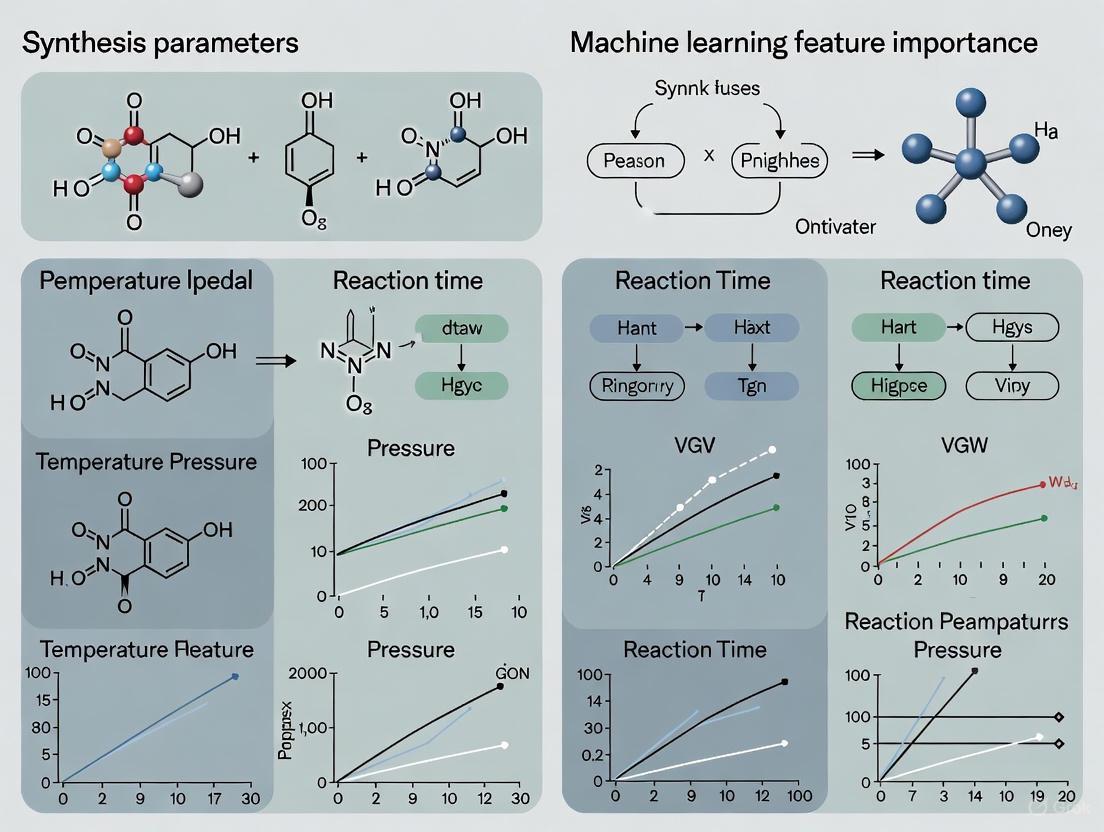

Beyond the Black Box: Using Machine Learning Feature Importance to Decode and Optimize Synthesis Parameters in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying machine learning (ML) feature importance techniques to explore and optimize chemical synthesis parameters.

Beyond the Black Box: Using Machine Learning Feature Importance to Decode and Optimize Synthesis Parameters in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying machine learning (ML) feature importance techniques to explore and optimize chemical synthesis parameters. It covers foundational concepts, detailing how ML accelerates the identification of critical process variables influencing yield, impurity control, and reaction selectivity. The content explores methodological applications, including real-world case studies in process chemistry and analytical method development. It also addresses practical challenges in model optimization and data quality, and provides a framework for validating and comparing different feature importance methods. By synthesizing insights from regulatory, academic, and industry perspectives, this article serves as a strategic resource for leveraging ML to build more efficient, interpretable, and predictive models in pharmaceutical development.

The Foundation: How Feature Importance Reveals Critical Synthesis Parameters

Machine learning (ML) has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, providing powerful capabilities for predicting molecular properties and identifying active compounds. Among the various ML techniques, feature importance analysis stands out as a critical methodology for interpreting model predictions and gaining biological insights. This technical guide explores the fundamental concepts, methodologies, and applications of feature importance in pharmaceutical research, with particular emphasis on its role in understanding synthesis parameters and compound optimization. We present a comprehensive framework for implementing feature importance correlation analysis, experimental protocols for practical application, and visualization techniques that enable researchers to extract meaningful patterns from complex biological data.

Core Concepts and Methodologies

Defining Feature Importance in ML

Feature importance refers to a set of computational techniques that quantify the contribution of individual input variables (features) to the predictive performance of machine learning models. In drug discovery, these features typically represent molecular descriptors, structural fingerprints, or physicochemical properties that influence biological activity. The Gini importance metric, derived from random forest algorithms, serves as a widely-adopted measure that calculates the normalized total reduction in impurity (such as Gini impurity) brought by each feature across all decision trees in the ensemble [1]. Alternative methods include permutation importance, SHAP values, and sensitivity analysis, each offering distinct advantages for different data types and research questions.

Feature importance analysis provides a computational signature of dataset properties that captures underlying biological relationships without requiring explicit model interpretation. This approach differs fundamentally from explainable AI techniques, as it focuses on model-internal information rather than post-hoc explanations of predictions. When applied to compound activity prediction models, feature importance distributions can reveal similar binding characteristics across different target proteins and detect functional relationships that extend beyond shared active compounds [1].

Technical Implementation Framework

The standard implementation pipeline for feature importance analysis in drug discovery comprises several critical stages. Initially, researchers must select appropriate molecular representations, with topological fingerprints serving as a common choice due to their generality and absence of built-in target-specific biases. These binary feature vectors typically employ a constant length of 1024 bits, with each bit representing a specific topological feature derived from molecular structure [1].

For classification tasks, the random forest (RF) algorithm offers a robust foundation for feature importance analysis due to its stability, transparency, and reliable performance with high-dimensional chemical data. The algorithm recursively partitions feature spaces, with Gini impurity calculations at decision nodes quantifying how effectively each feature separates active from inactive compounds. The resulting importance values represent the mean decrease in Gini impurity across all nodes where specific features determine splits, thereby providing a robust metric of feature relevance [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Feature Importance-Based Models in Drug Discovery

| Performance Measure | Minimum Threshold | Typical Performance Range | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Recall | ≥65% | 70-95% | Active compound identification |

| Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | ≥0.5 | 0.6-0.9 | Balanced model accuracy assessment |

| Balanced Accuracy (BA) | ≥70% | 75-95% | Classification performance with imbalanced data |

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Not applicable | 0.11-0.95 (median 0.11) | Feature importance correlation between models |

| Spearman Correlation Coefficient | Not applicable | 0.43-0.95 (median 0.43) | Rank-based feature importance correlation |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Revealing Protein Functional Relationships

Feature importance correlation analysis enables the detection of functional relationships between pharmaceutically relevant targets through computational signatures derived from compound activity prediction models. This approach identified significant associations among 218 target proteins based on their feature importance rankings, with correlation coefficients calculated using both Pearson (linear relationship) and Spearman (rank-based) methods [1]. The resulting correlation matrix, comprising 47,524 pairwise comparisons, revealed distinct clustering patterns along the diagonal when visualized through heatmaps, indicating groups of proteins with similar binding characteristics.

