Beyond Absorption: Precision Photochemistry Through Quantum Yield and Molar Extinction

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate and leverage the critical, and often decoupled, relationship between quantum yield (Φ) and molar extinction coefficient...

Beyond Absorption: Precision Photochemistry Through Quantum Yield and Molar Extinction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate and leverage the critical, and often decoupled, relationship between quantum yield (Φ) and molar extinction coefficient (ε). Moving beyond the traditional paradigm that prioritizes maximum light absorption, we explore the foundational principles of 'Precision Photochemistry,' where the interplay of ε, Φ, concentration, and irradiation time dictates photochemical outcomes. We detail methodological advances for accurate measurement, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present validation strategies for applications ranging from photodynamic therapy and drug uncaging to materials science. By synthesizing these concepts, this review empowers scientists to strategically design and control photochemical systems for enhanced efficacy and specificity in biomedical research.

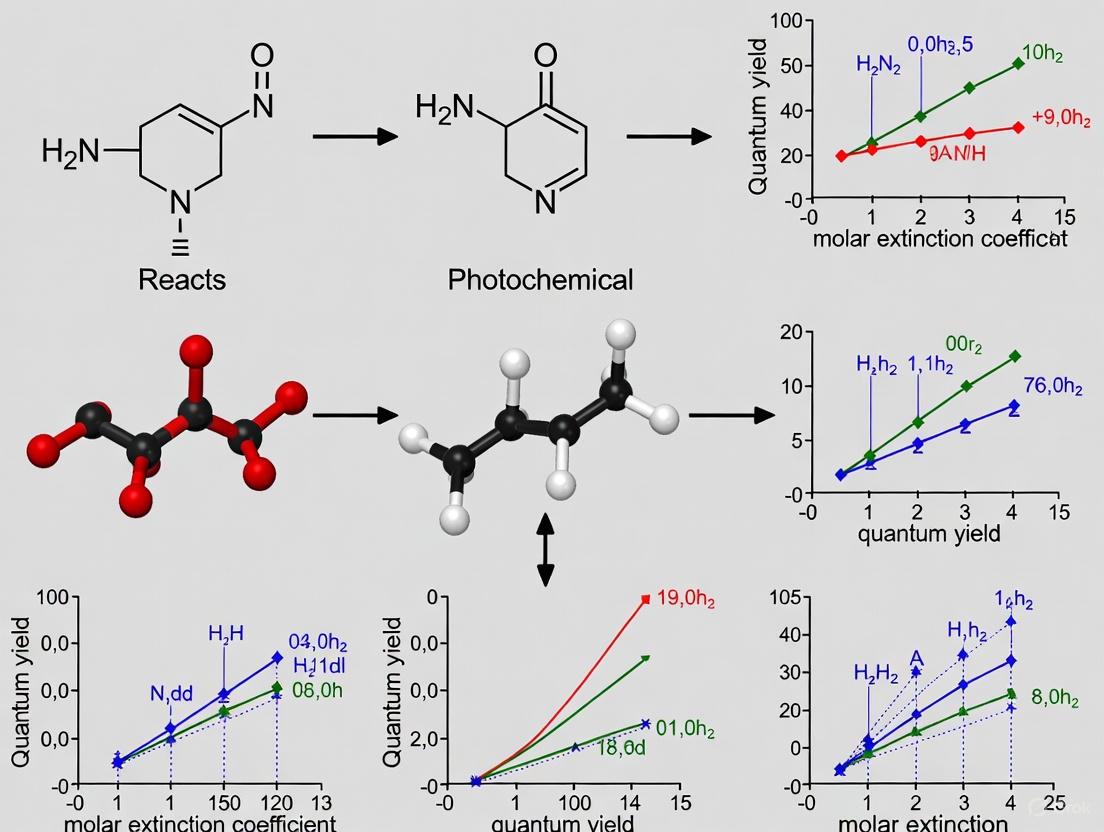

The Four Pillars of Precision Photochemistry: Why Absorptivity Does Not Guarantee Reactivity

The First Law of Photochemistry, established in the 19th century by Theodor Grotthuss and John Draper, states a fundamental principle: light must be absorbed by a system to cause a photochemical reaction [1] [2]. This foundational rule, often called the Grotthuss-Draper Law, has guided photochemical research for centuries, establishing absorption as the essential gateway to photochemical processes. For generations, this logically directed researchers to irradiate samples at wavelengths corresponding to maximum absorption (λmax) to induce the greatest photochemical change [2]. However, contemporary research reveals a more nuanced reality: not all absorbed photons are equally efficient at driving chemical reactions [3] [2]. The discovery that photochemical action often does not align perfectly with molar extinction has catalyzed the growth of Precision Photochemistry, a field dedicated to exploiting the intricate relationship between a molecule's absorption and its wavelength-dependent reactivity [3] [2].

This guide objectively compares the performance of different photochemical systems by examining the critical interplay between molar extinction coefficient (ελ) and quantum yield (Φλ), two paramount parameters in photochemical research. The molar extinction coefficient quantifies how strongly a species absorbs light at a specific wavelength, while the quantum yield measures the efficiency with which an absorbed photon produces a specific reaction [4] [2] [5]. The product of these two wavelength-dependent parameters determines the overall effectiveness of a photochemical process. Framed within the broader thesis of evaluating quantum yield versus molar extinction, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data and methodologies needed to design more efficient, selective, and predictable photochemical systems, from synthetic pathways to therapeutic applications.

Fundamental Principles: From the Beer-Lambert Law to Quantum Efficiency

The Beer-Lambert Law and Photon Absorption

The empirical Beer-Lambert Law provides the mathematical framework for quantifying light absorption in a homogeneous medium. It states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species (c), the path length the light travels through the solution (l), and the molar extinction coefficient (ελ) at a specific wavelength [4] [2]. The law is expressed as:

[A = \varepsilon_\lambda \cdot c \cdot l]

This relationship implies that the probability of a photon being absorbed is constant at any point within the sample, analogous to first-order kinetics [4]. The molar extinction coefficient (ε) is a molecule-specific property that indicates the probability of light absorption at a given wavelength; larger values denote a higher likelihood of absorption [4] [6]. The Beer-Lambert law, however, relies on several assumptions, including that the solution is optically transparent, absorbers act independently of one another, the incident radiation is monochromatic, and the concentration of the ground state is not noticeably affected by the irradiation [4]. Deviations from these assumptions, such as high concentrations leading to chromophore interactions or significant ground-state depletion, can cause non-linear behavior.

Quantum Yield: The Efficiency of Photochemical Conversion

The quantum yield (Φ) is a critical performance parameter that quantifies the efficiency of a photochemical process. It is defined as the number of molecules of a specified event occurring per photon absorbed by the system [2] [5]. For a photochemical reaction, this is typically the number of reactant molecules consumed or product molecules formed divided by the number of photons absorbed. A quantum yield of 1 implies that every absorbed photon results in one unit of the measured event, while a value greater than 1 often indicates a chain reaction.

The apparent quantum yield spectrum (Φλ) describes how this efficiency varies with the wavelength of the incident light [5]. It is a key determinant of photochemical action, as a molecule may absorb strongly at one wavelength (high ελ) but utilize that energy inefficiently (low Φλ), while exhibiting higher reactivity at a wavelength where absorption is weaker [2]. This mismatch between the absorption spectrum and the action spectrum (a plot of biological or chemical effectiveness versus wavelength) is a cornerstone of modern precision photochemistry [2].

Table 1: Key Photochemical Parameters and Their Definitions

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molar Extinction Coefficient | ε_λ | Measure of how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength. | Determines the probability of photon absorption. High ε enables thinner samples or lower concentrations. |

| Quantum Yield | Φ_λ | Efficiency of a photophysical or photochemical process, defined as events per photon absorbed. | Determines the practical outcome of absorption. A high Φ is crucial for efficient applications. |

| Absorbance | A | Logarithmic measure of the amount of light absorbed by a sample. | A = ε_λ * c * l (Beer-Lambert Law). The experimentally measured quantity. |

| Optical Density | OD | Often used interchangeably with Absorbance. | A concentration- and path-length-dependent representation of absorption. |

| Photon Absorption Efficiency | PAE | Parameter obtained by integrating the product of the absorption and emission spectra in terms of photons [6]. | Predicts the most efficient photoinitiator/light source pairs for a photochemical process. |

Experimental Comparison: Case Studies Across Disciplines

Precision Photochemistry and Wavelength-Orthogonal Uncaging

A seminal demonstration of precision photochemistry is found in wavelength-orthogonal photo-uncaging systems. The reactivity of such a system is governed by the interplay of four pillars: molar extinction (ελ), quantum yield (Φλ), concentration (c), and irradiation time (t) [2]. Research has shown that the photochemical action often does not align with the molar extinction profile. For instance, an oxime ester photoinitiator exhibited enhanced reactivity when irradiated with light red-shifted relative to its λmax [2].

