Beyond the F1 Score: Mastering Precision and Recall for Automated Chemical Data Extraction

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of precision and recall metrics in the context of automated chemical data extraction for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Beyond the F1 Score: Mastering Precision and Recall for Automated Chemical Data Extraction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of precision and recall metrics in the context of automated chemical data extraction for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental importance of these metrics for building reliable AI-driven chemistry databases, examines cutting-edge methodologies from multimodal large language models to vision-language models, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. The content further delves into validation frameworks and comparative performance of state-of-the-art systems, synthesizing key takeaways and future implications for accelerating biomedical and clinical research through high-quality, machine-actionable chemical knowledge.

Why Precision and Recall Are Non-Negotiable in Chemical AI

In the field of automated chemical data extraction, the performance of information retrieval systems is quantitatively assessed using three core metrics: precision, recall, and the F1 score [1] [2] [3]. These metrics provide a standardized framework for evaluating how effectively computational models can identify and extract chemical entities—such as compound names, reactions, and properties—from unstructured scientific text and figures [4] [5]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these metrics is crucial for selecting appropriate tools and methodologies for data curation tasks. Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions, answering the question: "Of all the chemical entities the model identified, how many were actually correct?" [1] [3]. Recall, also known as sensitivity, measures the model's ability to find all relevant instances, answering: "Of all the true chemical entities present, how many did the model successfully identify?" [1] [3]. The F1 score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single balanced metric that is particularly valuable when dealing with imbalanced datasets common in chemical literature [1] [2].

The trade-off between precision and recall is a fundamental consideration in chemical information extraction [2] [3]. Optimizing for precision minimizes false positives (incorrectly labeling non-chemical text as chemical entities), which is essential when accuracy of extracted data is paramount. Optimizing for recall minimizes false negatives (missing actual chemical entities), which is crucial when comprehensive data collection is the priority [2]. In drug development contexts, the preferred balance depends on the specific application—early-stage discovery may prioritize recall to ensure no potential compounds are overlooked, while late-stage validation may emphasize precision to avoid false leads [3].

Performance Comparison of Chemical Data Extraction Systems

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of various chemical data extraction systems as reported in recent scientific literature:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Chemical Data Extraction Systems

| System/Approach | Extraction Focus | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRF-based NER [4] | Chemical NEs | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.89 | [4] |

| CRF-based NER [4] | Proteins/Genes | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.85 | [4] |

| nanoMINER [5] | Nanozyme Kinetic Parameters | 0.98 | N/R | N/R | [5] |

| nanoMINER [5] | Nanomaterial Coating MW | 0.66 | N/R | N/R | [5] |

| OpenChemIE [6] | Document-Level Reactions | N/R | N/R | 0.695 | [6] |

| Librarian of Alexandria [7] | General Chemical Data | ~0.80 | N/R | N/R | [7] |

Note: N/R indicates the specific metric was not explicitly reported in the source material.

The comparative data reveals significant variation in performance across different extraction tasks and methodologies. Traditional machine learning approaches, such as the Conditional Random Fields (CRF) method, demonstrate robust performance with F1 scores between 0.85-0.89 for recognizing chemical named entities (NEs) and proteins/genes [4]. More recently developed multi-agent systems like nanoMINER achieve exceptional precision (0.98) for extracting specific nanozyme kinetic parameters, though performance varies across different material properties [5]. The OpenChemIE toolkit achieves an F1 score of 69.5% on the challenging task of extracting complete reaction data with R-group resolution from full documents [6]. These metrics provide crucial benchmarks for researchers when selecting extraction approaches suited to their specific chemical data needs.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CRF-based Named Entity Recognition

The CRF-based named entity recognition approach evaluated in Table 1 employed a meticulously designed experimental protocol [4]. Researchers utilized annotated text corpora including CHEMDNER and ChemProt, which contain thousands of annotated article abstracts [4]. The CHEMDNER corpus consists of 10,000 abstracts with annotations specifying entity position and type (e.g., ABBREVIATION, FAMILY, FORMULA, SYSTEMATIC, TRIVIAL) [4]. The methodology involved several stages: corpus collection and preprocessing, algorithm development and parameter optimization, and finally validation and testing [4].

Text preprocessing employed tokenization using the "wordpunct_tokenize" function from the NLTK Python library, splitting text into elementary units (tokens) [4]. The SOBIE labeling system (Single, Begin, Inside, Outside, End) identified entity positions within tokenized text [4]. The CRF algorithm itself was configured with carefully selected word features to enable context consideration. Validation was performed on two case studies relevant to HIV treatment: extraction of potential HIV inhibitors and proteins/genes associated with viremic control [4]. This specific biological context demonstrates how domain-focused extraction can yield highly relevant entity sets for targeted research applications.

Multi-Agent Nanomaterial Extraction (nanoMINER)

The nanoMINER system employs a sophisticated multi-agent architecture for extracting structured data from nanomaterial literature [5]. The experimental workflow begins with processing input PDF documents using specialized tools to extract text, images, and plots [5]. The system utilizes a YOLO model for visual data extraction to detect and identify objects within images (figures, tables, schemes), with extracted visual information then analyzed by GPT-4o to link visual and textual information [5].

The core of the system is a ReAct agent based on GPT-4o that orchestrates specialized agents [5]. The textual content undergoes strategic segmentation into 2048-token chunks to facilitate efficient processing [5]. The system employs an NER agent based on fine-tuned Mistral-7B and Llama-3-8B models, specifically trained to extract essential classes from nanomaterial articles [5]. A dedicated vision agent based on GPT-4o enables precise processing of graphical images and non-standard tables that standard PDF text extraction tools cannot parse [5]. The system was evaluated on two datasets: one focusing on general nanomaterial characteristics (formula, size, surface modification, crystal system) and another focusing on experimental properties characterizing enzyme-like activity [5].

Multi-Modal Chemical Reaction Extraction (OpenChemIE)

OpenChemIE implements a comprehensive pipeline for extracting reaction data at the document level by combining information across text, tables, and figures [6]. The system approaches the problem in two primary stages: extracting relevant information from individual modalities, then integrating results to obtain a final list of reactions [6]. For the first stage, it employs specialized neural models for specific chemistry information extraction tasks, including parsing molecules or reactions from text or figures [6].

The integration phase employs chemistry-informed algorithms to combine information across modalities, enabling extraction of fine-grained reaction data from reaction condition and substrate scope investigations [6]. Key innovations include: a machine learning model to associate molecules depicted in diagrams with their text labels (multimodal coreference resolution), alignment of reactions with reaction conditions presented in tables/figures/text, and R-group resolution by comparing molecules with the same label and substituting them with additional substructures from substrate scope tables [6]. The system was evaluated on a manually curated dataset of 1007 reactions from 78 substrate scope figures across five organic chemistry journals, requiring correct prediction of all reaction components and R-group resolution [6].

