) is [2]: Φ = (Number of molecules of product formed) / (Number of photons absorbed)

For a more practical, time-dependent calculation, the differential quantum yield is used [2]: Φ = (dx/dt) / n Where:

- dx/dt is the rate of change of the reactant or product concentration (in mol/s).

- n is the amount of photons (in Einstein/s) absorbed per unit time.

Protocol: Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) Measurement for H₂ Evolution

This is a common method for reactions like water splitting. AQY uses the number of incident photons, making it easier to measure than the absolute quantum yield which requires complex determination of absorbed photons [2].

- Principle: The rate of hydrogen production is measured under monochromatic light, and the AQY is calculated using the number of incident photons.

Key Equipment:

- Sealed photocatalytic reaction cell with a quartz window.

- Monochromatic light source (e.g., LED laser, band-pass filter with Xe lamp).

- Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for quantifying evolved H₂.

- Calibrated silicon photodiode or optical power meter for measuring incident light intensity (photons/cm²/s).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Setup: Disperse a precise mass of photocatalyst (e.g., 10 mg) in an aqueous solution containing a sacrificial electron donor (e.g., methanol, triethanolamine) in the reaction cell.

- Purge: Purge the system with an inert gas (e.g., Argon) for at least 30 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Seal: Seal the reaction cell and ensure it is airtight.

- Irradiate: Irradiate the suspension with monochromatic light of a known wavelength (λ).

- Measure Light Intensity: Use the calibrated photodiode at the same position as the reactor window to measure the incident light intensity (I₀ in W/m²). Convert this to the number of incident photons (n_incident):

n_incident = (I₀ * A * λ) / (h * c)Where A is the irradiation area, h is Planck's constant, and c is the speed of light. - Quantify Product: Use GC to sample the headspace gas at regular intervals to determine the rate of H₂ production (R in mol/s).

- Calculate AQY:

AQY (%) = [ (R * N_A) / n_incident ] * 100%Where N_A is Avogadro's number, and the factor of 2 accounts for the two electrons required to produce one H₂ molecule.

Advanced Measurement Techniques

- Electroanalytical Method (Cyclic Voltammetry): A recent preprint demonstrates using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to directly measure the quantum yield of molecular photocatalysts. The catalytic current is correlated with light intensity to derive the quantum yield, offering a rapid and simple alternative to traditional methods [19].

- Spatial Quantum Efficiency Mapping: For 2D materials like MoS₂, Scanning Photoelectrochemical Microscopy (SPECM) can spatially resolve the internal quantum efficiency. An ultramicroelectrode (UME) probe detects redox products generated at the semiconductor-liquid interface, mapping reactivity with high spatial resolution (~200 nm) [18].

Diagram 1: Workflow for measuring the Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) of hydrogen evolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and their functions as identified in current research for building high-efficiency photocatalytic systems.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Photocatalysis | Key Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cocatalysts (Earth-Abundant) | Enhances charge separation, provides active sites for H₂ evolution, reduces overpotential [20]. | Critical alternative to noble metals (Pt, Au); includes metal phosphides, carbides, transition metal dichalcogenides [20]. |

| Sacrificial Electron Donors | Scavenges photogenerated holes, prevents electron-hole recombination, thereby increasing electron availability for reduction [20]. | Methanol, triethanolamine, Na₂S/Na₂SO₃ are commonly used to study half-reactions [20]. |

| 2D Semiconductors (e.g., MoS₂) | Acts as a high-surface-area photocatalyst itself; its edges and defects are key active sites [18]. | SPECM studies show spatial variation in activity; excitonic nature (A-excitons) crucial for efficiency [18]. |

| Carbon Nitride Variants (e.g., K-PHI) | Polymer semiconductor with defect levels that can stabilize photogenerated charges and radicals for prolonged activity [16]. | Enables "dark photocatalysis" and radical trapping, leading to very high AQY [16]. |

| Radical Mediators (e.g., ·CH₂OH) | Photogenerated species that can be trapped at defect sites, donating additional electrons (current doubling effect) [16]. | Key to achieving quantum yields >100% in advanced systems [16]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Low Quantum Yield

Q1: My photocatalytic system shows a very low quantum yield. What is the most likely cause? The most common cause is the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs before they can reach the surface to participate in the reaction [20]. This can be due to bulk defects in the semiconductor or a lack of active sites to facilitate rapid charge transfer.

- Solution: Incorporate a cocatalyst (e.g., earth-abundant metal phosphides or carbides) onto your semiconductor. Cocatalysts act as electron sinks and provide active sites, synergistically enhancing charge separation and surface reaction kinetics [20].

Q2: How can I improve charge separation in my catalyst? Beyond adding cocatalysts, engineering your material to create an internal energy funnel can help.

- Solution: Design catalysts with defect levels that can trap charges. As demonstrated with K-PHI carbon nitride, trapping photogenerated radicals at defect levels can repopulate electrons post-illumination, maintaining catalytic activity and dramatically boosting quantum efficiency under intermittent light [16].

Q3: The active sites on my catalyst seem inefficient. How can I identify and optimize them? The location of photocatalytic active sites may not align with electrocatalytic intuition.

- Solution: Understand that photocatalytic sites differ from electrocatalytic ones. For 2D materials like MoS₂, while edges are key for electrocatalysis, the basal plane can be highly active for photoreduction due to exceptional electron mobility [18]. Use advanced characterization like SPECM to spatially map your catalyst's true photocatalytic activity and guide rational design [18].

Q4: Is it possible to achieve a quantum yield over 100%? What does this imply? Yes, recent research has demonstrated quantum yields exceeding 100%. This does not violate energy conservation but indicates a chain reaction mechanism or current doubling effect.

- Solution: Design systems that leverage secondary reactions. For example, in H₂O₂ production, systems can be designed where both reduction and oxidation pathways produce H₂O₂, potentially leading to quantum yields >100% [17]. In H₂ evolution, the trapping of photogenerated radicals (e.g., ·CH₂OH from methanol) can inject a second electron into the catalyst, allowing a single photon to ultimately generate two electrons for hydrogen evolution [16].