The competitive yield between two hypothetical uncaging molecules, A and B, evolves over time. Simulations show that at wavelengths below 430 nm, product A' is formed rapidly and selectively initially. However, as reactant A is consumed, the competing cleavage of B becomes more prominent, driving the competitive yield back toward zero [2]. This dynamic interplay underscores that selectivity is not just a function of wavelength but also of reaction progress and concentration changes. The concept of reaction trajectories—plotting the time-dependent concentration evolution of released products—provides a more complete picture of system behavior than a single time-point measurement [2].

Table 2: Simulated Competitive Yield in a Binary Uncaging System Over Time [2]

| Irradiation Wavelength | Initial Preferred Product (t₀) | Competitive Yield Trend (over 5 minutes) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 430 nm | A' | High initial selectivity for A', decreases as B' forms later | Initial preference erodes due to depletion of A, allowing B to react. |

| 430 - 440 nm | B' | High initial selectivity for B', decreases as A' forms later | As B is consumed, the system becomes more favorable for A to react. |

| > 440 nm | - | Lower overall conversion | Demonstrates the need to balance both ελ and Φλ for practical efficiency. |

Environmental Photochemistry: Photomineralization in Arctic Waters

In environmental science, the photomineralization of dissolved organic matter (DOM) to CO₂ in Arctic freshwaters provides a critical case study of quantum yield in natural systems. The apparent quantum yield spectrum for photomineralization (φPM,λ) is a key driver of this process, quantified as moles of CO₂ produced per mole of photons absorbed by chromophoric DOM (CDOM) [5]. Direct measurement using LED-based approaches reveals that φPM,λ is not constant but depends on environmental factors.

The magnitude of φPM,λ decreases exponentially with increasing wavelength from the UV to the visible spectrum [5]. Furthermore, its value is highly dynamic: it can decrease by up to 92% with increasing cumulative light absorbed by CDOM, indicating the rapid depletion of a photo-labile DOM fraction [5]. This introduces the concept of "substrate limitation" in photochemistry. The controlling factors for φPM,λ in these waters include:

- Aromatic DOM and Dissolved Iron: Waters with higher aromatic DOM and dissolved iron exhibited higher φPM,λ across all wavelengths [5].

- Light Exposure History: The cumulative light absorbed by CDOM, which increases with the water's residence time in sunlit surface waters, is a critical control. As the most photo-labile DOM is consumed, the remaining pool is less reactive, lowering the observed quantum yield [5].

The shape of the φPM,λ spectrum strongly influences environmental rates. A shallower slope (higher efficiency in the visible region) can result in water column photomineralization rates that are double those calculated using a steeper slope, because the visible region contains over 90% of the daily photon flux [5].

Dental Photoinitiators: Optimizing Photon Absorption Efficiency

The field of dental composites provides a classic industrial application where matching extinction with the light source is paramount. The cure of dental resins relies on photoinitiators like camphorquinone (CQ), phenylpropanedione (PPD), and acylphosphine oxides (Lucirin TPO, Irgacure 819) [6]. The photon absorption efficiency (PAE) is a calculated parameter that integrates the product of the photoinitiator's absorption spectrum and the light curing unit's (LCU) emission spectrum, in terms of photons, to predict the most efficient LCU/photoinitiator pair [6].

Table 3: Molar Extinction Coefficients (ε) of Dental Photoinitiators and Optimal Light Curing Units [6]

| Photoinitiator | Absorption Maxima (λ_max) | Molar Extinction Coefficient at λ_max (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Molar Extinction at 470 nm (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Most Efficient Light Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camphorquinone (CQ) | ~470 nm | ~20,000 | ~20,000 | QTH Lamp |

| Phenylpropanedione (PPD) | ~400 nm | ~50,000 | ~20,000 | Similar for QTH and high-power LED |

| Monoacylphosphine Oxide (Lucirin TPO) | ~380 nm | ~40,000 | Very Low | QTH Lamp |

| Bisacylphosphine Oxide (Irgacure 819) | ~370 nm | ~30,000 | Very Low | High-power LED |

This comparative data reveals key design principles:

- Although PPD and CQ have similar absorbance at 470 nm, PPD has a significantly higher molar extinction in the UV-A/blue region, making it a potent alternative [6].

- Photoinitiators like Lucirin TPO and Irgacure 819 have primary absorption peaks in the UV-A, making them more efficiently activated by the broad-spectrum quartz-tungsten-halogen (QTH) lamp than by early blue-light LEDs [6].

- The PAE metric successfully predicts that a high-power LED unit can be more efficient for Irgacure 819 than the QTH unit, despite the spectral mismatch, due to its high intensity in the region where Irgacure does absorb [6]. This underscores that photon flux, not just spectral overlap, is critical.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photochemical Research

| Item | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) | The light-absorbing fraction of dissolved organic matter in natural waters. | Used as a natural photoinitiator to study photomineralization and carbon cycling in environmental systems [5]. |

| Oxime Ester Photoinitiators | A class of photoinitiators that undergo cleavage upon light absorption to generate radicals. | Model compounds for studying red-shifted reactivity and wavelength-orthogonal reactions in precision photochemistry [2]. |

| Camphorquinone (CQ) | A solid yellow α-diketone that absorbs blue light (~470 nm). | The most common photoinitiator in dental resins, often used with an amine co-initiator [6]. |

| Acylphosphine Oxide Photoinitiators | Photoinitiators (e.g., Lucirin TPO, Irgacure 819) with strong absorption in the UV-A region. | Used in dental resins and coatings to reduce yellowing and improve cure speed in the presence of a broad-spectrum light source [6]. |

| LED-Based Irradiation Systems | Light sources emitting narrow-banded, tunable light. | Essential for directly quantifying wavelength-dependent quantum yield spectra (action plots) with high precision [2] [5]. |

Core Experimental Protocols

Determining Molar Extinction Coefficients

Methodology: Prepare solutions of the chromophore at known, low concentrations (typically ensuring absorbance < 0.6 to avoid inner-filter effects) in a spectroscopically suitable solvent [4] [6]. Use a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to record the absorption spectrum across the relevant wavelength range. The molar extinction coefficient (ελ) is calculated using the Beer-Lambert law (A = ελ * c * l), where A is the measured absorbance, c is the concentration in mol L⁻¹, and l is the path length in cm [6]. The values are typically reported in units of M⁻¹cm⁻¹.

Considerations: Ensure the compound is stable in the solvent and does not react during measurement. Use multiple concentrations to verify adherence to the Beer-Lambert law and rule out aggregation effects [4].

Quantifying Wavelength-Dependent Quantum Yields (Action Plots)

Methodology: This is a two-part measurement requiring both actinometry (to measure photons absorbed) and product quantification.

- Irradiation: Expose the sample to monochromatic light (e.g., from an LED or laser). The photon flux of the incident light must be accurately measured, often using a chemical actinometer [2] [5].

- Product Analysis: Quantify the amount of reactant consumed or product formed using an appropriate analytical technique (e.g., chromatography, spectroscopy, or gas measurement for CO₂) [5].

- Calculation: The quantum yield at a specific wavelength (Φ_λ) is calculated as the number of moles of product formed (or reactant consumed) divided by the number of moles of photons absorbed by the sample at that wavelength [5].

Considerations: The experiment should be designed so that a small fraction (typically <5%) of the reactant is consumed to avoid significant changes in concentration and inner-filter effects during the irradiation. The use of LED-based systems has greatly facilitated the direct and rapid quantification of these action plots [2] [5].

Visualizing Photochemical Relationships and Workflows

The Four Pillars of Precision Photochemistry

This diagram illustrates the four interdependent factors that dictate the outcome of a photochemical reaction in the framework of Precision Photochemistry.

Key Experimental Workflow for Photochemical Action Plots

This flowchart outlines the core experimental protocol for determining the wavelength-dependent quantum yield, a key metric in modern photochemistry.