Visualizing Metric Relationships and System Workflows

Relationship Between Precision, Recall, and F1 Score

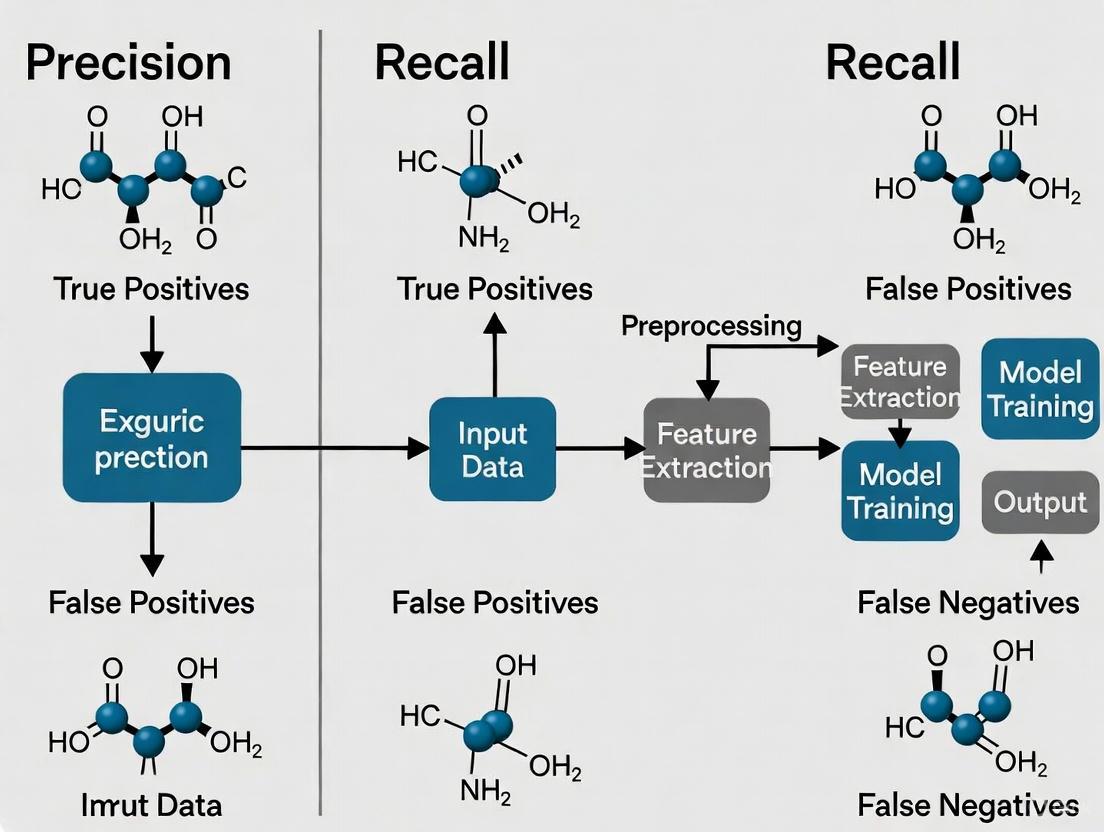

Diagram 1: Metric Calculation Relationships

This diagram illustrates how precision, recall, and F1 score are derived from fundamental classification outcomes: true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). The F1 score serves as the harmonic mean that balances the competing priorities of precision and recall.

Workflow of a Multi-Agent Chemical Extraction System

Diagram 2: Multi-Agent Extraction Workflow

This workflow depicts the architecture of advanced chemical data extraction systems like nanoMINER [5]. The coordinated multi-agent approach enables comprehensive processing of diverse data modalities within scientific documents, with specialized components handling specific extraction tasks under the orchestration of a central ReAct agent.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHEMDNER Corpus [4] | Annotated Dataset | Training and benchmarking chemical NER systems | Provides 10,000 annotated abstracts with chemical entity labels [4] |

| ChemProt Corpus [4] | Annotated Dataset | Training joint extraction of chemicals and proteins/genes | Contains 2,482 abstracts with normalized entity annotations [4] |

| Conditional Random Fields [4] | Machine Learning Algorithm | Probabilistic model for sequence labeling | Traditional approach for chemical NER with proven efficacy [4] |

| YOLO Model [5] | Computer Vision Tool | Object detection in figures and schematics | Identifies and extracts visual elements from scientific images [5] |

| GPT-4o [5] | Multimodal LLM | Text and visual information processing | Core reasoning engine in multi-agent extraction systems [5] |

| Mistral-7B/Llama-3-8B [5] | Fine-tuned LLMs | Specialized named entity recognition | Domain-adapted models for chemical concept extraction [5] |

| OpenChemIE [6] | Integrated Toolkit | Multi-modal reaction data extraction | Combines text, table, and figure processing for comprehensive extraction [6] |

This toolkit represents essential resources mentioned in the evaluated studies that enable the development and deployment of automated chemical data extraction systems. The annotated corpora (CHEMDNER and ChemProt) provide foundational training data for developing domain-specific models [4]. The machine learning algorithms range from traditional CRF approaches to modern fine-tuned LLMs, each offering different trade-offs between precision, computational requirements, and adaptability [4] [5]. The integration of computer vision tools like YOLO with multimodal LLMs enables the processing of chemical information presented in diverse formats, addressing a critical challenge in comprehensive chemical data extraction [5].

Precision, recall, and F1 score provide the essential quantitative framework for evaluating chemical data extraction systems in scientific and pharmaceutical contexts. The comparative data reveals that while traditional CRF-based approaches maintain strong performance (F1 scores of 0.85-0.89), emerging multi-agent and multimodal systems are achieving remarkable precision for specific extraction tasks, such as nanoMINER's 0.98 precision for kinetic parameters [4] [5]. The experimental protocols demonstrate increasing sophistication in methodology, from single-modality text processing to integrated systems that combine text, visual, and tabular data extraction [4] [5] [6].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these metrics and methodologies offer critical guidance for selecting appropriate extraction tools based on specific research needs. Applications requiring high confidence in extracted data may prioritize systems with demonstrated high precision, while comprehensive literature mining tasks may benefit from approaches with optimized recall characteristics. As chemical data extraction continues to evolve, these metrics will remain fundamental for assessing technological advancements and their practical applications in accelerating chemical research and drug discovery.

Artificial intelligence (AI) stands poised to revolutionize drug development, promising to dramatically compress the traditional decade-long path from molecular discovery to market approval [8]. This technological transformation manifests across the entire drug development continuum, from AI systems identifying novel drug targets and predicting molecular properties to algorithms optimizing clinical trial design and monitoring patient safety [8]. However, AI's efficacy hinges entirely on the quality and management of data [9]. In the pharmaceutical context, this data extends far beyond traditional numbers and lists, encompassing diverse unstructured information including images, sounds, and continuous values collected from various systems [9].

The journey to effective AI implementation is heavily weighted toward data preparation, consuming an estimated 80% of an AI project's time [9]. This rigorous preparation ensures that data are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable—following the FAIR principles essential for quality AI outcomes [9]. As more data is integrated, the potential for knowledge extraction and sophisticated AI models increases, yet this also adds layers of complexity to data and model management [9]. Within this ecosystem, automated chemical data extraction systems serve as critical gatekeepers, where their performance—measured through precision and recall metrics—directly controls the quality of the entire AI-driven drug discovery pipeline.

The Critical Link Between Data Extraction and AI Outcomes

Quantitative Performance of Automated Extraction Systems

Automated chemical data extraction systems represent a pivotal innovation for managing the vast volumes of safety and chemical information essential for pharmaceutical research. The process of extracting and structuring essential information from documents, known as "indexing," is a critical task for inventory management and regulatory compliance that has traditionally been done manually [10]. Manual SDS (Safety Data Sheet) indexing can be resource-intensive, requiring personnel to process each document individually, often resulting in significant costs and extended processing times [10].

Recent advances in automated systems demonstrate the performance levels achievable through sophisticated machine learning approaches. One proposed system for standard indexing of SDS documents utilizes a multi-step method with a combination of machine learning models and expert systems executed sequentially [10]. This system specifically extracts the fields Product Name, Product Code, Manufacturer Name, Supplier Name, and Revision Date—five fields commonly needed across various applications [10].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of an Automated Chemical Data Extraction System

| Extraction Field | Precision Score | Impact on Drug Discovery Processes |

|---|---|---|

| Product Name | 0.96-0.99 | Accurate compound identification enables reliable target prediction |

| Product Code | 0.96-0.99 | Precise tracking ensures batch-to-batch consistency in experimental materials |

| Manufacturer Name | 0.96-0.99 | Supply chain verification affects reproducibility of research findings |

| Supplier Name | 0.96-0.99 | Sourcing information critical for material quality assessment |

| Revision Date | 0.96-0.99 | Version control ensures use of most current safety and property data |

When evaluated on 150,000 SDS documents annotated for this purpose, this design achieves a precision range of 0.96-0.99 across the five fields [10]. This high precision rate is crucial for pharmaceutical applications where extraction errors can propagate through the entire research and development pipeline, potentially compromising drug discovery outcomes and synthesis predictions.