Diagram 2: A logical troubleshooting flowchart for diagnosing and addressing low quantum yield in photocatalytic experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is quantum yield and why is it a critical metric in photocatalysis? Quantum Yield (QY) is a fundamental figure of merit that quantifies the efficiency of a photocatalytic process. It is defined as the ratio of the number of product molecules formed to the number of photons absorbed by the photocatalyst [21]. A high QY indicates efficient utilization of light energy for the desired chemical transformation, which is paramount for developing industrially viable and sustainable photocatalytic applications, from hydrogen production to wastewater treatment [10] [22] [23].

2. Within the theoretical framework, what are the primary pathways to increase quantum yield? Increasing QY hinges on optimizing the three core stages of the photocatalytic process, as defined by the theoretical framework:

- Enhancing Photon Absorption: Strategies include developing narrow-bandgap semiconductors to harness more visible light [22] [23] and engineering materials to leverage specific excitonic transitions (e.g., A-excitons in MoS2 monolayers have been shown to have higher internal quantum efficiency than C-excitons) [18].

- Promoting Charge Separation: This is the most critical area for improvement. Key methods involve creating a built-in electric field (BIEF) through heterojunctions [22], deliberate defect engineering to trap one type of charge carrier [22] [23], and using cocatalysts to act as electron or hole sinks [22].

- Facilitating Catalytic Conversion: This involves maximizing the surface reactive sites and ensuring efficient charge transfer to adsorbed reactants. Spatial studies reveal that oxidation and reduction sites can be distinct, and identifying these active sites is crucial for rational catalyst design [18].

3. What advanced techniques can spatially resolve photocatalytic activity and quantum efficiency? Scanning Photoelectrochemical Microscopy (SPECM) is a powerful operando technique that can map photocatalytic active sites and local quantum efficiency with high spatial resolution (~200 nm). It directly detects redox products (e.g., H₂ from water reduction) generated at the catalyst-liquid interface under illumination, providing a quantitative and chemically-specific assessment of performance [18].

4. Can the quantum yield theoretically exceed 100%? Yes, in specific photocatalytic systems. For reactions like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) production, it is possible to design a simultaneous reduction and oxidation process (H₂O₂/H₂O₂-PCP) where both the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and water oxidation reaction (WOR) pathways contribute to the same product. This dual-channel production can lead to quantum yields exceeding 100% [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Product Yield Despite High Light Absorption

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Rapid Electron-Hole Recombination

- Solution A: Construct a Heterojunction. Couple your semiconductor with another material with matching band structures to create a built-in electric field that drives charge separation. For example, S-scheme heterojunctions are particularly effective [22].

- Solution B: Employ Defect Engineering. Introduce specific anionic vacancies (e.g., C, N, O, S vacancies) to create unsaturated sites that can trap charge carriers, thereby inhibiting recombination [22] [23].

Cause: Inefficient Charge Transfer to Surface Reaction Sites

- Solution: Decorate with Cocatalysts. Load noble metal (e.g., Pt) or non-noble metal-based nanoparticles to act as electron sinks, thereby lowering the activation energy for surface reactions like hydrogen evolution [22].

Problem 2: Poor Stability and Photocorrosion of Catalyst

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Oxidation of the Catalyst by Photogenerated Holes

- Solution: Use Hole Scavengers. Add sacrificial reagents (e.g., methanol, triethanolamine) to the reaction mixture. These reagents preferentially react with and consume holes, protecting the catalyst from oxidation. This is a common strategy to probe the intrinsic reduction activity of a material [23].

- Solution: Develop Core-Shell Structures. Synthesize catalysts with protective shells (e.g., CdSe/ZnS core-shell nanocrystals) to physically isolate the photoactive core from the corrosive environment [21].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Quantum Yield Measurements

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect Accounting for Emitted or Transmitted Light

- Solution: Use an Integrated Setup. Implement a method where the transmission of the excitation light and the fluorescence of the solution are measured in a single spectrum. This minimizes errors related to detector positioning and cuvette reproducibility [21].

- Solution: Apply Refractive Index Corrections. When comparing a sample to a reference standard dissolved in different solvents, correct for the difference in refractive index using the formula:

Y_x = (IF_x / IF_s) * ( (I0_s - IT_s) / (I0_x - IT_x) ) * (n_x² / n_s²) * Y_s[21].

Quantitative Data for Photocatalytic Reactions

The following table summarizes key operational parameters and their impact on quantum yield and efficiency, based on recent research.

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing Photocatalytic Efficiency and Quantum Yield

| Parameter | Impact on Quantum Yield & Efficiency | Optimal Range / Example | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Wavelength | Determines which electronic transitions (excitons) are activated. A-excitons in MoS₂ show higher internal quantum efficiency than C-excitons [18]. | Match to catalyst's absorption profile (e.g., A-transition ~670 nm for MoS₂) [18]. | Using only UV light (e.g., for TiO₂) limits solar efficiency; visible-light-active catalysts are preferred [23]. |

| Charge Separation Strategy | Directly controls the fraction of photogenerated charges that reach the surface. A built-in electric field is highly effective [22]. | Heterojunctions (e.g., S-scheme), defect engineering, and BIEF design [22]. | Poor separation is a primary cause of low QY. Spatial mapping (SPECM) can identify separation efficiency [18]. |

| Catalyst Loading | Excessive loading causes light scattering and shielding, reducing photon penetration and overall efficiency [23]. | System-dependent; requires empirical optimization for each reactor setup. | There is a saturation point beyond which adding more catalyst decreases the reaction rate. |

| pH of Solution | Affects catalyst surface charge, pollutant adsorption, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation pathways [23]. | Varies by catalyst (e.g., related to the Point of Zero Charge - PZC). | Lower pH often favors •OH production. Extreme pH can degrade the catalyst structure [23]. |

| Use of Sacrificial Reagents | Can dramatically increase apparent QY by consuming one type of charge carrier (e.g., holes), allowing the other to drive the desired reaction [23]. | Common reagents: Methanol, triethanolamine (hole scavengers); Na₂S/Na₂SO₃ (electron scavengers). | This is a useful diagnostic tool but is not sustainable for large-scale application. |

Experimental Protocols

Principle: The unknown quantum yield (Yx) of a sample is determined by comparing its absorption and emission to a reference dye with a known quantum yield (Ys).

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a fluorometer with a Xenon lamp and monochromator to select the excitation wavelength (e.g., 440 nm). A high-pass filter (e.g., KV520) is placed before the detector to attenuate the intense transmitted beam while passing the full emission spectrum.