The First Law of Photochemistry remains an inviolable principle: without absorption, there can be no photochemistry. However, as the comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates, absorption is merely the first step in a complex journey. The modern interpretation of this law must account for the critical, and often disconnected, relationship between a molecule's ability to capture a photon (molar extinction) and its efficiency in using that energy to drive a desired reaction (quantum yield).

The experimental evidence from diverse fields—from wavelength-orthogonal uncaging to environmental photomineralization and industrial polymerizations—converges on a single conclusion: the most effective photochemical systems are designed by optimizing the product of ελ and Φλ, not by focusing on either parameter alone. This requires a deep understanding of the four pillars of precision photochemistry: molar extinction, quantum yield, concentration, and time. As photochemistry continues its precision transformation, enabled by advanced light sources and a more sophisticated mathematical framework, researchers and drug developers are empowered to move beyond simple absorption maxima and harness the full, wavelength-dependent potential of light to control molecular outcomes.

In the realm of photochemistry, achieving precise control over molecular transformations requires a deep understanding of four interdependent parameters: molar extinction (ε), quantum yield (Φ), concentration (c), and irradiation time (t). These "four pillars" collectively determine the efficiency and outcome of photochemical processes, from synthetic chemistry to pharmaceutical development [2]. Historically, photochemists primarily focused on maximizing absorption by matching irradiation wavelength with absorption maxima (λmax). However, emerging research demonstrates that this approach is often insufficient, as the wavelength-dependent relationship between ε and Φ frequently dictates photochemical efficiency in unexpected ways [2].

The paradigm of Precision Photochemistry has emerged as a framework that acknowledges the intricate interplay between these four parameters. This approach recognizes that not all absorption events lead equally to desired photochemical outcomes, and that the dynamic balance between ελ, Φλ, c, and t enables unprecedented control over photochemical systems [2]. This comparative guide examines how these fundamental parameters influence photochemical processes across diverse applications, providing researchers with experimental methodologies and analytical frameworks for optimizing photochemical systems in both academic and industrial settings.

Parameter Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

Molar Extinction Coefficient (ε)

The molar extinction coefficient (ε), also referred to as molar absorptivity, quantifies how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a specific wavelength. This parameter follows the Beer-Lambert law, which states that absorbance (A) is proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the path length (l) of light through the solution: A = εcl [4]. The value of ε is intrinsically linked to the probability of an electronic transition occurring within a molecule, with larger values indicating a higher probability of photon absorption [6] [4]. This parameter is wavelength-dependent and is typically reported in units of M⁻¹cm⁻¹.

The magnitude of the molar extinction coefficient depends on fundamental molecular properties, particularly the transition dipole moment, which arises from charge displacement during electronic transitions [4]. Molecules with extensive conjugated systems typically exhibit large ε values, enabling efficient light harvesting across specific spectral regions. For example, common photoinitiators like camphorquinone (CQ) exhibit ε values around 32 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ at 470 nm, while phenylpropanedione (PPD) shows stronger absorption in the UV-A region with ε = 165 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ at 390 nm [6].

Quantum Yield (Φ)

The quantum yield (Φ) represents the efficiency of a photochemical process, defined as the number of events occurring per photon absorbed by the system [7] [8]. For photoluminescence, this is expressed as the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed, while for photochemical reactions, it represents the number of molecules undergoing reaction per absorbed photon [7] [8].

The fluorescence quantum yield (Φf) can be mathematically expressed as the ratio of the radiative rate constant to the sum of all deactivation pathways: Φf = kf/(kf + Σknr), where kf is the radiative decay rate and Σknr represents the sum of all non-radiative decay rates [7] [8]. Quantum yields range from 0 to 1 (or 0% to 100%), with values approaching 1 indicating highly efficient processes. Some chain reactions may exhibit quantum yields exceeding 1, as a single photon can initiate multiple transformations [8].

Concentration (c) and Time (t)

The concentration of photoreactive chromophores (c) directly influences light absorption according to the Beer-Lambert law, but also affects reaction kinetics and pathways through secondary interactions. At higher concentrations, excited-state molecules may interact with ground-state species, leading to self-quenching or alternative reaction pathways [9]. The irradiation time (t), or more precisely the total photon flux delivered to the system, determines the extent of photochemical conversion. The dynamic relationship between concentration and time becomes particularly important in systems where photochemical consumption of reactants alters absorption characteristics throughout the reaction [2].

Comparative Analysis of Parameter Interactions

Quantitative Comparison of Photochemical Systems

Table 1: Comparative Photochemical Parameters Across Molecular Systems

| Compound/System | ε (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Φ | Optimal c Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camphorquinone (CQ) | 32 @ 470 nm [6] | Varies with conditions | ~0.1-1 mM [6] | Dental resins [6] |

| Phenylpropanedione (PPD) | 165 @ 390 nm [6] | Varies with conditions | ~0.1-1 mM [6] | Dental resins [6] |

| Rhodamine 6G | High in visible range | 0.94 (fluorescence) [8] | Low (μM) to avoid self-quenching | Fluorescence standards [8] |

| Phenolic Carbonyls (BrC) | Varies by structure | 0.0005-0.02 (photodegradation) [9] | Concentration-dependent Φ [9] | Atmospheric chemistry [9] |

| Photouncaging Systems | System-dependent | Wavelength-dependent [2] | Critical for orthogonality [2] | Precision photochemistry [2] |

Wavelength Dependence and Spectral Mismatch

A crucial phenomenon in modern photochemistry is the frequent mismatch between absorption spectra (ελ) and photochemical action spectra (Φλ). Research by Barner-Kowollik, Gescheidt, and others has demonstrated that maximum photoreactivity often occurs at wavelengths red-shifted from the absorption maximum [2]. This discovery has profound implications for photochemical optimization, as it reveals that simply irradiating at λmax may not yield optimal results.

The photonic efficiency of a system is determined by the product of ελ and Φλ at each wavelength [2]. This relationship explains why some photoinitiators, such as oxime esters, exhibit enhanced reactivity when irradiated at wavelengths longer than their absorption maxima [2]. This wavelength-dependent behavior necessitates comprehensive action plots that map both absorption and reactivity across the relevant spectral region.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of ε-Φ Spectral Mismatch

| System Studied | Absorption Maximum | Reactivity Maximum | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxime ester photoinitiator [2] | UV region | Red-shifted region | Action plot methodology |

| Photouncaging molecules [2] | Varies by compound | Often red-shifted | Competitive yield analysis |

| Phenolic carbonyls [9] | ~300-340 nm | Wavelength-dependent Φ | LED-based action spectra |

Dynamic Concentration-Time Relationships

The relationship between concentration and time in photochemical systems is inherently dynamic, as photochemical consumption of chromophores continuously alters the system's absorption characteristics. Heckel and colleagues have developed mathematical frameworks that describe how the initial concentration of photoreactive components and their time-dependent depletion affect reaction orthogonality in multi-component systems [2].

In binary mixtures of photoactive compounds, the concept of "competitive yield" reveals how selective formation of one photoproduct evolves over time [2]. For wavelength regimes where one compound reacts preferentially, high selectivity is typically observed initially, but diminishes as the preferred reactant is consumed and competing reactions become more significant [2]. This temporal evolution of selectivity underscores the importance of monitoring and controlling reaction progress rather than relying solely on fixed endpoint analysis.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Determining Wavelength-Dependent Quantum Yields

The accurate measurement of wavelength-dependent quantum yields requires carefully controlled experimental conditions and appropriate actinometry. The following protocol, adapted from studies on phenolic carbonyl photochemistry, exemplifies a robust approach [9]:

Materials and Equipment:

- UV-vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Agilent Cary 60)

- Narrow-bandwidth LED light sources (295-400 nm)

- HPLC system with UV detection

- Temperature-controlled sample chamber

- Chemical actinometer (e.g., 2-nitrobenzaldehyde)

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solutions of the target compound in appropriate solvent, considering solubility and stability.

- Characterize LED emission profiles using spectrophotometry, measuring spectral distribution and intensity.

- Determine photon fluxes using 2-nitrobenzaldehyde actinometry, which has a known constant quantum yield (Φ = 0.43) between 300-400 nm [9].

- For each wavelength, illuminate samples in quartz cuvettes and monitor concentration decay over time via HPLC or spectrophotometry.

- Calculate quantum yields using the formula: Φ = (Δ[C]/Δt) / (Iabs × (1 - 10^(-A))), where Δ[C]/Δt is the rate of concentration change, and Iabs is the absorbed photon flux.