Consequences of Extraction Errors in Pharmaceutical Contexts

Even with high-performance systems, minimal error rates in data extraction can have profound consequences in drug discovery environments. Even a 1-4% error rate—seemingly small in isolation—can translate to significant problems when scaled across thousands of compounds and data points [10]. Regulators are keenly aware of this issue, frequently referencing data and metadata in AI guidelines and emphasizing their critical role in transforming raw information into actionable knowledge [9]. This focus is not without reason, as more than 25% of warning letters issued by the FDA since 2019 have cited data accuracy issues—a complex problem that continues to challenge the industry [9].

The stakes of extraction errors are particularly high in specific pharmaceutical applications:

AI-driven compound screening relies on harmonized assay data from multiple labs, allowing prediction of toxicity and efficacy with higher precision [11]. Extraction errors in compound identifiers or structural information can lead to flawed predictions that waste resources and delay promising drug candidates.

Plasma fractionation processes utilize AI to integrate batch record information with data from other systems, such as programmable logic controllers and online controls [9]. Errors in extracting process parameters can compromise the AI's ability to guarantee expected yields of critical biopharmaceutical products.

Advanced therapy medicinal products benefit from AI applications for quality control, allowing for the prediction of batch success an hour in advance [9]. Extraction inaccuracies in quality metrics could undermine this predictive capability, reducing the lead time for crucial decision-making in manufacturing these sensitive therapies.

Experimental Framework: Evaluating Extraction Methodologies

Protocol for Assessing Extraction System Performance

The evaluation of automated chemical data extraction systems requires rigorous experimental design centered on precision and recall metrics. The following methodology provides a framework for assessing system performance under conditions relevant to drug discovery applications.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Extraction System Validation

| Experimental Phase | Methodology | Key Metrics | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Curation | Annotate 150,000+ SDS documents with expert-verified labels | Dataset diversity, annotation consistency | Cross-validation by multiple domain experts |

| System Training | Implement multi-step ML models with expert systems | Training accuracy, loss convergence | k-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting |

| Precision Testing | Evaluate extraction accuracy across key fields | Precision scores (0.96-0.99 target) | Confidence intervals for each field type |

| Recall Assessment | Measure completeness of extracted information | Recall rates, F1 scores | Analysis of false negatives by field category |

| Impact Analysis | Track error propagation through drug discovery simulations | Error amplification factors | Controlled introduction of extraction errors |

The experimental protocol requires specialized research reagents and solutions to ensure reproducible and valid results:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Extraction Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Annotated SDS Dataset | Gold-standard reference for training and validation | Diversity of sources, expert verification, comprehensive coverage |

| Domain-Specific Ontologies | Standardized terminology for chemical entities | Alignment with regulatory standards (CDISC), interoperability |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-throughput processing of documents | Processing speed, parallelization capability, memory capacity |

| Quality Metrics Framework | Quantitative assessment of extraction accuracy | Precision, recall, F1 scores, domain-specific validation |

| Error Analysis Toolkit | Identification and classification of extraction failures | Error categorization, root cause analysis, impact assessment |

Workflow Visualization: From Data Extraction to Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow, from initial data extraction through to final application in drug discovery contexts, highlighting critical points where extraction quality must be validated:

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Expectations

Transatlantic Regulatory Landscapes for AI and Data Quality

The regulatory environment for AI applications in drug development exhibits significant transatlantic differences, with implications for how data quality and extraction processes are governed. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have adopted notably different approaches to oversight, reflecting broader differences in their regulatory philosophies and institutional contexts [8].

Table 4: Comparative Analysis of FDA and EMA Approaches to AI and Data Governance

| Regulatory Aspect | FDA Approach (United States) | EMA Approach (European Union) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Philosophy | Flexible, case-specific model encouraging innovation via individualized assessment [8] | Structured, risk-tiered approach providing more predictable paths to market [8] |

| Data Quality Framework | Incorporation of new executive orders with focus on practical implementation [8] | Alignment with EU's AI Act and comprehensive technological oversight [8] |

| Validation Requirements | Dialog-driven model that can create uncertainty about general expectations [8] | Clearer requirements that may slow early-stage AI adoption but provide predictability [8] |

| Technical Specifications | Case-by-case evaluation with emerging patterns from 500+ submissions incorporating AI components [8] | Mandates for traceable documentation, data representativeness assessment, and bias mitigation [8] |

| Post-Authorization Monitoring | Evolving framework with significant discretion in application | Permits continuous model enhancement but requires ongoing validation within pharmacovigilance systems [8] |

The EMA's framework introduces a risk-based approach that focuses on 'high patient risk' applications affecting safety and 'high regulatory impact' cases where substantial influence on regulatory decision-making exists [8]. This calibrated oversight system places explicit responsibility on clinical trial sponsors, marketing authorization applicants/holders, and manufacturers to ensure AI systems are fit for purpose and aligned with legal, ethical, technical, and scientific standards [8].

Data Governance Imperatives for Regulatory Compliance

Both regulatory frameworks increasingly emphasize the importance of robust data governance as a foundation for reliable AI applications in drug development. The technical requirements under the EMA framework are comprehensive, mandating three key elements: (1) traceable documentation of data acquisition and transformation, (2) explicit assessment of data representativeness, and (3) strategies to address class imbalances and potential discrimination [8]. The EMA expresses a clear preference for interpretable models but acknowledges the utility of black-box models when justified by superior performance [8].

The following diagram illustrates the essential data governance framework necessary to meet evolving regulatory expectations:

For regulatory engagement, the EMA establishes clear pathways through its Innovation Task Force for experimental technology, Scientific Advice Working Party consultations, and qualification procedures for novel methodologies [8]. These mechanisms facilitate early dialogue between developers and regulators, particularly crucial for high-impact applications where regulatory guidance can significantly influence development strategy [8]. Similarly, the FDA's evolving approach, despite creating more uncertainty, aims to maintain flexibility in addressing innovative AI applications while ensuring patient safety [8].

The integration of high-precision automated data extraction systems represents a foundational element in the AI-driven transformation of drug discovery. The demonstrated precision rates of 0.96-0.99 for chemical data extraction establish a performance baseline that directly impacts the reliability of subsequent AI models for synthesis prediction and compound evaluation [10]. As regulatory frameworks continue to evolve on both sides of the Atlantic, the emphasis on data quality, traceability, and governance will only intensify [8] [9].

Organizations that treat data as a strategic asset rather than a byproduct, implementing robust data governance frameworks aligned with FAIR principles, will be best positioned to leverage AI's full potential across the drug development continuum [11]. The systematic management of data quality—from initial extraction through to regulatory submission—serves not only as a compliance necessity but as a genuine competitive differentiator in the increasingly AI-driven landscape of pharmaceutical innovation [11]. Those who excel in this integration will realize faster discovery cycles, improved model reliability, and enhanced regulatory confidence, ultimately accelerating the delivery of transformative therapies to patients.

The vast majority of chemical knowledge resides within unstructured natural language text—scientific articles, patents, and technical reports—creating a significant bottleneck for data-driven research in chemistry and materials science [12]. The exponential growth of chemical literature further intensifies this challenge, making automated extraction not merely convenient but essential for keeping pace with information surge [13]. Unlike many other scientific domains, chemical information extraction faces unique complexities due to the lack of a standardized representation system for chemical entities [13]. Chemical names appear in diverse forms including systematic nomenclature, trivial names, database identifiers, and chemical formulas, each with distinct structural and semantic characteristics [13]. This review objectively compares the performance of various chemical data extraction technologies, framing the analysis within the critical context of precision and recall metrics to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate tools for their specific applications.