- Measurement:

- For both the reference (e.g., Rhodamine 101 in ethanol, Y_s = 0.96) and the sample, record a single spectrum that includes both the transmitted excitation peak and the full emission band.

- Measure the pure solvent separately to obtain the baseline transmission intensity (I₀).

- Data Analysis:

- Transmission Intensity (IT): Integral of the spectrum over the excitation wavelength interval.

- Fluorescence Intensity (IF): Integral of the corrected emission spectrum over the emission wavelength interval.

- Calculate the unknown quantum yield using the formula:

Y_x = (IF_x / IF_s) * ( (I0_s - IT_s) / (I0_x - IT_x) ) * (n_x² / n_s²) * Y_swherenis the refractive index of the solvent.

Principle: Scanning Photoelectrochemical Microscopy (SPECM) spatially resolves photocatalytic activity by detecting electroactive products generated at the catalyst-liquid interface.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: A catalyst of interest (e.g., a monolayer MoS₂ flake) is immobilized on a substrate.

- Setup (Substrate Generation-Tip Collection Mode):

- The catalyst substrate is immersed in an electrolyte solution containing a redox mediator.

- An ultramicroelectrode (UME) tip is positioned close to the catalyst surface.

- A focused light source excites a localized spot on the catalyst.

- Measurement:

- The UME is biased at a potential selective for the product of interest (e.g., H₂ for reduction, oxidized mediator for oxidation).

- The tip is raster-scanned across the surface while the photoactivity (ΔI = IT,Light - IT,Dark) is recorded.

- A positive ΔI indicates local reduction product generation; a negative ΔI indicates oxidation.

- Data Analysis: The ΔI map directly visualizes the spatial distribution of reactive sites. The magnitude of ΔI is proportional to the local quantum efficiency for the specific redox reaction being probed.

Core Mechanism and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Photocatalytic process with key steps and loss pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Photocatalytic Research

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Catalysts | Light-absorbing materials that generate electron-hole pairs. The core of the photocatalytic system. | TiO₂ (UV-active), g-C₃N₄ (visible-light-active), MoS₂ (2D TMD) [22] [18] [23]. |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Electron or hole scavengers that consume one charge carrier to study the reaction driven by the other, or to protect the catalyst. | Methanol, Triethanolamine (hole scavengers); Na₂S/Na₂SO₃ (electron scavengers) [23]. |

| Reference Dyes (for QY) | Standards with known quantum yield for accurate relative measurement of unknown samples. | Rhodamine 101 (QY=0.96 in ethanol) for fluorescence QY determination [21]. |

| Redox Mediators (for SPECM) | Molecules that undergo reversible redox reactions to probe oxidative or reductive activity in spatial mapping. | Ferrocenedimethanol (FcDM) for mapping oxidation sites [18]. |

| Cocatalysts | Nanoparticles deposited on the semiconductor surface to enhance charge separation and provide active sites for specific reactions. | Pt nanoparticles for H₂ evolution reaction [22]. |

Breakthrough Strategies and Material Designs for Superior Quantum Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our Sb-doped SnO2 material shows inconsistent electrical conductivity and photocatalytic performance. What could be the cause? Inconsistent conductivity and performance often stem from poor control over the antimony (Sb) doping process. The oxidation state of Sb ions incorporated into the SnO2 crystal lattice critically determines the material's electronic properties.

- Primary Cause: Uncontrolled ratio of Sb³⁺ to Sb⁵⁺ oxidation states. The substitution of Sn⁴⁺ with Sb³⁺ creates an acceptor level, while Sb⁵⁺ creates a donor level; the ratio of these states directly regulates the free charge carrier concentration and the material's overall conductivity type and magnitude [24].

- Solution: Precisely control the synthesis temperature and calcination conditions, as these parameters significantly influence the final Sb oxidation state ratio [24]. Use characterization techniques like XPS to confirm the surface Sb oxidation states.

Q2: How can I enhance the selectivity of the nanohybrid material for H₂O₂ production over other reactive oxygen species? Achieving high selectivity for H₂O₂ requires precise tuning of the electronic structure to favor the two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (ORR).

- Primary Cause: A conduction band position and electronic density that favors the four-electron ORR pathway, leading to water instead of H₂O₂.

- Solution: Utilize the band-gap engineering capabilities of Sb-doped SnO2. Doping with Sb can create a shallow donor level near the conduction band and generate oxygen vacancies [24]. Coupling this optimized Sb-SnO2 with ZnO can create a heterojunction with a tailored electronic structure that selectively promotes the two-electron pathway for H₂O₂ production. The enhanced catalytic activity from doping, as seen in other oxidative reactions, supports this strategy [25].

Q3: What is the impact of high relative humidity on the stability and performance of our sensor? While this FAQ context focuses on H₂O₂ production, insights from gas sensing research are directly relevant, as water vapor can compete for active sites.

- Primary Cause: Water molecules adsorbing onto active sites, blocking the target reaction (oxygen reduction to H₂O₂).

- Solution: Research on highly Sb-doped SnO2 for gas sensing has shown that the material can exhibit a limited influence of humidity on its performance [24]. This suggests that incorporating Sb into your SnO2/ZnO nanohybrid could improve its resilience and consistent performance in humid environments.

Q4: Our synthesized nanoparticles are aggregating, leading to a reduction in surface area and performance. How can this be mitigated? Aggregation reduces the active surface area available for catalysis.

- Primary Cause: Standard synthesis methods often involve high-temperature annealing and organic surfactants that can be difficult to remove completely, leading to sintering and aggregation [26].

- Solution: Employ advanced synthesis methods like the ozone-assisted hydrothermal synthesis [26]. This surfactant-free method produces well-crystallized, non-aggregated Sb-doped SnO2 nanoparticles smaller than 7 nm, providing a high surface area ideal for catalytic applications.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Function: This protocol provides a foundational method for creating the Sb-doped SnO2 component of the nanohybrid.

Materials:

- Precursors: Stannous chloride (SnCl₂·H₂O) and Antimony trichloride (SbCl₃).

- Solvents & Reagents: Ethanol, De-ionized water, Ammonia, Citric acid, Hydrochloric acid.

- Equipment: Magnetic stirrer with heating, beakers, filtration setup, and Muffle Furnace.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dissolve Stannous Chloride in de-ionized water and ethanol. Add Citric Acid as a fuel agent to the solution.