- Account for concentration-dependent effects by measuring Φ at multiple initial concentrations.

This methodology enables direct comparison between photochemical experiments using different laboratory irradiation sources and facilitates extrapolation to environmental or application-specific conditions [9].

Photochemical Action Plot Methodology

Action plots provide comprehensive visualization of the relationship between ελ and Φλ, enabling identification of optimal irradiation wavelengths [2]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Spectral Characterization: Measure absorption spectra (ελ) with high wavelength resolution (preferably 1 nm intervals).

- Wavelength-Resolved Reactivity: Determine Φλ at multiple wavelengths across the absorption spectrum.

- Data Integration: Plot both ελ and Φλ on the same axes to identify potential mismatches.

- Optimization: Identify wavelengths where the product ελ × Φλ is maximized.

Current limitations in action plot methodology include sparse sampling intervals (typically 15 nm) due to the extensive experimental effort required [2]. Future advances in automation are expected to enable higher-resolution action plots with 1 nm intervals, comparable to standard absorption spectroscopy.

Absolute Quantum Yield Measurement

For fluorescence quantum yields, the absolute method using integrating spheres provides the most reliable results, particularly for scattering samples or when reference standards are unavailable [7] [10]. This approach captures all emitted light, eliminating the need for reference compounds with known quantum yields. The quantum yield is calculated by comparing the number of emitted photons to the number of absorbed photons directly [7].

The relative quantum yield method remains valuable for transparent liquid samples, using the formula: Φ = ΦR × (Int/IntR) × ((1-10^(-AR))/(1-10^(-A))) × (n²/nR²), where subscripts R denote reference values, Int represents integrated emission intensity, A is absorbance at excitation wavelength, and n is refractive index [8].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Photochemical Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde | Chemical actinometer [9] | Φ = 0.43 (300-400 nm), stable quantum yield |

| Narrow-band UV-LEDs | Wavelength-selective irradiation [9] | Enable action plot construction |

| Integrating sphere | Absolute quantum yield measurement [7] | Essential for scattering samples |

| Quartz cuvettes | Sample containment for spectroscopy | UV-transparent, various path lengths |

| HPLC with UV detection | Reaction monitoring [9] | Quantifies concentration changes |

| Oxygen-free cuvettes | Phosphorescence studies [10] | Prevents triplet state quenching |

| Reference fluorophores | Quantum yield standards [8] | Quinine (Φ=0.60), Fluorescein (Φ=0.95) |

Visualization of Photochemical Relationships

Four Pillars Interdependence Diagram

Photochemical Action Plot Workflow

The comparative analysis of molar extinction (ε), quantum yield (Φ), concentration (c), and time (t) reveals that successful photochemical system design requires integrated optimization rather than parameter-specific maximization. The emerging paradigm of Precision Photochemistry emphasizes that these four pillars function as an interdependent framework, where the product ελ × Φλ often provides better guidance for wavelength selection than ελ alone [2].

Strategic optimization requires acknowledging the dynamic nature of photochemical systems, where concentration-dependent quantum yields and time-evolving selectivity create complex kinetic landscapes [2] [9]. Furthermore, recognition of the frequent mismatch between absorption maxima and reactivity maxima enables researchers to exploit wavelength-dependent phenomena for enhanced selectivity and efficiency [2].

Future advances in photochemical research will likely focus on increasing the resolution and automation of action plot methodologies, enabling more precise mapping of the ελ-Φλ relationship [2]. Additionally, improved computational models that incorporate all four parameters dynamically will facilitate predictive optimization of photochemical systems for applications ranging from pharmaceutical development to materials science.

For decades, a fundamental assumption has guided photochemical research and application: effective photochemical reactions are optimally achieved by matching the excitation wavelength with the maximum absorption peak ((\lambda_{\text{max}})) of a chromophore. This paradigm is rooted in the Beer-Lambert law and the established principle that only absorbed light can cause chemical change. However, a growing body of cutting-edge research reveals a more complex and often counterintuitive reality: a fundamental mismatch frequently exists between a molecule's absorption profile and its photochemical reactivity [11] [2]. In many cases, the peak efficiency for a photochemical reaction is significantly red-shifted relative to the maximum absorption wavelength [11].

This phenomenon has profound implications across chemical industries, from drug development and biomedical imaging to materials science and additive manufacturing. Relying solely on absorption spectra for wavelength selection can lead to suboptimal reaction yields, inefficient processes, and overlooked opportunities for orthogonal chemical control. This guide objectively compares the performance of various photochemical systems where this mismatch is observed, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to navigate and exploit this critical aspect of photochemical behavior.

Quantitative Case Studies: Reactivity Versus Absorption

The following case studies, compiled from recent literature, provide quantitative evidence of the red-shift phenomenon across diverse photochemical processes.

Table 1: Documented Cases of Red-Shifted Photochemical Reactivity

| Photochemical System / Chromophore | Absorption Maximum (nm) | Reactivity Maximum (nm) | Red-Shift Magnitude (nm) | Reaction Type | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxime Ester Photoinitiator | < 400 | 420 | > 20 | Radical Polymerization Initiation | [11] |

| Styrylquinoxaline | 380 | 450 | 70 | [2+2] Cycloaddition | [11] |

| Styrylpyrene | ~380 | 455 | ~75 | DNA Labeling / Cycloaddition | [11] |

| Anthracene | UV | 410 | Significant (to visible) | Dimerization | [11] |

| α-Acylated Saturated Heterocycles | 340 (n→π*) | 395-405 | 55-65 | Ring Contraction | [12] |

| Pyrene-Chalcone (PyChal) Macromolecules | Varies | Varies | N/A | Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition | [13] |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates that the red-shift is not an isolated occurrence but a observed across reaction classes, including cycloadditions, polymerizations, and complex skeletal editing reactions. The shift can be substantial, moving reactivity from the UV into the biologically benign and more deeply penetrating visible light region [11].

Experimental Protocols: Measuring the Mismatch

Understanding and verifying this mismatch requires specific experimental methodologies that move beyond simple absorption spectroscopy.

Photochemical Action Plot Methodology

The primary tool for identifying wavelength-dependent reactivity is the photochemical action plot, which directly maps the efficiency of a photochemical process against the excitation wavelength [11] [2].

Detailed Protocol:

- Preparation: Create a stock solution of the photoreactive compound or reaction mixture. Divide it into multiple aliquots.

- Monochromatic Irradiation: Irradiate each aliquot independently using a wavelength-tunable laser system or a set of narrow-bandwidth LEDs. It is critical that the number of photons delivered at each wavelength is identical and stable to allow for direct comparison [11].

- Conversion Measurement: After irradiation, determine the conversion of the photochemical process for each aliquot using an appropriate analytical method. Common techniques include:

- Data Processing: Plot the measured conversion or yield against the irradiation wavelength to generate the action plot. The resultant curve represents the "true" photochemical reactivity profile, which can then be compared directly to the absorption spectrum [11].

Quantum Yield Determination

The quantum yield (Φ) is a quantitative measure of photochemical efficiency, defined as the number of molecules undergoing a specific reaction per photon absorbed [7] [8]. Discrepancies between absorption and action plots are rooted in the wavelength dependence of this parameter (Φλ) [2].

Protocol for Determining Intramolecular Cyclization Quantum Yield [13]:

- Irradiation and Monitoring: Irradiate a low-concentration solution of the macromolecule (e.g., 25 µM in acetonitrile) with monochromatic, tunable pulsed light. Simultaneously record the UV-Vis absorbance spectrum to monitor the reaction progress.

- Data Fitting: Plot the conversion (ρ) against the number of photons absorbed (Np).

- Calculation: Fit the linear portion of the curve using a modified quantum yield equation to extract the intramolecular quantum yield (Φc).

ρ = Δ Φc Np ; where Δ = [2(1-10^-A)] / [c * V * N_A](A = extinction at irradiation wavelength, c = concentration, V = volume, N_A = Avogadro's number)

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and key factors involved in creating an action plot and determining wavelength-dependent quantum yield.

Mechanistic Insights: Why the Mismatch Occurs

The disparity between absorptivity and reactivity arises because an absorption spectrum only reports on electronic excitations, remaining silent on the complex energy redistribution pathways that follow photon absorption and critically influence the reaction outcome [11]. Several key factors contribute to the observed red-shift:

- Reactivity from Higher Vibrational States: Photons with lower energy (longer wavelength) can populate higher vibrational levels of the excited state. These states may have geometries or electronic distributions more conducive to the reaction coordinate, leading to higher quantum yields despite lower absorption probability [11] [2].