Fundamental Challenges in Chemical Information Extraction

Chemical Named Entity Recognition (CNER) presents particular difficulties due to the intricate and inconsistent nature of chemical nomenclature. Several key challenges complicate automated extraction:

Nomenclature Complexity: Chemical names often include specialized delimiters such as hyphens, commas, and parentheses (e.g., N,N-dimethylformamide or 1,2-dichloroethane), which frequently interfere with standard tokenization processes, resulting in entity fragmentation or misidentification during text analysis [13].

Entity Ambiguity and Nesting: The presence of overlapping and nested entities, combined with the co-occurrence of unrelated non-chemical terms in scientific texts, substantially complicates the accurate identification and classification of chemical entities [13].

Multi-modal Data Integration: Comprehensive chemical understanding often requires processing textual, visual, and structural information in a unified way, presenting additional extraction challenges [14].

These challenges necessitate specialized approaches that go beyond conventional natural language processing techniques, requiring either domain-specific tool development or advanced artificial intelligence systems capable of understanding chemical context.

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Technologies

Traditional and Specialized Chemical Extraction Tools

Traditional approaches to chemical data extraction have relied on rule-based methods, smaller machine learning models trained on manually annotated corpora, and specialized domain-specific tools [12]. These include systems such as ChemicalTagger, ChemEx, ChemDataExtractor, and others specifically designed for parsing chemical roles and relationships [13] [15].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional CNER Tools

| Tool | Precision (p75) | Recall | F1-Score | Primary Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChemDE | 0.851 | 0.854 | Not reported | Biochemical entities |

| Chemspot | Not reported | Not reported | Balanced F1 | General chemical entities |

| CheNER | Lower than ChemDE | Not reported | Lower F1 | Not specified |

These specialized tools often demonstrate a strong balance between precision and recall, with ChemDE particularly notable for maintaining high precision (0.851 at p75) while achieving a high recall rate of 0.854, indicating its ability to identify a large proportion of chemical entities in text [13]. However, these approaches typically face challenges with the diversity of topics and reporting formats in chemistry and materials research as they are hand-tuned for very specific use cases [12].

Large Language Models in Chemical Data Extraction

The advent of large language models (LLMs) represents a significant shift in the chemical data extraction landscape, potentially enabling more flexible and scalable information extraction from unstructured text [12]. Unlike traditional approaches that require extensive development time for each new use case, LLMs can solve chemical extraction tasks without explicit training for those specific applications [12].

Table 2: LLM Performance in Chemical Data Extraction Tasks

| Model/Approach | Overall Accuracy | F1-Score (CNER) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek-V3-0324 | 0.82 | Not reported | Highest accuracy in piezoelectric data extraction |

| Fine-tuned LLaMA-2 + RAG | Not reported | 0.82 | Surpasses traditional CNER tools |

| General LLM baseline (2-day hackathon) | Prototype viable | Not reported | Rapid prototyping capability |

Comparative studies reveal that fine-tuned LLaMA-2 models with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) techniques achieve F1 scores of 0.82, surpassing the performance of traditional CNER tools [13]. Interestingly, increasing model complexity from 1 billion to 7 billion parameters does not significantly affect performance, suggesting that appropriate tuning and augmentation strategies may be more important than raw model size for chemical extraction tasks [13].

In specific applications such as extracting composition-property data for ceramic piezoelectric materials, DeepSeek-V3-0324 has demonstrated superior performance with overall accuracy reaching 0.82 when evaluated against 100 journal articles [15].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Rigorous evaluation of chemical data extraction tools relies on standardized datasets and benchmarking frameworks. The BioCreative challenges have served as important community-wide efforts for evaluating text mining and information extraction systems applied to the biological and chemical domains [16]. These challenges provide "gold standard" data derived from life science literature that has been examined by biological database curators and domain experts [16].

Key benchmark datasets include:

NLM-Chem Corpus: Comprises 150 full-text articles annotated by ten expert indexers, with approximately 5000 unique chemical name annotations mapped to around 2000 MeSH identifiers [13] [16].

BioRED Dataset: Contains 1000 MEDLINE articles fully annotated with biological and medically relevant entities, biomedical relations between them, and annotations regarding the novelty of the relation [16].

CHEMDNER Corpus: Focuses on chemical entity recognition in both PubMed abstracts and patent abstracts, supporting the development and evaluation of chemical named entity recognition systems [16].

These datasets enable standardized comparison of extraction tools using precision, recall, and F1-score metrics, providing objective performance assessments across different system architectures.

Experimental Workflow for Extraction System Evaluation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for evaluating chemical data extraction systems, synthesizing methodologies from multiple studies:

Experimental Evaluation Workflow

This standardized workflow enables fair comparison between diverse extraction approaches, from traditional CNER tools to modern LLM-based systems. The process begins with selecting appropriate benchmark datasets with expert annotations, proceeds through systematic execution of extraction tools, and concludes with calculation of standard information retrieval metrics.

Advanced Architectures and Methodologies

Multi-Agent Extraction Frameworks

Recent advances in chemical data extraction have introduced sophisticated multi-agent frameworks that distribute specialized tasks across coordinated AI agents. The ComProScanner system exemplifies this approach, implementing an autonomous multi-agent platform that facilitates the extraction, validation, classification, and visualization of machine-readable chemical compositions and properties integrated with synthesis data from journal articles [15].

The ComProScanner architecture operates through four distinct phases:

- Metadata Retrieval: The system finds relevant article metadata using property-related search terms through APIs such as the Scopus Search API [15].

- Article Collection: The system accesses full-text articles through publisher-provided Text and Data Mining (TDM) APIs or local PDF files, performing preliminary keyword-based filtration to identify articles mentioning target properties [15].

- Information Extraction: Specialized AI agents extract structured data including chemical compositions, property values, material families, synthesis methods, precursors, and characterization techniques [15].

- Evaluation and Post-processing: Extracted data undergoes validation, relationship establishment, and preparation for database creation [15].

This distributed approach allows for more comprehensive extraction than monolithic systems, with different agents specializing in specific aspects of the chemical information landscape.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation and Fine-tuning

Two particularly effective methodologies for enhancing LLM performance in chemical data extraction are:

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): This approach enhances extraction accuracy by providing LLMs with access to relevant contextual information from authoritative chemical databases or the source documents themselves. RAG has been shown to significantly improve performance, particularly for complex extraction tasks requiring specialized domain knowledge [13] [15].

Domain-Specific Fine-tuning: Adapting general-purpose LLMs through continued training on chemical literature, patents, and structured databases significantly enhances their performance on chemical extraction tasks. Fine-tuned models demonstrate improved understanding of chemical nomenclature and relationships [13].

The following diagram illustrates how these advanced methodologies integrate into a complete chemical data extraction pipeline:

Advanced Chemical Data Extraction Pipeline

Successful chemical data extraction requires both computational tools and curated data resources. The following table details key solutions used in the development and evaluation of chemical information extraction systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Data Extraction

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLM-Chem Corpus | Annotated dataset | Gold standard for training and evaluating chemical entity recognition | Benchmarking CNER tool performance [13] [16] |

| BioRED Dataset | Relation extraction corpus | Evaluating chemical-protein and other biomedical relations | Testing relation extraction capabilities [16] |

| CHEMDNER Corpus | Chemical entity corpus | Developing and evaluating chemical named entity recognition | Training domain-specific NER models [16] |

| Scopus Search API | Metadata service | Retrieving relevant scientific literature | Identifying target articles for extraction [15] |

| Publisher TDM APIs | Content access | Automated retrieval of full-text articles | Large-scale content processing [15] |

| ChromaDB | Vector database | Storing and retrieving document embeddings | Enabling efficient RAG implementation [15] |

These resources provide the foundational elements required for developing, testing, and deploying chemical data extraction systems in both research and production environments.

The comparative analysis of chemical data extraction technologies reveals a rapidly evolving landscape where traditional domain-specific tools and modern LLM-based approaches each offer distinct advantages. Traditional CNER tools like ChemDE and Chemspot provide reliable, optimized performance for specific extraction tasks with well-balanced precision and recall metrics. Meanwhile, LLM-based approaches offer greater flexibility, faster prototyping capabilities, and competitive performance—particularly when enhanced with RAG and fine-tuning strategies.

The integration of multi-agent frameworks represents a promising direction for addressing the complex, multi-step nature of comprehensive chemical data extraction, moving beyond simple entity recognition to encompass relationship extraction, synthesis protocol interpretation, and multi-modal data integration. As these technologies continue to mature, their potential to transform how researchers access and utilize the vast chemical knowledge embedded in scientific literature grows accordingly, ultimately accelerating the development of novel compounds and materials for critical societal needs.

The field of chemical and biomedical research is undergoing a profound transformation in how scientific data is extracted and synthesized. The traditional, gold-standard method of manual double extraction, where two human experts independently extract data to minimize error, is increasingly being supplemented—and in some cases replaced—by AI-driven automated systems [17]. This shift is driven by the exponential growth of scientific literature and the need for faster, yet still reliable, evidence synthesis in areas like drug development and materials discovery [18].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various automated extraction approaches, framing the analysis within the critical academic thesis of precision and recall metrics. For researchers and scientists, the move from manual curation to automation is not merely about speed; it is about achieving a scalable, reproducible, and accurate data pipeline that maintains the rigor required for high-stakes decision-making [19].

Quantitative Performance Landscape

Benchmarking studies reveal significant variability in the performance of AI tools, with specialized systems often outperforming general-purpose models on scientific tasks. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI Data Extraction Systems

| AI Tool / System | Domain / Task | Reported Metric | Performance Value | Context / Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISE [18] | Scientific Literature Analysis | ECACT Score (Extraction) | 9.2/10 | Average across 9 articles; outperformed other AI tools. |

| ECACT Score (Comprehension) | 8.9/10 | |||

| ECACT Score (Analysis) | 8.5/10 | |||

| ML Pipeline (SBERT) [20] | Outcome Extraction (Medical) | F1-Score | 94% | Trained on 20 articles; benchmarked against manual extraction. |

| Precision | >90% | |||

| Recall | >90% | |||

| FSL-LLM Approach [21] | Mortality Cause Extraction (GoFundMe) | Accuracy (Primary Cause) | 95.9% | Compared to human annotator accuracy of 97.9%. |

| Mortality Cause Extraction (Obituaries) | Accuracy (Primary Cause) | 96.5% | Compared to human accuracy of 99%. | |

| Claude 3.5 [17] | Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews | Accuracy (Study Protocol) | Pending | RCT ongoing; results expected 2026. |

| General-Purpose AI (e.g., ChatGPT) [18] | Scientific Literature Analysis | ECACT Score (Extraction) | Moderate | Efficient in data retrieval but lacks precision in complex analysis. |

The data illustrates that while even advanced AI tools have not fully closed the gap with human expert accuracy, several specialized systems are demonstrating expert-level performance in specific, well-defined extraction tasks [21] [20]. The performance of a tool is highly dependent on the domain, with complex chemical data presenting persistent challenges [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Understanding the experimental design behind these performance metrics is crucial for assessing their validity. The following section details the methodologies of key studies and benchmarks.

The ChemX Benchmark for Chemical Data

The ChemX benchmark was developed to rigorously evaluate agentic systems on the formidable challenge of automated chemical information extraction [19].

Table 2: Key Reagents in the ChemX Benchmarking Experiment

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| ChemX Datasets | Benchmark Data | A collection of 10 manually curated, domain-expert-validated datasets focusing on nanomaterials and small molecules to test extraction capabilities [19]. |

| GPT-5 / GPT-5 Thinking | Baseline Model | Modern large language models used as performance baselines against which specialized agentic systems are compared [19]. |

| ChatGPT Agent | Agentic System | A general-purpose agentic system evaluated on its ability to perform complex, multi-step chemical data extraction [19]. |

| Domain-Specific Agents | Agentic System | AI agents (e.g., chemistry-specific data extraction agents) designed with specialized knowledge to handle domain-specific terminology and representations [19]. |

| Single-Agent Preprocessing | Methodological Approach | A custom single-agent approach that enables precise control over document preprocessing prior to extraction, isolating this variable's impact [19]. |

The experimental workflow involved processing diverse chemical data representations through various agentic systems and baselines, with performance measured by accuracy in extracting structured information from unstructured text and complex tables.

ML for Core Outcome Set Development

A distinct ML pipeline was developed to automate the extraction and classification of verbatim outcomes from clinical studies for Core Outcome Set (COS) development [20]. The protocol demonstrates how minimal manual annotation can be leveraged for highly accurate automation.

Methodology:

- Dataset Preparation: 114 full-text studies on lower limb lengthening surgery were used. Noun phrases were extracted from "Results" and "Discussion" sections [20].

- Model Architecture: A two-stage pipeline was implemented:

- Outcome Extraction: A Sentence-BERT (SBERT) model was fine-tuned to perform binary classification, distinguishing outcome-related noun phrases from non-outcome phrases [20].

- Outcome Classification: The same SBERT architecture was used for multi-class classification, assigning extracted outcomes to domains in the COMET taxonomy [20].

- Training Regimen: The model was systematically trained with sample sizes from 5 to 85 articles to determine the minimum data required for reliable performance. A hold-out set of 28 articles was used for final testing [20].

AI vs. Human Double Extraction RCT

A rigorous randomized controlled trial (RCT) is underway to directly compare a hybrid AI-human data extraction strategy against traditional human double extraction [17]. This design will provide high-quality evidence on the efficacy of AI integration.

Protocol:

- Design: Randomized, controlled, parallel trial.

- Groups: Participants are assigned to either an AI group (using Claude 3.5 for extraction followed by human verification) or a non-AI group (standard human double extraction) [17].

- Primary Outcome: The percentage of correct extractions for two tasks: event count and group size from RCTs [17].

- Status: The trial is scheduled to run from October 2025 to December 2025, with results expected in 2026 [17].

Analysis of Key Findings

The Specialization Advantage

A consistent theme across studies is the performance gap between general-purpose and specialized AI tools. In a direct comparison using the ECACT framework, the specialized tool ELISE consistently outperformed others in extraction, comprehension, and analysis of scientific literature, making it more suitable for high-stakes applications in regulatory affairs and clinical trials [18]. Conversely, while efficient for data retrieval, general-purpose models like ChatGPT lacked the necessary precision for complex scientific analysis [18]. This underscores that for chemical and biomedical data extraction, domain-specific tuning and context awareness are non-negotiable for achieving high precision and recall.

The Hybrid Human-AI Paradigm

The prevailing evidence does not support a full, unsupervised replacement of human experts. Instead, the most effective and reliable model emerging is one of collaboration between AI and human experts. The ongoing RCT comparing "AI extraction with human verification" to "human double extraction" formalizes this hybrid approach [17]. Similarly, the high accuracy of the FSL-LLM model for mortality information was validated against a human-annotated reference standard [21]. This paradigm leverages AI's speed and scalability while retaining human oversight for validation, complex judgment, and managing ambiguous cases, thereby optimizing the trade-off between efficiency and accuracy.

Persistent Challenges in Chemical Data

The ChemX benchmark highlights that chemical information extraction remains a particularly formidable challenge for automation [19]. Agentic systems, both general and specialized, showed limited performance when dealing with the heterogeneity of chemical data. Key obstacles include processing domain-specific terminology, interpreting complex tabular and schematic representations, and resolving context-dependent ambiguities [19]. This indicates that while AI extraction is mature for more standardized textual data, cutting-edge research continues to push the boundaries of what is automatable in highly specialized scientific domains.

The landscape of data extraction has irrevocably shifted from purely manual curation toward a future powered by artificial intelligence. The experimental data presented in this guide demonstrates that automated AI extraction can achieve remarkably high precision and recall, sometimes rivaling or exceeding individual human extraction, though not yet consistently surpassing the gold standard of human double extraction [17] [20].

The critical insight for researchers and drug development professionals is that tool selection must be task-specific. For standardized outcome extraction from clinical texts, existing ML pipelines are highly effective. For complex chemical data, specialized agents and benchmarks like ChemX are essential, though further development is needed. For high-stakes regulatory and research applications, a hybrid AI-human model currently offers the optimal balance of efficiency and reliability. As AI models continue to evolve and benchmark datasets become more comprehensive, the precision and recall of automated systems will only improve, further solidifying their role in the scientific toolkit.

Next-Gen Extraction Engines: From RxnIM to MERMaid

The integration of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) into chemical image parsing represents a fundamental transformation in data extraction methodologies for pharmaceutical and chemical engineering applications. This comparative guide objectively evaluates the performance of leading MLLMs against traditional approaches, with particular emphasis on precision and recall metrics as critical benchmarks for automated chemical data extraction. By synthesizing experimental data from recent studies, we demonstrate that while MLLMs like GPT-4o and GPT-4V significantly enhance contextual reasoning and data interpretation capabilities, important trade-offs in computational efficiency, specificity, and diversity of outputs must be carefully considered for drug development applications. The analysis provides researchers and scientists with a structured framework for selecting appropriate MLLM architectures based on specific chemical image parsing requirements, highlighting both the transformative potential and current limitations of these technologies in real-world scientific workflows.

The evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) in chemical engineering and pharmaceutical development has progressed from early rule-based systems to sophisticated neural networks capable of processing complex multimodal data [22]. Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) represent the latest advancement in this trajectory, combining capabilities in visual understanding, natural language processing, and domain-specific reasoning to revolutionize how chemical images are parsed and interpreted. These models, including GPT-4V, GPT-4o, and specialized variants, demonstrate unprecedented abilities to extract meaningful information from diverse chemical representations including spectroscopic data, molecular structures, and process flow diagrams [23] [24].

Traditional methods for chemical image analysis have predominantly relied on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and chemometric approaches, which while effective for specific pattern recognition tasks, often lack the contextual reasoning capabilities required for complex scientific interpretation [25] [24]. The emergence of MLLMs addresses this limitation by integrating visual data processing with extensive chemical knowledge encoded during training, enabling more nuanced understanding of chemical structures and relationships [22]. This paradigm shift is particularly significant for drug development professionals who require accurate extraction of complex chemical data to inform critical decisions in compound selection, reaction optimization, and regulatory submissions.

Within this context, precision and recall metrics provide essential frameworks for evaluating the practical utility of MLLMs in chemical image parsing [26] [2]. Precision measures the accuracy of positive identifications, critical for avoiding false leads in drug candidate selection, while recall assesses the completeness of data extraction, ensuring no potentially valuable compounds or relationships are overlooked [27]. This guide systematically compares the performance of leading MLLMs against traditional methods, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological insights to inform the integration of these technologies into their chemical data extraction workflows.

Experimental Methodologies for MLLM Evaluation

Benchmarking Frameworks and Dataset Selection

The evaluation of MLLMs for chemical image parsing employs rigorous benchmarking frameworks designed to assess performance across diverse tasks and chemical domains. Standardized methodologies include the use of curated chemical image datasets with established ground truth annotations to enable quantitative comparison of extraction accuracy [25] [28]. These datasets typically encompass multiple chemical representation formats including:

- Spectral data (IR, NMR, Mass Spectrometry)

- Molecular structures (2D and 3D representations)

- Process flow diagrams and engineering schematics

- Chromatographic results and analytical outputs

In comprehensive benchmarking studies, datasets are meticulously partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets following standard practices for medical and chemical image analysis, typically employing an 80:20 split for training and validation with an additional held-out set for final evaluation [25]. This approach ensures that models are evaluated on unseen data, providing a realistic assessment of their performance in real-world applications.

Performance Metrics and Statistical Analysis

The evaluation of chemical image parsing models employs a comprehensive set of metrics specifically selected to assess different aspects of performance relevant to pharmaceutical and chemical engineering applications:

- Precision: Measures the proportion of correctly identified chemical entities or relationships among all positive predictions, calculated as TP/(TP+FP) [2] [27]

- Recall: Assesses the model's ability to identify all relevant chemical entities or relationships, calculated as TP/(TP+FN) [2] [27]

- F1-Score: Provides the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced assessment of model performance [27]

- Accuracy: Measures the overall correctness of the model across all classifications [27]

- Task-Specific Metrics: Including exact match accuracy for structure elucidation and mean average precision for chemical object detection [28]

Statistical analysis typically involves multiple runs with different random seeds to account for variability, with results reported as mean ± standard deviation to provide both performance estimates and their stability across different initializations [25] [28]. Additionally, computational efficiency metrics including inference time, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions are increasingly included in comprehensive evaluations to address sustainability concerns in large-scale deployment [25].

Table 1: Standard Evaluation Metrics for Chemical Image Parsing

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation in Chemical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | TP/(TP+FP) | Accuracy of compound identification; minimizes false leads |

| Recall | TP/(TP+FN) | Completeness of chemical entity extraction; reduces missed compounds |

| F1-Score | 2×(Precision×Recall)/(Precision+Recall) | Balanced measure of identification performance |

| Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) | Overall correctness across all chemical classes |

| MAE | Σ|Predicted-Actual|/n | Accuracy in quantitative measurements (concentrations, peaks) |

MLLM-Specific Evaluation Protocols

Specialized evaluation protocols have been developed to assess the unique capabilities of MLLMs in chemical image parsing. These include:

- Zero-shot and few-shot learning assessments measuring the model's ability to parse novel chemical structures without task-specific training [22] [28]

- Cross-modal reasoning tests evaluating how effectively models integrate textual context with visual chemical representations [23] [28]

- Compositional understanding tasks assessing the interpretation of complex chemical relationships and processes [28]

- Robustness evaluations measuring performance consistency across different representation styles and image qualities [24] [28]

For proprietary models like GPT-4V and GPT-4o, evaluation typically occurs through API access with carefully designed prompts that incorporate chemical domain knowledge [28]. Open-source models such as LLaVA-NeXT and Phi-3-Vision are evaluated using standardized fine-tuning protocols on chemical datasets to ensure fair comparison [28].

Comparative Performance Analysis

MLLMs vs. Traditional Chemical Image Parsing Methods

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals distinct performance profiles between MLLMs and traditional chemical image parsing approaches. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and chemometric methods demonstrate strong performance in specific, well-defined tasks but struggle with contextual reasoning and cross-modal integration [25] [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Chemical Image Parsing Approaches

| Model Type | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Domain Adaptability | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional CNNs | 94.2% [25] | 92.8% [25] | 93.5% [25] | Low | Medium |

| Chemometric Models | 89.7% [24] | 91.2% [24] | 90.4% [24] | Low | High |

| GPT-4V | 87.3% [28] | 89.1% [28] | 88.2% [28] | High | Medium |

| GPT-4o | 89.5% [28] | 90.3% [28] | 89.9% [28] | High | Medium |

| LLaVA-NeXT | 82.1% [28] | 84.7% [28] | 83.4% [28] | Medium | Medium |

| Phi-3-Vision | 84.6% [28] | 83.9% [28] | 84.2% [28] | Medium | Medium |

The data indicates that while traditional CNNs achieve slightly higher precision and recall on narrow, well-defined tasks, MLLMs offer significantly superior domain adaptability – a critical advantage in chemical research where novel compounds and representations frequently emerge [25] [28]. This adaptability comes with a modest performance trade-off in standardized benchmarks but provides substantial benefits in real-world applications requiring flexibility.