- Doping: Introduce Antimony Trichloride to the solution at varying molar concentrations (e.g., 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%) to create different doping levels.

- Gelation: Stir the mixture vigorously and adjust the pH to ~8 using ammonia solution, leading to the formation of a gel.

- Aging & Drying: Age the gel for 24 hours, then dry it in an oven at 120°C for 4 hours.

- Calcination: Transfer the dried powder to a Muffle Furnace and calcine at 700°C for 3 hours to obtain the final crystalline ATO nanoparticles.

Function: This advanced protocol produces highly crystalline, non-aggregated Sb-doped SnO2 nanoparticles, ideal for high-performance applications.

Materials: Tin(II) fluoride (SnF₂), Antimony trichloride (SbCl₃), Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) solution, Ozone generator, Autoclave with Teflon liner.

Procedure:

- Mixing: Dissolve SnF₂ and SbCl₃ (e.g., for 5 at.% or 10 at.% Sb) separately in de-ionized water, then mix them together.

- Precipitation: Add TMAH solution to the mixed metal solution under sonication until it becomes milky white.

- Oxidation: Perform ozone bubbling (e.g., 3 L/min, 70°C) into the solution for 1 hour with stirring. The solution will turn yellow and transparent.

- Concentration: Use a rotary evaporator to reduce the volume of the reacted solution.

- Crystallization: Transfer the concentrated solution to an autoclave and heat at 240°C for 12 hours.

- Washing & Dispersion: Centrifuge the resulting dark blue precipitate. Wash the precipitate with water and disperse the final product in methanol using an ultrasonic homogenizer.

Key Material Characterization Data

Table 1: Characterization of Synthesized Sb-doped SnO2 (ATO) Nanoparticles

| Dopant Concentration (Sb) | Crystallite Size (nm) | Band Gap (E𝑔) | Primary Morphology | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-8 at.% (Sol-Gel) [27] | 9 - 26 | 3.65 - 3.85 eV | Polyhedral | Crystallite size decreases with increasing Sb doping [27]. |

| 5 at.% & 10 at.% (Ozone-Hydrothermal) [26] | < 7 | N/R | Highly Crystallized Nanoparticles | High conductivity; ideal for catalyst supports [26]. |

| 10 & 15 wt.% (Commercial) [24] | N/R | N/R | Nanoparticles | Doping hinders SnO₂ grain growth and expands lattice parameters [24]. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Doped SnO₂ Materials in Various Applications

| Material | Application | Key Performance Indicator | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt/Sb-SnO₂ | Fuel Cell ORR Catalyst | Mass Activity @0.9V | 178.3 A g-Pt⁻¹ | [26] |

| Pt/Sb-SnO₂ | Fuel Cell ORR Catalyst | ECSA Retention (100k cycles) | 80% (vs. 47% for Pt/C) | [26] |

| Sb-doped SnO₂ | Formaldehyde Gas Sensing | Sensitivity & Selectivity | High | [27] |

| Highly Sb-doped SnO₂ | NO₂ Gas Sensing | Sensitivity & Humidity Influence | Good sensitivity, limited humidity impact | [24] |

| Cr-Sb@SnO₂ | Electrooxidation of Cysteine | Oxidation Current (vs. bare electrode) | Significantly greater (14.2 μA) | [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Sb-SnO2/ZnO Nanohybrid Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Stannous Chloride (SnCl₂) | Primary precursor for the SnO₂ matrix. | Provides the tin source for forming the foundational metal oxide lattice [27]. |

| Antimony Trichloride (SbCl₃) | Dopant precursor to modify SnO₂'s electronic properties. | Introduces Sb ions, creating donor levels and oxygen vacancies that enhance electrical conductivity and tailor the band structure [27] [24]. |

| Zinc Precursor (e.g., Zn(NO₃)₂) | Source for the ZnO component in the nanohybrid. | Forms the second semiconductor to create a heterojunction, facilitating efficient charge separation for photocatalysis. |

| Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide (TMAH) | Precipitating agent in hydrothermal synthesis. | Facilitates the co-precipitation of metal hydroxides from precursor solutions in a controlled manner [26]. |

| Ozone Generator | Critical tool for advanced oxidative synthesis. | Provides a strong, surfactant-free oxidizing environment to form well-crystallized, pure SnO₂ nanoparticles, preventing aggregation [26]. |

| Ethylene Glycol | Solvent and reducing agent in polyol synthesis methods. | Often used for loading Pt nanoparticles onto support materials like Sb-SnO₂ for electrocatalytic testing [26]. |

Experimental Workflow & Material Optimization Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and optimizing the Sb-doped SnO2/ZnO nanohybrid material, from synthesis to performance validation.

Diagram 1: Material Development and Optimization Workflow.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is a dual-pathway reaction for H₂O₂ production, and why is it beneficial? A dual-pathway reaction for hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) production simultaneously utilizes the two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (2e⁻ ORR) and the two-electron water oxidation reaction (2e⁻ WOR) in a single system [28] [29]. This approach is beneficial because it theoretically allows for 100% atom utilization efficiency. The H⁺ protons generated from the WOR participate in the ORR, while the ORR provides holes (h⁺) for the WOR, creating a synergistic cycle that avoids the need for sacrificial agents and can lead to a significant enhancement in the overall H₂O₂ production rate and efficiency [29].

Q2: My photocatalytic H₂O₂ production system has a low apparent quantum yield (AQY). What could be the issue? Low AQY is often traced to two main issues:

- Poor Charge Separation: If photogenerated electrons and holes recombine before they can reach the reaction sites, the quantum yield will be low [29]. Consider designing catalysts with integrated dual active sites, such as single atoms for electron capture and specific functional groups (like pyridine N) as hole acceptors, to direct charge flow and suppress recombination [29].

- Unselective Reaction Pathways: The oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) can proceed via a one-step 2e⁻ pathway (direct) or a two-step 2e⁻ pathway (indirect) that generates superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻). These radicals can compete for electrons, damage the photocatalyst, and lower the selectivity for H₂O₂ production [29]. Enhancing the selectivity towards the direct 2e⁻-ORR is crucial for high efficiency.