- Competing Deactivation Pathways: At the absorption maximum, non-radiative decay pathways (e.g., internal conversion, heat dissipation) may be particularly efficient, effectively "wasting" absorbed energy. At red-shifted wavelengths, these competing pathways may be less dominant, allowing a greater fraction of absorbed photons to lead to the desired reaction [7] [8].

- Molecular Architecture and Entropic Factors: In macromolecular systems, the spacing and flexibility between chromophores create a "Goldilocks zone" for reactivity. If reactive groups are too close, steric hindrance limits reactivity; if too far, the probability of interaction drops. This can result in a specific wavelength window that optimally promotes the necessary molecular encounters for reaction, which may not align with the absorption peak [13].

- Alternative Reaction Mechanisms: In some cases, red-shifted light may promote a different, more efficient mechanistic pathway to the product, such as one involving energy transfer or triplet states, which would not be reflected in the ground-state absorption spectrum [12].

The interplay of these factors is summarized in the following diagram, which outlines the theoretical framework for understanding photochemical efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Equipment for Red-Shift Reactivity Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Investigation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength-Tunable Laser | Provides monochromatic light with adjustable wavelength and stable photon flux for action plot generation. | Nanosecond pulsed systems are commonly used [11]. |

| Narrow-Bandwidth LEDs | A more accessible alternative to lasers for irradiation at specific, fixed wavelengths. | Must characterize photon output precisely [11]. |

| Integrating Sphere | Enables absolute quantum yield measurement by capturing all emitted or scattered light from a sample. | Accessory for fluorescence spectrometers [7]. |

| Photoinitiators | Compounds that generate reactive species (e.g., radicals) upon light absorption, initiating reactions like polymerization. | Oxime esters, styrylpyrene derivatives [11]. |

| Chromophores for Cycloaddition | Molecules that undergo [2+2] or other cycloadditions upon light exposure, useful for labeling and crosslinking. | Styrylquinoxaline, Anthracene, Pyrene-Chalcone (PyChal) [11] [13]. |

| 3-Cyanoumbelliferone | An additive that can enhance yield and diastereoselectivity in certain photochemical reactions via mechanisms not fully understood. | Used in ring contraction of heterocycles [12]. |

| Acetonitrile (MeCN) | A common, non-interfering solvent for photochemical studies due to its lack of significant solute-solvent interactions (e.g., H-bonding). | Used for consistency in quantum yield studies [13]. |

The documented mismatch between absorption maxima and photochemical reactivity is a critical consideration for researchers and drug development professionals. The evidence shows that assuming reactivity follows absorptivity can lead to the use of suboptimal wavelengths, reducing efficiency and potentially compromising applications in fields like photoimmunotherapy where tissue penetration is key [14].

The adoption of action plot methodology and a nuanced understanding of quantum yield are no longer niche pursuits but essential components of modern photochemical research. By systematically investigating wavelength-dependent reactivity, scientists can unlock more efficient reactions, develop orthogonal chemical systems for complex applications like 3D printing, and design better phototherapeutic agents. The future of photochemistry lies in moving beyond the absorption spectrum to embrace a more complete, photon-precise understanding of chemical reactivity.

The Role of Molecular Microenvironments and the Red-Edge Effect

For centuries, photochemistry has operated on a fundamental principle first articulated by Theodor von Grotthuss in 1819: light is most effective at driving chemical change when its color matches the natural color of the substance it illuminates [2]. This principle, which evolved into the first law of photochemistry—"Only light which is absorbed by a system can cause chemical change"—has long guided researchers to irradiate samples at wavelengths corresponding to maximum absorption (λmax) to induce maximum photochemical change [2]. However, contemporary research is fundamentally challenging this paradigm by revealing that a molecule's absorption spectrum does not reliably predict its photochemical reactivity across different wavelengths [15] [16].

The discovery of a frequent mismatch between absorptivity and reactivity has catalyzed the emergence of precision photochemistry, a field dedicated to understanding and exploiting the nuanced relationship between light and matter [2]. This paradigm shift recognizes that photochemical outcomes are governed by four interconnected pillars: molar extinction (ελ), wavelength-dependent quantum yield (Φλ), chromophore concentration (c), and irradiation duration (t) [2]. Central to this new understanding is the role of molecular microenvironments—the immediate chemical surroundings of a chromophore—which can dramatically alter photochemical behavior through mechanisms collectively known as the red-edge effect [15] [17] [16]. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive comparison of how microenvironments influence photochemical systems, with particular emphasis on the critical evaluation of quantum yield versus molar extinction.

Fundamental Principles: Microenvironments and the Red-Edge Effect

Defining the Red-Edge Effect in Photochemistry

The red-edge effect (REE) describes a phenomenon wherein photochemical reactivity remains significant, or is even enhanced, at wavelengths red-shifted from a chromophore's maximum absorption peak [2] [15]. This effect represents a fundamental departure from traditional photochemical expectations, as molecules can exhibit substantial reactivity even at wavelengths where their absorption is relatively weak [16].

The physical origin of REE lies in the interaction between a chromophore and its immediate surroundings. In polar environments, molecules exist in a distribution of microenvironments with slightly different solvation shells and interaction patterns [15] [16]. Each microenvironment creates distinct energy landscapes for the chromophore, resulting in sub-populations with varied excitation requirements. When irradiated at the red edge of an absorption band, specific sub-populations with favorable energetics for long-wavelength excitation are selectively activated [16]. These selectively excited species often exhibit longer excited-state lifetimes, enhancing their probability of undergoing productive photochemical reactions rather than relaxing through non-radiative pathways [15].

Molecular Systems Exhibiting Microenvironment-Dependent Behavior

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Systems Exhibiting Microenvironment Sensitivity

| Molecular System | Core Structure | Microenvironment Modulator | Observed Red-Edge Effect | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrene-chalcone conjugates | Pyrene-chalcone hybrid | Solvent polarity, covalent tethering | Red-shifted photocycloaddition reactivity [16] | Additive manufacturing, polymer chemistry |

| Chalcone derivatives | Donor-acceptor chalcones | Solvent polarity, substituent groups | Excitation-dependent fluorescence (>140 nm shift) [17] | Biosensing, bioimaging |

| Oxime ester photoinitiators | Oxime ester | Matrix properties | Enhanced reactivity at red-shifted wavelengths [2] | Photopolymerization |

| Graphene quantum dots (GQDs) | Graphene fragments | Edge functionalization (-CH₃, -Br) | Tunable emission & ROS generation [18] | Photodynamic therapy, bioimaging |

The impact of microenvironments extends across diverse chemical systems, though the specific mechanisms vary. For chalcone derivatives with donor-acceptor structures, the red-edge effect enables remarkable excitation-dependent fluorescence, with emission maxima shifting over 140 nm depending on excitation wavelength [17]. This behavior stems from internal charge transfer (ICT) processes that are highly sensitive to the surrounding medium's polarity [17].

In graphene quantum dots (GQDs), edge functionalization creates distinct microenvironments that dramatically influence both optical properties and photodynamic efficacy [18]. Electron-donating groups (–CH₃) induce blue-shifted emission and enhance reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, while electron-withdrawing groups (–Br) cause red-shifted emission and suppress photodynamic activity [18]. The alternately substituted GQDs (6Br-6Me-GQD) demonstrate enriched electron transfer pathways with dual emission peaks and optimal photodynamic performance [18].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Core Experimental Protocols for Microenvironment Studies

Photochemical Action Plot Methodology

Photochemical action plots serve as the fundamental methodology for quantifying mismatches between absorption and reactivity [2] [15]. This technique involves systematically measuring reaction quantum yields across a spectrum of excitation wavelengths to generate a reactivity profile that can be directly compared to the absorption spectrum.

Protocol Details:

- Light Source: Monochromatic light sources (LEDs, lasers) with precise wavelength control [2]

- Quantum Yield Determination: Absolute Φλ measurement using chemical actinometers for each wavelength

- Data Collection: Reaction conversion monitoring via NMR, HPLC, or spectroscopic techniques

- Data Interpretation: Comparison of reactivity maxima versus absorption maxima

Current limitations include the significant experimental effort required, with most studies employing sampling intervals of 15 nm, which may overlook narrow reactivity maxima [2]. Future advancements aim to automate this process with 1 nm intervals for maximum precision [2].