Unexpectedly, this analysis demonstrated that feature importance correlation can detect functional relationships independent of shared active compounds. By integrating Gene Ontology (GO) term annotations and calculating Tanimoto coefficients to quantify functional similarity, researchers established that proteins with correlated feature importance profiles often participate in similar biological processes or molecular functions, even without chemical similarity among their ligands [1]. This finding substantially expands the utility of feature importance analysis beyond conventional chemical similarity assessment.

Binding Characteristics Similarity Assessment

The correlation of feature importance distributions between target-specific ML models provides a robust indicator of similar compound binding characteristics. Research has established a clear relationship between the number of shared active compounds and feature importance correlation strength, with protein pairs sharing increasing numbers of active compounds demonstrating progressively stronger correlation coefficients [1]. This relationship enables researchers to identify targets with similar binding sites or ligand recognition patterns without prior structural knowledge.

In large-scale analyses, hierarchical clustering of proteins based on feature importance correlation has successfully grouped targets from the same enzyme or receptor families, particularly enriching clusters with G protein-coupled receptors [1]. These groupings consistently aligned with established pharmacological target classifications while revealing novel relationships that transcend conventional taxonomic boundaries. The methodology therefore serves as an efficient approach for target family characterization and polypharmacology prediction.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Large-Scale Feature Importance Correlation Analysis

The comprehensive analysis of feature importance correlations across multiple targets requires systematic experimental design and rigorous validation protocols. The following methodology outlines the standardized approach for large-scale investigation:

Data Collection and Curation

- Select a minimum of 60 confirmed active compounds from diverse chemical series for each target protein

- Apply stringent activity data confidence criteria, prioritizing high-quality quantitative measurements

- Curate negative instances using consistently applied random samples of compounds without biological annotations

- Employ unified molecular representation schemes, typically 1024-bit topological fingerprints

Model Development and Validation

- Implement random forest classifiers with consistent hyperparameters across all targets

- Apply minimum performance thresholds: 65% compound recall, MCC of 0.5, and balanced accuracy of 70%

- Calculate feature importance using Gini impurity decrease with normalization across the tree ensemble

- Perform k-fold cross-validation with stratified sampling to ensure robustness

Correlation Computation and Analysis

- Compute pairwise Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients for all target combinations

- Perform hierarchical clustering to identify groups of proteins with similar feature importance profiles

- Integrate external biological annotations (Gene Ontology terms) for functional validation

- Apply statistical significance testing with multiple comparison corrections

Table 2: Experimental Requirements for Feature Importance Correlation Analysis

| Component | Specification | Rationale | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Compounds | ≥60 per target, diverse chemical series | Ensures robust model training | High-confidence activity data |

| Molecular Representation | 1024-bit topological fingerprint | Generalizable, target-agnostic features | Consistent fingerprint generation |

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Random Forest with Gini impurity | Transparent, reproducible importance values | Minimum performance thresholds |

| Negative Instances | Random compounds without bioactivity | Consistent reference state | Uniform sampling procedure |

| Correlation Metrics | Pearson and Spearman coefficients | Captures linear and rank relationships | Statistical significance testing |

Synthesis Parameter Optimization Protocol

Beyond direct compound activity prediction, feature importance methods find application in optimizing material synthesis parameters, as demonstrated in photocatalytic hydrogen production research [2]. This approach provides a template for similar applications in pharmaceutical development, particularly for nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems:

Database Construction

- Systematically vary synthesis parameters including precursor type, temperature (450-600°C), time, and heating rates

- Characterize resulting materials through physicochemical analyses (XRD, nitrogen adsorption)

- Measure performance metrics (e.g., hydrogen evolution rate) under standardized conditions

- Compile comprehensive datasets linking synthesis parameters to material properties and performance

Machine Learning Implementation

- Train multiple ML algorithms (random forest, gradient boosting, neural networks) with hyperparameter optimization

- Assess feature importance to identify critical synthesis parameters influencing performance

- Validate model accuracy through cross-validation, targeting R² values above 0.9

- Develop web applications for model deployment and continuous database expansion

This methodology successfully identified critical synthesis parameters for graphitic carbon nitride materials, with ML models achieving high predictive accuracy (R² > 0.9) for photocatalytic hydrogen production [2]. The same principles apply directly to pharmaceutical development, particularly for optimizing drug formulation parameters and nanocarrier synthesis.

Visualization and Interpretation

Data Visualization Strategies

Effective visualization of feature importance results requires specialized approaches that accommodate the high-dimensional nature of pharmaceutical data. Heatmaps serve as particularly valuable tools for representing correlation matrices, with hierarchical clustering revealing natural groupings among targets [1]. These visualizations enable rapid identification of protein families with similar binding characteristics and outlier targets with unique feature importance profiles.

For representing quantitative data distributions across multiple targets, bar graphs and histograms provide intuitive displays of feature importance magnitudes and correlations [3]. When presenting continuous data, such as correlation coefficients or importance values, histograms with appropriate binning strategies (e.g., 0-5, 5-10) effectively communicate distribution patterns that might be obscured in raw data tables.

Advanced visualization techniques incorporate conditional formatting within data tables to highlight significant correlations or important features, creating hybrid representations that combine precise numerical data with visual emphasis [4]. The addition of spark lines within tables provides quick graphical summaries of feature importance distributions across multiple experiments or conditions.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Feature Importance Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Model development and feature importance calculation | General ML implementation |

| Molecular Representations | Topological fingerprints, Molecular descriptors | Standardized compound featurization | Chemical data preprocessing |

| Validation Metrics | MCC, Balanced Accuracy, Recall | Model performance assessment | Quality control |

| Correlation Analysis | Pearson, Spearman coefficients | Quantifying feature importance similarity | Relationship detection between targets |

| Visualization Tools | Matplotlib, Seaborn, Plotly | Heatmaps, bar graphs, distribution plots | Results communication and interpretation |

| Data Curation | ChEMBL, PubChem, GOSTAR | High-quality bioactivity data | Model training and validation |

Integration with Broader Research Objectives

The application of feature importance analysis extends beyond individual compound-target interactions to inform broader drug discovery paradigms. By detecting functional relationships between proteins that are independent of active compounds, this methodology provides a target-agnostic perspective on pharmacological space that complements traditional structure-based approaches [1]. This capability proves particularly valuable for target identification and validation campaigns, where understanding functional relationships can prioritize novel targets based on their similarity to established targets with known drugability.

Furthermore, the principles of feature importance analysis directly translate to the optimization of synthesis parameters in pharmaceutical development [2]. Just as material scientists employ these techniques to identify critical factors influencing photocatalytic performance, pharmaceutical researchers can apply similar methodologies to optimize drug formulation parameters, nanoparticle synthesis conditions, and manufacturing processes. The integration of feature importance with experimental design creates a powerful framework for data-driven decision making across the drug development pipeline.

In the high-stakes field of machine learning (ML) applications, particularly in drug discovery and development, understanding why a model makes a specific prediction is not merely an academic exercise—it is a practical necessity. The ability to interpret model decisions directly impacts patient safety, regulatory compliance, and scientific discovery. Feature importance stands as a cornerstone of interpretable ML, providing crucial insights into which input variables most significantly influence a model's predictions [5]. As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly integrated into pharmaceutical research—from target identification to clinical trial optimization—the role of feature importance in validating and trusting these complex systems has never been more critical [6] [7].

The need for interpretability arises from what researchers describe as an "incompleteness in problem formalization" [5]. While a model might achieve high predictive accuracy, this single metric often fails to capture all requirements of real-world tasks, especially in domains where decisions affect human health and well-being. Feature importance techniques address this gap by enabling researchers to validate model reasoning, detect potential biases, ensure robustness, and ultimately facilitate the integration of ML insights into scientific decision-making processes [5]. This technical guide explores the core concepts of feature importance and its indispensable role within interpretable machine learning, with special emphasis on applications relevant to drug development professionals and computational researchers.