Q3: I am observing catalyst degradation in my system. How can I improve its stability? Catalyst degradation can be caused by reactive oxygen species like ·O₂⁻ generated from unselective pathways [29]. To improve stability:

- Design for Selectivity: Engineer catalyst active sites that favor the direct 2e⁻ ORR pathway to minimize the formation of destructive radicals [29].

- Use Robust Frameworks: Consider using stable covalent triazine frameworks (CTFs) or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as catalyst platforms, which can offer high resistance to H₂O₂ poisoning and maintain structural integrity [29].

Q4: How can I accurately measure the quantum yield of my photocatalytic system?

Accurate quantum yield measurement is critical. The general formula for the photochemical loss rate constant is:

j = ∫Φ_loss(λ) · I₀(λ) · ε(λ) dλ

where Φ_loss is the quantum yield for loss, I₀ is the incident photon flux, and ε is the molar absorptivity [30]. Using narrow-band UV-LEDs as light sources allows for calculating wavelength-dependent quantum yields, which is more precise than using broadband illumination [30]. A novel electroanalytical method using cyclic voltammetry (CV) has also been demonstrated to directly measure the molecular quantum yield of photocatalysts by correlating light intensity with catalytic current, providing a rapid and orthogonal measurement approach [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low H₂O₂ Production Rate | 1. Rapid charge recombination.2. Unselective reaction pathway (indirect 2e⁻ ORR).3. Insufficient active sites. | 1. Perform photoluminescence spectroscopy to check recombination.2. Use scavenger tests or ESR to detect ·O₂⁻ radicals.3. Measure BET surface area. | 1. Engineer catalysts with spatially separated dual active sites (e.g., d-CTF-Ni) [29].2. Modify electronic structure (e.g., introduce π-deficient units) to favor direct 2e⁻ ORR [29]. |

| Poor Quantum Yield (AQY) | 1. Inefficient light absorption.2. Wavelength-dependent quantum yield effects.3. Back reactions consuming H₂O₂. | 1. Record UV-Vis absorption spectrum.2. Measure AQY at different wavelengths [30].3. Monitor H₂O₂ concentration over time. | 1. Use sensitizers or narrow-bandgap semiconductors.2. Optimize light source to match catalyst's peak quantum yield wavelength [30].3. Add stabilizers or operate at lower conversions. |

| Catalyst Deactivation | 1. Oxidation by reactive species (·O₂⁻).2. Photocorrosion.3. Poisoning by products or impurities. | 1. Conduct XPS to check for surface oxidation.2. Analyze spent catalyst via TEM and XRD.3. Test with purified reagents. | 1. Design catalysts that suppress ·O₂⁻ formation [29].2. Use more stable covalent frameworks (e.g., CTFs, MOFs).3. Implement a catalyst regeneration protocol. |

| Irreproducible Results | 1. Fluctuations in light source intensity.2. Inconsistent oxygen purging.3. Variations in solution pH. | 1. Calibrate light source regularly with an actinometer (e.g., 2-nitrobenzaldehyde) [30].2. Monitor dissolved O₂ concentration.3. Use a pH-stat. | 1. Standardize actinometry procedures before each experiment [30].2. Standardize purging time and gas flow rate.3. Use strong buffer solutions. |

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Dual-Active Site Catalyst (d-CTF-Ni)

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a covalent triazine framework (CTF) modified with nickel single atoms and pyridine nitrogen defects, designed for dual-pathway H₂O₂ production [29].

- Objective: To create a catalyst with spatially isolated active sites where Ni single atoms serve as electron-capture centers for the 2e⁻ ORR and pyridine N sites serve as hole acceptors for the 2e⁻ WOR [29].

- Materials:

- 1,4-dicyanobenzene

- 2,6-Dicyanopyridine

- Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (CF₃SO₃H)

- Nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate (Ni(OAc)₂·4H₂O)

- Ethanol and deionized water

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of Defect-rich CTF (d-CTF): Dissolve a mixture of 1,4-dicyanobenzene and 2,6-dicyanopyridine (molar ratio 1:1) in 3 mL of CF₃SO₃H at 0°C. Stir the mixture for 1.5 hours and then heat at 100°C for 20 minutes until yellow crystals form.

- Washing: Wash the resulting solid extensively with distilled water and ethanol via alternating centrifugation cycles (10,000 rpm for 5 min) to remove all residual monomers and acid. Dry the final product to obtain d-CTF.

- Anchoring Ni Single Atoms: Impregnate the d-CTF powder with an aqueous solution of Ni(OAc)₂·4H₂O. Dry the mixture and then anneal it at 400°C for 2 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere to form the final d-CTF-Ni catalyst [29].

- Characterization: Confirm the structure and properties using Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM), High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and BET surface area analysis [29].

Protocol 2: Measuring Wavelength-Resolved Quantum Yields

Accurate quantum yield measurement is essential for evaluating and comparing photocatalysts.

- Objective: To determine the wavelength-dependent quantum yield for photocatalytic loss of a reactant [30].

- Materials:

- Photocatalyst solution/suspension

- Narrow-band UV-LEDs (e.g., 300, 318, 325, 340, 375, 385 nm)

- HPLC system with UV-Vis detector

- Chemical actinometer (e.g., 2-nitrobenzaldehyde, NBA)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Procedure:

- Light Source Calibration: Determine the photon flux of each LED using 2-nitrobenzaldehyde actinometry. Prepare an NBA solution and illuminate it for set time intervals. Monitor the conversion of NBA to 2-nitrosobenzoic acid using HPLC. The known quantum yield of NBA (Φ=0.43 between 300-400 nm) allows for the calculation of photon flux [30].

- Photocatalysis Experiment: Illuminate your photocatalytic reaction solution with the calibrated LEDs. Take samples at regular time intervals.

- Analysis: Quantify the concentration of the reactant or product over time using HPLC or UV-Vis.

- Calculation: Calculate the wavelength-specific quantum yield (Φ(λ)) using the initial rate of reaction and the calibrated photon flux [30].