Spectroscopic Techniques for Microenvironment Characterization

Fluorescence Spectroscopy provides critical insights into microenvironment effects through both steady-state and time-resolved measurements [16]. Red-edge effects manifest as excitation wavelength-dependent shifts in emission spectra, particularly for polar molecules in viscous or restricted environments [17].

Time-Resolved Fluorescence Measurements quantify excited-state lifetimes across different excitation wavelengths, revealing how microenvironments influence photophysical pathways [16]. Longer lifetimes at red-shifted wavelengths often correlate with enhanced photoreactivity [15].

Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) enables direct measurement of electronic structure changes in materials like GQDs, linking microenvironment modifications to fundamental photophysical properties [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials for Microenvironment Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic Light Sources (LEDs, lasers) | Providing precise wavelength control | Enables action plot generation and selective excitation [2] |

| Chemical Actinometers | Quantifying photon flux for quantum yield determination | Essential for absolute Φλ measurements [2] |

| Solvent Polarity Series | Modulating bulk microenvironments | Probing solvatochromic behavior and REE [17] |

| Chalcone Derivatives | Model donor-acceptor fluorophores | Studying ICT and REE in small molecules [17] |

| Functionalized GQDs | Single-molecule graphene models | Investigating edge effects on photodynamics [18] |

| Pyrene-Chalcone Conjugates | Tethered chromophore systems | Probing predefined microenvironments [16] |

Comparative Data Analysis: Quantum Yield vs. Molar Extinction

Quantitative Comparison of Photochemical Systems

Table 3: Quantum Yield and Extinction Coefficient Comparison Across Microenvironments

| System | λₐᵦₛₘₐₓ (nm) | λᵣₑₐₜₘₐₓ (nm) | Φλ at λₐᵦₛₘₐₓ | Φλ at λᵣₑₐₜₘₐₓ | REE Magnitude | Key Microenvironment Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxime Ester Photoinitiator [2] | Not specified | Red-shifted | Lower | Higher | Significant | Matrix properties |

| Chalcone ONBr [17] | ~380 | Varies with excitation | Not specified | Not specified | >140 nm Stokes shift | Solvent polarity |

| 12Me-GQD [18] | Not specified | Not specified | High fluorescence Φ | Effective ROS generation | Blue-shifted emission | Electron-donating groups |

| 12Br-GQD [18] | Not specified | Not specified | Lower fluorescence Φ | Suppressed ROS generation | Red-shifted emission | Electron-withdrawing groups |

| 6Br-6Me-GQD [18] | Not specified | Not specified | Dual emission | Optimal ROS generation | Dual peaks | Alternating substitution |

The comparative data reveal several key patterns. First, the magnitude of microenvironment effects can be substantial, with reactivity optima shifting significantly from absorption maxima [2]. Second, strategic manipulation of microenvironments through chemical modification (e.g., GQD edge functionalization) enables predictable tuning of both optical properties and photochemical efficacy [18]. Third, the most sophisticated systems exploit multiple microenvironments to create enriched functionality, as demonstrated by the alternately substituted 6Br-6Me-GQD with its dual emission peaks and enhanced photodynamic performance [18].

Visualization of Microenvironment Impact on Photochemical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates how molecular microenvironments influence photochemical pathways and enable the red-edge effect:

This diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism behind microenvironment effects: selective excitation of specific molecular sub-populations at different wavelengths leads to divergent photochemical pathways, creating the observed mismatch between absorptivity and reactivity [15] [16].

Implications for Research and Development

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Photomedicine

The implications of microenvironment effects extend significantly into pharmaceutical research, particularly in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and controlled drug delivery. The ability to tune reactivity through microenvironment manipulation enables smarter photosensitizer design [18]. For instance, GQDs with specific edge functionalizations maintain effective ROS generation even under hypoxic conditions, addressing a critical limitation in conventional PDT for tumor treatment [18].

In drug delivery, wavelength-orthogonal uncaging systems leverage microenvironment principles to achieve precise spatiotemporal control over drug release [2]. The mathematical framework describing these systems highlights the dynamic interplay between the four pillars of precision photochemistry, particularly how changing chromophore concentrations during reactions influences selectivity [2].

Practical Guidelines for Experimental Design

Researchers should consider several critical factors when designing photochemical experiments:

Beyond Absorption Maxima: Reaction optimization should explore wavelengths beyond λmax, as reactivity maxima frequently occur at red-shifted positions [2] [16].

Microenvironment Control: Solvent selection, matrix engineering, and strategic functionalization provide powerful tools for directing photochemical outcomes [15] [18].

Dynamic Considerations: Recognize that photochemical systems evolve during irradiation, with changing chromophore concentrations altering optical density and selectivity patterns over time [2].

Automation Needs: Current limitations in action plot resolution (typically 15 nm intervals) highlight the need for automated systems to map photochemical reactivity with 1 nm precision [2].

The emerging paradigm of precision photochemistry encourages researchers to view photons not merely as an energy source, but as precise tools for directing chemical transformations. By leveraging the principles of molecular microenvironments and the red-edge effect, scientists can achieve unprecedented control over photochemical processes, enabling advances from fundamental research to therapeutic applications.

In the field of photochemistry, accurately evaluating the efficiency of light-driven processes is fundamental to advancements in drug development, materials science, and environmental chemistry. For decades, the molar extinction coefficient (ε) has been a primary parameter for predicting photochemical activity, based on the assumption that stronger light absorption leads to greater reactivity. However, contemporary research is challenging this paradigm, demonstrating that absorption spectra alone are insufficient for predicting performance. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key photochemical metrics—molar extinction versus quantum yield—and introduces the action plot as an essential tool for a true understanding of photochemical reactivity.

Molar Extinction Coefficient vs. Quantum Yield: A Fundamental Comparison

The following table defines and contrasts these two cornerstone concepts.

| Metric | Definition | What It Measures | Interpretation & Range | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molar Extinction Coefficient (ε) | A measure of how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [11]. | The probability of light absorption by a chromophore. | ε is a molecular property that is constant under set conditions (solvent, temperature, pH). It informs on electronic transitions but remains silent on subsequent events [11]. | Predicting which wavelength of light will be most absorbed by a compound. |

| Quantum Yield (Φ) | The number of molecules of reactant consumed per photon of light absorbed [19] [20]. Also defined as the probability that absorption of one photon leads to one molecule of a given product [19]. | The efficiency of the photochemical process after light absorption. | Φ can range from <1 to >10⁶. A value >1 indicates a chain reaction is occurring, where one photon triggers multiple molecular transformations [19]. | Quantifying the actual efficiency of a photochemical reaction, independent of absorption strength. |

The first law of photochemistry, the Grotthus-Draper law, establishes that only light absorbed by a molecule can produce photochemical change [19]. While molar extinction indicates the potential for a photochemical event by showing which photons are absorbed, quantum yield reveals the actual outcome—how effectively that absorbed energy is channeled into a desired reaction.

The Action Plot: Integrating Absorption and Efficiency

The critical advancement in precision photochemistry is the action plot, which directly maps the photochemical reactivity of a molecule as a function of the excitation wavelength [11]. Unlike an absorption spectrum, which only shows where a molecule absorbs light, an action plot shows which wavelengths of light most efficiently drive a specific chemical transformation.

Experimental Protocol for Generating an Action Plot

The following workflow details the methodology for creating an action plot, a technique refined in recent research [11] [3].

Key Experimental Details:

- Light Source: A wavelength-tunable laser or a set of narrow-bandwidth UV-LEDs (e.g., 295–400 nm) is used to ensure monochromatic irradiation and an identical, stable number of photons at each wavelength [9] [11].

- Actinometry: The photon flux of the light source must be precisely quantified using a chemical actinometer with a known quantum yield, such as 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (Φ = 0.43, constant from 300–400 nm) [9].

- Conversion Analysis: The yield or conversion of the photochemical process is determined using an appropriate analytical method. Common techniques include High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to monitor reactant loss [9], nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), or gravimetric analysis for polymerizations [11].

Comparative Analysis: Why the Action Plot is Indispensable

The power of the action plot lies in its ability to reveal a fundamental and often overlooked mismatch: a molecule's peak absorptivity does not always align with its peak reactivity [11]. Relying solely on the absorption spectrum can lead researchers to use suboptimal wavelengths, reducing efficiency and potentially causing unwanted side reactions.

Case Study: Styrylquinoxaline Cycloaddition

- Absorption Spectrum: Shows a maximum at 380 nm with negligible absorption above 480 nm [11].