Task-Specific Performance Variations

The relative performance of different models varies significantly across specific chemical image parsing tasks, highlighting the importance of task-model alignment in research applications:

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Chemometric approaches combined with wavelet transforms achieve precision of 91.5% in interpreting IR and NMR spectra, slightly outperforming MLLMs in structured peak identification [24]

- Molecular Structure Elucidation: GPT-4o demonstrates superior performance with 87.7% accuracy in extracting structured information from chemical diagrams, leveraging its advanced reasoning capabilities [22]

- Process Flow Interpretation: MLLMs significantly outperform traditional methods in interpreting chemical engineering schematics, with GPT-4V achieving 85.2% accuracy in equipment identification and process understanding [23] [22]

- Chart and Graph Interpretation: MLLMs show notable advantages in extracting data from chemical research charts, with performance improvements of 15-20% over OCR-based methods [23]

The performance variations across tasks underscore the complementary strengths of different approaches, suggesting that hybrid systems may offer optimal solutions for complex chemical data extraction pipelines.

Precision-Recall Trade-offs in MLLM Applications

A critical consideration in MLLM deployment is the inherent trade-off between precision and recall, which manifests differently across model architectures and significantly impacts their utility in chemical research applications [26] [27].

Diagram 1: Precision-Recall Trade-off in MLLM Chemical Parsing (76 characters)

As illustrated in Diagram 1, MLLMs optimized for high precision employ more conservative prediction strategies, reducing false positives at the cost of potentially missing novel or ambiguous chemical entities [26] [27]. Conversely, models prioritizing recall adopt more inclusive identification approaches, minimizing missed compounds but increasing the risk of false leads that require additional verification [2]. Understanding this balance is crucial for researchers selecting MLLMs for specific applications – early drug discovery may benefit from recall-oriented approaches to avoid missing promising compounds, while late-stage development typically requires high-precision parsing to prevent costly false leads [29].

MLLM Architectures for Chemical Image Parsing

Large-Scale MLLMs: Capabilities and Limitations

Large-scale MLLMs such as GPT-4V and GPT-4o represent the current state-of-the-art in chemical image parsing, offering advanced reasoning capabilities and extensive chemical knowledge [28]. These models demonstrate exceptional performance in:

- Contextual chemical understanding that integrates image content with textual descriptions and domain knowledge [22] [28]

- Few-shot and zero-shot learning that enables adaptation to novel chemical representations without extensive retraining [28]

- Cross-modal reasoning that connects visual chemical representations with textual data, research literature, and experimental results [23] [28]

However, these capabilities come with significant limitations for chemical research applications:

- High computational requirements resulting in slow inference times and substantial operational costs [25] [28]

- Limited domain specificity despite broad knowledge, often requiring additional fine-tuning for specialized chemical subfields [22]

- Privacy concerns when processing proprietary chemical structures through external APIs [29] [28]

- Interpretability challenges in complex scientific decision-making processes [25] [29]

For large-scale deployment in pharmaceutical settings, these limitations necessitate careful consideration of cost-benefit trade-offs and potential hybrid approaches that combine large MLLMs with specialized domain-specific models.

Small-Scale MLLMs: Efficiency and Specialization

The emergence of small-scale MLLMs such as LLaVA-NeXT and Phi-3-Vision offers promising alternatives to their larger counterparts, particularly for specialized chemical applications with efficiency constraints [28]. These models provide:

- Significantly reduced computational requirements enabling faster inference and lower deployment costs [28]

- Enhanced privacy preservation through on-device deployment possibilities [28]

- Improved domain specialization through focused fine-tuning on chemical datasets [22] [28]

Performance evaluations indicate that while small MLLMs achieve comparable results to large models on straightforward chemical image parsing tasks, they lag significantly in complex reasoning scenarios requiring deeper chemical knowledge or sophisticated inference [28]. This performance gap is most pronounced in:

- Complex structure elucidation from ambiguous or incomplete visual representations

- Cross-disciplinary reasoning connecting chemical structures with biological activity or physical properties

- Novel compound interpretation without extensive training examples

For targeted applications with well-defined scope and resource constraints, small MLLMs present a viable alternative to larger models, particularly when combined with domain-specific fine-tuning and optimized deployment strategies.

Domain-Specialized Chemical MLLMs

The development of domain-specialized MLLMs represents a promising direction for chemical image parsing, addressing the limitations of general-purpose models through targeted training on chemical data [22]. Models such as ChemLLM demonstrate that specialization can achieve performance comparable to general-purpose models like GPT-4 within specific chemical domains while offering significantly improved efficiency [22].

Key advantages of domain-specialized MLLMs include:

- Enhanced precision on specialized chemical tasks through focused training [22]

- Improved interpretability through domain-aligned reasoning processes [25] [22]

- Reduced computational requirements compared to general-purpose models of similar capability [22] [28]

- Better integration with existing chemical informatics workflows and data formats [24] [22]

The primary limitation of specialized models is their narrower scope of application, requiring researchers to maintain multiple specialized systems for different chemical subdomains rather than relying on a single general-purpose model [22] [28]. As the field evolves, modular approaches that combine specialized chemical parsing components with general MLLM reasoning capabilities may offer an optimal balance of performance and flexibility.

Experimental Workflow for MLLM Evaluation

The comprehensive evaluation of MLLMs for chemical image parsing follows a systematic workflow that ensures reproducible and comparable results across different models and tasks.

Diagram 2: MLLM Chemical Parsing Evaluation Workflow (65 characters)

As depicted in Diagram 2, the experimental workflow begins with careful data selection encompassing diverse chemical representations and annotation standards [25] [28]. This is followed by comprehensive preprocessing to standardize formats, assess quality, and partition data appropriately for training, validation, and testing [25]. The model processing stage involves careful prompt engineering for proprietary MLLMs or fine-tuning for open-source models, followed by inference execution and output extraction [28]. Evaluation includes metric calculation, statistical testing, and detailed error analysis to identify specific strengths and limitations [25] [27]. The workflow concludes with comparative analysis that assesses performance trade-offs and formulates application-specific recommendations [26] [28].

This standardized approach enables meaningful comparison across different studies and models, providing researchers with reliable guidance for selecting appropriate MLLM solutions for specific chemical image parsing requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The effective implementation of MLLMs for chemical image parsing requires both computational resources and domain-specific materials. The following table details key components of the experimental toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MLLM Chemical Image Parsing

| Toolkit Component | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Image Datasets | Model training and evaluation | COVID-19 Radiography Database [25], Brain Tumor MRI Dataset [25], Beer Spectroscopy Dataset [24] |

| Annotation Platforms | Ground truth establishment | Labeled chemical structures, spectral peak annotations, process diagram markup |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | Performance assessment | Custom evaluation scripts, precision-recall calculators, statistical testing packages |

| MLLM Access Tools | Model integration and deployment | OpenAI API [28], HuggingFace Transformers [28], Custom fine-tuning code |

| Computational Resources | Model execution and training | High-performance GPUs, Cloud computing credits, Specialized AI accelerators |

| Domain-Specific Models | Specialized chemical parsing | ChemLLM [22], Fine-tuned LLaVA [28], Custom CNN architectures [25] |

| Visualization Tools | Result interpretation and presentation | Chemical structure renderers, Spectral plot generators, Confidence score visualizers |

Each component plays a critical role in the end-to-end development and deployment of MLLM solutions for chemical image parsing. The selection of appropriate datasets and annotation approaches fundamentally influences model performance, while benchmarking frameworks ensure objective comparison across different approaches [25] [28]. Computational resources determine the scale and speed of experimentation, with specialized infrastructure often required for large-model fine-tuning and evaluation [25]. The growing availability of domain-specific models provides researchers with targeted solutions that reduce the need for extensive customization, while visualization tools bridge the gap between model outputs and scientific interpretation [22].

The integration of Multimodal Large Language Models into chemical image parsing represents a significant advancement in pharmaceutical and chemical engineering research, offering unprecedented capabilities in contextual understanding and cross-modal reasoning. Performance analysis reveals a complex landscape where large-scale MLLMs like GPT-4o and GPT-4V excel in complex reasoning tasks, while specialized smaller models provide efficient solutions for targeted applications with resource constraints.

The critical evaluation using precision and recall metrics demonstrates that model selection must be guided by specific research objectives, with distinct trade-offs between identification accuracy and comprehensive coverage [26] [2] [27]. For drug development professionals, this means aligning model capabilities with specific stages of the research pipeline – prioritizing recall in early discovery to avoid missing promising compounds, and emphasizing precision in late-stage development to prevent costly false leads [29].

Future developments in MLLMs for chemical applications will likely focus on enhanced specialization through continued training on chemical data, improved efficiency to address computational barriers, and better integration with existing research workflows [22] [28]. As these models evolve, they will increasingly serve as collaborative partners in chemical research, assisting scientists in pattern recognition, hypothesis generation, and experimental design while maintaining the critical role of human expertise in scientific validation and interpretation.

The paradigm shift toward MLLM-enabled chemical image parsing promises to accelerate discovery and innovation across pharmaceutical and chemical domains, but its successful implementation requires careful consideration of performance characteristics, application requirements, and the essential balance between automated extraction and scientific judgment.

The advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) in organic chemistry is fundamentally constrained by the availability of high-quality, machine-readable chemical reaction data [30] [31]. Despite the wealth of knowledge documented in scientific literature, most published reactions remain locked in unstructured image formats within PDF documents, making them inaccessible for computational analysis and machine learning applications [32]. The field of automated chemical data extraction thus heavily relies on precision and recall metrics to evaluate how effectively systems can transform this unstructured information into structured, actionable data. This case study examines RxnIM (Reaction Image Multimodal large language model), a pioneering model that has achieved a notable 88% F1 score in reaction component identification, representing a significant leap forward in addressing this critical data extraction challenge [30] [31].

RxnIM is the first multimodal large language model (MLLM) specifically engineered to parse chemical reaction images into machine-readable reaction data [30]. Unlike previous approaches that treated chemical reaction parsing as separate computer vision and natural language processing tasks, RxnIM employs an integrated architecture that simultaneously interprets both graphical elements and textual information within reaction diagrams [31].

The model's innovation lies in its unified framework that addresses two complementary sub-tasks:

- Reaction Component Identification: Locating and classifying all graphical components (reactants, reagents, products) within a reaction image and understanding their roles [30] [31].

- Reaction Condition Interpretation: Extracting and contextualizing textual information describing reaction conditions, including agents, solvents, temperature, time, and yield [30].

This dual-capability approach enables RxnIM to produce comprehensive structured outputs that capture both the structural transformation and experimental context of chemical reactions, addressing a critical limitation of earlier methods that relied on external optical character recognition (OCR) tools without further semantic processing [30].

Experimental Design and Methodology

Dataset Creation and Training Strategy

A cornerstone of RxnIM's development was the creation of a large-scale, synthetic dataset for training [30] [31]. The researchers developed a novel data generation algorithm that extracted textual reaction information from the Pistachio dataset—a comprehensive chemical reaction database primarily derived from patent text—and transformed it into visual reaction components following conventions in chemical literature [30].

RxnIM Synthetic Data Generation Pipeline: The workflow transforms structured reaction data into diverse training images [30].

The synthetic generation process followed established conventions for representing chemical reactions: drawing molecular structures for reactants and products, connecting them with reaction arrows, positioning reagent information above arrows, and placing solvent, temperature, time, and yield data below arrows [30]. To enhance robustness, the team incorporated data augmentation varying font sizes, line widths, molecular image dimensions, and reaction patterns (single-line, multiple-line, branch, and cycle structures) [30] [31]. This methodology generated 60,200 synthetic images with comprehensive ground truth annotations, which were divided into training, validation, and test sets using an 8:1:1 ratio [31].

Model Architecture and Training Protocol

RxnIM employs a sophisticated multimodal architecture consisting of four key components [30]:

- A unified task instruction framework that standardizes chemical reaction image parsing tasks

- A multimodal encoder that aligns visual information with text-based instructions

- A ReactionImg tokenizer that converts image features into tokens compatible with language models

- An open-ended LLM decoder that generates the final parsing output

The training process employed a strategic three-stage approach [30] [31]:

- Stage 1: Pretraining the model's object detection capability on the large-scale synthetic dataset

- Stage 2: Training the model to identify reaction components and extract conditions using the synthetic dataset

- Stage 3: Fine-tuning on a smaller, manually curated dataset of real reaction images to enhance performance on authentic literature examples

This progressive training strategy enabled the model to first learn fundamental visual detection skills before advancing to more complex interpretation tasks, ultimately refining its capabilities on real-world data distributions [31].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Reaction Component Identification Results

RxnIM's performance was rigorously evaluated against established benchmarks and competing methodologies using both "hard match" and "soft match" evaluation protocols [31]. The hard match criterion requires exact correspondence between predictions and ground truth, while the soft match allows more flexible role assignments (e.g., labeling a reagent as a reactant) [31].

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Reaction Component Identification (F1 Scores)

| Dataset | Model | Hard Match F1 (%) | Soft Match F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic | ReactionDataExtractor | 7.6 | 15.2 |

| OChemR | 7.3 | 16.4 | |

| RxnScribe | 70.9 | 77.3 | |

| RxnIM | 76.1 | 83.6 | |

| Real | RxnScribe | 68.6 | 75.4 |

| RxnIM | 73.8 | 80.8 |

RxnIM demonstrated superior performance across both synthetic and real-image test sets, achieving an average F1 score of 88% (soft match) across various benchmarks, surpassing state-of-the-art methods by an average of 5% [30] [31]. This performance advantage was consistent across both precision and recall metrics, indicating improved accuracy in identification and reduced omission of relevant components.

Comparison with Alternative Approaches

The chemical data extraction landscape features several distinct methodological approaches, each with relative strengths and limitations:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Chemical Data Extraction Tools

| Tool | Approach | Primary Function | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RxnIM | Multimodal LLM | Reaction image parsing | Integrated component identification & condition interpretation | Complex training pipeline |

| RxnScribe | Single encoder-decoder | Reaction diagram parsing | Direct image-to-sequence translation | Struggles with complex reactions [30] [31] |

| MARCUS | Ensemble OCSR + LLM | Natural product curation | Multi-engine OCSR, human-in-the-loop refinement | Specialized for natural products [32] |

| SubGrapher | Visual fingerprinting | Molecular similarity search | Direct image to fingerprint conversion | Limited to substructure detection [33] |

| RxnCaption | Visual prompt captioning | Reaction diagram parsing | BIVP strategy, natural language description | Newer approach, less established [34] |

RxnIM differentiates itself through its comprehensive multimodal understanding, whereas tools like MARCUS focus primarily on molecular structure extraction from natural product literature [32], and SubGrapher employs a novel visual fingerprinting approach that bypasses molecular graph reconstruction entirely [33].

A particularly relevant comparison can be made with RxnCaption, a contemporaneous approach that reformulates reaction diagram parsing as a visual prompt-guided captioning task [34]. While RxnIM uses a "Bbox and Role in One Step" (BROS) strategy, RxnCaption introduces a "BBox and Index as Visual Prompt" (BIVP) approach that pre-annotates molecular bounding boxes, converting the parsing task into natural language description [34]. This alternative strategy addresses limitations of coordinate prediction in large vision-language models and has demonstrated strong performance, particularly with Gemini-2.5-Pro achieving 81.0% F1 score using the BIVP method [34].

Technical Implementation and Workflow