Quantitative Performance Data of Photocatalysts

The following table summarizes the H₂O₂ production performance of various advanced catalysts, providing a benchmark for researchers.

| Photocatalyst | Reaction Pathway | Production Rate (μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹) | Light Conditions | Key Feature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-CTF-Ni | Dual (ORR & WOR) | 869.1 | Visible light | Ni single atoms & pyridine N defects | [29] |

| ZIF-8/g-C₃N₄ | Dual (ORR & WOR) | 2,641 | Not specified | Metal-organic framework/composite | [29] |

| HTMT-CD | Dual (ORR & WOR) | 4,240 | Not specified | Carbon dots as WOR site | [29] |

| CPN | Dual (ORR & WOR) | 1,968 | Not specified | Organic polymer | [29] |

| CN-CRCDs | Dual (ORR & WOR) | Significant enhancement reported | Not specified | Heterojunction for charge separation | [29] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Dual-Pathway H2O2 Production Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for Catalyst Testing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Dual-Pathway Reactions | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Triazine Frameworks (CTFs) | Catalyst platform with tunable electronic structure; triazine units create π-deficient structures for enhanced charge separation [29]. | Precursor selection (e.g., dicyanopyridine) introduces pyridine N defects for hole acceptance [29]. |

| Single-Atom Metals (e.g., Ni) | Serves as an electron-capture center to direct electrons for the 2e⁻ Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) [29]. | The coordination environment (e.g., Ni-Nₓ) is critical for stability and activity. |

| 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde (2-NBA) | Chemical actinometer for precise calibration of photon flux from light sources, enabling accurate quantum yield calculation [30]. | Essential for standardizing experiments; requires HPLC for monitoring its degradation [30]. |

| Narrow-band UV-LEDs | Provides monochromatic light to measure wavelength-resolved quantum yields, allowing for direct comparison under different solar conditions [30]. | Preferable to broadband sources for mechanistic studies and precise efficiency evaluations [30]. |

| Bipyridinium Compounds (e.g., Methyl Viologen) | Used as redox mediators in model systems to study electron transfer efficiency in "uphill" photocatalytic reactions [31]. | Useful for probing charge separation efficiency independent of complex product formation kinetics [31]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: What are the most effective strategies to boost the quantum yield of my Cd({0.5})Zn({0.5})S (CZS) photocatalyst?

A: Research indicates several high-efficacy strategies, primarily involving the integration of cocatalysts and surface engineering. Key approaches include:

- Loading Amorphous Cocatalysts: Anchoring amorphous cobalt sulfide (CoS) as a cocatalyst via an in-situ precipitate transformation method can significantly enhance H(_2) evolution. The CoS acts as an effective reduction cocatalyst, while simultaneously adsorbed S(^{2-}) ions serve as hole traps, creating a synergistic effect that improves charge separation [32].

- Ni(II)-based Cocatalysts: Surface modification of CZS with Ni(OH)(2) via a simple impregnation method has proven highly effective. The Ni(OH)(2) plays a critical hole-trapping role, which inhibits charge carrier recombination. This method has achieved a quantum efficiency of 15.8% at 415 nm [33].

- Constructing Heterojunctions: Building an S-scheme heterojunction, for instance by combining CZS with Bi(2)WO(6), can substantially improve photo-carrier separation and preserve strong redox ability. This architecture also helps suppress the photo-corrosion of CZS [34].

- Post-light Radical Trapping: Engineering defect levels in the catalyst to trap photogenerated radicals (e.g., ·CH(2)OH from methanol reforming) can enable continued H(2) production even after illumination ceases. This process can lead to a "current doubling effect," where a single photon ultimately generates two electrons, pushing the apparent quantum yield beyond 100% under intermittent light conditions [16].

Q2: My CZS-based photocatalyst shows high initial activity but rapidly deactivates. What could be the cause and solution?

A: Photo-corrosion is a common issue for sulfide-based photocatalysts like CZS.

- Cause: The photogenerated holes accumulate and oxidize the sulfide material itself, leading to decomposition [34].

- Solution: Constructing a charge-separating heterojunction is a proven remedy. For example, in a Cd({0.5})Zn({0.5})S/Bi(2)WO(6) S-scheme heterojunction, the holes in CZS efficiently recombine with electrons from Bi(2)WO(6). This mechanism not only enhances charge separation but also effectively inhibits photo-corrosion, guaranteeing high photochemical stability. One study reported no activity decay even after half a year [34] [35].

Q3: Why does my Ni-modified CZS catalyst lose efficiency after the first illumination cycle?

A: The deactivation mechanism can depend on the preparation method of the Ni cocatalyst.

- Observation: One study found that a catalyst where NiS was precipitated onto the surface (CZS-10Ni-S) lost about half its efficiency upon reuse. In contrast, a catalyst prepared via the impregnation method (CZS-10Ni-I) saw a slight activity increase in the second cycle [33].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If facing stability issues, consider the impregnation method for Ni(OH)(2) deposition. The underlying mechanism suggests that Ni(OH)(2) is oxidized during the reaction, acting as a sacrificial hole trap. The impregnation method might create a more robust or regenerable interface. Also, avoid unnecessary hydrothermal treatment of the final Ni-modified catalyst, as it can cause particle agglomeration (Ostwald ripening) and reduce activity [33].

The following table summarizes key performance data from recent studies on modified Cd({0.5})Zn({0.5})S photocatalysts.

Table 1: Performance of Modified Cd({0.5})Zn({0.5})S Photocatalysts for H(_2) Evolution

| Modification Strategy | Co-catalyst/Synergist | Sacrificial Agent | Light Source | H(_2) Evolution Rate | Quantum Efficiency | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocatalyst Loading & Surface Adsorption | Amorphous CoS & S(^{2-}) ions | Not Specified | Visible Light | Significantly enhanced | Not Specified | [32] |

| Ni(II) Impregnation | Ni(OH)(_2) | Na(2)S/Na(2)SO(_3) | 415 nm LED | 170 mmol/h/g | 15.8% @ 415 nm | [33] |

| Z-scheme Heterojunction | BiVO(_4) | None (overall water splitting) | Visible Light (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 2.35 mmol/g/h | 24.1% @ 420 nm | [35] |

| S-scheme Heterojunction | Bi(2)WO(6) | Not Specified (for antibiotic degradation) | Visible Light | Enhanced redox efficiency | Not Specified | [34] |

| Post-light Radical Trapping | K-PHI (Carbon Nitride) | Methanol | 360 nm LED | Sustained production in dark | 132% (apparent) | [16] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This simple, effective method produces a highly active catalyst without costly thermal treatment.