- Action Plot: Reveals that the cycloaddition reaction remains efficient at wavelengths up to 500 nm [11].

- Practical Implication: Without the action plot, a researcher would assume that green light (e.g., 450 nm) is ineffective. The action plot shows that it is highly effective, enabling DNA labeling applications under biologically benign conditions [11].

This paradigm shift, powered by action plots, is formalized in the emerging field of Precision Photochemistry, which stands on four pillars: molar extinction, wavelength-dependent quantum yield, chromophore concentration, and irradiation length [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and their functions for conducting rigorous photochemical experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Monochromatic LED System | Provides precise, narrow-bandwidth light for wavelength-resolved quantum yield measurements [9]. |

| Chemical Actinometer (e.g., 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde) | A reference compound with a known, constant quantum yield used to calibrate and determine the photon flux of a light source [9]. |

| HPLC with UV-Vis Detector | Accurately monitors the concentration of reactants and products over time during photolysis experiments [9]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures the absorption spectrum of a compound to determine its molar extinction coefficient and track spectral changes [9]. |

Implications for Drug Development and Research

Understanding and applying these metrics has direct, practical consequences for scientific and industrial applications.

- Optimized Phototherapeutics: Designing light-activated drugs (phototherapeutics) requires knowledge of the most effective wavelength to trigger the drug's action, which may be different from its absorption maximum. This enables deeper tissue penetration and reduced side effects.

- Efficient Synthesis: Photochemical reactions are increasingly used in API synthesis. Using the wavelength indicated by an action plot, rather than the absorption maximum, can lead to faster reaction times, higher yields, and fewer byproducts.

- Accelerated Discovery: Moving beyond the absorption spectrum as the sole guide allows researchers to discover new, unexpected reaction windows for existing chromophores, accelerating the development of new materials and chemical probes.

From Theory to Bench: Measuring Quantum Yields and Applying Action Plots

In photochemical research, particularly in the development of novel therapeutics and photosensitizers for applications like photodynamic therapy (PDT), accurately quantifying the efficiency of light-driven processes is paramount [21] [22]. The quantum yield serves as the fundamental metric for this efficiency, defined as the number of a specific molecular event occurring per photon absorbed by the system [23]. However, a single, universal quantum yield value is often insufficient for a complete mechanistic understanding. The distinction between true and apparent quantum yields represents a critical conceptual and practical division, impacting the accuracy of kinetic modeling, the predictability of photoreactions, and the rational design of photoactive drugs [24]. Misapplication of these definitions can lead to significant errors in interpreting experimental data and scaling up photochemical processes. This guide provides a clear, standards-based comparison of these two key parameters, framed within the context of evaluating their relationship with the molar extinction coefficient for researchers and drug development professionals.

Defining Quantum Yields: IUPAC Standards and Key Concepts

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) provides the foundational definitions for quantum yield. The core concept is expressed as the number of defined events divided by the number of photons absorbed by the system [23]. IUPAC further distinguishes between two primary forms:

- Integral Quantum Yield (Φ(λ)): This is defined as the total number of events (e.g., molecules reacted or photons emitted) divided by the total number of photons absorbed over a defined period. It provides an average efficiency for a reaction [23].

- Differential Quantum Yield (φ): This is an instantaneous measurement, defined as the rate of change of a measurable quantity (dx/dt) divided by the amount of photons absorbed per unit time (e.g., the photon flux). This is essential for kinetic studies where reaction conditions change over time [23].

Table 1: Core Definitions and Mathematical Formulations of Quantum Yield.

| Term | IUPAC Definition | Mathematical Formulation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Quantum Yield (Φ) | Number of defined events per photon absorbed [23]. | (\mathit{\Phi}=\frac{\text{number of events}}{\text{number of photons absorbed}}) | Applicable to both photophysical processes (fluorescence, phosphorescence) and photochemical reactions [23]. |

| Differential Quantum Yield | The instantaneous yield based on reaction rates [23]. | (\mathit{\Phi}(\lambda) = \frac{{\rm{d}}x/{\rm{d}}t}{q_{n,{\rm{p}}}^{0}[ 1 - 10^{-A(\lambda)} ]}) | Used in photokinetics; requires measurement of the reaction rate and the absorbed photon flux at a specific time [23] [24]. |

| Integral Quantum Yield | The total yield over a period of illumination [23]. | (\mathit{\Phi}(\lambda) = \frac{\rm{amount\ of\ reactant\ consumed\ or\ product\ formed}}{\rm{number\ of\ photons\ absorbed}}) | Simpler to determine; provides an average efficiency for a reaction with a significant conversion [23]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual relationship between the different types of quantum yields and their measurement principles.

Diagram 1: A conceptual map of quantum yield classifications, showing how the core definition branches based on the process type, temporal measurement, and absorption consideration.

True vs. Apparent Quantum Yield: A Detailed Comparison

The distinction between "true" and "apparent" quantum yields addresses a critical variable: which species in the system is responsible for absorbing the incident light that drives the process of interest.

True Quantum Yield (φ): This is the correct and mechanistically meaningful quantum yield. It considers only the photons absorbed by the specific reactant that initiates the photoprimary step. Its value is an intrinsic property of that photochemical step and should remain constant throughout a reaction, provided the reaction mechanism does not change [24]. It is defined as the rate of change of a measurable quantity divided by the amount of light absorbed only by the reactant of interest ((I{abs}^A)) [24]. For complex reactions, a Partial Quantum Yield ((φk^A)) can be defined for each linear independent step (k), representing the true differential quantum yield for that specific step [24].

Apparent Quantum Yield ((γ^A) or (φ{dif}^A)): This is an experimentally accessible but potentially misleading measure. It is calculated based on the total number of photons absorbed by the entire system ((IT)). This is simpler to measure but becomes inaccurate if other light-absorbing species are present that do not contribute to the reaction of interest. Its value can vary significantly over the course of a reaction as the absorption profile of the solution changes [24].

Table 2: Comparative analysis of True vs. Apparent Quantum Yields.

| Characteristic | True Quantum Yield | Apparent Quantum Yield |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Efficiency based on photons absorbed only by the reactant initiating the photoreaction [24]. | Efficiency based on total photons absorbed by the reaction system [24]. |

| Theoretical Basis | Mechanistically correct; intrinsic to the photoprimary step. | Empirical; dependent on the system's overall absorption. |

| Time Dependence | Constant (for a given step and conditions) [24]. | Varies with conversion as absorption changes [24]. |

| Complexity of Determination | Requires detailed knowledge of individual absorptivities; can involve significant experimental and numeric effort [24]. | Simpler to determine experimentally. |

| Utility in Modeling | Essential for predictive kinetic models of complex reactions [24]. | Of limited value for predictive modeling outside simple systems. |

| Reported As | True differential, partial quantum yield [24]. | Apparent integral, apparent differential quantum yield [24]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Accurate determination of quantum yield, particularly the true quantum yield, requires careful experimental design. The following protocols are foundational to the field.

Relative Method for Fluorescence Quantum Yield

This common method compares the sample to a standard with a known quantum yield [25]. The following workflow outlines the key steps.

Diagram 2: Workflow for determining fluorescence quantum yield using the relative method.

Detailed Protocol:

- Standard Selection: Choose a standard reference dye with a known fluorescence quantum yield ((Φ_S)) that is stable and has excitation/emission profiles similar to your sample. Common standards include quinine sulfate (Φ = 0.55 in 0.5 M H₂SO₄) or rhodamine dyes [24] [25].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare optically dilute solutions of both the standard and the sample in the same solvent. The absorbance at the excitation wavelength should be low (typically < 0.05) to minimize inner filter effects like re-absorption and scattering [24] [25].

- Spectroscopic Measurement:

- Record the absorbance spectra ((ODS) and (ODA) at the excitation wavelength, e.g., 360 nm).

- Record the fluorescence emission spectra for both standard and sample using the same instrument settings (excitation wavelength, slit widths, etc.). Ensure the excitation light is collimated for accurate results [26].

- Data Analysis: Determine the integrated fluorescence intensity (F) for each emission spectrum. The quantum yield of the unknown sample ((ΦA)) is calculated using the formula [24]: (ΦA = ΦS \times \frac{FA}{FS} \times \frac{ODS}{OD_A}) where subscripts A and S denote the sample and standard, respectively.

Determining Photoisomerization Quantum Yield

For photoswitchable molecules (e.g., azobenzenes, diarylethenes), the quantum yield of photoisomerization is the key parameter. The method differs as it tracks the change in concentration of isomers over time [26].

Detailed Protocol:

- Irradiation Setup: Use a monochromatic light source (e.g., LED or laser) at a wavelength where the initial isomer (A) absorbs significantly. The light must be collimated, and the solution must be stirred vigorously to ensure a homogeneous concentration [26].

- Concentration Monitoring: Use UV/Vis spectroscopy to monitor the change in concentration of isomers A and B over time. The total absorbance ((A{total})) is the sum of contributions from both species: (A{total} = εA cA l + εB cB l) [26].

- Photon Flux Calibration: Accurately determine the photon flux ((I_0)) of the incident light using a chemical actinometer or a calibrated photodiode.

- Data Fitting with a Kinetic Model: The general rate equation accounting for photo-induced forward ((A \rightarrow B)) and reverse ((B \rightarrow A)) reactions, as well as thermal relaxation ((B \rightarrow A)), is [26]: (\frac{dcA}{dt} = -\phi{A \rightarrow B} \frac{I0}{NA V} \betaA + \phi{B \rightarrow A} \frac{I0}{NA V} \betaB + kt cB) where (φ) are quantum yields, (β) is the fraction of light absorbed by each species, (kt) is the thermal rate constant, and (N_A V) is in dm³.

- Analysis: For simple systems where only A absorbs and thermal back-reaction is slow, the analysis can be simplified. However, for complex systems, the quantum yields ((φ{A \rightarrow B}) and (φ{B \rightarrow A})) are best determined by numerically fitting the concentration-time data to the kinetic model using specialized software, as described in scientific literature [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, instruments, and software for quantum yield determination.

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Yield Standards (e.g., Quinine Sulfate, Rhodamine 6G) | Reference for relative fluorescence quantum yield determination [24] [25]. | Must have known Φ in specified solvent; should exhibit spectral overlap with sample. |

| Chemical Actinometers (e.g., Potassium Ferrioxalate) | Absolute calibration of photon flux from a light source [26]. | Acts as a light meter; requires well-established protocol and careful handling. |

| Monochromator / Bandpass Filters | Provides monochromatic excitation light as required by IUPAC definition [23]. | Bandwidth should be narrower than the sample's absorption band [4]. |

| Integrating Sphere | An accessory for absolute quantum yield measurement, capturing all emitted or scattered light [25]. | Essential for measuring scattering samples or absolute Φ without a standard. |

| UV/Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures absorbance (OD) and monitors concentration changes in photochemical reactions [26]. | Critical for ensuring low, matched absorbance in relative method and for kinetics. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | Measures emission spectra and integrated fluorescence intensity. | Requires correct calibration of detection wavelength and intensity. |

| Stirred Cuvette Holder | Maintains homogeneity during irradiation for accurate kinetic data [26]. | Prevents concentration gradients, which is crucial for differential quantum yield. |

| Kinetic Fitting Software (e.g., custom MATLAB, Python scripts) | Numerical fitting of kinetic data to complex models to extract true quantum yields [26]. | Necessary for analyzing photoisomerization kinetics and complex reaction schemes. |

The rigorous distinction between true and apparent quantum yields is not merely academic; it is a practical necessity for researchers aiming to design effective photoactive molecules, from fluorescent probes with high brightness to potent photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy [27]. While the apparent quantum yield offers a simple, initial assessment, the true (or partial) quantum yield provides the intrinsic, time-independent metric required for predictive modeling and mechanistic understanding [24]. As the field of photopharmacology and photoresponsive drug delivery advances [22], the accurate reporting of these parameters, alongside critical experimental details like molar absorptivity, becomes fundamental to scientific progress and reproducibility. By adhering to IUPAC definitions and employing the appropriate experimental and analytical methodologies outlined in this guide, scientists can ensure their evaluations of photochemical system performance are both accurate and meaningful.

The field of optical spectroscopy is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from traditional broad light sources to advanced Light Emitting Diode (LED)-based approaches [28]. This evolution is particularly relevant in the context of precision photochemistry, where understanding the intricate relationship between quantum yield (Φλ) and molar extinction (ελ) is paramount for directing photochemical processes with both wavelength and spatiotemporal precision [2]. LEDs, once considered simple indicator lights, are now recognized as robust spectroscopic tools that offer notable advantages including compact size, cost-effectiveness, long operational lifetimes, and minimal heat generation [29] [30]. Their inherent narrow spectral bandwidths and ability to be precisely sequenced make them ideally suited for application-specific spectroscopic systems that can target particular analytical challenges [31] [30].

This guide provides an objective comparison of LED-based spectroscopic techniques against conventional approaches, with experimental data and methodologies presented to help researchers select appropriate configurations for their investigations into quantum yield and molar extinction relationships.

Theoretical Framework: Quantum Yield vs. Molar Extinction in Precision Photochemistry

Precision photochemistry stands on four fundamental pillars: molar extinction (ελ), wavelength-dependent quantum yield (Φλ), concentration of chromophores (c), and irradiation length (t) [2]. The first law of photochemistry (Grotthus-Draper law) establishes that only light absorbed by a molecule can produce photochemical change, making molar extinction a fundamental consideration [19]. However, a critical understanding in modern photochemistry is that not all absorption events lead to reaction with equal probability [2].

Quantum yield is defined as the number of molecules of reactant consumed per photon of light absorbed, or alternatively as the number of photons emitted per photon absorbed in spectroscopic contexts [19]. The wavelength-dependent quantum yield (Φλ) often does not align directly with the molar extinction spectrum, meaning maximum absorption does not necessarily correlate with maximum photoreactivity [2]. This mismatch between absorption and reactivity spectra necessitates careful wavelength selection in photochemical experiments, particularly for systems where orthogonal reactivity or selective photochemical transformations are desired [2].

The relationship between these parameters dictates that the overall photochemical action depends on the product of both the probability of photon absorption (governed by ελ) and the probability that an absorption event leads to a specific photochemical outcome (governed by Φλ) [2]. This complex interplay forms the theoretical foundation for understanding the performance characteristics of different LED-based spectroscopic techniques discussed in subsequent sections.

Comparative Analysis of LED-Based Spectroscopic Techniques

Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of LED-Based Spectroscopic Techniques with Conventional Alternatives

| Technique | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LED Thermal Lens Spectrometry (TLS) | LOD for Safranin O: ~µM range with 15 mW power [32] | ≈2x sensitivity enhancement with double-pass probe design; Simultaneous fluorescence monitoring [32] | Lower sensitivity vs. laser-TLS for low-absorbing samples; Requires configuration optimization [32] | Trace determination in environmental systems; Studying molecular interactions (e.g., dye-micelle) [32] |

| LED vs. Photodiode Light-Scattering Detection | Transferrin LOD: 0.2 mg/L (LED-LED) vs. 0.1 mg/L (LED-PD); Ferritin: Only LED-PD effective (107-253 μg/L) [33] | LED-LED: Simplified optics; LED-PD: Better sensitivity for proteins like ferritin [33] | Performance depends on specific analyte; LED-PD may require polymer enhancement [33] | Immunoprecipitation assays; Multicommutated flow analysis for clinical proteins [33] |

| LED Narrowband Diffuse Reflectance (nb-DRS) | Hydration measurement error: 8.7% (uncorrected) vs. 2.2% (with spectral correction) [31] | Enables miniaturization for wearable monitors; Spectral correction compensates for LED bandwidth [31] | Requires characterization of LED spectra; Sensitive to source-detector separation [31] | Tissue hydration monitoring; In vivo spectroscopic measurements in clinical settings [31] |

| Traditional Lamp-Based Spectroscopy | Broad spectral coverage; High resolution with spectrometer detection [29] [31] | Established protocols; Excellent for fundamental spectral discovery [29] [30] | Large, power-hungry setups; Frequent replacement; Significant heat generation [29] [30] | Broad-spectrum analysis; Research requiring full spectral characterization [29] |

| Laser-Based Spectroscopy | High sensitivity and spatial resolution [32] [28] | Superior focusing capabilities; High power for demanding applications [32] | Higher cost, larger size; Can cause sample photodamage [32] [29] | High-sensitivity trace analysis; Techniques requiring coherent sources [32] |

Technical Considerations for System Implementation

Table 2: Technical Design Considerations for LED-Based Spectroscopic Systems

| Design Parameter | Impact on System Performance | Recommendations for Precision Photochemistry |

|---|---|---|