Fundamental Principles of Feature Importance

Definition and Core Concept

Feature importance refers to a family of techniques designed to quantify the contribution of individual input features (variables) to the predictive performance of a machine learning model. In essence, these methods answer a fundamental question: "Which features does my model consider most relevant when making predictions?" The concept is straightforward in principle—a feature is deemed "important" if modifying or removing its information significantly degrades model performance, and "unimportant" if such changes have negligible effect on predictive accuracy [8] [9].

The importance of a feature is not an intrinsic property of the data itself but rather a measure of its utility within the context of a specific model trained on specific data. This distinction is crucial for proper interpretation, as different models may leverage features in varying ways depending on their architectural biases and training objectives.

The Critical Role of Interpretability

Interpretability serves multiple essential functions in ML systems, particularly in scientific domains like pharmaceutical research:

Scientific Knowledge Discovery: When ML models are applied to research problems, the scientific insights remain hidden if the model only provides predictions without explanations. Feature importance techniques help extract the additional knowledge captured by the model during training, transforming black-box predictors into sources of actionable scientific insight [5].

Model Debugging and Bias Detection: By revealing which features drive model predictions, importance measures enable researchers to identify when models have learned spurious correlations or unintended biases. For instance, a model might incorrectly use snow as a feature for classifying wolves versus huskies, or might inadvertently discriminate against underrepresented groups in loan application data [5].

Safety and Robustness Assurance: In critical applications like drug safety prediction, researchers need high confidence that models have learned appropriate feature relationships. Interpretability helps verify that a model's decision boundaries align with domain knowledge and are robust to realistic variations in input data [5].

Regulatory Compliance and Social Acceptance: As regulatory agencies like the FDA increasingly encounter AI/ML components in drug applications, demonstrating a clear understanding of model behavior becomes essential for compliance [10]. Furthermore, explanations enhance social acceptance of algorithmic decisions by creating shared understanding between systems and their users [5].

Key Feature Importance Methods

Permutation Feature Importance

Theoretical Foundation

Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) measures the increase in a model's prediction error after randomly shuffling the values of a single feature, thereby breaking the relationship between that feature and the true outcome [8]. This approach, initially introduced by Breiman for random forests and later formalized into a model-agnostic version by Fisher et al., provides an intuitive methodology for assessing feature relevance [8] [9].

The algorithm operates as follows:

- Estimate the original model error ((e_{orig})) using an appropriate loss function

- For each feature (j):

- Create a modified dataset by permuting the values of feature (j) across all instances

- Estimate the new error ((e_{perm,j})) using the permuted data

- Calculate importance as: (FIj = e{perm,j} - e{orig}) (difference) or (FIj = e{perm,j}/e{orig}) (ratio)

- Sort features by descending importance value [8]

The permutation approach effectively captures both the main effect of a feature and its interaction effects with other features, since shuffling disrupts all relationships involving that feature [8].

Implementation Considerations

Several practical considerations impact the application and interpretation of PFI:

Use of Unseen Data: PFI should be estimated on data not used for model training to avoid overly optimistic results, particularly with overfitting models. Computing PFI on training data can falsely highlight irrelevant features as important due to the model's over-reliance on noise during training [8].

Metric Selection: The choice of error metric ((L)) should align with the problem context. For classification, metrics like accuracy, AUC, or log loss may be appropriate, while regression might use mean squared error or mean absolute error. When using performance metrics where higher values are better (e.g., accuracy), the importance calculation should be adjusted accordingly [8].

Handling Correlated Features: A significant limitation of standard PFI emerges when features are correlated. Permuting a single feature creates unrealistic data instances when correlations exist, potentially leading to biased importance estimates [8] [9]. For example, shuffling a patient's weight while keeping height unchanged could create physically impossible combinations, and the model's poor performance on these implausible instances might overstate the importance of the permuted feature.

Table 1: Comparison of Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) Variants

| Method Type | Sampling Approach | Interpretation | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal PFI | Permute feature across entire dataset (sample from marginal distribution) | Importance of feature information including correlations | General use with independent features |

| Conditional PFI | Permute feature within subgroups or sample from conditional distribution | Importance of unique feature information not encoded elsewhere | Data with strongly correlated features |

| Group-wise PFI | Permute within data subgroups (e.g., by species or clusters) | Importance within data partitions while reducing correlation effects | Data with natural clustering or categorical variables |

Workflow Visualization

Model-Specific Importance Measures

Coefficient-Based Importance

For linear models—including linear regression, logistic regression, and linear SVMs—feature importance can be derived directly from model coefficients. The weight assigned to each feature during training indicates its direction and magnitude of influence on the output [11]. For proper comparison across features, data should be standardized prior to modeling, as coefficient magnitudes are influenced by feature scales.

Tree-Based Importance

Tree ensemble methods (random forests, gradient boosting machines) naturally provide feature importance measures through algorithms like Mean Decrease in Impurity [11]. For random forests, this typically involves calculating the total reduction in Gini impurity or entropy attributable to splits on each feature, averaged across all trees in the forest [1]. While computationally efficient and native to these models, these measures can be biased toward features with more possible split points and may not fully capture feature importance for prediction accuracy.

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)

SHAP provides a unified approach to feature importance based on cooperative game theory, specifically Shapley values [11]. Unlike permutation importance, which measures importance through performance degradation, SHAP quantifies the contribution of each feature to the difference between a specific prediction and the average prediction [11]. SHAP feature importance is typically calculated as the mean absolute Shapley value for each feature across all instances, providing a global importance measure [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Importance Measurement Approaches

| Method | Model Compatibility | Theoretical Basis | Implementation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permutation Importance | Model-agnostic | Performance degradation from feature destruction | Straightforward, no retraining needed | Biased with correlated features, computationally intensive |

| Coefficient-Based | Linear models only | Coefficient magnitude in linear models | Direct from model parameters | Limited to linear models, requires standardization |

| Tree Importance | Tree-based models only | Impurity reduction (Gini/entropy) | Direct from model structure | Biased toward high-cardinality features, model-specific |

| SHAP | Model-agnostic | Shapley values from game theory | More complex computation | Computationally expensive, complex interpretation |

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Revealing Protein Functional Relationships

Feature importance analysis has demonstrated innovative applications beyond model interpretation in drug discovery. Recent research has introduced feature importance correlation analysis, which compares importance distributions across multiple models to uncover hidden relationships between biological targets [1].

In a proof-of-concept study analyzing 218 target proteins, researchers trained random forest classifiers to distinguish between active and inactive compounds for each protein. By calculating the correlation between feature importance rankings across protein pairs, they discovered that strongly correlated importance profiles indicated either similar compound binding characteristics or functional relationships between proteins, independently of shared active compounds [1]. This approach represents a novel application of feature importance as a model-internal computational signature of dataset properties.

AI-Enhanced Drug Development Workflow

Artificial intelligence, powered by interpretable ML approaches, is revolutionizing multiple stages of the drug development pipeline. From target identification and validation to clinical trial optimization, feature importance methods provide crucial insights that enhance both efficiency and success rates [6] [7].

Table 3: Applications of Feature Importance in Drug Development

| Development Stage | ML Application | Role of Feature Importance | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Molecular modeling & protein structure prediction | Identify critical structural features influencing binding | Shortens target discovery from years to months [6] |

| Compound Screening | Virtual screening of chemical libraries | Pinpoint molecular descriptors associated with activity | Reduces reliance on physical HTS; identifies novel candidates [6] |

| Preclinical Testing | Toxicity and efficacy prediction | Surface structural alerts associated with adverse effects | Enables earlier safety filtering; reduces animal testing [6] |

| Clinical Trials | Patient stratification and outcome prediction | Identify biomarkers and patient characteristics linked to response | Improves trial success rates; enables precision medicine [6] |

Drug Discovery Workflow Visualization

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Large-Scale Feature Importance Correlation Analysis

The following protocol outlines the methodology for conducting feature importance correlation analysis to detect functional relationships between proteins, as demonstrated in recent research [1]:

Data Preparation and Model Training

- Protein Target Selection: Curate a set of target proteins with sufficient active compounds (e.g., ≥60 confirmed actives from diverse chemical series)

- Compound Curation: For each target, compile active compounds with high-confidence activity data and select inactive compounds from commercially available compounds without biological annotations

- Molecular Representation: Encode all compounds using consistent molecular representation (e.g., 1024-bit topological fingerprints)

- Model Training: Train random forest classifiers for each target to distinguish active from inactive compounds, ensuring minimum performance thresholds (e.g., recall ≥65%, MCC ≥0.5, balanced accuracy ≥70%)

Feature Importance Calculation

- Gini Importance Extraction: For each RF model, calculate Gini importance for all features

- Feature Ranking: Rank features by their importance values for each target-specific model

- Importance Correlation: Compute pairwise correlation coefficients (Pearson and Spearman) between feature importance rankings for all protein pairs

- Statistical Analysis: Identify protein pairs with significantly high feature importance correlation

Biological Validation

- Shared Ligand Analysis: Determine numbers of common active compounds between protein pairs

- Functional Annotation: Extract Gene Ontology terms for all proteins and calculate term overlap using Tanimoto similarity

- Relationship Verification: Assess whether high feature importance correlation aligns with either shared ligands or functional similarities

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Feature Importance Analysis in Drug Discovery

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representations | Topological fingerprints, Molecular descriptors, Graph embeddings | Encode chemical structure as machine-readable features | Convert chemical structures into consistent feature vectors for model training [1] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Linear Models, Neural Networks | Build predictive models linking features to biological activity | Create classification/regression models for compound activity prediction [1] |

| Feature Importance Libraries | SHAP, ELI5, scikit-learn permutation importance, model-specific importance | Calculate and visualize feature importance metrics | Quantify and interpret feature contributions to model predictions [11] |

| Model Evaluation Metrics | AUC, Balanced Accuracy, Matthews Correlation Coefficient, Precision-Recall | Assess model performance and generalization capability | Validate model quality before feature importance analysis [1] |

| Correlation Analysis Tools | Pearson correlation, Spearman rank correlation, Hierarchical clustering | Identify relationships between feature importance profiles | Detect similar binding characteristics or functional relationships [1] |

Future Directions and Challenges

As artificial intelligence continues to transform drug discovery and development, several challenges and emerging trends will shape the future of feature importance in interpretable ML:

Addressing Feature Correlations: Current research is developing more sophisticated approaches to handle correlated features, including conditional permutation importance that samples from conditional distributions rather than marginal distributions [8]. These methods aim to provide more accurate importance estimates for real-world datasets where features are rarely independent.

Standardization and Regulatory Frameworks: With the FDA noting a significant increase in drug applications containing AI/ML components, regulatory frameworks for evaluating feature importance and model interpretability are evolving [10]. The establishment of the CDER AI Council in 2024 reflects the growing importance of standardized approaches to AI validation in pharmaceutical applications [10].

Fusion Approaches for Enhanced Reliability: Research into fuzzy information fusion methods for combining feature importance results from multiple models and data subsets shows promise for improving the reliability of explanations [12]. These approaches address the current lack of consensus in how feature importance should be quantified, making model explanations more dependable for critical decision-making.

Integration with Causal Inference: Future methodologies may increasingly combine feature importance with causal inference techniques to distinguish between mere correlations and causally relevant features, particularly important for understanding biological mechanisms and intervention points [5].

As these developments unfold, feature importance will remain an essential component of trustworthy ML systems in drug discovery and beyond, enabling researchers to extract meaningful insights from complex models while maintaining scientific rigor and regulatory compliance.

The pharmaceutical industry faces a persistent and critical challenge: the overwhelming cost and time required to bring new therapeutics to market. Traditional drug development is characterized by labor-intensive methods, lengthy timelines, and high failure rates, creating a pressing business need for transformative efficiency gains [6]. Research indicates that the traditional process of developing new drugs costs approximately $4 billion and takes more than 10 years to complete [6]. Furthermore, the overall success rate for drug development—from phase I clinical trials to regulatory approval—stands at a mere 6.2%, underscoring the immense financial risk and operational inefficiency inherent in conventional approaches [13].

This economic reality creates a compelling business case for adopting advanced computational strategies that can streamline development pipelines. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are emerging as pivotal technologies capable of reversing this trend by introducing data-driven precision and predictive power across the drug development lifecycle [6] [14]. By leveraging these technologies, particularly through the lens of feature importance analysis, researchers can move from a paradigm of costly trial-and-error to one of targeted, efficient experimentation, ultimately reducing attrition rates and accelerating the delivery of novel treatments to patients [13].

The Business Case: Quantifying the Efficiency Gap

The pursuit of efficiency is not merely an operational improvement but a strategic necessity for economic viability and therapeutic advancement. The following table summarizes the key quantitative challenges and the potential impact of AI-driven solutions.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Challenges in Traditional Drug Development and AI Impact Potential

| Challenge Dimension | Traditional Process Metric | AI/ML Impact Potential | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Cost | ~$4 billion per new drug | Potential for significant cost reduction | [6] |

| Development Timeline | >10 years | Can cut time to preclinical candidates by up to 40% | [6] [14] |

| Overall Success Rate | 6.2% (Phase I to approval) | Aims to raise odds of success from historical ~10% | [13] [14] |

| Discovery Phase Efficiency | Multi-year process for novel compound design | Reduced to months (e.g., 30 months to Phase I) | [14] |

| R&D Productivity | Declining efficiency, straining budgets | Expected to power 30% of new drug discoveries by 2025 | [14] |

Beyond these quantitative metrics, the "efficiency gap" manifests in operational bottlenecks across the entire development value chain. These include the identification of viable drug targets, the design and optimization of lead compounds, the prediction of toxicity and efficacy, and the design of efficient clinical trials [6] [13]. The industry's reliance on high-throughput screening and trial-and-error research represents a significant resource drain, both in terms of time and capital [6]. AI technologies, capable of analyzing vast and complex datasets far beyond human capacity, offer a pathway to overcome these hurdles by providing enhanced predictive capabilities and enabling more informed decision-making at every stage [6] [15].

Machine Learning and Feature Importance: A Technical Pathway to Efficiency

Machine learning provides a sophisticated toolbox for addressing the core inefficiencies in drug development. At its core, ML uses algorithms to parse data, learn from it, and make determinations or predictions, rather than relying on pre-programmed instructions [13]. This capability is particularly well-suited to the high-dimensionality data—including genomic, chemical, and clinical information—that is now routinely generated in pharmaceutical R&D [13] [15].

The Role of Feature Importance Analysis

Within the ML landscape, feature importance analysis is a critical methodology for enhancing R&D productivity. It moves beyond simple prediction to provide insights into which factors are most influential in determining a given outcome. In the context of drug development, this translates to identifying the molecular descriptors, process parameters, or biological features that most significantly impact a desired property, such as binding affinity, solubility, potency, or synthetic yield [16] [1].

This approach transforms ML from a "black box" into a strategic guide for resource allocation. For example, in process chemistry, ML models including random forest models can analyze data sets to screen multiple process parameters simultaneously, revealing the most influential variables for controlling reaction yields, impurity levels, and selectivity [16]. This allows development teams to focus their experimental efforts on the factors that matter most, drastically reducing the number of experiments required to establish a robust and scalable synthetic route [16].

Furthermore, feature importance correlation analysis can uncover complex, non-obvious relationships. In one case study, while a traditional Design of Experiment (DoE) analysis failed to flag agitation as an important process variable, an ML algorithm successfully identified it by uncovering conflating variables [16]. This demonstrates how ML can provide enhanced insights that traditional methods may miss, leading to more profound process understanding and control.

Technical Protocols for Feature Importance Analysis

The following section provides a detailed methodology for implementing feature importance analysis in a drug discovery context, drawing from peer-reviewed research.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Feature Importance Correlation Analysis in Compound Activity Prediction

| Protocol Step | Technical Specification | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Curation | Select >60 active compounds per target from diverse chemical series, with high-confidence activity data. Use consistently sourced compounds without bioactivity annotations as the negative class. | Ensures model robustness and generalizability. A consistent negative reference state allows for meaningful cross-target comparisons. [1] |

| 2. Molecular Representation | Encode compounds using a topological fingerprint (e.g., a 1024-bit binary vector). | Provides a standardized, target-agnostic molecular representation that captures structural features without introducing target-specific bias. [1] |

| 3. Model Training | Train a Random Forest (RF) classifier for each target to distinguish active from inactive compounds. Use the Gini impurity criterion for node splitting. | RF is a robust, widely-used algorithm. The Gini impurity provides a transparent and computationally efficient measure for quantifying feature importance. [1] |

| 4. Feature Importance Calculation | For each RF model, calculate the Gini importance for each feature (fingerprint bit). The importance is the normalized sum of impurity decreases for all nodes split on that feature. | Quantifies the contribution of each structural feature to the model's predictive accuracy, creating a unique "feature importance profile" for the target. [1] |

| 5. Correlation Analysis | Calculate pairwise Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between the feature importance rankings of all target models. | Identifies targets with similar binding characteristics or functional relationships, independent of chemical structure similarity. [1] |

| 6. Validation & Interpretation | Correlate high feature importance correlation with shared active compounds and Gene Ontology (GO) term overlap (Tanimoto coefficient). | Validates that the computational signature reflects biological reality, revealing both similar binding sites and functional relationships. [1] |

Diagram 1: Workflow for Feature Importance Correlation Analysis

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing the ML methodologies described requires a foundation of specific data, software, and analytical tools. The table below details the key "research reagents" for building a feature importance-driven research program.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Drug Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Sources / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Bioactivity Data | Training and validating predictive ML models for target engagement and compound efficacy. | Public databases (ChEMBL, PubChem) and proprietary corporate data. Data quality is paramount. [6] [1] |

| Molecular Descriptors & Fingerprints | Numerically representing chemical structures for computational analysis. | Topological fingerprints, graph-based representations, physicochemical descriptors. [1] |

| ML Programmatic Frameworks | Providing the algorithms and infrastructure to build, train, and deploy ML models. | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn. Open-source frameworks enable high-performance computation. [13] |

| Feature Importance Algorithms | Quantifying the contribution of input variables to a model's predictions. | Gini importance (Random Forest), SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), others. Critical for model interpretation. [16] [1] |

| Process Development Data | Data on reaction parameters, yields, and impurities for optimizing chemical synthesis. | Generated internally or by CDMOs. Used to build ML models for route scouting and process optimization. [16] |

| Centralized Laboratory Data & Metrics | Objective performance data (e.g., turn-around-time, error rates) to monitor clinical trial efficiency. | Key for managing outsourcing relationships and ensuring data quality in clinical development. [17] |

Implementation and Impact Across the Development Lifecycle

The integration of AI and feature analysis is not confined to a single stage of development; it offers efficiency gains from discovery through manufacturing. The following diagram illustrates the application of these tools across the key phases of drug development.

Diagram 2: AI/ML Application Across the Drug Development Lifecycle

Drug Discovery: AI technologies like deep learning and generative adversarial networks (GANs) are revolutionizing early-stage discovery. They enable precise molecular modeling, prediction of binding affinities, and de novo generation of novel compounds with desired properties [6]. For instance, AlphaFold's ability to predict protein structures with near-experimental accuracy profoundly impacts target selection and drug design [6]. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the technical protocol, feature importance correlation can systematically map relationships between protein targets, revealing shared binding characteristics and unexpected functional relationships, which can illuminate new therapeutic opportunities and streamline target prioritization [1].

Preclinical and Clinical Development: In preclinical stages, ML models predict drug toxicity and efficacy, reducing reliance on animal models and accelerating this critical safety assessment phase [6]. AI also plays a crucial role in drug repurposing, identifying new therapeutic uses for existing drugs by analyzing large datasets of drug-target interactions [6]. In clinical trials, AI optimizes patient recruitment by processing Electronic Health Records (EHRs), designs adaptive trial protocols, and helps predict outcomes, thereby increasing the likelihood of trial success and reducing one of the most costly phases of development [6] [18].

Process Development and Manufacturing: This is where feature importance analysis delivers direct and measurable efficiency gains. ML models, including sequential learning, can analyze experimental data to identify the most influential process parameters controlling critical quality attributes (CQAs) like yield and impurity profiles [16]. This allows for accelerated experimentation, often requiring fewer physical experiments to establish a scalable process [16]. ML also expedites analytical method development and predicts process performance during scale-up, reducing the risk of costly tech transfer failures and ensuring consistent product quality [16]. The FDA emphasizes that effective use of such quality metrics is a hallmark of a mature quality system, contributing to sustainable compliance and a reduced risk of supply chain disruptions [19].

The business need for efficiency in drug development is no longer met by incremental process improvements alone. The convergence of massive biological data, advanced ML algorithms, and powerful computing has created an inflection point. Companies that strategically adopt these technologies, particularly those leveraging interpretable ML and feature importance analysis, are positioning themselves as future-ready leaders [14].

This transition is evidenced by the growing gap between "platform pioneers" and "legacy laggards." The most future-ready pharmaceutical companies—those with robust financials, relentless innovation, and control over diversified ecosystems—are characterized by their early and integrated adoption of AI-enabled R&D [14]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering the synthesis of experimental data and machine learning feature importance is no longer a niche specialization but a core competency. It is the key to unlocking more efficient, cost-effective, and successful drug development pipelines, ultimately fulfilling the industry's promise of delivering transformative therapies to patients in need.

In the development of synthetic routes, particularly for high-value molecules like active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), researchers must simultaneously optimize three critical dimensions: reaction yield, product purity, and process scalability. These objectives are often in tension; for instance, conditions that maximize yield may generate more impurities, while steps to enhance purity could compromise scalability through complex purification sequences. Traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) optimization approaches struggle to capture the complex, non-linear interactions between multiple synthesis parameters. However, a paradigm shift is underway, driven by the integration of machine learning (ML) and high-throughput experimentation (HTE). These technologies enable a multivariate approach, revealing complex parameter interactions and accelerating the identification of optimal conditions that balance these competing objectives. This whitepaper explores how modern data-driven methodologies are transforming the optimization of chemical synthesis, providing researchers with powerful tools to navigate this complex design space.

Foundational Synthesis Parameters and Their Complex Interactions

The relationship between synthesis parameters and outcomes is rarely linear. Understanding these complex interactions is the first step toward effective optimization. Key parameters can be broadly categorized into chemical and process variables.

Chemical and Process Parameters

Chemical parameters include fundamental variables such as reactant stoichiometry, catalyst loading, solvent choice, and reagent concentration. Process parameters encompass reaction time, temperature, mixing efficiency, and energy input mode (e.g., thermal, mechanical). A critical interaction often exists between reaction time and product purity. In the synthesis of an amide, extended reaction times (from 2 to 15 minutes) increased the yield from 43% to 64% but simultaneously increased the number of lipophilic by-products, ultimately reducing the final purity of the isolated product after orthogonal purification [20]. This demonstrates a direct trade-off where maximizing one objective (yield) can adversely affect another (purity).

The Scalability Challenge

Scalability introduces additional constraints. A synthetic route viable at the milligram scale may fail in kilogram-scale production due to challenges in heat transfer, mass transfer, or workup procedures. For example, intermediates with poor stability can degrade during storage, and complex purification steps like chromatography are often impractical at large scale. A newly reported scalable synthesis of a key peptide therapeutic intermediate addressed this by designing a highly stable, crystalline benzotriazole-based intermediate. This intermediate was suitable for facile crystallization and bulk storage, enabling a scalable route that achieved a purity exceeding 99.7% [21]. This highlights how intermediate properties are themselves critical synthesis parameters influencing scalability.

Table 1: Key Synthesis Parameters and Their Impact on Optimization Objectives

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Primary Impact on Yield | Primary Impact on Purity | Scalability Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Reactant Stoichiometry | Direct; optimal ratio maximizes conversion | High excess can generate new impurities | Cost and waste management of excess reagents |

| Chemical | Catalyst Loading & Type | Critical for reaction kinetics & conversion | Impacts selectivity; metal residues can be impurities | Catalyst cost, availability, and removal |

| Chemical | Solvent System | Affects solubility and reaction kinetics | Influences by-product formation and purification | Green chemistry principles, recycling, safety |

| Process | Reaction Time | Generally increases conversion to a point | Can increase degradation by-products over time | Throughput and production capacity |

| Process | Reaction Temperature | Accelerates kinetics; may shift equilibrium | High T can lead to decomposition and side-reactions | Heat transfer and safety at large scale |

| Process | Mixing Efficiency | Critical for multi-phase reactions | Ensures homogeneity and consistent product quality | Mass transfer limitations in large reactors |

| Intermediate Properties | Crystallinity | N/A | Enables effective purification by recrystallization | Critical for isolating pure solid intermediates at scale |

Machine Learning as a Strategic Tool for Deconvolution and Prediction

Machine learning excels at modeling complex, non-linear systems where traditional methods fail. By treating a synthesis as a multi-parameter system, ML models can predict outcomes and identify the relative importance of each input feature, guiding efficient experimentation.

Surrogate Modeling for Complex Processes

In catalytic CO₂ hydrogenation to methanol, a physics-based process model was used to generate training data for four ML surrogate models: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [22]. The GPR model emerged as the best performer, achieving exceptional accuracy (R² > 0.99) in predicting CO₂ conversion and methanol yield. This high-fidelity surrogate model was then coupled with a multi-objective optimization algorithm (NSGA-II) to rapidly identify Pareto-optimal conditions that balance the two conflicting objectives, a task that would be computationally prohibitive using the original physics-based model alone [22].

Feature Importance for Mechanistic Insight

Beyond prediction, ML models provide deep insight through feature importance analysis. For instance, in developing a model to predict the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity of diverse catalysts, researchers started with 23 features. Through rigorous feature engineering, they minimized the model to just 10 key features without sacrificing predictive accuracy (R² = 0.922) [23]. This process identifies the most descriptive parameters, streamlining future experimental design and often pointing to underlying chemical mechanisms. Similarly, Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) analysis can be employed to quantify the contribution of each input variable (e.g., temperature, pressure, H₂/CO₂ ratio) to the model's predictions for CO₂ conversion and methanol yield [22].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of data generation, model training, and multi-objective optimization that enables this powerful approach.

A Framework for Mechanochemistry

The application of ML is expanding to non-traditional syntheses like mechanochemistry. Predicting the yield for the mechanochemical regeneration of NaBH₄ is challenging due to complex parameter interactions. A two-step Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model was developed that isolated the dominant effect of milling time before modeling the residual effects of other mechanical and chemical variables. This strategy achieved a high predictive performance (R² = 0.83) and provided valuable uncertainty estimates, establishing a framework for optimizing mechanochemical processes [24].

Table 2: Machine Learning Models and Their Applications in Synthesis Optimization

| Machine Learning Model | Typical Use Case | Key Advantages | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | Building surrogate models for complex processes | High accuracy with uncertainty estimates, excels with smaller datasets | Predicting CO₂ conversion and methanol yield [22]; Predicting mechanochemical yield [24] |

| Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) | Regression and classification tasks with tabular data | High predictive performance, handles mixed data types | Used as a surrogate model for methanol synthesis prediction [22] |

| Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) | Predictive modeling with high-dimensional feature spaces | High accuracy, robust to overfitting | Predicting hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity using minimal features [23] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Classification and non-linear regression | Effective in high-dimensional spaces | One of four surrogate models evaluated for methanol production [22] |

| Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) | Multi-objective optimization | Finds a Pareto-optimal set of solutions balancing conflicting objectives | Optimizing for both CO₂ conversion and methanol yield simultaneously [22] |

Integrated Workflows: Combining HTE, ML, and Automation

The full power of ML is realized when it is integrated into a closed-loop workflow that minimizes human intervention. These integrated systems are transforming how chemical reactions are developed and optimized.

The Self-Optimizing Reactor Platform

A standard workflow for organic reaction optimization via ML begins with a carefully designed experiment (DOE), followed by reaction execution in high-throughput systems, data collection via analytical tools, and mapping the data to target objectives [25]. An ML algorithm then analyzes the results and predicts the next set of conditions most likely to improve the outcomes. This recommendation is executed automatically in a closed loop, rapidly converging on optimal conditions. This "self-optimizing" approach has been applied to various reactions, including Buchwald-Hartwig aminations and Suzuki couplings [25].

The Role of High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

HTE platforms are the engine for data generation in these workflows. They use automation and parallelization to execute and analyze large numbers of experiments simultaneously. Commercial and custom-built platforms can perform hundreds of reactions in multi-well plates, systematically exploring a vast parametric space of categorical and continuous variables [25]. This generates the high-quality, consistent datasets required to train robust ML models, moving synthesis from a qualitative, intuition-guided process to a quantitative, data-driven one.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of advanced synthesis and optimization strategies relies on a foundation of specific chemical tools and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Synthesis Optimization

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in Synthesis Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| N-Acylbenzotriazole Intermediates | Novel Synthetic Intermediate | Provides a stable, crystalline alternative to unstable acid chlorides, enabling high-purity, scalable amide bond formation for APIs [21]. |

| DEM-Derived Mechanical Descriptors | Computational Feature | Device-independent descriptors (e.g., Ēn, Ēt, fcol/nball) that characterize milling energy, enabling ML model transfer across different mechanochemical equipment [24]. |

| Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) | Software Library | An open-source Python library for generating synthetic tabular data, useful for augmenting small experimental datasets to improve ML model training [26]. |

| Benzotriazole Chemistry | Synthetic Methodology | Enables mild amide bond formation conditions, minimizing impurity generation (e.g., trimers, tetramers) and simplifying purification [21]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | ML Interpretability Tool | Explains the output of any ML model by quantifying the contribution of each input feature to the final prediction, identifying key synthesis parameters [22]. |

| Faker | Software Library | A Python library for generating synthetic but structurally realistic data (e.g., patient records, transactions), useful for testing data pipelines before real data is available [26]. |

The integration of machine learning with high-throughput experimentation marks a fundamental shift in chemical synthesis. By moving beyond one-dimensional optimization, researchers can now efficiently navigate the complex trade-offs between yield, purity, and scalability. The methodologies outlined—from training surrogate models for multi-objective optimization to using feature importance for mechanistic insight—provide a robust framework for modern chemical development. As these data-driven approaches mature and become more accessible, they will continue to accelerate the discovery and scalable production of vital molecules, from life-saving pharmaceuticals to materials for a sustainable energy future. The key synthesis parameters are no longer just chemical and process variables; they now also include the data, algorithms, and automated platforms that allow us to understand and control them with unprecedented precision.

The identification of synthesis parameters that genuinely influence outcomes is a cornerstone of research in fields from drug development to materials science. Traditional machine learning (ML) models excel at uncovering correlations but often fail to distinguish true causal drivers from merely correlated confounders. This whitepaper details how next-generation causal machine learning (CML) methodologies are overcoming this limitation. We provide a technical guide on moving from correlation to causation, focusing on experimental protocols for high-dimensional hypothesis testing and robust causal effect estimation. Framed within a broader thesis on synthesizing parameters with ML feature importance research, this document equips scientists with the tools to identify the sparse subset of parameters that truly control outcomes, thereby accelerating rational discovery and optimizing experimental resources.

In scientific research, the leap from observing a correlation to establishing a causation is paramount. Standard ML models, while powerful for prediction, are designed to identify patterns and associations in data; they are not inherently built to answer causal questions. Consequently, traditional feature importance scores derived from models like Lasso or Random Forest can be misleading, often highlighting non-causal but confounded parameters as "important" [27]. This is a critical failure mode for research, as it can misdirect experimental efforts toward parameters that have no real controlling power over the desired outcome.

The limitations of conventional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including their high cost, time-intensive nature, and limited generalizability, have driven the exploration of real-world data (RWD) and advanced analytics [28]. However, observational data is prone to confounding biases and reverse causality, making causal inference challenging [29]. For instance, a parameter might appear important not because it causes the outcome, but because it is correlated with an unmeasured true causal factor. Causal AI is specifically designed to address this, identifying and understanding cause-and-effect relationships to move beyond simple correlation [30].

Methodological Foundations: From Associational to Causal Feature Importance

The Pitfalls of Traditional Feature Importance

Traditional ML models operate on the first level of the Pearl Causal Hierarchy (PCH), which is concerned with associations and observations [31]. When these models calculate feature importance, they are measuring a feature's utility for prediction, not its causal influence. This can lead to several problems:

- Confounding: An unmeasured variable influences both the feature and the outcome, creating a spurious association [29].

- Reverse Causality: The outcome influences the feature, rather than the other way around, which is a particular concern in studies with short follow-up periods [29].

- Selection Bias: The way data is collected or subjects are selected can distort the apparent relationship between a feature and an outcome [29].

In high-throughput experimentation (HTE), these pitfalls can lead researchers to optimize non-causal variables, wasting resources and delaying discovery [27].

The Causal Machine Learning Paradigm

Causal Machine Learning (CML) integrates ML algorithms with causal inference principles to estimate treatment effects and counterfactual outcomes from complex, high-dimensional data [28]. It aims to answer questions at the second level of the PCH (interventions) and the third level (counterfactuals) [31]. A core concept in CML is identifiability—whether a causal query can be answered from the available data under a set of plausible assumptions [31].

Key CML frameworks include:

- Potential Outcomes Framework: Defines the causal effect for a subject as the difference between the outcome observed with and without the exposure [29].

- Structural Causal Models (SCMs): Use graphical models to explicitly represent causal assumptions and refine treatment effect estimation [28].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional ML and Causal ML Approaches to Feature Importance

| Aspect | Traditional ML Feature Importance | Causal ML Feature Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Predictive accuracy | Causal effect estimation |

| Level in PCH | Level 1 (Association) | Level 2 (Intervention) & Level 3 (Counterfactual) |

| Handling of Confounding | Often fails to account for it, leading to bias | Explicitly models and adjusts for confounders |

| Output | Score for predictive utility | Unconfounded estimate of a parameter's causal effect |

| Key Assumptions | Few, primarily related to model fit | Strong, untestable assumptions (e.g., unconfoundedness) |

Core Experimental Protocol: Establishing Causal Links

A robust methodology for establishing causal feature importance involves combining advanced statistical techniques with rigorous hypothesis testing. The following workflow, adapted from research in materials science, provides a generalizable experimental protocol [27].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Data Preparation and Confounder Control Collect high-dimensional data on synthesis parameters (treatments) and outcomes. The key is to measure and include all plausible confounding variables—parameters that may influence both the treatment and the outcome. In the DML framework, all other parameters are controlled for as potential confounders when estimating the effect of one parameter at a time [27].

Step 2: Causal Effect Estimation via Double/Debiased Machine Learning (DML) DML is a robust method for estimating causal effects from observational data. Its "double" or "debiased" nature comes from using cross-fitting to prevent overfitting and to yield unbiased estimates of a parameter's effect [27].

- Split the dataset (K-fold cross-validation).

- For each parameter of interest: a. Use ML models (e.g., Lasso, Random Forest) on the training folds to predict both the outcome and the treatment parameter using all other parameters as features. b. Compute the residuals (the differences between actual and predicted values) for both the outcome and the treatment on the test folds. c. Regress the outcome residuals on the treatment residuals. The coefficient from this regression is the unconfounded causal effect of the parameter on the outcome.

Step 3: High-Dimensional Hypothesis Testing with False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control After applying DML to all parameters, you obtain a causal effect estimate and a p-value for each.

- Apply the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to the list of p-values [27].

- This procedure controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR)—the expected proportion of false positives among the parameters declared significant. This is crucial in high-dimensional settings where testing hundreds of parameters simultaneously inflates the risk of false discoveries.

Step 4: Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

- Synthetic Experiments: Use fully or semi-synthetic data with known ground truth to validate the entire pipeline. This is essential for building trust in CML methods, as real-world ground truth is often unavailable [31].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Quantify how robust the causal conclusions are to potential violations of the unconfoundedness assumption (e.g., the presence of an unmeasured confounder).

Implementing a causal feature importance analysis requires a suite of computational tools and methodological approaches.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Causal Feature Importance Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double Machine Learning (DML) | Statistical Method | Provides robust, debiased estimation of causal effects from observational data by using ML to model outcomes and treatments. | Estimating the true effect of a synthesis parameter on material property while controlling for all other parameters. [27] |

| Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure | Statistical Protocol | Controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR) when performing multiple hypothesis tests, reducing false positives. | Identifying which of hundreds of tested parameters are truly causal drivers of a biological outcome. [27] |

| Propensity Score Methods | Statistical Method | Mitigates selection bias by modeling the probability of treatment assignment (e.g., inverse probability weighting, matching). | Creating a balanced comparison group in RWD to emulate a randomized trial when evaluating drug effects. [28] [29] |

| Instrumental Variables (IV) | Statistical Method | Addresses unmeasured confounding by leveraging a variable that influences the treatment but not the outcome directly. | Estimating causal effects in pharmacoepidemiology where unmeasured health status is a confounder. [29] |

| Synthetic Data | Validation Tool | Generated from known causal models to provide ground truth for rigorously evaluating and benchmarking CML methods. | Testing the performance of a new causal discovery algorithm before applying it to real, expensive experimental data. [31] |

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

The integration of CML with real-world data (RWD) is transforming pharmaceutical research by generating more comprehensive evidence and accelerating innovation [28]. Key applications include:

- Identifying Subgroups and Refining Treatment Responses: CML can scan large RWD datasets to detect complex interactions and patterns, identifying patient subgroups that demonstrate varying responses to a specific treatment. This enhances precision medicine by targeting populations that benefit most [28].

- Optimizing Clinical Trial Design: Causal AI can provide prescriptive recommendations on eligibility criteria, assessment schedules, and protocol design by analyzing historical trial data through a causal lens. This helps distinguish true drivers of trial performance from mere correlations [30].

- Indication Expansion: Drugs approved for one condition often exhibit beneficial effects in others. ML-assisted real-world analyses can provide early signals of such potential, guiding further investigation [28].

The diagram below illustrates how causal inference enhances the analysis of real-world data in a clinical development context.

The journey from correlation to causation is fundamental to scientific progress. As this guide outlines, Causal Machine Learning provides a robust and statistically grounded framework for this transition, moving feature importance from a measure of predictive utility to a quantitative estimate of causal influence. By adopting methodologies like Double Machine Learning and rigorous False Discovery Rate control, researchers in drug development and materials science can confidently identify the key parameters that drive outcomes, optimize experimental resources, and accelerate the pace of discovery. The future of rational design lies in leveraging these advanced causal techniques to illuminate the true paths from synthesis to success.

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Process Chemistry

In the field of machine learning, particularly within high-stakes domains like drug discovery, understanding why a model makes a particular prediction is as crucial as the prediction's accuracy. Feature importance methods provide a suite of tools to peer inside the "black box" of complex models, identifying which input variables most significantly drive predictions. For researchers and scientists, this is not merely a diagnostic exercise but a core component of the scientific process, enabling the validation of models against domain knowledge, the identification of novel biomarkers, and the optimization of synthesis parameters. This guide details three cornerstone methodologies for feature importance—Permutation Importance, Leave-One-Covariate-Out (LOCO), and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)—framing them within the rigorous context of machine-learning-driven research in drug development. These model-agnostic techniques allow for interpretability across a wide range of algorithms, from random forests to deep neural networks, making them indispensable for the modern computational scientist.

Core Methodologies Explained

Permutation Feature Importance

Concept and Theory: Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) is a model-agnostic technique that measures the importance of a feature by quantifying the increase in a model's prediction error after the feature's values are randomly shuffled [32] [8]. This shuffling process breaks the original relationship between the feature and the target variable, allowing you to determine how much the model's performance relies on that particular feature [32]. The underlying logic is intuitive: if a feature is important, corrupting it should lead to a significant degradation in model performance; if it is unimportant, the performance should remain relatively unchanged [8].

Algorithm and Protocol: The standard algorithm for PFI, as outlined by Breiman and later formalized for model-agnostic use, follows a clear, step-by-step process [8]:

- Inputs: A trained predictive model

m, a feature matrixX, a target vectory, and an error metricL(e.g., Mean Squared Error for regression or accuracy for classification). - Compute Reference Score: Calculate the original model error on the unmasked data:

e_orig = L(y, m.predict(X)). - Iterate and Permute: For each feature

jin the dataset:- For

kin1 ... Krepetitions (to obtain a stable estimate):- Create a modified dataset

X_perm_jby randomly shuffling the values of featurej. - Compute the model error

e_perm_j,kon this permuted dataset.

- Create a modified dataset

- Calculate the importance

i_jfor featurejas the differencei_j = (1/K) * Σ (e_perm_j,k) - e_origor the ratioi_j = e_perm_j / e_orig[32] [8].

- For

A critical best practice is to compute PFI on a held-out validation or test set, not the training data. Using training data can yield misleading, overly optimistic importance values for features that the model has overfitted to, failing to reveal which features truly contribute to generalizable performance [32] [8].

Strengths and Limitations:

- Strengths: PFI has a straightforward interpretation linked directly to model performance, is model-agnostic, and does not require retraining the model, making it computationally efficient [8] [33]. It also automatically accounts for all interaction effects a feature participates in [8].

- Limitations: Its primary weakness is handling correlated features. Permuting one feature in a correlated pair can create unrealistic data points, and the importance may be split between the correlated features, undervaluing both [8] [34]. Furthermore, PFI only indicates a feature's overall effect on the model error, not the direction (positive or negative) of its influence on the prediction [8].

Leave-One-Covariate-Out (LOCO)

Concept and Theory: LOCO is a robust, model-agnostic method that quantifies a feature's importance by measuring the change in a model's predictive performance when that feature is entirely removed from the dataset [35]. This approach directly assesses the contribution of a covariate by comparing a full model with a model that is refit without it. The core parameter of interest is the LOCO importance, defined for a feature X_j as ψ_{0,j}^{loco} = V(f_0, P_0) - V(f_{0,-j}, P_{0,-j}), where V is a performance metric, f_0 is the full model predictor, and f_{0,-j} is the model learned without X_j [35].

Algorithm and Protocol: The experimental protocol for LOCO involves refitting the model for each feature under investigation:

- Train Full Model: Fit your chosen model

fusing all features and the training data. Evaluate its performance on a test set to establish a baseline errore_orig. - Iterate and Retrain: For each feature

j:- Create a new training dataset

X_{-j}by excluding featurej. - Retrain an otherwise identical model

f_{-j}onX_{-j}. - Compute the error

e_{-j}of this new model on the modified test set (also excluding featurej).

- Create a new training dataset

- Calculate Importance: The LOCO importance for feature

jisΔ_j = e_{-j} - e_orig. A large increase in error indicates the omitted feature was important.

Strengths and Limitations:

- Strengths: LOCO provides a direct and intuitive measure of a feature's contribution by simulating its absence. It is highly robust and forms the basis for valid inference in high-dimensional settings, including the construction of prediction intervals [35].

- Limitations: The most significant drawback is computational cost, as it requires retraining the model for every feature, which can be prohibitive with complex models and large datasets [35] [34]. Like PFI, it can also be affected by correlated features, as the model might compensate for a removed feature by using a correlated one still present in the set [34].

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)

Concept and Theory: SHAP is a unified approach to interpreting model predictions based on cooperative game theory, specifically Shapley values [36] [37]. It explains the output of a machine learning model by distributing the "payout" (the difference between the model's prediction for a specific instance and the average model prediction) among the input features fairly. The core idea is that the prediction f(x) for an instance can be represented as the sum of the contributions of each feature: f(x) = base_value + Σ φ_j, where φ_j is the SHAP value for feature j [36] [37]. A positive SHAP value indicates a feature pushes the prediction higher than the baseline, while a negative value pulls it lower.

Algorithm and Protocol: Exact calculation of SHAP values is computationally intensive, but efficient model-specific approximations (e.g., for tree-based models) exist. The general protocol for a single instance is:

- Define the "Game": The "players" are the feature values of the instance to be explained, and the "payout" is the prediction for that instance.

- Compute Marginal Contributions: For each feature

j, compute its average marginal contribution across all possible coalitions (subsets) of other features. This involves:- Taking a subset

Sof features that does not includej. - Computing the model's prediction with the feature values in

S. - Computing the prediction when feature

jis added toS. - The difference between these two predictions is the marginal contribution of