- Objective: To deposit a Ni(OH)(2) cocatalyst on pre-synthesized Cd({0.5})Zn(_{0.5})S (CZS) via ion adsorption.

- Materials:

- Pre-synthesized Cd({0.5})Zn({0.5})S (CZS) powder

- Nickel precursor (e.g., Ni(NO(3))(2)·6H(2)O)

- Deionized water

- Sodium Sulfide (Na(2)S)

- Centrifuge

- Procedure:

- Synthesize pristine CZS via a standard hydrothermal method using cadmium sulfate, zinc sulfate, and sodium sulfide as precursors [32].

- Disperse the pre-synthesized CZS powder in an aqueous solution containing the desired concentration of Ni(II) salt (e.g., 1% mol Ni relative to total Cd+Zn).

- Allow the suspension to stand undisturbed overnight at room temperature to facilitate Ni(^{2+}) ion adsorption onto the CZS surface.

- Separate the solid product by centrifugation and wash once to remove loosely bound Ni(II) ions.

- Re-disperse the recovered solid in water and add Na(2)S to precipitate the adsorbed Ni(II) as NiS/Ni(OH)(2) on the CZS surface. The final composite is denoted CZS-10Ni-I.

- Key Note: The study found that subsequent hydrothermal treatment of the final Ni-modified composite decreased activity by 40%, likely due to particle agglomeration [33].

This method creates a synergistic system with a cocatalyst for reduction and adsorbed species for oxidation.

- Objective: To anchor amorphous CoS cocatalysts on CZS while adsorbing S(^{2-}) ions to create a sulfur-rich surface.

- Materials:

- Pre-synthesized Cd({0.5})Zn({0.5})S (CZS) powder

- Cobaltous nitrate (Co(NO(3))(2))

- Sodium phosphate (Na(3)PO(4))

- Sodium Sulfide (Na(_2)S)

- Teflon autoclave

- Procedure:

- Prepare pristine CZS hydrothermally as in Protocol 1.

- Create a CZS suspension in deionized water.

- Add Co(NO(3))(2) and Na(3)PO(4) solutions to the suspension to form a cobaltous phosphate (CoPi) precursor on the CZS surface, resulting in a CoPi/CZS intermediate.

- Add Na(_2)S solution to the CoPi/CZS suspension and stir. The S(^{2-}) ions will transform the CoPi into amorphous CoS.

- Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 100°C for 1 hour to complete the transformation and adsorb S(^{2-}) ions.

- Collect the final product (CoS/CZS-S) by filtration, washing, and drying.

Charge Transfer Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the electron flow pathways in the highly effective systems described.

Diagram Title: Cocatalyst Charge Separation Mechanisms

Diagram Title: Dark Reaction Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for CZS Photocatalyst Modification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Key Note / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Cadmium Sulfate (CdSO₄) | Cd precursor for CZS solid solution | Forms the core photocatalyst with visible-light response [32]. |

| Zinc Sulfate (ZnSO₄) | Zn precursor for CZS solid solution | Tuning the bandgap and improving stability of CdS [32] [33]. |

| Sodium Sulfide (Na₂S) | S precursor & sacrificial agent | Source of S²⁻ for synthesis; also acts as a potent hole scavenger in the reaction solution [32] [33]. |

| Cobaltous Nitrate (Co(NO₃)₂) | Co precursor for CoS cocatalyst | Forms amorphous CoS upon sulfidation, a non-noble metal reduction cocatalyst [32]. |

| Nickel Nitrate (Ni(NO₃)₂) | Ni precursor for Ni-cocatalysts | Forms Ni(OH)₂/NiS on the surface, acting as an efficient hole trap [33]. |

| Sodium Sulfite (Na₂SO₃) | Sacrificial agent | Prevents oxidation of S²⁻ back to S(0) or other species, preserving the hole-scavenging capacity [33]. |

| Methanol (CH₃OH) | Sacrificial agent & radical source | Hole scavenger that generates ·CH₂OH radicals, crucial for post-light radical trapping mechanisms [16]. |

| BiVO₄ / Bi₂WO₆ | Heterojunction component | Forms S-scheme or Z-scheme heterojunctions with CZS for superior charge separation and anti-corrosion [34] [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are "post-light radical trapping" and the "current doubling effect," and why are they significant for quantum yield? A1: Post-light radical trapping refers to the ability of a photocatalytic material, such as carbon nitride, to continue catalytic activity after the light source has been turned off. This is enabled by material designs that can store photogenerated charges (e.g., electrons) during illumination and release them gradually in the dark to generate radicals, such as chlorine radicals for methane oxidation [36] [37]. The current doubling effect is a phenomenon where a single absorbed photon leads to the generation of more than one charge carrier (electron), potentially doubling the photocurrent. This occurs when photogenerated holes oxidize an electron donor, which then injects an additional electron into the conduction band of the photocatalyst [38]. Together, these mechanisms can significantly boost the overall efficiency and quantum yield of a photocatalytic process by maximizing the utilization of each photon and extending the reaction time beyond the irradiation period [36] [37].

Q2: My carbon nitride system shows promising activity under light but no post-light effects. What could be the cause? A2: A lack of post-light activity typically points to an issue with charge storage. The most common causes and their solutions are:

- Insufficient Trap States: The carbon nitride material may lack sufficient deep-level trap states (defects) to effectively capture and store photogenerated electrons. Introducing defect engineering through elemental doping can create these necessary traps [39].

- Missing Electron Storage Material (ESM): For effective "memory" photocatalysis, carbon nitride often needs to be coupled with a dedicated ESM. The ESM must have a conduction band positioned below that of carbon nitride to accept and store electrons [37]. Materials like WO₃ or Ni(OH)₂ are commonly used for this purpose [37].

- Rapid Recombination: Stored charges may be recombining too quickly in the dark to be effective. This can be mitigated by constructing heterojunctions (e.g., Type-II or Z-scheme) with other semiconductors to promote more stable charge separation [37] [39].

Q3: I am observing low Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) in my photolytic system. What key parameters should I investigate? A3: Low AQY indicates that the efficiency of converting photons into chemical reactions is poor. You should systematically investigate the following parameters, which are known to have strong interdependencies [36] [38]:

- Light Intensity and Wavelength: The relationship between reaction rate and light intensity is often non-linear. At very high intensities, you may see diminishing returns due to saturation effects or accelerated charge recombination [38]. Ensure the light wavelength matches the absorption profile of your photocatalyst.

- Catalyst Concentration: An optimal catalyst concentration exists. Too low, and light is not fully absorbed; too high, and light scattering reduces penetration and efficiency [38].

- Substrate Concentration and Adsorption: The surface coverage of the reactant on the catalyst (modeled by Langmuir isotherms) directly impacts the reaction rate. Low adsorption equilibrium constants (Kₐdₛ) can limit AQY [38].

- Charge Recombination Rate: A high charge recombination rate (kᵣ) is a primary culprit for low AQY. Strategies to suppress this include doping, heterojunction formation, and surface modification [38] [39].

Q4: How can I minimize the formation of unwanted chlorinated byproducts (e.g., CH₃Cl, CCl₄) in chlorine radical-mediated methane oxidation? A4: The production of undesirable byproducts is a critical challenge. Your strategy should focus on controlling reaction kinetics and conditions [36]:

- Optimize Radical Concentration: High local concentrations of chlorine radicals favor over-chlorination. You can manage this by tuning the UV light intensity and chlorine gas concentration to generate an optimal, lower radical concentration.

- Control Residence Time: Shortening the contact time between the methane/ intermediates and the chlorine radicals can limit successive chlorination reactions. This can be achieved by optimizing the airflow rate through the reactor [36].

- Reactor Design: Improve the homogeneity of light and reactant distribution in your reactor to prevent pockets of high radical concentration. Internal reflectors can be used to achieve a more uniform light field [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Low Quantum Yield

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Diagnostic Experiments | Solution & Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low activity under both low and high light intensity. | Poor innate catalytic activity or rapid bulk charge recombination. | Perform fluorescence quenching experiments to assess recombination rates. Conduct control experiments with a sacrificial reagent to isolate half-reaction efficiency. | Enhance charge separation by constructing heterojunctions [39] or doping with metals (e.g., Cu, Mn) [39] / non-metals (e.g., S) [39]. |

| Activity saturates or decreases at high light intensities. | Dominance of charge recombination pathways at high photon flux. | Systematically measure reaction rate as a function of light intensity to map the kinetic regime [38]. | Operate at an light intensity below saturation or re-design the catalyst to have a higher kinetic limit (e.g., increase k* via surface modification) [38]. |

| Good initial activity that rapidly decays. | Catalyst poisoning, fouling, or photo-corrosion. | Characterize the catalyst post-reaction (XPS, FTIR) for surface species. Test catalyst reusability over multiple cycles. | Introduce surface functional groups (e.g., via halide ion modification with HBr) to create more robust active sites and prevent deactivation [39]. |

| Low AQY specifically for methane oxidation. | Inefficient chlorine radical generation or utilization. | Measure the system's AQY for chlorine radical generation. Quantify the dependence on wavelength and chlorine concentration [36]. | Optimize UV light wavelength and reactor reflectance. The current state-of-the-art AQY for this reaction is 0.83%, with a target of 9% for cost-effectiveness [36]. |

Guide 2: Optimizing for Post-Light Activity

| Target Property | Material Design Strategy | Experimental Protocol for Validation | Key Performance Indicator (KPI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Storage Capacity | Form a composite with an Electron Storage Material (ESM) like WO₃ or Ni(OH)₂. The ESM's conduction band must be below that of carbon nitride [37]. | Synthesize via in-situ growth or impregnation. After illumination, monitor H₂ evolution in the dark or use spectroscopic methods (e.g., UV-Vis) to observe color changes from reduced species (e.g., blue HₓWO₃) [37]. | Duration and rate of hydrogen production or pollutant degradation in the dark post-irradiation. |

| Long-Lived Charge Traps | Introduce defect states via elemental doping (e.g., with transition metals) or create nitrogen vacancies during synthesis. | Use techniques like Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) to detect and quantify trapped electrons before and after light is turned off. | The half-life of the trapped charges, measurable via the decay of the EPR signal or post-illumination catalytic activity. |

| Suppressed Dark Recombination | Integrate long-afterglow phosphors (e.g., Sr₂MgSi₂O₇:Eu,Dy) to provide delayed photon emission, or build Z-scheme heterojunctions [37]. | Measure afterglow luminescence spectra and decay kinetics. Compare the photocatalytic activity in the dark for systems with and without the phosphor. | The intensity and duration of the afterglow emission correlated with sustained catalytic turnover. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Holistic Kinetic Analysis of Photocatalytic Reactions

Objective: To move beyond one-dimensional analysis and accurately model the mutual interdependence of reaction parameters (light intensity, catalyst concentration, substrate concentration, temperature) on reaction rate and quantum yield [38].

Materials:

- Photocatalyst (e.g., doped carbon nitride)

- Substrate solution

- LED light source with adjustable intensity

- Photoreactor with temperature control

- Analytical instrument (e.g., GC, HPLC)

Procedure:

- Fix Baseline Conditions: Establish a set of standard conditions (e.g., catalyst loading: 0.5 g/L, substrate concentration: 0.1 mM, light intensity: 50 mW/cm², temperature: 25°C).

- Multi-Dimensional Variation: Systematically vary one parameter at a time while keeping the others constant at the baseline. For example:

- Measure initial rate (r) at light intensities: 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 mW/cm².

- Measure r at catalyst concentrations: 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 g/L.

- Measure r at substrate concentrations across a relevant range.

- Data Fitting: Fit the obtained data to a holistic kinetic model, such as the one based on local volumetric rate of photon absorption (LVRPA) [38]:

r = (φ · Lₚₐ · k* · θ · c₀) / (φ · Lₚₐ + kᵣ + k* · θ · c₀)where φ is quantum yield, Lₚₐ is LVRPA, k* is the normalized rate constant, θ is surface coverage, c₀ is catalyst mass, and kᵣ is recombination rate. - Regime Identification: Analyze the fitted data to identify whether the reaction is operating in a light-limited regime (rate scales linearly with intensity) or a kinetic-limited regime (rate plateaus at high intensity) [38]. This informs the optimal conditions for maximizing AQY.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Carbon Nitride/WO₃ "Memory" Photocatalyst for Post-Light H₂ Evolution

Objective: To synthesize a composite photocatalyst capable of producing hydrogen from water in the dark after a period of light charging [37].

Synthesis Methodology: